Abstract

Dielectric capacitors with high energy storage performance are highly desired for advanced power electronic devices and systems. Even though strenuous efforts have been dedicated to closing the gap of energy storage density between the dielectric capacitors and the electrochemical capacitors/batteries, a single-minded pursuit of high energy density without a near-zero energy loss for ultrahigh energy efficiency as the grantee is in vain. Herein, for the purpose of decoupling the inherent conflicts between high polarization and low electric hysteresis (loss), and achieving high energy storage density and efficiency simultaneously in multilayer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs), we propose an interlaminar strain engineering strategy to modulate the domain structure and manipulate the polarization behavior of the dielectric mediums. With a heterogeneous layered structure consisting of different antiferroelectric ceramics [(Pb0.9Ba0.04La0.04)(Zr0.65Sn0.3Ti0.05)O3/(Pb0.95Ba0.02La0.02)(Zr0.6Sn0.4)O3/(Pb0.92Ca0.06La0.02)(Zr0.6Sn0.4)0.995O3], our MLCC exhibits a giant recoverable energy density of 22.0 J cm−3 with an ultrahigh energy efficiency of 96.1%. Combined with the favorable temperature and frequency stabilities and the high antifatigue property, this work provides a strain engineering paradigm for designing MLCCs for high-power energy storage and conversion systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Storing electric energy in the form of electrostatic fields against electric displacement, the unmatched high-speed charge-discharge capability makes dielectric capacitors indispensable for high/pulsed power electronic systems1,2,3. Nevertheless, the low energy storage density of dielectric capacitors in comparison to that of electrochemical capacitors and batteries is blamed for limiting the miniaturization and lightweight of power devices4. The recoverable energy density is determined by the polarization behavior of the dielectric materials of capacitors, i.e., \({W}_{{{{\rm{rec}}}}}={\int }_{{P}_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}}^{{P}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}}E{{{\rm{d}}}}P\), where Pm is the electric polarization stimulated by the applied electric field E, and Pr is the remanent polarization, and thus large polarization and high breakdown strength are pivotal to achieving desirable energy storage density5,6,7,8. The spontaneous polarizability enables ferroelectrics (FEs) and antiferroelectrics (AFEs) to exhibit much higher polarization compared with that of linear dielectrics, which have been extensively used as energy storage mediums for capacitors6,9. Concerning E, the breakdown strength of dielectrics is found to increase sharply with the decrease in the thickness of dielectric ceramics (the Gerson-Marshall theory)10,11. For high energy density, capacitors with a multilayer structure (MLCC) have been designed, in which FE or AFE ceramics with high polarization are laminated with thin thicknesses ranging from several to several tens micrometers for high breakdown strength12,13,14.

Even though improved energy storage capacity has been achieved in MLCCs, their energy density is still miles off that of other energy storage devices such as batteries and supercapacitors, forcing strenuous efforts to be continuously dedicated to enhancing the polarization and breakdown strength of the FE and AFE materials. However, from the practical point of view, a single-minded pursuit of high energy storage density without a near-zero energy loss for ultrahigh energy efficiency [η=Wrec/(Wrec+Wloss)×100%, where Wloss is the energy loss generated by the electric hysteresis and leakage current] as the grantee is in vain, which, unfortunately, has not been fully recognized. The energy loss could generate colossal heat and elevate the temperature of MLCCs pronouncedly due to their compact size and low heat dissipation ability15,16,17,18,19. Taking strontium titanate-based MLCC (4.5 mm × 3.2 mm × 1.6 mm) with an energy storage density of ~2 J cm−3, only one-tenth that of the state-of-art value reported in MLCCs, for example, an energy loss of 0.4 J cm−3 (η ~ 80%) could result in a temperature rise of ~80 °C [ref. 20]. It is noted that the energy loss increases proportionally to the energy storage density with the same efficiency, and thus the overheating issue could be significantly amplified in MLCCs with high energy density, further confirming the paramount importance of energy efficiency. According to the energy conservation law (Supplementary Note S1)21,22,23, even with a decent efficiency of 85%, the heat generated by the energy loss (~2 J cm−3) of an MLCC with an energy density of ~15 J cm−3 could lead to a temperature rise as high as 200 °C, severely exceeding the temperature range for a stable energy storage performance24. To restrict the rise of temperature below 50 °C in MLCCs with an energy density beyond 20 J cm−3, the energy efficiency must be greater than 95%. Thus, near-zero energy loss becomes the precondition for MLCCs to enjoy high energy storage density.

However, a high polarization generally concomitants with a large electric hysteresis in FEs and AFEs, and the disharmony could be ascribable to the domain switching thermodynamics25. Indeed, large polarization is the macroscopic representation of the high compliance of dipoles with electric fields, the essence of which involves a series of processes of new domain nucleation, domain wall movement, domain growth and eventually the formation of large single domains with huge electric hysteresis26,27,28,29. Smashing large single domains into nanodomains could decrease the hysteresis, while the large content of domain walls for nanoregion separation hinders the saturation polarization30,31,32. The inherent correlation between the polarization and the hysteresis makes high energy density and ultralow energy loss inaccessible simultaneously33,34,35. For instance, a linear behavior like hysteresis can be achieved in BaTiO3 by breaking the long-range tetragonal phase ordering with the incorporation of aliovalent double ions, yielding a superb energy efficiency of 97% [ref. 33]. Whereas, the compromise of polarization limits the energy storage density to a mediocre level of 8.6 J cm−3. In contrast, alloying with BiMg2/3Nb1/3O3, the thermodynamic free energy density profile of the BiFeO3-based ceramics is flattened to promote a high polarization, allowing the corresponding MLCC to store electric energy with a preferred density of 15.8 J cm−3 [ref. 10]. Nonetheless, the large electric hysteresis consumes 25% of the charged energy, leading to the detrimental energy efficiency of 75%. In addition to manipulating phase structure and polarization behavior of dielectric materials with composition and doping designs, the unique multilayer structure and special fabrication process of MLCCs provide more sophisticated means to improve energy storage performance. Texturing grains with <111 > -oriented SrTiO3 templates during the tape casting process, the breakdown strength of the sodium bismuth titanate MLCCs increases dramatically while the high polarization of the dielectric matrix is maintained, which exhibits an extremely high energy density exceeding 20 J cm−3 for the first time36. However, the inferior energy efficiency of 80% may still challenge the viability of practical applications.

