Abstract

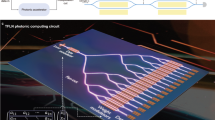

Real-time, physically realistic rendering is a significant challenge in spatial computing systems due to the excessive computational intensity of ray tracing and the performance limitations of current electronic platform. Here, we propose and demonstrate the first photonic counterpart for ray tracing acceleration, capable of performing ray-box intersection tests in the optical domain. Leveraging the high bandwidth, high linearity, and superior efficiency of thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN), our photonic ray tracing core (PRTC) achieves significantly more rapid and energy-efficient computation compared to traditional electronic hardware. Furthermore, by exploiting the binary nature of ray-box intersection tests, we reduce the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) bit-width requirement to a single bit, effectively overcoming the primary bottleneck in analog computing accelerators—the power consumption dominated by ADCs. As a result, our PRTC achieves an energy efficiency of 326 femtojoules per operation (fJ/OP) and demonstrates a modulator bandwidth exceeding 100 GHz. This advancement achieves significant improvements in both speed and energy efficiency by orders of magnitude. Our work demonstrates the feasibility of using photonic chips for ray tracing, effectively circumventing the ADC bottleneck of optical computing systems, and paves the way for future innovations in high-performance, low-power spatial computing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spatial computing is revolutionizing various sectors by seamlessly integrating digital information with the physical world. This fusion facilitates the creation of immersive experiences across entertainment, virtual workspaces, education, and healthcare, fundamentally transforming how we interact with our surroundings and digital content1,2,3,4,5,6. A critical aspect of spatial computing is achieving real-time, physically realistic rendering, which is essential for providing visually accurate and interactive experiences. Ray tracing is a key technique in this regard, simulating the behavior of light to produce realistic images or videos by accurately modeling reflections, refractions, and shadows7,8,9,10.

The ray tracing process begins by casting primary rays from the camera into the scene. When these rays intersect with objects, secondary rays are generated to simulate complex optical effects. The largest computational burden in ray tracing is determining whether rays intersect with objects in the scene. The majority of these calculations involve ray-box intersection tests within the Bounding Volume Hierarchies (BVH), which are data structures designed to accelerate collision detection by hierarchically grouping objects in bounding volumes11. Achieving realistic scenes requires casting millions of rays per frame, with some estimates indicating that around one billion rays per second are necessary for photorealistic quality in complex scenes12. However, traditional computing hardware faces significant challenges in handling the vast number of ray-box intersection tests required for real-time applications13,14. Power consumption and heat generation are significant issues, especially in portable spatial computing devices like augmented reality (AR) glasses. High power consumption leads to rapid battery depletion, limiting the operational time of these devices. Additionally, excessive heat generation can cause discomfort to the user and may require bulky cooling solutions that are impractical for lightweight wearable devices. Moreover, the clock frequencies of current CPUs and GPUs are limited by RC delay15 and power dissipation16, making it difficult for them to exceed 10 GHz, which exacerbates the challenges in achieving real-time, low-latency rendering.

These constraints highlight the need for innovative solutions to overcome the limitations of existing hardware architectures and enable more efficient real-time rendering. Optical computing has emerged as a promising candidate for next-generation computing hardware platforms. Photonic chips exploit the ultra-high bandwidth of optoelectronic devices, enabling them to operate at clock speeds several-orders-of-magnitude higher than current electronic chips17. Furthermore, the various physical dimensions of light, including wavelength, modes, and polarization, offer significant computational parallelism, which can be harnessed to accelerate computational tasks. Finally, photons can execute computations by simply propagating through optical circuits, with minimal loss and energy dissipation. For instance, the waveguide losses in thin-film lithium niobate chips can be as low as 0.06 dB/cm18, making these systems highly energy-efficient. Extensive research has been conducted on leveraging optical computing for various algorithms, such as deep neural networks19,20,21,22,23,24,25, integral equation solving26,27, and cryptocurrency28. These studies utilize specific optoelectronic devices and structures to accelerate the execution of operations, demonstrating the potential of optical computing in achieving high-speed, energy-efficient computation. However, existing optical computing systems face two major challenges that limit their practicality and widespread adoption.

First, silicon photonics, despite its advantages in low-cost, large-scale fabrication and the availability of functional devices, encounters critical trade-offs due to its free-carrier-based modulation mechanism29. This mechanism results in nonlinear electro-optic responses, carrier-absorption losses, and limited response speeds, which impact signal fidelity, power consumption, and operating bandwidth. These limitations hinder the performance of silicon-based photonic systems, especially in applications requiring high-speed and high-linearity operation.

