Abstract

Memristive passive crossbar circuits hold great promise for neuromorphic computing, offering high integration density combined with massively parallel operation. However, scaling up the integration complexity of such circuits remains challenging due to low device yield, stemming from the intrinsic properties of filamentary switching and limitations in current crossbar fabrication technologies. Here, we report a scalable passive crossbar device technology achieved through a co-design approach for memristors and crossbar structures. The proposed hardware platform is fabricated using CMOS-compatible processes without complex and high-temperature steps, enabling high device yield along with reliable and multibit operation. Importantly, the fabrication process is successfully scaled to a 4-inch wafer, maintaining an average device yield (>~95%) and preserving key switching characteristics. The potential of this platform is showcased by implementing image classification of the fashion MNIST benchmark with an ex-situ trained spiking neural network. We believe that our work represents a significant step toward brain-scale neuromorphic computing systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High integration complexity is fundamentally indispensable for an advanced neuromorphic hardware system aiming to achieve cognitive functionalities comparable to those of the biological brain1,2,3,4,5,6,7. It is well-known that the brain comprises approximately 1011 neurons and 1015 synapses with its structural complexity and dense connectivity, all contained within a compact size8,9. This has naturally driven a growing demand for the development of highly integrated neuromorphic chips. For example, BrainScaleS, part of the European Human Brain Project, implemented a neuromorphic architecture on a single chip with an analog core of 512 neurons and ~131k 6-bit SRAM (static random-access memory) crossbar synapses based on 65 nm technology (further described in Supplementary Note 1)7, demonstrating a promising tool for advanced computing and neuroscience research. However, this platform remains far from the brain’s structure, suggesting the need for a physical solution to further enhance integration complexity.

In this context, memristive device technology holds great promise for implementing artificial synapses to address this challenge. To date, there has been substantial progress in actively integrated memristor circuits utilizing a one-transistor-one-memristor (1T1M) configuration10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. This is mainly because a dedicated transistor can regulate its corresponding memristor, thereby effectively enhancing the controllability for memristors due to 1T per memristor. Various demonstrations of 1T1M active crossbar circuits have been presented by both academia and industry. For example, Yao et al. implemented convolutional neural networks by integrating eight 128 × 16 1T1M circuits13. Wan et al. suggested a versatile memristor-based compute-in-memory chip for diverse model architectures, where 48 cores consisting of a 256 × 256 1T1M crossbar circuit (in total, ~3 million memristors) were monolithically integrated with a CMOS (complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor) circuit14. Song et al. reported an analog in-memory computing accelerator consisting of 256 × 256 active circuits, fabricated in a commercial foundry and fully integrated with CMOS circuitry on a 12-inch wafer17. Although this approach has been regarded as a practical solution for implementing large-scale integration, passively integrated memristive circuits are especially promising due to their higher density potentials and integration capability with conventional CMOS chips at lower fabrication cost19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. This key benefit arises from the 4F2 passive crossbar structure, which arranges memristors at each crosspoint (F is the feature size) to achieve much higher integration density compared to similar-precision conventional memories31,32,33,34. For example, even assuming ~400% peripheral overhead due to programming circuitry24, such circuits could be more than 25× denser than 4-bit SRAM typically required for neuromorphic inference accelerators (and even more so for 6-bit SRAM utilized BrainScaleS system)7. This packing density can be further enhanced by vertically stacking multiple crossbar circuits into a 3D-integrated multilayered architecture, where density scales with the number of stacked layers (n), yielding 4F2/n19,27. Consequently, memristive passive crossbar circuits can significantly increase integration complexity, making it a key enabler for brain-scale neuromorphic computing (further described in the “Discussion” section).

Nevertheless, the current extensive demonstrations generally remain limited to small-scale passive crossbar circuits, which inevitably confines their use to relatively simple systems. The primary challenge results from the difficulty of controlling the switching filament. Since filament formation is based on the electroforming process via soft breakdown31,32,33,34, memristors are likely to experience hard breakdown during operation, leading to low device yield and undesirable switching characteristics. These issues become more pronounced when memristors are organized into crossbar circuits able to affect one another. Moreover, voltage drops and leakage currents inherent to the passive crossbar structure present another significant challenge for scaling up21,31,32,33,34,35. To address these bottlenecks, various approaches have been explored in terms of device, fabrication, and circuit19,23,24,27,28,29,30,36,37,38,39. For example, So et al. proposed a 24 × 24 passive crossbar circuit incorporating naturally oxidized AlOx and annealing processes, effectively suppressing current overshoot and improving device yield29. Park et al. developed a 16 × 16 circuit using an Al2O3-based trilayer oxide stack, where the Al2O3 barrier minimized leakage current and increased nonlinearity28. Jeon et al. demonstrated a 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuit based on self-rectifying memristors, enhancing programming reliability and selectivity by reducing leakage currents30. Adam et al. addressed rabbit ear formations along electrode lines via Ar ion beam etching, reducing the hard-breakdown risk in a 3D stacked 2 × 10 × 10 circuit19. Kim et al. leveraged a finely calibrated CMP (chemical mechanical polishing) process for a 64 × 64 circuit, mitigating voltage drop with high-aspect-ratio electrodes while decreasing rabbit-ear issues24. Zidan et al. utilized multiple small-scale crossbar circuits rather than a single large crossbar circuit to alleviate parasitic effects from line resistance and leakage currents21. Although all these methods are undoubtedly noteworthy, most of them are still constrained by several critical limitations such as deficient device yield, slow speed, poor retention, speed-retention dilemma, incompatibility with CMOS process, and/or requirement of labor-intensive calibration processes. Consequently, achieving practical scalability remains elusive within current memristor technology due to the lack of an effective solution to address these challenges all at once, and this can account for the slow progress on memristive passive crossbar circuits.

Simultaneously, wafer-scale fabrication is highly demanded for the development of neuromorphic hardware systems3,7,40,41,42. Considering that the required communication bandwidth in such systems can surpass 10¹¹ neural events per second43, wafer-scale fabrication offers potential advantages over conventional flip-chip technology with a very high I/O count, especially in reducing complicated circuit designs and high packaging costs by directly interconnecting chips on a wafer. However, the benefits of wafer-scale integration must be secured with high device yield, which remains a critical hurdle for the widespread adoption of memristive passive crossbar circuits. Recently, Chen et al. reported wafer-scale integration of multiple 10 × 10 passive crossbar circuits based on 2D h-BN memristors, exhibiting high yield and low switching variation41. Tang et al. utilized a solution-processed 2D MoS2 memristor for wafer-scale integration of diverse crossbar circuits (from 1 × 1 to 10 × 10 circuits)42. However, although these platforms are promising progress, they remain confined to small-sized 10 × 10 crossbar circuits. Further, wafer-scale fabrication of passive crossbar circuits based on metal-oxide memristors, enabling high yield and reliable switching behaviors, has yet to be reported.

A main contribution of this study is to appropriately combine and adapt the separate solutions into a unified fabrication scheme that employs CMOS-compatible and simple processes. Especially, the device yield of memristive passive crossbar circuits can be effectively enhanced, while avoiding the labor-intensive fabrication steps and strict process flows. With the co-design approach, we demonstrate wafer-scale high-yield fabrication of all passive crossbar circuits (>~95 % yield on average) beyond a single isolated standout result, while securing essential switching parameters. Further, as a potential application, a multilayered spiking neural network (SNN) is implemented based on the proposed crossbar circuits. The proposed platform, based on the co-design approach, offers a route toward practical scalability of memristive passive crossbar circuits.

