Abstract

Fatigue is one of the most common persistent symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. We aimed to assess fatigue during and after a SARS-CoV-2 infection by age, sex, presence of a medical risk condition, SARS-CoV-2 variant and vaccination status, accounting for pre-infection fatigue and compared with uninfected individuals. We used data from an ongoing prospective cohort study in the Netherlands (VASCO). We included 22,705 first infections reported between 12 July 2021 and 9 March 2024. Mean fatigue scores increased during infection, declined rapidly in the first 90 days post-infection, but remained elevated until at least 270 days for Delta and 120 days for Omicron infections. Prevalence of severe fatigue was 18.5% before first infection. It increased to 24.4% and 22.5% during acute infection and decreased to 21.2% and 18.9% at 90 days after Delta and Omicron infection, respectively. The prevalence among uninfected participants was lower than among matched Delta-infected participants during the acute phase of the infection and 90 days post-infection. For matched Omicron-infected individuals this was only observed during the acute phase. We observed no differences in mean post- vs pre-infection fatigue scores at 90-270 days post-infection by vaccination status. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the prevalence of severe fatigue was modest at population level, especially for Omicron.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of individuals recover from an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection within a couple of weeks but some experience persisting symptoms1,2. The World Health Organization uses the term Post-COVID condition (PCC) when symptoms have persisted for at least 90 days1. Fatigue is reported by a third to half of individuals with COVID-19 as one of the symptoms that they experienced during the acute phase of the infection2,3. It is also often one of the symptoms that lingers after the acute phase2, and is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms of PCC3,4,5. Reported PCC prevalences vary widely depending on the PCC definition and symptom assessment methods employed, populations studied, timing of assessments, among other factors4.

Older persons, females, and persons with pre-existing comorbidities have been reported to have a higher risk of persisting fatigue after a SARS-CoV-2 infection5,6,7. COVID-19 disease severity5,7,8,9, SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern10,11 and repeat infections11,12 have been associated with post-infection fatigue and with PCC too, but results are uncertain and/or inconsistent across studies6,13,14,15,16. Furthermore, whereas research has shown that COVID-19 vaccination has provided protection against severe disease and mortality, and to a lesser extent against infection17,18, its protective effect against post-infection fatigue and PCC, has not been conclusively established. Meta-analyzes suggest a protective effect of vaccination19,20,21, but the included studies are of variable quality and substantially heterogeneous in study designs, study populations and measured outcomes22.

Estimating the frequency and severity of, and risk factors for, persisting fatigue after a SARS-CoV-2 infection is challenging22,23. Studies are often cross-sectional in nature and only assess participants after SARS-CoV-2 infection, while fatigue might have already been present before the infection. Fatigue is common in the general population24 and might be affected by seasonal effects. In addition, COVID-19 related restrictions during the pandemic may have affected fatigue levels, also in individuals who never had COVID-19. Therefore, detailed information about fatigue before and after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and in uninfected individuals, is essential to provide better insight into the independent effect of a SARS-CoV-2 infection on persistent fatigue.

In this prospective cohort study, we assessed fatigue during and after a SARS-CoV-2 infection by age, sex, presence of a medical risk condition, SARS-CoV-2 variant and vaccination status, taking into account pre-infection fatigue scores alongside fatigue over time in matched uninfected individuals.

Results

Study population

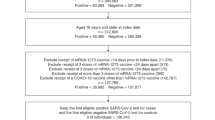

A total of 22,705 first infections between 12 July 2021 and 9 March 2024 with available pre- and post-infection scores on the fatigue severity subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength or CIS-fatigue scores were reported (Table 1). Most first infections (21,642, 95%) were attributed to the Omicron variant. For these first infections, 25,246 pre-infection and 63,497 post-infection fatigue scores were available (Supplementary file, Figure S1). Most participants had been booster vaccinated at the time of infection (20,307, 89%). Additionally, 6414 repeat Omicron infections with available pre-infection and post-infection CIS-fatigue scores were reported of which the majority concerned a second infection (5488, 86%) and were classified as post-Omicron BA.5 (6,120, 95%). Participants reporting a repeat infection, compared to a first infection, were more often below 60 years (55% vs 48%). During the period in which bivalent booster vaccinations were available, 7,959 infections with pre- and post-infection fatigue scores were available. The participants reporting these infections often (4816; 61%) had received a bivalent booster vaccination before infection. In total, 2,331 (10%) first infections, 988 (15%) repeat infections, and 1141 (14%) infections during the bivalent vaccination period were excluded from post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue score analyzes because only one pre-infection score was available which was 0-14 days before the infection.

Fatigue among infected participants

First infections: pre-infection fatigue score

Overall unadjusted mean fatigue scores were visualized in Supplementary file, Figure S2. The proportion of participants reporting the maximum CIS-fatigue score was small ( < 2%; Supplementary file, Table S1). Adjusted mean pre-infection fatigue scores differed between subgroups (Supplementary file, Figure S3) with significantly (t-test p < 0.001) higher means for females vs males (23.5 (95%CI 23.1–23.9) vs 20.9 (20.4–21.3)), 18–59 year-olds (24.3 (23.9–24.7) vs 60–85 years-old at 20.0 (19.6–20.4)) and those with vs without a medical risk condition (24.5 (24.0–25.0) vs 19.8 (19.4–20.2)). Mean pre-infection scores also differed significantly (p < 0.001) between unvaccinated participants (20.8; 20.2–21.5), primary vaccinated participants (23.4; 23.0–23.8) and booster vaccinated participants (22.3; 21.9–22.7). Mean pre-infection scores did not differ significantly by variant of infection with means of 22.0 (21.3–22.6) for Delta infections and 22.4 (22.0–22.7) for Omicron infections (p = 0.246).

