Abstract

Solid-state lithium metal batteries using garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12 electrolytes hold immense promise for next-generation energy storage, but grain boundary defects promote lithium redistribution and dendrite formation, compromising performance and safety. To address this, we investigate lithium behavior at these boundaries using machine learning potentials and molecular dynamics simulations. Energy minimization drives lithium accumulation or depletion at grain boundaries depending on cavity fraction and local lithium concentration. Crack-like boundary voids facilitate lithium protrusions and dendrites at the electrolyte/negative electrode interface, increasing short-circuit risks. Controlled grain boundary melting achieves selective amorphization while preserving bulk crystallinity. This structural modification slightly reduces ionic conductivity but enhances interfacial electronic and mechanical properties, suppressing lithium aggregation and alleviating interfacial protrusions. In this work, we demonstrate how grain boundary structures govern lithium redistribution dynamics and dendrite formation mechanisms. We further propose targeted grain boundary amorphization as an effective strategy to engineer robust solid-state electrolyte microstructures that improve battery cyclability and safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of portable electronics and electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become vital energy storage systems1,2,3. However, the flammable organic liquid electrolytes pose serious safety hazards, hindering their widespread applications4,5. All-solid-state lithium metal batteries, employing chemically stable solid electrolytes, offer a promising solution to these safety issues while also enhancing energy density through the utilization of lithium metal negative electrode6. Among the solid electrolytes, the garnet-type oxide Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO) has garnered significant attention due to its wide electrochemical window, high lithium-ion conductivity, and desirable mechanical properties7,8,9,10,11.

Despite these promising attributes, several challenges hinder the mass production and practical implementation of LLZO-based batteries12,13,14,15,16,17. A critical issue is the growth of lithium dendrites during cycling, which can penetrate the LLZO electrolyte, causing internal short circuits18,19,20,21. Current research efforts have predominantly focused on two main perspectives regarding lithium dendrite formation. Firstly, the electronic properties of LLZO contribute to non-uniform lithium plating at the LLZO/Li interface due to charge inhomogeneity and surface roughness22,23,24. Promisingly, introducing buffer layers has been shown to mitigate this issue24,25,26. Secondly, electronic leakage currents originating from electronic transport at LLZO grain boundaries (GBs) are facilitated by the segregation of reduced species (e.g., Zr3O, La2O3) with smaller bandgaps27. Additionally, lithium ions may segregate at GBs, promoting localized lithium reduction and filament formation within the GB, which can accumulate and lead to short circuits28,29,30.

The GBs in LLZO pose several additional challenges. Interfacial space charge effects and strain fields associated with the GBs can obstruct lithium-ion transport, leading to local resistance buildups31,32. The varying ionic transport kinetics across GBs can induce lithium redistribution and heterogeneous deposition during cycling33,34. The GBs are also more susceptible to mechanical degradation and structural disordering, posing risks of microcracking that can compromise the integrity and ionic conductivity of the solid electrolyte35,36.

Experimental characterization of GB microstructural evolution and its impact on ionic/electronic conduction has proven challenging due to limitations in available characterization technique27,37. Fortunately, the recent rapid development of machine learning interatomic potentials has enabled accurate simulations of mesoscale structural models, offering insights into these phenomena38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

In this study, we investigated the LLZO GB model using machine learning interatomic potentials. Lithium segregation at GBs is driven by the formation of an unstable interface, prompting the system to minimize energy by segregating lithium to reduce the GB/bulk energy difference. For certain GBs, significant lithium accumulation occurs, exhibiting high Li-Li coordination conducive to dendrite nucleation. By controlling heating to induce preferential GB melting, followed by vitrification, we obtain GB-free LLZO. While exhibiting a slight conductivity reduction, this amorphous GB approach effectively suppresses lithium agglomeration and mitigates cracking, addressing a key challenge for realizing high-performance LLZO solid electrolytes.

