Abstract

In response to the growing burden of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer, this study investigated clearance of oral HPV, the obligate precursor, in a longitudinal cohort of men from the US, Brazil, and Mexico. Oral gargles collected every 6 months from the HPV Infection in Men Study were HPV genotyped using SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25. Oral HPV infection clearance and associated factors were assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards models, respectively. Median follow-up was 44.8 months with 403 and 186 men with an incident and prevalent oral HPV infection, respectively; and lower probability of clearance observed in prevalent infections. Infections were less likely to clear in the presence of increased sexual behaviors; and among prevalent infections, older men were less likely to clear their infection. Here, we report differences in prevalently and incidently detected infections with sexual behavior as a key factor and older age as a potential factor associated with clearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As smoking use has decreased, so too have the head and neck cancers cancers (HNC) associated with it. However, one such cancer, oropharyngeal cancer (OPC), has increased in recent years due to a second etiological cause of OPC that is increasing worldwide—oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Both oral HPV prevalence and HPV-associated OPC incidence is higher among men than women1,2. The United States reported significant increases in HPV-associated OPC since the mid-2000s with rates currently nearing 22 and 28 per 100,000 among men aged 45–64 and older than 65, respectively3. In the U.S. and other high-resource countries, HPV-associated OPC now surpasses cervical cancer as the leading cause of cancer attributable to HPV4.

Unlike other HPV-associated cancers there is no reliably detected precursor lesion for HPV-associated OPC, thus inhibiting prevention via screening. However, it is known that 90% of HPV-associated OPC is caused by HPV type 16 and that persistence of HPV infection of an oncogenic type (types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) is the obligate precursor to HPV-associated OPC5. As such, type-specific persistence of 6-months or longer has been approved for use as an endpoint in Phase III vaccine trials testing the efficacy of the vaccine to prevent OPC6,7. However, many men are unvaccinated and, though vaccination in high-income programs targets both sexes, low- and middle- income countries predominantly vaccinate only young females. Further, vaccination remains lower in males (6%) than in females globally (20%)8, leaving multiple birth cohorts of males unprotected. Thus, there is a need for secondary prevention strategies, to identify those at high risk of OPC for active surveillancne, and to detect OPC early, particularly among males. To do so, the natural history of oral HPV must be well characterized. We have recently reported that incidence of an oral HPV infection with any oncogenic type did not vary by age and occurred at a constant rate over five years among men from the US, Brazil, and Mexico9. However, little is known regarding the duration of a prevalent (detected at baseline) and newly acquired oral HPV infection or the factors associated with clearance of each. Therefore, we sought to estimate the probability of clearing an oncogenic oral HPV infections in men and factors associated with clearance of each HPV infection type. In sub-analyses, we also investgated factors associated with timepoint persistence (6- and 12-months) of each to support a better understanding of the defined clinical endpoint (6-month persistence) used in HPV vaccine efficacy trials6,7.

Results

Oral oncogenic HPV infection clearance

There were 589 men identified as having a prevalent (HPV detected at the first study visit) or incident (HPV acquired during the follow-up period) oral HPV infection in The HIM Study (112 men with multiple infections detected) with a median follow-up time of 44.8 months. Among those men, there were 739 oncogenic oral HPV infections (HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) of which 533 were incident and 206 were prevalent. Among the incident oncogenic infections, 78% were transient and 6.6% persisted more than 24 months. In contrast, 47.1% of prevalent oncogenic infections were transient and 24.3% persisted more than 24 months. When considering HPV16 alone, 14.1% and 21.6% of incident and prevalent infections, respectively, persisted more than 24 months (Table 1).

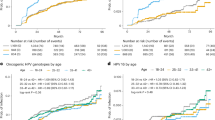

Probability of clearing an oral oncogenic HPV infection was significantly different for incident infections compared to prevalently detected infections (log-rank test test p < 0.001). Both infection types have a high proportion that resolve within 6 months (transient) with >95% of incident infections cleared at 78-months of follow-up as compared to 85% of prevalent infections (Fig. 1A). Among men with persistent infections (i.e. lasting at least 6months), probability of clearing an infection was not significantly different (log-rank test p = 0.21) between incident and prevalent infections. The probability of clearing an infection was similar in the first 18 months of follow-up. After 18 months the observed probability of clearing an incident infection was higher for the remainder of the study period (Fig. 1B).

Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank test investigated. A Clearance of an oral oncogenic HPV infection with a steep drop off is observed at the onset due to inclusion of transient infections. B Transient infections are excluded to determine clearance among only those infections that persisted 6 months or more.

Overall, probability of clearing an incident or prevalent infection was not different by age tertiles (Fig. 2). However, men in the oldest age group had reduced likelihood of clearance for both incident and prevalent detected infections. Among incident infections that persisted at least 6 months (Fig. 2B), median duration was longest in older men (age 17–30: 18 months, age 31–41: 17 months, and age >42: 34 months; Fig. 2B). Among prevalent detected infections, oral oncogenic HPV infection median duration was similarly longest in older men (age 17–27: <6 months, age 28–38:1.3 months, and age >39: 13 months, Fig. 2C). Among prevalent infections that persisted at least 6 months, median infection duration was 18, 40, and 20 months for young (17–27 years), mid- (28–38 years), and older (>39 years) men, respectively (Fig. 2D). In both infection types, probability of clearing an oral oncogenic HPV infection did not significantly differ by country of residence (incident: log-rank test p = 0.093 and prevalent: log-rank test p = 0.7) or smoking status (incident: log-rank test p = 0.8 and prevalent: long-rank p = 0.3).

Represented are number of infections, not number of men with an infection—men could have multiple infections. Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank test investigated. A Clearance of an incident oral oncogenic HPV infection, stratified by age group; B Clearance of an incident oral oncogenic HPV infection, stratified by age group, excluding transient infections; C Clearance of a prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection, stratified by age group; D Clearance of a prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection, stratified by age group (excluding transient infections).

Factors associated with clearance of an oral oncogenic HPV infection

Clearance was investigated among 403 men with an incident infection of which 97 (24%) persisted at least 6 months; and separately among 186 men with a prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection of which 103 (55%) persisted at least 6 months.

Incident infections

A lower proportion of Black men (13%) and men of other race (29%) had an infection that persisted at least 6 months compared to 50% of White men. Men who reported more lifetime female (33%) and male sexual partners (43%) had an infection that persisted at least 6 months compared to those reporting 0–2 female partners (2%) or 0 male partners (23%), respectivley. In both crude and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models for oral HPV clearance of an incident infection, no factors were significantly associated with clearance of an incident oral oncogenic HPV infection, though lifetime number of female sexual partners was marginally associated (aHR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.53–1.04) (Table 2). In Supplementary Table 1, we separately show the risk associated with an infection persisting to ≥6- and ≥12-months. A significantly increased risk of oral oncogenic infection persisting at least 6 months was observed among men of a race other than Black or White (aOR: 5.0; 95% CI: 1.8–14.2), non-Hispanic men (aOR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.1–4.2, current smokers (aOR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.03–3.5), and among men with a higher reported lifetime number of female (aOR: 2.7; 95% CI:1.1–6.6) and male sexual partners (aOR: 3.7; 95% CI: 1.7–7.9). A significant 3-fold increase in infection persistence for ≥12 months was observed among men reporting Other race (95%: 1.08–7.34) and men who reported more than 11 lifetime number of female sex partners (95% CI: 1.11–8.24). (Supplementary Table 1)

Prevalent infections

Among prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infections, a higher proportion of older men (age 17–27 years) (70%) had an infection that persisted at least 6 months compared to mid-age (28–38 years) (55%) and younger age (>39 years) (43%) men. In multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards models for clearance of prevalent oral HPV inffections, likelihood of clearing was lower for men aged >39 years (aHR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.34–0.96) compared to men aged 17–27; and among men who reported giving oral sex seven or more times in the past 6 months (aHR: 0.5; 95% CI: 0.3–0.9). Men who reported 3–11 (aHR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.1–3.4) and more than 12 female sex partners (aHR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.07–4.3) were more likely to clear an oral oncogenic HPV infection (Table 3). In Supplementary Table 2, we separately show the odds of a prevalent infection persisting to ≥6- and ≥12- months. A significantly increased risk of oral oncogenic infection persisting at least 6 months was observed among men >39 years (aOR: 4.5; 95% CI: 1.5–13.6) and men who reported giving oral sex more than 7 times in the past 6 months (aOR:2.6; 95% CI: 1.0–7.0) Risk of ≥12-month persistence was significantly 3–5 fold higher among older men (age 28–38 or >39) (95% CI: 1.06–8.38 and 1.82–15.54, respectively) compared to men aged 17–27, and more than 3-fold higher among men who reported more oral sex given in the past 6 months (aOR:3.24; 95% CI: 1.22–8.60).