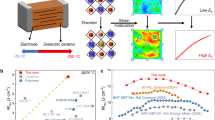

In this work, we proposed a heterogeneous layer structure to optimize the comprehensive energy storage performance of MLCCs. We chose three different AFE compositions (Pb0.9Ba0.04La0.04)(Zr0.65Sn0.3Ti0.05)O3 (PBLZST, abbreviated as S1), (Pb0.95Ba0.02La0.02)(Zr0.6Sn0.4)O3 (PBLZS, abbreviated as S2), and (Pb0.92Ca0.06La0.02)(Zr0.6Sn0.4)0.995O3 (PCLZS, abbreviated as S3) as the dielectric mediums because of their complementary features among polarization, electric hysteresis, and breakdown strength (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1 and Note S2). The three AFEs were laminated and stacked periodically and their ceramic layers were connected parallelly to assemble the MLCCs (Fig. 1a). Due to the electrostrictive effect, we capitalized on the in-plane mismatch strain between the dielectric layers during the charging process to tune the domain size, domain switching behavior and the polarization characteristic of the AFEs (Fig. 1b), and remarkably, the MLCC exhibits an exceptionally low-hysteresis polarization-electric field (P-E) loop with a colossal polarization exceeding 70.0 μC cm−2, simultaneously, which is inaccessible before. We rationalized the special polarization behavior of the MLCC with the phase-field simulations. As a result, stunning energy storage characteristics, i.e., a giant recoverable energy density of 22.0 J cm−3 with an ultrahigh energy efficiency of 96.1% are achieved in our MLCCs. This is the highest recoverable energy density achieved in MLCCs with an efficiency surpassing 95%. Combined with the marvelous temperature and frequency stabilities as well as the antifatigue property, this work defines clear interlaminar strain engineering guidelines for designing MLCCs with supreme overall energy storage performance.

a Schematic of the MLCC (S4) with a periodical heterogeneous layer structure. b Comparative display of domain structures and polarization-electric field (P-E) loops of S1, S2 and S3 with high electric fields. With small domains, S1 and S3 show slim loops with near-zero hysteresis and remanent polarization, while their polarization is also low. In contrast, S2 with large FE domains possesses high polarization but obvious hysteresis. With strain engineering (S4), the in-plane tensile strain decreases the domain size of S2 to depress its hysteresis while the in-plane compressive strain increases the polarization of S1 and S3. With the domain engineering, S4 is expected to exhibit a high polarization like S2 and a near-zero hysteresis similar to S1 and S3 for achieving high energy storage density and efficiency, simultaneously (the P-E loop of S4).

Results

Dielectric and polarization behaviors of MLCCs with the heterogeneous layer structure

Our MLCC (S4) with a periodical heterogeneous layer structure (Fig. 1a) was fabricated with a typical tape-casting process. Meanwhile, MLCCs with S1, S2 and S3 homogeneous dielectric layers were fabricated as the experimental control group. The dimensions of the MLCCs are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. As presented in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, the MLCCs are composed of dense ceramic layers (thickness: 8 μm) that connect parallelly with Ag-Pd internal interdigital electrodes, featuring the clear metal-ceramic interfaces (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S2). The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mappings (cross-section view) for the metal elements of Ag and Pd corroborate that no diffusion of internal interdigital electrode penetrating the dielectric layers occurs (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the homogeneous distribution of Pb, Ba, La, Ca, Zr, Sn and Ti elements in their corresponding ceramic layers [revealed by the submicrometer-scale and atomic-scale elemental mappings (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4) via the aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM)] permits all of the samples to have a pure perovskite phase, as verified by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6 and Table S2) and the electron-diffraction patterns along the [110] zone axes (insets of Fig. 3a–c). Specifically, as indicated by the XRD patterns, S1 shows a tetragonal phase at room temperature as identified by the splitting of (200) and (002) peaks at ~44°, while S2 has an orthorhombic phase implied by the split (200) peak and asymmetric (111) peak37,38. The appearance of (012) and (212) peaks located at ~32° and ~39° infer the orthorhombic phase of S3 [ref. 39].

a Cross-section SEM images of S1-S4 MLCCs. b EDS mappings of Pb and Zr in the dielectric layers, and Ag and Pd in the internal interdigital electrodes (S4 MLCC). c Temperature-dependent dielectric constant and loss of S1-S4 MLCCs. d Room-temperature P-E loops of the samples measured at 10 Hz. e Polarization of S1-S4 MLCCs as a function of electric field.

BF-TEM images of a S1, b S2, and c S3. The insets show the corresponding SAED patterns along the [110] zone axes. Atomic-scale HAADF-STEM images of d S1, e S2, and f S3 along the [110] zone axes. Displacement magnitude distribution histograms of g S1, h S2, and i S3. The insets show the corresponding atomic displacement magnitude mappings. Vector angle distribution histograms of j S1, k S2, and l S3. The insets show the corresponding atomic displacement angle mappings.