Results

Lithium-ion segregation at grain boundaries

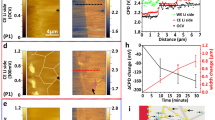

GB segregation, which refers to the uneven distribution of chemical compositions between neighboring grains in solid materials, significantly impacts mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, fatigue performance, and thermal stability. The GB models are symmetric tilt grain boundaries with the [100] orientation. The initial Li concentration at the GBs was not explicitly controlled; instead, it was determined by the number of Li atoms exposed on the cut surfaces of the materials, which were then symmetrically rejoined. We removed any atoms that were too close to each other to avoid unphysical overlap. The main difference between GB-model-1 and GB-model-2 is the chemical composition at the GB, as the element distribution at the GB varies between the two models. The structural diagram of model 1 is shown in Fig. 1a and investigated lithium segregation at the GBs using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. (see Supplementary Data 1 and 2 for the initial and final atomic configurations from the MD simulations) The model was segmented into eleven regions along the z-axis. Figure 1b, c track the number of lithium in different regions of two GB models over time. A statistical analysis of lithium-ion distribution per unit thickness in various regions during the final 50 ps, as depicted in Fig. 1d, reveals significant segregation at the GBs, with lithium-ion accumulation in GB-Model-1 and depletion in GB-Model-2.

a Distribution of regions in the GB model; Blue represents the Li-O polyhedron, purple indicates the La-O polyhedron, and green corresponds to the Zr-O polyhedron; b Eolution of the number of Li over time in the GB-model-1; c Evolution of the number of Li over time in theGB-model-2; d Distribution of the number of Li in different regions within the GB model at the final state; e Relationship between Li cavity fraction and segregation. The measure of centre is the mean values, error bars represent the Standard Deviation (n = 1000).

Supplementary Fig. 5 displays the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) of lithium within 1000 ps for two distinct GB models. It’s evident that the MSD curves initially exhibit a steep slope followed by a gradual decrease, eventually stabilizing into a linear trend. The linearity of the MSD curve from 300 ps onwards suggests that grain boundary segregation is complete, corroborated by the stabilization of lithium ion quantities at the grain boundary observed in Fig. 1b at 300 ps. The variation in the slope of the MSD curve reflects the ongoing segregation process at the grain boundary. This phenomenon can be attributed to the initial instability of the GB structure and the unimpeded diffusion of Li within LLZO, prompting the redistribution and equilibration of lithium throughout the system.

The presence of GBs induces energy non-uniformity, driving lithium segregation to achieve overall energy equilibrium. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6, before segregation, the energy per atom on the grain boundary is higher than that in the bulk phase. However, the system tends to develop towards a state of equilibrium, so the grain boundary will achieve a reduction in energy per atom by gaining or losing lithium ions. At the same time, the bulk structure itself is a relatively stable state, but its loss or gain of Li will cause its energy to rise. Finally, the energy per atom on the grain boundary is the same as that in the bulk phase, and equilibrium is achieved.

The difference in segregation behavior between GB-model-1 and GB-model-2 is primarily due to the variation in elemental composition at the GB, which affects the local Li cavity fraction. We have calculated the Li cavity fraction at the GBs for Model-1, Model-2, and several other models. The methodology for calculating the cavity fraction is detailed in Supplementary Note 3. As shown in Fig. 1e, there is a clear correlation between Li cavity fraction and the degree of segregation: as the cavity fraction increases, the amount of segregated lithium also increases. A higher Li cavity fraction indicates that more lithium needs to fill the available voids at the GBs in order to reach a relatively stable configuration. When the porosity is small, the system can only achieve energy reduction by losing Li. The results shown in Fig. 1e are based solely on [100] symmetric tilt boundaries. To verify the generality of our findings, we have supplemented our analysis with [110] and [210] symmetric tilt boundaries. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 12, these additional models exhibit the same trend, further supporting the robustness of our conclusions.

In Supplementary Fig. 7, all canonical ensemble (NVT) data were obtained after heating the system to the target temperature using an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, followed by 500 ps of NVT simulation. At temperatures above 500 K, lithium-ion diffusion becomes significantly enhanced, allowing the system to complete the segregation process within the 500 ps simulation time. However, at lower temperatures (e.g., 300 K), this duration was insufficient for full segregation to occur, which resulted in underestimating the amount of segregated lithium at 300 K.

To verify this, we compared the structure obtained at 500 K (which exhibited more lithium segregation) with the structure obtained at 300 K, both equilibrated at 300 K. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, the structure with more segregated lithium remained more stable at 300 K. This confirms that the amount of lithium segregated at 300 K is higher than what was initially captured in our NVT simulation data.

