Abstract

Proton exchange membrane water electrolysis attracts worldwide attention as a promising technology for green H2 production and renewable energy storage, yet the safety considerations in the industrial-scale operations are largely overlooked. Herein, localized deflagration in 100 kW and 2 kW proton exchange membrane water electrolysis stacks are reported. Water-starvation induced by flow channel obstruction is identified as the cause of the incident. The incident is reproduced in single electrolyzers, with the membrane electrode assembly deflagration process captured in-situ and studied. Physicochemical analysis and simulations reveal that water-starvation reduces membrane conductivity by 100-fold, generating large Joule heating to elevate membrane electrode assembly temperature above 150 °C, which softens membrane and leads to perforation under thermomechanical stress, subsequent H2 - O2 mixing and deflagration. Safety precautions are established, including materials and component designs, and monitoring strategies, with methods enabling early warning of deflagration in a 5 kW differential pressure stack. This work proposes both the fundamental understanding of deflagration mechanisms and practical guidelines for safe industrial scale-up of proton exchange membrane water electrolysis technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proton exchange membrane (PEM) water electrolysis represents a promising green H2 production technology that utilizes only pure water as feedstock, producing zero pollutants during operation. This technology features high energy efficiency, rapid dynamic response, compact system design and capability to operate under high pressure, rendering it a competitive solution for renewable energy conversion, power grid balance, and high purity H2 supply for chemical engineering processes1,2. The development of PEM water electrolysis has gained significant momentum in both industrial and academic sectors. As reported by International Energy Agency (IEA), the global installed capacity of PEM water electrolysis stacks has reached about 300 MW in 2023, with China, European Union, and United States emerging as the leading markets3. Academic research continues to address critical scientific challenges, focusing on developing low- or non-iridium oxygen evolution catalysts4, composite PEM5, and novel porous transport layers (PTLs) structure6. However, this rapid growth might overshadow certain fundamental safety considerations, particularly given H2’s intrinsic characteristics – high diffusivity, low ignition energy (< 4 µJ in O2), and wide flammability range (4 − 94 vol. % in O2)7,8.

In the PEM water electrolyzers, membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs) serve as the core component, comprising PEM, anodic/cathodic catalytic layers (CLs), and anodic/cathodic PTLs. Unlike PEM fuel cells (FCs), where H2 and O2 are consumed9, these gases are generated at the cathode and anode sides, respectively. This reversed operation leads to a contrasting gas distribution pattern, with the highest H2 concentration occurring at the cathodic CL – PEM interface, leading to unwanted H2 permeation into O2 sides (Fig. 1a, b). Combined with the high operating pressures (> 3.0 MPa) in stacks, membrane damage or pinholes can lead to severe H2 – O2 mixing issues10. Recently, a concerning safety incident occurred in our industrial partner’s 100 kW PEM water electrolysis stack, resulting in severe MEA and bipolar plate (BPP) perforation (Fig. 1c–e). A similar incident was subsequently observed in our lab in a 2 kW stack. These incidents exhibited a distinctive pattern: the stack operated normally for tens of days before sudden incidents, suggesting an underlying progressive deterioration mechanism that was not detectable during routine operation. Although such incidents in lab- and pilot-scale stacks resulted in localized damage, similar mechanisms could pose catastrophic risks in Megawatt-scale industrial H2 plants. Therefore, it is urgent to thoroughly understand the underlying mechanisms of these incidents and develop corresponding safety precautions.

a H2 concentration depletion in anodic CL of PEM fuel cells. b H2 supersaturation at the PEM - CL interface with severe H2 crossover to O2 flow in PEM water electrolyzer. c 100 kW PEM water electrolysis stack after malfunction, with the red circle indicating the damaged region. d Perforated bipolar plate (overall size: 658 × 328 mm) showing burned region with ~ 100 mm in diameter. e Perforated MEA with a hole of ~ 100 mm in diameter. PTL porous transport layer; CL catalytic layers; PEM proton exchange membrane.

In this study, we analyzed malfunctioned 2 kW and 100 kW stacks, revealing that anode flow field obstruction should be the triggering mechanism of the events. Subsequently, this malfunction was reproduced in the single electrolyzers, and a deflagration process was captured by in situ high-speed camera. Experiments with varying water flow rates established the minimum water inlet flow rate for safe operation. Moreover, X-ray computed tomography analysis of MEAs under water-starvation conditions showed progressive PEM thinning, which resulted in H2 - O2 mixing and subsequent ignition in CLs. At last, a series of safety precautions were suggested, including optimized flow field designs, advanced composite PEMs, and additional parameters to be monitored. The implemented monitoring system gave early warning and prevented an explosion during long-term durability tests of a new 5 kW PEM water electrolysis stack operating at 3.0 MPa differential pressure.

Results

Electrochemical behaviors and deflagration process

An 8-cell PEM water electrolysis stack (2 kW) was operated intermittently for one month under stepwise current cycling (current increment: 1.0 A, feed water flow rate: 2.5 L min−1, active area: 98 cm2), and a serious incident occurred at over 50 A during one of these cycles. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a, the stack functioned normally when the operating current was below 50 A. As the current continued to increase, the electrolysis voltage abruptly jumped from 13.5 V to 23.3 V. This abnormally high voltage persisted for about 70 s. The voltage then dropped to 8.7 V, a level insufficient to sustain normal operation of the stack, indicating internal malfunction. After disassembling the stack, one bipolar plate (BPP) was found perforated, with severe burn marks observed on two adjacent BPPs. Furthermore, four MEAs positioned between the three BPPs were also perforated (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e), confirming the occurrence of a short circuit across four cells. This explains the continued production of H2 and O2 despite the reduced stack voltage. Post-hoc analysis found that the inlet channel of the damaged BPP (one cell) was partially obstructed by the sealing frame (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g), which could induce water starvation. This phenomenon was possibly attributed to material expansion during long-term operation in 40–50 °C water.

