Abstract

A wafer-scale metal self-rolled-up membrane platform has been proposed for the design and fabrication of radio-frequency on-chip lumped passive components, which is demonstrated on a commercial 4-inch sapphire batch fabrication line. Compared to the traditional methodology including planar or SiNx based self-rolled-up membrane processing technologies to obtain the most basic passive lumped components, such as inductors and capacitors on the chip, this platform enables more compact three-dimensional construction of the component device structure with higher electrical performance. For demonstration, batches of wafer-scale RF inductors and capacitors are fabricated through precise design based on electromagnetic analysis. Measurement results show that radio-frequency inductor samples obtain inductance of 0.6 nH~3.4 nH and a maximum quality factor of 3.1 ~ 7.3 with the largest inductance density of 2.26\(\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{H}}}}/{{{{\rm{mm}}}}}^{2}\), and a typical RF capacitor sample show capacitance of 0.5 pF with the largest capacitance density of 1528.4 \({{{\rm{pF}}}}/{{{{\rm{mm}}}}}^{2}\). After post electroplating, coper layer thickness of a 1.1 nH inductor is increased to be ~ 2.7 μm from 120 nm with the inner diameter of 80 μm, and the maximum quality factor is significantly increased to 18 @ 1.4 GHz. Standalone inductors can be successfully cut off from a 4-inch sapphire wafer by using laser modification cutting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On-chip passive components, such as inductors and capacitors, principally employed for tuning1, matching2, and filtering3, have been playing crucial roles in radio-frequency (RF) circuits. The commonly used planar spiral inductors usually occupy a large chip area due to the weak mutual inductance between turns, which inevitably introduces serious substrate parasitic effects limiting the maximum operating frequency and the Q factor, especially when the substrate is heavily doped. Over the past few decades, numerous scholars have conducted research focusing on the miniaturization of passive components, exploring aspects such as structure and materials4,5,6, such as three-dimensional (3D) micro-coil achieved by a two-photon stereolithography process using a dual-stage scanning process7, silicon-embedded air-core toroidal inductor for (Micro-Electro-Mechanical System) MEMS applications fabricated by silicon via technology8, a novel multipath cross-over interconnection octagon stacked spiral inductor which is manufactured with the SiGe BiCMOS process9, etc. However, intricate manufacturing processes and high production costs have constrained the further advancement of these methods. For RF capacitors, as the demand for a broader range of capacitance values increases, numerous studies have often focused on the preparation of high dielectric constant filler materials and the series connection of capacitors. Hindered by the influence of planar structures, achieving a significant improvement in magnitude proves challenging, and their application frequencies typically lie below the millimeter wave range10,11.

Recently developed plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) SiNx SRuM technology offers a seamless breakthrough of these limitations achieving intricately compact micrometer-scale structures through an exceptionally straightforward process. This not only facilitates miniaturization but also enhances the electrical performance of high-end component devices. The diverse range of flexible film materials for rolling enriches its application fields extensively12,13,14,15,16. In the miniaturization of passive components, their unique structures endow them with remarkably low parasitic effects and substrate losses. Even when aiming for higher inductance or capacitance, the footprint experiences only marginal increases. The notable advantages of low cost and high yield make their commercialization highly feasible.

However, the biggest challenge of using PECVD SiNx SRuM technology to fabricate high-performance on-chip components is that the thicker the metal strip is, the more difficult the rolling becomes17,18. The maximum report stress difference of the SiNx bilayer was 1574.95 MPa (Low Frequency: −1168MPa; High Frequency: 406.95 MPa), which allows up to 225 nm copper (Cu) strip to be rolled up, resulting in a 200\(\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) large inner diameter tubular structure. Therefore, for example, the maximum Q factor of the demonstrated 3.5 nH SiNx microtube inductor was less than 2.3@2 GHz. Moreover, the pinhole effect in SiNx thin films necessitates additional process solutions, undoubtedly escalating manufacturing risks and limiting its practical application19. To address the pinhole issues associated with PECVD SiNx nanomembrane, atomic layer deposition (ALD) aluminum oxide (Al2O3) layer or sputtered aluminum nitride (AlN) layer can be deposited on top of the SiNx nanomembrane20. However, in order to complete the rolling, the thickness of the conductive metal layer is limited to be less than a few hundred nanometers, resulting in a relatively large ohmic loss and low Q factor. Recently, post electroplating method was proposed and implemented for SiNx SRuM passive components, which provides a very promising way to solve this bottleneck problem of SRuM technology21.

In this paper, a wafer-scale metal self-rolled-up membrane (M-SRuM) platform is proposed and used to design and fabricate wafer-scale high-performance microtube lumped passive components on a commercial 4-inch sapphire batch fabrication line. Unlike in the traditional SiNx S-RuM technology, other than conducting signals, composite strained metal layer is designed to provide the rolling force instead of SiNx nanomembrane, which realize a simple way to fabricate the tubular lumped passive components with smaller on-chip footprint without any pinhole issue. Detailed analysis was conducted to investigate the impact of structural parameters on the electrical performance of self-rolling passive lumped components. Moreover, wafer-scale post electroplating of M-SRuM inductors with Ti/Cr/Cu layers was demonstrated to greatly improve the Q factor, and the standalone M-SRuM inductors were successfully cut off from a 4-inch sapphire wafer by laser modification cutting.