Dielectric spectra were characterized to identify the phase transition behavior of the specimens, and the results are shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S7. S1 MLCC has a flat dielectric constant-temperature curve at the low-temperature range and shows a broad dielectric plateau with a dielectric constant of ~1170 in the temperature span from 150 °C to 250 °C corresponding to the diffusive AFE tetragonal (AFET)-paraelectric cubic (PEC) phase transition (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S7a). S3 MLCC has a stable dielectric constant in the whole temperature range from −60 °C to 400 °C with a diffused dielectric anomaly at ~100 °C corresponding to the partial AFE orthorhombic (AFEO)-PEC phase transition39. The full AFEO-PEC phase transition of S3 MLCC occurs at a higher temperature, as denoted by the small hump of the dielectric constant-temperature curve at ~320 °C (Supplementary Fig. S7c). Distinct from the diffusive phase transitions with flat dielectric constant spectra of S1 and S3 MLCCs, the multistage phase transitions of S2 MLCC are signified by the dielectric constant steps at T1 ~ 80 °C, T2 ~ 160 °C, and T3 ~ 300 °C, corresponding to the AFEOI (orthorhombic structure with space group of Pbam)-AFEOII (orthorhombic structure with space group of Bmm2), AFEOII-PEMCC (paraelectric multicell cubic), and PEMCC-PEC phase transitions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S7b)38,40. By integrating the dielectric features of S1, S2 and S3 MLCCs, S4 MLCC exhibits a very broad dielectric constant peak in a large temperature span with a moderate relative dielectric constant (~500–~ 700), indicating the high temperature stability for the polarization behavior and energy storage performance (Supplementary Fig. S7d). The overlap of the dielectric constant curves of each sample tested with various frequencies reflects the nonrelaxation nature of the components. In addition, all of the samples have a low dielectric loss (below 0.03) in the whole temperature and frequency ranges, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. We attribute the preferred dielectric losses to the high and stable resistivity of the samples. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S8, all of the samples have resistivity beyond 1 × 1011 Ω m at room temperature with a DC field of 100 kV cm−1, and even when the temperature increases to a high level of 160 °C, no obvious decrease in resistivity is observed. Owing to the favorable insulating characteristic, all of the MLCCs have a high breakdown strength beyond 450 kV cm−1, especially S3 MLCC exhibits an ultrahigh breakdown strength of 810 kV cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S9). S4 MLCC possesses a preferred breakdown strength of 750 kV cm−1 that is close to the level of S3 MLCC. The high breakdown strength is essential to stimulate the energy storage potential of MLCCs.

Presented in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. S10 are the polarization-electric field (P-E) loops of the samples at room temperature, in which the complementarity of the polarization behavior of S1, S2 and S3 MLCCs can be clearly identified. For example, with a flattening effect of a free-energy profile caused by the local lattice distortion (smaller cations La3+ ions occupy A-sites of the perovskite lattices with the formation of \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{Pb}}}}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\) vacancies), S1 MLCC possesses a very slim P-E double loop with a near-zero remanent polarization and a minimal electric hysteresis41,42. However, the saturate polarization of S1 MLCC ( ~ 55 μC cm−2, Fig. 2d, e) is relatively low. Figure 3d–f shows the atomic-scale high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) lattice polarization vectors along the [110] zone axes (the magnitudes of the arrows represent the deviation displacements of B-site ions relative to the lattice center of their four nearest neighboring A-site ions), and the average displacement of S1 MLCC is only ~3.9 pm (Fig. 3g, accounting from the displacement magnitude mapping in the inset of Fig. 3g), which results in the low polarization of S1. In contrast, a giant polarization of ~77 μC cm−2 is observed in S2 MLCC with a low electric field of 480 kV cm−1, which is one of the highest values in MLCCs with different FE or AFE mediums. The colossal polarization of S2 could be attributed to its large ion displacement. As shown in Fig. 3h, the average displacement is ~4.7 pm, which is 1.2 and 1.5 times those of S1 and S3, respectively. However, the electric hysteresis, i.e., the gap between the electric fields for the AFE-FE and FE-AFE phase transition, is also large, which arises from the structure and switching behavior of domains. As shown in Fig. 3b, large-size domains could be observed in the bright-field TEM (BF-TEM) micrographs. Also, as observed in the HAADF-STEM images (Fig. 3d–f), the domain size (circled with white lines) of S2 is larger than those of S1 and S3, since the vector angles of S2 are distributed more closely to a narrower range, while the orientation of the vectors in S1 and S3 are more random (Fig. 3j–l). As a result, large area domains that consist of ion displacement vectors aligning along the same direction could be observed in S2 (Fig. 3e). It is believed that switching large domains consumes more energy compared with that for small-domain switching, leading to the larger polarization hysteresis of S2. Besides a high breakdown strength exceeding 800 kV cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S9), S3 MLCC derives a linear-like double P-E loop from the highly diffused AFE-PE phase transition with the A-B sites substitution doping (Pb2+ and Zr4+ ions of the perovskite lattices are replaced by Ca2+ and Sn4+ ions, respectively)43,44, while the polarization of which is inferior (~46 μC cm−2). The low hysteresis and polarization of S3 are owing to its low degree of ion displacement vector (ultra-small domains, ~2 nm) and small ion deviation displacement, as indicated by the findings of the HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 3f, i, l). It is noted that the domain morphology and ion displacement of S1–S3 in S4 are identical to those observed in S1–S3 MLCCs (Fig. 3), demonstrating that S1–S3 in S4 MLCC laminated with the periodically heterogeneous layer structure have the same lattice and domain microstructures to those in their corresponding S1–S3 MLCCs with a homogeneous layer structure (Supplementary Fig. S13). The polarization behavior of S1–S3 is further analyzed via the piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) measurement. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S14, applied with positive and negative voltages (±15 V) in the middle and the two sides of the sample surfaces, respectively, it can be seen that the domains of S2 can be aligned with the relatively low voltage, while those in S1 and S3 orientate randomly (Supplementary Fig. S14a–c). The high polarizability of S2 gives rise to the highest polarization, as revealed by the P-E loops (Fig. 2d). The domains of S1 can be aligned with an increased voltage (±25 V) (Supplementary Fig. S14d), whereas no significant difference in domain orientation is observed in S3 with the increase of voltage (Supplementary Fig. S14f) for its linear-like polarization behavior indicated by the P-E loop (Fig. 2d). It is also clear that the size of domains in S2 is larger than that of S1 and S3 (Supplementary Fig. S15). We then compared the relaxation features of the domains in S1–S3. As shown in Supplementary Figs. S14d–l and S15d–l, after withdrawing the voltage, domains in S1 and S3 get back to the original random orientation state in a period of 10 min, while those in S2 can maintain the alignment for a long time of 20 min. The results demonstrate that the domain orientation of S2 is stable after being subjected to an electric field poling process, producing the large hysteresis of the P-E loop as relatively high energy is consumed to recover the domain orientation (Fig. 2d), leading to the inferior energy storage efficiency of S2. Thus, the intuitive motivation toward high energy storage performance is to laminate and stack these three AFE ceramic layers in MLCC (S4) for the combination of their respective advantages. Interestingly, the polarization characteristic of S4 MLCC with the periodical heterogeneous structure far outstrips the expectations, e.g., applied with a high electric field of 750 kV cm−1, the polarization of S4 MLCC reaches the same high level as that of S2 MLCC and concurrently the hysteresis is even smaller than that of S1 MLCC, negating the noncompatibility of high polarization and low hysteresis loss in AFE materials.

