Abstract

Effective antitumor nanomedicines maximize therapeutic efficacy by prolonging drug circulation time and transporting drugs to target sites. Although numerous nanocarriers have been developed for accurate tumor targeting, their limited water solubility makes their stable storage challenging, and poses biosafety risks in clinical translation. Herein, we choose reduced glutathione (GSH) to quick synthesize gram-scale water-soluble large amino acids mimicking carbon quantum dots (LAAM GSH-CQDs) enriched in steric chain amino acid groups with solubility of up to 2.0 g mL−1. The water-solubility arises from a hexagonal arrangement formed between amino acid groups and water molecules through hydrogen bonding, producing chair-form hexamer hydration layers covering LAAM GSH-CQDs. This endows a noticeable stability against long-term storage and adding electrolytes. Specifically, they exhibit negligible protein absorption, immunogenicity, and hemolysis, with stealth effect, showing an extraordinarily tolerated dose (5000 mg kg−1) in female mice. The rich amino acid groups simultaneously endow them considerable tumor-specific targeting. The loading of first-line chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin onto LAAM GSH-CQDs through π-π stacking without sacrificing their merits achieves superior tumor inhibition and minimal side effects compared to commercial doxorubicin liposomal. The tumor-targeted drug delivery platform offered by LAAM GSH-CQDs holds significant promise for advancing clinical applications in cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanomaterials for tumor drug delivery have the advantages of prolonged drug circulation time, enhanced stability, and increased tumor accumulation, achieving maximum therapeutic efficacy and minimal side effects1. Nanocarriers, such as liposomes and albumin, have been developed to passively target tumors through the enhanced permeation and retention effect; however, they only offer limited targeting effects and are affected by the intrinsic pathophysiological heterogeneity of tumors2,3. We have reported large amino acids mimicking carbon quantum dots (LAAM TC-CQDs), which specifically target the overexpressed L-type amino acid transporter-1 (LAT1) in tumor cells, regardless of their origins and locations, but not in normal tissues with limited expression4. However, the low water solubility of nanocarriers necessitates the addition of organic co-solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide during biological experiments, thus inducing potential safety risks and restricting their development towards the clinical translation stage.

Physiological fluid is an aqueous system that can transport substances dissolved in body fluid throughout the body and in and out of cells. Hence, water solubility is important for in vivo transportation of nanocarriers5. Most nanomaterials are dispersed in water through the mutual electrostatic repulsion produced by the charged nanomaterial surfaces6. Increasing the concentration or heating accelerates collisions between nanomaterials, leading to their instability and coalescence, thus limiting their solubility in water. When nanomaterials are used as nanocarriers for in vivo transportation, electrolytes or high ion concentrations screen their electrostatic repulsive interactions, resulting in their destabilization and aggregation7,8. Formation of nanocarrier aggregates causes embolism and influences their biodistribution, resulting in prolonged tissues retention9. In addition, nanomaterials dispersed in water lack polar groups to form sufficient hydrogen bonds with water, resulting in a relatively high surface free energy in water10. After entering an organism, non-polar groups such as alkyl chains on the surfaces of nanocarriers tend to damage the hydration membrane of proteins and interact with the hydrocarbon groups (hydrophobic sides) of amino acid residues on proteins to form a dispersion force, reducing the surface free energy and forming a protein corona11,12. The targeting ligands on the surface of nanocarriers can be shielded by the protein corona, causing a loss of targeting capacity13,14. The adsorption of opsonin-like immunoglobulins and apolipoproteins triggers recognition and clearance by cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), thus shortening the blood circulation time of nanocarriers and preventing nanocarriers from reaching the target organs15.

Studies have attempted to coat nanocarriers with a stabilizing shell of water-soluble polymers or zwitterionic molecules16,17. Water-soluble polymers like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) interact strongly with water, resulting in a shell of tightly bound water molecules18,19. PEGylation on nanocarriers generates a hydrated cloud with a large excluded volume, thus sterically precluding nanocarriers from aggregating and hindering the interaction with proteins to decrease the uptake by MPS18,19. Unfortunately, the steric hindrance of PEG masks the ability to target ligands16. PEGylation accelerates the clearance of liposomes from the blood circulation when administered in multiple doses due to the production of anti-PEG antibodies at the first injection20,21. The instability of PEG occurs from the degradation or chemical changes induced by heating, radiation, or oxygen18, and the surface density of PEG cannot be precisely controlled and quantified22. Another approach is to incorporate zwitterion functionalities onto the nanocarrier surface, using various amino acids or polypeptides as precursors for direct synthesis of nanocarriers such as CQDs23,24. The strong electrostatic interactions between water and zwitterions are believed to contribute to the high degree of stability observed with zwitterionic systems17. Remaining issues of complex purification processes, mass production while retaining the desired features, and accurate structural analysis are still challenging. An alternative strategy for obtaining water-soluble nanocarriers is crucial.

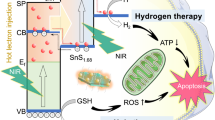

Here, we report the direct fabrication of water-soluble tumor-targeted LAAM GSH-CQDs with a water solubility of 2.0 g mL−1 on a one-pot gram-scale using reduced glutathione (GSH) (Fig. 1a). The LAAM GSH-CQDs are surrounded by 22 amino acid groups sterically arranged alternately up and down with a size of about 3.2 nm (Fig. 1b). The water-soluble LAAM GSH-CQDs are uniform and stable towards long-term storage, heating and adding electrolytes, and ultrahigh-tolerated dose in mice, neglecting stickiness to proteins and hemolytic activity. Water molecules combine with amino acid groups via hydrogen bonds to form a hexagonal arrangement, inducing the formation of chair-form hexamer hydration layers covering the LAAM GSH-CQDs. Triple tumor inhibition efficacy with reduced side effects was observed after treatment with doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded LAAM GSH-CQDs (DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs) compared to DOX and commercial doxorubicin liposomal (Doxil), suggesting that the LAAM GSH-CQDs platform offers a biosafe strategy for drug delivery and tumor therapeutic applications.

a A synthesis diagram of LAAM GSH-CQDs. b A schematic diagram showing the structure of LAAM GSH-CQDs. c Photos of 500 mL reactor and LAAM GSH-CQD powder. d The UV-vis absorption and PL emission (excitation at 420 nm) spectra of LAAM GSH-CQDs, and insets are photos of LAAM GSH-CQDs under daylight and 365 nm UV light. e A photo of LAAM GSH-CQDs at a concentration of 2.0 g mL−1 in water, the PL spectra of water-soluble LAAM GSH-CQDs at different heights, photos of LAAM GSH-CQDs at a concentration of 10 mg mL−1 after storing at 25 °C for 10 months, the water-soluble property of LAAM GSH-GQDs: photos of LAAM GSH-CQDs at a concentration of 10 mg mL−1 after adding electrolyte of 0.1 g NaCl, NH4Cl, Na2SO4, or NaNO3, heating to 100 °C, or centrifugating at a speed of 10000 × g for 3 min, and photos of contact angle measurements of LAAM GSH-CQDs using water and diiodomethane as the testing solvents. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Results

Synthesis of water-soluble LAAM GSH-CQDs

The synthesis of LAAM GSH-CQDs involves the solvothermal treatment of GSH and formamide in a 500 mL reactor at 130 °C for 6 h (Fig. 1c), followed by purification through a simple solvent washing procedure without the need for other purification processes. The washing process was carried out using methanol-dichloromethane as the eluent through vacuum filtration, followed by washing with water. A dark green powder was obtained (Fig. 1c) after drying in an oven at 70 °C. Approximately 1.8 g of LAAM GSH-CQDs was obtained from the single-batch production using 8.0 g GSH (Supplementary Fig. 1), demonstrating the feasibility of this method for rapid, gram-scale production.

The ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectrum shows an absorption peak at around 250 nm representing the π–π* transition of aromatic C = C bonds, an obvious absorption peak at ~420 nm, and three characteristic peaks at 604, 627, and 676 nm assigned to the aromatic π system containing π–π* and n–π* transitions of C = O and C = N bonds (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2a)23. The maximum photoluminescence (PL) emission of the LAAM GSH-CQD water solution was centered at a wavelength of 683 nm with an optimized excitation wavelength of 420 nm (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2b), corresponding to the red fluorescence. The fluorescence emission wavelength was nearly independent of the excitation wavelength (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The absolute fluorescence quantum yield of LAAM GSH-CQDs was determined to be ~16%.

