Abstract

Mode coupling is a fundamental aspect of wave propagation and is therefore intrinsic to many branches of physics. We consider the resonant coupling, typically caused by weak perturbations, between solitons—high-intensity nonlinear pulses—and low-amplitude linear waves. These resonances, which are quite common in nature, enable the two modes to exchange energy, contradicting the usual perception of solitons as pulses that propagate without changing shape. The mathematical analysis required to characterize this effect is challenging and was completed only relatively recently, even though its roots date back to the work of G. G. Stokes in the mid-19th century. This analysis predicts that the phenomenon is universal, occurring for many different types of waves irrespective of the nature of the soliton, the linear mode, or the coupling mechanism. However, despite its broad significance, these predictions were never systematically verified experimentally. Here, we validate these predictions in an optics context using a mode-locked fibre laser. We confirm that the coupling is universal and approximately satisfies a general scaling law. By validating long-standing theoretical predictions, we confirm the physical and mathematical relationships of previous experimental observations across a wide variety of perturbed nonlinear waves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solitons—or solitary waves—are generally understood to be wave packets that propagate without changing shape by balancing the effects of dispersion and nonlinearity. Nonlinear wave dynamics in the presence of dispersion is ubiquitous, and as such, solitons are a general phenomenon that can be found in water waves1,2, planetary atmospheres3, plasmas4, Bose-Einstein condensates5, field theory6, and in optics7. Optical geometries are particularly well-suited for studying solitons since losses and other undesirable perturbations are weak8.

However, the description above is an idealization in that the influence of phenomena other than the dominant nonlinear and dispersive effects are neglected. As Boyd remarked9, “the classical solitary wave is a fairy tale written in the symbols of calculus;” since nature is rarely ideal, the ideal soliton can only approximate reality. Solitons, for example, may be coupled to linear waves by weak perturbations, causing them to radiate energy. Well-known examples of such nonlocal solitary waves include tidal flows10,11, isolated long-lived vortices in fluids such as the Gulf Stream rings12,13,14, solitons in optical fibers15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, and the Morning Glory cloud structure25,26,27—which are all known to radiate. The Morning Glory, specifically, occurs predominantly in Australia and can be modeled as a solitary wave balancing nonlinearity and dispersion as it propagates over several 100’s of km28,29. It is also known to lose energy through radiation to upper sections of the atmosphere. The energy is, in turn, replenished by the sea breeze in the lower atmosphere, allowing the structure to continue propagating26.

These radiative losses are as universal as the solitons from which they originate: the radiation arises from a resonance between weak linear waves and the soliton which has a larger amplitude9,16. At the resonant frequencies, energy is shared between the two modes, and a soliton therefore inevitably radiates, losing energy.

The resonant radiation is generally weak, however, in many cases, neither the soliton’s radiative decay rate nor the radiation amplitude can be calculated by standard perturbation approaches9. They necessitate specialized mathematical techniques which began with the work of G. G. Stokes in the mid-19th century in his study of what is now known as the Stokes phenomenon. The development was finalized only towards the end of the 20th century, with contributions from Berry, Grimshaw, Joshi, and many others11,30,31,32,33.

Their work, much of which was based on a perturbed Korteweg–de Vries equation1, has led to firm predictions of the radiation amplitude31,32,33. Crucially, they show that the radiative losses are a universal phenomenon, in that they occur in a wide variety of physical systems, are caused by similar underlying effects, and can be mathematically described in a way that is agnostic to the particular embodiment. Under very general conditions—essentially when the energy leakage is associated with the soliton’s spectral tails—the amplitude A of the radiation follows the scaling relation

apart from a prefactor with magnitude of order unity. Here, χ is a positive real number representing the physical system, and ϵ is a dimensionless measure of the perturbation magnitude. We note as an aside that since the amplitude is exponentially small in ϵ, this result could not have been derived using standard perturbative treatments like a Taylor series expansion34.

Even though naturally occurring phenomena such as the Morning Glory and Gulf Stream rings are well-studied, they do not lend themselves to systematic changes in the parameters. Even in laboratory experiments18,19,20,21,22,23,24,35,36, the universality has not been exploited or discussed in detail—the universal aspects of the Stokes phenomenon and of Eq. (1) have thus escaped rigorous and systematic experimental testing until now.

