Abstract

Aerobic and anaerobic organisms and their functions are spatially or temporally decoupled at scales ranging from individual cells to ecosystems and from minutes to hours. This is due to competition for energy substrates and/or biochemical incompatibility with oxygen (O2). Here we report a chemolithotrophic Aquificales bacterium, Hydrogenobacter, isolated from a circumneutral hot spring in Yellowstone National Park (YNP) capable of simultaneous aerobic and anaerobic respiration when provided with hydrogen (H2), elemental sulfur (S0), and O2. Cultivation experiments demonstrated that simultaneous aerobic and anaerobic respiration enhanced growth rates and final cell concentrations when compared to those grown aerobically or anaerobically. Consumption of O2 measured via gas chromatography and detection of transcripts for proteins involved in S0 and O2 reduction in H2/S0/O2-grown cultures confirmed co-occurring aerobic and anaerobic metabolism. This aerobic, S0-reducing metabolism is suggested to provide a competitive advantage in environments where O2 availability is low and variable. Genomic data indicating the prevalence of proteins allowing for this hybrid form of energy metabolism among bacteria and archaea suggest it to be widespread but previously overlooked due to rapid, O2-dependent abiotic oxidation of produced sulfide. These observations challenge existing paradigms of strict delineations between aerobic and anaerobic metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The order Aquificales is an early diverging bacterial lineage that is most commonly found in high temperature hydrothermal systems where it is often predominant in microbial communities1,2,3,4,5. This includes dark, deep-sea hydrothermal vents and continental hot springs that have conditions that often preclude photosynthetic metabolisms6,7. As such, Aquificales tend to be microaerophiles that can oxidize hydrogen (H2), arsenite, sulfide (H2S/HS-), or H2S/HS- oxidation products such as thiosulfate (S2O32-) and elemental sulfur (S0) to drive chemolithoautotrophic metabolism8. Exceptions include facultatively anaerobic members that can also reduce nitrate, arsenate, and ferric iron or those that can also grow chemoorganotrophically9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

The predominance of microaerophilic and obligately or facultatively chemolithoautotrophic Aquificales in many hot spring environments is consistent with the availability of oxidants (e.g., O2), reductants (e.g., H2, HS-, S0), and CO2 in these habitats and the generally limited availability of organic carbon17,18. This includes acidic hot springs that are typically sourced by oxidized meteoric water (recent rain or snowmelt) that can be infused by volcanic gas rich in CO2 and reductant such as H2S and H219,20,21. In such environments, the Aquificales genus Hydrogenobaculum, which grows autotrophically via aerobic oxidation of H2, H2S/HS-, or S0, often predominates1,22,23,24,25. Likewise, circumneutral to alkaline hot springs, which tend to be sourced by deep hydrothermal aquifers, often host communities comprised of the Aquificales genera Thermocrinis and Sulfurihydrogenibium that grow autotrophically via aerobic oxidation of H2, HS-, S0, or S2O32-1,10,11,14,26,27,28. These bacteria can form abundant filamentous biofilms in the outflow channels of hot springs2,29,30, positioning themselves near the air water interface to maximize access to atmospheric O2. This is an important emergent function since deep aquifer waters that source circumneutral to alkaline hot springs tend to be anoxic19 due to their long residence times in the subsurface31,32. However, many circumneutral to alkaline hot springs lack outflow channels and availability of O2 is limited to atmospheric gas infusion that is enhanced by turbulence created through volcanic gas ebullition and geysing. Yet, the planktonic (water column) communities in these pools, and to a lesser extent the sediment communities, still tend to be dominated by members of the Aquificales, including those related to the aerobic members of Thermocrinis, Venenivibrio, and Hydrogenobacter33,34,35,36,37,38. This suggests the possibility of alternative adaptations or growth strategies that allow these organisms to successfully compete for energy resources, even when O2 is limited.

Thermocrinis ruber strain OC 1/4 was isolated from Octopus Spring, an alkaline spring in the Lower Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park (YNP), U.S.A.28. T. ruber is a microaerophilic autotroph that can oxidize H2, S2O32-, and S0. Interestingly, in the presence of H2, T. ruber was reported to reduce S0 to HS- when O2 concentrations were low (< 3% vol./vol). However, it was not reported if this was due to O2 being preferentially consumed prior to commencement of S0 reduction. Similarly, Aquifex aeolicus, which was isolated under H2-oxidizing microaerophilic conditions39, has been reported to reduce S0 to HS- with H2 as a reductant during growth in the presence of O240. Cells were also reported to not grow in anaerobic conditions. Biochemical data from a previous study indicates that energetic coupling of the oxidation of H2 with the reduction of S0 in A. aeolicus occurs via a membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase (Hyd)-sulfur reductase (Sre) complex (Hyd-Sre), with electron transfer from H2 via quinone to a molybdopterin cofactor in Sre40. T. ruber also encodes Hyd and Sre (genome assembly ASM51273v1), suggesting that S0 reduction with H2 is likely occurring via this complex, and that this is apparently not inhibited by O2. The growth and HS- production in A. aeolicus and T. ruber via the H2/S0 couple in the presence of O228,40 suggests low levels of O2 could enhance growth and activity in these organisms. Generating a better understanding of this putative hybrid aerobic/anaerobic respiratory strategy would provide insight into how phylogenetically deep-branching facultatively aerobic microorganisms successfully compete in environments where O2 flux is low and variable both today and in similar environments on early Earth as it became oxygenated.

To begin to investigate this phenomenon, an Aquificales strain, herein referred to as Hydrogenobacter RSW1, that inhabits a hot spring sourced by deep, anoxic hydrothermal waters and that is capable of microaerophilic growth and H2-dependent S0 reduction was isolated and characterized with respect to aerobic and anaerobic growth. Analyses of the RSW1 isolate genome were used to predict the metabolic potential of Hydrogenobacter RSW1, which included an ability to oxidize H2 and S0 and an ability to reduce S0 and O2 based on proteins encoded. Here we describe this strain and characterize its growth kinetics when provided with various combinations of these electron donor and acceptor pairs, including when provided with multiple electron donors or acceptors at the same time. Results are discussed as they relate to the ecology of this widespread group of organisms and the putative insights these data provide into how anaerobic cells may have adapted to take advantage of O2 as it became progressively more available.

Results and discussion

Roadside west (RSW) description

In June of 2017, RSW had a temperature of ~68 °C and a pH of ~6.8. The temperature and pH have been relatively stable since 1996, ranging from 62 to 70 °C and in pH from 6.44 to 6.8017,41,42,43,44. The HS- and Fe(II) concentrations were 0.44 mg L−1 (13.3 µM) and below the limit of detection (LOD; 0.011 mg/L), respectively, at the time of sampling. The concentration of SO42− was 72 mg L−1 ( ~ 750 µM) and the concentration of Cl- was 370 mg L−1 ( ~ 10 mM). These values suggest that RSW is sourced by the deep hydrothermal aquifer (estimated to contain 30–70 mg L−1 SO42− and 300 mg L−1 Cl-19,20,43) with minimal input of near surface meteoric water, as shown in previous studies43. Consistent with this interpretation, the δ2H and δ18O values of RSW waters have ranged from −130 to −132‰ and −12.0 to −12.5‰17,41,43,44, similar to other hot springs sourced by the deep hydrothermal aquifer and that have undergone boiling and evaporation19,20,43. As such, the hydrothermal fluids sourcing RSW are likely to be anoxic19 due to their long ( ~ 100’s to 1000’s years) residence time in the subsurface32.

The spring is fairly turbulent due to volcanic gas ebullition (including CO2 and H244) that likely promotes infusion of atmospheric gas (i.e., O2). Previous reports of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the source of RSW range from 119 to 156 nM. H2O2 is produced via photochemical reactions involving dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and O2, implying available O2. Further, the H2O2 and DOC values in RSW are similar to another spring in YNP where dissolved O2 (DO) was measured at concentrations ranging from 152 to 165 µM. Although DO measurements were not taken during the original sampling event in 2017, DO measurements were collected in October of 2024 using a DO instrument and O2 probe. The probe was tested prior to field measurements to ensure accuracy by measuring O2 concentration while increasing the temperature in a water bath (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Once the probe functionality was confirmed, measurements were collected in the water column of RSW (68 °C, pH 6.57 at time of sampling) every 30 sec over a span of 10 min. DO values ranged from 77.5 to 96.9 µM in the water column of the spring (Supplementary Fig. 3B) and were around 12.5 µM at a depth of 0.5 cm into the sediment. This suggests that O2 may become limiting to microorganisms in the water column and sediments of the spring. Based on metagenomic sequencing of the planktonic and sediment communities, a diverse set of organisms capable of aerobic, anaerobic, and S0 metabolisms were identified43. Together, these observations make RSW an appropriate target for understanding the interplay between anaerobic and aerobic thermophile metabolisms.