When investigating clearance of oral HPV16 only, results were similar to those observed for clearance of an oncogenic oral HPV infection described above (Supplementary Table 3). There were no factors significantly associated with clearance of an incident oral HPV16 infection. Among prevalent HPV16 infections, older age was significantly associated with reduced clearance (aHR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.16–0.95 for age 42–73).

Discussion

This study reports the persistence and clearance of oral HPV infections among a longitudinal cohort of men from three countries. Oral HPV infections detected as prevalent, with an unknown infection history, were less likely to clear compared to infections newly acquired during the study follow-up, confirming they should be investigated separately. Among prevalent infections, older age and increased frequency of oral sex were significantly associated with lower likelihood of clearing an infection and timepoint persistenct of ≥6- and ≥12-months. Among incident infections, men with a larger number of lifetime female partners were less likely to clear their infection (aHR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.53–1.04) though this did not reach statistical significance. Men reporting other race, non-Hispanics, current smokers, and men reporting a larger number of male or female sexual partners had increased risk of an incident infection persisting ≥6 months. Similar results were observed for factors associated with persistence of oral HPV 16 infection.

We separately investigated and observed differences in probability of clearance of an oncogenic oral HPV infection among incident and prevalent infections (median duration of 0 and 6 months, respectively; and 20 and 24 months, respectively among men who persisted 6 months or more). In the same HIM Study cohort, 6–8 months for genital HPV infections was observed and decreasing with increasing age10. At the anus, a median duration of 6–9 months after an incident infection and 13–27 months after a prevalent infection was observed11. D’Souza and colleagues recently reported a median oncogenic oral HPV duration of 14 months combining incident and prevalent infections, using the same definition for clearance as our study (i.e. two consecutive negative HPV tests) among people living with or at risk of HIV12. Similar to our study, they also observed lower liklihood of clearance among prevalent infections and among older participants12. We observed non-conclusive patterns in oral oncogenic HPV infection clearance by age. Among all incident infections, duration was not different by age, but was marginally different by age among men whose infections persisted at least 6 months. Among prevalent infections, duration was marginally different by age only when transient infections were included in analyses. However when modeled for an association with clearance, age was significantly, independently associated, a result that supports oral HPV surveillance at older ages when prevalent, long-lasting (>2years) infections may be of concern. Our results indicate age may be an important factor for oral HPV persistence, but the evidence is inconclusive given differences observed with incident vs. prevalent infections. As little is known regarding the timing of oral HPV acquisition10,11,12 definitive statements regarding age associations with lower rates of prevalent detected oncogenic oral HPV infections is not possible. However, our recent publication investigating oral HPV acquisition reported no difference in the rate of oral HPV acquisition across age groups9. With older age there is likely a decrease in immune function which may reduce ability to clear an oral HPV infection. In fact, D’Souza et al., also observed that people living with HIV, a known immunocompromised population, are less likely to clear an oral HPV infection12.

Overall, higher levels of sexual activity was a key factor associated with lower likelihood of oral oncogenic HPV clearance across both infections types. This was pronounced when persistence was assessed at key timepoints (≥6- and ≥12-month persistence) for both infection types. While previous studies both in The HIM Study9,13 as well as other cohorts14,15 have found similarly significant associations with oral HPV acquisition it is unclear how increased exposure via sexual acitivity may lead to a reduced ability to clear the infection and, in fact, may represent a repeated exposure to virus. Low seroconversion rates following an HPV infection16 occur in men and high risk of recurrence has been observed with genital HPV infections17, indicating a potential pathway between sexual activity and oral HPV persistence.