Figure 1e displays a photograph of the LAAM GSH-CQDs dissolved in water at a concentration of 2.0 g mL−1 with a pH of 4.3. The maximum concentration of LAAM GSH-CQD powder dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with a pH of 7.4 was 10.0 mg mL−1. The shape, position, and intensity of the PL emission peak obtained from regions with different heights in the LAAM GSH-CQD water solution were almost the same, indicating the homogeneity of the LAAM GSH-CQDs in water. Centrifugation of the LAAM GSH-CQD water solution at a speed of 10000×g for 3 min, heating LAAM GSH-CQD water solution up to 100 °C, or adding an electrolyte such as 0.1 g NaCl, NH4Cl, Na2SO4 or NaNO3 to LAAM GSH-CQD water solution, did not cause coagulation. These observations are different from the characteristics of nanomaterials dispersed in water through electrostatic repulsion. We selected graphene oxide CQDs (GO-CQDs) as an example nanomaterial and performed a comparison study25. We found that, unlike LAAM GSH-CQDs, GO-CQDs are unstable and quickly precipitated after centrifugation, heating, or electrolyte addition (Supplementary Fig. 3)26. This improvement in stability is crucial for facilitating further biological applications of LAAM GSH-CQDs.

A sessile drop measurement manifests the LAAM GSH-CQDs with an average contact angle of 6.5o for water and 58.6o for diiodomethane (Fig. 1e). A water contact angle close to 0o reflects the ultrahydrophilic property of the LAAM GSH-CQDs27. The LAAM GSH-CQD water solution could be stored at 25 °C for >10 months without precipitation or aggregation. The PL spectrum of the LAAM GSH-CQD water solution remained almost unchanged after storage at 25 °C for 10 months (Supplementary Fig. 4). The results verified the long-term storage stability of the LAAM GSH-CQDs. Immersing under various physiological pH ranging from 5.5 – 8.0, adding matrix metalloproteinase-2 or amino acids, incubating in saline, PBS, or PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), or storing at 4 °C and –20 °C did not significantly affect the PL intensity of LAAM GSH-CQDs (Supplementary Fig. 5). The PL intensity of the LAAM GSH-CQDs was also stable under xenon lamp irradiation for 12 h (Supplementary Fig. 6). These results demonstrate the photostability and physiological stability of the LAAM GSH-CQDs. Together, these data verify the water-soluble properties of the LAAM GSH-CQDs with high stability and homogeneity.

Structure of water-soluble LAAM GSH-CQDs

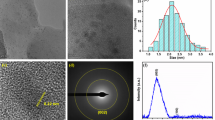

The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image shows that the average size of the LAAM GSH-CQDs is 3.2 ± 0.5 nm with uniform distribution and well dispersion (Fig. 2a, b). The TEM image of LAAM GSH-CQDs after storage at 25 °C for 10 months still exhibited uniformity with an average size of ~3.2 nm (Supplementary Fig. 7), demonstrating the stability of LAAM GSH-CQDs. The spherical aberration-corrected TEM (AC-TEM) image (Fig. 2c) revealed an oval shape with high crystallinity of LAAM GSH-CQDs showing a lattice space of 0.21 nm, which is assigned to the in-plane (100) plane of graphite28,29. The electron diffraction pattern of the LAAM GSH-CQDs manifests a hexagonal pattern for graphite with a calculated I{1100}/I{2110} intensity ratio of 1.2 (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating that the LAAM GSH-CQDs are mostly composed of a monolayer30,31. The atomic force microscopy (AFM) image shows that the thickness is <1 nm (Supplementary Fig. 9), with most of the LAAM GSH-CQDs consisting of a monolayer32,33. The hydrodynamic diameter of the LAAM GSH-CQDs was 120.4 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.482 (Supplementary Fig. 10a). The surface zeta potential of the LAAM GSH-CQDs was measured to be –24.3 mV (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the LAAM GSH-CQDs exhibits a broad peak near 23o (Supplementary Fig. 11a), belonging to the (002) plane of graphite with an interplanar space of 0.38 nm34,35. Raman spectrum analysis revealed the presence of the sp3 defect D band (1374 cm−1) and sp2 structure G band (1609 cm−1) with intensity ratio (ID/IG) of 0.48 (Supplementary Fig. 11b), signifying the relatively highly crystalline structure of the LAAM GSH-CQDs36.

a A TEM image of LAAM GSH-CQDs. Experiment was independently repeated three times with similar results. b Particle size distribution of LAAM GSH-CQDs obtained from TEM results. c An AC-TEM image of LAAM GSH-CQDs. Experiment was independently repeated three times with similar results. d XPS survey scan spectrum of LAAM GSH-CQDs. e XPS C1s curve-fitting spectrum of LAAM GSH-CQDs. f XPS N1s curve-fitting spectrum of LAAM GSH-CQDs. The black (—) and brown (—) lines represent the experimental and curve-fitted spectra, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum showed the stretching vibrations of C = C (1655 cm−1), C = N (1686 cm−1), C–N (1315 cm−1), O–H (3399 cm−1), C = O (1721 cm−1), N–H (3283 cm−1 and 3186 cm−1), and C–H (2936 cm−1 and 1396 cm−1) bonds (Supplementary Fig. 12), suggesting the possibility of N-doping in the LAAM GSH-CQD core structure and the presence of carboxyl, amino and hydrocarbon structures at the deges of LAAM GSH-CQDs37. Chemical shifts representing aromatic C = C bond38, C = N bond39, carboxyl (O = C–O) group40, CH2 carbons41,42, and C–N bonds43 can be found from the 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum of LAAM GSH-CQDs (Supplementary Fig. 13), demonstrating the presence of carboxyl, CH2 hydrocarbons, amino, and N-doping in the LAAM GSH-CQD structure. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis revealed that the C, O, and N elements were present at 60.7, 20.1, and 19.2 at%, respectively, on the surface of the LAAM GSH-CQDs (Fig. 2d). The C1s spectrum of LAAM GSH-CQDs was curve-fitted into five main components, including the sp2-hybridized (C = C) with a shake-up peak (π–π* shake-up), sp3-hybridized (C–C) carbons attributed to the CH2 structure, carboxyl group (O = C–O), and two types of N-containing groups (C–N and N–C–N) (Fig. 2e). The N1s spectrum contains three components, corresponding to pyridinic N, graphitic N, and an amino group (–NH2) (Fig. 2f). The calculated sp3-hybridized carbon component (10.0 at%) is twice that of the amino component (4.8 at%) (Supplementary Table 1), indicating that the hydrocarbon chains at the edges of the LAAM GSH-GQDs are composed of two CH2 units.

The presence and number of amino acid groups at the edges of the LAAM GSH-CQDs were determined using the ninhydrin reaction. The primary amino acid groups on the edge can react with ninhydrin, forming Ruhemann’s purple with a maximum UV-vis absorption at 570 nm. After incubating the LAAM GSH-CQDs with ninhydrin, an absorption peak appeared at 570 nm (Supplementary Fig. 14a), indicating the presence of α-amino acid groups at the edges of the LAAM GSH-CQDs. A calculation based on the standard curve between the amino acid concentration and the UV-vis absorbance (Supplementary Fig. 14b) shows ~22 amino acid groups at the edges of each LAAM GSH-CQD.

The structure of the LAAM GSH-CQDs was then optimized through energy minimization in geometry optimization. Owing to the steric hindrance and repulsion of two adjacent amino acid groups at the edges, the amino acid groups curved upwards or downwards from the sp3-hybridization carbons bound to the benzene ring with an angle of 104.0o between the CH2 hydrocarbon and the carbon basal plane (Fig. 3a, b). The 22 amino acid groups at the edges are arranged alternately up and down, with 11 amino acid groups in each direction, forming a steric chain amino acid group-rich LAAM GSH-CQD structure. Combined with experimental results and theoretical simulation, it can be concluded that the LAAM GSH-CQDs are composed of N-doped conjugated sp2 carbons with an oval shape 3.2 nm size and surrounded by ~22 sterically chain amino acid groups, with each one including two CH2 hydrocarbons and one α-amino acid group linked to the edges of the carbon basal plane via the sp3-hybridization carbons on the benzene ring, and the two adjacent amino acid groups are individually connected to the adjacent benzene rings and arranged alternately up and down (Fig. 1b). The structure of LAAM GSH-CQDs mimics the structure of conventional amino acids, and owing to their significantly larger size compared to conventional amino acids, the CQD was designated as “large” amino acid-mimicking carbon quantum dots (LAAM CQDs).

a An enlarged view of the optimized LAAM GSH-CQD structure. b The overall view of the optimized LAAM GSH-CQD structure. c An one unit structure of the formation of the hexagonal ring on the surface of LAAM GSH-CQDs. d The whole structure of the formation of the hexagonal ring on the surface of LAAM GSH-CQDs. e An one unit structure of the formation of water hydration layer on the surface of LAAM GSH-CQDs. f The whole structure of the formation of water hydration layer on the surface of LAAM GSH-CQDs.

