Abstract

Bacteria produce antibacterials that drive competition and regulate community composition. While diverse examples have been found, few families of antibacterial agents appear to be widespread across phylogenetically divergent bacteria. Here, we show that what appeared to be a limited, niche class of Gram-negative bacteriocins, called class II microcins, is in fact a highly abundant, sequence- and function-diverse class of secreted bacteriocins. Based on systematic investigations in the Enterobacteriaceae and gut microbiomes, we demonstrate that class II microcins encompass diverse sequence space, bacterial strains of origin, spectra of activity, and mechanisms of action. Importantly, we show microcins discovered here are active against pathogenic E. coli during mouse gut colonization, supporting important roles for these unrecognized antibacterials in vivo. Our study reveals the overlooked abundance and diversity of microcins found dispersed throughout Bacteria and opens opportunities to uncover and exploit mechanisms of competition to modulate microbial communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial community composition is regulated by competition. The production and release of antibacterials play key roles in these community dynamics, allowing established bacteria to retain their niche or invading bacteria to occupy a new community1. The importance of our microbiota to an ever-growing list of health outcomes2 has spurred the study of this natural bacterial arsenal to find ways of manipulating microbiome composition3. Gram-negative bacteria include important pathogens and commensals that are common targets for health interventions. Toxins produced by these bacteria to aid in competition typically require cell-to-cell contact (type VI secretion system effectors) or lysis of the producing cell to release diffusible toxins (colicins, tailocins). The revelation there is an overlooked, but abundant, class of long-range antibacterials4,5 that are non-self-destructively secreted from diverse Gram-negative bacteria could have profound implications on our understanding of and ability to rationally manipulate microbial communities. We have discovered such an understudied group of bacteriocins, called class II microcins, is widespread across Gram-negative bacteria and mediates competition in vitro and in vivo.

Class II microcins are antibacterial small proteins (~5–10 kDa) produced by Gram-negative bacteria6. They can be separated into class IIa and class IIb based on the post-translational attachment of a C-terminal siderophore modification onto class IIb microcins6,7. They are initially produced in a “pre-microcin” form, where an N-terminal signal sequence is fused to the core structural microcin component. The pre-microcin is processed and secreted directly from the cytoplasm to the extracellular environment by a specialized type I secretion system8,9,10. A peptidase-containing ABC transporter (PCAT) cleaves the “double-glycine”11 signal sequence during secretion, releasing the active mature microcin to the extracellular environment through its connection with a membrane fusion protein (MFP), which joins with the outer membrane efflux protein, TolC. Once secreted by a producing bacterium, microcins bind specific outer membrane receptors of target bacteria to cross the outer membrane and enter the periplasm, gaining access to antibacterial targets12,13. For clarity, the existence of class I microcins6 is noted here; this is a distinct class of Gram-negative bacteriocins which lack the size, structure, and export characteristics which define class II microcins, though they may function in a related ecological capacity12,14.

Probiotic bacterial strains like Escherichia coli Nissle and G3/10 naturally produce class II microcins that directly aid their colonization and protect against pathogen invasion15,16. Despite their potential ecological roles14, few microcins have been discovered and characterized12,13. Most validated class II microcins originate from E. coli (n = 8), in the order Enterobacterales12. Beyond the Enterobacterales, a single example each have recently been described from Acinetobacter baumannii (Moraxellales)17 and Vibrio cholerae (Vibrionales)18. Thus, their existence beyond these species and potential impacts across bacterial communities remain largely uninterrogated. Our previous computational studies suggested that class II microcins are far more diverse and widespread than previously recognized19,20. Here, we show that active class II microcins are ubiquitous across phylogenetically diverse bacterial species, readily found in varied microbial communities, and target numerous pathways to enter cells and elicit their antibacterial activity in vitro and in vivo. We reveal associations between microcins and microbiome composition, which provides future opportunities to probe the effects of microcins on microbial assemblages and use them to direct community outcomes.

Results

Active class II microcins are found across Enterobacteriaceae

Our previous bioinformatics pipeline relied on homology to the complete pre-microcin amino acid sequences of the 10 verified class II microcins12 to identify new class II microcins19, which likely limited the discovery of more divergent sequences. To increase detection of more sequence-diverse class II microcins, we performed a search based on the signal sequence only (Fig. 1A). This “double-glycine” signal sequence was originally named for the consensus glycine-glycine residues which precede the cleavage site, though glycine-alanine and glycine-serine cleavage sites were also identified11. Since then, class II microcins have been shown to possess glycine-glycine or glycine-alanine signal cleavage sites at an equal frequency (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Created in BioRender. Parker, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/n9m2y2a. A Small proteins are screened for an N-terminal double-glycine signal sequence. From thousands of hits, a set of diverse sequences are selected for antibacterial activity testing. B A Gram-negative bacterial secretion system is used to secrete putative microcins. Detection of antibacterial activity is conducted by the self-inhibition growth curve assay. C Immunity proteins, usually predicted to span the inner membrane, are added to protect the secretor from self-inhibition as needed. Zone of inhibition (ZOI) assays are performed to determine microcin spectra of activity by spotting the secretor strain on target strain(s) of interest.

Two broad regular expressions were developed from alignments of double-glycine signal sequences and used to screen all Enterobacteriaceae proteins in Uniprot <150 amino acids (AA) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The Enterobacteriaceae family was chosen because it is large, diverse, and contains many important commensals and pathogens; we hypothesized the 10 class II microcins from E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae scarcely describe its microcin diversity. We identified 1060 unique hits and named them by their source bacteria family of origin, followed by a chronological number, e.g., Enterobacteriaceae hit #112 = “EN112”. Previously verified microcins, in comparison, will be referred to by adding the standard abbreviation for microcin, “Mcc”, to their published name, e.g., microcin L = “MccL”. As there is currently no cohesive microcin naming scheme21, we will preserve both these historical names and our randomly assigned bioinformatic hit names throughout this publication.

Screening large numbers of putative class II microcins for antibacterial activity requires a new approach. Class II microcins are toxic toward cells of susceptible strains that lack the necessary immunity protein for self-protection, including the cells producing the microcin22. They access their antibacterial targets from the periplasm; only a single class II microcin (MccE492) in its mature form is known to be toxic in the cytoplasm, albeit weakly compared to in the periplasm23. Taking advantage of these facts, we reasoned that the Gram-negative bacterial microcin V (MccV) type I secretion system9 (Supplementary Fig. S2A) could be used to screen for antibiotic activity of putative microcins via self-inhibition of growth in the absence of their cognate immunity proteins (Fig. 1B).

As proof-of-concept, three known class IIa microcins (MccV, MccL, and MccN) that are toxic toward E. coli24,25,26 were tested. The native signal sequences of MccL and MccN were replaced with that of MccV to facilitate optimal secretion from the MccV type I secretion system9. For each microcin, an inducible plasmid encoding the pre-microcin was transformed into an E. coli strain expressing the microcin secretion machinery. When microcin expression is induced, the growth of E. coli is inhibited compared to the uninduced condition for that same strain (Supplementary Fig. S2B, C). Without the secretion machinery, where the pre-microcin is expressed in the cytoplasm without signal cleavage, growth per strain is similar between the induced and uninduced conditions (Supplementary Fig. S2D, E). This replicates previous findings for MccV, where cytoplasmic expression of pre-MccV in the absence of its immunity protein is nonetheless nontoxic27. Cytoplasmic toxicity is still a possibility for novel microcins identified by this screen, but additional downstream testing of active hits can parse out this and other mechanistic details as desired. Observed inhibitory effects on cell density during microcin secretion (Supplementary Fig. S2B) are mirrored by trends in the numbers of viable cells (Supplementary Fig. S2F).

Class IIb microcins require additional protein partners to facilitate attachment of their C-terminal siderophore7,28. While this modification provides optimal activity, some class IIb microcins retain partial antibacterial activity without it7,23. We tested three class IIb microcins (MccE492, MccM, and MccH47) in our self-inhibition growth curve assay, with and without the secretion machinery. Only MccE492 in the presence of the secretion machinery significantly inhibited growth when expression was induced (Supplementary Fig. S2G–J). This suggests our system can identify some class IIb microcins.

