Abstract

Reconstruction of metal-organic frameworks often occurs under reaction conditions, thereby impeding true active species identification and hindering mechanism understanding. Herein, we present the mechanistic insight underlying the electrochemical synthesis of deprotonated anion of H2O2 (HO2−) via 2e− oxygen reduction by ultrathin Ni-benzenedicarboxylic acid (NiBDC), guided by its thickness-dependent performance and pH-induced reconstruction behavior. The real active species are identified as alkaline-reconstructed β-Ni(OH)2 that is chemically coupled with 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid residual ligand. The hybrid catalyst is characterized to exhibit an optimized surface electronic structure, which improves the intrinsic activity and selectivity. Operando characterization and theoretical simulations further reveal that the residual ligand functionalization significantly boosts the formation and facilitates the adequate binding of *OOH intermediates. Thus, the ligand-functionalized Ni(OH)2 exhibits high HO2− selectivity (>90%) in 0.1 M KOH across a broad current density up to 200 mA cm−2. Moreover, high HO2− production rate of 13.7 mol gcat−1 h−1 with significant accumulation of 2.0 wt.% HO2− under alkaline conditions is achieved at 200 mA cm−2 over 100 h, suggesting the promising potential for large-scale electrosynthesis of HO2− in industrial applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) finds widespread applications across various industries, including textile bleaching, pharmaceuticals, wastewater treatment, chemicals, energy carriers, and semiconductor manufacturing, with a current market value of around 3.5 billion USD, growing at a 5% compound annual growth rate. Therefore, the development of green, efficient, and economically viable methods for H2O2 production is of great significance1,2,3. Currently, the predominant production of H2O2 relies on the traditional anthraquinone method4,5,6, however, it is constrained by environmental concerns, complex processes, intensive energy consumption, hazardous materials usage, and the necessity of stabilizers during transportation7,8. The renewable energy-powered electrochemical oxygen reduction (ORR) via the two-electron (2e−) transfer pathway offers a green, efficient and economic approach for distributed “on-demand/on-site” H2O2 generation, thereby significantly mitigating expenses and risks associated with transportation and storage9,10,11. Especially, the 2e− ORR under an alkaline environment exhibits enhanced catalytic activity and optimized selectivity towards the deprotonated anion of H2O2 (HO2−) due to the pH effect on the catalytic process and ORR mechanism12. It is worth noting that HO2− is particularly suitable for applications where the separation of peroxide from alkaline is unnecessary13. For example, biomass valorization and pulp bleaching require both high pH (>11.6) and high concentration (>1 wt.%) of peroxide14,15.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are widely recognized as promising electrodes for electrochemical H2O2 generation, owing to their exceptional features, such as large specific surface area, adjustable porosities, periodic active sites, and composition diversity16,17. However, their electrocatalytic performance is usually thickness-dependent due to their limited electrical conductivity, restricted mass permeability, and active centers blocked by the organic ligands or residual solvents. Therefore, the development of ultrathin 2D MOFs, with maximized exposure of unsaturated metal sites and enhanced mass/electron transport, is highly desirable18,19. Nonetheless, potential in-situ reconstructions of the electrocatalysts, especially for MOFs with weak coordination bonds between metal nodes and organic linkers, hinder the identification of intrinsic catalytic species and the mechanistic investigation of key effects20,21,22,23,24. Additionally, the water hydrolysis of MOFs under the alkaline environment is also non-negligible25. This aspect is often ignored and overshadowed by the initial charging current spike, leading to a misleading declaration of “stable MOF electrocatalyst” based solely on the minimal performance difference observed during long-term test26,27. Although the reconstruction phenomenon in Fe/Co/Ni based-MOFs for alkaline oxygen evolutions, including partial28 and complete29 reconstruction, has gained widespread recognition, its investigation in 2e- ORR is rarely explored30.

Herein, we focused on the 2e- ORR of Ni3(OH)2(BDC)2(H2O)4 (NiBDC, where BDC represents 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate) for HO2- production. The choice of a Ni-based MOF was based on its advantageous features, including tunable electronic structure, moderate binding affinity for oxygen intermediates, and stability in alkaline conditions31. By optimizing the dissolution-reprecipitation rate during the transformation of Ni(OH)2 precursors, we successfully obtained NiBDC with a wide range of thicknesses, including ultrathin (utn-, 6 nm), thin (tn-, 24 nm), thick (tk-, 90 nm), and bulk (b-, 120 nm) NiBDC. The as-prepared NiBDC exhibits thickness-dependent 2e- ORR performance with thinner layers demonstrating better performance. Combined with in-situ and ex-situ characterizations, we revealed that the surface partially reconstructed BDC-functionalized Ni(OH)2 derived from utn-NiBDC is the real active species for 2e- ORR. Moreover, operando Raman and ATR-FTIR spectra, along with theoretical simulations, identified different rate-determining steps (RDS) between utn-NiBDC and ultrathin Ni(OH)2, indicating the significant impact of the residual BDC functionalization on boosting the proton-involved steps and providing appropriate binding for the *OOH intermediate, thereby ensuring enhanced 2e- ORR performance. As a result, the utn-NiBDC exhibits promising 2e- ORR performance at an industrial current density of 200 mA cm-2 and a high HO2- production rate of 13.7 mol gcat-1 h-1 with 92% HO2- selectivity in a flow cell, with stability maintained over 100 h. The HO2- concentration accumulated after 6 h reached 2.0 wt.%, which is sufficient to meet the requirements for biomass valorization.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of utn-NiBDC and its 2e− ORR performance

The synthesis of utn-NiBDC was achieved by using Ni(OH)2 (Supplementary Fig. 1) as Ni source in a mixed solution of water and dimethylformamide (Fig. 1a). By precisely adjusting the dissolution and reprecipitation rates through facile regulation of the solution ratio between water and dimethylformamide, NiBDC with varying thicknesses could be readily obtained. The key to the synthesis of ultrathin NiBDC lies in the utilization of a low percentage of water, which effectively retards the leaching of Ni2+ ions by suppressing the release rate of protons from BDC, an organic ligand known for its weak acidic nature. Thus, the corresponding low local Ni2+ concentration leads to a specific crystal orientation growth, favoring the formation of utn-NiBDC32. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show clearly NiBDC morphological variation with thickness ranging from ultrathin (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2a), thin (Fig. 1c), thick (Fig. 1d), and bulk (Supplementary Fig. 3a) nanoribbons, demonstrating that the growth direction of the MOF was restricted with the rational control on Ni2+ releasing rate. The thickness of utn-, tn-, tk-, and b-NiBDC are confirmed as ~6, ~24, ~90, and ~120 nm, respectively, as revealed by the atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Fig. 1e–g and Supplementary Fig. 3b). The number of layers for utn-NiBDC is about 7 based on the crystal structure33. Moreover, the powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD) patterns (Supplementary Fig. 2b) of all three NiBDC samples agree well with the standard [Ni3(OH)2(BDC)2(H2O)4]·2H2O (JCPDS card No. 35-1677), confirming their single-crystalline nature. The peak intensity ratio between the (100/101) plane reduces, and the characteristic peaks broaden as the thickness of NiBDC decreases, demonstrating successful regulation of the crystal growth orientation of NiBDC through our strategy.

a Schematic illustration for ultrathin NiBDC fabrication. b–d TEM images and e–g AFM images (inset is the corresponding height profile measured along the dashed line) of b, e utn-NiBDC, c, f tn-NiBDC, and d, g tk-NiBDC. h Polarization curves of Ni-based MOF catalysts recorded at 1600 rpm and a scan rate of 5 mV s-1, together with the detected HO2- currents on the ring electrode (upper panel) at a fixed potential of 1.2 V vs. RHE (100% iR-corrected). The resistance values of utn-NiBDC, tn-NiBDC, tk-NiBDC, and b-NiBDC are 26.0 ± 1 Ω, 27.5 ± 1 Ω, 29.7 ± 1 Ω and 35.6 ± 1 Ω, respectively. i Corresponding calculated HO2- selectivity. j The polarization curves of utn-NiBDC before and after the stability test (100% iR-corrected). Source data for Fig. 1e–j are provided as a Source Data file.