Second, analog optical computing architectures often suffer from significant power consumption due to the analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) required to interface optical computations with electronic processing systems. Applications like neural networks typically demand high-resolution ADCs to capture the analog optical signals representing computational results. The power consumption of ADCs increases exponentially with the bit width30 and the necessity for high bit-width ADCs leads to substantial power overheads. This exponential increase in power consumption not only raises the overall energy requirements but also effectively negates the energy efficiency gains provided by the optical computation itself31. This issue is especially problematic in systems where power efficiency is paramount and remains a critical challenge that needs to be addressed to realize practical, energy-efficient optical computing systems.

In this work, we address the crucial issues of speed and energy consumption for ray tracing hardware by proposing a photonic ray tracing core (PRTC) based on thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) photonics. Our PRTC is designed to perform ray-box intersection tests within the optical domain, leveraging the inherent advantages of photonics to accelerate this computationally intensive task. The PRTC features four push-pull high-speed electro-optical modulators and a coherent detection branch, enabling high-speed and energy efficiency of intersection tests. By utilizing TFLN photonics, our PRTC overcomes the performance trade-offs associated with silicon photonics. TFLN offers high electro-optic coefficients, low optical losses, and excellent linearity, which are critical for high-performance photonic devices32,33,34,35,36 and efficient photonic computing23,37,38,39,40. Our PRTC achieves a linear optical field response at CMOS-compatible voltages and an electro-optic bandwidth of 100 GHz, significantly surpassing the capabilities of traditional silicon-based photonic devices. Furthermore, our PRTC addresses the ADC power consumption challenge by reducing the ADC bit width requirement specifically in ray tracing tasks. In ray tracing, the output result of a ray-box intersection test is binary—it either intersects or does not intersect. This allows us to reduce the ADC bit width to a single bit, effectively minimizing the power overhead associated with analog-to-digital conversion and achieving an energy efficiency of 326 fJ/OP. The practicality and effectiveness of our PRTC were validated through an experimental demonstration of ray tracing at a clock frequency of 16 giga-symbol per second (GS/s), showcasing its capability to handle the high-speed computations required for real-time rendering.

Results

Concept and principle of PRTC

The PRTC represents a novel approach to accelerating ray-box intersection tests in spatial computing applications through optical domain processing. This section details the fundamental concepts, working principles, and advantages of our proposed PRTC architecture.

To create realistic graphics in spatial computing applications, such as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR), one needs to accurately simulate how light interacts with virtual objects. This simulation process is called ray tracing, which works by tracing the path of light rays as they bounce around a virtual scene. For each pixel we want to render, we need to cast rays from a virtual camera and determine what objects these rays hit, calculating reflections, shadows, and other lighting effects. Figure 1a illustrates this concept in an AR environment, where we need to render a virtual fox model that appears to exist in the real world.

a Applications of PRTC in spatial computing for real-time physically realistic rendering. b Schematic representation of the ray-traversal and ray-box intersection. Left: hierarchical BVH tree structure illustrating the traversal path (highlighted by colored boxes) for efficient ray-object intersection determination. Right: geometric illustration of ray-box intersection computation based on side functions, which evaluate the relative orientation between ray and box edges to determine intersection results. v1, v2 and r1, r2 refer to the bounding-box coordinates and the ray coordinates. c Implementation of the PRTC on TFLN platform. The PRTC consists of four high-speed push-pull Mach-Zehnder modulators (MZMs) for parameter encoding, followed by coherent optical processing and detection components (photodetector (PD) and 1-bit ADC) for binary result generation. d Energy consumption analysis comparing PRTC with optical neural networks (ONN). e Performance comparison of PRTC with existing electronic and optical computing platforms. The plot shows energy efficiency versus computation speed, with the shadow area indicating the electronic limit and the red dashed line indicating the ADC bottleneck (0.58 pJ/OP). PRTC achieves superior performance compared to both electronic solutions and previous optical implementations, with potential for further improvements.

However, checking if a ray intersects with every single triangle in a complex 3D model would be extremely computationally expensive. In Fig. 1a, we can see these bounding boxes shown in red, green, and blue colors with each become smaller and smaller. This Bounding Volume Hierarchies (BVH) allows us to quickly eliminate large portions of the scene that a ray definitely would not hit - if a ray does not hit the large red box, we do not need to check any of the smaller boxes or triangles inside it.