Here, we provide a thorough experimental analysis and verification of the Stokes phenomenon in an optics context. We utilize a fiber laser in which the effective dispersion can be freely adjusted and the radiative losses are compensated by the gain inside the cavity37. We experimentally demonstrate the universality of the coupled radiation in three ways: we show that (i) the output of the laser satisfies the ubiquitous nonlinear Schrödinger equation and its generalizations; (ii) the same physical phenomenon occurs for differing types of solitons and perturbations; and (iii) that our results are approximately consistent with Eq. (1). Thus, our aim is not to derive novel mathematical results, but rather, it is to experimentally verify existing theory as applied to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, and, particularly, to its high-order generalizations. Further, since the mode coupling of high-order nonlinear Schrödinger equations has not previously been considered, we explicitly show how the universal results do apply to these equations.

The objects we are studying here differ from dissipative solitons, which not only require a balance between dispersion and nonlinearity, but also between gain and loss38. Whereas for dissipative solitons the loss is typically strong and broadband, our interest is in systems with a sharp resonance in the spectral tails, leading to weak and spectrally narrow features. The resulting solitons are sometimes referred to as nanopterons9. For dissipative solitons, the gain and loss are sufficiently strong to play an important role in determining the soliton shape and amplitude. However, for nanopterons, the main pulse shape is determined by the balancing of dispersion and nonlinearity, with the losses manifesting only as oscillations in the temporal tail(s).

Results

Resonant coupling

A conceptual illustration of the physical phenomena driving our experiments—particularly the properties of the two relevant modes—is given in Fig. 1. The orange curves in Fig. 1a show linear dispersion relations in a frame that moves at the group velocity associated with a reference frequency ω016. Dispersion relations give the propagation constant (or wavenumber) β for each frequency ω for low-intensity waves. Their slope ∂β/∂ω represents the inverse group velocity \({v}_{g}^{-1}\) in the moving frame. Ideal solitons require the dispersion relation to be concave down, so low frequencies—which have a positive slope—travel slower than the frame, whereas high frequencies—with a negative slope—move faster. A parabola, shown by the dotted curve in Fig. 1a, is merely the simplest realization of such a curve.

a Soliton (blue) and linear (orange) dispersion relations relate the propagation constant (prop. const.) to frequency, centered at ω0. The dispersion relation perturbed by β3 > 0 intersects the soliton line at ωr, while the ideal one does not. b Theoretical spectra. c Theoretical electric field envelopes.

In contrast, the propagation of high-intensity waves—which additionally are subject to nonlinear effects—is governed by the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, which has soliton solutions7. In Fig. 1a, these are represented by the blue horizontal line βsol, which is offset from the linear dispersion relation by an amount μ > 0 due to the effect of the nonlinearity. Since the line is horizontal, the pulse moves at the speed of the frame16. The dotted curves in Fig. 1b, c show the associated soliton spectrum and temporal intensity envelope respectively. The spectral peak of the soliton in Fig. 1b occurs at the frequency nearest to the ideal dispersion relation as given by the gray vertical dashed line16. The fact that the soliton line does not intersect the dispersion relation indicates that it does not lose energy to linear waves and propagates unperturbed16. The electric field decays exponentially to zero as the time t → ±∞, and is therefore temporally localized, as seen by the dotted curve in Fig. 1c.

When a small positive cubic term is added to the dispersion relation (see Fig. 1a), it intersects the soliton line at frequency ωr, marked by the black vertical dashed line in Figure 1a. This means that the two modes—the soliton and the low-intensity linear waves—are resonantly coupled at this frequency. As a consequence, the soliton spectrum in Fig. 1b (solid curve) exhibits a novel feature at ωr caused by energy radiating away from the soliton in the form of linear waves. This radiation manifests temporally as low-amplitude oscillations, so the soliton is no longer localized in time. The radiation lags the main pulse, as shown in Fig. 1c (solid curve). This is consistent with the positive slope of the dispersion relation at ωr, which indicates that the linear waves travel slower than the soliton.

The existence of the oscillations in Fig. 1c and the underlying concepts are universal and have been studied in various physical systems for over a century34. In optics specifically, the emission of dispersive waves by optical solitons due to cubic dispersion has been reported theoretically15,16,17,39,40,41,42 and experimentally18,19,20,21,22,23,24. However, the dispersion was almost always determined by the waveguide material and geometry, and could not be dynamically adjusted, limiting systematic explorations of these phenomena.