Results

Design and fabrication

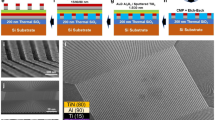

Figure 1a–e illustrates the fabrication processes. All electrode lines (Pt/Ti) were patterned and deposited with a maskless photolithography and an electron beam deposition. The bilayer oxides (TiO2/Al2O3) are sequentially stacked by using the atomic layer deposition (ALD) process. As a result, the device structure consists of Pt/Ti/TiO2/Al2O3/Pt/Ti at each crosspoint (Fig. 1f), which was confirmed by the ex situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The detailed fabrication processes are presented in Method section and Supplementary Fig. 2. During the fabrication process, there are two noticeable points as follows. One is that the bottom electrodes were patterned based on a back-filling process (Fig. 1a–c). This step can partially mitigate the rabbit ear that is sharply formed along the sidewall of the bottom electrodes after the patterning (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), which might be associated with the interplay between metal evaporation and etching processes44,45,46. Because the applied electric field can be excessively concentrated and enhanced around the rabbit ear due to its sharp geometry19,24,38, memristors are susceptible to either the hard breakdown or ON-stuck problem, which is one fundamental reason for low device yield in crossbar circuits. Considering that the location, size, and number of the rabbit ears vary at each crosspoint, it is likely that each device experiences a different effective electric field despite an application of the same input voltage. Hence, this back-filling technique is beneficial to ensure high yield and reliable crossbar circuits with low cost and simple methodology. Another point is the hexagonal line shape to minimize the voltage drop along the electrode lines between memristors. This naturally alleviates the forming failure or OFF-stuck problem, while obviating the need for a complex process to achieve high aspect ratios required for thick electrodes. The device structure and its design will be discussed later.

a–e Schematics of fabrication steps. f Magnified schematic of a Pt/Ti/TiO2/Al2O3/Pt/Ti memristor at a certain crosspoint in panel (e) (red dotted line). g. A top-view optical image of multiple 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuits fabricated on a 4-inch wafer. h–j Top-view SEM images of a representative 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuit (h), along with magnified views of a 3 × 3 sub-array (i) and a 1 × 1 sub-array (j). The device line width is 2 μm. The scale bar for (h–j) is 100 μm, 10 μm, and 2 μm, respectively. k Cross-sectional high-resolution TEM image of junction structure at the crosspoint. The scale bar is 5 nm. l A top-view optical image of the hardware measurement system with the fabricated passive crossbar circuits (inset). The crossbar circuit is wire-bonded and mounted on the board system. The scale bar is 30 mm and 3 mm (inset). m Histograms of the device yield as a function of sample number. Samples 1 and 2 utilize the hexagonal line alone and the back-filling process alone, respectively. Sample 3 employs the combined effect of the two methods, which is our approach. The inset represents the switching success (yellow) and failure (green, blue), respectively. Memristors without distinguishable ON and OFF states were considered as switching failures. n A distribution map of a 32 × 32 crossbar circuit exhibiting switching success and failure as yellow and black boxes, respectively. o, p A magnified view of the SEM image at a certain crosspoint for samples 1 and 3. This indicates that the back-filling process can mitigate the rabbit ear formed along the bottom electrode lines to some degree. The scale bar for (o, p) is 1 μm. q, r Top-view SEM images of 4 × 5 sub-arrays for samples 2 and 3, revealing a clear difference in line shape. This can prevent the reduction of the applied electric field across multiple memristors. The scale bar for (q, r) is 10 μm.

Figure 1g shows a top-view optical image of multiple 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuits formed on a 4-inch wafer based on the proposed crossbar circuit design. Generally, as passive crossbar size expands, several undesired effects at the device (e.g., yield and variation) and circuit level (e.g., voltage drop and sneak current) become severe21,31,32,33,34. In this regard, the arrangement of multiple passive crossbar circuits with an appropriate size (e.g., 16 × 16 or 32 × 32) can offer a feasible scaling approach, because it can minimize the aforementioned problems without 1T21,31. Figure 1h–j show top-view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the representative 32 × 32 crossbar array (Fig. 1h) and its enlarged views of 3 × 3 (Fig. 1i) and 1 × 1 sub-arrays (Fig. 1j), revealing a cell line width of approximately 2 μm. Figure 1k shows a cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) image of the memristor at a crosspoint, confirming the Pt/Ti/TiO2/Al2O3/Pt/Ti junction structure. Note that the corresponding energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) results are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. Figure 1l shows the representative 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuit mounted on a custom-built test board. With this measurement setup, our design was confirmed to clearly enhance device yield, as shown in Fig. 1m. Here, samples 1, 2, and 3 represent the cases of using the hexagonal line alone, the back-filling process alone, and the back-filling process with the hexagonal line, respectively. When compared to other cases (71.2 % (729/1024) for sample 1 and 78.2 % (801/1024) for sample 2), it is likely that our design exhibits a higher device yield (98.4 % (1008/1024) for sample 3) as visualized in Fig. 1n. These results can be explained by the partial reduction of rabbit ear (Fig. 1o, p) and voltage loss (Fig. 1q, r), verifying the benefits of our approach. Although this demonstration alone is not sufficient to claim generalization, these results can reflect the meaningful trends of device yield driven by each fabrication approach. The detailed device yields for samples 1 and 2 are provided in Supplementary Fig. 5. Further discussion on the merits of our approach is presented in Supplementary Note 2 of Supplementary Information. Moreover, in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 3, we present theoretical analysis and discussion on our crossbar structure design by considering device behaviors and essential parameters of crossbar circuits.

Electrical characteristics

Figure 2a shows a representative current–voltage (I–V) switching curve of a memristor in the 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuit, representing the currents in the OFF state (IOFF) and ON state (ION) at VREAD = 0.2 V. It has been suggested that the memristive switching in similar material systems results from the formation and rupture of the switching filament based on oxygen vacancies (VO) between two-terminal electrodes, which is related to the combination of the electric field and Joule heating effect. After the completion of the initial electroforming process (Supplementary Fig. 7), as shown in Fig. 2a, a typical bipolar switching behavior is observed with SET (VSET = ~ 1.3 V) and RESET voltage (VRESET = ~ −2.0 V). The slightly larger VRESET than VSET might be attributed to the Joule heating-driven RESET mechanism (i.e., a certain RESET current is required). The I changes nonlinearly according to the applied voltage. Such I–V nonlinearity might be mainly associated with the intrinsic characteristics of TiO247, with some helps of 1.5 nm Al2O3 layer able to limit VO migration rate and reduce the currents at low voltage region (Supplementary Fig. 8). In the viewpoint of the charge transport, the IOFF is governed by the tunneling conduction, which is consistent with the high bandgap tunnel barrier of Al2O3 (~9.0 eV) sandwiched between switching filament and bottom electrode (Supplementary Fig. 9). For the ION, Ohmic-like conduction is observed, indicating the complete connection of filament between two electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 9). Note that the hard breakdown phenomenon appears more frequently when Al2O3 thickness exceeds 2 nm, suggesting the necessity of the optimal thickness of Al2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 10).

