Abstract

Terpene cyclases catalyze exquisite and complicated cyclization reactions to generate diverse terpenoid skeletons. Trichoderma fungi are important biocontrol agents, characteristic of producing complex bioactive tetracyclic diterpenoids named harzianes and trichodermanins, but their biosynthesis and biological functions have long been enigmatic. Here we identify TriDTCs, an unprecedented family of terpene cyclases in Trichoderma, responsible for cyclizing geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) into major diterpenes harzianol I and wickerol A, via heterologous expressions, gene deletion, and in vitro assays. TriDTCs represent a brand new class of terpene cyclases, lacking known motifs and diverging from all known enzymes. Mechanistically, TriDTCs likely employ a unique DxxDxxxD aspartate triad for cyclization initiation, a critical valine residue modulating product specificity, and “gatekeeper” residues for activity. Phylogenetic analysis shows TriDTCs have a narrow distribution in three fungal genera and are highly functionally specific within Trichoderma, suggesting a genus-specific acquisition and independent evolution. Functional studies implicated TriDTCs in fungal survival strategies by regulating formation of resistant propagules (chlamydospore in Trichoderma, sclerotia in Aspergillus oryzae). These findings expand the knowledge of terpene cyclase diversity and biological significance, herald a strategy to enhance Trichoderma’s biocontrol efficacy, and open avenues for pharmacological investigation of these diterpenoids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Terpenoids constitute the largest family of natural products, with over 100,000 members identified from various organisms (dnp.chemnetbase.com)1. They possess important biological functions and participate in the growth and survival process of the organisms that produce them, such as serving as membrane components (e.g., hopanoids, sterols), hormones (e.g., gibberellins, sobralene2,3), defensive chemicals (e.g., pyrethrins, trichothecenes4, sesterterpenoids5), and pigments (e.g., carotenoids). Their structural complexity also underpins the pharmaceutical significance, exemplified by clinical medicines such as Taxol and artemisinin. Terpenoid biosynthesis begins with C5 isoprenoid units, which are assembled into acyclic pyrophosphate precursors (C5n) and subsequently cyclized by terpene cyclases (TCs) to form intricate carbocyclic scaffolds. The catalysis of TCs starts with the formation of carbocation, which triggers a cascade of electron flow and carbon–carbon bond formation to generate fused rings and stereocenters. Based on different carbocation-initiating mechanisms, canonical TCs are categorized into type I and II, featuring specific conserved catalytic motifs: type I enzymes typically contain Mg2+-binding DDxxD and NSE/DTE motifs, while type II TCs utilize a DxDD motif. Recently, noncanonical TCs lacking these motifs, such as YtpB and AsR66,7 classified as type I TCs from uncharacterized protein families, have expanded our understanding of TC diversity8. However, the cryptic nature and unpredictable functions of these noncanonical TCs present major challenges for their discovery and characterization.

Fungi possess specialized machinery to produce diverse terpenoids with unique chemical structures and significant biological functions4. For instance, farnesol acts as a communication molecule in Candida albicans9, while austin, ophiobolins, and trichothecenes serve as defensive chemicals in their producing fungi10,11,12. The genus Trichoderma (Hypocreales, Ascomycota) stands out among fungi with its prominent environmental adaptability, which thrives across diverse habitats ranging from terrestrial soils to marine ecosystems and even acts as an opportunistic human pathogens13. Trichoderma species are widely used as biocontrol agents (BCAs) due to their rapid growth, prolific propagation, and versatile biocontrol traits, making them one of the most promising microorganisms for eco-sustainable agriculture14. Trichoderma produces three types of asexual propagules, including chlamydospores, conidiospores, and mycelia, which confer a competitive advantage in occupying ecological niches15. Among these, chlamydospores exhibit strong resistance to adverse environmental conditions, which greatly enhances Trichoderma’s biocontrol efficacy16,17.

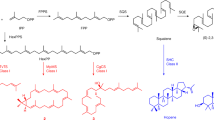

Trichoderma is a rich source of terpenoids18, particularly the characteristic harziane and trichodermanin diterpenoids, which are exclusively reported from Trichoderma species. Harzianes feature a characteristic 4/7/5/6-fused tetracyclic scaffold, with more than 40 members having been identified from various Trichoderma species (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, trichodermanins have a 6/5/6/6 ring system, with 8 compounds identified (Supplementary Fig. S2). These diterpenoids display extensive significant biological activities, including antifungal, anti-HIV, cytotoxic, and phytotoxic effects18. The biosynthesis of Trichoderma diterpenoids has attracted considerable interest. Previous studies on the cyclization mechanism employing 13C- and 2H-labeled substrates suggest that they are biosynthesized from geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) via type I carbocation-initiated reactions (Fig. 1a)19,20. However, further elucidation of the enzymes responsible for their biosynthesis has confronted significant challenges since their first discovery in 199221, despite the availability of 151 genome sequences covering 34 Trichoderma species and the identification of several TCs involved in sesquiterpenoid biosynthesis22,23,24. In addition, although the pharmacological activities of these unique diterpenoids have been extensively investigated, their biological functions in Trichoderma fungi remain unknown.

The cyclization mechanism of harzianes (1) and trichodermanins (2) from GGPP catalyzed by TriDTCs is indicated by plain arrows. WMR: Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement. The proposed biosynthetic pathway of harzianone (3) and harziandione (4) is indicated by dotted arrows. a–f are intermediates in the cyclization process.

In this study, employing an enzymatic activity-guided protein fractionation strategy, we identified an unprecedented family of enzymes from Trichoderma fungi responsible for the biosynthesis of Trichoderma-characteristic diterpenoids, which we named TriDTCs (Trichoderma diterpene cyclases). Mutational experiments guided by structural simulations revealed a distinct yet convergent enzymatic mechanism. Phylogenetic analysis and homolog characterization uncovered the specific distribution and specialized function of TriDTCs in nature, suggesting their unique evolution in Trichoderma. Furthermore, we discovered that Trichoderma fungi employ these specific enzymes and the diterpenoid products to regulate chlamydospore formation. Moreover, this function, mediated by TriDTCs and harzianol I, could also be applied to promote sclerotia formation in Aspergillus oryzae.

Results

Mining and characterization of TriDTC for Trichoderma-characteristic diterpenoid biosynthesis

