Abstract

Floating-gate memories (FGMs) show great promise for neuromorphic computing in efficient data-centric applications. However, their limited single-device state capacity remains insufficient for highly integrated precision computing. Here, we demonstrate 11-bit two-dimensional (2D) MoS2 FGMs by contacting the 2D channels with bismuth electrodes, enabling 100 μA on-state current with 108 on/off ratio and reducing the current noise by 3 times (approaching the equipment limits) due to the Schottky barrier-free interfaces. Moreover, we employed a dual-pulse state editing scheme enhancing the stability of our FGMs. The devices show as high as 2,249 distinct conductance levels (>11-bit) while maintaining 230 ns operation speed, >104 s retention, and >105 cycle endurance. Furthermore, the gate-injection operation prevents the influence from generated defects during cycling, maintaining low noise even after 105 cycles and at 85 °C. Theoretical analysis reveals interfacial defects as the primary state-number limitation, suggesting 17-bit capacity is achievable through further trap density reduction. This work establishes 2D FGMs as promising candidates for high-bit-density, low-power neuromorphic hardware.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid growth of data-centric applications driven by artificial intelligence (AI) has posed severe energy consumption challenges1. This is largely due to the traditional inefficient computing system characterized by separated memory-processing units, sequential operations, and complex Boolean logic that needs more than one device to achieve basic logic functions. Neuromorphic computing offers a promising solution to this bottleneck by mimicking the brain’s energy-efficient mechanisms2,3,4,5,6. This paradigm enables efficient analog data processing with minimal energy consumption, showing great potential for AI, intelligent edge computing, and the Internet of Things7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. A critical requirement for neuromorphic hardware is precise analog signal modulation, which relies on achieving distinguishable multi-bit memory states16,17,18. Traditional approaches expand bit capacity through device integration but inevitably increase system complexity and power consumption. In contrast, single-device multilevel storage strategies offer distinct advantages through minimized device footprint and enhanced system integration, accelerating neuromorphic computing development19,20,21,22.

Recent advances in multi-bit memory technologies include resistive random-access memories (RRAMs), which leverage electroresistive switching to achieve high bit capacities. For instance, 11 bits for Ta/Al2O3/HfO2/Pt memristor23 and 14 bits for molecular memristor based on a Ru-complex of an azo-aromatic ligand24 have been demonstrated. Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement in uniformity and compatibility12,25,26. Floating-gate memories (FGMs), on the other hand, provide precise conductivity control by storing charges in a floating gate27. Combined with the simple structure and CMOS compatibility, FGMs are a promising choice for neuromorphic computing hardware. This is especially true when two-dimensional (2D) materials are introduced as the channel, whose atomic-scale thickness enhances gate controllability and integration capability28,29,30. For example, MoS2 FGMs have been implemented in vector–matrix multiplication processors31, exhibit robust non-volatile memory performance even at ultra-scaled 10 nm channel lengths32, and show ultrafast sub-nanosecond programming speed33.

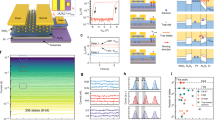

Achieving multi-bit storage in FGMs demands three key criteria (Fig. 1a): 1) a large on/off ratio (dynamic range), which is a prerequisite for multi-bit storage, 2) a high stability to prevent conductance merging during long-term retention, and 3) low noise (conductance fluctuations) to enable more conductance levels within a limited dynamic range. Previously, we demonstrated 8-bit storage in gate-injection MoS2 FGMs using a dual-pulse state editing scheme34. However, this is still not high enough for precise scientific computing. And further improvements in dynamic range and noise reduction are needed to achieve higher bit capacities.

a Three factors for increasing the storage state number for FGMs (Floating-gate memories): expanding the dynamic range, which means increasing the ratio of on-state current (Ion) to off-state current (Ioff); enhancing the stability of conductance states; lowering device noise, which refers to conductance state fluctuations (σn or σn’). b An optical microscopy image and schematic diagram of the MoS2 FGM, where Bi/Au is used as the contact electrodes, Cr/Au as the control gate, Pt as the floating gate, and Al2O3 as the dielectric layer. The programming and erasing operations occur at the control gate region. c, d Output and transfer curves of FGMs with Bi/Au (green lines) and Cr/Au (blue lines) contacts. JDS is the source-drain current density, while VDS and VGS are the source-drain voltage and gate voltage, respectively. e, f The programming and erasing processes using dual-pulse (yellow lines) and single-pulse (green lines) programming methods. Insets show the dual pulse programming scheme. A tune voltage pulse (Vtune) with an opposite sign follows the programming/erasing voltage pulse (Vprogram/Verase) to achieve stable states. g, h The IDS-time curves and noise current spectrum (SI)-IDS curves of FGMs with Bi/Au (brown lines) and Cr/Au (yellow lines) contacts.

