Abstract

Aqueous Zn ion batteries are advantageous in terms of safety and cost, while their sustainable applications are usually impeded by dendrite growth and interfacial side reactions. Here, we present the development of an electrochemically driven artificial solid-state electrolyte interphase, utilizing a metal surface coupling agent phosphate ester as a protective layer for Zn negative electrodes. Upon cycling, the protective layer in situ transforms into a hybrid phase enriched with well dispersed Zn3(PO4)2 nanocrystals. This transformation ensures a uniform Zn2+ flux, effectively suppresses dendrite growth, and mitigates side reactions. In addition, such protective layer ensures Zn electrode stable plating/stripping performance for 1500 h at 10 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2, while pouch cells coupled with NaV3O8·1.5H2O deliver ampere-hour level capacity. Beyond that, its robust adhesion and flexibility enable the Zn electrode to maintain good performance under a variety of harsh conditions. This approach provides valuable insights into the advancement of Zn metal batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-cost and intrinsic safety aqueous zinc metal batteries (AZMBs) are one of the most promising candidates for sustainable energy storage1,2. In practical, robust Zn negative electrodes are required for constructing AZMBs applicable to multi-scenario applications, but unfortunately, runaway dendrite growth, electrochemical corrosion and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) are inescapable3,4,5,6. The disordered growth of high modulus Zn dendrites along vertical direction should be restrained, especially at the bending and pressing states. Otherwise, it will accelerate the collapse of the interphase structure and cause the battery to disconnect, or pierce the separator and short-circuit the battery7,8,9. In addition, those undesirable side reactions at electrode-electrolyte interphase need to be effectively suppressed, especially under the fast-charging and extreme temperature conditions. Since these harsh conditions will catalyze the H2 production and surface corrosion, or weaken the interfacial reaction kinetics10,11,12. Therefore, the electrochemical performance and scope of application of the AZMBs are greatly determined by the compatibility of Zn|electrolyte interphase.

Generally, the pre-implantation of artificial solid-state interphase (ASSI) is recognized as a feasible and economic strategy to regulate the compatibility of Zn|electrolyte interphase. Among them, organic polymer-based routes such as poly(vinyl butyral)13, poly(vinyl alcohol)14, polyacrylonitrile15 have been demonstrated to inhibit the side reactions and boost the cycle lifespan of Zn metal anodes. However, their common problems are the poor robustness and sluggish ion transport properties, as well as large polarization effect.16,17 That means, it is often done at the expense of rate performance to prolong the cycle lifespan. In addition, such exchange benefit will be greatly reduced when the operating conditions are fast charging and/or extreme temperature environments. Besides, once dendrites are locally formed, the tip effect induces high hardness dendrites to eventually puncture the soft polymer interphase. Alternatively, for the inorganic compound-dominated cases18,19,20,21, although ionic conductors can boost the ion transport, the physical mixing-induced low dispersion and agglomeration will disturb the ion flux distribution and inner stress distribution of the interfacial layer. Thus, the large accumulated stress will lead to the separation and shedding of two phases during the long-term cycle.22,23,24 Furthermore, such mentioned adverse factors will be greatly amplified under bending and/or pressing conditions. Based on the current research progress, how to build a robust ASSI that is compatible with multiple working conditions including fast-charging, wide-temperature, and bending-, pressure-tolerance should be a big challenge in the research field of AZMBs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, establishing a reasonable evaluation system from different physicochemical properties is also necessary for ASSI research.

In this report, inspired by its extensive application in metal coating adhesives, an electrochemically driven artificial solid-state electrode interphase (SEI) strategy was proposed by a simple 2-methyl-2-acrylate-2-hydroxyethyl ester phosphate ester (MAHEPE) scraping, to design robust Zn negative electrode applied for multi scenario applications of ZMBs. In detail, during the initial electrochemical cycling, the electric field drives Zn2+ to migrate through the PO43−-rich organic coating, where they coordinate with PO43− to nucleate highly dispersed Zn3(PO4)2 nanocrystals. This dynamic process facilitates the in-situ evolution of an organic/inorganic hybrid interfacial phase. Although organic electrolyte additives such as trimethyl phosphate25, succinimide26, and poloxamers27, have been recently proved as effective mediators to regulate the Zn|electrolyte interphase chemistry. In contrast to electrolyte additive enabled interphase engineering, the SEI derived from in situ electrochemical transformation of the pre-coating layer offers a better manipulability, enabling precise regulation of both its structure and thickness while concurrently exhibiting good stability and mechanical flexibility. Moreover, its enhanced environmental adaptability ensures broad electrolyte compatibility, substantially extending the applicability of this strategy across a wide range of battery systems. Ex situ atomic force microscopy (AFM) research also indicates the significantly enhanced modulus but reduced adhesion of the interphase, owing to the decomposition of high-adhesion organic component and formation of high-modulus inorganic nanocrystalline. Then, a unique tandem regulation mechanism of such electrochemically driven hybrid interphase deeply was revealed by multi-scale characterization technique and density functional theory (DFT) calculation. Compared to pure Zn negative electrode, in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) and in situ pH tests show a stable interface pH with H2-free production in the SEI Zn case. Benefited from the strong anion capture capability of Zn3(PO4)2 phase and hydrophobic characteristic of hybrid interphase, a decreased de-solvation energy barrier and an enhanced Zn2+ transfer number can be realized. Finally, in-situ optical observation, ex situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) and in situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests confirm a uniform Zn (002)-preferred deposition and efficient transport kinetics during reversible Zn deposition/stripping process. This unique SEI enables a tandem regulation of interfacial side reactions, Zn2+ de-solvation, interfacial transport kinetics, and preferential Zn(002) deposition, thereby significantly enhancing the stability of the Zn negative electrodes. As demonstrated, the cycle lifespan of both Zn | |Zn cells and Zn | |MnO2 batteries can be extended when adopted such electrochemically driven interphase-modified Zn metal electrodes. The assembly of a 1.25 Ah Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O pouch cell further confirms its potential in the scale application. Beyond that, solid-state Zn metal batteries were assembled to evaluate the electrochemical performance in harsh environments, including the low-temperature, high-temperature, arbitrary bending, and high-pressure states. And its multi-scenario applications were also verified in the aqueous Zn | |I2 pouch cell and Zn-air batteries.

Results

Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the preparation process of SEI Zn, the optimized conditions of the preparation process were shown in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4. where an organic layer is coated on the surface through a simple doctor blade method. The prepared SEI Zn sample was subjected to bending in order to evaluate the adhesion strength of the coating deposited on the Zn foil surface. Supplementary Fig. 5 presents an optical micrograph depicting the outcome of this test. The field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) image revealed no alteration in the SEI Zn surface coating within the bent region, indicating that the surface coating exhibited well adhesion (Fig. 1a, b). Next, the morphology and structural composition of the SEI Zn surface were characterized. The SEI Zn surface morphology is shown in Fig. 1c, and the side view shows that the coating thickness is approximately 5.8 μm. It can be observed from the EDS patterns corresponding to the FESEM of the cross section (Fig. 1d) that C, P, and O elements are evenly distributed on the SEI Zn surface, which indicates that the coating is smooth and evenly dispersed. Meanwhile, to ascertain the water solubility of the material, we conducted a solubility experiment (Supplementary Fig. 6). The results demonstrated that MAHEPE was insoluble in water, the compound showed good stability when dispersed in aqueous solution. Following this, the hydrophobicity of SEI Zn was further investigated, Fig. 1e shows the contact angle test performed in 3 M ZnSO4 electrolyte. The contact angle of SEI Zn was measured at 90.4°, significantly higher than the 81.7° observed for pure Zn, indicating that SEI Zn exhibits a better hydrophobicity. The contact angle of the electrolyte on the SEI Zn surface is larger than that on the bare Zn surface, demonstrating the improved hydrophobicity of the SEI Zn surface28. To determine the chemical composition and molecular structure information of the modified anode surface modification layer, the prepared SEI Zn was subjected to fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis, and the results are shown in Fig. 1f. Among these, the absorption peaks at 3258 cm−1 and 2962 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibration of the asymmetric C − H group and the stretching vibration of O-H in the coating layer, respectively. The absorption peaks at 1719 cm−1, 1638 cm−1 and 1030 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of COOR, C = C and C-OH groups. Additionally, peaks at 1165 cm−1 and 563 cm−1 correspond to P = O and O-P-O bonds in the modified layer, respectively. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) further analyzed the chemical composition and surface element state of the modified layer (Fig. 1g, h and Supplementary Fig. 7). Firstly, for P 2p, the peaks at 133.73 and 134.48 eV may be related to P-O bonds. Then, for C 1 s, the peaks at 284.8, 286.65 and 288.5 eV correspond to C-C/C = C, C-OH and COOR respectively. Additionally, the analysis of O 1 s revealed peaks at 531.28 eV and 532.78 eV, corresponding to C-O and C = O bonds, respectively. These results confirm the successful deposition of the coating on the Zn surface.

a FESEM image of SEI Zn at the bending state and b corresponding enlarged FESEM images. c Side-view FESEM image of SEI Zn and d corresponding EDS mapping. e Contact angle test on the surface of pure Zn and SEI Zn by using 3 M ZnSO4 aqueous electrolyte. f FTIR spectrum and g P 2p and h C 1 s XPS spectra of SEI Zn.

