Abstract

Deterministic energy transition planning risks uninformed decisions. Yet, the challenge of high-dimensional uncertainty–encompassing various technological, economic, social, and climatic factors–often leads to a deterministic treatment or simplification of uncertainties in planning. Here, we propose a computationally efficient framework that leverages surrogate-based sensitivity analysis to identify the key uncertainty sources driving the cost of different energy transition scenarios. We applied the proposed approach to Puerto Rico as a hurricane-prone power system that lacks efficient management. We find that changes in the frequency of hurricanes and organizational inefficiency are the two primary sources of uncertainty determining the system’s total expected cost. When examining operational costs, different transition scenarios demonstrate unique key uncertainty sources. For example, the price of biofuel would mainly drive the operational cost when transitioning to a fully renewable power system. These findings can help planners by allowing them to focus on a narrower set of uncertainties in planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the primary drivers of climate change is the power sector, which produces around 40% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions1,2,3,4. To mitigate climate change, it is crucial to transition the power sector away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources5. But long-term planning for decarbonizing the power system is made challenging by the many sources of uncertainty affecting future system performance, including but not limited to institutional, social, technological, economic, and climate change uncertainties6,7,8,9.

Considering the challenges of incorporating uncertainty in the analysis of power systems, many studies focusing on power systems overlook existing uncertainties. Such studies adopt a deterministic approach10,11,12,13,14, which can lead to unpreparedness for unforeseen scenarios and costly over- or under-designs. Even when uncertainty is considered, studies may account for one source of uncertainty. For instance, the impacts of climate change uncertainty on the vulnerability and resilience of power systems8,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 and the projections of energy demand22,23,24 have been examined. Few studies have investigated the effects of economic25 or technological26,27,28,29,30,31,32 sources of uncertainty. When it comes to long-term planning of power systems, limited studies have considered any source of uncertainty33,34,35,36,37,38. This has led to a significant gap in the literature: no study has incorporated various available climate change, technological, social, and economic uncertainties within power system planning.

This gap mainly arises from the high dimensionality and the complex nature of uncertainties inherent in power systems39,40. Even preparing a comprehensive list of uncertainties that pertain to the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources can be challenging, let alone accounting for them in (transition) planning. To alleviate this, we aim to understand the key sources of uncertainty that must be accounted for in energy transition system planning. Toward this, we account for a broad set of uncertainties, for each of which we have collected historical data and potential future projections. These uncertainties are divided into two main types: epistemic and aleatoric. Epistemic uncertainties, arising from incomplete knowledge or understanding, include variations in projections for energy prices, capacity expenditures, operation and maintenance expenses, population, electricity demand, shifts in frequency and intensity of hurricanes due to climate change41, and organizational inefficiency, which refers to the delays and additional costs caused by poor coordination and management, miscommunications, and sub-optimal resource allocation. Aleatoric uncertainties encapsulate naturally random variations in weather conditions, hurricane occurrence, and damage caused by hurricanes.

We integrate these uncertainties through a hierarchical sampling approach, and leverage surrogate development and sensitivity analysis to identify the most significant sources of epistemic uncertainty in the system. To achieve this, we employ a three-stage analytical framework that integrates a nested Monte Carlo (MC) simulation with surrogate-based sensitivity analysis. This framework is designed to first establish a fixed system design and then identify the key epistemic uncertainties driving the uncertainty in the system’s cost. Specifically, in stage 1, we establish a cost-optimal energy system for a given transition scenario using a fully deterministic optimization where all uncertain parameters are set to their median projections. This approach is chosen to mirror common long-range planning practices that rely on ‘most likely’ forecasts. In stage 2, we use a hierarchical, nested Monte Carlo simulation to perform probabilistic cost analysis for the design optimized under the deterministic treatment of uncertainties. This structure is crucial for separating the influence of the two uncertainty types: the outer loop samples the epistemic uncertainties (defining a plausible ‘state of the world’), while for each of these states, an inner loop runs thousands of simulations to calculate expected cost over inherent aleatoric randomness. Finally, in stage 3, we use the resulting input-output pairs of epistemic uncertainties and expected cost to develop a surrogate for computationally fast calculation of expected cost. The surrogate is then used to perform a surrogate-based global sensitivity analysis. This framework allows us to directly address the practical question: which sources of epistemic uncertainty, arising from a lack of knowledge, most significantly drive the uncertainty in the expected cost of the energy transition?

Not only does this study incorporate a comprehensive analysis of both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties in energy system cost evaluations, but it also models and includes organizational inefficiency in such analyses. In energy systems, as in other infrastructure systems, organizational inefficiency frequently leads to extended construction or reconstruction timelines, with expenses often far exceeding initial estimates. Examples of cost overruns driven by inefficiency have been well documented across the globe. Notable cases include the 2014 World Cup projects in Brazil42,43, the Boston Big Dig, Denver International Airport, San Francisco Bay Bridge, and New York’s East Side Access projects in the United States44,45,46,47, the Venice seawalls in Italy48, Berlin Brandenburg Airport in Germany49, and the protracted restoration of Puerto Rico’s energy sector following Hurricane Maria50.

We chose Puerto Rico as a case study to identify which sources of epistemic uncertainty are the key drivers of uncertainty in expected system cost under three distinct transition scenarios: (i) business as usual (BAU), where there is no restriction on sources of electricity generation, (ii) transitioning to a system with fully renewable (FR) generation, and (iii) transitioning to a system with fully decarbonized (FD) generation. The choice of Puerto Rico as a case study is multifaceted. Firstly, it is currently highly dependent on fossil fuels51 but has established in 2019 a legal mandate to transition to renewable resources with the passage of the Puerto Rico Energy Public Policy Act (PREPPA)52,53. Secondly, as a Caribbean island, Puerto Rico is highly susceptible to the effects of climate change on the frequency and intensity of hurricanes54,55,56,57,58. This allows us to investigate the potential impact of climate change uncertainty on hurricane-prone power systems. Lastly, the prolonged restoration time and costly aftermath of Hurricane Maria50 exacerbated by mismanagement59,60,61,62 call for incorporating and evaluating the impact of uncertainty arising from the organizational inefficiency in the cost analysis. With Puerto Rico as the case study, the BAU scenario maintains Puerto Rico’s current power generation strategy, while the FR scenario aligns with the ambitions of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of the United States of America (USA)63 and PREPPA52, which aims to transition entirely to renewable energy sources by 2050, and the FD scenario envisions a shift towards exclusively zero-emission power sources by 2050, resonating with the USA’s Energy Earthshots Initiative64.

To summarize, in this work, we develop a three-stage analytical framework that integrates a nested Monte Carlo simulation with surrogate-based sensitivity analysis to identify the key epistemic uncertainties driving expected energy system costs in long-term planning. The framework incorporates diverse uncertainty sources, including institutional, social, technological, economic, and climate-related uncertainties. Although the case study focuses on Puerto Rico, the proposed framework is generalizable and can be applied to any region of interest for understanding the key sources of uncertainty in energy transition. It must be highlighted that the region-specific details can be easily altered within the framework proposed here. For instance, the target year can be set to 2045 for Sweden and Germany65,66, or 2060 for China67, instead of the default 2050 used here for Puerto Rico. The framework, therefore, can facilitate uncertainty-informed planning that avoids oversimplifications and provides a more accurate representation of the system’s behavior for any region of interest.