In our experiments, we can effectively generate arbitrary dispersion relations using a passively mode-locked fiber laser that incorporates an intracavity pulse shaper37,43,44,45. Details can be found in Supplementary Section 1. Much like how the energy of the Morning Glory is replenished by wind in the lower atmosphere26, light propagation here is dominated by nonlinearity and dispersion, while the laser itself merely restores the energy lost upon propagation37,43. In this section, we apply dispersion relations of the form

with reference frequency ω0 chosen conveniently in the operating spectrum of the laser around the wavelength λ = 1560 nm. For the results below, we set the net quadratic dispersion β2 = −1.0 ps2 m−1 and consider three combinations of β3 and β4. We retrieve the complete temporal and spectral properties of the laser pulses using a frequency-resolved electrical gating (FREG) technique37,43,46.

Our measurements are shown in Fig. 2. The left column corresponds to the case discussed in Fig. 1 (β3 > 0 and β4 = 0). The applied net linear dispersion (orange) and spectrum (blue) are shown in Fig. 2a. The spectrum exhibits a sharp peak at ωr = 0.89 rad ps−1 marked by the vertical dashed line. The low-frequency feature corresponds to a Kelly sideband, which can be ignored37,47. The associated spectrogram is shown in Fig. 2b. The blue streak in the top right represents the resonantly coupled linear waves, which, as argued above, trail the soliton. Finally, Fig. 2c shows the retrieved real part of the electric field (teal) and temporal phase φ(t) (yellow). Here, like in Fig. 1c, we observe low-amplitude oscillations lagging the main pulse. The oscillation period of 7.09 ps corresponds to a frequency of 0.89 rad ps−1, in excellent agreement with the spectrum in Fig. 2a. Figure 2c also shows that the associated phase decreases approximately linearly with time t. Since ω = −dφ/dt, this confirms that the radiation has a higher frequency than the soliton, also consistent with Fig. 2a.

Column 1, results for β2 = −1.0 ps2 m−1, β3 = 4.5 ps3 m−1. a Applied linear (orange) dispersion relation with measured output spectrum (blue). b Measured spectrogram. c Retrieved real electric field (teal) and temporal phase (yellow). Columns 2 (d–f) and 3 (g–i) are similar, but for the opposite-signed odd-order β3 = −4.5 ps3 m−1, and an even-order β4 = 22.8 ps4 m−1 perturbation respectively.

The middle column in Fig. 2 shows a similar set of measurements, but instead for β3 < 0. This causes ωr to shift to frequencies below that of the soliton, as seen in Fig. 2d. At ωr, the slope of the dispersion relation is now negative, so the radiation leads the soliton. This is confirmed by the measured spectrogram and retrieved electric field, shown in Fig. 2e and 2f, respectively. The oscillation period of 7.18 ps gives a frequency of 0.88 rad ps−1, agreeing well with Fig. 2d in which ∣ωr∣ = 0.86 rad ps−1. As expected from the signs of ωr and \({v}_{g}^{-1}\), these results are mirrored compared to the case for β3 > 0.

Finally, we choose β3 = 0 and instead take β4 > 0 to be the leading perturbation, as seen in Fig. 2g. Since the dispersion profile is now even, it intersects the soliton line at two frequencies ωr = ±0.75 rad ps−1. The measured spectrum correspondingly exhibits a feature at both frequencies with equal and opposite group velocities. This manifests in the spectrogram in Fig. 2h as two tails on diagonally opposite sides. Likewise, the recovered temporal profiles in Fig. 2i shows that the soliton emits two waves—one leading and the other trailing the main pulse. Their periods of 8.45 and 8.22 ps, corresponding to 0.74 and 0.76 rad ps−1 respectively, are once again consistent with the spectrum in Fig. 2g.

These results demonstrate our ability to control the dispersion precisely, allowing us to generate solitons that are resonantly coupled to linear waves in various ways. Figure 2c, f, i are reminiscent of measurements in other optical systems22,23,24, as well as in completely different physical settings such as water waves11, mechanical waves in elastic woodpile structures35, and charge waves in electrical lattices36. This confirms the universal behavior that ensues when a nonlinear excitation resonantly couples to linear waves. In the next section, we exploit our unique ability to tune the nature and parameters of the dispersion relation to explore this universal behavior in more detail.