The electrocatalytic 2e- ORR of the NiBDC with different thicknesses was examined in O2-saturated KOH (0.1 M) using a rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) with a collection efficiency of 0.424 (Supplementary Fig. 4). All NiBDC samples follow preferentially 2e- ORR reaction pathway (Fig. 1h), while utn-NiBDC shows a relatively high ring current with optimized HO2- selectivity of ~90% (Fig. 1i), higher than that of tn- (77%), tk- (68%), and b-NiBDC (67%). The 2e- Tafel slope of utn-NiBDC (118 mV dec-1) is lower than those of other NiBDC samples, indicating its faster reaction kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 5). The corresponding electrons transferred number (n) and Faradaic efficiency (FE%) during the reaction are further calculated (Supplementary Fig. 6a), suggesting a clear thickness-dependent 2e- ORR performance relationship (Supplementary Fig. 6b). The utn-NiBDC exhibits the largest electrochemical surface area (ECSA), further verifying the successful thickness manipulation of NiBDC (Supplementary Fig. 7). More importantly, the activity and selectivity of utn-NiBDC are well maintained after both 10k cycles accelerated degradation test in RRDE (Fig. 1j) and 7 h on-site H-type cell chronoamperometry test (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating good electrocatalytic stability of utn-NiBDC.

Investigation on the reconstruction of utn-NiBDC

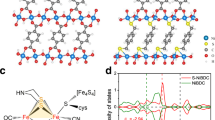

Although the utn-NiBDC exhibits promising stability, the electrocatalytic performance stability of the MOFs does not guarantee their chemical stability, hindering the identification of active species. Specifically for Ni-based materials, Ni-MOF34, oxygen vacancy (Ov) enriched NiO35, Ni(OH)236 and β-NiOOH37 are all reported as active species for 2e- ORR. The chronoamperometry curve of utn-NiBDC exhibits a pronounced response at 0.2 V, characterized by a remarkable initial surge within the first 15 s followed by a sustained plateau (Supplementary Fig. 9), validating a rapid activation process38. After reconstruction, the selectivity of utn-NiBDC initially increases and then stabilizes during the detachment of residual BDC ligand, indicating the existence of an optimal surface BDC ratio. To investigate the possible reconstruction phenomenon and its corresponding mechanism, we characterized the post-reacted utn-NiBDC after a specific reaction time (PR-utn-NiBDC). TEM images revealed defect-rich morphologies of PR-utn-NiBDC with no discernible changes in thickness (Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating the occurrence of NiBDC reconstruction during the reaction. As shown in Fig. 2a, complete structure transformation from MOF into β-Ni(OH)2 can be observed in XRD patterns of PR-utn-NiBDC after a reaction time of 1 h in 0.1 M KOH. It is worth noting that the reconstruction occurs in all NiBDC with different thicknesses (Supplementary Fig. 11), demonstrating that the above-measured performance of NiBDC reflects the properties of the reconstructed catalysts. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11d, utn-NiBDC exhibits the lowest charge transfer resistance, indicating the enhanced ORR performance of ultrathin catalysts may originate from the more exposed active sites, boosted electron transfer, and accelerated mass transport39,40,41. Extended reaction time further confirms β-Ni(OH)2 as the final and real active species. Moreover, the reconstruction receded as the pH of electrolytes decreased (Fig. 2b), with the activity and selectivity dropping rapidly (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). Even after a 12 h chronoamperometry test at 0.2 V, the XRD pattern of PR-utn-NiBDC at pH 9 agrees well with the MOF crystalline (Supplementary Fig. 12c), verifying that the reconstruction mechanism in 2e- ORR potential region (0.8 to 0.2 V vs. RHE) is pH-dependent. This observation agrees with the fact that oxidation potentials of Ni2+/Ni3+ are approximately 1.3 V vs. RHE42, thereby excluding the possibility of NiOOH as active sites within this specific potential range (0.8 to 0.2 V vs. RHE). To further investigate the pH-induced reconstruction mechanism, we directly treated utn-NiBDC at 0.1 M KOH (utn-NiBDC+KOH). Time-dependent XRD patterns (Fig. 2c) demonstrate that utn-NiBDC undergoes reconstruction upon electrolyte contact, as evidenced by the reduction of MOF peaks within 1 min and a transformation from amorphous to crystalline β-Ni(OH)2 over time. Notably, utn-NiBDC+KOH 1 min shows no obvious increase in current in the chronoamperometry test, further confirming the pH-induced reconstruction mechanism. Moreover, the reconstructed PR-utn-NiBDC exhibits a higher ring current than utn-NiBDC in 0.1 M PBS, demonstrating the effectiveness of the reconstruction strategy (Supplementary Fig. 13).

a Time-dependent XRD patterns of PR-utn-NiBDC. b pH-dependent XRD patterns of PR-utn-NiBDC. c Time-dependent XRD patterns of utn-NiBDC in 0.1 M KOH. Elemental mapping of d Cl-utn-NiBDC, e Cl-utn-NiBDC+KOH, and f Cl-utn-NiBDC+KOH for 12 h. g Raman, h FT-IR, and i high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra of utn-NiBDC, PR-utn-NiBDC, utn-NiBDC+KOH, and Ni(OH)2. Source data for Fig. 2a–c and Fig. 2g–i are provided as a Source Data file.