Results

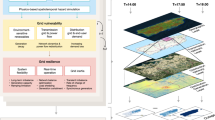

Figure 1 illustrates the three-stage proposed framework. In stage 1, we perform an optimization using a deterministic treatment of uncertainties by setting all uncertain inputs to their median projections. This yields a single, cost-optimal system design for each of the three transition scenarios: BAU, FR, and FD. The optimization is accomplished using TEMOA68, an open-source energy system analysis tool that finds the least-cost technology deployment to meet energy demands over a given time horizon.

Stage 1 (panel i - blue band) runs TEMOA optimization, yielding optimal design under deterministic treatment of uncertainties for each pathway--Business as Usual (BAU), Fully Renewable (FR), and Fully Decarbonized (FD)--over the transition horizon. Stage 2 (panel j - green band) conducts a probabilistic cost analysis for the 2050 optimized design using a nested Monte Carlo scheme. The outer loop (green box) samples epistemic inputs--technology costs (a) fuel price (b) long-term changes in hurricane trends (c, d) demand and tariff projections, and organizational inefficiency. For every outer draw, the inner loop (red box) generates many year-scale aleatoric realizations: daily wind/solar availability (e, f) hurricane frequency and intensity (g), component damage and restoration (h). Each inner sample computes operational, damage, and outage costs whose mean forms the expected annual cost for that epistemic draw. Stage 3 (panel k - orange band) trains a neural-network surrogate on the outer-loop results and applies Sobol global sensitivity analysis to rank the key epistemic uncertainties.

In stage 2, we conduct a probabilistic cost analysis on these fixed system designs. Using a nested Monte Carlo simulation, we evaluate how the systems perform in the year 2050 under the full range of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties. This process allows us to quantify the distribution of the system’s annual expected costs, including day-to-day operation expenses, damage restoration costs after hurricanes, and power outage costs resulting from the economic impact of (prolonged) disrupted power supply. Finally, in stage 3, we use efficient surrogate-based Global Sensitivity Analysis (GSA) to identify the key epistemic uncertainties.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of all uncertainties considered in this study, their classification as epistemic or aleatoric, and their modeling details.

Transition under deterministic treatment of uncertainties

Figure 2a presents the power generation across the BAU, FR, and FD scenarios from 2021 to 2050, under deterministic assumptions69. In the BAU scenario, natural gas usage increases due to its cost-effectiveness, leading to the phasing-out of heavy oil generation and a gradual decline in coal generation. One interesting observation is that even in the BAU scenario, where no explicit mandate or policy enforces a transition to renewable energy sources, the share of generation from renewable sources–primarily wind power–still experiences a significant increase. This growth is largely driven by the declining costs of renewable technologies, making them more economically competitive compared to traditional fossil fuel-based generation. As a result, market forces alone, without regulatory intervention, naturally favor the adoption of renewables. This highlights the role of cost efficiency in accelerating the energy transition.

a Annual electricity generation by source from 2020 to 2050 for the Business as Usual (BAU), Fully Renewable (FR), and Fully Decarbonized (FD) scenarios, showing the decreasing contribution of fossil fuels, and increasing contribution of cleaner technologies. b Corresponding annual CO2 emissions for each scenario, compared with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) 2030 target, illustrating the decaying trends over all three scenarios.

FR and FD scenarios are mandated to align with the goals set forth by PREPPA, aiming for 40% renewable energy by 2030 and 60% by 204052,53. Consequently, these scenarios follow similar transitions until 2040. By 2050, while both FR and FD scenarios utilize similar proportions of hydro, solar, and wind power, they differ in their supplementary generation technologies. The FD scenario uses nuclear energy, a carbon-free technology, to fill the demand gap. In contrast, the FR scenario integrates biofuel, a renewable but not carbon-free generation source, to meet the remaining demand. It can be seen that the FD scenario requires larger battery storage, compared to the FR scenario. This is because nuclear energy is widely known as a baseload technology70 with constrained ramp-up capabilities and rather steady output. On the other hand, biomass offers operational flexibility and can be considered as a balancing technology71,72.

Figure 2b shows the direct impact of the strategies depicted in Fig. 2a on carbon emissions in Puerto Rico from 2020 to 2050. As depicted, all three scenarios follow a downward trend in their emissions due to their increased reliance on cleaner energy sources. Interestingly, the emission reduction in the BAU scenario nearly achieves IRA’s goal of a 40% reduction in greenhouse gases from 2005 levels by 203063 but then levels off and does not meet the PREPPA targets. It can also be seen that FR and FD scenarios follow similar emission trajectories until 2045, as a result of their similar generation strategies. By 2050, the FR scenario will achieve a 90% reduction in CO2 emissions relative to BAU. The FD scenario is projected to achieve total decarbonization, meeting the ambitious goals of the US Department of Energy Earthshots Initiative to decarbonize energy systems entirely by 205064.

Given the deterministically optimized generation mix and grid capacities for each scenario, Fig. 3 presents the expected annual system costs for the year 2050. These costs are calculated by setting all epistemic uncertain parameters to their median projections while averaging over the full range of aleatoric uncertainties, such as varying yearly weather conditions and hurricane occurrences. The total expected cost shown is composed of three main components. Expected operational costs refer to the routine fuel and Operation and Maintenance (O&M) expenditures for the year 2050, and do not include the amortized capital costs from the initial infrastructure investment. Expected damage costs reflect post-hurricane system restoration and are estimated using benchmark methods from the literature, based on median Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) projections for component replacement73,74,75. Lastly, expected power outage costs estimate the economic impacts of service disruption on the community76. Additionally, Fig. 3 illustrates the CO2 reduction levels achieved by each scenario to highlight the trade-off between decarbonization and the associated costs.

Colors and hatches distinguish individual operational, damage-restoration, and power-outage components; black outlines show the three parent cost categories. The narrow bar to the right of each stack shows the residual (black) and avoided (white) shares of CO2 emissions relative to 2020 levels. A detailed breakdown of these cost components, including precise numerical values and a percentage-based view in pie chart format, is provided in Supplementary Note 9.

As observed, the BAU scenario presents the lowest expected total costs, primarily due to the lower cost of conventional fossil fuel generation and the reduced vulnerability of fossil fuel generation plants to intense wind events77,78. As expected, this scenario results in the least CO2 level reductions. Comparing FR and FD scenarios, the FR scenario results in a larger operational cost, despite not being as effective as the FD scenario in reducing expected emission levels. This higher cost is associated with the higher operational and fuel costs of biofuel generation, compared to nuclear generation. It can also be seen that in the FR and FD scenarios, the highest share of operational costs is associated with biofuel and nuclear generation, respectively. In fact, despite the higher costs associated with the utilization of nuclear and biofuel generation, the optimization in both FR and FD scenarios is compelled to include these energy sources in the generation mix to ensure reliability during periods of insufficient generation from wind turbines and solar panels. Subsequent operational cost shares correspond closely with the respective generation capacities outlined in Fig. 2a.

It is also evident that the FR and FD scenarios exhibit significantly higher damage costs compared to the BAU scenario. This outcome is expected, as wind and solar power generation are more susceptible to damage from intense winds. A closer look at the cost distribution reveals that over 47% and 43% of the expected damage costs in the FR and FD scenarios, respectively, are attributed to damages sustained by wind turbines and solar panels. In contrast, the share of damage costs associated with renewable generation in the BAU scenario is less than 12%. This highlights the heightened risks posed by intense winds in the FR and FD scenarios.

Power outage costs remain consistent across scenarios. This is because the power outage cost is mainly determined by damage restoration times of distribution and transmission systems, which are considered to be similar in all scenarios. The large share of power outage cost, followed by damage cost in the total expected cost, emphasizes the importance of grid resilience enhancement policies, especially retrofitting distribution lines. These components are responsible for the prolonged blackouts and hold the biggest share of damage costs in all scenarios. This observation is in line with the lived experience from Hurricane Maria, where 55% of total lines experienced significant structural or equipment damage56,79,80,81.