The polarization behavior of S1–S4 MLCCs is insensitive to frequency, as signified by Supplementary Fig. S16. Moreover, the polarization and the hysteresis of S1 and S3 MLCCs change marginally as the temperature increases from −60 °C to 160 °C (Supplementary Fig. S17a, c), the trend of which is in line with their dielectric constant (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S7). Differently, with the multistage-phase transitions, the polarization of S2 MLCC decreases with the increase of temperature, especially when the temperature is higher than 120 °C (Supplementary Fig. S17b, e). It is noted that S4 MLCC maintains the high temperature stability of S1 and S3, whose polarization is almost independent of temperature in the wide range (−60 ~ 160 oC, Supplementary Fig. S17d, e). In addition, S4 MLCC shows no indication of fatigue in the long-term measurement, as evidenced by Supplementary Fig. S18 that the polarization and hysteresis remain steady after being subjected to 100,000 cycles of charge-discharge process.

Rationalization with the phase-field simulation

To shed light on the mechanisms of the stunning findings, i.e., the coexistence of high polarization and near-zero hysteresis of S4 MLCC, we performed the phase-field simulation to rationalize the impact of interlaminar strain on the domain evolution and polarization behavior in MLCCs. Figure 4a shows the z-direction (out-of-plane) strain-electric field (S-E) loops of the MLCCs measured by the electrostriction system. With an electric field of 400 kV cm−1, S2 MLCC has a significantly larger strain of 0.31% than those of S1 and S3 MLCCs (0.19% and 0.11%, respectively). The large electric field-induced strain of S2 is ascribed to its unique multiphase transition behavior (Supplementary Fig. S11) and large lattice deformation (Supplementary Fig. S19 and Tables S3 and S4) induced by the electric field. The volume of AFEs changes with an applied electric field, and the out-of-plane strain along the z-axis direction is typically accompanied by the transverse displacement along the x-axis direction45,46,47. Thus, the different out-of-plane strains generate various in-plane strains among S1–S3 when the dielectric layers are periodically stacked as S4 (Supplementary Figs. S20–S24 and Supplementary Note S3). As revealed by the in-situ Raman spectroscopy of S4 (Supplementary Fig. S25), the applied electric field shifts the Raman scattering peaks of S1 and S3 in S4 from 68.2 cm−1 and 67.8 cm−1 towards the low wavenumber, e.g., 67.3 cm−1 and 66.0 cm−1, respectively, while moves the peak of S2 toward the opposite direction, e.g., from 64.3 cm−1 to 67.0 cm−1. The results indicate that the interlaminar strain created by the periodical lamination structure design distorts the lattices of S2 and shortens their interatomic distance. In contrast, the strain prolongs the interatomic distance of S1 and S3. Furthermore, as the amplitude of the wavenumber shift of S2 is more pronounced than that of S1 and S3, it is suggested that the interlaminar strain generates larger lattice distortion in S2 [ref. 48]. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 4b, the S2 layer thus is subjected to an in-plane tensile strain while the neighboring S1 and S3 layers have compressive strains in S4 MLCC. It is noted that the influence of electrodes on the strain of the ceramic layers is limited (Supplementary Notes S3 and S4 and Figs. S28 and S29). The strain can affect the hysteresis and polarization behavior of AFE ceramics (Supplementary Note S5 and Table S6)49,50,51.

a Strain-electric field (S-E) loops of the AFE MLCCs (out-of-plane direction). b Schematic of interlaminar strain at the dielectric layer interfaces induced by the electrostriction effect. c, d Phase-field simulated dipole orientation and domain structure in the dielectric layers without and with the interlaminar strain (E = 400 kV cm−1). e Pz distribution (dashed boxes of Fig. 4c, d) across the out-of-plane direction of each dielectric layer. For simplicity, Pz values are fitted with a high-order polynomial. f Three-dimensional free energy density surface diagram under zero strain, in-plane tensile strain, and in-plane compressive strain.

We leverage the phase-field simulation to illustrate how the strains optimize the polarization behavior of S4 MLCC with a control group that assumes noninteraction exists between the ceramic layers for comparisons (Fig. 4c–e). With the confinement (in-plane tensile strain) under ~400 kV cm−1, the compliance of dipoles of S2 with the electric field is decreased as compared to that without constraint, as revealed by the simulated domain structures. As shown in the case of S2 without strain confinement (S2 of Fig. 4c), large single domains in which the dipoles highly orientate along the out-of-plane direction can be induced by the applied electric field, whereas the tensile strain caused by the layer interaction makes the dipoles in S2 tend to lie in-plane, forming small domains (S2 of Fig. 4d). The three-dimensional Landau free energy density surface points out that the in-plane tensile strain shifts the free energy minima points from 12 values to 4 in-plane values (Fig. 4f), which pushes the out-of-plane polarization in S2 to a high-energy state, impeding dipoles to be aligned with the applied electric fields52. The decrease in domain size imparts S2 low hysteresis to reduce the energy consumption for domain switching. The strain-engineered domain also scarifies the polarizability of S2. Figure 4e shows the continuously varying Pz components across the out-of-plane direction of each dielectric layer. With the in-plane tensile strain, the Pz of S2 is depressed. Intriguingly, in contrast to the tensile strain, the in-plane compressive strain repels the dipoles of S1 and S3 to be orientated with the applied field, yielding increased Pz (Fig. 4e) that could make up for the impairment of polarization in S2. Moreover, the domains in S1 and S3 are small, as exhibited in Fig. 3d, f, and it is believed that the in-plane compressive strain has limited impact on the domain size of S1 and S3 when applied with a high electric field (Fig. 4d), allowing S1 and S3 to retain their minimal hysteresis. As rationalized by the phase-field simulation, S4 exhibits giant polarization and near-zero hysteresis simultaneously via the interlaminar strain engineering design.