Here, we present 11-bit MoS2 FGMs through three key optimizations: enhanced on-state currents (100 µA) and on/off ratio (108) through Bi contacts, Schottky barrier-free contacts reducing current noise by 3 times to approach the equipment limits, and a dual-pulse state editing method improving storage stability. Our devices achieve as high as 2249 distinct conductance levels (>11-bit), surpassing most charge-trap memories and rivaling top-performing RRAMs. They also show a fast operation of 230 ns, long retention of exceeding 104 s, high endurance of over 105 cycles, and good device-to-device reproducibility. Furthermore, the gate-injection mode prevents the influence of defects generated inside dielectric layers during cycling, maintaining low noise even after 105 cycles and at 85 °C. Theoretical analysis demonstrates that interfacial defects are the primary limiting factor for state numbers, suggesting that 17-bit storage capacity is attainable through further trap density reduction. This work highlights the potential of 2D FGMs for next-generation neuromorphic computing hardware.

Results

Main strategies to realize 11-bit 2D FGMs

Gate-injection FGMs based on MoS2 channels were fabricated with the optical microscope image of a typical device and device structure shown in Fig. 1b. Specifically, Bi/Au source/drain contacts and Cr/Au control gate were employed to ensure a low contact resistance and a high endurance. An 8 nm Al2O3 layer functions as both the tunneling layer and blocking layer, while a 5 nm Pt layer acts as the floating gate (FG). It is worth noting that, unlike traditional FGMs, the CG and S/D electrodes are not arranged perpendicularly but rather in a coplanar configuration. This design enables charge injection/erasure to occur at the CG rather than the channel region when negative/positive gate voltage pulses are applied, corresponding to a gate-injection mode to non-volatilely program the conductance of the device.

The detailed energy band structure of the FGMs is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1, where the high energy barrier of ~3.15 eV between Pt and Al2O3 provides a deep potential well for stable charge trapping. During programming, electrons are injected from the CG into the FG under negative gate voltage pulses. However, some electrons are trapped by defect states within the Al2O3 layer, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. These trapped electrons experience lower energy barriers and can detrap easily, leading to a gradual conductance decay over time35. To mitigate this effect, a dual-pulse programming strategy was introduced, consisting of edit voltage pulses (Vprogram/Verase) followed by a tune voltage pulse (Vtune) with opposite polarity. This approach promotes detrapping of electrons from these defect states in the Al2O3 layer, thereby stabilizing the memory states (Supplementary Fig. 2)34.

Based on this, we can address the three primary limitations on the number of memory states. First, Bi contacts were used to eliminate the Schottky barrier (SB), significantly enhancing the on-state current of MoS2 transistors36. This improvement improves the on/off ratio and facilitates multi-bit storage. The output curves of the fabricated Bi/MoS2 devices exhibit a linear source drain current density-source drain voltage (JDS-VDS) relationship, with JDS two orders of magnitude higher than that of a Cr/MoS2 device (4.15 µA/µm versus 5.74 nA/µm at VDS of 1 V, Fig. 1c). In addition, transfer curves in Fig. 1d demonstrate that the Bi/MoS2 device exhibits an on/off ratio of 108, which is two orders of magnitude higher than the Cr/MoS2 device. Note that the counterclockwise hysteresis confirms the gate-injection mechanism.

Second, the dual-pulse voltage editing strategy described in Supplementary Fig. 2 was adopted to stabilize conductance states. For the programming process shown in Fig. 1e, applying a positive Vtune following a negative Vprogram significantly enhances the conductance stability, with negligible decay observed over 1,000 s. In contrast, single-pulse programming exhibits rapid decay. Similarly, for the erasure process shown in Fig. 1f, the dual-pulse approach (applying a negative Vtune after a positive Verase) also improves the conductance stability compared to single-pulse operation.

Third, Bi contacts effectively reduce current noise by eliminating SB-related noise contribution. For long-channel transistors, noise primarily originates from thermal noise, shot noise, and low-frequency noise (LFN) that comprises both channel and SB components37,38,39. SB noise constitutes a substantial portion of the total noise for SB FETs, with its current noise spectrum (SISB) given by40:

