Abstract

Phosphorus is a critically limiting nutrient in marine ecosystems, with alkaline phosphatases (APases) playing a vital role in liberating phosphate from organic compounds. However, the dominant taxa and APase families driving the marine phosphorus cycle, particularly in the deep ocean, remain poorly understood. Equally enigmatic remains the (multi)functional diversity and mechanisms of action of different APases. To address these gaps, this study combines global multi-omic analyses, biochemical studies of purified recombinant proteins, and laboratory experiments with proteomics and enzymatic rate measurements. Here we show that multi-omics consistently identify Alteromonas as a primary contributor to APase expression and production, with PhoA as the dominant APase family, particularly in the deep ocean. Furthermore, all four major APase families (PhoA, PhoD, PhoX, PafA) exhibit multifunctionality, revealing distinct substrate preferences and regulatory mechanisms. Ultimately, this study expands the mechanistic understanding of the marine phosphorus cycle, while revealing the significance of enzyme multifunctionality in elemental cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The element phosphorus (P) is an important macronutrient essential for all known life forms. However, the lack of a gaseous state of P makes the source of biologically available phosphate in the ocean dependent on sporadic inputs (e.g., river discharge, atmospheric deposition), which can limit biomass production. Phosphorus exists in various forms within the marine environment, where microbes convert dissolved inorganic phosphorus (Pi) as phosphate (PO43-) into organic P and vice versa. This biological transformation of these various molecular forms constitutes the core of the marine P cycle. Phosphorus is also an essential component of cellular structures, metabolism, and regulatory processes, forming vital molecules such as phospholipids, ATP, and DNA. Upon cell death, grazing, or viral infection, these P-containing compounds are released into the water as dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP). In many marine ecosystems, such as surface waters and tropical- and subtropical gyres, which are typically Pi-depleted, DOP becomes the primary source of P for microbial growth1,2. Studies employing 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy have indicated that the vast majority (75-85%) of DOP comprises phosphate esters3,4. The hydrolysis of compounds such as Pi-esters is primarily catalyzed by both cell surface-bound ectoenzymes and dissolved cell-free exoenzymes, predominantly alkaline phosphatases (APases)5. Consequently, APases play a central role in recycling DOP within marine environments and thereby driving the P cycle6.

It is recognized that promiscuity is a widespread characteristic of enzymes; that is, they possess secondary activities that are not part of the organism’s physiology7. When these activities become physiologically relevant, the terms should change to ‘multifunctional’, ‘multispecific’, ‘polyfunctional’ or ‘broad specificity’8. Despite often being overlooked, genuinely multifunctional enzymes are crucial for organismal survival and adaptation in diverse environments. Nevertheless, the prevalence of the one-protein one-reaction paradigm has led to the absence of their multiple reactions in bioinformatic models implying a shortfall for biogeochemical research. For example, a study with Rhodobacteraceae found that, out of the 25,000 metabolic products, less than 1% (<100 compounds) matched genome-predicted metabolites9. Therefore, including promiscuous activities and multifunctionality in enzymatic databases is imperative for a more comprehensive understanding of biogeochemical cycles, particularly for key enzymes in biogeochemical cycles such as APase in the P cycle.

In a recent study we uncovered the multifunctionality of marine PhoA (from Alteromonas mediterranea), raising important questions about the ecological implications of enzymes with broad substrate specificity and their role in environmental processes10. But PhoA is only one out of the four main APase protein families (PhoA, PhoD, PhoX, and PafA) thus far described. These families are distinguished primarily as P-monoesterases or P-diesterases, varying in substrate affinity and requiring different cofactors11,12,13,14,15. For instance, PhoA possesses two zinc ions and one magnesium ion at its active site, whereas PhoD and PhoX require calcium and iron ions12,14,16,17. However, whether multifunctionality is a common characteristic across all APase families, or a particular condition of PhoA, remains unknown. Furthermore, while previous purely biochemical studies have explored the essential roles of APases and their enzyme promiscuity in the laboratory, we are still lacking information on the ecological aspects of their enzymatic multifunctionality including gene expression, metaproteomic profiling, and taxonomic affiliation of the different APase families in natural environments7,18,19,20,21,22.

To address these gaps, this study combines biochemical analysis of purified recombinant proteins, laboratory incubations of isolated culture representatives coupled with proteomics and enzymatic rate measurements, with global marine metatranscriptomic and metaproteomic data23,24. Our results identify Alteromonas as the dominant taxon responsible for APase expression and production, and thus a key player in the marine P cycle, as well as uncover the widespread multifunctionality and distinct expression patterns and regulatory mechanisms of the major APase families (PhoA, PhoD, PhoX, and PafA) in the ocean. For instance, we found that PhoD is the primary APase and is significantly upregulated under P-limitation. This, coupled with its broad substrate versatility, suggests an efficient strategy for P-scavenging. Ultimately, this study expands the mechanistic understanding of the marine P cycle, while revealing the significance of enzyme multifunctionality in elemental cycles.