The NPT data in Supplementary Fig. 7 were obtained by equilibrating the structure at 500 K, followed by slowly cooling the system to 300 K at a rate of 0.0002 K/fs using the NPT ensemble. As the temperature decreased, the degree of lithium segregation continued to increase, indicating that segregation progresses further as the system cools.

Full cell model construction

To further analyze the structural evolution at GBs during discharge processes and the impact brought by GBs, we constructed a full battery model. The negative electrode of this model consists of lithium metal, while the positive electrode materials selection is limited to elements capable of undergoing changes in oxidation states. LiZr2O4 (LZO) was chosen due to its ability to change oxidation states, as illustrated in Fig. 2a for its structure and Fig. 2b for its discharge voltage. Crystal lattice information of LZO as shown in Supplementary Note 5 (Refer to Supplementary Data 3 and 4 for the atomic configurations of fully delithiated and undelithiated LZO).

a Structure of LZO before and after discharge; b Discharge voltage curve of LZO; c Structural model of Li|LLZO | LZO. d Evolution of the number of Li at the negative electrode and positive electrode during discharge; e Discharge rate for different LLZO thicknesses; f Changes in the number of Li in the GB-model and Li|LLZO | LZO-model; g The Li distribution of the Li|LLZO-GB | LZO model projected on the yz-plane; h Evolution of the number of Li along the z-axis over time.

The schematic diagram in Fig. 2c represents the Li|LLZO | LZO full battery structure we developed. In Fig. 2d, the variation in the number of lithium atoms in the positive electrode and negative electrode indicates the discharge rate. Figure 2e demonstrates the impact of LLZO with different thicknesses on the discharge rate. (see Supplementary Data 7–14 for the initial and final atomic configurations of full battery models with different thicknesses) Fig. 2f illustrates the lithium-ion distribution in various regions of the GB model over the first 1000 ps, with subsequent 2000 ps showing variations after integrating the GB model into the Li|LLZO | LZO full battery model. Initially, lithium-ion aggregation at the GB decreases the number of lithium in the bulk region. However, as discharge progresses, the bulk phase sees replenishment while lithium-ion aggregation at the GBs continues to increase, resulting in some lithium loss in the LLZO electrolyte after the first charge-discharge cycle.

Figure 2g presents the Li element distribution in the yz-plane during the discharge process of the Li|LLZO | LZO full battery model over various time intervals, while Fig. 2h illustrates lithium element distribution in the z-direction. These figures depict the gradual thinning of the lithium metal negative electrode, concurrent with the intercalation of lithium into the LZO positive electrode. (see Supplementary Data 5 and 6 for the initial and final atomic configurations from the MD simulations) Additionally, the GB region accumulates significantly more lithium compared to the bulk phase region.

Impact of GB orientations during discharge

The influence of GBs on lithium diffusion in solid-state electrolytes is evident, with varying effects depending on different GB configurations. To investigate this, we constructed three models: Model 0, representing a complete battery without GB; Model 1, in which the GB is parallel to the LLZO/Li interface; and Model 2 where GB is vertical to the LLZO/Li interface, as shown in Fig. 3a. (For the initial and final atomic configurations of the MD simulation of the full battery model with different grain boundaries, see Supplementary Data 15–20) In Fig. 3b, the discharge rates of the three models are compared, indicating that the absence of GBs results in the fastest lithium ion diffusion, while the horizontal GB exhibits the slowest diffusion. Figure 3c shows the distribution of Li density on the y-z plane of Model-1 and Model-2 at 2 ns. It can be found that there is a higher Li density on the GB of Model-2.

a Schematic diagrams of the three Li|LLZO-GB | LZO models; b Discharges in the number of Li at the positive electrode; c Projection of the Li density distribution on the yz-plane for Model-0 and Model-2 at 2 ns; d Contour plot of the projection of the migration velocity on the yz-plane for Model-1; e Contour plot of the projection of the migration velocity on the yz-plane for Model-2; f Projection of the Li density distribution on the yz-plane for Model-0; g Projection of the Li density distribution on the yz-plane for Model-2s.

Figure 3d and Fig. 3e respectively depict the distances migrated by lithium per picosecond in Model-1 and Model-2 at different stages, reflecting the migration velocity of lithium in these regions. Specifically, in Model-1, where the GB is oriented horizontally, lithium migration from the negative electrode to the positive electrode necessarily involves crossing the GB, resulting in a higher migration rate within the GB compared to Model-2. In contrast, in Model-2, where the GB is vertically oriented, lithium can migrate through the bulk region without interacting with the GB as frequently, leading to a lower lithium density at the GB.