Probabilistic cost analysis for energy transition

To perform a probabilistic cost analysis under the three transition scenarios, we account for a broad set of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties, outlined in Table 1. As depicted in Fig. 1, this involves evaluating the distribution of the expected cost of the optimal system suggested by TEMOA (designed under deterministic assumptions) amidst uncertainties projected for the year 2050. To do this, we used two nested MC engines. The nested MC framework operates by embedding an internal Monte Carlo engine within an external one. Specifically, the external MC engine first draws realizations of epistemic uncertainties. Then, for each realization of epistemic uncertainties, the internal MC engine samples aleatoric uncertainties to calculate the expected cost for that particular realization. For instance, to generate one external sample, the external MC engine draws one set of realizations from variables such as technology costs, fuel prices, population, demand per capita, changes in electricity tariffs, and organizational inefficiency. These values are then fed into the internal MC engine. Then, the internal engine calculates costs based on this set of realizations of epistemic uncertainties, across 1000 realizations of weather conditions, hurricane occurrences, component damages based on each hurricane’s intensity, and component restoration times based on the extent of damage. Ultimately, the expected costs across these internal samples are computed as the output for that particular realization of epistemic uncertainties.

Figure 4 illustrates the cost distributions for the BAU, FR, and FD scenarios. Interestingly, it can be seen that there is considerable overlap in the distributions of total costs across the three scenarios, which suggests that while in the deterministic scenario, BAU appears as the most cost-effective choice, it’s not definitive. In other words, depending on the future realization of epistemic uncertainties, including the cost of fuel and renewable technology, the FR and FD scenarios could be less costly compared to BAU. Specifically, our analysis of the 5000 epistemic scenarios shows there is a 38% chance of the FR scenario being less costly than BAU, and a 41% chance of the FD scenario being less costly than BAU.

Panel a shows the distributions of total system costs, reflecting combined operational, damage, and outage costs. Panel b depicts operational cost distributions, representing expenses directly associated with electricity generation and system operation. Panel c presents damage cost distributions, which capture the expected costs of infrastructure repair following hurricane-related impacts. Panel d shows outage cost distributions, representing the economic losses caused by power supply interruptions. Distributions in all panels exhibit substantial overlap between scenarios, indicating that under the considered uncertainties, no single pathway guarantees the lowest cost with high confidence.

Concentrating on the operational costs, we observe that the BAU scenario, while maintaining the lowest mean, exhibits the broadest cost distribution, a reflection of the significant uncertainty associated with projected natural gas generation costs (see Supplementary Note 2). On the other hand, the FD scenario has the narrowest distribution among the three scenarios. This is a reflection of a rather narrow projection of uranium prices compared to both biofuel and natural gas prices (see Supplementary Note 2). It must also be noted that, even when solely considering operational costs, the overlap in the cost distributions among the scenarios is considerable. This again highlights the shortcomings of deterministic approaches in cost estimations and long-term planning of the energy transition.

Regarding the damage restoration cost (driven by future changes in hurricane characteristics and the projected CAPEX required to replace damaged components), BAU has the least expected damage cost, followed by the FD and FR scenarios. This is because solar and wind farms are vulnerable to high winds, and these two scenarios rely more heavily on generation from these sources. The similarity between damage restoration costs for the FD and FR scenarios can be explained by their similar share of solar and wind generation (as shown in Fig. 2). The remaining demand in these scenarios is met with biofuel, nuclear power, and battery storage, which are less vulnerable to high wind.

Lastly, regarding the power outage cost, it must be noted that this cost is primarily a function of the extent of damage caused to the transmission and distribution systems, which are the most vulnerable components to hurricanes, as observed previously in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria56,79. Consequently, the power outage cost is rather consistent across the three scenarios. This consistency arises from the fact that the total length of transmission and distribution lines in all three scenarios is considered to be the same.

Global sensitivity analysis for total and operational costs

To understand how the uncertainty in the expected total and operational cost of the system, in 2050, under the three transition scenarios, is attributed to different sources of epistemic uncertainty, we perform a GSA. We use total-order Sobol indices as a metric of sensitivity, which indicates the proportion of the total output variability attributed to a specific input82. Here, we compute total-order Sobol indices for per unit (i.e., $kWh−1) expected total and operational costs (Sobol indices for absolute costs are included in Supplementary Note 11).

Figure 5 shows the results of the GSA. As seen in Fig. 5a, in all transition scenarios, the uncertainty related to changes in hurricane frequency due to climate change emerges as the dominant source of uncertainty for the expected total cost. This observation aligns with the wide distribution of power outage and damage costs (see Fig. 4), and further highlights the critical role of climate change as a primary source of uncertainty in planning for a hurricane-prone power system83. Surprisingly, the factor of organizational inefficiency emerges as the second most dominant uncertainty impacting the total expected cost. Organizational inefficiency can include issues like leadership deficiencies, poor communication or planning, corruption, graft, delays in processing essential documents for contracts, and similar systemic challenges. Here, the inefficiency factor is modeled as a uniform random variable between one and four, which multiplies the restoration cost and time. We selected a uniform distribution based on the principle of maximum entropy, which is preferable in the absence of abundant data for determining the parameters of a probability distribution to avoid any biased assumptions. Moreover, since available inefficiency examples typically relate to construction and not daily operations, our analysis primarily considered the impact of inefficiency on system recovery post-hurricanes, rather than on operational costs. Due to the lack of data for modeling organizational inefficiency, we have replicated the results with different approaches for modeling inefficiency in Supplementary Note 11, all of which consistently identify organizational inefficiency as an influential source of uncertainty.

Panel a shows the Sobol total sensitivity indices for per-unit total system costs. Panel b presents the corresponding indices for per-unit operational costs. In all cases, only a few dominant uncertainties, most notably changes in hurricane frequency and organizational inefficiency for total costs, and key fuel or O&M parameters for operational costs. Abbreviations in the figures are defined as follows: O& M means Operations and Maintenance; CAPEX means Capital Expenditure; NG means Natural Gas; Bio means Biofuel; PV means Photovoltaic; URN235 means Uranium-235.

As for expected operational cost, as illustrated in Fig. 5b, the per unit cost in the BAU scenario is almost solely affected by the price of natural gas, which is responsible for over 98% of the uncertainty in forecasted costs. This is attributed to the scenario’s heavy dependence on natural gas, combined with the significant unpredictability of its future price (see Supplementary Note 2). This also results in a broad operational cost distribution, as observed in Fig. 4. For the FR scenario, the biofuel price emerges as the primary factor influencing the uncertainty of per-unit operational cost. Biofuel generators’ critical role as a balancing generator, given the variability of renewable supply, coupled with its price uncertainty, positions it as the principal source of cost variability. The second most influential source of uncertainty impacting the per-unit operational cost is the O&M cost of wind turbines, which aligns with the large share of generation from wind turbines in the FR scenario. Interestingly, demand parameters (population and demand per capita) are shown to be substantially more important for the operational cost uncertainty in the FR scenario, compared to the BAU scenario. This increase in the sensitivity indices of demand parameters compared to BAU has two main reasons: 1) biofuel’s lower price uncertainty compared to natural gas, along with its smaller generation share, and 2) the high fuel and variable O&M costs (i.e., demand-dependent expenses) of biofuel coupled with the role of biofuel generation in balancing demand and supply (see Supplementary Note 3).

