Abstract

All-solid-state Li metal batteries (ASSLMBs) promise superior safety and energy density compared to conventional Li-ion batteries. However, their widespread adoption is hindered by detrimental interfacial reactions between solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) and the Li negative electrode, compromising long-term cycling stability. The challenges in directly observing these interfaces impede a comprehensive understanding of reaction mechanisms, necessitating first-principle simulations for designing novel interlayer materials. To overcome these limitations, we develop a database-supported high-throughput screening (DSHTS) framework for identifying stable interlayer materials compatible with both Li and SSEs. Using Li3InCl6 as a model SSE, we identify Li3OCl as a potential interlayer material. Experimental validation demonstrates significantly improved electrochemical performance in both symmetric- and full-cell configurations. A Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2 cell exhibits an initial discharge capacity of 154.4 mAh/g (1.09 mA/cm2, 2.5–4.2 V vs. Li/Li+, 303 K) with 76.36% capacity retention after 1000 cycles. Notably, a cell with a conventional In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer delivers only 132.4 mAh/g and fails after 760 cycles. An additional interlayer-containing battery with Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 as the positive electrode achieves an initial discharge capacity of 151.3 mAh/g (3.84 mA/cm2, 2.5–4.2 V vs. Li/Li+, 303 K), maintaining stable operation over 1650 cycles. The results demonstrate the promise of the DSHTS framework for identifying interlayer materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Li-ion batteries power the modern world, from smartphones to electric vehicles1. However, the increasing demand for higher energy densities, enhanced safety, and extended lifespans necessitate the development of next-generation energy storage solutions. While Li metal negative electrode offer high energy storage capacity, their propensity for instability when combined with conventional liquid electrolytes raises significant safety concerns. All-solid-state Li-metal batteries (ASSLMBs) have emerged as a potential solution to this challenge2. ASSLMBs face significant hurdles to commercialization, including the low ionic conductivity of solid-state electrolytes (SSEs), suboptimal interfacial contact, and poor electrochemical compatibility. Despite extensive research, a battery architecture with sustained, long-term stability remains elusive. These challenges underscore the critical importance of developing systematic approaches to identify and optimize viable battery configurations. Conventional approaches, such as trial-and-error experimentation and resource-intensive density functional theory (DFT) calculations3, are inadequate. Rapid and accurate screening methodologies are crucial to accelerate the discovery of suitable interlayer materials and advance the development of ASSLMBs.

Halide SSEs are promising candidates for ASSLMBs due to their high ionic conductivity at room temperature (exceeding 1.5 mS cm−1 for compounds such as Li3InCl64, Li3YBr5.7F0.35, and 1.6Li2O-TaCl56), low Young’s modulus (indicating good interface contact7), electrochemical stability up to 4.3 V vs. Li+/Li8, and compatibility with commercial positive electrode materials, such as LiCoO2 and Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O29. Despite these advantages, halide SSEs exhibit inherent reactivity with Li metal5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, leading to uncontrolled interfacial reactions that degrade electrochemical performance and long-term stability15. Interfacial engineering, particularly introducing an interlayer between Li and the halide SSE, offers a promising avenue to circumvent the inherent instability arising from their direct contact. Previous studies have explored the use of interlayer materials, including polymer electrolyte poly(butylene oxide)17, sulfides like Li6PS5Cl18, and composite materials incorporating In and Li6PS5Cl4,6,7,9,11,19,20,21,22,23. However, these interlayer materials undergo continuous reactions with both the Li and the halide SSE, resulting in progressive interfacial resistance growth24 and shortened battery lifespan5,17. Although high-throughput screening studies have explored electrolyte-electrode stability and methods to mitigate interfacial reactions25,26,27,28,29, systematic investigations that simultaneously evaluate interlayer material compatibility with both the SSE and electrodes have yet to be conducted.

Utilizing Li3InCl6 as a model SSE, we sought an interlayer material demonstrating thermodynamic and electrochemical stability with Li and Li3InCl6, while possessing high Li+ conductivity and negligible electronic conductivity. Rapid database-supported high-throughput screening (DSHTS) of over 20,000 Li-containing compounds30 identified Li3OCl as a promising interlayer candidate due to its thermodynamic and electrochemical stability, Li+ conductivity of 0.48 mS cm−1 at 298 K and negligible electronic conductivity31. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed that Li3OCl forms a denser layer than Li3InCl6 on Li, supporting its suitability. Relative to conventional interlayers (i.e., Li6PS5Cl and In-Li6PS5Cl), Li3OCl significantly improved the critical current density (CCD) from 2.4 mA cm−2 to 4.2 mA cm−2. The corresponding symmetric cell cycled more than 2400 h at 1 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2, exceeding the 50 h achieved with the Li6PS5Cl interlayer and the 800 h of the In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer at 0.016 mA cm−2 and 0.016 mAh cm−2. Full cells utilizing the Li3OCl interlayer demonstrated significantly enhanced performance. Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2 cells with high positive electrode material mass loading (6.2 mg cm−2) maintained 76.4% capacity retention (117.9 mAh g−1) after 1000 cycles at 1 C (1.1 mA cm−2), while Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 cells sustained stable cycling for 1500 cycles at 3 C (3.84 mA cm−2) with ~50% capacity retention. These results represent a significant advancement over previously reported performance metrics for both Li3InCl6-based and other ASSLMB systems11,32,33,34,35,36,37,38.