We also constructed a model with a larger cavity fraction compared to model-2. Through 2 ns MD simulation, Fig. 3f, g depict the density distribution of lithium in the yz-plane for Model-0 and Model-2s. It is evident that in Model-2s, a protrusion appears at the LLZO/Li interface at 0.5 ns, followed by the emergence of a conical region after 2 ns, while such phenomena are absent in Model-0. At the same time, from the comparison between Model-2 in Fig. 3c and Model-2s in Fig. 3g, it can be observed that, although no significant protrusion region is observed in Model-2, the LLZO/Li interface is not as flat as in Model-0 and Model-1. This indicates that the interface in Model-2 is relatively unstable similar to Model-2s, making it more prone to lithium dendrite formation, which could lead to internal short circuits and thermal runaway, posing safety risks. Additionally, electrolyte cracking disrupts continuity, leading to decreased conductivity and reduced battery cycling stability.

In situ amorphization by heating

Figure 4a depicts the schematic diagram of the Li|LLZO-GB | LZO full battery model, where Layer-2 and Layer-3 indicate the melted GB region forming amorphous LLZO (a-LLZO). (see Supplementary Data 21–28 for the initial and final atomic configurations from the MD simulations) Fig. 4b shows the migration rates of the four models. After 4 ns, while the number of embedded Li ions remains roughly consistent, Layer-0 and Layer-1 models exhibit faster migration rates compared to Layer-2 and Layer-3. This is mainly due to the generally lower lithium-ion conductivity in a-LLZO. The number of lithium within the box regions of the four models is presented in Fig. 4c. Notably, the number of lithium at the GB in Layer-1 is substantially higher, which greatly facilitates the formation of lithium dendrites. In addition, the number of lithium in the layer-2 and layer-3 is slightly higher than that in the layer-0, which is caused by the process we modeled. This is because we first simulate the grain boundary model of LLZO dynamically, and then it will segregate, and a large number of lithium ions will appear on the grain boundary. Then we melt this part of the grain boundary area, so the amorphous lithium content obtained is naturally higher than the bulk level. The RDF of Li-Li in this region is shown in Fig. 4d (see Supplementary Data 29–31 for the initial and final atomic configurations from the MD simulations).

a Schematic Diagram of Li|LLZO-GB | LZO; b Discharges in the number of Li at the positive electrode; c Evolution of the number of Li inside the box over time; d RDF of Li-Li inside the box; RDF of Li-Li and Li-O in e c-LLZO; f a-LLZO; Relationships between Li-Li and Li-O Coordination Numbers in g c-LLZO; h a-LLZO; i Classification of Li-Li Coordination Numbers in Layer-0; Relationships between Li-Li and Li-O Coordination Numbers in (j) Layer-0; k Layer-1; l Layer-3.

There are two types of Li in LLZO, 24 d and 96 h sites, and their Li-Li coordination numbers are 4 and 6, respectively. In the kinetic process, there will be some intermediate states with a coordination number of 5, and the coordination number of Li-O is also similar. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish the type of Li only by the coordination number of Li-Li or Li-O. Therefore, we correlate Li-Li and Li-O to comprehensively analyze the type of Li.

Figure 4e, f illustrate the RDFs of cubic LLZO (c-LLZO) and stoichiometric a-LLZO, respectively. (see Supplementary Data 32– 34 for the initial and final atomic configurations from the MD simulations) Using peak valley of Li-Li and Li-O in c-LLZO as cutoffs distances, coordination numbers for Li-Li and Li-O were calculated for all lithium in c-LLZO and a-LLZO, presented in Fig. 4g, h. Notably, two distinct regions can be observed in Fig. 4g, corresponding to two types of lithium occupying the 24 d and 96 h sites in c-LLZO. We classified the RDFs of these two types of lithium according to their regions and calculated the RDFs of different lithium-ion types based on their proportions, as shown in Fig. 4i. The RDF of metallic Li is also provided. Only one type of lithium ion, distinct from that in c-LLZO, exists in a-LLZO.

