Abstract

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) profoundly impacts global climate, but its sea surface temperature (SST) variability projected by climate models remains uncertain, with a substantial inter-model spread in 21st-century projections. Model-observation discrepancies in ENSO physics contribute to this uncertainty, necessitating observational constraints to refine projections. However, methods to achieve this constraint remain unclear. Here, we show that deep learning informed by the observed response of ENSO SST variability to tropical Pacific warming patterns reduces projection uncertainty by 54% under a high-emission scenario. Specifically, artificial neural networks (ANNs), trained on climate model simulations and observations, successfully capture the real-world ENSO response. Interpretability analyses reveal that replicating observed ENSO physics by ANNs is critical, identifying warming in the far-eastern and central equatorial Pacific as key to ENSO change. A model-as-truth approach further confirms the robustness of ANN-generated projections. By conditioning future ENSO SST variability projection on the ANN-inferred ENSO response to tropical Pacific warming, uncertainty is reduced from a range of 0.59 °C to 0.27 °C. Our results highlight the prospect of integrating machine learning with observations to reduce uncertainty in climate projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ENSO is the most prominent mode of interannual climate variability stemming from air-sea interactions in the tropical Pacific1,2. Characterized by a phase transition between the warm El Niño and the cold La Niña events, ENSO substantially influences climate extremes, ecosystems, agriculture, and economic development worldwide through atmospheric teleconnections3,4,5. Given the profound societal impacts of ENSO, understanding changes in ENSO characteristics under anthropogenic climate change is a pivotal aspect of climate risk management strategies6,7,8.

The prevailing understanding of ENSO changes under anthropogenic warming relies heavily on future scenario simulations from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) models6,9. These simulations generally agree on an intensification of ENSO SST variability from the 20th to the 21st century10,11. Nevertheless, considerable uncertainties remain in both historical simulations and future projections of ENSO SST variability (Supplementary Fig. 1a). From a historical perspective, CMIP models have struggled to reproduce the real-world properties of ENSO SST variability12,13,14. Specifically, in the latter half of the 20th century, the tropical Pacific experienced increased ENSO SST variability with a La Niña-like SST trend, whereas models simulate the variability increase but with an El Niño-like trend14,15,16. Tropical Pacific warming patterns are key in regulating ENSO feedbacks17,18. The discrepancy between observations and simulations questions the reliability of projected ENSO responses to tropical warming.

From a future perspective, there is still a notable lack of inter-model consensus on the future evolution of ENSO SST variability7,9,19,20. Studies suggest that the collapse of oceanic upwelling and intensified atmospheric convection in the eastern equatorial Pacific after 2100 will lead to an eventual reduction in ENSO SST variability after 2100 under continued warming21,22. However, the timing and magnitude of this reduction vary considerably between CMIP models (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Thus, despite extensive efforts, there are still considerable uncertainties in state-of-the-art climate models that need to be addressed to improve the robustness of ENSO SST projections.

Many factors contribute to the uncertainties in projections of ENSO. Among these, the insufficient fidelity of CMIP models in reproducing observed ENSO physics is a critical factor that undermines confidence in the reliability of their future projections19,20. For instance, in some CMIP models, feedback processes that control the evolution of ENSO exhibit substantial discrepancies when compared with reanalysis data (Supplementary Fig. 2), implying that their dynamics through which tropical Pacific warming influences ENSO are, to a large extent, not reflective of the actual processes occurring in nature. As a result, the reliability of ENSO projections from these models is called into question.

To reduce uncertainties in ENSO SST projections, rigorous model evaluation and observational constraints are essential23,24. However, current statistical approaches face limitations because ENSO is modulated by numerous feedback processes, whose relative importance changes under global warming21,22,25. This dynamic shift complicates the identification of key performance metrics and climate-invariant relationships required by current traditional23,24,26 or machine learning methods27,28. Thus, how to condition ENSO projections on real-world information remains a challenge. To address this, we propose an approach that integrates deep learning with observational data and climate model simulations. By conditioning projections on the observed response of ENSO SST variability to tropical Pacific warming patterns via ANNs, we achieve a 54% reduction in uncertainty for future ENSO SST variability under a high-emission scenario.

Results

ANNs capture ENSO response to warming

To realistically project future ENSO SST variability, a statistical mapping model is needed that can reproduce observed historical ENSO manifestations and project its future trajectory when given relevant input predictors. Extensive research has established that changes in the tropical Pacific mean state drive low-frequency modulation of ENSO6,8,17,18. Consequently, our mapping model anchors on the tropical Pacific mean state as the input predictor, with the output being the standard deviation of SST anomalies in the Niño3.4 region (see Definition of ENSO SST amplitude and SST mean state in Methods). Using this model, we can input projected patterns of mean state changes under greenhouse warming to extrapolate the future evolution of ENSO SST variability. The nonlinear nature of ENSO precludes the determination of an analytical form for the statistical model. Furthermore, given the critical role of the spatial structure of tropical Pacific warming patterns, we employ a convolutional neural network (CNN). CNNs, a type of ANN architecture primarily utilized for processing spatial patterns in images, have proven effective at capturing complex spatial relationships inherent in climate data29.

ANNs have the potential to approximate the complex interactions between ENSO SST variability and changes in the tropical Pacific mean state. To ensure accurate projections, it is critical that ANNs capture the underlying ENSO physics. Climate models often fail to reproduce observed ENSO dynamics with sufficient fidelity (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, a strategic approach is to minimize reliance on CMIP data and instead develop ANNs that are grounded in observational data, ensuring that they reflect real-world relationships. Directly training ANNs with observational data, however, presents challenges due to limitations in both the quantity and reliability of available observational datasets (Supplementary Fig. 1d–f). A common solution is to use transfer learning, a technique where ANNs are pre-trained on CMIP model outputs and then fine-tuned with observational data29,30,31. Following the principles of transfer learning, we first train ANNs on CMIP model outputs and then evaluate their performance using historical observations.

We pre-train 11 ANNs using piControl, historical and future scenario simulations from 11 CMIP6 models (see Observational and CMIP data in Methods). Each ANN captures the nonlinear relationship between the ENSO SST amplitude and the tropical Pacific mean state in its respective climate model (Supplementary Fig. 3; see Framework and training of ANNs in Methods). SST alone may be questionable as a sole representative of the mean state inputs to ANNs, since changes in the tropical Pacific mean state are not only manifested in SST, but also in other variables such as the thermocline in the subsurface ocean. Physically, oceanic and atmospheric variables are closely coupled during ENSO evolution, with changes in one variable often correlated with changes in another25,32. This interdependence suggests that additional inputs may be redundant (Supplementary Table 3). Indeed, the ANNs perform well on their respective validation datasets (blue bars in Fig. 1a; see Supplementary Fig. 5 for each ANN), demonstrating that the CMIP-modeled relationship between ENSO SST amplitude and tropical Pacific mean state can be effectively captured using SST alone as the input.

a Performance of artificial neural networks (ANNs) on Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) and observational data. The x-axis indicates the ANN pre-trained on simulations from the corresponding CMIP model. The ENSO SST amplitude is defined as the 30-year running standard deviation of the linearly detrended SST anomalies over the Niño3.4 region (5°S-5°N and 170°W-120°W). Blue bars show correlations between ANN-estimated (using the CMIP data as input) and CMIP-modeled ENSO SST amplitudes. Red bars show correlations between ANN-estimated (using three observational datasets as input) and observed ENSO SST amplitudes. All ANNs reproduce the modeled response to tropical Pacific warming patterns (blue bars > 0.75, dashed line), but their performance varies when applied to observations. b The ANN trained on GISS-E2-1-H simulations (ANNGISS-E2-1-H) shows the strongest correlation (r = 0.71) with observed ENSO SST amplitudes. ANN-estimated and observed ENSO SST amplitudes are normalized to zero mean and unit variance. Thus, certain ANNs can capture the observed responses of ENSO SST amplitude to tropical Pacific warming patterns.