To explore the biosynthetic pathways of harzianes and trichodermanins, we performed genome sequencing of T. atroviride B7, an endophytic fungus isolated from the medicinal plant Colquhounia coccinea var. mollis, which produces these diterpenoids25. AntiSMASH analysis predicted eight biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) related to terpenoid biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Table S1). Among these, the candidate gene triTPS8 showed 89% sequence identity to the characterized trichobrasilenol synthase (TaTC6)23. Five additional genes encoding isoprenoid synthase domain-containing proteins were also recognized from the genome (Supplementary Table S1). All 12 candidates (excluding triTPS8) were cloned and heterologously expressed in both engineered E. coli BL21 and filamentous fungal host A. oryzae NSAR1. Thereinto, the engineered E. coli strain harboring pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS and pCDF-Duet1-crtE26 plasmids can provide sufficient acyclic terpene precursors, including farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) and GGPP. However, none of these constructs yielded harziane or trichodermanin diterpenes. In contrast, when triTPS4, a gene predicted to encode a GGPP synthase, was co-expressed with pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS in E. coli, geranylgeraniol (GGOH) was detected, confirming that triTPS4 encodes a functional GGPP synthase (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Given that the scaffolds of harzianes and trichodermanins may be synthesized by noncanonical TCs, we performed enzymatic activity-guided protein fractionation combined with comparative transcriptomic analysis to identify the target enzyme. Firstly, an enzymatic assay approach was established using crude protein extracts from T. atroviride B7 with GGPP as the substrate. Two enzymatic products were detected, which were then traced and purified from the fermentation broth of T. atroviride B7 and identified as harzianol I (1) and wickerol A (2) through comparing their 1H and 13C NMR spectra with spectroscopic data in the literature (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figs. S5, 37‒40)25. Notably, this enzymatic activity was Mg2+-dependent (Supplementary Fig. S6). Next, the crude protein was subjected to sequential fractionation using ammonium sulfate precipitation (ASP) and ion-exchange chromatography (IEC), which afforded three highly active fractions and one weakly active control fraction (Supplementary Fig. S7). LC–MS/MS analysis of the four fractions, referenced against the T. atroviride B7 genome, identified 731, 579, 702, and 647 proteins, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Meanwhile, we attempted to culture T. atroviride B7 in different broth media and found that TB3 broth could produce diterpenoids 1‒4, while CD broth did not (Supplementary Fig. S8). Compound 3 was determined as harzianone through purification from T. atroviride B7 fermentation broth and comparison of its NMR data with those in literature (Supplementary Figs. S41, 42)27, while compound 4 was identified as harziandione through comparing retention time and MS spectrum with an authentic sample previously isolated from this strain25. Transcriptome sequencing of the mycelia cultured in TB3 and CD broth, integrated with the protein LC-MS/MS results, yielded 49 differentially expressed candidate genes for further study (Supplementary Data File 1).

a GC–MS extracted ion chromatogram (EIC, m/z 272) of enzymatic assays using T. atroviride B7 protein extracts: (i) Crude protein incubated with GGPP; (ii) Purified compound 1 standard; (iii) Purified compound 2 standard; (iv) Heat-inactivated control (boiled crude protein with GGPP); (v) Negative control (crude protein without GGPP). b EIC (m/z 272) of heterologous expression products in E. coli BL21 strains containing: (i) pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS, pET-28a-triTPS4, and pCold-TF-tri4155; (ii) pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS, pCDF-Duet1-crtE, and pCold-TF-tri4155; (iii) pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS, pCDF-Duet1-crtE, and pET-28a-tri4155; and (iv) pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS and pET-28a-triTPS4. Peak in the yellow column is GGOH. c Functional analysis in A. oryzae NSAR1 systems containing: (i) PTAex3-Ptri4155-tri4155, (ii) PTAex3-PamyB-tri4155, and (iii) PTAex3 (negative control). d In vitro enzymatic tests using TriDTCs purified from E. coli system: (i) Tri4155 incubated with GGPP; (ii) Tri4155V409A/L335A with GGPP; (iii) Tcie612 with GGPP; (iv) Boiled Tri4155 with GGPP.

These candidates were cloned from T. atroviride B7 cDNA and expressed in the engineered E. coli BL21 system. Among them, only tri4155, annotated as a hypothetical gene with FPKM values of 341.2 in TB3 and 7.8 in CD broth, produced trace amounts of compound 1 when expressed using the pET-28a vector (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data File 1). Switching the expression vector of tri4155 from pET-28a to pCold-TF and co-expressing with triTPS4 for GGPP biosynthesis boosted 1 production, with the yield of 3.55 ± 0.85 mg L−1 in the shake flasks, and compound 2 was produced as a minor product with a yield of 0.20 ± 0.05 mg L−1 (Fig. 2b and Fig. 3c). Although both CrtE and TriTPS4 can provide the GGPP precursor, the higher yield observed with co-expression of tri4155 and triTPS4 suggests potential synergistic catalysis between these Trichoderma-derived enzymes. Furthermore, tri4155 was introduced into A. oryzae NSAR1 under the constitutive promoter PamyB, resulting in the production of trace amounts of 1 (Fig. 2c). Replacing PamyB promoter with the native promoter Ptri4155 (700 bp sequence upstream of tri4155) markedly increased the production of 1 and 2, yielding 10.09 ± 2.08 mg L−1 and 1.55 ± 0.39 mg L−1, respectively (Figs. 2c and 4d). In addition, in situ knockout of tri4155 in T. atroviride B7 using a split-marker homologous recombination strategy abolished the production of 1 and 2 (Supplementary Figs. S9, S10). Notably, the activity of Tri4155 depends on the presence of Mg2+ (Supplementary Fig. S11), consistent with the Mg2+-dependence observed in crude protein extracts from T. atroviride B7. However, the recombinant Tri4155 protein purified from E. coli exhibited relatively low enzymatic activity (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. S11), and the expression level of C-terminal 8×His-tagged Tri4155 in A. oryzae NSAR1 was low (Supplementary Fig. S12), limiting its use for detailed biochemical analysis

a Structure model of Tri4155 predicted by AlphaFold2 and docked with GGPP substrate (pyrophosphate group shown in red). b Predicted catalytic cavity residues with a docked GGPP. Residue carbons in the highly charged and hydrophobic regions are shown in yellow and green, respectively. c Production of compounds 1 and 2 by Tri4155 variants expressed in E. coli BL21, showing differential effects of residues in highly charged and hydrophobic regions. Productions are represented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

a Neighbor-joining tree of TCs including: TriDTCs (red), canonical type I TCs from bacteria (purple), fungi (brown), plants (green), and octocorals (yellow), as well as noncanonical TCs (pink). b Expanded view of the TriDTC clade with characterized enzymes labeled. The functional members are highlighted in red. c In vivo enzymatic production of compounds 1 and 2 by TriDTCs expressed in E. coli BL21 system. d Production of compounds 1 and 2 by TriDTCs expressed in A. oryzae NSAR1 system. Productions are represented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