As a crucial element for ensuring uniform Zn deposition and high electrochemical stability, the phase and structural evolution of the artificial interphase during cycling were thoroughly analyzed. As shown in Fig. 2a–c, compared to the precycled Zn foil, the surface morphology of the SEI Zn anode observed via FESEM after the 1st and 3rd cycles still exhibits a uniform coating, but with densely distributed dots formed from the electrochemical decomposition of organic components on its surface (Supplementary Figs. 8, 9). However, it remains uncertain whether there have been any compositional changes on the surface of the SEI Zn electrode after cycling. Hence, an analysis of the surface material was performed, and the phase of the thin layer scraped off the surface of SEI Zn after the 3rd cycle was characterized by high resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, Fig. 2d–f). The lattice fringes of 0.221 and 0.263 nm in Fig. 2f can be well assigned to the crystal planes of Zn3(PO4)2. Moreover, it also reveals the presence of the amorphous regions, which could be attributed to the organic layer on the surface of the SEI Zn. To further explore the phase evolution of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) on the Zn surface after cycling, the XRD, XPS and FTIR characterization were performed (Supplementary Figs. 10–12). The findings reveal that the immersion of SEI Zn in a 3 M ZnSO4 solution did not induce the formation of any novel phases on its surface. Conversely, characteristic diffraction peaks of the Zn3(PO4)2 phase were detected at 31.96°, 33.11°, and 34.68° on the surface of SEI Zn after cycling. These peaks correspond to the (02), (06), and (106) crystal planes (PDF#97-006-8362). This phenomenon suggests that, under the electrochemical driving force, Zn2+ migrates through the SEI and engage in a reaction with PO43−, thereby catalyzing the formation of insoluble Zn3(PO4)2. Note that, the peaks were skewed to the left due to the smaller grain size and larger lattice constant. In the XPS spectrum, for the P 2p region, peaks at 133.58 eV and 134.43 eV associated with P-O bonds were clearly visible. In the infrared spectrum, the wavenumbers at 1161.15 cm−1 confirm the existence of P = O bond, which were representative peaks of Zn3(PO4)2. Based on the above experimental results indicate that the surface of the SEI Zn anode spontaneously evolves into an organic-inorganic hybrid layer after cycling.

FESEM images of the SEI Zn (a) before cycle, (b) after 1 cycle and c after 3 cycles, respectively. d, e TEM images and f corresponding HRTEM image of the interphase after 3 cycles. g TOF-SIMS 3D reconstruction of the cycled SEI Zn surface (Negative ion mode was selected. Note that the scales of the x-axis and y-axis are different from those of the z-axis direction. The former represents the raster size and the latter means the sputter depth. Among them, the raster size is 50 × 50 μm, the sputter rate is 0.84 nm s−1 on GaN with a sputter time of 1500 s). h TOF-SIMS depth profiles on the cycled SEI Zn surface. i–k Corresponding 2D element distribution map of TOF-SIMS. Note that MC represents the maximum counts, and TC means the total intensity of secondary ions.

The evolutionary process of interphase can be further confirmed by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS). Figure 2g depicts the 3D elemental distributions of PO43−, C, and O. It is evident that the PO43− signal is relatively uniformly distributed across the entire plane, indicating the spontaneous construction of the artificial SEI into inorganic Zn3(PO4)2. TOF-SIMS analysis was performed in positive ion mode to carefully analyze the three-dimensional distribution of Zn, Zn-O, Zn-POx, and Zn-PO bonds before and after the 3-cycle process, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 13, 14. The comparative analysis shows that the signal strength of Zn-O bonds is basically unchanged before and after the cycle. The results show that Zn preferentially binds oxygen atoms on organic components at SEI Zn. Notably, at the initial state, the Zn-POx and Zn-PO components mainly originate from the intimate contact between the Zn anode and the PO43− groups in the SEI. After cycling, the signal strength of both Zn-POx and Zn-PO bonds increased after cycling. This enhancement is attributed to electrochemically derived Zn3(PO4)2 during cycling, resulting in the conversion of the organic coating to the organic/inorganic hybrid phase. Meanwhile, the signals of C and O elements also exhibit relatively uniform distribution across the entire plane, combined with the XPS data results (Supplementary Fig. 15), O 1 s analysis showed that at 531.33 eV and 532.78 eV, corresponding to the C-O and C = O bonds, respectively. Peaks at 284.8, 286.53, and 288.83 eV in the C 1 s correspond to C-C/C = C, C-OH, and COOR, respectively, which can be attributed to organic components within the SEI. In addition, the elemental intensity distribution maps corresponding to different etching times are shown in Fig. 2h, which substantiates the presence of a defined thickness in the SEI. Meanwhile, the 2D planar distribution maps obtained from TOF-SIMS reveal that the distribution profiles of the three components are congruent across the plane, further confirming that the SEI composition is a composite of organic and inorganic phases (Fig. 2i–k). As a result, the above comprehensive characterization results confirm that the artificial SEI self-evolved into an organic-inorganic hybrid layer after cycling.

Young’s modulus is an important mechanical parameter of the solid electrolyte interphase. Solid electrolyte interphase with low mechanical strength cannot control the uniformity of Zn deposition and withstand significant volume expansion caused by Zn stripping, while solid electrolyte interphase with robust mechanical strength can effectively inhibit the growth of Zn dendrites. The average Young’s modulus (AYM) on the surface of SEI Zn and pure Zn anode was studied. As shown in Fig. 3a–d and Supplementary Fig. 16, the initial AYM value of SEI Zn (0.02 GPa) is much lower than that of pure Zn anode (1.42 GPa). This can be attributed to the inherent flexibility of the organic coating on the surface of SEI Zn. After the first cycle, the AYM of SEI Zn anode rises to 4.05 GPa, which remains lower than that of pure Zn electrode (4.33 GPa). After the 3rd and 5th cycle, the AYM of SEI Zn electrode slightly increases (4.96 GPa and 6.66 GPa, respectively). In contrast, the AYM value of the pure Zn anode demonstrates a more pronounced elevation. (the 6.65 Gpa after 3rd cycle and 8.02 Gpa after 5th cycle). The elevation in the AYM value of SEI Zn during cycling may be due to the progressive transformation of the flexible organic coating into an organic-inorganic hybrid interphase, thereby increasing rigidity. Meanwhile, the increase in the AYM of the pure Zn anode is primarily attributed to the gradual formation of Zn dendrites with high Young’s modulus (Supplementary Fig. 17). The corresponding adhesion distribution diagram SEI Zn can be seen in Fig. 3e, f. The initial average adhesion force was 726.32 nN and only 148.41 nN after the first cycle. Subsequently, after three and five cycles, the average adhesion force of SEI Zn electrode continuously decreases (65.49 nN after 3rd cycle and 51.56 nN after 5th cycle). This further confirms that the highly viscous organic coating layer continuously decomposes with increasing cycle numbers, forming a robust inorganic phase.

Young’s modulus mechanical map of (a) pure Zn, and b SEI Zn anode. Quantitative analysis using histograms of Young’s modulus values in log-normal scale with a Gaussian distribution fit (c) pure Zn electrode, and d SEI Zn electrode. e Adhesion map of SEI Zn electrode. f Column chart of adhesion for SEI Zn electrode with different number of cycles. g Comparison of roughness between pure Zn and SEI Zn anode with different number of cycles.

In order to further verify whether the decomposition behavior of organic coatings during electrochemical cycling is non-terminating, detailed surface composition analysis of SEI Zn after different cycles was performed. In the Supplementary Fig. 18 of SEI Zn after 5 cycles, the presence of the interphase can be clearly observed. This observation not only confirms the decomposition of the organic coating during the cycle, but also reveals significant changes in coating thickness. Specifically, the coating thickness after 5 cycles was significantly reduced compared to that before the cycle. This change in thickness is directly attributable to the decomposition of the organic coating. Further, by EDS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 19), C, O and P elements were evenly distributed in the decomposed coating. At the same time, the characteristic peaks of organic coatings were also detected in the XPS P 2p and O 1 s spectra (Supplementary Fig. 20). The presence of these characteristic peaks indicates that even after 5 cycles, the flexible organic coating does not completely disappear, but gradually transforms into an organic-inorganic hybrid interphase. When the number of cycles is further increased to 20 and 50 cycles, it can be observed from the Supplementary Figs. 21, 22 that the organic coating is still clearly visible and tightly bonded to the Zn anode, even at the bending state or electrolyte soaking treatment. This indicates that although the adhesion of SEI is weakened after organic coating decomposition, it can still maintain a good binding to the Zn anode without obvious delamination. In addition, the distribution of C, O and P elements in the EDS spectrum remained relatively uniform, while the characteristic peaks in the XPS spectrum and FTIR spectrum were also obvious (Supplementary Figs. 23–25). More importantly, the morphological evolution (Supplementary Fig. 26) confirms that the observed dots resulted from the electrochemical decomposition of organic components did not significantly change even after 100 cycles, indicating the stable structure and non-electrochemical activity. Based on the above experimental results, it can be concluded that the decomposition of organic coatings in the electrochemical cycle is limited and non-electrochemical activity and eventually tends to form a stable organic-inorganic hybrid interphase.