Inspired by the fact that catalyst reconstruction primarily involves the ligand replacement from BDC to OH in Ni coordination, the BDC ligand behaviors during the alkaline-induced reconstruction were explored. Given the significant sensitivity of the C, H, and O elements in the BDC ligand to environmental influences, precisely quantifying its detachment behavior presents a challenge. Consequently, we employed a Cl-substituted BDC-based utn-NiBDC (Cl-utn-NiBDC) for a detailed investigation. As shown in Fig. 2d–f, elemental mapping of Cl-utn-NiBDC before and after KOH treatment illustrates the persistent presence of Cl, 1.0 at.% after 1 h, and 0.5 at.% even after a prolonged time of 12 h, indicating the existence of residual BDC ligand after reconstruction. The presence of BDC ligand was further confirmed through organic elemental analysis, which revealed the existence of chlorine in the Cl-utn-NiBDC after KOH treatment for 1 h and 12 h with content of 3.5 and 2.1 wt.%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Moreover, both the utn-NiBDC following KOH treatment and 2e- ORR for 1 h show two new peaks at 449 and 1050 cm−1 in Raman spectra (Fig. 2g), corresponding to the A1g(T) translational mode and 2nd-order lattice mode of reconstructed Ni-OH43. Meanwhile, the in- and out-of-phase stretching modes of the coordinated carboxylate groups bond with metal centers (located at 1618, 1444 cm−1) and C-H region of the benzene rings in BDC ligands (located at 1139, 865, and 623 cm−1) indicate the reconstructed Ni(OH)2 is residual BDC-functionalized44. Similar results are also observed in the Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra (Fig. 2h). The remaining peaks at 1383 and 1582 cm-1 suggest the residual BDC, while the new peak at 3650 cm-1 demonstrates the formation of Ni(OH)245. The valence state of utn-NiBDC under various treatments was further confirmed by XPS (Supplementary Fig. 14). Notably, PR-utn-NiBDC exhibits relatively low Ni binding energy compared to utn-NiBDC and utn-NiBDC+KOH, suggesting a reduced valent state of Ni species after 2e- ORR process (Fig. 2i). Additionally, no obvious oxidization on Ni can be observed on additional H2O2 without applied voltage (utn-NiBDC+KOH + H2O2) and PR-utn-NiBDC with applied voltage without H2O2 generation (injecting N2 instead of O2), excluding the in-situ oxidization of Ni by the interfacial peroxide (Supplementary Fig. 15). Based on the above analysis, the active species after reconstruction is identified as the residual BDC-functionalized ultrathin Ni(OH)2.

Identification of the role of BDC-functionalization

To pinpoint the actual active species and assess the residual BDC role in reconstructed utn-NiBDC during 2e- ORR, an ultrathin Ni(OH)2 (utn-Ni(OH)2) nanosheet of similar thickness (7.8 nm) to utn-NiBDC (6 nm) was obtained for compare (Supplementary Fig. 16). X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectroscopy46 was performed to investigate the coordination environment and electronic structure of utn-NiBDC, PR-utn-NiBDC, and utn-Ni(OH)2. The Ni K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of the above samples, along with the references of Ni foil and NiO, show clearly the electronic/valence structures for Ni (Fig. 3a). It is noted that the Ni K-edge XANES spectra of the as-prepared samples exhibit NiO-like features. The inset in Fig. 3a highlights the pre-edge features of Ni K-edge XANES spectra, in which the risen edge of the PR-utn-NiBDC is slightly lower than those of utn-NiBDC and utn-Ni(OH)2, clearly indicating the unique electronic structure of the Ni with residual BDC functionalization and H2O2 reduction. Fourier-transformed (FT) k3-weighted extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were employed to further analyze the coordination environment of the samples. Figure 3b illustrates that the peak area of PR-utn-NiBDC at ~1.6 Å (associated with Ni-O path) is significantly smaller than that of utn-NiBDC and utn-Ni (OH)2, demonstrating a lower oxygen coordination number. This observation aligns with the wavelet transform (Supplementary Fig. 17). Quantitative least-square EXAFS curve-fitting parameters (Supplementary Fig. 18–22 and Supplementary Table 2) reveal a reduced oxygen coordination number in PR-utn-NiBDC (about 5.85) compared to utn-NiBDC (5.99) and utn-Ni(OH)2 (6.21), implying that a single carboxyl group of the residual BDC is coordinated with the Ni. Additionally, the influence of existing Ov is eliminated by consistent electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra between PR-utn-NiBDC and utn-Ni(OH)2 (Fig. 3c).

a XANES spectra of utn-NiBDC, PR-utn-NiBDC, and utn-Ni(OH)2 at Ni K-edge. b Corresponding FT-EXAFS spectra. c EPR spectra of PR-utn-NiBDC and utn-Ni(OH)2. d Polarization curves of utn-NiBDC, utn-Ni(OH)2, and XC-72 recorded at 1600 rpm and a scan rate of 5 mV s-1, together with the detected HO2- currents on the ring electrode (upper panel) at a fixed potential of 1.2 V vs. RHE (100% iR-corrected). The resistance values of utn-NiBDC, utn-Ni(OH)2, and XC-72 are 26.0 ± 1 Ω, 25.1 ± 1 Ω and 24.3 ± 1 Ω, respectively. e Corresponding calculated HO2- selectivity obtained at 0.6 V vs. RHE. Operando Raman spectra of f utn-NiBDC and g utn-Ni(OH)2 (non iR-corrected). Operando ATR-FTIR spectra of h utn-NiBDC and i utn-Ni(OH)2 (non iR-corrected). Source data for Fig. 3a–i are provided as a Source Data file.

Benefiting from the unique residual BDC ligand coordination structure, utn-NiBDC exhibits a higher ring current than that of utn-Ni(OH)2 and conductive agent XC-72 (Fig. 3d). Calculations of HO2- selectivity, electron transfer number and corresponding FE% demonstrate that Ni(OH)2 coordinated with a residual BDC ligand favors the 2e- pathway (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 23a). The 2e- Tafel slope of utn-NiBDC (118 mV dec-1) is lower than that of utn-Ni(OH)2 (125 mV dec-1), while the 4e- Tafel slope displays an opposite trend, suggesting the crucial role of the residual BDC ligand in selective regulation (Supplementary Fig. 23b, c). The ECSA of utn-NiBDC (37.3 cmECSA2) is higher than utn-Ni(OH)2 (4.5 cmECSA2), endowing utn-NiBDC with increased O2 adsorption capacity (Supplementary Fig. 24)47. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 25, the dramatic drop in disk current after adding thiocyanate ions (SCN−) confirms that the Ni species are the active sites toward 2e− ORR48. Moreover, the possible active species of Ni(OH)2 with intentionally added BDC and NiO were excluded by testing the counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 26).

Exploration of the mechanism

The catalytic activity and selectivity of 2e- reduction of O2 to HO2- at pH>11.6 are associated with the binding energy of the key reaction intermediate (*OOH)49. For catalysts with weak *OOH adsorption, O2 activation (Eq. 1) is the rate-limiting step (RDS), while for those with strong *OOH binding, *OOH desorption (Eq. 2) becomes the RDS.

It is necessary to avoid excessively strong *OOH adsorption, as this favors O-O bond dissociation, leading to the predominant 4e- pathway.