In contrast to the FR and BAU scenarios, the FD scenario lacks a predominant driver of operational cost uncertainty for per-unit operational costs. This can be partially attributed to the relatively low price and also minor uncertainty associated with the projected uranium cost. It can be seen that the uncertainties in the demand parameters and the O&M costs of wind turbines and batteries play a significant role in contributing to operational cost uncertainty in the FD scenario. This aligns with their respective generation shares and the projected uncertainties associated with these technologies.

These findings suggest that, despite the high dimensionality of uncertainty, only a few key sources significantly impact system costs. This allows planners to focus on these critical uncertainties, work toward better understanding and modeling them, and ultimately incorporate them into the decision-making process. The findings also underscore the substantial influence of uncertainties related to future changes in hurricane frequency and organizational inefficiencies on total costs. These factors are often overlooked in the literature. Very few, if any, studies have considered organizational inefficiency in system cost analysis. Regarding uncertainties in future hurricane frequency, many studies adopt a scenario-based approach33,38, considering only a limited range of climate change impacts while overlooking the broader spectrum of potential variations. Our findings highlight the need to account for the full range of possibilities and their implications for system resilience when planning energy transitions.

Discussion

Long-term planning for energy transition faces inherent challenges posed by uncertainties. Numerous studies in the field often either overlook uncertainty entirely or account for a subset of its multifaceted sources. Such simplification of uncertainties may lead to myopic results, potentially resulting in a misallocation of resources through over- or under-designing systems. The primary limitation stems from the high dimensionality of uncertainty, driven by our limited knowledge (i.e., epistemic uncertainty). Specifically, uncertainty in projections of fuel prices, evolving technology costs, climate change, energy demand shifts, and organizational inefficiency contribute to this complexity. The challenge intensifies when considering aleatoric uncertainties arising from natural variations in climatic events and their consequential impacts. To alleviate the challenges from high-dimensional uncertainty, we introduced a nested MC framework that accounts for both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties for probabilistic analysis. The nested MC framework operates by embedding an internal MC engine within an external engine. For each epistemic uncertainty realization produced by the external MC engine, the internal MC engine samples aleatoric uncertainties to compute the expected cost for that specific realization. This was coupled with an efficient surrogate-based sensitivity analysis approach to identify the key sources of uncertainties.

We applied the proposed framework to Puerto Rico to conduct probabilistic cost and sensitivity analyses for three distinct energy transition scenarios. The outcomes of the probabilistic cost analysis highlighted the considerable breadth of cost distributions when incorporating various sources of uncertainty. Notably, it was shown that the presumed cost-effectiveness of the BAU scenario may not hold when considering uncertainties in projections of technology and fuel costs. For example, our analysis shows that there is a 38% and 41% chance that the FR and FD scenarios, respectively, will be less costly than the BAU scenario.

The results also highlighted the major role of climate change uncertainty on the cost of a hurricane-prone power system in 2050. In fact, it was shown that, regardless of the transition scenario, the uncertainty in changes in frequency and intensity of hurricanes accounts for more than 50% of the uncertainty of the system’s total expected cost. As for operational cost, our analysis shows that scenario-specific factors like fuel prices are dominant. It is, therefore, highly critical to account for climate change uncertainty for any long-term planning of power systems. This provides insights for climate scientists regarding the practical implications of uncertainty in climate change projections for long-term power system planning.

The role of organizational inefficiency as a source of uncertainty in power system costs has been largely (if not completely) overlooked in the literature. Due to the lack of data to accurately model this, we used multiple different distributions to represent inefficiency. We found that regardless of the modeling choice, inefficiency can be a major source of uncertainty concerning the cost of a power system. More studies are needed to enable more accurate modeling of organizational inefficiency. Additionally, future studies can discuss how such organizational uncertainty should be incorporated into the long-term planning of the system.

The findings also indicate that during the transition to fully renewable or decarbonized power systems, uncertainties in demand projections have a pronounced effect on the estimated expected system operational cost. This is attributed to the higher costs associated with balancing demand and generation in scenarios with especially high renewables penetration, in contrast to BAU situations where fossil fuel generation can consistently maintain energy system balance. Beyond this, for each scenario, the proposed framework enabled the identification of the main sources of uncertainty over the expected cost. These insights are vital for planners and policymakers, suggesting they can focus on a narrower set of uncertainties to better guide decision-making. They also provide guidance on where to direct data gathering and forecasting efforts to effectively mitigate existing uncertainties.

Although the results in this work are presented for three transition scenarios, the framework can be easily applied to other transition scenarios under different policies. For simplicity and brevity, we have assumed that the policies remain consistent across the planning horizon. However, the framework can also accommodate scenarios where the policy changes within the planning horizon. Additionally, this generic framework can be applied to any region of interest to facilitate the identification of key uncertainties for energy transition under the specific policies of that region.

We note that future research based on this work should aim to identify and address the endogeneity of factors influencing energy transitions. These factors include the effects of natural disasters on economic conditions and societal shifts towards renewable energy, the impact of various incentives and regulatory frameworks, public trust in governance, and the influence of policies on socioeconomic disparities and equity, all of which can significantly impact renewable energy adoption.

Methods

Case study input data

This study integrated data from diverse sources to construct a comprehensive perspective of Puerto Rico’s energy sector. Key resources included the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s 2013 report84 and the 2022 National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL) Annual Technology Baseline (ATB)69 for technology capacity factors as well as capital and O&M expenditure projections. Future population changes were inferred from the United Nations’ (UN) 2022 World Population Prospects85. Changes in demand per capita were extrapolated from the USA Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) projections for the USA and World Bank data, using a comparison with Puerto Rico’s historical data86,87,88. The renewable energy potential of Puerto Rico, focusing on solar and wind power, was borrowed from GIS-based calculations done in Bennett et al.’s work33. The potentials for biofuel generation, hydropower generation, and nuclear generation are obtained from NREL’s Energy Snapshots of Puerto Rico, and The Nuclear Alternative Project’s Preliminary Feasibility Study for Small Modular Reactors and Microreactors for Puerto Rico89,90. Existing power capacities were compiled from multiple sources: EIA’s Puerto Rico Profile, NREL’s Energy Snapshots of Puerto Rico, Worldometer’s electricity statistics of Puerto Rico, and the 2019 World Small Hydropower Development Report89,91,92,93.

Emission factors for various power generators were extracted from a USA Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) document94, and fuel price predictions were obtained from EIA data95. Weather forecasts were developed from Meteoblue’s simulations96, informed by 30 years of historical weather data from Puerto Rico. Information on historical hurricane trends and future hurricane characteristics was collected from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Historical Hurricane Tracks and Knutson et al.’s study97,98. Data on Puerto Rico’s current transmission and distribution systems were retrieved from the island’s geographic information system99. Restoration costs for transmission and distribution systems were estimated based on the North America Wood Pole Council’s ‘Out of Sight, Out of Mind’ study100. Lastly, electricity end-use tariff data were obtained from the EIA Energy Outlook document86. The details of the data used in this section are provided in Supplementary Notes 1–7.

To provide a clear overview, Table 1 summarizes the full range of uncertainties analyzed in this study. It distinguishes between epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties, outlines their respective modeling approaches and data sources, and includes a reference index to relevant supplementary notes.

TEMOA and power grid

In this study, we used TEMOA, an open-source model, to perform energy system optimization for Puerto Rico’s electricity infrastructure. The main TEMOA inputs include median projections of CAPEX as well as O&M costs for different types of power generators, various fuel prices, and electricity demand. Another critical factor is the weather forecast, which directly influences the generation activities of renewable power sources such as solar and wind. As documented in Hunter et al.68 and further explained in the continually updated documentation101, TEMOA minimizes the total cost of an energy supply system over a specified period.