Hydrogenobacter RSW1 description and phylogenetic position within aquificales

Three rounds of dilution to extinction enrichments using S0-rich sediments from RSW44 as inoculum and medium containing H2 as an electron donor, O2 as an electron acceptor, and CO2 as a carbon source yielded a culture with a single morphotype. A genome was assembled from sequenced culture DNA that comprised 48 contigs and that was estimated to be 98.0% complete; 5% of reads were unbinned. 99.9% of the raw reads were classified as Hydrogenobacter using SingleM45, confirming that the culture is an isolate. The genome (Hydrogenobacter RSW1) was most closely related to the Aquificales bacterium Hydrogenobacter hydrogenophilus24, formerly known as Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum46. The genome of Hydrogenobacter RSW1 exhibited an average nucleotide identity (ANI) of 86.8% and an average amino acid identity (AAI) of 88.7% to the H. hydrogenophilus genome and encoded proteins, respectively, suggesting that it represented an undescribed species within the Hydrogenobacter genus.

A phylogenomic analysis was conducted with members of the Aquificales (NCBI accession numbers can be found in Supplementary Fig. 2), rooted with members of the Thermotogales (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 2), as has been done in previous analyses of the Aquificales47. Hydrogenobacter RSW1 groups with other YNP Hydrogenobacter metagenome assembled genomes (MAGs), all of which are descended from an ancestor of H. hydrogenophilus and H. thermophilus. The close shared ancestry between the Thermocrinis and Hydrogenobacter clades indicates that these organisms are likely metabolically similar and therefore may share similar metabolic, physiological, and ecological traits.

Desulfurobacteriales are grouped at the order level, while Hydrogenobacter is grouped at the species level; all other Aquificales clades are grouped at the genus level, except where MAGs could not be classified to a known genus. The total number of organisms within each clade (n) is indicated, followed by the number of organisms within those clades that encode homologs of SreA. Hydrogenobacter RSW1 is depicted in bold, red text. Members of the order Thermotogales were used as the outgroup. The uncollapsed phylogeny, along with accession numbers, are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2.

The order Desulfurobacteriales branches distinctly and basal from other Aquificales, which are further classified as the families Hydrogenothermaceae and Aquificaceae. Members of the Desulfurobacteriales can reduce S09,48,49,50,51,52 but apparently do so through mechanisms that do not involve Sre since homologs of this enzyme are not encoded in their genomes (Fig. 1). Interestingly, Desulfurobacteriales also contain the only members that have been characterized as obligate anaerobes9,48, while all members within Aquificales, which includes the families Aquificaceae and Hydrogenothermaceae, are considered to be microaerophiles, with some being facultative anaerobes8,10,11,13,14,22,26,27,28,39,40,53,54. As such, the ability to utilize O2 as an oxidant appears to have occurred after the divergence of Aquificales from Desulforobacteriales, with all derived lineages apparently capable of using O2. Homologs of proteins involved in S0 respiration (Sre) were acquired in Aquificales post divergence of Hydrogenothermaceae and Aquificaceae from their ancestor, as indicated by the distribution of homologs in the latter family and their paucity in the former (Fig. 1). Among members of Aquificaceae, the distribution of Sre is widespread with 100% of the Thermocrinis genomes, 50% of the Hydrogenobacter genomes, and all Hydrogenivirga genomes analyzed encoding homologs of Sre, while three clades of Unclassified Aquificaceae do not encode for Sre.

To further interrogate the ecology of Hydrogenobacter RSW1, protein encoding genes in its genome were annotated to predict its metabolic potential. The RSW1 genome encodes a full reductive TCA (rTCA) cycle for CO2 fixation, consistent with isolation of the strain with CO2 as the sole provided carbon source and with many members in the order Aquificales being autotrophic2,55,56. The genome of Hydrogenobacter RSW1 does not encode identifiable organic carbon importers and lacks full glycolytic and TCA cycles, but does encode a full gluconeogenesis pathway (Fig. 2), indicating that this organism is potentially an obligate autotroph, consistent with the strain identified as most closely related46. Efforts to grow this organism using a variety of organic carbon sources (formate, acetate, glucose, fructose, galactose, mannose, lactose, maltose, sucrose, yeast extract, peptone, casamino acids) under microaerophilic conditions in the presence or absence of H2 as an electron donor were unsuccessful. The Hydrogenobacter RSW1 genome encodes a variety of sulfur metabolizing genes, including a homolog of Sqr (sulfide quinone oxidoreductase). The RSW1 genome also encodes the sulfur oxidation (Sox) system, including SoxAX, SoxYZ, and SoxB, indicating the ability to oxidize both S0 and S2O32− to SO42-57. In addition to S0 oxidation pathways, the RSW1 genome encodes SreABC (sulfur reductase), an enzyme complex allowing for the reduction of S0 or polysulfide (Sx2−) to HS-40,58,59, with SreA being the catalytic subunit. The absence of a twin arginine motif in the N-terminus of SreA suggests that it is localized on the cytoplasmic side of the cell membrane, requiring S0 or Sx2− to be transported across the cell membrane (Fig. 2). The RSW1 genome does not encode dissimilatory SO42- reduction genes, indicating that cells cannot generate energy from SO42- reduction.

Amt, ammonia transporter; CI, complex 1; CIII, complex 3; CIV, complex 4 (Cox); CysW, sulfate/thiosulfate ABC transporter; Cyt B, cytochrome B subunit; DIA, diaphorase subunit; Gln, glutamine synthetase; Glt, glutamate synthase; GNG, gluconeogenesis; HydS, hydrogenase small subunit; HydL, hydrogenase large subunit; Nas, assimilatory nitrate reductase; Nir, nitrite reductase; PFOR, pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase; Q, quinone pool; rTCA, reductive TCA cycle; Sqr, sulfide quinone oxidoreductase; Sox, sulfur oxidation (Sox) pathway; Sre, sulfur reductase. Proteins related to sulfur oxidation (purple), sulfur reduction (orange), nitrogen assimilation (dark blue), carbon fixation (red), hydrogen oxidation (light blue), and oxidative phosphorylation (green) are color coded respectively. Transport proteins are yellow. Pathways are depicted to only show metabolisms discussed in the text. Question marks indicate uncertainty in how those depicted tasks are performed.

The Hydrogenobacter RSW1 genome also encodes three homologs of [NiFe]-hydrogenases including representatives of group 1e, 1 d, and 2 d hydrogenase60 (Fig. 2). The group 1e hydrogenase (Hydrogenase 1) is predicted to supply reducing equivalents to the S0/Sx2- reducing Sre complex, which was first isolated and described in the Aquificales bacterium Aquifex aeolicus40, and that is distributed among numerous other bacterial and archaeal organisms58,59,61,62,63. The group 1 d hydrogenase (Hydrogenase 2) is predicted to be involved in H2 oxidation coupled to reduction of O2 and is thus likely involved in aerobic respiration. Lastly, the group 2 d hydrogenase (Hydrogenase 3) is hypothesized to be involved in generating reducing equivalents (i.e., NAD(P)H) for CO2 fixation, although the exact function has not been identified60. Consistent with this prediction, a diaphorase subunit that facilitates electron transfer to/from NAD(P)H is encoded by a gene proximal to the group 2 d hydrogenase enzyme (Fig. 2).

Hydrogenobacter RSW1 growth characterization

Genomic predictions of the metabolism of RSW1 were tested experimentally, in particular the ability to oxidize HS-, S0, and S2O32- under microaerobic (2% vol./vol. O2) conditions. Equations are provided to refer to throughout the results and discussion:

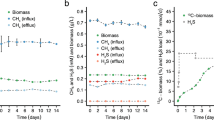

Cells did not grow with HS- when provided with 2% O2 as electron acceptor (Eq. 1), possibly due to the fast kinetics of abiotic and O2-dependent HS- oxidation at circumneutral pH64,65, as further discussed below. When cells were provided with S0 or S2O32− as the electron donor and 2% O2 as the electron acceptor (Eqs. 2 and 3), the concentration of cells increased concomitant with an increase in the concentration of SO42− (Supplementary Fig. 4). When Hydrogenobacter RSW1 was provided with H2 as an electron donor and 2% or 5% O2 as the electron acceptor (Eq. 4), cell concentrations also increased (Fig. 3B). When cultures were provided with H2 as the electron donor and S0 as the electron acceptor (Eq. 5), the concentration of HS- increased but no change in the cell concentration was observed (Fig. 3A, B). HS- concentrations were below the detection limit (< 1 µM; Supplementary Fig. 5) in abiotic controls, indicating that HS- measured in biologic experiments is biogenic. This suggests that the H2/S0 redox couple may support the energy metabolism of the cell but that this is not coupled to biomass production (discussed below). This observation is consistent with prior characterization of the Aquificales bacteria T. ruber and A. aeolicus, which were also shown to be capable of reducing S028,40. In the subsections below, experiments are presented that are aimed at identifying the specific effects of O2 and H2 concentration on pathways of S0 oxidation and reduction in RSW1 and their effects on the growth and metabolism of cells.