Eleven ANNs, trained on CMIP simulations, approximate the modeled relationship between ENSO SST amplitude and tropical Pacific SST mean state. The next step is to evaluate which ANNs accurately reproduce observed ENSO SST amplitudes when provided with the observed SST mean state (Supplementary Fig. 6). Among these, the ANNGISS-E2-1-H shows the highest correlation with observational data (Fig. 1; see Supplementary Table 5 for specific values), indicating that it effectively captures the observed ENSO response to mean state changes. However, some ANNs perform poorly, raising concerns about their use in future projections. For this reason, the traditional approach29,33,34 of integrating all climate model data to train a single ANN is not employed in this study. ANNs trained in this manner tend to reflect the characteristics of the multi-model mean. It is evident that certain climate models exhibit implausible ENSO dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 2), thereby suggesting that the multi-model mean is susceptible to systematic biases. Consequently, the ANN demonstrates unsatisfactory performance when applied to historical observational data (Supplementary Fig. 7), undermining its utility for future ENSO projections.

A key question is why some ANNs outperform others. Given their black-box nature, ANNs are often subject to skepticism due to the difficulty in interpreting their outcomes35. Therefore, interpretability analyses are performed to open the black-box of ANNs from a physical perspective.

Obeying ENSO physics ensures ANN fidelity

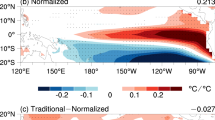

To understand why certain ANNs perform well on observational data, we adopt a dual-perspective framework. From an interpretable machine learning perspective, we apply occlusion sensitivity analysis to identify tropical Pacific subregions where mean SST greatly influences ENSO SST amplitude estimation (see Occlusion sensitivity in Methods). We find that well-performing ANNs are highly sensitive to the SST mean state in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific (Fig. 2a, b; see Supplementary Fig. 8 for the occlusion sensitivity in each ANN). This is consistent with well-established physical mechanisms governing ENSO SST amplitude. Central SST warming enhances wind-ocean coupling through increased upper-ocean stratification and elevated equatorial thermocline, thereby amplifying ENSO SST variability10,36,37. Eastern SST warming influences ENSO by facilitating more frequent atmospheric convection, strengthening zonal winds, decreasing the zonal temperature gradient, and deepening the thermocline38,39,40,41.

a, b Critical regions for estimating El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) sea surface temperature (SST) amplitude, identified via occlusion sensitivity (shading). The six best-performing ANNs (BEST6) consistently highlight the central and eastern equatorial Pacific (boxes, 5°S-5°N, 160°E-140°W and 120°W-95°W), while the remaining five ANNs (REM5) fail to identify coherent critical regions. c Under a high-emission scenario, critical regions shift eastward as the tropical Pacific warms. Averaged occlusion sensitivity in the eastern box increases with greenhouse warming, indicating a growing influence of eastern Pacific warming on future ENSO SST variability. d, e Observed and simulated SST trends in the two critical regions. Observed SST trends are from three observational datasets, and simulated SST trends are from 11 Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) models. Although the observed (La Niña-like) and modeled (El Niño-like) warming patterns appear to be opposite, the differential warming rate between the two critical regions is similar, shown by the faster warming in the east and a weakening zonal SST gradient. These two critical regions are physically recognized as the regions where multiple feedbacks controlling ENSO SST variability occur. The ANN sensitivity to these areas aligns with established ENSO physics.

Based on these previous studies, eastern Pacific SST warming is suggested to modulate changes in ENSO SST variability both independently and via the formation of a zonal SST gradient with central Pacific SST warming. Consequently, a linear combination of eastern and central Pacific SST warming may exhibit a statistical correlation with ENSO feedbacks. Critically, the thermocline-wind coupling coefficient, a key parameter governing thermocline feedback strength, shows statistically significant correlation with this linear combination of eastern and central Pacific SST warming (Supplementary Fig. 9). This strong linear correlation shows that the key regions identified through occlusion sensitivity analysis are physically linked to established ENSO feedback mechanisms. Besides, under the high-emission scenario, persistent eastern warming reduces the non-convective area, further dampening post-2100 ENSO SST variability through weakened thermocline feedback and enhanced thermodynamic damping21,22. Consistent with the occlusion sensitivity results (Fig. 2c and see Supplementary Fig. 10 for spatial patterns in each period), maximum sensitivity shifts eastward as the tropical Pacific warms. While central SST changes influence ENSO throughout the 21st century, eastern warming becomes dominant during the rapid decline of ENSO SST variability post-2100.

The results of the occlusion sensitivity are evident in the observational data. Previous studies typically divide the tropical Pacific at the date line, with the central equatorial Pacific, where cooling is observed (Fig. 2d), being part of the eastern region16,20,22,42. The observed La Niña-like warming pattern and increased zonal SST gradient are mainly due to faster SST warming west of the date line (e.g., 120°E-180°) than in the rest of the eastern region (e.g., 180°-80°W). However, occlusion sensitivity analyses show that the central equatorial Pacific should be part of the western region in terms of its influence on ENSO SST amplitude. Despite substantial warming, SST changes west of 160°E have a negligible effect on ENSO SST amplitude. Both models and observations show more rapid warming in the far-eastern region (Fig. 2e), reducing the zonal SST gradient in the second half of the last century. Thus, there is an agreement between the simulated and observed warming patterns in terms of the effect on the ENSO SST amplitude, which further explains why ANNs trained on model data can capture the observed ENSO SST amplitude responses to tropical Pacific warming patterns.

Occlusion sensitivity, while offering intuitive visual insights, faces key limitations43: sensitivity to occlusion parameters (size, shape, placement), high computational cost, potential for artifact generation, and a focus on local explanations that fails to capture distributed feature representations in complex models. Critically, its reliance on the independence assumption between occluded regions and its univariate methodology hinders its ability to elucidate complex nonlinear feature interactions, limiting comprehensive model insight. Given these limitations, we continue our interpretability analysis from an ENSO dynamics perspective.