TEMOA progressively expands power generation and transmission capacity across a series of future time frames that we define, based on forecasted demand for each time period. In this particular study, we segmented the timeline into six discrete five-year intervals starting from 2020 and extending to 2050. For each of these timeframes, TEMOA assumes a representative year with the same demand and generation activity persisting throughout the period. In reflecting Puerto Rico’s local conditions, we incorporated multiple types of representative days into the model to account for different weather patterns, such as sunny, partly cloudy, and cloudy days. Further granularity was achieved by considering 6 ranges of wind speeds. As a result, having 3 different sunniness conditions, 6 different windiness conditions, and dividing each representative day into daytime and nighttime periods, each year is divided into 36 different time slices. Each time slice serves as a snapshot of hourly changes in wind and solar energy availability as well as electricity demand. It must also be noted that, based on the findings of Angeles et al. 102, the potential effects of climate change on solar and wind power generation till 2050 were considered negligible.

TEMOA approaches the modeling of the electric grid from an aggregate perspective, rather than focusing on a detailed spatial representation. This decision not only aids in reducing computational requirements but also anticipates the likelihood of significant changes in the grid topology over the next three decades. The model is designed to ensure adequate power generation capacity and robust transmission and distribution system capacity for reliable electricity delivery. To mitigate potential operational disruptions, we have incorporated a reserve margin constraint into the model, thereby providing additional capacity when needed. This reserve margin is based on standard policies for the operation of the USA power grids.

Using TEMOA, we evaluate optimal values of power capacities and generation activities over a thirty-year span, from 2021 to 2050, assuming deterministic values for all TEMOA inputs (more information on inputs is provided in Supplementary Notes 1–4). This optimal configuration of the system, under deterministic assumptions, forms the bedrock for our subsequent post-processing work, enabling us to evaluate how different sources of uncertainty impact the cost of the system with supposedly optimal system architecture.

TEMOA model configuration choices (e.g., solver settings, time-slice structure, reserve margins, and representative weather conditions) are documented in the GitHub/Zenodo repository linked in the Code Availability section.

Probabilistic cost analysis

The probabilistic cost analysis aims to evaluate the distribution of total expected cost (encompassing operational cost, damage restoration cost, and power outage cost), in 2050, for different transition scenarios under various sources of uncertainty when the system is designed under deterministic treatment of uncertainties. This is done through a nested MC simulation that is designed to efficiently handle both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties, as shown in Fig. 1.

The external MC engine operates on the fixed system capacities determined by the initial TEMOA optimization. The external engine draws samples from the distribution of the epistemic uncertainties, generating 5000 unique scenarios. Each of these scenarios, representing a plausible ‘state of the world’ in 2050, is a distinct combination of values for parameters like technology costs (both capital and operation and maintenance), fuel prices, long-term hurricane frequency and intensity changes, and the organizational inefficiency factor.

For each of these external epistemic samples, the internal MC engine then performs a high number of simulations (1000 representative years) to account for aleatoric uncertainty. Specifically, the inner loop draws samples of annual weather conditions, the random occurrence and intensity of hurricanes, and the specific damages and restoration times. The expected values of the costs (operational, damage, and outage) across all the internal aleatoric simulations are then calculated.

To calculate operational cost, in each simulated year within the internal MC engine, a realization of weather conditions is drawn, which determines the distribution of sunny, partly cloudy, and overcast weather throughout the year, as well as the distribution of daily wind speeds within different speed ranges. These weather realizations determine the generation activities of solar and wind power generation and, hence, other generation types. Consequently, when the required generation activity from other generators exceeds their capacity factor, an additional 20% cost is applied to account for generation above the capacity factor. This surcharge reflects the higher operational expenses and maintenance needs when equipment is pushed beyond its designed capacity. Considering these factors, we compute the overall operational cost of the system.

To calculate the damage cost, in the internal MC engine, in each simulated year, random realizations of the frequency and intensity of hurricanes are drawn (more details in Supplementary Note 5) and then used in conjunction with the Poisson Pulse Process to generate realizations of hurricane occurrence scenarios in 2050. If at least one hurricane happens, the expected damage incurred by each part of the power grid system is computed. This calculation is based on the hurricane’s intensity and the fragility functions found in the literature for different power system components (more details in Supplementary Note 6). With the expected damages determined, the damage restoration costs are computed using the epistemic realizations of technology investment costs and the organizational inefficiency factor. Next, to calculate the expected power outage cost, the restoration period for each component is calculated using the restoration curves presented by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) HAZUS technical report103, which takes into account the damage state of the component and the restoration curves specific to each type of component (more details in Supplementary Note 7). Then the organizational inefficiency factor is multiplied by restoration periods to consider the effect of such systemic issues that may prolong the restoration time. Consequently, the serviceability ratio and restoration period for each hurricane event are determined. This information is then used in a power outage cost calculation method based on Garcia Cooper et al.104 in conjunction with the current socioeconomic factors of Puerto Rico, such as employment rate, gross national product, household income, and electricity tariffs to calculate power outage costs for different community sectors (residential, commercial, and industrial). It should be noted that in calculating power outage costs, our Monte Carlo simulations incorporate the correlation between electricity tariffs and per capita demand. Additionally, the increasing adoption of solar rooftops in Puerto Rico105,106 due to its high solar generation potential107, its past experiences with hurricanes and prolonged power outages108,109,110, and the falling price of this technology111 is accounted for, leading to the exclusion of residential outages equipped with solar rooftops from the power outage cost calculations. A detailed explanation of the methods employed for power outage cost analysis and modeling solar rooftop penetration can be found in Supplementary Notes 8 and 10, respectively.

Surrogate modeling

In order to reduce the computational cost associated with sensitivity analysis, we train deep neural network surrogates to estimate the expected total and operational cost in each transition scenario at different realizations of epistemic uncertainties. We perform hyperparameter tuning to investigate the optimal number of layers, number of hidden units, loss function type, regularization coefficient, and the number of epochs that ensure model accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. All the trained deep neural network surrogates outperform alternative analytical surrogates and achieve estimation accuracy above 93%.

Global sensitivity analysis using Sobol Indices

We use one of the most widely used GSA approaches, namely Sobol’s method, within the UQLab MATLAB framework, developed by Marelli et al.112. In this method, the variance of the output (i.e., system response) is partitioned into contributions from different uncertain inputs and their interactions. The Sobol Indices computation method is as follows: given a model output function f(x), where x = (x1, x2, …, xn) is the vector of input parameters, the total variance V of the function f can be represented as equation (1):

where \({\mathbb{E}}[f({{{\bf{X}}}})]=\int\,f({{{\bf{x}}}})\,d{{{\bf{x}}}}\) is the expected value or mean of the model output over the entire input space. The first-order Sobol Index Si for each input xi is then defined as Eq. (2):

where \({V}_{i}=\int{\left({f}_{{x}_{i}}({{{\bf{x}}}})-{\mathbb{E}}[f({{{\bf{X}}}})]\right)}^{2}\,d{{{\bf{X}}}}\) and \({f}_{{x}_{i}}({{{\bf{x}}}})={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{x}_{ \sim i}}[f({{{\bf{x}}}})]\) is the expected value of the model output, conditioning on all variables except xi. In an MC approach, this would involve randomly sampling all other variables while keeping xi fixed. The total-effect index Ti for the input xi is given by Eq. (3):

where \({V}_{ \sim i}=\int{\left({f}_{{x}_{ \sim i}}({{{\bf{x}}}})-{\mathbb{E}}[f({{{\bf{X}}}})]\right)}^{2}\,d{{{\bf{X}}}}\) and \({f}_{{x}_{ \sim i}}({{{\bf{x}}}})={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{x}_{i}}[f({{{\bf{x}}}})]\) is the expected value of the model output, conditioning on xi alone. This is achieved by varying xi and keeping all other variables fixed.

