Abstract

Small modular reactors are the nuclear fission reactors with electric power output less than 300 MWe. To apply the enhanced safety of small modular reactors to build large-scale nuclear plants with any desired power ratings, the multi-modular scheme is recommended to be adopted, where multiple reactor modules are utilized to drive the common load equipment for power generation or cogeneration. The feasibility of multi-modular scheme is not verified until several plant-wide tests were carried out recently on the high temperature gas-cooled reactor pebble-bed module (HTR-PM) nuclear plant. The HTR-PM plant consists of two inherently safe nuclear reactors of 200 MWt, adopts the scheme of two reactor modules driving a common steam turbine, and operates commercially since December 6, 2023. In this paper, the responses of key process variables of HTR-PM plant in the tests of power ramping, turbine trip and reactor trip are provided, and the related multi-modular coordinated control method is also proposed. This result manifests the feasibility of multi-modular scheme practically, and shows the promising future of building large-scale nuclear plants with a system of small modular reactors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The inherently safe reactors are defined as those nuclear fission reactors whose safety are given purely by the principles of nature in physics and chemistry, without any intervention from electromechanical equipment or human operators. As noted by Alvin M. Weinberg, the emblematic feature of the second nuclear era is the effective operation of inherently safe commercial reactors1. The severe accidents at Three Mile Island in 1979, Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima Daiichi in 2011 highlight the fact that stringently keeping safety is essential for the widespread deployment of nuclear power plants (NPPs). According to the prediction made by Weinberg in ref. 1, the integral pressurized water reactor (iPWR) and the modular high temperature gas-cooled reactor (mHTGR) are seen as two viable options that may usher in the second era of nuclear energy. In fact, both the iPWR and mHTGR are two representative small modular reactors (SMRs) emerging since 2000s2, being fundamentally characterized as the fission reactors with a generating capacity of less than 300 MWe3. By incorporating the design features such as the reduced fuel inventory and the passive mechanism, SMRs are commonly endowed with passive or inherent safety, and their compact size affords flexibilities in fabrication, transportation, construction and siting. Not only can SMRs deliver clean energy to the off-grid locations lack of distribution and transmission infrastructure4,5, but they can also serve as local power and heat sources for populated urban areas and industrial hubs, promoting significant deep decarbonization efforts6,7. It is indicated in ref. 8 that the advanced SMRs, including the mHTGRs and the small molten salt reactors, possess potential to meet the substantial energy requirements being necessary to drive the forthcoming advancements in artificial intelligence (AI).

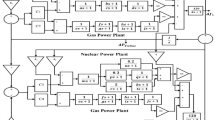

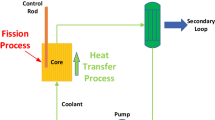

Especially, the mHTGR is the graphite-moderated and helium-cooled fission reactor designed so that both its power density and core diameter are firmly restricted, allowing for the natural decay heat removal through heat conduction, radiation and natural convection without requiring an emergency core cooling system9,10. Each fuel element of mHTGR consists of several thousands of tri-structural isotropic-coated (TRISO) particles integrated within a spherical or prismatic graphite matrix. A TRISO particle comprises a UO2 kernel encased in layers of pyrocarbon (PyC) and of silicon carbide (SiC), which can effectively prevent the escape of fission product under 1620 °C. The international nuclear sector has dedicated substantial efforts to the innovation and advancement of commercial mHTGR systems, and some notable mHTGR demonstration plants were designed in 1980s and 1990s such as the 200 MWt pebble-bed reactor HTR-Module in Germany by SIEMENS/Interatom11 and the 350 MWt prismatic reactor MHTGR in the U.S .by General Atomics12. Despite the substantial success of these two initiatives in research and development, the engineering deployment has not commenced due to numerous factors. Circa 2000s, both China and Japan constructed their own modular high temperature gas-cooled test reactors, the 10MWt pebble-bed high temperature gas-cooled test reactor (HTR-10)13,14 and the 30 MWt prismatic high temperature test reactor (HTTR)15. With the HTR-10 severing as a prototype and by taking cues from both the German HTR-Module and the U.S MHTGR, the nuclear power plant known as the high temperature gas-cooled reactor pebble-bed module (HTR-PM) has been developed based upon the partnership of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology (INET) serving as the technical authority, China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) taking the role of engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractor and China Huaneng Corporation (CHC) having the ownership16. The HTR-PM power plant is situated in the Shidao Bay area of China Shandong province, has been integrated to the grid since December 20, 2021, and commenced its commercial operation on December 6, 202317. From Fig. 1, the HTR-PM facility is composed of two mHTGR-type reactor modules of each 200MWt alongside a common steam turbine. Each reactor module is mainly composed of a pebble-bed one-zone mHTGR, a helical-coil once-through steam generator (OTSG) and a primary helium blower. The OTSG is arranged side-by-side to the reactor, and the primary helium blower is mounted on the top of the OTSG. Currently, the main steam temperature and pressure at the turbine inlet of HTR-PM plant are 520 °C and 11 MPa respectively. Once the reactor cores reach their equilibrium stage, it is possible to further improve the hot helium temperature at the core outlet, giving that the main steam will reach an operational temperature of 540 °C. During the time frame of August 23 and September 1, 2023, the loss of cooling tests were performed on both reactors at the rated power of 200 MWt, and the test results indicate that the residual heat can be naturally dissipated without any active intervention, demonstrating for the first time the presence of inherent nuclear safety on a commercial scale18. While the potential for achieving such inherent safety has been established in the test reactors like AVR19, HTTR15 and HTR-1012, the confirmation of inherent safety in a commercial reactor power level like 200 MWt is given for the first time on HTR-PM reactors, since the primary challenge of decay heat removal lies in handling the power level.