To begin to explore the large number of computationally predicted class II microcins, hits were sorted by sequence similarity to guide manual selection of diverse sequences for screening. A set of 106 putative microcins from phylogenetically diverse strains from five of the six major clades of Enterobacteriaceae29 was selected (File S1). Using the self-inhibition growth curve assay, we tested these 106 sequences and identified 29 novel microcins that inhibited the growth of E. coli (Fig. 2A, B). A workflow schematic of this initial class II microcin activity screening and subsequent downstream characterization analyses, with counts of novel microcins analyzed per step, provides an overview of assays and findings from this point forward (Supplementary Fig. S3). Since these putative microcins originated from phylogenetically diverse Enterobacteriaceae, and microcins are likely to be active towards close relatives14, we screened a subset of putative microcins for activity when secreted from Enterobacter cloacae, Leclercia adecarboxylata, and Cronobacter muytjensii (Fig. 2C). Detection of antibacterial activity varied by strain, and no one strain could be used to detect all eight active microcins. One microcin (EN4) not identified as active in the original E. coli secretion screen was confirmed here by screening in E. cloacae and C. muytjensii. Additional screening identified EN91 was active against Klebsiella aerogenes. These small, nonexhaustive activity screens confirmed two additional microcins, for a total of 31 active novel microcins. Thus, while our list of putative microcins includes hundreds more examples for testing, and many more hits could undoubtedly be obtained by expanding our search beyond the the UniProt database, our approach has already uncovered triple the number of validated class II microcins identified between 1976, when microcins were described as a class30, and 2022, when we reviewed evidence supporting validated class II microcins (n = 10)12.

A Growth curves of E. coli containing the secretion system +/− arabinose-induced expression of microcins (n = 4 per treatment). Solid lines represent the smoothed conditional means. B Area under the curve (AUC) for each growth curve in Fig. 2A. AUCs are significantly less for the induced versus uninduced treatments (p = 0.029, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, one-sided). C Growth curves of different bacterial species containing the secretion system +/− arabinose-induced expression of microcins (n = 4 per treatment). Microcins originating from species in the ‘Enterobacter’ (n = 6) and ‘Kosakonia’ (n = 1, microcin EN112) sister clades29, MccV, and empty vector negative control (NC) were secreted from Enterobacter cloacae (Ent), Leclercia adecarboxylata (Lec), and Cronobacter muytjensii (Cro). Select E. coli growth curves from Supplementary Fig. S2B and Fig. 2A are shown again for comparison. Growth curves which show self-inhibition during microcin expression (based on AUC comparisons; p = 0.029, Wilcoxon rank sum test, one-sided) are indicated with a black box.

Class II microcins are sequence-diverse with distinct activity spectra

The amino acid sequences and select sequence characteristics of the 31 active, novel Enterobacteriaceae class II microcins are presented in File S1. When the 31 novel microcins are aligned with the 10 verified microcins and an outgroup of two Gram-positive double-glycine signal-containing bacteriocins, the presumptive signal sequences (15–18 AA) can be identified (Supplementary Fig. S4). Global or regional conservation between pairs/groups of microcins can be observed, but overall similarity is low (Supplementary Fig. S4). Presumed microcin subclass, based on the presence (class IIb, n = 9) or absence (class IIa, n = 21) of glycine- and serine-rich C-termini28, is indicated (Supplementary Fig. S1). Of these 31 validated class II microcins, 10 were also identified in our earlier in silico work (6 class IIa and 4 class IIb; File S1)19. A recent in silico search for class II microcins by a different group31 recovered these same 4 class IIb microcin sequences19. They also identified 3 additional class IIb microcins31 we describe and validate in our present work only. Most recently, 4 of the class IIb microcins we validated here, all of which were already described in silico19,31, were identified and tested by a third group32,33, albeit using heterologous class IIb modification genes. For cross-referencing, sequence IDs from all three groups working concurrently are provided in File S1.

The sequence diversity of the 31 active novel microcins led us to hypothesize that they have varied spectra of activity. To test this, we used our bacterial secretion system in zone of inhibition (ZOI) assays as previously described9 (Fig. 1C). ZOI is a common, qualitative method to detect antibacterial activity of bacteriocins34, and it is particularly useful to screen secreted class II microcins, which are too long for chemical synthesis and can be difficult to purify35. For optimal secretion9, cognate immunity proteins were predicted and tested for the 29 E. coli-active microcins. They were named by appending “imm” to the cognate microcin name (e.g., immEN43). For some microcins, there were two potential immunity proteins (e.g., immEN112 and imm2EN112). Putative immunity proteins were first screened by self-inhibition growth curve assays. Co-expression of a correctly predicted immunity protein alongside its cognate microcin was expected to result in recovered growth compared to expression of the microcin only. By this metric, immunity proteins for 23 novel E. coli-active microcins were validated (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B, File S1). Additional validation of immunity proteins by ZOI assay was conducted. For example, EN64 requires two immunity proteins, supported by ZOI results (Supplementary Fig. S5C), which mirror the growth curve results (Supplementary Fig. S5B). To further demonstrate immunity protein functionality, we showed that transfer of immEN43 to a susceptible strain confers immunity to EN43 (Supplementary Fig. S5D). In total, immunity proteins for 26 microcins were validated; three of these microcins each required two immunity proteins (File S1).

With confirmed immunity proteins available to protect most of the secreting strains from self-inhibition, we investigated microcin spectra of activity by ZOI assay. A panel of 20 phylogenetically diverse bacterial strains from the Enterobacteriaceae and beyond (Supplementary Table S1) were tested as target strains. A total of 19 novel microcins (as well as known microcins MccV, MccL, and MccN) produced a ZOI on one or more of 15 target strains (Fig. 3A, B and Supplementary Fig. S6). Examples of ZOIs produced by diverse novel microcins on diverse target strains are shown (Fig. 3A). Notably, microcins are active towards bacterial strains, including drug-resistant human pathogens, not previously shown to be targeted by microcins. To examine the relationship between microcin strain of origin and microcin spectrum of activity, we generated a heatmap showing microcin activity by those two variables (Fig. 3B). Microcins range from broad to narrow spectra of activity, and a microcin’s strain of origin cannot necessarily be used to predict its spectrum range.

A Select zones of inhibition (ZOI) of 5 diverse novel microcins on 6 diverse target strains. Images are representative of triplicate assays. B Heatmap showing spectra of activity for all 19 ZOI-producing novel microcins and 3 verified microcins across 15 bacterial strains, as assessed by ZOI assay. Corresponding representative images from ZOI assays performed in triplicate are available in Supplementary Fig. S6. Species-level phylogenetic cladograms of the 15 target strains and the 22 microcin strains of origin are presented on the x-axis and y-axis, respectively. Enterobacteriaceae clades29 for these species are indicated by black bars.

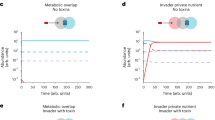

Next, we investigated whether established cultures of class II microcin-secreting bacteria may be able to provide colonization resistance36,37 against invading bacterial pathogens using an in vitro assay as a preliminary proxy38. Based on ZOI results (Fig. 3A, B and Supplementary Fig. S6), several microcin/pathogen combinations with varying susceptibility were selected for testing. Liquid cultures of E. coli secreting microcins EN43, EN44, EN112, or empty vector negative control (NC) were established for three hours. Pathogenic E. cloacae or E. coli O157 were then spiked into these cultures at microcin secretor:pathogen ratios of 103, 104, or 105, representative of the lower concentration of an invading pathogen relative to an established bacterial community. After overnight co-culture, counts of pathogens shown to be microcin-susceptible by ZOI assay were significantly lower in those respective microcin treatments compared to the control (Supplementary Fig. S7). E. cloacae invasion was impeded up to 6 logs, and E. coli O157 up to 2 logs, depending on the microcin and initial pathogen inoculum. Notably, microcin EN43 secretion did not significantly reduce E. cloacae invasion, nor did EN112 reduce E. coli O157 invasion (Supplementary Fig. S7); this correlates with the lack of observable ZOI for these microcins against these strains (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S6). Results suggest that class II microcins have the potential to enable colonization resistance against invading pathogens.

To further validate one of our microcins and compare its activity to that of a previously known microcin, we selected new microcin EN43 and verified MccV for recombinant protein production, purification, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) analysis. The core amino acid sequences (excluding the signal sequences) of these two microcins appear moderately similar (60.7% pairwise identity; File S1 and Supplementary Figs. S4 and S8A). Though they have the same spectra of activity in our broad ZOI screen (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S6), we suspected that this screen did not fully capture potential differences in their spectra of activity, given their sequence divergence. EN43 predominantly originates from Salmonella, while MccV predominantly originates from E. coli, so we selected an expanded panel of strains from these taxa for ZOI screening. ZOIs indicated that secreted EN43 was active towards the Salmonella strains, while secreted MccV had little to no observable effect on Salmonella (Fig. 4).