Data availability

The input data used in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16891750. The same data are also available in the associated GitHub repository at https://github.com/kamiarkhayam/PuertoRico-EnergyTransition-ProbabilisticAnalysis. The deposited dataset includes all input files and documentation required to interpret and extend the findings of this work. Additional explanations of datasets, parameter values, and modeling assumptions are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

The simulation and surrogate modeling code generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under accession code Khayambashi2025Zenodo. The same code is also available in the associated GitHub repository at https://github.com/kamiarkhayam/PuertoRico-EnergyTransition-ProbabilisticAnalysis113. The repository provides the complete package, including TEMOA, Python, and MATLAB scripts, and detailed README files describing how to execute the code and replicate the analysis.

References

Pfeiffer, A., Hepburn, C., Vogt-Schilb, A. & Caldecott, B. Committed emissions from existing and planned power plants and asset stranding required to meet the Paris Agreement. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 054019 (2018).

Tong, D. et al. Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5 c climate target. Nature 572, 373–377 (2019).

Ritchie, H., Rosado, P. & Roser, M. Emissions by sector: where do greenhouse gases come from?Our World in Data (2020). https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector. Accessed March 25, 2024.

EDGAR/JRC. Distribution of carbon dioxide emissions worldwide in 2022, by sector [Graph]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1129656/global-share-of-co2-emissions-from-fossil-fuel-and-cement/ (2023). Accessed March 25, 2024.

Owusu, P. A. & Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. A review of renewable energy sources, sustainability issues and climate change mitigation. Cogent Eng. 3, 1167990 (2016).

Bessa, R., Moreira, C., Silva, B. & Matos, M. Handling renewable energy variability and uncertainty in power systems operation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Energy Environ. 3, 156–178 (2014).

Oree, V., Hassen, S. Z. S. & Fleming, P. J. Generation expansion planning optimisation with renewable energy integration: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 69, 790–803 (2017).

Alemazkoor, N. et al. Hurricane-induced power outage risk under climate change is primarily driven by the uncertainty in projections of future hurricane frequency. Sci. Rep. 10, 15270 (2020).

Ji, C. et al. Large-scale data analysis of power grid resilience across multiple us service regions. Nat. Energy 1, 1–8 (2016).

Connolly, D., Lund, H. & Mathiesen, B. V. Smart energy europe: The technical and economic impact of one potential 100% renewable energy scenario for the European Union. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 1634–1653 (2016).

Dominković, D. F. et al. Zero carbon energy system of South East Europe in 2050. Appl. energy 184, 1517–1528 (2016).

Lund, H. & Mathiesen, B. V. Energy system analysis of 100% renewable energy systems–the case of Denmark in years 2030 and 2050. Energy 34, 524–531 (2009).

Newlun, C. J., Currie, F. M., O’Neill-Carrillo, E., Bezares, E. A. & Byrne, R. H. Energy resource planning for Puerto Rico’s future electrical system. In 2020 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition (T&D), 1–5 (IEEE, 2020).

Parés-Atiles, E., O’Neill-Carrillo, E. & Andrade, F. Best practices for microgrids applied to a case study in a community. In 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), 1–5 (IEEE, 2020).

Ahmad, A. Increase in frequency of nuclear power outages due to changing climate. Nat. Energy 6, 755–762 (2021).

Schweikert, A. E. & Deinert, M. R. Vulnerability and resilience of power systems infrastructure to natural hazards and climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 12, e724 (2021).

Ouyang, M. & Duenas-Osorio, L. Multi-dimensional hurricane resilience assessment of electric power systems. Struct. Saf. 48, 15–24 (2014).

Araújo, K. & Shropshire, D. A meta-level framework for evaluating resilience in net-zero carbon power systems with extreme weather events in the United States. Energies 14, 4243 (2021).

Mahzarnia, M., Moghaddam, M. P. & Haghifam, M.-R. A novel three-stage risk-based scheme to improve power system resilience against hurricanes. Comput. Electr. Eng. 93, 107309 (2021).

Sabouhi, H., Doroudi, A., Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M. & Bashiri, M. Electrical power system resilience assessment: A comprehensive approach. IEEE Syst. J. 14, 2643–2652 (2019).

Nofal, O. M. et al. Multi-hazard socio-physical resilience assessment of hurricane-induced hazards on coastal communities. Resilient Cities Struct. 2, 67–81 (2023).

Yalew, S. G. et al. Impacts of climate change on energy systems in global and regional scenarios. Nat. Energy 5, 794–802 (2020).

Van Ruijven, B. J., De Cian, E. & Sue Wing, I. Amplification of future energy demand growth due to climate change. Nat. Commun. 10, 2762 (2019).

Fan, J.-L., Hu, J.-W. & Zhang, X. Impacts of climate change on electricity demand in China: An empirical estimation based on panel data. Energy 170, 880–888 (2019).

McCollum, D. L. et al. Quantifying uncertainties influencing the long-term impacts of oil prices on energy markets and carbon emissions. Nat. Energy 1, 1–8 (2016).

He, G. et al. Rapid cost decrease of renewables and storage accelerates the decarbonization of China’s power system. Nat. Commun. 11, 2486 (2020).

Yang, Q. et al. Prospective contributions of biomass pyrolysis to China’s 2050 carbon reduction and renewable energy goals. Nat. Commun. 12, 1698 (2021).

Mauler, L., Duffner, F., Zeier, W. G. & Leker, J. Battery cost forecasting: a review of methods and results with an outlook to 2050. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4712–4739 (2021).

Schmidt, O., Hawkes, A., Gambhir, A. & Staffell, I. The future cost of electrical energy storage based on experience rates. Nat. Energy 2, 1–8 (2017).

Heuberger, C. F., Staffell, I., Shah, N. & Mac Dowell, N. Impact of myopic decision-making and disruptive events in power systems planning. Nat. Energy 3, 634–640 (2018).

Motlaghzadeh, K., Schweizer, V., Craik, N. & Moreno-Cruz, J. Key uncertainties behind global projections of direct air capture deployment. Appl. Energy 348, 121485 (2023).

Taghizadeh, M., Khayambashi, K., Hasnat, M. A. & Alemazkoor, N. Multi-fidelity graph neural networks for efficient power flow analysis under high-dimensional demand and renewable generation uncertainty. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 237, 111014 (2024).

Bennett, J. A. et al. Extending energy system modelling to include extreme weather risks and application to hurricane events in Puerto Rico. Nat. Energy 6, 240–249 (2021).

Perera, A., Nik, V. M., Chen, D., Scartezzini, J.-L. & Hong, T. Quantifying the impacts of climate change and extreme climate events on energy systems. Nat. Energy 5, 150–159 (2020).

Bloomfield, H. et al. Quantifying the sensitivity of European power systems to energy scenarios and climate change projections. Renew. Energy 164, 1062–1075 (2021).

Newlun, C. J., Figueroa-Acevedo, A. L., McCalley, J. D., Kimber, A., & O’Neill-Carrillo, E. Co-optimized expansion planning to enhance electrical system resilience in Puerto Rico. In the 2019 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Blazquez, J., Nezamuddin, N. & Zamrik, T. Economic policy instruments and market uncertainty: Exploring the impact on renewables adoption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 94, 224–233 (2018).