Results

Structure design and processing flow

The structure design and processing flow of the M-SRuM platform are shown in Fig. 1, which is compatible with typical semiconductor processing, see Methods and Movie 1 for detailed manufacturing processes. The platform imposes no strict limitations on the substrate material, requiring only a smooth surface, good rigidity, and insulation properties. In this study, a sapphire substrate was chosen to accommodate an XeF2 dry etching environment. Alternatively, if a silicon substrate were employed, an XeF2 resisted protection layer (e.g. SiO2) or photolithography resist could be applied to protect the silicon surface before etching, or a hydrogen peroxide wet etching process could be utilized19. The platform offers flexibility in device fabrication by simply altering the layout of the conductive layer. This study exemplifies this flexibility through the examples of RF inductors and capacitors. Figure 1a-e shows the multilayer membrane structure design and primary processing steps, and each layer material is shown in Fig. 1f. Figure 1a-b-c1-d1-e1, 1a-b-c2-d2-e2 illustrates the fabrication of M-SRuM inductors and capacitors, respectively. A different step for the deposition of the metal layer is shown in Fig. 1c. The entire process requires only three lithography steps. Notice that the aluminum oxide (Al2O3) layer with a thickness of 15 nm covers the sacrificial surface to ensure the direction of rolling and electrical isolation. The tensile stress is mainly provided by the chromium (Cr) layer, and the titanium (Ti) layer is used for adhesion. In this design, the Al2O3 film is prepared using an atomic layer deposition (ALD) system, while the stress layer and metal layer are successively deposited in the same processing sequence through electron beam evaporation (E-beam). In the case of no post-electroplating is needed, a 5 nm thick gold layer can be deposited on the copper layer surface after the deposition of Ti/Cr/Cu metal multilayers to prevent the oxidation. Figure 1g shows the top view of the fabricated wafer-scale M-SRuM inductors on a 4-inch sapphire wafer. In the red dotted line exploded box shown in Fig. 1g, several types of M-SRuM inductors with 12 different design types are fabricated on a die area, and their photo images are shown in Fig. 1g with a fabrication yield of 91.7%.

a Deposition of 40 nm Ge on a sapphire wafer and the 1st lithography step to define a mesa by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) or reaction ion-etching (RIE). b Deposition of 15 nm Al2O3 thin film by ALD. c (1-2) After the 2nd lithography step, Ti-Cr-Cu multiple thin film layers were deposited sequentially on the mesa. d (1-2) The 3rd lithography step was used to define an etching window. e (1-2) Removal of Ge sacrificial layer to trigger the self-rolling process of the stacked membrane. f layers display. g Top view of the 4-inch sapphire wafer after processing and top view of microtube RF inductor samples with 12 different design types.

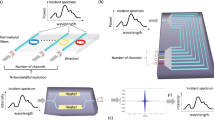

Working mechanism and electrical design

The pattern and structural dimensions of the M-SRuM inductors and capacitors before rolling up are shown in Fig. 2a, e. The layout design of the components encompasses both the component section and the test fixture section, with specific dimensional parameters detailed in Table 1. The inset figure in Fig. 2a illustrates the chamfer design, which controls the direction of film stress, guiding it to roll steadily along the designed track19. As shown in Fig. 2b, the inductance is derived from the self-inductance of each cell \({L}_{{self}}\) and the mutual inductance between cells. The distributed capacitance \({C}_{C}\) exists between layers of the circular rolled-up cells in parallel, which is the function of structural parameters and frequency. The parasitic capacitance \({C}_{S}\) can be neglected due to the small projection area of the rolled-up structure on the substrate, which significantly reduces the substrate parasitic effects. Figure 2c shows optical images of 2-cell M-SRuM inductor. The nanoscale thickness of the Al2O3 layer can be seen between the cells. Figure 2d presents an equivalent lumped model for the M-SRuM inductor22, allowing the flexible, discrete design to meet various application scenarios. The model primarily includes resistances \(({R}_{1},{R}_{2},\ldots {R}_{i})\), distributed capacitance \({C}_{C}\) between coils and parasitic capacitance \({C}_{S}\) between inductor and substrate and self-inductance_ \({L}_{{self\_i}}\) and mutual inductance(the mutual inductance of adjacent cells_\({M}_{{adj}}\) and the mutual inductance of far cells_\({M}_{{far}}\)): \({L}={L}_{{self\_}1}+\ldots+{L}_{{sel}{f}_{n}}-{M}_{{adj}}-{M}_{{far}}\). Resistances can be calculated by \(R=\rho {l}_{s}/({\omega }_{s}{t}_{{eff}})\), where \({t}_{{eff}}=2\sqrt{2/\omega \mu \sigma }(1-{e}^{-t/\sqrt{\frac{2}{\omega \mu \sigma }}})\) is the effective thickness, \(\rho\) is the electrical conductivity, which depends on surface roughness and the operating temperature. Therefore, a two-pronged approach was taken to reduce equivalent resistance and achieve excellent electrical performance in the design. On the one hand, economically efficient and highly conductive copper was chosen as the primary conductive layer; on the other hand, efforts were made to maximize the deposition thickness of the metal film up to 345 nm in experiment, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