a A representative I–V curve of the passive crossbar circuit after the completion of the electroforming process. A sudden increase in the current is observed at ~1.3 V. This threshold voltage is defined as VSET, which can switch the device from the IOFF to the ION. Conversely, the ION drops and fluctuates starting at ~−2.0 V. This VRESET can return the device from IOFF to ION. The ION and IOFF are read at VREAD = 0.2 V. The top and bottom electrode lines for the selected memristor were biased and grounded, respectively. b, c Distribution maps of VSET (blue) (b) and VRESET distribution (red) (c) for all the memristors (1,024 memristors) in the fabricated 32 × 32 crossbar circuit. The black colored boxes indicate switching-failure devices with low DR (<3). d Statistical histograms of all the VSET and VRESET values, well-fitted by the normal distribution curve. e–g Statistical histograms of ION (e), IOFF (f), and DR (g) for all the switchable memristors (1008 memristors). The inset in panel (g) shows the distribution map of DR values, confirming their acceptable uniformity. These switching parameters were obtained at VREAD = 0.2 V. h Endurance cycling test of the memristor over 105 cycles by programming at VSET = 1.6 V and VRESET = −2.7 V for W = 80 μs. ION and IOFF were read at VREAD = 0.2 V for 1 ms. i Retention test of the memristor for >105 s after the completion of the SET- and RESET-switching transition under the same VSET, VRESET, and W. ION and IOFF were consecutively measured at VREAD = 0.2 V for W = 1 ms with an interval (Δt) of 1 s.

Figure 2b, c shows the statistical distribution of VSET (blue) and VRESET (red) for all the memristors in the 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuit. Here, the black boxes represent the switching failure (typically, devices with small dynamic range (DR, i.e., ION/IOFF at VREAD < 3)). The average values for VSET and VRESET are ~1.36 ± 0.40 V and −2.09 ± 0.27 V, respectively. All the distributions are well-fitted by the normal distribution curve, as shown in Fig. 2d. The observed variation in switching voltage might be ascribed to the inhomogeneous filament shape formed during the electroforming process. This could be effectively mitigated if the device size decreases or a form-free memristor is used. Figure 2e–g shows the statistical histograms of ION, IOFF, and DR for all the switchable memristors of the passive crossbar circuit (1008 memristors) with the visualization of DR distribution (the inset of Fig. 2g). The average values for ION, IOFF, and DR are (3.23 ± 0.11) × 10−5 A, (3.30 ± 0.14) × 10−6 A, and 9.78 ± 0.14, respectively. The statistical distributions of ION and IOFF are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 11. The relatively large variation in IOFF could be attributed to an incomplete RESET process during the I–V sweeping operation. This indicates that the DR and its variation can be further improved by completing the RESET process, although this may limit the endurance performance in some degree (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Note 4). Note that the detailed measurement schemes for the passive circuit are described in the Method section.

Figure 2h, i show the consecutive switching and retention properties of the selected memristor over 105 cycles and 105 s. Statistical investigation of endurance and retention properties was also performed with the randomly selected 100 memristors (Supplementary Figs. 13–20 and Note 5). Additionally, the memristor can also maintain its I–V consecutive sweeps for more than 1000 times (Supplementary Fig. 21). These results suggest good operating stability and long retention time with acceptable switching speed (pulse width (W) = 80 μs). The average ION and IOFF for all endurance cycles were (1.66 ± 0.43) × 10−5 A and (2.51 ± 0.93) × 10-6 A, whereas (17.67 ± 0.03) × 10−6 A and (1.31 ± 0.05) × 10−6 for the retention test (Supplementary Fig. 22). Moreover, the memristors were observed to follow the standard scaling laws, where IOFF decreases with size, while ION remains nearly unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 23). This suggests the potential for scaling down to a nanosized memristor, which is further discussed in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig 23 and Note 6. Consequently, our design and fabrication demonstrate the potential for high yield and reliable switching performances even without the use of 1 T.

Scaling up integration

A spatial analysis over a 4-inch wafer was statistically conducted for integration scalability demonstration (Fig. 3). We sampled and characterized 100 memristors from the same region across all dies (i.e., 69 crossbar circuits) due to the limited package resources. Considering the passive crossbar structure and lateral length scale, this sampling from the same region of each die can be considered an appropriate approach for the spatial analysis of the multiple passive crossbar circuits across the wafer (detailed in Supplementary Note 7). Based on the estimation scheme, we found that 365 memristors did not function well (i.e., DR < 3) among all 6900 memristors, which was estimated to be the average device yield of 94.71 ± 4.18 % as shown in Figs. 3a, b. This result highlights the uniform and high die-to-die device yield over the wafer, supporting the scalability of our approach. The small spatial variation in the yield could be attributed to the overall reduction of rabbit ear across the wafer, which decreases the possibility of hard-breakdown phenomena caused by an excessive electric field and reduced oxide thickness. Figure 3c–e shows the statistical histograms of VSET, VRESET, and DR for all the functional devices over the wafer (6535 memristors). In addition, the die-to-die distributions of the same switching parameters are also visualized in the wafer map as shown in Fig. 3f–h. Some variations in the essential switching parameters might be mainly attributed to the spatial variation of the bilayer oxide stack. Also, a few dies located around the wafer edge exhibited slightly deviated switching parameters (Supplementary Figs. 24–26). This position-dependent variation might be attributed to the edge defect and fabrication bias, which can become more pronounced around the edges. The slightly increased DR can be explained by the complete RESET process (Supplementary Fig. 12). The seamless operation of all dies over the wafer can be enabled by the synergistic combination of device design and process flow together with our crossbar structure. For example, Al2O3 can suppress the excessive growth of the switching filament, lowering the risk of hard breakdown during operation (Supplementary Fig. 27). This barrier layer can also mitigate the bottom line-to-line disturbance caused by the leakage currents. Another point is to complete the formation of the bilayer oxide stack by ALD instead of typical sputtering systems. There is a possibility that the sputtering method forms porous, cracked, and imperfect stoichiometric oxide layers24,28,48, leading to the requirement of thicker oxides and thermal annealing. Our process method can enable a uniform and thin bilayer stack than before, while regulating the VO profile based on the reactive top Ti layer. This eventually obviates the necessity of the thermal annealing process, allowing it to remain available as an additional option for device optimization. Further, some Ti atoms can penetrate into the TiO2 layer during the top Ti deposition, such that the top Ti electrode was formed with the minimum arriving energy (e.g., low deposition rate) to reduce the local strain. Consequently, this wafer-scale demonstration supports the scalability and reproducibility of our approach for large-scale implementation. For a better understanding, our approach is summarized in terms of several key parameters in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 6), suggesting the possibility of a more scalable passive crossbar platform than existing passive crossbar circuits.

a, b Statistical histograms and the corresponding wafer map of the memristor yield for all dies (i.e., 69 crossbar circuits) over the wafer. Each die represents a passive crossbar circuit. The yield estimation for each die was based on 100 memristors positioned in the same region across all circuits because of the limited package resources. Uniform device yield of 94.71 ± 4.18 % was confirmed over the wafer irrespective of the wafer’s location. c–h Statistical histograms and their corresponding wafer maps of switching parameters VSET (c, f), VRESET (d, g), and DR (e, h) for all the switchable memristors (6535) across all crossbar circuits (69). The VSET, VRESET, and DR were obtained from the same definitions in Fig. 2.

