Abstract

Solar-driven H2O2 production provides an eco-friendly and scalable alternative to conventional anthraquinone processes. However, its efficiency has been limited by the inefficient charge separation and poor selectivity for the two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (2e- ORR). Here we report a Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst constructed by in-situ growth of sulfur-deficient ZnIn2S4 nanosheets onto UiO-66-NH2 (a zirconium-based metal-organic framework). This heterojunction promotes efficient charge separation while retaining strong redox capability, and sulfur vacancies regulate O2 adsorption into a configuration that suppresses O-O bond cleavage and favors 2e- ORR. As a result, the composite achieves a high H2O2 production rate of 3200 μmol g-1 h-1 with 94.3% selectivity in pure water under ambient air and visible light. A continuous-flow prototype exhibits stable performance for over 200 h, and the generated H2O2 solution enables direct bacteria disinfection. Spectroscopic and theoretical analyses reveal the critical role of sulfur vacancies in optimizing O2 activation. Our findings highlight a synergistic strategy of tuning charge dynamics and O2 adsorption configurations for designing next-generation systems for sustainable H2O2 production and water disinfection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

H2O2 is a crucial green oxidant, widely used in chemical synthesis, wastewater treatment, and disinfection1,2. However, conventional anthraquinone-based production method suffers from high energy consumption, environmental pollution, and safety concerns3,4,5. To circumvent these issues, solar-driven photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis from O2 and H2O offers a more energy-efficient, greener, and safer alternative6,7,8.

Photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis occurs via O2 reduction reaction (ORR) and/or water oxidation reaction (WOR) by photogenerated electrons (e-) and holes (h+), respectively. The 2e- ORR (O2 + 2e- + 2H+ → H2O2, 0.68 V vs reversible hydrogen electrode, RHE) is more favorable both thermodynamically and kinetically than WOR (2H2O + 2 h+ → H2O2 + 2H+, 1.76 V vs RHE)9. While hole scavengers are often used to bypass the rate-limiting WOR and enhance charge separation10, they introduces additional costs, secondary pollution, and difficult post-purification11,12. Thus, achieving H2O2 photosynthesis in pure water without sacrificial agents is highly desirable13.

Z-scheme photocatalysts, which are known for their efficient charge separation and strong redox capabilities, enable both ORR and WOR in pure water without adding hole scavengers14,15,16,17. ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) is a competent reductive semiconductor of the Z-scheme heterojunction due to its negative conduction band (CB) edge and strong ORR activity18. However, ZIS suffers from photo-corrosion due to oxidation by accumulated photogenerated h+ and rapid charge carrier recombination. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), a class of crystalline coordination materials, have gained attention as promising photocatalysts for H2O2 production19,20. Their porous structure and abundant channels provide large surface areas and facilitate efficient mass transfer of reactants and products, enhancing H2O2 photosynthesis. Among MOFs, UiO-66-NH2 (U6N) stands out for its visible-light absorption21, high structural stability22, and favorable band positions for forming Z-scheme heterojunctions with ZIS (Fig. 1a). The construction of Z-scheme heterojunction can spatially separate e- and h+ on ZIS and U6N, respectively, largely suppressing charge recombination and photo-corrosion. However, studies on U6N-based photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis remain scarce.

Although Z-scheme heterojunctions improve charge separation and redox capability, the competition between 2e- and 4e- ORR (O2 + 4H+ + 4e- → 2H2O) is crucial and often overlooked23. The 4e- ORR produces H2O instead of H2O2, so achieving high 2e- ORR selectivity is critical24, which highly depends on O2 adsorption configurations25,26. Yeager-type (side-on) and Pauling-type (end-on) are two main O2 adsorption configurations (Fig. 1b)27,28,29. For Yeager-type adsorption, two active sites transfer electrons to oxygen’s p orbitals, fully occupying its π* antibonding orbitals to form peroxide (•O22-) intermediate and destabilize O-O bonds (Fig. 1b, c). This configuration thus favors O-O bond cleavage into •OH radicals, hindering H2O2 synthesis due to the high energy barrier for •OH coupling30. In contrast, Pauling-type adsorption favors superoxide (•O2-) formation by partially filling the π* antibonding orbitals, preserving O-O bond. The protonation of •O2- forms •OOH, a major 2e- ORR intermediate, facilitating H2O2 production31. Therefore, tuning the O2 adsorption to Pauling-type is key to enhancing the selectivity and efficiency of H2O2 photosynthesis32,33.

Unfortunately, each O atom in O2 donates two electrons for bonding, leaving two unpaired electrons that favor Yeager-type adsorption on two adjacent Zn atoms in ZIS. Heteroatom doping or defect engineering can disrupt the charge balance of neighboring active sites, enhancing electron delocalization and tuning O2 adsorption configuration toward the Pauling-type. Recent studies have demonstrated the achievement of Pauling-type O2 adsorption for H2O2 photosynthesis in carbon nitride24,34,35,36,37,38, covalent organic frameworks39,40, and chalcogenides41,42 via heteroatom doping, single-atom and functional-group modifications. For example, Liu and Yu et al. introduced highly dispersed single-atom Ni sites to ZnS to realize the Pauling-type O2 adsorption, which showed enhanced H2O2 photosynthesis under UV-visible light42. We thus hypothesize that introducing S vacancies in ZIS can increase the electron density of one proximate Zn while leaving the other one unaffected. This electronic imbalance allows dual Zn sites to transfer different numbers of electrons to the two O atoms, shifting the O2 adsorption from Yeager-type to the desired Pauling-type configuration.

Herein, we developed a Z-scheme heterojunction by in situ growing S-deficient ZIS onto U6N (U6N@ZIS), boosting charge transfer and retaining the strong redox capability for enhanced ORR performance. Both experimental data and density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed that S vacancies in ZIS induced Pauling-type O2 adsorption, improving 2e- ORR selectivity. As a result, U6N@ZIS exhibited a very high H2O2 production rate (3200 µmol g−1 h−1) in pure water with ambient air exposure under visible light irradiation. Moreover, the developed continuous-flow prototype demonstrated long-term stability (>200 h), and the generated solution was directly usable for on-site water disinfection without the need for further purification.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations of U6N@ZIS

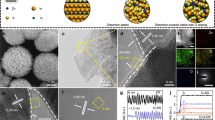

U6N was synthesized through a facile solvothermal method, followed by the in-situ growth of ZIS nanosheets to obtain U6N@ZIS (Fig. 2a). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images revealed the discernible octahedral morphologies of U6N with sizes of 400~600 nm (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.32 nm were clearly observed in the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image (Fig. 2c), well indexed to the (102) planes of hexagonal ZIS43. SEM images of U6N@ZIS showed a nanosheet structure at the periphery (Supplementary Fig. 3). High-angle annular dark field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mappings confirmed the core@shell structure of U6N@ZIS. The Zr distribution was confined to a smaller area and covered by uniformly distributed Zn, In, and S elements, indicating the encapsulation of U6N by the in-situ grown ZIS (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 5). U6N@ZIS showed a large specific surface area and porosity based on the gas adsorption-desorption analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6), favoring O2 adsorption for efficient 2e- ORR. X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of U6N@ZIS showed diffraction peaks attributed to both U6N and hexagonal ZIS, confirming the successful synthesis of U6N@ZIS (Supplementary Fig. 8). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of U6N and U6N@ZIS showed the characteristic stretching and bending vibrations of -NH2, benzene ring, and Zr-O bonds (Supplementary Fig. 9)44,45,46. X-ray photoelectron spectrometry (XPS) analysis revealed a 0.1-0.2 eV shift of S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2 peaks towards higher binding energy in U6N@ZIS compared to ZIS. Conversely, Zr 3d3/2 and Zr 3d5/2 peaks shifted to lower binding energy in U6N@ZIS compared to U6N (Fig. 2e, f). These results suggested electron transfer from ZIS to U6N upon contact, leading to Fermi level equilibrium and the establishment of an interfacial electric field (IEF) directed from ZIS to U6N47. The formed IEF provides a driving force to steer the photoexcited electron transfer from U6N to ZIS, following the Z-scheme direction under illumination.