Results and discussion

Alteromonas dominates global production of marine APase

We first performed a metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of all global marine APases using the Tara Oceans dataset by focusing on three different depths: surface, deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM), and mesopelagic waters (200–1000 m). We expanded our analysis beyond surface waters to include the deep ocean (mesopelagic zone), motivated by two key factors: (1) documented evidence of high alkaline phosphatase activity25,26,27 and (2) the demonstrated capacity of mesopelagic prokaryotic communities to mediate carbon processing at rates comparable to epipelagic systems28. A single genus, Alteromonas, dominated the expression of most APases (phoA, phoD and phoX), particularly in the mesopelagic layer (Fig. 1A). The ratio of metatranscriptomic to metagenomic APase abundances highlighted the dominant role of Alteromonas in all APase genes expression, exhibiting significantly higher values than all other taxa across all depths, while its dominance was most pronounced for phoA (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 1). Among all APase genes, phoA was the most highly expressed APase across all depth layers (Fig. 1B), while phoD, phoX and pafA exhibited lower expression. Furthermore, all families, except for pafA, exhibited an increased expression with depth (Fig. 1B). Notably, Alteromonas dominated the expression across all APase families, except for pafA, where Flavobacteriales predominated across all depths (Fig. 1A), in agreement with previous findings indicating Bacteroidota as the main taxa expressing PafA phosphatases29. Consistently, a further examination of the occurrence of APase gene homologs in a large and diverse collection of marine genomes, also revealed Alteromonas as one of the top genera with the highest number of APase gene homologs per genome, particularly the phoA gene which exceeded an average of one copy per genome (Supplementary Fig. 2). The presence of multiple, diverse APase homologs in Alteromonas suggests a sophisticated adaptation for P acquisition. This strategy is also observed in other marine gammaproteobacteria that harbor a diverse repertoire of APase genes, indicating it might be a broader adaptive strategy30. Consistent with these observations, a recent multi-omic study on marine snow degradation also identified Alteromonas as a central player, highlighting its widespread enzymatic capabilities in processing organic matter in the ocean31.

The samples were grouped by depth: surface (SRF; n = 103), deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM; n = 49) and mesopelagic (MES; n = 26). A The figure shows the normalized transcript abundances of alkaline phosphatase families across major taxonomic groups in the Tara Oceans dataset. ‘other’ refers to taxa that were not classified within the highlighted groups. B Total normalized transcript abundance50 from each alkaline phosphatase family across all samples and depth layers. Letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences determined by pairwise two-sided Mann-Whitney U tests (p < 0.05). Groups that do not share a letter are significantly different from one another. In the box plots, the center line represents the median, box limits indicate the interquartile range (IQR), whiskers extend to 1.5× the IQR, and points beyond the whiskers are individual data points.

A further metaproteomic analysis, grouped by size fractions (i.e., free-living 0.2–0.8 μm, particle-attached >0.8 μm, and exoenzymes <0.2 µm), provided further additional evidence of the dominance of Alteromonas in APase enzyme production from the surface down to bathypelagic depths (Fig. 2). It should be noted that this analysis used depths (epipelagic, mesopelagic, bathypelagic) based on the referenced metaproteomic study by Zhao et al., which differed from the Tara Oceans depth layers due to distinct original sampling strategies23. For certain APase families, such as PhoA, Alteromonas contributed up to 95% of enzyme abundance, particularly in the exoenzyme and free-living fraction, but also exhibited lower relative contributions in some particle-attached fractions, depending on depth and enzyme family (Fig. 2). This variation may indicate greater specialization of other taxa in particle-associated P-cycling or suggest that secreted Alteromonas APases predominantly contribute to the dissolved enzyme pool. Similar to the metatranscriptomic data, APase production in the metaproteome was highest in the mesopelagic layer (Fig. 2). Consistently, previous studies using substrate analogs have reported elevated cell-specific APase activity in the deep ocean. This is surprising since APase activity is traditionally associated with P-limitation, yet deep waters typically have high phosphate concentrations25,27,32. This ‘APase paradox’ has led to several theories suggesting that deep-sea APase activities may be related to accessing the carbon backbone of dissolved organic phosphorus or are associated with the accumulation of extracellular enzymes characterized by extended lifetimes32. Our analysis supports the latter explanation by not only revealing high expression of APases in deep-water layers, but also uncovering a high abundance of APase proteins, particularly in the exoenzymatic (i.e., dissolved) fraction (Figs. 1 and 2). The dominance of these dissolved exocellular APases from Alteromonas, particularly PhoA and PhoX, indicates their importance in non-cellular P cycling. To directly assess enzyme persistence, we conducted lifetime assays on purified APases under controlled conditions at 24 °C for 60 days (Supplementary Fig. 3). PafA displayed the longest half-life at 23.3 ± 8.2 days, while PhoA persisted for 5.6 ± 0.8 days. In contrast, PhoD and PhoX were shorter-lived, with half-lives of 0.7 ± 0.1 days and 1.2 ± 0.05 days, respectively. This relevant role of dissolved APases aligns with the recently proposed explanation for the ‘APase paradox’ which attributes the high proportion of cell-free APases activities in the ocean to a potential decoupling from direct cellular expression, suggesting their extensive role in biogeochemical cycles28,33,34. These enzymes can therefore create a persistent pool of cell-free enzymes that contribute to deep-ocean nutrient regeneration, which in turn influences surface productivity through physical processes like upwelling and mixing. Collectively, our findings identify Alteromonas as a key contributor to marine APase expression and production, with phoA being the most highly expressed and produced APase across all depths. Moreover, we found a relevant contribution from both cell-associated and exoenzymatic APases of Alteromonas, underscoring their essential role in the ‘APase paradox’ in particular, and the ocean’s P cycle in general.

The violin plots depict the relative abundance of alkaline phosphatase families (PhoA, PhoD, PhoX, and PafA) in free-living (0.2–0.8 μm), particle-attached (>0.8 μm), and exoenzymes (<0.2 µm) fractions across epipelagic, mesopelagic, and bathypelagic layers. The y-axis is the predicted percent contribution of the enzymes to the total proteome in each sample. Blue represents the cumulative abundance of all taxa, while red highlights the contribution of Alteromonas, with labels indicating the percentage of all taxa (± standard deviation).