First infections: post- vs pre-infection fatigue

The proportion of participants with ≥ 6 points increase in CIS-fatigue scores compared to pre-infection was largest in the first 30 days post-infection (Supplementary file, Figure S4A). For Omicron infections the proportions of participants with ≥ 6 points increase or decrease in CIS-fatigue scores compared to pre-infection were similar from about 120 days post-infection (about 20%). Unadjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores per 10-day time intervals since the infection showed a large increase during the acute phase of the infection followed by a steep decline in the first 90 days, and approaching zero (thus pre-infection levels) after 150 days for Omicron infections and 270 days for Delta infections (Supplementary file, Figure S5). Adjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores showed a similar pattern (Fig. 1). Peak means of up to 8 points during acute infection were observed, with higher peak means (p < 0.001) for 60-85 year-olds, those without a medical risk condition, and for Delta infections (Supplementary file, Table S2). Also, unvaccinated participants had a higher peak mean compared to primary vaccinated (p = 0.008) and booster vaccinated (p = 0.008) participants. Adjusted means showed a steep decline in the first 90 days and were non-significantly different from zero after 120 days for Omicron infections and declined towards near zero but remained significantly elevated up to 270 days for Delta infections. Means were 2.5 (1.8–3.2), 1.6 (1.0–2.2) and 1.5 (0.7–2.3) at 90, 180 and 270 days after Delta infection and 0.5 (0.1–1.0), 0.1 (−0.4–0.5) and 0.4 (−0.1–0.9) after Omicron infection, which differed significantly at 90 (p < 0.001), 180 days ((p < 0.001) and 270 days (p = 0.003) (Table 2). At 90, 180 and 270 days post-infection, no significant differences in mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores were present by age group or vaccination status. In females, means were higher than in males at 90 (p = 0.004) and 180 days post-infection (p = 0.049), but differences were small (0.6 (95%CI 0.2–1.0) and 0.4 (0.0–0.8), respectively).

Each panel visualizes the adjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores with 95% CI over time since infection and colored by covariable level. Results are adjusted for the other shown covariables and time since infection is included as penalized spline. CIS = Checklist Individual Strength; CI = Confidence Interval.

When limiting the analysis to Omicron infections, adjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores during the acute phase of the infection were lowest for Omicron BA.1/BA.2 infections (3.2; 2.7–3.7), followed by Omicron BA.5 infections (5.2; 4.4–5.9) and highest for post-Omicron BA.5 infections (7.1; 6.3–8.0) (p < 0.001). Means were significantly higher for Omicron BA.5 infections (0.6; 0.2–1.1) than Omicron BA.1/BA.2 (p = 0.001) and post-Omicron BA.5 (p = 0.030) at 180 days post-infection but the differences were small (Supplementary file, Figure S6). Among Omicron infections, means of 60–85-year-olds were significantly higher at 90 (p = 0.001) and 180 days (p = 0.016) compared to 18–59-year-olds, but differences were small (0.3 and 0.2, respectively). Differences in means at 90 to 270 days post-infection by other covariables were comparable to the analysis that also included Delta infections.

First infections: prevalence of severe fatigue

The estimated adjusted prevalence of severe fatigue at 30 days before a Delta infection was 18.5% (16.5–20.7) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). This increased to 24.4% (22.1–27.0) during the acute phase of the infection, and then decreased to 21.2% (18.9–23.6) at 90 days post-infection and 18.8% (16.5–21.3) at 180 days post-infection. The prevalence at 30 days before an Omicron infection was 18.5% (17.5-19.6). This increased to 22.5% (21.4–23.6) during the acute phase of the infection and decreased to 18.9% (17.8–19.9) at 90 days and 18.6% (17.5–19.7) at 180 days post-infection. Smaller numbers lead to less precise prevalence estimates at 270 days, especially for Delta infections. Differences between Delta and Omicron were not statistically significant before infection (p = 0.987), during the acute phase of the infection (p = 0.138) or at 90 (p = 0.057), 180 (p = 0.889) or 270 days post-infection (p = 0.170).

Results of the subgroup analysis limited to symptomatic first infections (21,337, 94%) were not substantially different from results of the analysis among all first infections (Supplementary file, Figure S7). Participants with asymptomatic Delta infection (76, 7.1%) showed a mean post- vs-pre-infection CIS-fatigue score of 4 points during the acute phase of the infection and this remained at about the same level up to at least 270 days post-infection, while for asymptomatic Omicron infections (776, 3.6%) the mean post-infection CIS-fatigue score was not significantly different from the pre-infection score at any of the timepoints (Supplementary file, Figure S8). The sensitivity analysis in which fatigue scores after vaccination after infection were removed showed similar results as the primary analyzes (Supplementary file, Figure S9).

First and repeat omicron infections

Our second analysis assessing first and repeat Omicron infections showed a significantly higher adjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue score during the acute phase of the infection for first infections (5.6; 95%CI 4.9–6.2) compared to repeat infections (4.1; 3.5–4.7) (p < 0.001) (Table 2 and Supplementary file, Figure S10). Differences in mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue score between first and repeat infections at 90 days (1.0 vs 0.7), 180 days (0.1 vs 0.6) and 270 days (0.5 vs 0.5) were small and mostly non-significant (p = 0.245, p = 0.039 and p = 0.97, respectively). Estimated prevalence of severe fatigue was higher before a first (20.3%; 19.2–21.4) than before a repeat infection (17.7%; 16.6–18.8) (p < 0.001); this was also true during the acute phase of the infection (23.3%; 22.2–24.4 for first infections and 20.2%; 19.1–21.4 for repeat infections; p < 0.001). Prevalence of severe fatigue decreased to 21.3% and 18.4% for first and repeat infections at 90 days post-infection. Up to 270 days post-infection, prevalence of severe fatigue remained significantly lower for repeat versus first infections.