From an ENSO dynamics perspective, we expect that well-performing ANNs are likely to be trained on datasets from climate models with more realistic ENSO dynamics. This is supported by the fact that models with lower biases in the BJ index tend to produce ANNs with better performance on observational data, as indicated by a correlation coefficient of − 0.83 (Fig. 3a, b). In addition, ENSO diversity and nonlinearity affect low-frequency changes in ENSO SST variability14,44,45,46. To make reliable projections of ENSO SST variability, climate models must capture realistic ENSO diversity and nonlinearity10,47. Thus, well-performing ANNs are likely to be trained on climate model datasets with more realistic ENSO diversity and nonlinearity (see Supplementary Fig. 11 for the nonlinear relationship in each climate model). Indeed, the better alignment with observed ENSO nonlinearity is associated with an improved ANN performance on observational data, as indicated by a correlation coefficient of − 0.76 (Fig. 3c, d; see also Supplementary Fig. 12 for an alternative definition of ENSO nonlinearity).

a, b Relationship between ANN performance and bias in the Bjerknes stability (BJ) index. DD (dynamic damping), TD (thermodynamic damping), ZA (zonal advective feedback), MA (meridional advective feedback), VA (vertical advective feedback), and TH (thermocline feedback) represent the six components of the BJ index. Compared to ACCESS-ESM1-5, the GISS-E2-1-H model, whose ANN achieves the highest performance on observational data, exhibits BJ index components closer to those of the SODA reanalysis. BJ bias is quantified as the root mean square error of the six BJ index components between each climate model and SODA reanalysis. ANN performance is measured by the correlation coefficient between ANN outputs and observations. High ANN performance is associated with a low BJ bias. c, d Relationship between ANN performance and modeled ENSO nonlinearity. Nonlinearity is quantified using the leading coefficient α, obtained by fitting a quadratic curve to the first and second principal components (PC2(t) = α[PC1(t)]2 + β[PC1(t)] + γ), as determined by empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis of monthly SST anomalies in the tropical Pacific (1950–2014, 15°S-15°N and 140°E-80°W). Nonlinearity bias (NL bias) is defined as the absolute difference between the α estimated from each climate model and from three observational datasets. High ANN performance is associated with a close agreement with the observed nonlinearity. Together, these results confirm that ANNs achieve higher fidelity when trained on climate models that better replicate observed ENSO physics, including both linear stability and nonlinear dynamics.

It is acknowledged that if strong historical performance in certain climate models is attributable to chance, bias cancellation, or overfitting rather than physical robustness, such performance provides limited validity for future projections48,49. Thus, physical plausibility serves as the foundational principle for our methodological framework. ANNs demonstrating strong performance are capable of capturing the fundamental physics governing ENSO, rendering their projections inherently more reliable. Thus, a performance-weighted combination of these 11 ANNs is performed to create ANNobs, which takes the tropical Pacific SST mean state as input and outputs a weighted average of ENSO SST amplitudes from 11 ANNs. In this study, the weight is defined as the likelihood that the observational data come from the specified ANN, and it is positively correlated with the correlation coefficient shown in Fig. 1a (see Weighting scheme in Methods). It is important to acknowledge that performance-based weighting approaches inherently assume a linear relationship between historical skill and future reliability, potentially overlooking nonlinear climate transitions or feedback regime shifts. However, the training dataset employed in our study explicitly incorporates future simulations across a range of emission scenarios, spanning from SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5. The design ensures that potential ENSO feedback regime shifts and climate transitions are explicitly captured within the methodological framework.

While the physical plausibility of ANNs enhances the credibility of their future projections, rigorous out-of-sample testing remains fundamental for all climate projection constraint methodologies23,24. Given the absence of future climate observations for direct evaluation of ANNobs, we implement the model-as-truth framework (the established standard for assessing projection constraint techniques23,31,50,51,52) to evaluate ANN robustness under future scenarios.

Model-as-truth confirms ANN robustness

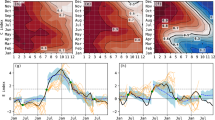

Climate model simulations are treated as observations sequentially (Fig. 4a; see Model-as-truth approach in Methods). The results demonstrate that by assigning greater weight to ANNs with superior performance on historical data, the ANN projections closely align with the direct simulations from climate models (Fig. 4b; see Supplementary Table 6 for specific values). Particularly for climate simulations with ENSO dynamics closely resembling observations, such as the BEST6 model ensemble, the discrepancy between ANN-based projections and direct model simulations is typically 0.03 ± 0.08 °C when evaluated within the model-as-truth framework (Supplementary Table 7). The findings, which are particularly encouraging when the ANN projection methodology is applied to the data from climate models, suggest that ANNobs effectively captures the response of ENSO SST amplitude to tropical Pacific warming patterns, demonstrating robustness in both the observed historical period and future warming scenarios.

a ANN-estimated (red line) and Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP)-modeled (black line) El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) sea surface temperature (SST) amplitudes when climate model data are treated as observations. Using the GISS-E2-1-H model as an example, its historical SST mean state is input into the ANNs as synthetic observational data. In the left panel, the ANN estimate shows a strong correlation with the GISS-E2-1-H historical simulations (HIS denotes the historical period; root-mean-square error = 0.05 °C, r = 0.91, p < 0.001). When the future SST mean state from the same model is fed into the ANNs, the estimate remains closely aligned with the model’s projected ENSO SST amplitudes (SSP126-585 denotes the future period across the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP)1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5 scenarios; root-mean-square error = 0.06, r = 0.90, p < 0.001). The right panel shows the probability density function (fitted to Gaussian distributions) of the bias in projected ENSO SST amplitudes. Thus, when treating GISS-E2-1-H climate model data as pseudo-observations, the uncertainty between ANN-based projections and direct model simulations measures 0.01 ± 0.05 °C across SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5 scenarios. b Correlation coefficients between ANN-estimated and CMIP-modeled ENSO SST amplitudes for historical (blue bars) and future (red bars) periods. The x-axis indicates the climate model simulation treated as synthetic observations. Excluding the climate model simulations subject to unrealistic ENSO physics (shading; these three models perform the worst against observational data and have the largest BJ index errors), ANNs that reproduce the historical response of ENSO SST amplitudes to mean state changes retain their skill under future scenarios. The dashed line represents the historical ANN performance on real observational data. The dependence of future ANN performance on historical skill in the model-as-truth approach suggests that ANNs validated against real-world observations are likely to be robust for real-world future projections.

Climate models from different institutions may share similar components, which could potentially reduce the effectiveness of the model-as-truth method24. Consequently, the reliability of the ANN projections is substantiated by multiple validations. We have demonstrated the feasibility of using ANNs to estimate the ENSO SST amplitude with the tropical Pacific SST mean state as input (Fig. 1). We also confirm the plausibility of ANNs in terms of ENSO physics (Figs. 2 and 3). Using the model-as-truth approach, we indirectly confirm the robustness of using ANNs to project future ENSO SST amplitude (Fig. 4). Next, we will make projections of future ENSO SST amplitudes conditional on ANNobs.