Multibit operation

Analog and multi-level switching characteristics for computing applications were quantitatively evaluated (Fig. 4a–g). The primary approach to implementing multiple conductance states is to systemically control the growth dynamics of the switching filament using a tuning algorithm based on an incremental programming voltage scheme49. Fig. 4a shows the current evolution for several target conductance states (i.e., G = 40 μS, 35 μS, 62 μS, 4 μS, and 15 μS) obtained using the tuning algorithm. The tuning algorithm, also referred to as write-verify algorithms, checks the present G (or I) of the selected device with the VREAD pulse. Then, if the G is lower than the target, VSET pulses are incrementally introduced to the device until it falls within the tuning error range (e.g., <5 %). Conversely, if the G is higher than the target, VRESET pulses are applied incrementally. Note that the tuning error is defined as the relative error, i.e., |(target G – measured G)|/target G × 100%. This programming scheme resembles a common technique used in flash memory. As shown in Fig. 4a, the G was successfully tuned to all the target values (Fig. 4a), confirming the controllability achieved through the programming scheme (details in the caption). Figure 4b shows the consecutive analog switching curve over 106 tuning pulses at W = 80 μs, showing the robust stability of multibit switching (see the inset). Figure 4c confirms the retention property for different 16 states (i.e., 4-bit) for 104 s. All the states obtained by the tuning algorithm were observed to almost maintain over time without overlapping with one another. Note that the maximum coefficient of variation (CV) during the retention test was 2.55 % at the lowest G (black line). All CV values are enumerated in Supplementary Table 2. Further, linearly separable G was also implemented to demonstrate the feasibility of hardware-friendly weight quantization (Fig. 4d–g and Supplementary Fig. 28). Clearly, as shown in Fig. 4d, e, 4 bits (i.e., 16 states) are observed with an interval of 5 μS for 16 memristors (Fig. 4d) and during 30 consecutive cycles for one memristor (Fig. 4e). Additional results with different G intervals are presented in Supplementary Fig. 28. A larger number of states is also available, including 5 bits (32 states) and 6 bits (64 states), as shown in Fig. 4f, g. Such multibit switching can be enabled with various other programming pulse schemes as well. However, although the tuning algorithm may require a relatively large time consumption (discussed in Supplementary Note 8), it enables precise control of memristors to achieve any target G, significantly mitigating abrupt and nonlinear G change typically observed in filamentary switching memristors. Hence, this approach can facilitate ex situ training and efficient inference tasks in large-scale implementation. To demonstrate key computational primitives for the aforementioned ex situ and inference tasks using our passive crossbar circuit, we have performed a vector(v)-matrix(g) multiplication (VMM) for several fashion item images (shoes, t-shirts, and trousers). The main aim in this task is to perform a dot product v∙g after encoding the images into the proposed crossbar circuit based on the tuning algorithm, where v and g correspond to voltage and conductance. As shown in Fig. 4h, i, each pixel for the three fashion item images (28 × 28 gray-scale pixels, Fig. 4h) are encoded into the 28 × 28 subarray (yellow dotted line) as G by using the tuning algorithm (Fig. 4i). Hence, G values naturally become elements of g (i.e., g∈ℝ28×28, then v∈ℝ28). A half-biasing scheme was utilized to alleviate disturbance in half-selected memristors during the encoding process50. For better encoding reliability, memristors that deviated from the tuning error were re-programmed into the target through a few rounds (Supplementary Note 8). The encoded g for the three images is individually visualized as shown in Fig. 4j. The purple squares indicate tuning failure during the encoding process (i.e., DR < 3). The average relative errors between the target and measured G were 2.62 ± 1.44 %, 2.59 ± 1.39 %, and 2.53 ± 1.49 % for shoes, t-shirts, and trousers, respectively. Note that the tuning failure devices were excluded from the error estimation. By considering v as a densely packed vector of VREAD (i.e., v∈{0.2 V, 0.2 V,..., 0.2 V}), VMM was physically computed to obtain a current vector I (I ∈ℝ28), expressed as Ij = \({\sum}_{j}{{v}_{i}g}_{i,j}\); i and j indicate row and column (Fig. 4k). The experimental VMM for each column (red) was almost identical to the estimated VMM based on the current sum of each memristor at the corresponding column (blue). The average relative errors between the two results were 0.92 ± 0.62 %, 1.01 ± 0.65 %, and 0.99 ± 0.69 % for shoes, t-shirts, and trousers, respectively. These results demonstrate a key aspect of ex situ training and inference (i.e., the encoding and VMM operation), which can be utilized to accelerate diverse computing applications. The detailed VMM measurement processes are provided in the Method section. Additional discussions on potential approaches to accelerating the tuning algorithm for future in-situ training are presented in Supplementary Note 8. Note that a higher nonlinearity and larger DR value are generally required for better selectivity, particularly considering the symmetric I–V curve and relatively small DR (<~100). Nevertheless, our passive crossbar circuit is random-accessible for the targeted memristor due to our co-design approach and measurement scheme (Supplementary Fig. 29, Supplementary Note 9, and Method section). The crosstalk in the crossbar circuit and relevant operating schemes are further discussed in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 29 and Supplementary Note 9).

a Plot of the current evolution for the memristor with the tuning algorithm. The top panel shows the programming pulses corresponding to 160 consecutive VSET and VRESET pulses at a fixed W = 80 μs. For the target G, the amplitude started from ±0.4 V and then was incrementally increased by 60 mV. When the current G approached the target, the incremental amplitude became smaller to 24 mV to perform fine tuning. To verify the current G after programming, VREAD was used with 0.2 V for 1 ms. Tuning error was set to be <5%. b Reproducibility of consecutive analog and multibit switching characteristics during 106 programming pulses. The pulse endurance test was performed based on the tuning algorithm with target ION = 10−5 A and IOFF = 2 × 10−6 A. The tuning error was set to be <5 %. The inset shows a magnified plot of the analog switching curve. c Retention capability of 16 G values with an interval of 1.75 μA (i.e., 4 bits) for 104 s. All G values were repetitively read at VREAD = 0.2 for 1 ms with Δt = 1 s. d, e Plots of 4-bit operations with respect to 16 memristors (d) and 30 cycles (e). The 16 distinguishable states were also clearly observed at VREAD in I–V curves (red dotted line in d), corresponding to 16 G values (the inset in d). The error bars in e are the standard deviation. f, g Plots of 5- (f) and 6-bit operations (g) with smaller tuning errors of 3 % and 1 %. The same VREAD was used. h Examples of fashion-item images (Shoes, T-shirt, and Trousers). Each image consists of 28 × 28 gray-scale pixels. i A 28 × 28 sub-array to be encoded by the three images (yellow dotted box) based on the tuning algorithm with W = 80 μs. The scale bar for (i) is 50 μm. j Resultant conductance maps visualizing the encoding results for the three fashion-item images. The purple box indicates the tuning failure that is typically caused by low DR (<3). k Operation results for estimated (blue bar) and experimental VMM (red dot). The small difference between the two results suggests the successful VMM operation in combination with the precise encoding using the tuning algorithm.