During cycling, in addition to the evolution of the interphase structure, surface roughness was also investigated. Analysis of the corresponding AFM morphology images of SEI Zn and pure Zn electrodes at various cycle numbers (Supplementary Figs. 27–28) provided insights into their respective roughness profiles (Fig. 3g). The average surface roughness of the pure Zn electrode exhibited a continuous increase with cycle number, starting at 50.4 nm in the first cycle, reaching 419 nm in the third cycle, and peaking at 519 nm in the fifth cycle. In contrast, the roughness of the SEI Zn anode remained consistently below 100 nm across all cycle numbers. This consistency can be attributed to the uniform Zn2+ flux maintained within the interphase layer of the SEI Zn electrode, facilitating uniform Zn2+ deposition, while the surface of the pure Zn anode experienced disordered Zn2+ deposition.

According to the experimental results, the flexible organic coating experienced a gradual transformation process and gradually evolved into an organic-inorganic hybrid interphase. The hybrid interfacial phase has high mechanical strength and can effectively inhibit the growth of Zn dendrites. In addition, it maintains a uniform Zn2+ flux within the interphase layer of the SEI Zn electrode and promotes the uniform deposition of Zn2+. It is worth noting that the electrode material retained its hydrophobic properties after the cyclic test (Supplementary Fig. 29). To a certain extent, the retention of this hydrophobic property provides potential insight into how SEI electrode materials inhibit HER and enhance corrosion resistance.

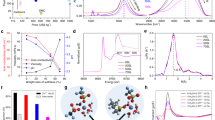

Typically, the direct contact between water molecules and Zn leads to competitive hydrogen evolution, significantly affecting the stability of the Zn negative electrode. To investigate the interfacial stability of SEI Zn, anti-HER ability was initially studied. In situ DEMS was used to monitor hydrogen release during battery cycling (Fig. 4a, b). For pure Zn, a strong H2 response can be detected when cycling at a current density of 1.5 mA cm−2, while no obvious H2 signal can be seen during the entire cycle of the SEI Zn electrode, indicating that the HER is inhibited29. Simultaneously, in situ pH monitoring was utilized to assess the impact of SEI on the suppression of HER. A Zn | |Zn cell assembled in a glass electrolyte cell was cycled under conditions of 20 mA cm−2 and 5 mAh cm−2, while the pH values of the electrolyte were continuously recorded. As illustrated in Fig. 4c, d, after 40 cycles, the pH of the electrolyte in the symmetric cell with pure Zn increased significantly from 3.1 to 3.9, indicating that the vigorous HER occurring on the Zn anode surface consumed a substantial amount of H+, leading to a surplus of OH−. In contrast, SEI Zn substantially delayed the pH increase, ultimately stabilizing it at approximately 3.4. The stabilizing effect of the artificial SEI on the electrolyte pH during battery cycling demonstrates a reduction in water molecule electrolysis and a significant inhibition of HER. In addition, the HER curve shows that the hydrogen evolution current of the SEI Zn electrode at -1.7 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) is 2.10 mA, which is much lower than the 3.98 mA of the pure Zn electrode (Supplementary Fig. 30). Besides, such inhibitory effect can be maintained after cycling, demonstrating a good anti-HER performance of the modified electrode (Supplementary Fig. 31).

In-situ DEMS test of the (a) SEI Zn and b pure Zn electrodes at the condition of 1 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2. Note that CD stands for current density. In-situ pH test of the (c) SEI Zn and d pure Zn electrodes at the condition of 1 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2. e Adsorption energy of Zn2+ and SO42− on the Zn3(PO4)2 surface. 3D charge difference between Zn3(PO4)2 and f Zn atom and (g) SO42−. h Zn2+ migration number of the pure Zn and SEI Zn. i Calculation and fitting of Ea based on impedance at different temperatures. DRT analysis of the symmetric (j) SEI Zn and k pure Zn by operando EIS evolution.

The corrosion resistance of SEI Zn in a weakly acidic environment was studied. The digital photos of the SEI Zn electrode and pure Zn electrode, soaked in 3 M ZnSO4 for three days at room temperature, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 32. According to the FESEM images, the SEI Zn surface is smooth and flat, and the corresponding EDS image shows that the coating remains firmly attached to the Zn foil surface, with almost no detectable S element signal (Supplementary Fig. 33). In contrast, the surface of the pure Zn is covered with a large number of hexagonal basic flakes enriched with S elements (Supplementary Fig. 34). Under high temperature conditions, the corrosion rate in weak acid aqueous electrolyte will increase. To further investigate the inhibitory effect of artificial SEI on corrosion at high temperatures, The SEI Zn and pure Zn electrode were soaked in 3 M ZnSO4 and then placed in an oven at 60 °C for 3 days. Observation of the digital photographs (Supplementary Fig. 32) and SEM images of the soaked SEI Zn reveals that the artificial SEI can effectively maintain the morphology of the Zn anode even at high temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 35). However, the pure Zn anode exhibits more severe corrosion, with surface by-products evolving into larger, thicker, and more densely packed hexagonal shapes. The corresponding EDS image also detected a significant amount of S element signal (Supplementary Fig. 36). Subsequently, XRD confirmed that the flake-like by-product observed on the surface of pure Zn after soaking at both room temperature and high temperature is Zn4SO4(OH)6·5H2O. Consistent with the FESEM results, almost no peaks of by-products were observed on the surface of SEI Zn (Supplementary Fig. 37). In addition, the Tafel curve shows that the corrosion potential of the SEI Zn electrode is -0.90 V, which is much higher than -0.95 V of pure Zn, and the SEI reduces the corrosion current from 3.24 to 2.57 mA cm−2, indicates lower corrosion rate (Supplementary Fig. 38). The ability of SEI Zn electrode to resist weak acidic electrolyte corrosion and inhibit HER is attributed to its surface-coated organic layer, which isolates free water molecules in the electrolyte and prevents direct contact with the Zn metal surface.

Then, DFT calculations were carried out to investigate the impact of the artificial SEI on the transport of electrolyte ions at the interphase. As shown in Fig. 4e, Supplementary Data 1–6, and Supplementary Figs. 39, 40, The adsorption energy and the corresponding adsorption model are shown, the three adsorption sites of SO42− in the crystal structure of Zn3(PO4)2 are mainly determined based on the high chemical affinity between Zn atom and O atom in SO42−. The result shows that the adsorption energy of SO42− at the three sites of Zn3(PO4)2 is much larger than that of Zn²⁺, indicating that the artificially Zn3(PO4)2 enriched hybrid SEI interphase can adsorb SO42− from the electrolyte, the barrier to the migration of cations such as Zn2+ is weakened, thereby accelerating the transport of Zn2+. In addition, by comparing the charge density of SO42− and Zn2+ adsorbed on Zn3(PO4)2 (Fig. 4f, g), the difference in interaction strength can be further elucidated. The electron cloud volumes of SO42− at three different sites on the Zn3(PO4)2 atomic layer are all larger than those of Zn2+ at the two sites on the Zn3(PO4)2 atomic layer. This indicates that more electrons from SO42− are accumulated on the SEI layer, leading to more stable adsorption. This strategy of restricting anions to enhance cation transport kinetics is commonly used to improve the ion transference number in solid-state electrolytes. As expected, the artificial hybrid interphase significantly increases the Zn2+ transference number (tZn2+) from 0.13 to 0.41, which further confirms the contribution of the interphase layer of SEI Zn electrode to Zn2+ migration ability (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 41 and Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, the uniformly distributed Zn3(PO4)2 nanocrystals facilitate a synchronized enhancement of the overall ionic migration rate within the SEI, further optimizing the uniformity of the Zn2+ flux.