Further analysis of Li-Li and Li-O coordination numbers in various Li|LLZO-GB | LZO models is shown in Fig. 4j–l. Figure 4j reveals that the distributions in Layer-0 and c-LLZO are similar, whereas in Layer-1, in addition to the two Li types present in c-LLZO, there is also a third type of lithium ion, different from that in a-LLZO. The third lithium-ion type in Layer-1 exhibits a higher Li-Li coordination number and a lower Li-O coordination number, indicating severe aggregation of these lithium. In Fig. 4l, it can be observed that Layer-3 also contains only one type of lithium ion, but its Li-Li coordination number is slightly higher than that in a-LLZO, primarily due to the higher lithium-ion concentration in this amorphous region.

Grain boundaries amorphization suppress Li dendrite formation

In the previous section, our calculations indicated that GBs can be amorphized by heating. To further illustrate the efficacy of appropriate amorphization in suppressing lithium dendrite formation, we devised a more intricate GB model, depicted in Fig. 5a. Through MD simulations at varying temperatures, energy changes were monitored, as depicted in Fig. 5c. Notably, at 800 K, the energy quickly stabilizes, while at 1800K, continuous energy increase suggests ongoing crystal-to-amorphous transformation, with preferential melting of GBs due to their instability and higher resistance.

a Schematic of the GB model composition; b Model-GB represents the Li|LLZO-GB | LZO model and Model-A represents the Li|LLZO-A | LZO model; c Energy change of GB at different temperatures; d Distribution of Zr-O polyhedral and lithium ion density in the GB model; e Distribution of Zr-O polyhedral and lithium ion density in the amorphized GB model; f Lithium density distribution at different times for Model-GB; g Lithium density distribution at different times for Model-A.

From Fig. 5d, it can be observed that there are regions on the GBs not occupied by Zr-O polyhedral. The corresponding lithium-ion density distribution maps show that lithium tend to aggregate in these regions. The amorphized GB model, shown in Fig. 5e, exhibits a more uniform distribution of Zr-O polyhedral, resulting in a correspondingly uniform lithium-ion distribution.

Furthermore, we conducted simulations on the full battery model, and the lithium density distributions after simulation are shown in Fig. 5f and g. It can be observed that in the Model-GB model, after discharge, the lithium-ion density at the grain boundaries further increases, indicated by the appearance of red regions. At the LLZO/Li interface, significant lithium aggregation leads to the formation of a protrusion, which can be observed in the model. In contrast, in the amorphized Model-A, there is no noticeable lithium aggregation, and the protrusion is absent, indicating that the lithium ions are more evenly distributed.

Mechanism of inhibiting lithium dendrite formation

We further analyze the fundamental reason why grain boundary amorphization can inhibit the formation of lithium dendrites. First, we apply strains to the two structural models in Fig. 6a to cause them to deform at a certain rate. The tensile stress-strain curve is shown in Fig. 6b. It can be found that when the strain of LLZO-GB has not reached 10%, the stress decreases rapidly, which corresponds to structural cracking. For the LLZO-Amorphous system, a strain of 15% can be achieved. This will allow it to better alleviate the strain caused during the process of transporting lithium and inserting Li, ensuring interface stability.

In the actual charging process, electrons reach the lithium metal negative electrode from the external circuit and then reduce Li ions to lithium metal at the LLZO/Li interface. So, we want to calculate how these extra electrons are distributed when they exist in the system, and the schematic diagram of our calculated model is shown in Fig. 6c. (see Supplementary Data 35 for LLZO/Li structure containing LLZO-GB/Li and LLZO-A/Li interfaces) The distribution of charge density is shown in Fig. 6d, which includes the charge density distribution on the three interfaces of LLZO-GB/Li, LLZO-A/Li and LLZO/Li. It can be seen from the figure that the charge density in the LLZO-GB/Li region is significantly higher than that in other regions, while the charge distribution in the LLZO-A/Li region is more uniform. This shows that the amorphization of the grain boundary can effectively make the charge density distribution on the interface in contact with Li metal more uniform. It will also lead to the risk of cracking the interface. The distribution of lithium and electrons in the amorphized modified area is more uniform, which makes the reduction of lithium metal very uniform and effectively inhibits the formation of lithium dendrites, as shown in Fig. 6e.