Infections during bivalent booster vaccination campaign

Our third analysis among infections reported during the period when bivalent booster vaccinations were available did not show significant differences in adjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue score by bivalent vaccination status during the acute phase of the infection or 90 to 270 days post-infection (Table 2). The estimated adjusted prevalence of severe fatigue at 30 days pre-infection was higher among those who did not receive bivalent vaccination (19.5%; 95%CI 18.4–20.6) than among those who did receive bivalent vaccination (16.3%; 15.2–17.3) (p < 0.001). The prevalence increased to 23.5% and 19.8% for non-vaccinated and vaccinated participants, respectively, during the acute phase of the infection. The prevalence then decreased over time in both groups. The prevalence remained significantly higher among non-vaccinated compared to vaccinated participants up to at least 270 days post infection with odds ratios remaining stable over time. Furthermore, we observed small but significant differences in mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue score between Omicron BA.5 and post-Omicron BA.5 infections at 90 days (p < 0.001), 180 days (p < 0.001) and 270 days (p = 0.032) post-infection, with higher means after Omicron BA.5 infections than post-Omicron BA.5 infections. The differences in mean scores were, however, small (0.9, 1.1 and 0.6, respectively).

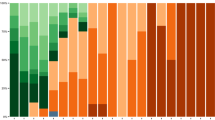

Matched analysis

A total of 10,627 infected individuals could be matched with uninfected individuals (Supplementary file, Table S3). The majority of infections were attributed to the Omicron variant (92%). For the matched analysis, 31,317 CIS-fatigue questionnaires were available for uninfected participants and 41,376 for infected participants (Supplementary file, Figure S11). Visualization of unadjusted mean CIS-fatigue score dynamics over time indicated that means among uninfected individuals remained stable over time while those of matched infected individuals showed large variation over time (Supplementary file, Figure S12). About 20% of the matched uninfected participants showed ≥6 points increase in CIS-fatigue scores, while a similar percentage showed ≥6 points decrease (Supplementary file, Figure S4B). The proportion of participants reporting the maximum CIS-fatigue score was small ( < 2%; Supplementary file, Table S4). Comparable to our first analysis, adjusted means also showed an increase in mean CIS-fatigue scores during the acute phase of the infection compared to pre-infection scores, with a higher peak and a later return to near pre-infection levels for Delta infections compared to Omicron infections (Supplementary file, Figure S13 and Table S2). Adjusted means of matched uninfected participants showed a steady, slightly increasing pattern over time. Adjusted mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores after Delta infection were significantly elevated compared to controls at 90, 180 and 270 days post-infection with differences of 1.9 (1.2–2.7), 1.3 (0.6–2.0) and 1.0 (0.1–1.9), respectively. After Omicron infection, adjusted means only exceeded adjusted means of controls at 90 days post-infection, with a difference of 0.5 (0.2–0.9). The prevalence of severe fatigue among matched uninfected participants slowly increased over time from 14.4% at 30 days pre-infection to 17.7% at 270 days post-infection (Fig. 3). The prevalence was significantly lower than among Delta infected participants during the acute phase of the infection (14.9% vs 27.8%, p < 0.001) and 90 days post-infection (16.3% vs 23.3%, p < 0.001). For Omicron infections this was also observed during the acute phase of the infection (14.9% vs 23.8%, p < 0.001), but no difference was present at 90 days post-infection (16.3% vs 15.8%, p = 0.290).

Infected and uninfected participants were matched on month and year of pre-infection CIS-fatigue assessment, the pre-infection CIS-fatigue score, age group (18–59 years, 60–85 years), sex (male, female), medical risk condition (yes, no), and vaccination status (unvaccinated, primary vaccinated, booster vaccinated). CIS = Checklist Individual Strength; CI = Confidence Interval.

Discussion

We performed a prospective study in which we included an uninfected control group based on serology and in which we adjusted for pre-infection symptoms. We found that fatigue scores increased during SARS-CoV-2 infection, declined rapidly in the first 90 days after infection, but remained elevated until at least 270 days for Delta infections and 120 days for Omicron infections. At 90 to 180 days post-infection, females showed higher post-infection fatigue scores compared to pre-infection fatigue scores than males. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the prevalence of severe fatigue was modest at population level, especially for Omicron. We found prevalences of severe fatigue of 21.2% and 18.9% at 90 days after a first Delta and Omicron infection, respectively, while this prevalence was 18.5% before infection. After 180 days, prevalences of severe fatigue were similar for those with Delta and Omicron infections (18.8% and 18.6% at 180 days). The prevalence of severe fatigue among uninfected participants showed a slightly increasing pattern over time, suggesting no substantial impact of other factors fluctuating over calendar time on observed fatigue among infected persons. Despite some differences at the time of acute infection, we did not observe an effect of primary or booster vaccination or of bivalent booster vaccination (Autumn 2022 campaign) on long-term fatigue. Also, we did not observe substantial differences in prevalence and trends in long-term fatigue between first and repeat Omicron infections.