Here, q represents the elementary charge, Nt is the charge density trapped at the SB interface, CSB is the Schottky capacitance per unit area, S is the contact area, and η is the proportion of the SB resistance in the total resistance, that is, η = RSB/(RC + RSB), where RSB is the contact resistance and RC is the channel resistance. kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, VDS is the bias voltage, and f is the frequency. To analyze the influence of different contact resistances on SB noise, Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 present a detailed comparison of the contact resistances measured by the TLM (transfer-length method) for MoS2 contacted with Cr/Au and Bi/Au. For Cr/Au, the contact resistance 2RSB-Cr ranges from approximately 49.8 – 101.8 kΩ·µm across different MoS2 thicknesses, decreasing as the MoS2 becomes thicker. In contrast, the Bi/Au contact resistance 2RSB-Bi falls 1.3 – 3.6 kΩ·µm for various MoS2 thicknesses, significantly lower than that of Cr/Au. Consequently, the Cr/Au contact resistance accounts for more than 50% of the total resistance, making SB noise non-negligible and causing substantial conductance fluctuations. However, for Bi/Au electrodes, the contact resistance constitutes only about 2% of the total resistance (Supplementary Fig. 5), so SB noise can be safely ignored. As shown in Fig. 1h, the Cr/MoS2 device shows markedly higher noise than the Bi/MoS2 device at an identical programmed current level. For robust comparison, we fabricated 10 devices of each type and statistically analyzed the total noises (SI) across current levels from 1 pA to 100 nA (Supplementary Fig. 6). Both device types show comparable noise in the low-current regime (IDS < 1 nA, the subthreshold regime), as the noise is dominated by the large channel resistance. While in the linear regime (IDS > 1 nA), SB noise becomes predominant, making the noise of Cr/MoS2 devices approximately three times higher than Bi/MoS2 devices (Fig. 1i). This underscores the critical role of SB elimination in noise minimization.

Experimental demonstration of 11-bit 2D FGMs

Through the above designs, we achieved more than 11-bit stable conductance states in 2D FGMs. Specifically, a Vprogram of –8 V with a duration of 20 µs was initially applied to set the device into an off-state with an IDS of 1 pA. Then, Verase ranging from 4 V to 8 V with a step of 0.02 V (20 µs duration), followed by a 20 µs Vtune of –3.5 V with a 50 µs interval, was used to incrementally program the device current from 1 pA to 100 µA. Ultimately, 2249 distinct current states spanning the entire range with discernibly separated adjacent levels are achieved (Fig. 2a, b).

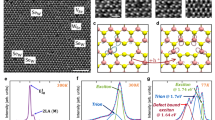

a The output curves of a 2,249-level MoS2 FGM. b The IDS-time curves of the device. VDS = 1 V. c The IDS-time curves of three selected regions (red dashed boxes in Fig. 2b). σ320, σ321, and σ322 denote the noises of level 320, 321, and 322, respectively. d, e Rapid programming and erase processes by the dual-pulse editing method. The waveforms of the dual-pulse are shown as the insets. The widths of the two pulses are fixed at 90 ns, with an interval of 50 ns. The amplitude of pulse1 is increasing, while the amplitude of pulse2 (|Vtune | ) is fixed at 3.5 V. The read voltage is 1 V. f long-term retention performance of several selected storage levels over a period of 104 s. g The endurance performance of the device by the dual-pulse editing method, where the amplitudes of the dual pulses are gradually increased after every 25,000 cycles, and the on-off ratio of the device also increases accordingly. The widths of the dual pulses are fixed at 50 µs, with an interval of 50 µs. The corresponding dual-pulse amplitudes for erasing and programming within the four sets of 25,000 cycles are as follows: 4.6 V, –2 V, and –5.6 V, 3 V; 4.8 V, –2 V, and –5.8 V, 3 V; 5 V, –2 V, and –6 V, 3 V; 6 V, –2 V, and –7 V, 3 V.

Figure 2c highlights three specific current regions: ~3.90 pA in region I, ~4.33 nA in region II, and ~4.68 µA in region III, where no cross-talk between neighboring levels is observed. Taking region II as an example, we observe that the currents fluctuate around their mean values (µ), conforming to a Gaussian distribution with standard deviations (σ). According to the 3σ criterion, the difference between the mean values of two adjacent levels exceeds three times of the sum of their standard deviations, i.e., µ321 – µ320 > 3(σ321 + σ320), where the numbers refer to state indices, confirming the levels are distinguishable. Even after a prolonged retention time of 1000 s, adjacent levels remain clearly distinguishable, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7.

The devices also show nanosecond-scale operation speeds. The dual-pulse method, employing 90 ns Vprogram/erase/Vtune with a 50 ns interval, was used to assess the switching speed. Figure 2d shows the programming dynamics starting from an initialized current of ~40 µA under a Vtune of +3.5 V. The current decreases to ~15 µA after a –6 V Vprogram (pulse 1), and ~1 pA after a –9 V Vprogram. For the erasure process shown in Fig. 2e, the starting current is ~1 pA and Vtune is –3.5 V. A 5 V Verase increases the current to ~10 pA, whereas an 8 V Verase drives it to ~40 µA. The total 230 ns duration highlights the fast operation and low-power programming capability of the 2D FGMs. Figure 2f illustrates the long-term retention performance, where seven randomly selected levels between 1 pA and 100 µA show good stability over a period of 104 s. The devices also show good cycling endurance (Fig. 2g), with pulse amplitude gradually increasing after every 25,000 cycles. Reliable conductance switching persists even after 105 cycles. The devices still exhibit endurance up to 105 cycles after six months, further attesting to devices’ robust stability and reliability (Supplementary Fig. 8). Robust endurance provides the prerequisite for arbitrary-state programming. In this work, we implemented an automated editing method based on a PID (proportional-integral-derivative) algorithm, illustrated schematically in Supplementary Fig. 9. With the amplitude and width of the Vtune held fixed, the algorithm repeatedly reads the current and updates the amplitude of Vprogram iteratively, steering the device toward any target current state. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, after only a few Vprogram updates, the measured current gradually converges to the target values.