Operando Raman spectroscopy was performed spanning 0.8 to 0.2 V vs. RHE to probe the *OOH intermediate during the 2e- ORR. A pronounced Raman band at approximately 732 cm-1 appeared at 0.7 V (Fig. 3f), attributed to the O-O stretching vibration from *OOH bridge-to-bridge adsorption structure on the electrocatalyst surface50, indicating the *OOH desorption as the RDS. Conversely, utn-Ni(OH)2 displays no evident new peak upon potential decreases (Fig. 3g), suggesting O2 activation as the RDS. Furthermore, operando attenuated total reflectance FT-IR (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy was performed for in-depth mechanistic insight. As shown in Fig. 3h, a major peak at ~1258 cm-1 and a weak peak at ~1647 cm-1, attributable to the O-O stretching mode of the surface-adsorbed OOH and H2O species51, respectively, emerged and increased with decreasing potential applied on utn-NiBDC. Here, we are unable to distinguish whether the surface-adsorbed OOH species originate from the *OOH intermediate or the physically adsorbed HO2- products. However, utn-NiBDC exhibited a much stronger intensity of OOH species than utn-Ni(OH)2, implying that the introduced BDC ligand in the asymmetrical Ni active sites played a dominant role in promoting proton-involved steps to ensure a rapid formation of the key OOH* intermediate, thus accelerating the whole kinetics of the 2e- ORR electrolysis. Moreover, a negative peak at around 1468 cm-1 is assigned to the adsorbed O2 species, demonstrating that the lack of active surface-adsorbed oxygen is a critical factor limiting the reaction kinetics in utn-Ni(OH)2 (Fig. 3i)52. Supplementary Fig. 27 illustrates that utn-NiBDC exhibits relatively low charge-transfer and mass-transfer resistances compared to utn-Ni(OH)2 under kinetic-relative regions in operando electrochemical impendence spectra (EIS)53. The narrower half-width of the characteristic peak in Bode plots for utn-NiBDC, relative to utn-Ni(OH)2, signifies accelerated electron transfer and enhanced surface reaction kinetics for *OOH intermediates34.

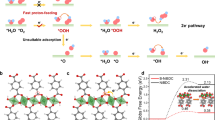

To clarify further the mechanistic insight, first-principles simulations were also performed to rationalize the residual BDC ligand and Ov effect on ultrathin Ni(OH)2 for alkaline 2e- ORR. The computational models for pure Ni(OH)2 (p-Ni(OH)2), Ni(OH)2 with Ov (Ov-Ni(OH)2), Ni(OH)2 with residual BDC ligand functionalization (BDC-Ni(OH)2), and Ni(OH)2 with both OV and BDC (Ov-BDC-Ni(OH)2) were built based on the EXAFS fitting results (Supplementary Fig. 28–31 and Supplementary Data 1). As shown in Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Fig. 32, significant charge redistributions were observed at the Ni-OOH bonding regions, which is likely the origin of the enhanced alkaline 2e- ORR performance. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, the Bader charge transfer between Ni and adsorbed *OOH for p-Ni(OH)2 is only 0.09 e, suggesting that the primary interaction is hydrogen bonding rather than coordination. Upon introducing the BDC ligand and oxygen vacancies to disrupt the symmetry of Ni(OH)2, the Bader charge transfer increases, indicating the adsorption mode changes from hydrogen bonding to ionic bonding. BDC-Ni(OH)2 exhibits the largest Bader charge transfer of 0.79 e, indicating a strong interaction between Ni and OOH species. Moreover, BDC-Ni(OH)2 exhibits a d-band center closer to the Fermi level (-4.06 eV) compared to those of Ov-Ni(OH)2 (-4.279 eV) and Ov-BDC-Ni(OH)2 (-4.465 eV), suggesting the optimal alignment of Ni and OOH near the Fermi level in BDC-Ni(OH)2 (Supplementary Fig. 33). Recent research highlights that the 2e- ORR efficacy is closely linked to the moderate binding strength of *OOH intermediate54. Figure 4e depicts the free energy diagram for the alkaline 2e- ORR pathway at an equilibrium potential of 0.7 V vs. RHE. The free energy difference of *OOH for BDC-Ni(OH)2 compared to the ideal value of 3.52 eV is 0.09 eV, which is less than that of p-Ni(OH)2 (1.19 eV), Ov-Ni(OH)2 (0.83 eV) and Ov-BDC-Ni(OH)2 (0.64 eV), indicating the optimized *OOH binding energy after the introduction of residual BDC ligand. Moreover, stepwise reaction barriers for 2e- ORR were analyzed, focusing on O2 activation and *OOH desorption. Figure 4f illustrates that the RDS for s-Ni(OH)2 and Ov-Ni(OH)2 is O2 activation, but with the introduction of the BDC ligand, it shifts to *OOH desorption, corroborating the operando measurements. Upon considering H2O2 as the final product instead of HO2-, BDC-Ni(OH)2 demonstrates the lowest efficiency in 2e- ORR, signifying that utn-NiBDC is uniquely suited for alkaline 2e- ORR processes (Supplementary Fig. 34). Moreover, the free energy difference of BDC-Ni(OH)2 between *OOH and HO2- is -1.24 eV, which is lower than that of *OOH and *O with -0.19 eV, indicating that 2e- ORR process is more favorable (Fig. 3g). This free energy difference can be attributed to the idea that OOH*-to-O* dissociation is significantly suppressed on the BDC-Ni(OH)2. Overall, both operando characterizations and theoretical simulations suggest that the residual BDC functionalization significantly boosts the proton-involved steps and provides appropriate binding for the *OOH intermediate, thereby ensuring enhanced 2e- ORR performance.

Computational models and localized electric field distributions of a p-Ni(OH)2, b Ov-Ni(OH)2, c BDC-Ni(OH)2, and d Ov-BDC-Ni(OH)2. The pink, red, brown, and green spheres represent H, O, C, and Ni, respectively. e Free energy diagram for O2 to HO2- at 0.7 V. f Calculated energy barriers for all models of 2e- ORR with the final product as HO2-. g Calculated energy diagram for 2-electron and 4-electron ORRs of BDC-Ni(OH)2. Source data for Fig. 4e–g are provided as a Source Data file.

High-rate HO2 − electrochemical production

A three-compartment flow cell (Supplementary Fig. 35) was constructed to evaluate the 2e− ORR performance and applicability of the utn-NiBDC electrocatalyst towards industrially applied current densities. The utn-NiBDC exhibited significantly higher current density than that of utn-Ni(OH)2 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 36). Notably, 130 mV is saved in utn-NiBDC compared with utn-Ni(OH)2 at the same applied current density of 200 mA cm-2. The HO2- FE of utn-NiBDC over a range of current densities from 25 to 200 mA cm-2 remains around 90%, surpassing the FE of approximately 40% for utn-Ni(OH)2 (Fig. 5b). Benefited from the unique role of the BDC ligand and in-situ reduction by the generated HO2-, utn-NiBDC achieved high HO2- production rate of 13.7 mol gcat−1 h−1, significantly greater than utn-Ni(OH)2 and the state-of-the-art 2e− ORR-to- HO2− electrocatalyst reported to date (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 37). Moreover, a prolonged stability test for utn-NiBDC at a current density of 200 mA cm-2 shows good durability over 100 h without evident degradation (Fig. 5d), highlighting the chemical robustness of the residual BDC ligand functionalized catalyst (Supplementary Figs. 38–40). Such a device produces HO2- with a high concentration of 2.0 wt.% within 6 h and is maintained stably and continuously in alkaline conditions (Fig. 5e). Increasing or decreasing the solution pH cannot yield a higher concentration of HO2-, due to the trade-off between selectivity and decomposition rate (Supplementary Fig. 41).