Discussion

This study utilized machine learning interatomic potentials to explore the impact of GBs on lithium segregation and dendrite formation in the solid-state electrolyte LLZO. MD simulations indicated spontaneous lithium accumulation or depletion at GBs driven by energy minimization, with segregation influenced by temperature and bulk lithium concentration. Lower temperatures and higher lithium levels exacerbated segregation.

In full cell Li|LLZO-GB | LZO models, horizontal GBs significantly hindered lithium migration compared to vertical GBs. GBs with crack-like voids enabled lithium protrusions at the LLZO/Li interface, facilitating dendrite nucleation that could cause short circuits. Controlled heating above the GB melting point induced preferential GB amorphization while maintaining the bulk crystalline structure. Although reducing overall ionic conductivity slightly, the amorphous GBs prevented severe lithium aggregation and mitigated lithium metal protrusions at the electrolyte/lithium interface. We illustrate how grain boundary amorphization inhibits the formation of lithium dendrites from microscopic electronic properties and mesoscopic mechanical properties.

Overall, our research has profound implications for the further development of solid-state electrolytes and the realization of all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. First, we have revealed the mechanism of lithium-ion segregation and dendrite growth caused by grain boundaries in solid-state electrolytes, from the microscopic to the mesoscopic scale, providing an important theoretical basis for better designing and optimizing the microstructure of solid-state electrolytes. Second, through the strategy of grain boundary amorphization, we have provided an effective means to overcome the safety risks caused by lithium dendrite growth, laying the foundation for achieving high-performance solid-state batteries. Our research results will help promote the development of clean energy technologies and contribute to the reliable storage and utilization of sustainable energy.

Methods

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations were conducted by using the projector augmented wave (PAW)45,46 method within density functional theory (DFT) framework as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)47,48, employing the spin-polarized generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)49 parameterization for the electronic exchange-correlation functional. Convergence criteria included energy minimization to 10−4 eV for the unit cell and 0.1 eV/Å for atom force relaxation. Gaussian smearing with 0.05 eV width determined electronic occupancies. Wave functions were expanded in plane waves up to a kinetic energy cut-off of 500 eV. Brillouin-zone integrations were approximated by using special k-point sampling with a k-point mesh resolution of 0.25 \({{{{\text{\AA}} }}}^{-1}\). Excess electrons were added to the system to achieve electron oversaturation23,50,51. Charge density calculations as shown in Supplementary Note 4.

DP training details

The DeePMD-Kit52 package employs smoothing during DP model training, with a cutoff radius of 6.0 Å for adjacent atoms and gradual inverse distance smoothing from 0.5 Å to 6 Å. The filtering neural network has three hidden layers [10, 20, 40], and the fitting network has [120, 120, 120]. Random parameter initialization is used, with 6,000,000 training steps using the Adam stochastic gradient descent method with a starting learning rate of 0.001, exponentially decreasing with a decay step of 2000 and decay rate of 0.996.

Deep potential molecular dynamics simulations

The reliability of the machine learning potential function obtained through training has been demonstrated in previous studies53,54, as shown in Supplementary Note 1. The Deep Potential Molecular Dynamics (DeePMD) simulations are performed within the LAMMPS software package using the well-trained DP-model. 3D periodic conditions are applied. The DeePMD simulations are performed at 300, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000, 1100, and 1800 K, and the pressure is set to be 0 bar to study temperature and pressure effects on the interface reaction. Throughout the simulation, we used NPT to reach the target temperature at a rate of 0.02 K/fs and then used the NVT ensemble to equilibrate the system at the target temperature for at least 500 ps to reach equilibrium. A time step of 1 fs is used to integrate Newton’s equations of motion. The realization process of grain boundary amorphization as shown in Supplementary Note 2.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the main text, supplementary information files and supplementary data files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The machine learning training potential function adopts the open source DeePMD-kit code(https://github.com/deepmodeling/deepmd-kit). All molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the open source LAMMPS code (https://github.com/lammps/lammps).

References

Yang, Z. et al. Electrochemical energy storage for green grid. Chem. Rev. 111, 3577–3613 (2011).

Diouf, B. & Pode, R. Potential of lithium-ion batteries in renewable energy. Renew. Energy 76, 375–380 (2015).

Janek, J. & Zeier, W. G. Challenges in speeding up solid-state battery development. Nat. Energy 8, 230–240 (2023).

Armand, M. & Tarascon, J. M. Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008).