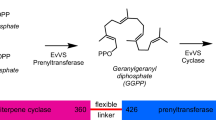

To enable more robust in vitro enzymatic characterization of TriDTC, the T. citrinoviride homolog Tcie612 was selected for heterologous expression. Tcie612 shares 60.41% sequence identity with Tri4155 and exhibited significantly enhanced yield of 1 when expressed in the E. coli system (33.34 ± 4.71 mg L−1), despite no previous reports of these compounds in T. citrinoviride. When incubated with GGPP and Mg2+, the recombinant Tcie612 protein produced compound 1 with improved production compared to Tri4155 (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. S11), but failed to produce compound 2 either in vitro or heterologously expressed in E. coli or A. oryzae, suggesting the functional divergence of Tcie612 and Tri4155 that warrants further investigation. To determine the substrate specificity, Tcie612 was incubated with FPP or GFPP, but no cyclized product was detected, indicating that Tcie612 is GGPP specific (Supplementary Fig. S11). Additionally, incubation of Tcie612 either with DMAPP and three equivalents of IPP, or with equal equivalents of FPP and IPP, did not yield any specific product, revealing that Tcie612 is a monofunctional diterpene cyclase (DTC), unlike fungal chimeric DTCs that possess both prenyltransferase and terpene synthase domains. In addition to Mg2+, some TCs can utilize other divalent metal cofactors28,29, such as Mn2+ and Co2+. We then tested the enzyme activity of Tcie612 with GGPP as a substrate in the presence of various metal ions, which revealed the following activity preference: Mg2+ > Co2+ > Mn2+ = Fe2+ (Supplementary Fig. S11). To determine the number of metal ions per enzyme, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were applied. When titrating Tcie612 pre-incubated with GGPP using MgCl2 solution, exothermic signals were observed, corresponding to Mg2+ binding. The data analysis revealed two Mg2+ and one GGPP binding per enzyme, consistent with docking results (Supplementary Fig. S13). Interestingly, no binding effect was observed when titrating Tcie612 without GGPP incubation, revealing that Mg2+ binding depends on both the enzyme and substrate presence (Supplementary Fig. S13). The kinetic parameter of Tcie612 for GGPP was also measured, with a KM value of 86.1 ± 8.19 μM (Supplementary Fig. S14). Collectively, the results of heterologous expressions in E. coli and A. oryzae NSAR1, gene deletion in T. atroviride B7, and in vitro enzyme assays indicated that Tri4155 and Tcie612 are responsible for the biosynthesis of Trichoderma-characteristic diterpenoids.

TriDTCs possess a distinct yet convergent catalytic mechanism

Tri4155 was initially annotated as a hypothetical protein, and it lacks the conserved motifs of classical type I and II TCs, such as DDxxD, NSE/DTE, RY pairs, and DxDD. Moreover, InterProScan analysis revealed that Tri4155 does not contain conserved domains characteristic of any known protein families30. Phylogenetic analysis of Tri4155, alongside classical type I DTCs from fungi, bacteria, plants, and marine organisms, as well as previously reported noncanonical TCs, showed that Tri4155 is phylogenetically distinct from classical type I DTCs and does not cluster with any known noncanonical TCs (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S15). Therefore, Tri4155 represents a novel family of TCs, which we named TriDTC. Interestingly, phomactatriene synthase (PhmA)31 and taxadiene synthase (TXS)32, which likely produce a common intermediate, verticillen-12-yl cation, with TriDTC during their cyclization process (Supplementary Fig. S16), are found in separate clades in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4a). TXS clusters with the classical TCs characterized by conserved motifs, while PhmA represents a divergent TC subfamily lacking RY pairs.

To elucidate the catalytic mechanism of TriDTC, we initially attempted to determine the crystal structure of Tri4155. However, the recombinant protein expressed in E. coli system was unstable and tended to aggregate. As an alternative, we turned to conduct a protein structure prediction on Tri4155 using AlfhaFold2, generating a simulated model (Fig. 3a). The substrate binding pockets of the model were analyzed, and GGPP was energy-minimized and docked into these predicted active cavities to generate an optimum pocket (Fig. 3b). Notably, the key residues in the pocket are within the highly conserved region across TriDTCs (Supplementary Fig. S21), indicating the reliability of the predicted catalytic cavity. To experimentally validate this model, we constructed 23 alanine-substitution variants targeting residues within the cavity. Among these, 17 variants exhibited either dramatically reduced or completely abolished diterpene production (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. S17), which further confirmed the reliability of the generated pocket. Compared to TXS, which has a larger active-site volume relative to its substrate GGPP, allowing for high intermediate flexibility and product promiscuity32, the active site contour of Tri4155 is markedly more compact and constrained (Supplementary Fig. S18), likely contributing to the strict substrate selectivity and product fidelity of Tri4155.

Like classical TCs, the predicted cavity of Tri4155 is bifacial, consisting of a highly charged region surrounding the pyrophosphate moiety at the entrance of the pocket and a hydrophobic region at the base (Fig. 3b). The highly charged region primarily consists of polar residues, and mutagenesis of these residues resulted in dramatic reduction or complete loss of diterpene production (Fig. 3c). Tri4155 lacks the classical metal-binding motifs typically found in TCs; instead, an aspartate triad (D445VGD448LCAD452) is positioned surrounding the pyrophosphate moiety, likely interacting with divalent metal ions to initiate allyl cation formation. Supporting this hypothesis, alanine substitutions of the aspartate triad (D445A, D448A, and D452A) completely abolished diterpene production. In contrast to TXS and other classical type I TCs that contain a conserved H-bonding cluster (YRRRY) in the cavity, appearing to bind bulk water to prevent premature carbocation quenching32, Tri4155 lacks this cluster, which may facilitate the formation of hydroxylated products. In the hydrophobic region, over half of the residues could be mutated with minimal impact on enzyme activity, while L335A and V409A variants actually enhanced diterpene production (Fig. 3c). In contrast, substitutions of aromatic residues with Ala (H318A, Y410A, and F321A) led to a substantial reduction in diterpene production, probably due to their essential roles in stabilizing intermediate cations via π–π and π–cation interactions. Compared to TXS containing four aromatic residues in the hydrophobic region proposed to stabilize the Δ9,10 position of verticillen-12-yl cation via π–π interaction and promote the cascade to cation g (Supplementary Fig. S16)33, Tri4155 contains only three aromatic residues that likely facilitate the conversion of verticillen-12-yl cation to intermediate b, which is subsequently converted into harzianes and trichodermanins. Two residues located at the entrance of the cavity, V412 and L317, appear to function as “gatekeepers” controlling substrate ingress. Alanine substitutions at these positions caused a drastic decrease in diterpene production (Fig. 3c), and structural modeling revealed the compromised cavity integrity in these variants (Supplementary Fig. S19). Conversely, the V412F and L317F variants partly restored compound 1 production and displayed constrictive cavity entrances in modeling studies. Notably, both V409A and L335A variants increased the production of minor product 2 (Fig. 3c), with V409A showing a more pronounced effect. The double variant L335A/V409A led to a further increase of compound 2 in both in vitro and in vivo tests (Figs. 2d and 3c). Structural modeling suggested that V409 was adjacent to the C-13 cation at intermediate c (Supplementary Fig. S20), likely engaging in a hydrophobic interaction that may influence substrate orientation. The V409A substitution likely weakened this interaction, thereby shifting the enzymatic product profile in favor of compound 2.

TriDTCs exhibit genus-specific function in Trichoderma

To investigate the evolutionary origin of Tri4155, we performed a BLASTP search using its amino acid sequence against the public nonredundant protein sequence database. A total of 38 homologous proteins were found, with sequence identities ranging from 47 to 97% (Fig. 4b). Notably, 25 homologous proteins were from the Trichoderma genus (Hypocreaceae), while 7 were from the Metarhizium genus (Clavicipitaceae) and 6 were from the Ophiocordyceps genus (Ophiocordycipitaceae). To further characterize their functions, we selected 13 representative homologs from Trichoderma, Metarhizium, and Ophiocordyceps, representing each differentiated branch in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. S21). These genes were codon-optimized and expressed in engineered E. coli BL21 harboring both pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS and pET-28a-triTPS4 plasmids. As a result, seven Trichoderma-derived homologs produced compounds 1 and 2, whereas the remaining homologs, including those from Ophiocordyceps and Metarhizium, showed no detectable enzyme activity (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. S22). In addition, all 13 homologous genes were expressed in A. oryzae NSAR1 under the control of the Ptri4155 promoter. The results were found to be similar to those observed in the E. coli system, that seven homologs from Trichoderma produce diterpenes, while the homologs from Metarhizium and Ophiocordyceps remained nonfunctional (Fig. 4d). Notably, the relative yields of the two products differed between the two heterologous systems, suggesting host-specific influences on enzyme performance.