To confirm the water starvation hypothesis, we designed a 4-cell PEM water electrolysis stack with independent water feed control (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). We reduced the feed water flow rate of one target cell by about 30-fold while maintaining normal flow rates in the other 3 cells to simulate the inlet channel obstruction. Under these controlled water starvation conditions, a voltage increase in the target cells followed by short circuit was observed, while the other 3 cells continued normal operation (experimental condition and electrochemical analysis detailed in Supplementary Note 1). Stack disassembly revealed MEA perforation and severe burn marks on the corresponding BPPs (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f), identical to the malfunction observed in the 2 kW stack. These controlled experiments confirm that water starvation is the fundamental cause of the malfunction. This raises a fundamental question about the specific electrochemical and thermal mechanisms that drive the evolution process from water starvation to MEAs and BPPs perforation.

To investigate these underlying mechanisms, we conducted control experiments on a single electrolyzer. The operation current was set to 100.0 A with an upper voltage limit of 10.0 V (experimental conditions selection detailed in Supplementary Note 2). Water-starvation conditions were conducted by controlling the feed water flow rate (Fl). A stoichiometric ratio (ξ) was introduced to represent the ratio of Fl to theoretical H+ transport amount at 100.0 A, as determined by Eqs. (1–3). The electrolyzer was first operated at 100.0 A with Fl = 100.0 mL min−1, followed by adjustments to specified ξ values. Figure 2 shows the electrochemical performance curves, including voltage time (V-t) and current time (i-t) curves, and MEAs’ temperature time (TMEA-t) curves under ξ = 2, 4, 6, 8. Based on the electrochemical and thermal behaviors, we classify the water starvation induced malfunction process into 4 stages, demonstrating this progression most clearly in Fig. 2b, with all parameter variations summarized in Supplementary Table 1. In the 1st stage, following the Fl reduction, the electrolyzers maintain normal operation for 7, 30, 150, 1020 s at ξ = 2, 4, 6, 8, respectively, indicating a positive correlation. This initial normal operation might result from residual water in MEAs, with lower ξ leading to faster water consumption. In the 2nd stage, the voltage suddenly increases to the upper protection voltage of 10.0 V. In the 3rd stage, while the voltage remains at 10.0 V, the current gradually decreases. During this stage, all experiments show the current reduction to 20–30 A. The current exhibits significant fluctuations ranging from several amperes to 50 A, indicating a common MEAs evolution process across all conditions. For ξ = 2, 4, and 6, the 4th stage emerges where the current returns to 100.0 A while the voltage drops below 1.5 V, suggesting a short circuit. The duration of the 3rd stage increases with ξ. At ξ = 8, while no short circuit occurs during 5 h test, we anticipate the eventual appearance of the 4th stage with extended testing. In addition, TMEA monitoring was conducted by fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors positioned in the cathode flow channel11 (Supplementary Fig. 4), as conventional ultra-fine thermocouples are susceptible to electric-field interference. In all the experiments, TMEA rapidly increases from about 70 °C when the voltage rises. The sustained high voltage (10.0 V), exceeding the thermoneutral voltage (1.48 V), results in continuous TMEA rise through Joule heating throughout the 2nd and 3rd stages12. When the duration of the 3rd stage exceeded 600 s, TMEA stabilizes at about 140 °C. At last, upon disassembling the electrolyzers, MEA perforation is observed in the experiment with ξ = 2, 4, and 6 (Supplementary Fig. 5). While the flow field plates (FFPs) remain intact due to their greater thickness compared to BPPs, damage marks appear on their ribs. These single electrolyzer experiments partially reproduce the stack malfunction characteristics, including the voltage surge before short circuit and MEA perforation.

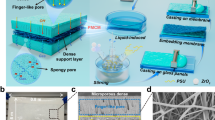

To directly visualize the internal processes during malfunction, we developed an in situ observation system with a transparent plate and high-speed camera (Fig. 3a). Quartz was applied as the transparent backing plate due to its high thermal resistance, superior to traditional acrylic plates (thermal softening temperature: ~ 100 °C), considering the observed TMEA of 140 °C. The in situ visualization experiment was conducted under ξ = 2, with three parallel experiments recording the anode side malfunctions (Supplementary Movies 1–3), and one recording the cathode side response (Supplementary Movie 4). This in situ visualization study provides strong experimental evidence of deflagration occurring consistently at the anode side in all three experiments, with no visible similar events occurring at the cathode. Frame-by-frame analysis of Supplementary Movie 1 was conducted to reveal the detailed deflagration sequence at the anode side (Fig. 3b). A localized flame point initially emerges in the upper left region of the flow field, distant from the water inlet. The deflagration rapidly propagated through one channel in 11 ms, followed by ignition of the upper channel at about 132 ms. Subsequently, the deflagration spread to the lower channel, generating intense flames propagating towards the outlet with deflagration velocities of several meters per second. Ti-ribs exhibit red-hot glow and severe deformation under intense heat (232, 332, and 632 ms). The entire intense deflagration process lasted for over 600 ms before the flames gradually extinguishes after about 8 s. After disassembling the electrolyzer, severe structural damage was observed with the second Ti-rib completely burned through, and a small pit formed in the quartz backing plate. Given the melting points of Ti (1668 °C) and quartz (1723 °C), the observed damage indicates that the local TMEA during deflagration transiently exceeded 1700 °C. Such extreme temperatures cannot be attributed to Joule heating alone, suggesting the occurrence of H2 and O2 mixing and subsequent deflagration. Water electrolysis naturally generates twice mole amount of H2 compared to O2, and H2 diffuses much faster than O2, leading to preferential gas mixing at the anode side. In the single electrolyzer, the deflagration extinguishes quickly since the limited H2 content is soon consumed, while in stacks, ongoing H2 production from neighboring cells supplies the deflagration, making it last longer and spread more widely. These visualization results clearly demonstrate the malfunction caused by H2 - O2 mixing in both single electrolyzers and stacks.

