Abstract

Heterodimeric ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters containing one catalytically impaired degenerate nucleotide-binding site (NBS) have a mechanism different from those with two active NBSs. However, the structural basis of their transport mechanism remains to be explained. Here, we determine mycobacterial MsRv1273c/72c to be an isoniazid efflux pump and determine several structures by cryo-electron microscopy showing specific asymmetrical features including an N-terminal extending loop and a periplasmic helical hairpin only found in MsRv1272c. In addition, we capture three distinct asymmetric states where the nucleotide-binding domains are partially dimerized at the degenerate site. Using these intermediate states, the D-WalkerB loop and X-signature loop of MsRv1272c modulate and couple the function of both NBSs through conformational changes. Thus, these data provide insights into the mechanism of this heterodimeric ABC transporter containing a degenerate NBS. The structures also provide a framework for the rational design of anti-tuberculosis drugs targeting this drug-efflux pump.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by the pathogenic bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), kills around 1.7 million people each year1. The current recommended treatment for TB involves a combination of four antibiotics: isoniazid (INH; targeting InhA2), rifampicin (RIF; targeting RNA polymerase3), pyrazinamide (PZA; target unknown) and ethambutol (EMB; targeting EmbA/B/C4), which were all discovered nearly 70 years ago5. However, these drugs are becoming less effective against Mtb where resistance has developed, either by site of action changes, or the emergence of metabolism modifying enzymes or efflux pumps. Hence, new targets and drugs to treat TB are urgently needed, or where drug resistance has developed a better understanding of the molecular basis for this needs to be developed. One possible class of proteins important for drug resistance are the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and these are found in all kingdoms of life6. However, they are structurally and functionally diverse and have not been fully characterized. These transporters use the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to transport an astonishing variety of substrates including small ions, lipids, peptides, and proteins across membranes7,8,9,10. All ABC transporters are built from common structural modules comprising two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs), which bind and hydrolyze ATP, and two transmembrane domains (TMDs) that facilitate substrate translocation11,12. The binding and hydrolysis of ATP induces association and dissociation between the NBDs. This results in conformational changes of the TMDs that are likely transmitted through the coupling helices (CpHs)13. Consequently, the substrate binding cavity (central cavity) between the two TMDs will open either towards the cytoplasmic side (inward facing, IF) or towards the periplasmic side (outward facing, OF) of the cell membrane, or be occluded (Occ) from both sides.

Transporters with two active nucleotide-binding sites (NBSs) are referred to as canonical transporters, while heterodimeric ABC exporters frequently have both a degenerate NBS and a consensus NBS. Compared to the consensus site with active ATPase activity, the degenerate site contains non-canonical residues that strongly impair ATP hydrolysis14. Thus, the proposed models of transport cycle for the canonical transporters are not compatible with a ‘degenerate’ transporter, because these models (a) require the normal hydrolysis of two ATPs for one cycle, (b) an obligate alternation of ATP hydrolysis between the two NBSs, or (c) impose complete NBD separation14. These ‘degenerate’ transporters must therefore have established a distinct mechanism, in which the degenerate NBS sustains active substrate translocation across a biological membrane14. Indirect evidence suggested that ATP might act as a glue in the degenerate site, keeping this NBS in a closed conformation over several iterations of the transport cycles15,16,17,18,19. Mutagenesis data suggested that ATP hydrolysis in the consensus site is sufficient for all necessary conformational changes to complete a transport cycle, but subsequent hydrolysis of ATP in the degenerate site would favor NBD opening20. Several biochemical and structural investigations have been undertaken on this type of ABC exporters including TM278/28821,22,23, TmrAB24,25, TAP26 and CFTR27,28,29. However, the detailed mechanism and why these transporters have an impaired NBS remains unclear. Therefore, more structural evidence is required to explain the exact role of the degenerate site during the process of transport. The degenerate sites of different transporters often have unique residue substitutions30, thus, this site may prove to be a good target for the design of highly specific drugs20.

The genes encoding ABC transporters occupy about 2.5% of the genome of Mtb31. Among them, rv1273c and rv1272c are arranged in tandem. Their coding proteins, Rv1273c and Rv1272c, are TMD-NBD fusion proteins and they are predicted to form a heterodimeric ABC exporter31. However, Rv1272c is hypothesized to function as a homodimer. Interestingly, it has been shown to enhance the transport of long-chain fatty acids when expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli)32. Rv1273c has 28% sequence identity with Rv1272c32 and is capable of modulating cell wall lipid composition, promoting mycobacterial survival within macrophages and in affecting the host cell immune response33. It has also been proposed as a contributor to biofilm formation34. However, whether Rv1273c interacts with Rv1272c to function together as a transporter has remained unknown. Based on their sequences, Rv1273c and Rv1272c have been annotated as multidrug transporters31. Expression and mutation analysis of drug resistant clinical isolates of Mtb showed that Rv1273c is associated with resistance to drugs such as isoniazid35, ethambutol36 and bedaquiline37. An analysis of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) clinical isolates of Mtb revealed common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in Rv1273c such as S118G and I175T, which are believed to be associated with drug resistance caused by Rv1273c38. Another cell-based study also indicated that Rv1273c acts as a multidrug efflux pump targeting a wide range of antibiotics34. Given their critical importance, Rv1273c and Rv1272c are thus potential targets for the treatment of TB and for mitigating the effects of drug resistance. However, currently, little is known about the molecular mechanism as to how Rv1273c and Rv1272c function as transporter proteins.

MsRv1273c (MSMEG_5008) and MsRv1272c (MSMEG_5009) from Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm) are close homologs of Rv1273c and Rv1272c, respectively, sharing 69% and 75% sequence identities with their Mtb counterparts. We focus on the Msm homologs because they could be successfully expressed and purified with good quality while this is not possible for the Mtb proteins. Here, we purify the active MsRv1273c/72c (complex of MsRv1273c and MsRv1272c) transporter as a heterodimer, confirm its role as a drug efflux pump of isoniazid, and determine its cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures in the apo / AMPPNP-bound / ADP-bound / ATP | ADP-bound IF states and the ATP-bound / ATP | ADP+Vi-bound Occ states. Importantly, we capture three types of asymmetric conformations as intermediate states that have not been previously reported for any of the ABC superfamily. With these data, the mechanism of degenerate NBS mediated transport by a heterodimeric ABC exporter is proposed.

Results

Characterization and functional analysis of MsRv1273c/72c

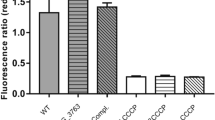

Rv1273c and Rv1272c, as well as MsRv1273c and MsRv1272c, were tandemly expressed in Msm cells and then purified in digitonin as a complex with a Flag-tag or 6×His-tag fused at the C-terminus of Rv1272c and MsRv1272c, respectively. Gel filtration and SDS-PAGE showed that the two subunits form a heterodimer with 1:1 stoichiometry (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Since the sample quality of Rv1273c/72c was poor due to low yields and impurities, it was difficult to perform biochemical and structural studies. We therefore focused on MsRv1273c/72c. To prove that MsRv1273c/72c can undertake ATP hydrolysis, an ATPase activity assay was performed. The results showed that it has basal ATPase activity of 113.3 ± 13.9 nM Pi min–1 mg–1 (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3), 181.2 ± 2.3 nM Pi min–1 mg–1 and 147.9 ± 2.4 nM Pi min–1 mg–1 in detergent, proteoliposomes and peptidiscs, respectively (Fig. 1a). These data show that MsRv1273c and MsRv1272c are able to form an active heterodimeric transporter.

a The ATPase activity of MsRv1273c/72c in detergent, proteoliposomes and peptidiscs. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M., calculated from three biologically independent experiments (n = 3). b Sequence alignment of the Walker B motif and Switch-loop for Rv1272c, Rv1273c from Mtb (Mt) and Msm (Ms), and other representative ABC transporters including TmrAB from Thermus thermophilus (Tt), TM_0287/88 from Thermotoga maritima (Tm) and MsbA from E. coli (Ec). The crucial sequence variations between the degenerate and consensus sites are highlighted in orange. c The ATPase activity of MsRv1273c/72c and mutants. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M., calculated from three biologically independent experiments (n = 3). P values were calculated using an unpaired two-sided t test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. Wild Type vs D497N, P = 0.57. d A scheme of proteoliposomes-based transport assay after which the contents inside the liposomes were isolated and analyzed by MS or LC-MS/MS method. e Mass spectrometry was used to determine the contents inside the liposomes with wildtype MsRv1273c/72c (WT), or with the E553Q/D497N double mutant (EQ&DN) inserted, and liposomes without any protein added. Pure isoniazid (INH) was also measured as a standard. The red circle indicates the expected mass/charge of the drug. f The transport rate of varying concentrations of isoniazid supplied outside the proteoliposomes. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M., calculated from three biologically independent experiments (n = 3). g Growth curves of wild type Msm (WT-Msm), MsRv1273c/72c knockout strain (∆MsRv1273c/72c), and complemented strain containing pMV261-MsRv1273c/72c (∆+MsRv1273c/72c) in the presence or absence of isoniazid. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M., calculated from three biologically independent experiments (n = 3).