Moglen, R. L. et al. A nexus approach to infrastructure resilience planning under uncertainty. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 230, 108931 (2023).

Singh, V., Moger, T. & Jena, D. Uncertainty handling techniques in power systems: A critical review. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 203, 107633 (2022).

Chen, C., Wiser, R., Mills, A. & Bolinger, M. Weighing the costs and benefits of state renewables portfolio standards in the United States: A comparative analysis of state-level policy impact projections. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 552–566 (2009).

Lopez-Cardalda, G. & Ortiz-Rivera, E. I. Proposed methodology using the energy storage system prioritization index. In 2021 IEEE 48th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), 2529–2533 (IEEE, 2021).

Al Jazeera. Brazil audit: ‘corrupt World Cup costs’. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2014/5/13/brazil-audit-corrupt-world-cup-costs (2014). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Bleacher Report. How much has hosting the World Cup cost Brazil?https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1845944-how-much-has-hosting-the-world-cup-cost-brazil (2014). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Johnson, G. Governor seeks to take control of big dig inspections. https://web.archive.org/web/20070311201155/http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2006/07/13/governor_seeks_to_take_control_of_big_dig_inspections (2006). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Eddy, M. Denver International Airport officially opens for business. https://www.denverpost.com/1995/02/28/denver-international-airport-officially-opens-for-business/ (1995). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Jaffe, E. From $250 million to $6.5 billion: The Bay Bridge cost overrun. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-10-13/how-the-cost-of-remaking-the-san-francisco-bay-bridge-soared-to-6-5-billion (2015). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

McMahon, E. Digging deeper on the (very deep) east side access project. https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/digging-deeper-on-the-very-deep-east-side-access-project/ (2021). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Horowitz, J. & Bubola, E. Venice is saved! Woe is venice.https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/01/world/europe/venice-mose-flooding.html (2023). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Nicola, S. Berlin’s $7 billion airport finally opens in the depths of a crisis. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-10-30/berlin-s-7-billion-brandenburg-airport-finally-opens-in-the-depths-of-a-crisis (2020). Accessed: 2024-02-12.

Castro-Sitiriche, M., Cintrón-Sotomayor, Y. & Gómez-Torres, J. The longest power blackout in history and energy poverty. In Proc. 8th Int. Conf. Appropriate Technol, 36–48 (2018).

O’Neill-Carrillo, E. & Rivera-Quinones, M. A. Energy policies in Puerto Rico and their impact on the likelihood of a resilient and sustainable electric power infrastructure. Cent. J. 30 (2018).

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Energy Public Policy Act (2019).

Santiago, R., de Onís, C. M. & Lloréns, H. Powering life in Puerto Rico: The struggle to transform Puerto Rico’s flawed energy grid with locally controlled alternatives is a matter of life and death. NACLA Rep. Am. 52, 178–185 (2020).

Anand, H., Alemazkoor, N. & Shafiee-Jood, M. Hevod: A database of hurricane evacuation orders in the United States. Sci. Data 11, 270 (2024).

Lopez-Cardalda, G., Lugo-Alvarez, M., Mendez-Santacruz, S., Rivera, E. O. & Bezares, E. A. Learnings of the complete power grid destruction in Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria. In 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Kwasinski, A., Andrade, F., Castro-Sitiriche, M. J. & O’Neill-Carrillo, E. Hurricane maria effects on Puerto Rico electric power infrastructure. IEEE Power Energy Technol. Syst. J. 6, 85–94 (2019).

Nieves, M. V. et al. Analysis of PV microgrids with storage to improve the resiliency of the island of Culebra, Puerto Rico. In 2022 Resilience Week (RWS), 1–8 (IEEE, 2022).

Oneill, E., McCalley, J., Kimber, A. & Haug, R. Stakeholder perspectives on increasing electric power infrastructure integrity. In ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition (2019).

Pietri, G. Neglect, corruption left Puerto Rico’s power grid ripe for failure, observers say. https://www.voanews.com/a/experts-say-neglect-corruption-left-puerto-rico-power-grid-ripe-for-failure/4144129.html (2017). Accessed: 2024-08-14.

Akpan, N. Puerto rico energy authority investigates dozens of post-Maria bribery cases. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/puerto-rico-energy-authority-investigates-dozens-of-post-maria-bribery-cases (2018). Accessed: 2024-08-14.

Bases, D. U.S. House panel probes corruption allegations at Puerto Rico utility. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-puertorico-prepa-probe/u-s-house-panel-probes-corruption-allegations-at-puerto-rico-utility-idUSKCN1GP03P/ (2018). Accessed: 2024-08-14.

Kunkel, C. & Sanzillo, T. IEEFA Puerto Rico: What the corruption scandal means for the Puerto Rico electric power authority (PREPA). https://ieefa.org/resources/ieefa-puerto-rico-what-corruption-scandal-means-puerto-rico-electric-power-authority (2019). Accessed: 2024-08-14.

117th Congress. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376 (2022). Public Law No: 117-169. Sponsored by Rep. John A. Yarmuth [D-KY-3]. Became law on August 16, 2022.

U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Earthshots initiative. https://www.energy.gov/policy/energy-earthshots-initiative (2023). Accessed 2023.

Government Offices of Sweden, Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency. Sweden’s climate policy framework. https://www.government.se/articles/2021/03/swedens-climate-policy-framework/ (2021). Article from the Ministry of Climate and Enterprise, Published 11 March 2021.

German Federal Government. Climate Change Act 2021: Intergenerational contract for the climate. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/schwerpunkte/klimaschutz/climate-change-act-2021-1936846 (2021). Published on 25 June 2021.

Wu, H.-H. Moving toward a net-zero emission society: with special reference to the recent law and policy development in some selected countries. In Moving Toward Net-Zero Carbon Society: Challenges and Opportunities, 151–169 (Springer International Publishing Cham, 2023).

Hunter, K., Sreepathi, S. & DeCarolis, J. F. Modeling for insight using tools for energy model optimization and analysis (TEMOA). Energy Econ. 40, 339–349 (2013).

Vimmerstedt, L. et al. 2022 annual technology baseline (ATB) cost and performance data for electricity generation technologies. Tech. Rep., DOE Open Energy Data Initiative (OEDI); National Renewable Energy Laboratory (2022).

Tavoni, M. & Van der Zwaan, B. Nuclear versus coal plus CCS: a comparison of two competitive base-load climate control options. Environ. Model. Assess. 16, 431–440 (2011).

Schipfer, F. et al. Status of and expectations for flexible bioenergy to support resource efficiency and to accelerate the energy transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112094 (2022).

Thrän, D., Eichhorn, M., Krautz, A., Das, S. & Szarka, N. Flexible power generation from biomass–an opportunity for a renewable sources-based energy system? In Transition to Renewable Energy Systems, 499–521 (2013).

Mahsuli, M. & Haukaas, T. Seismic risk analysis with reliability methods, part i: Models. Struct. Saf. 42, 54–62 (2013).

Nasrazadani, H. & Mahsuli, M. Probabilistic framework for evaluating community resilience: Integration of risk models and agent-based simulation. J. Struct. Eng. 146, 04020250 (2020).

Taghizadeh, M., Mahsuli, M. & Poorzahedy, H. Probabilistic framework for evaluating the seismic resilience of transportation systems during emergency medical response. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 236, 109255 (2023).

Mok, Y. & Chung, T. Prediction of domestic, industrial and commercial interruption costs by relational approach (1997).