a Schematic illustration of synthesizing U6N@ZIS. “Three-neck flask and octahedron images” adapted from BioRender. Liu, F. (2025). b SEM image of U6N. c HRTEM and d EDS mappings of U6N@ZIS. e S 2p and f Zr 3 d XPS spectra. g Zn K-edge XANES profiles and h Fourier transformation of EXAFS for Zn foil, ZnO, ZIS, and U6N@ZIS. i EPR spectra of ZIS, UiO@ZIS, and U6N@ZIS. Scale bars: b, d 200 nm, c 10 nm. Source data for e, f and g–i are provided as a Source Data file.

X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) analysis of the Zn K-edge was performed to discern the nuanced electronic structure differences between ZIS and U6N@ZIS. As shown in Fig. 2g, the Zn K-edge in U6N@ZIS exhibited a negative shift of 0.29 eV relative to ZIS, indicating the presence of S-vacancy in U6N@ZIS48,49. Further insights into the local coordination environment of U6N@ZIS were obtained through the Fourier transform of extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Fig. 2h). U6N@ZIS exhibited a decreased peak intensity at ~1.87 Å compared to pristine ZIS, suggesting a lower Zn-S coordination environment14,50. Detailed EXAFS fitting further revealed a reduced Zn-S coordination number in U6N@ZIS (2.7) compared to ZIS (3.0), providing direct evidence for the presence of S-vacancies in U6N@ZIS (Supplementary Table 2)51,52. Moreover, wavelet transform analysis of the EXAFS spectra offered a clearer visualization of the Zn-S coordination structures in ZIS and U6N@ZIS (Supplementary Fig. 11). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis further corroborated the presence of S vacancies in U6N@ZIS, revealing a characteristic signal with a g-value of 2.004 (Fig. 2i). Notably, S vacancies disrupt electron localization at Zn sites, favoring Pauling-type O2 adsorption and enhancing the 2e⁻ ORR selectivity.

To unveil the mechanism of S vacancy formation, we conducted In K-edge EXAFS to examine the potential interaction between ZIS and U6N. The fitting results revealed distinct In-N coordination in U6N@ZIS (Supplementary Figs. 12, 13 and Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, DFT calculations provided an optimized theoretical model of the U6N@ZIS composite. Strong interactions between U6N and ZIS were observed, with the formation of In-N bonds having a bond length of 2.17 Å (Supplementary Fig. 14), consistent with the results of EXAFS analysis. We thus proposed that the formation of S vacancies arose from the interactions between -NH2 groups of NH2-UiO-66 and In3+ precursors during the in-situ growth of ZIS, influencing the nucleation and growth processes. These interactions could lead to non-stoichiometric growth, resulting in the formation of S vacancies in the ZIS lattice. Additionally, the electron-donating nature of -NH2 groups can alter the local electronic environment, further promoting the creation of S vacancies. To verify the role of -NH2 group, we prepared ZnIn2S4 in the presence of UiO-66 without -NH2 (UiO@ZIS). No S vacancy signal was detected by EPR analysis (Fig. 2i), further substantiating the proposed mechanism for S vacancy formation. It is noted that the demonstration related to U6N-induced S vacancy formation of ZnIn2S4 has not been reported yet.

Photocatalytic H2O2 production in pure water by U6N@ZIS

Photocatalytic H2O2 production by the as-prepared samples was undertaken under visible light irradiation in pure water (Fig. 3a). U6N@ZIS achieved a significantly higher H2O2 production of 0.32 mM after 60 min, which was 12 and 8 times higher than that of pristine U6N (0.02 mM) and ZIS (0.04 mM), respectively. The enhanced performance could be attributed to the heterojunction formation, which facilitated the interfacial charge separation and transfer, suppressing charge recombination.

a Photocatalytic H2O2 production by ZIS, U6N and U6N@ZIS. Reaction conditions: 1 mg photocatalyst, 10 mL H2O, λ > 400 nm. b kf and kd of U6N, ZIS, and U6N@ZIS. c AQY for H2O2 production of U6N@ZIS under monochromatic light irradiation of different wavelengths (365, 420, 500, 560, and 660 nm). d Comparison for H2O2 production with representative photocatalysts in recent works. e On-site inactivation of E. coli using H2O2 solution generated at different irradiation times. f, g Continuous-flow reactor for H2O2 production. h Long-term and continuous H2O2 production. Source data for a–c and e are provided as a Source Data file.

The U6N loading content was optimized to 40 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 16), and pH 7 was the optimal condition for H2O2 photosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. 17), which were therefore employed in subsequent experiments. The final H2O2 yield is governed by both formation rate (kf) and decomposition rate (kd), which were derived by assuming zero-order and first-order kinetics, respectively. U6N@ZIS showed the highest kf and lowest kd, indicating its high overall H2O2 yield (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 4). The apparent quantum yield (AQY) of U6N@ZIS for H2O2 photosynthesis was further measured under different-wavelength monochromatic light irradiation. AQY values of 13.9%, 12.0%, 5.8%, 3.5% and 2.0% were achieved at 365, 420, 500, 560, and 660 nm of irradiation, respectively. This trend closely followed the absorption spectrum of U6N@ZIS, confirming that H2O2 production is a light-driven process (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 5). Notably, the performance of U6N@ZIS is competitive in this research field (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 6). Cyclic experiments were conducted to evaluate the stability of U6N@ZIS, exhibiting excellent durability with sustained and efficient H2O2 production over 5 cycles of 5 h (Supplementary Fig. 18). No obvious difference was observed in the XRD patterns, FTIR and XPS spectra for U6N@ZIS before and after reaction (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20), suggesting no significant change for its structure and compositions.