Intriguingly, Metarhizium and Ophiocordyceps are genera known to colonize insects, while Trichoderma is considered to share a last common ancestor with entomoparasitic hypocrealean fungi34. Based on the distribution and function of TriDTC homologs across fungal genera, we proposed that TriDTCs originated from the Trichoderma genus, probably through de novo evolution from non-coding genomic regions. The acquisition of the TriDTC function likely occurred after the diversification into infrageneric groups, as some Trichoderma species harbor inactive TriDTC homologs. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) may have facilitated the introduction of TriDTC homologs into Metarhizium and Ophiocordyceps lineages; however, catalytic function appears to have been lost in these recipient genera. This proposed evolutionary trajectory is consistent with the highly specific distribution of harziane and trichodermanin diterpenoids. The gain of the TriDTC function during Trichoderma evolution may play an important role in environmental adaptation, potentially offering ecological advantages that contributed to the success of this genus in diverse habitats.

TriDTCs and harzianol I regulate Trichoderma chlamydospore and A. oryzae sclerotia formations

To explore the biological role of TriDTCs, we evaluated the growth rates of the wild-type (WT) and Δtri4155 T. atroviride B7 strains. The mutant strain exhibited an approximately 20% increase in growth radius compared to the WT strain after culturing on the PDA plates for two days (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S23). Considering that harzianes have been reported to possess anti-phytopathogenic activity in vitro, we conducted antagonism assays against the fungus Fusarium graminearum, a major causative pathogen of wheat scab. Consequently, both the WT and Δtri4155 strains inhibited the growth of F. graminearum, likely by rapidly occupying the growth niches (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S24), indicating that Tri4155 and its diterpenoid products are not essential for Trichoderma’s antifungal properties. Remarkably, after seven days of growth on PDA, WT strains developed dense white aerial hyphae containing large, spherical, and thick-walled chlamydospores at the tips of the hyphae, while the Δtri4155 strain failed to form chlamydospores but produced thinner aerial hyphae compared to the WT strain (Fig. 5c i, ii, Supplementary Figs. S25‒27). In addition, the hyphae of the mutant strain were more hydrophobic and displayed a greater number of short branches under the microscope (Supplementary Fig. S28). These results indicate that Tri4155 plays an important role in chlamydospore formation and hyphal morphogenesis.

a Colony growth comparison between wild-type (WT) and Δtri4155 T. atroviride B7 strains after 2 days of culture. The growth radius is represented as mean radius ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using t-test). b Antagonism assays of T. atroviride B7 against F. graminearum after 6 days: (i) WT T. atroviride (bottom) vs. F. graminearum (top); (ii) Δtri4155 mutant (bottom) vs. F. graminearum (top); (iii) self-pairing control of F. graminearum. c Fungal phenotypes after 7 days of culture: (i) WT showing normal hyphae and chlamydospores; (ii) Δtri4155 with aberrant hyphae and lacking chlamydospores; (iii) Δtri4155 supplemented with 10 μM compound 1 showing conidiation; (iv) Δtri4155 supplemented with 400 μM compound 1 restoring chlamydospore formation. scale bar = 50 μm. Each experiment contains more than 3 independent repeats. d Chlamydospore formation in T. asperellum and T. asperellum-ΔtriDTC (1-day culture), as well as in T. gamsii and T. gamsii-ΔtriDTC (3-day cultures). scale bar = 50 μm. Each experiment contains 3 independent repeats. e Sclerotia formation in A. oryzae NSAR1 (control), A. oryzae-tri4155 (heterologous expression of tri4155 gene), and A. oryzae treated with compound 1 (A. oryzae-S1) or 2 (A. oryzae-S2). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we conducted complementary experiments using compounds 1, 2, and 3 to test their rescue effects on chlamydospore formation. The results showed that all three compounds stimulated the Δtri4155 strain to form conidiospores in a concentration-dependent manner, with compound 1 being the most effective (Supplementary Figs. S26, S27). However, none of the compounds could rescue chlamydospores formation of the Δtri4155 strain at concentrations up to 40 μM. Given that the water solubility of compound 1 is poor, and higher concentrations should be needed to saturate the medium to attain an effective intracellular concentration, we increased the concentration of compound 1 to 400 μM in the medium and then inoculated the Δtri4155 strain. As anticipated, chlamydospore formation was rescued after seven days of culture (Fig. 5c iv), and the hyphae reverted to a less-branched morphology, resembling that of the WT strain (Supplementary Fig. S28). These findings suggest that tri4155 is involved in chlamydospore formation through producing harzianol I (1).

To verify the function of TriDTCs in Trichoderma species, four additional Trichoderma species were obtained and identified as T. asperellum, T. gamsii, T. reesei, and T. harzianum, respectively. When cultured in liquid media for three days, T. asperellum, T. gamsii, and T. atroviride B7 produced substantial amounts of harziane and trichodermanin diterpenoids 1‒4, while only trace amounts of these diterpenoids were detected in T. reesei and T. harzianum (Supplementary Fig. S29a). Microscopic observations revealed that T. asperellum, T. gamsii, and T. atroviride B7 formed chlamydospores, while no chlamydospore was observed in T. reesei or T. harzianum (Supplementary Fig. S29c). Solid media cultures showed similar trends, with T. asperellum and T. harzianum additionally producing abundant conidiospores (Supplementary Fig. S29b, c). These findings suggest that the chlamydospore formation depends on the diterpenoid production in Trichoderma species. Supplementation with 400 μM compound 1 significantly enhanced chlamydospore formation in T. harzianum. In T. reesei, compound 1 induced sclerotia-like hyphal aggregates in solid media, whereas in liquid culture, it promoted chlamydospore formation (Supplementary Fig. S30). To genetically validate these findings, the homologous genes of tri4155 in T. asperellum and T. gamsii were knocked out using a split maker strategy (Supplementary Fig. S31). The resulting mutants showed abolished diterpenoid production and impaired chlamydospore formation, accompanied by increased hyphae aggregation in liquid culture (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. S31), consistent with enhanced surface hydrophobicity.

We further tested the function of tri4155 and its products in the model filamentous fungus A. oryzae, which has an asexual reproduction cycle involving mycelia, conidiospores, and sclerotia. The sclerotia of A. oryzae are considered a degenerate sexual structure that no longer produces spores35 but forms a compact mass of hardened mycelia, allowing the fungus to survive in extreme environments36. In our observation, A. oryzae NSAR1 began to produce conidiospores after 1–2 days of culture on PDA plates. On day five, white sclerotia with highly branched hyphae formed peripherally to the conidiospore circle. These structures progressively turned into mature sclerotia with thick brown outer layers (Supplementary Fig. S32). In contrast, the strains heterologously expressing tri4155 produced significantly denser white sclerotia that preferentially overlying conidiospore circle by day five, with significantly smaller conidiospore circle (Fig. 5e). Similar to the effect of tri4155 heterologous expression, compound 1 also promoted sclerotia formation in A. oryzae, while compound 2 had no effect (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. S33). These results suggested that tri4155 promotes sclerotia formation through producing harzianol I, mirroring its role in Trichoderma.