Unexpectedly, smoking was not associated with clearance of oral HPV. Although, among incident infections, smoking was significantly associated with persistence of ≥6-months, but not ≥12-months suggesting smoking may have an impact on short-term persistence. This is unlike results from studies of HPV at other anatomic sites18 including those from HIM Study investigations of genital HPV acquisition19 and persistence20. Smoking has been hypothesized to increase risk of acquisition and reduce clearance of oral HPV infections due to its’ ability to reduce immune function and specifically T cell function21,22, which is necessary to clear an HPV infection23. Last, our study observed an increased risk of ≥6- and ≥12-month persistence for White men and men reporting Other race, compared to Black men, similar to an Australian study24, but race was not associated with overall likelihood of clearance in Cox models. Of note, the patterns observed in our study for smoking and race are similar to the associations of these variables with HPV-OPC risk25,26. Other considerations, such as host immune function, HPV recurrence and/or latency, and duration from infection to HPV-OPC, neeed to be explored to fully understand natural history and progression to cancer.

A recent study concluded little benefit of vaccination in men beyond 26 years of age27 after simulated data observed 70% of oral HPV16 infections occurred by age 26. However, this was modeled on cross-sectional US prevalence studies rather than prospective cohorts.The findings of the current study surrounding older age warrants further consideration. Coupled with similar results from D’Souza et al., there may be a rationale for vaccination through age 45 to prevent oral HPV infections more likely to persist. This is further supported by our recent prospective study which concluded equal risk of oral HPV acquisition across the lifespan after observing no difference in acquisition of oral oncogenic HPV across age groups9.

While our study has several strengths due to the prospective cohort study design and long-term follow-up of over 3000 men, there are limitations to note. This was a comprehensive investigation of factors associated with oral HPV persistence and as such only a few self-reported factors representative of each risk category assessed at baseline (i.e. demographics, substance use, sexual behavioral, and oral health) were included in the models. With self-report there is an inherent risk of reporting and recall bias. To minimize bias, surveys were self-administered via computer in a private room and the same questions asked throughout follow-up. The oral gargles are collected every 6 months, thus the precise date of infection acquisition and clearance are unknown—a common limitation of longitudinal cohort studies. The methods for defining clearance of an oral HPV infection used in this study are consistent with those of others studies12,28. The specimen used to detect oral HPV DNA, the oral gargle, does not specifically target the oropharynx; prior studies have shown performance to be lower than measuring HPV directly in the tumor29. At this time, the oral gargle is the current standard for detection of oral HPV in cancer free popualtions. Further, the SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LIPA25 assay, a sensitive and robust test for HPV genotyping, was utilized on all oral specimens in the same laboratory.

This study evaluates the clearance and investigate the factors associated with clearance of an oral oncogenic HPV infection in a prospective study of healthy men from the US, Brazil, and Mexico. With follow-up of up to 8 years and oral HPV testing at six month intervals, it represents one of the largest and most comprehensive evaluations of oral HPV natural history to date. We observed differences in clearance and risk factors for incident versus prevalent infections which is an important consideration as more studies investigate and draw conclusions on oral HPV natural history. We found no factors to be significantly associated with the ability to clear a newly acquired infection. Whereas among prevalent infections, older age and more oral sex was independently significantly associated with clearance. Further study is clearly needed to disentangle host demographic and behavioral factors, as well as immune response and viral factors at play with oral HPV persistence to address the increasing incidence of HPV-related OPC in men.

Method

Study population

Participants for this study were recruited under the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study previously described9,30. In short, 4123 men, aged 18–70, were enrolled in 2005–2009 to study the natural history of HPV in men in Sao Paulo, Brazil; Cuernavaca, Mexico; and Tampa, US. They were eligible if they were negative for HIV and other STIs and had no prior history of penile or anal cancer or genital warts. Men were followed every six months through 2016. Ethical approval was received from Institutional Review Boards at University of South Florida (Tampa, FL, US), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (São Paulo, Brazil), Centro de Referência e Treinamento em Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis e AIDS (São Paulo, Brazil), and Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública de México (Cuernavaca, Mexico). All participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment and participation in any study activities.