In summary, the DSHTS framework rapidly identified Li3OCl as a promising interlayer material for Li3InCl6, establishing a streamlined screening approach for efficient material discovery. Experimental validation of Li3OCl’s efficacy demonstrated that this is a strategy that accelerates the development of high-performance ASSLMBs. Moreover, the versatility of the DSHTS framework is further demonstrated by recommending interlayers for other SSE-based ASSLMB systems, including those with Li3ScCl6, Li3YBr6, Li6PS5Cl, and Li10Ge(PS6)2 electrolytes.

Results and discussion

Database-supported high-throughput screening

We employed a DSHTS methodology, leveraging DFT calculations to rapidly and systematically identify stable interlayer materials for the Li|Li3InCl6 interface (Fig. 1). This DSHTS framework retrieved 21,576 Li-containing materials from the Materials Project database30. The selection of the interlayer candidates hinged on these four key criteria (further details can be found in Supplementary Note 1):

-

(1)

Thermodynamic Stability. To ensure against self-decomposition, materials with an energy above the convex hull (Ehull) below 25 meV atom−1 were considered39, and only those with a negative formation energy (Eform) from the constituent precursors were included.

-

(2)

Chemical Compatibility. To guarantee compatibility with both the Li and the SSE, materials exhibiting reaction energies (Ereact_Li with Li and Ereact_SSE with Li3InCl6 as calculated from the grand potential phase diagram40) above −0.25 eV atom−1 were selected.

-

(3)

Self-Limiting Reaction Behavior and Conductivity. Controlling electronic conductivity is crucial for limiting undesirable reactions. We implemented a band gap (Eg) threshold of 2.0 eV41 for both the candidate materials and their reaction products to ensure minimal electronic conductivity42.

-

(4)

Ionic conductivity (σLi+). To minimize the cell ohmic resistance, we set a minimum σLi+ threshold of 0.1 mS cm−143.

The framework consists of four sequential screening steps to identify promising interlayer material candidates. The gray, blue, yellow, and green sections represent the screening for thermodynamic stability, electrochemical stability, self-limiting reaction behavior, and ionic conductivity, respectively.

The determination of σLi+ through first-principles calculations is computationally challenging. Conversely, experimental measurements are time-consuming and expensive. Therefore, for the materials screened through up to the 3rd criterion, σLi+ was obtained from the literature. To enhance high-throughput screening efficiency, future work could integrate ionic conductivity predictions using artificial intelligence-based potentials44,45 and leverage experimental databases containing cross-validated Li+ conductivity measurements into the screening framework.

The 16 materials fulfilling the aforementioned criteria are presented in Supplementary Tables 1–2, with their corresponding reaction energies with Li and Li3InCl6 shown in Fig. 2a. Among these candidates, Li2S, Li2Se, and Li3OCl exhibit room-temperature ionic conductivities of 0.0146, 0.0147, and 0.85 mS cm−131. They also possess sufficiently wide electronic band gaps of 3.99 eV (Supplementary Fig. 1(c)), 4.08 eV48, and 4.70 eV49, respectively. However, Li2S and Li2Se are prone to react with moisture, potentially generating toxic gases, such as H2S and H2Se. While Li3OCl may react with moisture to form LiOH, Li2OHCl, and Li4(OH)3Cl50, its higher ionic conductivity and wide electronic band gap make it a more favorable interlayer material for the Li|Li3InCl6 interface compared to Li2S and Li2Se. Previous studies have confirmed that Li3OCl is compatible with Li metal51. Blending Li3OCl with Li6.75La3Zr1.75Ta0.25O12 lowered the interfacial impedance in full cells, which, in turn, improved cycling stability52. Furthermore, a hybrid electrolyte composed of Li3OCl and Li6PS5Cl stabilized a Li/Li(Ni0.7Co0.2Mn0.1)O2 battery system thanks to the wide electrochemical window of Li3OCl53.

a Reaction energies of the screened 16 materials with Li negative electrode and Li3InCl6. b The comparison of interface formation energies between the Li3OCl (100)|Li3InCl6 (100) and Li6PS5Cl (100)|Li3InCl6 (100) interfaces in conjunction with other interfaces54,55,56,57. c The radial distribution functions of Li-O, Li-Cl, Li-In, and O-In bonds at the Li3OCl (100)|Li3InCl6 (100) interface. Schematic illustrations of interface reactions of the (d) Li3OCl interlayer, and (e) conventional In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer.