The formation mechanism of LAAM GSH-CQDs was investigated through electron spin resonance (ESR) experiments. The reaction between GSH and formamide was carried out in the presence of the radical scavenger 2,2,6,6,-tetramethyl-piperidine-N-oxyl (TEMPO). The ESR spectrum of TEMPO showed a triplet signal originating from the interaction of the unpaired electron spin with a nitrogen atom nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 15a)44. A reduction in the TEMPO ESR signals was observed in the presence of GSH and formamide, which was related to the generation of oxidative radicals in the system, mainly from formamide45,46. The characteristic peak of LAAM GSH-CQDs in the PL spectrum disappeared after the reaction of GSH and formamide in the presence of TEMPO (Supplementary Fig. 15b), in which TEMPO reacted with the formed radicals during the reaction process and inhibited the formation of LAAM GSH-CQDs. Thus, the mechanism of LAAM GSH-CQD formation is proposed to be a radical-assisted synthesis process. The GSH precursor is crucial in forming amino acid structures, which serves as a building block to form amino acid chains at the edges of the LAAM GSH-CQDs. The formamide acted as a solvent and a radical initiator in the reaction, which was converted into the carbamoyl radical (•CONH2)47,48. The carbamoyl radical was caught by the carboxyl groups in GSH and transferred to the quaternary C site to form GSH radicals (Fig. 1a)49,50. The GSH radicals underwent carbonation and condensation reactions with the removal of small molecules, such as methanethiol, water, hydrogen, and ammonia, etc. (Fig. 1a), and finally formed the LAAM GSH-CQDs.

Water solubility mechanism of LAAM GSH-CQDs

The mechanism of water solubility of LAAM GSH-CQDs was explored by conducting theoretical investigations between the optimized LAAM GSH-CQD model and water molecules. As shown in Fig. 3c, the hydroxyl and carbonyl groups in the carboxyl group of the amino acid group individually bind to one water molecule through hydrogen bonding, and the amino group of the adjacent amino acid group with the same orientation binds to one water molecule through hydrogen bonding. A hexagonal ring containing one carboxyl group, one amino group, and three water molecules with an average hydrogen bond length of 1.74 Å is formed. This hexagonal ring arrangement extends to other amino acid groups, and thus forms a circle of hexagonal structure above and below the carbon plane of the LAAM GSH-CQDs (Fig. 3d). The formed hexagonal ring can bind to water molecules through hydrogen bonding, inducing water molecules to form a chair-form hexamer structure consisting of six water molecules connected through hydrogen bonding (Fig. 3e, f)51,52. The chair-form hexamer of water finally aligns into a basal face structure at the top and bottom of the LAAM GSH-CQDs through hydrogen bonding between the water molecules, forming a hydration layer. The average hydrogen bond length between water molecules in the chair-form hexamer is 1.52 Å, slightly shorter than that between ordinary water molecules (1.87 Å)53, indicating a stronger hydrogen bond induced by the hexagonal structure. The calculated lattice space of hexagonal-arranged water in the basal face structure was 0.37 nm (Supplementary Fig. 16a). The high affinity between the LAAM GSH-GQDs and water forms a highly hydrated system that imparts the water-soluble properties of LAAM GSH-CQDs.

The cryo-TEM images show the well-dispersed LAAM GSH-CQDs covered by lattice fringes with an interplanar distance of 0.37 nm (Supplementary Figs. 16b and 17), assigned to the lattice structure of hexagonal ice with basal face52, which is consistent with the calculated lattice space of water from the simulation results of LAAM GSH-CQDs with water. In contrast, no obvious lattice structure was found in the cryo-TEM images of pure water (Supplementary Fig. 16c). The 1H NMR results of LAAM GSH-CQDs reflect the formation of hydrogen bonds between water molecules and amino acid groups from the upfield shift of amino group peak and the presence of peaks as a result of carboxyl groups and water molecules as the concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs increases (Supplementary Fig. 18)54,55. A signal representing the presence of water with a strong hydrogen-bonding structure also appeared and increased as the concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs increased, which originated from the ordered arrangement of water molecules with restricted mobility around the LAAM GSH-CQDs. The viscosity of water in the presence of LAAM GSH-CQDs was determined to be ~0.93 mPa s at concentrations below 10 mg mL−1 and gradually increased to 1.16 mPa s at higher concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 19). The increased viscosity compared to pure water originates from the intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the water molecules and LAAM GSH-CQDs56,57. The interaction between water molecules and LAAM GSH-CQDs confines the movement of water molecules, which creates fewer neighboring water molecules available for hydrogen bonding, resulting in higher viscosity values. The number of confined water molecules increased as the concentration increased, leading to a continuous increase in viscosity. The dielectric constant of water was measured to be 74.4 at a frequency of 2.7 × 106 Hz, and the presence of LAAM GSH-CQDs led to a decrease in the water dielectric constant. As the concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs increased from 0.01 – 50 mg mL−1, the corresponding dielectric constant of water gradually decreased to 45.2 (Supplementary Fig. 20). The formation of a structured arrangement of water in the presence of LAAM GSH-CQDs restricts the rotational freedom of the water dipoles, leading to a decrease in the water dielectric constant58,59. The calculated dielectric constant for water connected to LAAM GSH-CQDs through hydrogen bonds is 39.2, close to the measured dielectric constant of 45.2 for water in the presence of LAAM GSH-CQDs. The similarity between the theoretical and experimental results proved the rationality of the simulation approach.

The hydration layer of the LAAM GSH-CQDs can be dehydrated by adding dehydrating agents, such as acetone and ethanol. Acetone was added to the LAAM GSH-CQD water solution. Under these conditions, adding electrolytes such as NaCl and NaNO3 can cause coagulation of the LAAM GSH-CQDs (Supplementary Fig. 21). A similar phenomenon was observed after adding ethanol to the LAAM GSH-CQD water solution. The hydration layer of the LAAM GSH-CQDs can also be destroyed by decreasing the number of amino acid groups at the edges because the circle of the hexagonal structure formed between the amino acid group and water molecules is disturbed. The effect of the number of amino acid groups on the water-soluble properties of LAAM GSH-CQDs was then studied by reacting the LAAM GSH-CQDs with silver ions (Ag+). The amino group and the carbonyl of the carboxyl group in an amino acid group can react with one Ag+ ion through coordination interactions to form a dicoordinate complex60, which disturbs the structure of the amino acid-water hexagon ring structure. As the Ag+ ion concentration increases, more amino acid groups are consumed, and the number of hydrogen bonds formed between amino acid groups and water is thus reduced, accompanied by the destruction of the hydration layer and a decrease in the water solubility of LAAM GSH-CQDs, which can be reflected in the PL intensity change of LAAM GSH-CQDs with different numbers of amino acid group (Supplementary Fig. 22a). As the number of amino acid group decreased, the water solubility decreased, leading to aggregation of the LAAM GSH-CQDs. The concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs remaining in the supernatant decreased as the number of amino acid group decreased, resulting in a reduction in the PL intensity of the LAAM GSH-CQDs. As the number of amino acid group decreased to approximately zero, most of the LAAM GSH-CQDs were converted into precipitation, and the PL intensity was close to zero. Accordingly, the precipitation rate of pristine LAAM GSH-CQDs was approximately zero, and this value gradually increased as the number of amino acid group decreased (Supplementary Fig. 22b). When the number of amino acid group decreased to near zero, this rate exceeded 90%.

In vitro and in vivo toxicity assessment of LAAM GSH-CQDs

The formation of the protein corona was monitored by sodiumdodecyl-sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After incubation with FBS, LAAM GSH-CQDs were collected through centrifugation and then extensively washed. Control nanomaterials, including commercial liposomes (Lipofectamine 2000, Lipo 2000) and GO-CQDs dispersed in water through electrostatic repulsion, received the same treatment. All the nanomaterials, together with FBS, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4a). FBS showed typical bands at ~66–69 kDa, representing albumin; and at 50-70 kDa, representing the heavy chain of immunoglobulin G, A, and M (IgG, IgA, and IgM)61,62. Similar bands were found in both control groups. In comparison, no significant bands were found in the LAAM GSH-CQD group, suggesting negligible protein absorption. Further western blot (WB) analysis confirmed that unlike control nanomaterials, LAAM GSH-CQDs had minimal absorption of each individual protein, including albumin, IgG, IgA, and IgM (Supplementary Fig. 23). The phenomena are attributed to the interaction between the two nanomaterials and the proteins, leading to the formation of protein corona. Particularly, the interactions between Lipo 2000 or GO-CQDs and immunoglobulins can cause immunogenicity, which could cause the recognition and clearance by MPS cells after in vivo injection. The negligible stickiness of LAAM GSH-CQDs towards proteins can prevent the formation of protein corona and immunogenicity, similar as the stealth effect, having high biosafety and bioavailability.

a SDS-PAGE analyses of FBS and proteins absorbed to the surface of LAAM GSH-CQDs, Lipo 2000 or GO-CQDs after incubation with FBS, along with the densitometric analysis of the SDS-PAGE result. b Expression levels of typical inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) in Kunming mice after vein injection of LAAM GSH-CQDs at an accumulated dose of 15 mg kg−1. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD, n = 3 mice). Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. ns: not significant. c The hemolysis assay of LAAM GSH-CQDs with different concentrations (1, 3, and 5 mg mL−1) using mouse or human blood. PBS and Triton X-100 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). d Cell viability of A549 and HeLa cells incubated with different concentrations of LAAM GSH-CQDs for 24 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). e The body weight changes of Kunming mice after single-dose (5000 mg kg−1, acute toxicity group) and accumulated dose (3500 mg kg−1, cumulative toxicity group) vein injection of LAAM GSH-CQDs, and photos of Kunming mice after corresponding treatments. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 mice). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The concentration of inflammatory cytokines was then measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to investigate the immunogenicity. Kunming mice were injected with 5 mg kg−1 LAAM GSH-CQDs for every 2 days, with an accumulated dose of 15 mg kg−1. After 1 week tests in mice, mouse whole blood was collected and typical inflammatory cytokines were detected. The results, as presented in Fig. 4b, show that, compared to the control group, there were no significant changes in the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. These findings confirm the minimal immunogenicity of LAAM GSH-CQDs.