Data pertaining to sociodemographics, sexual history, alcohol/tobacco use, and oral health were collected at each study visit via computer-assisted self-interview. Collection of an oral gargle began in 2007 and continued to be collected at each study visit. The current study was restricted to the HIM Study Oral Sub-cohort which included 3137 men with at least two oral gargle specimens collected throughout follow-up. From this group we included men who had an oral oncogenic HPV infection detected at their first oral gargle collection (baseline) and men who acquired an new oral oncogenic HPV infection during follow-up. Prevalent oral oncogenic HPV was detected among 186 men and incident onocogenic oral infections were detected among 403 men.

Sample collection and HPV testing

Collection and processing of oral gargle specimens for HPV testing has previously been described31. Briefly, participants rinsed their mouths and gargled for 30-s using 15 mL of locally available alcohol-free mouthwash (Brazil: PLAX; Mexico: Oral-B; US: Target Brand). Specimens were stored at −80 °C following processing. DNA was extracted from all archived oral specimens using the robotic MDx Media Kit (Qiagen), as instructed by the manufacturer. The HPV SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25, (DDL Diagnostic Laboratory, Rijswik, the Netherlands) line probe assay system that detects 25 HPV genotypes was used for HPV genotyping32,33. The SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 is the most suitable assay as it is a sensitive assay that detects 20% more HPV genotypes than other marketed assays, even in oral gargle samples where HPV target cells are diluted34. For quality control, amplification of the beta-globin gene was performed.

Study definitions

This study included oral HPV infections detected at baseline (“prevalent”) and newly acquired throughout follow-up (“incident”). The history of prevalent infections prior to study enrollment is unknown. Due to this and prior findings from D’Souza et al.12 which observed differences in clearance among prevalent vs. incident infections, we conducted all analyses separately for each infection type. An oral HPV infection was considered transient if the same HPV type identified at the intital detection (baseline for prevalent; first acquisition for incident) was no longer detected at the subsequent study visit. An oral HPV infection was considered cleared when the participant tested negative for that specific HPV type at two consecutive study visits, was HPV-type specific, and determined from the date of first detection to the date of last detection. Oral HPV persistence was defined as a type-specific HPV infection that was detected at one or more sequential visits. Genotype-specific oral HPV infections were reported by type and further grouped as follows: any 1 of 25 HPV types, oncogenic types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68), non-oncogenic types (6, 11, 34, 40, 42, 43, 44, 53, 54, 70, and 74).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses specifically investigated oral HPV infection of an oncogenic type. Probability of clearing of an oral oncogenic HPV infection was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank test test. Type-specific HPV infection was the analytical unit (i.e. it is possible to have more infections than participants due to multiple infections) in order to understand clearance of the infection itself and because some participants had multiple infections with different time to clearance. First, to confirm differences by infection type, KM curves were generated comparing prevalent vs. incident infections. Subsequent investigations were investigated in each infection type separately by age tertiles, country of resident and smoking. Due to a high proportion of transient infections, investigations both including and excluding transient infections were conducted to better estimate probability of clearance among the non-transient infections.

Among both types of infection and separately among HPV16 infections only, differences in sociodemographic and behavioral factors were investigated among participants whose oral oncogenic HPV infection persisted 6 months or longer vs those whose did not persist (transient infections) using Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. To investigate the participant-level factors (sociodemogaraphics and behavioral patterns) associated with clearance of a prevalent or incident infection, Cox proportional hazards models were used among incident and prevalent infections separately. Both unadjusted, crude models and adjusted models using backwards selection (p < 0.2) were used with time to clearance (as defined above) or last study visit. These studies included person-level data (i.e. a man’s sexual history) assessed from the baseline and follow-up questionnaires and therefore, the participant was the analytical unit. In the event of multiple oral HPV infections throughout follow-up, only the first incident infection was considered. In the event of multiple concurrent oral HPV infections, the longest infection duration was analyzed. This scenario was not common but sensitivity analyses utilizing the shortest duration were conducted and no difference in results was observed. We additionally investigated the affect of concurrent infections on clearance and observed no significant association (Incident infections: HR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.88–1.42; Prevalent infections: HR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.74–1.69).