Reduced uncertainty with ANN projection

Unrealistic representation of ENSO physics is a major source of uncertainty in projections of ENSO SST amplitudes in the 21st century7,19. To reduce uncertainties, the projection of ENSO SST variability using potential tropical Pacific warming patterns must satisfy the observed ENSO feedbacks. The ANNobs can reproduce historical ENSO SST variability in a manner consistent with observed ENSO physics, and remain robust under future warming. Thus, to make the projections conditional on ANNobs, the future SST mean states from each climate model, after subtracting the climatological SST bias, are fed into ANNobs to generate projected ENSO SST amplitudes (see Uncertainty estimates of future projections in Methods), following the observational constraint framework27,49,53. Compared to the large spread in CMIP projections (1.20 ± 0.59°C, 95% confidence intervals; blue shading in Fig. 5a), ANN projections yield a narrower distribution (0.87 ± 0.27 °C; red shading) with a 54% reduction in uncertainty for the period 2024–2100.

a Projected ENSO SST amplitudes under the high-emission scenario. In the left panel, the blue shading represents the inter-model spread (the one standard deviation range) across 11 Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) models, with the thick blue line representing the multi-model mean. The red shading represents the spread across 11 outputs from ANNobs, which is the ultimate model that incorporates all ANNs and describes the real-world ENSO response to tropical Pacific warming patterns. The thick red line represents the ensemble mean. The black shading represents the range of three observational datasets. The right panel shows the probability density functions (fitted to Gaussian distributions) for projected ENSO SST amplitudes. b Comparison of ENSO SST amplitudes between ANNobs and CMIP models. BEST6 and REM5 represent the CMIP models with realistic and unrealistic ENSO physics, respectively. Amplitudes are normalized by their 1994–2023 values. ANNobs projects a reversal in ENSO SST amplitude trends around 2050 (dashed line; P1 and P2 denote periods of increasing and decreasing amplitudes, respectively), aligning with the BEST6 models. In contrast, the REM5 models project a much later reversal. c ANN-based dependence of ENSO SST amplitudes on the east-minus-west SST gradient and the SST mean state in the eastern equatorial Pacific (EP). The scatter plots represent the averaged projection over the 11 ANNobs outputs (corresponding to the black line in panel (b), but without normalization), and shading represents the fit of ANNobs outputs to a binary linear function. The gray dashed line marks the year 2050, showing that reversal occurs when the trajectory is tangent to the contour lines. Deep learning not only reduces uncertainty in ENSO projections through ANN-based constraints but also provides a straightforward insight into the non-unidirectional evolution of ENSO SST amplitudes in the 21st century.

In the context of observation-constrained approaches for climate projections, the reliability of observational data is paramount. Uncertainties in observations propagate into constrained results, imparting corresponding uncertainties to the projections. In this study, we incorporate observational uncertainty at the ANN training stage by ensuring the network reproduces the observed output ranges across different observational products. This integration is evidenced by the spread in the red shading prior to 2023 in Fig. 5a. Moreover, the increased reliability of satellite-derived SST data since 1980 reduces the uncertainty in ANN outputs. Thus, uncertainty in observational data is implicitly considered in our ANN-based projections.

Uncertainty in ANN-based projections has increased over time, a trend primarily attributable to uncertainty sources in ENSO projections. As outlined in the IPCC AR67, key sources encompass systematic model biases, stemming from inadequate representation of ENSO feedback processes, and spatial patterns of SST mean-state warming. While the present study employs ANNs to emulate observed feedback under real-world conditions (thereby mitigating uncertainty associated with the former source), it does not address uncertainties arising from projected SST warming patterns. Consequently, under low-emission scenarios, where inter-model differences in SST warming patterns are relatively small, ANN projections maintain a narrower uncertainty range over extended periods (Supplementary Fig. 13).

The ANN projections indicate that under the high-emission scenario, as the tropical Pacific continues to warm, the ENSO SST variability will eventually decrease, with the reversal occurring around 2050 (Fig. 5a). This behavior is not only evident in future projections but is also observed in the historical warming of the tropical Pacific45,54. For instance, around 1990, a discernible hiatus in the increase of ENSO SST variability is observed, subsequently followed by a weakening (Supplementary Fig. 1f). It is not surprising that ANNobs could project such a reversal. Climate models with more realistic ENSO feedbacks tend to produce the amplitude reversal within the 21st century, while climate models with less realistic ENSO feedbacks postpone the reversal (Fig. 5b; ref. 19). Given that ANNobs places greater reliance on climate models with realistic ENSO feedbacks in its construction, the time-varying ENSO SST amplitudes projected by ANN and these models exhibit notable similarity.

Theoretically, the emergence of the reversal is typically attributed to changes in ENSO feedbacks resulting from climatological changes in the zonal SST gradient under the greenhouse warming25. Model studies have suggested a relationship between changes in ENSO and changes in the zonal SST gradient, but this relationship is state and model dependent20,42,55. A decreased zonal SST gradient amplifies ENSO by increasing upper-ocean stratification and flattening the equatorial thermocline8,10,19, but attenuates ENSO by enhancing thermodynamic damping and weakening thermocline feedback21,22,56. While a comprehensive understanding of the reversal phenomenon in terms of the ENSO feedback balance is essential, achieving such an understanding is a complicated task. In contrast to the complex approach, the occlusion sensitivity indicates that the differential warming rate between the central and far-eastern equatorial Pacific is critical to estimating the ENSO SST amplitude (Fig. 2), thereby providing a straightforward insight into the emergence of the reversal. Building upon this, we analyze the dependence of ENSO SST amplitudes, as described by ANNobs, on the east-minus-west SST gradient and the SST mean state in the eastern equatorial Pacific to provide a concise explanation of the temporal evolution of ENSO SST amplitude.

We approximate the ANNobs using a binary linear function that depends on the east-minus-west SST gradient and the eastern equatorial Pacific SST (see Linear approximation of ANNobs in Methods). The findings show that a weaker zonal SST gradient and colder eastern equatorial Pacific SST tend to increase ENSO SST amplitudes (shading in Fig. 5c). This finding suggests the presence of two competing influences of mean SST in the eastern equatorial Pacific on ENSO SST amplitude. The direct effect of warming is to reduce ENSO SST variability by weakening the thermocline feedback and enhancing thermodynamic damping21,22, as seen post-2050 (P2 in Fig. 5b, c). Concurrently, warming can also reduce the zonal SST gradient, thereby increasing ENSO SST variability through mechanisms such as increased upper-ocean stratification, thermocline shoaling, and more frequent atmospheric convection8,10,14,39, as observed in the early 21st century (P1 in Fig. 5b, c). The changes in ENSO SST amplitudes depend on the trajectory in phase space, with reversals occurring at tangency to contour lines (dashed line in Fig. 5c). Furthermore, linear fitting indicates that ENSO SST amplitudes decrease when eastern warming is less than 1.15 times western warming (see Linear approximation of ANNobs in Methods). This value reflects a balance of ENSO feedback changes under the eastern equatorial Pacific warming, highlighting the importance of differential warming rates between the central and far-eastern equatorial Pacific in driving the changes in ENSO SST variability.