Discussion

Although the rapid development of genome sequencing and bioinformatic technology has greatly promoted the identification of new biosynthetic enzymes of natural products, discovering noncanonical enzymes lacking typical conserved motifs remains a formidable challenge. Harzianes and trichodermanins have been reported from Trichoderma fungi for decades and exhibit various bioactivities, including antifungal and antiviral properties. Despite considerable efforts to elucidate their biosynthesis, the key enzymes have long been a mystery. In this work, we demonstrated an effective strategy for mining noncanonical enzymes. Using a combination of enzymatic activity-guided protein fractionation and comparative transcriptome analysis, verified by heterologous expression, gene deletion, and in vitro enzyme assays, we discovered a class of noncanonical enzymes, named TriDTCs, responsible for the formation of harziane and trichodermanin scaffolds from Trichoderma. This approach offers an effective complement to sequence mining in the study of natural product biosynthesis. Importantly, this study represents just one successful case, while fungal genomes contain numerous uncharacterized proteins and harbor vast, unexplored biosynthetic potential awaiting discovery.

TriDTCs represent an unprecedented subfamily of TCs that defy conventional classification. They represent an independent and unique branch of TCs, lacking all the conserved motifs of typical terpene synthases and highly differentiating from other noncanonical TCs, including YtpB and AsR6. Despite their highly divergent primary sequences, TriDTCs share fundamental mechanistic and structural features with TCs: (1) their enzymatic activity depends on divalent metals, (2) they possess bifacial catalytic cavities, (3) they employ an aspartate triad for metal binding, and (4) they adopt characteristic α-helical folds forming barrel-shaped cavities, according to the AlphaFold2 structural predictions and site-directed mutagenesis (Supplementary Fig. S34). However, TriDTCs contain significantly more loop regions compared to canonical TCs, and the spatial arrangement and orientations of the helices constituting the catalytic cavity differ considerably from those of known TC families. The structural divergences suggest that TriDTCs may have followed a distinct evolutionary trajectory from other type I TCs. Interestingly, despite pronounced structural differentiation, the shared structural features partially explain how TriDTCs, TXS, and PhmA utilize an identical substrate and initiate similar cyclization cascades, while variations in cavity architecture likely underlie their distinct product profiles, suggesting an intriguing mechanistic dimension that warrants future investigation. However, our mutagenesis studies failed to redirect product outcomes beyond harziane and trichodermanin scaffolds, indicating a high product fidelity of TriDTCs and a multifactor-controlled mechanism of the product specificity. More importantly, the common structural features shared between TriDTCs and other type I TCs (e.g., the α-helical folds and a barrel-shaped cavity) indicate the universal properties of all type I TCs and provide valuable insights for identifying additional noncanonical TCs based on protein structure simulation databases. However, in the absence of an experimentally resolved crystal structure and given that TriDTCs represent a novel protein family, the results of our structural predictions are still preliminary. Further experimental studies, such as X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM, would be essential to determine the structure of this unique enzyme family.

TriDTCs exhibit an unusually narrow taxonomic distribution, with functional activity largely restricted to Trichoderma species. We propose that TriDTCs might have originated de novo from non-coding genomic regions within the Trichoderma genus and gained function during evolution, as evidenced by their absence in closely related taxa and predominantly intron-less gene structures. The presence of catalytically inactive homologs in Metarhizium and Ophiocordyceps, two phylogenetically distant genera, probably resulted from HGT events. The non-Trichoderma TriDTCs lack three regions corresponding to the N-terminal loop of Trichoderma-derived TriDTCs (Supplementary Fig. S21), which we proved to be essential for enzymatic activity, as the N-terminal truncation Tri4155 variant (Tri4155Δ1–250) completely abolished compound production (Supplementary Fig. S35). Notably, Trichoderma homologues, such as Tvis324, possess the intact N-terminal loop but still exhibit no detectable activity, suggesting that other residues are also essential for enzymatic activity. Interestingly, although triDTC is not clustered with the GGPP synthase gene, the surrounding genomic regions in both T. atroviride B7 and T. asperellum harbor two putative cytochrome P450 genes, two FAD-binding genes, and one SAM-dependent methyltransferase gene that may participate in downstream metabolite biosynthesis, warranting further investigation (Supplementary Fig. S36).

While fungal natural products are often studied for their antimicrobial potential as defensive chemicals, relatively less attention has been devoted to understanding their roles in regulating fungal physiology. Although several metabolites have been implicated in fungal development, such as A. nidulans psi factor37, F. graminearum zearalenone38, A. terreus butyrolactone I39, and Penicillium cyclopium conidiogenone40, none have been reported to influence resistant propagule formation. Our work demonstrates that Trichoderma has evolved TriDTCs specifically to produce unique diterpenoids regulating chlamydospore development. While previous studies have reported the antifungal activity of harzianes, our findings indicated that these chemicals function primarily in physiological regulation rather than defense. Although TriDTCs naturally function only in the Trichoderma genus, their heterologous expression in A. oryzae significantly improved sclerotia formation. Chlamydospores and sclerotia are two kinds of resistant propagules widely existing in filamentous fungi, enabling them to adapt to extreme environmental conditions. Our results indicate a conserved regulation pathway underlying the formation of chlamydospores and sclerotia. While previous research has reported the involvement of velvet family proteins in the regulation of sporulation and morphogenesis in T. reesei41, and G-protein signaling pathway in A. oryzae sclerotia formation42,43, the molecular mechanisms governing chlamydospore formation remain completely unexplored. Our work provides the first molecular handle for investigating this important fungal survival strategy, and TriDTCs and harzianol I hold promise for improving fungal viability during long-term storage.

In summary, by integrating enzymatic activity-guided protein fractionation, comparative transcriptome analysis, in vivo and in vitro enzymatic assays, and in situ gene knockout, we demonstrated that Trichoderma fungi employ an unprecedented family of enzymes, named TriDTCs, to catalyze the formation of the characteristic, harziane and trichodermanin diterpenoids. Structural modeling and site-directed mutagenesis demonstrated the catalytic mechanism, identifying the DxxDxxxD Asp-triad, V409, and the “gatekeeper” residues crucial for enzyme activity and product profile. Phylogenetic analysis and homolog characterization revealed the specific distribution and highly functional specificity of TriDTCs in Trichoderma. Biological function research through gene deletions, heterologous expression, and compound supplementation revealed that TriDTCs and their products regulate the formation of fungal-resistant propagules. In addition, we identified a GGPPS and a promoter from Trichoderma fungi for heterologous production of harziane and trichodermanin diterpenoids. Our study exemplifies how fungi have evolved specialized biosynthetic enzymes to produce physiologically important chemicals as survival strategies. These findings shed new light on the biosynthetic machinery and biological functions of fungal terpenoids, herald a promising strategy to enhance the biocontrol efficacy of Trichoderma fungi in agricultural practices, and open avenues for producing these unique natural products for further pharmaceutical investigation and applications.