a Polarization curves of the flow cell reactors using utn-NiBDC and utn-Ni(OH)2 (100% iR-corrected). The corresponding electrode surface area is 1 cm2. The resistance values of utn-NiBDC and utn-Ni(OH)2 are 4.2 ± 0.1 Ω and 4.4 ± 0.1 Ω, respectively. b HO2- Faradaic efficiency of utn-NiBDC under different current densities, the error bars are based on three parallel experiments. c Current density and hydrogen peroxide production rate of utn-NiBDC compared to those of other state-of-the-art catalysts (Supplementary Table 4). d Stability test of the flow cell at the current density of 200 mA cm-2 (100% iR-corrected). e Corresponding HO2- concentration. Source data for Fig. 5a–e are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, we present NiBDC MOF with different thicknesses as highly active alkaline 2e− ORR electrochemical pre-catalysts prepared by a facile dissolution-reprecipitation procedure. Utn-NiBDC with a thickness of 6 nm exhibits the highest HO2- electrosynthesis activity among the NiBDC, demonstrating a thickness-performance relationship. The real active species is identified as the residual BDC ligand functionalized ultrathin Ni(OH)2 originated from pH-induced reconstruction, confirmed by the ex-situ XRD patterns and Cl labeling experiment. Moreover, operando characterizations and DFT calculations suggest the introduction of a BDC ligand on Ni(OH)2 can tune the *OOH adsorption energies and boost the proton-involved steps. Finally, utn-NiBDC was also evaluated in a flow cell-based alkaline electrolyzer at industrially current density, long stability of 100 h, high FE of 90% and production rate of 13.7 mol gcat−1 h−1 was obtained, demonstrating its promising application for hydrogen peroxide production. Overall, our work highlights the reconstruction of MOF during the 2e− ORR process. Both the synthetic strategy and the residual ligand effect reported here can guide future MOF pre-catalyst design with improved performance for large-scale hydrogen peroxide production.

Method

Chemicals and materials

Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 99%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%), potassium hydroxide (KOH, 99.99%) N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.8%), 1,4-benzene dicarboxylate (BDC, 99%), and 2-chloro-1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (Cl-BDC) were purchased from Aladdin Ltd. Ethanol (EtOH) and 1-propanol was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical. Nafion dispersion (5% w/w in water and 1-propanol) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Carbon black (Vulcan XC 72) was purchased from the Fuel Cell Store. The deionized (DI) water was prepared with a Milli-Q ultra-pure water system (resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm). All chemical reagents were used as received without further purification.

Experimental procedures

Synthesis of Ni-based MOF nanoribbon

The prepared Ni(OH)2 nanosheet (0.25 mmol) and BDC (0.25 mmol) were dispersed in a mixed solution of 30 mL DMF and 10 mL DI water. Then the solution was heated at 60 °C for 12 h under continuous stirring. The obtained ultrathin NiBDC nanoribbons (utn-NiBDC) were obtained by centrifuging at 8000 rpm and washed twice with DMF and EtOH, respectively. Similarly, the thin NiBDC nanoribbons (tn-NiBDC) and thick NiBDC nanoribbons (tk-NiBDC) were synthesized by only changing the solvent ratio of DMF and water to 2:2 and 1:3, respectively. The Cl-substituted (Cl-) utn-NiBDC was synthesized by only changing the BDC into Cl-BDC.

Synthesis of Ni(OH)2 nanosheet

Typically, 1 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was dissolved in 40 mL DI water, marked as solution A. 2 mmol NaOH was also dissolved in 40 mL DI water, marked as solution B. Solution B was added dropwise into solution A under stirring at room temperature for 12 h. After centrifugation, the resulting Ni(OH)2 nanosheet was collected and washed three times with DI water. It is worth mentioning that the obtained sample was dispersed in DMF to prevent agglomeration.

Synthesis of ultrathin Ni(OH)2 nanosheet

The ultrathin Ni(OH)2 nanosheet was obtained by dissolving 3 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O into 40 mL EtOH in a 50 mL autoclave. The autoclave was heated at 150 °C for 12 h. Subsequently, the obtained samples were treated by 24-h ultrasound in an ethanol solution. The ultrathin Ni(OH)2 nanosheet (utn-Ni(OH)2) was obtained by centrifuging at 9000 rpm for 10 min and washed by water and EtOH four times.

Synthesis of bulk NiBDC

The bulk NiBDC was obtained by dissolving 0.25 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and 0.25 mmol BDC into a mixed solution of 30 mL DMF and 10 mL DI water. Subsequently, the solution was sealed in a 50 mL Teflon autoclave and heated at 120 °C for 12 h. The obtained bulk NiBDC (b-NiBDC) was obtained by centrifuging at 8000 rpm and washing twice with DMF and EtOH, respectively.

Characterization

Prior to the transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and atomic force microscopy (AFM) characterization, the ethanolic suspension of MOF was dropped onto the holey carbon-coated copper grids, Si/SiO2, and cleaned Si/SiO2 substrate, respectively. TEM images and corresponding energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mappings were performed on HITACHI HT-7700 or FEI Talos F200x. SEM images were taken on a field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss SUPRA 55). AFM measurements were conducted using a Bruker multimode-8 scanning probe microscope in tapping mode in the air. The crystal structures of the samples were examined by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) on Bruker D8 advanced diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å). Raman spectra were acquired on a HORIBA XploRA PLU with a 532 nm diode laser (power 40 mW). Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed by Netzsch Geraetebau Gmbh Tensor II (Germany) with a precision of 0.005 cm-1. Detailed chemical compositions were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) on an ESCALAB 250Xi photoelectron spectrometer using a monochromate Al Kα 150 W X-ray beam (1486.6 eV). All binding energies were referenced to the C 1 s peak (284.8 eV). UV-Vis absorption spectra were collected on a Shimadzu 2600 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was measured by BEUKER ELEXSYS-II (E 500, ν = 9.85 GHz). The Elementar Unicube elemental analyzer was used to perform the elemental analysis (EA) of Cl- substituted (Cl-) utn-NiBDC and its AT counterparts.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements

The X-ray absorption fine structure spectra (Ni K-edge) were collected at X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS) for Catalysis (XAFCA) beamline of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility, comprising a compact superconducting storage ring with 700 MeV electron energy and 4.5 Tesla magnetic field to produce synchrotron radiation with a characteristic photon energy of 1.47 keV and characteristic wavelength of 0.845 nm. The data were collected in fluorescence excitation mode using a Lytle detector. All samples were pelletized as disks of 13 mm diameter using graphite powder as a binder. The acquired EXAFS data were processed according to the standard procedures using the ATHENA module implemented in the IFEFFIT software packages55. The k3-weighted EXAFS spectra were obtained by subtracting the post-edge background from the overall absorption and then normalizing it to the edge-jump step. Subsequently, k3-weighted χ(k) data of Fe K-edge were Fourier transformed to real (R) space using a Hanning window (dk = 1.0 Å-1) to separate the EXAFS contributions from different coordination shells. To obtain the quantitative structural parameters around central atoms, the least-squares curve parameter fitting was performed using the ARTEMIS module of the IFEFFIT software packages. The following EXAFS equation was used:

where S02 is the amplitude reduction factor; Fj(k) is the effective curved-wave backscattering amplitude; Nj is the number of neighbors in the jth atomic shell; Rj is the distance between the X-ray absorbing central atom and the atoms in the jth atomic shell (backscatter); λ(k) is the mean free path in Å; ϕj(k) is the phase shift (including the phase shift for each shell and the total central atom phase shift); σj is the Debye-Waller parameter of the jth atomic shell (variation of distances around the average Rj)56. The functions Fj(k), λ(k), and ϕj(k) were calculated with the ab initio code FEFF8.057. For Wavelet Transform (WT) analysis, the χ(k) exported from Athena was imported into the Hama Fortran code58,59. The parameters were used as: R range, 1-4 Å, k range, 0-13 Å-1; k weight: 3; Morlet function with κ = 10, σ = 1 was used as the mother wavelet to provide the overall distribution.