Discussion

Our exploration of future ENSO SST variability projections, conditioned on real-world observations of the ENSO response to tropical Pacific warming patterns, leverages deep learning. A flowchart illustrating the entire workflow is shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. The observed ENSO response is captured by ANNs pre-trained on CMIP simulations and validated against observational data. The plausibility of this approach is confirmed through interpretable machine learning and ENSO dynamics analysis, while its future robustness is verified via a model-as-truth framework. By conditioning future projections on the ANN-derived ENSO response to tropical Pacific warming patterns, we reduce uncertainty in ENSO SST variability projections by half under a high-emission scenario. The emerging integration of deep learning into climate science has garnered significant attention, but its full potential for climate trend projections remains nascent30,57. Our study, which synergizes deep learning with climate models, offers a promising way to reduce uncertainties in climate projections, with potential applications extending to other critical climate variables.

Methods

Observational and CMIP data

In this research, we utilize monthly mean SST simulations from 11 CMIP6 models, encompassing scenarios such as piControl, historical, Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP)1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 (Supplementary Table 1; ref. 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67). While CMIP6 includes over 60 climate models, only 11 satisfy the following two conditions: (1) A multi-realization requirement of at least two realizations per model to enable a training/validation split, and (2) Simulations extending beyond 2100 to capture end-of-century ENSO attenuation. Therefore, these eleven models are not arbitrarily selected, but rather constitute all available models meeting these criteria. Although some previous generations of climate models (CMIP5) provide simulations beyond 2100, CMIP6 models generally outperform CMIP5 models in terms of physical processes, resolution, and simulation of ENSO feedback mechanisms7,20. Therefore, this study exclusively uses CMIP6 models for analysis.

The piControl simulation extends over 300 years, while the historical simulation, encompassing 165 years, spans from 1850 to 2014. The SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP3-7.0 simulations cover an 86-year period from 2015 to 2100, and the SSP5-8.5 simulation extends over a 286-year period from 2015 to 2300 (2015 to 2299 for CESM2-WACCM, and 2015 to 2298 for NorESM2-MM), considering the reduced ENSO SST variability in the high-emission scenario beyond the 21st century21,22. For the training of neural networks, each CMIP6 model is required to provide at least two realizations: one for training and one for validation. With realizations numbered 1 to 3 available from each model, the second realization is designated for validation, and the others are employed for ANN training.

In order to establish the observed relationship between ENSO SST amplitude and the tropical Pacific mean state, reliance on observational products is essential. However, the reliability of these datasets poses a challenge, particularly for the pre-1950 period. Substantial discrepancies exist in SST trends across different products68, attributable to factors such as divergent interpolation methods69 and misrepresented ENSO variability70. In order to address these uncertainties, our analysis employs three observational products rather than relying on any single dataset, thereby providing an estimate of observational uncertainty: the Centennial In Situ Observation-Based Estimates of the Variability of SST and Marine Meteorological Variables version 2 (COBE2)71, the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature version 5 (ERSST)72, and the Hadley Center Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature dataset version 1.1 (HadISST)73. Notably, historical data for all three products is partially sourced from ICOADS (International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set). However, they employ different interpolation methods, which may lead to substantial discrepancies prior to 1950 (Supplementary Fig. 1d–f). Using reliable datasets like ICOADS directly, rather than observational products dependent on different interpolation schemes, is a promising approach. While the present study is not designed to do so, integrating an AI-based gap-filling module74,75 for climate data prior to the neural network projection model would be a promising direction.

These datasets, which offer global coverage with varying horizontal resolutions, are interpolated onto a 1° horizontal grid over the tropical Pacific Ocean (24.5°S-24.5°N and 120.5°E-75.5°W) using Delaunay triangulation with linear barycentric interpolation. This approach interpolates values within the convex hull of input data while assigning NaN to points requiring extrapolation. The procedure is implemented using either MATLAB’s griddata function or Python’s scipy.interpolate.griddata, yielding a final grid dimension of 50 by 165. To elucidate the underlying physics of the deep learning projection, we employ upper-ocean temperature and currents, zonal wind stress, and net heat flux into the ocean from CMIP6 simulations and the Simple Ocean Data Assimilation version 3.3.2 (SODA)76 to calculate the individual components of the Bjerknes stability index (BJ index).

Definition of ENSO SST amplitude and SST mean state

In alignment with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) and pertinent literature7,20,77, the ENSO SST amplitude is defined as the 30-year running standard deviation of the linearly detrended SST anomalies over the Niño3.4 region (5°S-5°N and 170°W-120°W). The contemporary SST mean state is defined as the 30-year time-averaged SST over the tropical Pacific Ocean. The labeled year corresponds to the midpoint of each 30-year interval. For instance, the SST mean state for 2009 is derived from the average of the monthly SST data spanning 1994–2023, and the contemporary ENSO SST amplitude corresponds to the standard deviation of the linearly detrended Niño3.4 SST anomalies over the same 30-year period. Consequently, the observed ENSO SST amplitude extends over a 125-year duration from 1885 to 2009.

Bjerknes stability index

The growth rate of ENSO SST anomalies is controlled by various feedback processes in the tropical Pacific. On the basis of a mixed-layer heat budget analysis, the equation of control can be written as follows25,78:

The terms on the right-hand side represent dynamic damping (DD), thermocline feedback (TH), zonal advective feedback (ZA), meridional advective feedback (MA), vertical advective feedback (VA), and thermodynamic damping (TD), respectively. T and Hm represent the mixed-layer temperature and depth (50 m). u and v represent the mixed-layer zonal and meridional velocities. w represents the vertical velocity at the base of the mixed layer. Overbars denote climatological means, and \(\left\langle .\right\rangle\) denote the average in the Niño3 region (5°S-5°N, 150°W-90°W). \({\mu }_{a}\) and \({\mu }_{a}^{*}\) represent the nonlocal (central equatorial Pacific; 5°S-5°N, 150°E-130°W) and local wind stress responses to SST anomalies in the Niño3 region. βh represents the response of zonal slope of thermocline to central equatorial wind stress anomalies, he – hw = βh[τx], where he and hw are anomalous thermocline depth averaged over the eastern (5°S-5°N, 155°W-80°W) and western (5°S-5°N, 120°E-155°W) equatorial Pacific, respectively, and [τx] denotes zonal wind stress anomalies averaged in the central equatorial Pacific. βur and βul (βvr and βvl, βwr and βwl) represent the response of u (v, w) in the Niño3 region to the anomalous wind stress in the central equatorial and Niño3 regions. ah is the subsurface temperature (at 75 m depth) response to the averaged thermocline depth anomalies over the eastern equatorial Pacific. α is the thermal damping of SST anomalies in the Niño3 region by air-sea heat fluxes. All feedback coefficients are estimated using linear regressions between predictors and the response variable. γ measures the effectiveness of vertical entrainment (assigned to be 0.75). Lx and Ly are the zonal and meridional scales of the eastern equatorial box, and y is the meridional distance from the Equator. M(x) is a Heaviside step function that only considers upward motion.