Methods

General methods

GC-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890 A GC system equipped with an Agilent 5795 C Inert MSD Triple-Axis detector and a 30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm column, with high-purity helium as the carrier gas. The temperature program was as follows: 80–220 °C at 15 °C min−1, then 220–270 °C at 4 °C min−1, followed by a 2 min hold. The flow rate was maintained at 1.2 mL min−1, with 5 μL injections in splitless mode. The inlet and detector temperatures were set at 250 °C and 300 °C, respectively. Column chromatography was performed using 200–300 mesh silica gel (Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory), and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted on silica gel plates (GF254, 10–40 μm). TLC spots were visualized under UV light or by heating after spraying with 10% H2SO4 in EtOH (v/v). Analytical grade solvents (n-hexane, petroleum ether, EtOAc) were used for extraction and analysis. NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE III-600 spectrometer using TMS as an internal standard.

E. coli cultures used TB broth (12 g L−1 tryptone, 24 g L−1 yeast extract, 25 mL L−1 glycerol, 2.31 g L−1 KH2PO4, 12.54 g L−1 K2HPO4), while protein purification employed LB broth (10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 10 g L−1 NaCl). A. oryzae was cultured in DPY broth (20 g L−1 dextrin, 10 g L−1 polypeptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 2.31 g L−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g L−1 MgSO4), and Trichoderma in PDB broth (200 g L−1 potato, 20 g L−1 glucose).

Genome sequencing of T. atroviride B7

Genomic DNA was extracted from T. atroviride B7 mycelia using a Fungi Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Sangon Biotech) and sequenced via Illumina technology, yielding 17 contigs.

Comparative transcriptomic sequencing of T. atroviride B7

T. atroviride B7 was inoculated into 100 mL TB3 broth (200 g L−1 sucrose, 6 g L−1 yeast extract, 6 g L−1 tryptone) or CD broth (200 g L−1 sucrose, 3 g L−1 NaNO3, 1 g L−1 K2HPO4, 0.5 g L−1 MgSO4, 0.5 g L−1 KCl, 0.01 g L−1 FeSO4) and cultured at 30 °C, 180 rpm for 4 days. Mycelia were harvested for RNA extraction (Fungal RNA Kit, Omega Biotek) and transcriptome sequencing (Illumina). Parallel mycelial samples were extracted with EtOAc and then subjected to GC–MS analysis.

Enzymatic activity-guided protein fractionation and proteomics analyses

Freshly grown hyphae of T. atroviride B7 were inoculated into 100 mL PDB medium and cultured at 30 °C with shaking at 180 rpm for 48 h. The culture was then scaled up to 3 L PDB medium and incubated under the same conditions for an additional 6 days. Mycelia were harvested using a cell strainer and washed with distilled water. A total of 53.8 g of mycelia were obtained, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder. The powdered mycelia were suspended in protein extraction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) and stirred gently on ice for 30 min using a glass rod. After centrifugation at 13,523 g (4 °C for 10 min), the supernatant was subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation (ASP) by sequentially adding (NH4)2SO4 to achieve 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% saturation, with each step incubated on ice until complete precipitation occurred. Each fraction was centrifuged at 13,523g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were transferred for subsequent precipitation steps, while the pellets were resuspended in protein extraction buffer for enzyme assays. The ASP procedure was repeated twice with optimized gradients to remove inactive proteins. Active fractions were further purified by ion-exchange chromatography (HiTrap Capto Q, 1 mL, Cytiva Sweden AB) using a linear gradient elution of 0-100% buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.5) in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) at a 1 mL/min flow rate (15 mL per gradient). Three fractions showing high enzymatic activity were collected as positive samples, along with one neighboring, weakly active fraction used as a negative control.

Enzyme assays were performed in 200 μL reaction volumes containing 100 μL reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 50 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5), 10 μg GGPP, and 100 μg protein. Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 1 h, then extracted twice with 400 μL hexane. The combined organic phase was evaporated under nitrogen gas and the residue was resuspended in 50 μL hexane for GC–MS analysis.

For proteomic analysis, protein samples were determined using a NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). In total, 40 μg of each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE, and the entire gel lanes were excised for processing. Gel slices were destained, alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested with trypsin. The resulting peptides were extracted, desalted, and subject to LC–MS/MS analysis using an EASY-nLC 1000 system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) with Proteome Discoverer 2.4 software.

Heterologous expression in E. coli

The crtE gene encoding GGPPS from Erwinia was cloned into pCDF-Duet1 to create pCDF-Duet1-crtE, which was co-transformed with pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS into E. coli BL21 to generate a strain producing FPP and GGPP precursors. Similarly, TriTPS4 from T. atroviride B7 was cloned into pET-28a and co-transformed with pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS to create an alternative GGPP-producing strain. Candidate genes were PCR-amplified from T. atroviride B7 cDNA and cloned into pET-28a in XhoI/SalI restriction sites using a seamless cloning kit (BBI). tri4155 and homologs were cloned into pCold-TF (SalI/KpnI sites), generating pCold-TF-tri4155 and other pCold-TF-triDTCs. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using pCold-TF-tri4155 as template with overlapping primers (with 15 bp overlaps), followed by DpnI digestion and transformation into E. coli DH5α. Verified plasmids were isolated from 6 mL overnight cultures.

Positive E. coli strains were grown in LB medium (6 mL) supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (100 mg L−1 ampicillin or 50 mg L−1 streptomycin, plus 50 mg L−1 chloramphenicol and 50 mg L−1 kanamycin) at 37 °C, 180 rpm overnight. 1 mL culture was inoculated into 100 mL TB broth with antibiotics and grown to OD600 value of 0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.3 mM IPTG, followed by incubation at 16 °C for 18 h and then at 30 °C for 72 h. Cultures were extracted with 150 mL ethyl acetate assisted by ultrasonication for 20 min. Organic phases were concentrated by rotary evaporation, dried under nitrogen gas, and resuspended in 800 μL hexane for GC–MS analysis. Every experiment has three biological replicates.

Heterologous expression in A. oryzae NSAR1

The tri4155 cDNA was cloned into pTAex3 (NdeI/SmaI sites) under the PamyB promoter. For C-terminal His-tagging fusion, tri4155 or homologous gene was amplified with His-tag-encoding primers and fused with 700 bp upstream (Ptri4155) and 500 bp downstream (Ttri4155) sequences by overlap extension PCR, which was then ligated into pTAex3 to create pTAex3-Ptri4155-triDTC-His-Ttri4155.

Protoplast preparation was performed following established methods44 with modifications. One-day-old A. oryzae NSAR1 mycelia were digested in 10 mL Yatalase solution (0.1 g Yatalase, 0.79 g (NH4)2SO4 in 50 mM maleic acid, pH 5.5) at 30 °C, 100 rpm for 1–3 h. Protoplasts were filtered, centrifuged (1258g, 10 min), washed, and resuspended in a stabilizing buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 50 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) to a final density of 1–5 × 107 mL−1. For transformation, 200 μL protoplasts were gently mixed with 10 μg of plasmid DNA and incubated on ice for 30 min. Subsequently, 1.35 mL PEG solution (150 mM PEG4000, 50 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. After adding 5 mL stabilizing buffer and centrifugation, protoplasts were resuspended in 10 mL top agar (M medium with 0.15% methionine, 0.01% adenine, 0.8% agar) and plated on selection plates (1.0% agar). Transformants were verified by PCR and cultured in DPY broth for 7 days before extraction and GC–MS analysis. Every experiment contains three biological replicates.