Based on enhanced ion transport kinetics, it is inferred that the de-solvation energy of hydrated Zn2+ can be significantly reduced by the artificial SEI. To substantiate this, the activation energy (Ea) was derived using the Arrhenius equation to evaluate the influence of the artificial interphase on the de-solvation process of hydrated Zn2+ 30. As illustrated in Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 42 and Supplementary Table 2, the Ea for SEI Zn is markedly reduced to 27.4 kJ mol-1, compared to 36.3 kJ mol-1 for the pure Zn electrode. This significant reduction corroborates the accelerated Zn2+ desolvation kinetics, which is primarily attributed to the exclusion of solvent water by the organic constituents within the SEI. To gain further insights into the reaction kinetics taking place on the surface of Zn anodes, a comprehensive analysis of the in situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and the corresponding relaxation time distribution (DRT) during Zn deposition/stripping processes was conducted (refer to Supplementary Fig. 43 and Fig. 4j, k). The observation of multiple peaks at generally similar positions in both Pure Zn and SEI Zn assembled symmetric cells indicates a comparable electrochemical Zn deposition process occurring on the surfaces of these two types of Zn electrodes. The peaks at a time constant of ≈0.05 s (τ1), 2.2 s (τ2), and 80 s (τ3) stand for the adsorption and de-solvation of Zn2+ ions, the charge transfer of Zn2+ and Zn2+ interfacial diffusion, respectively. Despite of the similar relaxation times of diverse process at the initial stage, significant differences in τ values appeared between SEI and pure Zn in the later Zn plating/stripping process. After cycling 5th, the τ values of SEI Zn electrode grown smaller, while those of pure Zn fluctuated. This can be explained by the presence of the SEI layer which facilitates the de-solvation of Zn2+, consequently reducing the contribution of τ1 to the overall impedance. Additionally, the significantly shortened τ2 highlights its inherently faster kinetics.

Under the enhancement of the artificial hybrid interphase, the initial nucleation of Zn on the anode surface and subsequent Zn deposition are likely to be optimized. Consequently, electrochemical and morphological analyses were employed to verify this. First, electrochemical methods were used to compare the differences in the initial nucleation mechanisms between SEI Zn and pure Zn. Firstly, the Zn2+ diffusion mode of the interphase can be determined by analyzing the chronoamperometric (CA) curve. As shown in Fig. 5a, Zn2+ will undergo a long and intense two-dimensional diffusion process on the surface of pure Zn anode, and Zn2+ is preferentially transferred to the bulge with high electric field density, resulting in the formation of dendrites. However, on the surface of SEI Zn, the 2D diffusion of Zn2+ is inhibited, while a continuous 3D diffusion occurs. This may be due to the high-adhesion artificial coating restricting the diffusion of Zn2+ on the surface of Zn negative electrode. Furthermore, the magnitude of the nucleation barrier also has a significant impact on Zn nucleation. Usually, the value of nucleation overpotential (NOP) reflects the energy barrier during the initial deposition process. As expected, the pure Zn electrode showed high NOP of 70.4, 339.0 and 497.0 mV at current densities of 1, 2 and 10 mA cm−2, respectively. In comparison, SEI Zn exhibits a lower NOP, with values of 22.8, 114.0, and 185.0 mV at current densities of 1, 2, and 10 mA cm−2, respectively (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 44). This is possibly due to the homogeneously distributed phosphate groups in the SEI reducing the Zn nucleation energy barrier. Additionally, the Zn nucleation overpotential obtained from the CV test of the Zn | |Cu cell confirms this conclusion (Fig. 5c).

a The CA curves of pure Zn and SEI Zn electrodes. b Nucleation overpotential of Pure Zn and SEI Zn electrodes at 10 mA cm−2. c CV curves of SEI Zn | | SEI Cu and Pure Zn | | Pure Cu asymmetric cells. In situ optical observation of the (d) SEI Zn and e pure Zn electrode during the Zn deposition process at the current density of 20 mA cm−2. Ex situ 2D XRD analysis of the (f) SEI Zn and g Pure Zn electrode after different cycles. h The crystal structure of metallic Zn and i corresponding ratio change of I(002)/I(101).

Secondly, the initial nucleation and subsequent deposition of Zn were also observed using in situ optical microscopy. As shown in Fig. 5d, e, at a plating current density of 10 mA cm−2, the surface of SEI Zn maintained uniform deposition from the initial deposition up to 30 min, with the deposition layer uniformly thickening over time. In contrast, on the pure Zn surface, the initial deposition of Zn2+ was uneven and gradually evolved into dendrites at the original nucleation sites. In order to further clarify the deposition behavior of Zn2+ on the SEI Zn electrode, the side morphology of SEI Zn was analyzed after the deposition for 10 and 20 min (Supplementary Fig. 45). The results of FESEM and corresponding EDS mapping indicate that SEI Zn electrode has a three-layer structure after deposition, and the deposited Zn are beneath the SEI layer. Such phenomenon attributed to the non-conductive nature of the artificial SEI layer. FESEM images show that the SEI layer remains intact after deposition. The retention of this form effectively protects the Zn anode from harmful interactions and promotes uniform deposition of Zn2+. This lays the foundation for the construction of a stable electrode/electrolyte interphase, which is critical for improving the performance and durability of Zn-based electrochemical devices.

Thirdly, ex situ characterization techniques were employed to perform postmortem analysis of the cycled Zn negative electrodes. FESEM images reveal significant differences on the surfaces of SEI Zn and pure Zn electrodes after the 10th cycle, demonstrating that the artificial interphase significantly enhances the reversibility of the Zn electrode (Supplementary Figs. 46, 47). Simultaneously, XRD pattern of the pure Zn electrode shows that the Zn (002) peak of SEI Zn increases with the number of cycles after the 10th and 100th cycles (Supplementary Fig. 48). During Zn deposition, the relatively weak binding interaction between Zn3(PO4)2 in the SEI Zn electrode and Zn2+ results in a low migration energy barrier for Zn2+ within the ionic channels of Zn3(PO4)2. Meanwhile, SO42− are effectively anchored by Zn3(PO4)2, enabling selective transport of Zn2+ and thereby reducing concentration polarization. The synergistic effect of these mechanisms, combined with the high 2D diffusion energy barriers of organic components, homogenizes the Zn2+ flux and optimizes Zn nucleation. As a result, the Zn (002) plane of the SEI Zn electrode becomes the preferred orientation for Zn deposition. Consequently, the relative intensity of the Zn (002) peak in SEI Zn is enhanced throughout the cycling process. Notably, the pure Zn anode preserved the primary Zn (101) crystalline plane of the original Zn foil during cycling, while a significant by-product characteristic peak also emerged. To demonstrate this more intuitively, the SEI Zn electrodes after 1, 10 and 50 cycles were tested by 2D XRD, which is more suitable for observing the distribution of different orientation crystal planes. The results suggest that the brightness of the Zn (002) crystal plane diffraction spots strengthens with an increase in the number of cycles. (Fig. 5f). However, the diffraction spots of the pure Zn electrode exhibit no discernible pattern of change throughout the cycling process, indicating uncontrollable plating/stripping behavior on the surface (Fig. 5g). It is well known that among the different crystal planes of metallic Zn, the Zn (002) plane is distinguished by its horizontal arrangement. This orientation encourages parallel Zn growth, which results in less volumetric stress and greater stability in mildly acidic aqueous electrolytes. On the other hand, the Zn (101) plane forms a larger angle with the horizontal plane, causing Zn to grow vertically on this plane (Fig. 5h). This leads to increased volumetric stress and reduced stability31. Finally, the corresponding crystal plane ratio of I(002)/I(101) is shown in Fig. 5i. The above discussion strongly proves that the SEI Zn electrode can effectively regulate the deposition behavior of Zn2+, so as to achieve the effect of inhibiting dendrite growth.

Drawing on the experimental and theoretical calculation results, Fig. 6 elucidates the sophisticated mechanism of the highly dispersed nanocrystal hybrid SEI, formed through in-situ phase transformation (Note that this figure was designed by using Cinema 4D Version: 2023.2.0 with copyright license). This SEI exhibits a range of advanced functionalities, including effective water molecule exclusion, acceleration of Zn2+ de-solvation, precise modulation of interfacial electric fields and Zn2+ flux, alongside the regulation of stress distribution at the interphase. During cycling, the organic interphase undergoes electrochemical conversion into a hybrid phase enriched with finely dispersed Zn3(PO4)2 nanocrystals, which facilitate Zn2+ transport by selectively capturing SO42−. The uniform distribution of these nanocrystals ensures homogeneous ion transport throughout the SEI, thereby stabilizing the interfacial electric field and promoting uniform Zn deposition. Additionally, the hybrid SEI, with its robust mechanical properties marked by high robustness, strong adhesion, and a high modulus effectively mitigates interfacial stress accumulation, thereby significantly inhibiting the formation of Zn dendrites. The hydrophobicity imparted by the organic components further suppresses water induced electrolyte decomposition and Zn corrosion. Collectively, these synergistic effects pave the way for the development of Zn negative electrode with well thermodynamic stability and highly reversible Zn plating/stripping characteristics, offering transformative potential for next-generation energy storage systems.