Repeatability of 11-bit 2D FGMs

We fabricated a dozen devices to study the replicability of the 11-bit FGMs. Optical images and MoS2 thicknesses are presented in Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12. Channels from monolayer to few-layer MoS2 were used, revealing a weak dependence between layer number and bit count—a consequence of the combined effects of suppressed SB noise and an improved on/off ratio achieved with Bi/Au contacts. The negligible SB noise between MoS2 films of varying thicknesses and Bi/Au contacts, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, also demonstrates this point. Figure 3a summarizes the minimum off-state current (Ioff) and maximum on-state current (Ion). Ioff remains around 1 pA, following a Gaussian distribution centered at ~1.1 pA with a narrow σ of 0.1 pA (left panel of Fig. 3b). While Ion exhibits a broader Gaussian profile centered at ~74.9 µA (right panel of Fig. 3b), which is probably because of the variations in MoS2 thicknesses and device dimensions. The IDS-time profiles, showcasing multi-level storage, are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 13.

a The maximum on-state currents and minimum off-state currents for 12 devices. b Distribution statistical histogram of the maximum on-state currents and minimum off-state currents for 12 devices. The curve represents the fitted Gaussian distribution. c Statistical distribution of current decay values for 12 devices, measured at each order of magnitude starting from 1 pA. Current decay is defined as the difference between the average current over the first five seconds (IDS mean1) and the latter five seconds (IDS mean2). d Histogram of the maximum state numbers of 12 devices. e Current normalized noise as a function of IDS for 10 11-bit devices, and the noise (red curve) of a typical device after undergoing 105 program/erase (±5 V, 50 μs) cycles.

To quantify the state stability, we calculated the current differences between the mean values during the initial five seconds (IDS mean1) and the latter five seconds (IDS mean2) as shown in the top panel of Fig. 3c. The extracted state decays (bottom panel of Fig. 3c) are 3–5 orders smaller than the corresponding state currents, with only 70 pA decay even for 10 µA states. Furthermore, all 12 devices show uniform state decay distributions across the whole current range, underscoring the high stability and repeatability. Ten devices attained 11-bit storage, while two achieved 10-bit capacity (Fig. 3d). We noted that the latter exhibited comparable Ion, Ioff, and stability, but with higher noise. This disparity arises mainly from unavoidable structure defects and interface states introduced during the fabrication steps-such as dielectric layer growth and material transfer, which lead to device-to-device performance variations41,42. But these issues can be mitigated by optimizing the process flow: replacing mechanically exfoliated MoS2 with CVD-grown material34, inserting N2 annealing between consecutive steps32, and employing Se-assisted transfer techniques43. Such improvements yield clean, high-quality interfaces, thereby lowering interface-state density and device noise. This indicates that noise is a critical factor for high-bit operation, and fabrication uniformity is very important for devices based on low-dimensional materials.

The current normalized noise (SI/IDS) across the whole current range is shown in Fig. 3e. The noises decrease with increasing IDS and stays at minimal levels approaching the instrument measurement limit. Such low noise results from optimizations in contact architecture and dry transfer method. Moreover, noise remains unchanged after 105 cycles (red curve in Fig. 3e). And Supplementary Fig. 14 confirms 11-bit retention (2,174 distinct levels) even after prolonged operational stress. This good noise endurance originates from the gate-injection mode design, where charge injection/erasure occurs at the CG/Al2O3 interface, away from the channel, mitigating the influence from the induced dielectric defects during cycling. We further conducted a detailed analysis of device-to-device uniformity for each discrete current level during multi-level storage. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15a, the average currents of every level within the same current range are compared across the ten 11-bit devices presented in Supplementary Fig. 13. Supplementary Fig. 15b plots the corresponding statistic coefficient of variation (Cv = σ/μ, σ is the standard deviation and μ is the average current.) for these level-averaged currents. Remarkably, Cv remains below 5% across the entire current range, demonstrating high uniformity. This uniformity is preserved even after 105 program/erase cycles, with no observable degradation.