Etacheri, V., Marom, R., Elazari, R., Salitra, G. & Aurbach, D. Challenges in the development of advanced Li-ion batteries: a review. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3243–3262 (2011).

Monroe, C. & Newman, J. The effect of interfacial deformation on electrodeposition kinetics. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151, 880–886 (2004).

Thangadurai, V. & Weppner, W. Li6ALa2Ta2O12 (A = Sr, Ba): novel garnet-like oxides for fast lithium ion conduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 15, 107–112 (2005).

Samson, A. J., Hofstetter, K., Bag, S. & Thangadurai, V. A bird’s-eye view of Li-stuffed garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12 ceramic electrolytes for advanced all-solid-state Li batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2957–2975 (2019).

Zhao, N. et al. Solid garnet batteries. Joule 3, 1190–1199 (2019).

Huang, X. et al. Manipulating Li2O atmosphere for sintering dense Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 22, 207–217 (2019).

You, Y. et al. Exploring high-valence element doping in LLZO electrolytes: effects on phase transition and lithium-ion conductivity. J. Power Sources 612, 234831 (2024).

Ohta, S., Kobayashi, T., Seki, J. & Asaoka, T. Electrochemical performance of an all-solid-state lithium ion battery with garnet-type oxide electrolyte. J. Power Sources 202, 332–335 (2012).

Banerjee, A., Wang, X., Fang, C., Wu, E. A. & Meng, Y. S. Interfaces and interphases in all-solid-state batteries with inorganic solid electrolytes. Chem. Rev. 120, 6878–6933 (2020).

Park, K. et al. Electrochemical nature of the cathode interface for a solid-state lithium-ion battery: interface between LiCoO2 and garnet-Li7La3Zr2O12. Chem. Mat. 28, 8051–8059 (2016).

Ma, C. et al. Interfacial stability of Li metal-solid electrolyte elucidated via in situ electron microscopy. Nano Lett. 16, 7030–7036 (2016).

Rettenwander, D. et al. Interface instability of Fe-stabilized Li7La3Zr2O12 versus Li metal. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 3780–3785 (2018).

Li, Y., Cao, Y. & Guo, X. Influence of lithium oxide additives on densification and ionic conductivity of garnet-type Li6.75La3Zr1.75Ta0.25O12 solid electrolytes. Solid State Ion. 253, 76–80 (2013).

Cheng, E. J., Sharafi, A. & Sakamoto, J. Intergranular Li metal propagation through polycrystalline Li6.25Al0.25La3Zr2O12 ceramic electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 223, 85–91 (2017).

Liu, G., Wang, D., Zhang, J., Kim, A. & Lu, W. Preventing dendrite growth by a soft piezoelectric material. ACS Mater. Lett. 1, 498–505 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Incorporating ionic paths into 3D conducting scaffolds for high volumetric and areal capacity, high rate lithium-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801328 (2018).

Raj, V. et al. Direct correlation between void formation and lithium dendrite growth in solid-state electrolytes with interlayers. Nat. Mater. 21, 1050–1056 (2022).

Han, F. et al. High electronic conductivity as the origin of lithium dendrite formation within solid electrolytes. Nat. Energy 4, 187–196 (2019).

You, Y. et al. Effect of charge non-uniformity on the lithium dendrites and improvement by the LiF interfacial layer. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 15078–15085 (2022).

Luo, L. et al. Solid-state lithium batteries with ultrastable cyclability: an internal-external modification strategy. ACS Nano 18, 2917–2927 (2024).

Huo, H. et al. A flexible electron-blocking interfacial shield for dendrite-free solid lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 12, 176 (2021).

Ruan, Y. et al. A 3D cross‐linking lithiophilic and electronically insulating interfacial engineering for garnet‐type solid‐state lithium batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007815 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Local electronic structure variation resulting in Li ‘filament’ formation within solid electrolytes. Nat. Mater. 20, 1485–1490 (2021).

Tantratian, K., Yan, H., Ellwood, K., Harrison, E. T. & Chen, L. Unraveling the Li penetration mechanism in polycrystalline solid electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003417 (2021).

Biao, J. et al. Inhibiting formation and reduction of Li2CO3 to LiCx at grain boundaries in garnet electrolytes to prevent Li penetration. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208951 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Dendrite formation in solid-state batteries arising from lithium plating and electrolyte reduction. Nat. Mater. 24, 581–588 (2025).