Further investigation revealed an unexpected phenomenon when reassembling the electrolyzers with previously deflagrated FFPs (referred to as oxidized FFPs): deflagration events can occur at higher ξ (Supplementary Note 3 for detailed analysis). Polarization curves (Supplementary Fig. 6a) show comparable performance between oxidized and fresh FFPs, indicating that localized burn marks don’t influence the performance. However, water starvation experiments with oxidized FFPs at ξ = 8, 10, 14, and 16 show the same 4-stage progression as observed in lower ξ experiments (Supplementary Fig. 6b–e). Notably, the duration of the 3rd stage is only 17 and 118 s for ξ = 14, and 16, respectively, matching the duration observed in stack malfunction (~ 70 s). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the deflagration events consistently initiate at locations corresponding to previous burn marks on the FFPs. In addition, TMEA also shows the same pattern as the experiments equipped with fresh FFPs. When the FBG sensors are positioned near these locations, we can observe rapid temperature spikes exceeding 300 °C, which is the upper limit of the temperature sensors applied (no available temperature sensors can reliably measure the expected temperature of ~ 1700 °C in such environments). These results indicate that the localized FFP damage creates preferential sites for subsequent deflagration, effectively raising the water-starvation threshold required for this malfunction. When ξ = 22, no malfunction or high voltage is observed even with oxidized FFPs during 5 h operation. Based on these findings, we determine a minimum ξ of 22 to ensure safe electrolyzer operation.

Formation mechanisms

To clarify the deflagration mechanism, we first investigated the unusual V-t curve in all experiments. The sudden voltage increases to 10.0 V in the 2nd stage should not be attributed to catalyst deactivation, as the timescale (typically < 30 min) is far shorter than the catalyst’s lifespan (thousands of hours). H+ transport in PEM is also a key factor, which relies on H2O to form hydronium ions (H3O+) for conduction13. Since the hydration state of PEM (Nafion) affects its H+ conductivity (σ)14, we investigated this effect through both simulation and experimental methods.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to calculate the H3O+ diffusion coefficient (D0) in Nafion, which correlates with σ by Nernst-Einstein formula15 (Eq. (6)). Using λ (the ratio of H2O to -SO3H in Nafion, Equation (S1))16 to represent the hydration states, we analyze the mean square displacement (MSD) of H3O+ under various conditions (Fig. 4a). The results show dramatic variation in D0: ~ 10−8 cm2 s−1 for λ = 1, 2, and 4; 8.7 × 10−7 cm2 s−1 for λ = 8; and 4.9 and 7.3 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 for λ = 16, and 22, respectively. These orders of magnitude difference in D0 values explain the two thresholds observed: ξ = 8 for fresh FFPs, and ξ = 22 for oxidized FFPs. The relatively small gap in D0 between λ = 16 and 22 also accounts for the temporary stable operation at ξ = 16. 2D visualizations of H2O and H3O+ distribution (Fig. 4b−e) show that at λ < 22, the formation of isolated water clusters results in discontinuous water channels, impeding the H+ transport. As λ increases, these clusters expand and merge, ultimately forming continuous channels at λ = 22 that enable smooth H+ transport. This explains why stable operation can be achieved at ξ = 22 even with severely oxidized FFPs. To validate our MD calculations, we experimentally measured σ of PEM at different hydration states by controlling the relative humidity (RH) at specified temperatures17. As shown in Fig. 4f, the results confirm our simulation findings, showing about two orders of magnitude (84-fold) difference in σ of PEM between 100% RH (corresponding to λ = 22) and 10% RH (λ = 2).

a MSD vs time curve of H3O+ in Nafion under different λ. 2D number-density maps of H2O and H3O+ in the X-Y plane (0.2 nm thickness) at different λ: b 4, c 8, d 16, and e 22. f Experimentally determined PEM’s σ under different temperatures and RH. g I–V curves comparing experimental data with simulated results using σ under normal λ and water starved (λ = 2) conditions. The inset shows an enlarged view of the data for λ = 2. h Temperature distribution contours along the X-Y coordinate plane under different operating conditions, with water flow direction indicated by the blue arrow. The upper panel shows normal operating conditions at 100 A, while the lower panel shows water starvation conditions (λ = 2) at 10 V, 23 A. Prefix letter: A-anode, C-cathode; CH channel; PTL porous transport layer; CL catalytic layers.

Numerical simulations were conducted using a 3D single-channel model to describe both the electrochemical and thermal behaviors of the abnormal electrolyzer. Using σ under water saturation state (100% RH, λ = 22) as the input parameter, our model reproduced well the normal I–V curve (Fig. 4g). When σ is reduced by two orders of magnitude (10% RH, λ = 2), the performance deteriorates dramatically. The voltage reaches 1.705 V at 0.1 A cm−2 (2.5 A) and 10.0 V at 0.92 A cm−2 (23.0 A) (Fig. 4g insert). This poor performance state (23.0 A @ 10.0 V) closely matches our experimental observations at ξ = 2 (20–30 A @ 10.0 V). Subsequently, the temperature distribution across the channel cross-section was analyzed. Under normal state (Fig. 4h upper), the highest temperature (~ 80 °C) occurs in the PEM and CLs due to their highest impedance. The temperature gradually decreases in the surrounding components (PTLs, CHs and FFPs). In contrast, under ξ = 2 conditions, the reduced σ leads to severe Joule heating, resulting in temperature exceeding 150 °C in the PEM and CLs. Although higher temperatures can increase σ, when the temperature exceeds the water boiling point, extensive water vaporization results in dehydration of PEM, maintaining σ at a low level of 0.1 - 0.2 S m−1 (Fig. 4f). The CCH temperature reaches about 140 °C, consistent with our FBG sensors measurements. These simulation results indicate that the sudden performance deterioration and temperature spike under water starvation conditions originate from the significant decrease in PEM’s σ.