In addition to concerns regarding safety, the economic viability also plays a significant role in determining the feasibility of large-scale deployment of SMRs. With the decreased fuel inventory of each SMR, there is a restriction on the rated reactor thermal power. For instance, achieving the inherent safety of one-zone mHTGRs requires limitations on both the power density of the reactor and its diameter. This results in the rated thermal power output for both the German HTR-Module and the Chinese HTR-PM being consistently set as 200MWt. The economic viability of SMR facilities is significantly hindered by the limitation on rated thermal power when each SMR module is paired with its own individual steam turbine. In contrast to the single-modular configuration, utilizing a multi-modular approach with several SMRs sharing a common turbine can extend the passive or inherent safety features of an individual SMR throughout the entire nuclear power plant, thus enhancing the economic efficiency of SMR systems. In fact, the German HTR-Module utilizes a dual-module configuration involving two mHTGR modules supplying steam to a single turbine, while the U.S. plant using MHTGR technology comprises multiple reactor modules that provide steam for one or several turbines. From the simplified power generation process diagram shown in Fig. 2, the HTR-PM employs the multi-modular scheme analogous to the German HTR-Module, whereby the superheated steam provided by the two reactor modules are combined before being directed to the shared turbine for electricity generation.

The necessity of coordinated control in multi-modular nuclear plants arises from handling the couplings both within individual modules and across interconnected modules. The coordinated control amongst multiple reactor modules is fundamental for the implementation and functioning of multi-modular NPPs, recognized as a key technology in nuclear engineering since 1990 s. Kim and Bernard studied the operation characteristics of a pressurized water reactor (PWR)-type multi-modular nuclear plant, where a reactor module consists of a PWR and several U-tube steam generators (UTSGs)19. Perillo, Upadhyaya and Li investigated the potential for implementing coordinated control in a two-modular iPWR-type NPP through numerical simulation20. The initial findings in refs. 19,20 emphasize on the coupling feature amongst multiple modules, but fall short in portraying the coupling effect by dynamic system models and offering concrete control strategies for managing this coupling. Recently, a systematic approach has been established for the passivity-based control (PBC) of nuclear reactors and reactor modules through introducing the entropy production metric as a storage function21,22,23. Moreover, by describing the coupling across interconnected modules as a fluid flow network (FFN), the coordinated control among multiple modules is converted to the pressure-flowrate joint regulation of the FFN, and the PBC of FFNs is proposed correspondingly.24,25,26 The theoretical framework provided in refs. 21,22,23,24,25 supports the coordination of multi-modular NPPs.

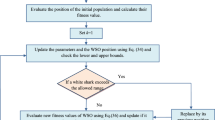

Given that the thermal power capacity of typical SMRs is restricted to ensure passive or inherent safety, a significant challenge in the advancement of SMRs lies in the development of large-scale NPPs using these power-restricted reactor modules. A viable approach is to implement the multi-modular scheme, where several reactor modules provide steam for a shared turbine. Although the adoption of multi-modular scheme has been seen in the SMR plant designs including the German HTR-Module and U.S. MHTGR, the practical verification of its feasibility remains unconfirmed, primarily due to the challenges in deploying multi-modular coordinated control. This study introduces a multi-modular coordinated control system to address the coupling of process variables within a single reactor module and across interconnected modules. Following this, the detailed plant-wide test results on the multi-modular coordination of HTR-PM plant in the scenarios including power ramping, turbine trip as well as reactor trip are presented. The test results confirm the practicality of the multi-modular scheme alongside the effectiveness of multi-modular coordinated control system. The verified multi-modular scheme is suitable for all those SMRs generating superheated steam. The multi-modular coordinated control advances in the common method of addressing the couplings both within a single reactor module and across multiple interconnected modules, making it applicable to the multi-modular NPPs with various SMRs. The results in this paper verify the feasibility of the scheme in building large-scale NPPs based on a system of small modular reactors.

Results

The coordinated control system (CCS) design of HTR-PM plant is proposed, and then the test results of plant-wide coordination in the scenarios of power ramping, turbine trip as well as reactor trip are presented to show the feasibility of the multi-modular scheme and the effectiveness of the CCS.

Coordinated Control System

The coordination amongst the modules of HTR-PM is mainly realized by the CCS shown in Fig. 3, which is composed of seven local controllers for the regulation of neutron flux, helium flowrate, feedwater flowrate, helium temperature, steam temperature, thermal power and main steam pressure, where the first six controllers are equipped to each reactor module individually. The pairing of the controlled variables and the manipulated variables of these seven local controllers are shown in Table 1. From Fig. 2, the two reactor modules supply superheated steam with identical parameters to a common turbine-generator system, and the fluctuations in the main steam pressure affect the operation of both modules. Thus, the coordination between two reactor modules is mainly managed by the main steam pressure controller stabilizing the common steam pressure at the inlet of the steam turbine. To ensure effective coordination across modules, it is also necessary to stabilize the steam temperatures at the secondary outlets of the steam generators by the individually equipped steam temperature controllers.