We then investigated the relationship between water solubility and protein corona formation. LAAM GSH-CQDs with different numbers of amino acid group coordinated with the Ag+ ion were used to analyze the effect of water solubility on the formation of the protein corona. The intensity of the UV-vis absorption peak at 420 nm of the LAAM GSH-CQDs did not change before and after the addition of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Supplementary Fig. 24), indicating a negligible interaction between the LAAM GSH-CQDs and BSA. The peak intensity gradually decreased as the number of amino acid group at the edges of the LAAM GSH-CQDs decreased. The results revealed that LAAM GSH-CQDs do not form a protein corona upon contact with the protein, while the protein corona can be formed as the water solubility of LAAM GSH-CQDs decreases by reducing the number of amino acid group at the edges.

Hemolysis assay evaluated blood compatibility by identifying severe acute toxic reactions in red blood cells (RBCs) in vivo63,64. Triton X-100 was used as a positive control, which showed a hemolysis rate of >80% in mouse whole blood. As a comparison, only ~1% hemolysis was observed upon treatment of mouse whole blood with LAAM GSH-CQDs at a concentration up to 5 mg mL−1, which was close to the value of 0.5% for PBS as the negative control group (Fig. 4c). To further verify the blood compatibility, hemolysis assay using human whole blood was carried out. Similarly, Triton X-100 exhibited a hemolysis rate of near to 70%. Treating the human blood with LAAM GSH-CQDs at various concentrations did not cause much changes, showing a hemolysis rate <2% (Fig. 4c). The results confirm that LAAM GSH-CQDs have excellent hemocompatibility.

Cytotoxicity was evaluated in A549 and HeLa cells using an MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay. The cytotoxicity evaluation showed cell viability >90% at an incubation LAAM GSH-CQD concentration of up to 1000 μg mL−1 for 24 h (Fig. 4d). The Kunming mouse acute toxicity test was conducted by intravenous administration of LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose of 5000 mg kg−1 on day 0 and observed for 2 weeks. In the cumulative toxicity test, Kunming mice were injected with 500 mg kg−1 LAAM GSH-CQDs on days 0, 4, and 7, respectively, and the dose was increased to 1000 mg kg−1 on days 10 and 13, with an accumulated dose of 3500 mg kg−1. No obvious changes in body weight or tissue damage were observed during the 2 week observation (Fig. 4e). After 2 week acute toxicity and cumulative tests in mice, no statistical difference existed between LAAM GSH-CQD group and normal control group in the parameters from complete blood count and serum biochemistry analyses (Supplementary Fig. 25). For comparison, Kunming mice died within 1 h after intravenous administration of Lipo 2000 and GO-CQDs at doses of 12 and 16 mg kg−1, respectively. The water-soluble properties of the LAAM GSH-CQDs protect them from protein adsorption, hemolytic activity, and endow them negligible immunogenicity and low in vitro and in vivo toxicity, which is suitable for using as a safety platform for further biological applications.

In vitro and in vivo tumor-targeting of LAAM GSH-CQDs

The tumor-selectively targeting properties of LAAM GSH-CQDs were first investigated using a combination of laser confocal scanning microscopy and flow cytometry. It was found that the LAAM GSH-CQDs penetrated tumor cells, such as A549 and HeLa cells, and were mainly located in the cytoplasm, showing red fluorescence (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 26). However, nearly no red fluorescence signal could be detected after the LAAM GSH-CQDs were incubated with normal cells, such as HEK-293T and HUVEC cells, indicating the limited ability of LAAM GSH-CQDs to penetrate normal cells. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the fluorescence intensity of LAAM GSH-CQDs incubated with tumor cells was ~104, ten times higher than normal cells on the order of 103 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 27). The calculated uptake rate of LAAM GSH-CQDs from flow cytometry results revealed that most tumor cells had an uptake rate of up to 99%, whereas the average rate for normal cells was close to 10% (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28).

a Confocal fluorescence images of A549 and HEK-293T cells after incubation with LAAM GSH-CQDs. b Flow cytometry analysis of A549 and HEK-293T cells after incubation with LAAM GSH-CQDs. c Quantifying cellular uptake rate in tumor and normal cells from the flow cytometry analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 7 cell lines). d Fluorescence images of a nude mouse bearing a HeLa tumor that received vein injection of LAAM GSH-CQDs at different time points (n = 3 mice). e Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of major organs and tumor from a nude mouse bearing a HeLa tumor after vein injection of LAAM GSH-CQDs at 5 h post-injection (n = 3 mice). f The semiquantitative biodistribution of LAAM GSH-CQDs in HeLa tumor-bearing mice after vein injection of LAAM GSH-CQDs at 5 h post-injection determined by the averaged fluorescence intensity of major organs and tumor. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 mice). g Kinetics of LAAM GSH-CQDs uptake in HeLa cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). h WB analysis of LAT1 protein changes on whole cell, cell membrane, and cell cytoplasm of HeLa cells after incubation with LAAM GSH-CQDs for different times (n = 3 biological replicates). The sample processing or loading control corresponds to the top or bottom panel. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then assessed whether LAAM GSH-CQDs maintained high tumor specificity in vivo. LAAM GSH-CQDs were injected intravenously into nude mice bearing HeLa tumors at a dose of 5 mg kg−1. As shown in Fig. 5d, the fluorescence signal began to accumulate in the tumor region at 1 h and gradually increased over time. The LAAM GSH-CQDs reached the best accumulation in the tumor region at 5 h. They could still be detected over time until 24 h after injection (Fig. 5d), implying long-term enrichment of LAAM GSH-CQDs in tumors. The ex vivo fluorescence imaging of organs and the tumor taken from 5 h post-injection similarly showed that the intensity of the fluorescence signal of the tumor was more than ten times higher than that of other organs, such as the liver and kidney (Fig. 5e, f). We further investigated the biodistribution of LAAM GSH-CQDs using the nude mouse model by intravenously injected into nude mice at a dose of 10 mg kg−1. After 2 h post-injection, we did not detect significant accumulation of LAAM GSH-CQDs in major organs of mice from both in vivo and ex vivo fluorescence imaging (Supplementary Fig. 29a). Immunofluorescent detection did not detect significant accumulation of LAAM GSH-CQDs in the brain (Supplementary Fig. 29b). These results suggest that, despite the expression of LAT1 on the blood-brain barrier (BBB), LAAM GSH-CQDs do not accumulate in the brain without tumors.

Time-dependent fluorescence monitoring of LAAM GSH-CQDs incubated with HeLa cells showed that intracellular fluorescence increased over time for the first 4 h, after which no further significant increase was observed, and the corresponding uptake rate also reached ~99% at 4 h (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 30). We further monitored the intracellular location of LAAM GSH-CQDs over time after incubation with HeLa cells. The findings revealed that the majority of LAAM GSH-CQDs localized on the cell membrane after 1 h and subsequently internalized into the cell. After 4 h of incubation, the concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs in the cell increased significantly and maintained high fluorescence intensity until the 12-h time point (Supplementary Fig. 31). The increased number of amino acid groups on the LAAM GSH-CQDs enhances the tumor-targeting efficiency compared to the LAAM TC-CQDs, which have 8 α-amino acid groups. The LAAM GSH-CQDs exhibited a shorter tumor cell uptake time from time-dependent intracellular fluorescence experiments (4 and 6 h for LAAM GSH-CQDs and LAAM TC-CQDs, respectively) and shorter tumor accumulation time from in vivo fluorescence imaging experiments (5 and 8 h for LAAM GSH-CQDs and LAAM TC-CQDs, respectively).

We then investigated the mechanism by which LAAM GSH-CQDs penetrate tumor cells through interaction with LAT1. Consistent with previous reports, the expression level of LAT1 in tumor cells was higher than that in normal cells, and the LAT1 expression level correlated with the amount of LAAM GSH-CQDs that penetrated cells in various cell lines4. Moreover, we performed WB analysis on tumor and various organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, and found that the expression level of LAT1 in the tumor was significantly higher than in other tissues, such as the liver and kidney (Supplementary Fig. 32). Further immunofluorescence assay of the tumor-targeting effect of LAAM GSH-CQDs revealed that the accumulation of CQDs correlated with LAT1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 33). Collectively, these findings support that the targeting ability (binding specificity) of LAAM GSH-CQDs depends on LAT1 expression.