The final and important aspect is to elucidate how H2 - O2 mixing occurs through structural characterization. The evolution of MEA structure under water-starvation conditions was investigated by ex-situ X-ray computed tomography (CT) at different stages (3 separate MEAs, Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 14). Figure 5a shows the 3D visualization of the fresh MEA structure, with a volume rendering (upper) and ortho slices along XY (middle) and XZ (lower) planes. In ortho slices, the vertical stacking sequence of the MEA along the X-axis is rendered in different colors: red for anode PTLs (APTLs), yellow for anode CLs (ACLs), light blue for PEM, and blue for cathode CLs (CCLs). For the intermediate state (Fig. 5b), the MEA was operated under ξ = 2 until current fluctuation (3rd stage), after which the operation was terminated. While the volume rendered images still show the vertical stacking structure, a notable membrane thinning region of ~ 1 × 4 mm is observed. Notably, the width of this thinning area corresponds to the width of the FFP ribs (1 mm), suggesting a correlation between the local stress distribution and membrane destruction. With prolonged operation under ξ = 2 (Fig. 5c), the electrolyzer operation was terminated right before the short circuit (4th stage). The CT imaging reveals complete destruction of the membrane structure, accompanied with a burn-through hole of about 200 μm in the Ti-PTL. The membrane destruction region expanded beyond 2 mm, exceeding the width of FFP ribs. At last, after the deflagration, a perforation of 2-3 mm was found on the MEAs (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 15). These observations indicate that PEM thinning is the primary cause of H2 and O2 mixing, with the initial perforation occurring under the ribs.

a–c CT images showing the morphological evolution of MEA under water-starvation conditions, from fresh state through progressive PEM thinning to MEA perforation prior to deflagration. d In situ measurement of MEA microstrain variation during transition from normal operation to water-starvation condition. e, f TMA of Nafion N115 at 5 MPa: e probe displacement as a function of temperature, and f probe displacement vs time at different temperatures and pressures for 1 h, where the negative displacement values indicate progressive membrane thinning. g Schematic illustration of the PEM thinning and perforation mechanism.

To elucidate the reasons of PEM thinning, we analyzed both the in situ mechanical stress of PEM and its thermomechanical behaviors. The mechanical stress on the 3-in-1 MEA (PEM, ACL, and CCL) was tested by FBG sensors18, with a mildly oxidized FFP enabling accurate localization of the malfunction area (Fig. 5d). Under normal operating conditions (water-rich, 100 A), the MEA microstrain remains relatively stable between 400 – 480, with a slight increase due to PEM swelling. When switched to water-starvation conditions (ξ = 2), the microstrain surges to over 1000 after a 15 s delay. After maintaining this elevated level for 50 s, the microstrain decreases and continues to fluctuate around 800 until the short-circuit. This 2 – 3 folds increase in mechanical stress on MEA is likely due to thermal expansion of components as temperature rises (Supplementary Fig. 16a and Supplementary Note 6). To understand the effect of mechanical stress on the PEM, the thermomechanical analysis (TMA) was performed on Nafion 115. The temperature-dependent probe displacement curve (Fig. 5e) shows two distinct regions. An initial reversible compression around 60–80 °C corresponds to the membrane’s elastic deformation19, followed by a probe penetration between 130–160 °C, indicating a transition from glassy state to rubbery state20. Figure 5f shows the evolution of probe displacement over time at 5 MPa and two temperatures. At 80 °C, the probe displacement stabilizes at around -10 μm (115 μm thickness) after an initial drop, while at 150 °C, a dramatic penetration occurs, reaching approximately − 35 μm in 70 min. When the pressure is further increased 10 MPa at 150 °C, electrical conductivity measurements indicate a PEM penetration by PTL in 20 min (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Note 6). These results indicate that PEM perforation is governed by its intrinsic thermomechanical behaviors and occurs when external conditions (temperature and localized stress) exceed thresholds.

Based on these results, we can now clearly demonstrate the formation mechanism of the catastrophic localized deflagration in MEA (Fig. 5g). Under water starvation, PEM’s σ decreases by about two orders of magnitude. This causes a huge step in voltage and subsequent current reduction. This is the characteristic behavior of the 2nd stage. The excessive voltage beyond 1.48 V can generate large Joule heating, elevating the MEA temperature to above 150 °C. In this stage, vapor is electrolyzed instead of liquid water. The current fluctuation in the 3rd stage likely arises from the competition between vapor and O2 in the transport pathway. Under such temperature, PEM becomes rubbery and soft, where local mechanical stress causes its compression and thinning, particularly severe at the uneven oxidized FFP ribs. This thinning process eventually leads to PEM perforation and direct H2 and O2 mixing. The heat and catalysts (Ir and Pt) ignite the gas mixture and trigger the deflagration.

Safety precautions

Based on the above understanding of the deflagration mechanism, preventing water-starvation induced malfunction requires targeted optimization of key components, including BPPs, PTLs, and PEMs. For BPPs, the primary focus lies in the inlet design between main manifold and flow field. An internal channel structure, implemented by bridges or ducts (Fig. 6a), is recommended to prevent polymer sealing frame expansion. Some flow field designs of PEM water electrolyzer are borrowed from fuel cells (FCs), which require narrow, shallow and serpentine channels to prevent flooding, and facilitate gas accessibility21. In contrast, deep, wide channels with minimal turns are needed in the electrolyzer to ensure efficient water transportation and prevent local water starvation. For PTLs, hydrophilicity is essential for facilitating water transport from PTL to CL. In addition, the mechanical properties of PEM require special consideration in high-pressure stacks, where Ti-PTLs are employed on both anode and cathode sides. Yet, their high incompressibility can lead to uneven stress distribution and accelerate PEM thinning. In this regard, PTL design should focus on high thickness uniformity, surface flatness without warpage or bending, and optimized porosity or gradient pore structure to ensure homogeneous stress distribution and mechanical support. For PEMs, membrane thinning represents the current trend to meet U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) technical targets (3.0 A cm−2 @ 1.8 V). However, our study reveals that thinner PEMs are more susceptible to perforation followed by deflagration under water starvation (Fig. 6b). The incorporation of composite reinforcement layers (such as poly(ether ether ketone), PEEK) emerges as a promising strategy. This approach can enhance the mechanical robustness of thin PEM while maintaining high performance.

a Bridge-structured internal channel design between the main manifold and flow field in BPPs. b The V-t, i-t curves under ξ = 2 with Nafion NR212 membrane. c H2 in O2 and O3 in O2 concentration during water-starvation test (insert: O3 concentration in anode outlet water). d F- release rates during normal37 and water-starvation operations. e Long-term stack voltage response of a 5 kW PEM water electrolysis stack (31-cells, 98 cm2) under 3.0 MPa differential pressure with fluctuating power input. f Individual cell voltage profiles in this stack during the final 30 h operation, showing normal operation of 30 cells (black lines) and sudden voltage increase in one abnormal cell (red line).