Spectra of activity was first assessed for E. coli-secreted EN43 and MccV by zone of inhibition (ZOI) assay. Inhibition was assessed for six strains of E. coli and Salmonella, including two E. coli K-12 derivative strains, an E. coli O157 strain, an enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) strain, Salmonella serovar Cubana encoding a carbapenemase (KPC-2), and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium. ZOI images (at top) are shown for all microcin/target strain combinations, with strain names listed above each image. Images are representative of triplicate assays. For target strains where antibacterial activity was observed by ZOI, an MIC assay was performed with that microcin in purified form (bar chart at bottom). Each dot represents a technical replicate (n = 3 per microcin per strain).

We next sought to purify EN43 and MccV and quantify their activity against select strains. Purified EN43 and MccV migrated at their expected size on SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Mass spectrometry analysis showed that, accounting for the presence of a single disulfide bond each, they had the anticipated molecular weights (Supplementary Fig. S8A, C). This effect of a probable disulfide bond on the molecular weight has been observed previously in the mass spectra of MccV11. MICs for purified EN43 and MccV are similar to each other for the four E. coli strains tested, ranging from 1–4 μg/ml (Fig. 4). MICs for purified EN43 on Salmonella are 4–8 μg/ml (Fig. 4). MICs for purified MccV on Salmonella were not tested due to lack of observed ZOI (Fig. 4). The MIC for purified negative control microcin (Vibrio cholerae microcin, MvcC)18 against E. coli W3110 was > 128 μg/ml. We note that microcin MIC does not directly correlate to ZOI size, which is a qualitative measure affected by bacteriocin solubility, diffusability, and other biochemical factors34,39. Assay-specific effects on bacteriocin bioactivity (e.g., liquid versus solid media) should be considered when assessing the effects of microcins on bacterial interactions34. Results indicate that EN43 and MccV do have different spectra of activity by ZOI, and target strains, including drug-resistance clinical isolates, are susceptible to these microcins at therapeutically-relevant concentrations. This analysis provides a starting point for future detailed examinations of microcin SAR, a necessary step for the development of novel antibacterial drugs40.

Class II microcins target diverse receptors and pathways

Class II microcins interact with outer membrane receptors to cross the Gram-negative outer membrane and elicit their antibacterial action. Beyond this, the features of microcin mechanisms of action, if known, are variable. Outer membrane crossing may be coupled to energy transport systems41,42, and inner membrane receptors may be required to insert into/disrupt the inner membrane or access the cytoplasm22,23. Some of the proteins required for the activity of known microcins have been identified, but many are unknown12.

Our observed diversity in microcin sequences and activity spectra suggests a similar diversity in the mechanism of action and antibacterial targets. To identify the key proteins involved, we exposed an E. coli random bar code transposon-site sequencing (RB-TnSeq) library43 to microcins to identify mutants with increased fitness. Co-culture of a microcin secretor with a microcin-susceptible target strain results in a decrease in target cells over time (Supplementary Fig. S9A). Similarly, co-culture of a microcin secretor with the RB-TnSeq library should eliminate susceptible strains while sparing resistant strains, which can be identified using bar code sequencing (BarSeq)43 (Fig. 5A). Co-culture of the RB-TnSeq library with E. coli secreting a novel (n = 7) or known (n = 3) microcin was conducted. High fitness for mutants with transposon insertions in specific genes indicated a role for their encoded proteins in microcin uptake or the mechanism of action.

A An RB-TnSeq mutant library is co-cultured with bacteria secreting a microcin of interest. BarSeq is conducted to compare reads/mutants at time-zero (T0) to reads/mutants after microcin treatment to identify mutants with increased fitness. Created in BioRender. Parker, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/krrbel6. B BarSeq log2 ratios (microcin treatment sequencing counts/time-zero control sequencing counts) for mutants in the 13 genes involved in microcin uptake by and antibacterial activity on E. coli for the 10 microcins analyzed here. Microcins targeting the same outer membrane receptor are indicated by different shades of the same color (red = CirA, blue = FhuA, yellow = OmpF).

As proof our application of BarSeq works, we recapitulated the identification of three key proteins known to be involved in the mechanisms of action of two verified microcins (Fig. 5B, Table 1 and File S2). For MccV, these were CirA, TonB, and SdaC22,44; for MccL, these were CirA and TonB42. More importantly, TonB and 10 other proteins were identified which have never been implicated in the mechanisms of these microcins (Fig. 5B, Table 1 and File S2). All 13 proteins were validated by ZOI assay using the E. coli Keio single gene knockout collection45,46 (Supplementary Fig. S9B–D), demonstrating the unrecognized breadth of bacterial proteins needed for microcin activity.

To visualize the relationships between microcin sequences and the proteins needed for their activity, we generated a phylogeny (Fig. 6) from the sequence alignment of 41 class II microcins (Supplementary Fig. S4). Abundant unresolved basal phylogenetic relationships (n = 18) reflect high microcin sequence divergence overall, but well-supported subclades identify some families of related microcins. Particularly, six pairs of microcins have > 90% bootstrap support for being sister taxa, indicating their sequence similarity and suggesting likely homology. The two largest major clades contain a mix of both class IIa and class IIb microcins; this is because the C-terminal sequence motif that delineates class IIb microcins is a very small portion (~10 amino acids) of the total pre-microcin sequence6,28, so it does not drive global sequence similarity. Onto this phylogeny (Fig. 6), we mapped all proteins needed for activity identified here or in previous studies (Table 1). Proteins involved in microcin uptake and the mechanism of action correspond to microcin phylogenetics, with members of well-supported subclades having key proteins in common. Thus, while microcin sequences are diverse, specific sequence-activity relationships are present.

Two Gram-positive double-glycine signal-containing bacteriocins (Pediocin PA-1 and Piscicolin-126) are included as the outgroup. Branch support values < 50% are collapsed. The eight major clades are each indicated in a different color. The taxonomic clade of origin29 of the strain from which the microcin originated is indicated by a symbol. Class IIb microcins are indicated by ‘IIb’; the remainder are class IIa. Alternate names for 4 class IIb microcins concurrently identified by another group32,33 are noted in blue text. Outer circles indicate proteins involved in microcin uptake and mechanism of action, by clade: red = outer membrane (OM) receptor, yellow = uptake mechanism and/or proteins that act in the periplasm, and blue = inner membrane (IM) receptor/target/other requisite interior proteins. Proteins were explicitly identified (here and/or in previous literature, Table 1) for underlined microcins; they are inferred based on sequence similarity for non-underlined microcins.

Our results clarify many features of known microcins and reveal new pathways targeted by microcins discovered here. Previously, the proteins requisite for MccN activity were unknown. We show that MccN belongs to a clade with novel microcins EN44, EN101, and EN511, and all use the outer membrane iron uptake receptor, FhuA (Fig. 6). While FhuA is a receptor for class I microcins J25 and Y47,48, it has not previously been identified as an outer membrane receptor for any class II microcin. MccN, EN44, EN101, and EN511 share additional requisite proteins (TonB, ManYZ) in common with MccE4927,23, a verified microcin in a sister clade with novel microcin EN51 (Fig. 6). Sequence comparisons support these findings (Supplementary Fig. S4). Mature microcins contain an N-terminal antibacterial domain and a C-terminal uptake domain49. N-terminal sequence similarity between the two clades corresponds to the use of the same antibacterial activity proteins, while C-terminal divergence corresponds to the use of different outer membrane receptors7.

Another major discovery is the identification of a putative inner membrane receptor/target for MccL and its novel homolog, EN76. Clades represented by MccL and MccV have similar C-terminal uptake domains25. Accordingly, they utilize the same outer membrane receptor, CirA, as well as TonB, which presumably facilitates crossing into the periplasm42,44 (Fig. 6). Beyond that, their sequences and proteins required for activity diverge. Only the inner membrane receptor of MccV, SdaC, has been identified22. Here, we discovered that TatA, which forms a channel across the inner membrane to transport folded proteins in the twin-arginine translocation pathway, is required for EN76 and MccL activity and represents a new microcin inner membrane target.

Though novel microcins EN82 and EN112 lack a resolved phylogenetic relationship (Fig. 6), we discovered both use OmpF as the outer membrane receptor and require DsbAB, which catalyze disulfide bond formation, for activity. EN82 and EN112 contain multiple cysteine residues (File S1); perhaps DsbAB forms disulfide bond(s) necessary for microcin activity in the periplasm or are targets for microcin antibacterial activity. Previous work with MccPDI pursued a similar hypothesis but found conflicting results on whether DsbA and DsbB deletion affected susceptibility to MccPDI50,51. In addition, for EN82, the uncharacterized protein, YafD, is involved. It has homology to an exonuclease/endonuclease/phosphatase family of proteins, but has not been previously implicated in microcin biology.