Only few studies on SARS-CoV-2-related fatigue or PCC included a control group or were able to adjust for pre-infection symptoms. National surveys conducted by the Office for National Statistics among randomly sampled households from the United Kingdom (UK) population included a matched control group25. They studied prevalence of 12 common symptoms, including (but not separately) fatigue, in the pre-omicron period and reported that experiencing any of the symptoms was common among uninfected controls (3.4%). The prevalence among infected participants was 9.4% at 4–8 weeks after infection and decreased to 5.3%, 5.0%, 4.2% and 4.4% at 8–12, 12–16, 16–20 and 20–24 weeks after infection. The Lifelines COVID-19 cohort study, a prospective, population-based observational cohort study of 76,422 participants in the Netherlands, corrected for pre-existing symptoms before the onset of COVID-19, as well as symptom dynamics in a matched control group26. They showed that fatigue of at least moderate severity, i.e., score of ≥ 3 on a 5-point Likert scale, was present among uninfected controls (3.7%). Also, the overall percentage of participants with fatigue of at least moderate severity ( ≥ 3 on a 5-point Likert scale) at 90–150 days after infection was 7.0%. This was higher than the percentage of participants with a substantial increase (1 point) in fatigue severity to at least moderate severity (4.9%), thus when taking into account severity before infection. Compared to the prevalence of symptoms in these two studies, pre-infection prevalence of severe fatigue among our study population was considerably higher (18.5%). However, we assessed fatigue as a standalone symptom (in contrast to the British study), and we used CIS methodology that has been validated for the Dutch population (in contrast to the Dutch Lifelines study). The prevalence of the pre-infection severe CIS-fatigue that we observed was comparable to the prevalence of severe CIS-fatigue in the Dutch population (18%)24. The absolute increase in prevalence as a result of infection at 90 days post-infection (21.2% for Delta infections) was comparable to what the other two studies reported between controls and infected participants at 12–16 weeks (3.4% vs 5.0%) and 90–150 days (3.7% vs 7.0%) after infection.

Both above mentioned studies also reported on risk factors for long-term symptoms, or specifically long-term fatigue. The study from the UK found a higher percentage of study participants reporting any of 12 symptoms (including fatigue) 12–16 weeks after infection in females (5.4% vs 4.5% in males), adults aged 50–69 years (5.8% vs 4.5% in 25–34 year-olds), and people living with a pre-existing health condition (7.4% vs 4.5% in those without). For fatigue as well as for other symptoms, the Dutch Lifelines study reported longer persistence of increased symptom severity (increase on a 5-point Likert scale) 90–150 days post-infection in females than males. Comparable to the Dutch study, which also adjusted for fatigue present before infection, we observed (small) differences in post- vs pre-infection fatigue score at 90 and 180 days post-infection by sex but not by age group. That we observed no differences by other determinants might thus be the result of our adjustment for pre-infection scores.

The majority of the published studies included data from the first one to two years of the pandemic and literature is limited on fatigue after Omicron infections. A US study among community-based cases described a lower proportion of participants reporting symptoms at 90 days after infection for Omicron versus pre-Omicron cases, but not specifically for fatigue27. Yet, pre-Omicron infections included other variants than Delta. A Dutch prospective study assessing prevalence of severe fatigue, also using the CIS-fatigue score, reported significantly higher prevalence at 3 months after Delta (25.6%) compared to Omicron infections (22.6%)11. With the increasing level of immunity against COVID-19 and the emergence of Omicron, the proportion of infections being asymptomatic has increased28. A meta-analysis using data of five studies reported 81% lower risk of fatigue after asymptomatic versus symptomatic infection, with a pooled prevalence of fatigue of 9% after asymptomatic and 22% after symptomatic infection29. They did not study pre-infection prevalence of fatigue and attributed this 9% to the infection. At a population level, we did not show significant differences in fatigue compared with pre-infection levels up to 270 days post asymptomatic Omicron infection, while differences post asymptomatic Delta infection remained higher than pre-infection levels up to at least 270 days. Therefore, a potentially larger proportion of Omicron infections being asymptomatic is not expected to fully explain the lower impact of Omicron infection on post-infection fatigue compared to Delta infection. The emergence of Omicron and the increasing proportion of infections being asymptomatic suggests the likelihood of lingering post-infection fatigue or developing PCC when infected might have decreased since the start of the pandemic.

Repeat infections are increasingly common30. A study from the US Department of Veterans Affairs showed that repeat infection contributed to additional risk of fatigue (HR: 2.33; 95%CI 2.14–2.52) up to six months post-infection31. However, this study estimated the risk of fatigue after repeat infection compared to no repeat infection rather than the risk after first versus repeat infection. Data from the UK COVID-19 Infection Survey of 110,844 first and 11,244 second Omicron infections showed lower prevalence of self-reported PCC at 12-20 weeks after second (2.4%) compared to first infection (4.0%)15. Among those with self-reported PCC, prevalence of fatigue was slightly, non-significantly higher after first (61.6%) than after second infection (57.7%). A Dutch prospective study found higher prevalence of severe fatigue on the CIS-fatigue subscale after Omicron repeat infection (28%) than Omicron first infection (23%), but did not take into account prevalence of severe fatigue pre-infection11. Pre-repeat infection mean fatigue scores might have already been higher than first infection pre-scores as a result of prior non-Omicron infections. Also, the study was reliant on SARS-CoV-2 testing at testing facilities, of which accessibility decreased during the Omicron period. Assuming the proportion repeat infections increased with passing time, this might have resulted in more severe repeat infections coming forward for testing. We did not find substantial differences in CIS-fatigue scores from 90 days post-infection between first and repeat infections when taking pre-infection levels of fatigue into account. Results suggest there remains a risk of long-term fatigue after repeat infection and this risk is comparable to the first infection.