Through symmetric cell tests, SEI Zn demonstrated good performance as a metallic anode for aqueous Zn-ion batteries, and extending its application to a wide temperature range. First of all, the long-term cycle performance of SEI Zn at 0°C is tested. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 49, the SEI Zn symmetric cells were able to cycle for 1500 h under the condition of 1 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2, while the pure Zn symmetric cells failed after only 170 h of cycling. When the current density and area capacity were increased to 5 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 (Fig. 7a), the cyclic stability of SEI Zn symmetric cells remained much better (900 h) than that of pure Zn case (80 h). In addition, the rate performance was also tested (Supplementary Fig. 50). Both the pure Zn and SEI Zn electrodes performed well at 0°C. The difference was that Zn2+ transport was inhibited at low temperature without the high \(t{{{{\rm{z}}}}}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}^{2+}\) artificial interphase, which made the pure Zn electrode exhibit a high polarization voltage at different current densities. Then, the cyclic stability at room temperature was tested. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 51, SEI Zn obtained cyclic stability over 3000 h at 1 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2. In contrast, the pure Zn only cycled for 64 h. At high current density, SEI Zn symmetric cells still had good stability, stable cycling for more than 1500 h at 10 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2 (Fig. 7b), while the long-term cycle performance of pure Zn ones remained unsatisfactory (cycle 310 h). Under more extreme testing conditions (20 mA cm−2, 4 mAh cm−2), SEI Zn still cycle for more than 270 h, whereas pure Zn could only cycle for 54 h (Supplementary Fig. 52). In addition, the rate performance at room temperature was also tested. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 53, SEI Zn symmetric cases demonstrated good adaptability when switching between different current densities, whereas pure Zn one experienced a sharp increase in polarization when the current density returned from 5 to 2 mA cm−2. This may be attributed to uncontrolled Zn deposition and side reactions leading to the formation of dendrites and dead Zn, as well as interphase passivation. Finally, the cycle performance at high temperature of 60 °C was tested. At high temperatures, battery side reactions and HER will intensify, impacting the cycle stability of symmetrical cells. Under the conditions 5 mA cm−2 and 1 mAh cm−2, the SEI Zn electrode can cycle stably for over 380 h, whereas the cycling time for pure Zn did not exceed 20 h (Fig. 7c). Meanwhile, pure Zn exhibits poor rate performance at high temperatures, whereas SEI Zn demonstrates enhanced rate performance and lower polarization voltage under high-temperature conditions, indicating that the SEI Zn electrode still maintains advantages at elevated temperatures. (Supplementary Fig. 54).

Long-term cycle performance of pure Zn and SEI Zn negative electrodes in coin-type cells at the conditions of (a) 5 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 and 0°C; (b) 10 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 and 25°C; and c 5 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 and 60°C. d Cycle performance of the coin-type Zn | |MnO2 batteries at 1 A g−1. Rate performance of of the coin-type Zn | |MnO2 batteries at (e) various current densities, and f various temperature environments. g Cycle performance test of SEI Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O pouch cell and its (h) corresponding GCD curve.

To verify the effectiveness of SEI Zn electrode in practical applications, Zn | |MnO2 full batteries were assembled with SEI Zn and pure Zn as negative electrodes, MnO2 as the positive electrode, and 3 M ZnSO4/0.2 M MnSO4 as the electrolyte. Firstly, long-term cycling tests were conducted at 0 °C and 0.5 A g−1 (Supplementary Fig. 55). The discharge specific capacity of the pure Zn | |MnO2 full battery declined to 93.8 mAh g−1 after the initial 50 cycles, while the SEI Zn | |MnO2 full battery still maintained a high discharge specific capacity of 118 mAh g−1 after 240 cycles, demonstrating the well stability of SEI Zn assembled full batteries at low temperatures. Subsequently, long-term cycling and rate performance of the full batteries were evaluated at room temperature. At a current density of 0.2 A g−1, the SEI Zn | |MnO2 full batteries could maintain a stable specific capacity for over 150 cycles, while the capacity of pure Zn | |MnO2 full batteries continues to decline (Supplementary Fig. 56). Even at higher current density (1 A g−1, after activation at 0.2 A g−1 for 10 cycles), the performance of SEI Zn based full batteries showed significant enhancement (Fig. 7d). After 700 cycles, the SEI Zn | |MnO2 battery retained a discharge specific capacity of 228.6 mAh g−1 and a capacity retention rate of 96.1%, which is better than pure Zn | |MnO2 batteries (114 mAh g−1 and 49.6%, respectively). The cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the SEI Zn | |MnO2 system exhibit the same redox reaction behavior as those of batteries using pure Zn electrodes, as shown in supplementary Fig. 57. In addition, ex situ XRD analysis also proves that the crystal structure of MnO2 positive electrode is similar in both pure Zn and SEI Zn systems after cycling (Supplementary Fig. 58). Therefore, CV and XRD results show that the similar reaction mechanism in these two negative electrode systems, suggesting the SEI do not induce side reactions yet improve the long-term battery stability by stabilizing the Zn|electrolyte interphase. Additionally, the SEI Zn | |MnO2 battery exhibited good rate capability, achieving discharge capacities of 282.1, 276.0, 257.8, 234.4, and 211.1 mAh g−1 at current densities of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 A g−1, respectively, significantly outperforming the Zn | |MnO2 battery. (Fig. 7e). When the current density returns to low current density, the specific capacity of the SEI Zn | |MnO2 battery remains nearly unchanged, highlighting its robust rate recovery capability and suitability for complex and changeable scenarios in practical applications. Simultaneously, to eliminate the potential interference of MnSO4 in the electrolyte on the performance of the SEI Zn, we assembled a Zn | |MnO2 battery utilizing SEI Zn and pure Zn as the negative electrodes, MnO2 as the positive electrode, and 3 M ZnSO4 as the sole electrolyte. At a current density of 1 A g−1 (following an initial activation phase of 10 cycles at 0.2 A g−1), the stability of the full battery equipped with the SEI Zn anode was observed to be enhanced, as evidenced in Supplementary Fig. 59. After undergoing 1200 cycles, the SEI Zn | |MnO2 system exhibited a discharge specific capacity of 142.87 mAh g−1, surpassing the performance of the pure Zn | |MnO2 one, which delivered 108.30 mAh g−1 after 500 cycles.

Based on the above-mentioned work, the electrochemical performance at variable temperatures were carried out (Fig. 7f). At different temperatures of 0, 20, 30, and 40 °C, both SEI Zn | |MnO2 and Zn | |MnO2 batteries can operate normally. However, benefiting from the enhanced interphase stability and transport kinetics of the SEI Zn negative electrode, the SEI Zn | |MnO2 battery exhibits greater reversibility. After undergoing the variable temperature cycle, the batteries were disassembled, and the Zn electrodes were retained for analysis using XRD to observe the surface composition post-cycling. As a result, XRD confirmed the presence of the by-product Zn4SO4(OH)6·5H2O on the surface of the cycled pure Zn electrode (Supplementary Fig. 60). In contrast, XRD patterns showed no peaks for by-products. This confirms the interfacial stability of the SEI Zn negative electrode in various environments and its good adaptability in full batteries, reflecting the well environmental adaptability of SEI Zn | |MnO2 button cells. Given the good performance of the SEI Zn electrode in button batteries, it was further applied to flexible pouch cells. Multilayer SEI Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O flexible pouch cell was assembled using 3 M ZnSO4 as the electrolyte. As shown in Fig. 7g, under a current of 300 mA, the initial capacity reached 1.25 Ah. After 10 cycles, the capacity retention was 80% (Fig. 7h).

To further explore the application scenarios of the SEI Zn electrode, coin- and pouch-type quasi-solid state SEI Zn | |MnO2 cells were assembled, and their cycle performance under various extreme conditions was tested (Supplementary Fig. 61). Firstly, the practicality across a wide temperature range was verified in the coin-type cells. As shown in Fig. 8a, at 50 °C and 1 A g−1, the specific capacity was 165 mAh g−1, and after 2000 cycles, there was no decay (186 mAh g−1). While at -30 °C, the specific capacity can reach 135 mAh g−1, and it remains undiminished over 2500 cycles (Fig. 8b). Secondly, the cycle performance of the flexible pouch cells at low temperatures and various bending angles was tested. At -20 °C and a current density of 1 A g−1, it had a specific capacity of 150 mAh g−1. Under bending angles of 30°, 60°, 120°, and 180°, the capacity retention rates were 101%, 101%, 99%, and 99%, respectively, indicating that the battery performance was completely unaffected. This demonstrated the good flexibility of the flexible cells, even when the aqueous electrolyte’s fluidity decreased near the freezing point (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Fig. 62).

Cycle performance tests of the quasi-solid SEI Zn | |MnO2 button batteries at the working conditions of (a) 1 A g−1 at 50oC, and b 1 A g−1 at -30oC. Cycle performance tests of the quasi-solid SEI Zn | |MnO2 pouch cells at the working conditions of (c) 1 A g−1 at -20oC under different bending angles, and d 1 A g−1 at 25oC under 1 MPa pressure. e Cycle performance test of aqueous SEI Zn | |I2 pouch cell at the current density of 0.1 A g−1. f Cycle performance test of aqueous Zn-air batteries, in which 20 wt% Pt/carbon as the positive electrode, 6 M KOH/0.2 M Zn(CH3COO)2 as aqueous electrolyte, and SEI Zn and Pure Zn as negative electrodes.