Docking analysis was performed to simulate the interaction between LAAM GSH-CQDs and LAT1. By using LAT1-4F2hc as the model, we found that the LAAM GSH-CQDs could bind to the LAT1 mainly through hydrogen bonds formed between the amino acid groups on LAAM GSH-CQDs and the Glu457, Glu78, Asn242 and Leu238 residues in LAT1 with a docking energy of –8.80 kcal mol−1 (Supplementary Fig. 34a). Further, LAT1-dependent binding affinity was measured and calculated with or without the presence of the LAT1 inhibitor, 2-aminobicyclo-(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH). The Michaelis constant Km reflecting the binding affinity between LAAM GSH-CQDs and LAT1 was determined to be 0.56 μM (Supplementary Fig. 34b). The docking energy between LAT1 and LAAM GSH-CQDs was four times lower than that of LAAM TC-CQDs, and the binding affinity between LAT1 and LAAM GSH-CQDs was nearly three times higher than that of LAAM TC-CQDs, which is the inverse ratio of the measured Km. It was concluded that increasing the number of amino acid groups at the edges of the LAAM CQD makes it easier to bind with LAT1, together with the overexpression of LAT1 in tumor cells, resulting in higher tumor selectivity.

The internalization of LAAM GSH-CQDs was evaluated in the presence of different inhibitors, including BCH, chlorpromazine (Chl), and genistein (Gen), which function as a LAT1 inhibitor, clathrin- and caveolin-dependent endocytosis inhibitors, respectively. It was found that both BCH and Chl inhibited the uptake of LAAM GSH-CQDs by ~80%, whereas the uptake rate of LAAM GSH-CQDs was almost unchanged in the presence of Gen (Supplementary Fig. 34c), suggesting that the internalization of LAAM GSH-CQDs is carried out by LAT1-dependent endocytosis mediated by clathrin. The kinetics of the time-dependent uptake of LAAM GSH-CQDs implies the ongoing endocytosis of LAAM GSH-CQDs while binding to LAT1 (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 30)65.

WB analysis was used to further investigate the role of LAT1 in the transport of LAAM GSH-CQDs into tumor cells. HeLa cells were incubated with LAAM GSH-CQDs for different durations, and the total LAT1 and LAT1 on the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm were analyzed. The total LAT1 protein did not show significant changes after incubation with LAAM GSH-CQDs at different times (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. 35). However, the expression of LAT1 on the cell membrane gradually decreased as the incubation time increased to 3 h and then significantly increased when the incubation time increased to 5 h. In contrast, an opposite trend of LAT1 expression levels was found in the changes in the cell cytoplasm. After adding BCH and incubating with LAAM GSH-CQDs, both the expression level of LAT1 on the cell membrane and in the cell cytoplasm did not show significant changes at various incubation times (Supplementary Fig. 35). This result confirms that LAT1 first participates in the internalization of LAAM GSH-CQDs from the cell membrane into the cytoplasm, decreasing LAT1 expression on the cell membrane. After releasing the LAAM GSH-CQDs into the cell cytoplasm, LAT1 is recycled back to the cell membrane, contributing to the increase in LAT1 level on the cell membrane. The mechanism of LAAM GSH-CQD internalization into tumor cells was proposed to be a LAT1-dependent clathrin-mediated endocytosis process (Supplementary Fig. 36). The results confirm that LAAM GSH-CQDs retain the LAT1-based tumor-targeting capability, which specifically targeting tumor cells but rarely penetrates normal cells.

LAAM GSH-CQDs for DOX delivery

The large π-conjugated structure of the LAAM GSH-CQDs can load aromatic drugs, such as DOX, through π–π stacking interactions. The successful loading of DOX through π–π stacking interactions was confirmed by the redshift and broadening of the characteristic UV-vis absorbance peak of LAAM GSH-CQDs from 604, 627, and 676 to 609, 635, and 687 nm, respectively, forming the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD complex (Supplementary Fig. 37)66. The TEM image shows well-dispersed and uniform DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs (Supplementary Fig. 38a). After storing the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD powder at 25 °C protected from light for 10 months, the morphology and size distribution of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs obtained from TEM images were found to be the same as those of the freshly prepared samples (Supplementary Fig. 38b). The DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs remained stable without precipitation after storage at 4 °C in a dispersion medium of water, PBS, and FBS (Supplementary Fig. 39). The data verify the uniformity and stability of the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs preserved from the LAAM GSH-CQDs.

The selective tumor targeting of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs was investigated by intravenously injecting free DOX and DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 5 mg kg−1 DOX into Kunming mice bearing HeLa tumors and acquiring tissue distribution images. At 7 h post-injection, the DOX fluorescence intensity of the tumor in DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs was approximately three times than that of the free DOX (Fig. 6a, b). A biodistribution study revealed that the accumulation of DOX in tumors was over twice as high in the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD group compared to any other organs, whereas free DOX was mainly distributed in the liver, and the fluorescence intensity of the tumor was only half that of the liver at this time point (Fig. 6a, b). The DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs accumulated in the tumor within 30 min and lasted for 24 h, and the fluorescence intensities in the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs were two to three times higher than those found for free DOX in the tumors (Supplementary Fig. 40). The results confirm the tumor targeting property of the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs preserved from the LAAM GSH-CQDs.

a Fluorescence imaging acquired from the DOX biodistribution in Kunming mice bearing HeLa tumors of major organs and tumor at 7 h post injection of DOX or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs. b Fluorescence intensity determined from the DOX biodistribution in Kunming mice bearing HeLa tumors of major organs and tumor at 7 h post injection of DOX or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 mice). Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. c Representative photos of A549-tumor-bearing nude mice after receiving the DOX, Doxil or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 6 mg kg−1 DOX, DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 2 mg kg−1 DOX treatments, saline, and LAAM GSH-CQDs. d Changes in tumor volume over time of A549-tumor-bearing nude mice after receiving the DOX, Doxil or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 6 mg kg−1 DOX, DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 2 mg kg−1 DOX treatments, saline, and LAAM GSH-CQDs. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 mice). Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. e Histological evaluation of tumor and major organs from A549-tumor-bearing nude mice after different treatments. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We assessed the in vitro activity of the LAAM GSH-CQDs as drug carriers for the delivery of DOX. The killing effects of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs treatment on A549 cell were higher than that of free DOX at the DOX concentration ranging from 0.125 to 10 μg mL−1 (Supplementary Fig. 41a). However, when treated to normal cells, free DOX could kill about 90% of cells at a concentration of 10 μg mL−1, while the cell viability remained >80% after DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD treatment (Supplementary Fig. 41b). The tumor-targeting ability of LAAM GSH-CQDs, which selectively penetrate tumor cells but rarely penetrate normal cells, results in a higher DOX concentration in tumor cells with enhanced cell toxicity and reduced toxicity to normal cells.

The treatment effect of the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs on A549 tumors was evaluated. The mice were randomly grouped and received intravenous injections of DOX (6 mg kg−1), Doxil (at a dose equivalent to 6 mg kg−1 DOX), DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs (at a dose equivalent to 2 and 6 mg kg−1 DOX), saline, and LAAM GSH-CQDs on days 0, 4, 8, and 12. The 6 mg kg−1 DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD group showed the most efficient tumor growth inhibition with a 1.39-fold increase in relative tumor volume within 14 days, whereas the tumors in the DOX, Doxil, saline, and LAAM GSH-CQD groups increased by 3.34, 3.32, 3.68 and 4.24 times, respectively (Fig. 6c, d and Supplementary Fig. 42a). It is worth noting that the tumors only increased by 2.76 times even using the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at 2 mg kg−1, which still showed a better treatment effect than the DOX and Doxil groups. There were no obvious changes in the body weights of mice in the two DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD groups (Supplementary Fig. 42b); however, the body weights of mice in the DOX and Doxil groups decreased by ~20% after 14 day treatment. The parameters from the complete blood count and serum biochemistry analyses of mice in the DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD groups were within the normal ranges (Supplementary Fig. 43). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of major organs isolated from mice receiving DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs (6 mg kg−1) treatment did not detect inflammatory infiltration or pathological damage (Fig. 6e), suggesting the low toxicity of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs to normal organs. However, apparent injury of normal organs could be observed in mice that were treated with free DOX (Supplementary Fig. 44a). To further investigate the antitumor efficacy of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs, tumors were analyzed utilizing H&E staining. No obvious histological damages could be observed in the saline group, whereas, the tumor slice of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD-treated mice exhibited nuclear shrinkage and disappearance area, indicating a higher treatment effect on tumors. We also performed the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining of tumors and hearts from the DOX and DOX/LAAM GSH-CQD groups. We observed significantly more cell death in tumors in the group treated with DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs compared to the group treated with free DOX (Supplementary Fig. 44b). Conversely, treatment with free DOX resulted in significant cell death in normal organs, particularly the heart, while the toxicity of DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs was minimal (Supplementary Fig. 44b). The above results indicate that treatment with DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs achieves three times efficacy with lower toxicity than DOX and Doxil.