Interestingly, our results indicate the requirement of the entire TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex for microcins using FhuA as an outer membrane receptor, but TonB only for those using CirA. The TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex harnesses the proton motive force to transport cargo across the outer membrane and is suggested to function in energy-dependent transport of microcins41. TolQR complementation of ExbBD52, as shown for MccL42, may explain our findings for microcins targeting CirA; however, ExbBD complementation does not maintain susceptibility to FhuA-targeting microcins. Unlike other microcins, none of the TonB-ExbB-ExbD energy transduction system is required for microcins using OmpF as the outer membrane receptor. This suggests that new microcins discovered here may cross the outer membrane via OmpF without the need for cell envelope-derived energy.

Class II microcins promote competition in the mouse gut

The gut contains diverse commensal and pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae, which play an important role in gut health. We hypothesized that some of our novel Enterobacteriaceae-origin microcins retain activity in vivo and could enable a microcin-producing strain to outcompete a competitor strain in the gut. To test this, we selected a neonatal mouse model of enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) infection53,54,55. ETEC is an important cause of diarrheal disease in humans, and the first step in its pathogenesis is colonization of the small intestine. Interfering with colonization is of key interest in preventing ETEC infection, and this function may be performed by native gut microbiota56. ETEC strain B41, which naturally colonizes the neonatal mouse small intestine53, was transformed with a plasmid encoding inducible secretion of microcins EN43, EN44, or EN112 (with their immunity proteins), or an empty vector. Each of these microcins targets a different outer membrane receptor (Fig. 5). Based on their robust secretion from and activity toward E. coli B41 (Fig. 7A), EN43 and EN44 were selected for competition testing in mice. Mice were inoculated with equal numbers of a Lac + B41 microcin-secreting strain and a Lac- B41 control plasmid strain (Fig. 7B). Colonization was allowed to develop for 12 h, and then microcin production was induced. Three hours later, bacteria were recovered from the mouse small intestines and plated to determine Lac + /Lac- ratios. When Lac+ and Lac- strains encoded empty vectors, they were found in a 1:1 ratio, indicating no competitive advantage for either strain (Fig. 7C). However, when the Lac+ strains secreted EN43 or EN44, they outcompeted the Lac- control strain by ~5-fold over just three hours (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that the microcins we have discovered are active against target cells in a native gut microbiome.

A Zone of inhibition (ZOI) assays for E. coli B41 Lac+ secreting a microcin (EN43, EN44, EN112) or negative control (NC) on E. coli W3110 or E. coli B41. Only EN43 and EN44 produced a ZOI on E. coli B41 and were selected for in vivo competition experiments. Images are representative of triplicate assays. B Neonatal mice are gavaged with E. coli B41 encoding secretion of a microcin/control (Lac+, blue) and a control (Lac-, white) at a 1:1 ratio. After transit to the small intestine, microcin expression is induced, and the small intestine is excised and plated to determine the ‘competitive index’: the normalized ratio of blue (secretor): white(control) colony-forming units (CFU). Created in BioRender. Parker, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/2xrcyef. C Competitive index per mouse small intestine. Two experiments were performed with 5 mice each for EN43 and NC (n = 10 per microcin) and 4 mice each for EN44 (n = 8). The target pathogen was outcompeted by the EN43 and EN44 microcin secretors (p = 9.8 × 10−5, Kruskal-Wallis test; pEN43-NC = 0.00012 and pEN44-NC = 0.0045, Dunn’s test.

Human fecal microbiomes contain numerous, diverse class II microcins

Our microcin explorations have focused on mining assembled Enterobacteriaceae genomes. We hypothesized that class II microcins are abundant throughout complex bacterial communities, and uncaptured microcin diversity exists in microbiomes. To test this, we updated our class II microcin bioinformatic pipeline19 using our newly discovered microcins (Supplementary Fig. S10) and analyzed metagenomes derived from human fecal samples in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi’omics Database (IBDMDB)57. This dataset includes samples from both healthy and dysbiotic guts, as delineated by a dysbiosis score computed based on microbiome composition57. In addition, some of these metagenomes were enriched in Enterobacteriaceae58. We hypothesized the IBDMDB fecal metagenomic dataset would contain novel class II microcins, including some of those we validated.

Examination of fecal metagenomes from 130 patients identified 1041 putative class II microcins. Their top bacterial families of origin are Bacteroidaceae (690 hits; 66.3%), Enterobacteriaceae (194 hits; 18.6%), Morganellaceae (14 hits; 1.3%), and Pseudomonadaceae (10 hits; 0.96%). From this data, we identified 174 unique sequences that grouped into 68 clusters having ≥ 50% pairwise sequence similarity (Fig. 8A). Among the 68 clusters, 8 (11.8%) contain sequences that are the same or similar to validated class II microcins discovered here (n = 3) or previously (n = 5). Two clusters are represented by validated Gram-positive double-glycine signal-containing bacteriocins. Source strains for the 58 unvalidated clusters were Gram-negative (28 clusters; 48.3%), Gram-positive (5 clusters; 8.6%), or unknown (25 clusters; 43.1%). A phylogeny of the 68 cluster representatives (Supplementary Fig. S11A) shows some concordance between putative microcin sequence similarity and likely species of origin. Plotting the percentage of fecal metagenomes of origin classified as dysbiotic57 per cluster revealed discernible variations in host dysbiosis status per microcin cluster (Supplementary Fig. S11B). Some microcins clusters were only found in healthy guts (n = 4), while some were only found in dysbiotic guts (n = 2). Significantly, we confirmed our hypothesis that novel microcins validated here (EN33, EN34, and EN82) and abundant, putative microcins can be detected in human gut metagenomes; these results suggest microbiomes are rich in unrecognized microcins.

A Microcin hits identified from metagenomes were clustered at ≥50% sequence similarity; bars represent hit counts per cluster. Each cluster is labeled by the most likely bacterial species of origin. The legend indicates hit identity (known/novel) by putative source (Gram +/−) per cluster. B Distribution of microcins identified in metagenomes, which were expressed in a paired metatranscriptome from the same fecal sample. Expressed microcins per unique metatranscriptome were sorted per cluster defined in (A); their count summed per genus of origin is shown in parentheses. Percentages represent these counts divided by the total number of microcins expressed in unique metatranscriptomes (n = 205).

Given the abundance of putative class II microcins from the Gram-negative Bacteroidaceae in these fecal metagenomes, we compared their sequences with those of the ‘bacteroidetocins’59,60, a recently validated group of class II microcin-like bacteriocins from the Bacteroidaceae. Bacteroidetocins are small proteins (<100 amino acids) that possess a 15 amino acid double-glycine signal sequence and are encoded near a PCAT, which is required for toxin production59. Antibacterial activity has been confirmed for 4/19 identified bacteroidetocins59.

Though the 19 bacteroidetocins were not found among our putative class II microcins from the Bacteroidaceae, we observed that the double-glycine signal sequences of the bacteroidetocins (Supplementary Fig. S12) were divergent from those of the Enterobacteriaceae class II microcins signals (Supplementary Figs. S1, S4), which may affect their detection with our pipeline. When we instead searched for the bacteroidetocins among all putative metagenomic open reading frames (ORFs) generated by the initial part of our pipeline, we found 3/19 bacteroidetocins, two of which have confirmed antibacterial activity and were particularly abundant (Supplementary Fig. S12). This indicates that, if indeed the bacteroidetocins are equivalent to class II microcins, they cannot be found using our current pipeline, and the extent of total class II microcin sequence diversity still has yet to be reached.

Because metatranscriptomes are available for many of the IBDMBD fecal samples57, we hypothesized that class II microcin expression could be detected in this dataset. For metagenomes where we identified microcin(s), 309 paired metatranscriptomes were available. Within 182 of these metatranscriptomes, we detected expression of class II microcin(s) identified in their corresponding metagenome. Accounting for the occurrence of multiple expressed microcins per metatranscriptome, microcins were found to be expressed a total of 205 times (Fig. 8B) across these 182 metatranscriptomes. These expressed microcins represent 17 of the clusters identified from metagenomes (Supplementary Fig. S11C and Fig. 8B), including the top 11 most abundant clusters (Fig. 8A). Enterobacteriaceae-origin microcin expression was detected 15 times, representing 9 microcin clusters (Fig. 8B). Of particular interest, transcripts of known microcins MccPDI, MccV, MccH47, and MccI47 were detected, as well as novel microcin EN33. This suggests that, while known Enterobacteriaceae class II microcins may be more prevalent and/or active in the human gut, perhaps contributing to their earlier discovery, novel microcins likely play a role as well. Our results highlight the diversity of microcins, which are prevalent in diverse human gut microbiomes and could be influencing gut health.