Sequence alignment of NBDs of MsRv1273c/72c with other ABC transporters showed that Glu553 in the Walker B motif of MsRv1272c is a conserved catalytic residue, which is responsible for activating the attacking water molecule during ATP hydrolysis39. Another conserved residue, His584, in the Switch-loop of MsRv1272c plays a central role in stabilizing the transition state of the reaction40. However, the corresponding residues in MsRv1273c are replaced by Asp497 and Gln528, respectively (Fig. 1b). Thus, MsRv1273c should have a degenerate site impaired for ATPase activity while MsRv1272c has a functional consensus site with the classic enzymatic motifs. Based on this analysis, we performed a mutagenesis study and used an ATPase activity assay to verify the roles of the expected catalytic residues (e.g., E553 acts as a catalytic base?). The result shows that the E553Q mutation at the consensus site significantly diminishes ATP hydrolysis, consistent with mutagenesis experiments for other ABC transporters where E has been changed to Q21,41. This confirms that Glu553 is crucial for ATPase activity in MsRv1273c/72c. Note that this mutant has some residual activity (Fig. 1c), this is likely because Asp497 at the degenerate site can still slowly hydrolyze ATP. Since the side chain of Asp497 is shorter than Glu, but can still act as a base, it may not be ideal for optimal catalysis. In contrast, the D497N mutant did not show a significant loss of ATPase activity compared to the wild-type transporter (Fig. 1c). This is because Glu553 is still fully functional at the consensus site. Confirmation that this is correct was achieved by mutating both E553Q and D497N, creating the double mutant, which has little activity (Fig. 1c). Together, these results indicate that the consensus site of MsRv1273c/72c is functional with normal ATPase activity while its degenerate site exhibits very low activity.

Since Rv1273c and Rv1272c could potentially play a part in the resistance mechanism for drugs such as isoniazid and ethambutol, we first tested their effects on ATP hydrolysis using the MsRv1273c/72c complex. In this experiment, neither drug affected ATPase activity significantly (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d), this may be due to their weak binding, which is commonly observed for a non-physiological substrate. Next, we established a transport assay to determine whether isoniazid or ethambutol could be imported into proteoliposomes containing MsRv1273c/72c (Fig. 1d). Mass spectrometry detected isoniazid inside the liposomes when the wildtype transporter was inserted into the liposomes, while there was no detectable isoniazid inside the liposomes when the ATPase inactive mutant was used (Fig. 1e). When ethambutol was tested, it was not detected inside the liposomes in any of the experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1g). These results confirmed that MsRv1273c/72c is able to transport isoniazid but not ethambutol. Further analysis by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) showed that isoniazid is transported by MsRv1273c/72c in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1d and f). In agreement with this, Msm culture growth experiments showed that knocking out of MsRv1273c/72c resulted in an increase in growth inhibition when isoniazid was added, while complementation of MsRv1273c/72c in the knockout strain eliminated such a growth difference in the presence of isoniazid (Fig. 1g). These results confirm that MsRv1273c/72c is involved in resistance to isoniazid. However, no growth difference was observed in all these strains in the presence of ethambutol (Supplementary Fig. 1h), which suggests that MsRv1273c/72c is not sensitive to ethambutol. Thus, MsRv1273c/72c is a drug efflux pump for isoniazid, but not ethambutol. Therefore, its Mtb counterpart is a likely factor contributing to isoniazid resistance in Mtb.

Structure in the IFapo state

Using single-particle 3D reconstruction, the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c was determined at 3.1 Å resolution in the IFapo state (Supplementary Fig. 2 and 11a). The overall fold of the MsRv1273c/72c complex (Fig. 2a) belongs to the type IV family of ABC transporters (or type I ABC exporter) with a seven-type classification42. The central cavity is located between the two TMDs and it opens towards the cytoplasm (Fig. 2b). The two NBDs are separate at both NBSs (Fig. 2c). However, interactions are maintained between the two NBDs at their C-terminal helices (Fig. 2a). In the heterodimer, MsRv1272c and MsRv1273c share a similar fold (Fig. 2d). Superposition shows that the r.m.s.d. between the two subunits is 2.59 Å for 413 pairs of Cα atoms, suggesting there are significant differences in the two subunits. We observe that the gap between TM4 and TM6 of MsRv1272c (12.9 Å between Val243 and Gln358) is larger than that of MsRv1273c (5.0 Å between Thr184 and Pro299), so that the N-terminal extending loop of MsRv1272c could insert into the gap between Val243 and Gln358 (Fig. 2d). This is because the bending point of the kinked TM6 (Ala351) is at a higher position compared to its equivalent in MsRv1273c (Pro299) (Fig. 2d). A small relative rotation of NBDs is also observed by superposition (Fig. 2d), thus the NBD of MsRv1272c holds the CpH more deeply and tightly in its cleft.

a Overall view of the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the apo form IFapo. The black dashed circle indicates that there are dimer interactions between the two NBDs. The structure in the dashed boxes is shown in detail in panel e and f. TMD, transmembrane domain; NBD, nucleotide-binding domain; ECD, extra-cellular domain. b Clipped view of structure to show the central cavity in the TM region which opens towards the cytoplasmic side. c Surface representation of NBDs, viewed from the periplasm. CpH, coupling helix. d Superposition between MsRv1272c and MsRv1273c. Zoom-in views are shown in the inlets. Pro299 and Ala351 (magenta) are the hinge points of TM6 in the two subunits. The distance between TM4 and TM6 in both structures is provided. The rotation between NBDs is marked with a red double headed arrow. e Clipped view of the TMDs looking from the periplasm. The extending loop is colored in magenta. Trp246 is shown as yellow sticks. The central cavity is indicated by the red dashed circle. EH, elbow helix. f Close-up view of ECD (magenta) in MsRv1272c. The gray dotted arrow indicates the substrate releasing path when the TM region is separated into two wings in the OF state. ECL, extracellular loop; H, helix.

Interestingly, the structure of the transporter is asymmetrical, and in particular there are two additional structural features found in MsRv1272c which might be function related: (1) The N-terminal extending loop that inserts into the substrate binding cavity. The N-terminal extending loop (includes residues 1-16, but only 10-16 are observed in the IFapo structure) of MsRv1272c wraps around TM6 by forming a right angle with the elbow helix (EH) and then interacts with the sidechain of Trp246 in TM4, which is conserved among the mycobacterial Rv1272c homologs (Supplementary Fig. 12c). After that, the extending loop inserts into the gap between TM4 and TM6 (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 12a). We cannot further trace its structure inside the central cavity due to flexibility (residue 1-9 is missing). Since the extending loop is inserted and points into the central cavity in the IFapo state (Fig. 2e), we hypothesize that this loop might help the substrate enter the cavity. It remains unknown why the length and residue composition of the extending loop varies in different mycobacterial homologs of Rv1272c (Supplementary Fig. 12d). (2) The periplasmic helical hairpin structure that caps the exit of substrate-binding cavity. The extra-cellular domain (ECD) is formed by the extracellular loop 1 (ECL1, residue 62-109) between TM1 and TM2. It contains two short horizontal helices (H1 and H2) forming a helical hairpin structure and the protruding helix extending from TM1 (Fig. 2f). H1 interacts with ECL3 of MsRv1272c and ECL1 of MsRv1273c and H2 stacks above H1. The location of helical hairpin structure is on the path of the substrate releasing from the central cavity (Fig. 2f). Thus, the role of the ECD in this transporter is likely to help substrate release.