Enzymatic multifunctionality is widespread in all APase families of Alteromonas

To understand enzyme physiology, kinetic parameters such as turnover rate (kcat) and catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) provide essential insights into an enzyme’s substrate processing speed and efficiency, respectively. High kcat values indicate fast substrate turnover, while high kcat/KM values reflect an enzyme’s ability to efficiently catalyze reactions at low substrate concentrations—key factors influencing enzyme functionality in various ecological contexts. To test and quantify the multifunctionality of the major APase families, four APase gene sequences from Alteromonas mediterranea DE were used for de novo biosynthesis, enabling detailed analysis of their diverse catalytic activities using p-nitrophenyl based substrates (Table 1) as well as an expanded set of substrate experiments including glucose-6-phosphate (Glu-P), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), pyrophosphate (pyro-P), tripolyphosphate (tripoly-P), and methylphosphonate (P-nate) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Remarkably, all of the APases we tested exhibited secondary (multifunctional) enzymatic activities alongside their primary enzymatic preferences, with negligible activity with P-nate (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 4). PhoA exhibited a clear preference towards monoesterase activity (kcat = 2.7 × 10⁻² s-1), and approximately 100-fold lower diesterase activity (kcat = 3.9 × 10⁻4 s-1, Table 1). The monoesterase activity of PhoA was the highest among all enzymes tested, indicating its efficiency at higher substrate concentrations, also shown by a relatively high KM value (Table 1). PhoA also exhibited relatively high activity with Glu-P and ATP, but low activity towards pyro-P and tripoly-P (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Conversely, PhoD exhibited turnover rates of comparable magnitude for both mono- and diesterase activities (kcat = 7.8 × 10⁻³ s-1 and kcat = 9.9 × 10⁻³ s−1, respectively). However, a closer examination of the Michaelis-Menten constants revealed a 7-fold higher overall catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for the phosphodiesterase activity, due to a lower KM (kcat/KM = 0.16 L mmol−1 s−1 and 1.1 L mmol−1 s−1 for mono- and diesterase respectively, Table 1). Furthermore, PhoD showed relatively high activity with ATP, and moderate activity with pyro-P and tripoly-P, while activity with Glu-P was lower (Supplementary Fig. 4). Indeed, PhoD was most active as a phosphodiesterase, consistent with previous research showing phosphodiesterase activity for the Bacillus subtilis PhoD towards cell wall teichoic acids and phospholipids35. PhoD also exhibited the highest measured triesterase activity among all enzymes (kcat = 2.9 × 10−4 s−1, Table 1). Thus, our results suggest that PhoD is a multifunctional mono-, di- and tri-esterase and therefore could play a multifaceted role in marine phosphorus cycling.

PhoX exhibited its principal enzymatic activity with the monoester substrate. Despite being previously characterized as a monoesterase lacking any diesterase activity14, our findings indicate that the A. mediterranea enzyme also exhibits low diesterase activity (kcat = 8.6 × 10−4 s−1 and 2.5 × 10−5 s−1 for mono- and diesterase respectively, Table 1). PhoX has substantially lower mono- and di-esterase activities than PhoA and PhoD, suggesting that these activities may be of limited physiological relevance to A. mediterranea. On the other hand, PhoX was one of only two enzymes (along with PafA) with detectable sulfatase Michaelis-Menten values. This raises the intriguing possibility that PhoX is more relevant for sulfur acquisition or hydrolysis of diverse P-esters like ATP and polyphosphates in the metabolism of A. mediterranea.

In contrast to the other APase families, PafA exhibited no detectable monoesterase activity (Table 1). This contrasts with Lidbury et al. 2022, which identified PafA enzymes from Bacteroidota as primarily functioning as phosphomonoesterase29. This difference likely reflects variations between PafA enzymes from different bacterial phyla, despite conserved active site geometry (Supplementary Fig. 5). On the other hand, the highest kcat/KM we measured for any enzyme was for the sulfatase activity of PafA (kcat/KM = 15.4 L mmol−1 s−1). This was due to its sub-nanomolar KM for the substrate (KM = 8.3 × 10−7 mmol L−1). Its catalytic efficiency as a sulfatase (kcat/KM = 15.4 L mmol−1 s−1; Table 1) was also 4400-fold higher than the only other quantifiable activity (kcat/KM = 3.5 × 10⁻³ L mmol−1 s−1; Table 1). With additional substrates, PafA exhibited very low activity with ATP and pyro-P, and no phosphate release from Glu-P and tripoly-P.

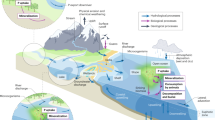

Collectively, the kinetics on our purified marine APases indicate that all families exhibit multifunctional activities with each family displaying a preference for a specific substrate type. PhoA and PhoD exhibited generally high turnover rates for their primary activities, with PhoD also demonstrating elevated catalytic efficiencies for both monoesterase and diesterase activities. In contrast, PhoX and PafA displayed significantly lower turnover rates for their respective primary activities (monoesterase and diesterase) than PhoA and PhoD, highlighting a disparity in catalytic performance among the APase families. In general, triesterase and sulfatase activities exhibited consistently lower turnover rates in comparison to mono and diesterases, across all enzymes. Interestingly, the two APases with highest kcat for diesterases (PhoD and PafA) showcased the highest levels of sulfatase activities as well, indicating a potential link between these two types of activities. This functional overlap likely reflects shared mechanistic and evolutionary features, as diesterases and sulfatases can belong to the same enzyme superfamily and exhibit promiscuous activity toward each other’s substrates36. Such flexibility may have ecological relevance, as some microbes replace phospholipids with sulfolipids when phosphorus is limited37. In addition, recently discovered bacterial capsular polysaccharides in marine systems that contain both sulfate and phosphate groups imply the existence of substrates that require both sulfatase and phosphatase activity for complete degradation38. Furthermore, our empirically obtained results also raise awareness of the greatly distinct roles of different APase families when interpreting bioinformatic data. For example, A. mediterranea PhoA exhibits a maximum velocity rate equivalent to over 30 times that of PhoX, which shows that even a modest percentage in abundance of certain APase families could harbor a degree of enzymatic potential that would be comparable to that of a significantly larger quantity of other APase families. Moreover, other factors besides substrate affinity and kinetics, such as secretion mechanism, can also affect the differential ecological role of APase families in the environment. In fact, we also found that the secretion system differs among APase families: i.e., PhoA and PafA predominantly utilize the Sec pathway for secretion, whereas PhoD and PhoX are primarily transported through the Tat pathway (Fig. 3). This distinction in secretion pathways may confer a significant advantage to enzymes such as PhoD in environments where the availability of trace metals is limited because the Tat pathway allows protein folding prior to secretion, enabling these enzymes to bind the required metal ions in advance. Thus, our findings suggest that understanding the ecological roles of APases in marine environments and beyond is a complex endeavor that requires exploring the interplay of multiple factors across families, such as the secretion mechanisms, enzyme localization (dissolved vs cell-associated), cofactor availability, catalytic potential and multifunctionality. Altogether, our results show that multifunctionality is a common feature across the major marine APase families, suggesting that APases can access a wider range of substrates than previously anticipated (i.e., other than their primary activities). Furthermore, the type of multifunctionality changes depending on the specific APase family, ultimately influencing/driving the potential ecological role of different APases in the ocean.