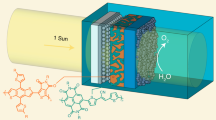

Large-scale H2O2 production in pure water and disinfection application

To enable large-scale H2O2 production, a time-sequential batch reactor was developed using U6N@ZIS-loaded polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membranes. Pure water was pumped into the reactor, and after 1-h reaction, the generated H2O2 solution was extracted. This cycle was repeated continuously, achieving sustained H2O2 production for over 200 h under ambient air exposure (Fig. 3f–h). The generated H2O2 solution was directly applied for on-site disinfection of Escherichia coli (E. coli). Different bathes of E. coli were incubated for 18 h in the presence of either pure water or H2O2 solutions produced at different irradiation durations. The viability of E. coli progressively declined with the added H2O2 concentration increasing (i.e., obtained at increased irradiation time). After 60-min irradiation, the H2O2 concentration peaked, which was then added to the cultures and led to a significant quantity reduction of viable bacteria colonies (Fig. 3e). These results demonstrated the high disinfection efficacy of the H2O2 production system, achieving ~98% inactivation of E. coli (106 CFU/mL, a concentration 1000 times higher than that in natural water), highlighting its strong potential for practical water disinfection.

Z-scheme charge transfer enhanced H2O2 production

The significantly enhanced H2O2 production of U6N@ZIS compared to pristine U6N and ZIS could be attributed to the formed Z-scheme heterojunction, facilitating charge transfer while preserving strong redox capability, aligning with our initial hypothesis.

To unveil the charge transfer mechanism, we first investigated the band structures using ultraviolet–visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV–vis DRS) and Mott-Schottky (M-S) measurements. U6N@ZIS exhibited broad UV-vis absorption (Fig. 4a), with the bandgap energies of U6N and ZIS estimated as 2.18 and 2.78 eV, respectively, based on Tauc plots. The positive slopes of M-S plots showed their n-type semiconductor nature (Supplementary Fig. 21). M-S measurements at three different frequencies (500, 1000, and 1500 Hz) determined the flat band potentials, which in n-type semiconductors typically lie 0.1–0.2 eV below the CB edge. The CB positions of U6N and ZIS were thus identified as −0.59 and −0.71 eV vs RHE, respectively, while their VB edges were estimated at 1.47 and 2.19 eV vs RHE by combining the bandgap energies (Fig. 4b). These results revealed a staggered band alignment, fulfilling the criteria for forming either Type II or Z-scheme heterojunction.

a UV-vis DRS spectra of ZIS, U6N, and U6N@ZIS (Inset: corresponding Tauc plots). b Band alignment of ZIS and U6N. c, d Calculated work functions of U6N and ZIS. e SPV responses (Inset: schematic illustration of the SPV measurement) and f TPV spectra of U6N, ZIS, and U6N@ZIS. fs-TA measurements to show the photoexcited charge dynamics. fs-TA spectra of U6N (g, h) and U6N@ZIS (j, k) with the excitation at the excitation of 320 nm. The corresponding decay kinetics of U6N (i) and U6N@ZIS (l) at 677 nm. Source data for a and e–l are provided as a Source Data file.

To further elucidate the charge transfer pathways, DFT calculations were performed to determine the work functions of U6N and ZIS. U6N exhibited a larger work function (5.07 eV) compared to ZIS (4.22 eV) (Fig. 4c, d), suggesting that charge migration from ZIS to U6N occurs spontaneously upon contact in the dark to reach Fermi level equilibrium. This charge redistribution induced an interfacial electric field directed from ZIS to U6N, consistent with XPS analysis. Under light irradiation, this electric field drives the photoexcited electrons in the CB of U6N toward the VB of ZIS, where they recombine with holes, following the Z-scheme charge transfer pathway. As a result, photogenerated electrons and holes were spatially separated, accumulating in the CB of ZIS and the VB of U6N, respectively, thereby retaining strong redox potential for efficient H2O2 photosynthesis.

To further reveal the charge separation and transfer dynamics in U6N@ZIS, a series of steady-state and transient spectroscopic analyses were conducted. Steady-state surface photovoltage (SPV) analysis was performed to study charge separation behavior. As shown in Fig. 4e, upon light irradiation, photogenerated electrons in ZIS migrated from the bulk to the surface, where they were collected by the amplifier, generating a negative signal. When a U6N layer was introduced beneath the ZIS layer to simulate the composite structure, a more pronounced negative signal was observed compared to pristine ZIS, indicating enhanced electron accumulation on ZIS. This result further confirmed the formation of Z-scheme heterojunctions. Transient surface photovoltage (TPV) measurements were conducted to reveal charge transport dynamics (Fig. 4f). U6N@ZIS exhibited a faster charge extraction rate than ZIS alone (t1 < t2), demonstrating that the heterojunction effectively facilitated charge transfer. Moreover, upon completion of the charge extraction process, the formed heterojunction slowed the charge decay, thereby prolonging the lifetime of photogenerated charge carriers.

To gain deeper insight into the Z-scheme charge transfer dynamics, femtosecond-transient absorption (fs-TA) measurements were conducted using a femtosecond UV pump/white-light continuum probe setup (see Supporting Information for details). This technique allowed us to investigate the electron transfer dynamics between U6N and ZIS (Fig. 4g-l and Supplementary Fig. 22). The pump wavelength was set at 320 nm to effectively excite electrons from the VB to the CB of U6N. Pristine U6N exhibited positive TA signals spanning the 475–750 nm range (Fig. 4g, h). These signals were consistent with photoinduced absorption (PA) of electrons, as previously reported in ultrafast TA studies on U6N53. Given the wavelength-independent TA kinetics within this spectral range, representative data at 677 nm are presented in Fig. 4i. The TA decay profile followed a double-exponential model. The fast decay component (τ1 = 222 ± 117 ps) was attributed to electron trapping by surface defects, while the slower decay (τ2 = 3086 ± 1129 ps) corresponded to charge recombination processes in U6N54.

In contrast, the U6N@ZIS heterojunction exhibited distinct TA spectral and dynamic features. U6N@ZIS displayed both a photoinduced bleach (PB) signal (475–600 nm) and a PA signal centered at 660 nm (Fig. 4j, k). Notably, the PA signal at 660 nm was consistent with that observed in U6N (Fig. 4g, h), allowing us to focus on the spectral evolution in the 600–750 nm range to elucidate the electron transfer process from U6N to ZIS. The TA dynamic at 677 nm for U6N@ZIS (Fig. 4l) revealed a pronounced signal growth with a much longer timescale (τ1 = 9 ± 2 ps) than the instrument response function (~100 fs). Furthermore, within the 50 ps to 7 ns timescale, a positive-to-negative crossover occurred within 2 ns, indicating the effective suppression of electron trapping at U6N CB surface states. If such a trapping process persisted, the characteristic PA signals of U6N would have dominated. Instead, the transition from PA to PB signal suggested efficient electron transfer from the CB of U6N to the VB of ZIS, probed via the PB signals corresponding to ZIS excited states. The observed ~9 ps rise time thus represented the interfacial electron transfer characteristic of a Z-scheme charge transfer pathway55, further confirming the formation of Z-scheme heterojunctions between U6N and ZIS. These findings collectively highlighted the crucial role of the Z-scheme heterojunction in promoting charge separation and prolonged carrier lifetimes, ultimately enhancing photocatalytic H2O2 production.