Furthermore, to verify the applicability of the flexible SEI Zn | |MnO2 pouch cells under high-pressure conditions such as external force compression and deep-sea operations32, cycling tests were conducted under high pressure (1 MPa) (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 63). After 200 cycles, the capacity retention rate remained at 94%, proving the high-pressure resistance of the flexible SEI Zn | |MnO2 pouch cells. The robust flexibility of the flexible SEI Zn | |MnO2 pouch cells, combined with their stable electrochemical performance under high and low temperatures and high pressure, makes them promising and reliable candidates for aqueous Zn-ion batteries, including various wearable and implantable devices. Additionally, the compatibility of the SEI Zn negative electrode in different systems was explored. On the one hand, Zn | |I2 batteries were assembled (Supplementary Fig. 64), using activated carbon (AC) as the adsorption carrier and I2 (wt≈50%) as the positive electrode for energy storage through a conversion reaction mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 65). At 60 °C and 1 A g−1, the SEI Zn | |I2 battery had a specific capacity of 100.7 mAh g−1 after 600 cycles, higher than the 87.7 mAh g−1 of the pure Zn | |I2 battery (Supplementary Fig. 66). Meanwhile, the SEI Zn | |I2 pouch battery was assembled with an initial capacity of 132 mAh, and the capacity retention rate remained at 92.9% after 100 cycles, indicating good cycling stability of the SEI Zn electrode in Zn | |I2 pouch cells (Fig. 8e).

On the other hand, an alkaline Zn-air battery was assembled using platinum-carbon catalyst (20 wt% Pt supported) coated carbon paper as the positive electrode, 6 M KOH/0.2 M Zn(CH3COO)2 as the electrolyte, and SEI Zn and pure Zn as the negative electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 67). Figure 8f shows the charge-discharge curve at a current density of 5 mA cm−2. After a long cycle of 190 h, the discharge and charge potentials of the SEI Zn air battery were 1.08 and 2.04 V, respectively, while those of the pure Zn air battery were 0.86 and 2.6 V after a 98-hour cycle. The corresponding charge-discharge curve (Supplementary Fig. 68) showed that the polarization voltage of the SEI Zn air battery changed minimally from 100 to 500 cycles (0.803-0.939 V), whereas the polarization voltage of the pure Zn air battery changed significantly from 100 to 285 cycles (0.912–1.458 V). This is because the surface of pure Zn was severely passivated by the KOH electrolyte33, affecting the transport of Zn2+. To prove that, SEI Zn and pure Zn electrodes were immersed in 6 M KOH solution for 3 days, and their surface morphology and structural changes were observed. FESEM showed white granular substances on the surface of pure Zn, forming a new layer of material. EDS images showed more O elements distributed on the surface (Supplementary Fig. 69). The FESEM image of SEI Zn showed few cracks in the surface coating due to long-term immersion in the high-concentration alkaline solution, but no obvious damage to the coating structure. Although the EDS element distribution map also showed the uniform distribution of O elements, it was impossible to determine whether it was O in ZnO or O in the organic coating (Supplementary Fig. 70). The surface structure changes of pure Zn and SEI Zn after immersion were further confirmed by corresponding XRD (Supplementary Fig. 71). The emerging peak on the surface of pure Zn perfectly matched that of ZnO, while no new peak appeared on the surface of SEI Zn, indicating that the new material layer on the surface of pure Zn was uniformly distributed ZnO, whereas the O element in SEI Zn was from the organic coating.

Discussion

In this work, we developed and validated an electrochemically driven artificial solid-state interphase (ASSI) for Zn negative electrodes. A simple coating of 2-methyl-2-acrylate-2-hydroxyethyl ester phosphate ester (MAHEPE) was applied to form a protective solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) on the Zn surface. Then, the SEI undergoes an in-situ transformation into a robust hybrid phase enriched with highly dispersed Zn3(PO4)2 nanocrystals during cycling. Such hybrid SEI, with its hydrophobic and zincophilic properties, facilitates uniform Zn²⁺ interfacial ion flux, effectively suppressing dendrite growth and mitigating water-induced side reactions. As a result, the SEI Zn demonstrated stable cycling for over 1500 h at 10 mA cm−2, while the SEI Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O pouch cell delivered ampere-hour-level capacity. Additionally, the initial strong adhesion and flexibility of the SEI confer good mechanical resilience to the Zn negative electrodes under various operational conditions, including tolerance to wide temperature ranges, different bending angles, and sustained performance under applied external pressure, while the SEI Zn | |MnO2 batteries also demonstrate impressive performance under these conditions, and the proposed ASSI strategy was successfully extended to Zn | |I2 and Zn-air battery systems. This approach provides valuable insights into the development of highly reversible ZMBs and represents a promising strategy that could be applied to other metal-based battery systems.

Methods

Zn negative electrode materials and dimensions

Zn metal foils (purity: 99.95%, thickness: 0.1 mm) were purchased from Tianjin EVS Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Prior to cell assembly, the foils were sequentially polished using sandpapers with 400, 800, 1200, and 2000 mesh to remove surface contaminants, followed by thorough rinsing with anhydrous ethanol (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd.) and drying with lint-free tissue. For coin-type cells, Zn negative electrodes were punched into circular discs with a diameter of 14 mm. In Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H₂O and Zn-based pouch cells, Zn foils were cut into squares measuring 10*10 cm. For Zn | |I2@AC pouch cells, the Zn negative electrode dimensions were 4*6 cm, and for Zn | |MnO2 flexible batteries, the Zn negative electrodes measured 3*2 cm. In Zn–air batteries, the Zn negative electrode was cut into a rectangular sheet of 2.5*6 cm.

Preparation of SEI Zn negative electrode

Weighing 0.02 g of 2-methyl-2-acrylate-2-hydroxyethyl ester phosphate ester and dissolve it in 1 mL of absolute ethanol. Stir until completely dissolved and then apply it to the polished Zn foil surface (15*5 cm with a 200 μm scraper), and then immediately put it into a vacuum drying oven at 60 °C to dry for 2 h.

Preparation of MnO2, NaV3O8·1.5H2O, and I2@AC positive electrode materials

On the one hand, MnO2 and NaV3O8·1.5H2O were prepared according to the following steps34,35. For MnO2, 3 mmol MnSO4·H2O and 2 mL 0.5 mol L−1 H2SO4 were dissolved in 60 mL distilled water under magnetic stirring for 10 min, and then 20 mL 0.1 mol L−1 KMnO4 was slowly added into the above solution. The mixture was stirred for 1 h, followed by sonication for 1 h. Finally, the mixture was transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 120°C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, α-MnO2 was washed with distilled water and dried overnight at 60°C in a vacuum drying oven. While for NaV3O8·1.5H2O, 1 g of commercial V2O5 powder was added to 15 mL of NaCl aqueous solution (2 M). After stirring at 30 °C for 96 h, the suspension was washed several times with deionized water. Finally, it was freeze-dried to obtain a black-red product. On the other hand, I2@AC was synthesized through a facile method36. In detail, 1 g I2 and 1 g active carbon (AC) were mixed by grinding using an agate mortar in the air at 25 ± 1 °C for 3 min. Then, the mixed powder was sealed in a 10 mL hydrothermal polytetrafluoroethylene reactor and heated at 80 °C for 4 h. After natural cooling, active carbon-enveloped I2 (I2@AC) was obtained.

Current collector materials

In coin cell fabrication, titanium foil (purity: 99.95%, thickness: 0.01 mm) purchased from Tianjin EVS Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. was used as the cathode current collector. For Zn-air battery assembly, carbon paper (Toray Industries, Japan) served as the current collector. In the Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O and Zn | |I₂@AC pouch cells, 316 stainless steel mesh with a 200 mesh size and identical dimensions to the Zn anode was employed. For the quasi-solid SEI Zn | |MnO2 pouch cells, a hydrophobic carbon cloth (model: W1S1011, thickness: 0.41 mm, purchased from Shengernuo Energy Store, Taobao) was used as the current collector. All current collectors were cleaned with anhydrous ethanol prior to use without further surface modification or treatment.

Separator materials

All separators used in this work were obtained from Whatman (UK), model GF/D, composed of glass fiber with a thickness of 675μm and a nominal pore size of 2.7μm. In the assembly of coin cells, one separator per cell was employed. The separators were cut into 17 mm diameter circular discs using a slicing machine (Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd., model: MSK-110) under ambient conditions. For pouch cells assembled with NaV3O8·1.5H2O or I2@AC cathodes, two separators were used for each electrode due to the double-sided coating of active material. These separators were manually cut to dimensions slightly larger than the electrodes to ensure complete coverage and effective ion transport.