Growth experiments were conducted in cultures provided with hydrogen (H2) as reductant, elemental sulfur (S0) as oxidant, and O2 to specified concentrations at the start of the experiment (A, B) or with daily amendments to maintain O2 at the specified concentrations (panels C & D). Cultures containing H2 and O2 without S0 were included for growth comparisons (panels B & D). Total aqueous sulfide (H2S/HS-/S2-) was determined before and after headspace exchange and thus accounts for its loss during headspace exchange (panel C). SO42− was not produced in experiments containing S0 (Supplementary Fig. 6). All cultures were provided with 150 μM SO42− as a sulfur source and were incubated on their sides at 70 °C on a shaking incubator (50 revolutions per minute). The average and standard deviation of three or four replicate cultures is shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Impact of O2 concentration on S0 metabolism without reactor headspace exchange

A previous study of T. ruber and A. aeolicus reported H2-dependent reduction of S0 to HS- (Eq. 5) in the presence of O228,40, an interesting observation since S0 reduction is a form of anaerobic respiration in many cells66. Robust growth was reported for both T. ruber and for A. aeolicus cells grown under this condition, however, it is unclear from these studies if cells were simultaneously reducing O2 and S0 (Eqs. 4 and 5) and, if so, whether there was a growth benefit28,40. Given that Hydrogenobacter RSW1 can oxidize S0 or H2 with O2 (Eqs. 2 and 4) and reduce S0 with H2 (Eq. 5), additional investigations into this phenomenon in RSW1 were undertaken. For the following experiments, the final headspace gas composition for anaerobic growth experiments was (vol./vol.): 80% H2 and 20% CO2. For aerobic growth experiments, the amount of CO2 in the headspace remained constant (20% vol./vol.) but the amount of O2 in the headspace was adjusted as specified, while H2 concentrations were adjusted to balance the O2 concentrations, unless otherwise noted. When provided 0% vol./vol. O2, S0, and H2, a total of ~500 μM of HS- was produced over the course of the incubation but this was not coupled to production of cells (Fig. 3A, B). However, when cells were provided with 2% and 5% vol./vol. O2, S0, and H2, >3.5 mM of HS- was produced over the course of the incubation and metabolic activity was coupled to the production of cells (Fig. 3A, B). In cultures provided with 2% vol./vol. O2/S0/H2, cell concentrations reached a maximum of 4.54 × 107 cells mL− 1 whereas those provided with 5% vol./vol. O2/S0/H2 reached a maximum of 9.68 × 107 cells mL− 1 (Fig. 3B). Production of SO42− was not observed in any of these conditions, indicating that cells were not oxidizing S0 with O2 (Eq. 2) or disproportionating S0 to produce HS− and SO42−, per Eq. 6 (Supplementary Fig. 6). One hundred fifty μM SO42- was provided to all reactors as a sulfur source, such as to not induce cells to metabolize S0 to make it available for assimilation. Cells provided with H2 and 2% and 5% vol./vol. O2 without S0 (Eq. 4) were included for comparison and these reached final concentrations of 6.87 × 107 cells mL− 1 and 1.75 × 108 cells mL− 1, respectively (Fig. 3B). HS- was not detected in these conditions. Based on these data, it was hypothesized that H2-oxidizing cells were simultaneously reducing S0 and O2 (Eqs. 4 and 5) to support their energy metabolism, with those cells provided with higher concentrations of O2 gaining additional energy from a greater availability of this oxidant. The aforementioned experiments were performed without headspace exchange, however, which may have allowed for O2 limitation to develop during the course of incubation, leading to a subsequent metabolic switch to S0 reduction.

Impact of O2 concentration on S0 metabolism with reactor headspace exchange

The low solubility67 and the low diffusivity of O2 at high temperature68 could cause anoxic conditions to develop in cultures that would promote S0 reduction and lead to the erroneous conclusion that the same cells were simultaneously reducing O2 and S0. To begin to rule out this possibility, the same experimental conditions were used as above, however, the headspace of each reactor was flushed for 30 sec followed by replacement of the gas phase to the specified initial concentrations (0%, 2%, or 5% vol./vol. O2) every 24 h during incubation (Fig. 3C, D).

As in the previous experiment, cultures provided with H2 and S0 but not with O2 (0% vol./vol.; Eq. 5) produced HS- without an increase in cell concentration (Fig. 3C, D). Despite exchanging the headspace every 24 h, cultures provided with 2% or 5% vol./vol. O2, H2, and S0 still produced HS-, generating 1.3 mM HS- and 715 μM HS-, respectively (Fig. 3C). These concentrations are lower than those measured in non-exchange experiments (Fig. 3A) for reasons discussed below. Both the 2% vol./vol. O2/S0/H2 condition and 5% vol./vol. O2/S0/H2 condition reached significantly higher cell concentrations, 1.05 × 108 and 5.13 × 108 cells mL− 1, respectively, when compared to the same conditions when the headspace was not exchanged (Fig. 3B, D). This indicates that O2 limitation may have occurred in cultures during the course of the experiments without headspace exchange. Although cells provided with H2 and 2% and 5% vol./vol O2 without S0 (Eq. 4) also reached a higher final cell concentration (1.07 × 108 cells mL− 1 and 3.14 × 108 cells mL− 1, respectively) when compared to the no headspace exchange experiment, the increase was not as significant as the increase observed in cultures provided with S0 (Fig. 3B, D). Cultures provided with H2 and 2% O2 with and without S0 (Eq. 4) grew similarly when the atmosphere was exchanged, while cultures provided with H2 and 5% O2 in the presence of S0 grew significantly better than cultures provided with H2 and 5% O2 without S0 (Fig. 3D). This indicates that there is a significant growth benefit when H2-oxidizing cells are provided with both O2 and S0.

The lack of stimulation of growth in the 2% O2 condition with S0 is likely explained by the abiotic consumption of O2 by HS- (discussed below), which may have decreased O2 availability during the course of the incubation, when compared to the condition without S0 (Eq. 4). Further, the amount of HS- that accumulated in cultures during the course of incubation was not constant, and periods of HS- accumulation were observed followed by periods of HS- drawdown towards the end of incubation (Fig. 3C). For example, a substantial amount of HS- was produced until day three in the 2% O2/S0/H2 growth condition but then rapidly disappeared between day three and four. The depletion of HS- corresponds to a cessation in cell production, suggesting that the decrease was due to inactivity of cells (Fig. 3C-D). HS- is readily oxidized by O2 at circumneutral pH64,65, suggesting that the decrease could be attributed to abiotic oxidation. It is unlikely that Hydrogenobacter RSW1 is responsible for the decrease in HS- considering that experiments failed to demonstrate this capability in this strain (Eq. 1; see above). Rather, abiotic control experiments indicated that the Ni2+ and Co2+ ions (and to a lesser extent Fe2+ ions) present in the SL-10 trace metals used to cultivate Hydrogenobacter RSW1 catalyzed the oxidation of HS- and that this required and consumed O2 (see Supplementary Results in the Supplemental Material file, Supplementary Fig. 7).

To further investigate whether anaerobic conditions developed in reactors resulting in H2-oxidizing cells switching from O2 reduction (Eq. 4) to S0 reduction (Eq. 5), as opposed to simultaneous reduction of O2 and S0 (Eqs. 4 and 5), growth experiments containing 2% O2 with or without S0 (Fig. 3C, D) were repeated and headspace O2 concentrations were determined every 24 h prior to replacing the headspace with H2/CO2/O2 to specified concentrations. HS- and/or cell production in both growth conditions (Fig. 4A, B) were similar to what was measured previously (Fig. 3C, D). In both culture conditions, the concentration of O2 in the headspace decreased during the incubation period (Fig. 4C). In the H2/O2 condition (Eq. 4), the rate of O2 consumption was faster than in the H2/O2/S0 condition, which was reflected in the production of more cells in the former condition relative to the latter condition between days 0 and 1. The slower rate of cell production when S0 was present indicates that S0 affects the coupling of H2 oxidation to O2 reduction. Alternatively, the inoculum for this experiment was H2/O2-grown cells, which may have led to the longer lag in H2/O2/S0-grown cultures. Between days 1 and 2, nearly 1.2 mM of HS- was produced in H2/O2/S0-grown cultures, which is attributable to S0 reduction, and the rate of cell production was faster than in H2/O2-grown cultures. In both growth conditions, O2 concentrations were depleted from 2% to <0.3% (limit of detection) between 1 and 2 days of incubation (Fig. 4C). No increase in SO42- concentration was detected in these conditions (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating that these cells are not growing via S0 oxidation (Eq. 2) or through the disproportionation of S0 (Eq. 6). This shows that O2 likely became limiting and the presence of S0 allowed for additional H2 oxidation and growth. However, these data do not indicate that O2 was depleted before S0 reduction occurred.