A Li3OCl (100)|Li3InCl6 (100) interface model (Supplementary Fig. 2(a)) was constructed to analyze interfacial properties. The calculated interface formation energy for this interface is remarkably low, at 5.87 × 10−6 J cm−2 (Fig. 2b). This indicates substantially greater stability compared to the Li6PS5Cl (100)|Li3InCl6 (100) interface and other previously reported interfaces in ASSLMB systems, which range from 2.3 × 10−5 J cm−2 to 9.8 × 10−5 J cm−2 (Supplementary Table 354,55,56,57). Radial distribution functions (RDF) analysis was used to understand the atomic structure of the interface and corresponding bonding environment. As shown in Fig. 2c, the intensities of Li-Cl and Li-O bond RDF were computed to 33.2 atom Å−1 and 7.9 atom Å−1, respectively. Conversely, the intensities for Li-In and O-In bonds are only ~2 atoms Å−1, implying weak Li-In and O-In interactions at the interface. The weak Li-In and O-In interactions suggest that there is a limited amount of Li-In-O-containing compounds formed at the interface. As shown in Fig. 2d, DFT simulations (Supplementary Table 2) suggest that Li3OCl reacts with Li3InCl6 to form LiCl and LiInO2, while its reaction with Li metal yields Li2O and LiCl (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the electronically insulating nature of the reaction products at the Li|Li3OCl and Li3OCl|Li3InCl6 interface (band gaps exceeding 2.0 eV, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 3) causes the interfacial reactions to be self-limiting, which inhibits sustained side reactions and improves the overall stability of the solid-state battery.

The interface reactions of conventional In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer with Li/Li3InCl6 were also computed (Supplementary Figs. 1, 4, and Table 7) and studied experimentally (Supplementary Figs. 5–7), as shown in Fig. 2e. At the Li negative electrode side, when metallic In and Li come into contact, a Li-In alloy forms. This allows further reactions with Li6PS5Cl, generating In, Li2S, Li3P, and LiCl. The calculated reaction energy between LixIny alloys (x and y represent different ratios) and Li6PS5Cl are below -0.58 eV atom−1 (Supplementary Table 7), indicating higher reactivity relative to the reaction energy between Li and Li3OCl (-0.14 eV atom−1, Supplementary Table 1). At the Li3InCl6 side, there is a two-step degradation reaction, as combining Li6PS5Cl with Li3InCl6 results in the formation of LiCl, LiInS2, and Li3PS4. Subsequently, Li3InCl6 and Li3PS4 further react to form In, LiCl, LiInS2, and P2S7 (Supplementary Table 7). The presence of electron-conducting compounds (In and Li3P; Supplementary Table 6) at the interface drives continuous reactions that only stop when reactants are depleted. This progressive degradation results in an increased cell resistance (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

Electrochemical characterization of the interlayer

Li3OCl was synthesized as described in the “Methods” section. The corresponding X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern aligned well with both literature31 and first-principle simulations (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Due to the hygroscopic nature of Li3OCl, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis was conducted to evaluate sample purity. The absence of characteristic O-H stretching vibrations in the 1800-2500 and 3500-3800 cm−1 regions (Supplementary Fig. 8b)52,58 confirms the successful synthesis of phase-pure Li3OCl without detectable hydrated impurities such as Li2OHCl39 or Li4(OH)3Cl59. The room-temperature ionic conductivity of Li3OCl was measured to be 0.48 mS cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 9), consistent with the literature31.

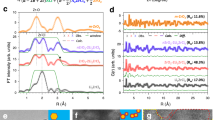

To evaluate the compatibility of Li3OCl with both the Li and Li3InCl6, Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li3OCl|Li symmetric cells were assembled. Figure. 3a shows the impedance evolution of this cell. Initially, the interfacial resistance was measured to be 690 Ω, followed by a slight increase to 720 Ω, and then, the resistance then significantly decreased to ~200 Ω within 24 h, stabilizing at 191 Ω (details can be found in Supplementary Fig. 10). The rapid decrease in interfacial resistance suggests interface stabilization through two processes: 1) the formation of a stable interfacial passivation layer and 2) the enhanced interfacial contact achieved under externally applied pressure ( ~1.5 tons). SEM analysis reveals the morphology of the interface changed from an initial two-phase structure containing voids to a homogeneously densified 7-μm-thick layer (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 10). In comparison, the impedance increase is more substantial for symmetric cells with Li6PS5Cl interlayer and In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer, such that even at low current densities (0.016 mA cm−2), the polarization voltage is up to 2 V, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5c. Further electrochemical characterization revealed that the cell’s CCD (4.2 mA cm−2, Fig. 3c) was considerably higher than the In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer (2.4 mA cm−2, Supplementary Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the symmetric cell could cycle stably for over 2400 h at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 (Fig. 3d).

a Time-dependent evolution of interfacial resistance in a Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li3OCl|Li symmetric cell. b Cross-sectional SEM micrograph of the Li3OCl|Li3InCl6 interface after 72-hour operation. c CCD determination via stepwise current polarization. d Extended galvanostatic cycling performance of the symmetric cell at 1 mA cm−2 with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. e ToF-SIMS analysis showing sputtering geometry (left) and three-dimensional ion distribution maps (O2−, In3+, InO+, and LiInO2+) at the Li3InCl6|Li3OCl|Li interface after 500-hour cycling (sputtering parameters: 1000 s duration, 250 × 250 μm2 area). f High-resolution XPS core-level spectra (Li 1s, O 1s, Cl 2p, and In 3d) of the cycled Li3OCl|Li3InCl6 interface, with relative peak intensities indicated by scale bars.