a Structural parameter of the M-SRuM inductor. b Schematic of the parasitic parameters of the M-SRuM inductors. c Optical image of the M-SRuM inductors. d The equivalent circuit model of the M-SRuM inductors. e Structural dimension parameters of the planar capacitors. f Schematic of the parasitic parameters of the M-SRuM capacitors. g The equivalent circuit of the M-SRuM capacitors.

As shown in Fig. 2e, the structure of M-SRuM components (a capacitor was designed as an example) can also employ a side-bar approach to stabilize directional rolling without contributing to any electrical characteristics. This approach doesn’t introduce additional processing steps or impose other strain loads on the component. The working mechanism of the M-SRuM capacitor can be represented by the equivalent lumped circuit model as shown in Fig. 2f, g23. Unlike the traditional planar interdigital capacitors primarily rely on gap capacitance, the M-SRuM capacitor, due to its unique structure, can simultaneously possess gap capacitance \({C}_{{f\_i}}\) between electrodes, overlapping capacitance \({C}_{P}\) in the overlapping region between adjacent turns, and parasitic crosstalk capacitance \({C}_{T}\) between turns formed by feedlines. Optical images of the M-SRuM capacitor with bar are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

The presence of overlapping capacitance \({C}_{P}\) is particularly noteworthy, as it enables a significant enhancement in the capacitance of the M-SRuM capacitor compared to planar interdigitated capacitors. Optical images of the M-SRuM capacitor are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2e (with supporting bars) and (f). Figure 2g distinctly illustrates the interlacing of different electrodes, forming the state of plate capacitance.

According to the working mechanism of M-SRuM components, for inductors, the inductance can be increased by increasing the number of rolled-up turns and serially connected rolled-up cells, or reducing the canceling mutual inductance between cells by increasing the cell separation distance \({l}_{c}\). For a M-SRuM capacitor, the gap capacitance \({C}_{g}\) between fingers is a constant value and the parasitic crosstalk capacitance \({C}_{T}\) is negligible. Therefore, the inner diameter depended overlapping capacitance \({C}_{P}\) dominates the value of the capacitor, which is able to be tuned by engineering the residual stress of each thin film layer to create different overlapping status of the interdigital fingers. This unique characteristic allows the capacitance of M-SRuM capacitors to be designed in a wide range. The capacitance value could be several orders of magnitude different, which enables the M-SRuM capacitors to be used as both energy storage and RF application components22,23.

EM analysis of M-SRuM inductors and capacitors

Electromagnetic (EM) finite element modeling (FEM) analysis of M-SRuM inductors considering skin effect and proximity effect is proposed to precisely predict the electrical performance. As shown in Fig. 3a, the skin effect distributed at both ends of the microtube can be quantitatively calculated, which increases the ohmic loss at high frequencies of 5 GHz, and the thickness of the copper layer tc of 100 nm. Figure 3b shows the proximity effects of the M-SRuM inductor with different separation distance between two cells. Under a current excitation of 100 mA at a frequency of 5 GHz, the current is concentrated inward in the section of the copper strip with the current density reaches a maximum value of 2.5 × 109 A/m2 when the separation distance is 5 μm, which is ~2 times larger than that of the copper strip with the separation distance of 50 μm. The current is mainly affected by the skin effect and distributed at the edge of the conductor section when the inductor cell separation distance is 50 μm. Due to the structural characteristics of the M-SRuM inductors, the current transmission between adjacent cells is in different directions, and the alternating magnetic fields generated by each other create eddy currents on the other adjacent cell. The superposition of the working current and the excited eddy current makes the actual current flow to the adjacent side concentrated, which will undoubtedly increase the effective resistance of the conductor and increase the loss.

a Skin effect of M-SRuM inductor. b Proximity effect of M-SRuM inductor. c Magnetic flux density distribution and magnetic coupling cancellation of M-SRuM inductor. d, e Diametral l2 and axial l1 magnetic flux intensities. f-h Charge distribution of the M-SRuM interdigital capacitor: maximum, average, and minimum. i-k Electric field at different states of the interdigital distribution of the M-SRuM capacitor: maximum, moderate, and minimum.