In addition to component optimization, real-time monitoring of stack operating parameters is necessary for preventing potential deflagration events. Cell voltage monitoring (CVM) is the most effective method22. Specifically, for large-scale stacks with hundreds of cells, monitoring only the stack voltage (Vstack) proves inadequate, as a large pre-malfunction increase of ~ 10 V translates to only 0.1 V per cell, a minimal variation that is easily overlooked. In contrast, CVM can capture sudden voltage spikes, providing warning signals for operators and researchers.

For scenarios where CVM is impractical, alternative strategies are proposed. Contrary to conventional understanding, PEM thinning does not lead to increased H2 crossover into O2 (H2 in O2). Instead, a decrease in H2 in O2 is observed. This phenomenon can be explained as follows. H2 transport primarily occurs through water channels in PEM via diffusion or convection pathways23. However, during water starvation, these water channels become discontinuous. H2 is then forced to transport through C-F chains with lower diffusion coefficients, resulting in reduced H2 crossover. Notably, significant O3 generation is observed in the O2 stream, with concentration exceeding the sensor’s detection limit (10 ppm, about 21.4 mg m−3). O3 is also present in the anode outlet water at a concentration of 0.15 mg L−1. This O3 formation can be attributed to the electrolysis voltage exceeding the theoretical O3 evolution potential of 2.075 V24. Even when considering dilution effects in large-scale stacks (assuming 100 cells), the O3 concentration (about 0.2 mg m−3) remains above the WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines threshold (0.1 mg m−3). The presence of O3 inevitably triggers chemical degradation of PEM through unzipping mechanism25, leading to F- release. The F- release rate in the anode rises by more than 500-fold, and the total shows more than 50-fold elevation (Fig. 6d). Therefore, either monitoring O3 with ppb-resolution O3 sensors or monitoring F- content with F- electrode in anode outlet gas / water can serve as effective early warning strategies for preventing such events.

Subsequently, we conducted a durability study of a differential pressure (3.0 MPa) 5 kW PEM water electrolysis stack under fluctuating power input. The test protocol included start-stop cycles, load ramping, overload (150% nominal load, 1.5 A cm−2), and low-load (5% nominal load, 0.05 A cm−2), with CVM introduced for safety monitoring. During ~ 330 h operation, Vstack shows no apparent abnormalities (Fig. 6e). For instance, at 190 h, Vstack reaches 56.7 V at 1.5 A cm−2, which is in the normal operating range. Similarly, during the final 30 h, Vstack of 56.8 V at 1.5 A cm−2 is less than 1 V higher than the normal operating voltage. However, individual cell monitoring reveals that one cell voltage surge to 2.56 V (1.5 A cm−2) at 306 h. During the subsequent operating cycle, as the current density ramped up from 1.0 to 1.5 A cm−2, this cell voltage continues to increase. Such abnormal cell voltage could lead to H2 - O2 deflagration since the stack would forcibly maintain the set current without automatic shutdown. To prevent potential deflagration events, we immediately stopped the stack operation. The potential deflagration in differential pressure stacks would be catastrophic, as the 3.0 MPa H2 would create a high-velocity jet flow toward the anode side, presenting higher risks compared to atmospheric pressure stacks.

Finally, while the proposed safety precautions represent potential solutions to address the identified deflagration risks, their practical implementation involves several considerations. For performance impact, BPPs and PEMs are indeed critical performance-determining factors. Regarding bridge-structured internal channel in BPPs, through proper structural design, the contact resistance and flatness at bridging regions can be maintained consistent with other areas26, thereby avoiding performance degradation. Regarding PEM modifications, while the incorporation of reinforcement layers may reduce σ, the greater σ enhancement from reduced membrane thickness results in a net performance improvement. This is exemplified by Gore’s M275.80 membrane27, an 80 μm thick membrane with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) reinforcement layers that achieves superior performance and mechanical stability compared to conventional PEM. The external monitoring facilities (CVM, O3 sensor and F- sensor) operate independently of the stacks and therefore do not impact the electrochemical performance. For cost considerations, implementation of the aforementioned safety precautions inevitably increases system cost due to additional sensors and sampling pipelines. However, these investments are justified by the substantial enhancement in operational safety, particularly considering the potential damage to stacks in industrial-scale systems.

For electrolysis system complexity and feasibility, bridge-structure design and CVM detection have been widely used in FCs, making them straightforward to adopt with established technical maturity28. CVM implementation requires an electrical interface on BPPs, which can be achieved through electrode tabs or socket connections for CVM linkage (Supplementary Fig. 19a). In contrast, O3 and F- sensors introduce greater system complexity due to the rapid onset of voltage spikes, which occur in seconds to minutes. These sensors must be positioned close to the stack anode outlet to ensure detection timeliness. This necessitates sampling points at anode outlets with pumping systems to deliver small water samples to sensors, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 19b. For O3 detection, electrochemical methods using Au electrodes enable reliable online detection in O2- and H2- (crossover from cathode) environments29. F ion selective electrode (F-ISE) provide rapid F- detection in flowing water by generating a potential difference between the F-ISE and reference electrode30. The output potential is proportional to F- concentration in solution, with the potential difference depending on the F- activity. These sensors ensure technical feasibility for real-time monitoring. However, both O3 sensor and F-ISE contain internal electrolytes and ion-selective membranes, requiring periodic electrolyte replenishment due to long-term leakage during continuous operation.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive investigation into the catastrophic deflagration mechanism in PEM water electrolyzers (stacks) and establishes effective safety precautions. Analysis of malfunctioned stacks reveals that anode flow field obstruction, leading to water starvation, is the primary trigger for these events. Experimental investigations in a PEM single electrolyzer under various water-starvation conditions successfully reproduce and capture the complete deflagration process. Critically, a minimum water stoichiometric ratio (≥ 22) is established as essential for risk-free operation, even with flow field plates that have experienced prior deflagration damage.

Multimodal characterizations combined with multiscale modeling and simulation reveal that water starvation conditions trigger a dramatic decrease in PEM H+ conductivity by two orders of magnitude, leading to excessive Joule heating and temperature elevation to above 150 °C in MEAs. This elevated temperature induces PEM glass transition, causing membrane softening and subsequent thinning under mechanical stress, particularly severe at oxidized FFPs ribs. The progressive membrane deterioration ultimately results in direct H2 - O2 mixing and ignition, leading to catastrophic deflagration.

