Abstract

The Miocene epoch, marked by significant tectonic and climatic shifts, presents a unique period to study the evolution of South Asian summer monsoon (SASM) dynamics. Previous studies have shown conflicting evidence: wind proxies from the western Arabian Sea suggest a weaker Somali Jet during the Middle Miocene compared to the Late Miocene, while rain-related records indicate increased SASM rainfall. This apparent decoupling of monsoonal winds and rainfall has challenged our understanding of SASM variability. Here, using the fully coupled EC-Earth3 model, we identify a key driver of this decoupling: changes in African topography rather than other external forcings such as CO2 change. Our simulations reveal that changes in Miocene African topography weakened the cross-equatorial Somali Jet and reduced upwelling in the western Arabian Sea, while simultaneously enhancing monsoonal rainfall by inducing atmospheric circulation anomalies over the Arabian Sea. The weakened Somali Jet fostered a positive Indian Ocean Dipole-like warming pattern, further amplifying the monsoonal rainfall through ocean-atmosphere feedbacks. In contrast, CO2 forcing enhances both Somali Jet and rainfall simultaneously, showing no decoupling effect. These findings reconcile the discrepancies between wind and rainfall proxies and highlight the critical role of African topography in shaping the multi-stage evolution of the SASM system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The South Asian summer monsoon (SASM), a major component of the global monsoon system1,2,3, has a strong impact on the Indo-Pacific moisture transport and governs the stability of the present-day Indian Monsoon. Over geological timescales, the strength of the SASM has fluctuated significantly, as evidenced by multiple proxy records. During the Miocene, significant tectonic activity, atmospheric CO2 fluctuations, and environmental changes4,5, influenced monsoon dynamics, drawing considerable interest in the evolution and key drivers of SASM variability6,7.

Marine proxies indicate a major intensification of SASM circulation, particularly the Somali Jet in the western Arabian Sea during the Late Miocene after 8 Ma8,9. However, sediment archives from the western Arabian Sea10,11,12,13 and Maldives archipelago14 suggest that the strengthening of SASM circulation might have commenced as early as the late Middle Miocene (~12.9 Ma). These records link wind-driven coastal upwelling in the western Arabian Sea with low-level tropospheric SASM winds, which drive surface waters offshore, bringing cold, nutrient-rich waters into the euphotic zone and enhancing primary production. Nonetheless, the interpretation of wind-based proxies has been challenged by the emergence of rain-related proxies that present a different perspective on SASM rainfall variability15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Studies of oxygen isotopes (δ18O) from pedogenic carbonates15,16 and mammalian teeth22 from the Siwaliks Hills suggest a decline in SASM rainfall since the Middle Miocene. This decline corresponds with a shift in vegetation from forest ecosystems to grassland-dominated landscapes in South Asia15,22. This reduction in the SASM rainfall after around 12 Ma is further supported by proxies indicating a weakening of chemical weathering and erosion, including decreased K/Al ratios and clastic fluxes into the ocean18. Lower chemical weathering rates and sediment transport imply drier conditions and a weakening of SASM.

Recent studies attribute the SASM circulation and rainfall intensity primarily to the uplift of Himalaya-Tibetan Plateau3,23,24, the expansion of polar ice sheet development25,26 or variations in pCO227 during the Miocene. However, discrepancies between oceanic wind-based records and terrestrial rain-related records suggest that additional boundary forcings contributed to the multi-stage evolution of the SASM system. Reconstructions of Africa’s dynamic topography over the past 30 Ma indicate a gradual uplift of the East African Rift System, including the Ethiopian and the East African plateaus, and the concurrent subsidence of the Congo Basin by up to 500 meters28. Notably, these tectonic changes in Africa aligns with the emergence of a “modern-like” SASM during the late Middle Miocene (~13 Ma)10,11,12,13,14,29. Recent modeling studies further highlight the sensitivity of the SASM to the uplift of the East African Highlands since the Miocene6,7, reinforcing the intricate link between African topography, SASM circulation, and regional rainfall. Despite these insights, the mechanisms underlying the apparent decoupling of Somali Jet and rainfall between the Middle to Late Miocene remain poorly understood. Previous modeling efforts have limited by low-horizontal resolution in atmospheric general circulation models or have overlooked the actual African topography of the Miocene, as well as the oceanic feedbacks induced by topographic changes6,7,30,31,32. These limitations complicate efforts to quantify the role of African topography in SASM evolution.

To address this gap, we investigate the climate response to reconstructed African dynamic topography at ~25 Ma (Late Oligocene; referred to here as Early Miocene simulations), ~15 Ma (Middle Miocene), ~5 Ma (Late Miocene), and present-day (pre-industrial) using a high-resolution configuration of the fully coupled EC-Earth3 model. We also perform sensitivity experiments using a linear baroclinic model (LBM) to identify the dominant mechanisms driving the simulated SASM changes (see Methods and Supplementary Figures for a detailed description). Our results demonstrate that the decoupling of Somali Jet and SASM rainfall is primarily driven by changes in African topography during the Miocene, operating through positive ocean-atmosphere feedbacks.

Results

Miocene African topography changes cause the decoupling of Somali Jet and SASM rainfall

We use the coupled EC-Earth3 model to simulate the response of the SASM to changes in African topography since the Miocene (see Methods). The model successfully replicates the present-day SASM system, which is characterized by a strong cross-equatorial Somali Jet over the Arabian Sea and increased rainfall over the Indian subcontinent during boreal summer (June to August) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Due to the Coriolis force, the climatological southwesterly summer monsoon winds over the Arabian Sea can drive strong ocean upwelling along the coastal region (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). The agreement between our pre-industrial simulation and contemporary observations validates the use of EC-Earth3 for exploring the influence of the African topography on the SASM.

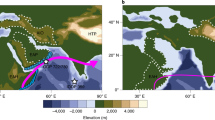

Our simulations reveal a notable decoupling of the cross-equatorial Somali Jet and rainfall from Middle Miocene to the present-day in response to changes in African topography. The Miocene epoch was characterized by substantial tectonic activity, especially within the East African Rift System (EARS). Reconstructions of Africa’s dynamic topography over the past 30 Ma28 indicate a gradual uplift of the EARS, including the Ethiopian and the East African plateaus, and subsidence of the Congo Basin by up to 500 meters (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Fig. 2). Our simulations show a significant weakening of the meridional cross-equatorial flow of the Somali Jet (Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. 3), with reductions of 0.36 m s-1 and 0.22 m s-1 in the Early and Middle Miocene, respectively, compared to the present-day (Fig. 1g). These findings are largely in agreement with previous modeling studies31,32,33.

Reconstructed African Miocene topography (m) for (a) Early Miocene, (b) Middle Miocene and (c) Late Miocene, based on the paleo-topography map from ref. 28. Changes in rainfall (shading, mm day-1) and low-level atmospheric circulation at 700 hPa (vectors, m s-1) in the (d) MT25, (e) MT15 and f MT05 simulations relative to the pre-industrial simulations. In (d–f) gray stippling and vectors denote regions in which the changes are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test. And the solid black boxes mark the SASM region (5° N-30° N, 60° -95° E), and the red asterisks or boxes denote the locations of the proxy records in (i−o). The red bold vectors in (d) and (e) indicate the cyclonic/anticyclonic circulation anomalies. The changes in (g) intensity of Somali Jet (m s-1) and western Arabian Sea upwelling (cm day-1), and (h) ratios of SASM rainfall (%), with asterisks above or below the bars denoting changes that are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test. The solid blue boxes (10° S–10° N, 40° −50° E) and solid purple boxes (15° −21° N, 54° −62° E) in (d−f) are used to define the intensity of Somali Jet and western Arabian Sea upwelling, respectively (see Methods). i Total organic carbon (TOC, wt%) values from ODP Sites 722B, 728B, 730 A, and 731A10,11. j Planktic foraminifer Globigerina bulloides (G. bulloides; %) from ODP 722B11 and 730A9. k δ13C (PDB) of paleosol carbonate (‰) from the Potwar Plateau15 and NW India87. l δ18O (PDB) of soil carbonate (‰) from the Potwar Plateau15. m Chemical weathering proxies (CIA, %) from the Indus Marine A-1 well in the northern Arabian Sea20. n Kaolinite/chlorite ratio from IODP Site U1447 in the western Andaman Sea21 and K/Al ratio from ODP Site 718 in the Bengal fan20. o Total sediment flux into the Indus fan (103 km3 Ma-1)19. The vertical shaded areas in (i−o) represent the time intervals of Middle Miocene Climate Optimum (MMCO, ~15 Ma) and Late Miocene (~5 Ma).

Accompanied by the weakened Somali Jet, upwelling in the western Arabian Sea is significantly reduced in the Early and Middle Miocene (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 4). This simulated upwelling change aligns with wind-based proxy records (see Methods), which indicate a weakening Somali Jet-induced oceanic upwelling in the western Arabian Sea during the Middle Miocene compared to Late Miocene (Fig. 1i, j). However, recent publication has advanced our knowledge that the weakening of upwelling is more complex than a simple reduction in wind strength and is attributed to changes in both the intensity and structure of the Somali Jet34. Specifically, while the jet weakens in its core, low-level tropospheric winds strengthen along the western Arabian Peninsula (Supplementary Fig. 3). This altered wind pattern decreases the wind-stress curl along the western Arabian Sea coast34,35,36, where the proxy sites are located, resulting in negative Ekman pumping and weaker upwelling (Supplementary Fig. 4).

In present-day climate, the East African topography acts as a barrier that channels the easterly Somali Jet, yielding intense rainfall over the Indian subcontinent. Given the established relationship between the Somali Jet and SASM rainfall, one would expect the topography-induced weakening of the Somali Jet to result in reduced SASM rainfall due to decreased moisture transport37. However, our results indicate a spatially coherent increase in summer rainfall, with the maxima in the northeast of the Indian subcontinent and south of the Western Ghats region during the Early and Middle Miocene (Fig. 1d, e). Specifically, SASM rainfall increases by 15% and 9% during the Early and Middle Miocene, respectively, compared to the present-day (Fig. 1h). This simulated increase in SASM rainfall is consistent with qualitative rainfall-based proxies for the Miocene (see Methods), which suggest more humid conditions over the South Asia during the Middle Miocene compared to the Late Miocene (Fig. 1k–o).

Our experiments successfully reproduce the major observational features of Somali Jet-induced upwelling and monsoon rainfall decoupling from Middle to Late Miocene, as seen in proxy records. This highlights the significant role of altered African topography in modulating the SASM system during the Miocene, offering a previously unrecognized explanation for the observed discrepancies between wind-based and rainfall-based proxy reconstructions.

During the boreal summer, the East African Highlands act as a major topographic barrier, redirecting low-level easterly winds over the Southern Indian Ocean across the equator, forming the southwesterly Somali Jet38 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Numerous idealized modeling studies have demonstrated that removing or lowering the East African Highlands allows easterly winds south of the equator to penetrate further inland over Africa, creating a broader, less concentrated cross-equatorial flow, rather than channeling it into a strong Somali Jet31,32,33.

Our simulations support this mechanism, showing a significant weakening of the core of Somali Jet in response to the lowered East African Highlands during the Miocene (Fig. 1, Fig. 2a, d, g, and Supplementary Fig. 3). This highlights the critical role of reduced topographical blocking in weakening the cross-equatorial Somali Jet, consistent with previous modeling studies6,31,32,33. Consequently, the weakened Somali Jet during the Early and Middle Miocene results in a marked downwelling motion anomaly along the coast of East Africa (Fig. 2c, f). This would have reduced coastal upwelling and primary productivity39, affecting wind-based proxies such as TOC and G. bulloides in the western Arabian Sea (Fig. 1).

Changes in meridional wind at the equator (shading, m s-1) in the (a) MT25, (d) MT15 and (g) MT05 simulations compared to pre-industrial simulations, overlaid with their corresponding climatological means in pre-industrial simulations (contours; solid lines represent positive values). Black shading in (a−g) indicates African topography in Early Miocene, Middle Miocene and Late Miocene, respectively. b−h Same as (a−g) but for changes in sea surface temperature (SST; shading, °C), sea level pressure [contours; hPa; solid (dashed) lines represent the positive (negative) values], and 1000-hPa wind (vectors, m s-1). Gray stippling in (a–i) and vectors in (b−h) denote regions in which the changes are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test. c−i Same as (a−g) but for the changes in meridional averaged (10° S-5° N) ocean subsurface temperature (shading, °C), ocean vertical velocity [contours; cm s-1; solid (dashed) lines represent the upward (downward) motion], and thermocline represented by 23 °C isotherm [black (red) line indicates the thermocline in the pre-industrial (Miocene) simulation]. Vertical red and blue vector in (c) and (f) represent ocean upwelling and downwelling anomalies, respectively.

Dynamic effects induced by atmospheric circulation anomalies control the changes in SASM rainfall

The significant increase in SASM rainfall during the Early and Middle Miocene, despite the weakened Somali Jet, is primarily associated with anomalous cyclonic circulation over Arabian Sea and an anticyclonic pattern over the Bay of Bengal (red bold vectors in Fig. 1d, e). These circulation patterns enhance meridional moisture transport from the tropical Indian Ocean to the SASM region (Supplementary Fig. 5), providing a dynamic explanation for the increased precipitation.

This hypothesis is further confirmed by a linearized moisture budget analysis (see Methods). The moisture budget decomposition reveals that the combined thermodynamic and dynamic terms (Supplementary Fig. 6a, d and g) effectively capture the primary characteristics of SASM rainfall changes during the Early, Middle and Late Miocene (Fig. 1d–f), with pattern correlation coefficients of 0.90, 0.88, and 0.67, respectively. The increased SASM rainfall is mainly driven by dynamic effects resulting from changes in atmospheric circulation (Supplementary Fig. 6c, f and i), particularly during the Early and Middle Miocene, whereas the thermodynamic effects due to atmospheric moisture changes are negligible (Supplementary Fig. 6b, e, and h). It is important to note that this dynamic response does not contradict the hypothesis of a decoupling between monsoon winds and rainfall, but rather provides a mechanistic explanation for how SASM rainfall increased despite a weaker Somali Jet, emphasizing the importance of atmospheric circulation changes and ocean-atmosphere feedbacks in modulating the SASM system.

The analysis indicates that cyclonic and anticyclonic circulation anomalies over the northern Indian Ocean are the key drivers of increased SASM rainfall during these periods (Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. 5). This raises a critical question: how do changes in African topography induce these atmospheric circulation anomalies that, in turn, affect the SASM rainfall? The following section explores the role of ocean- atmosphere interaction in this process.

Increased SASM rainfall due to direct atmospheric processes

The anomalous cyclonic circulation over the Arabian Sea in the low-level troposphere is directly linked to a significant reduction in summer rainfall over tropical central Africa. During boreal summer, prevailing southwesterly monsoonal winds transport moisture from the tropical Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Guinea into central Africa, sustaining regional rainfall (Supplementary Fig. 7a). However, during the Early to Middle Miocene, large-scale tectonic uplift over the East African Highlands likely resulted in a higher elevation of the Congo basin (Fig. 1a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 2). This elevated topography acted as a barrier, reducing moisture transport from the Atlantic Ocean into central Africa, and resulting in a notable decrease in atmospheric water vapor (Supplementary Fig. 7b and f).

The resulting weakening of the West African summer monsoon causes significantly reduced rainfall over central Africa (Fig. 1d, e). This drying trend is further supported by enhanced descending air anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 7c and g) and a substantial reduction in latent heat release in the region (Supplementary Fig. 7d and h). Additionally, surface warming anomalies over central Africa (likely due to suppressed convection) and increased surface pressure indicate the presence of subsidence driven atmospheric stability (Supplementary Fig. 7e and i). These conditions likely triggered a Kelvin wave response, generating westerly wind anomalies over the tropical Indian Ocean40, which gradually weakened toward the northern Indian Ocean, thereby reinforcing cyclonic circulation in the low-level troposphere (Fig. 1d, e).

To confirm that suppressed precipitation over tropical central Africa could enhance SASM rainfall via atmosphere dynamics, we conducted an experiment using an LBM with prescribed cooling over tropical central Africa (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 8a). According to Gill’s theory41, localized atmospheric heating and cooling anomalies generate distinct wave responses in the tropics, where Rossby waves propagate westward and Kelvin waves propagate eastward. While Kelvin waves are strongest near the equator (~10° S–10° N), their influence can extend up to ~20° N, depending on the structure and strength of the forcing40. Our LBM experiment demonstrates that suppressed convection over North-Central Africa induces a cooling anomaly, triggering a Kelvin wave response with westerly wind anomalies over the tropical Indian Ocean. This result is consistent with a previous study40. Furthermore, maximum wind speeds are found north of the equator, decreasing with latitude in the northern Indian Ocean, this favors the establishment of a cyclonic circulation over the Arabian Sea, which enhances moisture transport into the SASM region, increasing local rainfall.

However, it is worth noting that the simulated cyclonic circulation in the LBM experiment is positioned slightly northward compared to the EC-Earth simulations. This discrepancy suggests the involvement of additional mechanisms, such as a positive precipitation-atmosphere feedback and the impact of a weakened Somali Jet. To investigate this further, we performed another set of LBM experiments with prescribed heating over the SASM region (see Methods). These experiments show that enhanced SASM rainfall can trigger a Rossby wave response over its northwestern region (Supplementary Fig. 8b), which further enhances cyclonic circulation over the Arabian Sea, highlighting the role of positive precipitation-atmosphere feedback. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the Somali Jet weakens significantly when the East African Highlands are lowered during the Early and Middle Miocene. This reinforces northerly wind anomalies over the western Arabian Sea, shifting the cyclonic circulation further south compared to its position in the LBM experiment results. This displacement of the cyclonic anomaly is a direct result of the altered Somali Jet structure, further confirming the significant role of African topography in modulating the SASM system during the Miocene.

Increased SASM rainfall due to indirect ocean-atmosphere feedbacks

The increased SASM rainfall during the Miocene was further amplified by the weakened Somali Jet through positive ocean-atmosphere feedback mechanisms. Figure 2 shows how the weakened Somali Jet induces a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)-like warming pattern during the Miocene. The pressure-longitude cross section at the equator shows that lower East African Highlands during the Miocene led to northerly wind anomalies along the East African coast, weakening the climatological southwesterlies summer monsoon circulation (Fig. 2a, d). This weakening, in turn, reduced ocean upwelling along the East African coast, leading to anomalously warming SSTs in the western Indian Ocean (Fig. 2b, e and Supplementary Fig. 9). This warming of the western Indian Ocean lowers sea level pressure (SLP), reinforcing easterly wind anomalies along the equator, which enhance ocean cooling in the eastern Indian Ocean (Fig. 2b, e). These processes are further supported by their seasonal variation (Supplementary Fig. 9). Specifically, warm SST anomalies develop in the western equatorial Indian Ocean by June, accompanied by significant easterly wind anomalies extending from the west to central Indian Ocean. In the following months, this warming intensifies, with easterly wind anomalies migrate further eastward, while the southeastern tropical Indian Ocean begins to cool. These processes are particularly pronounced in the Early and Middle Miocene when the East African Highlands were much lower compared to the Late Miocene (Supplementary Fig. 10).

According to ocean-atmosphere coupling theory42, these anomalous easterly winds enhance downwelling in the western Indian ocean and upwelling along the Java and Sumatra coasts in eastern Indian Ocean43,44,45 (Fig. 2c, f). Simultaneously, the thermocline deepens in the equatorial western Indian Ocean while becoming shallower in the eastern Indian Ocean, producing a dipole-like temperature pattern characterized by a “warm West and cold East” structure, indicating a positive IOD-like warming pattern43,44,45,46 (Fig. 2c, f). It is important to note that during the Late Miocene, African topography was similar to present-day, resulting in minimal changes in the Somali Jet and Indian Ocean dynamics (Fig. 2g–i). This supports the conclusion that changes in Somali Jet plays a critical role in controlling Indian Ocean dynamics on geological timescales.

The positive IOD-like warming pattern induced by the weakened Somali Jet during the Early and Middle Miocene, further increases SASM rainfall through atmosphere dynamics. Specifically, the reduced gradient of zonal SLP over the Indian Ocean caused by the IOD-like warming pattern leads to a weakened Indian Ocean Walker circulation45, featuring anomalously descending motion over the eastern Indian Ocean and ascending motion over the western Indian Ocean (Fig. 3a, c). This anomalous atmospheric circulation results in reduced latent heat release due to suppressed precipitation over the eastern Indian Ocean, which in turn triggers a Rossby wave response with an anticyclonic circulation pattern over the Bay of Bengal40,41,47,48 (red bold vectors in Fig. 3b, d). Consequently, enhanced southerly winds transport more moisture away from the tropical ocean as a part of the large-scale anticyclonic flow over the Bay of Bengal, further contributing to increased rainfall (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Changes in vertical velocity (shading, -10-2 Pa s-1; the positive values indicate upward velocity) in the (a) MT25, (c) MT15 and (e) MT05 simulations relative to pre-industrial simulations, overlaid with the climatological mean of meridional (m s-1) and vertical wind (vectors) in pre-industrial simulations. b−f Same as (a−e) but for changes in moisture condensation (QL; shading; 10-2 m2 s-3; see Methods for details) at 500 hPa and horizontal wind at low-level troposphere (m s-1; averaged from 925 hPa to 700 hPa). Vertical red and blue vector in (a and c) represent anomalous upward and downward motion, respectively. Red bold vectors in (b and d) indicate the anomalous anticyclonic circulation. Solid boxes in (b, d and f) mark the South Asian summer monsoon (SASM) region. Only winds >0.2 m/s are shown. Gray stippling in (a−f) and vectors in (b−f) denote regions in which the changes are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

To further investigate the impact of suppressed convection over the eastern Indian Ocean on SASM rainfall, we designed an LBM experiment with prescribed cooling over the eastern Indian Ocean (see Methods). Consistent with Gill’s theory41, cooling in the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean produces a pair of anticyclones in the off-equatorial region, resulting in the equatorial easterly wind anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 8c). This sustains and strengthens positive IOD-like warming anomalies. The LBM experiment supports our EC-Earth simulation results, indicating that the anomalous cyclonic circulation over the Bay of Bengal also contributes to increased SASM rainfall by reinforcing positive ocean-atmosphere feedbacks.

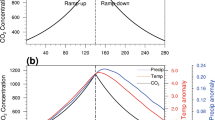

The effects of the pCO2 forcing show no decoupling effect

The Miocene period was generally warmer than today5, particularly during the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (~15 Ma), largely due to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations4 (Fig. 4a). However, multi-proxy estimates of atmospheric CO2 during this period remain highly uncertain49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68 (Fig. 4a), making it difficult to precisely assess the role of pCO2 in SASM changes. To determine whether the SASM response to African topography changes depends on variations in CO2 concentration, we conducted sensitivity experiments using the EC-Earth3 model (see Methods).

a Multi-proxy atmospheric CO2 levels (p.p.m.v) compiled from previous literature, including stomata49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 (black circles), δ13C of alkenones60,61,62,63 (red triangles) and marine boron60,62,64,65,66,67,68 (black crosses). Changes in rainfall (shading, mm day-1) and 700 hPa wind (vectors, m s-1) in the (b) MC25, (c) MC15 and (d) MC05 simulations relative to the MT25, MT15 and MT05 simulations, respectively. In (b–d) gray stippling and vectors denote regions in which the changes are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test, and the solid boxes mark the South Asian summer monsoon (SASM) region. e Area-averaged changes in Somali Jet intensity (m s-1; see Methods) and ratios of summer rainfall (%) over the SASM region due to increased CO2 concentration in (b–d) with asterisks above the bars denoting changes that are significant at the 95% confidence level according to Student’s t-test.

Unlike the decoupling of Somali Jet and SASM rainfall observed in experiments driven by changes in African topography, our simulations with elevated CO2 consistently produce both an enhanced Somali Jet and increased SASM rainfall (Fig. 4), demonstrating no decoupling effect. The increase in SASM rainfall due to increased CO2 concentration (Fig. 4b–d) aligns with previous studies, highlighting the role of increased atmospheric moisture in response to global warming69,70,71,72. This follows the “wetter-gets-wetter” mechanism71,73, whereby warmer temperatures intensify moisture availability in already humid regions. As expected, the rise in surface air temperature due to higher CO2 level leads to increased atmospheric moisture content (Supplementary Fig. 11a), consistent with the Clausius-Clapeyron relation71. Thus, while changes in African topography affect SASM rainfall through dynamic circulation anomalies, CO2 forcing primarily drives rainfall changes via thermodynamic effects (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Notably, uncertainties in pCO2 estimates do not significantly alter the SASM circulation response to African topography changes during the Miocene. Simulations that combine CO2 forcing and African topography changes (see Methods) show clear cyclonic and anticyclonic atmospheric circulations over the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 12). This pattern is similar to the atmospheric circulation anomalies due to African topography changes (Fig. 1d, e), indicating that SASM circulation changes during the Miocene are mainly controlled by the African topography rather than pCO2 levels. Furthermore, the decoupling of Somali Jet and SASM rainfall—characterized by a weakened Somali Jet alongside increased SASM rainfall—is also evident in these combined simulations. This reinforces the conclusion that African topography played a dominant role in shaping the evolution of the SASM during the Miocene, whereas CO2 forcing alone is insufficient to drive the observed decoupling.

Discussion

We investigated the hydroclimate over the SASM region using the fully coupled EC-Earth3 model, constrained by reconstructed African topography at three key time slices across the Miocene. Our findings reveal that African topography changes played a crucial role in driving the decoupling of a weakened Somali Jet and increased SASM rainfall, while CO2 changes primarily affected the thermodynamic response. The key processes are summarized in Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism for (a) the effect of Miocene African topography changes on increased South Asian summer monsoon (SASM) rainfall through direct atmospheric processes, and (b) the effect of weakened Somali Jet on increased SASM rainfall through indirect oceanic processes.

During the Early and Middle Miocene, significant African topography changes directly weakened and altered the structure of the cross-equatorial Somali Jet, while also suppressing convection over tropical central Africa. These changes triggered an anomalous cyclonic circulation in the low-level troposphere over the Arabian Sea, enhancing moisture transport from the tropical Indian Ocean to the SASM region, thereby increasing local monsoonal rainfall (Fig. 5a). Additionally, the weakened Somali Jet contributes to the establishment of a positive IOD-like warming pattern, resulting in a weakened Indian Ocean Walker circulation (Fig. 5b). This weakened large-scale atmospheric circulation in the tropics further suppresses convection over the eastern Indian Ocean, triggering anticyclonic circulation in the low-level troposphere over the Bay of Bengal, enhancing the meridional moisture convergence in SASM region and increasing rainfall (Fig. 5b).

The primary contribution of our study is the identification of a previously overlooked tectonic mechanism that drives the decoupling of Somali Jet and SASM rainfall during the Miocene. Unlike previous studies that primarily attribute SASM evolution to the changes in land/ocean configuration74,75, changes in polar ice sheet development25,26, changes in ocean gateways23,76, closure of the Tethys Seaway13,74,77, and uplift of Himalaya-Tibetan and other regions6,7,24, our results provide compelling evidence that African topography changes were a dominant driver of SASM evolution.

Our high-resolution EC-Earth simulations reconcile contradictory proxy evidence, resolving the discrepancy between wind-based proxies in the Arabian Sea and rain-related proxies over the Indian continent and nearby Indian Ocean for SASM changes from the Middle to Late Miocene. This is the first study to provide a comprehensive dynamical explanation of this decoupling phenomenon using a state-of-the-art coupled climate model, highlighting the importance of accurately reconstructing the timing and magnitude of African topographic changes when interpreting past monsoon evolution. Moreover, as climate models project significant changes in precipitation over Africa due to global warming, similar latent heat-induced atmospheric circulation changes could influence future SASM dynamics. This raises the possibility that a decoupling of the Somali Jet and monsoonal rainfall could occur again in a warming world, with potential consequences for regional hydroclimate, monsoon predictability, and water resource management in South Asia.

Methods

EC-Earth3 model and simulations

The EC-Earth3 is a fully coupled Earth system model developed by a consortium of European research institutions78, contributing to the Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) efforts79,80,81. It has been widely used to explore the climate dynamics of past, present and future72,79,82. The EC-Earth model incorporates various state-of-the-art components, including atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, land and biosphere. The atmospheric component is the Integrated Forecast System (IFS, version cycle 36r4) model from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), including the land surface hydrology (H-TESSEL) model. The ocean component is the Nucleus for European Modelling of the Ocean (NEMO) version 3.683, which is coupled with a sea ice model (LIM3), and the biogeochemical model PISCES. EC-Earth3 also incorporates the dynamic vegetation component from the Lund-Postsdam-Jena General Ecosystem Simulator (LPJ-GUESS). Detailed descriptions of the EC-Earth3 have been introduced previously79.

In this study, we use model configurations EC-Earth3-veg (standard CMIP6 model name), with coupled dynamic vegetation model. The atmosphere component IFS has a resolution of T255 spherical grid in the horizontal (~0.7°, 85 km) and 91 levels in the vertical; the resolution of the ocean model is ORCA1L75, representing ~1° in the horizontal, and 75 layers in the vertical.

We conducted seven sensitivity experiments to investigate the roles of the African topography and pCO2 in shaping the Miocene climate. Due to computational limitations, transient simulations covering the entire Miocene are not feasible, so we focus on three key time slices representing different stage of African topography change. In addition to a pre-industrial experiment (PI) with modern topography and a CO2 concentration of 284 p.p.m.v., we performed three experiments based on the PI setup, incorporating the African topography changes during the Early Miocene (Oligocene-Miocene transition around 25 Ma ago; MT25), Middle Miocene [Middle Miocene Climate Optimum (MMCO) around 15 Ma ago, MT15], and Late Miocene (Miocene-Pliocene transition around 5 Ma ago, MT05). The African topography details during the Miocene are set according to the geological maps from ref. 28, which reconstructs the evolution of dynamic topography of Africa over the past 30 Ma.

Furthermore, we conducted three additional experiments to clarify the relative impact of high CO2 on SASM rainfall compared to African topography changes. In these experiments, CO2 concentrations are set to 500 p.p.m.v. with African topography in Early, Middle and Late Miocene, referred to as MC25, MC15 and MC05, respectively. Orbital forcing was not considered, and all simulations were run with pre-industrial orbital settings (longitude of perihelion = 100.33, obliquity = 23.549, eccentricity = 0.016764). Thus, climate anomalies due to African topography changes are represented by the difference between the MT25/MT15/MT05 experiments and the PI experiment. The response of SASM changes to higher CO2 concentrations is denoted by the comparisons between the MC25 and MT25, MC15 and MT15, or MC05 and MT05. The combined effects of African topography changes and elevated CO2 levels are indicated by the differences between MC25/MC15/MC05 and PI experiment.

Supplementary Table 1 provides an overview of experiments, detailing the corresponding topography and pCO2 values. The pre-industrial simulation was run for 1000 model years to ensure equilibrium, while the other experiments were run for 200 model years. Since all simulations reach quasi-equilibrium during the last 100 years, with the trend in mean global surface temperature being <0.005 K, the last 100 years of each simulation are used for analysis.

Definition of South Asian summer monsoon metrics

The South Asian summer monsoon (SASM) region is defined as the area spanning 5° N-30° N, 60° E−95° E84,85. This study focuses on the boreal summer months from June to August, unless otherwise specified. Including May and/or September in the summer season does not significantly alter the results. The intensity of SASM rainfall is measured by averaging summer rainfall over SASM domain. The variation in the Somali Jet significantly impacts the SASM rainfall and produces notable oceanic features in the western Arabian Sea. During summer, these winds force upwelling of colder waters along the coasts of Oman and Somalia, increasing nutrient levels and sustaining distinct floral and faunal groups9. Due to the relationship between the Somali Jet, SASM rainfall, and ocean circulation, the Somali Jet is often used to measure the strength of SASM circulation, especially in the paleoclimate research8,9,10,11,12,13. In this study, the intensity of Somali Jet is defined as the wind speed at 850 hPa averaged over the region of 10° S–10° N, 40°−50° E during summer32,86. In addition, the intensity of western Arabian Sea upwelling is defined as the average vertical velocity of the surface ocean (0−100 m) over the western Arabian Sea (15°–21° N, 54°–62° E)36.

Proxy-model comparison

The proxy records reflecting the Somali Jet and humid conditions over South Asia during the Miocene are collected based on previous studies9,10,11,15,16,17,19,20,21,87. Total organic carbon (TOC) values and Planktic foraminifer Globigerina bulloides (G. bulloides)10,11 are widely used to estimate the SASM wind intensity, as they predominantly reflect wind-driven oceanic upwelling and primary production in the western Arabian Sea. Both the TOC and G. bulloides values from the western Arabian Sea are lower during the Middle Miocene compared to the Late Miocene9,10,11 (Fig. 1i, j), suggesting weakened SASM winds-induced oceanic upwelling in the western Arabian Sea during the Middle Miocene. Our African topography experiments can capture this feature in the wind-based proxies, showing significant weakened upwelling in the western Arabian Sea, particular in the MT25 and MT15 simulations compared to the pre-industrial simulation (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 4). We found that this weakened upwelling induced by African topography changes is due to the changes in both the strength and structure of Somali Jet (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 4), indicating the complex changes in Arabian Sea upwelling34,35,36.

In contrast, these wind-based proxies are challenged by rainfall-related proxies. For example, δ13C values in paleosols provide a direct measure of the relative contribution of grasses (C4 plants) and woodland or/and forest (C3 plants) to former vegetation, with C4 grasses favoring drier environment and C3 plants favoring moister environment. δ13C in paleosols from Siwalik Group sediments15,87 is relatively depleted before 7 Ma and more enriched after 7 Ma (Fig. 1k), suggesting that C3 trees dominated in the Middle Miocene while C4 grasses became more prevalent in the Late Miocene16,17. The δ18O of pedogenic carbonate from the Indian Siwalik sequences also indicates decreased rainfall in the Late Miocene15,16,17, coinciding with the rise of C4 plants (Fig. 1l). This indicates a hydroclimatic change that might have played a crucial role in the transition from C3 to C4 vegetation. Our simulations also capture this forest-to-grassland transition, showing less tree coverage and more grass coverage across the Indian continent and Himalayan foreland during the Late Miocene than those in the Early and Middle Miocene (Supplementary Fig. 13). Thus, our results suggest that the dramatic aridification of the Indian continent from the Middle and Late Miocene, driven by changes in African topography, may have been a key mechanism behind the expansion of C4 plants. This hypothesis is supported by other rainfall-related proxies. Reconstructions of chemical weathering and erosion budgets indicate that faster erosion, associated with more humid and warm climates in the Early to Middle Miocene, transitioned to less erosive and drier climates in the Late Miocene19,20,21 (Fig. 1m–o).

All these qualitative climate proxies for the Miocene, derived from various sources and locations, generally indicate weakened SASM-induced Arabian Sea upwelling and more humid conditions over South Asia during the Middle Miocene compared to the Late Miocene. This significant feature is well captured by our African topography experiments (Fig. 1d–h).

However, there are some uncertainties in proxy records that should be noted. For instance, while δ18O of soil carbonates is often interpreted as a precipitation proxy, it is also influenced by other factors, such as moisture source variability, wind system shifts, and temperature variations88. As for the wind proxies in western Arabian Sea, such as TOC and G. bulloides records, considered as indicators of monsoon winds, can also be influenced by local oceanographic processes and thermocline variability, adding complexity to their interpretation36. Additionally, most proxies come from specific regions (e.g., Arabian Sea, Siwaliks Hills), which may not fully capture spatial monsoon variability. Despite these uncertainties, the consistent multi-proxy changes support the conclusion that these proxies reliably reflect SASM evolution during the Miocene.

Wind-driven upwelling

The monsoon wind can induce ocean upwelling through “Ekman pumping” caused by wind-stress curl36,89. In this study, we calculate the Ekman pumping velocity using monthly wind stress data as follow:

where \({\rho }_{w}\) is seawater density (1024 kg m-3), \(f\) is the Coriolis parameter, and \(\nabla \times {{\rm{\tau }}}\) is the wind-stress curl.

Latent heat of condensation

In this study, the latent heat of condensation (QL)90,91 is calculated to reveal the anomalous atmospheric cooling due to significant rainfall decrease. The formula of QL is as follows:

where L, ω, \({q}_{s}\), and p indicates the latent heat of condensation, vertical velocity, saturation specific humidity, and pressure, respectively.

Decomposed atmospheric moisture budget

The atmospheric moisture budget is a widely used analysis to reveal the dominant process controlling the rainfall changes69,73,92, which can be written as:

where P, ω, q, p, V, and E denotes the precipitation, vertical velocity, specific humidity, pressure, and evaporation, respectively. The overbars represent the climatological mean in pre-industrial conditions, and the primes indicate deviations from this mean in sensitive experiments. The symbol \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle\) indicates the vertical integration, and the Residual term includes the transient eddy and surface boundary effects. For tropical rainfall anomalies, previous studies indicate that the contributions of advection (\(\left\langle {{\rm{V}}}\cdot \nabla q\right\rangle ^{\prime}\)), evaporation (\(E^{\prime}\)) and Residual terms are relatively negligible70,93. Hence, Eq. (3) can be simplified as follows70,72,85:

where the ω500 represent the vertical velocity at 500 hPa, and Prw is the vertical integrated atmospheric moisture through the column. Based on the simplified moisture budget equation, changes in SASM rainfall (\(P^{\prime}\)) can be decomposed into the effects of atmospheric moisture changes (thermodynamic term; δTh) and the atmospheric circulation change (dynamic term; δDy). Therefore, in this study, the sum of the δTh and δDy can be roughly considered as the diagnosed changes in summer rainfall over the SASM region.

LBM experiments

Compared to the complex Earth System models, the linear baroclinic model (LBM)94 includes only linear processes, providing a more accurate investigation of the atmospheric response to diabatic heating or cooling95,96. To verify the impact of significantly suppressed convection over tropical central Africa and the equatorial eastern Indian Ocean on SASM rainfall, we performed four LBM experiments based on climatological summer mean of the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) reanalysis from 1980-2010, using a time integration method for 40 days. Perturbations from the basic state are regarded as the linear response to the forcing. We used an LBM version with 20 vertical sigma levels and a horizontal resolution of T21, taking the last 10 days as the steady-state solution.

In experiment 1 (Exp_1), we prescribe the idealized cooling in tropical central Africa (5° S-15° N; 20°-40° E) with a vertical profile following a gamma function, peaking at a cooling rate of 6 to 7 K day-1 at about 450 hPa, based on climatology from June to August (ref. 95). Experiments 2 (Exp_2) and 3 (Exp_3) follow the same methodology as in Exp_1, but applied heating over SASM region (5°-30° N; 60°-95° E) and cooling over tropical eastern Indian Ocean (5° S-5° N; 90°-110° E), respectively. Exp_4 combined diabatic cooling over tropical central Africa and eastern Indian ocean, and heating over SASM region. Indeed, Exp_4 (Supplementary Fig. 7d) reproduced the cyclonic and anticyclonic circulation anomalies over the northern Indian Ocean observed in fully coupled EC-Earth3 simulations (Fig. 1d, e), suggesting that suppressed rainfall in the tropics plays a crucial role in driving large-scale atmospheric circulation anomalies.

Data availability

The GPCPv2.3 data from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project is available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html. NCEP2 data is downloaded from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html. Source data underlying the main figures are provided with this paper on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15663883.

Code availability

All Figures in this article are produced by the NCAR Command Language (Version 6.4.0)97, and the source codes for the main results are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15663846.

References

Goswami, B. N., Krishnamurthy, V. & Annmalai, H. A broad-scale circulation index for the interannual variability of the Indian summer monsoon. Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 125, 611–633 (1999).

Kumar, K. K., Rajagopalan, B., Hoerling, M., Bates, G. & Cane, M. Unraveling the mystery of indian monsoon failure during El niño. Science 314, 115–119 (2006).

An, Z. S., Kutzbach, J. E., Prell, W. L. & Porter, S. C. Evolution of Asian monsoons and phased uplift of the Himalaya–Tibetan plateau since Late Miocene times. Nature 411, 62–66 (2001).

Burls, N. J. et al. Simulating miocene warmth: insights from an opportunistic multi-model ensemble (MioMIP1). Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004054 (2021).

Steinthorsdottir, M. et al. The miocene: the future of the past. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004037 (2021).

Sarr, A.-C. et al. Neogene South Asian monsoon rainfall and wind histories diverged due to topographic effects. Nat. Geosci. 15, 314–319 (2022).

Zuo, M. et al. South Asian summer monsoon enhanced by the uplift of Iranian Plateau in Middle Miocene. Clim. Past 20, 1817–1836 (2024).

Prell, W. L., Murray, D. W., Clemens, S. C. & Anderson, D. M. Evolution and variability of the indian ocean summer monsoon: evidence from the western arabian sea drilling program. In Synthesis of Results from Scientific Drilling in the Indian Ocean 447–469 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 1992).

Kroon, D., Steens, T. & Troelstra, S. R. Onset of monsoonal related upwelling in the western Arabian sea as revealed by planktonic foraminifers 1. In Proceedings Of The Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results 257–263 (1991).

Huang, Y., Clemens, S. C., Liu, W., Wang, Y. & Prell, W. L. Large-scale hydrological change drove the late Miocene C4 plant expansion in the Himalayan foreland and Arabian Peninsula. Geology 35, 531 (2007).

Gupta, A. K., Yuvaraja, A., Prakasam, M., Clemens, S. C. & Velu, A. Evolution of the South Asian monsoon wind system since the late middle Miocene. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 438, 160–167 (2015).

Zhuang, G., Pagani, M. & Zhang, Y. G. Monsoonal upwelling in the western Arabian Sea since the middle Miocene. Geology 45, 655–658 (2017).

Bialik, O. M. et al. Monsoons, upwelling, and the deoxygenation of the northwestern indian ocean in response to middle to late miocene global climatic shifts. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 35, e2019PA003762 (2020).

Betzler, C. et al. The abrupt onset of the modern South Asian Monsoon winds. Sci. Rep. 6, 29838 (2016).

Quade, J., Cerling, T. E. & Bowman, J. R. Development of Asian monsoon revealed by marked ecological shift during the latest Miocene in northern Pakistan. Nature 342, 163–166 (1989).

Quade, J. & Cerling, T. E. Expansion of C4 grasses in the late Miocene of Northern Pakistan: evidence from stable isotopes in paleosols. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 115, 91–116 (1995).

Quade, J., Cater, J. M. L., Ojha, T. P., Adam, J. & Mark Harrison, T. Late Miocene environmental change in Nepal and the northern Indian subcontinent: stable isotopic evidence from paleosols. GSA Bull. 107, 1381–1397 (1995).

Clift, P. D. & Webb, A. A. G. A history of the Asian monsoon and its interactions with solid Earth tectonics in Cenozoic South Asia. SP 483, 631–652 (2019).

Clift, P. D. Controls on the erosion of Cenozoic Asia and the flux of clastic sediment to the ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 241, 571–580 (2006).

Clift, P. D. et al. Correlation of Himalayan exhumation rates and Asian monsoon intensity. Nat. Geosci. 1, 875–880 (2008).

Lee, J. et al. Monsoon-influenced variation of clay mineral compositions and detrital Nd-Sr isotopes in the western Andaman Sea (IODP Site U1447) since the late Miocene. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecolo. 538, 109339 (2020).

Badgley, C. et al. Ecological changes in Miocene mammalian record show impact of prolonged climatic forcing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105, 12145–12149 (2008).

Thomson, J. R. et al. Tectonic and climatic drivers of Asian monsoon evolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 4022 (2021).

Acosta, R. P. & Huber, M. Competing topographic mechanisms for the summer Indo-Asian Monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085112 (2020).

Yao, Z. et al. Weakening of the South Asian summer monsoon linked to interhemispheric ice-sheet growth since 12 Ma. Nat. Commun. 14, 829 (2023).

Holbourn, A. E. et al. Late Miocene climate cooling and intensification of Southeast Asian winter monsoon. Nat. Commun. 9, 1584 (2018).

Licht, A. et al. Asian monsoons in a late Eocene greenhouse world. Nature 513, 501–6 (2014).

Moucha, R. & Forte, A. M. Changes in African topography driven by mantle convection. Nat. Geosci. 4, 707–712 (2011).

Nigrini, C. Composition and biostratigraphy of radiolarian assemblages from an area of upwelling (northwestern Arabian Sea, lag 117). Proc. ODP Sci. Results 117, 89–126 (1991).

Webster, P. J. & Yang, S. Monsoon and enso: selectively interactive systems. Quart. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 118, 877–926 (1992).

Wei, H.-H. & Bordoni, S. On the role of the African topography in the South Asian monsoon. J. Atmos. Sci. 73, 3197–3212 (2016).

Chakraborty, A., Nanjundiah, R. S. & Srinivasan, J. Impact of African orography and the Indian summer monsoon on the low-level Somali jet. Int. J. Climatol. 29, 983–992 (2009).

Slingo, J., Spencer, H., Hoskins, B., Berrisford, P. & Black, E. The meteorology of the western Indian Ocean, and the influence of the East African highlands. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 363, 25–42 (2005).

Wen, Q. et al. Contrasting responses of Indian summer monsoon rainfall and Arabian Sea upwelling to orbital forcing. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 409 (2024).

Le Mézo, P., Beaufort, L., Bopp, L., Braconnot, P. & Kageyama, M. From monsoon to marine productivity in the Arabian Sea: insights from glacial and interglacial climates. Clim 13, 759–778 (2017).

Jalihal, C., Srinivasan, J. & Chakraborty, A. Response of the low-level jet to precession and its implications for proxies of the indian monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL094760 (2022).

Turner, A. G. & Annamalai, H. Climate change and the South Asian summer monsoon. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 587–595 (2012).

Findlater, J. A major low-level air current near the Indian Ocean during the northern summer. Quart. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 95, 362–380 (1969).

Clemens, S., Prell, W., Murray, D., Shimmield, G. & Weedon, G. Forcing mechanisms of the Indian Ocean monsoon. Nature 353, 720–725 (1991).

Li, T. et al. Distinctive South and East Asian monsoon circulation responses to global warming. Sci. Bull. 67, 762–770 (2022).

Gill, A. E. Some simple solutions for heat-induced tropical circulation. Quart. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 106, 447–462 (1980).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Mon. Wea. Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Abram, N. J. et al. Palaeoclimate perspectives on the Indian Ocean dipole. Quat. Sci. Rev. 237, 106302 (2020).

Mohtadi, M., Prange, M., Schefuß, E. & Jennerjahn, T. C. Late Holocene slowdown of the Indian Ocean Walker circulation. Nat. Commun. 8, 1015 (2017).

Cai, W. et al. Increased frequency of extreme Indian Ocean Dipole events due to greenhouse warming. Nature 510, 254–258 (2014).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Li, T. Atmosphere–warm Ocean interaction and its impacts on Asian–Australian Monsoon variation. J. Clim. 16, 1195–1211 (2003).

Stowasser, M., Annamalai, H. & Hafner, J. Response of the South Asian summer monsoon to global warming: mean and synoptic systems. J. Clim. 22, 1014–1036 (2009).

Van Der Burgh, J., Visscher, H., Dilcher, D. L. & Kürschner, W. M. Paleoatmospheric signatures in Neogene fossil leaves. Science 260, 1788–1790 (1993).

Kürschner, W. M., Kvaček, Z. & Dilcher, D. L. The impact of Miocene atmospheric carbon dioxide fluctuations on climate and the evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105, 449–453 (2008).

Royer, D. L., Berner, R. A. & Beerling, D. J. Phanerozoic atmospheric CO2 change: evaluating geochemical and paleobiological approaches. Earth Sci. Rev. 54, 349–392 (2001).

Stults, D. Z., Wagner-Cremer, F. & Axsmith, B. J. Atmospheric paleo-CO2 estimates based on Taxodium distichum (Cupressaceae) fossils from the Miocene and Pliocene of Eastern North America. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 309, 327–332 (2011).

Grein, M. et al. Atmospheric CO2 from the late Oligocene to early Miocene based on photosynthesis data and fossil leaf characteristics. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 374, 41–51 (2013).

Franks, P. J. et al. New constraints on atmospheric CO2 concentration for the Phanerozoic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 4685–4694 (2014).

Wang, Y., Momohara, A., Wang, L., Lebreton-Anberrée, J. & Zhou, Z. Evolutionary history of atmospheric CO2 during the late Cenozoic from Fossilized Metasequoia needles. PLoS ONE 10, e0130941 (2015).

Steinthorsdottir, M. et al. Fossil plant stomata indicate decreasing atmospheric CO2 prior to the Eocene–Oligocene boundary. Clim 12, 439–454 (2016).

Reichgelt, T., D’Andrea, W. J. & Fox, B. R. S. Abrupt plant physiological changes in southern New Zealand at the termination of the Mi-1 event reflect shifts in hydroclimate and pCO2. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 455, 115–124 (2016).

Sun, B.-N. et al. Reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 during the Oligocene based on leaf fossils from the Ningming Formation in Guangxi, China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 467, 5–15 (2017).

Retallack, G. J. Greenhouse crises of the past 300 million years. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 121, 1441–1455 (2009).

Seki, O. et al. Alkenone and boron-based Pliocene pCO2 records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 201–211 (2010).

Zhang, Y. G., Pagani, M., Liu, Z., Bohaty, S. M. & DeConto, R. A 40 million-year history of atmospheric CO2. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 371, 20130096 (2013).

Badger, M. P. S. et al. CO2 drawdown following the middle Miocene expansion of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Paleoceanography 28, 42–53 (2013).

Badger, M. P. S., Schmidt, D. N., Mackensen, A. & Pancost, R. D. High-resolution alkenone palaeobarometry indicates relatively stable pCO2 during the Pliocene (3.3–2.8 Ma). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 371, 20130094 (2013).

Bartoli, G., Hönisch, B. & Zeebe, R. E. Atmospheric CO2 decline during the Pliocene intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations. Paleoceanography 26, 2010PA002055 (2011).

Foster, G. L., Lear, C. H. & Rae, J. W. B. The evolution of pCO2, ice volume and climate during the middle Miocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 341-344, 243–254 (2012).

Greenop, R., Foster, G. L., Wilson, P. A. & Lear, C. H. Middle Miocene climate instability associated with high-amplitude CO2 variability. Paleoceanography 29, 845–853 (2014).

Martínez-Botí, M. A. et al. Plio-Pleistocene climate sensitivity evaluated using high-resolution CO2 records. Nature 518, 49–54 (2015).

Stap, L. B. et al. CO2 over the past 5 million years: Continuous simulation and new δ11B-based proxy data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 439, 1–10 (2016).

Chou, C., Neelin, J. D., Chen, C.-A. & Tu, J.-Y. Evaluating the “rich-get-richer” mechanism in tropical precipitation change under Global Warming. J. Clim. 22, 1982–2005 (2009).

Huang, P., Xie, S.-P., Hu, K., Huang, G. & Huang, R. Patterns of the seasonal response of tropical rainfall to global warming. Nat. Geosci. 6, 357–361 (2013).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Han, Z., Power, K., Li, G. & Zhang, Q. Impacts of mid-pliocene ice sheets and vegetation on Afro-Asian summer monsoon rainfall revealed by EC-earth simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106145 (2024).

Seager, R., Naik, N. & Vecchi, G. A. Response of the South Asian summer monsoon to global warming: mean and synoptic systems. J. Clim. 23, 4651–4668 (2010).

Ramstein, G., Fluteau, F., Besse, J. & Joussaume, S. Effect of orogeny, plate motion and land–sea distribution on Eurasian climate change over the past 30 million years. Nature 386, 788–795 (1997).

Tardif, D. et al. The role of paleogeography in Asian monsoon evolution: a review and new insights from climate modelling. Earth Sci. Rev. 243, 104464 (2023).

Haug, G. H. & Tiedemann, R. Effect of the formation of the Isthmus of Panama on Atlantic Ocean thermohaline circulation. Nature 393, 673–676 (1998).

Sun, J. et al. Permanent closure of the Tethyan Seaway in the northwestern Iranian Plateau driven by cyclic sea-level fluctuations in the late Middle Miocene. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 564, 110172 (2021).

Döscher, R. et al. The EC-Earth3 Earth system model for the coupled model intercomparison project 6. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 2973–3020 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Simulating the mid-Holocene, last interglacial and mid-Pliocene climate with EC-Earth3-LR. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 1147–1169 (2021).

Doblas. et al. Using EC-Earth for climate prediction research. ECMWF Newsletter 154, 35–40 (2018).

Meucci, A., Young, I. R., Hemer, M., Trenham, C. & Watterson, I. G. 140 years of global Ocean wind-wave climate derived from CMIP6 ACCESS-CM2 and EC-Earth3 GCMs: global trends, regional changes, and future projections. J. Clim. 36, 1605–1631 (2023).

Cao, N. et al. The role of internal feedbacks in sustaining multi-centennial variability of the Atlantic Meridional overturning circulation revealed by EC-Earth3-LR simulations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 621, 118372 (2023).

Madec, G. et al. NEMO Ocean Engine. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1472492 (2017).

Han, Z. & Li, G. The changes in south Asian summer monsoon circulation during the mid-Piacenzian warm period. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-024-07179-1 (2024).

Li, G., Xie, S.-P., He, C. & Chen, Z. Western Pacific emergent constraint lowers projected increase in Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 708–712 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Impact of interannual variation of the spring Somali Jet intensity on the northwest–southeast movement of the South Asian High in the following summer. Clim. Dyn. 60, 1583–1598 (2023).

Singh, S., Parkash, B., Awasthi, A. K. & Kumar, S. Late Miocene record of palaeovegetation from Siwalik palaeosols of the Ramnagar sub-basin, India. Curr. Sci. India 100, 213−222 (2011).

Wen, Q. et al. Grand dipole response of Asian summer monsoon to orbital forcing. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 202 (2024).

Rykaczewski, R. R. & Checkley, D. M. Jr Influence of ocean winds on the pelagic ecosystem in upwelling regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1965–1970 (2008).

Schneider, T., O’Gorman, P. A. & Levine, X. J. Water vapor and the dynamics of climate changes. Rev. Geophys. 48, 3 (2010).

Han, Z. & Li, G. Uncertainty of the simulated mid-pliocene changes of Sahel summer rainfall in the PlioMIP2 multimodel ensemble. J. Clim. 37, 875–894 (2024).

Han, Z. et al. Changes in global monsoon precipitation and the related dynamic and thermodynamic mechanisms in recent decades. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 1490–1503 (2019).

Chadwick, R. Which aspects of CO2 Forcing and SST warming cause most uncertainty in projections of tropical rainfall change over land and ocean?. J. Clim. 29, 2493–2509 (2016).

Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Atmosphere-ocean thermal coupling in the North Atlantic: a positive feedback. Quart. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 126, 3343–3369 (2000).

Fu, Z.-H., Zhou, W., Xie, S.-P., Zhang, R. & Wang, X. Dynamic pathway linking Pakistan flooding to East Asian heatwaves. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk9250 (2024).

Hu, P. et al. Revisiting the linkage between the Pacific–Japan pattern and Indian summer monsoon rainfall: the crucial role of the maritime continent. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106982 (2024).

NCL. NCAR Command Language (Version 6.6. 2). Boulder, Colorado: UCAR/NCAR/CISL/TDD. https://www.ncl.ucar.edu/ (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFF0807903), Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, Grant 2022-03129), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42305053, 42275047). The EC-Earth3 simulations and data analysis were performed using ECMWF’s computing and archive facilities and the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. 2022-06725.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. and Z.H. conceived and designed the study. Z.H. performed the data analyses and wrote the draft of the paper. W.N. and Z.W. carried out the EC-Earth experiments. Z.H., W.N., Z.W., X.L., Z.Y. and Q.Z. discussed, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z., Werner, N., Wang, Z. et al. Miocene African topography induces decoupling of Somali Jet and South Asian summer monsoon rainfall. Nat Commun 16, 7172 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62186-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62186-y