Growth experiments were conducted in cultures provided with hydrogen (H2) and 2% O2 or with H2, 2% O2 and S0 with daily amendments to maintain O2 at the specified concentrations (A–C) or with more frequent exchange between 24–48 h (D–F). Total aqueous sulfide (H2S/HS-/S2-) was determined before and after headspace exchange and thus accounts for its loss during headspace exchange (panels A and D). O2 measurements were taken prior to headspace adjustments (C and F). Dashed line in panel C represents the limit of detection. SO42− was not produced in experiments containing S0 (Supplementary Fig. 8). All cultures were provided with ~150 μM SO42− as a sulfur source and were incubated on their sides at 70 °C on a shaking incubator (50 revolutions per minute). The average and standard deviation of four replicate (A–C) and three replicate (panels D–F) cultures is shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine if HS- production in H2/O2/S0 conditions is due to depletion of O2 through H2 oxidation (Eq. 4) followed by the reduction of S0 (Eq. 5) or whether reduction of substrates occurs simultaneously, the same experiment with 2% O2, S0, and H2 described above was initiated, but with the headspace being exchanged more frequently at 24, 38, and 48 h (Fig. 4D–F). The rates of cell production and O2 consumption were similar to previous experiments, although only 400 μM of HS- accumulated (Fig. 4D). This is attributable to the higher concentration and total amount of O2 in these experiments. Importantly, the concentration of O2 decreased in the headspace as cell and HS- concentrations increased (Fig. 4E, F). Together, these data indicate that Hydrogenobacter RSW1 simultaneously catalyzed the H2-dependent reduction of S0 and O2 (via Eqs. 4 and 5). It is suggested that this hybrid aerobic-anaerobic metabolism may have been overlooked in Aquificales (and possibly other microorganisms) in previous studies due to efficient abiotic oxidation of HS- by trace elements in the growth medium used to cultivate cells.

Impact of H2 concentration on S0 metabolism

To better understand S0 reduction activity in cultures of Hydrogenobacter RSW1, experiments were established to vary H2 concentrations in cultures while keeping O2 concentrations constant. Headspace H2 concentrations of 0%, 10% and 20% vol./vol. were tested while keeping the headspace O2 concentration at 2% vol./vol. All experiments contained the same amount of S0 and had a N2 headspace with 20% CO2 that was amended with H2 and O2 to meet the target concentrations. When given 0% H2, 2% O2, and S0, HS- was not detected (Fig. 5A), while nearly 700 μM of SO42- was produced (Fig. 5B), indicating S0 oxidation activity (Eq. 2). In this growth condition, the cell concentration increased from 8.0 x 105 cells mL− 1 to 1.1 x 107 cells mL− 1 (Fig. 5C). In contrast, cultures provided with 10% or 20% H2, 2% O2, and S0, produced roughly 1 mM and 2.5 mM of HS-, respectively (Fig. 5A), with minimal increases in SO42- ( ~ 150 µM) (Fig. 5B). Cell concentrations increased from 8.27 × 105 cells mL− 1 to 2.13 × 107 cells mL− 1 at 10% H2 and from 7.91 × 105 cells mL− 1 to 2.73 × 107 cells mL− 1 at 20% H2 (Fig. 5C). The maximum cell concentrations in the H2-containing growth experiments were significantly higher than in those conducted in the absence of H2 (Fig. 5C). Despite minimal increases in SO42− (~ 150 to 200 µM over 8 days incubation) measured in the 10% and 20% vol./vol. H2, S0, and 2% vol./vol. O2 conditions, the amount produced cannot explain the increase in cell production and is non-stoichiometric with the amount of HS− produced that would be predicted for S0 disproportionation (Eq.6; 3 HS− to 1 SO42−), consistent with the lack of known disproportionating enzymes encoded in the RSW1 genome. These data indicate that H2 stimulated activity in the presence of S0 and O2 and further suggests that cells were simultaneously reducing S0 and O2 with H2, as discussed above. It is also possible that cells were also oxidizing S0 (Eq. 2), albeit at a minimal level. If true, this would indicate that simultaneous reduction of S0 and O2 is occurring during simultaneous oxidation of H2 and S0, adding further to the metabolic complexity of RSW1.

Total sulfide (H2S/HS-/S2-; panel A) concentration, sulfate (SO42-; panel B) concentration, and cell concentration (panel C) were measured in cultures provided with S0 and 2% vol./vol. O2 in the headspace with specified amounts of H2 (vol./vol. in headspace). All cultures were provided with 150 μM SO42- as a sulfur source and cultures were incubated on their sides at 70 °C on a shaking incubator (50 revolutions per minute). The average and standard deviation of triplicate cultures is indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Combined Impact of H2 and O2 concentrations on S0 metabolism

To begin to bracket the concentrations of O2 and H2 that dictate the mode or directionality of S0 metabolism in Hydrogenobacter RSW1, cultures were provided with S0, 5% vol./vol. O2, and H2 at headspace concentrations of 0%, 10%, and 20% vol./vol. At 0% and 10% vol/vol. H2, HS- was not detected while over 1 mM of SO42- was produced in both conditions (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B). In these growth conditions, the concentration of cells increased from 1.19 ×106 and 1.27 × 106 to 2.13 × 107 and 6.42 × 107 cells mL− 1, respectively, indicating that cells are coupling aerobic oxidation of S0, per Eq. 2, to growth (Supplementary Fig. 9C). It is not known if the cells are also oxidizing H2 in these conditions (Eq. 4), although the higher cell concentration reached when H2 is present suggests that H2 stimulated growth even when cells were oxidizing S0. In contrast, in cultures grown with S0, 20% vol/vol. H2 and 5% vol/vol. O2, a total of ~550 μM of HS- was produced while no significant increase in SO42- was detected (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B). The concentration of cells increased from 1.24 × 106 to 1.23 × 108 cells mL− 1 in this growth condition (Supplementary Fig. 9C). The production of HS- and cells without production of SO42- indicates that H2 oxidation is being coupled to the simultaneous reduction of S0 and O2 (Eqs. 4 and 5). Collectively these data indicate that the availability of both O2 and H2 impact the mode of S0 metabolism in RSW1. At 10% H2, the mode of S0 metabolism by cultures of RSW1 is dependent on the concentration of O2, whereby cells reduced S0 at ≤2% O2 but oxidize S0 at ≥5% O2. In contrast, at 20% H2, cultures of RSW1 reduced S0 regardless of the O2 concentration (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 9). These data also suggest that regardless of whether cells are oxidizing or reducing S0, the presence of H2 has a stimulatory effect on growth of cells, resulting in higher cell concentrations when incubations contain any amount of H2 (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 9).

Cell Viability and ATP production in H2/S0 reducing cells

To determine whether anaerobic S0 reduction provides cells a benefit despite a lack of increase in cell concentration, live/dead staining was used to examine the viability of cells under three different conditions: H2/S0, N2/S0, and H2 only. After four days of incubation at 70 °C, the total number of cells and those that were deemed viable via live/dead staining differed markedly under the various growth conditions. The total number of cells decreased by 5.44 × 105 cells mL− 1 (37%), 8.17 × 105 cells mL− 1 (56%), and 1.11 × 106 cells mL− 1 (76%) following four days incubation in the presence of H2/S0, N2/S0, or H2 only (Fig. 6A). Of the total cells remaining after four days of incubation, cells that remained viable decreased by 4.77 × 105 cells mL− 1 (40%), 9.46 × 105 cells mL− 1 (80%), and 9.63 × 105 cells mL− 1 (81%) in H2/S0, N2/S0, or H2 respectively (Fig. 6A). Together, these data indicate that cells provided with the H2 and S0 have a clear advantage over the other conditions, with the highest percentage of live cells remaining after four days of incubation. This indicates that the H2/S0 redox couple is providing a physiological benefit to cells in the absence of O2.

Cell concentration and cell viability (panel A) were quantified in cultures grown with hydrogen (H2) and elemental sulfur (S0), with S0 only, or with H2 only over 4 days of incubation. The production of cells and their viability was determined using live/dead staining and fluorescent microscopy (panel A). ATP content of cells following 4 days of incubation as determined using a firefly luciferase assay (panel B). Individual replicates are shown as black circles. All cultures were provided with 150 μM SO42- as a sulfur source and were incubated on their sides at 70 °C on a shaking incubator (50 revolutions per minute). The average and standard deviation of measurements of triplicate cultures is indicated. Abbreviations: BD, below detection. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Given the membrane-associated nature of the Hyd-Sre complex (Fig. 2), it is possible that the metabolism of the H2 and S0 couple allows for the generation of an electrochemical potential that can be used to drive ATP synthesis. While experiments were not done to directly measure the electrochemical potential in cells grown with H2/S0, N2/S0, or H2 only, an experiment was performed to quantify the concentration of ATP in cells following four days of incubation at 70 °C. The only cells that had detectable ATP above background values were those provided with H2 and S0 (Fig. 6B). It should be noted that RSW1 cells were difficult to lyse, and the ATP measurements reported herein should be regarded as qualitative. Nonetheless, the production of ATP in cultures provided with H2 and S0 and the lack of detectable ATP in the other growth conditions suggests that RSW1 can respire S0 with H2. Why the H2/S0 redox couple cannot support growth is not clear given that it can support growth in other cells. Nevertheless, the H2/S0 redox couple clearly provides an energetic benefit to the cells, both in the presence and absence of O2.