Persistence of >6 months is utilized as the endpoint in study inverventions for primary oral HPV prevention6,7. We therefore also investigated associations with persistence as a categorical variable (yes/no) at ≥6-months as well as one timepoint beyond (≥12-months) (supplementary tables) to understand the factors associated with a prevalently detected or newly acquired infection persisting surrounding the clinical endpoint of interest. Again, the participant was the analytical unit using the same logic for multiple infections as described above. Factors associated with a persistent oral oncogenic HPV infection to 6- and 12-months were assessed in crude and adjusted logistic regression models using backwards elimination (p < 0.2) separately for prevalent and incident infections. SAS 9.4 and R 4.4.0 were used for data management, cleaning, and analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data relevant to this manuscript are included in the article. The authors have also prepared a minimal de-identified data set, necessary to interpret, replicate and build on the findings reported in the paper. The dataset are stored at Moffitt Cancer Center’s internal HIM Study cohort data repository. Due to the sensitive nature of the data, interested parties may request access to the deidentified data by contacting the corresponding author, A.R.G., Center for Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, Florida 33612, United States. Email: anna.giuliano@moffitt.org. Kindly anticipate a response within 3-4 weeks.

Code availability

No custom code was developed. Analyses scripts have also been prepared on SAS version 9.4 for future referencing. The scripts are stored at Moffitt Cancer Center’s internal HIM Study cohort data repository. Due to the sensitive nature of the data, interested parties may request access to the scripts by contacting the corresponding author, A.R.G., Center for Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, Florida 33612, United States. Email: anna.giuliano@moffitt.org. Kindly anticipate a response within 3-4 weeks.

References

Chaturvedi, A. K. et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 4550 (2013).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249 (2021).

Guo, F., Chang, M., Scholl, M., McKinnon, B. & Berenson, A. B. Trends in oropharyngeal cancer incidence among adult men and women in the United States from 2001 to 2018. Front. Oncol. 12, 926555 (2022).

Van Dyne, E. A. Trends in human papillomavirus–associated cancers—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 67, 918–924 (2018).

Kreimer, A. R. et al. Oral human papillomavirus in healthy individuals: a systematic review of the literature. Sexually Transmitted Dis. 37, 386–391 (2010).

Nine-valent HPV vaccine to prevent persistent oral HPV infection in men living with HIV, https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04255849 (2025).

Efficacy against oral persistent infection, immunogenicity and safety of the 9-valent human papillomavirus vaccine (9vHPV) in men aged 20-45 years (V503-049). https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04199689 (2025).

World Health Organization. HPV Dashboard, https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/human-papillomavirus-vaccines-(HPV)/hpv-clearing-house/hpv-dashboard (2025).

Mandishora, R. S. et al. Multi-national epidemiological analysis of oral Human Papillomavirus Incidence in 3137 men. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 2836–2846 (2024).

Ingles, D. J. et al. An analysis of HPV infection incidence and clearance by genotype and age in men: the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. Papillomavirus Res. 1, 126–135 (2015).

Nyitray, A. G. et al. Incidence, duration, persistence, and factors associated with high-risk anal human papillomavirus persistence among HIV-negative men who have sex with men: a multinational study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, 1367–1374 (2016).

D’Souza, G. et al. Oncogenic Oral Human Papillomavirus Clearance Patterns over 10 Years. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 33, 516–524 (2024).

Bettampadi, D. et al. Differences in factors associated with high-and low-risk oral human papillomavirus genotypes in men. J. Infect. Dis. 223, 2099–2107 (2021).

Chaturvedi, A. K. et al. NHANES 2009–2012 findings: association of sexual behaviors with higher prevalence of oral oncogenic human papillomavirus infections in US men. Cancer Res. 75, 2468–2477 (2015).

Pickard, R. K., Xiao, W., Broutian, T. R., He, X. & Gillison, M. L. The prevalence and incidence of oral human papillomavirus infection among young men and women, aged 18–30 years. Sex. Transmitted Dis. 39, 559–566 (2012).

Giuliano, A. R. et al. Seroconversion following anal and genital HPV infection in men: the HIM study. Papillomavirus Res. 1, 109–115 (2015).