Structure in the ATP-bound Occ state

An approach to obtain the Occ state of ABC transporter is to inactivate the ATPase activity by making a glutamate to glutamine (EtoQ) mutation in the Walker B motif of NBD. This allows the trapping of the transporter in a pre-hydrolytic state when adding ATP43. Based on this, we purified the E553Q mutant which had a significantly diminished ATPase activity and then added ATP before data collection. We then solved the cryo-EM structure of E553Q mutant in the presence of ATP at 3.1 Å resolution, which showed an ATP-bound Occ state (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 3, 11h). In another experiment, vanadate (Vi) was added in an attempt to trap the transporter in a conformation immediately after ATP hydrolysis43. In such a state, ADP together with vanadate should stabilize the NBD dimer and trap an Occ state. After treatment with ATP and vanadate, the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c was solved and showed an ATP | ADP+Vi-bound Occ (Vi) state at 2.7 Å resolution (Supplementary Figs. 10, 11i, 16b and 16c). Since both structures adopt a similar conformation, only the ATP-bound Occ state was analyzed and compared here.

a Overall view of the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the ATP-bound Occ state. ATP is shown as blue spheres. b Clipped view of the structure in the Occ state. The central cavity in the TM region is sealed at the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides. c Surface representation of NBD dimer in the ATP-bound Occ structure, viewed from the periplasm. The degenerate site and consensus site are marked with red dashed circles. Nucleotides are shown as sticks. The dashed line linking β-phosphorus atoms at both sites serves as the reference line for measuring NBD rotation in other states. d The consensus nucleotide-binding site. The Q-loop, Walker B motif, Switch-loop, Walker A motif and A-loop in MsRv1272c are highlighted in yellow, while the D-loop, Signature motif and X-loop in MsRv1273c are highlighted in orange. Glu553 (here mutated to Gln) and His584 of MsRv1272c are shown as sticks. ATP and Mg2+ are represented as blue sticks and green spheres. e The degenerate nucleotide-binding site. The Q-loop, Walker B motif, Switch-loop, Walker A motif and A-loop in MsRv1273c are highlighted in orange, while the D-loop, Signature motif and X-loop in MsRv1272c are highlighted in yellow. Asp497, Gln528 of MsRv1273c are shown as sticks. f Close-up view of the degenerate site in the ATP-bound Occ structure. The Signature motif and Tyr343 of the A-loop are highlighted in blue and red, respectively.

In the Occ structure, the central cavity in the TM region is sealed at both the cytoplasmic and periplasmic sides (Fig. 3b). The N-terminal extending loop is squeezed out from the cavity (Supplementary Fig. 12b). The two NBDs are fully closed and interact with each other in an antiparallel manner (Fig. 3c). ATP is clamped between the dimer interface at the consensus and degenerate NBSs. The binding mode of ATP is similar at both sites and is classical amongst the ABC transporter family42. The binding and hydrolysis of ATP involves several conserved motifs around the binding site including Walker A motif, Walker B motif, A-loop, Q-loop, Switch-motif of one NBD and Signature motif of another (Fig. 3d, e). Taking ATP binding at the degenerate site for example, the α- and β-phosphate group of ATP binds in the groove formed by Walker A motif of MsRv1273c, while the γ-phosphate group is stabilized by Mg2+ and helix α6 of MsRv1272c. The adenosine group of ATP is sandwiched by the A-loop and Signature motif MsRv1273c (Fig. 3f).

Structure in the AMPPNP-bound IFasym-1 state

To capture a pre-hydrolytic state occurring before the Occ state, we treated the cryo-EM sample with AMPPNP, since it is a non-hydrolysable analog of ATP. The cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the AMPPNP-bound IFasym-1 state was then obtained (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Figs. 4, 11b). Similar to the IFapo state, the central cavity still opens towards the cytoplasm and the extending loop also inserts into the gap between TM4 and TM6 of MsRv1272c (Supplementary Fig. 12e). However, in this state, the overall conformation is asymmetric, especially at the NBDs. Though both NBSs bind AMPPNP, the NBDs are partially dimerized at the degenerate site whereas there is a gap between NBDs at the consensus site (Fig. 4b). Thus, the ability of AMPPNP to mediate NBD dimerization at consensus site is reduced compared with that at degenerate site. The binding mode of AMPPNP at the consensus site in the IFasym-1 structure superposes well with that of ATP in the Occ structure while the nucleotide binds distinctly at the degenerate site (Supplementary Fig. 13j, k). In the IFasym-1 state, we observed that the whole NBD of MsRv1272c binds to the other NBD with a rotation angle of 8.1° around the degenerate site (Fig. 4b). Due to this rotation, helix α5 moves closer to the A-loop of MsRv1273c (Fig. 4c) and as a result the nucleotide is more buried in the degenerate site compared to the ATP-bound Occ structure (Fig. 3f). Helix α6 is pointing away from the γ-phosphate group, and therefore cannot stabilize it by using its dipole. Moreover, the Signature motif moves away from the degenerate site following the shift of helix α6 and is not able to clamp the adenosine ring of the nucleotide together with Tyr343 of A-loop (Fig. 4c). These observations indicate that AMPPNP binds weakly at the degenerate site in the IFasym-1 state.

a Overall view of the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the AMPPNP-bound IFasym−1 state. AMPPNP is shown as purple spheres. b Surface representation of the NBD dimer in the IFasym−1 structure, viewed from the periplasm. The NBD of MsRv1273c is fixed as in Fig. 2g and the rotation (red arrow) of NBD of MsRv1272c is measured based on the position of the β-phosphorus atom of the nucleotide in the NBS (the angle between the two dashed lines linking β-phosphorus atoms at both sites). The degenerate site and consensus site are marked with red dashed circles. AMPPNP is shown as sticks. c Close-up view of the degenerate site in the IFasym−1 structure. The Signature motif and Tyr343 of the A-loop are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. The shifts of α5 and α6 relative to the Occ structure in Fig. 3f are marked with red arrows. d Overall view of the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the ADP-bound IFasym-3 state. ADP is shown as green spheres. e Surface representation of NBD dimer in the IFasym-3 structure. f Close-up view of the degenerate site in the IFasym-3 structure. g Overall view of the cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state. ATP and ADP are shown as yellow spheres. h Surface representation of NBD dimer in the IFasym-2 structure. i Close-up view of the degenerate site in the IFasym-2 structure.

Structure in the ADP-bound IFasym-3 state

To capture more post-hydrolytic states after the Occ state, we prepared cryo-EM samples with different treatments of nucleotides. We obtained two ADP-bound cryo-EM structures after samples were treated with ATP at 37 °C or ADP at 4 °C (Supplementary Fig. 6, 7, 11d, 11e). Since the two structures show a similar asymmetric conformation and the same bound nucleotide (Supplementary Fig. 16a), they can be considered as one state, the IFasym-3 state. We then used the ATP (37 °C) treated IFasym-3 structure for further analysis. In this structure, ADP binds at the consensus site (Fig. 4d) as a hydrolyzed product after ATP hydrolysis. Interestingly, there is no nucleotide at the degenerate site even though we added ATP or ADP in the sample. The NBDs are also partially dimerized (Fig. 4e), but the conformation is different from the IFasym-1 state. We found the gap at the consensus site is larger in this IFasym-3 structure. We also observed that the whole NBD of MsRv1272c binds to the other NBD with a rotation angle of 23.8° around the degenerate site (Fig. 4e). The dimerization is only based on direct interactions between the two NBDs at the degenerate site (Fig. 4f). Due to a large rotation of the NBD in MsRv1272c, helix α5 inserts into the inner side of the A-loop of MsRv1273c and occupies the binding position of the adenosine group of ATP together with the side chain of Tyr343. The direction of helix α6 also significantly deviates from the phosphate binding site of ATP resulting in the gap between the Signature motif and Tyr343 of the A-loop being too small to clamp the adenosine group of ATP (Fig. 4f). Thus, such a distorted degenerate site does not allow the binding of ATP.

Structure in the ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state

When the sample was treated with ATP at 4 °C, we obtained a cryo-EM structure of MsRv1273c/72c in the IFasym-2 state (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 5, 11c). In this structure, the conformation is also asymmetric but is different from the IFasym-1 and IFasym-3 states. The NBDs are partially dimerized at the degenerate site with a larger rotation angle of 32.8° (Fig. 4h). The consensus site is bound with an ADP, which originates from the rapid hydrolysis of ATP, while the degenerate site is bound with an ATP, which has not been hydrolyzed. The structure of the ATP bound site is also distorted (Fig. 4i). The direction of helix α6 deviates further compared to the IFasym-3 state and it is not able to interact with the γ-phosphate group of the bound ATP. The Signature motif linking to α6 is still able to weakly clamp ATP with Tyr343 in the A-loop (Fig. 4i). Considering the sample preparation condition, this IFasym-2 structure may represent a state before IFasym-3 and after Occ.

To support this proposal, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulation starting from the IFasym-2 structure by removing ATP in the degenerate site, then we inspected the conformations and analyzed the changes in the distance between the two NBDs close to the consensus site during 100 ns simulation (Supplementary Fig. 14d). We found that the NBDs keep interactions at the degenerate site and IFasym-3 liked states with distance similar to the IFasym-3 state could be induced from the IFasym-2 state if ATP in the degenerate site is released.