Gu, Z. et al. Atomic-scale study clarifying the role of space-charge layers in a Li-ion-conducting solid electrolyte. Nat. Commun. 14, 1632 (2023).

Gao, B., Jalem, R., Tian, H. K. & Tateyama, Y. Revealing atomic‐scale ionic stability and transport around grain boundaries of garnet Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2102151 (2021).

Dawson, J. A., Canepa, P., Famprikis, T., Masquelier, C. & Islam, M. S. Atomic-scale influence of grain boundaries on Li-ion conduction in solid electrolytes for all-solid-state batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 362–368 (2018).

Yu, S. & Siegel, D. J. Grain boundary contributions to Li-ion transport in the solid electrolyte Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO). Chem. Mat. 29, 9639–9647 (2017).

Ji, W. et al. Revealing the influence of surface microstructure on Li wettability and interfacial ionic transportation for garnet-type electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300165 (2023).

Fu, Z. et al. Probing the mechanical properties of a doped Li7La3Zr2O12 garnet thin electrolyte for solid-state batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 24693–24700 (2020).

Sharafi, A., Haslam, C. G., Kerns, R. D., Wolfenstine, J. & Sakamoto, J. Controlling and correlating the effect of grain size with the mechanical and electrochemical properties of Li7La3Zr2O12 solid-state electrolyte. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5, 21491–21504 (2017).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & Weinan, E. DeePMD-kit: A deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Zhang, L., Wang, H., Car, R. & Weinan, E. Phase diagram of a deep potential water model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 236001 (2021).

Calegari Andrade, M. F., Ko, H. Y., Zhang, L., Car, R. & Selloni, A. Free energy of proton transfer at the water-TiO2 interface from ab initio deep potential molecular dynamics. Chem. Sci. 11, 2335–2341 (2020).

Tang, L. et al. Development of interatomic potential for Al-Tb alloys using a deep neural network learning method. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 18467–18479 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Precisely tunable instantaneous carbon rearrangement enables low-working-potential hard carbon toward sodium-ion batteries with enhanced energy density. Adv. Mater. 36, 2407369 (2024).

Gu, J. et al. Creating rich closed nanopores in anthracite-derived soft carbon enables greatly-enhanced sodium-ion storage in the low-working-voltage region. Chem. Eng. J. 505, 159331 (2025).

Huang, L. et al. Nanoscale precision welding-enabled quasi-3D conductive carbon blacks for fast-charging and long-lasting secondary batteries. Carbon 230, 119688 (2024).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmiiller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Andres, J. et al. Structural and electronic analysis of the atomic scale nucleation of Ag on alpha-Ag2WO4 induced by electron irradiation. Sci. Rep. 4, 5391 (2014).

Tian, H.-K., Xu, B. & Qi, Y. Computational study of lithium nucleation tendency in Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO) and rational design of interlayer materials to prevent lithium dendrites. J. Power Sources 392, 79–86 (2018).

Zhang, L., Han, J., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. Deep potential molecular dynamics: a scalable model with the accuracy of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 143001 (2018).

You, Y. et al. Principal component analysis enables the design of deep learning potential precisely capturing LLZO phase transitions. NJP Comput. Mater. 10, 57 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Exploring the relationship between composition and Li-ion conductivity in the amorphous Li–La–Zr–O system. ACS Mater. Lett. 6, 1849–1855 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.11874307, S.Q.W; 12374015, S.Q.W; 42374108, Y.S), Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen (Grant No. 3502Z202371007, Y.S) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 20720230014, Y.S). Shaorong Fang and Tianfu Wu from Information and Network Center of Xiamen University are acknowledged for their help with the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) computing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Q. W. and Y.W.Y. conceived the project. Y. W. Y. and D.X.Z. contributed to the training of potential functions. Y.W.Y. performed all simulation calculations. Z.F.W. provides some code for processing data. T.Y.L., X.R.C., Y.S., and Z.Z.Z. provided guidance for this work. Y.W.Y. wrote the manuscript and S.Q.W. made detailed modifications to this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xinghua Shi, Bo Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, Y., Zhang, D., Wu, Z. et al. Grain boundary amorphization as a strategy to mitigate lithium dendrite growth in solid-state batteries. Nat Commun 16, 4630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59895-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59895-9