The energy storage feature of the MLCCs

The energy storage density, loss and efficiency of the samples were evaluated by integrating the area between the polarization axis and the P-E loops applied with their corresponding breakdown strength fields. As shown in Fig. 5a, due to the high polarization, S2 MLCC shows a high recoverable energy density of 18.9 J cm−3 with a relatively low electric field of 480 kV cm−1, even surpassing those of S1 and S3 with higher electric fields of 610 kV cm−1 and 810 kV cm−1, respectively. However, the large electric hysteresis of S2 generates a high energy loss of 3.7 J cm−3, yielding a poor energy efficiency of 83.6%. The large energy loss may convert into heat during the high-speed charge-discharge process and lead to a serious overheating problem, damaging the MLCCs themselves and the surrounding circuits and components. On the contrary, S1 MLCC possesses a relatively high energy efficiency of 92.5%, which is attributable to the low hysteresis reflected by its slim P-E loop, whereas the low polarization limits the energy storage density, which is only 60% of that of S2 MLCC. Also because of the low polarization, even stimulated with a high electric field of 810 kV cm−1, the recoverable energy density of S3 MLCC only reaches 15.4 J cm−3 with an undesirable energy efficiency of 84.6%. Figure 5a, b shows the comparison of the recoverable energy density and energy efficiency of S1-S4 MLCCs under electric fields up to their corresponding breakdown strength. The marvelous energy storage performance is attained in S4 MLCC due to their unique polarization behavior tuned via the interlaminar strain, as rationalized by the phase-field theory. By decoupling the mutual restriction between high polarization and low electric hysteresis, S4 MLCC shows a colossal recoverable energy density of 22.0 J cm−3 with an ultrahigh energy efficiency of 96.1% simultaneously under an electric field of 750 kV cm−1. As summarized in Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. S30, and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8, the recoverable energy density and the energy efficiency are the highest compared with those achieved in reported MLCCs, and the recoverable energy density is more than 5 times that of the second-best value obtained previously with an energy efficiency beyond 95%. It is noted that both the recoverable energy density and the energy efficiency of S4 MLCC transcend those of MLCCs with a single component, for example, the recoverable energy density is 20% higher than that of S2 MLCC and the energy efficiency is 104% that of S1 MLCC (Fig. 5b), further confirming the significance of strain engineering between the S1, S2 and S3 layers in S4 MLCC.

a Recoverable energy density and energy efficiency of S1-S4 MLCCs as a function of the electric field. b Comparisons of recoverable energy density and energy efficiency of S1-S4 MLCCs with electric fields at their corresponding breakdown strength. c Comparison of the energy storage performance of our MLCC with strain engineering (S4) with those of representative MLCCs. Detailed information for the MLCCs is listed in Supplementary Table S8. d Frequency stability, e temperature stability, and f cycling stability of recoverable energy density and energy efficiency of S1-S4 MLCCs.

The high frequency, temperature, and cycling stabilities of polarization behavior endow S4 MLCC with stable energy storage performance. As shown in Fig. 5d, the variation range of the recoverable energy density and energy efficiency with different frequencies is less than ±3%. Moreover, the recoverable energy density and energy efficiency change less than ±13% in the temperature range between −60 °C and 160 °C (Fig. 5e), meeting the X8R industrial standard for MLCCs (the performance changing within ±15% over a temperature range of −55 °C to 150 °C). Also, S1-S4 MLCCs display excellent energy storage cycling stability over 100,000 high-field charge-discharge cycles, as shown in Fig. 5f, as the polarization behavior (P-E loops, Supplementary Fig. S18) of the samples changes marginally in the cycling measurement.

Charge/discharge capability to meet practical applications

The charge-discharge measurement with a resistance-capacitance (RC) circuit was carried out to evaluate the practicability of the energy storage and release features of the MLCCs36. The electric field-dependent overdamped discharge current density (CD) curves of S1-S4 MLCCs at room temperature are exhibited in Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. S31. The stored energy of the samples can be discharged within a short period of ~20 μs, validating their fast discharge capability for high/pulsed power electronics. The discharge energy density (Wdis) of the samples increases nonlinearly with the increase of electric fields, which shows the same trend as that evaluated by the P-E loops. As shown in Fig. 6b, S4 MLCC possesses a high discharge capability with a Wdis of ~19.2 J cm−3, which agrees well with the value derived from the P-E loop with the same applied electric field of 750 kV cm−1. Again, the variation of the discharge energy density of S4 MLCC tested by the charge-discharge measurement is within ±15% in the wide temperature span ranging from −60 °C to 160 °C (Fig. 6c, d and Supplementary Fig. S32), double confirming the high temperature stability of our design. In addition, since no obvious changes in the current density-time curves are observed when S4 is subjected to the cycling charge-discharge process, the decay of discharge energy density is lower than 1% (Supplementary Fig. S33).

Discussion

In summary, we propose a strain engineering strategy capitalizing on the electrostrictive effect of AFE ceramics to modulate the domain structure and manipulate the polarization behavior of the dielectric mediums of MLCCs. With the design of the heterogeneous layer structure, the in-plane tensile strain that impedes domain growth and compressive strain that spurs dipoles to be aligned with the fields can distribute precisely to the corresponding dielectric layers, decoupling the inherent conflicts between high polarization and low electric hysteresis. As a result, unrivaled energy storage characteristic, i.e., a colossal recoverable energy density of 22.0 J cm−3, the highest value in MLCCs with an efficiency surpassing 95% (96.1% of our specimen), is achieved in our design. Combined with the high temperature and frequency stabilities and the remarkable antifatigue property, this work defines clear interlaminar strain engineering guidelines for MLCCs to pursue supreme overall energy storage performance. Moreover, we would like to raise the awareness that ultrahigh energy efficiency is the essential prerequisite for MLCCs to be applied as energy storage components for power electronics.

Methods

Fabrication of the MLCCs

(Pb0.9Ba0.04La0.04)(Zr0.65Sn0.3Ti0.05)O3 (PBLZST), (Pb0.95Ba0.02La0.02)(Zr0.6Sn0.4)O3 (PBLZS), and (Pb0.92Ca0.06La0.02)(Zr0.6Sn0.4)0.995O3 (PCLZS) ceramic powders were prepared by the solid-state reaction method. High-purity PbO (≥99%), La2O3 (≥99.99%), ZrO2 (≥99%), SnO2 (≥99.5%), TiO2 (≥99%), BaCO3 (≥99.77%) and CaCO3 (≥99%) (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., China) were used as the starting materials, and excessive PbO (6 wt.%) was added to compensate the volatilization of lead during the sintering process. The stoichiometric powders were planetary ball-milled with alcohol for 6 h and dried at 100 °C for 3 h and then calcined at 850 °C for 3 h to form the perovskite phase. The calcined bulks were crushed and ball-milled for 6 h again. Subsequently, the as-synthesized powders were refined and dispersed evenly by the sanding method.