Noise analysis and benchmark of 11-bit 2D FGMs

For Bi/MoS2 devices, noise mainly consists of thermal noise, shot noise, and channel-related LFN. Among them, thermal noise (SIth) is frequency (f)-independent and given by44:

where B is the bandwidth, and R is the resistance. Shot noise (SIsh), originating from discrete charge flow, is also frequency-independent and given by:

LFN is relatively complicated and usually considered to stem from the trapping/detrapping of interfacial charges. According to the carrier number fluctuation (CNF) model, it is formed by the fluctuation of charge carrier number due to the defect states, and its expression is45,46:

where gm is the transconductance (Supplementary Fig. 16a), μeff is the effective mobility (~30 cm2/Vs), α is the Coulomb scattering coefficient (~104 Vs/C for electrons)47,48, Cox is the gate dielectric capacitance per unit area (~0.01 F/m2 for 8 nm Al2O3), SVfb is the flat-band voltage power spectral density49:

where Nst is the areal surface trap density, W and L are the width and length of the channel. Hence, Nst has a significant impact on LFN. Fitting the experimental data yields an Nst of 4 × 1014 cm−2 eV−1 (Supplementary Fig. 16b), consistent with previous reports41,50, verifying the dominant role of the CNF model. The frequency-dependent SVfb depicted in Supplementary Fig. 16c provides further insight into the noise dynamics.

Figure 4a plots the total noise current spectrum. Generally speaking, SI increases with IDS and scales as 1/f. LFN dominates at low frequencies, while thermal/shot noise prevails at high frequencies (f-independent white noise). Figure 4b compares these components at 10 Hz. It is evident that LFN significantly outweighs both thermal and shot noises at this frequency regime. When the temperature is increased to 85 °C, theoretical calculations using Eqs. 2–5 predict an increase in both thermal noise and LFN (Supplementary Fig. 17a and b), whereas shot noise remains unchanged. Experimentally, the overall noise shows only a slight increase compared to room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 17c), in agreement with theoretical predictions. Despite this, the device maintains an 11-bit storage capacity under 85 °C conditions (Supplementary Fig. 17d), demonstrating its reliable performance at elevated temperatures.

a Mapping diagram of calculated noise current as a function of frequency and IDS. b Plot of low-frequency noise (LFN), thermal noise, and shot noise versus IDS at a channel area (The product of channel width and length, WL) of 60 μm2 and a frequency of 10 Hz. The yellow shaded area represents the measurement accuracy limit of the instrument. B is the bandwidth and Nst is the areal surface trap density. c The maximum state number versus IDS for 10 11-bit devices, as well as the calculated theoretical maximum state number of the devices under the Nst values of 4 × 1012 cm–2 eV–1 and 4 × 1010 cm–2 eV–1. d Benchmark for multi-bit storage in various existing nonvolatile memories: FeM (ferroelectric memory)55,56,57,58,59, PCM (phase change memory)60,61,62,63, MRAM (magnetic random access memory)64,65, RRAM (resistive random access memory)23,24,66, silicon eFLASH67,68,69,70, and 2D FGMs34. The detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 4c shows the maximum state numbers of the 10 devices as a function of IDS. As IDS gradually increases from 1 pA, the state number grows, reaching 11 bits at ~100 μA. Further improvements require higher on-state current and lower noise. On the one hand, there is still room for further noise optimization. For instance, the surface trap density of ~4 × 1014 cm–2 eV–1 is amenable to improvement. Strategies include surface passivation, new types of dielectrics, and van der Waals dielectric integration41,51,52,53,54. This will, in turn, mitigate the devices’ low-frequency noise and achieve a higher state number. The gray dashed lines represent the calculated maximum state numbers by reducing the surface trap density according to the CNF model. 14-bit and 17-bit levels can be realized at 100 μA, when the surface trap density is reduced to 4 × 1012 cm–2 eV–1 and 4 × 1010 cm–2 eV–1, respectively.

On the other hand, the on-off ratio can be further enhanced. Since 1 pA has already reached the instrument limit, this can be achieved by increasing Ion. Feasible approaches include using better contact metals like Sb and shortening the channel length. However, reducing the device area can lead to an increase in SVfb, thereby increasing noise. For the CNF model with Nst = 4 × 1010 cm–2 eV–1, the maximum state number at 100 μA reduces to 14 bits and 13 bits, when the device area is reduced to 1 μm2 and 0.1 μm2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18). Of course, shorter channels also mean increased Ion. Thus, a balance between noise and dynamic range is critical.