After 500 h of operation, the composition of the interface was analyzed using time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). The resulting ion map (Fig. 3e) acquired over a 250 μm × 250 μm area, reveals a distinct boundary between O2− and In3+. InO+ was detected within the overlapping region, in agreement with the predicted reaction products of LiInO2, In2O3, and InClO as determined by DFT calculations (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the intensities of O2− and In3+ were 2 orders of magnitude higher than those of InO+ and LiInO2+ (Supplementary Fig. 11). This observation suggests the occurrence of self-limiting reactions at the Li3OCl|Li3InCl6 interface. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of the Li3OCl|Li3InCl6 interface (Fig. 3f) revealed prominent Li 1s, O 1s, and Cl 2p peaks from the primary phases while showing markedly reduced In 3d signals, indicating minimal In-O bonds formed at that interface (peak intensity ratios shown in scale bars, lower left of each spectrum). This result aligns with the low intensity of the In-O bond observed in the RDF analysis (Fig. 2c) at the Li3OCl|Li3InCl6 interface, which implies a limited formation of In-O species at the interface. These findings collectively support the self-limiting nature of the electrochemical reactions at the interface, a critical factor contributing to the stable cycling performance of the cell.

The distinct interfacial stability behaviors of Li3OCl and In-Li6PS5Cl interlayers can be traced to the electronic properties of the corresponding reaction products. When Li3OCl reacts with Li/Li3InCl6, it forms an electrically insulating layer passivating at the interface. In contrast, In-Li6PS5Cl produces electronically conductive reaction products, which trigger continuous interfacial degradation until reactants are depleted.

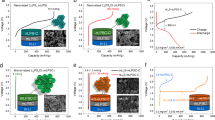

To evaluate the effectiveness of the Li3OCl interlayer in enhancing the long-term cycling performance of halide-based ASSLMBs, three cell configurations were assembled: i) Li|In-Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2 (control cell with LiCoO2 as the positive electrode material), ii) Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2 (with the Li3OCl interlayer and LiCoO2 as the positive electrode material), and iii) Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 (with the Li3OCl interlayer and Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 as the positive electrode material). All cells had a positive electrode material mass loading of 6.24 mg cm−2. As shown in Fig. 4a, the Li3OCl-based cell exhibited a significantly higher initial discharge capacity (154.4 mAh g−1) compared to the In-Li6PS5Cl control cell (132.4 mAh g−1), which is attributed to the lower electrochemical potential of Li metal relative to the Li-In alloy. Notably, after 1000 cycles, the cell incorporating the Li3OCl interlayer (Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2) retained 76.36% of its initial capacity, a substantial improvement over the control cell (Li|In-Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2), which exhibited only 5.21% capacity retention and presented a rapid capacity decline after 760 cycles (Fig. 4b).

a Initial galvanostatic charge-discharge profiles comparing Li|In-Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2 and Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|LiCoO2 cells at 1 C rate (1.1 mA cm−2). b Cycling stability and Coulombic efficiency of both cell configurations at 1 C rate over 1000 cycles. c First-cycle voltage profile of Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 cell at 3 C rate (3.8 mA cm−2). d Long-term cycling performance and Coulombic efficiency of the Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2-based cell at 3 C rate through 1500 cycles.

To assess its performance at high current densities, the Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 cell was subjected to cycling at a rate of 3 C (3.84 mA cm−2), nearing the CCD of 4.2 mA cm−2 measured in the symmetric configuration. This full cell delivered a high initial discharge capacity of 151.3 mAh g−1 and retained 64.73% of its initial capacity after 1000 cycles, cycling stably more than 1600 times (Fig. 4d). Supplementary Fig. 12 benchmarks our results against previous studies (further details are provided in Supplementary Tables 8 and 9). The Li3OCl interlayer enhances the electrochemical performance, as evidenced by the high CCD, surpassing previously reported results (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Moreover, its long-term cycling capacity retention (with the dots representing the maximum cycle number and corresponding capacity retention reported in the literature, Supplementary Fig. 12b) is superior to that of ASSLMBs based on other interlayer materials.