The phylogenetic trees show a representation of the diversity of oceanic alkaline phosphatase homologs based on The Ocean Microbial Reference Gene Catalog (OM-RGC.v2). The peptides were retrieved with the corresponding Pfam (PhoA) or profile Hidden Markov Models designed for PhoD, PhoX and PafA as described in Methods. Alteromonas mediterranea DE APases were also included, indicated by triangles. Considering that the environmental peptides are more likely to be truncated than those from isolated genomes, they are also more likely to miss the signal peptide at the N-terminal of the sequence.

Alteromonas response to phosphate-limitation: Regulatory mechanisms and multifunctional enzymatic strategies

Supported by the predominance of Alteromonas in APase expression/abundance in the oceanic metatranscriptomic (Fig. 1) and metaproteomic (Fig. 2) datasets, we employed A. mediterranea DE as a model organism for an inorganic phosphate limitation experiment to investigate the proteomic response as well as enzymatic activities under P-limitation. For that purpose, A. mediterranea DE was cultured in artificial seawater with a C:N:P ratio of 50:10:1 µM for the control and 50:10:0.1 µM for the P-limited condition. Our enzymatic rate assays with substrate analogs confirmed that Alteromonas exhibited mono-, di- and triesterase activities (sulfatase below detection limits) (Table 2). When subjected to P-limitation, Alteromonas cultures exhibited markedly higher cell-specific turnover rates for mono- and diesterase, increasing by 10-fold and 20-fold, respectively, compared to the control (Table 2). Proteomic analysis revealed that from all four extracellular APases (all of which contain signal peptides), only PhoD was significantly upregulated under Pi-limitation, ranking under the top 3 of the most upregulated proteins in the overall proteome (Fig. 4). Consistent with our proteomic results, we find that only one APase, phoD, is linked to regulation with a predicted phobox, whereas phoA, phoX, and pafA appear to lack regulation by the phobox in the case of A. mediterranea (Supplementary Fig. 6). This observation aligns with the increased abundance of PhoD under P-stress in the proteome, and its preference for phosphodiesters (based on the kinetics of our recombinants). In soil bacteria like Pseudomonas stutzeri, proteomic analyses of secreted proteins under Pi-depleted conditions have shown that PhoD can become one of the most abundant proteins39. It thus seems that investing in a multi-specific enzyme like PhoD, which exhibits higher catalytic efficiencies (kcat/KM) across multiple substrates compared to other APases (Table 1), may offer a significant advantage during Pi-limitation. PhoD’s catalytic versatility enables Alteromonas to efficiently utilize a wide range of phosphate sources, making it a more cost-effective strategy than relying on multiple specialized phosphatases under P-limited conditions39.

The x-axis represents the log-fold change in protein abundance, calculated as the ratio of the average abundance in P-limited cultures to that in control conditions (in biological triplicates). Positive values on the x-axis indicate proteins upregulated under P-limitation, while negative values indicate downregulation. The y-axis displays the negative logarithm (base 10) of the two-sided t-test p-value. Proteins were considered significantly altered if they had a p-value < 0.05 and were at least two-fold upregulated (log2-fold change > 1.0) or downregulated (log2-fold change < −1.0) and are highlighted as dark points. A two-sided Student’s t-test was used to determine significance. Key proteins implicated in phosphate acquisition are highlighted by color: PhoA (green), PhoD (blue), PhoX (purple), and PafA (pink). Among these, PhoD is the only significantly upregulated protein. Among the alkaline phosphatase families, PhoD stands out as the only protein significantly upregulated during P-limitation.

Interestingly, our enzymatic rate assays revealed mono-, di- and triesterase activities, also under non-P-limited conditions (Table 2). This non-P-limited activity is indicative of the constitutive production of APases like PhoA and PafA (Supplementary Fig. 7). Although the regulation of APases has been described to be generally dependent on ambient concentrations of inorganic phosphate, a recent study showed that PafA is insensitive to phosphate concentrations29. Our results confirm the constitutive production of PafA under both P-limited and non-P-limited conditions, and expand this observation to PhoA in A. mediterranea, which was previously assumed to be regulated by free phosphate (Supplementary Fig. 7). The lack of regulation under P-limitation may explain why PhoA is highly expressed and produced in the deep-ocean waters, where phosphate is highly abundant and should not be limiting (Figs. 1 and 2). This observation aligns with our exo-metaproteome analyses described above, showing that PhoA is the most abundant APase in the cell-free (dissolved) fraction, further supporting a decoupling between its expression and direct cellular P-limitation responses. The biogeochemical and ecological significance of this decoupling is substantial: it implies sustained DOP remineralization independent of immediate cellular P-stress, contributing to background phosphate levels and nutrient regeneration, particularly in the deep-ocean. This is central to resolving the APase paradox and suggests that these constitutively expressed enzymes, especially if stable and cell-free, play an ongoing role in organic matter processing and may also contribute to carbon and sulfur cycling due to their multifunctionality32,33. This decoupling also explains why direct correlations between APase abundance and in situ phosphate concentrations in oceanic datasets are often weak32—the measured enzyme pool reflects a history of production, persistence, and transport rather than just the immediate local nutrient status33,40.