Preparation of liquid electrolytes

To prepare the ZnSO4-based electrolyte, a specific amount of ZnSO4·6H2O (or a mixture of ZnSO4·6H2O and MnSO4·H2O, both purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) was dissolved in deionized water to obtain either a 3 M ZnSO4 solution or a mixed electrolyte of 3 M ZnSO4 + 0.2 M MnSO4. The solution was stirred until fully dissolved. It should be noted that the 3 M ZnSO4 + 0.2 M MnSO4 electrolyte was specifically used for assembling full cells coupled with MnO2 cathodes. After preparation, the electrolyte was transferred into glass bottles, sealed, and stored at 25°C. For the alkaline electrolyte, a solution of 6 M KOH + 0.2 M Zn(CH3COO)2 (analytical grade, Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) was prepared under ambient atmosphere at 25 °C. The solution was stored in sealed polypropylene tubes at 25°C and allowed to stand for 6 h before use.

Preparation of gel electrolyte

Preparing a solution of 10 g distilled water and sorbitol in a ratio of 2:1, adding 0.8 g polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and 0.2 g carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), then stirring thoroughly at 90 °C, waiting until PVA and CMC are completely dissolved, and further heating for 1 h. After that, adding 1 g Acrylamide (AM), 20 mg Ammonium persulfate, and 10 mg N, N’-Methylenebis (acrylamide), continue heating and stirring for 0.5 h. After stirring the solution evenly, stop heating. After the solution return to room temperature, inject the solution into a dumbbell-shaped template, put it in the refrigerator and freeze it for 6 h, take it out and defrost it naturally, and then irradiate it with a 365 nm ultraviolet lamp for 1 h to obtain PVA/CMC/PAM hydrogel, and then soak the hydrogel in 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.2 M MnSO4 solution for 20 h.

Preparation of positive electrodes

1) For MnO2 positive electrodes in the coin-type cells, MnO2 powder, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, Arkema, France), and acetylene black (Shenzhen Kejing Zhida Technology Co., Ltd.) were mixed in a mass ratio of 7:2:1. The mixture was ground in an agate mortar until homogeneous. The exact quantities were adjusted according to the number of electrodes to be fabricated. The blended powder was transferred into a slurry mixing container, followed by the addition of a suitable amount of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent. After stirring for 15 min using a slurry mixer (AR100, Shinki Trading Co., Japan), a uniform slurry was obtained. The slurry was then cast onto a titanium foil (Tianjin EVS Chemical Technology Co., Ltd.) that had been cleaned with anhydrous ethanol, using a scraper (Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd.) set at a thickness of 100 μm. The coated electrodes were promptly transferred to a vacuum oven and dried at 60°C for 12 h. The dried films were punched into circular electrodes with a diameter of 12 mm using a cutter (MSK-110, Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd.). The preparation of I2@AC positive electrodes followed a similar procedure, except that the vacuum drying temperature was set to 40°C.

2) For positive electrodes in Zn–air batteries, 1.5 mg of Pt/C catalyst (20 wt% Pt, Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) was dispersed in 0.288 mL of anhydrous ethanol and 0.0012 mL of Nafion 117 perfluorinated resin solution (Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.). The suspension was drop-cast onto carbon paper (Toray, Japan) and allowed to dry naturally. The coated area was controlled to 1 cm2.

3) For NaV3O8·1.5H2O positive electrodes in pouch-type cells, NaV3O8·1.5H2O powder, PVDF, and acetylene black were mixed in a mass ratio of 7:2:1 with a total mass of 10 g. After adding 20 mL NMP and thorough grinding, a viscous slurry was obtained and uniformly coated on both sides of a 10*10 cm stainless-steel current collector. The coated electrode was vacuum dried at 60°C for 4 h, followed by calendaring using a roller press (MSK-HRP-MR100B, Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd.) to achieve a flat surface. The electrode was further dried until complete solvent removal. The I2@AC positive electrode in pouch-type cells was prepared in a similar manner, using 3 g of solid materials and 6 mL of NMP, and dried at 40°C.

4) For flexible MnO2 positive electrodes, MnO2, PVDF, and acetylene black were mixed in a mass ratio of 7:2:1 with a total mass of 10 g. After the addition of 20 mL NMP, the mixture was ball-milled at 300 rpm for 6 h to form a homogeneous slurry. The slurry was cast onto hydrophobic carbon cloth (scraper thickness: 100 μm; scraper from Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd.) and vacuum dried at 80°C for 12 h. The dried film was then pressed under a load of 1 MPa for 2 min.

Note that in coin cells, the mass loading of MnO₂ was 1 mg cm−2, and that of I2@AC ranged from approximately 0.4–0.6 mg cm−2. The electrode diameter was 12 mm. For air positive electrode, the Pt loading was 1.5 mg cm⁻², the active material was drop-cast over an area of 1 cm2, and the total electrode size was 6*2.5 cm. Under such low loadings, the thickness of the positive electrode was considered equivalent to that of the current collector. For NaV3O8·1.5H2O pouch electrodes, the active material loading was approximately 17.5 mg cm−2 with a thickness of ~2 mm and a size of 10*10 cm. For I2@AC pouch electrodes, the loading reached 21.88 mg cm−2, with a thickness of ~1.5 mm and size of 4 × 6 cm. For flexible MnO₂ electrodes, the active material loading was approximately 1.8–2.0 mg cm−2 (exact values are shown in the figures), with a thickness of ~0.42 mm and dimensions of 3*2 cm.

Battery Assembly and Testing

In the assembly of coin cells, 2032-type 304 stainless steel coin cell casings, along with corresponding gaskets (1 mm thickness) and spring clips, are used. The electrolyte volume is 140 μL, and the pipette used is from DRAGONLAB, with polypropylene tips. Specifically, for the Zn|Cu asymmetric cell, 12 mm diameter original copper foil (30 μm thickness) is used, while the coin full cell utilizes 12 mm diameter single-sided coated cathode sheets. After assembly, the cells are left to stand for 6 h to ensure full electrolyte infiltration before electrochemical testing is performed.

For the Zn-air batteries, Zn anodes measuring 2.5 × 6 cm, along with corresponding cathodes, are assembled into a 5 mL Zn-air battery mold. The electrolyte volume is 5 mL, and the electrolyte is transferred using the same method, with no need for pre-wetting. For the assembly of Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O and Zn | |I2@AC pouch cells, three anodes, four separators, and two double-sided coated cathodes are used. The electrodes are stacked in the order of anode-cathode-anode-cathode-anode, with the specific parameters of the current collector materials provided earlier. The current collector tabs are reserved portions, with the anode tabs made from Zn metal and the cathode current collectors being stainless steel mesh. The electrolyte volume is approximately 40 mL, and during the electrode stacking process, the electrolyte is directly added to the separators. After the cells are sealed, a pressure of approximately 10,000 N is applied using a mold to expel excess gas, followed by thermal sealing while maintaining external pressure. The cells are then left to rest for 6 h before undergoing cycling tests.

For the Zn | |MnO2 flexible cells, a flexible MnO2 cathode loaded on carbon cloth is used, with the dimensions provided earlier. A semi-solid gel electrolyte (3.2 × 2.2 cm, 0.15 mm thickness) is employed, with conductive copper tape used for the current collector tabs. The anode consists of 10 μm Zn foil, sized to match the cathode, with tabs reserved for Zn metal. During assembly, the three components are stacked together, then vacuum-sealed and heated using aluminum-plastic film. After resting for 10 h, the cells are subjected to testing.

Unless otherwise specified, the cells are typically tested in a 25 °C ambient environment. For cells tested at specific temperatures as mentioned in the text, the tests are conducted in a high and low-temperature testing chamber (Model: 50 L, Guangdong Aisrui Instrument Technology Co., Ltd.), using static heating. Large-area cells are tested in a 25 °C ambient environment without local temperature testing. All of the galvanostatic charge/discharge of symmetrical and asymmetrical cells were carried out on a CT3001A cell testing system (Wuhan LAND Electronic Co. Ltd.).

Material characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement was performed using a PANalytical, Empyrean, CuKa radiation (λ = 1.54065 Å). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurement was performed using the Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer (Al Kα radiation) with a scanning rate of 0.05 eV per step. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra were obtained on IR Affinity-1. Surface morphology and element mapping of the Zn anode were examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, JEOL, JSM-7800F) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS, Ame tek, TEAM Octane Plus). High Resolution Transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, JEOL-F200) equipped with an Oxford energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS, Silicon Drift Detector). Operando optical observation was carried out on Motic BA310Met, coupling a CHI760e electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua). Electron Backscattered Diffraction (EBSD) was performed using Bruker QUANTAX CrystAlign 400i. The Young’s modulus was measured by Atomic Force Microscope (AFM). The model of AFM is Dimension ICON, and the probe used is Bruker TAP 525 A, k is 200 N/m. Time of Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) was measured with ION TOF-SIMS 5. H2 evolution was monitored by the in-situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) analysis during Zn plating at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 repeating the step of discharge/charge for 1 h and resting for 1 h. In situ pH monitor was measured on PHSJ-6L (Shanghai Leici), coupling a CHI760e electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua), and the Zn | |Zn symmetrical cells were assembled in an electrolytic tank.