The CCS of HTR-PM plant is implemented on the distributed control system (DCS) platform, of which the architecture design is depicted in Fig. 4. It can be seen from Fig. 4 that the DCS of the HTR-PM plant is structured to two distinct layers referred to as Level 1 and Level 2. Level 1 encompasses a set of control stations interconnected with redundant real-time servers via Level 1 ethernet, while Level 2 features an interconnected network of several operator stations, an engineer station, along with redundant historical servers, real-time servers, and computing servers through Level 2 ethernet. The real-time servers are integrated to both Levels 1 and 2 networks, facilitating the information exchange between the two levels. Measurement data is transmitted from field instruments to the Level 1 control stations via hard-wired links, which subsequently drive the control stations to give the hardwired driving signals to various actuators, including the control rods, helium blowers, feedwater pumps and main steam regulating valve. These control actions are in response to the commands from operators and the discrepancies identified between the measured values and the desired setpoints of the controlled variables. Each control station comprises multiple input-output (IO) modules, along with a local control computer and a backup redundant local control computer in hot standby mode. Figure 5 illustrates the human machine interface (HMI) associated with the CSS function of #1 reactor module, indicating that all the automatic controllers are activated.

The DCS is structured to two layers called Level 1 and Level 2. Level 1 composes of local control stations interconnected with real-time severs. Level 2 features a network of operator stations, historical severs, real-time servers and an engineering station. The real-time servers integrate to both Levels 1 and 2.

Furthermore, there exists a redundancy of sensors utilized for the measurement of process variables. From Fig. 3, it can be seen that the measurements of process variables, including the neutron flux, helium flowrate, feedwater flowrate, steam temperature as well as steam pressure at the secondary outlet of OTSG, feedwater temperature as well as feedwater pressure at the secondary inlet of OTSG, and main steam pressure at the inlet of turbine, all of which serve as the input signals of CCS. To ensure accuracy and reliability in measuring each process variable fed into the CCS, multiple redundant sensors, typically three or four, are installed. In cases where there are three redundant sensors for the process variables, a 2 out of 3 decision-making logic is utilized to prevent unnecessary reactor scrams. In cases where there are 4 redundant sensors for process variables, a logic system is implemented where 3 out of 4 logic is adopted.

Test Results

The CCS of HTR-PM ensures comprehensive coordination across the plant by the use of local controllers, with details regarding the algorithms employed by these local controllers outlined in the methods section. To assess the coordination of HTR-PM plant in the scenario of normal power maneuvering and typical anomaly scenarios, a series of tests were performed on the HTR-PM across September and October 2023. As introduced in ref. 18, for shaving the peaks of power density inside reactor cores, the HTR-PM reactors adopt the MEDUL (MEhrfach DUrchLauf = multiple passes through reactor core) cycle of fuel burnup with a recycling rate of 15 times. Due to the challenge in continuously operating the fuel handling systems, the two HTR-PM reactors operate with a rated power of 200 MWt currently. All the tests are conducted at reactor power-levels exceeding 190 MWt, which is appropriate for the typical operations and verifying the multi-modular coordination. The plant-wide responses of the key process variables in the scenarios of power ramping, turbine trip and reactor scram are provided as follows.

On September 13, 2023, the power ramping test was conducted. Initially, the HTR-PM operates at the full plant power, i.e. the thermal power-levels of both reactor modules are consistently held at approximately 200 MWt. Subsequently, both modules #1 and #2 experienced a sequentially gradual decrease in their thermal power setpoints, lowering to 175 MWt with a constant rate of 2.5 MWt/min. After a stable maintenance period about thirty minutes at 175 MWt, the thermal power setpoints of both modules ramped up sequentially back to their initial values about 200 MWt. The responses of the key process variables of module #1, module #2 and the conventional island are shown in Fig. 6, where the hot and cold helium temperatures are measured at the primary inlet and outlet of steam generator. It can be seen that the transient behaviors exhibit a commendable performance, showing almost no overshoot in regard to nuclear power, thermal power, primary helium flowrate and secondary feedwater flowrate. The secondary outlet steam temperatures from both steam generators, which are the most sensitive process variables, are effectively maintained within a limit of 5 °C. In this context, the sensitivity of steam temperatures is attributed to the low thermal inertia of OTSG. Moreover, the fluctuations in main steam pressure during power ramping are recorded to be less than 0.3 MPa.

On September 15, 2023, the turbine trip test was conducted, during which the conventional island operator manually initiated the trip of turbine. Given that the bypass system has a limited capacity equivalent to the rated steam flowrate of one module, the automatic interlock mechanism triggers the emergent shutdown of the #1 reactor upon the turbine trip, while the steam flow from the #2 module is redirected to the condenser through the rapid actuation of the bypass regulating valve for that reactor. The delayed response of the bypass regulating valve results in a transient spike in main steam pressure during the shutdown of turbine, leading to a rapid reduction in the feedwater supply of the #2 module. The CCS stabilizes the feedwater flowrate of the #2 module by adjusting the pump speed, ensuring that the reactor remains operational and does not scram. The responses of the key process variables of module #1, module #2 and the conventional island are shown in Fig. 7, where the hot and cold helium temperatures are measured at the primary side inlet and outlet of steam generator respectively. It is indicated by Fig. 7b that the CCS is capable of stabilizing the feedwater flowrate for module #2, exhibiting a negative overshoot of 15 kg/s which represents approximately 21% of the rated feedwater flowrate. Even though the deviation in feedwater flowrate is prominent, the rapid actuation of the bypass regulating valve keeps the duration of the transient brief, thus limiting its impact on the other process of the #2 module, e.g., the variation in outlet steam temperature of OTSG is merely 1 °C.