Transcriptional regulation of S0 and O2 metabolism in RSW1

The apparent simultaneous H2-dependent respiration of S0 and O2 by Hydrogenobacter RSW1 suggests complex regulation of sre and/or cox used to metabolize S0 and O2, respectively. To begin to investigate the transcriptional regulation of genes involved in these processes, primers were designed for genes of interest (GOI), including the alpha subunit of sulfur reductase (sreA) and two isoforms of subunit 1 of cytochrome c oxidase (cox1 and cox2). Autotrophically grown cells were cultivated under three different conditions (H2 + O2; H2 + 2% O2 + S0, and H2 + 5% O2 + S0) with headspace exchange to prevent O2 limitation (Fig. 3C, D. Fig. 4). RNA was not recovered from cultures provided with H2/S0 only, preventing a comparison of expression patterns under this growth condition.

Interestingly, expression of sreA varied only slightly among the conditions and was not upregulated in any conditions compared to rpoB (Fig. 7A), suggesting constitutive expression of sre or possible post-transcriptional regulation. sre and hyd1 are not spatially co-localized in the genome despite being hypothesized to encode proteins that form a membrane-associated complex40,59. This may indicate a lower likelihood that these genes are co-regulated, as opposed to genes that are proximal on the genome. Both cox1 and cox2 were upregulated in both the S0/H2/2%O2 and the S0/H2/5%O2 relative to the H2/2% O2 condition (Fig. 7B, C). In many bacteria, expression of multiple isoforms of cox is regulated by availability of O269. Cells were harvested for RNA during mid log phase, at around 44 h (20 h after the first headspace exchange). Based on growth and activity data presented above (Fig. 4A–C), it is likely that O2 had become limiting in 2% O2/H2 cultures not provided with S0 but was still available in cultures that were provided with 2% O2/H2/S0 or 5% O2/H2/S0. As such O2 limitation could explain the down-regulation of cox in the H2/O2 condition. Nonetheless, co-expression of both sre and cox in cultures grown with H2/S0/O2 supports the conclusion that RSW1 simultaneously respires aerobically and anaerobically through the simultaneous reduction of S0 and O2.

Panels A-C depict the expression of a single gene of interest normalized to RNA polymerase subunit beta (rpoB) transcript copy number for each condition tested. All cultures were provided with 150 μM SO42- as a sulfur source and were incubated on their sides at 70 °C on a shaking incubator (50 revolutions per minute). Cultures were harvested at mid-log phase for RNA extraction and subsequent conversion to cDNA. Data from four replicate cultures are plotted. Box plots show the upper quartile, lower quartile, mean (represented by x), and the median (represented by the solid line). Whiskers represent the maximum and minimum value. There are no outliers in the dataset. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Implications

Data presented here suggests that a strain of Hydrogenobacter (RSW1) isolated from a circumneutral hot spring in YNP sourced by the anoxic deep hydrothermal aquifer is capable of simultaneously respiring aerobically and anaerobically by reducing O2 and S0 with H2 as reductant. Although RSW1 could not couple H2-dependent anaerobic S0 reduction to growth, cells produced HS- in this condition and had higher viability and ATP levels. This indicates that the H2/S0 redox couple is used to generate an electrochemical gradient to power ATP synthesis and thus would represent a selectable fitness advantage in the presence or absence of available O2. These data help to reconcile previous observations in T. ruber and A. aeolicus that indicated HS- production from S0 in aerobically grown cultures28,40. The distribution of Sre is widespread among members of the Aquificales, other Bacteria, and some Archaea59, with 100% of the Thermocrinis genomes, 50% of the Hydrogenobacter genomes, and all Hydrogenivirga genomes (all members of the Aquificaceae) encoding homologs of SreA. This suggests the possibility that this hybrid mode of energy metabolism may extend beyond RSW1, T. ruber, and A. aeolicus to other members of this order and potentially to other organisms encoding Sre. Further, it should be noted that HS- cycling with O2 and trace metals led to rapid oxidation of HS- in cultures grown under optimal, laboratory conditions. In natural environments where growth conditions are typically suboptimal, it is possible that HS- may not accumulate due to quick and efficient abiotic oxidation by trace metals/O2 in what has been referred to as the cryptic sulfur cycle70,71. Given that trace elements such as Ni and Co can be enriched in hot springs72, it is possible that this metabolism could easily be overlooked in these environments due to rapid oxidation of HS-.

A hybrid energy metabolism like that described herein for RSW1 (and extended to T. ruber, A. aeolicus, and possibly other organisms) could be ecologically beneficial to cells that inhabit environments where the supply of oxidants are limited and/or highly variable. The delivery of O2 to hot springs sourced by deep, anoxic fluids is primarily through atmospheric ingassing, which is likely to be limited and variable depending on the amount of turbulence created by gas efflux and the temperature of the spring. Such conditions might select for cells that can maintain an electrochemical potential by respiring lower potential oxidants, such as S0, when higher potential oxidants, such as O2, are temporally not available. For reasons that are not clear, respiration of S0 is not coupled to growth in RSW1. However, when O2 is available, RSW1 continues to respire S0 while respiring O2. Together, these activities would provide additional energy to drive biomass synthesis. This could explain the apparent constitutive expression of sre and upregulation of cox1 and cox2 in cells provided with both S0 and 2% or 5% O2 relative to cells only provided with 2% O2 which likely became limiting. In this model, S0 reduction allows for ATP to be generated to maintain cell viability during periods of anoxia.

Aquificales are often considered to be among the earliest diverging thermophilic Bacteria47,73, with those that are obligate anaerobes (Desulfurobacteriaceae) diverging earlier than obligate microaerophiles (Hydrogenothermaceae, Aquificaceae) (Fig. 1). Observations made here could provide insight into a strategy that enabled anaerobic bacteria to diversify to take advantage of O2 as it became progressively more available. While current paradigms suggest that facultatively anaerobic organisms shift from anaerobic to aerobic respiration when O2 is available to maximize energy gain and to not toxify anaerobic biochemistry, it is possible that the ephemeral nature of O2 in modern hot springs remains reminiscent of early Earth when whiffs of O2 began to enter the biosphere74 and continues to select for organisms adapted to such conditions. It could be a selective disadvantage to cells to wholly shift to aerobic energy metabolism if the bioenergetic costs of such a metabolic shift (i.e., synthesizing new proteins) outweighs the energy gain. Alternatively, it is possible that Sre was acquired after the rise in O2 occurred and has been maintained due to the selective advantage it provides. While simultaneous anaerobic and aerobic respiration has not been suggested or identified prior to this study, this observation is not inconsistent with reports of anaerobic metabolisms (e.g., SO42- reduction) occurring in the presence of O2 (e.g.,75,76,77) and could be a significant oversight in the current understanding of microbial metabolisms. As such, this metabolic strategy has the potential to be widespread among organisms living in dynamic environments, such as hot springs, intertidal zones, and microbial mats due to the selective advantage that it provides for such organisms.

Methods

Sample collection, enrichment, and isolation

Roadside West (RSW; N 44°45'12.7”; W 110°43'40.1”) is in the Nymph Lake area along the Norris-Mammoth Corridor, Wyoming, U.S.A (Supplementary Fig. 1). Field determinations of hot spring pH and temperature were made using a WTW combination pH probe (Weilheim, Germany) and conductivity was measured using a temperature-compensated YSI meter (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH). Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations were measured on-site using a high-temperature PSt3 oxygen dipping probe and a Fibox 4 DO instrument (PreSens, Regensburg, Germany). Total sulfide (H2S/HS-/S2− and acid volatile sulfide; herein termed HS- since this is the most prevalent form at pH 7.067) and ferrous iron (Fe(II)) concentrations in hot spring waters were quantified in the field within a minute of sample collection using Hach sulfide reagents 1 and 2, Hach ferrozine pillows, and a Hach DR/890 field deployable spectrophotometer (Hach Company, Loveland, CO). Waters were not filtered prior to determination of HS- or Fe(II). Water for determination of sulfate (SO42−) and chloride (Cl-) was filtered (0.22 µm) into polypropylene bottles and stored at 4 °C. Upon arrival at the lab, Hach SO42− and Cl- test kits and the Hach DR/890 field deployable spectrophotometer were used to determine concentrations of SO42− and Cl−. Dissolved gas concentrations and additional geochemical analyses of RSW spring water are reported previously43,44.