This study provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the regulatory networks and their multifaceted enzymatic potentials of the different APase families in the oceanic water column, offering insights into their ecological roles. Through metaproteome-based analysis of marine APases, we identify PhoA as the dominant APase in the ocean and Alteromonas as a dominant genus in the marine phosphorus cycle, where it significantly drives the expression and production of most APases. This discovery reveals a previously unrecognized key role of Alteromonas, and their APases, in controlling phosphate dynamics in marine environments, particularly in the largest and least studied deep-ocean environment. We also find that they perform this central role using remarkably multifunctional enzymes. Although this multifunctionality is a common feature across the major marine APase families, the type of multifunctionality differs among APase families, ultimately influencing the ecological role of different APases in the ocean. Looking into the mechanistic response of Alteromonas to P-limitation, we find that both strictly regulated and constitutively expressed enzymes are relevant players in P cycling. On one hand, the strict regulation of a multi-specific enzyme like PhoD, exhibiting higher catalytic efficiencies across multiple substrates compared to other APases seems to offer a significant advantage during phosphate limitation. On the other hand, constitutively expressed enzymes such as phoA are produced both during P-limited and non-limited conditions, suggesting that constitutively produced enzymes might be more relevant in the marine elemental (P, C) cycles than hitherto assumed. Our findings indicate that different families of APases can coexist within members of a single genus or even genome, as seen in Alteromonas, because they exhibit distinct substrate specificities, regulatory controls, and secretory pathways (Fig. 5). The co-occurrence of APases with distinct substrate affinities and regulatory mechanisms within the same genome offers a striking example of evolutionary specialization, tailored to adapt to dynamic biogeochemical environments. In this light, further comprehensive studies employing purified enzymes as well as a wider array of substrates would be needed to deepen our understanding of multifunctional enzymes, as they will provide a more nuanced perspective on enzymatic functions and their evolutionary trajectories. Building on APases as an example of multifunctional enzymes, we envision that a deeper exploration of other key enzymes would hold promise for unraveling the complexities of enzyme activities and their behavior in other ecological contexts and biochemical cycles beyond the scope of this study.

This figure illustrates the distinct secretion mechanisms employed by the four purified alkaline phosphatases from Alteromonas mediterranea. The Sec pathway utilized by PhoA (green) and PafA (pink) and the Tat pathway employed by PhoD (blue) and PhoX (purple). These differential secretion strategies suggest an advantage for PhoD and PhoX in acquiring the cofactor iron, as the Tat pathway enables these enzymes to fold before secretion. Conversely, PhoA and PafA rely on external environmental concentrations of their cofactor zinc. The lower part of this figure presents enzymatic turnover rates for four different substrates: P-monoester, P-diester, P-triester, and sulfate monoester. To visualize differences in the lower ranges, the values have been transformed to a logarithmic scale. All four purified enzymes exhibit enzymatic activities with all substrates, except for PafA, which does not show activity with P-monoester. Created in BioRender. Saavedra, D. (2024) https://BioRender.com/ b23b787.

Methods

Identification of alkaline phosphatase in the genomes of marine bacteria and global expression

Alteromonas mediterranea DE was predicted to encode four extracellular APases: PhoA, PhoD, PhoX, and PafA (UniProtKB accession numbers F2G8N3, F2G754, T2DMD9 and F2G994, respectively) as described below. To understand regulatory elements, regulatory sequences upstream of each gene were analyzed. In E. coli and other bacteria, the expression of phosphate scavenging genes are regulated by the pho regulon. Through the concerted action of a σ factor, σ70, genes with a typical phobox in their promoter sequence are regulated by the phosphate concentration41. Phobox sequences were identified using EMBOSS fuzznuc (version 6.6.0.0), referencing known sequences from E. coli41,42. Additionally, regulatory motifs were predicted using MEME (version 5.5.4)43 and FIMO (version 5.1.0)44 both with default parameters, targeting regions within 500 nucleotides upstream of each gene. Identified sequences with a predicted phobox motif in the set of Alteromonas genomes (573 in total) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Each of the four APase families were quantified in the global ocean using 187 metatranscriptomes from the Tara Oceans expedition, corresponding to 109 stations24 and 51 metagenomes for which there were both metatranscriptomes and metagenomes24, following the methods described in Baltar et al., 202345. In brief, the method involves constructing a reference phylogenetic tree for each enzyme and environmental sequences are then placed onto this reference tree to assign a function and a taxonomy. The reference phylogenetic trees were constructed with a set of prokaryotic marine genomes as described in Baltar et al., 202345, along with peptides from eukaryotic genomes in EukProt (version 3)46. Prokaryotic genomes were classified with the GTDB Toolkit (GTDB-Tk, version 2.3.2, database release 214)47. To make the phylogenetic trees for each gene, a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile is needed to search for peptides in the genome database. Depending on the gene, these HMMs were either Pfam or ad hoc HMM profiles, as described below. For PhoA, the reference phylogenetic tree was built using the peptide sequences retrieved from our genome database with its corresponding Pfam profile, PF00245, as described in Baltar et al., 2023. The corresponding Pfam profile for PhoD (PF09423; PhoD-like phosphatase) yielded too many peptide sequences, some of which were likely to be paralogs. For example, a search with the complete genomes in our database predicted some PhoD-like peptides that did not follow any of the secretion pathways and are therefore expected to be cytoplasmic as predicted with SignalP version 6.0 (Supplementary Fig. 8). In this case, a HMM profile was designed for PhoD peptides enriched in TAT and TAT lipoprotein signal peptides that cluster together in the phylogenic tree. Similarly, since too many peptide sequences were retrieved with the corresponding Pfam (PF05787; Bacterial protein of unknown function, DUF839) from our genome database, instead, the PhoX peptides were chosen by their corresponding KOfam, K07093 family, in KEGG orthology using HMMER, version 3.3.2, with its adaptive score threshold48. K07093 corresponds to COG3211 (PhoX Secreted phosphatase, PhoX family) and the number of sequences retrieved from our genome database was smaller than with the Pfam, although the diversity and number of sequences were still too high, suggesting that it also included paralogs. Therefore, another HMM profile was designed for sequences that clustered together and included mostly peptides with a predicted TAT and TAT lipoprotein signal peptide (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 8).