Universality

If the radiative phenomena discussed in the “Resonant coupling” section are truly universal, then they must generalize to many types of solitons and many types of perturbations. To explore this claim, we perturb pure-quartic solitons (PQSs). PQSs were experimentally demonstrated only recently37,48, and differ significantly from the conventional nonlinear Schrödinger solitons considered in the “Resonant coupling” section. They satisfy different equations, have different shapes, and obey different relations between energy and pulse duration49. These pulses arise when β2 = 0 and β3 = 0, whereas β4 < 0, which leads to a concave down function, as required. In this section, we consider perturbed dispersion relations of the form

for even integers n ≥ 6. Our choice of even-order perturbations preserves spectral symmetry. The nonlinear Schrödinger equation describes media with quadratic dispersion (as in “Resonant Coupling”). This equation is integrable and its solutions are therefore referred to as solitons. In contrast, in the presence of pure quartic dispersion, represented by the first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (3), the associated generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation is not integrable50. Its stationary solutions can therefore, strictly speaking, not be referred to as solitons but are rather solitary waves. Below, we nonetheless use the term soliton since this nomenclature is now widespread in the physics literature.

Perturbation-agnostic behavior

We first provide qualitative evidence supporting the universality in Fig. 3. We generate three PQSs and compare the effects of postive sextic (n = 6), octic (n = 8) and decic (n = 10) dispersion, while β4 is fixed to ensure the main pulses have similar properties. The perturbation values were adjusted so that the corresponding dispersion relations (orange; solid, dashed, dotted respectively) intersect the soliton line (blue) at the same frequency in Fig. 3a. These three scenarios are qualitatively the same, and correspond to the same χ and the same effective perturbation strength ϵ in Eq. (1).

The associated measured spectra are shown in Fig. 3b. As predicted, all three nanopterons appear near-identical. These similarities extend to the recovered temporal electric fields in Fig. 3c, which, as expected, show oscillations with the same frequency on both sides of the main pulse. We note in addition that the oscillations have the same phase, and that the radiation amplitudes are approximately equal. Both of these observations are key predictions of the mathematical analysis leading to Eq. (1) when applied to systems with even dispersion relations51,52. Indeed, since all three perturbations correspond to the same ϵ with fixed χ, the radiation amplitudes differ at most by a factor of order unity, as in Fig. 3c. Thus, these results demonstrate that the mode coupling is agnostic to the particular perturbation that causes it. The derivation of the result that the response of quartic solitons does not depend on the details of the coupling is discussed in Supplementary Section 4.

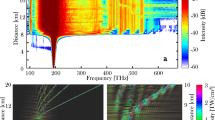

Systematic perturbation control

We now consider PQSs with fixed β4 as before, but perturbed by sextic dispersion β6 > 0 of varying strength. The perturbation strength ϵ is unitless (see “Methods” for the normalization scheme) and increases monotonically with β6. Figure 4a gives selected spectral measurements with β6 increasing from top to bottom. Again, since β4 is unchanged, the main soliton spectrum does not vary appreciably with β6. Instead, only the radiation changes significantly, shifting inwards to ω = ω0 and growing as the perturbation ϵ increases. While this is qualitatively consistent with Eq. (1) and the resonance argument from the “Resonant coupling” section, we investigate the quantitative agreement here.

a Measured spectra for fixed β4/4! = −40 ps4 km−1 but increasing β6 (and ϵ) from top to bottom. b Measured (circles), theoretical (solid) and asymptotic (dashed) radiation frequencies against inverse perturbation strength 1/ϵ. c Estimated logarithm of radiation amplitudes \(\ln A\) versus 1/ϵ for both the ωr < ω0 (purple triangles) and ωr > ω0 (green triangles) resonances. A is normalized to A0—the amplitude at an arbitrarily selected data point. Linear fits (dashed) are shown with respective slopes of −1.73 (R2 = 0.98) and −1.75 (R2 = 0.99). Results in (b, c) are all non-dimensionalized and normalized, such that χ ≈ 2.75 is expected when ϵ ≪ 1.