On October 8, 2023, a malfunction in the transducer of module #1 triggered a reactor scram. At the HTR-PM, each helium blower has a frequency-converter for regulating the primary helium flowrate. Prior to the occurrence of the frequency-converter malfunction, the HTR-PM operated at the power-level of 2 x 180 MWt. Subsequently, the failure of the helium blower frequency-converter in module #1 resulted in a rapid decline in the primary helium flow, which activated the reactor protection system and caused the scram of reactor #1. As a result of the rapid closure of the secondary inlet and outlet valves of the #1 steam generator, initiated by the protection system, the main steam pressure declined swiftly, which subsequently caused a quick rise in the secondary feedwater flowrate of the #2 module. In the absence of any action from the CCS, a swift decline in the helium-to-water ratio could prompt the safety mechanisms to initiate an emergent shutdown of reactor #2. The responses of the key process variables of the #1 and the #2 modules and the conventional island are shown in Fig. 8, where the hot and cold helium temperatures are measured at the primary inlet and outlet of the steam generator respectively. The timely regulation provided by the CCS ensures that the main steam pressure remains consistent by adjusting the opening of main steam regulating valve. It can be observed from Fig. 8 that the maximal fluctuation in the feedwater flowrate of module #2 does not exceed 2 kg/s, whereas the variation in the main steam pressure remains below 0.5 MPa.

Discussion

From Fig. 2 showing the schematic diagram of HTR-PM power generation process, the superheated steam generated by the two reactor modules are combined before entering the turbine. and each module is equipped individually with its own feedwater pump and high pressure heater (HPH). The change in the rotation rate of one pump not only affects the feedwater flowrate for its corresponding module but also alters the main steam pressure at the turbine inlet, which in turn impacts the feedwater flowrate of the other module, indicating that these modules are interconnected through the shared turbine. Moreover, the employment of an integrated and compact primary loop design commonly found in SMR configurations result in a tighter coupling amongst the process variables of individual reactor modules2,27. As shown in Fig. 1b, the mHTGR and OTSG in the same reactor module are arranged side-by-side to each other, leading to a strong interdependence amongst the process variables, which encompass the neutron flux, the temperatures of both hot and cold helium, the primary helium flowrate, as well as the temperatures of both steam and feedwater. The coupling within an individual reactor module as well as across multiple modules are commonly present in multi-modular SMR plants such as the German HTR-Module, the U.S. MHTGR and the Chinese HTR-PM, which is indeed the primary challenge hindering the progress of deploying multi-modular SMR power plants.

At present, several innovative designs of SMR units, such as the Xe-10028 and the NuScale29,30, adopt the single modular scheme that every reactor module is allocated with a single steam turbine individually. The coupling across modules in the multi-modular plants is converted to the coupling across single-modular units in the same grid. While the individually equipped turbines enlarge the capital investment to some extent, the single modular scheme may still be deemed suitable for electricity generation. Nonetheless, for developing SMR cogeneration facilities such as the next generation of nuclear plant (NGNP)31, it is essential to integrate the steam generated from multiple SMR modules to a large-scale steam flow network for heat distribution, making the multi-modular scheme necessary for cogeneration. Consequently, adopting multi-modular scheme is essential for advancing SMRs as well as for benefiting the entire nuclear energy sector.

The multi-modular coordinated control plays a vital role in managing the couplings of process variables within individual reactor modules and across multiple modules. This mechanism regulates the control rod positions, helium blower speeds, feedwater pump rates and the openings of both main steam valve and bypass valve in a coordinated manner so that the process variables can be controlled to their expected setpoints. For the HTR-PM plant, the setpoints of nuclear power, helium flowrate and feedwater flowrate are determined by the module thermal power setpoint with those of hot helium temperature, steam temperature and main steam pressure are set constantly to be 553 °C, 520 °C and 11.0 MPa. Despite numerous theoretic analysis and forecasts presented in refs. 10,11,12,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, the practical verification of multi-modular scheme remains unachieved. Following the confirmation of commercial-scale inherent safety through loss of cooling tests18, the plant-wide tests of power-ramping, turbine trip and reactor scram were successively carried out on the HTR-PM plant to verify the multi-modular scheme with the relevant findings given in the section of results. The findings indicate that a well-designed automatic coordination mechanism can ensure stable operation for multi-modular SMR power plants, particularly for those featured by lower power density and greater thermal inertia, therefore verifying the approach of going multi-modular in the advancement of SMR technology.

From Fig. 6 showing the plant responses during the successive power ramping of two reactor modules, it can be seen that all the process variables are well controlled by the CCS in alignment with their designated setpoints, indicating a successful decoupling across the modules, i.e., the impact from one module undergoing power ramping on the stability of the other module operating at constant power is minimal. From Fig. 7 showing the responses in the scenario of turbine trip, the fast closure of main steam valve coupled with the resistance to open the bypass valve, results in a swift increase in main steam pressure, escalating from 11 to nearly 13 MPa, which subsequently causes a rapid decline in feedwater flowrate. Due to functioning of the CCS, pump #2 speeds up in an effort to maintain the flowrate. It can be seen from Fig. 7a, b that the feedwater flowrate of the #2 module is quickly recovered to operate at its designated setpoint with a negative overshoot of 15 kg/s or so. The rapid stabilization of feedwater flowrate effectively mitigates any impact to the primary loop. From Fig. 8 showing the responses in the event of reactor trip, the trip of reactor #1 causes the immediate closure of the inlet and outlet valves of steam generator #1, inducing a rapid drop in main steam pressure. This situation may subsequently lead to an increase in the feedwater flowrate of module #2. The CCS take measures to reduce the opening of main steam valve to recover the steam pressure, while also decreasing the rotational rate of feedwater pump #2 to mitigate the rise in feedwater flowrate. As presented in Fig. 8a, b, the main steam pressure ultimately achieves stabilization with a maximum deviation of 0.5 MPa, and the feedwater flowrate remains nearly unchanged throughout this significant transient. From the test results in the scenarios of power ramping, turbine trip and reactor trip, it can be concluded that the decoupling of reactor modules are effectively managed by the CCS, allowing the plant to mitigate single fault and ensuring the stable operation of multi-modular plant even in challenging situations such as the turbine trip and reactor trip.