To mitigate these risks, we propose several preventive design guidelines and future developing direction of key components. These include the implementation of internal channel structures in BPPs to prevent sealing frame expansion, optimization of flow field design, and development of composite PEMs. Equally important is the implementation of real-time monitoring strategies. Individual cell voltage monitoring proves most effective for early detection of abnormalities, and O3 and F- concentration detection in the anode outlet also serves as reliable warning indicators. The effectiveness of these safety precautions has been validated through long-term testing of a 5 kW stack under 3.0 MPa differential pressure operation. Our findings demonstrate an essential difference in single-cell voltage anomalies between the PEM water electrolysis and fuel cell (FC) stacks under abnormal conditions. In FCs, decreased PEM H+ conductivity or insufficient reactant supply leads to cell voltage dropping to 0 V or cell reversal, which poses minimal safety risks due to low voltage and H2 consumption. However, when abnormal conditions (either water starvation or other factors) occur in PEM water electrolysis, the power supply forcibly maintains the set current, resulting in excessive cell voltage that can trigger an explosion.

This work provides both the fundamental understanding of deflagration mechanisms in PEM water electrolysis and establishes guidelines for materials design and stacks operation. More broadly, this work bridges the gap between lab research and industrial implementation, establishing a robust foundation for the safe scale-up of PEM water electrolysis in industrial H2 production.

Methods

Electrolyzer assembly

For the single electrolyzer testing, commercial MEA with an active area of 25 cm2 (5 × 5 cm) was purchased from BriHyNergy Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China), and MEAs with an active area of 100 cm2 (10 × 10 cm) were purchased from Shaanxi Xingran Technology Co., Ltd. (Shaanxi, China). For the 4-cell PEM water electrolysis stack, MEAs were fabricated in-house using the ultrasonic spray coating method. The occurrence of deflagration incidents with MEAs from different manufacturers indicates the widespread nature of this safety concern. The MEA was fabricated using Nafion N115 or NR212 membrane (Chemour, US), with Pt/C catalyst at the cathode (mass loading of 0.2 – 0.4 mgPt cm−2), and IrO2 at the anode (mass loading of 0.7 – 1.5 mgIr cm−2). The PTLs employed sintered Ti fiber felts (56% porosity, Bekepor, Bekaert) for the anode and carbon paper (H24CX483, Freudenberg) for the cathode, both featuring a thickness of 250 µm. These components were integrated through hot-pressing at 140 °C under 6.0 MPa for 10 min to form a 5-in-1 MEA. For routine performance tests and water-starvation-induced deflagration studies, the 5-in-1 MEA was sandwiched between two Ti plates with a parallel flow field. For the visual deflagration experiments, the observation side (either anode or cathode) used a 1 mm-thick Ti sheet with openwork serpentine flow channels and a transparent quartz backing plate for MEA encapsulation, while the opposite side utilized Ti plates with a serpentine flow field.

Electrolyzer performance test

The electrochemical measurements were conducted on a homemade test station comprising a DC power supply (NGI, China) to obtain I-V and V-t curves. Before each test, DI water at 80 °C was pumped into the electrolyzer at a flow rate of 100 mL min−1 until thermal equilibrium was achieved. The I-V curves were recorded under galvanostatic mode with incremental current density steps: 0.05 A cm−2 intervals from 0.05 to 0.5 A cm−2, followed by 0.1 A cm−2 intervals from 0.5 to 3.0 A cm−2. The data were collected for 30 s at each step. To simulate the high current operations in PEM water electrolysis stacks, V-t curves were tested at 100 A (4.0 A cm−2) with an upper voltage limit of 10 V for a maximum duration of 5 h. For the water-starvation-induced deflagration experiment, the electrolyzer was firstly operated under routine conditions (feed water flow rate: 100 mL min-1) for a period, after which the flow rate was suddenly decreased to specified stoichiometric ratio (ξ) as determined by Eqs. (1–3). The corresponding flow rate were 1.12, 2.24, 3.36, and 4.48, et al. mL min−1 for ξ = 2, 4, 6, and 8, et al., respectively.

Where nH+ is the theoretical mole amount of H+ transport at 100 A in 1 min; I is the applied current (100 A); t is the time duration (60 s); z is the electron transfer number (1); F is the Faraday constant (96485 C mol−1); ξ is the feed water stoichiometric ratio; nwater is the mole amount of feed water; Fl is the feed water flow rate during water-starvation experiment (mL min-1); mwater is the mole weight of water (18.0 g mol−1); ρwater is the density of water (1.0 g mL−1).

Molecular dynamics simulation

The MD simulations of hydrated Nafion 115 were performed based on its chemical structure reported by literatures14, and the Nafion monomer is shown in Supplementary Fig. 12a. The monomer was polymerized with a degree of polymerization of 20 to construct the polymer chains (Supplementary Fig. 12b), maintaining an ion exchange capacity of about 0.90 meq g−1. The atomic charges of polymer structure were calculated by the CP2K 2024.2 package31, employing the all-electron Gaussian-Augmented Plane Wave (GAPW) method with the 6-311 G** basis set and Grimme D3(BJ) dispersion correction.

All MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2023.4 package32. A series of cubic boxes with periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were constructed, each containing 20 Nafion polymer chains at different hydration levels (λ). The optimized box dimensions were 7.613, 7.696, 7.956, 8.445, and 8.801 nm for λ values of 2, 4, 8, 16, and 22, respectively. To maintain charge neutrality, 400 hydronium ions (H3O+) was incorporated into each simulation box. The force field parameters for H3O+ were adopted from reported work33. The general Amber force field (GAFF) was used to describe Nafion polymer chains34,35, while the TIP3P model was used for water molecules. The simulation protocol consisted of three stages: (1) energy minimization by conjugate gradient algorithm, (2) equilibration for 2 ns, and (3) production run for 2 ns. Both equilibrium and production phases were conducted in the NPT ensemble at 353 K and 1 bar, maintained by Nosé-Hoover thermostats and C-rescale barostats, respectively. The trajectories were analyzed to obtain structural properties, diffusion coefficients (D0) and radial distribution functions (RDF) of the system components.