Operando Raman measurements

A Lab Ram ARAMIS Raman spectrometer (HORIBA) with a 633 nm streamline laser excitation and the Cell with a quartz window (Shanghai Chuxi Industrial Co., Ltd.) was used for the operando Raman measurements. The obtained catalyst, Ag/AgCl, and Pt wire were employed as the working, reference, and counter electrode, respectively. The laser beams were focused on the sample through the quartz window to collect the Raman spectrum. The chronoamperometry method was employed to apply different voltages to the electrode with 100 mV intervals in the range of 0.8 to 0.2 V vs. RHE.

Operando ATR-FTIR measurements

Surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) with attenuated total reflection (ATR) was utilized to detect intermediates in the reaction. The measurements employed a Thermo Nicolet 8700 spectrometer with an MCT detector cooled by liquid nitrogen. Gold thin films (~60 nm) were deposited on Si prisms using the two-step wet method. The Si prism surfaces were polished with diamond suspension, ultrasonically cleaned, and treated with piranha solution. Gold deposition involved immersing prisms in a gold-plating solution (NaAuCl4·2H2O, Na2SO3, Na2S2O3·5H2O, NH4Cl, and hydrofluoric acid) at 60 °C. After a double gold deposition process, with the second lasting 90 s, the prisms were rinsed, dried, and coated with 30 μL of ink on the gold film working electrode. The ink-coated prisms were then assembled in a homemade spectro-electrochemical cell, with Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, introduced via a Luggin capillary, and a Pt mesh as the counter electrode. The chronoamperometry method was employed to apply different voltages to the electrode with 100 mV intervals in the range of 0.8 to 0.2 V vs. RHE. All spectra were presented as

where ES and ER representing the sample and reference spectra, respectively.

Electrochemical RRDE measurements

The catalytic ink was prepared by dispersing 4 mg of catalyst and 2 mg of carbon black (Vulcan XC72) in 980 μL of iso-propanol and 20 μL of 5 wt.% Nafion solution. After sonication for 2 h, 3.14 μL of catalyst suspension was drop-dried onto the disk electrode to form a uniform catalyst layer (the catalyst loading was 0.1 mg cm-2). The electrochemical measurements including linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), cyclic voltammetry (CV), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were determined in a standard four-electrode rotation ring disk electrode (RRDE) system (RRDE-3A, Japan ALS) controlled with a CHI or Donghua electrochemical workstation at room temperature (25 °C). The Pt ring (id = 5 mm, od = 7 mm) and glass carbon disk (d = 4 mm) RRDE loaded with catalyst, graphite electrode, and saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as the working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode, respectively. Before electrochemical measurements, the reference electrode was calibrated by immersing it in a saturated KCl standard solution and ensuring that the recorded potential corresponded to the theoretical value at room temperature. EIS tests were carried out at the open circuit potential of the electrode with a frequency range of 0.1 to 106 Hz and an amplitude of 5 mV, and ZView software was used for EIS data-fitting. All potentials were corrected to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) by ERHE = ESCE + 0.224 + 0.059 × pH. Unless specified, all curves were corrected by 100% iR-compensation as determined by EIS. All the electrochemical tests were performed in N2/O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH, which is immediately used after preparation. The pH value of 0.1 M KOH is determined as 13 ± 0.1 using a pH meter. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was established at a scan rate of 10 mV s-1 over a potential range of 0.2 V to 1.0 V vs. RHE. A potential of 1.2 V (vs. RHE) was applied to the ring of the working electrode during the entire testing process to detect the H2O2. The Tafel slope was calculated using E = b × log(j / j0), where E is the potential, b is the Tafel slope, j is the disk current density, and j0 is the exchange current density. The electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of the electrocatalysts is measured using a non-Faradaic potential window between 0.76 and 0.82 V vs. RHE, while the double-layer capacitance is determined by plotting the current density change at 0.8 V against the scan rate. The ECSA is calculated using ECSA = Cdl/Cs, with Cs being the specific capacitance of a flat electrode, set at 0.04 mF cm-2 for Ni(OH)260. Based on the current of both disc and ring electrodes, HO2- selectivity, electrons transferred number (n), and HO2- Faradaic efficiency (FE) of the catalysts on RRDE were calculated by the following equations:

where id is the disk current; ir is the ring current; N is the collection efficiency (0.424 after calibration).

Electrochemical H-type cell measurements

The selectivity and stability of the catalysts for H2O2 evolution were evaluated using an H-cell electrolytic device with three electrodes at room temperature (25 °C). The electrolyte was 15 mL O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH solution in both cathode and anode compartments, which was immediately used after preparation. 1 cm2 Nafion 117 membrane with a thickness of 183 μm was used as the membrane. The working electrode was a 1 cm2 carbon paper (TGP-H-060, Japan Toray) with 0.25 mg of catalyst pipetted. Graphite electrode and SCE were utilized as the counter and reference electrode, respectively. The electrolyte samples were taken, neutralized, and then titrated against Ce4+ (e.g., 2Ce4+ + H2O2 → 2Ce3+ +2H+ + O2). The amount of H2O2 generated can be calculated as twice the molar amount of Ce4+ consumed. To determine the concentration of Ce4+, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 319 nm (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, the corresponding HO2- FE can be calculated through the equations:

where C is the concentration of the H2O2; V is the electrolyte volume; F is the Faraday constant (96485 C mol-1), and Q is the passed charge amount.

Flow cell measurements

The flow cell electrolytic device was used for further examining the performance of H2O2 synthesis. The catalyst ink was sprayed onto the 1 cm2 GDL carbon paper (YLS-30T) as the working electrode (the areal mass loading was 0.25 mg cm−2) with Nickel foam as the counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. 1 cm2 dioxide materials sustainion membrane (X37-60 grade T) with a thickness of 50 μm was used as an anion exchange membrane. The electrolyte was used immediately after preparation. The electrolyte was 10 mL 0.1 M KOH in both cathode and anode compartments with a continuous circulation (5 mL min-1) by a peristaltic pump, which is immediately used after preparation. All the tests were under room temperature (25 °C). Simultaneously, a continuous flow of O2 or air was introduced into the cell (40 mL min-1). The H2O2 production amount in the electrolyte was quantified using the Ce4+ titration method. The H2O2 faradaic efficiency was calculated through the same method of H-type Cell measurement.