The radiation frequencies, as measured from the spectra and appropriately normalized (see “Methods”), are plotted against 1/ϵ in Fig. 4b (circles). The solid curve shows the theoretical prediction using the resonance argument. In the asymptotic limit ϵ → 0, the normalized frequencies follow the dashed line 1/ϵ (derived in Supplementary Sections 3 and 4). The experiments and theory agree well as each point deviates from the solid curve by under 5%.

Finally, we experimentally test Eq. (1). While the mathematical derivation of this scaling law is challenging30,31,32, it is outlined in Supplementary Section 4. Heuristically though, it expresses that the radiation amplitude A is proportional to the soliton’s spectral amplitude Asol at the resonant frequency ωr16. Soliton spectral amplitudes typically decay exponentially49, so that, deep in the wings, the amplitude is \({A}_{{{{\rm{sol}}}}}\propto \exp (-\chi | \omega -{\omega }_{0}| )\), where χ is the decay rate. Since from Fig. 4b the normalized resonant frequency asymptotically traces 1/ϵ, we find that \({A}_{{{{\rm{sol}}}}}\propto \exp (-\chi /\epsilon )\), mirroring Eq. (1). For the PQS using our normalization scheme, χ ≈ 2.75 (see Supplementary Sections 3 and 4). Then, Eq. (1) predicts that \(\ln (A)\) versus 1/ϵ is a straight line with slope −χ9,15. We estimate the radiation amplitudes from the shape and the height of the resonant features in Fig. 4a; details are given in Supplementary Section 5. The results for both the ωr < ω0 (purple triangles) and ωr > ω0 (green triangles) resonances are shown in Fig. 4c, confirming the straight line. We estimate the magnitude of the respective slopes to be 1.73 and 1.75, differing somewhat from the expected χ ≈ 2.75. We obtained similar results for different values of β4, further supporting the universality (see Supplementary Section 7).

The discrepancy of ~35% between the measured and expected slopes in Fig. 4c is consistent with numerical laser simulations (see Supplementary Section 8)37. It is thus likely due to intrinsic constraints of the experiment. We attribute this discrepancy to the relatively large values of ϵ, which are restricted to 0.36 ≲ ϵ ≲ 0.52 by the need for stable laser operation. At these values, the perturbation is not sufficiently small for quantitative agreement with the asymptotic limit (i.e., where Eq. (1) with χ ≈ 2.75 strictly applies). This is illustrated by the solid- and dashed-orange curves in Fig. 1a, which show that the presence of the perturbation can distort the dispersion relation significantly. For ω > ω0, the dispersion relation initially flattens, so the effective ∣β2∣ is locally weaker. Heuristically, for the dispersion to then remain balanced with the nonlinearity, the soliton spectrum needs to broaden so as to capture a larger portion of the dispersion relation, and thus the spectral decay rate drops. Since the χ parameter effectively corresponds to the asymptotic spectral decay rate of the soliton, the measured value of χ is smaller than that expected as ϵ → 0, consistent with the results in Fig. 4. For the relatively large values of ϵ where we operate, this effect is quite substantial. This argument is corroborated by Fig. 4b, which demonstrates that the agreement between theory and experiment improves as ϵ decreases.

The variety of results in Figs. 3 and 4 and the overall good agreement with theoretical predictions nonetheless provide concrete experimental evidence for the universal behavior of soliton radiation. Our ability to systematically vary the physical parameters finally enables a confirmation of the associated mathematical formalism that has been developed over decades.

Discussion

The results we have presented are only made possible by the exquisite control over the net-cavity dispersion afforded by our fiber laser37. Even though others have experimentally observed the low-amplitude temporal oscillations of nanopterons, their systems lacked systematic control over all relevant parameters11,20,23,35,36, or they could not demonstrate the universality of the radiative process21,22,24. Some of these studies consisted of discrete elements35,36, making it difficult to establish the link to standard continuous nonlinear wave equations.

Our experiments required measurements of weak features in the spectral tails of solitons. These results are therefore sensitive to noise and other small undesired perturbations. Despite being based on a conservative generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation, our theoretical approach is sufficient in all cases we considered37,43. It is in very good agreement with experimental results, as seen in Fig. 4, and numerical simulations of the laser cavity based on a realistic iterative map model37,53 (see Supplementary Section 8).