Figure 1b describes the fundamental mechanisms of BVH traversal and ray-box intersection computation. The left panel demonstrates the hierarchical traversal process within the BVH structure, where intersection tests are performed sequentially through nested bounding volumes, with the traversal path highlighted by colored boxes. The right panel illustrates the geometric principle underlying ray-box intersection determination, which utilizes side relation calculations41. The box, represented by six vectors (depicted as red arrows) forming a closed loop, enable intersection detection through consistent side relation evaluation. A ray is determined to intersect the box only if it maintains consistent side relations with all six head-to-tail edge vectors. For Ray-Axis Aligned Bounding Boxes (AABB), where edges are parallel to coordinate axes, the side relation computation reduces to a dot product operation: \({{\rm{side}}}\left({{\rm{ray}}},{{\rm{edge}}}\right)=\,{r}_{1}\times {v}_{1}+\,{r}_{2}\times {v}_{2}\), where \({v}_{1},\,{v}_{2}{{\rm{and}}}{r}_{1},\,{r}_{2}\) refer to the bounding-box coordinates and the ray coordinates, respectively. The detailed derivation of how each coordinate is used in the side-function-based intersection algorithm could be found in Supplementary Note 1. Due to the cumulative nature of BVH traversal, where the intersection of a BVH node depends on the intersection results of its ancestor nodes, reduced precision arithmetic can be utilized for ray traversal. Previous work has demonstrated that quantization to 5 bits is feasible for ray-box intersection tests14.

This mathematical foundation enables the acceleration of ray-box intersections using an analog photonic core. The PRTC architecture, as illustrated in Fig. 1c, comprises three main functional blocks: box data loading, ray data loading, optical processing and detection for binary results. In the box data loading stage, the box parameters \({v}_{1},\,{v}_{2}\) are encoded through two push-pull Mach-Zehnder modulators (MZMs). Similarly, the ray data loading stage uses another pair of MZMs to encode the ray parameters \({r}_{1},\,{r}_{2},\). The optical processing and detection block combines the modulated signals with a reference branch through coherent interference, followed by a photodetector and 1-bit analog-to-digital converter to generate the binary intersection result. \({r}_{1},\,{r}_{2},\,{v}_{1},\,{v}_{2}\) are directly loaded as voltages on four push-pull MZMs. By adjusting the heaters to ensure that the MZMs is biased at the null point (for linear response when signal amplitude remains relatively small) and are phase-matched when the three branches are combined (Supplementary Note 2), the light field at the output port can be expressed as: \({E}_{{out}}=\,{{E}_{{ref}}+{E}_{0}{\mathrm{sin}}{r}}_{1}\times \sin {{v}}_{1}+\,{{E}_{0}{\mathrm{sin}}{r}}_{2}\times \sin {{v}}_{2}\). Where \({E}_{{out}}\) is the output light field, \({E}_{{ref}}\) is the light field in the reference branch and \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{0}\) represents the light field in other two branches. When the MZM operates in the linear region, the input voltage can be directly mapped to the output light field since sin x is approximately equal to x. Therefore, \({E}_{{out}}\) can be rewritten as: \({E}_{{out}}=\,{{E}_{{ref}}+{E}_{0}}(r_{1}\times {v}_{1}+{r}_{2}\times {v}_{2})\). This suggests that our PRTC can be directly used for ray-box intersection tests when operating in the linear region. Although at the output of the detector, the photoelectric effect converts the optical field signal into an electronic signal, resulting in a nonlinearity due to the quadratic relationship between the optical power and the light field, this does not impact the functionality of the PRTC. This is because we are ultimately concerned with the sign of the output results: the relative values of \({E}_{{out}}\) and \({E}_{{ref}}\) and the output can then be processed by 1-bit ADC to generate the binary result:

The relationship between analog-to-digital converter (ADC) / digital-to-analog converter (DAC) power consumption and bit width plays a crucial role in determining the energy efficiency of optical computing systems, as illustrated in Fig. 1d. The red and blue lines show the exponential growth of ADC power consumption and the relatively modest increase in DAC power consumption with increasing bit width30, respectively (detailed calculation models can be found in Supplementary Note 5). This relationship becomes particularly significant when comparing the power efficiency of PRTC with traditional optical neural networks (ONNs).