Discussion

The time course of class II microcin discovery has been long. Microcin V was discovered 100 years ago in 192561, a few years before the discovery of penicillin. Microcins were recognized as a unique class of small bacteriocins in 197630, with the delineation of class II microcins in 20076. By 2022, a total of 10 class II microcins had been identified and characterized to varying degrees12. Here, we have dramatically expanded the count of class II microcins from the Enterobacteriaceae with confirmed antibacterial activity, with characterization of cognate immunity proteins, spectra of activity, and key proteins involved in mechanisms of action for many of these microcins. We have used this opportunity to sketch broad outlines of class II microcin prevalence, diversity, and functionality in hopes that this unrecognized, untapped resource can be examined comprehensively going forward to understand what role these abundant, overlooked small proteins play in the microbiome.

While we focused here on expanding confirmed microcin diversity in the Enterobacteriaceae, where microcins were first identified and have demonstrated potential for regulating important human pathogens in vivo15,62, this is a case study in what is possible. Based on our present and previous analyses19, microcins exist well beyond the Enterobacteriaceae and seem almost pervasive in some phylogenetic contexts. This is consistent with the observation that PCATs are widely distributed across Gram-negative bacteria63; a function for PCATs other than export of double-glycine signal-containing small proteins has not been reported. Such widely distributed secretable proteins, which should be biologically expensive64,65, warrant additional work to determine their roles in interbacterial competition and microbiome regulation.

Through additional in silico, in vitro, and in vivo analyses of select class II Enterobacteriaceae microcins, we have also attempted to illustrate the possible range in microcin functional diversity. Our identification of key proteins necessary for antibacterial action by a small subset of E. coli-active microcins suggests there are more novel proteins to identify. Both from the perspective of enabling crossing of the Gram-negative outer membrane and functioning as a final antibacterial target, exploring the mechanisms involving these key proteins could prove invaluable for antibacterial drug development. Our efforts to examine the presence and function of class II microcins in the context of gut microbial communities suggests that microcins play an ecological role in the gut, which could be regulated to our advantage. The microcins presented here, and their putative homologs, are indeed present in human gut metagenomes, including those of Enterobacteriaceae-enriched, dysbiotic guts58. Furthermore, these microcins can enable bacteria to successfully outcompete pathogens in a neonatal mouse model.

The lack of a standardized class II microcin nomenclature21 remains unresolved. A consistent nomenclature will hopefully emerge in the future when microcin diversity and sequence-activity relationships (SAR) are understood in greater detail. Classifying class II microcins based on their species of origin is problematic due to horizontal gene transfer, both via plasmids and the chromosome66. Categorization based on sequence is also difficult, given the modularity of class II microcin antibacterial and uptake domains49. Nomenclature based on the outer membrane receptor(s) required for microcin activity is a promising option, but more receptor identification is needed.

Using our collection of Enterobacteriaceae class II microcins, we sought to outline the breadth of possibilities where increased, detailed examinations of microcins can make fundamental research contributions. The study of microcins has the potential to advance our understanding of mechanisms of action of natural antibacterials and microbial community dynamics in ways that could contribute greatly to the design of novel antibiotics, methods for antibiotic delivery, and regulation of bacterial communities. Here, we have established the means and impetus to revitalize microcin research.

Methods

In silico signal sequence-based microcin screen

All verified class IIa (V, L, N, PDI, S) and class IIb (H47, I47, M, G492, E492) microcin N-terminal signal sequences were aligned (Geneious Prime 2022.1.1, https://www.geneious.com), and a regular expression pattern was developed to represent this protein motif (Supplementary Fig. S1), following ScanProsite pattern syntax67. This regex (Motif 1: < M…Rx[IL]x9G[GAS]) was developed to screen for proteins with microcin-like signal sequences. Specific residues (e.g., R or [IL]) were only incorporated if they described all 10 sequences. It also incorporates the option for a terminal serine (S), which has been reported in Gram-positive double-glycine signal sequences63,68. ScanProsite67 was used to screen for proteins ≤ 150 AA (~16.5 kDa pre-microcin/~14.9 kDa mature microcin) with this motif in UniProtKB (SwissProt and TrEMBL databases). Taxonomy was restricted to Enterobacteriaceae (databases accessed 06/25/2021). A second search was performed using a motif from the double-glycine signal sequences, which facilitate export of Gram-positive bacteriocins in the IIa/YGNGN (‘pediocin-like’) class. Gram-positive signal sequences (n = 13) were aligned, and another regex (Motif 2: < M…[KEQI]x[IL]x9G[GAS]), which also includes the C-terminal serine option, was developed (Supplementary Fig. S1). This search was performed in the Enterobacteriaceae (databases accessed 8/11/22). These motifs were intentionally broad, with an expected tradeoff of a higher false positive rate than our published pipeline19.

Selection of Putative microcin candidates

Microcin candidates identified through signal sequence-based screening were manually curated to select a range of unique/divergent sequences for cloning into the Gram-negative (E. coli) bacterial secretion system9. We excluded hits with high sequence similarity to the 10 verified microcins, fragments of full-length microcins, and false positives (based on protein annotations). Hits were analyzed with NeuBI (Neural Bacteriocin Identifier), a recurrent neural network-based software for bacteriocin prediction69 to guide selection. NeuBI assigns a probability that each protein is a bacteriocin; its default threshold for a putative bacteriocin is ≥0.95. Instead, we selected proteins with a range of NeuBI bacteriocin probabilities to include an assortment of divergent sequences. Most, but not all, had a probability ≥0.70. The final selection of putative microcin sequences was 10% of the total hits identified.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Routine bacterial culture was performed in lysogeny broth (LB) medium. Antibiotics were added as needed per plasmid (pBAD18Km – kanamycin, pACYC184 –chloramphenicol, pBAD18Amp and pMMB67EH – carbenicillin). Microcin secretion (pBAD18Km + pACYC184) was performed in M9 minimal medium with glycerol as a carbon source, to prevent glucose-induced catabolite repression of the arabinose-inducible pBAD promoter (araBAD), supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids. E. coli DH5α was selected for its recA1 genotype, which results in recombination deficiency to increase stability for toxic microcins; M9 for this strain was supplemented with 0.001% thiamine.

Cloning and transformation of verified and putative microcins

Presumptive native double-glycine signal sequences (Supplementary Fig. S4, File S1) were removed from microcins in silico and replaced with the microcin V signal (cvaC15 - MRTLTLNELDSVSGG) utilized by the secretion system9. Microcins were cloned (by GENEWIZ, now Azenta Life Sciences) into pBAD18Km (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Constructs were transformed into NEB 5-alpha chemically competent E. coli cells (New England Biolabs) containing the constitutively expressed PCAT and MFP (pACYC184 pTc CvaAB) necessary for microcin export. For non-E. coli strains, cells were transformed via electroporation. The final export partner, TolC, is natively chromosomally encoded in all secreting bacterial strains used here.

Self-inhibition growth curves

Growth curves of E. coli DH5α cells containing one of the pBAD18Km microcin constructs (+/− cognate immunity protein) and the pAYCY184 export machinery construct were conducted to screen for self-inhibition. Cells were seeded (OD600 = 0.05) into M9 minimal medium, aliquoted (200 μl/well) into a 96-well plate, and treated with 0.4% arabinose to induce microcin expression (induced) or an equivalent volume of water (uninduced). Per microcin, duplicate colonies were analyzed in duplicate per treatment (n = 2 colonies x 2 replicates x 2 treatments = 8 wells per microcin). Plates were incubated (37 °C) with shaking (800 rpm) in a BioTek LogPhase 600 Microbiology Reader (Agilent), and OD600 was measured every 10 min for 6 h. Scatterplots of the growth curves were generated with ggplot270. Per treatment, the smoothed conditional mean was computed using method = ‘loess’ and plotted. Area under the curve (AUC) was compared for induced versus uninduced growth curves per putative microcin. If the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was significant (p < 0.05) and the mean AUC (uninduced) was >15% more than the mean AUC (induced), the microcin was considered active. These criteria are conservative to eliminate false positives, and results correspond well to visual observations of the plotted growth curves. Additional growth curves were conducted in Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13047, Leclercia adecarboxylata ATCC 23216, or Cronobacter muytjensii ATCC 51329 containing the E. coli secretion system (pACYC184 pTc CvaAB). The subset of microcins tested in these strains included all putative microcins originating from “Enterobacter clade” (n = 18) and “Kosakonia clade” (n = 3) species, as well as MccV.