Pamnani, S. J. et al. Recurrence of genital infections with 9 human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) among men in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. J. Infect. Dis. 218, 1219–1227 (2018).

Antonsson, A. et al. Natural history of oral HPV infection: longitudinal analyses in prospective cohorts from Australia. Int. J. Cancer 148, 1964–1972 (2021).

Schabath, M. B. et al. Smoking and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in the HPV in Men (HIM) Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 21, 102–110 (2012).

Schabath, M. B. et al. A prospective analysis of smoking and human papillomavirus infection among men in the HPV in Men Study. Int. J. Cancer 134, 2448–2457 (2014).

Geng, Y., Savage, S. M., Razani-Boroujerdi, S. & Sopori, M. L. Effects of nicotine on the immune response. II. Chronic nicotine treatment induces T cell anergy. J. Immunol. 156, 2384–2390 (1996).

Sopori, M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 372–377 (2002).

de Gruijl, T. D. et al. Differential T helper cell responses to human papillomavirus type 16 E7 related to viral clearance or persistence in patients with cervical neoplasia: a longitudinal study. Cancer Res. 58, 1700–1706 (1998).

Ju, X. et al. Natural history of oral HPV infection among indigenous South Australians. Viruses 15, 1573 (2023).

Lorenzoni, V. et al. The current burden of oropharyngeal cancer: a global assessment based on GLOBOCAN 2020. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 31, 2054–2062 (2022).

Lechner, M., Liu, J., Masterson, L. & Fenton, T. R. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 306–327 (2022).

Landy, R. et al. Upper age limits for US male human papillomavirus vaccination for oropharyngeal cancer prevention: a microsimulation-based modeling study. JNCI J. Natl Cancer Inst. 115, 429–436 (2023).

Beachler, D. C. et al. Risk factors for acquisition and clearance of oral human papillomavirus infection among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 181, 40–53 (2015).

Martin-Gomez, L. et al. Oral gargle-tumor biopsy human papillomavirus (HPV) agreement and associated factors among oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) cases. Oral. Oncol. 92, 85–91 (2019).

Giuliano, A. R. et al. The human papillomavirus infection in men study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 17, 2036–2043 (2008).

Kreimer, A. R. et al. The epidemiology of oral HPV infection among a multinational sample of healthy men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 20, 172–182 (2011).

Kleter, B. et al. Novel short-fragment PCR assay for highly sensitive broad-spectrum detection of anogenital human papillomaviruses. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1731–1739 (1998).

Geraets, D. T. et al. The original SPF10 LiPA25 algorithm is more sensitive and suitable for epidemiologic HPV research than the SPF10 INNO-LiPA extra. J. Virological Methods 215, 22–29 (2015).

Bettampadi, D. et al. Oral HPV prevalence assessment by linear array vs. SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 system in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study. Papillomavirus Res. 9, 100199 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the HIM Study teams and participants in the United States (Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa), Brazil (Centro de Referência e Treinamento em DST/AIDS, Fundação Faculdade de Medicina Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo) and Mexico (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01CA214588 (ARG). This work has been supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Additional support was provided by A.R.G.’s American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.G. designed and leads the HIM Study as the Principal Investigator (PI). L.L.V. and E.L.-P. contributed to the design and implementation of the HIM Study at their respective countries as site PIs. A.R.G., K.I.-S., and B.S. were responsible for the oral HPV sub-study sample and data collection. B.L.D., B.S., and A.R.G. designed the research analysis. W.F. and B.S. performed the statistical analysis and created visuals under the direction of A.R.G., B.L.D., R.R.R. and M.J.S. A.R.G., R.D.M. and B.L.D. interpreted the data and B.L.D. drafted the manuscript. All co-authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.R.G. reports grants from Merck & Co, personal fees from Merck & Co outside the submitted work. L.L.V. is an occasional speaker for HPV prophylactic vaccines of Merck, Sharp & Dohme. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dickey, B.L., Dube Mandishora, R.S., Sirak, B. et al. Persistence and clearance of oral human papillomavirus among a multi-national cohort of men. Nat Commun 16, 8816 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62963-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62963-9