Finally, we benchmark our devices with the existing nonvolatile memories (Fig. 4d), including silicon eFLASH, phase change memory (PCM), ferroelectric memory (FeM), magnetic random-access memory (MRAM), and resistive random-access memory (RRAM). It reveals our 11-bit performance leads among charge-trap memories and rivals top-tier RRAM reported very recently. Combined with CMOS compatibility, this underscores 2D FGMs’ potential for neuromorphic computing.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated high-performance two-dimensional floating-gate memories achieving 11-bit precision through device architecture design and programming strategies. The gate-injection design combined with the dual-pulse state editing scheme enables stable state programming. The Schottky-barrier-free bismuth contacts increase the on-state current and on-off ratio by 3 orders to 100 μA and 108, and reduce the noise by 3 times, approaching the equipment limits. Through these optimizations, we have realized as high as 2249 distinct conductance states with excellent state distinguishability. The devices exhibit fast operation of ~230 ns, stable retention exceeding 104 s, high endurance over 105 cycles, 2148 storage levels and good repeatability. In addition, the gate-injection design isolates the influence of induced dielectric defects from the channel, enabling low noise after 105 cycles and at 85 °C. Comprehensive noise analysis reveals that the achieved performance is primarily limited by dielectric trap density, suggesting pathways toward even higher capacities of 17 bits through interface engineering. Comparison shows that 11-bit performance leads among charge-trap memories and compares with top-tier RRAMs. This work establishes 2D floating-gate memories as a promising platform for next-generation neuromorphic computing, combining high precision, speed, and reliability with standard fabrication compatibility.

Methods

Device fabrication

To fabricate the FGMs, patterned Pt FGs (5 nm) were first deposited on SiO2/Si substrates using electron beam evaporation. Subsequently, 8 nm Al2O3 dielectric layers were grown on top of the Pt FGs via atomic layer deposition (ALD). Next, MoS2 flakes were exfoliated from high-purity (99.995%) bulk crystals (purchased from Shanghai Onway Technology Co., Ltd.) onto the Al2O3 surface. Finally, Bi/Au (20 nm/50 nm) source/drain electrodes and Cr/Au (8 nm/50 nm) control gate electrodes were patterned using standard electron beam lithography (EBL), followed by thermal evaporation. To fabricate the TLM devices, MoS2 flakes with various thicknesses were exfoliated on SiO2/Si substrates. Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) photoresist was employed as the etch mask. After defining the etch pattern by EBL, a CF4/O2 plasma (8:20 sccm, 20 W RF power) was used for dry etching. The etch time varied from 1 s to 6 s, depending on film thickness, yielding well-defined rectangular stripes. The sample was then annealed at 200 °C for 2 h in a nitrogen atmosphere. Finally, electrode patterns were exposed by a second EBL step, followed by metal evaporation to form the contacts.

Characterizations

The identification and inspection of the devices were carried out using optical microscopy (OM) with an Olympus BX51M microscope. The thicknesses of the MoS2 flakes were measured using atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Icon) and a Raman microscope. The electrical properties of the devices were characterized with a Keysight B1500A semiconductor analyzer, interfaced with a Lakeshore TTP4 probe station. All electrical measurements were performed in a high vacuum environment (approximately 10–6 Torr) to minimize the impact of atmospheric factors and ensure the reliability of the data.

Data availability

The Source Data underlying the figures of this study are available with the paper. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, S. Data centres will use twice as much energy by 2030—driven by AI. Nature, (2025).

Mead, C. How we created neuromorphic engineering. Nat. Electron. 3, 434–435 (2020).

Ham, D., Park, H., Hwang, S. & Kim, K. Neuromorphic electronics based on copying and pasting the brain. Nat. Electron. 4, 635–644 (2021).

Mead, C. Neuromorphic electronic systems. Proc. IEEE 78, 1629–1636 (1990).

Yang, J.-Q. et al. Neuromorphic Engineering: From Biological to Spike-Based Hardware Nervous Systems. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003610 (2020).

Schuman, C. D. et al. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 10–19 (2022).

Lin, P. et al. Three-dimensional memristor circuits as complex neural networks. Nat. Electron. 3, 225–232 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. A Three-Dimensional Neuromorphic Photosensor Array for Nonvolatile In-Sensor Computing. Nano Lett. 23, 4524–4532 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Exploring ferroelectric switching in α-In2Se3 for neuromorphic computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004609 (2020).

Mikolajick, T., Park, M. H., Begon-Lours, L. & Slesazeck, S. From ferroelectric material optimization to neuromorphic devices. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206042 (2023).

Zhang, H.-T. et al. Reconfigurable perovskite nickelate electronics for artificial intelligence. Science 375, 533–539 (2022).

Kim, S. J. et al. Linearly programmable two-dimensional halide perovskite memristor arrays for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 83–92 (2024).

Tong, L. et al. 2D materials-based homogeneous transistor-memory architecture for neuromorphic hardware. Science 373, 1353–1358 (2021).

Merolla, P. A. et al. A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 345, 668–673 (2014).

Kiani, F., Yin, J., Wang, Z., Yang, J. J. & Xia, Q. A fully hardware-based memristive multilayer neural network. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj4801 (2021).