The DSHTS framework was further validated by extending its application to identify compatible interlayer materials for four additional Li-unstable SSEs, namely Li3ScCl6, Li3YBr6, Li6PS5Cl, and Li10Ge(PS6)2. For each SSE, the screening process identified over 40 candidate materials fulfilling the first three criteria outlined in Fig. 1 (detailed in Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Tables 10–17). Among these candidates, Li3OCl emerged as the optimal interlayer material for both Li|Li3ScCl6 and Li|Li3YBr6 interfaces, satisfying all four screening criteria. Additionally, Li2Se and Li2S showed promise as potential interlayers for Li|Li6PS5Cl and Li|Li10Ge(PS6)2 systems, meeting the first three criteria and approaching the fourth criterion with appreciable ionic conductivity (0.01 mS cm−1, Supplementary Table 6). These results demonstrate the DSHTS framework’s efficacy in rapidly identifying multiple viable solutions for enhancing the negative electrode stability in ASSLMBs across diverse SSE systems.

This study introduces a database-supported high-throughput screening framework to address interfacial instability in halide SSEs-based ASSLMBs by considering interlayer material’s compatibility with both Li and the SSE. Guided by first-principles calculations and validated experimentally, we identified Li3OCl as a promising interlayer material for Li3InCl6. The Li3OCl interlayer with a high ionic conductivity but a low electronic conductivity increased the critical current density of a Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li3OCl|Li symmetric cell from 2.4 mA cm−2 to 4.2 mA cm−2 and enabled corresponding symmetric cells to cycle stably for more than 2400 h. Furthermore, full cells with LiCoO2 and Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 as positive electrode materials demonstrated enhanced cycling stability under varying rates, retaining high capacity retention rates of 76.36% and 64.73%, respectively, after 1000 cycles. These results outperformed those from control cells without the interlayer, which retained only 5.21% of their capacity after 1000 cycles. The screening framework presented here can be readily adapted to identify stable interface materials for a variety of SSEs that react with Li metal. This work contributes meaningfully to the ongoing efforts to commercialize this promising technology, with the potential to usher in a new generation of safer, more powerful, and higher energy density energy storage solutions.

Methods

DFT calculations

DFT simulations were conducted using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)60. The projected augmented wave method61 with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation62 was used for all the calculations. For structural relaxation, energy and residual force convergence thresholds were set to 10−6 eV and 0.02 meV atom−1, respectively. The plane wave cutoff energy was set to 520 eV, and a proper Monkhorst-Pack k-mesh was employed (Supplementary Data and Legends for Supplementary Data). While the primitive cell of Li3InCl6 was obtained from experiments4, the primitive cells of Li3OCl and Li6PS5Cl were obtained from the Materials Project database (Material IDs: mp-985585 and mp-985592, respectively). The methods used to compute the interface formation energy are detailed in Supplementary Note 2. The Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen) package63 and the Materials Project API30 were used to analyze the convex hull, formation, and reaction energies with Li and the SSEs.

The atomic coordinates of structurally optimized models for density of states calculations, along with initial/final configurations of the Li3OCl (1 0 0)|Li3InCl6 (1 0 0) and Li6PS5Cl (1 0 0)|Li3InCl6 (1 0 0) interfacial models, are archived in Supplementary Data 8 and 9.

Materials preparation

Solid-state electrolytes

Li3InCl6 was synthesized using a stoichiometric ratio of 3:1 LiCl (Aladdin, ≥99%) and InCl3 (Aladdin, 99.99%). The precursors were thoroughly mixed by ball milling using a Retsch MM400 mixer mill at 25 Hz for 10 min in an Ar-filled ZrO2 grinding jar. The resulting mixture was loaded into a quartz crucible and heated to 533 K in a vacuum tube furnace following a temperature ramp of 5 K min−1. After holding at this temperature for 5 h4, the sample was cooled back to room temperature at a controlled rate of 3 K min−1. The synthesized Li3InCl6 was characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and its conductivity is presented in an Arrhenius plot (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Li3OCl was prepared using a similar approach. Stoichiometric quantities of LiOH (99.9%, Aladdin) and LiCl ( ≥99%, Aladdin) were mixed and milled following the same procedure. The mixture was then transferred to a quartz crucible and sintered in a vacuum tube furnace at 623 K for 72 h31. Maintaining a high vacuum (barometric pressure less than 0.03 bar) throughout the process was crucial for removing any water vapor produced, as its presence could introduce impurities.

All the synthesis processes were conducted in an Ar-filled (≥99.999 %, Air Products) glovebox (Mikrouna, Super 1220/750) with O2 and H2O concentrations maintained below 0.01 ppm.

Li6PS5Cl was purchased from Zhejiang Fengli New Energy Technology Co., Ltd.

Electrodes

The 20 μm thick Li foil and In foil were purchased from China Energy Lithium Co., Ltd and Fuxiang Metal Materials Co., Ltd, respectively. LiCoO2, Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2, and super P were purchased from Canrd Co., Ltd. The composite positive electrode was prepared by mixing Li3InCl6, LiCoO2/Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2, and super P with a mass ratio of 3:7:0.05 with a Retsch MM400 mixer mill at 25 Hz for 10 min. All processes were conducted in an Ar-filled (≥99.999%, Air Products) glovebox (Mikrouna, Super 1220/750) with O2 and H2O concentrations maintained below 0.01 ppm.