Mechanistic Insights into H2O2 Formation via ORR

To elucidate the formation pathway of H2O2, photosynthesis experiments were conducted under different atmospheric conditions, including O2, air, and N2 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 23). The H2O2 yield was highest in O2 (3800 μmol g−1 h−1) and slightly decreased in air (3200 μmol g−1 h−1). However, H2O2 production was almost negligible in N2, suggesting that ORR played a pivotal role in H2O2 photosynthesis within the U6N@ZIS system.

a H2O2 yield by U6N@ZIS under different atmosphere to demonstrate the involvement of O2. b Trapping experiments with adding different scavengers for H2O2 photosynthesis by U6N@ZIS. c EPR spectra to detect •OH and •O2− radicals. d, e 18O2 isotope labeling experiments. “Water tank and GC-MS/MS images” from BioRender. Liu, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/wrxgks9. f RRDE polarization curves. g Selectivity of H2O2 and the corresponding average number of transferred electrons. h, i In-situ DRIFTS spectra of U6N@ZIS under different irradiation time after purging the cell with O2. j O2 adsorption configuration on U6N@ZIS. k Calculated free energy diagrams of H2O2 evolution reaction through 2e- ORR pathway by U6N, ZIS, and U6N@ZIS. Source data for a–c and e–i are provided as a Source Data file.

To further probe the reaction intermediates, quenching experiments were performed using AgNO3, isopropanol (IPA), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) as scavengers of electron, hole, and •O2- radicals, respectively (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 24)56,57,58. Upon the addition of AgNO3, H2O2 generation was dramatically suppressed, confirming the essential role of electrons in H2O2 photosynthesis59. In contrast, when IPA was introduced, the H2O2 yield slightly increased, as holes preferentially reacted with IPA rather than recombining with electrons. Moreover, the addition of SOD led to a substantial decline in H2O2 production, indicating that •O2- served as a key intermediate in the H2O2 photosynthesis. The prominent DMPO-•O2- signal was observed in EPR spectra (Fig. 5c), further confirming the generation of •O2- during the photosynthesis of H2O2. Based on these findings, the H2O2 formation pathway should conform to the indirect 2e- ORR process (O2 + e- → •O2-; •O2- + e- + 2H+ → H2O2).

To further verify this mechanism, isotopic labeling experiments were conducted using 18O2 (Fig. 5d). The generated H2O2 was catalyzed by MnO2 to decompose into O2, which was then detected by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). A distinct peak at m/z of 36.01 was observed, corresponding to 18O2 released from H218O2 decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 25). After 12-h light irradiation, 18O2 accounted for 89% of the total detected O2, while the proportion of 16O2 decreased from 100% to 11% (Fig. 5e). These results conclusively demonstrated that H2O2 photosynthesis in the U6N@ZIS system predominantly proceeded via the ORR rather than the WOR. Simultaneously, the photogenerated holes can react with H2O to produce O2 and H+ via the 4e- WOR pathway (2H2O + 4 h+ → O2 + 4H+)24,60,61,62. The dissolved O2 and the produced O2, together with H+, further participate in the ORR process to produce H2O2. To validate the occurrence of the 4e- WOR, we monitored the dissolved O2 concentration in the reaction solution over irradiation time and also analyzed the gaseous products using GC (Supplementary Fig. 26). The observed increase of the dissolved O2 concentration, along with the detected O2 in the produced gas, clearly verified the H2O oxidation to produce O2, which is consistent with previously reported results24,60,61,62.

Optimal O2 adsorption configuration for high 2e- ORR selectivity

ORR generally proceeds via 2e- (O2 + 2H+ + 2e- → H2O2) and/or 4e- pathways (O2 + 4H+ + 4e- → 2H2O). High selectivity toward the 2e- ORR is essential for efficient photocatalytic H2O2 production63, while the O2 adsorption configuration plays a key role in determining the reaction pathway.

The Yeager-type configuration facilitates O-O bond breakage, favoring the 4e- ORR, whereas the Pauling-type preserves the O-O bond, promoting the 2e- ORR. These configurations induce the generation of distinct active intermediates, •O2- for Pauling-type and •O22- for Yeager-type. The •O22- is highly unstable and readily decomposes into •OH and H2O. Thus, the O2 adsorption configuration can be identified by analyzing the active intermediates.

EPR spectra revealed a strong DMPO-•O2- signal for U6N@ZIS, while a negligible DMPO-•OH signal was detected (Fig. 5c). This result indicated that O2 predominantly adsorbed on U6N@ZIS in the Pauling-type configuration, allowing the O-O bond to retain. In contrast, ZIS exhibited a weaker DMPO-•O2- signal but a stronger DMPO-•OH signal compared to U6N@ZIS. Since the VB position of ZIS (1.47 V vs RHE) is more negative than the H2O/•OH potential (2.73 V vs RHE), direct oxidation of H2O to •OH is thermodynamically unfavorable. The detected •OH should thus originate from the decomposition of unstable •O22⁻, which underwent O-O bond cleavage, forming •OH and H2O. When O2 was replaced with Ar, the DMPO-•OH disappeared in the ZIS system, further supporting that Yeager-type adsorption led to O2 conversion into •O22-, which subsequently decomposed into •OH and H2O.

To quantify the 2e- ORR and H2O2 selectivity, rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) measurements were performed to determine the average electron transfer number (n) during the ORR process. (Fig. 5f). The disk current corresponded to the reduction of O2, while the ring current resulted from the oxidation of the produced H2O2. The measured n values for U6N, ZIS, and U6N@ZIS were 2.8, 2.3, and 2.1, respectively, with corresponding H2O2 selectivity of 58.9%, 80.4%, and 94.3% (Fig. 5g). These results confirmed that the 2e- process dominated in the ORR by U6N@ZIS, consistent with the Pauling-type O2 adsorption configuration on U6N@ZIS.

To gain deeper insight into the reaction pathway for H2O2 production, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was employed to track the real-time intermediate formation during H2O2 photosynthesis (Fig. 5h, i). A peak at 903 cm−1 was attributed to the O-O stretching mode of adsorbed O264,65. Peaks between 950 and 1000 cm−1 were ascribed to •O2-, which increased progressively under irradiation66. The appearance of bands between 1389 and 1460 cm−1, assigned to •OOH formed via protonation of •O2-, provided direct evidence of the indirect two-step 2e- ORR pathway67. Moreover, peaks in 1120–1200 cm−1 corresponded to the -OOH bending vibrations of free H2O2 molecules68. These results demonstrated that O2 was primarily adsorbed in the Pauling-type configuration, preventing O–O bond cleavage and favoring the 2e- ORR, thereby achieving high selectivity for H2O2 production.

To elucidate the correlation between catalyst structure and O2 adsorption configuration, theoretical calculations were conducted to investigate O2 adsorption and activation on different catalysts (Fig. 5j and Supplementary Fig. 27). The raw data of the optimized computational models are provided in supplementary data 1. While the porous structure of U6N enabled substantial O2 enrichment, DFT calculations indicated weak O2 binding. U6N@ZIS exhibited a more favorable O2 adsorption energy (−5.918 eV) than U6N (−0.579 eV) and ZIS (−4.909 eV) (Supplementary Fig. 28). Temperature-programmed desorption of O2 (O2-TPD) revealed that U6N@ZIS exhibited significantly stronger O2 adsorption (Supplementary Fig. 29), consistent with calculation results.