SNN application

As a prospective application, a recognition task for fashion MNIST benchmark was conducted using an SNN31,32,33,34,51. Although SNNs hold a substantial promise as a next-generation network, their applicability has yet to be restricted by lower accuracy than typical artificial neural networks (ANNs). This is mainly because nondifferentiable spiking dynamics make it hard to directly employ gradient-based learning rules such as backpropagation. One feasible solution is to utilize the notion of surrogate gradient51,52. Herein, the spiking dynamics are approximated to continuous and differentiable functions only during the learning process, enabling the error to propagate backward and perform local weight updates according to spiking activity. Hence, this approach can preserve the core principle of SNNs while enhancing the practical aspects, such as accuracy. For these reasons, our proof-of-principle demo focuses on the implementation of a practical SNN with a surrogate gradient learning rule based on our scalable passive crossbar circuits. Additional discussion on SNNs with surrogate gradient learning are presented in Supplementary Note 10 and 11.

Figure 5a shows a few examples of the ten fashion-item dataset53. Each fashion item includes 60,000 learning images and 10,000 inference images consisting of 28 × 28 grayscale pixels. Figure 5b shows a multilayered SNN configuration comprising 784 input neurons (purple), 800 hidden neurons (green), and 10 output neurons (blue) that are fully connected with synapses (yellow). Each image is transformed into spikes based on latency encoding to reduce the number of spikes and thus the overall neural activity. All the synaptic weights are quantized into different discrete levels ranging from 1 bit to 6 bits, which can be beneficial for memristor control and hardware-friendly computing54,55. Similarly, hidden and output neurons are discrete leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons with a discrete-time domain, which could make neurons and peripheral circuits simpler than continuous-time operation56,57. During learning, spikes are approximated using an exponential function, and then weights are updated with the Adam optimizer. The shortest latency spike in the output layer indicates the inference result; for example, the network infers the input as an ankle boot in Fig. 5a. Detailed learning and inference processes are provided in the Method section.

a Examples of 10 fashion-item images. Each fashion item has 6000 learning and 1000 inference images. The MIT License (MIT) Copyright © 2017 Zalando SE, https://tech.zalando.com. b Schematic of a multilayered SNN consisting of input (purple circles), hidden (green circles), and output neurons (blue circles) fully connected by synapses (yellow lines). This diagram illustrates the recognition process when an ankle boot image is fed to the network. c Plots of the recognition accuracy as a function of the bit number from 1 bit to 6 bits. There is no noticeable difference between the 4–6 bits (blue, sky blue, and brown) and the software baseline (gray). d Histogram plots of the final accuracy for the software baseline (SB) (gray) and 4-bit weights (blue) at 15 epochs. The small difference (Δ < 0.75 %) was observed. e Contour profile of the average recognition accuracy as a function of device yield and noise at 15 epochs. The black circle indicates the average accuracy obtained from the experimental yield and noise results of the fabricated crossbar circuits (white circle).

Figure 5c shows the simulation results for recognizing the above ten types of fashion items with the weight quantization-aware learning as a function of the bit number. The recognition accuracy is observed to significantly increase as the bit number increases from 1 bit to 6 bits. Interestingly, the accuracy does not significantly improve beyond the 4-bit quantized weights, even with an increase in the number of epochs, showing only a marginal difference of within 0.75 % compared to 5- and 6-bit weights and the software baseline without quantization (Fig. 5d). This finding implies that the 4-bit weights are sufficient for performing the fashion-item recognition task with SNNs, which is lowered than the 6-bit weights typically required for ANNs as the minimum bit number for learning process. This might be attributed to the inherently sparse nature and flow in SNNs compared to the exact calculation in ANNs. Based on this implication, we further examined and simulated the undesired effect of device yield and conductance noise on the accuracy of the ex situ trained SNN (Fig. 5e). Note that the accuracy was statistically estimated based on 10 trials (Supplementary Fig. 30). As shown in Fig. 5e, the average accuracy is significantly degraded as yield decreases and noise increases. However, the accuracy remains resilient despite suboptimal yield and non-negligible noise. This may be explained by the spiking dynamics that can enhance the robustness to noise and improve their suitability for switching uncertainty. Based on our experimental results (Figs. 3b and 4c), the ex situ trained network is observed to achieve an average recognition accuracy of 85.12 %, which is comparable to the software baseline (86.26%). As a result, we demonstrate the successful recognition of fashion items with a multilayered SNN, providing a route for the practical applicability of the proposed passive crossbar circuits.

Discussion

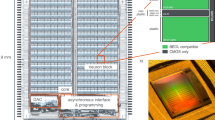

Our approach offers an efficient platform for scaling up integration complexity in neuromorphic hardware systems while preserving the inherent fabrication advantages of memristors. A prospective next step for our technology would be associated with the back-end-of-the-line (BEOL) 3D-integrated crossbar circuits on CMOS chips (Supplementary Fig. 31). Because the CMOS circuits can deliver exceptional control and logic functions across multiple memristive passive crossbar circuits15,16, the memristor-CMOS hybrid chip would allow for diverse computing applications with high integration density. In fact, our approach has been directly applied to the BEOL 3D integration onto a specially designed and tape-out CMOS chip based on 180 nm process (Supplementary Fig. 31). Herein, multiple passive crossbar circuits (comprising up to ~1 M memristors) can be vertically integrated on the CMOS chip without any modification to the fabrication scheme, demonstrating the promising potential for high integration complexity. Further, the subsequent phase of work would focus on developing a 3D-stackable crossbar structure that is ultimately essential for the seamless implementation of brain-scale computing. A laterally stacked and multilayered crossbar circuit with overlapping footprints (i.e., 4F2/n) may be feasible. A possible fabrication scheme is suggested and discussed in Supplementary Fig. 32. As a proof of concept, we fabricated and demonstrated a 3D stacked three-layer 3 × 1 × 1 crossbar circuit (Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34 and Note 12). This 3D stacking memristor-CMOS hybrid architecture can continue to increase integration complexity by increasing the density of memristors. This implies that additional functionalities could be incorporated into the hybrid system, even when further development of CMOS technology becomes challenging due to physical and economic limits in the future.

From a wafer-scale fabrication perspective, our demonstration of multiple passive crossbar circuits on a wafer could also be related to an interposer-based integration of dies (chiplets)58,59,60. Such a methodology—small and modular chiplets are packaged together to realize the function of a larger chip‒has gained considerable momentum in recent years. This is mainly because smaller chiplets could achieve better yields with the reduction of overall silicon costs, while enabling mixed process nodes in a large chip. The decreased silicon costs and faster time-to-market can render the chiplet approach highly efficient and scalable. For example, at advanced technology 7-nm nodes, the chiplet-based designs have shown substantial cost efficiencies58. For advanced neuromorphic computing, the chiplet approach could further optimize the die yield of our wafer-scale fabrication and flexibly add up and update functionalities according to diverse neuromorphic hardware demand. With these considerations, we can envision that our wafer-scale fabrication could be extended and adapted into the chiplet approach by tailoring and updating various technologies into integrated chip design, without changing reliable legacy nodes (e.g., IO and bus chiplets).