Figure 3c illustrates the magnetic flux density distribution of the cross-section of two inductor cells with an inner diameter of 60 μm, lc = 30 μm ws = 100 μm, N = 3 under 100 mA DC excitation. This model was used to determine the length of the connecting line \({l}_{c}\) to achieve an acceptable penalty of magnetic coupling cancellation between adjacent cells, M-SRuM inductors exhibit a strong magnetic flux confinement capability compared to planar spiral inductors due to the 3D tubular structure which helps to better limit the magnetic field, thereby enhancing the magnetic energy storage capability, and significantly reducing the footprint and substrate parasitic capacitance to obtain high inductance density, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Figure 3d, e shows the magnetic flux intensity B in axial direction and diameter direction of the M-SRuM inductor in series of two cells in Fig. 3c. From the axial direction l1, the magnetic flux intensity B of the middle position of a single inductor is the largest, and it decreases rapidly to both sides due to the maximum mutual coupling of magnetic field at the middle position. The magnetic flux intensity B in the diameter direction l2 shows that the magnetic flux intensity B is greater closer to the electrified metal, and the minimum B is in the middle of the ring. A solution to address this issue is to increase the thickness of the metal layer. However, hundreds of nanometers thickness could be the limitation of the metal layer for a successful rolling unless the residual stress difference of multiple layers could be further increased.

Figure 3f-h presents FEM simulations of the charge distribution in M-SRuM capacitors under different interdigitated configurations, and Fig. 3i–k shows the corresponding potential distribution. In Fig. 3f, i, the capacitor is in a state of maximum capacitance, where the interdigitated electrodes of adjacent layers overlap entirely. Figure 3g, j represents the most common state for M-SRuM RF capacitors, with partial overlap of electrodes between adjacent layers, resulting in a mid-range capacitance value. Finally, Fig. 3h, k illustrates the minimum capacitance state, where the interdigitated electrodes of adjacent layers with the same polarity completely overlap, resulting in no potential difference between interdigitations, and the capacitance is primarily derived from the gap capacitance \({C}_{g}\), gap capacitance \({C}_{{f\_i}}\) between electrodes and parasitic crosstalk capacitance \({C}_{T}\). The distribution of interdigitations determines the size of the overlapping capacitance \({C}_{p}\), thereby influencing the overall capacitance of the capacitor. The capacitance of M-SRuM capacitors, as compared to Planar interdigital capacitors, not only experiences a significant increase in magnitude but also markedly reduces the footprint of the capacitor.

M-SRuM inductors and capacitors with different structures and metal layer (copper) thicknesses have been successfully mass-produced from a four-inch wafer. The manufacturing processes for inductors and capacitors are highly compatible, allowing for the batch preparation of various devices on the M-SRuM platform, which offers increased cost-effectiveness. Specific structures and electrical performances are detailed in Table 2, except for Ti (100 nm)/Cr (70 nm) used in batch 3.1, the other samples are fabricated using Ti (100 nm)/Cr (100 nm) metal layer. With inductance ranges from 0.6 nH to 3.4 nH and Q factor ranges from 0.6 to 7.3. The maximum inductance density and capacitance density reach 2.26 μH/mm2 and 1528.4 pF/mm3, respectively (The RF characteristic of C2 is shown in Supplementary Fig. 6). The inductance of planar spiral inductors exhibits a linear relationship with the metal wire length, whereas the inductance of M-SRuM inductors shows a superlinear relationship (almost square law relationship). This suggests that M-SRuM inductors may not require a larger area compared to that of the planar spiral inductors with the same inductance, especially when the required inductance is large. This means even the area these M-SRuM inductors occupied originally in the planar state cannot be used for any other patterns, the entire chip size could be smaller than that of chips using planar spiral inductors. For example, the planar area of batch 2.1 is 44% smaller than the planar spiral inductor24, yet these values still fall short of the ultimate potential of the M-SRuM platform.

The inner diameter can reach 42 μm as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, and the fabrication process is not only more efficient but also significantly smaller than the inner diameter of the SiNx SRuM RF capacitors reported previously25.

A large number of M-SRuM inductors and capacitors with various physical dimensions were successfully fabricated, and the corresponding design layout and optical sample images are shown in Fig. 4a-p (Ti-Cr-Cu:100 nm-100 nm-100 nm. Al2O3:15 nm. Ge: 40 nm). Also, the diameter can remain a constant number once the layered membrane structure is determined. For the samples with the same rolled-up length \({l}_{s}\) but different strip width \({w}_{s}\) and connecting line length \({l}_{c}\) on a same \({4}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\) Wafer, the variation of outer diameter was calculated to be 3.84 μm based on the data in Fig. 4q. After three months of being exposed to the air without any packaging, the inner diameter of M-SRuM inductor samples shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 remain unchanged showing the stability of M-SRuM microtube structures, which indicates that there is ample time for the subsequent encapsulation of the self-rolling devices. The results of I-V tests of samples (\({t}_{c}=100{{{\rm{nm}}}}\)) under input DC voltage from 0 V to 1 V are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 4, and the DC resistance can be calculated to be 6.5 Ω, 7.8 Ω, and 9.1 Ω, respectively. (Note that the resistance of the fixture is 4.6 Ω). Therefore, the resistance of the device is 1.9 Ω, 3.2 Ω, and 4.5 Ω, respectively. Moreover, the M-SRuM inductor samples are able to work at an input DC of 100 mA or 3.3 A/mm2 area current density with minimal ohmic heating effect, meeting the requirement of the current handling ability of most RF on-chip applications.