Meta-analyzes suggest a protective effect of vaccination on the risk of developing PCC, including fatigue19,20,32. However, included studies are of variable quality and substantially heterogeneous in study design, study period, study population and measured outcomes. A study by the US Veterans Affairs reported a protective effect of vaccination on the risk of fatigue more than 30 days after infection for hospitalized and ICU cases, but not for non-hospitalized cases33. Another study from the US, among community-based cases rather than severe COVID-19 cases, reported that vaccinated cases had lower risk of fatigue and relative fatigue severity at 30 days after infection, but not at 90 days after infection27. A Dutch prospective cohort study among community cases reported severe fatigue to be less prevalent at three months post-infection in cases with a booster (21.0%) compared to the primary course cases (23.1%), but the difference was non-significant11. A study from Israel analyzing electronic health records found a reduced risk of dyspnea 30-90 days post-infection in vaccinated vs unvaccinated individuals, while risk of all other outcomes, including weakness, were comparable34. In line with these results, we did not find a difference by vaccination status in fatigue from 90 days post-infection onwards among community, non-severe COVID-19 cases.

Literature on the effect of bivalent vaccination on long-term fatigue is scarce. A US longitudinal prospective survey-based study among 505 symptomatic adult outpatients reported prevalence of fatigue to be consistently lower among bivalent vaccinated participants than those without bivalent vaccination through six months post-infection, with 13.7% vs 23.7% at 6 months35. Their results possibly differed from ours because they included more severe COVID-19 cases and did not adjust for pre-infection levels of fatigue, which in our population was higher among non-vaccinated. Our results imply that new booster vaccination campaigns are not indicated to prevent long-term fatigue after SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, new booster vaccinations have shown benefit in preventing severe COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 infections thereby indirectly also preventing long-term fatigue36,37.

This study has several strengths. Fatigue was assessed using a validated questionnaire at regular time points irrespective of infection. Unlike many other studies, we took pre-infection levels of fatigue into account to adjust for background prevalence of fatigue. We also included uninfected participants as controls to take into account changes in background prevalence over time caused by other factors. Furthermore, our data shows that the VASCO study population represents the Dutch general population well, as the pre-infection CIS-fatigue results, and pre-infection differences between age groups, sexes, and medical risk groups, that we observed are comparable with earlier results from population cohorts24,38,39,40.

This study also had limitations. Firstly, although the dropout rate among VASCO participants is relatively low41, there might be selection bias due to selective dropout. Secondly, fatigue is a complex multi-faceted phenomenon and the CIS-fatigue questionnaire does not cover all aspects of fatigue38,42,43. It was, for example, not designed to assess post-exertional malaise38,42,44, a specific symptom described by patients with PCC. Fatigue is only one of the PCC symptoms and results cannot be conveyed to other PCC symptoms, or PCC in general. Also, despite somewhat reassuring results about the impact of long-term fatigue after Omicron infection on the population level, we cannot exclude that on the individual level people can still develop long-term persisting fatigue after infection. Furthermore, the circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant was defined by calendar time and is therefore likely to be correlated with implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions over time; both may be independently associated with fatigue. We observed an increasing pattern in fatigue over time among uninfected participants with even somewhat higher fatigue than in Omicron infected participants from 180 days after infection onwards, in line with a similar observation in controls in another Dutch study on post-COVID45. Although we cannot rule out selective drop-out of controls as an explanation for these observations, an alternative explanation might be increased circulation of other viruses after lifting non-pharmaceutical COVID-19 measures in combination with viral interference. Such viral interference may have led to temporal increased immunity against other respiratory viruses in cases compared to the uninfected controls46,47,48. Additionally, as not all individuals produce N-antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection and N-antibody concentrations wane over time since infection49,50, a small percentage of infections included as first infection might have actually been a repeat infection. Also, a small percentage of the controls might have actually been infected previously. Lastly, we were not able to adjust for repeated measurements within persons in multivariate models. However, we do not expect a large influence on our results, as the number of participants (23,591) is much larger than the number of questionnaires per person (maximum of 6). Also, no differences were observed with or without adjustment for repeated measurements in univariate models.

In this well-controlled prospective cohort study increased levels of mean fatigue scores after Omicron infection had resolved from 120 days post-infection, unlike after Delta infection. With the emergence of Omicron and the increasing level of immunity against SARS-CoV-2 globally, infections appear to have less impact on long-term fatigue. We did not find evidence of an effect of vaccination on mean long-term fatigue scores among infected individuals at population level. However, as vaccination has shown benefit in preventing severe COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 infections it thereby indirectly also prevents long-term symptoms.

Methods

Study design and study population

The VAccine Study COvid-19 (VASCO) is a large ongoing prospective cohort study with five-year follow-up in the Netherlands with the primary aim to estimate COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection41. Between 3 May 2021 and 15 December 2021, 45,552 community-dwelling adults aged 18–85 years were included. Participants had to be able to understand Dutch, as all study materials were written in Dutch. Sociodemographic factors, health status, COVID-19 vaccination, COVID-19 related symptoms, and positive SARS-CoV-2 (self-)test data were collected using online questionnaires (every month in year 1 and every three months thereafter). Participants could also report any positive SARS-CoV-2 test in real time via the study website or mobile phone application. To facilitate testing, self-tests were provided to participants from May 2022 onwards, when community testing was scaled down. Data on self-reported fatigue was collected every 3 months using a questionnaire validated in the Dutch general population for this purpose (the fatigue severity subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength or CIS)38,44. Additionally, participants were asked to take a self-collected finger prick blood sample at home at baseline and every 6 months during follow-up.