Discussion

In this study, we report the synthesis of water-soluble LAAM GSH-CQDs at the gram-scale through a solvent washing procedure. The LAAM GSH-CQDs are composed of N-doped conjugated sp2 carbons with a size of about 3.2 nm, surrounded by ~22 sterically hindered amino acid groups arranged alternately up and down at the edges. Compared to LAAM TC-CQDs4, which we recently reported, or other typical nanomaterials dispersed in water through electrostatic repulsive interactions, such as classical Lipo 2000 and GO-CQDs25, LAAM GSH-CQDs have several major advantages.

First, LAAM GSH-CQDs exhibit greater solubility and stability. They can dissolve in water at concentrations up to 2.0 g mL−1 and remain highly stable under various conditions (Fig. 1e). In contrast, LAAM TC-CQDs have water solubility in the milligram range and precipitate when heated to 100 °C or when electrolytes such as NaCl and Na2SO4 are added (Supplementary Fig. 45). Similarly, classical liposomes and GO-CQDs are also unstable in aqueous solution and quickly precipitate after centrifugation, heating, or electrolyte addition (Supplementary Fig. 3). This improvement in solubility and stability of LAAM GSH-CQDs can be attributed to their chemical structure, which includes ~22 amino acid groups with steric chain structures at the edges of each CQD, compared to only 8 α-amino acid groups in LAAM TC-CQDs. The higher number of amino acid groups and the unique steric chain structure allow LAAM GSH-CQDs to interact more effectively with water molecules via hydrogen bonding, creating a hexagonal arrangement and resulting in chair-form hexamer hydration layers, leading to improved solubility and stability.

Second, LAAM GSH-CQDs have a superior safety profile. In vitro evaluation in cell culture showed that over 90% of cells survived after treatment with LAAM GSH-CQDs at a concentration of 1000 μg mL−1 (Fig. 4d). In comparison, ~50% of cells died after incubation with LAAM TC-CQDs at a concentration of 100 μg mL−1 (Supplementary Fig. 46). In vivo evaluation demonstrated that mice tolerated LAAM GSH-CQDs at doses up to 5000 mg kg−1, compared to 18 mg kg−1 for LAAM TC-CQDs, 12 mg kg−1 for Lipo 2000, and 16 mg kg−1 for GO-CQDs. LAAM GSH-CQDs exhibited minimal interaction with serum proteins, extended circulation time, excellent hemocompatibility, and minimal immunogenicity (Fig. 4a-c).

Third, LAAM GSH-CQDs possess greater tumor-targeting ability. Compared to LAAM TC-CQDs, LAAM GSH-CQDs accumulate in tumors with higher efficiency and tumor-to-normal tissue ratios (Fig. 5d-f). This increased tumor-targeting ability may be attributed to the significantly higher number of amino acid groups at the edges of LAAM GSH-CQDs, resulting in 3-4 times greater binding affinity with LAT1 compared to LAAM TC-CQDs (Supplementary Fig. 34).

Fourth, LAAM GSH-CQDs are more suitable carriers for targeted delivery of chemotherapy drugs for cancer treatment. Their large π-conjugated structure enables the loading of aromatic drugs through π–π stacking interactions. Loading chemotherapeutic drugs, such as DOX and topotecan (TPTC), did not alter the high-water solubility and tumor-targeting ability of LAAM GSH-CQDs. DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs were uniform and stable, demonstrating greater tumor-suppressing effects with significantly reduced side effects compared to free DOX and Doxil (Fig. 6d). Direct comparison of LAAM GSH-CQDs and LAAM TC-CQDs with the same payload, TPTC, showed that treatment with TPTC/LAAM GSH-CQDs reduced tumor volumes to undetectable levels by day 14 (Supplementary Fig. 47). The observed anti-tumor effects were comparable to those achieved by TPTC/LAAM TC-CQDs.

Owing to their unique advantages in high solubility and stability, safety profile, tumor-targeting ability, and suitability as drug carriers, LAAM GSH-CQDs have the potential for translation into clinical applications for tumor-targeted imaging and drug delivery.

Methods

Ethics statement

The research described in this manuscript is compliant with all the relevant ethical regulations regarding animal research. The mice experiments were approved by the animal ethic and animal welfare committee of College of Chemistry, Beijing Normal University (No. BNUCC-EAW-2020-0928-01). Female Kunming mice and BALB/c nude mice were used in this study. According to the requirements of the animal ethics committee, the maximal tumor volume allowed was 2000 mm3 and the maximal tumor size in this study was not exceeded. Human blood (female) used in this study was approved by the ethics committees of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences (No. SB2024046), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, and written informed consents were acquired from all patients. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Synthesis of LAAM GSH-CQDs

LAAM GSH-CQDs were synthesized using a solvothermal method. Briefly, L-glutathione (reduced) (GSH, 8.0 g; 98%, Innochem) was mixed with 200 mL of formamide (AR, 99%, Aladdin) under ultrasonication to form a homogeneous solution, which was transferred to a poly(tetrafluoroethylene)-lined autoclave (500 mL), and it was then equipped into the reactor. After heating at 130 °C for 6 h and cooling down to room temperature, a dark green solution was obtained. The solution was first precipitated using methanol (AR, ≥99.5%, Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd.)-dichloromethane (AR, ≥99.5%, Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd.) with a volume ratio of 1:10:25 to obtain dark green powder with the removal of formamide. The powder was then washed with methanol-dichloromethane (from 1:4 to 1:2 in volume ratio) as the eluent through vacuum filtration for further purification. The obtained dark green powder was dried in an oven and then washed with water through vacuum filtration to collect the green solution. The solution was dried in an oven at 70 °C to obtain LAAM GSH-CQDs in powder form. The solubility was measured by adding a known mass of the LAAM GSH-CQDs and adding a certain volume of PBS or deionized water at 25 °C, followed by vigorously shaking for 30 s every 5 min, and the dissolution was observed within 30 min.

Computational methods

Materials Studio 2019 (v19.1.0.2353) was used for simulation the structure of LAAM GSH-CQDs. The Forcite module was used for geometry optimization of the structure of LAAM GSH-CQDs. The DMol3 module was used for optimization of the one unit structure of LAAM GSH-CQDs with water molecules. The Forcite module was used for optimization of the whole structure of LAAM GSH-CQDs with water molecules. A protein molecule model (Protein data bank code: 6irs) was applied and the AutoDock 4.2 software was used for molecular docking. The docking simulations were carried out using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm with the default docking parameter. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (v2.3.0) was used for analysis of docking results.

Protein adsorption experiments

1 mg mL−1 of LAAM GSH-CQDs, commercial Lipo 2000 reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), and GO-CQDs prepared from heating the citric acid powder were mixed with 20 times diluted FBS in a volume ratio of 1:1, followed by vortexing for 30 s and incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Free protein and nanomaterials adsorbed with proteins were separated by centrifugation at 10000 × g for 10 min, and the isolated proteins adsorbed on nanomaterials were used for SDS-PAGE. Then, 5× protein loading buffer containing DTT was added to the mixture and vortexed for 30 s to mix well, and it was heated at 100 °C for 5 min. The 8% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE separating gel was used. The electrophoresis was run at 70 V for stacking gel, and 120 V for separating gel. After electrophoresis, the Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 was used to stain the gel for 1 h, after which it was decolorized with eluent overnight.

Hemolysis assay

Mouse blood was obtained from Kunming mice (4–6 weeks, female), and female human blood was used. Mouse or human RBCs were isolated from mouse or human whole blood by centrifugation. After washing with PBS, the RBC suspension was added to LAAM GSH-CQDs in PBS with a concentration of 1, 3, or 5 mg mL−1. RBCs incubated with PBS and Triton X-100 (0.5%) were used as negative and positive control, respectively. The samples were mixed by vortexing and left to stand for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged and the supernatants were collected and transferred to a 96-well plate. Van Kampen-Zijlstra’s reagent was then added before measuring the absorbance of the supernatants at 540 nm using a microplate reader. Due to the background absorbance of LAAM GSH-CQDs with different concentrations, the percentage of hemolysis was calculated as following: hemolysis% = (Asample – Abackground)/(Apositive - Anegative) × 100%, where the absorbance of negative and positive samples indicates the absorbance of the PBS and the water samples, respectively.