In light of this, the agreement between our results and the theoretical expectations in Fig. 4 is remarkable. The consistency with an exponential scaling law Eq. (1) is particularly noteworthy.

We remark that our setup may also suit the study of micropterons. These objects are similar to nanopterons in that they consist of a nonlinear structure losing energy by coupling to a linear mode, but different because the resonance occurs at low frequencies, close to the spectral peak of the soliton. In fact, the Morning Glory is an example of a micropteron9. Such studies can form the subject of possible future research.

Finally, we stress that while our experiments were carried out using optical waves, our results are universal. Our findings pertain to diverse branches of physics described generically by nonlinear wave equations, irrespective of the exact details of both the soliton and the perturbation. Furthermore, it validates the associated mathematical framework that has matured over decades but was difficult to test experimentally. Yet, despite its long history, novel applications of this phenomenon continue to be developed24.

Methods

Normalized quantities

Our theoretical analysis was based on the one-dimensional generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation,

where ψ = ψ(t, z) is the electric field envelope, z is the (spatial) propagation coordinate, t is the (temporal) transverse coordinate comoving with the pulse, i is the imaginary unit, and γ > 0 is the nonlinear parameter.

From the “Universality” section, we were exclusively interested in PQSs perturbed by higher even-order dispersion, which simplified Eq. (4) in that the only non-zero dispersion coefficients were β4 and βk for k = 6, 8, or 10. We used this alongside the standard ansatz for fundamental stationary solitons ψ = u(t)eiμz to reduce Eq. (4) to

We then normalized Eq. (5) into the form

in which all quantities in Eq. (6) were nondimensionalized, and the perturbation magnitude ϵ is explicitly included. Additionally, Eq. (6) was written such that in the limit where ϵ → 0, the normalized resonant frequency approaches 1/ϵ asymptotically. The necessary transformations are

which apply for all PQSs, perturbed by any positive even-order dispersion (i.e., βk > 0, for even k ≥ 6). This scheme and its importance is fully contextualized in Supplementary Sections 3 and 4.

Radiation amplitude estimation

The square roots of the spectra in Fig. 4a were taken to obtain the spectral amplitudes. The corresponding radiative features in the spectral amplitude profiles were observed to be bell-shaped and fit particularly well to a hyperbolic secant

for fit parameters height h, width w, frequency offset ωr, local slope m, and vertical offset b. Note that the background solitons were approximated locally by a straight line mω + b since the resonances were so narrow.

The spectral amplitudes of the radiative features were taken to be h, which effectively deducts the contribution from the spectral amplitude of the main pulse. The values of h were normalized thereafter. The feature widths w were near-identical across all of our measurements, so we assumed that the radiation’s temporal profile had approximately the same shape for all the different perturbations which were tested for a fixed β4. Therefore, the scaling results relevant for Eq. (1) could be measured from the spectra without converting to the time domain. A complete justification of this method is outlined in Supplementary Section 5.

Data availability

The source data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study including the supplementary material are available in the Zenodo database with the identifier https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1538792854. Any additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The code supporting the plots within this paper and other findings of this study including the supplementary material are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Korteweg, D. J. & de Vries, G. On the change of form of long waves advancing in a rectangular canal, and on a new type of long stationary waves. London Edinburgh Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 39, 422–443 (1895).

Gardner, C. S., Greene, J. M., Kruskal, M. D. & Miura, R. M. Method for solving the Korteweg-de Vries equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 19, 1095–1097 (1967).

Tsujimora, Y. N. Solitons in the atmosphere. J. Jpn. Soc. Fluid Mech. 14, 182–190 (1995).

Kono, M., Škorić, M.M. Solitons in plasmas. In: Nonlinear Physics of Plasmas 151–195 (Springer, 2010).

Burger, S. et al. Dark solitons in Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 5198–5201 (1999).

Weinberg, E. J. Classical Solutions in Quantum Field Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Kivshar, Y. S. & Agrawal, G. P. Optical Solitons: from Fibers to Photonic Crystals (Academic Press, 2003).

Blanco-Redondo, A., de Sterke, C. M., Xu, C., Wabnitz, S. & Turitsyn, S. K. The bright prospects of optical solitons after 50 years. Nat. Photonics 17, 937–942 (2023).