VASCO is conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the not-for-profit independent Medical Ethics Committee of the Stichting Beoordeling Ethiek Biomedisch Onderzoek (BEBO), Assen, the Netherlands (NL76815.056.21). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment into the study.

SARS-CoV-2 infection

First infections were defined as a first reported positive SARS-CoV-2 test without serological evidence of an unreported infection before this positive test. An unreported infection was detected by the presence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (N-antibodies) in finger prick blood samples. Samples were analyzed with the Anti-SARS-CoV-2 assays on the Cobas e801 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) (see41 for an elaborate description). First infections were included if at least one CIS-fatigue score was available 1–90 days pre-infection, and at least one 0–300 days post-infection. If participants experienced more than one infection, post-infection questionnaires of the first infection had to be at least 14 days prior to the subsequent infection. Repeat infections were defined as a reported positive SARS-CoV-2 test at least 4 weeks after a preceding reported or unreported infection. Repeat infections were included if the infection and its preceding infection were considered to be caused by Omicron (see below). Repeat infections were included if at least one CIS-fatigue score was available 1–90 days pre-infection, and at least one up to 300 days post-infection. Pre-infection questionnaires of repeat infections had to be at least 180 days after the preceding infection. Participants were considered uninfected up to 14 days prior to their first reported positive test or up to their latest blood sample in which no N-antibodies were detected. Participants without blood sample results were excluded as controls. Participants were included as uninfected controls if at least two CIS-fatigue scores were available while remaining uninfected.

The virus variant of concern causing the infection was based on the calendar period in which > 90% of the cases in the Netherlands was caused by this variant51. Infections were considered to be caused by either the Delta (12 July 2021–19 December 2021) or Omicron (from 10 January 2022) variant. The Omicron period was subdivided into Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 (10 January 2022–5 June 2022), Omicron BA.5 (6 June 2022 – 13 November 2022) and post-Omicron BA.5 (from 14 November 2022). In the latter period multiple different Omicron subvariants circulated in the Netherlands. Infections during the transition period from Delta to Omicron (n = 362) were excluded from the analyzes. Infections were classified as symptomatic if symptoms were reported either in the questionnaire in which the infection was reported, or in the questionnaire one month after the reported infection. Infections were classified as asymptomatic if participants reported to not have experienced any SARS-CoV-2 related symptoms.

Outcomes

The CIS-fatigue severity subscale consists of 8 questions on a 7-point Likert scale that assess the respondent’s experience of fatigue (Supplementary file, Table S5). Scores range between 8 and 56 with higher scores indicating more severe fatigue. The cut-off for severe fatigue is ≥ 3538. The CIS-fatigue has been well validated among patients with chronic fatigue and in the working population38,42. The average CIS-fatigue score in the general Dutch population is 2338. We defined the post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue score as the difference between a post-infection CIS-fatigue score (measured 0–300 days after positive test) and the latest pre-infection CIS-fatigue score (14–90 days before positive test). Infections for which only one pre-infection CIS-fatigue score was available which was 0–14 days before infection (i.e., positive test) were excluded from the analysis on post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores.

Covariables

Covariables that were expected to be associated with the outcome were measured. Demographic data were collected at baseline. A medical risk condition was defined as present when a participant reported to have one or more of the following conditions: diabetes mellitus, lung disease or asthma, asplenia, cardiovascular disease, immune deficiency, cancer, liver disease, neurological disease, renal disease, organ or bone marrow transplantation.

Self-reported vaccination data were cross-checked through linkage with the Dutch national COVID-19 vaccination Information and Monitoring System (CIMS)52,53. The COVID-19 vaccination program in the Netherlands started on 6 January 2021 and booster campaigns with Comirnaty and Spikevax mRNA vaccines were initiated on 18 November 2021, 4 March 2022, 19 September 2023 and 2 October 2023 (see54 for detailed information). Vaccination status was categorized as unvaccinated (no vaccination received), primary vaccination series received (one dose of Jcovden 28+ days ago, or two doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty or Spikevax 14+ days ago), or primary vaccination series and one or multiple boosters received (7+ days ago). In the Netherlands, booster vaccinations administered between 19 September 2022 and 2 October 2023 were bivalent boosters, either original/Omicron BA.1 or original/Omicron BA.4/BA.5.

Statistical analyzes

We explored unadjusted CIS-fatigue scores by describing mean post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores by 10 days’ intervals since infection and by describing to what extent on the individual level participants showed an increase or decrease of >=6 points in CIS-fatigue scores post- vs pre-infection55,56. We performed a multivariable analysis on three different outcomes: CIS-fatigue scores, post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores, and severe fatigue prevalence. CIS-fatigue scores and post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores were estimated as a function of time since infection (penalized spline) using generalized additive models (GAM) with Gaussian distributed outcome. The probability of severe fatigue was estimated using a GAM with binomial distributed outcome with a penalized spline for time since infection and expressed as the estimated prevalence of severe fatigue. We were not able to adjust for repeated measurements within persons in the multivariate analyzes, but univariately no differences were observed with or without adjustment for repeated measurements (Supplementary file, Figure S14).