Materials characterization

XRD was detected via a PANalytical Empyrean Pro-diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in the 2θ range from 10 to 90°. Surface composition of cycled electrodes and interfaces were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI5600). Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker ALPHA spectrometer. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were performed using a JEM 6700 F microscope. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) was conducted on an IonTof M6 analyzer employing thermal ionization Cs+ as the primary ion source.

To prevent atmospheric exposure, samples for XRD and FTIR measurements were sealed within an Ar-filled holder. Samples from cycled batteries, which were initially disassembled in an Ar-filled glovebox, were transferred to the XPS, SEM/EDX, and ToF-SIMS instruments via a transfer vessel.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted on a BioLogic VSP-300 electrochemical workstation using stainless steel rods as blocking electrodes. Measurements spanned a frequency range of 1 Hz to 7 MHz with an AC amplitude of 10 mV and 6 points per decade. 150 mg of either Li3InCl6 or Li3OCl powder was compressed into 10 mm diameter pellets in a polyether ether ketone (PEEK) mold at a pressure of 2 tons and secured with bolts to obtain a dense pellet. Then, the mold was sealed with rubber rings and brought out of the glovebox for EIS characterization.

To assess the electrochemical compatibility of various interlayers with Li and Li3InCl6, symmetric cells were assembled in the following configurations: Li|Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|Li6PS5Cl|Li, Li|In-Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|Li6PS5Cl-In|Li, and Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li3OCl|Li. For cell preparation, 90 mg of Li3InCl6 powder was initially compressed within a 10 mm diameter PEEK mold at 1.5 tons of pressure for 1 min. Subsequently, 30 mg of either Li6PS5Cl or Li3OCl powder was uniformly distributed on both sides of the Li3InCl6 pellet and subjected to the same pressure for 1 min. For the Li6PS5Cl and Li3OCl interlayers, a 9 mm diameter, 20 μm thick Li foil disk was directly attached. For the In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer, a 10 mm diameter, 20 μm thick In foil disk was positioned on the Li6PS5Cl interlayer, followed by a 9 mm diameter, 20 μm thick Li foil disk. The assembly was then compressed at 1.5 tons for 1 min and secured with bolts. The resulting cells were cycled using a CT2001A battery cycling system (LANHE) within a temperature chamber (ESPEC, SU-242-5) maintained at 303 ± 1 K. CCD measurements were performed on symmetric cells using stepwise increasing current densities, with a fixed plating/stripping duration of 1 h per step. Long-term cycling tests of symmetric cells were conducted at 1.0 mA cm−2 for Li|Li3OCl|Li3InCl6|Li3OCl|Li cell, and at 1.6 × 10−2 mA cm−2 for both the Li|Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|Li6PS5Cl|Li and Li|In-Li6PS5Cl|Li3InCl6|Li6PS5Cl-In|Li cells. The assembly of solid-state batteries followed a procedure analogous to that of the symmetric cells. Initially, 90 mg of Li3InCl6 powder was compressed uniaxially in a PEEK mold for 1 min at a pressure of 1.5 tons. Subsequently, 30 mg of either Li6PS5Cl or Li3OCl powder underwent identical compression on one side of the Li3InCl6 pellet. For cells incorporating the In-Li6PS5Cl interlayer, In foil was sandwiched between the Li6PS5Cl and the Li foil. For cells with the Li3OCl interlayer, a piece of Li foil was directly attached to the Li3OCl. Lastly, 7 mg of composite positive electrode powder (with a corresponding positive electrode material mass loading of 6.24 mg cm−2) was uniformly distributed on the opposite side of the Li3InCl6 pellet to the Li foil. The assembled cell was then pressed uniaxially at 1.5 tons for 1 min. Following this step, the assembled cell was cycled at 303 K under the corresponding strain state, which was maintained by mechanically constraining the cell with stainless steel casing and bolts. A stack pressure of 1.5 tons (187.5 MPa) was applied, and this value was benchmarked against the literature (Supplementary Table 18). All assembly took place within an Ar-filled (≥99.999%, Air Products) glovebox (Mikrouna, Super 1220/750) with O2 and H2O concentrations below 0.01 ppm. Cells were cycled using a LANHE CT2001A battery tester within an ESPEC, SU-242-5 temperature chamber, maintained at 303 ± 1 K. All batteries were cycled with a voltage window of 2.5-4.2 V (vs. Li/Li+). Cycling currents were 0.85 mA (1 C, 1.09 mA cm−2) for LiCoO2 positive electrode, and 3.01 mA (3 C, 3.84 mA cm−2) for Li(Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1)O2 positive electrode.