Foster, E. et al. The unstudied barriers to widespread renewable energy deployment: Fossil fuel price responses. Energy Policy 103, 258–264 (2017).

Dumas, M., Kc, B. & Cunliff, C. I. Extreme weather and climate vulnerabilities of the electric grid: a summary of environmental sensitivity quantification methods. Tech. Rep., Oak Ridge National Lab.(ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN (United States) (2019).

Chen, S.-E. et al. Post-hurricane investigation of a critical component toward improved grid resiliency in Puerto Rico. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 34, 02520001 (2020).

O’Neill-Carrillo, E., Mercado, E., Luhring, O., Jordan, I. & Irizarry-Rivera, A. Community energy projects in the Caribbean: Advancing socio-economic development and energy transitions. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 38, 44–55 (2019).

Chen, S.-E. et al. Resiliency of power grid infrastructure under extreme hazards-observations and lessons learned from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. In Advanced Geotechnical and Structural Engineering in the Design and Performance of Sustainable Civil Infrastructures: Proceedings of the 6th GeoChina International Conference on Civil & Transportation Infrastructures: From Engineering to Smart & Green Life Cycle Solutions–Nanchang, China, 2021 6, 1–17 (Springer, 2021).

Sudret, B. Global sensitivity analysis using polynomial chaos expansions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 93, 964–979 (2008).

Shen, L., Tang, Y. & Tang, L. C. Understanding key factors affecting power systems resilience. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 212, 107621 (2021).

Engineers, P. Fortieth annual report on the electric property of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (2013).

Post-hurricane United Nations Population Prospects 2022. https://population.un.org/wpp/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Annual Energy Outlook 2023. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Khadan, J., To, A. T. Y., Cortez, C. & Bai, Y. World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Ritchie, H., Roser, M. & Rosado, P. Energy. Our World in Data (2022).

National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Energy snapshot Puerto Rico (2015).

Dulloo, A. et al. Preliminary feasibility study for small modular reactors and microreactors for Puerto Rico. Tech. Rep., Nuclear Alternative Project (2020). Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy.

Puerto Rico: Territory profile and energy estimates. https://www.eia.gov/state/print.php?sid=RQ. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Puerto Rico electricity statistics. https://www.worldometers.info/electricity/puerto-rico-electricity/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

World small hydropower development report 2019. https://www.unido.org/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

2023 ghg emission factors hub. https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/ghg-emission-factors-hub. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Us electricity profile 2021. https://www.eia.gov/electricity/state/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Simulated historical climate & weather data for Puerto Rico. https://www.meteoblue.com/en/weather/historyclimate/climatemodelled/puerto-rico_puerto-rico. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Historical hurricane tracks. https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part ii: Projected response to anthropogenic warming. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E303–E322 (2020).

Descarga de geodatos. http://www.gis.pr.gov/descargaGeodatos/Infraestructuras/Pages/Electricidad.aspx. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Hall, K. L. Out of sight, out of mind: an updated study on the undergrounding of overhead power lines. Edison Electric Institute (2012).

Temoa project documentation. https://TEMOAcloud.com/TEMOAproject/index.html. Accessed on May 24, 2023.

Angeles, M. E., González, J. E., Erickson, D. J. I. I. I. & Hernández, J. L. The impacts of climate change on renewable energy resources in the Caribbean region. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 132, 031008 (2010).

FEMA. HAZUS-MH 5.1 Earthquake Model Technical Manual (2022).

Cooper, R. A. G., Sitiriche, M. C., Rivera, A. I. & Rengifo, F. A. True cost of electric service: What reliability metrics alone fail to communicate. Electr. J. 37, 107386 (2024).

Sandoval, M. F., Hernandez, J., Grijalva, S., Broderick, R. J. & O’Neill-Carrillo, E. Optimal portfolio design of distributed energy resources on Puerto Rico distribution feeders with long outages after Hurricane Maria. Tech. Rep., Sandia National Lab.(SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States) (2022).

Irizarry-Rivera, A. A., Castro-Sitiriche, M. J., Orama-Exclusa, L. & Lugo-Hernández, E. A. Distributed rooftop solar photovoltaic generation adoption in Puerto Rico. University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (2023). http://cohemisferico.uprm.edu/pr100/pdf/Memo03UPRMpr100_PVAdoption.pdf.

Garzon, O. D. et al. Integration and assessment of photovoltaic systems in Puerto Rican communities. In 2023 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Latin America (ISGT-LA), 375–379 (IEEE, 2023).

Lugo-Hernández, E. A., Castro-Sitiriche, M. J., Irizarry-Rivera, A. A. & Orama-Exclusa, L. Comprehensive survey of residential photovoltaic systems in Puerto Rico. Tech. Rep., University of Puerto Rico - Mayagüez (UPRM) (2023). http://cohemisferico.uprm.edu/pr100/pdf/Memo02UPRMpr100_PVQuestionnaire.pdf. Results from the PR100 UPRM Team.

Echevarria, A. et al. Unleashing sociotechnical imaginaries to advance just and sustainable energy transitions: The case of solar energy in Puerto Rico. IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc. 4, 255–268 (2022).

Saker, F., Lopez, G., Pacheco, J., Ortiz-Rivera, E. & Aponte, E. Design of a microgrid for rural community in Puerto Rico. In 2021 IEEE 48th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), 1758–1761 (IEEE, 2021).

Orama-Exclusa, L., Irizarry-Rivera, A., Castro-Sitiriche, M. J. & Lugo-Hernández, E. Distributed rooftop solar photovoltaic plus batteries cost in Puerto Rico. Tech. Rep., University of Puerto Rico - Mayagüez (UPRM) (2023). http://cohemisferico.uprm.edu/pr100/pdf/Memo04UPRMpr100_PVSystemCost.pdf. Results from the PR100 UPRM Team.

Marelli, S. & Sudret, B. OQLab: A framework for uncertainty quantification in MATLAB. In Vulnerability, uncertainty, and risk: quantification, mitigation, and management, 2554–2563 (2014).

Khayambashi, K., Clarens, A. F., Shobe, W. M. & Alemazkoor, N. “PuertoRico-EnergyTransition-ProbabilisticAnalysis,” Code and data repository for “Identifying Key Uncertainties in Energy Transitions with a Puerto Rico Case Study,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/kamiarkhayam/PuertoRico-EnergyTransition-ProbabilisticAnalysis [Accessed: Aug. 17, 2025].

Landfill gas to renewable energy: Benefits of capturing and harnessing methane emissions from municipal solid waste landfills. EESI Hill Briefing (2013).

Panteli, M., Pickering, C., Wilkinson, S., Dawson, R. & Mancarella, P. Power system resilience to extreme weather: Fragility modeling, probabilistic impact assessment, and adaptation measures. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 32, 3747–3757 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Climate Restoration Initiative of the University of Virginia Environmental Institute (A.F.C., N.A., W.M.S.) and The David & Joy Peyton Family Fund (W.M.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A. conceived the idea. N.A., A.F.C., and W.M.S. supervised the study. K.K. gathered data, designed the framework, conducted the deterministic optimization, probabilistic analysis as well as sensitivity analysis, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. N.A. prepared a revision of the manuscript. N.A., A.F.C., W.M.S., and K.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Marcel Castro Sitiriche, Mike Gordon and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khayambashi, K., Clarens, A.F., Shobe, W.M. et al. Identifying key uncertainties in energy transitions with a Puerto Rico case study. Nat Commun 16, 9064 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64143-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64143-1

This article is cited by

-

Identifying key uncertainties in energy transitions with a Puerto Rico case study

Nature Communications (2025)