To determine the individual components of the BJ index, we utilize monthly variables derived from the CMIP6 simulations and the SODA dataset, spanning the period from 1980 to 2014. The climatological mean is defined as the average over this entire period, with monthly anomalies representing deviations from the climatological monthly values. In the case of the GISS-E2-1-H model, which lacks vertical velocity outputs, we diagnose vertical velocity by integrating horizontal divergence from the surface79. The calculation of the BJ index components is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2. Model performance is evaluated by comparing the root-mean-square error (RMSE) of the six BJ components between each model and SODA.

Framework and training of ANNs

The ANN employed in this study captures the complex, nonlinear relationship between the SST mean state in the tropical Pacific and the amplitude of ENSO SST variability. This ANN architecture comprises an input layer, four convolutional layers equipped with Batch Normalization, LeakyReLU activation functions, and max-pooling, followed by three dense layers, culminating in an output layer (Supplementary Fig. 3). It is widely recognized that climate models often exhibit substantial SST biases in the tropical Pacific Ocean80,81. To ameliorate the effects of climatological bias, the ANN is trained on the SST mean state after removing the climatological mean from 1870 to 2014. Following the computations through the hidden layers, the ANN outputs the contemporary ENSO SST amplitude (Supplementary Table 2).

Hyperparameter selection is conducted following standard practice, which involves evaluating a limited number of combinations. Our preliminary experiments evaluated various ANN configurations (Supplementary Table 3). No validation performance differences emerged across configurations. In general, underfitting occurs when the sample size significantly exceeds the number of trainable parameters, and overfitting occurs when the sample size is substantially smaller than the number of trainable parameters. With 1100–3800 samples and 2617 trainable parameters, our configuration maintains an empirical balance which mitigates both risks. Consequently, we retained the baseline architecture without further hyperparameter tuning, prioritizing physical plausibility over marginal accuracy gains.

Each ANN is individually trained on data samples derived from a single CMIP6 model, utilizing the TensorFlow library82. The training employs a learning rate of 10−3 and leverages the Adam optimizer to minimize the squared error between the ANN outputs and the CMIP-modeled ENSO SST amplitudes. To avoid overfitting, the ANNs are subjected to a maximum of 1000 training epochs with the implementation of early stopping before achieving the best performance on observational data. To mitigate the uncertainty and generalization error inherent in ANN predictions, we employ ensemble learning83, a technique akin to ensemble forecasting in climate research. In general, a larger number of learners is better. However, in this study, when the number of learners exceeds 30, the RMSE between the average prediction and the true value no longer shows significant changes (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, this involves the generation of 50 distinct learners, each initialized with random weights. The mean of these learners is then adopted as the definitive mapping of ENSO SST amplitudes from the SST mean state.

Occlusion sensitivity

Occlusion sensitivity analysis is a technique used to understand which parts of an input image are most important for the decisions of CNNs84,85. In this research, we employ this approach to assess the influence of the SST mean state on the amplitude of ENSO SST variability. We begin by individually occluding each grid point within the SST mean field and then inputting the modified SST field into the ANN. The ANN output with the occluded input field deviates from the output with the unoccluded field, with these discrepancies being quantified using RMSE. This error metric serves as an indicator of the importance of the SST mean state at each grid point on the ANN output of the ENSO SST amplitude. We sequentially apply this procedure to the entire grid, which spans 50 by 165 points, and normalize the RMSE at each grid point by dividing it by the maximum value across the entire field. Through this analysis, we can identify specific subregions within the tropical Pacific where the SST mean state plays a critical role in estimating the ENSO SST amplitude.

Weighting scheme

Given the varying performance of different ANNs on observational data (red bars in Fig. 1a), it is necessary to assign weights to the outputs of each ANN when computing the multi-ANN ensemble average. Logically, ANNGISS-E2-1-H warrants the highest weight due to its largest correlation coefficient, whereas ANNACCESS-ESM1-5 should be assigned the lowest weight. In this study, the weight attributed to the i-th ANN is defined as the likelihood that the observational data are stem from that ANNi:

Using the law of Bayes’ rule

ACCESS-CM2 and ACCESS-ESM1-5 are from the same institution; however, given the substantial differences in their performance on observational data, it is reasonable to assume that they are independent. Furthermore, although GISS-E2-1-G and GISS-E2-1-H also come from the same institution, their oceanic components are entirely different, leading to the assumption of their independence in this study. Therefore, assuming that the 11 climate models are independent,

The normalized outputs of the ANNs are generally assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution86,87. Thus,

where di and ri represent the averaged Euclidean distance and the correlation coefficient (red bars in Fig. 1a), respectively, between the historical observation and the ANNi estimate. n is the number of observational samples. Ultimately, the weight assigned to the i-th ANN is denoted as

Model-as-truth approach

Model-as-truth (also called pseudo-observation) uses model data as a proxy for actual observations to assess the robustness of model evaluation approaches. In this framework, we select historical and future simulations from a random climate model as the truth. Similar to processing real observations (as in Supplementary Fig. 6), the historical SST mean state from the selected climate model is input into ANNs. The correlation between each ANN output and the simulated ENSO SST amplitude is calculated. This correlation coefficient measures the historical performance of each ANN and determines its weight. When simulated tropical Pacific warming patterns are input to the ANNs, the performance of the ANN projections is evaluated by comparing the performance-weighted average with the projections from the selected climate model (Fig. 4a).

Uncertainty estimates of future projections

We generate ANN-based projections using future SST mean states that are adjusted by subtracting the climatological bias. This approach isolates model-specific warming patterns and directly addresses the following question: How would ENSO SST variability change if a model-simulated warming pattern occurred in the real world? Specifically, for a future period (e.g., 2071–2100), the contemporary warming pattern is derived by subtracting the model-simulated climatological SST from the projected SST of that period. If this model-projected warming pattern were to emerge in the real world by the end of this century, the resulting tropical Pacific SST would be: SST2071-2100 - Modeled Climatology + Observed Climatology, which is equivalent to SST2071-2100 - Climatological Bias. Thus, this method does not constitute traditional bias correction. Instead, it evaluates the potential changes arising from superimposing the model’s projected warming pattern onto the present-day observed climatology.

An observational constraint is applied to future ENSO SST amplitude projections using the ANNobs, which describes the observed relationship between the tropical Pacific SST mean state and ENSO SST amplitude. Eleven sets of future SST mean states are input into the ANNobs, with each set comprising 77 samples, including those from 1995–2024, 1996–2025,…, and 2071–2100 under the SSP5-8.5 emission scenario. This process yields 11 time series of constrained ENSO amplitude projections, as illustrated in Fig. 5a by the red shading. The future projections (11 CMIP models × 77 time points) of the CMIP-original and ANN-constrained are compared using probability density distributions (bars in Fig. 5a), and Gaussian fits provide the mean and standard deviation (confidence interval) for each ensemble.