With two unpaired electrons in its molecular orbitals, O2 generally adsorbs at two adjacent Zn atoms in ZIS, where electron localization favors a Yeager-type (side-on) configuration. In this case, each Zn atom transfers electrons to p orbital of the O2 to saturate its π* antibonding orbitals, destabilizing the O-O bond to form •O22-. The unstable •O22- intermediate is readily to decompose to •OH and H2O, limiting 2e⁻ ORR and H2O2 production selectivity. The electron transfer from Zn to O was confirmed by the calculated increased number of electrons (Supplementary Table 7) for two O atoms of Yeager-type adsorbed O2 (6.53 and 6.61) compared to the isolated O2 molecule (6.00 and 6.00). Based on the DFT calculations, O2 adsorption on U6N@ZIS followed a Pauling-type configuration, attributed to the S-vacancy induced electron delocalization. It prevents excessive electron transfer to fully fill π* antibonding orbitals, leading to •O2- formation and stabilizing the O-O bond. The protonation of •O2- forms •OOH, enhancing 2e- ORR and H2O2 production. To further validate this conclusion, U6N/ZIS without S-vacancies was prepared via electrostatic assembly (Supplementary Fig. 30). The photocatalytic performance of U6N/ZIS and UiO@ZIS was significantly lower than that of U6N@ZIS (Supplementary Fig. 31), further confirming the crucial role of S-vacancy-induced electronic structure modulation. The distinctly different number of electrons for two O atoms (6.20 and 6.50) verified the partial and unbalanced electron transfer from Zn sites to the Pauling-type adsorbed O2 (Supplementary Table 7).

To further assess the spontaneity of 2e- ORR pathways on different catalysts, Gibbs free energy calculations were conducted (Fig. 5k). Although the free energy favors H2O2 production thermodynamically by U6N, the poor O2 adsorption resulted in low efficiency. On ZIS, the free energy increased upon O2 conversion to •OOH, indicating low 2e- ORR and H2O2 formation selectivity due to the Yeager-type O2 adsorption configuration. By contrast, U6N@ZIS favored Pauling-type adsorption, facilitating •OOH formation and thereby enhancing H2O2 production efficiency. By contrast, U6N@ZIS favored Pauling-type O2 adsorption, promoting •O2- and •OOH formation and thereby enhancing H2O2 production efficiency.

Discussion

In summary, we demonstrate the in-situ growth of ZIS nanosheets with S vacancies onto U6N, forming a Z-scheme heterojunction that enables highly selective photocatalytic H2O2 production. U6N@ZIS achieved a competitive H2O2 generation rate of 3200 μmol g−1 h−1 with high 2e- ORR selectivity of 94.3% in pure water under ambient air and visible light, surpassing most reported photocatalysts under comparable conditions. A time-sequential batch reactor based on U6N@ZIS was further developed, achieving large-scale and long-term H2O2 production over 200 h. The produced H2O2 solution showed effective disinfection of bacteria. The Z-scheme heterojunction largely facilitated charge separation and transfer, as evidenced by TPV, SPV, fs-TA, and DFT calculations, thereby enhancing the photocatalytic performance of U6N@ZIS. EPR and XAS analyses confirmed the presence of S vacancies, which modulated the O2 adsorption to follow the Pauling-type configuration, favoring the 2e- ORR pathway for selective and efficient H2O2 production. A combination of RRDE, isotope labeling, EPR, in-situ DRIFTS, and DFT calculations further elucidated that the indirect 2e- ORR pathway predominated in the U6N@ZIS system for H2O2 photosynthesis. This work provides a viable strategy for optimizing charge dynamics and O2 activation, paving the way for efficient, cost-effective, and scalable photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

N, N-dimethyl formamide (DMF, >99.5%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36.0~38.0%), isopropyl alcohol (IPA, ≥99.7%), silver nitrate (AgNO3, ≥99.8%), zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(AC)2•2H2O, ≥98%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95.0~98.0%), and ethanol (EtOH, >95%) were sourced from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Corporation (Shanghai, China). Zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl4, ≥98%), 2-amino-1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (H2N-H2BDC, ≥98%), indium chloride tetrahydrate (InCl3•4H2O, ≥98%), terephthalicacid (TA, ≥99%), and thioacetamide (TAA, C2H5NS, ≥98%) were acquired from Aladdin Chemical Reagent Corporation (Shanghai, China). Titanic sulfate (Ti(SO4)2, ≥96%) was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology Corporation (Shanghai, China). Superoxide dismutase (SOD, 2500~7000 unit/mg) was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Synthesis of catalysts

Synthesis of ZIS

Typically, 220 mg of Zn(AC)2•2H2O, 586.5 mg of InCl3•4H2O, and 401 mg of TAA were dissolved in 167 mL of deionized water under stirring for 30 min. The mixture was heated in an oil bath at 95 °C for 6 h, then washed five times with deionized water and subsequently freeze-dried.

Synthesis of U6N

U6N was first synthesized by dissolving 1.25 g of ZrCl4 and 1.36 g of H2N-H2BDC in 5 mL of HCl and 100 mL of DMF. The solution was then heated in an oil bath at 120 °C for 6 h. The resulting suspension was washed three times with methanol and acetone, followed by vacuum drying at 60 °C overnight.

Synthesis of U6N@ZIS

U6N@ZIS was prepared using an in-situ growth approach under solvothermal treatment. Typically, Zn(Ac)2•2H2O (55 mg), InCl3•4H2O (147 mg), and thioacetamide (75 mg) were completely dissolved in 167-mL pure water. U6N (141 mg) was then dispersed into the above solution under ultrasonication. The resultant mixture underwent thermal treatment under 95 °C in oil bath for 6 h. The final product was collected using centrifugation and washed with pure water, and then dried at 60 °C in vacuum overnight.

Synthesis of UiO@ZIS

Firstly, 233 mg of ZrCl4 and 166 mg of TA were dissolved in 10 mL of DMF, 3.6 mL of acetic acid was added, and heated at 120 °C for 24 h. After washing with methanol, UiO was obtained. Except for replacing U6N with UiO, the other preparation conditions and procedures were identical to those of U6N@ZIS.

Synthesis of U6N/ZIS

Specifically, 40 mg of U6N and 60 mg of ZIS were dispersed in 100 mL of deionized water under continuous stirring for 24 h to ensure thorough mixing and electrostatic assembly. The resulting suspension was then collected by centrifugation, washed several times with deionized water, and dried at 60 °C to obtain the U6N/ZIS.

Characterizations

XRD analysis was carried out on a SmartLab SE with Cu Kα irradiation (40 kV, 50 mA). The morphology of the materials was characterized by SEM (Zeiss sigma500) and TEM (Thermo Scientific Talos F200X G2) at an acceleration voltage of 20–120 kV. HRTEM (HITACHI HT7820) was used to determine the lattice fringe spacing under the same voltage range. FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet IS50. SPV spectrum was collected on a SPV system, including a Xe light source (CHF-XM500, Perfectlight Technology), a focusing monochromator (Omni-λ3007MC300), a lock-in amplifier (SR830, Stanford Research Systems), and a chopper (SR542, Stanford Research Systems). TPV measurements were performed using an assembled system comprising a nanosecond pulsed laser (Q-smart 450, Quantel), a 500-MHz digital phosphor oscilloscope, and a preamplifier (5003, Brookdeal Electronics). UV-vis DRS was obtained using a Shimadzu UV-3600i Plus spectrophotometer with BaSO4 as the reflectance standard. EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker A300 spectrometer. O2-TPD was conducted on Micromeritics AutoChem II 2910.