Roughly 1 g of flocculant sediment from RSW (pH 6.8, 68°C) was collected on June 21, 2017. The sample was collected aseptically using a flame sterilized spatula, transferred to a 70 mL serum bottle, filled with spring water, and capped with a butyl rubber stopper. The slurry was transported back to the lab at ambient temperature ( ~ 21 °C) where it was then used to inoculate enrichment medium. Mineral salts enrichment medium was composed of NH4Cl (0.33 g L−1), CaCl2 • 2H2O (0.1 g L−1), KCl (0.33 g L−1), MgCl2 • 6H2O (0.33 g L−1), Na2SO4 • 10H2O (0.03 g L−1), K2HPO4 (0.1 g L−1), and Tris-HCl (1.0 g L−1), with the pH adjusted to 7.0 using NaOH. All glassware was soaked in trace metal grade 10% nitric acid (10% vol./vol. in MilliQ water) overnight and then rinsed in MilliQ water prior to use in experiments. Fifty-five mL of media was dispensed into 165 mL serum bottles, and these were capped and sealed prior to autoclave sterilization. After autoclaving and while serum bottles were still hot, medium was purged for 20 min with N2 passed over heated (250 °C) and hydrogen (H2)-reduced copper shavings. Unless stated otherwise, the headspace (110 mL) of serum bottles was then adjusted to a final composition of (vol./vol.): 78% H2, 20% carbon dioxide (CO2), and 2% oxygen (O2). Anoxic and filter-sterilized solutions of SL-10 trace metals78 and Wolfe’s Vitamins79 were added using N2-flushed syringes and needles to final concentrations of 2 mL L−1. A serial dilution (ten-fold) enrichment experiment was conducted using 5.0 mL of the sediment-spring water slurry as the initial inoculum. Enrichment progress was monitored by enumeration of cells. Briefly, 2 µL of 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 2 µg/mL final concentration) was added to sub-samples of culture that were then incubated at room temperature ( ~ 21 °C) for 15 min. Samples were then treated with detergent [100 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1% (v/v) Tween 80] to disaggregate cells80. Disaggregated and stained cells were filtered onto black polycarbonate filters (0.22 µm) (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and were enumerated using an Evos fluorescent microscope (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). After several transfers of the most dilute enrichment culture, a single morphotype was observed via fluorescence microscopy.

DNA extraction, genome sequencing

Ten milliliters of a log phase culture exhibiting a single morphotype were subjected to centrifugation (4696 x g, 30 min, 4 °C) to pellet cells. DNA was extracted from the pelleted biomass with the MP Bio FastDNA spin kit (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) following manufacturer guidelines and DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA high sensitivity assay kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). Genomic DNA underwent library preparation and was sequenced by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center Sequencing Facility using the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform. Reads were trimmed and down sampled using TrimGalore v.0.6.0 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) and BBMap (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). Trimmed and down sampled reads were then assembled using Spades v.3.14.081 with default parameters. Proteins were predicted and annotated with PROKKA82 using default parameters. These gene predictions were further evaluated using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database83 and the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS)84 to determine potential metabolic pathways and functions encoded by the RSW1 genome. KEGG annotations were further scrutinized manually using National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI) BLASTp and alignment tools. Raw reads were analyzed using the SingleM platform (v.0.15.0) and the ‘pipe’ function with default parameters45 to confirm that the culture is an isolate. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) and average amino acid identity (AAI) between genomes and encoded proteins was calculated using the ANI and AAI calculation tool85.

Phylogenetic distribution of sulfur reductase (Sre) among aquificales genomes

Genomes and MAGs affiliated with the order Aquificales were compiled from the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) and NCBI databases. Additionally, MAGs from sediments collected from 37 hot springs sampled across YNP that vary in temperature and pH86 were included in the analysis. Accession numbers for all MAGs utilized can be found in Supplementary Fig. 2.The markerfinder script (https://github.com/faylward/markerfinder) was then used to search the genomic data for 30 universal marker genes that were aligned with ClustalO (v.1.2.4)87 and concatenated. The concatenated alignment was subject to Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic construction using IQ-Tree88. Model finder plus (MFP) was used to determine the best substitution model for the dataset and 1000 ‘ultrafast’ bootstraps were used to determine branch support. Three different species of Thermotoga were used to root the tree, and tree was visualized and edited using the Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL)89 program. The distribution of sulfur reductase subunit alpha (SreA) homologs was determined via BLASTp analysis against each genome or MAG using SreA from Aquifex aeolicus (WP_010880782.1;40) as a query with e-value cut-off set at 10−80 and query coverage set to 70.

Growth conditions and quantification

Mineral salts medium, prepared as described above, was used in all cultivation experiments. The final headspace gas composition for anaerobic growth experiments was (vol./vol.): 80% H2 and 20% CO2. For aerobic growth experiments, the amount of CO2 in the headspace remained constant (20% vol./vol.) but the amount of O2 in the headspace was adjusted as specified, while H2 concentrations were adjusted to balance the O2 concentrations, unless otherwise noted. Serum bottles amended with S0 were prepared using a modified protocol from what is described above to avoid melting the mineral (melting point is ~ 112 °C). Instead of capping bottles prior to autoclaving, bottles were covered with aluminum foil and were autoclaved alongside new butyl rubber stoppers. After autoclaving but while still hot, S0 (baked at 100 °C for 24 h) was added to a final concentration of 5 g L− 1. Bottles were immediately capped and sealed with autoclaved rubber stoppers and crimp caps, and the medium was immediately purged with filtered N2 as described above. Wolfe’s vitamin solution and SL-10 trace metal solution were added prior to inoculating as described above. HS- and thiosulfate (S2O32−) oxidation growth experiments were conducted in an 80/20% vol./vol. N2/CO2 headspace with 2% vol./vol. O2 and were provided with 500 µM Na2S as the HS- source or 1 mM Na2S2O3 as the S2O32− source, respectively. All experiments were incubated at 70 °C on their side on a shaking platform incubator (50 rpm) to increase infusion of headspace gases into the medium, unless otherwise noted. The net production of total HS− during growth was quantified using the methylene blue assay90 on subsamples of unfiltered culture. SO42- concentrations were determined using a turbidimetric assay91 on subsamples of unfiltered culture. Cell concentration was determined microscopically as described above. O2 concentrations in the headspace were measured via gas chromatography by injecting 0.25 mL of gas into an injector valve set at 125 °C in a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a 2.0 M x 1/8” Molecular Sieva 5 A 60/80 column (Ohio Valley Specialty Company, Marietta, OH) with the oven temperature set to 40 °C. O2 was measured using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) set to 150 °C with ultrahighpurity (UHP) argon as the carrier gas. Peak height for samples was converted to percent using a standard curve generated with UHP O2 (EGas Depot, Largo, FL). Abiotic S0 reducing experiments (Supplementary Fig. 5) were prepared as described above, were uninoculated, and were incubated at 70 ⁰C. Methods for abiotic HS- oxidation experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7) can be found in the Supplemental Materials file.

Cell viability experiments and ATP assays

Cell viability experiments were conducted by incubating Hydrogenobacter RSW1 cells under three different conditions: 1) H2 + S0, 2) N2 + S0, or 3) H2 only. Base salts growth medium was prepared as described above. The carbon source in all experiments was CO2 at a final concentration of 20% (vol./vol.) in the headspace. Where indicated, H2 was added to a final concentration of 80% (vol./vol.) in the headspace, S0 was provided to a final concentration of 5 g L− 1, and N2 was added to a final concentration of 80% (vol./vol.) in the headspace. To determine the viability of cells in each of the three conditions, a LIVE/DEAD stain (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) was used following manufacturer’s protocols. Cells were counted on an EVOs M5000 fluorescent microscope (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using the overlay function and GFP and Texas Red light cubes (Life Technologies). On the fourth day of incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation (4696 x g, 35 min, 4 °C). Supernatant was discarded and pellets were used for ATP quantification. Briefly, 500 µL of sterile media was added to pellets and they were resuspended by gentle vortexing. Resuspended cells were transferred to Lysis E Matrix bead beating tubes (MP Biomedicals). Five hundred µL of phenol/chloroform (1:1 ratio) was added to each tube and tubes were subjected to ballistic bead beating (Mini-BeadBeater 16, Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for 20 s to promote cell lysis. Tubes containing lysates were then transferred to a pre-cooled centrifuge (4 °C) and were spun for 5 min at 14,000 x g (4 °C) to separate the aqueous phase. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a sterile microcentrifuge tube for ATP quantification.