Conformational changes between different states

Next, we analyzed conformational changes by comparing the different states of MsRv1273c/72c. In the IFapo structure, the NBDs are separated both at consensus and degenerate sites by 8.4 Å and 10.7 Å, respectively (Fig. 5a). NBDs are partially dimerized at the degenerate site in the three asymmetric states. The corresponding distances are 9.6 Å and 7.9 Å for the IFasym-1 structure, 17.0 Å and 7.6 Å for the IFasym-2 structure, 13.5 Å and 8.2 Å for the IFasym-3 structure. In the ATP-bound Occ structure, the NBDs are fully dimerized with distances of 6.8 Å and 6.1 Å at the two NBSs. During NBD closure, the two CpHs in the TMDs move closer to each other with the distance reducing from 23.5 Å to 12.5 Å (Supplementary Fig. 14a). Superposition of the TMDs for each subunit shows that TM4-5 shifts towards the helix bundle composed of TM2-3 and TM6 at the cytoplasmic side (Supplementary Fig. 14b, c). These changes lead to an opening and closing of the central cavity as the structure moves between the IF and Occ states. Thus, the three IFasym states adopt intermediate conformations.

a Changes in distance between the two NBDs in the five states. The distances at the degenerate site are measured between Gly371 of MsRv1273c and Ser529 of MsRv1272c, and the distances at the consensus site are measured between Ser473 of MsRv1273c and Gly427 of MsRv1272c. The position of all the measured residues is indicated by red spheres. b Superposition of NBDs of MsRv1272c in the five states. The shifts of D-WalkerB loop and X-signature loop are marked with red double headed arrows. c Conformational changes of NBD of MsRv1272c from IFapo state (cyan) to IFasym−1 state (gray). Important residues are shown as sticks. Shifts of helices and residues are marked with red arrows. d Separate views of the degenerate site for the five states show the conformational changes of the D-WalkerB loop and X-signature loop.

Besides the rigid-body movement of NBDs during NBD closure, local structural rearrangements are also observed in the NBD of MsRv1272c. For example, the region containing a part of the D-loop, a part of the Walker B motif and the connecting residues (554AT555), which we assigned as the D-WalkerB loop (552DEATSSVD559), adopts a classical S-shaped conformation when the NBD binds nucleotide (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 13h). However, the loop is adjusted to form an L-shaped conformation in the IFapo state (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 13g). In this state, the catalytic residue, Glu553, points in the opposite direction to the consensus NBS. Meanwhile, Asp552 of the Walker B motif also shifts away from the NBS (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, the locations of α7 and α8 have changed and a gap is created to accommodate the side chain of Glu553. Glu553 is further stabilized through interactions with Arg585 and Thr588. Meanwhile, His584 of the Switch-loop linking to α8 is also pulled away from the NBS (Fig. 5c). Thus, the consensus NBS is distorted in the IFapo state. So, how can structural rearrangements occur to activate the consensus site? We found that the partial dimerization at the degenerate site in the intermediate state (IFasym-1) is indispensable to trigger the activation. When the two NBDs approach each other, α7 and the D-loop of MsRv1272c will clash with the NBD of MsRv1273c at the degenerate site (Supplementary Fig. 13i). Thus, under the packing force, α7 will be squeezed backwards and towards α8 (Fig. 5c, d). The D-WalkerB loop will be crimped to the “S” conformation and the whole consensus NBS will be positioned to bind and hydrolyze ATP (Fig. 5c, d). Thus, the classical and active form of NBD of MsRv1272c is only stabilized upon NBD closure at the degenerate site. This could prevent futile consumption of ATP at the consensus site when NBD dimerization at the degenerate site does not happen. These analyses show that the D-WalkerB loop of MsRv1272c plays a crucial role in coordinating the allosteric coupling between the degenerate site and consensus site through conformational changes. Note that similar “L” and “S” conformations of D-WalkerB loop have also been observed in the IF and OF structures of TM287/28821,22. However, no structural evidence for how and when they transit between each other under the intermediate states has been provided previously.

Another structural rearrangement is in the fragment we assigned as the X-signature loop (522DDDGGAIS529) which contains a part of the X-loop, a part of the Signature motif and the connecting residues (526GA527) (Fig. 5b). It is stretched into the gap between the two CpHs in the IFapo and IFasym-3 states (Fig. 5d) so that the Signature motif at the degenerate site cannot bind ATP (Supplementary Fig. 13i). In the Occ state and IFasym-1 state, the X-signature loop is clamped by the two approaching CpHs. As a result, the Signature motif could be re-shaped in a favorable position to interact with ATP at the degenerate site (Fig. 5d). From this point of view, the IFasym-3 state is closer to the IFapo state while the IFasym-1 state is more similar to the Occ state.

Altogether, the above analysis suggests that through the intermediate IFasym states, conformational changes in the D-WalkerB loop and the X-signature loop of MsRv1272c occur. These changes modulate and couple the function of both the consensus and degenerate NBSs. Therefore, visualization of the intermediate states has explained how the transporter transits between the IF state and Occ state, which are necessary for the function of this transporter.

Discussion

In the structures of the heterodimeric transporter of MsRv1273c/72c, there are several asymmetrical features in comparing the two subunits. MsRv1273c bears the degenerate site and the classical fold of half an ABC transporter, while MsRv1272c contains more structural features compared to the canonical type IV ABC transporter. Strikingly, an additional extending loop at the N-terminus of MsRv1272c is observed. A similar N-terminal extending loop is also observed in TM287/288 (Supplementary Fig. 12e). In that structure (PDB code: 3QF4), it is proposed that this loop restricts the movement of ICL4 (and of NBD1 connected to it) with respect to the other TM helices and might therefore further strengthen the interaction between the NBDs21. In the structure of the heme transporter, EcCydDC (PDB code: 8IPS), an additional helix extends from EH of CydD (Supplementary Fig. 12e) and it is responsible for stabilizing the substrate-loaded conformation by interacting with TM441. However, our analysis showed that the extending loop in MsRv1272c appears more likely to play a role in helping the substrate enter the cavity. The helical hairpin structure of ECD is another additional feature in MsRv1272c which is also found in several other ABC transporters but with different folds. In BmrCD, the β-stranded architecture of ECD is also formed by ECL1 of the consensus subunit (Supplementary Fig. 12f), and it is thought that translocation of substrate through the TMD is facilitated via an interaction with ECD. The ECD contributes to the transport cycle by influencing substrate positioning or by promoting formation of the low-affinity site for substrate release44. In the ABCA family of exporters, the large and complicated structure of ECDs (Supplementary Fig. 12f) may serve as a temporary storage space or a delivery passage for lipid substrates by forming a hydrophobic tunnel45. In LptB2FG, both the β-jellyroll-like ECDs of LptF and LptG (Supplementary Fig. 12f) are involved in LPS transport46. These examples suggest that the diverse ECDs of ABC transporters may have a common function to facilitate substrate translocation. For MsRv1273c/72c, further evidence will be required in future studies to understand the precise roles of the extending loop and helical hairpin. The nucleotide binding position and orientation at the consensus site of MsRv1273c/72c is classical amongst ABC transporters and is similar within our structures (Supplementary Fig. 13j). However, its binding mode is variable at the degenerate site among the different states (Supplementary Fig. 13j and 13k). Besides these asymmetric features, the D-WalkerB loop and X-signature loop of MsRv1272c undergo conformational changes to affect ATP binding and hydrolysis at the consensus and degenerate sites and in coordinating the allosteric coupling between the two sites. These analyses help us to understand the unique structural and functional asymmetry in the heterodimeric ABC transporters that are missing in homodimeric transporters.

In this study, we expected to capture the OF state by using AMPPNP, vanadate or the EtoQ mutant to induce NBD closure. However, the IFasym states and Occ state were observed instead of the OF state. In the study of TmrAB, the authors suggest that in the resulting OF state, the transporter can transit between OF and Occ conformations until the release of Pi from the canonical site weakens the interactions between the NBDs25. Our results imply that the transporter is more stable at the Occ state than the OF state when the NBDs are fully closed. Addition of substrate could potentially stabilize the OF state and move the equilibrium from Occ towards OF state.

The ADP (4 °C) treated IFasym-3 state indicates that ADP can bind to the consensus site but cannot bind to the distorted degenerate site. The ATP (37 °C) treated IFasym-3 state suggests that it may represent a state after ATP hydrolysis. In this structure, ADP binds at the consensus site as a hydrolyzed product, however, it is interesting that NBDs dimerized at the degenerate site without nucleotide binding. Since ATP is prone to induce NBD dimerization and it is not easy to release from NBS, it is possible to be hydrolyzed to ADP and then release from the distorted degenerate site with weak binding affinity. However, more studies are required to determine how the nucleotide is released from this site. The nucleotides (ATP/ADP) are either substrates or products of the transporter, and either induces physiologically relevant conformations. An artificial state is unlikely to be induced by these functional molecules. Thus, we believe that the IFasym-3 state represents a nucleotide-induced physiological conformation. On the other hand, it is possible that there are contacts between NBDs without nucleotide being present in the NBS. For example, both the C-terminal end of NBDs in our IFapo structure (Fig. 2a) and the apo structure of TM287/288 (PDB code: 4Q4H)23 are involved in NBD partial dimerization. To rule out the effect of detergent on the induction of this state, we reconstituted the protein sample in a peptidisc47 and then solved structures with the same treatments (adding ATP at 37 °C or ADP at 4 °C). These new structures (here we named IFasym-3 (peptidisc) (Supplementary Fig. 8, 9, 11f–g)) adopt the same conformation as the IFasym-3 state (Supplementary Fig. 16a). This suggests that this conformation is induced by the nucleotide and it is not an artifact of the detergent used.