Photocatalytic performance for H2O2 production

Photocatalytic H2O2 production

Typically, 1 mg of photocatalyst was dispersed in 10 mL of pure water. The solution was stirred for 30 min in the dark to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium between ambient air and water. Unless otherwise specified, all reactions in this work were conducted under ambient air conditions. A 300 W Xe arc lamp (PLS/XSE 300D/300DUV, Perfectlight) equipped with a cutoff filter (λ ≥ 400 nm) served as the top irradiation. The reaction system was maintained at 20 ± 0.5 °C via circulating cooling water. At regular intervals of 15 min, 2-mL aliquots were collected and filtered through a 0.22-µm filter membrane for analysis.

Analysis of H2O2

The produced H2O2 concentration was determined using a ultraviolet (UV)-visible spectrophotometer (UT-1810PC) via a titanium sulfate colorimetry method. Specifically, 4.5 g of Ti(SO4)2 was dissolved in 250 mL of 0.40 M H2SO4 to prepare the titanium oxide sulfate (TiOSO4) solution (denoted as Solution A). A 2 mL aliquot of the reaction solution was mixed with 2 mL of Solution A and left to stand for 5 min. Under acidic conditions, H2O2 reacts with TiOSO4 to form a yellow titanium peroxide complex (H2TiO2(SO4)2). This complex exhibits a characteristic absorption peak near 410 nm, which was thus used for the determination of generated H2O2 concentration.

Formation and decomposition of H2O2

By assuming the zero-order kinetic model, H2O2 formation rate (kf, mM h−1) was estimated by fitting the data in Fig. 3a. The rate constants of H2O2 decomposition (kd, h−1) were calculated by assuming a first-order kinetic model using the Eq. (1):

Determination of AQY

The AQY measurement was performed in pure water using a 100-W LED lamp (PerfectLight) with monochromatic wavelengths of 365, 420, 500, 560, and 660 nm. Specifically, 50 mg of as-prepared photocatalysts were dispersed in 100 mL of pure water. The solution underwent 20-min irradiation, the concentration of H2O2 was then measured to calculate the AQY using the Eq. (2):

where Ne is the number of electrons transferred in the reaction, Np is the number of incident photons, n represents the amount of produced H2O2 molecules (mol), and NA is the Avogadro’s constant (6.02 × 1023). I is the incident light intensity (100 mW cm−2), S is the irradiation area (1 cm2), t is the irradiation time (1200 s), h is the Planck’s constant (6.62 × 10−34 J S), c is the speed of light (3 × 108 m s-1), and λ is the wavelength of the monochromatic light (m).

Continuous-flow reactor for H2O2 production

Continuous flow reactor consists of two peristaltic pumps and a reaction cell. Firstly, 50 mg of U6N@ZIS were dissolved in 4 mL of ethanol, followed by the addition of 200 μL of Nafion solution. After sonicating for 30 min, a homogeneous solution was obtained, which was then evenly drop-coated on the hydrophilic side of the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) film. After it was dried, the PTFE loaded with U6N@ZIS was fixed at the bottom of the reaction cell. The pure water intake and hydrodynamic residence time were controlled at 10 mL and 1 h, respectively. The reaction solution was automatically collected at an interval of 1 h, containing considerable concentration of H2O2 for further bacteria killing use.

Quenching experiments

Trapping experiments of reactive species were performed under the same conditions with photocatalytic H2O2 production. IPA (1 mM), AgNO3 (0.5 mM), and SOD (200 Unit/mL) were added to capture photogenerated h+, e-, and •O2- radicals, respectively.

Disinfection performance

E. coli was cultured in LB both to the logarithmic phase, reaching ~109 colony forming unit per milliliter (CFU·mL−1). The generated H2O2 was collected from the post-reaction slurry via filtration and used for bacterial inactivation experiments. The initial E. coli suspension was diluted to 107 CFU mL−1, and 1 mL of the bacterial solution was mixed with 9 mL of the generated H2O2 solution. After incubation at 37 °C for 3 h, 100 µL of the diluted samples were immediately spread onto nutrient agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to assess bacterial viability.

Isotope labeling experiments

A total of 40 mg of U6N@ZIS was dispersed into 80 mL of H216O. To remove residue 16O2 from the vessel and solution, N2 was pumped into the quartz glass reactor, followed by vacuum evacuation. This process was repeated three times to ensure complete removal of 16O2. 18O2 was bubbled into the solution until absorption–desorption equilibrium was reached. The mixture solution was then exposed to a 300-W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 400 nm) for 12 h. After the reaction, 20 mL of solution was collected and transferred into a brown vial containing a certain amount of MnO2. To prevent air contamination, the vial was pre-purged with N2 and securely sealed to avoid air leakage. After decomposition, the resulting gas products were analyzed using gas chromatograph-mass spectrometry (Thermo Scientific TSQ9000).

XAFS measurements

XAFS spectra were acquired at the BL11B beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) utilizing a high-resolution Si (111) double-crystal monochromator. The storage ring of SSRF operates stably at an energy level of 3.5 GeV with a maximum injection current of 250 mA. All XAFS spectra were collected under ambient conditions to ensure the accuracy of the chemical and structural characterization.

In-situ DRIFTS measurements

The photocatalytic reaction was conducted using a Bruker INVENIO-S FTIR spectrometer equipped with a Harrick diffuse reflectance accessory. A 10 mg sample was uniformly distributed in the sample holder and pressed to ensure a flat and consistent surface. Prior to the reaction, the sample was purged with Ar (50 mL/min) at 20 °C for 20 minutes to remove adsorbed gases, and a background spectrum was recorded in the dark. Subsequently, O2 (50 mL/min) was introduced into the reaction chamber by bubbling through water until the adsorption equilibrium was reached. A 300-W Xe lamp was then switched on to initiate the photocatalytic reaction, and FTIR spectra were collected in situ over 0–60 minutes at 10-minute intervals.

fs-TA measurements

fs-TA measurements were conducted using a regenerative amplified Ti:sapphire laser system (Coherent; 800 nm, 100 fs, 7 mJ/pulse, and 1 kHz repetition rate) as the laser source and a HELIOS spectrometer (Ultrafast Systems LLC) for detection. The white-light continuum (WLC) probe pulse (475-750 nm) was generated by focusing a small portion of the 800-nm beam (split from regenerative amplifier with a tiny portion) onto a sapphire crystal. A motorized optical delay line varied the time delay between the pump and probe pulses from 0 to 8 ns. A mechanical chopper operating at 500 Hz was used to modulate the pump pulses, enabling alternating recording of fs-TA spectra with and without excitation. The samples were dispersed in dimethyl sulfoxide and placed in a 2-mm quartz cuvette under continuous magnetic stirring to ensure a fresh photoexcited volume throughout the measurements.