An ATP quantification kit employing firefly luciferase (Invitrogen) was used following manufacturer’s guidelines with a slight modification to the working solution. To increase assay sensitivity, 3.5 µL of luciferase was added to the ATP working solution as opposed to 2.5 µL. ATP was quantified by adding 270 µL of ATP working solution to a nitric acid washed glass test tube. Thirty µL of sample was added and mixed by gently pipetting up and down and incubated at room temperature for one minute. Following incubation, test tubes were placed in a luminometer (Lu-mini, Vitl Life Solutions, Ashland, VA) and measurements were recorded. Background assays were performed in triplicate using blank medium treated the same as samples and values were subtracted from experimental samples. A standard curve to relate ATP concentration to luminescence was generated using an ATP stock (Invitrogen) and the same volumes and ATP working solution described above.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Mid-log phase cultures of Hydrogenobacter RSW1 were harvested by filtration using an autoclaved glass filter tower. Cells were filtered onto 47 mm diameter, 0.2 µm pore size filters (Pall, Port Washington, NY). Filters were then placed into sterile 50 mL Falcon tubes and 750 µL of TRIzol extraction reagent (Invitrogen) was then added. The filtered biomass and TRIzol were then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Detailed instructions for TRIzol extractions can be found in Supplemental Material. RNA was quantified using the Qubit BR RNA quantification kit (Invitrogen) and was quality checked using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The absence of PCR-amplifiable DNA was confirmed by PCR amplification using universal 16S rRNA primers (515 F (5’- GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’) and 806 R (5’- GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT’)) and was visualized through gel electrophoresis. The thirty five cycle PCR was conducted at an annealing temperature of 50 °C with 5 µL of template. After confirming the quality of RNA and the absence of PCR amplifiable DNA, RNA was converted into cDNA using the iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

qPCR

cDNA was subject to quantitative PCR (qPCR) using four different primer sets designed using the NCBI Primer BLAST tool. Each primer set was designed to amplify a specific gene of interest (GOI), including primers for the rpoB subunit, sulfur reductase subunit A (sreA), and cyctochrome c oxidase subunit 1 genes (cox1, cox2). Primer sequences, the genes they target, and primer annealing temperatures are reported in Supplementary Data 1. qPCR was conducted using the SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in a final volume of 20 μL. One μL of cDNA product and 0.5 µL of both the forward and reverse primers (10 mM stock concentration) were added to each reaction and reactions were subject to the following cycling conditions in the CFX Connect Real-time system (Bio-Rad): Initial denaturing at 95 °C for one minute, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at specified temperature (Supplementary Data 1) for one minute, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a plate read step at the end of each cycle. This was followed by a melt curve from 65–95 °C with 0.5 °C increases every 5 s. Details for creating plasmid standards can be found in the Supplemental Materials document. Negative control qPCR reactions were performed in the absence of added cDNA.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the text and figures of this published article and its Supplementary Materials. Raw values for all figures in the manuscript and supplemental materials can be found in the Source Data file. RSW1 genomic sequencing is available through NCBI under Biosample accession number SAMN40709733. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Reysenbach, A.-L. et al. Aquificales in Yellowstone National Park. (2006).

Takacs-vesbach, C. et al. Metagenome sequence analysis of filamentous microbial communities obtained from geochemically distinct geothermal channels reveals specialization of three Aquificales lineages. Fron. Microbiol. 4, 84 (2013).

Hou, W. et al. A comprehensive census of microbial diversity in hot springs of Tengchong, Yunnan Province China using 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. PLoS One 8, e53350 (2013).

Song, Z.-Q. et al. Bacterial and archaeal diversities in Yunnan and Tibetan hot springs, China. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 1160–1175 (2013).

Colman, D. R. et al. Tectonic and geological setting influence hot spring microbiology. Environ. Microbiol. 25, 2481–2497 (2023).

Brock, T. D. Thermophilic Microorganisms and Life at High Temperatures. (Springer-Verlag, 1978).

Castenholz, R. W. The thermophilic Cyanophytes of Iceland and the upper temperature limit J. Phycol 5, 360–368 (1969).

Huber, R. & Eder, W. in The Prokaryotes: Volume 7: Proteobacteria: Delta, Epsilon Subclass (eds Martin Dworkin et al.) 925-938 (Springer New York, 2006).

L’Haridon, S. et al. Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel autotrophic, sulphur-reducing bacterium isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. IJSEM 48, 701–711 (1998).

Nakagawa, S. et al. Sulfurihydrogenibium yellowstonense sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, facultatively heterotrophic, sulfur-oxidizing bacterium from Yellowstone National Park, and emended descriptions of the genus Sulfurihydrogenibium, Sulfurihydrogenibium subterraneum and Sulfurihydrogenibium azorense. IJSEM 55, 2263–2268 (2005).

Takai, K., Kobayashi, H., Nealson, K. H. & Horikoshi, K. Sulfurihydrogenibium subterraneum gen. nov., sp. nov., from a subsurface hot aquifer. IJSEM 53, 823–827 (2003).

Kawasumi, T., Igarashi, Y., Kodama, T. & Minoda, Y. Hydrogenobacter thermophilus gen. nov. sp., an extremely thermophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium. IJSEM 34, 5–10 (1984).

Takai, K., Komatsu, T. & Horikoshi, K. Hydrogenobacter subterraneus sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, heterotrophic bacterium unable to grow on hydrogen gas, from deep subsurface geothermal water. IJSEM 51, 1425–1435 (2001).

Aguiar, P., Beveridge, T. J. & Reysenbach, A.-L. Sulfurihydrogenibium azorense, sp. nov., a thermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing microaerophile from terrestrial hot springs in the Azores. IJSEM 54, 33–39 (2004).

Suzuki, M., Cui, Z. J., Ishii, M. & Igarashi, Y. Nitrate respiratory metabolism in an obligately autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenobacter thermophilus TK-6. Arch. Microbiol. 175, 75–78 (2001).

Kawasumi, T., Igarashi, Y., Kodama, T. & Minoda, Y. Isolation of strictly thermophilic and obligately autotrophic hydrogen bacteria. Agric. Biol. Chem. 44, 1985–1986 (1980).

McCleskey, R. B., Ball, J. W., Nordstrom, D. K., Holloway, J. M. & Taylor, H. E. Water-chemistry data for selected springs, geysers, and streams in Yellowstone National Park Wyoming, 2001-2002. Report No. 2004-1316, (2005).

Nye, J. J., Shock, E. L. & Hartnett, H. E. A novel PARAFAC model for continental hot springs reveals unique dissolved organic carbon compositions. Org. Geochem. 141, 103964 (2020).

Fournier, R. O. Geochemistry and dynamics of the Yellowstone National Park hydrothermal system. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 17, 13–53 (1989).

Nordstrom, K. D., McCleskey, B. R. & Ball, J. W. Sulfur geochemistry of hydrothermal waters in Yellowstone National Park: IV Acid–sulfate waters. Appl. Geochem. 24, 191–207 (2009).

Nordstrom, D. K., McCleskey, B. R. & Ball, J. W. Ground water to surface water: chemistry of thermal outflows in Yellowstone National Park. In Geothermal Biology and Geochmistry in Yellowstone National Park (eds Inskeep, W. P. & McDermott, T. R.) 73–94 (Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA, 2005).

Donahoe-Christiansen, J., D’Imperio, S., Jackson, C. R., Inskeep, W. P. & McDermott, T. R. Arsenite-oxidizing Hydrogenobaculum strain isolated from an acid-sulfate-chloride geothermal spring in Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1865–1868 (2004).

Romano, C. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of phylogenetically closely related Hydrogenobaculum sp. ssolates from Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 2932–2943 (2013).

Stohr, R., Waberski, A., Völker, H., Tindall, B. J. & Thomm, M. Hydrogenothermus marinus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, recognition of Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum as a member of the genus Hydrogenobacter and proposal of the reclassification of Hydrogenobacter acidophilus as Hydrogenobaculum acidophilum gen. nov., comb. nov., in the phylum ‘Hydrogenobacter/Aquifex’. IJSEM 51, 1853–1862 (2001).

D’Imperio, S. et al. Relative Importance of H2 and H2S as Energy Sources for Primary Production in Geothermal Springs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5802–5808 (2008).

Caldwell, S. L., Liu, Y., Ferrera, I., Beveridge, T. & Reysenbach, A.-L. Thermocrinis minervae sp. nov., a hydrogen- and sulfur-oxidizing, thermophilic member of the Aquificales from a Costa Rican terrestrial hot spring. IJSEM 60, 338–343 (2010).

Dodsworth, J. A., Ong, J. C., Williams, A. J., Dohnalkova, A. C. & Hedlund, B. P. Thermocrinis jamiesonii sp. nov., a thiosulfate-oxidizing, autotropic thermophile isolated from a geothermal spring. IJSEM 65, 4769–4775 (2015).

Huber, R. et al. Thermocrinis ruber gen. nov., sp. nov., a pink-filament-forming hyperthermophilic bacterium isolated from Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3576–3583 (1998).

Havig, J. R., Raymond, J., Meyer-Dombard, D. A. R., Zolotova, N. & Shock, E. L. Merging isotopes and community genomics in a siliceous sinter-depositing hot spring. J. Geophys. Res: Biogeosci. 116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JG001415 (2011).

Meyer-Dombard, D. R. et al. Hydrothermal ecotones and streamer biofilm communities in the Lower Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 2216–2231 (2011).

Gardner, W. P., Susong, D. D., Solomon, D. K. & Heasler, H. P. Using environmental tracers and numerical simulation to investigate regional hydrothermal basins—Norris Geyser Basin area, Yellowstone National Park, USA. J. Geophys. Res: Solid Earth 118, 2777–2787 (2013).

Sims, K. W. W. et al. The dynamic influence of subsurface geological processes on the assembly and diversification of thermophilic microbial communities in continental hydrothermal systems. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 362, 77–103 (2023).

Colman, D. R. et al. Ecological differentiation in planktonic and sediment-associated chemotrophic microbial populations in Yellowstone hot springs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92 https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiw137 (2016).