Theoretical computation

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to investigate the geometric and electronic structures of residual BDC ligand functionalized, oxygen vacancies induced, or pristine Ni(OH)2 and the mechanism for 2e- ORR by using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation package (VASP)61,62,63. The projected augmented wave (PAW) potential and generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of the spin-polarized Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional were employed to describe the electron-ion interaction and exchange-correlation energy, respectively64,65,66. The energy cutoff for the plane-wave expansion was set at 450 eV for optimizing calculations of atoms and cell optimization. The Hubbard U (DFT + U) corrections67,68 for 3 d transition metal were set using a U-J value of 6.45 eV for Ni atom69. The DFT-D3 empirical correction method was adopted to describe the van der Waals interactions between the adsorbed atoms and the support70. The construction of the surface model was based on the single crystal of Ni(OH)2 by constructing a 2 × 2 × 1 or 2 × 2 × 2 supercell. The primitive cell model of Ni(OH)2 was constructed with fully optimized atomic position, cell volume, and cell shape. The vacuum spacing in a direction perpendicular to the plane of the catalyst was at 15 Å. Then, an oxygen vacancy or a BDC ligand was added into the Ni(OH)2 to construct Ov-Ni(OH)2 and BDC-Ni(OH)2, respectively. The slab models were only optimized for the atomic positions. The equilibrium lattice constants were optimized with maximum stress on each atom within 0.05 eV Å-1 under the quasi-Newton algorithm71,72. The initial magnetic moments of Ni atoms were set to be +2 μB, while the spin-polarization effect was also considered. The self-consistent calculations applied a convergence energy threshold of 10-5 eV under the consideration of electronic relaxation to utilize the conjugate-gradient method73. After geometry optimization, the lattice constants of Ni(OH)2 supercell with ~100 atoms are a = 12.63 Å, b = 12.63 Å, and c = 31.25 Å, which should be sufficient. Thus, the Brillouin zone integration was performed using 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling for all samples74. The associated Gibbs free energies (ΔG) of the adsorbates for each electrochemical process are calculated as:

Where the value of ΔE, ΔEZPE, ΔS, and T denotes the changes of DFT energy, the zero-point energy, the entropy, and the temperature, respectively.

The calculated energy value of HO2- is from the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Specifically, the reactions and energy are calculated based on the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model. The half reaction \({O}_{2}+2\left({H}^{+}+{e}^{-}\right)={H}_{2}{O}_{2}\) is analyzed using the CHE model to obtain the energy of \({H}^{+}+{e}^{-}\), which is referenced to ½ H2. Referring to H2O and H2, the energy of diatomic oxygen molecules (O2) is obtained as 4.92 eV, and the energy of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is obtained as 3.67 eV. Thus, the energy of the deprotonated anion of H2O2 (HO2-) is calculated as 2.356 eV.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study have been included in the Manuscript and Supplementary Information. All the data are also available upon request from the corresponding authors. The data presented in the figures are provided as a Source Data file with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Xia, C., Xia, Y., Zhu, P., Fan, L. & Wang, H. Direct electrosynthesis of pure aqueous H2O2 solutions up to 20% by weight using a solid electrolyte. Science 366, 226 (2019).

Lu, Z. et al. High-efficiency oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide catalysed by oxidized carbon materials. Nat. Catal. 1, 156 (2018).

Shen, W. et al. Fullerene-derived boron-doped defective nanocarbon for highly selective H2O2 electrosynthesis. Nano Res. 17, 1217 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Scalable neutral H2O2 electrosynthesis by platinum diphosphide nanocrystals by regulating oxygen reduction reaction pathways. Nat. Commun. 11, 3928 (2020).

Xu, Y. et al. Oxygen doping and hollow structure-mediated effects to enable rapid electron transfer during photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. Sci. China Mater. 67, 153 (2024).

Luo, E. et al. Selective oxygen electroreduction to hydrogen peroxide in acidic media: The superiority of single-atom catalysts. Nano Res. 17, 4668 (2024).

Sun, Y., Han, L. & Strasser, P. A comparative perspective of electrochemical and photochemical approaches for catalytic H2O2 production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 6605 (2020).

Wu, Y., Paul, C. E. & Hollmann, F. Mirror, mirror on the wall, which is the greenest of them all? A critical comparison of chemo- and biocatalytic oxyfunctionalisation reactions. Green. Carbon 1, 227 (2023).

Lee, B.-H. et al. Supramolecular tuning of supported metal phthalocyanine catalysts for hydrogen peroxide electrosynthesis. Nat. Catal. 6, 234 (2023).

Jung, E. et al. Atomic-level tuning of Co–N–C catalyst for high-performance electrochemical H2O2 production. Nat. Mater. 19, 436 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. High-efficiency oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by nickel single-atom catalysts with tetradentate N2O2 coordination in a three-phase flow cell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13057 (2020).

Perry, S. C. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and oxygen. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 442 (2019).

Ho, M. C., Ong, V. Z. & Wu, T. Y. Potential use of alkaline hydrogen peroxide in lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment and valorization – A review. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 112, 75 (2019).

Costa, S., Rugiero, I., Larenas Uria, C., Pedrini, P. & Tamburini, E. Lignin degradation efficiency of chemical pre-treatments on banana rachis destined to bioethanol production. Biomolecules 8, 141 (2018).

Clark, J. H. Textile waste – an opportunity as well as a threat. Green. Carbon 1, 146 (2023).

Furukawa, H., Cordova, K. E., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 341, 1230444 (2013).

Cai, G., Yan, P., Zhang, L., Zhou, H.-C. & Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 121, 12278 (2021).

Zhao, S. et al. Ultrathin metal–organic framework nanosheets for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nat. Energy 1, 16184 (2016).

Zhong, H. et al. A phthalocyanine-based layered two-dimensional conjugated metal–organic framework as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 10677 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Pivotal role of reversible NiO6 geometric conversion in oxygen evolution. Nature 611, 702 (2022).

Zhou, G. et al. Spin-state reconfiguration induced by alternating magnetic field for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 12, 4827 (2021).

Tian, J. et al. Electric-field assisted in situ hydrolysis of bulk metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) into ultrathin metal oxyhydroxide nanosheets for efficient oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13101 (2020).

Zhao, S. et al. Structural transformation of highly active metal–organic framework electrocatalysts during the oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Energy 5, 881 (2020).

Pérez-Gallent, E., Marcandalli, G., Figueiredo, M. C., Calle-Vallejo, F. & Koper, M. T. M. Structure- and potential-dependent cation effects on CO reduction at copper single-crystal electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16412 (2017).

Burtch, N. C., Jasuja, H. & Walton, K. S. Water stability and adsorption in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 114, 10575 (2014).

Zheng, W. & Lee, L. Y. S. Metal–organic frameworks for electrocatalysis: catalyst or precatalyst? ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2838 (2021).

Yu, Z. et al. Research progress of amorphous catalysts in the field of electrocatalysis. Microstructures 4, 2024022 (2024).