The multi-modular scheme and the related coordinated control mechanism yields various advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness and operational efficiency. To achieve passive safety or inherent safety, there are strict limitations on the nuclear fuel inventory and power density of SMRs, giving a restrict rated reactor power. The multi-modular scheme can be implemented to achieve economic viability of passively safe or inherently safe SMRs through building SMR plants that meet any desired power specifications. It has been observed from our practice that the current power generation cost of the HTR-PM plant is approximately 20% greater than that of standard commercial PWR plants, however, this disparity can be mitigated by cogeneration and further by the batch production of reactor modules. The operation of SMR-based multi-modular NPPs significantly benefits from the flexibility offered by the multi-modular coordinated control mechanism. As we can see from the test results that, during power-ramping, it is possible to engage a selection of the reactor modules for power ramping, while allowing the remaining modules to continue operating steadily at constant power-levels. With greater number of reactor modules engaged in power ramping, the ramping rate of the electrical power output increases, giving improved load-following capability. The load-following capability of multi-modular SMR plants provides essential flexibility to balance the intermittent renewables, therefore contributing to economic viability of SMRs. In addition, the automation of the coordinated control system can reduce the workload on operators, thus establishing a robust foundation for minimizing the staff for further economic enhancement.

The HTR-PM plant received substantial and favorable policy support from the Chinese authorities. In fact, the research and development on mHTGR technology has been initiated by the INET of Tsinghua University since the end of 1970s. Following the achievement of attaining the first criticality of the HTR-10 test reactor in 2001, the HTR-PM project initiative was given a considerable priority within the Chinese Science and Technology Plan for the years 2006 to 2020. The project aims to develop, construct and operate a multi-modular high temperature gas-cooled reactor demonstration plant, laying a solid foundation for potential future commercialization. The implementation strategy and the financial plan of the HTR-PM initiative received the endorsement from State Council of China in February 2008, and the HTR-PM initiative received its conclusive approval from China’s cabinet approximately two weeks prior to the Fukushima accident in 2011. Given that the National Nuclear Safety Administration (NNSA) of China had gained substantial experience and insight regarding the mHTGR through licensing the HTR-10, and a structured regulatory framework for commercial mHTGR plants was systematically established. The NNSA granted the construction approval for the HTR-PM with the first concrete poured on December 9, 2012. The operation permit was issued on August 20, 2021, and the HTR-PM plant was connected to the grid on December 20, 2021. In 2023, nearly 400 licensing tests were accomplished, a sequence of regulation check was carried out by the NNSA, and the HTR-PM entered into its commercial operation on December 6, 2023 following a 168-hour demonstrating run. Once the HTR-PM plant was integrated into the grid, the research and development on the 600MWe multi-modular high temperature gas-cooled reactor commercial power plant known as HTR-PM600 commenced32,33, marking a pivotal moment for the commercialization of multi-modular mHTGR NPPs. In contrast to the commercial PWR plant such as the HPR100034,35 with main steam temperature being under 300 °C, the mHTGR plants HTR-PM and HTR-PM600 operate at significantly elevated steam temperatures nearly 520 °C, creating a beneficial interplay between market readiness of the HPR1000 and the HTR-PM600. In fact, the HPR1000 plants are deployable as reliable baseload power sources, while the HTR-PM600 plants are well-suited to be used as the clean heat sources for industrial processes.

The advancements in the multi-modular scheme and its associated coordinated control significantly shape the upcoming SMR designs. The multi-modular scheme is relevant not only for the mHTGR but also suitable for various reactor modules producing superheated steam. The multi-modular scheme allows for endowing the passive or inherent safety of individual SMRs to the large-scale NPPs with any desired power ratings. Moving forward, the objective of designing an individual SMR module is to achieve passive or even inherent safety while also enabling the production of superheated steam. Further, the aim of designing a multi-modular SMR nuclear plant is to integrate a number of SMR modules to the common steam turbine with an expected power rating, while simultaneously creating a coordinated control system to ensure stable and efficient operations. The advancement of multi-modular SMR plants, such as the HTR-PM and the HTR-PM600, plays a vital role in fostering global efforts towards decarbonization, requiring supportive policies and an appropriate regulation framework.