Meanwhile, 1T1M active crossbar circuits have showcased their potential for wafer-scale integration and computing applications thanks to the controllability enhanced by 1T per memristor. However, this approach would encounter inherent limitations in scaling up to achieve brain-scale cognitive functions applied to solve real-world problems. This challenge is mainly because the area cost increases with the number and dimension of crossbar circuits due to the active node. For example, Hu et al. reported a 128 × 64 1T1M crossbar circuit capable of VMM in one step; however, the cell size was bulky (>2000 μm2)10. The 1T1M configuration typically has a cell layout of ≥8F2, which fundamentally limits the potential for further increase in integration density. Although a further compact 1T2M design named as H3 cell has been proposed, it is still 6F2 and has not been fully validated with the experimental demonstration11. Furthermore, several three-terminal types of memristors that combine 1T and 1M into a single device have been suggested. However, in many cases, they range from 6F2 to 30F261. With these regards, we believe that passively integrated crossbar circuits (0T1M or 1M) also present a promising direction, particularly for achieving a highly dense and brain-scale neuromorphic hardware system. Because passive crossbar circuits feature a simple structure with the smallest 4F2 footprint, they allow for a higher integration density compared to active crossbar circuits, where 1 T can affect the cell downscaling. In addition, the upscaling based on 3D-integrated multilayered architecture is more feasible with passive circuits, as stacking 1 T1M circuits can lead to more fabrication complexity. Further, considering the number of 1T per 1M increases with the integration scale, the passive circuits can offer lower energy consumption and fabrication cost by avoiding the use of active 1T node62. Although the process maturity of the passive circuit remains elusive, we believe that the passive crossbar circuit still stands effective for the implementation of brain-scale structure (e.g., 1015 synapses) due to its structural simplicity and 3D scalability. In this regard, we think that several groups have continued working on the development of passive crossbar circuits to fully leverage the benefits of memristors, such as density and function, as summarized in Supplementary Table 1. However, as shown in Supplementary Table 1, scaling up integration with passive circuits is more challenging than with active circuits. This is primarily because the absence of the 1T makes it more difficult to control the switching filament and leakage current during operation, which in turn reduces device yield and reliability. Hence, we believe that developing a scalable passive crossbar circuit for brain-scale computing is ultimately essential to fully leverage the capability of memristor and its based computing. It is also worth noting that a one-selector-one-memristor (1S1M) configuration can be considered a middle-ground option in terms of density and regulation of sneak currents. However, several challenges, such as voltage/current range matching, half-selected disturbance, more complex fabrication processes, and higher cost, remain obstacles to scaling up, which are further discussed in Supplementary Notes 6 and 9.

Lastly, further advancements should also be required at the device level. For example, although the tuning algorithm can effectively regulate both device and cycle variations, it is likely to increase the energy and time consumed during the tuning process as the number and dimension of crossbar circuits increase. In our device structure, forming-free behavior appears when using 4 nm-thick TiO2 and 1.8 nm-thick Al2O3, which reduces switching uncertainty (Supplementary Fig. 35). This may be attributed to the shortened distance of VO migration in as-fabricated devices. As a result, at the same fabrication scheme, the variations can be lowered even further for efficient computing. This reduced variation can also alleviate the half-selection issue inherent in passive crossbar structures, ensuring more reliable and efficient operation. Other switching parameters, including device yield, write and operating currents, and wafer-level scalability, also require further enhancement, along with the development of algorithmic approaches capable of mitigating undesired device behaviors.

Our fabrication scheme is based on top-down processes similar to those used in silicon foundries. However, the materials used in our device are not yet standard in CMOS fabrication environments. Nonetheless, this incompatibility may be addressed in the future if our device platform shows promising commercial potential and foundries consider adapting their fabrication lines. Moreover, this study focuses on the passive crossbar platform as the computing core. To interact with future users or other systems, the passive cores are inevitably combined with active electronics and circuitries, requiring further development toward a fully integrated system. Although our demonstration here is still at the lab scale, the device structure, fabrication scheme, and underlying principles could be extended into large-scale production. Our work presents a promising pathway toward wafer-scale fabrication and high integration complexity, paving the way for brain-scale computing systems.

Methods

Scalable crossbar circuit fabrication

The scalable memristive crossbar circuits were fabricated on a 285 nm-thick SiO2/p++-Si wafer. First, the substrates were prepared using a conventional cleaning process with acetone, isopropyl alcohol, and deionized water via ultrasonication for 3 min each. To form bottom electrode lines, photoresist (AZ4110) was spin-coated with 4000 rpm for 30 s, followed by a prebaking process at 95 °C for 60 s on a hot plate. Patterning was performed using maskless lithography (Heidelberg MLA150) with an exposure dose of 240 mJ cm−2 and defocus of 5. The bottom electrode patterns were developed by using AZ400K:DI 1:4 developer for 55 s. Then, back-filing process was conducted using the following steps: an inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching (Panasonic E626I) using CHF3 plasma for 25 nm, a deposition of Pt (22 nm)/Ti (3 nm) via e-beam evaporator with a deposition rate of 1 Å s−1, and a lift-off process using AZ NMP solution at 80 °C for >5 h. After O2 plasma treatment for 30 s, the bilayer oxide stack, TiO2 (8 nm)/Al2O3 (1.5 nm), was subsequently formed by ALD based on thermal water reaction. The top electrode lines, Pt (80 nm)/Ti (15 nm), were then patterned and deposited perpendicularly to the bottom electrode lines using the same lithography process and e-beam evaporation at deposition rates of 1 Å/s and 0.5 Å s−1, respectively. For the wirebonding and packaging process, the ends of the bottom electrodes and the bilayer oxide stack outside the crossbar lines were opened using ICP etching with CHF3. After that, electrode pads of Au (400 nm)/Ti (40 nm) were formed using the same patterning and deposition processes. With these process flows, the fabrication of passive crossbar circuits was completed.

Electrical characterization

The passive crossbar circuit was wire-bonded and mounted onto a custom-printed circuit board (PCB) specially designed for testing and application demonstrations. The custom PCB was interfaced with Keysight instrumentation and operated via a personal computer. All the electrical measurements, such as I–V curve, endurance, retention, and pulse operation, were conducted by using a Keysight B1500A semiconductor parameter analyzer, while input/output connections to the crossbar array were managed through the Keysight 34980A switching matrix. The parameter analyzer and switching matrix were communicated with the computer via general-purpose interface buses (GPIB) and universal serial buses (USB) with a customized C + + code.

For the forming process, the selected row line (i.e., the top electrode) was biased, while the selected column line (i.e., the bottom electrode)24,50. All other unselected lines were floated. Then, we electroformed memristors in the direction from the center to the edge, which can reduce the risk of damaging the already-formed memristors when electroforming other devices. In addition, the electroformed memristors were set to be OFF state to minimize the leakage current during the forming process. Based on this method, the representative 32 × 32 passive crossbar circuit was electroformed as shown in Fig. 2. In addition, this forming method was also applied to the spatial analysis over a 4-inch wafer as shown in Fig. 3. Herein, only 100 selected memristors at each die were intentionally electroformed to reduce the leakage current. Note that non-electroformed devices were observed to exhibit a lower conductance value than devices in the OFF state (Supplementary Fig. 7).