The first analysis included all first infections and the covariables dominant virus variant (Delta, Omicron), sex, age group, presence of a medical risk condition and vaccination status. A second analysis included both first and repeat Omicron infections. Included covariables were the same as in the first analysis with an additional covariable indicating first or repeat infection. A third analysis was limited to infections reported during the period in which bivalent booster vaccinations were available to estimate post-infection fatigue by bivalent booster vaccination status. Other covariables were similar to the first two models. All models are summarized in Supplementary file, Table S6. The fitted models were used to estimate and visualize the marginal means. Estimated marginal means are defined as equally weighted means of predictions at specified margins and are often called “adjusted means”57. Differences in estimated marginal means (referred to as “adjusted means” throughout the manuscript) between groups were determined and tested for significance using a t-test at 0, 90, 180, and 270 days post-infection. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In the main analyzes, we assumed no effect of vaccination after infection on fatigue scores. A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding all questionnaires that were completed when a vaccination had been given after an infection to assess the possible effect of this assumption. An additional sensitivity analysis was performed stratifying first infections as symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. As a sensitivity analysis on the used smoothing terms, the penalized spline was replaced by a cubic regression spline. This resulted in only minor differences in results (Supplementary file, Table S7 and Figures S15–S17).

Furthermore, to rule out any bias by seasonal patterns in fatigue we additionally performed an analysis where we matched first infected and uninfected individuals on month and year of pre-infection CIS-fatigue assessment, the pre-infection CIS-fatigue score, age group, sex, presence of a medical risk condition, and vaccination status. Any CIS-fatigue questionnaire of an uninfected individual could be considered a pre-infection CIS-fatigue assessment and could be matched to an infected individual’s pre-infection CIS-fatigue assessment. After matching, all subsequent CIS-fatigue assessments (at least one and while remaining uninfected) were compared to the post-infection CIS-fatigue assessments of infected individuals. The matching ratio was 1:1 and uninfected individuals could not be included more than once. Post- vs pre-infection CIS-fatigue scores and prevalence of severe fatigue were estimated as before by a function of time since first infection by infection status.

All statistical analyzes were performed in statistical package R version 4.3.3, using packages mgcv58, emmeans59, and MatchIt60.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Anonymized data reported from this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request, with a response timeframe of 3 weeks. The dataset may include individual data and a data dictionary will be provided. Data requests should include a proposal for the planned analyzes. Data transfer will require a signed data sharing agreement.

Code availability

Analysis code is available upon request from the corresponding author, with a response timeframe of 3 weeks.

References

WHO. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 (2024).

Goërtz, Y. M. J. et al. Symptoms and quality of life before, during, and after a SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive or negative test: data from Lifelines. Sci. Rep. 13, 11713 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of 8697 patients with COVID-19 in China: a meta-analysis. Fam. Med. Community Health 8, e000406 (2020).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med 27, 601–615 (2021).

Joli, J. et al. Post-COVID-19 fatigue: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 13, 947973 (2022).

Poole-Wright, K. et al. Fatigue outcomes following COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 13, e063969 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for persistent symptoms after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 30, 328–335 (2024).

Peghin, M. et al. Post-COVID-19 symptoms 6 months after acute infection among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27, 1507–1513 (2021).

Baruch, J. et al. National long COVID impact and risk factors. Public Health 213, 177–180 (2022).

Du, M. et al. Comparison of Long COVID-19 Caused by different SARS-CoV-2 strains: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 16010 (2022).

de Bruijn, S. et al. Lower prevalence of post-Covid-19 condition following omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection. Heliyon 10, e28941 (2024).

Office for National Statistics (ONS). New-onset, self-reported long COVID after coronavirus (COVID-19) reinfection in the UK: 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/newonsetselfreportedlongcovidaftercoronaviruscovid19reinfectionintheuk/latest (2023).

Percze, A. R. et al. Fatigue, sleepiness and sleep quality are SARS-CoV-2 variant independent in patients with long COVID symptoms. Inflammopharmacology 6, 2819–2825 (2023).

Townsend, L. et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS One 15, e0240784 (2020).

Bosworth, M. L. et al. Risk of new-onset long COVID following reinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: a community-based cohort study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 10, ofad493 (2023).

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. et al. Long-COVID Symptoms in individuals infected with different SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a systematic review of the literature. Viruses 14, 2629 (2022).

Wu, N. et al. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. Lancet Respiratory Med. 11, 439–452 (2023).

Zheng, C. et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 114, 252–260 (2022).

Watanabe, A. et al. Protective effect of COVID-19 vaccination against long COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 41, 1783–1790 (2023).

Byambasuren, O. et al. Effect of covid-19 vaccination on long covid: systematic review. BMJ Med 2, e000385 (2023).

Notarte, K. I. et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 53, 101624 (2022).

Høeg, T. B., Ladhani, S. & Prasad, V. How methodological pitfalls have created widespread misunderstanding about long COVID. BMJ Evid. -Based Med. 29, 142–146 (2024).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Prevalence of post COVID-19 condition symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort study data, stratified by recruitment setting. In: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, ed. Stockholm, (2022).

Goërtz, Y. M. J. et al. Fatigue in patients with chronic disease: results from the population-based lifelines Cohort study. Sci. Rep. 11, 20977 (2021).

Office for National Statistics (ONS). technical article: updated estimates of the prevalence of post-acute symptoms among people with coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK: 26 April 2020 to 1 August 2021 (2021).

Ballering, A. V. et al. Persistence of somatic symptoms after COVID-19 in the Netherlands: an observational cohort study. Lancet 400, 452–461 (2022).

Maier, H. E. et al. Reduction in long COVID symptoms and symptom severity in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated adults. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 11, ofae039(2024).