Huang, L. et al. Self-dissociation-assembly of ultrathin metal-organic framework nanosheet arrays for efficient oxygen evolution. Nano Energy 68, 104296 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Topotactically transformed polygonal mesopores on ternary layered double hydroxides exposing under-coordinated metal centers for accelerated water dissociation. Adv. Mater. 32, 2006784 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Advances in understanding the electrocatalytic reconstruction chemistry of coordination compounds. Small 17, 2100629 (2021).

Vij, V. et al. Nickel-based electrocatalysts for energy-related applications: oxygen reduction, oxygen evolution, and hydrogen evolution reactions. ACS Catal. 7, 7196 (2017).

Wang, B. et al. Ultra-thin metal-organic framework nanoribbons. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 46 (2020).

Mesbah, A. et al. From hydrated Ni3(OH)2(C8H4O4)2(H2O)4 to anhydrous Ni2(OH)2(C8H4O4): impact of structural transformations on magnetic properties. Inorg. Chem. 53, 872 (2014).

Liu, M. et al. Self-nanocavity-confined halogen anions boosting the high selectivity of the two-electron oxygen reduction pathway over Ni-based MOFs. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 8706 (2021).

Li, R. et al. Short-range order in amorphous nickel oxide nanosheets enables selective and efficient electrochemical hydrogen peroxide production. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100788 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. 2D Hybrid of Ni-LDH chips on carbon nanosheets as cathode of zinc–air battery for electrocatalytic conversion of O2 into H2O2. ChemSusChem 13, 1496 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. An efficient interfacial synthesis of two-dimensional metal–organic framework nanosheets for electrochemical hydrogen peroxide production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11190 (2021).

Su, X. et al. Operando spectroscopic identification of active sites in NiFe prussian blue analogues as electrocatalysts: activation of oxygen atoms for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11286 (2018).

Xiao, X. et al. A general approach to cobalt-based homobimetallic phosphide ultrathin nanosheets for highly efficient oxygen evolution in alkaline media. Energy Environ., Sci. 10, 893 (2017).

Li, L. et al. Compensating electronic effect enables fast site-to-site electron transfer over ultrathin RuMn nanosheet branches toward highly electroactive and stable water splitting. Adv. Mater. 33, 2105308 (2021).

Duan, J., Chen, S. & Zhao, C. Ultrathin metal-organic framework array for efficient electrocatalytic water splitting. Nat. Commun. 8, 15341 (2017).

Rajendran, S. et al. Influence of mesoporous defect induced mixed-valent NiO (Ni2+/Ni3+)-TiO2 nanocomposite for non-enzymatic glucose biosensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 264, 27 (2018).

Aghazadeh, M. & Rad, H. F. In situ growth of Ni(OH)2-porous nitrogen-doped graphene composite onto Ni foam support as advanced electrochemical supercapacitors materials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. 33, 11038 (2022).

Cheng, F. et al. Accelerated water activation and stabilized metal-organic framework via constructing triangular active-regions for ampere-level current density hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 13, 6486 (2022).

Li, F.-L. et al. Large-scale, bottom-up synthesis of binary metal–organic framework nanosheets for efficient water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 7051 (2019).

Sanson, A. EXAFS spectroscopy: a powerful tool for the study of local vibrational dynamics. Microstructures 1, 2021004 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. Boosting ORR performance by single atomic divacancy Zn–N3C–C8 sites on ultrathin N-doped carbon nanosheets. Chem. Catal. 2, 836 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. Atomically dispersed iron regulating electronic structure of iron atom clusters for electrocatalytic H2O2 production and biomass upgrading. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202314414 (2023).

Jiang, K. et al. Highly selective oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide on transition metal single atom coordination. Nat. Commun. 10, 3997 (2019).

Dong, J.-C. et al. In situ Raman spectroscopic evidence for oxygen reduction reaction intermediates at platinum single-crystal surfaces. Nat. Energy 4, 60 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Promoting electrochemical CO2 reduction via boosting activation of adsorbed intermediates on iron single-atom catalyst. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110174 (2022).

Nayak, S., McPherson, I. J. & Vincent, K. A. Adsorbed intermediates in oxygen reduction on platinum nanoparticles observed by in situ IR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12855 (2018).

Singh, R. K., Devivaraprasad, R., Kar, T., Chakraborty, A. & Neergat, M. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in a rotating disk electrode configuration: effect of ionomer content and carbon-support. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, F489 (2015).

Siahrostami, S. et al. Enabling direct H2O2 production through rational electrocatalyst design. Nat. Mater. 12, 1137 (2013).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537 (2005).

Fei, H. et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of MN4C4 single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 1, 63 (2018).

Ankudinov, A. L., Ravel, B., Rehr, J. J. & Conradson, S. D. Real-space multiple-scattering calculation and interpretation of X-ray-absorption near-edge structure. Phys. Rev. B 58, 7565 (1998).

Funke, H., Scheinost, A. C. & Chukalina, M. Wavelet analysis of extended X-ray absorption fine structure data. Phys. Rev. B 71, 094110 (2005).

Funke, H., Chukalina, M. & Scheinost, A. C. A new FEFF-based wavelet for EXAFS data analysis. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 14, 426 (2007).

McCrory, C. C. L., Jung, S., Peters, J. C. & Jaramillo, T. F. Benchmarking heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16977 (2013).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505 (1998).

Cococcioni, M. & de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+U method. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035105 (2005).

Zhao, W. et al. Water Dissociative Adsorption on NiO(111): Energetics and structure of the hydroxylated surface. ACS Catal. 6, 7377 (2016).

Schouten, K. J. P., van der Niet, M. J. T. C. & Koper, M. T. M. Impedance spectroscopy of H and OH adsorption on stepped single-crystal platinum electrodes in alkaline and acidic media. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 15217 (2010).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616 (1989).

Pulay, P. Convergence acceleration of iterative sequences. The case of SCF iteration. Chem. Phys. Lett. 73, 393 (1980).

Payne, M. C., Teter, M. P., Allan, D. C., Arias, T. A. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Iterative minimization techniques for ab initio total-energy calculations: molecular dynamics and conjugate gradients. Rev. Mod. Phys. 64, 1045 (1992).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Z240027; J.F.L.), the Hong Kong UGC-TRS Award (T23-713/22-R; Z.X.G.), the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF 2021-152; Z.X.G.), the RGC-EU Collaborative Programme initiative (E-HKU704/19; Z.X.G.), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B0101370003; Z.X.G.), and the “Hong Kong Quantum AI Lab Ltd” funded by the AIR@InnoHK and launched by the Innovation and Technology Commission (ITC). The authors thank the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) for XAS measurement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y.Z. and W.B.W. contributed equally to this work. J.F.L. and T.Y.Z. conceived the project. J.F.L. and Z.X.G. supervised the project. T.Y.Z. and W.B.W. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. W.X.L. assisted with the Cl content analysis. T.Y.Z. Z.X.G. and J.F.L. prepared the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and assisted during the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Wang, W., Liu, W. et al. Residual ligand-functionalized ultrathin Ni(OH)2 via reconstruction for high-rate HO2− electrosynthesis. Nat Commun 16, 5240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60467-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60467-0