Self-inhibition viability counts

Cell viability of E. coli DH5α secreting MccV, MccL, MccN, and the empty vector control (NC) was assessed during the course of secretion. Cells were seeded (OD600 = 0.05) into M9 minimal medium + 0.4% arabinose, and 5 ml were aliquoted into two replicate culture tubes. Cells were incubated (37 °C) with shaking (220 rpm). At two-hour intervals (0–6 h), 200 μL were serially diluted, and 100 μl of the target dilutions were spread-plated on LB agar plus antibiotics. After 24 h at 37 °C, colony-forming units (CFU) were enumerated. Two replicate experiments were conducted and their results pooled.

Immunity protein candidate selection and cloning

Previously verified immunity proteins are encoded immediately adjacent to their cognate microcin, relatively small in size (≤216 AA), and localized to the cytoplasmic membrane, evidenced by the presence of transmembrane helix domains12. We manually searched for candidate immunity proteins fitting this description in the annotated representative genome assembly (File S1) for each novel microcin which inhibited the growth of E. coli DH5α. Sometimes, manual prediction of short, unannotated coding sequences was employed to find a good candidate. Restriction digest cloning was conducted to add the commercially synthesized candidate or verified immunity proteins (gBlocks Gene Fragments, Integrated DNA Technologies) 5′ to the pBAD18Km microcin constructs. Immunity function was confirmed by self-inhibition growth curves (30 °C, 800 rpm, as described above) and ZOI assays (described below). When the immunity protein was desired in the target strain rather than the secreting strain (Supplementary Fig. S5D), we transformed the target strain with the existing pBAD18Km construct (microcin plus cognate immunity) without the secretion system construct (pACYC184 CvaAB). Because cytoplasmically expressed pre-microcins do not inhibit the producing strain (Supplementary Fig. S2D, E)27, creation of an immunity only construct was not needed.

Zone of Inhibition Soft Agar Overlay Assays

Zone of inhibition (ZOI) assays were used to confirm microcin secretion/activity against target bacterial strains. M9 minimal agar (1.5%) plates were overlaid with molten M9 minimal soft agar (0.75%) seeded with the indicator bacterial strain at OD600 = 0.01. Per the secretion vector, an inducing agent was also added to the soft agar (pBAD18Km − 0.2% arabinose; pMMB67EH – 1 mM IPTG). Overnight cultures of secretor strains were normalized by cell density (OD600) and centrifuged at 4000 x g for 5 min. Supernatant was removed, and cells were resuspended in a small volume of M9 medium by pipetting. Secretor strain spots (OD600 = 50) of 10 µl were applied to solidified soft agar. Negative control (NC) empty vector secretors were spotted as a control. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For E. coli B41 pMMB67EH strains used in mouse colonization assays (Fig. 7; see below), secretor strains were instead grown on plates prior to use in ZOI assays to replicate the growth conditions of the mouse inoculum. Cells were scraped from plates and resuspended in M9 medium (OD600 = 90) prior to spotting. To assess the spectrum of activity per microcin, ZOI assays for microcins secreted by E. coli DH5α (with co-expressed cognate immunity proteins, as needed) were conducted (in triplicate) against a panel of 20 target bacteria (17 Enterobacteriaceae, one Yersiniaceae, and two Morganellaceae; Supplementary Table S1). BLAST of confirmed novel immunity proteins indicated no significant sequence similarity in the genomes of the 20 strains tested.

Liquid in vitro colonization resistance Assays

Previous in vitro single-strain and microbial community38,71,72 colonization resistance assays were used as a guide to set up experiments with microcin-secreting bacteria and target pathogens in co-culture. E. coli DH5α strains secreting microcins EN43, EN44, EN112, or the empty vector control (NC) were seeded at OD600 = 0.05 into M9 minimal media containing 0.4% arabinose to induce microcin expression. Per microcin secretor, 100 μl of this suspension was added to each of 16 wells of a 96-well plate. Plates were incubated (37 °C) with shaking (800 rpm) in a BioTek LogPhase 600 Microbiology Reader (Agilent). OD600 was measured in the LogPhase every 20 min for 3 hrs to confirm similar growth rates between strains. At 3 h, the plates were removed from the LogPhase for inoculation with target pathogens. M9 with 0.4% arabinose was seeded with E. coli O157 AR-0427 or E. cloacae ATCC 13047 at OD600 0.0002, 0.00002, and 0.000002. For each pathogen, 100 μl of each of the 3 dilutions or unseeded media control was added to duplicate wells containing EN43, EN44, EN112, or NC microcin secretors. Accounting for 3 hrs of microcin secretor growth (to ~ OD 0.2) and 50% dilution each of the secretor and pathogen when combined, relative secretor:pathogen OD600 values at the start of their co-culture were approximately 0.1:0.0001 (103), 0.1:0.00001 (104), or 0.1:0.000001 (105). The plates were returned to the LogPhase and incubated (37 °C) with shaking (800 rpm) for 19 h. Each assay well was 10-fold serially diluted in 1X phosphate-buffered saline and plated on LB medium containing 100 μg/ml streptomycin, to which both pathogen strains are natively resistant, but the microcin secretors are susceptible. Pathogen CFU were then enumerated after 24 h of growth at 37 °C. This experiment was repeated in triplicate, and results from all three assays were pooled. Statistical significance was determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by post hoc Dunn’s tests.

Purified microcin production and biochemical analysis

Microcins EN43 and MccV were purified as maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusions. Each core microcin sequence was cloned into pETM11-MBP73 with a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease recognition site between the MBP and the microcin N-terminus. This plasmid construct was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS ΔmalE. An overnight culture in LB plus antibiotics was subcultured in 1 L and grown (37 °C, 220 rpm) until OD600 = 0.5; then, 1 mM IPTG was added to induce protein expression. The culture was grown for 5 additional hours and centrifuged. Pellets were frozen at −80 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 25 mL of column buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA at pH 7.4) with a Pierce Protease Inhibitor Tablet. The cell slurry was lysed using sonication and centrifuged to remove debris. The supernatant was passed through a gravity column containing 0.5 bed volume of amylose resin (New England Biolabs) to bind MBP. The column was washed with 3 column volumes of column buffer and then eluted using elution buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM maltose, pH 7.4). The highest concentration elutions were combined and digested with TEV protease overnight at 4 °C to cleave MBP, yielding crude purified microcin with a residual N-terminal glycine. The crude microcin solution was dialyzed overnight into dialysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate dibasic buffer at pH 7.4), and the tag-free microcin was collected by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a Superdex™ 75 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) on an ӒKTA pure™ chromatography system (Cytiva). The highest concentration fractions were combined and incubated with amylose resin to remove MBP. The slurry was passed through a gravity column, and microcin flow through was concentrated by centrifugation through a 3 kDa MWCO filter (Amicon). Purified MvcC, a microcin from Vibrio cholerae, which is inactive towards E. coli18, was produced with the same method above for use as a negative control.

Purified EN43 and MccV were quantified using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and visually confirmed using SDS-PAGE of 100 pmol each microcin on a NuPAGE® Novex Bis-Tris 4–12% Gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Molecular weight was determined using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The sample was first desalted using a high-flow liquid chromatography protein trap column. Mass spectrometry was done using an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Raw data was deconvoluted using Protein Deconvolution Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of purified microcins

Purified class II microcins EN43 and MccV were tested for activity by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay in 96-well polystyrene plates following the EUCAST reading guide for broth microdilution version 5.0 (https://www.eucast.org/ast_of_bacteria/mic_determination), with some modifications. Assays were conducted in M9 minimal medium prepared as described for other assays above. Purified MvcC18 was used as the negative control. Maximum starting microcin concentration was 32 μg/ml for EN43 and MccV and 128 μg/ml for the Vibrio cholerae microcin (MvcC) negative control. The starting microcin concentrations were serially diluted 2-fold in the 96-well plate. The initial bacterial inoculum per well was ~5 × 105 CFU/ml, which was confirmed by plating the inoculum at the time of the assay and enumerating CFU after incubation overnight at 37 °C. Triplicate technical replicates were performed per microcin per strain. MIC plates were incubated 18 h at 37 °C and OD600 was read per well.