Lee, S. T., Kwon, D., Kim, H., Yoo, H. & Lee, J. H. NAND flash based novel synaptic architecture for highly robust and high-density quantized neural networks with binary neuron activation of (1, 0). IEEE Access 8, 114330–114339 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. A memristive deep belief neural network based on silicon synapses. Nat. Electron. 5, 870–880 (2022).

Obradovic, B. et al. A multi-bit neuromorphic weight cell using ferroelectric FETs, suitable for SoC integration. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 6, 438–448 (2018).

Muir, D. R. & Sheik, S. The road to commercial success for neuromorphic technologies. Nat. Commun. 16, 3586 (2025).

Wang, C. et al. Multi-state memristors and their applications: an overview. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 12, 723–734 (2022).

Sangwan, V. K. & Hersam, M. C. Neuromorphic nanoelectronic materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 517–528 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Internal ion transport in ionic 2D CuInP2S6 enabling multi-state neuromorphic computing with low operation current. Mater. Today 66, 9–16 (2023).

Rao, M. et al. Thousands of conductance levels in memristors integrated on CMOS. Nature 615, 823–829 (2023).

Sharma, D. et al. Linear symmetric self-selecting 14-bit kinetic molecular memristors. Nature 633, 560–566 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. High-Uniformity Threshold Switching HfO2-Based Selectors with Patterned Ag Nanodots. Adv. Sci., 202002251 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Conduction mechanisms, dynamics and stability in ReRAMs. Microelectron. Eng. 187, 121–133 (2018).

Migliato Marega, G. et al. Logic-in-memory based on an atomically thin semiconductor. Nature 587, 72–77 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Ultrafast non-volatile flash memory based on van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 874–881 (2021).

Wu, L. et al. Atomically sharp interface enabled ultrahigh-speed non-volatile memory devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 882–887 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. An ultrafast bipolar flash memory for self-activated in-memory computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 486–492 (2023).

Migliato Marega, G. et al. A large-scale integrated vector–matrix multiplication processor based on monolayer molybdenum disulfide memories. Nat. Electron. 6, 991–998 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. A scalable integration process for ultrafast two-dimensional flash memory. Nat. Electron. 7, 868–875 (2024).

Xiang, Y. et al. Subnanosecond flash memory enabled by 2D-enhanced hot-carrier injection. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08839-w (2025).

Cai, Y. et al. 8-bit states in 2D floating-gate memories using gate-injection mode for large-scale convolutional neural networks. Nat. Commun. 16, 2649 (2025).

Zafar, S., Kumar, A., Gusev, E. & Cartier, E. Threshold voltage instabilities in high-/spl kappa/ gate dielectric stacks. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 5, 45–64 (2005).

Shen, P.-C. et al. Ultralow contact resistance between semimetal and monolayer semiconductors. Nature 593, 211–217 (2021).

Xie, X. et al. Low-Frequency Noise in Bilayer MoS2 Transistor. ACS Nano 8, 5633–5640 (2014).

Na, J. et al. Low-frequency noise in multilayer MoS2 field-effect transistors: the effect of high-k passivation. Nanoscale 6, 433–441 (2014).

Sharma, D. et al. Electrical transport and low-frequency noise in chemical vapor deposited single-layer MoS2 devices. Nanotechnology 25, 155702 (2014).

Clement, N., Larrieu, G. & Dubois, E. Low-frequency noise in schottky-barrier-based nanoscale field-effect transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 59, 180–187 (2012).

Yan, Y. et al. CMOS-compatible fabrication of 2D semiconductor-based CFETs via high-k dielectric van der waals encapsulation. Nano Lett. 25, 6125–6133 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. A clean transfer approach to prepare centimetre-scale black phosphorus crystalline multilayers on silicon substrates for field-effect transistors. Nat. Commun. 15, 6795 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Se-mediated dry transfer of wafer-scale 2D semiconductors for advanced electronics. Nat. Commun. 16, 4468 (2025).

Sarpeshkar, R., Delbruck, T. & Mead, C. A. White noise in MOS transistors and resistors. IEEE Circuits Devices Mag. 9, 23–29 (1993).

Hung, K. K., Ko, P. K., Hu, C. & Cheng, Y. C. A unified model for the flicker noise in metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 37, 654–665 (1990).

Ghibaudo, G., Roux, O., Nguyen-Duc, C., Balestra, F. & Brini, J. Improved Analysis of Low Frequency Noise in Field-Effect MOS Transistors. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 124, 571–581 (1991).

Emrani, A., Balestra, F. & Ghibaudo, G. On the understanding of electron and hole mobility models from room to liquid helium temperatures. Solid-State Electron. 37, 1723–1730 (1994).

Bennamane, K. et al. Mobility coupling effects due to remote Coulomb scattering in thin-film FD-SOI CMOS devices. Electron. Lett. 49, 490–492 (2013).

Surya, C. & Hsiang, T. Y. A thermal activation model for 1/ƒy noise in Si-MOSFETs. Solid-State Electron. 31, 959–964 (1988).