Linear approximation of ANNobs

The future SST mean states under the SSP5-8.5 emission scenario (77 samples, including 1995–2024, 1996–2025,…, and 2071–2100) from 11 climate models, after subtracting the respective climatological SST bias, are then input into ANNobs to project future ENSO SST amplitudes (ESA; 11 time series, each including 77 years). ANNobs is a nonlinear statistical model that depends on SST in all regions of the tropical Pacific. Nevertheless, the occlusion sensitivity (Fig. 2a) indicates that ANNobs depends primarily on the mean states of SST in the central and far-eastern equatorial Pacific (SSTCP and SSTEP, the average SST within the respective boxes). Thus, the 77 × 11 ENSO SST amplitudes can be described as a function of the east-minus-west SST gradient (GD = SSTEP - SSTCP) and the SST mean state in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 14). Both dependencies are largely linear (red dashed lines), allowing the approximation of ANNobs with a binary linear function: ESA = α + β·GD + γ·SSTEP. Linear fitting to the 77 × 11 samples yields ESA = 4.78 + 0.61·GD - 0.08·SSTEP (shading in Fig. 5c). Based on this function, reversals occur when the trajectory is tangent to the contour lines. Quantitatively, ∆ESA = 0.61·∆GD - 0.08·∆SSTEP. Since ∆GD = ∆SSTEP - ∆SSTCP, ∆ESA < 0 when ∆SSTEP < 1.15·∆SSTCP.

Data availability

All datasets used in this study are publicly available. The CMIP6 data are available from https://esgf-ui.ceda.ac.uk/cog/search/cmip6-ceda/; the COBE2 data are available from https://ds.data.jma.go.jp/tcc/tcc/products/elnino/cobesst2_doc.html; the ERSST data are available from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/extended-reconstructed-sst; the HadISST data are available from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/; the SODA data are available from https://dsrs.atmos.umd.edu/DATA/soda3.3.2/REGRIDED/ocean/.

Code availability

Codes required to reproduce the study are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14942083.

References

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an integrating concept in earth science. Science 314, 1740–1745 (2006).

Timmermann, A. et al. El Niño–Southern Oscillation complexity. Nature 559, 535–545 (2018).

Ward, P. J. et al. Strong influence of El Niño Southern Oscillation on flood risk around the world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15659–15664 (2014).

Cai, W. et al. Climate impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on South America. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 215–231 (2020).

Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. Persistent effect of El Niño on global economic growth. Science 380, 1064–1069 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. inClimate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Collins, M. et al. The impact of global warming on the tropical Pacific Ocean and El Niño. Nat. Geosci. 3, 391–397 (2010).

Fredriksen, H.-B., Berner, J., Subramanian, A. C. & Capotondi, A. How does El Niño–Southern Oscillation change under global warming—A first look at CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090640 (2020).

Cai, W. et al. Increased variability of eastern Pacific El Niño under greenhouse warming. Nature 564, 201–206 (2018).

Cai, W. et al. Increased ENSO sea surface temperature variability under four IPCC emission scenarios. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 228–231 (2022).

Bellenger, H., Guilyardi, E., Leloup, J., Lengaigne, M. & Vialard, J. ENSO representation in climate models: from CMIP3 to CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 42, 1999–2018 (2014).

Guilyardi, E., Capotondi, A., Lengaigne, M., Thual, S. & Wittenberg, A. T. in El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate (eds Michael J. McPhaden, Agus Santoso, & Wenju Cai) Ch. ENSO Modeling, 199–226 (AGU, 2020).

Cai, W. et al. Anthropogenic impacts on twentieth-century ENSO variability changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 407–418 (2023).

Lian, T., Chen, D., Ying, J., Huang, P. & Tang, Y. Tropical Pacific trends under global warming: El Niño-like or La Niña-like?. Natl. Sci. Rev. 5, 810–812 (2018).

Seager, R. et al. Strengthening tropical Pacific zonal sea surface temperature gradient consistent with rising greenhouse gases. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 517–522 (2019).

Fedorov, A. V., Hu, S., Wittenberg, A. T., Levine, A. F. Z. & Deser, C. in El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate.(AGU, 2020).

Cai, W. et al. in El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate.(AGU, 2020).

Kim, S. T. et al. Response of El Niño sea surface temperature variability to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 786–790 (2014).

Beobide-Arsuaga, G., Bayr, T., Reintges, A. & Latif, M. Uncertainty of ENSO-amplitude projections in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 56, 3875–3888 (2021).

Peng, Q., Xie, S.-P. & Deser, C. Collapsed upwelling projected to weaken ENSO under sustained warming beyond the twenty-first century. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 815–822 (2024).

Geng, T., Cai, W., Jia, F. & Wu, L. Decreased ENSO post-2100 in response to formation of a permanent El Niño-like state under greenhouse warming. Nat. Commun. 15, 5810 (2024).

Eyring, V. et al. Taking climate model evaluation to the next level. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 102–110 (2019).

Hegerl, G. C. et al. Toward consistent observational constraints in climate predictions and projections. Front. Clim. 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.678109 (2021).

Jin, F.-F. et al. in El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate (eds Michael J. McPhaden, Agus Santoso, & Wenju Cai) Ch. Simple ENSO Models, 119–151 (AGU, 2020).

Hall, A., Cox, P., Huntingford, C. & Klein, S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 269–278 (2019).

Nowack, P. et al. Response of stratospheric water vapour to warming constrained by satellite observations. Nat. Geosci. 16, 577–583 (2023).

Beucler, T. et al. Climate-invariant machine learning. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj7250 (2024).

Ham, Y.-G., Kim, J.-H. & Luo, J.-J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 573, 568–572 (2019).

Eyring, V. et al. Pushing the frontiers in climate modelling and analysis with machine learning. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 916–928 (2024).

Immorlano, F. Transferring climate change physical knowledge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2413503122 (2025). and Coauthors.

Barnett, T. P. et al. ENSO and ENSO-related predictability. Part I: Prediction of equatorial pacific sea-surface temperature with a hybrid coupled ocean-atmosphere model. J. Clim. 6, 1545–1566 (1993).

Zhou, L. & Zhang, R.-H. A self-attention–based neural network for three-dimensional multivariate modeling and its skillful ENSO predictions. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf2827 (2023).

Fang, W. & Sha, Y. ENSO-Former: spatiotemporal fusion network based on multivariate and dual-branch transformer for ENSO prediction. Clim. Dyn. 63, 131 (2025).

Mamalakis, A., Barnes, E. A. & Ebert-Uphoff, I. Investigating the Fidelity of Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods for Applications of Convolutional Neural Networks in Geoscience. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. 1, e220012 (2022).

Dewitte, B., Yeh, S.-W. & Thual, S. Reinterpreting the thermocline feedback in the western-central equatorial Pacific and its relationship with the ENSO modulation. Clim. Dyn. 41, 819–830 (2013).

Carréric, A. et al. Change in strong Eastern Pacific El Niño events dynamics in the warming climate. Clim. Dyn. 54, 901–918 (2020).

Cai, W. et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 111–116 (2014).

Fedorov, A. V. & Philander, S. G. Is El Niño Changing?. Science 288, 1997–2002 (2000).

Capotondi, A. & Sardeshmukh, P. D. Is El Niño really changing?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8548–8556 (2017).

Zhao, B. & Fedorov, A. The effects of background zonal and meridional winds on ENSO in a coupled GCM. J. Clim. 33, 2075–2091 (2020).