WB Analyses

The LAT1 (11326-1-AP, 1:1000), albumin (16475-1-AP, 1:25,000), IgG (10284-1-AP, 1:15,000), IgA (60099-1-Ig, 1:25,000), and IgM (11016-1-AP, 1:4000) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech. For whole cell and tissue samples, samples were first lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with a cocktail of protease. Samples were then centrifuged at 12000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and transferred to a new centrifuge tube. For extraction of proteins on cell membrane cell cytoplasm, cell samples were pretreated using a membrane and cytosol protein extraction kit (Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the protocol from manufacture. For protein adsorption measurement, the isolated proteins adsorbed on nanomaterials were used. The protein concentrations of extracted protein samples were measured. Next, samples were mixed with 5× loading buffer and heated at 100 °C for 10 min. Proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE and then transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The 5% BSA was used to block the samples for 1.5 h at room temperature. Then, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, followed by washing with Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST). The membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The secondary antibodies were Goat-Anti-Mouse IgG-HRP (Abcam, ab205719, 1:10,000) for IgA, and Goat-Anti-Rabbit IgG-HRP (Abcam, ab6721, 1:15,000) for LAT1, albumin, IgG, and IgM. The membranes were visualized with an electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, USA). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Zen BioScience, 200306-7E4, 1:10,000) was used as an internal control for albumin, IgG, IgA, IgM, and LAT1 in whole cell, cell cytoplasm and tissue samples. The cadherin antibody (Proteintech, 20874-1-AP, 1:50000) was chosen as the internal control for LAT1 on the cell membrane.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cells were plated into a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells per well and incubated in a cell incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). The cells were then treated with LAAM GSH-CQDs, DOX, or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at different concentrations. MTT assay was used to assess cytotoxicity. After 24 h, 10 μL of MTT was added to the well and incubated for 4 h. The cultured medium was then removed, and 100 μL of DMSO was added. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Epoch, BioTek, US).

Flow cytometry

Cells, at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well, were plated into a 6-well plate and incubated in a cell incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) until reaching 80–90% confluence, and the concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs was 10 μg mL−1. In the LAT1 inhibition experiments, cells were pretreated with BCH at 5 mM for 2 h, and then incubated with LAAM GSH-CQDs. After incubation with cells overnight, the culture medium was removed and washed with PBS three times. Cells were detached using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, collected by centrifugation at a speed of 1000 × g for 5 min, and resuspended in PBS. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using flow cytometry (FACSDiva, Becton Dickinson, US). About 10000 cells per tube were recorded for each analysis. Data were analyzed using CytExpert (v2.3).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy imaging

Cells were plated into a confocal petri dish and incubated in a cell incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2), and the concentration of LAAM GSH-CQDs was 20 μg mL−1. After incubation with cells overnight, the culture medium was removed and washed with PBS three times. The cells were then fixed with frozen methanol for 15 min at 4 °C and washed with PBS three times, followed by the addition of DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Beyotime Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) for cell nuclei staining. The cells were washed with PBS three times. Finally, PBS was added, and images were taken with a confocal fluorescence microscope (LEICA STP6000, Leica, Germany). NIS Elements (v5.21.00) was used for cell confocal laser scanning microscopy imaging.

In vivo fluorescence imaging

BALB/c female HeLa tumor-bearing nude mice (4–6 weeks) were bought from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. (Beijing, China). Mice were group-housed on 12 h:12 h light cycle with ambient temperature of 20–26 °C and relative humidity in range of 40–70%. Mice were injected with LAAM GSH-CQDs (5 mg kg−1) via tail vein injection (n = 3). Intravital fluorescence signals (excitation at 620 nm, emission at 670 nm) were collected at various time points (1, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 24 h) post-injection using an in vivo fluorescence imager (IVIS Lumina III, PerkinElmer, US). Five hours after the injection, the tumor-bearing nude mice were euthanized and dissected, and the major organs, including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, and the tumor were dissected. The ex vivo fluorescence signals of the organs and tumor were collected with a live fluorescence imager. Data were analyzed using Living Image (v4.3.1).

Toxicity evaluation in mice

Kunming mice (4–6 weeks, female) purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. (Beijing, China) were used for experiments. Mice were group-housed on 12 h:12 h light cycle with ambient temperature of 20–26 °C and relative humidity in range of 40–70%. The acute toxicity test was carried out by vein injection of LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose of 5000 mg kg−1 on day 0 and observed for 2 weeks (n = 3). In the cumulative toxicity test, the Kunming mice were vein injected with 500 mg kg−1 LAAM GSH-CQDs on days 0, 4, and 7, respectively, and the dose was increased to 1000 mg kg−1 on days 10 and 13 (n = 3). The status and body weights of mice were monitored. Mice were euthanized on the last day of 2 week observation, and blood was collected for complete blood count (TEK-II MINI Auto Hematology Analyzers, TECOM Science Corporation, China) and serum biochemistry (Hitachi 7600 Automatic Biochemistry Analyzer, Hitachi Ltd., Japan) analyses. The serum biochemistry analyses were tested after five times diluted.

Biodistribution in mice

The HeLa-bearing mouse models were established by subcutaneously inoculating 108/mL HeLa cells into female Kunming mice (4–6 weeks). Mice were group-housed on 12 h:12 h light cycle with ambient temperature of 20–26 °C and relative humidity in range of 40–70%. When tumors were increased to ∼100 mm3 in volume, 100 μL of DOX, or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 5 mg kg−1 DOX was injected into the mice veins (n = 3). Mice were euthanized at 0.5, 3, 7, 10, and 24 h post injection. Tumors and major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were isolated. The DOX fluorescence signals (excitation at 520 nm, reception at 620 nm) were collected using a live fluorescence imager.

Therapeutic evaluation in tumor-bearing mice

The A549-bearing mouse models (4–6 weeks, female, Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co.) were established by subcutaneously inoculating 107/mL A549 cells into female BALB/c nude mice. Mice were group-housed on 12 h:12 h light cycle with ambient temperature of 20–26 °C and relative humidity in range of 40–70%. When tumors were increased to ∼100–150 mm3 in volume, the mice were randomly divided into six groups. The mice were intravenously administered with saline, LAAM GSH-CQDs, DOX, Doxil, or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 6 mg kg−1 DOX, or DOX/LAAM GSH-CQDs at a dose equivalent to 2 mg kg−1 DOX on days 0, 4, 8, and 12 (n = 3). Changes in tumor volume and body weight were monitored every 2 days. The tumor volume (V) was calculated according to the equation V = D × d2/2, where D and d are the longest and shortest diameters of the tumor, respectively, and were measured using a Vernier caliper. The relative tumor volume, V/V0, was calculated by dividing the measured tumor volume (V) by the initial tumor volume (V0). Mice were euthanized on the last day of treatment. Blood was collected for complete blood count and serum biochemistry analyses. Tumors and major organs, including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were isolated for pathological section analyses.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected in triplicate and reported as mean and standard deviation ( ± SD). Comparison of two groups was evaluated by the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. One-way ANOVA analysis was carried out to determine the statistical significance of treatment related to survival. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.0.2). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. The full image dataset is available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Vargason, A. M., Anselmo, A. C. & Mitragotri, S. The evolution of commercial drug delivery technologies. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 951–967 (2021).

Mitchell, M. J. et al. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 101–124 (2021).

Beija, M., Salvayre, R., Lauth-de Viguerie, N. & Marty, J.-D. Colloidal systems for drug delivery: from design to therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 30, 485–496 (2012).

Li, S. et al. Targeted tumour theranostics in mice via carbon quantum dots structurally mimicking large amino acids. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 704–716 (2020).

Fakayode, O. J., Tsolekile, N., Songca, S. P. & Oluwafemi, O. S. Applications of functionalized nanomaterials in photodynamic therapy. Biophys. Rev. 10, 49–67 (2018).

Moore, T. L. et al. Nanoparticle colloidal stability in cell culture media and impact on cellular interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6287–6305 (2015).

Ganesh, A. N., Donders, E. N., Shoichet, B. K. & Shoichet, M. S. Colloidal aggregation: from screening nuisance to formulation nuance. Nano Today 19, 188–200 (2018).

Smith, G. N., Finlayson, S. D., Rogers, S. E., Bartlett, P. & Eastoe, J. Electrolyte-induced instability of colloidal dispersions in nonpolar solvents. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4668–4672 (2017).

Hassan, S. A. Computational study of the forces driving aggregation of ultrasmall nanoparticles in biological fluids. ACS Nano 11, 4145–4154 (2017).

Monopoli, M. P., Åberg, C., Salvati, A. & Dawson, K. A. Biomolecular coronas provide the biological identity of nanosized materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 779–786 (2012).

Laage, D., Elsaesser, T. & Hynes, J. T. Water dynamics in the hydration shells of biomolecules. Chem. Rev. 117, 10694–10725 (2017).

Schöttler, S., Landfester, K. & Mailänder, V. Controlling the stealth effect of nanocarriers through understanding the protein corona. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8806–8815 (2016).

Salvati, A. et al. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capabilities when a biomolecule corona adsorbs on the surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 137–143 (2013).

Xiao, Q. et al. The effects of protein corona on in vivo fate of nanocarriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 186, 114356 (2022).

Zhao, Z., Ukidve, A., Krishnan, V. & Mitragotri, S. Effect of physicochemical and surface properties on in vivo fate of drug nanocarriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 143, 3–21 (2019).