Yu, W. et al. Proportion of asymptomatic infection and nonsevere disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: a systematic review and analysis. J. Med Virol. 94, 5790–5801 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Long-term consequences of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 1613 (2023).

Medić, S. et al. Risk and severity of SARS-CoV-2 reinfections during 2020-2022 in Vojvodina, Serbia: a population-level observational study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 20, 100453 (2022).

Bowe, B., Xie, Y. & Al-Aly, Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat. Med 28, 2398–2405 (2022).

Tsampasian, V. et al. Risk factors associated with post−COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 183, 566–580 (2023).

Al-Aly, Z., Bowe, B. & Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 28, 1461–1467 (2022).

Mizrahi, B. et al. Long covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: nationwide cohort study. Bmj 380, e072529 (2023).

Di Fusco, M. et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 BA.4/5 Bivalent COVID-19 Vaccine against Long COVID Symptoms: A US Nationwide Study. Vaccines (Basel). 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12020183 (2024).

Huiberts, A. J. et al. Effectiveness of Omicron XBB.1.5 vaccine against infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB and JN.1 variants, prospective cohort study, the Netherlands, October 2023 to January 2024. Eurosurveillance 29, 2400109 (2024).

van Werkhoven, C. H. et al. Early COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness of XBB.1.5 vaccine against hospitalisation and admission to intensive care, the Netherlands, 9 October to 5 December 2023. Eurosurveillance 29, 2300703 (2024).

Worm-Smeitink, M. et al. The assessment of fatigue: Psychometric qualities and norms for the Checklist individual strength. J. Psychosom. Res. 98, 40–46 (2017).

Engberg, I. et al. Fatigue in the general population- associations to age, sex, socioeconomic status, physical activity, sitting time and self-rated health: the northern Sweden MONICA study 2014. BMC Public Health 17, 654 (2017).

Galland-Decker, C., Marques-Vidal, P. & Vollenweider, P. Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in the Lausanne middle-aged population: a population-based, cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 9, e027070 (2019).

Huiberts, A. J. et al. Cohort profile: an observational population-based cohort study on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the Netherlands - the VAccine Study COVID-19 (VASCO). BMJ Open 14, e085388 (2024).

Beurskens, A. J. H. M. et al. Fatigue among working people: validity of a questionnaire measure. Occup. Environ. Med. 57, 353–357 (2000).

Dittner, A. J., Wessely, S. C. & Brown, R. G. The assessment of fatigue: a practical guide for clinicians and researchers. J. Psychosom. Res. 56, 157–170 (2004).

Vercoulen, J. H. M. M. et al. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 38, 383–392 (1994).

van der Maaden, T. et al. Prevalence and severity of symptoms 3 months after infection with SARS-CoV-2 compared to test-negative and population controls in the Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 227, 1059–1067 (2022).

Chan, K. F. et al. Investigating viral interference between influenza A virus and human respiratory syncytial virus in a ferret model of infection. J. Infect. Dis. 218, 406–417 (2018).

Drori, Y. et al. Influenza A virus inhibits RSV infection via a two-wave expression of IFIT proteins. Viruses 12, 1171 (2020).

Kramer, S. C. et al. Characterizing the interactions between influenza and respiratory syncytial viruses and their implications for epidemic control. Nat. Commun. 15, 10066 (2024).

den Hartog, G. et al. Assessment of hybrid population immunity to SARS-CoV-2 following breakthrough infections of distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants by the detection of antibodies to nucleoprotein. Sci. Rep. 13, 18394 (2023).

van den Hoogen, L. L. et al. Seropositivity to nucleoprotein to detect mild and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: a complementary tool to detect breakthrough infections after COVID-19 vaccination? Vaccine 40, 2251–2257 (2022).

Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. varianten van het coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 2022. https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/virus/varianten (2022).

Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. role of RIVM in the COVID-19 vaccination 2022. https://www.rivm.nl/en/covid-19-vaccination/role-of-rivm (2022).

Huiberts, A. J. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of primary and booster COVID-19 vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Netherlands from July 12, 2021 to June 6, 2022: a prospective cohort study. Int J. Infect. Dis. 133, 36–42 (2023).

Lanooij, S. et al. Vaccinatiegraad COVID-19 vaccinatie Nederland, 2022. COVID-19 vaccination coverage in the Netherlands, 2022: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu RIVM, https://www.rivm.nl/publicaties/vaccinatiegraad-covid-19-vaccinatie-nederland-2022 (2024).

Knoop, H., van der Meer, J. W. M. & Bleijenberg, G. Guided self-instructions for people with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 193, 340–341 (2008).

Kuut, T. A. et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy targeting severe fatigue following coronavirus disease 2019: results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 687–695 (2023).

Lenth R. Basics of estimated marginal means. http://cran.nexr.com/web/packages/emmeans/vignettes/basics.html (2018).

Wood SN. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, Second Edition (2nd ed): (Chapman and Hall/CRC 2017).

Lenth R. _emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means_. R package version 1.8.7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (2023).

Ho, D. et al. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42, 1–28 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Hd.M., Jvd.W., Svd.H., Cvd.W., and M.K. designed the study. A.H., Sd.B., S.A., C.H., and M.S. contributed to data cleaning and/or data analysis. A.H. drafted the manuscript. Sd.B., S.A., C.H., M.S., Hd.M., Jvd.W., Svd.H., Cvd.W., and M.K. critically reviewed the manuscript. M.K. is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huiberts, A.J., de Bruijn, S., Andeweg, S.P. et al. Prospective cohort study of fatigue before and after SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Netherlands. Nat Commun 16, 1923 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56994-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56994-5