Boyd, J. P. Weakly Nonlocal Solitary Waves and Beyond-All-Orders Asymptotics (Springer, 1998).

Farmer, D. M. & Dungan Smith, J. Tidal interaction of stratified flow with a sill in Knight Inlet. Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr., A 27, 239–254 (1980).

Akylas, T. R. & Grimshaw, R. H. J. Solitary internal waves with oscillatory tails. J. Fluid Mech. 242, 279–298 (1992).

Mied, R. P. & Lindemann, G. J. The propagation and evolution of cyclonic Gulf Stream rings. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 9, 1183–1206 (1979).

McWilliams, J. C. & Flierl, G. R. On the evolution of isolated, nonlinear vortices. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 9, 1155–1182 (1979).

Flierl, G. R., Stern, M. E. & Whitehead, J. A. The physical significance of modons: laboratory experiments and general integral constraints. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 7, 233–263 (1983).

Wai, P. K. A., Chen, H. H. & Lee, Y. C. Radiations by “solitons” at the zero group-dispersion wavelength of single-mode optical fibers. Phys. Rev. A 41, 426–439 (1990).

Akhmediev, N. & Karlsson, M. Cherenkov radiation emitted by solitons in optical fibers. Phys. Rev. A 51, 2602–2607 (1995).

Zakharov, V. E. & Kuznetsov, E. A. Optical solitons and quasisolitons. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 86, 1035–1046 (1998).

Cristiani, I., Tediosi, R., Tartara, L. & Degiorgio, V. Dispersive wave generation by solitons in microstructured optical fibers. Opt. Express 12, 124–135 (2004).

Fuerbach, A., Steinvurzel, P., Bolger, J. A. & Eggleton, B. J. Nonlinear pulse propagation at zero dispersion wavelength in anti-resonant photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Express 13, 2977–2987 (2005).

Jang, J. K., Erkintalo, M., Murdoch, S. G. & Coen, S. Observation of dispersive wave emission by temporal cavity solitons. Opt. Lett. 39, 5503–5506 (2014).

Okawachi, Y. et al. Active tuning of dispersive waves in Kerr soliton combs. Opt. Lett. 47, 2234–2237 (2022).

Ji, Q.-X. et al. Engineered zero-dispersion microcombs using CMOS-ready photonics. Optica 10, 279–285 (2023).

Macnaughtan, M., Erkintalo, M., Coen, S., Murdoch, S. & Xu, Y. Temporal characteristics of stationary switching waves in a normal dispersion pulsed-pump fiber cavity. Opt. Lett. 48, 4097–4100 (2023).

Ji, Q.-X. et al. Dispersive-wave-agile optical frequency division. Nat. Photonics https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01667-4 (2025).

Crook, N.A. The formation of the Morning Glory. In: Lilly, D.K., Gal-Chen, T. (eds.) Mesoscale Meteorology—Theories, Observations and Models 349–353 (Springer, 1983).

Menhofer, A., Smith, R. K., Reeder, M. J. & Christie, D. R. "Morning-Glory” disturbances and the environment in which they propagate. J. Atmos. Sci. 54, 1712–1725 (1997).

El, G. A. & Hoefer, M. A. Dispersive shock waves and modulation theory. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenomena 333, 11–65 (2016).

Smith, R. K. Travelling waves and bores in the lower atmosphere: the ‘Morning Glory’ and related phenomena. Earth-Sci. Rev. 25, 267–290 (1988).

Rottman, J. W. & Einaudi, F. Solitary waves in the atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 2116–2136 (1993).

Berry, M. V. Stokes’ phenomenon; smoothing a Victorian discontinuity. Publ. Math. IHÉS 68, 211–221 (1988).

Grimshaw, R. H. J. & Joshi, N. Weakly nonlocal solitary waves in a singularly perturbed Korteweg–de Vries equation. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 55, 124–135 (1995).

Trinh, P. H. Exponential asymptotics and Stokes line smoothing for generalized solitary waves. In: Asymptotic Methods in Fluid Mechanics: Survey and Recent Advances 121–126 (Springer, 2010).

Joshi, N. & Lustri, C. J. Generalized solitary waves in a finite-difference Korteweg–de Vries equation. Stud. Appl. Math. 142, 359–384 (2019).