PafA did not correspond to any profile in the KO database. Its corresponding Pfam, PF01663, retrieved too many peptides in our genome database. In this case, an HMM was designed to target PafA in A. mediterranea DE, Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (previously Chryseobacterium meningosepticum) and related sequences classified as PafA in Lidbury et al.29. For both A. mediterranea DE and E. meningoseptica PafA’s there is experimental evidence of their APase activity in this study and in Lidbury et al., 2022, as well as a crystallographically determined structure for E. meningoseptica PafA (PDB ID: 5TJ3)49. Using this structure for E. meningoseptica, we superimposed it using UCSF-Chimera with the AlphaFold-predicted structure of A. mediterranea, revealing a conserved active site and a TM-score of 0.74, despite the relatively low sequence similarity of 22% (Supplementary Fig. 5). The profile HMM retrieved peptides with a predicted Sec and lipoprotein signal peptide (Supplementary Fig. 8). All peptides annotated as ‘alkaline phosphatase PafA’ in RefSeq, 10,424 sequences (RefSeq Release 221, November 13, 2023), were targeted by the HMM designed for PafA.

The contribution to the expression of phosphatase genes in the global ocean was quantified using The Ocean Microbial Reference Gene Catalog (OM-RGC.v2) table of abundances (https://www.ocean-microbiome.org)24 as detailed in Baltar et al., 202345. The OM-RGC.v2 contains genes and associated tables of estimated abundance for the metatranscriptomes and metagenomes in the Tara Oceans database for each sample and after normalization, as detailed in Sunagawa et al.50. Further details on the placement of environmental sequences and quantification of abundance or gene expression are described in the Supplementary. Since the Tara Oceans gene catalog included a functional profile annotated by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gene and Genomes (KEGG) and Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG), a comparison between the quantification of gene expression is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Likewise, the APase peptides were quantified in the metaproteomic study by Zhao et al. 2024, which provided a table of abundances associated to each peptide and sample, as described in their study23. The taxonomic assignment of these peptides to specific genera, such as Alteromonas, was performed using phylogenetic placement onto reference trees. These trees were generated from curated marine genomes (including MAGs and SAGs) following the methods previously described in Baltar et al., 202345. To complement this analysis, Supplementary Fig. 10 displays intensity plots of Alteromonas peptides classified in the four different APase families, with their contribution to the overall proteome quantified as a percentage of the total metaproteome for each sample and an aggregated intensity plot. A comparison of relative protein abundances quantified by the two methods is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, where the data from this study are plotted against abundances reported by Zhao et al. 202423. This comparison demonstrates strong correlations between the methods, further supporting confidence in these results.

Peptides were aligned using MUSCLE version 3.851 and the phylogenetic trees were predicted with FastTree version 2.1.1152 under default settings. The resulting trees were rooted at midpoint (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 8).

Cloning and expression

Four APase gene sequences from A. mediterranea DE were used for de novo biosynthesis. For the transformation step, BL21 DE3 competent cells were transformed with pET29 plasmid encoding one of the four APase genes. Thawed cells were mixed with the DNA and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. Heat shock was performed at 42 °C for 45 seconds, followed by a 2-minute incubation on ice. Next, 400 μl of SOC media (at room temperature) was added, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C and agitation at 250 rpm for at least 1 hour. To initiate expression, 50 μl of the transformation reaction was added to culture tubes containing 5 ml of Luria Broth (LB) media and 5 μl of kanamycin (KAN; final concentration 50 μg/ml). The tubes were then incubated overnight at 37 °C and 250 rpm. For the expression, 1 L of TB media supplemented with KAN (final concentration 50 μg/ml) and 1.5% w/v of lactose was inoculated with a 4 ml of the overnight preculture. The cells were grown at 25 °C and 220 rpm for 24 hours. Afterward, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C and 4000 rpm (2,500 × g) for 30 minutes. To prepare the extract, the pellet was resuspended in 100 ml of lysis buffer and subjected to sonication. A sample from the whole cell-lysate (WC) was taken. The intracellular soluble fraction was obtained by centrifugation at 20000 × g for 30 minutes at 4 °C, and a sample from the soluble fraction (SN) was collected. In the purification process, the cleared lysate (SN) was applied to a 5 ml HisTrap column, pre-equilibrated with IMAC buffer A, at a flow rate of 2 ml/min for IMAC purification with the His Tag. The column was washed with IMAC buffer A until UV readings returned to baseline, followed by a 45 ml wash with 4% IMAC B buffer. Elution of the protein was carried out using varying concentrations of imidazole: 50, 100, 150, 250, and 520 mM. After assessing the purity of different fractions by SDS-PAGE, the 45 ml wash with 4% IMAC B buffer and the 520 mM elution fractions were combined and digested with 3 C protease to remove the His tag. The digestion process took place overnight at 4 °C in dialysis buffer to decrease the imidazole concentration. The next day, the buffer was changed to a fresh dialysis buffer, and dialysis continued for an additional 2 hours. Next, the digested and dialyzed protein solution was injected into a 5 ml HisTrap column, equilibrated with IMAC buffer A. After loading at a rate of 2 ml/min, the column was washed with IMAC buffer A until UV readings returned to baseline, followed by a 45 ml wash with 4% IMAC B buffer. The elution of the 3 C enzyme and the cleaved His tag was achieved using 500 mM imidazole. This step allows binding of the His tag to the column and recovery of the His-tagged 3 C protease, while the flow-through should contain the digested protein of interest. To further purify the protein, the flow-through from the IMAC purification was concentrated to a final volume of 5 ml, corresponding to approximately 65 mg of protein. The concentrated protein solution was then injected into a HiLoad16/600 Superdex200 pg column at a flow rate of 1 ml per minute. Fractions of 1.8 ml were collected, and the purity of each fraction was assessed using SDS-PAGE.