Numerical simulation

A three-dimensional (3D) single-channel PEM water electrolysis model was developed, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 13. The model comprises 9 distinct computational domains arranged in sequence from anode to cathode: anode flow field plate (AFFP), anode flow channel (ACH), anode porous transport layer (APTL), anode catalytic layer (ACL), proton exchange membrane (PEM), cathode catalytic layer (CCL), cathode porous transport layer (CPTL), cathode flow channel (CCH), and cathode flow field plate (CFFP). The parameters used for model validation were listed in Supplementary Table 2. Several well-established assumptions were implemented to simplify the governing equations (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4) while maintaining computational accuracy: (1) The model operates under steady-state conditions; (2) The flow is considered laminar and incompressible; (3) The PTLs, CLs, and PEM are assumed to be homogeneous and isotropic materials; (4) The effects of gravity and gas crossover are negligible.

The numerical simulations were performed using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0, where the computational domain was discretized by the hexahedral mesh elements. The relative residuals were set to 1 × 10−4 for all variables. A segregated approach combined with a direct solver based on PARDISO was employed to solve the governing equations. The solution procedure first solved the gas-liquid flow and energy equations to obtain the velocity fields, mass fractions, and temperature distributions. Subsequently, the electrochemical model was solved. The results were achieved through successive iterations until model convergence was reached.

Characterizations

The deflagration in the PEM water electrolyzer was recorded by a high-speed camera system (X190C, Revealer, China) at 1000 frames per second over a 2 min period. The temperature and strain of the MEAs were measured by fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors coupled with an optical spectrum analyzer (HKS-F100, JIUYOU, China). The specific installation locations of the sensors are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. A digital microscope (DSX1000, OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to examine the surface morphology of Ti-based flow field plates. Surface roughness parameters Rq and Sq were evaluated along a line and a rectangular area, respectively, according to Eqs. (7, 8). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis was performed by a Talos F200X G2 microscope (Thermo Scientific, US) at 200 kV, equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, super-X) for elemental mapping. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were obtained using Quattro S equipment (Thermo Scientific, US) at 20 kV, coupled with an EDS system (EDAX ELECT PIUS) for elemental analysis. The proton conductivity of PEM was tested using a fuel cell test station (C100, Kewell, China) coupled with an electrochemical workstation (Zennium Pro, Zahner, Germany). The measurements were conducted under two temperature conditions: 70 °C with relative humidity of 10%, 50% and 100%, and 150 °C with relative humidity of 10%. The EIS was performed under the potentiostatic mode at open circuit potential with an AC amplitude of 0.1 V. The frequency range was set from 100 kHz to 1 Hz for all measurements. The thermal compression of Ti-PTL/PEM components was conducted using Carver 3889.4PL1 (US). The F- concentration in both anode and cathode outlet water was determined by ion chromatography (ICS-600, Thermo Scientific, US). The contact resistance of FFPs was performed by a resistance measurement equipment (FT-541SJB-341, Rooko, China). Thermomechanical analysis (TMA) was conducted using a PerkinElmer TMA4000 equipped with a penetration probe. The membrane was subjected to static loads of 5 MPa and heated at rates of 2 or 10 °C min−1. The ultra-thin cross-sections of MEA were prepared using an ultramicrotome (Leica UC 7).

where l is the sampling line length; A is the sampling area; and Z is the height at specified coordinates (x) or (x, y).

The 3D structural characterization of MEAs was conducted by X-ray computed tomography (CT, Xradia 620 Versa, ZEISS, Germany). The scanning parameters were set at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV and a power of 10 W. The sample dimensions were ~ 3.85 (l) × 3.72 (w) × 0.40 (h) mm, ~ 3.79 (l) × 3.61 (w) × 0.45 (h) mm, and ~ 3.65 (l) × 4.53 (w) × 0.46 (h) mm for the fresh MEA (A), the MEA at intermediate state (B), and the MEA terminated right before the short circuit (C), respectively (non-uniform thickness caused by MEA deformation under high temperature conditions for samples B and C). The corresponding scanning field of view dimensions were 4.01 × 4.10 × 4.06 mm, 4.20 × 4.28 × 4.23 mm, and 4.02 × 4.11 × 4.06 mm, respectively, with a voxel size of 2.001 µm, 2.090 µm, and 2.006 µm for the three samples. All samples consisted of APTLs (Ti fiber felts), ACLs, PEM, and CCLs. The CPTL (carbon paper) was not included in the analysis as this layer was damaged during cell disassembly. To maintain consistent detection signals above 5000 counts across all samples, different exposure times and filters were employed. MEA A was scanned using an exposure time of 2 s per projection with the LE1 filter, totaling 1201 projections. MEA B was scanned using an exposure time of 1 s per projection with LE3 filter over 1201 projections, while MEA C required an exposure time of 4 s per projection with LE1 over 1201 projections. LE1 or LE3 filters were used for suppressing beam hardening effects. Post-processing and 3D visualization were performed using Avizo software with a temperature colormap to represent X-ray attenuation intensity. The color scale ranges from white (low attenuation) to yellow (high attenuation), providing intuitive correlation between material density/atomic number and visual representation. PEM, composed primarily of C and F elements, exhibits low attenuation and is displayed in light blue. CCLs containing Pt/C composite show moderate attenuation and appear in blue. APTLs made of Ti demonstrate high attenuation and is displayed in red. ACLs based on IrO2 exhibits the highest attenuation due to Ir (Z = 77) and appears in yellow.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source Data file has been deposited in Figshare under accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3000625636.

References

Bourzac, K. Renewable hydrogen is having a moment. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 179–181 (2024).

Kong, S. et al. Acid-stable manganese oxides for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nat. Catal. 7, 252–261 (2024).

IEA. Global Hydrogen Review 2024. (2024).

Li, A. L. et al. Atomically dispersed hexavalent iridium oxide from MnO2 reduction for oxygen evolution catalysis. Science 384, 666–670 (2024).

Qelibari, R. et al. 74 μm PEEK-Reinforced sulfonated poly(phenylene sulfone)-membrane for stable water electrolysis with lower gas crossover and lower resistance than Nafion N115. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303271 (2024).