The electrical properties of M-SRuM inductors and capacitors

The electrical performance of the M-SRuM inductor and capacitor are indicated in Fig. 5 and the principle of the test is shown in Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14. The frequency-dependent inductance and Q factor of M-SRuM inductor samples v.s. key physical parameters such as the number of cells, the length of the metal strip \({l}_{s}\), the width of the metal \({w}_{s}\), and the thickness of the metal strip tc are plotted in Fig. 5a to Fig. 5d, respectively. It can be found that there is a linear relationship between the inductance and the number of cells, a square law relationship between the inductance and the number of turns, or the rolled-up strip length. However, for a narrower strip, the change of the inductance and the Q factor is uncertain, which depends on the balance of the reduced cross-talk parasitic capacitance and the increase of the inductance of one cell, as shown in Fig. 5a. It can be noticed from Fig. 5b that the length of the strip (batch#1.2&1.3) \({l}_{s}\) is increased from 890 μm to 1300 μm (the diameter and the number of turns is only increased by 4 μm and 2.1 turns, respectively), the inductance value is increased from 0.6 nH to 1.3 nH, and maximum Q factor is increased from 3.5 to 5.2. More importantly, the footprint area is only increased by 5% when the inductance is increased by 117%. As shown in Fig. 5c It is easier to obtain higher inductance with smaller width ws, but too small width ws will have higher ohmic resistance, which will cause smaller Q factor (batch#2.1).

a Inductance and Q factor with different cells. b Inductance and Q factor with different length \({l}_{s}\). c Inductance and Q factor with different widths \({w}_{s}\). d Inductance and Q factor with different thickness \({t}_{c}\). e Temperature stability of electrical properties of the inductor. f Capacitance with frequency in different states.

Figure 5d demonstrates the comparative electrical performance of M-SRuM inductors with copper layer film thicknesses of 100 nm and 75 nm. It’s evident that the thickness of the metal layer significantly influences the Q factor. In the preceding process, the most effective method for enhancing the Q factor was increasing the strain layer’s stress to accommodate thicker metal layers, thereby reducing film resistance. As shown in Fig. 5e, the thermal stability of the M-SRuM inductor was tested, details in Supplementary Fig. 7. When the temperature increases by 80 Kelvin, the inductance changes by 9% at 3 GHz due to the relatively larger thermal resistance of the 3D structure, which could be reduced by post-chemical plating or electroplating and adding a heat sink structure to the M-SRuM inductor. Figure 5f illustrates the maximum (state A), moderate (state B), and minimum (state C) states of a capacitor. As the overlapping area between adjacent layers increases, the capacitance rises from 0.012 pF to 0.5 pF. Correspondingly, the resonant frequency decreases. Moreover, the M-SRuM capacitor reduces its area relative to its planar structure by 92%. The relationship between the resonant frequency \({f}_{c0}\) and the capacitance value (C) of the M-SRuM capacitor can be estimated as: \({f}_{c0}=1/\left(2\pi \sqrt{C\times {ESL}}\right)\), where ESL represents the equivalent series inductance. Apparently, capacitors with smaller capacitance values and lower ESL exhibit higher SRF.

It can be found that the \({L}_{{density}}\)(inductance/footprint) and Q of M-SRuM inductors are 186 nH/mm2 and 7.3@8 GHz, respectively, as shown in Table 3, which has higher inductance density compared with the ordinary inductor. Compared with the best performance of the 3.5 nH SiNx SRuM inductors reported previously, M-SRuM inductors with Ti/Cr/Cu metal layer shows much better electrical performance. For the 2.9 nH M-SRuM inductor sample without post electroplating in this work, the inner diameter is only 60 μm which is reduced by 140 μm. The on-chip footprint is therefore reduced by 88% with inductance density increased by 5.9x (186 nH/mm2). More importantly, the maximum Q factor improved from 2.3@2 GHz to 7.3@8 GHz meaning higher working frequency is available.

This substantiates the ability to accommodate thicker metal films, thereby achieving higher Q factor. The M-SRuM capacitor boasts a capacitance density of 1528.4 pF/mm3 and operates within the microwave frequency range. In comparison to conventional on-chip capacitors, it not only demonstrates a magnitude-level advantage in energy storage capacity but also spans a broader range of applicable frequencies.