Determination of enzyme kinetic parameters of APase

All APases and enzymatic analysis with Alteromonas were tested for P-monoesterase, P-diesterase, P-triesterase and sulfatase activities using p-nitrophenol based substrates: p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate, bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate sodium salt, Paraoxon-methyl and 4-nitrophenyl sulfate potassium salt, respectively. Measurements were carried out according to previously described methods10. In brief, the enzymes catalyzed the release of the chromogenic product p-nitrophenol from the stated substrates and measured in technical triplicates with a microplate reader (TECAN, Infinite 200 PRO) in volumes of 300 µl at 405 nm wavelength. All experiments were performed using filter sterilized (0.2 µm) artificial seawater, specifically Aquil* culture medium at a pH of 8.1 without major nutrients (P, N, Si) or vitamins53. To ensure the presence of all required cofactors, including trace metals that can influence the physiology of marine microbes54, we supplemented the medium with the highest concentrations observed in the open ocean MnCl2 (5 nM), FeCl3 (2 nM), NiCl3 (12 nM), ZnSO4 (9 nM), Na2SeO3 (2.3 nM) and Na2MoO4 (105 nM)55. For each substrate and substrate concentration, blank controls were run without the addition of any enzyme, and the obtained values were subtracted from the corresponding substrate results. The enzyme concentration varied depending on the substrate: 1 nM for p-nitrophenyl phosphate and bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate, and 10 nM for Paraoxon-methyl and 4-nitrophenyl sulfate. Kinetic parameters, kcat, KM and the catalytic efficiency kcat/KM values, were calculated as described in Srivastava et al. 202110. Calculations and visualizations were done in R (Supplementary Fig. 12).

To assess the substrate multifunctionality of the enzymes, additional activity assays were conducted using a range of alternative organophosphorus substrates. The substrates tested included glucose-6-phosphate (Glu-P), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), pyrophosphate (pyro-P), tripolyphosphate (tripoly-P), and methylphosphonate (P-nate). Each substrate was tested at a final concentration of 100 µM with 10 nM of enzyme. These reactions were performed in the same Aquil* based artificial seawater medium as the p-nitrophenol-based assays. The release of inorganic phosphate was quantified using the Malachite Green Phosphate Assay Kit (MAK307, Sigma-Aldrich). The enzymatic reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 minutes. Following this, the Malachite Green Working Reagent was added, and the mixture was incubated for an additional 30 minutes at room temperature to allow for color development. The amount of phosphate released was determined by comparing the absorbance at 620 nm to a standard curve generated from a serial dilution of the provided 1 mM phosphate standard.

To determine enzymatic half-life, APases were incubated in Artificial Seawater (ASW) at 24 °C. To ensure measurements remained within the linear range of detection, PhoA was used at 10 nM, while PhoD, PhoX, and PafA were used at 100 nM. Activity was measured in triplicate periodically over 60 days (Supplementary Fig. 3). The P-monoesterase activity of PhoA, PhoD, and PhoX was assessed using the fluorogenic substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl (MUF)-phosphate (200 µM). The phosphodiesterase activity of PafA was assessed using Bis 4-MUF phosphate (200 µM). Product formation was quantified on a microplate reader (365 nm excitation, 445 nm emission) by comparison to a MUF standard curve. The half-life (t1/2) was calculated by fitting the activity rates over time (data shown in Supplementary Fig. 3) to a first-order exponential decay model (ratet = rate0⋅e−kt) using non-linear least squares regression. From this model, the decay constant (k) was determined, and the half-life was subsequently calculated using the formula t1/2 = ln(2)/k.

Alteromonas mediterranea growth and sample preparation

A. mediterranea strain DE was purchased from the Leibniz-Institut Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ No.: 17117). The main salts for the medium were prepared according to the Aquil* medium formula56. The media contained 50 µM of carbon in the form of glucose, NH4Cl (10 µM), KH2PO4 (1 µM for the control and 0.1 µM for P-limitation), vitamin B12 (0.37 nM) and the following trace metals: MnCl2 (5 nM), FeCl3 (2 nM), NiCl3 (12 nM), ZnSO4 (9 nM), Na2SeO3 (2.3 nM) and Na2MoO4 (105 nM). Trace metal concentrations used in this study reflect the highest levels observed in the open ocean55. Additionally, for testing growth conditions with monoesters as a sole P source (Supplementary Fig. 13) adenosine-monophosphate (AMP; Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Since, 1 µM of AMP (C10H14N5O7P) already contains 10 µM of carbon and 5 µM of nitrogen, to maintain a C:N:P ratio of 50:10:1, only 40 µM of carbon in the form of glucose and 5 µM of NH4Cl were added. The AMP+Pi culture was prepared with an additional 1 µM of KH2PO4. Cell abundance was measured after fixing with glutaraldehyde (2% v/v final concentration) via flow cytometry using an Accuri™ C6 Plus Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, USA) and stained with 1x SYBR® Green I (Sigma-Aldrich). The cultures were inoculated to a starting cell density of 1 × 104 cells/L. All different treatments were cultivated in biological triplicates of 400 ml and in a shaker (100 rpm) at 15 °C. Cells were harvested during early stationary phase (after 38 hours, Supplementary Fig. 13). Enzymatic measurements were conducted as described above with whole cells. Only cultures that showed a clear distinction in growth and enzymatic potential (control 1 µM phosphate and P-limited 0.1 µM phosphate, Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Table 1) were further collected for protein extraction. Approximately 200 ml per treatment was utilized and filtered through a 0.22-μm pore-size polycarbonate membrane (47 mm diameter). The lysis buffer was prepared with the following concentrations: 50 mM Tris-HCl adjusted to pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Triton X-100; 0.1% SDS; 1 mM EDTA; and one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Thermo Scientific). The filters were covered with lysis buffer and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles alternating between −80 °C and +80 °C. For precipitation, ice-cold EtOH was added in a 9:1 ratio, followed by storage at −20 °C overnight, and pelleted down by centrifugation for 30 minutes at 14,000 rpm (13,150 × g) at 4 °C. The pellet was air-dried at room temperature for 30 minutes. The protein pellet was re-suspended in 50 µl of 50 mM TEAB buffer. To this mixture, 1 µl of the reduction buffer (with a final DTT concentration of 20 mM) was added, followed by incubation at 60 °C for 30 minutes. After cooling to room temperature, 1 µl of the alkylation buffer (with a final iodoacetamide concentration of 20 mM) was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. Subsequently, trypsin digestion was performed with a concentration of 1 µg trypsin per 100 µl sample (MERCK Trypsin Sequencing Grade) and incubated at 37 °C for 16 hours. The reaction was halted by adding trifluoroacetic acid with a final concentration of 1%. Desalting was performed using Pierce™ C18 Tips following Thermo Scientific’s instructions. After drying the peptides in a speed vacuum, the samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated during this study are available in the Zenodo repository under accession code 10.5281/zenodo.15714811 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15714811). The publicly available datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the Tara Oceans project (https://www.ocean-microbiome.org) and the study by Zhao et al. (2024)23.