The MLCCs were prepared by the tape-casting method. The ceramic powders were ball-milled with the solvent (ethanol and xylene), dispersant (phosphate ester and fish oil), and defoamer (silicone oil) for 8 h. And then, binder (polyvinyl butyral) and plasticizer (dibutyl phthalate) were added to the mixture and ball-milled again for another 10 h. The prepared slurries were cast on a film-belt substrate with a tape-casting machine to produce uniform green tapes with a thickness of ~15 μm. The green tapes were screen-printed with 70Ag-30 Pd paste as internal electrodes and stacked layer by layer with a hot-pressed process (2 MPa at 70 °C). Especially, S4 consisted of a periodical layered structure that S2 layer was sandwiched with S1 and S3 layers. The stacked samples were cut to square with a dimension of 5 mm × 5 mm. The MLCCs were heated at 600 °C for 2 h to burn all the organic additives out and then sintered at 1120 ~ 1150 °C for 5 h. Finally, silver pastes were used as termination electrodes for electrical measurement.

Characterizations

The microstructure of the MLCCs was observed by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, GeminiSEM300, Carl Zeiss, Germany) in combination with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The average grain size and grain distribution were analyzed by the software NanoMeasurer. The crystal structures were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD, 7000S/L, Shimadzu Corp., Japan) with Cu Kα radiation. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) specimens were prepared by a dual-beam Focused Ion Beam (FIB, Helios 5 UC, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The target cutting areas in ceramics were first coated with tungsten protection layers with a thickness of 2 μm, and then the surrounding regions were removed by accelerated Ga ions. The specimens were extracted using a Tungsten micromanipulator and subsequently attached to commercial copper grids. For the initial lamella preparation, Ga ion acceleration was set to 30 kV and the beam current to 2.5 nA. These values were then gradually reduced to achieve precise thinning down. To remove the ion-damaged surface layers, a voltage of 2 kV and a current of 9 pA were applied. The TEM lamellae were thinned to a final range of approximately 30 ~ 40 nm in thickness. TEM bright field images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of TEM lamellas were obtained by a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Talos F200X, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) operated at 200 kV. The atomic-scale structures and chemical compositions were investigated by a double spherical aberration (Cs) corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM, Spectra 300, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) equipped with probe and image correctors and operated at 300 kV. The probe convergence angle and high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) acceptance angles were 25 mrad and 39 ~ 200 mrad, respectively. The atomic-scale elemental analysis was performed using an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) detector attached in the Cs-corrected TEM, and quantification was automatically carried out in ThermoFisher Velox software. Piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) measurement was conducted by atomic force microscopy (CYPHER, Oxford Instruments, England) to evaluate the domain switching behavior under different voltages and relaxation times. In-situ XRD was measured at room temperature by using the D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The adhesion strength between the electrodes and ceramic layers was measured using a universal test machine (XLW (PC)-500N, Sumspring Experimental Instruments Co. Ltd, China). The Young’s moduli were obtained by a universal test machine (E45.105, MTS Systems Corporation, USA). The specific heat capacities were obtained by a differential scanning calorimeter (Diamond DSC, PerkinElmer Instruments, USA). The thermal expansion measurements were carried out using a thermal dilatometer (DIL, Netzsch DIL 402 Expedis Supreme, Germany). In-situ Raman spectra measurement was performed with a laser confocal Raman microspectroscope (LabRAM HR800, Horiba Jobin Yvon, France. Laser wavelength: 520 nm. Wave number range: 50 cm−1 to 1000 cm−1). The MLCCs were sectioned along the red dash line, as schematically shown in Supplementary Fig. S26a. The transverse sections were then ground and polished for analysis. In the Raman measurement, a laser spot with a diameter of 1 μm was focused on the dielectric layer of the exposed transverse section of the MLCC connected to a high-voltage power supply (MS2671AN, Nanjing Minsheng Electronic Instrument Co., Ltd, China), as shown in Supplementary Fig. S26b, c.

Temperature-dependent and frequency-dependent dielectric properties were measured by a dielectric property test system (DPTS-RT-600, Wuhan Yanhe Technology Co., Ltd., China) connected with a high-precision LCR meter (6630, Microtest Corp., China). The electrical resistivity was evaluated via a high resistance meter (6571B Electrometer, Keithley Instruments, Inc., USA). The strain-electric field (S-E) curves were measured by aix ACCT TF 2000 analyzer FE measurement system (aix ACCT Co., Aachen, Germany). The polarization-electric field (P-E) hysteresis loops were tested by a precision ferroelectric analyzer (PK-CPE 1701, PolyK Technologies, USA). The charge/discharge properties were characterized by a PK-capacitor discharge test system (CPR1601-D612, PolyK Technologies, USA). A variable temperature comprehensive test platform (VTMP400, Wuhan Yanhe Technology Co., Ltd., China) was employed to control the sample temperature during the measurements.

Phase-field simulations

PbZrO3-based material is taken as an example by solving the time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau (TDGL) equation for the temporal evolution of the polarization vector field:

where \({P}_{i}\left(r,t\right)\) is polarization, L is the kinetic coefficient, and F is the total free energy of the system, which is expressed as:

where V is the system volume. The Landau free energy density fLand can be calculated by:

where P1, P2, P3 are polarization components. α1, α11, α12, α111, α112 and α123 are Landau coefficients. The elastic energy density can be expressed as:

where Cijkl is the elastic stiffness tensor, \({\varepsilon }_{{ij}}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{{ij}}^{0}\) are the total local strain, and the spontaneous strain, respectively53. The gradient energy density can be expressed as:

where i = 1, 2, 3. λ0 is a negative constant, which favors the stability of the AFE phase. g0 is a positive constant, which drives the phase transition from AFE to FE. In this work, both λ0 and g0 have been normalized to eliminate dimension influence (λ = −3.0, g = 0.25, 0.20, and 0.23, respectively). The electrostatic energy density felec is given by:

where E appl is the applied electric field, E in is the internal electric field, including the dipole-dipole interaction field, and the local electric field caused by the random point defects. In the model, randomly distributed points comprising 1% ~ 5% of the total are classified as defect dipoles and are applied to these points27. The equation was solved by a semi-implicit Fourier spectral method and the simulation size is 64 Δx × 64 Δy × 14 Δz (Δx is the number of grid points and equals 0.5 nm in this work). We use Landau coefficients of the Pb(Zr1−xTix)O3 (x ≤ 0.1) system modified for the calculation54,55. α1 = − 5.54 × 107 J m C−2, α11 = 5.60 × 108 J m5 C−4, α12 = 2.89 × 108 J m5 C−4, α111 = 1.65 × 109 J m9 C−6, α112 = − 8.66 × 108 J m9 C−6, α123 = 3.19 × 1010 J m9 C−6, c11 = 15.6 × 1010 N m−2, c12 = 9.6 × 1010 N m−2, c44 = 12.7 × 1010 N m−2, Q11 = 0.048 m4 C−2, Q12 = − 0.015 m4 C−2, Q44 = 0.047 m4 C−2.

Thermodynamic methods

To demonstrate the effect of interlayer-interactions on the free energy of AFE MLCC, we performed a three-dimensional free energy surface plotting of the Landau free energy. The thermodynamic free energy density (ΔGpolar) is as follows56,

where σi (i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) are the stress, λeff and τeff represent the high-order electromechanical term. μ1 is the linear thermal expansion coefficient.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting this study and its findings are available within this paper and its Supplementary Information. The data corresponding to this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Pan, H. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage in superparaelectric relaxor ferroelectrics. Science 374, 100–104 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Flexible high-temperature dielectric materials from polymer nanocomposites. Nature 523, 576–579 (2015).

Pan, H. et al. Ultrahigh-energy density lead-free dielectric films via polymorphic nanodomain design. Science 365, 578–582 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Mobile energy storage technologies for boosting carbon neutrality. Innovation 4, 100518 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Outstanding energy storage performance in high‐hardness (Bi0.5K0.5)TiO3‐based lead‐free relaxors via multi‐scale synergistic design. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110478 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Electroceramics for high-energy density capacitors: current status and future perspectives. Chem. Rev. 121, 6124–6172 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Regulating local electric field to optimize the energy storage performance of antiferroelectric ceramics via a composite strategy. J. Adv. Ceram. 12, 598–611 (2023).

Shi, P. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage density and efficiency in A/B-site co-modified silver niobate relaxor antiferroelectric ceramics. J. Materiomics 11, 100869 (2025).

Pan, Z. et al. Fatigue‐free aurivillius phase ferroelectric thin films with ultrahigh energy storage performance. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001536 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. Superior energy density through tailored dopant strategies in multilayer ceramic capacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 2938–2948 (2020).

Gerson, R. & Marshall, T. C. Dielectric breakdown of porous ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 30, 1650–1653 (1959).

Zhao, P. et al. Ultra-high energy storage performance in lead-free multilayer ceramic capacitors via a multiscale optimization strategy. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 4882–4890 (2020).

Feng, M. et al. Recent advances in multilayer-structure dielectrics for energy storage application. Adv. Sci. 8, e2102221 (2021).

Zhao, P. et al. High‐performance relaxor ferroelectric materials for energy storage applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1803048 (2019).

Lee, C.-H. & Yoon, J.-R. Finite element analysis of multi-layer ceramic capacitors improved self-heating for high reliability. Trans. Electr. Electro. Mater. 22, 424–431 (2021).

Luo, N. et al. Constructing phase boundary in AgNbO3 antiferroelectrics: pathway simultaneously achieving high energy density and efficiency. Nat. Commun. 11, 4824 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Giant energy-storage density with ultrahigh efficiency in lead-free relaxors via high-entropy design. Nat. Commun. 13, 3089 (2022).

Yan, F. et al. Significantly enhanced energy storage density and efficiency of BNT-based perovskite ceramics via A-site defect engineering. Energy Storage Mater. 30, 392–400 (2020).

Li, D. et al. Progress and perspectives in dielectric energy storage ceramics. J. Adv. Ceram. 10, 675–703 (2021).

Correia, T., Stewart, M., Ellmore, A. & Albertsen, K. Lead‐free ceramics with high energy density and reduced losses for high temperature applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 19, 1700019 (2017).

Zheng, J., Takahashi, S., Yoshikawa, S., Uchino, K. & de Vries, J. W. C. Heat generation in multilayer piezoelectric actuators. J. Am. CerAm. Soc. 79, 3193–3198 (2005).

Levesque, L. Law of cooling, heat conduction and Stefan-Boltzmann radiation laws fitted to experimental data for bones irradiated by CO2 laser. Biomed Opt. Express 5, 701–712 (2014).

Palneedi, H., Peddigari, M., Hwang, G. T., Jeong, D. Y. & Ryu, J. High‐performance dielectric ceramic films for energy storage capacitors: progress and outlook. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1803665 (2018).

Zhu, L. F. et al. Heterovalent-doping-enabled atom-displacement fluctuation leads to ultrahigh energy-storage density in AgNbO3-based multilayer capacitors. Nat. Commun. 14, 1166 (2023).

Xiao, W. et al. Free energy regulation and domain engineering of BaTiO3-NaNbO3 ceramics for superior dielectric energy storage performance. Chem. Eng. J. 461, 142070 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Bimodal polymorphic nanodomains in ferroelectric films for giant energy storage. Energy Storage Mater. 48, 306–313 (2022).

Shi, X., Wang, J., Xu, J., Cheng, X. & Huang, H. Quantitative investigation of polar nanoregion size effects in relaxor ferroelectrics. Acta Mater. 237, 118147 (2022).

Li, Y., Lin, W., Yang, B., Zhang, S. & Zhao, S. Domain dynamics engineering in ergodic relaxor ferroelectrics for dielectric energy storage. Acta Mater. 255, 119071 (2023).

Dong, X. et al. Realizing enhanced energy storage and hardness performances in 0.90NaNbO3-0.10Bi(Zn0.5Sn0.5)O3 ceramics. J. Adv. Ceram. 11, 729–741 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage in high-entropy ceramic capacitors with polymorphic relaxor phase. Science 384, 185–189 (2024).