Boyd, J. P. The devil’s invention: asymptotic, superasymptotic and hyperasymptotic series. Acta Appl. Math. 56, 1–98 (1999).

Kim, E. et al. Highly nonlinear wave propagation in elastic woodpile periodic structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 118002 (2015).

Chen, X.-L., Abdoulkary, S., Kevrekidis, P. G. & English, L. Q. Resonant localized modes in electrical lattices with second-neighbor coupling. Phys. Rev. E 98, 052201 (2018).

Runge, A. F. J., Hudson, D. D., Tam, K. K. K., de Sterke, C. M. & Blanco-Redondo, A. The pure-quartic soliton laser. Nat. Photonics 14, 492–497 (2020).

Akhmediev, N., Ankiewicz, A. Dissipative Solitons: From Optics to Biology and Medicine (Springer, 2008).

Karpman, V. I. Radiation by solitons due to higher-order dispersion. Phys. Rev. E 47, 2073–2082 (1993).

Elgin, J. N., Brabec, T. & Kelly, S. M. J. A perturbative theory of soliton propagation in the presence of third order dispersion. Opt. Commun. 114, 321–328 (1995).

Dudley, J. M., Genty, G. & Coen, S. Supercontinuum generation in photonic crystal fiber. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 1135 (2006).

Roy, S., Bhadra, S. K. & Agrawal, G. P. Dispersive waves emitted by solitons perturbed by third-order dispersion inside optical fibers. Phys. Rev. A 79, 023824 (2009).

Lourdesamy, J. P. et al. Spectrally periodic pulses for enhancement of optical nonlinear effects. Nat. Phys. 18, 59–66 (2022).

Mao, D. et al. Synchronized multi-wavelength soliton fiber laser via intracavity group delay modulation. Nat. Commun. 12, 6712 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. The dissipative Talbot soliton fiber laser. Sci. Adv. 10, 2125 (2024).

Dorrer, C. & Kang, I. Simultaneous temporal characterization of telecommunication optical pulses and modulators by use of spectrograms. Opt. Lett. 27, 1315–1317 (2002).

Kelly, S. M. J. Characteristic sideband instability of periodically amplified average soliton. Electron. Lett. 28, 806–808 (1992).

Blanco-Redondo, A. et al. Pure-quartic solitons. Nat. Commun. 7, 10427 (2016).

de Sterke, C. M., Runge, A. F. J., Hudson, D. D. & Blanco-Redondo, A. Pure-quartic solitons and their generalizations—theory and experiments. APL Photonics 6, 091101 (2021).

Roffelsen, P. et al. On the integrability and singularities of the dispersion-generalised NLSE (Submitted for publication) (2024).

Olde Daalhuis, A. B., Chapman, S. J., King, J. R., Ockendon, J. R. & Tew, R. H. Stokes phenomenon and matched asymptotic expansions. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 55, 1469–1483 (1995).

Chapman, S. J., King, J. R. & Adams, K. L. Exponential asymptotics and Stokes lines in nonlinear ordinary differential equations. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 454, 2733–2755 (1998).

Oktem, B., Ülgüdür, C. & Ilday, F. O. Soliton-similariton fibre laser. Nat. Photonics 4, 307–311 (2010).

Widjaja, J. et al. Data for “Observation of the universality of nonlinear mode coupling in a fibre laser”. Zenodo. [Data set] (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Tristram Alexander for useful discussions. This research was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Center of Excellence in Optical Microcombs for Breakthrough Science (project no. CE230100006), funded by the Australian Government. A.F.J.R. is supported by the ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE220100509). The ARC Discovery Projects also support C.J.L. (DP190101190), and A.F.J.R. and C.M.d.S. (DP230102200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. performed the experiments and numerical simulations. J.W., Y.L.Q., A.F.J.S., L.H.H.S., C.J.L. and C.M.d.S. carried out the theoretical analysis. A.F.J.R. built the experimental setup. C.J.L. and C.M.d.S. supervised the overall project. All of the authors contributed to interpretation of the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Widjaja, J., Qiang, Y.L., Skelton, A.F.J. et al. Observation of the universality of nonlinear mode coupling in a fibre laser. Nat Commun 16, 5196 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60555-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60555-1