Table 4 delineates a comparative analysis between M-SRuM inductors, capacitors, and mainstream commercial electronic components. Passive components engineered on the M-SRuM platform represent a revolutionary shift in the design and manufacturing principles of on-chip passive components. This transformation extends to reshaping spatial electromagnetic distribution and storage methods, endowing them with remarkably high electromagnetic energy density characteristics and a broader application frequency spectrum. For instance, the M-SRuM inductor (Batch#2.1) surpasses TDK by 50 times and MURATA by 200 times, while the M-SRuM capacitor outperforms MURATA by a factor of 3000. These findings underscore the immense commercial potential inherent in M-SRuM technology.

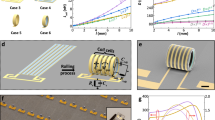

Post-electroplating and method to obtain standalone M-SRuM components

Due to the limitation of SRuM technology, it is almost impossible to roll micrometer copper layer into tubular structures, which is always accompanied by serious skin effect. Therefore, the most effective way to solve the problem is to do post electroplating to thicken the conductive metal layer after the tubular structure is formed. In this paper, the Cu layer is put on top of the surface to facilitate the implementation of the post-electroplating. The electroplating recipe is as follows: as shown in Fig. 6a, the sample was immersed in the electroplating solution with the anode connected to a phosphorus-copper plate and the cathode connected to the common sample pad on the wafer. The base plating solution (virgin makeup solution, VMS) used CuSO4 as the primary salt (18 g/200 ml) with a Cl-concentration of 60 mg/L. A cathode probe was attached to the pad at the center of the common sample pad, and upon applying current, a reduction reaction occurred on the device surface along the connection line of the common sample pad, resulting in a thicker copper layer and completing the electroplating of the entire inductors. Notably, the inductors needed to be connected to the current before adding the electroplating solution to prevent corrosion of the inductors by the solution. This precaution is essential, as copper ions on the surface of inductors without an applied current may react with the electroplating solution. To improve the quality and uniformity of the electroplated copper layer, the reaction platform was placed on a magnetic stirrer to agitate the solution continuously. Pulse current was used for electroplating the inductors, with a 6 s on and 2 s off cycle to facilitate timely replenishment of copper ions, while the current was set at 6 mA.

a Electroplating platform controlled by pulse power supply. b Mask plate design for batch electroplating of M-SRuM inductors. c, d Electroplating of microtubes: Ti (100 nm)/Cr (100 nm)/Cu (50 nm), after 100 electroplating cycles, the diameter of the microtube is 36.2 μm, and the thickness of edge becomes 1.32 μm. e Electroplating of M-SRuM inductor: Ti (100 nm)/Cr (100 nm)/Cu (120 nm), the M-SRuM inductor after 200 plating cycles and Q factor reaches 18 without de-embedding, the diameter is 80 μm. f The standalone M-SRuM components were cut from the sapphire wafer using laser modification cutting.

Figure 6b shows the mask design for the wafer-scale electroplating inductors. By connecting all inductors to the same conductive pad through the connection line of the common sample pad, simultaneous electroplating can be completed. As shown in Fig. 6c-d, a batch of microtubes can be plated through the connection line of the common sample pad. After 100 pulse cycles, the thickness of copper increased from 50 nm to 1.32 μm after plating, and the diameter remains only 36.2 μm with little change, more details in Supplementary Fig. 9. For 1.1 nH M-SRuM inductor sample, plating for 200 pulse cycles results in a significant reduction of the DC resistance from 1.4 Ω to 0.16 Ω, more details in Supplementary Fig. 10. The thickness of copper layer after plating is ~2.7 μm based on the experiment data shown in Fig. 6c-d, and more plating details on the inductor structure in Supplementary Fig. 11 and Movie 2, the effectiveness of electroplating is directly influenced by the size of the gap between turns. When the structure is overly compact, it is unable to receive a timely replenishment of copper ions, which impairs the plating quality. However, by utilizing mechanical control or making structural modifications to ensure an adequately gap size, favorable electroplating results can be achieved. After plating, the Q factor of the M-SRuM inductor is greatly increased to 18@1.4 GHz with inner diameter of only 80 μm as shown in Fig. 6e. It can be seen that increasing the thickness of the top metal layer through the post-plating process is able to reduce the DC ohmic resistance significantly and to improve the Q factor greatly. Compared with the commercial on-chip 1 nH inductor and its Q factor in smic5511rf design kit (ind _2Tdiff alutm_psub), the 1.1 nH M-SRuM inductor sample takes up only 69% of its chip area, and 1.45x larger inductance density and 2.43x better Q factor.

As shown in Fig. 6f, the laser modification cutting was successfully used to cut off standalone M-SRuM components off the 4-inch sapphire wafer. There is no structure change after cutting meaning that the method can effectively protect the structural integrity of the on-chip components of the 3D structure. The minimum distance between the cutting position and the element is 150 μm when the wafer thickness is 450 μm, and this distance can be further reduced if thinner wafer is used. In addition to this, the stability tests in Supplementary Figs. 8, 12 and Movie 3 also demonstrate the excellent stability of the 3D structures fabricated by this technique.