For the heterodimeric ABC exporters, IF, Occ and OF states have been reported14. However, in only a few cases have asymmetrical conformations with NBDs partially dimerized at one NBS been reported. For example, in the structure of heme transporter, CydDC (PDB code: 7ZDA and 7ZDK)48, the NBDs are partially dimerized at the functional consensus site and widely separated at the presumed degenerate site (Supplementary Fig. 13d). Note that the dimerized site is contrary to what is observed in the MsRv1273c/72c structure. In addition, the nucleotide at this site does not participate in dimer formation as is observed in other NBDs. An elexacaftor-bound ABC transporter CFTR ∆508 mutant (PDB code: 8EIG)49 also has a “cracked-open” NBD dimer structure partially held together by the presence of ATP at the consensus site (Supplementary Fig. 13e). This contrasts with the MsRv1273c/72c structures that dimerize at the degenerate site. Because elexacaftor is not endogenous to the cell, this is not a conformation likely to exist physiologically. For the heterodimeric ABC exporter TmrAB, conformation space under turnover conditions has been reported. In the captured asymmetrical IF structures (PDB code: 6RAM and 6RAL)25, ATP at the degenerate site mediates the NBD dimerization while a fine crack is observed at the ADP-bound consensus site (Supplementary Fig. 13f). This state is nearly identical to the Occ state of TmrAB (PDB code: 6RAI and 6RAK). Here, our structures in the IFasym-1, IFasym-2 and IFasym-3 states (Supplementary Fig. 13a–c) are distinct from previously reported asymmetrical conformations. These IFasym states may represent obligatory intermediate conformations during transport that have never been captured for heterodimeric ABC exporters and help to explain how conformational transition occurs when a degenerate site is present.

Based on the above analysis of cryo-EM structures in the IFapo state, ATP-bound Occ state, AMPPNP-bound IFasym-1 state, ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state and ADP-bound IFasym-3 state, as well as previous knowledge of the alternating-access transport model of ABC transporters50, a detailed mechanism for the MsRv1273c/72c transporter with a degenerate NBS can now be proposed (Fig. 6): (1) Substrate enters the central cavity with the help of the extending loop in the IFapo state or the later IFasym-1 state. (2) ATP binds to both NBSs and acts as a glue for the partial dimerization at the degenerate site. In the meantime, the X-signature loop of MsRv1272c is induced to interact with ATP. Upon dimerization, conformational changes of the consensus NBD are triggered, especially for the formation of the “S” conformation of the D-WalkerB loop of MsRv1272c, and then the distorted consensus site is activated. The transporter is in the ATP-bound IFasym-1 state. (3) The NBDs are fully dimerized to induce shifts of the TM helices. As a result, the central cavity is occluded and the extending loop is squeezed out. The transporter is in the ATP-bound Occ state. (4) The central cavity opens towards the periplasm and substrate is released with the help of ECD. Note that the ATP-bound OF state is unstable and it may exist only transiently25. (5) ATP hydrolysis occurs at the consensus site during the Occ or OF stage. (6) Phosphate is released at the consensus site, the NBDs are separated with a large gap at the ADP-bound consensus site while they are still in contact at the ATP-bound degenerate site, accompanied by the changes of the X-signature loop of MsRv1272c. So, the structure returns to the ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state. (7) ATP is then released from the distorted degenerate site by an unknown mechanism, possibly in the form of ADP after slow hydrolysis. The NBDs are still dimerized at the empty degenerate site. The transporter is then in the ADP-bound IFasym-3 state. (8) NBDs are further separated at the degenerate site, this allows the D-WalkerB loop of MsRv1272c to stay in the relaxed “L” conformation and ADP is released from the distorted consensus site. Finally, the transporter returns to the IFapo state. This completes the major cycle of transport. Possibly, there is also a minor cycle branch after step (6). The transporter in the ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state is able to load a new substrate (with help of the extending loop) and exchange ADP with a new ATP molecule at the consensus site. At the degenerate site, ATP does not have time to hydrolyze but still binds there. This allows the transporter to directly enter step (2) for a new cycle. The minor cycle may represent a highly effective mode of transport. To complete the full suite of structures to explain the mechanism requires additional intermediate states to be determined. Further evidence is needed to explain how step (7) occurs to induce the conversion from the IFasym-2 state to the IFasym-3 state (Fig. 6).

Entry and release of substrate is proposed to require the extending loop and ECD of MsRv1272c. NBD partial dimerization is mediated by the degenerate site in the three types of intermediate asymmetric states. Conformational changes of NBD in MsRv1272c, especially the D-WalkerB loop and X-signature loop, are necessary for the function of both NBSs, including activation of the consensus site and release of nucleotide from the degenerate site. To validate how ATP is released to induce the conversion from IFasym-2 to IFasym-3 will require the determination of the structure of more intermediate states (marked with a question mark). MsRv1273c and MsRv1272c are shown in blue and light blue, respectively. The dashed box indicates states with NBDs fully closed.

There are a large family of heterodimeric ABC exporters with a degenerate site, and these are typically found in higher eukaryotes. For example, about half of the human heterodimeric ABC exporters have a degenerate site21. Because of the existence of a degenerate site, the heterodimeric ABC transporters have a mechanism of transport that is different from the homodimeric counterparts. We suggest that the partial dimer of NBDs mediated by the degenerate site is indispensable for the transition between the IFapo state and Occ state in MsRv1273c/72c. Thus, the degenerate site is essential for the functioning of the transporter. The number of reported structures of ABC exporters with a degenerate site is limited, most of which are in the IF, Occ, and OF states. Though the conformational differences between these states have been analyzed, the detailed transition process has never been elucidated. This is due to a lack of information on the key intermediate steps, even though the conformational space has been delineated by the study of the TM287/288 transporter25. The findings from this study, including the intermediate states and the structural basis of degenerate-site mediated transport cycle improve our understanding of the mechanism for heterodimeric ABC transporters where a degenerate site is present.

Since Rv1273c/72c is functionally essential for lipid construction of the Mtb cell wall in being able to transport long-chain fatty acids32,33, we hypothesize that the physiological substrate is a lipid precursor for the cell wall. In our IF state cryo-EM maps, i.e., the IFapo state, we cannot accurately identify densities that are found in the central cavity (Supplementary Fig. 15a). They are surrounded by residues including Phe183, Gln238, Phe293 of MsRv1273c and Asn186, Gln194 of MsRv1272c (Supplementary Fig. 15a). These densities could belong to the substrate or the N-terminus of the extending loop. However, we favor substrate, since their position is similar to the substrate binding site reported in other ABC transporters such as BmrCD (PDB code: 7M33)44, Atm3 (PDB code: 7N59)51 and ABCB6 (PDB code: 7DNY)52 (Supplementary Fig. 15b). Further studies will be required to definitively identify the physiological substrate of Rv1273c/72c.