For the programming operation, we used a typical half-biasing scheme (i.e., V/2 scheme) to select and program a memristor of the passive crossbar circuit, where the selected row (i.e, the top electrode) and column (i.e., the bottom electrode) were biased at V/2 and −V/2, respectively24,50. This programming scheme can alleviate the disturbance in half-selected memristors that share the same row and column line as the selected memristor. For the reading operation, we used the rest-bias scheme. With these methods, all the electrical characteristics, including the forming process, statistical evaluation, and multibit operation, were investigated and evaluated. The detailed operations and relevant discussions are provided in Supplementary Fig. 29 and Supplementary Note 9.

Encoding process and dot product

To perform image encoding (corresponding to ex situ training), the tuning algorithm was employed. The write process was executed based on the half-biasing scheme to alleviate half-selected device issues. VSET and VRESET pulses at a fixed W = 80 μs were introduced with an incremental amplitude of 60 mV. This increment was further reduced to 24 mV for the fine-tuning as the present G approached the target. The maximum amplitude of the programming voltage pulse at W = 80 μs was generally 3 V, but a slightly higher amplitude was also carefully used by considering the state of the device and its neighboring devices. This enabled a larger DR by completely resetting the devices. The W value was decided to ensure similar tuning behaviors across all the memristors in the fabricated crossbar circuit. For the verify process, VREAD pulse was 0.2 V with 1 ms with the ground-biasing scheme that grounds unselected lines to minimize sneak currents. The reading scheme could enhance tuning precision. For VMM operation (corresponding to inference), experimental VMM was sequentially carried out column by column, thereby reducing the complexity to O(n) instead of O(n2), where n represents the dimension of crossbar circuits. This operating scheme can also be utilized to exclude a few tuning-failure devices with an emphasis on precise conductance tuning for inference operations. Note that the complexity could be further reduced to O(1) if the VMM were performed across all columns simultaneously. However, our focus here is on showing the utility of the tuning algorithm for image encoding and its based dot product, implying the applicability of ex situ training (i.e., encoding operation) and inference (i.e., VMM operation) to the proposed crossbar circuit.

Fashion-item image recognition task

We designed a multilayered SNN consisting of 784 input neurons, 800 hidden neurons, and 10 output neurons fully connected with synapses. Each class was assigned to each output neuron. For encoding the fashion-item dataset (comprising 28 × 28 grayscale pixels) into spikes, simple latency encoding was utilized in the input neurons as follows:

where ten and x represent the timing of spike generation and the normalized pixel intensity, respectively. The forward propagation was then performed based on LIF neurons with a batch size of 128. The neuron membrane potential V(t) is simply expressed as:

where w, τm, τs, tsc, and H are synaptic weights, membrane time constant, synaptic time constant, temporal scale, and Heaviside function. When the V(t) exceeded a threshold Vth, an output spike was generated with the spiking timing (tout). Once the forward pass was complete, tout values from the output neurons were applied to an exponential function (zo = etout). Then, the delta at output (δo) was estimated using the errors between the outputs and targets according to:

where Aho = 1 when tout,h < tout,o; otherwise Aho = 0

f, y, who, tout,h, and tout,o are softmax, target values, weights between hidden and output neurons, tout for hidden neurons, and tout for output neurons, respectively. Here, the function g was defined as:

The delta for the hidden layer (δh) can be similarly obtained. Based on the δo and δh, the weight update was performed using Adam optimizer:

The constant β1, β2, and ε were 0.9, 0.9, and 10−8, respectively. The learning rate (η) was decayed over epoch following as:

ηstart, ηend, and total epoch are 10−3, 10−6, and 15. During the operation, weights were scaled and quantized into discrete state numbers (e.g., wQ = [0,15] for 4 bits), which were then encoded into the memristive crossbar circuits based on the tuning algorithm (i.e., ex situ training). For example, the memristor’s G values were quantized into discrete conductance levels, GQ:

If wQ corresponds to the i = 1, the tuning algorithm adjusted the present G to GQ(1) with a tuning error of <1%. Finally, to consider device yield and noise, the concepts of a randomly generated mask and the coefficient of variation were utilized for the unbiased comparison with the ideal case.

Data availability

All data supplementary to the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information, or from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

All codes used for the simulation are available within the article and its Supplementary Information, or from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Mead, C. Neuromorphic electronic systems. Proc. IEEE 78, 1629–1636 (1990).

Khan, M. M. et al. SpiNNaker: mapping neural networks onto a massively-parallel chip multiprocessor. In 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence) 2849–2856 (IEEE, 2008).

Schemmel, J., Fieres, J. & Meier, K. Wafer-scale integration of analog neural networks. In 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence) 431–438 (IEEE, 2008).

Merolla, P. A. et al. A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 345, 668–673 (2014).

Pei, J. et al. Towards artificial general intelligence with hybrid Tianjic chip architecture. Nature 572, 106–111 (2019).

Ham, D., Park, H., Hwang, S. & Kim, K. Neuromorphic electronics based on copying and pasting the brain. Nat. Electron. 4, 635–644 (2021).

Pehle, C. et al. The BrainScaleS-2 accelerated neuromorphic system with hybrid plasticity. Front. Neurosci. 16, 795876 (2022).

Raichle, M. E. & Mintun, M. A. Brain work and brain imaging. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29, 449–476 (2006).

Neves, G., Cooke, S. F. & Bliss, T. V. Synaptic plasticity, memory and the hippocampus: a neural network approach to causality. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 65–75 (2008).

Hu, M. et al. Memristor-based analog computation and neural network classification with a dot product engine. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705914 (2018).

Lastras-Montano, M. A. & Cheng, K.-T. Resistive random-access memory based on ratioed memristors. Nat. Electron. 1, 466–472 (2018).

Xue, C.-X. et al. A 22 nm 2Mb ReRAM compute-in-memory macro with 121-28TOPS/W for multibit MAC computing for tiny AI edge devices. In 2020 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC) 244–246 (IEEE, 2020).

Yao, P. et al. Fully hardware-implemented memristor convolutional neural network. Nature 577, 641–646 (2020).

Wan, W. et al. A compute-in-memory chip based on resistive random-access memory. Nature 608, 504–512 (2022).

Rao, M. et al. Thousands of conductance levels in memristors integrated on CMOS. Nature 615, 823–829 (2023).

Zhu, K. et al. Hybrid 2D–CMOS microchips for memristive applications. Nature 618, 57–62 (2023).

Song, W. et al. Programming memristor arrays with arbitrarily high precision for analog computing. Science 383, 903–910 (2024).

Wen, T.-H. et al. A 22 nm 16Mb floating-point ReRAM compute-in-memory macro with 31.2 TFLOPS/W for AI edge devices. In: 2024 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC) 580–582 (IEEE, 2024).

Adam, G. C. et al. 3-D memristor crossbars for analog and neuromorphic computing applications. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 64, 312–318 (2016).

Zhang, R. et al. Nanoscale diffusive memristor crossbars as physical unclonable functions. Nanoscale 10, 2721–2726 (2018).

Zidan, M. A. et al. A general memristor-based partial differential equation solver. Nat. Electron. 1, 411–420 (2018).