Zhu, W. et al. Electronic transport and device prospects of monolayer molybdenum disulphide grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Commun. 5, 3087 (2014).

Zhang, F. et al. Dielectric Integrations and Advanced Interface Engineering for 2D Field-Effect Transistors. Small Methods, 2402187, 10.1002/smtd.202402187 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Uniform and ultrathin high-κ gate dielectrics for two-dimensional electronic devices. Nat. Electron. 2, 563–571 (2019).

Zhou, W., Zhang, S. & Zeng, H. Perovskite oxides as a 2D dielectric. Nat. Electron. 5, 199–200 (2022).

Lu, Z. et al. Wafer-scale high-κ dielectrics for two-dimensional circuits via van der Waals integration. Nat. Commun. 14, 2340 (2023).

Jerry, M. et al. Ferroelectric FET analog synapse for acceleration of deep neural network training, in 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). (2017), pp. 6.2.1–6.2.4.

Wang, X. et al. Van der Waals engineering of ferroelectric heterostructures for long-retention memory. Nat. Commun. 12, 1109 (2021).

Zeng, B. et al. Electric Field Gradient-Controlled Domain Switching for Size Effect-Resistant Multilevel Operations in HfO2-Based Ferroelectric Field-Effect Transistor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2011077 (2021).

Ali, T. et al. A Multilevel FeFET Memory Device based on Laminated HSO and HZO Ferroelectric Layers for High-Density Storage, in 2019 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). (2019), pp. 28.27.21–28.27.24.

Lee, D. et al. Multilevel Data Storage Memory Using Deterministic Polarization Control. Adv. Mater. 24, 402–406 (2012).

Yin, Y. & Hosaka, S. Nanosecond-Order Fast Switching and Ultra-Multilevel Storage in Lateral GeTe and Ge1Sb4Te7-Based Phase-Change Memories, in 2015 IEEE 11th International Conference on ASIC (ASICON). (2015), pp. 1–4.

Yin, Y. & Hosaka, S. Multilevel storage in lateral phase-change memory by promotion of nanocrystallization. Microelectron. Eng. 88, 2794–2796 (2011).

Ventrice, D. et al. A Phase Change Memory Compact Model for Multilevel Applications. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 28, 973–975 (2007).

Kumari, S., Durai, S. & Manivannan, A. Impact of process-induced variability on multi-bit phase change memory devices. Microelectron. J. 130, 105638 (2022).

Fukami, S., Zhang, C., DuttaGupta, S., Kurenkov, A. & Ohno, H. Magnetization switching by spin–orbit torque in an antiferromagnet–ferromagnet bilayer system. Nat. Mater. 15, 535–541 (2016).

Shen, J. et al. A multilevel nonvolatile magnetoelectric memory. Sci. Rep. 6, 34473 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Memristors with analogue switching and high on/off ratios using a van der Waals metallic cathode. Nat. Electron. 8, 36–45 (2024).

Judy, M. et al. A Digitally Interfaced Analog Correlation Filter System for Object Tracking Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Sys. I: Reg. Pap. 65, 2764–2773 (2018).

Gao, S. et al. Programmable Linear RAM: A new flash memory-based memristor for artificial synapses and its application to speech recognition system, in 2019 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). (2019), pp. 14.11.11–14.11.14.

Khakifirooz, A. et al. A 1.67Tb, 5b/Cell Flash Memory Fabricated in 192-Layer Floating Gate 3D-nand Technology and Featuring a 23.3 Gb/mm2 Bit Density. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 6, 161–164 (2023).

Park, S., Palaskas, Y. & Flynn, M. P. A 4-GS/s 4-bit Flash ADC in 0.18-μm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 42, 1865–1872 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Henan Academy of Sciences Startup Research Project (No. 241840192, 241840189, 241840187, 241840190), the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1201500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U24A2055, U24A20302, 62374048, 62274046, 12204122, 62204217, 22301162), Henan Natural Science Foundation (No. 252300420970), and Basic scientific research Fund of Henan Academy of Sciences (Nos. 20250640002, 20250640001) The authors also gratefully acknowledge the support of Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS and CAS Key Laboratory of Nanosystem and Hierarchical Fabrication. The authors thank the Nanofabrication Laboratory at National Center for Nanoscience and Technology for sample fabrication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., Y.C., and F.W. conceived the idea and analyzed the data. Y.W. fabricated the devices and carried out measurements. Y.W. and F.W. co-wrote the manuscript. T.Y., S.L., M.C., R.H., B.Z., K.X., X.Z. assisted in revising the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results. J.H. and Z.W. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Young-Jun Yu, Kaichen Zhu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Cai, Y., Wang, F. et al. 11-bit two-dimensional floating-gate memories. Nat Commun 16, 9268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64333-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64333-x