Discussion

This paper demonstrates a novel self-rolled-up platform for on-chip lumped passive components, exemplified by inductors and capacitors. The fabrication process was conducted on a 4-inch commercial semiconductor production line, underscoring its potential for commercial viability. Featuring remarkably high electromagnetic density, the passive components crafted via this innovative approach offer considerable promise for both research and commercial applications. Not only are they suitable for cutting-edge research in miniaturized applications, but they also represent a paradigm shift in the manufacturing methodologies of traditional passive components. Compared to the SiNx process, the pure metal-driven platform obviates the need for SiNx and Al2O3 required to mitigate pinhole effects.

However, several critical challenges remain for these 3D components, which lack standardized design and manufacturing processes. From a design perspective, the establishment of a standardized process design kit (PDK) is crucial for guiding circuit integration, which still requires extensive process validation. Since the structure of a M-SRuM components is mainly controlled by the stress of its multilayer films, how to control the stress uniformity of each layer must be considered when fabricating at wafer scale. In addition, in the complex post-electroplating environment, for such small components, plating uniformity also needs to be considered, and these issues need to be more concerned in larger wager wafer scale production processes. The control of multilayer stress in M–SRuM passive components is paramount throughout the entire fabrication process in the manufacturing process. Furthermore, packaging is an unavoidable step towards the application of M–SRuM passive components, necessitating a comprehensive consideration of electrical performance, mechanical, and chemical protection. A standardized packaging methodology could serve as a vital reference for similar complex 3D components packaging.

Methods

The fabrication process begins with the preparation of the sapphire wafer, which has a diameter of 4 inches and a thickness of 650 μm, serving as the substrate. A 50-100 nm Ge sacrificial layer is then deposited on the wafer surface using electron beam evaporation. Next, an anti-reflective coating and a positive photoresist (UV135) are spin-coated onto the wafer for the first lithography step, which defines the mesa. The lithographic exposure is carried out using a Nikon S204 DUV machine, followed by development with ZX238 developer. The mesa is then etched using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) with CHF3. After etching, the photoresist is stripped using a rinse of N-methyl pyrrolidone, followed by a plasma cleaning process to remove any residual photoresist. This cleaning step is performed at 50 °C for 6 minutes, with a gas flow rate of 500 sccm, a pressure of 1.2 mbar, and 600 W of power. The next step involves the deposition of a cover layer. A 15-20 nm Al2O3 layer is deposited at 250 °C using the MNT-S atomic layer deposition (ALD) system. For the second lithography step, a negative photoresist (K7250) is spin-coated, exposed using the Nikon S204 DUV lithography machine, and developed with ZX238 developer. The metal pattern is then created by sequentially depositing multilayers of Ti, Cr, and Cu through electron beam evaporation. The photoresist is removed through a rinse with N-methyl pyrrolidone. A third lithography step is used to open the etching window. This begins with spin-coating another layer of negative photoresist (K7250), followed by exposure and development using the same equipment and process as before. Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching is then employed to etch the alumina layer down to the Ge or even the substrate, exposing part of the Ge and forming a window. Finally, dry etching is performed using XeF2 to etch away the sacrificial Ge layer. This process releases the stress of multilayers, initiating the directional rolling process from the etching window and completing the preparation of the M-SRuM component.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the article, Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kim, D.-H. & Ahn, D. Self-Tuning LCC Inverter Using PWM-Controlled Switched Capacitor for Inductive Wireless Power Transfer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 66, 3983–3992 (2019).

Lim, Y., Tang, H., Lim, S. & Park, J. An Adaptive Impedance-Matching Network Based on a Novel Capacitor Matrix for Wireless Power Transfer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 29, 4403–4413 (2014).

Gomes, C. C., Cupertino, A. F. & Pereira, H. A. Damping techniques for grid-connected voltage source converters based on LCL filter: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 116–135 (2018).

Kim, D. et al. A CMOS-integrated quantum sensor based on nitrogen–vacancy centres. Nat. Electron. 2, 284–289 (2019).

Gabler, F., Karnaushenko, D. D., Karnaushenko, D. & Schmidt, O. G. Magnetic origami creates high performance micro devices. Nat. Commun. 10, 3013 (2019).

Huber, R. et al. Tailoring electron beams with high-frequency self-assembled magnetic charged particle micro optics. Nat. Commun. 13, 3220 (2022).

Ha, C. W., Prabhakaran, P. & Son, Y. 3D-Printed Polymer/Metal Hybrid Microstructures with Ultraprecision for 3D Microcoils. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 6, 165–170 (2019).

Thanh Le, H. et al. Microfabricated Air-Core Toroidal Inductor in Very High-Frequency Power Converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 6, 604–613 (2018).

Xu, X., Li, P., Cai, M. & Han, B. Design of Novel High-$Q$-Factor Multipath Stacked On-Chip Spiral Inductors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 59, 2011–2018 (2012).