Sequence analysis

Amino acid multiple sequence alignments were generated with MAFFT v7.490 using the -auto setting74. Enterobacterales strain phylogenies (Fig. 3B) were generated with phyloT v2 (https://phylot.biobyte.de/) using the genome taxonomy database (GTDB, release 214) taxonomy and visualized in Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6.8.275. The microcin phylogeny (Fig. 6) was generated from the Supplementary Fig. S4 sequence alignment with RAxML76 using the Gamma WAG protein model77 with the rapid bootstrapping algorithm (n = 1,000 bootstraps) and a search for the best maximum likelihood tree. Branches with support values <50% were collapsed using Dendroscope 3.8.878. The final tree image was produced using Geneious Prime. Biochemical characteristics were computed in Geneious Prime. Hydrophobic residues are considered to be (in order of hydrophobicity): F, L, I, Y W, V M, P, C, and A (Expasy). DeepTMHMM was used to predict the number of transmembrane helices79. Microcin subclass (IIa or IIb) was predicted for novel microcins based on their sequences. Verified class IIb microcins have glycine- and serine-rich C-termini28 which terminate in a serine; for class IIb MccE492, this is the site of covalent attachment of its siderophore modification80. In addition, the representative genomes of novel class IIb microcins were searched for putative homologs of genes which catalyze siderophore attachment encoded near the microcin80,81. Cysteine residues were enumerated; their presence suggests the possibility of disulfide bonds, which have been documented among verified IIa microcins11,25.

Co-culture of microcin-secreting E. coli with Target Cells

Microcin-secreting bacteria were co-cultured with target bacteria to determine if they could kill target bacteria in liquid co-culture. E. coli DH5α secreting EN43 ( + cognate immunity), EN112 ( + cognate immunity), or empty pBAD18Km negative control (NC) were co-cultured with E. coli BW25113, the parent of both the Keio collection45,46 and the RB-TnSeq library43. E. coli BW25113 was transformed with pBAD18Amp to serve as a counter-selectable target strain compared to the microcin secretor strains (pBAD18Km + pACYC184). Secretors were inoculated at OD600 = 0.2 and the target strain at OD600 = 0.02 in M9 minimal media + 0.2% arabinose. Culture tubes were incubated at 37 °C with shaking (220 rpm). Samples were collected, serially diluted, and plated on LB medium + carbenicillin at 0, 3, and 6 h post-inoculation. After 24 hrs of incubation at 37 °C, E. coli BW25113 pBAD18Amp CFU per ml were enumerated for the EN43, EN112, and NC treatments.

Identification of proteins involved in microcin uptake and activity

A random bar code transposon-site sequencing (RB-TnSeq) library was previously generated from E. coli BW2511343. Co-culture of microcin-secreting bacteria with this RB-TnSeq library was conducted to identify mutants resistant to an E. coli-active microcin of interest. A 1 ml aliquot of the E. coli KEIO_ML9 RB-TnSeq library43 was inoculated into 25 ml LB + 50 μg/ml kanamycin and incubated (37 °C) with shaking (200 rpm) until mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.4). The resuscitated library and 5-ml overnight cultures of E. coli DH5α secreting the microcins of interest were centrifuged (4000 x g x 10 min). Pellets were resuspended in 1 ml (library) or 200 μl (secretors) of M9 medium. An aliquot of the library (400 μl) was centrifuged again, and the pellet frozen at −80 °C to serve as the time-zero sample. Flasks containing 10 ml M9 medium + 0.2% arabinose were inoculated with the library (OD600 = 0.02) and a microcin-secreting strain (OD600 = 0.2). They were incubated (37 °C) with shaking (200 rpm) for 20 h. Cultures were centrifuged as before, and the pellets frozen at − 80 °C.

DNA was isolated from the pellets, and mutant bar codes were PCR-amplified to create sequenceable DNA libraries. Then, bar code sequencing (BarSeq) was performed to determine the fitness of individual mutants. DNA isolation was performed with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) following the protocol for Gram-negative bacteria. PCRs to add Illumina-indexed adapters to generate the sequencing libraries included: 25 μl Q5® Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs), 0.5 μM each primer, 50–100 ng DNA, and water to 50 μl. The published common reverse primer (BarSeq_P1) and one of the first 10 forward primers (BarSeq_P2_IT001 – BarSeq_P2_IT010) from the published BarSeq protocol was used43. PCR cycling conditions were: 98 °C for 4 min, followed by 20–25 cycles of 98 °C for 30 sec, 55 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec, followed by 72 °C for 5 min. For BarSeq Experiment 1 (EN43, EN112), 50 ng of DNA were amplified for 25 cycles. For BarSeq Experiment 2 (MccV, MccN, EN44, EN101, EN511) and Experiment 3 (MccL, EN76, EN82) 100 ng of DNA were amplified for 20 cycles. BarSeq of co-culture and time-zero untreated control DNA libraries was conducted on a MiSeq (Illumina) using V3 SR150 sequencing. Using published BarSeq Perl and R scripts, the log2 ratio of sequencing counts relative to the time-zero control was computed, per microcin treatment, per mutant, to determine fitness per gene43. This bioinformatic analysis allowed the identification of mutants with increased fitness.

The Keio collection of E. coli K-12 strain BW25113 single-gene knockout mutants45 was used to validate key proteins involved in microcin uptake and activity indicated by BarSeq analysis. Secreted microcins were screened for loss of activity against select Keio mutants as compared to the Keio parent strain by ZOI assay. All ZOI assays were performed in duplicate. Based on sequence similarity (Supplementary Fig. S4), phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 6), and BarSeq results (File S2), three groups of microcins contained presumptive homologs: (1) MccV/EN43, (2) MccL/EN76, and (3) MccN/EN44/EN101/EN511. For each group, mutants identified in the top 20 highest fitness mutants for ≥ 75% of the microcin treatments were selected for Keio ZOI testing. For EN82 and EN112, all top 20 Keio mutants, if available, were examined. For mutants that exhibited the phenotype which corresponded with BarSeq results (i.e., loss or reduction of ZOI when exposed to the microcin of interest; n = 13, Supplementary Fig. S9), the presence of the kanamycin cassette at the correction insertion site was confirmed by PCR82. Individual forward primers located upstream of each deleted gene were designed and paired with a published common reverse primer located on the kanamycin cassette82 (Supplementary Table S2).

Neonatal mouse colonization assays

A spontaneous rifampin-resistant (RifR) mutant of E. coli B4153,83 was transformed with pMMB67EH + CvaAB + microcin (EN43, EN44, or EN112) + cognate immunity or pMMB67EH + CvaAB only negative control (NC). These E. coli B41 secretors were tested by ZOI assay targeting E. coli W3110 to confirm secretion was as expected based on previous results using E. coli DH5α as the secretor strain (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S6). With secretion confirmed, ZOI assays were then performed to determine activity towards E. coli B41. The two microcins with activity towards E. coli B41 (EN43 and EN44) were selected for in vivo analyses. A spontaneous lacZ (Lac-) mutant of E. coli B41 (RifR) was transformed with pMMB67EH + CvaAB to serve as the control strain during in vivo competition experiments.

Neonatal mice (Mus musculus CD-1; Charles River Laboratories) were housed with the mother under a 12 h light/dark cycle at 30 °C and 55% humidity. Mouse experiments were adapted from our previous work84. Immediately prior to the experiment, 5–7-day-old mice were weaned for 3-4 h and pooled from multiple litters. Bacterial strains grown on selective agar medium overnight at 37 °C were individually scraped and resuspended in LB liquid medium. Lac + (secretor) and Lac-(control) strains were mixed 1:1 in LB, and 50 μL of this competition mixture, containing 1 × 106 CFU, were inoculated by oral gavage into a randomly selected mouse. Serial dilutions of the mixture were plated on LB + X-gal medium and enumerated to determine the input ratio of Lac + (blue):Lac-(white) strains (File S3). After incubation at 30 °C for 12 hr, mice were inoculated with 50 μl of 10 mM IPTG by oral gavage to induce microcin expression. After 3 hr, mice were sacrificed, and small intestines were removed and homogenized in 10 mL of LB medium. Serial dilutions were plated on selective LB + X-gal medium and enumerated to determine the output ratio of Lac + (blue):Lac-(white) strains (File S3). The competitive index for each strain, calculated per mouse small intestine, is defined as the output blue/white ratio, normalized by the input blue/white ratio, then normalized by the mean normalized blue/white ratio of the controls (File S3). Per experiment, there were 5 mice each per EN43 and NC (control) treatments and 4 mice per EN44 treatment. The experiment was performed twice, and the results from the two experiments were combined. Statistical significance was determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by post hoc Dunn’s tests.