At least three full cells of each configuration were assembled and tested to ensure the reliability of the results and reproducibility. Representative data, selected for both capacity and cycle stability, are presented here; the cycling performance of the remaining cells is shown in Supplementary Fig. 15.

Declaration of the use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that the large language model Claude 3.5 Sonnet was utilized to streamline the language of this manuscript. Following the use of this tool, the authors thoroughly reviewed and revised the content as necessary. Dr. Mark Ellwood (Cantab) further refined the manuscript for clarity, grammatical correctness, and language accuracy. The authors assume full responsibility for the final content of the published article.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Data, and Source Data file. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Manthiram, A., Yu, X. & Wang, S. Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16103 (2017).

Bonnick, P. & Muldoon, J. The quest for the holy grail of solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 1840–1860 (2022).

Li, S., Chen, Z., Zhang, W., Li, S. & Pan, F. High-throughput screening of protective layers to stabilize the electrolyte-anode interface in solid-state li-metal batteries. Nano Energy 102, 107640 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Air-stable Li3InCl6 electrolyte with high voltage compatibility for all-solid-state batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2665–2671 (2019).

Yu, T. et al. Superionic fluorinated halide solid electrolytes for highly stable Li‐metal in all‐solid‐state Li batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101915 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. A family of oxychloride amorphous solid electrolytes for long-cycling all-solid-state lithium batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 3780 (2023).

Li, F. et al. Amorphous chloride solid electrolytes with high Li-ion conductivity for stable cycling of all-solid-state high-nickel cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27774–27787 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Progress and perspectives on halide lithium conductors for all-solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 1429–1461 (2020).

Hu, L. et al. A cost-effective, ionically conductive and compressible oxychloride solid-state electrolyte for stable all-solid-state lithium-based batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 3807 (2023).

Wang, C., Liang, J., Kim, J. T. & Sun, X. Prospects of halide-based all-solid-state batteries: from material design to practical application. Sci. Adv. 8, eadc9516 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. A cost-effective and humidity-tolerant chloride solid electrolyte for lithium batteries. Nat. Commun. 12, 4410 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Lithium chlorides and bromides as promising solid-state chemistries for fast ion conductors with good electrochemical stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8039–8043 (2019).

Riegger, L. M., Schlem, R., Sann, J., Zeier, W. G. & Janek, J. Lithium-metal anode instability of the superionic halide solid electrolytes and the implications for solid-state batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 6718–6723 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Revealing the impact of Cl substitution on the crystallization behavior and interfacial stability of superionic lithium argyrodites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2207978 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Solid-state plastic crystal electrolytes: effective protection interlayers for sulfide-based all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900392 (2019).

Li, S. et al. A dynamically stable mixed conducting interphase for all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307768 (2024).

Luo, J. et al. Rapidly in situ cross-linked poly(butylene oxide) electrolyte interface enabling halide-based all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 3676–3684 (2023).

Ma, T. et al. High-areal-capacity and long-cycle-life all-solid-state battery enabled by freeze drying technology. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2142–2152 (2023).

Luo, X. et al. A novel ethanol-mediated synthesis of superionic halide electrolytes for high-voltage all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 29844–29855 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Water-mediated synthesis of a superionic halide solid electrolyte. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16427–16432 (2019).

Hu, L. et al. Revealing the Pnma crystal structure and ion-transport mechanism of the Li3YCl6 solid electrolyte. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 4, 101428 (2023).

Kochetkov, I. et al. Different interfacial reactivity of lithium metal chloride electrolytes with high voltage cathodes determines solid-state battery performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 3933–3944 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. New insights into aliovalent substituted halide solid electrolytes for cobalt-free all-solid state batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 5136–5143 (2023).

Rosenbach, C. et al. Visualizing the chemical incompatibility of halide and sulfide‐based electrolytes in solid‐state batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203673 (2022).

Sendek, A. D. et al. Holistic computational structure screening of more than 12 000 candidates for solid lithium-ion conductor materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 306–320 (2017).

Muy, S. et al. High-throughput screening of solid-state Li-ion conductors using lattice-dynamics descriptors. iScience 16, 270–282 (2019).

Honrao, S. J. et al. Discovery of novel Li SSE and anode coatings using interpretable machine learning and high-throughput multi-property screening. Sci. Rep. 11, 16484 (2021).

Richards, W. D., Miara, L. J., Wang, Y., Kim, J. C. & Ceder, G. Interface stability in solid-state batteries. Chem. Mater. 28, 266–273 (2015).

Aykol, M. et al. High-throughput computational design of cathode coatings for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 7, 13779 (2016).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Zhao, Y. & Daemen, L. L. Superionic conductivity in lithium-rich anti-perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15042–15047 (2012).

Kwak, H. et al. Boosting the interfacial superionic conduction of halide solid electrolytes for all-solid-state batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 2459 (2023).

Yin, Y. C. et al. A LaCl3-based lithium superionic conductor compatible with lithium metal. Nature 616, 77–83 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. A universal wet-chemistry synthesis of solid-state halide electrolytes for all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh1896 (2021).