Rv1273c/72c is a good target for new drugs to treat TB. This is because its role is critical in cell wall biosynthesis, critical to pathogen survival in the host cell and the immune response, and in drug resistance. In particular, we have shown that MsRv1273c/72c is a drug efflux pump for isoniazid. MsRv1273c/72c shares 71% overall sequence identity with Mtb Rv1273c/72c. Even though the localized environments could be different between the Mtb and Msm heterodimers, the overall folds, intermediate conformations and functional sites are expected to be conserved. In addition, we can generate models of Mtb Rv1273c/72c in different intermediate states and use these as templates for inhibitor design. Thus, our structures solved here represent accurate templates for anti-TB drug design. Though there are many ATP-binding transporters with different functions, they are also different in structures, conformations and mechanisms of action. Potentially, the unique structural features in Rv1273c/72c such as the extending loop and ECD could be blocked by designed inhibitors, not affecting other ATP-binding transporters. Alternatively, the conformational changes important for transport could be inhibited by targeting the D-WalkerB loop and X-signature loop of Rv1272c, especially in the distorted degenerate and consensus sites. The residues in the surrounding space of the ATP binding site are different from other ATP-binding transporters and could also be used for the development of specific inhibitors and drugs. Thus, our structures provide a solid framework for the development of anti-TB drugs.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

The cluster of rv1273c-rv1272c genes from Mtb H37Rv strain genome or the cluster of msmeg_5008-msmeg_5009 genes from Msm mc2 155 strain genome were cloned into the engineered pMV261 vector fused with a Flag-tag or a 6×His-tag attached to the C-terminus of Rv1272c or its Msm homolog, under the control of the acetamide promoter. The sequences of primers used for cloning were provided in Supplementary Data 1. The Msm mc2 155 competent cells were transformed by electroporation of the resultant plasmid. The cells were cultivated at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth liquid media supplemented with 50 μg mL–1 kanamycin, 20 μg mL–1 carbenicillin, and 0.1% (w/v) Tween80 until the optical density at 600 nm reached 1.0. Overexpression of the recombinant protein was induced by 0.2% (w/v) acetamide at 16 °C. After four days, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 × g for 20 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in Buffer A containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl and then lysed by passing through a high-pressure homogenizer at 1100 bar. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and ultra-centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 1.5 h. The membrane fraction was solubilized in Buffer A with the addition of 1% (w/v) N-dodecyl-b-D-maltoside (DDM; Anatrace) at 4 °C for 1.5 h. The suspension was ultra-centrifuged and the supernatant was supplemented with 10 mM imidazole and then loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads (Qiagen) affinity column. The beads were rinsed with Buffer A supplemented with 0.02% (w/v) DDM, and 30 mM imidazole, and the recombinant protein complex was eluted from the beads with Buffer A supplemented with 0.06% (w/v) Digitonin (Biosynth Carbosynth) and 500 mM imidazole. The eluted sample was concentrated and applied to a size exclusion chromatography column (Superose 6 Increase, GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with Buffer A supplemented with 5 mM DTT, and 0.06% (w/v) Digitonin. Finally, the main peak fractions were pooled and concentrated to 10 mg mL−1 for further studies or stored at –80 °C.

All mutants of MsRv1273c/72c were generated by the TaKaRa MutanBEST Kit using the DNA sequence of the wild-type protein as the template. The sequences of primers used for cloning were provided in Supplementary Data 1. Expression plasmids were prepared in the same way as for the wild-type transporter. Mutated proteins were expressed and purified following the same protocol as the wild-type protein except that DDM was used during the entire purification procedure for the MsRv1273c/72cE553Q mutant.

To remove detergent and prepare protein reconstructed in peptidisc, lyophilized NSPr (Nter-FAEKFKEAVKDYFAKFWDPAAEKLKEAVKDYFAKLWD-Cter) (Genscript, purity >98%) was solubilized in Buffer A at room temperature to a final concentration of 1 mg mL–1 (Buffer B) and kept on ice for use47. After rinsing the Ni-NTA beads with Buffer A containing 0.02% (w/v) DDM and 30 mM imidazole, 10 mL Buffer B was added to the beads and incubated for 10 min on ice. The recombinant protein complex was eluted from the beads with Buffer B supplemented with 500 mM imidazole. The eluted sample was concentrated and applied to a Superose 6 column pre-equilibrated with Buffer B supplemented with 5 mM DTT. Finally, the main peak fractions were pooled and concentrated to 2 mg mL–1 for further studies or stored at –80 °C.

Cryo-EM grid preparation and data collection

For cryo-EM grid preparation, aliquots (3 µL) of fresh protein samples at 10 mg mL−1 (2 mg mL–1 for samples in the peptidisc) after purification were immediately applied to H2/O2 glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Cu R1.2/1.3). Grids were blotted for 3.0 s and flash-frozen in liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen using an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher) with the environmental chamber set to 100% humidity and 8 °C. For the AMPPNP-bound IFasym-1 state, the protein was incubated with 5 mM AMPPNP and 4 mM MgCl2 at 4 °C for 30 min before grid preparation. For the ATP-bound Occ state, the MsRv1273c/72cE553Q mutant was incubated with 4 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 at 4 °C for 30 min before grid preparation. For the ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state, the protein was incubated with 10 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 at 4 °C for 30 min before grid preparation. For the ADP-bound IFasym-3 state and IFasym-3 (peptidisc) state, the protein was incubated with 10 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C for 5 min before grid preparation. Alternatively, 10 mM ADP and 4 mM MgCl2 were incubated with the protein at 4 °C for 30 min before grid preparation. For the ATP | ADP+Vi-bound Occ (Vi) state, 10 mM ATP, 4 mM MgCl2 and 20 mM Na3VO4 were incubated with the protein at 37 °C for 5 min before grid preparation. Cryo-EM data were collected on a FEI Titan Krios electron microscope operated at 300 keV with a Gatan K3 camera at a nominal magnification of ×105,000 in super-resolution mode and binned to a pixel size of 0.832 Å (or 0.96 Å). Automated single-particle data acquisition was performed with the automated data collection program Serial EM53. Each movie was recorded in 40 frames with a total exposure time of 6.4 s and a total exposure dose of 60 e−/Å2. The nominal defocus range was set to –1.8 to –1.2 μm. The sample preparation conditions and data collection parameters for all the structures are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Cryo-EM image processing

All dose-fractionated image stacks were motion-corrected and dose-weighted using MotionCorr2 software54. CTF estimation was performed using the “Patch CTF Estimation” program in cryoSPARC (v4.0.1)55. For the dataset of IFapo state, 4863 micrographs were selected after those images that exhibited defects in the Thon rings due to excessive drift, ice contamination, or astigmatism were discarded. 3,566,457 particles were automatically extracted using a box size of 320 pixels and subjected to several rounds of reference-free 2D classification to discard bad particles, yielding a stack of 378,470 particles. They were used for Ab-Initio reconstruction to generate 3D models as references to perform heterogeneous refinement. The particles belonging to the correct initial map were subjected to several rounds of heterogeneous refinement. After that, 139,918 particles belonging to the map with best resolution were then refined using non-uniform (NU) refinement to generate the final cryo-EM map with an estimated average resolution of 3.1 Å according to the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation cutoff of 0.14356. No mask was used for all the map refinement processes. All the other datasets were processed in the same pipeline. Local resolution ranges were also analyzed using cryoSPARC for each map.

Model building and refinement

The AlphaFold2 predicted models of MsRv1273c (AF-A0R271-F1) and MsRv1272c (AF-A0R272-F1) were used as the initial models, and they were fitted as rigid bodies into the cryo-EM map of MsRv1273c/72c complex in the IFapo state and adjusted manually using Coot57. The structure was refined in real space using PHENIX58 with secondary structure and geometry restraints to prevent over-fitting. The final atomic model was evaluated using MolProbity59. The structure in the IFapo state was further used as the initial model for other states. The processes of model building and refinement for these states are similar to the IFapo state. ATP, ADP, AMPPNP, Mg2+ and Vi were fitted into the corresponding cryo-EM map according to the additional non-protein density. The refinement statistics of all final models are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The composition of all the models is summarized in Supplementary Table 2. All the figures were generated using PyMOL (The PyMOL molecular graphics system, Schrödinger, LLC.) or UCSF Chimera (http://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimera).

Preparation of proteoliposomes

Proteoliposomes were prepared according to a standard protocol described previously60. Briefly, 20 mg of E. coli polar lipids containing 67% (w/w) PE, 23.2% PG and 9.9% CA (Avanti) were dissolved sequentially in chloroform and ether and dried with a rotary evaporator at 37 °C to produce a thin lipid film. The film was suspended with 1 mL buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl and then sonicated. Next, the lipid suspension was frozen and thawed three times. Subsequently, the lipids were extruded through a 0.2 µm polycarbonate filter using a mini-extruder (Avanti). This step was performed 11 times. The liposomes produced were destabilized by 15 additions of 10 µL aliquots of 10% (w/v) Triton X-100 so that the solution becomes optically transparent. After that, the protein was mixed with the liposomes at a ratio of 1:100 (w/w) at 4 °C. It was then diluted to 4 mL with Buffer A (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl). 80 mg of Bio-Beads SM-2 was added to the mixture and incubated overnight to remove the detergent. Proteoliposomes were collected by centrifugation at 230,000 × g for 30 min. Then, they were suspended in Buffer A and the lipid concentration was adjusted to 20 mg mL-1 for further studies or stored at –80 °C. The integrity of vesicles was checked by negative stain EM to guarantee that all the proteoliposomes were integral and no protein aggregation was formed (Supplementary Fig. 1f). The efficacy of reconstitution was evaluated by SDS-PAGE showing about 97% of the added protein became incorporated into the proteoliposomes (Supplementary Fig. 1e). This ratio was used to adjust the amount of protein in the ATPase and transport assays. The concentration of the liposome-reconstituted transporter was further adjusted by considering the 50-50% distribution of two configurations (outside-out and inside-out) in the proteoliposomes61. Only the activity of NBDs in the inside-out configuration can be measured.