Cai, F. et al. A fully integrated reprogrammable memristor–CMOS system for efficient multiply–accumulate operations. Nat. Electron. 2, 290–299 (2019).

Yeon, H. et al. Alloying conducting channels for reliable neuromorphic computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 574–579 (2020).

Kim, H., Mahmoodi, M., Nili, H. & Strukov, D. B. 4K-memristor analog-grade passive crossbar circuit. Nat. Commun. 12, 5198 (2021).

Jang, J. et al. A learning-rate modulable and reliable TiOx memristor array for robust, fast, and accurate neuromorphic computing. Adv. Sci. 9, 2201117 (2022).

Cho, H. et al. Real-time finger motion recognition using skin-conformable electronics. Nat. Electron. 6, 619–629 (2023).

Choi, S. et al. 3D-integrated multilayered physical reservoir array for learning and forecasting time-series information. Nat. Commun. 15, 2044 (2024).

Park, J. et al. Multi-level, forming and filament free, bulk switching trilayer RRAM for neuromorphic computing at the edge. Nat. Commun. 15, 3492 (2024).

So, H., Ji, H., Kim, S. & Kim, S. Sophisticated conductance control and multiple synapse functions in TiO2-based multistack-layer crossbar array memristor for high-performance neuromorphic systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2405544 (2024).

Jeon, K. et al. Purely self-rectifying memristor-based passive crossbar array for artificial neural network accelerators. Nat. Commun. 15, 129 (2024).

Zidan, M. A., Strachan, J. P. & Lu, W. D. The future of electronics based on memristive systems. Nat. Electron. 1, 22–29 (2018).

Xia, Q. & Yang, J. J. Memristive crossbar arrays for brain-inspired computing. Nat. Mater. 18, 309–323 (2019).

Choi, S., Yang, J. & Wang, G. Emerging memristive artificial synapses and neurons for energy-efficient neuromorphic computing. Adv. Mater. 32, 2004659 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Resistive switching materials for information processing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 173–195 (2020).

Jeong, Y., Zidan, M. A. & Lu, W. D. Parasitic effect analysis in memristor-array-based neuromorphic systems. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 17, 184–193 (2017).

Stathopoulos, S. et al. Multibit memory operation of metal-oxide bi-layer memristors. Sci. Rep. 7, 17532 (2017).

Huh, W. et al. Synaptic barristor based on phase-engineered 2D heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801447 (2018).

Yoon, J. H. et al. A low-current and analog memristor with Ru as mobile species. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904599 (2020).

Chen, S. & Valov, I. Design of materials configuration for optimizing redox-based resistive switching memories. Adv. Mater. 34, 2105022 (2022).

Schemmel, J. et al. A wafer-scale neuromorphic hardware system for large-scale neural modeling. In 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 1947–1950 (IEEE, 2010).

Chen, S. et al. Wafer-scale integration of two-dimensional materials in high-density memristive crossbar arrays for artificial neural networks. Nat. Electron. 3, 638–645 (2020).

Tang, B. et al. Wafer-scale solution-processed 2D material analog resistive memory array for memory-based computing. Nat. Commun. 13, 3037 (2022).

Renaud, S., Tomas, J., Bornat, Y., Daouzli, A. & Saïghi, S. Neuromimetic ICs with analog cores: an alternative for simulating spiking neural networks. In 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 3355–3358 (IEEE, 2007).

Syrenova, S., Wadell, C. & Langhammer, C. Shrinking-hole colloidal lithography: self-aligned nanofabrication of complex plasmonic nanoantennas. Nano Lett. 14, 2655–2663 (2014).

Chen, H., Zhang, Q. & Chou, S. Y. Patterning of light-extraction nanostructures on sapphire substrates using nanoimprint and ICP etching with different masking materials. Nanotechnology 26, 085302 (2015).

Osipov, A. A. et al. OES diagnostics as a universal technique to control the Si etching structures profile in ICP. Sci. Rep. 12, 5287 (2022).

Funck, C. & Menzel, S. Comprehensive model of electron conduction in oxide-based memristive devices. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 3674–3692 (2021).

Yoon, J., Ji, Y., Lee, S. K., Hyon, J. & Tour, J. M. Low-temperature-processed SiOx one diode–one resistor crossbar array and its flexible memory application. Adv. Electro Mater. 4, 1700665 (2018).

Alibart, F., Gao, L., Hoskins, B. D. & Strukov, D. B. High precision tuning of state for memristive devices by adaptable variation-tolerant algorithm. Nanotechnology 23, 075201 (2012).

Prezioso, M. et al. Training and operation of an integrated neuromorphic network based on metal-oxide memristors. Nature 521, 61–64 (2015).

Eshraghian, J. K. et al. Training spiking neural networks using lessons from deep learning. Proc. IEEE 111, 1016–1054 (2023).

Neftci, E. O., Mostafa, H. & Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks: Bringing the power of gradient-based optimization to spiking neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 36, 51–63 (2019).

Xiao, H., Rasul, K. & Vollgraf, R. Fashion-mnist: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. Preprint at arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07747 (2017).

Sulaiman, M. B. G., Juang, K.-C. & Lu, C.-C. Weight quantization in spiking neural network for hardware implementation. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan) 1–2 (IEEE, 2020).

Wei, W. et al. Q-snns: quantized spiking neural networks. In Proc the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM-ACM) 8441–8450 (ACM, 2024).

Zhang, G. et al. A low-cost and high-speed hardware implementation of spiking neural network. Neurocomputing 382, 106–115 (2020).

Ali, A. H., Navardi, M. & Mohsenin, T. Energy-aware FPGA implementation of spiking neural network with LIF neurons. Preprint at arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.01628 (2024).

Naffziger, S. et al. Pioneering chiplet technology and design for the amd epyc™ and ryzen™ processor families: industrial product. In 2021 ACM/IEEE 48th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA) 57–70 (IEEE, 2021).

Ma, X., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Cai, X. & Han, Y. Survey on chiplets: interface, interconnect and integration methodology. CCF Trans. Hpc. 4, 43–52 (2022).

Shan, G. et al. Architecture of computing system based on chiplet. Micromachines 13, 205 (2022).

Xiao, Y. et al. Recent progress in neuromorphic computing from memristive devices to neuromorphic chips. Adv. Devices Instrum. 5, 0044 (2024).

Aguirre, F. et al. Hardware implementation of memristor-based artificial neural networks. Nat. Commun. 15, 1974 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NSF EFRI grant #2318152, ONR grant #N00014-22-1-2842, the MOTIE (Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy) in Korea under Human Resource Development Program for Industrial Innovation (Global) (P0017311) supervised by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT), and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2024-00412357).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. conceived the research and wrote the manuscript using inputs from all the authors. S.C. performed experiments, analyses, and simulations. S.S.B., T.B. and D.K. assisted with measurements. D.B.S. oversaw the project and led the efforts toward completion with S.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Regina Dittmann, who co-reviewed with Stefan Wiefels, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, S., Bezugam, S.S., Bhattacharya, T. et al. Wafer-scale fabrication of memristive passive crossbar circuits for brain-scale neuromorphic computing. Nat Commun 16, 8757 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63831-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63831-2