Heede, U. K. & Fedorov, A. V. Towards understanding the robust strengthening of ENSO and more frequent extreme El Niño events in CMIP6 global warming simulations. Clim. Dyn. 61, 3047–3060 (2023).

Samek, W. in Explainable Deep Learning AI (eds Jenny Benois-Pineau, Romain Bourqui, Dragutin Petkovic, & Georges Quénot) Ch. Explainable deep learning: concepts, methods, and new developments, 7–33 (Academic Press, 2023).

Capotondi, A., Wittenberg, A. T., Kug, J.-S., Takahashi, K. & McPhaden, M. J. in El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate. (AGU, 2020).

Schlör, J., Strnad, F., Capotondi, A. & Goswami, B. Contribution of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Diversity to Low-Frequency Changes in ENSO Variance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109179 (2024).

Zhang, R.-H., Gao, C. & Feng, L. Recent ENSO evolution and its real-time prediction challenges. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwac052 (2022).

Dieppois, B. et al. ENSO diversity shows robust decadal variations that must be captured for accurate future projections. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 212 (2021).

Hourdin, F. et al. The art and science of climate model tuning. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 98, 589–602 (2017).

Nowack, P. & Watson-Parris, D. Opinion: Why all emergent constraints are wrong but some are useful – a machine learning perspective. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 25, 2365–2384 (2025).

Liang, Y., Gillett, N. P. & Monahan, A. H. Accounting for Pacific climate variability increases projected global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 608–614 (2024).

Ricard, L., Falasca, F., Runge, J. & Nenes, A. network-based constraint to evaluate climate sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 15, 6942 (2024).

Li, T., Zwiers, F. W. & Zhang, X. Should we think of observationally constrained multidecade climate projections as predictions?. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt6485 (2025).

Klein, S. A., Hall, A., Norris, J. R. & Pincus, R. Low-cloud feedbacks from cloud-controlling factors: A review. Surv. Geophys. 38, 1307–1329 (2017).

McPhaden, M. J. A 21st century shift in the relationship between ENSO SST and warm water volume anomalies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051826 (2012).

Wyman, D. A., Conroy, J. L. & Karamperidou, C. The Tropical Pacific ENSO–mean state relationship in climate models over the last millennium. J. Clim. 33, 7539–7551 (2020).

Callahan, C. W. et al. Robust decrease in El Niño/Southern Oscillation amplitude under long-term warming. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 752–757 (2021).

Simpson, I. R. Confronting Earth System Model trends with observations. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt8035 (2025).

Bi, D. et al. Configuration and spin-up of ACCESS-CM2, the new generation Australian community climate and earth system simulator coupled model. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 70, 225–251 (2020).

Ziehn, T. et al. The Australian Earth System Model: ACCESS-ESM1.5. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 70, 193–214 (2020).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001916 (2020).

Swart, N. C. et al. The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 4823–4873 (2019).

Döscher, R. et al. The EC-Earth3 Earth system model for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 2973–3020 (2022).

Kelley, M. et al. GISS-E2.1: Configurations and climatology. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS002025 (2020).

Boucher, O. et al. Presentation and evaluation of the IPSL-CM6A-LR climate model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS002010 (2020).

Hajima, T. et al. Development of the MIROC-ES2L Earth system model and the evaluation of biogeochemical processes and feedbacks. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 2197–2244 (2020).

Yukimoto, S. et al. The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model Version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: Description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J. Meteor. Soc. Jpn. 97, 931–965 (2019).

Seland, Ø et al. Overview of the Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM2) and key climate response of CMIP6 DECK, historical, and scenario simulations. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 6165–6200 (2020).

Coats, S. & Karnauskas, K. B. Are simulated and observed Twentieth Century Tropical Pacific Sea surface temperature trends significant relative to internal variability?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9928–9937 (2017).

Deser, C., Phillips, A. S. & Alexander, M. A. Twentieth century tropical sea surface temperature trends revisited. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043321 (2010).

Solomon, A. & Newman, M. Reconciling disparate twentieth-century Indo-Pacific ocean temperature trends in the instrumental record. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 691–699 (2012).

Ishii, M., Shouji, A., Sugimoto, S. & Matsumoto, T. Objective analyses of sea-surface temperature and marine meteorological variables for the 20th century using ICOADS and the Kobe Collection. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 865–879 (2005).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002670 (2003).

Kadow, C., Hall, D. M. & Ulbrich, U. Artificial intelligence reconstructs missing climate information. Nat. Geosci. 13, 408–413 (2020).

Plésiat, É, Dunn, R. J. H., Donat, M. G. & Kadow, C. Artificial intelligence reveals past climate extremes by reconstructing historical records. Nat. Commun. 15, 9191 (2024).

Carton, J. A., Chepurin, G. A. & Chen, L. SODA3: A new ocean climate reanalysis. J. Clim. 31, 6967–6983 (2018).

Lou, J., Newman, M. & Hoell, A. Multi-decadal variation of ENSO forecast skill since the late 1800s. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 89 (2023).

Jin, F.-F., Kim, S. T. & Bejarano, L. A coupled-stability index for ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027221 (2006).

Johnson, G. C., McPhaden, M. J. & Firing, E. Equatorial Pacific Ocean horizontal velocity, divergence, and upwelling. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 31, 839–849 (2001).

Zuidema, P. et al. Challenges and prospects for reducing coupled climate model SST biases in the eastern tropical Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: The U.S. CLIVAR eastern tropical oceans synthesis working group. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 97, 2305–2328 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Physics-informed deep-learning parameterization of ocean vertical mixing improves climate simulations. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwac044 (2022).

Abadi, M. et al. Tensorflow: A system for large-scale machine learning. 12th USENIX symposium on operating systems design and implementation (OSDI 16), 265–283 (2016).

Zhou, Z.-H. in Encyclopedia of Biometrics (eds Stan Z. Li & Anil Jain) 270–273 (Springer US, 2009).

Zeiler, M. D. & Fergus, R. Comput. Vision – ECCV 2014 (2014).

Ham, Y.-G. et al. Anthropogenic fingerprints in daily precipitation revealed by deep learning. Nature 622, 301–307 (2023).

Sanderson, B. M., Knutti, R. & Caldwell, P. A Representative democracy to reduce interdependency in a multimodel ensemble. J. Clim. 28, 5171–5194 (2015).

Cox, P. M. et al. Sensitivity of tropical carbon to climate change constrained by carbon dioxide variability. Nature 494, 341–344 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF0801404), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42276008, 42030410), the Taishan Scholars Program (tsqn202408274), Laoshan Laboratory (LSKJ202202402), and Jiangsu Innovation Research Group (JSSCTD 202346).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., R.-H.Z., and F.W. designed the study. W.C. provided physical insight into the results. Y.Z. performed the analysis and drafted the paper. D.L. and S.G. contributed to the model-as-truth approach. Y.Z., R.-H.Z., F.W., W.C., D.L., S.G., and Y.L. discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wei Fang, Mohammad Naisipour, and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Zhang, RH., Wang, F. et al. Projection of ENSO using observation-informed deep learning. Nat Commun 16, 7736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63157-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63157-z