Schuler, T. et al. Ultrathin microporous transport layers: implications for low catalyst loadings, thin membranes, and high current density operation for proton exchange membrane electrolysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2302786 (2024).

Kumamoto, A., Iseki, H., Ono, R. & Oda, T. Measurement of minimum ignition energy in hydrogen-oxygen-nitrogen premixed gas by spark discharge. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 301, 012039 (2011).

Mao Z. Q. Hydrogen Safety. (Chemical Industry Press Co. Ltd., 2020).

Singh, Y., Orfino, F. P., Dutta, M. & Kjeang, E. 3D Failure analysis of pure mechanical and pure chemical degradation in fuel cell membranes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, F1331–F1341 (2017).

Millet, P., Ranjbari, A., de Guglielmo, F. & Grigoriev, S. A. Auprêtre F. Cell failure mechanisms in PEM water electrolyzers. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 37, 17478–17487 (2012).

David, N. A., Wild, P. M., Jensen, J., Navessin, T. & Djilali, N. Simultaneous in situ measurement of temperature and relative humidity in a PEMFC using optical fiber sensors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1173–B1179 (2010).

Scheepers, F. et al. Temperature optimization for improving polymer electrolyte membrane-water electrolysis system efficiency. Appl. Energy 283, 116270 (2021).

Arntsen, C., Chen, C., Calio, P. B., Li, C. H. & Voth, G. A. The hopping mechanism of the hydrated excess proton and its contribution to proton diffusion in water. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 194506 (2021).

Xiao, J. Y., Yan, D., Li, J., Li, Q. & Sun, H. Hydronium ions diffusion behavior in nafion membrane by mesoscopic simulation. AIP Adv. 8, 075303 (2018).

Sel, O. et al. Determination of the diffusion coefficient of protons in Nafion thin films by ac-electrogravimetry. Langmuir 29, 13655–13660 (2013).

Zawodzinski, J.rT. A., Springer, T. E., Uribe, F. & Gottesfeld, S. Characterization of polymer electrolytes for fuel cell applications. Solid State Ion. 60, 199–211 (1993).

Ochi, S., Kamishima, O., Mizusaki, J. & Kawamura, J. Investigation of proton diffusion in Nafion®117 membrane by electrical conductivity and NMR. Solid State Ion. 180, 580–584 (2009).

Botsis, J., Humbert, L., Colpo, F. & Giaccari, P. Embedded fiber Bragg grating sensor for internal strain measurements in polymeric materials. Opt. Lasers Eng. 43, 491–510 (2005).

Ueda, E., Okada, H. & Kato, R. Mechanical durability of water electrolysis membranes in a liquid environment under differential pressure mode. ECS Meet. Abstr. MA2024-02, 2909 (2024).

De Almeida, S. & Kawano, Y. Thermal behavior of Nafion membranes. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 58, 569–577 (1999).

Wen, D. H. et al. Performance investigation of proton exchange membrane fuel cell with intersectant flow field. Int. J. Heat. Mass Tran. 121, 775–787 (2018).

Webb, D. & Møller-Holst, S. Measuring individual cell voltages in fuel cell stacks. J. Power Sources 103, 54–60 (2001).

Trinke, P., Bensmann, B., Reichstein, S., Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. & Sundmacher, K. Hydrogen permeation in PEM electrolyzer cells operated at asymmetric pressure conditions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, F3164–F3170 (2016).

Kim, S. et al. Tuning electrochemical water oxidation towards ozone evolution with heterojunction anode architectures. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 17132–17141 (2022).

Zhou, C., Guerra, M. A., Qiu, Z. M., Zawodzinski, T. A. & Schiraldi, D. A. Chemical durability studies of perfluorinated sulfonic acid polymers and model compounds under mimic fuel cell conditions. Macromolecules 40, 8695–8707 (2007).

Li, X. & Sabir, I. Review of bipolar plates in PEM fuel cells: Flow-field designs. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 30, 359–371 (2005).

Data Sheet: GORE® PEM for Water Electrolysis https://www.gore.com/resources/data-sheet-pem-for-water-electrolysis (Gore, 2024);

Bubna, P., Brunner, D., Gangloff, J.rJ. J., Advani, S. G. & Prasad, A. K. Analysis, operation and maintenance of a fuel cell/battery series-hybrid bus for urban transit applications. J. Power Sources 195, 3939–3949 (2010).

Aoki, K., Kobayashi, A. & Kato, N. Amperometric determination of ozone in water at disposable graphite reinforcement carbon electrodes. Electroanalysis 2, 31–34 (1990).

Arnold, M. A. & Meyerhoff, M. E. Ion-selective electrodes. Anal. Chem. 56, 20–48 (1984).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package - Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25 (2015).

Noroozi, J. & Smith, W. R. Force-field-based computational study of the thermodynamics of a large set of aqueous alkanolamine solvents for post-combustion CO2 capture. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 4497–4513 (2021).

Lu, T. Sobtop: a tool of generating forcefield parameters and GROMACS topology file. http://sobereva.com/soft/Sobtop (2024).

Wang, J. M., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Tan, A. D. et al. Catastrophic localized deflagration formation mechanisms and safety precautions in proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer, Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30006256 (2025).

Rui, Z. Y. et al. A new insight into the chemical degradation of proton exchange membranes in water electrolyzers. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 9563–9573 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFB4000100 received by J.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. conceived the project, designed the experimental methodology, performed MD simulations, and wrote the manuscript. J.S. conducted most of the experimental operations and material characterization. X.Q. performed experimental operations (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3, and 18). Z.L. carried out COMSOL simulations and calculations. L.X. created the schematic illustrations in the manuscript. C.J. conducted data analysis. F.Z. and G.L. performed 100 kW electrolyzer stack analysis. X.S. conducted TEM analysis. T.L. performed membrane stress analysis. P.L. performed electrolyzer stack analysis. J.L. provided funding support and overall project supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Laura Dalton and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, A., Song, J., Qiu, X. et al. Catastrophic localized deflagration formation mechanisms and safety precautions in proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Nat Commun 16, 9115 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64162-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64162-y