Fernandes-Martins, M. C. et al. Ecological dichotomies arise in microbial communities due to mixing of deep hydrothermal waters and atmospheric gas in a circumneutral hot spring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e01598–01521 (2021).

Power, J. F. et al. Microbial biogeography of 925 geothermal springs in New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 9, 2876 (2018).

Cole, J. K. et al. Sediment microbial communities in Great Boiling Spring are controlled by temperature and distinct from water communities. ISME J. 7, 718–729 (2013).

Power, J. F. et al. A genus in the bacterial phylum Aquificota appears to be endemic to Aotearoa-New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 15, 179 (2024).

Keller, L. M., Colman, D. R. & Boyd, E. S. An active microbiome in Old Faithful geyser. PNAS Nexus 2 https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad066 (2023).

Deckert, G. et al. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature 392, 353–358 (1998).

Guiral, M. et al. A membrane-bound multienzyme, hydrogen-oxidizing, and sulfur-reducing complex from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42004–42015 (2005).

Ball, J. W. et al. Water-chemistry data for selected springs, geysers, and streams in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 1999-2000. Report No. 2002-382, (Reston, VA, 2002).

Wilson, C. L., Hinman, N. W., Cooper, W. J. & Brown, C. F. Hydrogen peroxide cycling in surface geothermal waters of Yellowstone National Park. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 2655–2662 (2000).

Fernandes-Martins, M. C., Colman, D. R. & Boyd, E. S. Relationships between fluid mixing, biodiversity, and chemosynthetic primary productivity in Yellowstone hot springs. Environ. Microbiol. 25, 1022–1040 (2023).

Lindsay, M. R. et al. Subsurface processes influence oxidant availability and chemoautotrophic hydrogen metabolism in Yellowstone hot springs. Geobiology 16, 674–692 (2018).

Woodcroft, B. J. et al. SingleM and Sandpiper: Robust microbial taxonomic profiles from metagenomic data. bioRxiv, 2024.2001.2030.578060 https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.30.578060 (2024).

Kryukov, V. R., Savel’eva, N. D. & Pusheva, M. A. Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum new genus new species an extreme thermophilic hydrogen bacterium and its hydrogenase activity. Mikrobiologiya 52, 781–788 (1983).

Oshima, K., Chiba, Y., Igarashi, Y., Arai, H. & Ishii, M. Phylogenetic position of aquificales based on the whole genome sequences of six aquificales species. Int J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 859264 (2012).

Cao, J. et al. Desulfurobacterium indicum sp. nov., a thermophilic sulfur-reducing bacterium from the Indian Ocean. IJSEM 67, 1665–1668 (2017).

Pérez-Rodríguez, I. et al. Phorcysia thermohydrogeniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic, chemolithoautotrophic, nitrate-ammonifying bacterium from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. IJSEM 62, 2388–2394 (2012).

Huber, H., Diller, S., Horn, C. & Rachel, R. Thermovibrio ruber gen. nov., sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, chemolithoautotrophic, nitrate-reducing bacterium that forms a deep branch within the phylum Aquificae. IJSEM 52, 1859–1865 (2002).

Jelen, B., Giovannelli, D., Falkowski, P. G. & Vetriani, C. Elemental sulfur reduction in the deep-sea vent thermophile, Thermovibrio ammonificans. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2301–2316 (2018).

Takai, K., Nakagawa, S., Sako, Y. & Horikoshi, K. Balnearium lithotrophicum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, strictly anaerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing chemolithoautotroph isolated from a black smoker chimney in the Suiyo Seamount hydrothermal system. IJSEM 53, 1947–1954 (2003).

Eder, W. & Huber, R. New isolates and physiological properties of the Aquificales and description of Thermocrinis albus sp. nov. Extremophiles 6, 309–318 (2002).

Hedlund, B. P. et al. Isolation of diverse members of the Aquificales from geothermal springs in Tengchong, China. Front. Microbiol. 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00157 (2015).

Hügler, M., Huber, H., Molyneaux, S. J., Vetriani, C. & Sievert, S. M. Autotrophic CO2 fixation via the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle in different lineages within the phylum Aquificae: evidence for two ways of citrate cleavage. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 81–92 (2007).

Reysenbach, A.-L. et al. Complete and draft genome sequences of six members of the Aquificales. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1992–1993 (2009).

Friedrich, C. G., Bardischewsky, F., Rother, D., Quentmeier, A. & Fischer, J. Prokaryotic sulfur oxidation. Curr. Opini. Microbiol. 8, 253–259 (2005).

Amenabar, M. J., Colman, D. R., Poudel, S., Roden, E. E. & Boyd, E. S. Electron acceptor availability alters carbon and energy metabolism in a thermoacidophile. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2523–2537 (2018).

Laska, S., Lottspeich, F. & Kletzin, A. Membrane-bound hydrogenase and sulfur reductase of the hyperthermophilic and acidophilic archaeon Acidianus ambivalens. Microbiol 149, 2357–2371 (2003).

Søndergaard, D., Pedersen, C. N. S. & Greening, C. HydDB: A web tool for hydrogenase classification and analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 34212 (2016).

Siebers, B. et al. Reconstruction of the central carbohydrate metabolism of Thermoproteus tenax by use of genomic and biochemical data. J. Bacteriol. 186, 2179–2194 (2004).

Siebers, B. et al. The complete genome sequence of Thermoproteus tenax: A physiologically versatile member of the Crenarchaeota. PLOS ONE 6, e24222 (2011).

Dirmeier, R., Keller, M., Frey, G., Huber, H. & Stetter, K. O. Purification and properties of an extremely thermostable membrane-bound sulfur-reducing complex from the hyperthermophilic Pyrodictium abyssi. Eur. J. Biochem. 252, 486–491 (1998).

Luther, G. W. et al. Thermodynamics and kinetics of sulfide oxidation by oxygen: a look at inorganically controlled reactions and biologically mediated processes in the environment. Front. Microbiol. 2 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00062 (2011).

Millero, F. J., Hubinger, S., Fernandez, M. & Garnett, S. Oxidation of H2S in seawater as a function of temperature, pH, and ionic strength. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 439–443 (1987).

Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E. A. Bacterial sulfur reduction in hot vents. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 15, 65–77 (1994).

Amend, J. P. & Shock, E. L. Energetics of overall metabolic reactions of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic Archaea and Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25, 175–243 (2001).

Han, P. & Bartels, D. M. Temperature dependence of oxygen diffusion in H2O and D2O. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 5597–5602 (1996).

Hirai, T., Osamura, T., Ishii, M. & Arai, H. Expression of multiple cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase isoforms by combinations of multiple isosubunits in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 12815–12819 (2016).

Canfield, D. E. et al. A Cryptic Sulfur Cycle in Oxygen-Minimum–Zone Waters off the Chilean Coast. Science 330, 1375–1378 (2010).

Mills, J. V., Antler, G. & Turchyn, A. V. Geochemical evidence for cryptic sulfur cycling in salt marsh sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 453, 23–32 (2016).

McCleskey, R. B., et al. (Geological Survey Online Database, 2014).

Burggraf, S., Olsen, G. J., Stetter, K. O. & Woese, C. R. A Phylogenetic Analysis of Aquifex pyrophilus. Sys. Appl. Microbiol. 15, 352–356 (1992).

Anbar, A. D. et al. A Whiff of Oxygen Before the Great Oxidation Event? Science 317, 1903–1906 (2007).

Canfield, D. E. & Des Marais, D. J. Aerobic Sulfate Reduction in Microbial Mats. Science 251, 1471–1473 (1991).

Hastings, D. & Emerson, S. Sulfate reduction in the presence of low oxygen levels in the water column of the Cariaco Trench1,2. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 391–396 (1988).

Marschall, C., Frenzel, P. & Cypionka, H. Influence of oxygen on sulfate reduction and growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 159, 168–173 (1993).

Widdel, F., Kohring, G.-W. & Mayer, F. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. Arch. Microbiol. 134, 286–294 (1983).

Atlas, R. M. Handbook of Microbiological Media: Second Edition. (CRC-Press, 1996).

Morono, Y., Terada, T., Kallmeyer, J. & Inagaki, F. An improved cell separation technique for marine subsurface sediments: applications for high-throughput analysis using flow cytometry and cell sorting. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 2841–2849 (2013).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Moriya, Y., Itoh, M., Okuda, S., Yoshizawa, A. C. & Kanehisa, M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W182–W185 (2007).

Rodriguez-R, L. & Konstantinidis, K. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.1900v1 (2016).

Colman, D. R. et al. Covariation of hot spring geochemistry with microbial genomic diversity, function, and evolution. Nat. Commun. 15, 7506 (2024).

Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high‐quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 (2011).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2014).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 293–296 (2021).

Moest, R. R. Hydrogen sulfide determination by the methylene blue method. Anal. Chem. 47, 1204–1205 (1975).

Kolmert, Å., Wikström, P. & Hallberg, K. B. A fast and simple turbidimetric method for the determination of sulfate in sulfate-reducing bacterial cultures. J. Microbiol. Methods 41, 179–184 (2000).

Acknowledgements