In a summary, the widespread deployment of inherently safe fission reactors is a necessary condition of the second nuclear era. The inherent safety can be achieved by restricting the power-density of reactor cores and their diameters, limiting the rated reactor power while resulting in the design of SMRs. As the commercial viability of inherent safety has been demonstrated by the loss-of-cooling tests conducted on the HTR-PM plant, another significant challenge lies in the development of large-scale NPPs based on multiple inherent safe SMRs. While the concept of utilizing multiple SMR modules to power shared turbines has been discussed for decades, its practical application had not been verified until the tests detailed in this study. The plant responses in the scenarios of power ramping, turbine trip and reactor trip are presented, demonstrating that a well-designed coordination mechanism can ensure stable operation of multi-modular NPPs in normal and typical abnormal scenarios. The findings confirm the pathway towards the utilization of multiple SMRs for developing large-scale NPPs. Given that the outlet steam temperature of mHTGR modules is approximately 520 °C, the multi-modular high temperature gas-cooled reactor plants hold great potentials as competitive industrial heat sources for those sectors challenging to decarbonize, including petrochemical processes and metallurgical industries. Based on the verification of multi-modular scheme and the related coordinated control on the HTR-PM plant, the INET is focusing on the development of 600 MWe multi-modular high temperature gas-cooled reactor plant known as HTR-PM600 for electricity generation and cogeneration. To address the challenges associated with the implementation of multi-modular SMR plants like the HTR-PM and the HTR-PM600, it is necessary to enhance the flexibility for effectively balancing the electric and thermal loads, along with improving the plant resilience to component malfunctions.

Methods

The process and equipment design of multi-modular NPPs is nearly the same as that of single modular NPPs. The major difference between the multi-modular and single modular NPPs focuses on the control and operation that is mainly provided by the CCS. The multi-modular coordinated control is the mechanism playing a central role in the realization of multi-modular scheme, giving the plant responses in normal and abnormal scenarios. In this section, the coordination mechanism inside a single reactor module and between two modules are proposed, giving the CCS design of HTR-PM plant.

Coordinated control of a single reactor module

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the cold helium is first pressurized by the helium blower, before being directed to the reactor along the annular cold gas duct. Once it is blended within the bottom region of the reactor, the cold helium ascends through the boreholes in the side reflector from to the upper section, subsequently circulating downwards through the pebble-bed reaching temperatures near 700 °C at the pebble bed’s outlet18. The bypassed cold helium is collected and combined with the hot helium flowing from the pebble-bed inside the hot gas plenum located in the bottom reflector. The mixed hot gas, exceeding 550 °C, is guided to the primary side of OTSG via the hot gas duct, transforming the secondary feedwater flow to the superheated steam flow. The coordinated control within a reactor module is designed to regulated the tightly coupled process variables including neuron flux, helium temperature and steam temperature of an individual mHTGR module, ensuring the closed-loop stability in the scenarios of power-level maintaining and maneuvering. Similar to36,37,38, the dynamic model of a reactor module for control design can be written as:

where P0 is the rated thermal power of reactor, Λ is the prompt neutron generation time, λ is the averaged decay constant of delayed precursors, β is the fraction of delayed neutrons, nr is the normalized neutron flux, cr is the normalized concentration of delayed neutron precursors, Gr is the control rod differential worth, zr is the total displacement of control rods, vr is the control rod speed, TR is the average temperature of reactor core with TR,m as its initial steady value, αR is the reactivity feedback coefficient of reactor core temperature, TH is the average primary helium temperature, TS is the average secondary coolant temperature of the steam generator, TSin is the coolant temperature at the secondary inlet of steam generator, MS is the secondary heat capacity flow, μR, μH and μS are the total heat capacities of reactor core, primary helium and secondary coolant respectively, ΩP and ΩS are respectively the heat transfer coefficient between the helium and pebble-bed and that between the two sides of steam generator.

Define δnr = nr-nr0, δcr = cr-cr0, δρr = ρr-ρr0, δTR = TR-TR0, δTH = TH-TH0, δTS = TS-TS0 and δTSin = TSin-TSin0, where nr0, cr0, ρr0, TR0, TH0, TS0 and TSin0 are the setpoints of process variables nr, cr, ρr, TR, TH, TS and TSin respectively. In addition, as δTSin is determined by the operational state of the conventional island, it is assumed that δTSin = 0 in the coordinated control design. Moreover, since the helium flowrate can be adjusted by the rotation rate of the primary helium blower, it is not loss of generality to assume that

where δGP is the variation of the primary helium flowrate with respect to the setpoint, ΩS0 is the value of heat transfer coefficient ΩS at the concerned setpoint, ΛS is a positive constant given by

with GP0 being the setpoint of primary helium flowrate.

Further, define

and then the nonlinear state-space model for control design can be written as

where

x and ξ are state-variables, u is the control input, and y is the measurement output. The following proposition gives the output-feedback coordinated control of a single reactor module, and the corresponding sufficient condition for globally asymptotic closed-loop stability.

Proposition 1

Consider nonlinear system (7) giving the dynamics of a mHTGR-based reactor module. The output feedback control given by

guarantees globally asymptotic closed-loop stability, if inequalities

are all well satisfied, where \({\bar{k}}_{{\rm{P3}}}={k}_{{\rm{P3}}}+1\), \({\delta }_{\gamma }=\gamma -{\bar{k}}_{{\rm{P3}}}\),and control gains kPi, kDj, kI3 and κi are all given postive constants (i = 1, 2, 3, and j = 1, 2).

Remark 1

By incorporating terms of x4 and its time-derivative into setpoint nr0, reactor control u1 in (11) can be implemented in a cascaded manner shown in Fig. 3. Steam temperature control u2 in (11) together with GP0 gives the final setpoint of helium flowrate, which is further controlled by regulating the rotation rate of helium blower. The steam temperature control u2 and helium flowrate control is also synthesized in a cascaded manner shown in Fig. 3. In addition, the inertia of helium blower can be compensated by enlarging gain kP3 in control law (11). As the difference between the dynamics of mHTGR module and that of other type reactor modules is limited, coordinated control (11) for a single mHTGR module is referenceable to the control other types of reactor modules.