Gene knockout in Trichoderma fungi

A split-marker strategy was applied with HygR cassette fragments splitting into 969 bp and 1,336 bp with 174 bp overlapping; the split fragments were flanked by 1 kb up- and down-stream target gene homology arms, respectively. Protoplasts were prepared following the protocol described for A. oryzae, and transformations were conducted as previously described45 with modifications. Briefly, 6 μg each of upstream and downstream deletion fragments were mixed with 200 μL protoplasts and 50 μL PEG buffer (25% PEG6000, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5), followed by incubation on ice for 30 min. Subsequently, 2 mL PEG buffer was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. After the addition of 5 mL stabilizing buffer, the cells were centrifuged and plated in top agar (M medium containing 100 mg/L hygromycin B and 0.8% agar), then spread onto selection plates (1.0% agar). Positive transformants were verified by PCR using primers flanking the deletion region (Supplementary Data File 4) and then cultured in PDB for 4 days before metabolite analysis.

In vitro enzyme assays

The Tcie612 gene was cloned into pCold-II (SalI/KpnI) with a C-terminal His-tag. Site-specific mutagenesis was performed as described above. E. coli Rosetta strains transformed with the constructs were grown overnight in LB medium (6 mL) supplemented with 100 mg L−1 ampicillin and 50 mg L−1 chloramphenicol at 37 °C, 180 rpm. 1 mL culture was inoculated into 100 mL LB broth containing the same antibiotics. After growing to OD600 0.6–0.8, the cultures were induced with 0.3 mM IPTG at 16 °C for 18 h. Cells were harvested and lysed by sonication in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and the cleared lysate was incubated with Ni-NTA resin in a binding buffer containing 20 mM imidazole at 4 °C for 1 h. After washing with buffer containing 20 mM and 40 mM imidazole, the target proteins were eluted with 300 mM imidazole and concentrated to 500 μL using 10 kDa centrifugal filters.

Standard enzyme assays were performed in 200 μL volumes containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 25 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 5 mM hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. For kinetic measurements, 100 μL reaction mixtures were prepared with varying concentrations of GGPP (4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 30, 60, 80, and 200 μM). Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min and then stopped by flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. The reaction mixtures were extracted with hexane and then analyzed by GC–MS. Each experiment contains three biological replicates. Kinetic parameters were determined using nonlinear regression based on the Michaelis-Menten equation (Origin 2021) from triplicate experiments.

ITC experiments

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was performed using a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC instrument to determine the number of Mg2+ binding per enzyme. The Tcie612 enzyme was prepared at a concentration of 20 μM in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Before titration, the enzyme was either pre-incubated with or without two equivalents of GGPP (40 μM). Subsequently, 280 μL of the protein solution was loaded into the sample cell, and 60 μL of MgCl2 solution (1.2 mM) was loaded into the injector. The titration was carried out under the following conditions: stir speed 750 rpm, cell temperature 25 °C, first injection of 0.4 μL over 3.0 s, and then 2 μL over 3.0 s for the rest 18 injections, with an interval of 150 s between each injection. The data were analyzed using MicroCal PEAQ-ITC analysis software (Malvern Panalytical). The “Two Sets of Sites” binding model was applied for curve fitting.

Compound quantification

Compounds 1 and 2 were dissolved in hexane and diluted to concentrations of 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, and 2.00 mg/mL using a double dilution method for GC‒MS analysis. The analytical parameters were the same as those described above. Standard curves correlating concentrations to peak areas were obtained using Origin 2021. The calibration equation of 1 (EIC: m/z 244) was: y = 5972018x (R2 = 0.985), while the equation of 2 (EIC: m/z 272) was: y = 17872250x (R2 = 0.973). The standard curves were used to quantify compounds 1 and 2 in the in vivo and in vitro experiments. The production bar charts were generated using GraphPad Prism 10.8.1. Each experiment was performed with at least three replicates.

Phylogeny analysis

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT v7.520 (auto strategy). Neighbor-joining trees were constructed using MEGA 7.

In silico experiments

Protein structures were predicted using AlphaFold2.3.2 (https://wemol.wecomput.com/). Binding pockets were analyzed using CB-dock2 (https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2). The substrate (GGPP) and intermediates (c, e) were energy-minimized and docked using AutoDock-GPU (WeMol server).

Biological function experiments

Test compounds were dissolved in DMSO and incorporated into PDA plates, while plates containing DMSO alone served as negative controls. Hyphae were center-inoculated and cultured at 25 °C under 12 h light/dark cycles. Plates were photographed, and hyphae were examined microscopically (Evos XL Core). For liquid cultures, hyphae were inoculated into PDB and grown at 30 °C, 180 rpm for 3 days. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text, Supplementary Information, Supplementary Data files, Source data, and public repositories. Protein sequences for constructing the phylogeny tree were retrieved from the UniProt database or NCBI GenBank; the accession numbers were listed in Supplementary Data File 2. Plasmids and strains were listed in Supplementary Data File 5, which are available on request. Sequences of this study were listed in Supplementary Data File 6. The Whole Genome Shotgun project of T. atroviride B7 has been deposited at GenBank under accession code JBPAFJ000000000. Raw comparative transcriptome sequencing data have been deposited at NCBI SRA under accession code PRJNA1235459. The tri4155 gene cluster sequence has been deposited at NCBI SRA under accession code PRJNA1234899. Proteomics data have been deposited at iProX under accession code IPX0011342000. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Christianson, D. W. Structural and chemical biology of terpenoid cyclases. Chem. Rev. 117, 11570–11648 (2017).

Ducker, C. et al. A diterpene synthase from the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis produces the pheromone sobralene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2322453121 (2024).

Palframan, M. J., Bandi, K. K., Hamilton, J. G. C. & Pattenden, G. Sobralene, a new sex-aggregation pheromone and likely shunt metabolite of the taxadiene synthase cascade, produced by a member of the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis species complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 59, 1921–1923 (2018).

Avalos, M. et al. Biosynthesis, evolution and ecology of microbial terpenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 39, 249–272 (2022).

Luo, S. H. et al. Glandular trichomes of Leucosceptrum canum harbor defensive sesterterpenoids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4471–4475 (2010).

Sato, T. et al. Sesquarterpenes (C35 Terpenes) biosynthesized via the cyclization of a linear C35 isoprenoid by a tetraprenyl-β-curcumene synthase and a tetraprenyl-β-curcumene cyclase: identification of a new terpene cyclase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9734–9737 (2011).

Schor, R. et al. Three previously unrecognised classes of biosynthetic enzymes revealed during the production of xenovulene A. Nat. Commun. 9, 1963 (2018).

Rudolf, J. D. & Chang, C. Y. Terpene synthases in disguise: enzymology, structure, and opportunities of non-canonical terpene synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 37, 425–463 (2020).

Derengowski, L. S. et al. Antimicrobial effect of farnesol, a Candida albicans quorum sensing molecule, on Paracoccidioides brasiliensis growth and morphogenesis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 8, 13 (2009).

do Nascimento, J. S. et al. Natural trypanocidal product produced by endophytic fungi through co-culturing. Folia Microbiol. 65, 323–328 (2020).