Electrochemical measurement of ORR

The electron transfer number (n) and H2O2 selectivity of the catalysts during the ORR were evaluated using an electrochemical workstation (CHI760E) in a three-electrode cell. A rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) served as the working electrode, with a graphite rod as the counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl as the reference. The electrolyte was O2-saturated Na2SO4 solution (0.1 M). Measurements were performed under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm). The RRDE rotation speed was set to 1600 rpm, and scan rate was maintained at 10 mV s−1. The selectivity of H2O2 (H2O2%) and the n value were calculated using the Eqs. (3) and (4):

where Id and Ir represent the disk and ring currents, respectively, and N is the experimentally determined collection coefficient.

Computational methods

Density functional calculation is performed. All the calculations are within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation. We have chosen the projected augmented wave (PAW) potentials to describe the ionic cores and take valence electrons into account using a plane wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 450 eV. Partial occupancies of the Kohn−Sham orbitals were allowed using the Gaussian smearing method and a width of 0.01 eV. The electronic energy was considered self-consistent when the energy change was smaller than 10−5 eV. The equilibrium lattice constants of the unit cell were optimized, when using a 2 × 2 × 2 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid for Brillouin zone sampling During structural optimizations of the surface models, a 2 × 2 × 2 gamma-point is used. The (001) facet of ZIS was selected for DFT calculations. The adsorption energy for O2 on the substrate was calculated based on Ead=Etot-Esub\(\mbox-{{\rm{E}}}_{{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}\), where Ead is the adsorption energy, Etot is the total energy of the system, Esub is the energy of the substrate, and \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}\) is the energy of the O2 molecule.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Du, J. et al. CoIn dual-atom catalyst for hydrogen peroxide production via oxygen reduction reaction in acid. Nat. Commun. 14, 4766 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. H2O2 generation from O2 and H2O on a near-infrared absorbing porphyrin supramolecular photocatalyst. Nat. Energy 8, 361–371 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Mechanistic analysis of multiple processes controlling solar-driven H2O2 synthesis using engineered polymeric carbon nitride. Nat. Commun. 12, 3701 (2021).

Freese, T., Meijer, J. T., Feringa, B. L. & Beil, S. B. An organic perspective on photocatalytic production of hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Catal. 6, 553–558 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. Linkage-engineered donor–acceptor covalent organic frameworks for optimal photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and air. Nat. Catal. 7, 195–206 (2024).

Ling, H. et al. Sustainable photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production over octonary high-entropy oxide. Nat. Commun. 15, 9505 (2024).

Fan, W. et al. Efficient hydrogen peroxide synthesis by metal-free polyterthiophene via photoelectrocatalytic dioxygen reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 238–245 (2020).

Ding, Y. et al. Emerging semiconductors and metal-organic-compounds-related photocatalysts for sustainable hydrogen peroxide production. Matter 5, 2119–2167 (2022).

Zeng, X., Liu, Y., Hu, X. & Zhang, X. Photoredox catalysis over semiconductors for light-driven hydrogen peroxide production. Green Chem. 23, 1466–1494 (2021).

Tang, Y. et al. The evolution of photocatalytic H2O2 generation: from pure water to natural systems and beyond. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 6482–6498 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Developing Ni single-atom sites in carbon nitride for efficient photocatalytic H2O2 production. Nat. Commun. 14, 7115 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Linear conjugated polymers for solar-driven hydrogen peroxide production: the importance of catalyst stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 19287–19293 (2021).

Sun, Y., Han, L. & Strasser, P. A comparative perspective of electrochemical and photochemical approaches for catalytic H2O2 production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 6605–6631 (2020).

Peng, H. et al. Defective ZnIn2S4 nanosheets for visible-light and sacrificial-agent-free H2O2 photosynthesis via O2/H2O Redox. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27757–27766 (2023).

Kuttassery, F. et al. A Molecular Z-scheme artificial photosynthetic system under the bias-free condition for CO₂ reduction coupled with water oxidation: photocatalytic production of CO/HCOOH and H₂O₂. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202308956 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Surface energy mediated sulfur vacancy of ZnIn2S4 atomic layers for photocatalytic H2O2 production. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302964 (2023).

Qiu, J. et al. Ligand functionalization on Zr-MOFs enables efficient visible-light-driven H2O2 evolution in pure water. Catal. Sci. Technol. 13, 2101–2107 (2023).

Andreou, E. K., Vamvasakis, I., Douloumis, A., Kopidakis, G. & Armatas, G. S. Size dependent photocatalytic activity of mesoporous ZnIn2S4 nanocrystal networks. ACS Catal. 14, 14251–14262 (2024).

Li, Y., Guo, Y., Luan, D., Gu, X. & Lou, X.-W. An unlocked two-dimensional conductive Zn-MOF on polymeric carbon nitride for photocatalytic H2O2 production. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202310847 (2023).

Choi, J. Y. et al. Photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production through functionalized semiconductive metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11319–11327 (2024).

Kondo, Y., Kuwahara, Y., Mori, K. & Yamashita, H. Design of metal-organic framework catalysts for photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. Chem. 8, 2924–2938 (2022).

Lu, X. et al. Boosted charge transfer for highly efficient photosynthesis of H2O2 over Z-Scheme I−/K+ Co-Doped g-C3N4/metal-organic-frameworks in pure water under visible light. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2401873 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Engineering 2D photocatalysts for solar hydrogen peroxide production. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400740 (2024).

Teng, Z. et al. Atomically dispersed antimony on carbon nitride for the artificial photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Catal. 4, 374–384 (2021).

Chu, C. et al. Electronic tuning of metal nanoparticles for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. ACS Catal. 9, 626–631 (2018).

Choi, C. H. et al. Hydrogen peroxide synthesis via enhanced two-electron oxygen reduction pathway on carbon-coated Pt surface. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 30063–30070 (2014).

Xie, L. et al. Pauling-type adsorption of O2 induced electrocatalytic singlet oxygen production on N-CuO for organic pollutants degradation. Nat. Commun. 13, 5560 (2022).

Kulkarni, A., Siahrostami, S., Patel, A. & Nørskov, J. K. Understanding catalytic activity trends in the oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Rev. 118, 2302–2312 (2018).

Watanabe, E., Ushiyama, H. & Yamashita, K. Theoretical studies on the mechanism of oxygen reduction reaction on clean and O-substituted Ta3N5(100) surfaces. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 2769–2776 (2015).

Xie, Y. et al. Direct oxygen-oxygen cleavage through optimizing interatomic distances in dual single-atom electrocatalysts for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 135, e202301833 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Pauling-type adsorption of O2 induced by heteroatom doped ZnIn2S4 for boosted solar-driven H2O2 production. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 136, e202317816 (2023).

Jung, E. et al. Atomic-level tuning of Co–N–C catalyst for high-performance electrochemical H2O2 production. Nat. Mater. 19, 436–442 (2020).

Gao, R. et al. Engineering facets and oxygen vacancies over hematite single crystal for intensified electrocatalytic H2O2 production. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910539 (2020).

Zhou, X. et al. Synergistic conversion of hydrogen peroxide and benzaldehyde in air by silver single-atom modified Thiophene-functionalized g-C3N4. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 64, e202505532 (2025).

Li, C. et al. Ladder-like built-in electric field enhances self-assembly, carrier separation and ultra-efficient photocatalytic oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 37, e2502918 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Dipole field in nitrogen-enriched carbon nitride with external forces to boost the artificial photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Commun. 14, 5742 (2023).