In ONNs, while some architectures attempt to reduce ADC power consumption by summing outputs and converting them to digital signals using fewer ADCs, this approach fails to effectively reduce the power consumption per operation. Although fan-in accumulation can reduce the number of ADCs, it requires the bit width of each ADC to grow logarithmically with the number of accumulated results (see Supplementary Note 4). Since ADC power consumption increases exponentially with bit width, the power consumption per operation remains high despite the reduced number of ADCs.

To quantitatively analyze the power consumption, we use the energy consumption model in ref. 30. For ONNs, while the DAC power consumption can be neglected due to the input dimension being far smaller than the number of computational operations, the ADC power consumption is significant. In contrast, PRTC’s architecture reduces power consumption through its binary output nature and the DA bit-width requirement is 5-bit for box data and ray data loading. With each 1-bit AD conversion, PRTC achieves a remarkably low AD power consumption of 33fJ/OP, representing more than an order of magnitude improvement over traditional ONNs (detailed in Supplementary Note 6).

The performance advantages of our PRTC implementation are comprehensively demonstrated in Fig. 1e, which compares the energy efficiency and computation speed across different computing platforms. Operating well below the ADC bottleneck (indicated by the red dashed line at 0.58 pJ/OP), our PRTC demonstrates an exceptional energy efficiency of 326 fJ/OP (detailed in Supplementary Note 6) while maintaining a remarkable bandwidth of 100 GHz. These metrics represent significant advancements in ray tracing hardware capabilities, achieving a two-order-of-magnitude improvement in speed and a one-order-of-magnitude reduction in power consumption compared to existing solutions. This dramatic performance enhancement can be attributed to two key innovations: the utilization of TFLN’s superior optoelectronic properties for high-speed, linear signal processing, and our binary detection scheme that significantly reduces the ADC power consumption overhead for ray-box intersection tests. This advancement represents a significant step forward in enabling real-time ray tracing for spatial computing applications, with potential for even further improvements through continued optimization of the TFLN platform with lower operating voltage36,42.

TFLN platform for PRTC

The characterization of our PRTC with TFLN platform are presented in Fig. 2. The overall structure of the fabricated PRTC chip is shown in Fig. 2a, featuring four push-pull MZM modulators, each measuring 6 mm in length. Figure 2b displays a scanning electron microscope image of the waveguide sidewall, demonstrating the quality of fabrication. The RF packaging of the chip is illustrated in Fig. 2c, where one end of the traveling wave electrode connects to the RF input connector and the other end to a matching resistor for optimal RF performance. Figure 2d shows the flip-chip photodetector used for monitoring the optical signals.

a Photograph of the overall structure of the PRTC chip, with each push-pull MZM modulator measuring 6 mm in length. The highlighted regions indicate the on-chip grating intended for the monitoring PD. b Scanning electron microscope image of the waveguide sidewall. c RF package of the chip, with one end of the traveling wave electrode connected to the RF input connector and the other end connected to a matching resistor. d The flip-chip photodetector used for monitoring. e Normalized optical transmission of a MZM as a function of the applied voltage, showing a half-wave voltage of 3.79 V. f Response of the light field to the driving voltage, linear response (blue line), measured result (orange line). g Electro-optic response of the MZM in PRTC chip.

The electro-optic performance of the TFLN platform is characterized in Fig. 2e-g. Figure 2e shows the \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{\pi }}}}\) of 3.79 V. The response of the light field to the driving voltage is demonstrated in Fig. 2f, where the blue line represents the ideal linear response and the orange line shows the measured result. Thanks to the high linearity of lithium niobate, the measured response shows excellent agreement with the linear response, achieving linearity better than 99.3% at 1Vpp operation and 97.9% at 2Vpp operation. This exceptional linearity enables direct mapping of input voltage to light field without requiring look-up table circuits, significantly reducing the peripheral circuitry complexity. While optical computing remains far from achieving general-purpose processing capabilities of electrical chips, the CMOS-compatible voltage operation and excellent linearity of the TFLN platform facilitate seamless integration between optical and electrical components, which is crucial for maximizing the performance of optical computing systems.

Figure 2g presents the electro-optic response of the MZM, demonstrating a 3 dB bandwidth of approximately 100 GHz, suggesting a potential increase in computational speed by nearly two orders of magnitude compared to existing hardware systems. This high bandwidth, combined with the excellent linearity and CMOS compatibility of the TFLN platform, makes it particularly suitable for high-speed optical computing applications.