Arai, M., Niikawa, H. & Kobayashi, M. Marine-derived fungal sesterterpenes, ophiobolins, inhibit biofilm formation of Mycobacterium species. J. Nat. Med. 67, 271–275 (2013).

Duke, S. O. & Dayan, F. E. Modes of action of microbially-produced phytotoxins. Toxins 3, 1038–1064 (2011).

Chaverri, P., Castlebury, L. A., Overton, B. E. & Samuels, G. J. Hypocrea/Trichoderma: species with conidiophore elongations and green conidia. Mycologia 95, 1100–1140 (2003).

Woo, S. L., Hermosa, R., Lorito, M. & Monte, E. Trichoderma: a multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 312–326 (2023).

Lorito, M., Woo, S. L., Harman, G. E. & Monte, E. in Annual Review of Phytopathology Vol. 48 (eds N. K. VanAlfen, G. Bruening & J. E. Leach) pp 395–417 (2010).

Yuan, M. et al. Whole RNA-sequencing and gene expression analysis of Trichoderma harzianum Tr-92 under chlamydospore-producing condition. Genes Genomics 41, 689–699 (2019).

Zhu, X. C., Wang, Y. P., Wang, X. B. & Wang, W. Exogenous regulators enhance the yield and stress resistance of chlamydospores of the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum T4. J. Fungi 8, 1017 (2022).

Bai, B. et al. Trichoderma species from plant and soil: an excellent resource for biosynthesis of terpenoids with versatile bioactivities. J. Adv. Res. 49, 81–102 (2023).

Yamamoto, T. et al. Wickerols A and B: novel anti-influenza virus diterpenes produced by Trichoderma atroviride FKI-3849. Tetrahedron 68, 9267–9271 (2012).

Barra, L. & Dickschat, J. S. Harzianone biosynthesis by the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma. Chembiochem 18, 2358–2365 (2017).

Ghisalberti, E. L., Hockless, D. C. R., Rowland, C. & White, A. H. Harziandione, a new class of diterpene from Trichoderma harzianum. J. Nat. Prod. 55, 1690–1694 (1992).

Cardoza, R. E. et al. Identification of loci and functional characterization of trichothecene biosynthesis genes in filamentous fungi of the genus Trichoderma. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4867–4877 (2011).

Murai, K. et al. An unusual skeletal rearrangement in the biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene trichobrasilenol from Trichoderma. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 15046–15050 (2019).

Yan, Y. et al. Biosynthesis of the fungal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibitor heptelidic acid and mechanism of self-resistance. Chem. Sci. 11, 9554–9562 (2020).

Li, W. Y. et al. Antibacterial harziane diterpenoids from a fungal symbiont Trichoderma atroviride isolated from Colquhounia coccinea var. mollis. Phytochemistry 170, 112198 (2020).

Misawa, N. et al. Canthaxanthin biosynthesis by the conversion of methylene to keto groups in a single-gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 209, 867–876 (1995).

Miao, F. P. et al. Absolute configurations of unique harziane diterpenes from Trichoderma Species. Org. Lett. 14, 3815–3817 (2012).

Landmann, C. et al. Cloning and functional characterization of three terpene synthases from lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 465, 417–429 (2007).

Frick, S. et al. Metal ions control product specificity of isoprenyl diphosphate synthases in the insect terpenoid pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4194–4199 (2013).

Paysan-Lafosse, T. et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D418–D427 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Biosynthesis of phomactin platelet activating factor antagonist requires a two-enzyme cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312996 (2023).

Koeksal, M. et al. Taxadiene synthase structure and evolution of modular architecture in terpene biosynthesis. Nature 469, 116–120 (2011).

Schrepfer, P. et al. Identification of amino acid networks governing catalysis in the closed complex of class I terpene synthases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E958–E967 (2016).

Monte, E. The sophisticated evolution of Trichoderma to control insect pests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2301971120 (2023).

Geiser, D. M., Timberlake, W. E. & Arnold, M. L. Loss of meiosis in Aspergillus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13, 809–817 (1996).

Willetts, H. J. & Bullock, S. Developmental biology of sclerotia. Mycol. Res. 96, 801–816 (1992).

Calvo, A. M., Gardner, H. W. & Keller, N. P. Genetic connection between fatty acid metabolism and sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25766–25774 (2001).

Wolf, J. C. & Mirocha, C. J. Regulation of sexual reproduction in gibberella-zeae (Fusariumroseum graminearum) by F-2 (zearalenone). Can. J. Microbiol. 19, 725–734 (1973).

Schimmel, T. G., Coffman, A. D. & Parsons, S. J. Effect of butyrolactone I on the producing fungus, Aspergillus terreus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3707–3712 (1998).

Roncal, T. et al. Novel diterpenes with potent conidiation inducing activity. Tetrahedron Lett. 43, 6799–6802 (2002).

Liu, K. et al. Regulation of cellulase expression, sporulation, and morphogenesis by velvet family proteins in Trichoderma reesei. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 769–779 (2016).

Kim, D. M., Sakamoto, I. & Arioka, M. Class VI G protein‑coupled receptors in Aspergillus oryzae regulate sclerotia formation through GTPase‑activating activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 108, 141 (2024).

Brown, N. A., Schrevens, S., Dijck, P. & Goldman, G. H. Fungal G-protein-coupled receptors: mediators of pathogenesis and targets for disease control. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 402–414 (2018).

Punt, P. J. & Vandenhondel, C. Transformation of filamentous fungi based on hygromycin-B and phleomycin resistance markers. Methods Enzymol. 216, 447–457 (1992).

Gruber, F., Visser, J., Kubicek, C. P. & Degraaff, L. H. The development of a heterologous transformation system for the cellulolytic fungus Trichoderma reesei based on a pyrg-negative mutant strain. Curr. Genet. 18, 71–76 (1990).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Tao Liu (Tianjin Institute of Industrial Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for providing plasmid pBbA5c-MevT-MBIS. We sincerely thank Prof. Katsuya Gomi (Tohoku University) and Profs. Katsuhiko Kitamoto and Jun-ichi Maruyama (The University of Tokyo) for generously providing the A. oryzae NSAR1 strain and expression vectors. We appreciate Prof. Ze-Fen Yu (Yunnan University) for her expert guidance on the physiological architecture of fungi. We appreciate Prof. Shi-Hong Luo (Shenyang Agricultural University) for providing the Fusarium graminearum strain. This research was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82222072, 22107103 and U23A20510), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB1230000), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M703285), the Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan (No. 202401BC070016), and the Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program Young Talent Project (XDYC―QNRC―2024―560).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sheng-Hong Li and Yan Liu conceived and supervised the project. Jonathan Gershenzon provided valuable scientific guidance. Xuemei Niu identified the Trichoderma strains. Min-Jie Yang designed and performed the majority of experiments. De-Sen Li constructed the E. coli strains. Hua-Qin Deng conducted fermentation experiments. Wen-Yuan Li sequenced the T. atroviride B7 genome. Xin-Yu Zheng performed gene cloning. All authors participated in writing and revising the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, MJ., Li, DS., Deng, HQ. et al. Noncanonical terpene cyclases for the biosynthesis of diterpenoids regulating chlamydospore formation in plant-associated Trichoderma. Nat Commun 16, 7823 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63055-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63055-4