Coordinate control method between two reactor modules

From Fig, 2, the two reactor modules are coupled by the common secondary loop system. The main coupling hydraulic dynamics in normal operation scenario can described by the fluid flow network (FFN) shown in Fig. 9, where branches f1 and f2 are the pump branches of #1 and #2 reactor modules composed of a feedwater pump and a high pressure heater (HPH), branches 1 and 2 are the feedwater the OTSG secondary sides of #1 and #2 modules respectively, and branch 3 is the fluid branch including the turbine, condenser, low pressure heaters (LPHs) and deaerator. The branches denoted by solid line constitute a tree of this FFN, while the branches denoted by dashed line are the links forming a co-tree. Nodes n1 and n2 represents the outlets of #1 and #2 HPHs respectively, node n3 is the inlet of common main steam header, node n4 represents the outlet of deaerator. The feedwater flowrates of #1 and #2 modules can be described by the flowrates of branches 1 and 2 respectively, and the main steam pressure can be represented by the pressure drop of tree branch 3.

Based on the fluid dynamics of pipelines, the flowrates in branches 1, 2 and 3 can be governed by

where Q = [Q1 Q2 Q3]T, H = [H1 H2 H3]T, QD = [Q12 Q22 Q32]T, L=diag([L1 L2 L3]T), R=diag([R1 R2 R3]T), Qi, Hi, Ri and Li are respectively the flowrate, pressure-drop, fluid resistance and fluid inertia of branches i (i = 1, 2, 3). In addition, the pressure-drops of pump branches fk (k = 1, 2), i.e. Hfk can be given by

where Hdk is the pressure header provided by #k pump being proportional to the square of rotation rate, Rfk is the resistance coefficient of pump branch fk, k = 1, 2.

By applying Kirchhoff’s current law (KCL) to node n3, it can be seen that

giving that

Substitute (16) to (19),

Then, apply Kirchhoff’s voltage law (KVL) to the fundamental loops,

From (17), (20) and (21), one can see that

where L = L1L2L3/(L1L2 + L2L3 + L3L1).

From (16), (22) and (23), the FFN dynamics is governed by nonlinear differential-algebraic system (DAS)

where Qc = [Q1 Q2]T, Hd = [Hd1 Hd2]T, QcD = [Q12 Q22]T, Rc = diag([R1 R2]T), Rf = diag([Rf1 Rf2]T), Lc = diag ([L1 L2]T), η = [1 1]T. From Fig. 1, the operation of two reactor modules can be decoupled if the feedwater flowrates are well regulated, and the main steam pressure is firmly stabilized, giving that the coordinated control between two modules is essentially the flowrate-pressure joint control of the FFN shown in Fig. 9. The flowrate-pressure joint control design can be further transferred to the control design of nonlinear DAS (24), and the following proposition gives an adaptive control for system (24) with the sufficient condition for globally asymptotical closed-loop stability.

Proposition 2

Consider nonlinear DAS (24) with Qcr = [Q1r Q2r]T and H3r being defined as the setpoints of Qc and H3 respectively. The joint controller

with \({\hat{{\bf{H}}}}_{{\rm{dr}}}\) and \({\hat{R}}_{3{\rm{r}}}\) given by adaptation law

provides globally asymptotic stability to setpoints if inequality

is well satisfied, where Qce = Qc-Qcr, H3e = H3-H3r, Q3r = Q1r + Q2r, Ωi = Ri(Qi+Qir) with i = 1, 2, 3, Ωc = diag([Ω1, Ω2]T), both Γa and Πa are given positive constants, and Γd, Πd and Λa are given positive-definite diagonal matrices.

Remark 2

It can be seen from (25) that the pressure header provided by #k pump are used to regulate the feedwater flowrate of #k reactor module (k = 1, 2), while the fluid resistance of tree branch such as the regulating value of turbine is applied for stabilizing the main stream pressure. Submit (26) to (25),

showing that the adaptive control laws are essentially distributed proportional-integral (PI) control algorithms. The two PI laws in (28) form the feedwater flowrate controllers of two modules and the main steam pressure controller shown in Fig. 3. Since the multiple reactor modules in a multi-modular NPP are coupled together by the common secondary FFN, coordinated control (28) can be also applicable to the coordination between all types of reactor module generating superheated steam.

Data availability

The data of process variable responses in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Weinberg, A. M. & Spiewak, I. Inherently safe reactors and a second nuclear era. Science 224, 1398–1402 (1984).

Ingersoll, D. T. Deliberately small reactors and the second nuclear era. Prog. Nucl. Energy 51, 589–603 (2009).

Vanatta, M., Stewart, W. R. & Craig, M. T. The role of policy and module manufacturing learning in industrial decarbonization by small modular reactors. Nat. Energy 10, 77–89 (2025).

L’Her, G. F., Kemp, R. S., Bazilian, M. D. & Deinert, M. R. Potentials for small and micro modular reactors to electrify developing regions. Nat. Energy 9, 725–734 (2024).

Gilbert, A. Q. & Bazilian, M. D. Can distributed nuclear power address energy resilience and energy poverty? Joule 4, 1839–1851 (2020).

Davis, S. J. et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 360, 6396 (2018).

Sepulveda, N. A., Jenkins, J. D., de Sisternes, F. J. & Lester, R. K. The role of firm low-carbon electricity resources in deep decarbonization of power generation. Joule 2, 2403–2420 (2018).

Cestelvecchi, D. Will AI’s huge energy demands spur a nuclear renaissance? Nature 365, 19–20 (2024).

Reutler, H. & Lohnert, G. H. The modular high-temperature reactor. Nucl. Technol. 62, 22–30 (1983).