Experimental demonstration of PRTC

Here, we present the experimental demonstration of our PRTC shown in Fig. 3a to evaluate the computing accuracy. A continuous-wave (CW) laser operating at 1550 nm wavelength serves as the light source, with its output directed into the PRTC chip. The optical signals are modulated by four on-chip TFLN modulators before undergoing coherent beam combining at the output port. The output optical power is then converted to electrical signals via a photodetector (PD) and recorded using an oscilloscope for analysis. The modulation signals for the four TFLN modulators are generated using a four-channel high-speed arbitrary waveform generator (AWG). The data rate is set to 16 GS/s (4 samples per data point at 64 giga-sample per second). An FPGA is employed to control the on-chip heaters, enabling precise adjustment of the modulators’ linear operating points and ensuring proper phase matching for beam combining (see Supplementary Note 3). The computing accuracy of the PRTC is validated through the testing using four sets of 10,000 random values applied to the TFLN modulators (Fig. 3a). Analysis of the measurement results reveals that the errors between the experimental measurements and the ground truth exhibit a standard deviation of 2.21% at 16 GS/s, corresponding to a computing accuracy of 5.57-bits (Fig. 3b-e). This accuracy level meets the requirements for ray-box intersection computations as established in ref. 14.

a Experimental setup of the PRTC demonstration. CW laser continuous-wave laser, PC polarization controller, AWG arbitrary waveform generator, FPGA field programmable gate arrays, PD photodetector. b, c Experimental output results of random input at 16GS/s. d Scatter plot for computing accuracy measurement with 4 sets of 10,000 random inputs. e Histogram of compute errors over 10,000 data samples.

To systematically evaluate the computational capability of PRTC, we first conducted extensive ray-box intersection tests using a comprehensive validation framework. The framework incorporates 10,000 randomly generated test cases, designed to cover diverse geometric configurations encountered in real-time rendering scenarios. Operating at a data rate of 16 GS/s, our PRTC achieved a remarkable overall accuracy of 94.6% in intersection detection. The error analysis reveals two types of misclassifications: 3% of actual intersections were misclassified as misses, and 2.4% of non-intersections were incorrectly identified as hits. Importantly, these false positive cases (2.4%) can be efficiently filtered out through subsequent precise intersection calculations in the ray tracing pipeline, as the BVH traversal inherently requires additional verification for positive intersection results. Figure 4a illustrates the binary classification results for a representative subset of 100 test cases. Each test was configured with carefully controlled parameters to ensure comprehensive coverage of possible intersection scenarios. Specifically, we positioned ray origins at the maximum coordinate point (max_x, max_y, max_z) and defined bounding boxes with their minimum vertices at the origin (0,0,0). The maximum vertices were constrained according to the fundamental principle of bounding volume hierarchies, where child boxes maintain dimensional ratios of at most 1:16 relative to their parents, corresponding to our 5-bit box encoding resolution. To provide detailed insights into the PRTC’s discrimination capabilities, Fig. 4b presents nine characteristic test cases with their corresponding geometric configurations and computational outputs. Each case demonstrates our implementation of the edge-based intersection algorithm, which evaluates six critical side relation values representing the ray’s position relative to the box edges in a head-to-tail connected sequence. The intersection criterion is met when all six values are positive, mathematically proving that the ray maintains consistent sidedness with respect to the complete edge loop. Cases (ii) and (iv) exemplify successful hit detection where rays penetrate their respective bounding boxes, while the remaining cases showcase various non-intersection scenarios. This diverse set of examples validates the PRTC’s robust ability to accurately classify complex geometric relationships between rays and axis-aligned bounding boxes.

Following the validation of PRTC’s accuracy in ray-box intersection tests, we further evaluated its performance in complete ray tracing rendering applications. We constructed three test scenes featuring various material properties and geometric configurations. Each scene was rendered with both a conventional digital computer and our PRTC system under identical conditions: 300 × 300 resolution, 400 samples per pixel, and a maximum path depth of 10. The scenes incorporate multiple material types, including diffuse surfaces, metals, and dielectric materials with refractive index of 1.5. These materials showcase different light transport phenomena such as diffuse reflection, specular reflection, and refraction. Our PRTC system was specifically tasked with performing ray-box intersection tests for all secondary rays, which are crucial for accurate global illumination and material interaction effects. The quality metrics reveal that PRTC achieves high-fidelity rendering results comparable to conventional computing as shown in Fig. 5. The Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) values range from 21.22 to 21.78 dB, while the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) maintains values between 0.9101 and 0.9186 across three test cases. The minor differences between PRTC and reference renderings primarily stem from the Monte Carlo sampling noise inherent in the path tracing process, rather than from systematic errors in the ray-box intersection tests. This is evident from the fact that both renderings exhibit similar noise patterns characteristic of path tracing with 400 samples per pixel. These metrics indicate that PRTC not only preserves the overall visual appearance but also accurately captures fine details and material properties, demonstrating the robustness of our optical computing approach in realistic rendering applications.

Discussion

Our work demonstrates a significant advancement in integrating optical computing with practical applications, specifically addressing the critical challenges in real-time ray tracing for spatial computing systems. It is widely recognized that ray intersection calculations represent the most computationally intensive part of the ray tracing pipeline, typically accounting for 70-80% of the total computational overhead43. The PRTC we designed, acting as a photonic counterpart for ray tracing acceleration, can greatly accelerate this ray intersection process. Consequently, the burden on the electrical components can be significantly minimized. As shown in Table 1, our PRTC achieves substantial improvements in both computing speed and energy efficiency compared to existing electronic and optical platforms. A detailed discussion of power consumption for all relevant components, including the laser, modulator driving, pre-processing (DAC), and post-processing (ADC), is provided in Supplementary Note 6. While conventional electronic solutions are limited by RC delays and power dissipation, and previous optical neural networks face fundamental ADC bottlenecks, our PRTC overcomes these limitations through innovative architectural design.

These performance advantages stem from two key innovations: First, by leveraging the unique properties of TFLN photonics—high bandwidth, excellent linearity, and CMOS-compatible voltage operation—we have effectively addressed the performance limitations typically associated with silicon photonics. Second, our binary detection scheme substantially relaxes the ADC bottleneck traditionally constraining optical computing by leveraging single-bit detection tailored to ray-box intersection tests, achieving substantial power savings while maintaining high accuracy. In addition to these benefits, the TFLN platform provides straightforward pathways for scaling up computation through both wafer-scale integration44 of multiple PRTC cores and wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) of signals. Leveraging TFLN’s broad spectral transparency45, one can operate multiple wavelength channels in parallel and process large arrays of data simultaneously. We discuss the advantages of parallel processing in detail in Supplementary Note 7.

The success of PRTC highlights a crucial principle in optical computing system design: the importance of matching computational architecture to specific application requirements. By focusing on ray-box intersection tests and exploiting their binary nature, we achieve substantial performance benefits through single-bit ADC implementation. This approach demonstrates how application-specific optimization can unlock the full potential of optical computing platforms.

Looking forward, several promising research directions emerge from this work. First, advances in TFLN device engineering, particularly in reducing operating voltages42 and improving integration density46, could further enhance the performance and efficiency of PRTC-based systems. These improvements would be particularly valuable for mobile spatial computing applications where power efficiency is paramount. Second, by adopting segmented TFLN modulators with binary-drive capability as illustrated in ref. 40, we can eliminate external DAC overhead and achieve a seamless interface between the PRTC and digital electronic chips (see Supplementary Note 8). Third, the principles demonstrated in our binary detection scheme could be extended to other computational tasks that can be reformulated as binary decisions, potentially opening new applications for optical computing beyond ray tracing. Finally, the integration of PRTC technology with emerging augmented reality systems presents opportunities for developing next-generation spatial computing platforms that combine high performance with energy efficiency. By co-designing the electronic pipeline and photonic interface to maximize parallelism, the PRTC can reach its full potential in these applications.

Methods

Chip fabrication and packaging

The devices were fabricated on a commercial x-cut LNOI wafer from NANOLN, with a 500 nm LN thin film, a 4.7 μm buried SiO2 layer and a 500 μm silicon substrate. The fabrication process of the TFLN chip is detailed in the following: electron beam lithography (EBL) was first used to define the rib waveguide structures on the AR-P 6200 resist. Then, the patterns were transferred to the top LN layer with an etching depth of 260 nm by Ar+-based inductively coupled plasma (ICP) dry etching. Then, the strip waveguides for the edge coupler were defined on the LN layer with an etching depth of 260 nm using EBL and ICP dry etching. At last, a SiO2 layer with a thickness of 1 µm was deposited on the wafer as the upper-cladding by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). Finally, the chips are cleaved and facet polished.

In terms of optical packaging, a single-mode fiber was chosen to achieve optimal mode-field matching, considering the double-layer horizontal edge coupler with 3.2μm spot size. A customized single channel fiber array (FA) was aligned with the edge coupler and fixed by UV-curable glue. As for electrical packaging, the chip is placed in a custom-built metal tube shell, in which the RF connection and DC bias connection parts are involved. The input RF pads of MZMs are wire bonded to the ceramic transmission lines, which are connected to the RF coaxial connectors. To achieve impedance matching, a load resistor is attached at the end of the travelling-wave electrode.

Experimental setup

The input signals are generated by an arbitrary waveform generator (Keysight M8195A) and the output optical signals are detected by a photodetector (Finisar XPDV2120R) with bandwidth of 50 GHz. The electric signals are captured by an oscilloscope (Tektronix DSA72004B). The voltages applied to the thermal phase shifters are provided by the digital-to-analog converter (LTC2688), which is controlled by a field programmable gate array chip (Xilinx 7K325T).

Bandwidth measurement setup

Electro-optic characterization is performed in the telecommunications C-band using a tunable-wavelength laser source (Santec TSL-510). A three-paddle polarization controller is used to ensure transverse-electric mode excitation.

For electro-optic S21 response measurements, a frequency sweeping electrical signal generated from a 110 GHz optical component analyzer (Keysight N4372E) is sent to the EOM with a 50 Ω load. The output optical signal of the EOM is sent back to the input port of the optical component analyzer. A high-speed microwave probes (GGB 110H-GSG-150-DP) is used to deliver the modulation signal to the input port of the transmission line. After calibrating the frequency responses of the probe, and electrical cables, the S21 frequency response of the EOM can be obtained.

Data availability

The data are available as part of the Supplementary files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Azuma, R. T. A survey of augmented reality. Presence: Teleoper. Virtual Environ. 6, 355–385 (1997).

What is XR? Towards a framework for augmented and virtual reality. Comput. Human Behav. 133, 107289 (2022).

Xiong, J., Hsiang, E.-L., He, Z., Zhan, T. & Wu, S.-T. Augmented reality and virtual reality displays: emerging technologies and future perspectives. Light Sci Appl 10, 216 (2021).

Xi, N., Chen, J., Gama, F., Riar, M. & Hamari, J. The challenges of entering the metaverse: An experiment on the effect of extended reality on workload. Inf Syst Front 25, 659–680 (2023).

Dwivedi, Y. K. et al. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 66, 102542 (2022).

Siriwardhana, Y., Porambage, P., Liyanage, M. & Ylianttila, M. A Survey on Mobile Augmented Reality With 5G Mobile Edge Computing: Architectures, Applications, and Technical Aspects. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 23, 1160–1192 (2021).

Glassner, A. S. (ed.) An Introduction to Ray Tracing (Academic Press, 1989).

Shirley, P. Realistic Ray Tracing, Second Edition. (Routledge, Natick, Massachusetts, 2003).

Purcell, T. J., Buck, I., Mark, W. R. & Hanrahan, P. Ray tracing on programmable graphics hardware. in ACM SIGGRAPH 2005 Courses 268-es (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1145/1198555.1198798.

Akenine-Mo¨ller, T., Haines, E. & Hoffman, N. Real-Time Rendering, Fourth Edition. (A K Peters/CRC Press, New York, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1201/b22086.

Clark, J. H. Hierarchical geometric models for visible surface algorithms. Commun. ACM 19, 547–554 (1976).

NVIDIA. Ada Lovelace Architecture. NVIDIA. Available at: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/technologies/ada-architecture/.

Deng, Y., Ni, Y., Li, Z., Mu, S. & Zhang, W. Toward real-time ray tracing: a survey on hardware acceleration and microarchitecture techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. 50, 58:1–58:41 (2017).

Keely, S. Reduced Precision for Hardware Ray Tracing in GPUs. in Eurographics/ ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on High Performance Graphics 12 pages (The Eurographics Association, 2014). https://doi.org/10.2312/HPG.20141091.

Ho, R., Mai, K. W. & Horowitz, M. A. The future of wires. Proc. IEEE 89, 490–504 (2001).

Horowitz, M. 1.1 Computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it). in 2014 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC) 10–14 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISSCC.2014.6757323.

Guo, Q. et al. Femtojoule femtosecond all-optical switching in lithium niobate nanophotonics. Nat. Photon. 16, 625–631 (2022).

Desiatov, B., Shams-Ansari, A., Zhang, M., Wang, C. & Lončar, M. Ultra-low-loss integrated visible photonics using thin-film lithium niobate. Optica, OPTICA 6, 380–384 (2019).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep Learning with Coherent Nanophotonic Circuits. Nature Photon 11, 441–446 (2017).