Dai, Q., Walkey, C. & Chan, W. C. W. Polyethylene glycol backfilling mitigates the negative impact of the protein corona on nanoparticle cell targeting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5093–5096 (2014).

Moyano, D. F. et al. Fabrication of corona-free nanoparticles with tunable hydrophobicity. ACS Nano 8, 6748–6755 (2014).

Knop, K., Hoogenboom, R., Fischer, D. & Schubert, U. S. Poly(ethylene glycol) in drug delivery: pros and cons as well as potential alternatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6288–6308 (2010).

Suk, J. S., Xu, Q., Kim, N., Hanes, J. & Ensign, L. M. Pegylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 99, 28–51 (2016).

Moosavian, S. A., Bianconi, V., Pirro, M. & Sahebkar, A. Challenges and pitfalls in the development of liposomal delivery systems for cancer therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 69, 337–348 (2021).

Abu Lila, A. S., Kiwada, H. & Ishida, T. The accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon: clinical challenge and approaches to manage. J. Control. Release 172, 38–47 (2013).

Shi, L. et al. Effects of polyethylene glycol on the surface of nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. Nanoscale 13, 10748–10764 (2021).

Pan, L., Sun, S., Zhang, L., Jiang, K. & Lin, H. Near-infrared emissive carbon dots for two-photon fluorescence bioimaging. Nanoscale 8, 17350–17356 (2016).

Ravi, P. V., Subramaniyam, V., Pattabiraman, A. & Pichumani, M. Do amino acid functionalization stratagems on carbonaceous quantum dots imply multiple applications? a comprehensive review. RSC Adv 11, 35028–35045 (2021).

Dong, Y. et al. Blue luminescent graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide prepared by tuning the carbonization degree of citric acid. Carbon 50, 4738–4743 (2012).

Li, D., Müller, M. B., Gilje, S., Kaner, R. B. & Wallace, G. G. Processable aqueous dispersions of graphene nanosheets. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 101–105 (2008).

Liu, M., Wang, S. & Jiang, L. Nature-inspired superwettability systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17036 (2017).

Ðorđević, L., Arcudi, F., Cacioppo, M. & Prato, M. A multifunctional chemical toolbox to engineer carbon dots for biomedical and energy applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 112–130 (2022).

Zheng, B. et al. Ultrafast ammonia-driven, microwave-assisted synthesis of nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots and their optical properties. Nanophotonics 6, 259–267 (2017).

Hernandez, Y. et al. High-yield production of graphene by liquid-phase exfoliation of graphite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 563–568 (2008).

Terrones, M. Sharpening the chemical scissors to unzip carbon nanotubes: crystalline graphene nanoribbons. ACS Nano 4, 1775–1781 (2010).

Pan, D., Zhang, J., Li, Z. & Wu, M. Hydrothermal route for cutting graphene sheets into blue-luminescent graphene quantum dots. Adv. Mater. 22, 734–738 (2010).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Bae, S.-Y. et al. Large-area graphene films by simple solution casting of edge-selectively functionalized graphite. ACS Nano 5, 4974–4980 (2011).

Chen, W. & Yan, L. In situ self-assembly of mild chemical reduction graphene for three-dimensional architectures. Nanoscale 3, 3132–3137 (2011).

Englert, J. M. et al. Scanning-raman-microscopy for the statistical analysis of covalently functionalized graphene. ACS Nano 7, 5472–5482 (2013).

Ding, H., Wei, J.-S. & Xiong, H.-M. Nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon dots with strong blue luminescence. Nanoscale 6, 13817–13823 (2014).

Huang, C. et al. Carbon-doped BN nanosheets for metal-free photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 6, 7698 (2015).

Jürgens, B. et al. Melem (2,5,8-Triamino-tri-s-triazine), an important intermediate during condensation of melamine rings to graphitic carbon nitride: synthesis, structure determination by X-ray powder diffractometry, solid-state NMR, and theoretical studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 10288–10300 (2003).

Hiraga, Y., Chaki, S. & Niwayama, S. 13C NMR spectroscopic studies of the behaviors of carbonyl compounds in various solutions. Tetrahedron Lett. 58, 4677–4681 (2017).

Murakami, M. et al. Solid-state 13C NMR analysis of the crystalline-noncrystalline structure and chain conformation of thermotropic liquid crystalline polyester. Polym. J. 36, 830–840 (2004).

Duan, P. et al. The chemical structure of carbon nanothreads analyzed by advanced solid-state NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7658–7666 (2018).

Hanes, J. W., Keresztes, I. & Begley, T. P. 13C NMR snapshots of the complex reaction coordinate of pyridoxal phosphate synthase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 425–430 (2008).

Krzyminiewski, R., Dobosz, B., Schroeder, G. & Kurczewska, J. ESR as a monitoring method of the interactions between TEMPO-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles and yeast cells. Sci. Rep. 9, 18733 (2019).

Barton, D. H. R., Le Gloahec, V. N. & Smith, J. Study of a new reaction: trapping of peroxyl radicals by TEMPO. Tetrahedron Lett 39, 7483–7486 (1998).

Cooper, D. R., Dimitrijevic, N. M. & Nadeau, J. L. Photosensitization of CdSe/ZnS QDs and reliability of assays for reactive oxygen species production. Nanoscale 2, 114–121 (2010).

Sanabria, M. N. & Andrade, L. H. Microwave irradiation and formamide: a perfect match for ultrafast carbamoylation via radical reactions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 13735–13741 (2021).

Ferus, M. et al. High-energy chemistry of formamide: a simpler way for nucleobase formation. J. Phys. Chem. A 118, 719–736 (2014).

Fiser, B., Jójárt, B., Csizmadia, I. G. & Viskolcz, B. Glutathione-hydroxyl radical interaction: a theoretical study on radical recognition process. PLoS ONE 8, e73652 (2013).

Galano, A. & Alvarez-Idaboy, J. R. Glutathione: mechanism and kinetics of its non-enzymatic defense action against free radicals. RSC Adv. 1, 1763–1771 (2011).

Buch, V., Sandler, P. & Sadlej, J. Simulations of H2O solid, liquid, and clusters, with an emphasis on ferroelectric ordering transition in hexagonal ice. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 8641–8653 (1998).

Slater, B. & Michaelides, A. Surface premelting of water ice. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 172–188 (2019).

Modig, K., Pfrommer, B. G. & Halle, B. Temperature-dependent hydrogen-bond geometry in liquid water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 075502 (2003).

Li, B. et al. Various types of hydrogen bonds, their temperature dependence and water-polymer interaction in hydrated poly(acrylic acid) as revealed by 1H solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Macromolecules 40, 5776–5786 (2007).

Oka, K. et al. Long-lived water clusters in hydrophobic solvents investigated by standard NMR techniques. Sci. Rep. 9, 223 (2019).

Ortiz-Young, D., Chiu, H.-C., Kim, S., Voïtchovsky, K. & Riedo, E. The interplay between apparent viscosity and wettability in nanoconfined water. Nat. Commun. 4, 2482 (2013).

Goertz, M. P., Houston, J. E. & Zhu, X. Y. Hydrophilicity and the viscosity of interfacial water. Langmuir 23, 5491–5497 (2007).

Hahn, M. B. et al. Influence of the compatible solute ectoine on the local water structure: implications for the binding of the protein G5P to DNA. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 15212–15220 (2015).

Fumagalli, L. et al. Anomalously low dielectric constant of confined water. Science 360, 1339–1342 (2018).

Shoeib, T., Siu, K. W. M. & Hopkinson, A. C. Silver ion binding energies of amino acids: use of theory to assess the validity of experimental silver ion basicities obtained from the kinetic method. J. Phys. Chem. A 106, 6121–6128 (2002).

Winzen, S. et al. Complementary analysis of the hard and soft protein corona: sample preparation critically effects corona composition. Nanoscale 7, 2992–3001 (2015).

Prozeller, D., Rosenauer, C., Morsbach, S. & Landfester, K. Immunoglobulins on the surface of differently charged polymer nanoparticles. Biointerphases 15, 031009 (2020).

Phuong, P. T. et al. Effect of hydrophobic groups on antimicrobial and hemolytic activity: developing a predictive tool for ternary antimicrobial polymers. Biomacromolecules 21, 5241–5255 (2020).

Jeong, H. et al. In vitro blood cell viability profiling of polymers used in molecular assembly. Sci. Rep. 7, 9481 (2017).

Poirier, C., van Effenterre, D., Delord, B., Johannes, L. & Roux, D. Specific adsorption of functionalized colloids at the surface of living cells: a quantitative kinetic analysis of the receptor-mediated binding. BBA Biom. 1778, 2450–2457 (2008).

Zhuang, W.-R. et al. Applications of π-π stacking interactions in the design of drug-delivery systems. J. Control. Release 294, 311–326 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22172008, L.F.; 21872010, L.F.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2233300007, Y.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions