Abstract

Optical neural networks (ONNs) promise computing efficiency beyond microelectronics for modern artificial intelligence (AI). Current ONNs using analog matrix-vector multiplication (MVM) implementations are fundamentally limited in numerical precision due to accumulated noise in electro-optical processing. We propose a digital-analog hybrid MVM architecture that achieves a high numerical precision without sacrificing computing efficiency. Our fabricated proof-of-concept hybrid optical processor (HOP) achieves 16-bit precision in high-definition image processing, with a pixel error rate of 1.8 × 10−3 at a signal-to-noise ratio of 18.2 dB, and shows no accuracy loss in MNIST digit recognition. We further explore applying the HOP processor in You Look Only Once (YOLO) object detection and demonstrate sufficient numerical precision is crucial for high confidence detection in real-world neural networks. The hybrid optical computing concept may be applied to various photonic MVM implementations to enable accurate optical computing architectures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern artificial intelligence based on deep learning algorithms has demonstrated impressive capabilities1. However, these algorithms require enormous computing power and corresponding energy. The demand for computing power is now doubling every 3–4 months2, a rate surpassing the well-known Moore’s law. This has given rise to domain-specific hardware accelerators using application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), for example, Google’s tensor processing units (TPUs)3 and IBM’s TrueNorth4. The aim is to develop an efficient hardware platform with advanced parallelism for matrix multiplications. However, microelectronics is encountering fundamental bottlenecks in speed, energy consumption, heating, and interconnect delay, which become increasingly hard to resolve by scaling5,6,7.

Photonic integrated circuits (PICs) present a pathway free from these obstacles, and hence form a promising disruptive computing architecture beyond von Neumann architecture and Moore’s Law to potentially accelerate neural network applications efficiently8,9,10. Consequently, integrated photonic matrix-vector multiplications (MVMs) for optical neural networks (ONNs) have been proposed to address the obstacles of microelectronics11,12, showing potential to surpass their digital microelectronic counterparts in calculating speed, energy consumption, as well as computing density13. Despite the advantages of photonic MVMs, the demonstrations are all based on analog computing architectures where the input and weight vectors (i.e., the multipliers and multiplicands for the matrix multiplication) are represented by light intensities. The analog computing nature of current photonic MVMs presents a major scientific challenge: insufficient signal-to-noise ratio due to accumulated noise, and crosstalk in the computing system. This imposes several fundamental limitations. One primary limitation is the low numerical precision. The intensity resolution of the optical signals is usually limited to a numerical precision of around 4 bits14,15. Efforts have recently been made to increase the control precision of the weight values up to 9 bits for some analog ONN schemes16,17. However, this does not directly translate into a numerical precision of 9 bits for the matrix multiplication, but rather 4.2 bits based on a 99.7% confidence interval derived from the noise distribution of the obtained results17. In practice, 16-bit wide fixed-point numerical precision is required for reasonable training convergence18 and 8-bit numerical precision is generally required and recognized as the “industry standard” for inference tasks19,20,21. Second, analog optical computing is incompatible with microelectronics, requiring high-resolution digital-to-analog conversions (DACs) and analog-to-digital conversions (ADCs).

Here, we propose a new type of digital-analog hybrid MVM processor for optical neural networks. The hybrid optical processor (HOP) differs fundamentally from existing analog MVM processors and offers the following benefits. The introduction of logic levels can significantly increase the numerical precision. Powerful digital signal processing (DSP) algorithms can improve calculation performance and ensure high calculation repeatability. The high-resolution DACs for the inputs can be removed, and the resolution requirements for ADCs for the outputs can be greatly released by M bits, considering MVM of N-bit multipliers and M-bit multiplicands. In return, this can increase the operating speed and improve the compatibility with microelectronics. We propose the concept of HOP for the MVM operations in convolution neural networks. Our simulations show good noise tolerance and improved performance of the HOP over the analog optical computing scheme. At an signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 25 dB, our HOP can achieve an root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 1.2 × 10−3 for an 8-bit image processing task with a 3 × 3 convolutional operator. We have also built a proof-of-concept silicon photonic chip and applied the HOP in three tasks: a 16-bit depth high-definition image processing (HDIP) task, a toy-model based handwritten digit recognition (HWDR) task, and an object detection task based on the real-world YOLO neural network model. The convolution results show that a record high numerical precision of 16 bits is successfully achieved with a pixel error rate (PER) of 1.8 × 10−3 at a SNR of 18.2 dB and a bit rate of of 7.5 Gb/s for the inputs. The HWDR shows the same accuracy as the one calculated with a desktop computer. The YOLO object detection task shows a true demand for numerical precision in real-world neural network models. The first convolution layer is processed by our HOP, and vehicles can be detected with high confidence. A complementary simulation shows if all convolution layers are processed with our HOP, we can detect near, mid-range, and distant vehicles with high confidence, while analog computing scheme would result in a severe performance degradation even for near vehicles and completely fail in the detection for distant ones at the same SNRs. Notably, the HOP is a method that could potentially be applied to other photonic MVM schemes and spark new concepts considering ONNs and domain-specific optical computing.

Results

The principle of the hybrid optical processor

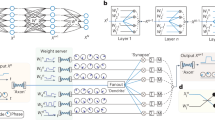

Analog signals are fundamentally vulnerable to noise and crosstalk. The optical computing system can be seen as an optical signal processing system and ONN is a representation of layers of the optical matrix multiplication system. Shown in Fig. 1a, analog signals traversing the signal processing system with noise and crosstalk suffer more severe degradation than digital signals under the same SNR. This is due to the absence of logic levels and decision-making processes in analog systems, which prevents the signal from being effectively recovered and equalized. The hypothesis here is that the performance of the optical computing system can benefit from the utilization of digital optical signals.

a Digital signal is more robust to noise and crosstalk in a signal processing system. ONN can be seen as a signal processing system where digital signals can potentially be applied for better calculation repeatability, precision, scalability, and compatibility with microelectronics compared to analog signals. b The abstracted analog photonic MVM core utilizing analog signals for both input d and weight w. c The proposed digital-analog hybrid photonic MVM core utilizing digital signals for input d, with relaxed constraints for signal format converters.

Analog optical matrix multiplication architectures rely on analog photonic multiplication cores, abstractly represented in Fig. 1b. The input d and weight w originate from M-bit and N-bit DACs. After electro-optical conversion, d and w are multiplied and converted back into the electrical domain. This generates an optical signal with \(({2}^{M}-1)\times ({2}^{N}-1)\) possible levels (considering signal levels starting from 0, thus 2M × 2N − 2M − 2N + 1). To accomplish a full-precision multiplication without losing information, an ADC with a resolution (effective number of bits (ENOB))) of \({\log }_{2}[({2}^{M}-1)\times ({2}^{N}-1)]\) bits is necessary. This can be very challenging, especially for high-speed operations, since speed-versus-resolution is a well-known trade-off for the signal converters22. While reducing the operational speed to attain the desired resolution is possible, the high-speed operation advantage of photonic components vanishes. On the contrary, while high-speed operations are maintained, the trade-off inevitably reduces in numerical precision (Details are discussed in Supplementary Table 1, 2, and Supplementary Fig. 2). The number of overall possible signal levels increases proportionally for calculating an inner product of an input vector and a weight vector, generating \(L\times ({2}^{M}-1)\times ({2}^{N}-1)\) possible levels, which requires an ADC with a resolution of \({\log }_{2}[L\times ({2}^{M}-1)\times ({2}^{N}-1)]\) bits.

The HOP concept employs digital binary words for matrix multiplication into the optical computing system. For single MVM operation, d is carried in digital optical signals using binary words, while w is kept in analog format, leaving the computing system’s design unchanged. If w originates from an N-bit DAC, the multiplication result is a signal with a reduced number of 2N − 1 levels, which requires an ADC resolution of \({\log }_{2}({2}^{N}-1)\) bits. The HOP concept can be extended to build a hybrid digital-analog photonic MVM core represented in Fig. 1c. An input vector \({({d}_{11},{d}_{21},...,{d}_{L1})}^{T}\) and a weight vector (w11, w12, . . . , w1L) can be input to L multipliers. The results from the multipliers are kept in the optical domain and summed in a photo-detector. These are then processed by a post-processing electrical circuit to get the result of the vector inner product (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Columns of the input matrix D are loaded sequentially to accomplish the MVM operation. The vector multiplication yields \(L\times ({2}^{N}-1)\) signal levels, requiring an ADC with a resolution of \({\log }_{2}[L\times ({2}^{N}-1)]\) bits. Note that the resolution of the ADC is independent of the bit width of the input vector d. In theory, the hybrid photonic MVM core can support input values of any precision without compromising the complexity of the photonic part of the hardware. However, higher precision input values increases the complexity of the post-processing circuit (Supplementary Fig. 1).

By eliminating the need for high-speed DACs in processing the input matrix D, the hybrid MVM core reduces costs, saves energy, and simplifies system complexity. The requirement for the resolution of ADC of the hybrid multiplier is ~M-bit less than the analog multiplier, potentially increasing the operating speed (see Supplementary Table 1, 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The relaxed constraints on ADC/DAC converters can improve the processor’s compatibility with microelectronics. From an information encoding point of view, the analog ONN processors employ only the signal amplitude for encoding information. In contrast the HOP utilizes both amplitude and time for information encoding. The increased encoding space in HOP results in a larger Euclidean distance between encoded signal samples when compared to analog ONN processors. As a result, the HOP performs better against noise and exhibits a higher numerical precision.

The computational efficiency (operations per Watt) for both analog and HOP schemes can be expressed by \(2k/(E\times M)\), where k is the kernel dimension and E is the energy consumption per sample. M is the bit-width of the input and M = 1 for the analog optical computing scheme (detailed derivations are provided in Supplementary Information Section 8). The computational efficiency scales linearly with kernel size. And to achieve a computational efficiency supremacy over microelectronics, a large matrix size is a must to be implemented. We can derive the computational efficiency by analysing the power consumptions for both schemes. The optical implementation for both schemes is the same (i.e., laser sources, modulators, weighting elements, and photodetectors). For a broadcast-and-weight implementation using Mach-Zehnder modulator (MZM) (data broadcasting) and andmicroring resonators (MRRs) (weight), we estimate a total energy consumption of 2.7 pJ/sample (1.27 pJ/sample for the laser, 0.7 pJ/sample for the MZM, 1.0 pJ/sample for the photodetector)23,24. And the MRRs are considered to be trimmed to their target weights during calibration and operate passively, thus do not consume power.

The key difference in power consumptions for the analog and HOP schemes lies in the electrical interfaces. Note that for a fair comparison considering real-world implementations, we assume the use of the same available ADCs for both schemes, and do not target “full numerical precision” operations shown in the previous analysis on ADC resolution requirements, but rather a “best effort” way for numerical precision. Therefore, we assume 8-bit matrix multiplications with the use of 8-bit DACs and ADCs. The analog scheme requires high-speed DACs. With a state-of-the-art current-steering DAC implementation at 1 GS/s operating speed, the power consumption can be 31 pJ/sample for 8-bit resolution25. Note that the power consumption of DACs scales with 2N. The state-of-the-art ADCs working at 1 GS/s consume 1.18 pJ/sample26. As a result, the overall power consumption per sample is ~34.88 pJ/sample for the analog scheme and 3.88 pJ/sample for the HOP scheme. Substituting these values into the computational efficiency yields a TOPS/W = 0.057k for the analog scheme and a TOPS/W = 0.064k for HOP scheme. The HOP scheme closely matches the analog scheme in computational efficiency. To justify the results, the HOP scheme requires multiple optical operations and AD conversions per word due to the use of time encoding, therefore, the power consumption could be higher. On the other hand, the HOP scheme does not require any involvement of high-speed high-resolution DACs for the inputs, therefore the reducing the overall power consumption. In conclusion, the HOP scheme trades the power consumption of the DACs with the power consumption of additional optical operations and AD conversions. For a large matrix size k > 47, the HOP scheme could achieve a computational efficiency well beyond 3 TOPS/W (Nvidia H100, microelectronics). But the benefit of the HOP scheme is a higher numerical precision due to a better noise tolerance.

An implementation of the digital-analog hybrid photonic MVM core

Here we implement the HOP using cascaded microring modulators (MRMs) instead of MZM and MRRs due to the available photonic integrated circuits. Each MRM corresponds to one hybrid photonic multiplication core, as shown in Fig. 2a. The MRM modulates a laser source of a particular wavelength. The input of the multiplier d is loaded as binary words through the high-speed ports, while the weight d from an N-bit ADC is loaded using a microheater-based modulation bias. The result is a weighted optical signal y, which is photodetected and sent to an ADC for decoding the information. The examples shown in Fig. 2 with integer inputs and weights are for illustrative purposes. The multiplier can also handle normalized decimals, where the binary words represent only the decimals. Positive and negative weights are realized by biasing the MRM at the rising and falling slope of the transmission curve (Supplementary Fig. 3). The relationship between the weight and the heater bias is measured and shown in Fig. 2b. The measurement is used as a lookup table for the loading of the normalized weights. This microheater-based weight loading supports refreshing at tens of kilohertz with the thermal-optic effect. However, the refresh rate of the weight vector can be much quicker if the HOP was implemented using independent input and weight loading devices, for example, based on a Mach-Zehnder modulator and an MRM array17. The HOP can therefore enable the possibility for in-situ training.

a The implementation of a single hybrid digital-analog photonic multiplication core using an MRM, where the input d in the form of a digital optical signal is loaded through the high-speed port while the weight w is loaded using microheater-based modulation bias. b The measured relationship between the normalized weight and the required heater voltage for the modulation bias can be used as a lookup table to load the weight. c The implementation and optical signal temporal evolution of the digital-analog hybrid photonic MVM core, including a multi-wavelength light source, an array of microring modulators, and a photodiode. d Post-processing of the multilevel signal includes an ADC and a shift-add operation. Here, the multilevel signal is converted to a binary signal, and the final result can be recovered via shifts and adds.

The implementation of the hybrid photonic MVM core is shown in Fig. 2c. The example illustrated here is a single 3 × 3 convolution operator. Multiple convolution operators can be simultaneously integrated into a PIC to scale up for multiple convolution operations or complete matrix multiplication. A multi-wavelength light source is used with L wavelengths for the convolution with an operator of L elements. The MRM array accomplishes the element-wise multiplication of the input vector \({({d}_{11},{d}_{21},...,{d}_{L1})}^{T}\) and a weight vector (convolution operator) (w11, w12, . . . , w1L). i denotes indices of the current column of the input matrix D. The example shows the input with 8-bit precision. The modulation generates a wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) signal with weighted on-off keying (OOK) signaling for each wavelength (denoted as λ). The results from the hybrid photonic multipliers are summed up by a photodiode, accomplishing the convolution (MVM). The photodetection results in a multilevel signal at the baseband (i.e., a pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) signal). Shown in Fig. 2d, the multilevel signal is then further processed digitally word by word by a multilevel-to-binary converter, including PAM decoding (i.e., ADC), and a shift-add operation. The multilevel-to-binary conversion process converts the final result yn into the form of binary words (Details are discussed in Supplementary Fig. 1).

Noise tolerance and computational robustness

We explore the noise tolerance of the proposed HOP using numerical simulations with a comparison to the analog computing scheme. Figure 3a illustrates the simulation setup. An image “Chelsea” from the scikit-image dataset27 is processed using the 3 × 3 Prewitt convolution operator for horizontal edge detection. We apply additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) to the computing systems, i.e., the weights, with a given SNR. The image has a size of 300 × 451 pixels. The pixel values are normalized by feature scaling and reshaped into 3 × 3 data sequences, with the current vector denoted as d1 − d9. The vector is multiplied by the Prewitt operator, and the 9 results are summed up to form the pixel result of the processed image. For the analog scheme, the vector is encoded only in the amplitude of the signals. For the HOP scheme, the vector is encoded using binary words with 8-bit precision, representing a gray image with 8-bit color depth or 256 levels. The signal processing for the HOP scheme is done following procedures in Fig. 2c, d. Finally, the resulting pixels are reassembled to present the processed image, which has a size of 298 × 449, due to the lack of padding for the boundary of the original image. Note that we used an image with an 8-bit gray scale in the simulation to allow direct result comparison with existing literature. In the experiment where we do an edge detection task (see Section Edge Detection), an image with 16-bit color depth is used.

a Simulation setup. An image “Chelsea” from the scikit-image dataset27 is convolved with a Prewitt operator (vertical edge detection). We explore the noise tolerance of both the analog and the hybrid optical computing systems by adding additive white Gaussian noise to the weights and examining the system’s performance by investigating the noise distribution of the outputs. b performance of the analog and hybrid computing schemes in terms of RMSE with different SNRs. The following results are obtained at an SNR of 25 dB. c, f Processed and reconstructed images by the analog and hybrid computing systems, respectively. d, g Distribution of expected pixel values against the processed pixel values (both normalized), for the analog and hybrid computing systems, respectively. Insets show the corresponding processed images. Noisy pixels can be clearly observed in the image processed using analog computing. e, h Noise distribution of the analog and hybrid computing systems, respectively. Analog computing reveals a Gaussian noise distribution with a standard deviation of 0.027, corresponding to a numerical precision of 3.6 bits. The HOP shows a greatly improved noise distribution thanks to the introduction of logic levels and decisions based on thresholding.

Figure 3b gives the simulation results of the RMSE against different SNRs for both computing schemes. At an SNR of 25 dB, the RMSE can be reduced from 2.4 × 10−2 using the analog computing scheme to 1.2 × 10−3 using the HOP scheme. In short, the HOP scheme outperforms its analog counterpart in noise resilience, particularly within lower SNR regimes, suggesting superior scalability potential for optical computing applications. This resilience against noise is important, considering that noise presents a significant barrier to the scalability and practical deployment of ONNs.

To visually inspect the difference of the simulation results, Fig. 3c, f give the processed and reconstructed image at an SNR of 25 dB, by the analog and the HOP computing schemes, respectively. Flake noise clearly presents on the processed image by the analog computing scheme, indicating a worse noise tolerance. The quality difference of the processed images can be quantified by looking into the distributions of expected pixel values against the processed pixel values, and the noise distributions.

Figure 3d,g give the distributions of the expected pixel values y against the processed ones \(\hat{y}\) at a SNR of 25 dB, for the analog and the HOP schemes, respectively. Figure 3e,h show the noise distribution (i.e., \(\hat{y}-y\)) of the output signals from the analog and the HOP schemes respectively. Results from the analog computing scheme reveal a Gaussian noise distribution with a standard deviation of 0.027. The corresponding numerical precision is 3.6 bits, calculated from the 3σ value (99.7% confidence interval) of the Gaussian-shaped noise distribution12. The noise distribution from the results of the HOP scheme is, however, fundamentally different from the analog computing scheme due to the introduction of logic levels and decisions. The noise in the results of the HOP scheme does not comply with a Gaussian distribution. Therefore, we borrowed the performance metrics from digital communication, i.e., error rate at a certain achievable SNR to characterize the HOP system. The PER is 2.5 × 10−4 at an SNR of 25 dB, realizing a numerical precision of 8 bits. We have focused on a 3 × 3 convolution operator here in the simulation because our target applications are convolutional neural networks (CNNs) models. The simple Prewitt operator, using weight values with a bit width of less than 2 bits, is applied to demonstrate the performance difference between digital and analog inputs. Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2 show a more generalized comparison where the bit width of the weights is assumed to be 8 bits. And in the YOLO object detection section, we have conducted an experiment with convolution operators where the weight values are 8 bits.

Experimental setup

We demonstrate the HOP in a proof-of-concept experiment for three main tasks: HDIP, HWDR, and YOLO object detection. The HDIP task evaluates the numerical precision of the HOP. The HWDR task utilizes the HOP in an inference task widely found in literature, although it is considered a toy neural network model. The object detection task with the YOLO neural network model is designed to explore the HOP’s potential in real-world applications.

Figure 4a shows the experimental setup. The multi-wavelength light source comes from a flattened optical frequency comb (OFC) containing 9 wavelengths spaced at 80 GHz with an overall optical power of 7.0 dBm and a center wavelength located around 1543.5 nm. The comb source is coupled into the PIC chip of cascaded MRMs28,29. The insets of 4a show the pictures of the packaged PIC chip and the microscopic image of the cascaded MRMs. Each MRM modulates the corresponding comb line with the inputs and weights. The inputs of the HOP come from the image pixel values. The pixel values are normalized and reshaped into 3 × 3 data sequences, with the current vector denoted as d1 − d9. The inputs are loaded to the high-speed modulation ports of an MRM array in the form of binary words and the weights from the convolution operator are applied to the corresponding MRMs using microheater-based modulation biases. The WDM signal generated from the MRM photonic chip is coupled into an avalanche photodiode (APD) with a launch power of −12.0 dBm. The photodetected baseband multilevel signal is sampled by a digital storage oscilloscope (DSO) and is further processed by a simple DSP chain30, including low-pass filtering, resampling, and most importantly, digital equalization. Performance of the HOP is evaluated after the postprocessing procedure, including decision, multilevel-to-binary conversion (Fig. 2d), as well as image reconstruction.

a Measurement setup, including DSP and signal postprocessing. The HOP consists of a packaged PIC chip containing 20 cascaded MRMs, and an external photodiode (PD). Insets give the picture of the packaged chip and the microscopic image of the cascaded MRMs. b Detailed operation condition and signal flow for the edge detection task. c Detailed operation condition and signal flow for the HWDR and the YOLO object detection task.

Depicted in Fig. 4b, the HDIP task is performed with each of the MRMs working at 7.5 Gb/s. The 3 × 3 convolution operator is disassembled into 3 sets and implemented through 3 measurements, due to our limited number of high-speed electrical signal channels. The results from the 3 measurements are added up together after DSP (before decision), and post-processing is done afterward for performance evaluation. Figure 4c shows the operation condition and signal flow for the HWDR and YOLO tasks. We use an field programmable gate arrays (FPGA) for simultaneously loading 9 microring modulators at a speed of 400 and 300 Mb/s to compute the entire convolution at once for the two tasks, respectively.

High-definition image processing

Figure 5a shows the original image and the processed red (R), Green (G), and Blue (B) channels. The image is taken with a mobile camera using an uncompressed raw format. Then it is converted to an image with a depth of 16 bits. The HOP processes the convolution using inputs with 16-bit binary words and applies the Prewitt vertical, Sobel vertical, and Laplacian operators. The processed color channels remain at 16-bit depth and show a high-quality appearance, indicating a high degree of noise resilience. This can be further proved by looking at the sequences of the pixel values with a comparison to the results calculated by a desktop computer, shown in Fig. 5b. Figure 5c shows the distribution of the expected pixel values y against the processed ones \(\hat{y}\). Figure 5d derives the noise distribution (i.e., \(\hat{y}-y\)) of the results by the HOP. The corresponding measured SNR is 18.2 dB, and the PER is 1.8 × 10−3. These results demonstrate that the HOP can handle the convolution task with very high precision, and the digital-analog hybrid optical computing architecture works with a high tolerance to noise. More image results processed by different convolutional operators through HOP are demonstrated in Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, and 6, including an optical noise tolerance test for an 8-bit image processing task.

a The original 16-bit image and the processed image channels using the Prewitt vertical, Sobel vertical, and Laplacian operators. b A section of the processed sequences of pixel values. Up: processed by the HOP; Down: processed by a desktop computer. c Distribution of expected pixel values against the processed pixel values (both normalized). d Noise distribution and calculation accuracy.

Handwritten digit recognition

Figure 6a presents the layer structure of the CNN used for the HWDR task, utilizing the MNIST database31. 10,000 images are processed and classified based on one convolution layer, rectified linear unit, pooling, flattening, and two fully connected layers of 100 and 10 neurons. We replaced the calculation of the convolution layer using our HOP, performing a full edge detection using four Prewitt operators. Figure 6b illustrates the confusion matrices for the prediction results, calculated by a desktop computer and the HOP. We observed the same overall accuracy for the predictions with the HOP compared to a desktop computer. We have also calculated the RMSEs of the 10,000 processed images compared with the true results calculated by a desktop computer. The results give a mean RMSE of 5.4 × 10−3 and a standard deviation of 7.5 × 10−3. And the overall PER for the 10,000 images is 2.7 × 10−3. The results show the HOP handling the toy model well, again indicating a high level of numerical precision.

a, Layer structure of the CNN to perform the HWDR task using the modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (MNIST) database. The convolution layer of the CNN is implemented using the HOP, and the rest of the network is performed offline by a desktop computer. b, Confusion matrices for the prediction results, calculated by a desktop computer and the HOP, respectively.

YOLO object detection

To explore the feasibility of the HOP and to demonstrate the demand for sufficient numerical precision, in real-world neural network models, we have applied the HOP for a YOLO object detection task. Specifically, we utilize YOLO v3, a pre-trained 106-layer convolutional neural network model, where each layer consists of linear convolution operations followed by nonlinear activation functions. In this study, we implement only the linear convolution operations, while the nonlinear activations are processed computationally.

We first validate the approach through simulations, following the methodology outlined in Fig. 2. In the simulation, AWGN is added to the weights of each convolution layer, with 10 tests carried out under each SNR value. The input image shown in Fig. 7a is captured by a mobile camera with a size of 416 × 416. The visible vehicles in the image are labeled as Car 1 through Car 6 and categorized into three groups: a nearby object (Car 1), mid-range objects (Car 2 to Car 4), and distant objects (Car 5 and Car 6). When processed by the YOLO model, the output provides object locations along with their confidence scores.

a Input image with labels arranged from near to distant. b, c Simulation results with an SNR of 15 dB using the analog scheme and the HOP scheme, respectively. d, e Comparison of the Analog and HOP schemes under various tested SNR values for the nearby vehicle (Car 1) and the distant vehicle (Car 4), respectively. f Detection results using the HOP scheme, where the first convolution layer is processed experimentally while subsequent layers are computed offline on a computer. g Reconstructed output images from the first convolution layer in the experiment. h Confidence score comparison for Cars 1 to 6 between experimental and simulated results, where the first convolution layer is replaced with the analog scheme or the HOP scheme. i Simulated detection results exploring various SNRs for a distant vehicle (Car 5). Box-and-whisker plots show median (center line), quartiles (box edges), and whiskers extending to the full data range (max/min values) for all 10 results per group.

Simulation results for SNR of 15 dB are presented in Fig. 7b, c, illustrating the performance of the analog and HOP schemes, respectively. In the analog scheme, vehicle positions are not accurately detected for nearby or distant objects. In contrast, the HOP scheme successfully identifies all six vehicles with high confidence. To further investigate the impact of SNR on the detection accuracy, we first analyze the recognition performance for the nearby object, i.e., Car 1, under various SNRs, as illustrated in Fig. 7d. Accuracy improves with increasing SNR in both schemes. In the full range of investigated SNRs, the HOP scheme consistently achieves higher confidence scores than the analog scheme, with a more pronounced performance gap at lower SNR values. And the analog scheme has greater performance fluctuations. We further evaluate the detection performance of a distant vehicle, i.e., Car 4. As shown in Fig. 7e, the results align with our previous observations on the detection of the nearby vehicle, where the HOP scheme outperforms the analog scheme and achieves a detection confidence score greater than 70% for SNR larger than 15 dB. We also notice that the analog scheme fails to detect Car 4 with an SNR equal to or less than 20 dB; the performance fluctuates widely for an SNR range from 25 to 30 dB.

These results show a true demand for numerical precision, even when the MVM is used for neural network applications. In the sense of the real-world YOLO model for autonomous driving, the capability of detecting distant vehicles through higher numerical precision means that the HOP scheme could potentially translate into a quicker response time and longer distances for braking or other measures in cases of emergency events, compared with analog schemes. Note that, for a convolutional neural network (where the YOLO model is based on), the weight matrices (convolutional kernels) to be multiplied are only 3 × 3 in size. For larger matrix sizes, the performance of the analog scheme could get much worse due to noise accumulation, further hindering its practical application (see Supplementary Table 1).

To experimentally validate the performance of the HOP scheme, we have carried out an experiment with a setup similar to that used in the HWDR task. Due to hardware constraints, only the first layer’s 32 convolution operations of the YOLO model are processed using our PIC chip, while the remaining convolution layers are computed offline on a computer. In the experiment, we get 14 dB SNR and an average PER of 2.8 × 10−2 for the 32 synthesized output feature images from the first layer. The detection results are shown in Fig. 7f. As observed, the output accurately identifies all the vehicles. Figure 7g presents the reconstructed feature maps from the first convolution layer, where distinct filter responses and clear object contours are evident.

Based on this experimental setup, we further conducted a supplementary simulation by replacing the first convolution layer with either the HOP or analog scheme. The confidence scores obtained in the experiment, are shown in Fig. 7h. The experiment results agree well with the simulation for the HOP scheme. For nearby and mid-range objects, the confidence scores exhibit no significant difference between the HOP and analog schemes. However, for distant objects, such as Car 5 and Car 6, the HOP scheme consistently achieves higher confidence scores. Specifically, for Car 5, the HOP scheme achieves confidence scores of 49% (simulation) and 46% (experiment), while the analog scheme yields only 28%. To further investigate the impact of SNR on the recognition of a distant object, i.e., Car 5, we analyzed the confidence score variations under different SNRs, as illustrated in Fig. 7i. Again, the HOP scheme demonstrates a clear advantage over the analog scheme, with significantly higher confidence scores for an SNR range of 10 to 20 dB. In conclusion, even if only the first layer is replaced by hardware with a realistic SNR, numerical precision is still essential, and the HOP scheme results in much improved final confidence scores for distant objects.

Discussion

There is often a perception that the numerical precision of the MVM operations for neural network applications is not so important, as the noise is beneficial to train the model and improves generalization and facilitates regularization. But there’s a difference between noise added to the training of the neural network and the hardware noise for inference tasks, where it is not controllable and accumulates. For inference tasks, the neural network is pre-trained, and sufficient numerical precision is required for an acceptable overall accuracy18, as we demonstrated in the YOLO object detection task.

Our HOP scheme provides a way to ease the requirement for SNR and to achieve a higher numerical precision. This scheme is also known as “bit slicing” in microelectronics32,33. However, since the clock speed in microelectronics is usually below several gigahertz, the “bit slicing” would reduce the operating speed by a factor of N, i.e., the numerical precision. However, photonics can utilize a much higher clock rate, thus a higher operating speed at the same numerical precision (Supplementray Table 2).

Optical computing has evolved from digital optical logic gates for general-purpose computing34 to domain-specific analog computing (for the physical implementation of neural networks11,35). Our domain-specific digital-analog hybrid optical computing architecture conceptually differs from logic-gate-based optical computing. Instead of pursuing general-purpose digital optical computing, we focus on domain-specified computing exclusively for matrix multiplications in neural networks. Implementing matrix multiplication is based on binary modulations and linear signal processing, avoiding the nonlinear processes that are usually less efficient. Lastly, instead of pursuing an all-optical solution, the HOP merges the best of photonics for matrix multiplication and electronics for logic-level restoration. The HOP is distinctive from analog optical computing schemes for neural networks.

Our results demonstrate the feasibility of overcoming the inherent challenges of analog optical computing through the digitization of optical signals. Given the benefits of better noise tolerance, the HOP has the potential to solve the obstacles of numerical precision, compatibility with microelectronics, and scaling of the ONNs (see Supplementary Table 3). Our findings here using digital optical inputs could potentially be applied to a wide range of photonic MVM architectures, including the Mach-Zehnder interferometer (MZI)–based coherent scheme11 and diffraction-based schemes36,37.

Methods

The multi-wavelength light source

The multi-wavelength light source used in the experiment is an electro-optical frequency comb38,39 implemented using a continuous-wave laser and optical phase modulation. An external cavity laser centered around 1543.5 nm with an output power of 10.5 dBm is launched into a phase modulator. The phase modulator is driven by a 40 GHz signal coming from a radio frequency (RF) synthesizer followed by a power amplifier. A 40-GHz spaced optical frequency comb is generated and fed into a wavelength-selective switch (WSS) after amplification. It is line-by-line filtered and equalized by the WSS, generating a flattened optical frequency comb with 9 comb lines and an amplitude variation of 1 dB. The amplitude variation is not calibrated nor compensated for the computing system due to the noise tolerance of the HOP. In principle, compensating for residual system impairments, like the amplitude variation within the optical frequency comb, could further enhance the HOP’s performance.

The microring modulator array chip

The PIC chip contains 20 cascaded MRMs, with a spacing of 250 μm between adjacent MRMs. Each MRM has a ring radius of 7.5 μm, thus a free spectral range around 13.1 nm. A microheater is sitting on top of each MRM for the alignment of the wavelength channels and the control of the modulation biases. The MRMs are based on a reverse-biased P-N junction in the middle of the microring waveguide29,40. The PIC chip is fabricated on a standard silicon-on-insulator wafer with a top silicon thickness of 220 nm. It is packaged with two edge coupling fibers, a high-speed printed circuit board (PCB) supporting 20 high-speed transmission lines, and a second PCB for the control of the microheaters. The electro-optical modulation bandwidth of the packaged modulators is measured to be around 15 GHz.

The signal source and digital signal processing

In the HDIP task, an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) (Keysight M8195A) is used. Limited by the available channels, 3 measurements are consecutively carried out. Each measurement uses 3 channels from the AWG at a speed of 7.5 Gb/s and a sampling rate of 15 GSa/s. The speed and the sampling rate are limited due to the use of external memory to load the entire image data, thus a mandatory clock division of four. In the HWDR and the YOLO tasks, an FPGA board (Xilinx ZCU104) is used to generate the 9 inputs to the HOP. The data rate for each data channel is set to 400 Mb/s for the HWDR task, and 300 Mb/s for the YOLO task, due to the limitation of the direct memory access module.

The weighted WDM signal is detected by an APD with a 3-dB bandwidth of 10 GHz. The photodetected baseband multilevel signal is sampled by a DSO (Agilent DSA-X 93304Q) with a sampling rate of 80 GSa/s and an analog bandwidth of 33 GHz. The samples are processed offline using DSP algorithms. We use a T/2-spaced linear feedforward equalizer with a filter length of 51 to compensate for the linear impairments from the devices used in the experiment, including the RF components, the high-speed PCB board, the PIC chip, as well as the APD. The coefficients of the equalizer are obtained through training based on the least-mean-square algorithm.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The measurement data generated in this study and processing scripts have also been deposited in (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10026198).

Code availability

The algorithms used for data loading, reconstructions, and digital signal processing are standard and are outlined in detail in the Methods. Python scripts can be provided by the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Wu, T. et al. A brief overview of ChatGPT: the history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 10, 1122–1136 (2023).

Amodei, D. & Hernandez, D. Review of AI and compute. https://openai.com/blog/ai-and-compute/ (2018).

Jouppi, N. P. et al. In-datacenter performance analysis of a tensor processing unit. In Proceedings of the 44th annual international symposium on computer architecture, 1–12 (2017).

Merolla, P. A. et al. A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 345, 668–673 (2014).

Theis, T. N. & Wong, H.-S. P. The end of moore’s law: A new beginning for information technology. Comput. Sci. Eng. 19, 41–50 (2017).

Rupp, K. et al. 42 years of microprocessor trend data. [Online]. https://www.karlrupp.net/2018/02/42-years-of-microprocessor-trend-data/ (2018).

Khan, H. N., Hounshell, D. A. & Fuchs, E. R. Science and research policy at the end of Moore’s law. Nat. Electron. 1, 14–21 (2018).

Caulfield, H. J. & Dolev, S. Why future supercomputing requires optics. Nat. Photonics 4, 261–263 (2010).

Miller, D. A. B. Perfect optics with imperfect components. Optica 2, 747–750 (2015).

Peng, H.-T., Nahmias, M. A., de Lima, T. F., Tait, A. N. & Shastri, B. J. Neuromorphic photonic integrated circuits. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 24, 1–15 (2018).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 11, 441–446 (2017).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Nahmias, M. A. et al. Photonic multiply-accumulate operations for neural networks. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 26, 1–18 (2019).

Tait, A. N., De Lima, T. F., Nahmias, M. A., Shastri, B. J. & Prucnal, P. R. Multi-channel control for microring weight banks. Opt. Express 24, 8895–8906 (2016).

Tait, A. N. et al. Neuromorphic photonic networks using silicon photonic weight banks. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Silicon microring synapses enable photonic deep learning beyond 9-bit precision. Optica 9, 579–584 (2022).

Bai, B. et al. Microcomb-based integrated photonic processing unit. Nat. Commun. 14, 66 (2023).

Gupta, S., Agrawal, A., Gopalakrishnan, K. & Narayanan, P. Deep Learning With Limited Numerical Precision. In International Conference On Machine Learning, 1737–1746 (PMLR, 2015).

Dettmers, T., Lewis, M., Belkada, Y. & Zettlemoyer, L. LLM.int8(): 8-bit matrix multiplication for transformers at scale https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.07339 (2022).

Jacob, B. et al. Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.05877 (2017).

Sung, W., Shin, S. & Hwang, K. Resiliency of deep neural networks under quantization https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06488 (2016).

Murmann, B. ADC Performance Survey 1997–2023. https://github.com/bmurmann/ADC-survey. (2023).

Wu, D. et al. Experimental demonstration of a 160 Gbit/s 3D-integrated silicon photonics receiver with 1.2-pj/bit power consumption. Opt. Express 31, 4129–4139 (2023).

Li, K. et al. An integrated CMOS–silicon photonics transmitter with a 112 Gigabaud transmission and picojoule per bit energy efficiency. Nat. Electron. 6, 910–921 (2023).

Kazmi, S. M. A. A. Low Power CMOS 8-Bit Current Steering DAC, Master’s thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1662231 (2021).

Yonar, A. S. et al. An 8b 1.0-to-1.25 GS/s time-based ADC with bipolar VTC and sense amplifier latch interpolated gated ring oscillator TDC. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 6, 193–196 (2023).

Van der Walt, S. et al. scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Kong, D. et al. Intra-datacenter interconnects with a serialized silicon optical frequency comb modulator. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 4677–4682 (2020).

Dong, P., Lee, J., Kim, K., Chen, Y.-K. & Gui, C. Ten-channel discrete multi-tone modulation using silicon microring modulator array. In 2016 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC), 1–3 (2016).

Kong, D. et al. 100 Gbit/s PAM-16 Transmission in the 2-μm Band over a 1.15-km Hollow-Core Fiber. In Optical Fiber Communications Conference (OFC), (IEEE, 2021).

LeCun, Y., Cortes, C. & Burges, C. J. The MNIST database of handwritten digits. http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/ (1998).

Sebastian, A., Le Gallo, M., Khaddam-Aljameh, R. & Eleftheriou, E. Memory devices and applications for in-memory computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 529–544 (2020).

Feinberg, B., Wang, S. & Ipek, E. Making memristive neural network accelerators reliable. In 2018 IEEE International Symposium on High Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), 52–65 (2018).

Bogoni, A., Wu, X., Bakhtiari, Z., Nuccio, S. & Willner, A. E. 640 Gbits/s photonic logic gates. Opt. Lett. 35, 3955–3957 (2010).

Xingyuan, X. et al. 11 TOPS photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks. Nature 589, 44–51 (2021).

Luo, X. et al. Metasurface-enabled on-chip multiplexed diffractive neural networks in the visible. Light.: Sci. Appl. 11, 158 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. Design of task-specific optical systems using broadband diffractive neural networks. Light.: Sci. Appl. 8, 112 (2019).

Parriaux, A., Hammani, K. & Millot, G. Electro-optic frequency combs. Adv. Opt. Photon. 12, 223–287 (2020).

Kong, D. et al. Cavity-less sub-picosecond pulse generation for the demultiplexing of a 640 Gbaud OTDM signal. In IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC) 2015, WG1.2 (IEEE, 2015).

Dong, P. et al. Wavelength-tunable silicon microring modulator. Opt. Express 18, 10941–10946 (2010).

Acknowledgements

D.K. acknowledges the research grant (VIL53077) of the Young Investigator Program (DONN) from the VILLUM FONDEN, and the EIC Pathfinder project DOLORES (101130178) from the European Innovation Council (EIC). H.H. acknowledges the research grant (VIL34320) of the Synergy Program (Searchlight) from the VILLUM FONDEN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.M. and D.K. conceived the concept and the experiment; X.M. and Q.L. performed the simulations, supervised by D.K., I.C. and C.L.; X.M. and D.K. designed the experiment; X.M. and D.K. constructed the experiment setup, performed the experiment, and processed the data; P.D. designed the PIC; K.K. packaged the PIC; D.K. and X.M. characterized the PIC; X.M., D.K., I.C., C.L. and H.H. discussed the results; D.K. and X.M. wrote the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the writing; D.K. and H.H. supervised the projects.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent is published on this technology (WO/2024/175809; priority 24.02.2023; assignee: DTU; inventors: X.M., D.K. and H.H.). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, X., Kong, D., Kim, K. et al. Digital-analog hybrid matrix multiplication processor for optical neural networks. Nat Commun 16, 7465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62586-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62586-0

This article is cited by

-

Multiplying matrices in a single pass with light

Nature Photonics (2026)