Chen, Z. et al. Deep learning with coherent VCSEL neural networks. Nat. Photon. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01233-w (2023).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Meng, X. et al. Compact optical convolution processing unit based on multimode interference. Nat Commun 14, 3000 (2023).

Lin, Z. et al. 120 GOPS Photonic tensor core in thin-film lithium niobate for inference and in situ training. Nat Commun 15, 9081 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Optical coherent dot-product chip for sophisticated deep learning regression. Light Sci Appl 10, 221 (2021).

Giamougiannis, G. et al. Neuromorphic silicon photonics with 50 GHz tiled matrix multiplication for deep-learning applications. AP 5, 016004 (2023).

Mohammadi Estakhri, N., Edwards, B. & Engheta, N. Inverse-designed metastructures that solve equations. Science 363, 1333–1338 (2019).

Camacho, M., Edwards, B. & Engheta, N. A single inverse-designed photonic structure that performs parallel computing. Nat Commun 12, 1466 (2021).

Pai, S. et al. Experimental evaluation of digitally verifiable photonic computing for blockchain and cryptocurrency. Optica, OPTICA 10, 552–560 (2023).

Reed, G. T., Mashanovich, G., Gardes, F. Y. & Thomson, D. J. Silicon optical modulators. Nature Photon 4, 518–526 (2010).

Murmann, B. Mixed-signal computing for deep neural network inference. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 29, 3–13 (2021).

Rekhi, A. S. et al. Analog/Mixed-Signal Hardware Error Modeling for Deep Learning Inference. in Proceedings of the 56th Annual Design Automation Conference 2019 1–6 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3316781.3317770.

Boes, A. et al. Lithium niobate photonics: Unlocking the electromagnetic spectrum. Science 379, eabj4396 (2023).

Feng, H. et al. Ultra-high-linearity integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators. Photon. Res., PRJ 10, 2366–2373 (2022).

He, M. et al. High-performance hybrid silicon and lithium niobate Mach–Zehnder modulators for 100 Gbit s−1 and beyond. Nat. Photonics 13, 359–364 (2019).

Feng, H. et al. Integrated lithium niobate microwave photonic processing engine. Nature 627, 80–87 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101–104 (2018).

Zheng, Y. et al. Photonic Neural Network Fabricated on Thin Film Lithium Niobate for High-Fidelity and Power-Efficient Matrix Computation. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.16513 (2024).

Ou, S. et al. Hypermultiplexed integrated photonics–based optical tensor processor. Sci. Adv. 11, eadu0228 (2025).

Hu, Y. et al. Integrated lithium niobate photonic computing circuit based on efficient and high-speed electro-optic conversion. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.02734 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. Integrated electro-optic digital-to-analog link for efficient computing and arbitrary waveform generation. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.04395 (2024).

Mahovsky, J. & Wyvill, B. Fast ray-axis aligned bounding box overlap tests with plucker coordinates. J. Graph. Tools 9, 35–46 (2004).

Shen, M. et al. Photonic link from single-flux-quantum circuits to room temperature. Nat. Photon. 18, 371–378 (2024).

Yan, R. et al. RT engine: an efficient hardware architecture for ray tracing. Appl. Sci. 12, 9599 (2022).

Luke, K. et al. Wafer-scale low-loss lithium niobate photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Express, OE 28, 24452–24458 (2020).

Ren, T. et al. An integrated low-voltage broadband lithium niobate phase modulator. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 31, 889–892 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. Compact slow-light waveguide and modulator on thin-film lithium niobate platform. Nanophotonics 12, 3603–3611 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62425504 to JJD, U21A20511 to JJD), and Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan -Basic Research (2023010201010049 to HLZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.Z. conceived the idea. Z.X.L. fabricated the chip. S.J.Z., H.J.Z., Z.X.L. designed and performed the experiments. S.J.Z., X.Y.J., B.W., H.L.Z. and C.Z. discussed and analyzed data. B.X., Q.Z., Y.H.G. helped in the chip manufacturing process. S.J.Z. prepared the manuscript. J.J.D. revised the paper. J.J.D., J.S.X. and X.L.Z. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Cheng Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., liu, Z., Jiang, X. et al. Thin-film lithium niobate photonic circuit for ray tracing acceleration. Nat Commun 16, 5938 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61234-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61234-x

This article is cited by

-

Multi-target and ultra-high-speed optical wireless communication using a thin-film lithium niobate optical phased array

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Integrated platforms and techniques for photonic neural networks

npj Nanophotonics (2025)