ATPase activity assay

The ATPase activity assay was performed as described previously41. The released Pi from ATP hydrolysis reacts with malachite green reagent to form a stable dark green complex, whose presence is detected by measuring absorbance at 620 nm. The intensity of the color is directly proportional to the amount of Pi generated, and thus, to the ATPase activity in the sample. For the assay, 4.68 µg of purified protein complex or the mutants was incubated in a 20 µL reaction volume containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 for 10 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by mixing 100 µL aliquots with activated malachite green ammonium molybdate for 2 min. Samples were subsequently incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 24% (w/v) sodium citrate after which the absorbance at 620 nm was measured using a SpectraMax iD3 multifunction reader (Molecular Devices). Samples without protein were used as the negative controls and subtracted as background. ATPase activity is represented as the amount of Pi produced by 1 mg of protein per minute. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Liposome-based transport assay

Wild type protein complex or the mutant was inserted into proteoliposomes as described above. Liposomes without inserted proteins were used as the negative control. 20 mg mL–1 lipid concentration of proteoliposomes or control liposomes, 50 μM of isoniazid or ethambutol, 5 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 were mixed to prepare a reaction system with a total volume of 100 μL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Liposomes were then collected by centrifugation at 230,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in Buffer A, followed by another centrifugation at 230,000 × g for 30 min. This washing step was repeated three times. The pellet was resuspended in 200 μL Buffer A mixed with 200 μL ethyl acetate. The mixture was vortexed and then allowed to stand for 3 min. The upper layer was aspirated and evaporated to dryness under a stream of warm air. The residue was reconstituted in 200 μL methyl cyanide and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter for mass spectrometry. 0.1 μg mL-1 of either isoniazid (0.73 μM) or ethambutol (0.36 μM) were separately tested by mass spectrometry, which was used as the standard reference.

To quantify the amount of isoniazid transported by proteoliposomes, isoniazid standards were dissolved in methanol at concentrations of 0.02, 0.2, 1, 10, and 50 μg mL–1. The calibration curve was generated using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Next, 20 mg mL–1 lipid concentration of proteoliposomes, 5 or 50 or 500 μg mL–1 isoniazid, 5 mM ATP and 4 mM MgCl2 were mixed to prepare a reaction system with a total volume of 100 μL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After that, the proteoliposomes were washed three times and the pellet was suspended in 100 μL of buffer A. Next, 900 μL of methanol was added to disrupt the proteoliposomes. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min before being passed through a 0.22 μm filter to prepare the samples for LC-MS/MS analysis. The transport rate is the amount of isoniazid transported by 1 mg of protein per minute. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis was performed using an Agilent 6230 mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The sample injection volume was 3 µL. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% methanol in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in methanol (B), mixed at a ratio of 30% A and 70% B. The flow rate was set to 0.2 mL min–1, with a total analysis time of 2 minutes. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode, with a capillary voltage of 3.0 kV, a drying gas flow rate of 11 L min-1, and a drying gas temperature of 350 °C. The nebulizer pressure was set to 40 psi. The fragmentor voltage was set at 140 V. Data were acquired in the mass range of 100–1000 m/z. All data acquisition and processing were performed using Agilent MassHunter software (Agilent Technologies).

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

LC-MS/MS was performed using a Shimadzu 30 A HPLC system equipped with an autosampler, binary pump, and column oven, coupled with an AB 4600 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) equipped with a Turbo Ion Spray source. The mobile phases consisted of 0.1% formic acid in distilled water (A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (B) run at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min–1. Chromatography was performed using an ACE C4 column (5 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm) with a gradient elution. The column temperature was set at 75 °C. The gradient elution condition was set as follows: t = 0 min, A = 100%, B = 0%; t = 2.5 min, A = 100%, B = 0%; t = 5 min, A = 5%, B = 95%; t = 6.5 min, A = 5%, B = 95%; t = 6.6 min, A = 100%, B = 0%; t = 8.0 min, A = 100%, B = 0%. The Electrospray Ionization was set in positive ion mode: the voltage value was 5500 V, gas 1 and gas 2 were set at 50 psi, and the curtain gas at 35 psi. The scan range was set from 80 to 550 Da. The collision energy was set to 30. The mass transition of isoniazid was 138 (m/z) to 121 (m/z)62. In the first-stage, mass spectrometry (MS1) was used to obtain precursor ions; and in the second stage, the precursor ion with m/z 138 was further analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS2). Data were collected to determine the quantity of the substance with m/z 121 by MS2. All data acquisition and processing were performed using Analyst and PeakView (SCIEX). The raw spectrum for LC-MS/MS were provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Growth-complementation assay

The Msm wild type strain (WT-Msm), MsRv1273c/72c knockout strain (∆MsRv1273c/72c) and the complemented strain containing pMV261-MsRv1273c/72c (∆+MsRv1273c/72c) were separately plated on Luria Agar (LA) supplemented with 100 μg mL–1 carbenicillin. Single colonies were picked and cultured in LB liquid medium containing 100 μg mL-1 carbenicillin until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6–0.8. The cultures were then diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 in 100 mL of LB medium supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) Tween80. For the experimental groups, 0.15 μg mL-1 ethambutol or 0.05 μg mL–1 isoniazid was added into the medium and cultured in a 37 °C shaker. Cell growth was determined by measurement of OD600 in triplicate.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

To simulate the motion progress from IFasym-2 to IFasym-3, the starting model was constructed using the IFasym-2 structure with ATP removed from the degenerate site. The system was built with the CHARMM-GUI webserver63 using CHARMM36m64 force field and TIP3P water model. Protein was embedded into the lipid bilayer consisting of 50% 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 50% 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE). The upper layer has 136 POPC molecules and 136 POPE molecules while the lower layer has 131 POPC molecules and 131 POPE molecules. The structure described above was solvated in a cubic water box containing 0.5 M NaCl. The simulation box dimensions are about 136 Å × 136 Å × 197 Å with 348,028 atoms, which include 86,313 water molecules. Energy minimization, NVT and NPT equilibration were performed in six steps, then, 100 ns production was performed by GROMACS 2024.165 at 310.15 K for three independent runs, with trajectories saved at 10 ps intervals, and with default parameters provided by CHARMM-GUI webserver. The distance was calculated between the mass center of all the Cα atoms in partial NBD of MsRv1273c (residues G418 to A519) and the mass center of all the Cα atoms in partial NBD of MsRv1272c (residues S380 to D473 and residues P546 to G628). Plots of energy minimization, NVT and NPT equilibration (Supplementary Fig. 17) were performed using qtgrace (https://sourceforge.net/projects/qtgrace/). Visualization was performed using R-4.3.2 (https://www.r-project.org/) and PyMOL. The initial and final configurations as well as an intermediate configuration (t = 36 ns) similar to IFasym-3 by one MD simulation were provided as Supplementary Data 3, 4, 5.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions are present in the main text or Supplementary Materials, and available from the Corresponding Author upon request. The cryo-EM maps of MsRv1273c/72c have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession codes EMD-37450 (IFapo state); EMD-37451 (AMPPNP-bound IFasym-1 state); EMD-38626 (ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state); EMD-38627 (ADP-bound IFasym-3 state (ATP 37 °C treated)); EMD-38628 (ADP-bound IFasym-3 state (ADP 4 °C treated)); EMD-62611 (ATP-bound Occ state); EMD-60789 (ADP-bound IFasym-3 (peptidisc) state (ATP 37 °C treated)); EMD-60790 (ADP-bound IFasym-3 (peptidisc) state (ADP 4 °C treated)); and EMD-60791 [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/emdb/EMD-37491] (ATP | ADP+Vi-bound Occ (Vi) state). The atomic coordinates of MsRv1273c/72c have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes 8WCW (IFapo state); 8WCX (AMPPNP-bound IFasym-1 state); 8XSR (ATP | ADP-bound IFasym-2 state); 8XSS (ADP-bound IFasym-3 state (ATP 37 °C treated)); 8XST (ADP-bound IFasym-3 state (ADP 4 °C treated)); 9KWI (ATP-bound Occ state); 9IQE (ADP-bound IFasym-3 (peptidisc) state (ATP 37 °C treated)); 9IQF (ADP-bound IFasym-3 (peptidisc) state (ADP 4 °C treated)); and 9IQG (ATP | ADP+Vi-bound Occ (Vi) state). The input files of MD simulation are available on Github [https://github.com/qifeng0000001/Rv1272_73MD]. The source data underlying Figs. 1a, c, f-g, and Supplementary Fig. 1a-e, 1h are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Organization, W. H. O. GLOBAL TUBERCULOSIS REPORT. (2023).