Zhou, S. et al. Pauling-type adsorption of O2 induced by S-scheme electric field for boosted photocatalytic H2O2 production. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 199, 53–65 (2024).

Cai, W., Tanaka, Y., Zhu, X. & Ohno, T. A single atom photocatalyst co-doped with potassium and gallium for enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide synthesis. Nano Res. 17, 7027–7038 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Halogen atom-induced local asymmetric electron in covalent organic frameworks boosts photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and air. Matter 8, 102076 (2025).

Yu, H. et al. Vinyl-group-anchored covalent organic framework for promoting the photocatalytic generation of hydrogen peroxide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 63, e202402297 (2024).

Zhou, J. L. et al. Unlocking one-step two-electron oxygen reduction via metalloid boron-modified Zn3In2S6 for efficient H2O2 photosynthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 64, e202506963 (2025).

Xi, Y. et al. Modulating active hydrogen supply and O2 adsorption: sulfur vacancy matters for boosting H2O2 photosynthesis performance. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 64, e202505046 (2025).

Peng, X. et al. Nanohybrid photocatalysts with ZnIn2S4 nanosheets encapsulated UiO-66 octahedral nanoparticles for visible-light-driven hydrogen generation. Appl. Catal. B 260, 118152 (2020).

Qin, J. et al. Photocatalytic valorization of plastic waste over zinc oxide encapsulated in a metal–organic framework. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214839 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Controlled partial linker thermolysis in metal-organic framework UiO-66-NH2 to give a single-site copper photocatalyst for the functionalization of terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202308651 (2023).

Dong, Y.-L., Liu, H.-R., Wang, S.-M., Guan, G.-W. & Yang, Q.-Y. Immobilizing Isatin-Schiff base complexes in NH2-UiO-66 for highly photocatalytic CO2 reduction. ACS Catal. 13, 2547–2554 (2023).

Qiu, J. et al. COF/In2S3 S-scheme photocatalyst with enhanced light absorption and H2O2-production activity and fs-TA Investigation. Adv. Mater. 36, e2400288 (2024).

Guo, C. et al. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to Ethanol at close to theoretical potential via engineering abundant electron-donating Cuδ+ species. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 61, e202205909 (2022).

Lu, B. et al. Iridium-incorporated strontium tungsten oxynitride perovskite for efficient acidic hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13547–13555 (2022).

Zhou, D. et al. Ni, In co-doped ZnIn2S4 for efficient hydrogen evolution: Modulating charge flow and balancing H adsorption/desorption. Appl. Catal. B 310, 121337 (2022).

Peng, C. et al. Double sulfur vacancies by lithium tuning enhance CO2 electroreduction to n-propanol. Nat. Commun. 12, 1580 (2021).

Rehr, J. J., Kas, J. J., Vila, F. D., Prange, M. P. & Jorissen, K. Parameter-free calculations of X-ray spectra with FEFF9. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 5503–5513 (2010).

Xiao, J. D. et al. Boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production of a metal–organic framework decorated with platinum nanoparticles: the platinum location matters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 9389–9393 (2016).

Wheeler, D. A. & Zhang, J. Z. Exciton dynamics in semiconductor nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 25, 2878–2896 (2013).

Li, R. et al. Integration of an Inorganic Semiconductor with a Metal–Organic Framework: A Platform for Enhanced Gaseous Photocatalytic Reactions. Adv. Mater. 26, 4783–4788 (2014).

Yang, C., Wan, S., Zhu, B., Yu, J. & Cao, S. Calcination-regulated microstructures of donor-acceptor polymers towards enhanced and stable photocatalytic H2O2 production in pure water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 61, e202208438 (2022).

Chu, C. et al. Large-scale continuous and in situ photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide by sulfur-functionalized polymer catalyst for water treatment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 63, e202317214 (2024).

Xu, M., Wang, R., Fu, H., Shi, Y. & Ling, L. Harmonizing the cyano-group and Na to enhance selective photocatalytic O2 activation on carbon nitride for refractory pollutant degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 121, e2318787121 (2024).

Cheng, J., Wan, S. & Cao, S. Promoting solar-driven hydrogen peroxide production over Thiazole-based conjugated polymers via generating and converting singlet oxygen. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202310476 (2023).

Liu, P. et al. Photocatalytic H2O2 production over boron-doped g-C3N4 containing coordinatively unsaturated FeOOH sites and CoOx clusters. Nat. Commun. 15, 9224 (2024).

Liao, Q. et al. Regulating relative nitrogen locations of diazine functionalized covalent organic frameworks for overall H2O2 photosynthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202310556 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Graphene quantum dot-modified Mn0.2Cd0.8S for efficient overall photosynthesis of H2O2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2422307 (2025).

Xia, C., Kim, J. Y. & Wang, H. Recommended practice to report selectivity in electrochemical synthesis of H2O2. Nat. Catal. 3, 605–607 (2020).

Ma, X. et al. S-Scheme heterojunction fabricated from covalent organic framework and quantum dot for enhanced photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and air. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2409913 (2024).

Wen, N. et al. Dynamic bromine vacancy-mediated photocatalytic three-step three-electron oxygen reduction to hydroxyl radicals. ACS Catal. 14, 11153–11163 (2024).

Nakamura, R., Imanishi, A., Murakoshi, K. & Nakato, Y. In Situ FTIR studies of primary intermediates of photocatalytic reactions on nanocrystalline TiO2 films in contact with aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7443–7450 (2003).

Zhao, Y. et al. Small-molecule catalyzed H2O2 production via a phase-transfer photocatalytic process. Appl. Catal. B 314, 121499 (2022).

Ruan, X. et al. Iso-Elemental ZnIn2S4/Zn3In2S6 heterojunction with low contact energy barrier boosts artificial photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2401744 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22206113 and 22376124 to Q.Z., No. 22572222 to Z.H.), the Taishan Scholars Project Special Fund (No. tsqn202211039 to Q.Z.), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2022HWYQ-015 to Q.Z., ZR2023JQ007 to R.L.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFC3712500 to Z.H.), and Natural Science Foundation Program of Henan Province (No. 252300421437 to Z.C.). Theoretical calculations were supported by the National Supercomputer Center in Guangzhou and the National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen (Shenzhen Cloud Computing Center). We also appreciate the FTIR analysis by Dr. Min Zhang and N2 adsorption measurements by Dr. Xiaowen Su from the Analytical Testing Center, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Shandong University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. conceived and designed the study. Z.G. performed the experiments. Z.H. operated DFT calculations. Z.C. conducted ultrafast measurements. Z.G., F.L., Q.Z., X.L., Z.H., Q.S., P.J.C., X.Z., J.Z., and Z.Z. analyzed the data. Q.Z., R.L., Y.Y., and Y.C. supervised the experiments. Q.Z. and Z.G. wrote the paper. All the authors discussed and revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Z., Liu, F., Chen, Z. et al. Defect-modulated oxygen adsorption and Z-scheme charge transfer for highly selective H2O2 photosynthesis in pure water. Nat Commun 16, 8889 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64166-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64166-8