Reutler, H. & Lohnert, G. H. Advances of going modular in HTRs. Nucl. Eng. Des. 78, 129–136 (1984).

Lohnert, G. H. Technical design features and essential safety-related properties of the HTR-Module. Nucl. Eng. Des. 121, 259–275 (1990).

Lanning, D. D. Modularized high temperature gas-cooled reactor systems. Nucl. Technol. 88, 139–156 (1989).

Wu, Z., Lin, D. & Zhong, D. The design features of the HTR-10. Nucl. Eng. Des. 218, 25–32 (2002).

Hu, S., Liang, X., & Wei, L. Commission and operation experience and safety experiment on HTR-10. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on High Temperature Reactor Technology, Johannesburg, South Africa, October 1–4, (2006).

Shiozawa, S., Fujikawa, S., Iyoku, T., Kunitomi, K. & Tachibana, Y. Overview of HTTR design features. Nucl. Eng. Des. 233, 11–21 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. The Shandong Shidao bay 200MWe high-temperature-gas-cooled reactor pebble-bed module (HTR-PM) demonstration plant: an engineering and technological innovation. Engineering 2, 112–118 (2016).

The World Nuclear News. China’s demonstration HTR-PM enters commercial operation. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Chinese-HTR-PM-Demo-begins-commercial-operation.

Zhang, Z. et al. Loss-of-cooling tests to verify inherent safety feature in the world’s first HTR-PM nuclear power plant. Joule 8, 2146–2159 (2024).

Gottaut, H. & Kugeler, K. Results of experiments at the AVR reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 121, 143–153 (1990).

Kim, K. K. & Bernard, J. A. Considerations in the control of PWR-type multimodular reactor plants. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 41, 2686–2697 (1994).

Perillo, S. R. P., Upadhyaya, B. R. & Li, F. Control and instrumentation strategies for multi-modular integral nuclear reactor systems. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 58, 2442–2451 (2011).

Dong, Z., Li, J., Zhang, Z., Dong, Y. & Huang, X. The definition of entropy production metric with application in passivity-based control of thermodynamic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 209, 115065 (2025).

Dong, Z. et al. Port-Hamiltonian control of nuclear reactors. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 69, 1022–1036 (2022).

Dong, Z. et al. Coordinated control of mHTGR-based nuclear steam supply systems considering cold helium temperature. Energy 198, 129299 (2024).

Dong, Z., Song, M., Huang, X., Zhang, Z. & Wu, Z. Module coordination control of MHTGR-based multi-modular nuclear plants. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 63, 1889–1900 (2016).

Dong, Z., Song, M., Huang, X., Zhang, Z. & Wu, Z. Coordination control of SMR-based NSSS modules integrated by feedwater distribution. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 63, 2691–2697 (2016).

Rowinski, M. K., White, T. J. & Zhao, J. Small and medium sized reactors (SMR): a review of technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 44, 643–656 (2015).

Berens, A., Bostelmann, F. & Brown, N. R. Equilibrium core modeling of a pebble bed reactor similar to the Xe-100 with SCALE. Prog. Nucl. Energy 171, 105187 (2024).

Cho, A. The little reactors that could. Science 363, 806–809 (2019).

Ingersoll, D. T., Houghton, Z. J., Bromm, R. & Desportes, C. NuScale small modular reactor for co-generation of electricity and water. Desalination 340, 84–93 (2014).

Paydar, A. Z., Balgehshiri, S. K. M., & Zohuri, B. Advanced Reactor Concepts (ARC): A New Nuclear Power Plant Perspective Producing Energy, Elsevier, 2023, pp. 1–3.

Zhang, Z., Dong, Y., Shi, Q., Li, F. & Wang, H. 600-MWe high temperature gas-cooled reactor nuclear power plant HTR-PM600. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 101 (2022).

Dong, Z., Pan, Y., Zhang, Z., Dong, Y. & Huang, X. Dynamical modeling and simulation of the six-modular high temperature reactor plant HTR-PM600. Energy 155, 971–991 (2018).

Xing, J., Song, D. & Wu, Y. HPR1000: advanced pressurized water reactor with active and passive safety. Engineering 2, 79–87 (2016).

Xing, J., Jing, C., Dong, Y. & Fan, L. Advanced PWR technology––HPR1000 and unit 5 of Fuqing nuclear power plant. Engineering 31, 31–36 (2023).

Dong, Z., Pan, Y., Zhang, Z., Dong, Y. & Huang, X. Model-free adaptive control law for nuclear superheated-steam supply systems. Energy 135, 53–67 (2017).

Dong, Z. Nonlinear coordinated control for MHTGR-based nuclear steam supply systems. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 61, 2643–2656 (2014).

Dong, Z. Adaptive proportional-differential power-level control for pressurized water reactors. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 61, 912–920 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study is jointly and equally supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62173202) and National S&T Major Project of China (Grant No. ZX069).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Z.D., Z.Z., L.S., X.H.; Methodology: Z.D., X.H., L.S.; Investigation: Z.D., X.H.; Visualization: Y.Z., Z.D.; Funding acquisition: Z.Z., Y.D., Z.Z.; Project administration: Z.Z., Y.D.; Writing – original draft: Z.D., Z.Y.; Writing – review & editing: Z.D., D.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Saeed A. Alameri and Michael A. Fütterer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Z., Zhang, Z., Dong, Y. et al. Testing the feasibility of multi-modular design in an HTR-PM nuclear plant. Nat Commun 16, 2778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58194-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58194-7