Electrochemical measurement

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was performed on a Biologic VSP-300 electrochemical workstation under open-circuit voltage (OCV) conditions. A sinusoidal excitation signal with an amplitude of 10 mV (rms) was superimposed around the stabilized OCV. The impedance spectra were recorded over a frequency range from 1 MHz to 0.1 Hz, with approximately 10 data points collected per frequency decade, resulting in a total of ~60 frequency points. Prior to measurement, the cells were rested at ambient temperature for 2 h to ensure OCV stabilization. No external polarization or galvanostatic bias was applied during the EIS acquisition. All charge/discharge cycling tests were performed in galvanostatic mode. The cut-off potential was set as follows: 0.2–1.6 V for Zn | |NaV3O8·1.5H2O pouch cells, 0.8–1.8 V for Zn | |MnO2 cells, and up to 1.0 V for Zn | |Cu cells. For cyclic voltammetry and linear sweep voltammetry tests, the scan rate was fixed at 1 mV s−1. The CV scan range was 0.8–1.8 V for Zn | |MnO2 full cells, and -0.2–1.0 V for Zn | |Cu cells. Tafel plots were obtained by linear sweep within ±0.225 V vs. Ag/AgCl, while HER polarization curves were recorded in the range of -1.0 to 1.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Coulombic efficiency was calculated by dividing the discharge capacity by the charge capacity for each cycle and multiplying by 100%.

Mechanical measurement

The nanomechanical properties of Zn negative electrodes were quantitatively mapped by using an atomic force microscope (Dimension Icon, Bruker) operating in the force volume (FV) mode. In the FV measurement, force curves (FCs) are obtained by vertically indenting the AFM-tip at a regular matrix in a selected area on Zn negative electrodes, which yields the local mechanical response precisely. The system acquired 4096 points FCs across a 64×64 grid through controlled vertical indentation (ramp length: 5.0 μm, approach velocity: 20.0 μm s−1, maximum load: 3.5 μN). Three FV measurements were performed in different macroscopic positions to improve the statistical robustness of the nanomechanical dataset at room temperature (T = 24 °C). A calibrated TAP525A probe (spring constant: 200 N m−1 via Sader method37, semi-angle: 30°) enabled acquisition of topographical and mechanical information at the same time through the FV measurement38. Young’s moduli were evaluated by data analysis performed in a Matlab environment with a routine described in a previous report39. Normally, force curves were pre-processed to obtain force curves (F [nN]) vs. indentation (δ [nm]) after the FV measurements. Then the indentation curves are fitted using the Sneddon model for sharp probes40,41:

where E, υ, and θ denote Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and averaged half-opening angle of the four-sided pyramidal indenter, respectively. The mechanical mapping and the collective histogram for statistical analysis are obtained by using the logarithmic Young’s moduli values. The error characteristics are determined by both the intrinsic error of a single FV and the variation arising from measurements in different macroscopic locations on the same Zn negative electrode.

DFT calculation

The total energy and electronic calculations are implemented by the VASP code based on the density functional theory42. The GGA-PBE functional is applied for the exchange and correlation interaction of electrons43. The DFT-D3 functional is used to describe the weak van der Waals interaction44. The plane-wave cut-off energy is set to 400 eV. The Gamma point in the Brillouin zone is selected for integration. Besides, the total energy tolerance for the systems is set to 10−5 eV in the iteration solution of the Kohn-Sham equation. And the force on each atom has declined to 0.05 eV/Å after geometry optimization.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are presented in the Manuscript and Supplementary Information or are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, W. & He, G. J. Solid-electrolyte interphase chemistries towards high-performance aqueous zinc metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218466 (2023).

Zhang, M. H. et al.Dynamically interfacial pH-buffering effect enabled by N-methylimidazole molecules as spontaneous proton pumps toward highly reversible zinc-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208630 (2023).

Li, F. et al. A Theory-driven complementary interface effect for fast-kinetics and ultrastable Zn metal anodes in aqueous/solid electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2204365 (2023).

Ouyang, K. F. et al. Trace-additive-mediated hydrophobic structure editing of aqueous zinc metal batteries for enabling all-climate long-term operation. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 5229–5239 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Interfacial engineering strategy for high-performance Zn metal anodes. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 6 (2022).

Nie, W. et al. Design strategies toward high-performance Zn metal anode. Small Methods 8, 2201572 (2024).

Liu, Z. X. et al. Unraveling paradoxical effects of large current density on Zn deposition. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404140 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Stable Zn anodes with triple gradients. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207573 (2023).

Glatz, H., Tervoort, E. & Kundu, D. Unveiling critical insight into the Zn metal anode cyclability in mildly acidic aqueous electrolytes: implications for aqueous zinc batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 3522–3530 (2020).

Lv, S. J. et al. Hydrophilic-zincophobic separator enabling by crystal structure regulation toward stabilized Zn metal anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315910 (2024).

Zhao, Q. G. et al. Competitive tradeoff between zn deposition and hydrogen evolution reaction on zn-metal anode. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 4102–4110 (2024).

He, P. & Huang, J. X. Chemical passivation stabilizes Zn anode. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109872 (2022).

Fu, M. et al. Building sustainable saturated fatty acid-zinc interfacial layer toward ultra-stable zinc metal anodes. Nano Lett. 23, 3573–3581 (2023).

Chen, X. J. et al. Polyvinyl alcohol coating induced preferred crystallographic orientation in aqueous zinc battery anodes. Nano Energy 98, 107269 (2022).

Chen, P. et al. An artificial polyacrylonitrile coating layer confining zinc dendrite growth for highly reversible aqueous zinc-based batteries. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100309 (2021).

Cai, X. et al. Polymer coating with balanced coordination strength and ion conductivity for dendrite-free zinc anode. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307727 (2024).

Hong, L. et al. Self-adapting and self-healing hydrogel interface with fast Zn2+ transport kinetics for highly reversible Zn anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300952 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Enabling and boosting preferential epitaxial zinc growth via multi-interface regulation for stable and dendrite-free zinc metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400613 (2024).

Yan, H., Li, S., Nan, Y., Yang, S. & Li, B. Ultrafast zinc–ion–conductor interface toward high-rate and stable zinc metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100186 (2021).

Guo, N. et al. Stabilizing zn metal anode through regulation of Zn ion transfer and interfacial behavior with a fast ion conductor protective layer. Small 19, 2303963 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Boosting tough metal Zn anode by MOF layer for high-performance zinc-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 71, 103616 (2024).

Wan, H. L. et al. Critical interphase overpotential as a lithium dendrite-suppression criterion for all-solid-state lithium battery design. Nat. Energy 8, 473–481 (2023).

Wang, C. H. et al. Identifying soft breakdown in all-solid-state lithium battery. Joule 6, 1770–1781 (2022).

Wang, H. R. et al. Bifunctional dynamic adaptive interphase reconfiguration for zinc deposition modulation and side reaction suppression in aqueous zinc ion batteries. ACS Nano 17, 11946–11956 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Regulating interfacial reaction through electrolyte chemistry enables gradient interphase for low-temperature zinc metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 5443 (2023).

Huang, S. Y. et al. Molecularly engineered multifunctional imide derivatives for practical Zn metal full cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 7870–7881 (2024).

Yang, K. et al. Poloxamer pre-solvation sheath ion encapsulation strategy for zinc anode–electrolyte interfaces. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 209–217 (2024).

Han, L. et al. Lotus effect inspired hydrophobic strategy for stable Zn metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308086 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Reversing zincophobic/hydrophilic nature of metal-N-C via metal-coordination interaction for dendrite-free Zn anode with high depth-of-discharge. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311637 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Construct robust epitaxial growth of (101) textured zinc metal anode for long life and high capacity in mild aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2305988 (2024).

Ouyang, K. et al. A New insight into ultrastable Zn metal batteries enabled by in situ built multifunctional metallic interphase. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109749 (2022).

Hu, X. et al. External-pressure–electrochemistry coupling in solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 305–320 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. A rechargeable zinc-air battery based on zinc peroxide chemistry. Science 371, 46–51 (2021).

Zhang, N. et al. Direct self-assembly of MXene on Zn anodes for dendrite-free aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2861–2865 (2021).

Wan, F. et al. Aqueous rechargeable zinc/sodium vanadate batteries with enhanced performance from simultaneous insertion of dual carriers. Nat. Commun. 9, 1656 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Zhu, Y., Yu, M., Jiao, Y. & Huang, Y. Development of long lifespan high-energy aqueous organic||iodine rechargeable batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 6489 (2022).

Galluzzi, M. et al. Space-resolved quantitative mechanical measurements of soft and supersoft materials by atomic force microscopy. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e327 (2016).

Butt, H. J. & Jaschke, M. Calculation of thermal noise in atomic-force microscopy. Nanotechnology 6, 1–7 (1995).

Galluzzi, M. assimiliano et al. Atomic force microscopy methodology and AFmech suite software for nanomechanics on heterogeneous soft materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3584 (2018).

Sneddon, I. N. The relation between load and penetration in the axisymmetric boussinesq problem for a punch of arbitrary profile. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 3, 47–57 (1965).