Simon, P. & Gogotsi, Y. Perspectives for electrochemical capacitors and related devices. Nat. Mater. 19, 1151–1163 (2020).

Saleem, M. et al. Percolation phenomena of dielectric permittivity of a microwave-sintered BaTiO3–Ag nanocomposite for high energy capacitor. J. Alloys Compd. 822, 153525 (2020).

Wu, B. et al. One-step rolling fabrication of VO 2 tubular bolometers with polarization-sensitive and omnidirectional detection. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi7805 (2023).

Michaels, J. A. et al. Effect of Perforation on the Thermal and Electrical Breakdown of Self‐Rolled‐Up Nanomembrane Structures. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6, 1901022 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Self-rolling of vanadium dioxide nanomembranes for enhanced multi-level solar modulation. Nat. Commun. 13, 7819 (2022).

Khandelwal, A. et al. Self-Rolled-Up Aluminum Nitride-Based 3D Architectures Enabled by Record-High Differential Stress. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 29014–29024 (2022).

Ik Su Chun & Li, Xiuling Controlled Assembly and Dispersion of Strain-Induced InGaAs/GaAs Nanotubes. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 7, 493–495 (2008).

Zhou, Z. et al. Progress on 3D tubular passive electronics: Residual stress-based fabrication, application, and modeling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 150502 (2024).

Huang, W., Koric, S., Yu, X., Hsia, K. J. & Li, X. Precision Structural Engineering of Self-Rolled-up 3D Nanomembranes Guided by Transient Quasi-Static FEM Modeling. Nano Lett 14, 6293–6297 (2014).

Huang, W. et al. Monolithic mtesla-level magnetic induction by self-rolled-up membrane technology. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay4508 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. Monolithic Heterogeneous Integration of 3D Radio Frequency L−C Elements by Self‐Rolled‐Up Membrane Nanotechnology. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004034 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. Unleashing the Performance of Self‐Rolled‐Up 3D Inductors via Deterministic Electroplating on Cylindrical Surfaces. Adv. Mater. Technol. 9, 2400092 (2024).

Huang, W. et al. On-Chip Inductors with Self-Rolled-Up SiN x Nanomembrane Tubes: A Novel Design Platform for Extreme Miniaturization. Nano Lett 12, 6283–6288 (2012).

Luo, X. et al. Physical Modeling of Monolithic Self-Rolled-Up Microtube Interdigital Capacitors. 12, 9 (2022).

Zhang, Z. & Liao, X. Micromachined GaAs MMIC-Based Spiral Inductors With Metal Shores and Patterned Ground Shields. IEEE Sens. J. 12, 1853–1860 (2012).

Sang, L. et al. Monolithic radio frequency SiN x self-rolled-up nanomembrane interdigital capacitor modeling and fabrication. Nanotechnology 30, 364001 (2019).

Chen, C.-L. et al. Ultra-low-resistance 3D InFO inductors for integrated voltage regulator applications. in 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 35.2.1-35.2.4 (IEEE, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2016.7838546.

Eblabla, A., Li, X., Wallis, D. J., Guiney, I. & Elgaid, K. High-Performance MMIC Inductors for GaN-on-Low-Resistivity Silicon for Microwave Applications. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 28, 99–101 (2018).

Kang, J. et al. On-chip intercalated-graphene inductors for next-generation radio frequency electronics. Nat. Electron. 1, 46–51 (2018).

Blaž, N. V., Živanov, L. D., Kisić, M. G. & Menićanin, A. B. Fully 3D printed rolled capacitor based on conductive ABS composite electrodes. Electrochem. Commun. 134, 107178 (2022).

Ali, S. F. & Mandal, N. Design and Development of an Electronic Level Transmitter Using Inter Digital Capacitor. IEEE Sens. J. 19, 5179–5185 (2019).

Wang, Y., Ma, K. & Mou, S. A Compact SISL Balun Using Compensated Interdigital Capacitor. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 27, 797–799 (2017).

Ahmad, S., Khalid, N. & Mirzavand, R. Detection of Soil Moisture, Humidity, and Liquid Level Using CPW-Based Interdigital Capacitive Sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 10338–10345 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R & D Program of China under grant 2021YFA0715300 to Wen.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wen. H. and Z-K.Z. designed this work and wrote the manuscript, and all authors edited and revised the manuscript. Z-K.Z., Z-H. Z., Q.S., X.B. and H.Z. perform the experimental fabrication. H.Z. and X.W. conduct electrical performance testing and structural characterization of components. Z-K.Z, Wei. H. and Wen. H. conducted the data analysis. Wen. H., L.S., T.Y. and X.C. supervised the overall project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Zhang, Z., Zhang, H. et al. Wafer-scale platform for on-chip 3D radio frequency lumped passive components using metal self-rolled-up membrane technique. Nat Commun 16, 2491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57769-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57769-8