Rawat, R., Whitty, A. & Tonge, P. J. The isoniazid-NAD adduct is a slow, tight-binding inhibitor of InhA, the enoyl reductase: Adduct affinity and drug resistance. P Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13881–13886 (2003).

Campbell, E. A. et al. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 104, 901–912 (2001).

Zhang, L. et al. Structures of cell wall arabinosyltransferases with the anti-tuberculosis drug ethambutol. Science 368, 1211–1219 (2020).

Zumla, A., Nahid, P. & Cole, S. T. Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 388–404 (2013).

Akhtar, A. A. & Turner, D. P. J. The role of bacterial ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in pathogenesis and virulence: Therapeutic and vaccine potential. Microb. Pathogenesis 171, 105734 (2022).

Rees, D. C., Johnson, E. & Lewinson, O. ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 218–227 (2009).

Locher, K. P. Mechanistic diversity in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 487–493 (2016).

Davidson, A. L. & Chen, J. ATP-binding cassette transporters in bacteria. Annu Rev. Biochem 73, 241–268 (2004).

Higgins, C. F. Multiple molecular mechanisms for multidrug resistance transporters. Nature 446, 749–757 (2007).

Schmitt, L. & Tampe, R. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 754–760 (2002).

Higgins, C. F. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev. Cell Biol. 8, 67–113 (1992).

Dawson, R. J. & Locher, K. P. Structure of a bacterial multidrug ABC transporter. Nature 443, 180–185 (2006).

Stockner, T., Gradisch, R. & Schmitt, L. The role of the degenerate nucleotide binding site in type I ABC exporters. FEBS Lett. 594, 3815–3838 (2020).

Basso, C., Vergani, P., Nairn, A. C. & Gadsby, D. C. Prolonged nonhydrolytic interaction of nucleotide with CFTR’s NH2-terminal nucleotide binding domain and its role in channel gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 122, 333–348 (2003).

Gao, M. et al. Comparison of the functional characteristics of the nucleotide binding domains of multidrug resistance protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13098–13108 (2000).

Szabó, K., Szakács, G., Hegedüs, T. & Sarkadi, B. Nucleotide occlusion in the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Different patterns in the two nucleotide binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12209–12212 (1999).

Aleksandrov, L., Aleksandrov, A. & Riordan, J. R. Mg2+-dependent ATP occlusion at the first nucleotide-binding domain (NBD1) of CFTR does not require the second (NBD2). Biochem J. 416, 129–136 (2008).

Ueda, K., Komine, J., Matsuo, M., Seino, S. & Amachi, T. Cooperative binding of ATP and MgADP in the sulfonylurea receptor is modulated by glibenclamide. P Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1268–1272 (1999).

Procko, E., O’Mara, M. L., Bennett, W. F., Tieleman, D. P. & Gaudet, R. The mechanism of ABC transporters: general lessons from structural and functional studies of an antigenic peptide transporter. FASEB J. 23, 1287–1302 (2009).

Hohl, M., Briand, C., Grutter, M. G. & Seeger, M. A. Crystal structure of a heterodimeric ABC transporter in its inward-facing conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 395–402 (2012).

Hutter, C. A. J. et al. The extracellular gate shapes the energy profile of an ABC exporter. Nat. Commun. 10, 2260 (2019).

Hohl, M. et al. Structural basis for allosteric cross-talk between the asymmetric nucleotide binding sites of a heterodimeric ABC exporter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11025–11030 (2014).

Noll, A. et al. Crystal structure and mechanistic basis of a functional homolog of the antigen transporter TAP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E438–E447 (2017).

Hofmann, S. et al. Conformation space of a heterodimeric ABC exporter under turnover conditions. Nature 571, 580–583 (2019).

Oldham, M. L., Grigorieff, N. & Chen, J. Structure of the transporter associated with antigen processing trapped by herpes simplex virus. Elife 5, e21829 (2016).

Zhang, Z., Liu, F. & Chen, J. Molecular structure of the ATP-bound, phosphorylated human CFTR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12757–12762 (2018).

Liu, F., Zhang, Z., Csanady, L., Gadsby, D. C. & Chen, J. Molecular Structure of the Human CFTR Ion Channel. Cell 169, 85–95 e88 (2017).

Liu, F. et al. Structural identification of a hotspot on CFTR for potentiation. Science 364, 1184–1188 (2019).

Procko, E., Ferrin-O’Connell, I., Ng, S. L. & Gaudet, R. Distinct structural and functional properties of the ATPase sites in an asymmetric ABC transporter. Mol. Cell 24, 51–62 (2006).

Braibant, M., Gilot, P. & Content, J. The ATP binding cassette (ABC) transport systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 24, 449–467 (2000).

Martin, A. & Daniel, J. The ABC transporter Rv1272c of Mycobacterium tuberculosis enhances the import of long-chain fatty acids in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 496, 667–672 (2018).

Gupta, S. et al. Rv1273c, an ABC transporter of Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes mycobacterial intracellular survival within macrophages via modulating the host cell immune response. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 142, 320–331 (2020).

Adhikary, A., Chatterjee, D. & Ghosh, A. S. ABC superfamily transporter Rv1273c of Mycobacterium tuberculosis acts as a multidrug efflux pump. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 370, fnad114 (2023).

Narang, A. et al. Contribution of putative efflux pump genes to isoniazid resistance in clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J. Mycobacteriol 6, 177–183 (2017).

Ozgur, D., Ersoy, L., Ulger, M., Tezcan Ulger, S. & Aslan, G. Investigation of efflux pump genes in resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis complex clinical isolates exposed to first line antituberculosis drugs and verapamil combination. Mikrobiyol. Bul. 57, 207–219 (2023).

Saeed, D. K. et al. Variants associated with Bedaquiline (BDQ) resistance identified in Rv0678 and efflux pump genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from BDQ naive TB patients in Pakistan. BMC Microbiol 22, 62 (2022).

Kanji, A. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in efflux pumps genes in extensively drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Pakistan. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 107, 20–30 (2017).

Oldham, M. L. & Chen, J. Snapshots of the maltose transporter during ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15152–15156 (2011).

Grossmann, N. et al. Mechanistic determinants of the directionality and energetics of active export by a heterodimeric ABC transporter. Nat Commun 5, 5419 (2014).

Zhu, C. et al. Cryo-EM structures of a prokaryotic heme transporter CydDC. Protein Cell 14, 919–923 (2023).

Thomas, C. & Tampe, R. Structural and mechanistic principles of ABC transporters. Annu Rev. Biochem 89, 605–636 (2020).

Timachi, M. H. et al. Exploring conformational equilibria of a heterodimeric ABC transporter. Elife 6, e20236 (2017).

Thaker, T. M. et al. Asymmetric drug binding in an ATP-loaded inward-facing state of an ABC transporter. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 226–235 (2022).

Qian, H. et al. Structure of the Human Lipid Exporter ABCA1. Cell 169, 1228–1239 e1210 (2017).

Tang, X. et al. Cryo-EM structures of lipopolysaccharide transporter LptB(2)FGC in lipopolysaccharide or AMP-PNP-bound states reveal its transport mechanism. Nat. Commun. 10, 4175 (2019).

Carlson, M. L. et al. The Peptidisc, a simple method for stabilizing membrane proteins in detergent-free solution. Elife 7, e34085 (2018).

Wu, D. et al. Dissecting the conformational complexity and mechanism of a bacterial heme transporter. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 992–1003 (2023).

Fiedorczuk, K. & Chen, J. Molecular structures reveal synergistic rescue of Delta508 CFTR by Trikafta modulators. Science 378, 284–290 (2022).

Beis, K. Structural basis for the mechanism of ABC transporters. Biochem Soc. T 43, 889–893 (2015).

Fan, C. & Rees, D. C. Glutathione binding to the plant AtAtm3 transporter and implications for the conformational coupling of ABC transporters. Elife 11, e76140 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Structural insights into porphyrin recognition by the human ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCB6. Mol. Cells 45, 575–587 (2022).

Mastronarde, D. N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 36–51 (2005).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Rosenthal, P. B. & Henderson, R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 (2003).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. D. et al. Advances, interactions, and future developments in the CNS, Phenix, and Rosetta structural biology software systems. Annu Rev. Biophys. 42, 265–287 (2013).

Williams, C. J. et al. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315 (2018).

Geertsma, E. R., Mahmood, N. A. B. N., Schuurman-Wolters, G. K. & Poolman, B. Membrane reconstitution of ABC transporters and assays of translocator function. Nat. Protoc. 3, 256–266 (2008).

Verchère, A., Broutin, I. & Picard, M. in Membrane Protein Structure and Function Characterization: Methods and Protocols (ed Jean-Jacques Lacapere) 259-282 (Springer New York, 2017).