Gong, X. et al. Enhancing energy storage efficiency in lead-free dielectric ceramics through relaxor and lattice strain engineering. J. Materiomics 10, 1196–1205 (2024).

Nong, P. et al. Simultaneous enhancement of energy storage performance and thermal stability of NaNbO3-based ceramics via multi-scale modulation. J. Materiomics 10, 670–681 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Near-zero energy consumption capacitors by controlling inhomogeneous polarization configuration. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313285 (2024).

Gaur, A. P. S. et al. Antiferroelectric ceramics for energy-efficient capacitors by theory-guided discovery. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312856 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Interfacial polarization engineering enables superior energy storage performance in (Pb,La)(Zr,Sn,Ti)O3-based antiferroelectric ceramics. Ceram. Int. 50, 38314–38322 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Grain-orientation-engineered multilayer ceramic capacitors for energy storage applications. Nat. Mater. 19, 999–1005 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Superior energy storage performance in antiferroelectric multilayer ceramics via heterogeneous interface structure engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 451, 138636 (2023).

Ge, G. et al. Synergistic optimization of antiferroelectric ceramics with superior energy storage properties via phase structure engineering. Energy Storage Mater. 35, 114–121 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Meng, X. & Hao, X. Synergistically achieving ultrahigh energy-storage density and efficiency in linear-like lead-based multilayer ceramic capacitor. Scripta Mater. 195, 113723 (2021).

Wang, H., Liu, Y., Yang, T. & Zhang, S. Ultrahigh energy-storage density in antiferroelectric ceramics with field‐induced multiphase transitions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1807321 (2019).

Cai, H. et al. Significantly improved energy storage properties and cycling stability in La-doped PbZrO3 antiferroelectric thin films by chemical pressure tailoring. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 39, 4761–4769 (2019).

Ge, P.-Z. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage density and superior discharge power density in a novel antiferroelectric lead hafnate. Mater. Today Phys. 24, 100681 (2022).

Liu, X., Li, Y., Sun, N. & Hao, X. High energy-storage performance of PLZS antiferroelectric multilayer ceramic capacitors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 7, 756–764 (2020).

Li, Y. Z., Wang, Z. J., Bai, Y. & Zhang, Z. D. High energy storage performance in Ca-doped PbZrO3 antiferroelectric films. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40, 1285–1292 (2020).

Kittel, C. Theory of antiferroelectric crystals. Phys. Rev. 82, 729–732 (1951).

Tan, X. et al. Auxetic behavior under electrical loads in an induced ferroelectric phase. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 042909 (2009).

Jo, H. R. & Lynch, C. S. A high energy density relaxor antiferroelectric pulsed capacitor dielectric. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 024104 (2016).

Ding, M., He, X., Cheng, X., Zhang, Y. & Yang, F. An in-situ Raman spectroscopic investigation of PLZT ceramic under a coupled mechanical-electrical load. J. Electroceram. 46, 162–171 (2021).

Tan, X. et al. Electric-field-induced antiferroelectric to ferroelectric phase transition in mechanically confined Pb0.99Nb0.02[(Zr0.57Sn0.43)0.94Ti0.06]0.98O3. Phys. Rev. B 81, 014103 (2010).

Peláiz-Barranco, A. & Hall, D. A. Influence of composition and pressure on the electric field-induced antiferroelectric to ferroelectric phase transformation in lanthanum modified lead zirconate titanate ceramics. Ieee T. Ultrason. Ferr. 56, 1785–1791 (2009).

Xu, Y. et al. Effect of Ba content on the stress sensitivity of the antiferroelectric to ferroelectric phase transition in (Pb,La,Ba,)(Zr,Sn,Ti)O3 ceramics. J. Am. CerAm. Soc. 97, 206–212 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. Polarization-switching pathway determined electrical transport behaviors in rhombohedral BiFeO3 thin films. Nanoscale 13, 17746–17753 (2021).

Guo, C., Dong, S., Wang, J., Wang, X. & Huang, H. Strain‐induced toroidal polar states in wrinkled ferroelectric polymer by phase‐field simulations. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2300193 (2023).

Xu, K., Shi, X., Dong, S., Wang, J. & Huang, H. Antiferroelectric phase diagram enhancing energy-storage performance by phase-field simulations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 14, 25770–25780 (2022).

Liu, Z. & Xu, B.-X. Insight into perovskite antiferroelectric phases: Landau theory and phase field study. Scripta Mater. 186, 136–141 (2020).

Gao, R., Shi, X., Wang, J., Zhang, G. & Huang, H. Designed giant room‐temperature electrocaloric effects in metal‐free organic perovskite [MDABCO](NH4)I3 by phase-field simulations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2104393 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52272110, 52372108, 52172114, 52001117, 52372100 and 62105110) (S.J., G.Z., H.H, K.L., and J.G.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1204603) (G.Z., and K.L.) and the fellowship award from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (PolyU PDFS2223-5S08) (X.H.). We also would like to thank the Analytical and Testing Center of HUST.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. conceived the idea. G.Z., H.H., S.J., J.G. and K.L. supervised the project. Y.Y., G.Z., H.H., J.G. and X.H. designed the experiments. Y.Y. and Z.D fabricated the samples. Y.Y. performed the characterizations with the assistance of Y.L. and C.W. K.X. and H.H. carried out the phase-field simulation. B.Y., Z.Z. and J.G. performed the TEM measurement. G.G. and J.Z. performed the in-situ XRD measurement. G.L. and N.L. conducted the XRD refinement. G.L., N.L. and J.W. (Hebei University) tested the in-situ Raman spectra. Y.F. and J.W. (Beijing Institute of Technology) carried out the PFM analysis. H.Y. and Y.Z. conducted the finite element simulation. G.Z. Y.Y. and K.L. prepared and revised the manuscript, with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Raj Wali Khan, Abdul Manan and Lovro Fulanović for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Xu, K., Yang, B. et al. Giant energy storage density with ultrahigh efficiency in multilayer ceramic capacitors via interlaminar strain engineering. Nat Commun 16, 1300 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56605-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56605-3

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced energy-storage in lead-free multilayer capacitors via entropy-assisted polymorphic domain engineering

Nature Communications (2025)