Update to bioinformatics pipeline for in silico class II microcin identification

Screening the representative genome assemblies (File S1) with cinful19 failed to identify all novel Enterobacteriaceae microcins. In response, enhancements were made to cinful to establish a pipeline capable of identifying the expanded set of known class II microcins, herein referred to as cinful v2. Three significant modifications were made to the pipeline. First, an exhaustive method for open reading frame (ORF) calling was implemented. Six of the seven microcins missed by cinful were found in other source assemblies, prompting a search for a method to improve the labeling of proteins from genomic data. We replaced Prodigal85 with a simple, exhaustive ORF-finding tool that labels all genomic regions between a start (ATG, GTG, TTG) and stop codon. A minimum length of 63 base pairs (20 AA) was established.

Next, the profile hidden Markov model (pHMM) was retrained using the 41 verified Enterobacteriaceae pre-microcin sequences, which include the 31 novel sequences verified here. We reasoned that a pHMM incorporating our expanded training dataset would enhance the identification of putative microcins with increased novelty, while minimizing the occurrence of spurious results86, so we also removed the BLAST search component included previously19. This retrained pHMM was initially applied as a filtering step with an E-value threshold of 10,000.

Finally, two secondary signal sequence pHMMs were added: one trained on the 41 verified microcin signal sequences and one trained on 13 double-glycine signal sequences from Gram-positive bacteriocins (Supplementary Fig. S1). The outcomes from the initial screening with the pre-microcin pHMM were subjected to a secondary analysis using two additional signal sequence pHMMs. For the second screening step, an E-value cutoff of 1.0 was applied. Sequences not included in this second screening were excluded if they did not meet the E-value threshold of 1.0 in the initial screening. Cinful v2 was used to screen the Enterobacteriaceae genomes previously analyzed with cinful v119; a comparative evaluation of results before and after this update was performed (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Computational screen of fecal metagenomes for putative class II microcins

Cinful v2 was employed to conduct an exploratory screen of metagenomic assemblies derived from human fecal samples for the presence of microcins. The dataset was comprised of all metagenomic assemblies (1606 samples from 130 patients) and associated metadata available from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi’omics database (IBDMDB, https://ibdmdb.org/) and described in the associated publication57. These 130 patients each had from one to 26 metagenome samples, generally collected biweekly. Cinful v2 was executed on these assemblies, and putative microcin ORFs were subjected to clustering using MMseqs2 at a 50% minimum sequence identity threshold87. The MMseqs2 linclust setting with a coverage mode of -cov-mode 1 was used; this calculates the sequence identity based on the shorter sequence between query and target. MMseqs2 chooses the cluster centroid sequence as the cluster representative, which was used in downstream analyses.

Post-identification of putative microcins, information regarding the most similar known bacteriocin, if any, and the species of origin was generated through local pBLAST and nBLAST analyses of the cluster representative88. pBLAST involved querying all putative microcin amino acid sequences against a database comprised of all 41 validated class II microcins and all 229 bacteriocins from BACTIBASE (retrieved 12/21/2023)89. BACTIBASE is a manually curated collection of bacteriocin sequences, which includes numerous diverse, unrelated types of bacteriocins, such as Gram-positive double-glycine signal-sequence bacteriocins, Gram-negative colicins, and class I microcins. nBLAST utilized the nucleotide sequence of each putative microcin, querying it against the entire NCBI bacterial database. Both searches were conducted with default parameters, with cutoff thresholds determined post hoc. The top result for each putative microcin was used to determine the most similar known bacteriocin if the default E-value of 10 produced a result, and the source species was determined with an E-value cutoff of 1e-20.

A phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. S11A) was constructed using RAxML HPC-PTHREADS with the PROTGAMMAAUTO model on the representative amino acid sequences for each of the 68 clusters, as produced by MMSeqs276. The label for each leaf was generated by nucleotide BLAST of the representative sequence, as described above. The tree was visualized in iTOL v575. For putative microcin clusters that appeared in the dataset ≥5 times, the dysbiosis status (TRUE/FALSE) of each sample of origin as determined by the dysbiosis score was obtained from the metadata57. Per microcin cluster, the percentage of its samples of origin considered dysbiotic were plotted to determine if certain microcin clusters were more likely to be found in dysbiotic samples than in non-dysbiotic samples (Supplementary Fig. S11B).

The IBDMDB fecal metagenome dataset was searched for the presence of 19 published bacteroidetocins59. All possible ORFs identified within the IBDMDB metagenomes by the exhaustive ORF-finding tool, which serves as the initial step of the cinful v2 pipeline, were screened for the bacteroidetocins using pBLAST with an E-value threshold of 0.1. Hits with 100% pairwise identity were counted and summed for each bacteroidetocin.

Among the metagenomes that contained confirmed/putative microcins, 309 had a paired metatranscriptome available from the same fecal sample57. Each of these metatranscriptomes was analyzed using kallisto90 to identify transcripts that matched to the microcin sequence(s) originally identified in the paired metagenome. Pseudoalignment of metatranscriptome reads was performed using the paired metagenome contigs assembled by IBDMDB as the reference sequence, where microcin sequence(s) identified previously in a given metagenome were extracted to separate contigs to facilitate specific detection of microcin expression. With multiple microcins detected in some of the metagenomes, a total of 397 searches for microcin transcription were performed within the 309 metatranscriptomes. Microcins that were expressed in one or more transcriptomes were assigned to the clusters from Fig. 8A, and the sum of transcripts per million (TPM) for each cluster were computed using kallisto90 (Supplementary Fig. S11C). The counts of microcins expressed in a unique metatranscriptome, sorted by cluster, were used to generate two pie charts. The first shows the most prevalent microcin cluster against all others, with the minor slice expanded to show a second chart with the other clusters. Summed counts of microcin clusters identified in unique metatranscriptomes and their percentage of total counts were computed per genus of origin.

Ethics statement

Animal experiments were performed with protocols approved by The University of Texas at Austin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The University of Texas at Austin Animal Resources Center (ARC) is accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International and meets National Institutes of Health standards as set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011).

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses and data visualization were performed in R91 using the following packages: tidyverse (v2.0.0)92, dplyr (v1.1.2)93, ggplot2 (v3.5.2)70, broom (v1.0.5)94, scales (v1.4.0)95, DescTools (0.99.50)96, egg (v0.4.5)97, and ggsignif (v0.6.4)98. Metagenomic computational analyses and resulting figures were created using the Python programming language and Matplotlib99. A minimum of three biological replicates were required for reproducibility. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Class II microcin sequences, immunity sequences, class IIb modification sequences, representative genome assemblies per microcin, and associated in silico sequence characterization is available in File S1. BarSeq data is available in File S2. Mouse intestine blue-white screening colony counts and competitive indices are available in File S3. The data for generating Fig. 8, Fig. S10, and Supplementary Fig. S11, are available at https://github.com/AaronFeller/Cinful_v2.

Code availability

The version of cinful v2 used for this manuscript has been archived at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13272923100. The most up-to-date version of cinful v2, along with the code for generating Fig. 8, Fig. S10, and Fig. S11, are available at https://github.com/AaronFeller/Cinful_v2.

References

Peterson, S. B., Bertolli, S. K. & Mougous, J. D. The central role of interbacterial antagonism in bacterial life. Curr. Biol. 30, R1203–R1214 (2020).

VanEvery, H., Franzosa, E. A., Nguyen, L. H. & Huttenhower, C. Microbiome epidemiology and association studies in human health. Nat. Rev. Genet. 24, 109–124 (2023).

Milshteyn, A., Colosimo, D. A. & Brady, S. F. Accessing bioactive natural products from the human microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 23, 725–736 (2018).

Booth, S. C., Smith, W. P. J. & Foster, K. R. The evolution of short- and long-range weapons for bacterial competition. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 2080–2091 (2023).

Celik Ozgen, V., Kong, W., Blanchard, A. E., Liu, F. & Lu, T. Spatial interference scale as a determinant of microbial range expansion. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau0695 (2018).

Duquesne, S., Destoumieux-Garzón, D., Peduzzi, J. & Rebuffat, S. Microcins, gene-encoded antibacterial peptides from enterobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 708–734 (2007).