Dai, T. et al. Inorganic glass electrolytes with polymer-like viscoelasticity. Nat. Energy 8, 1221–1228 (2023).

Wan, H., Wang, Z., Zhang, W., He, X. & Wang, C. Interface design for all-solid-state lithium batteries. Nature 623, 739–744 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Lithium anode interlayer design for all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 9, 251–262 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Single-phase local-high-concentration solid polymer electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 9, 386–400 (2024).

Shen, L. et al. Strain engineering of antiperovskite materials for solid-state Li batteries: a computation-guided substitution approach. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 18984–18995 (2023).

Zhu, Y., He, X. & Mo, Y. First principles study on electrochemical and chemical stability of solid electrolyte-electrode interfaces in all-solid-state Li-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 3253–3266 (2016).

Yoshikawa, A., Matsunami, H. & Nanishi, Y. Development and Applications of Wide Bandgap Semiconductors. In: Wide Bandgap Semiconductors: Fundamental Properties and Modern Photonic and Electronic Devices. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007).

Ren, F. et al. The nature and suppression strategies of interfacial reactions in all-solid-state batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2579–2590 (2023).

Cyriac, V. et al. Ionic conductivity enhancement of PVA: carboxymethyl cellulose poly-blend electrolyte films through the doping of nai salt. Cellulose 29, 3271–3291 (2022).

Barroso-Luque, L. et al. Open materials 2024 (OMat24) inorganic materials dataset and models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.12771 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. MatterSim: a deep learning atomistic model across elements, temperatures and pressures. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.04967 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Uniform high ionic conducting lithium sulfide protection layer for stable lithium metal anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900858 (2019).

Yang, W. et al. Li2Se: a high ionic conductivity interface to inhibit the growth of lithium dendrites in garnet solid electrolytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 50710–50717 (2022).

Shi, H., Du, M.-H. & Singh, D. J. Li2Se:Te as a neutron scintillator. J. Alloy. Compd. 647, 906–910 (2015).

Lu, Z., Liu, J. & Ciucci, F. Superionic conduction in low-dimensional-networked anti-perovskites. Energy Storage Mater. 28, 146–152 (2020).

Effat, M. B. et al. Stability, elastic properties, and the Li transport mechanism of the protonated and fluorinated antiperovskite lithium conductors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 55011–55022 (2020).

Yang, Y., Han, J., Devita, M., Lee, S. S. & Kim, J. C. Lithium and chlorine-rich preparation of mechanochemically activated antiperovskite composites for solid-state batteries. Front Chem. 8, 562549 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. Li6.75La3Zr1.75Ta0.25O12@Amorphous Li3OCl composite electrolyte for solid state lithium-metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 14, 49–57 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Synergistic Li6PS5Cl@Li3OCl Composite electrolyte for high-performance all-solid-state lithium batteries. Green Energy & Environment, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gee.2024.07.001 (2024).

Hao, H. et al. Tuned reactivity at the lithium metal–argyrodite solid state electrolyte interphase. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301338 (2023).

Wan, H. et al. Interface design for high‐performance all‐solid‐state lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303046 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. A self-regulated gradient interphase for dendrite-free solid-state Li batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 1325–1333 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Interrelated interfacial issues between a Li7La3Zr2O12-based garnet electrolyte and Li anode in the solid-state lithium battery: a review. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 5952–5979 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Reaction mechanism studies towards effective fabrication of lithium-rich anti-perovskites Li3OX (X=Cl, Br). Solid State Ion. 284, 14–19 (2016).

Nangir, M., Massoudi, A. & Omidvar, H. Super Ionic Li3-2xMx(OH)1-yNyCl (M=Ca, W, N=F) halide hydroxide as an anti-perovskite electrolyte for solid-state batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 170, 080512 (2023).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python materials genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Computational Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong for support through the projects (16201820 and 16201622). The authors are grateful to the Materials Characterization and Preparation Facility (MCPF) of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou) for their assistance in experimental characterizations. The authors thank the HKUST Fok Ying Tung Research Institute and National Supercomputing Center in Guangzhou Nansha sub-center for providing high-performance computational resources. FC thanks the University of Bayreuth and the Bavarian Center for Battery Technology (BayBatt) for providing start-up funds. This project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 533115776. Support from the BayBatt Cell Technology Center is gratefully acknowledged as funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – INST 91/452-1 LAGG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. and F.C. conceived this research project and wrote the manuscript. L.S. performed the simulations and experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the initial draft. F.C. supervised the study, designed the work, and led the subsequent writing and revision of the manuscript. Z.W., H.M.L., S.X., and Y.Z. contributed to the discussions and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Qiang Xu, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, L., Wang, Z., Xu, S. et al. Harnessing database-supported high-throughput screening for the design of stable interlayers in halide-based all-solid-state batteries. Nat Commun 16, 3687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58522-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58522-x