Code availability

All scripts generated and used in this study are available in the Zenodo repository under accession code 10.5281/zenodo.15714811 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15714811).

References

Karl, D. M. & Björkman, K. M. Dynamics of Dissolved Organic Phosphorus. in Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter: Second Edition 233–334 (2015). 10.1016/B978-0-12-405940-5.00005-4.

Thomson-Bulldis, A. & Karl, D. Application of a novel method for phosphorus determinations in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 1565–1577 (1998).

Kolowith, L. C., Ingall, E. D. & Benner, R. Composition and cycling of marine organic phosphorus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 309–320 (2001).

Young, C. L. & Ingall, E. D. Marine dissolved organic phosphorus composition: Insights from samples recovered using combined electrodialysis/reverse osmosis. Aquat. Geochem 16, 563–574 (2010).

Azam, F. & Malfatti, F. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 782–791 (2007).

Karl, D. M. & Microbially mediated transformations of phosphorus in the sea: New views of an old cycle. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6, 279–337 (2014).

Sunden, F. et al. Differential catalytic promiscuity of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily bimetallo core reveals mechanistic features underlying enzyme evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 20960–20974 (2017).

Khersonsky, O. & Tawfik, D. S. Enzyme promiscuity: A mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev. Biochem 79, 471–505 (2010).

Wienhausen, G., Noriega-Ortega, B. E., Niggemann, J., Dittmar, T. & Simon, M. The exometabolome of two model strains of the Roseobacter group: A marketplace of microbial metabolites. Front Microbiol 8, (2017).

Srivastava, A. et al. Enzyme promiscuity in natural environments: alkaline phosphatase in the ocean. ISME J. 15, 3375–3383 (2021).

Sone, M., Kishigami, S., Yoshihisa, T. & Ito, K. Roles of disulfide bonds in bacterial alkaline phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 6174–6178 (1997).

Wu, J. R. et al. Cloning of the gene and characterization of the enzymatic properties of the monomeric alkaline phosphatase (PhoX) from Pasteurella multocida strain X-73. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 267, 113–120 (2007).

Yamane, K. & Maruo, B. Alkaline phosphatase possessing alkaline phosphodiesterase activity and other phosphodiesterases in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 134, 108–114 (1978).

Yong, S. C. et al. A complex iron-calcium cofactor catalyzing phosphotransfer chemistry. Science (1979) 345, 1170–1173 (2014).

Duhamel, S. et al. Phosphorus as an integral component of global marine biogeochemistry. Nat. Geosci. 14, 359–368 (2021).

Coleman, J. E. Structure and mechanism of alkaline phosphatase. Annu Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 21, 441–483 (1992).

Ali, A. F. & Hamza, B. N. Purification and characterization of alkaline phosphotase enzyme from the periplasmic space of Escherichia coli C90 using different methods. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 20, 125–135 (2012).

López-Canut, V., Roca, M., Bertrán, J., Moliner, V. & Tuñón, I. Promiscuity in alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Unraveling evolution through molecular simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 12050–12062 (2011).

Pabis, A., Duarte, F. & Kamerlin, S. C. L. Promiscuity in the Enzymatic Catalysis of Phosphate and Sulfate Transfer. Biochemistry 55, 3061–3081 (2016).

Van Loo, B. et al. An efficient, multiply promiscuous hydrolase in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2740–2745 (2010).

Jonas, S. & Hollfelder, F. Mapping catalytic promiscuity in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. in. Pure Appl. Chem. 81, 731–742 (2009).

Duarte, F., Amrein, B. A. & Kamerlin, S. C. L. Modeling catalytic promiscuity in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 11160–11177 (2013).

Zhao, Z. et al. Metaproteomic analysis decodes trophic interactions of microorganisms in the dark ocean. Nat Commun 15, (2024).

Salazar, G. et al. Gene Expression Changes and Community Turnover Differentially Shape the Global Ocean Metatranscriptome. Cell 179, 1068–1083.e21 (2019).

Koike, I. & Nagata, T. High potential activity of extracellular alkaline phosphatase in deep waters of the central Pacific. Deep Sea Res 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 44, 2283–2294 (1997).

Hoppe, H. G. Phosphatase activity in the sea. Hydrobiologia 493, 187–200 (2003).

Baltar, F. et al. Prokaryotic extracellular enzymatic activity in relation to biomass production and respiration in the meso- and bathypelagic waters of the (sub)tropical Atlantic. Environ. Microbiol 11, 1998–2014 (2009).

Baltar, F. et al. High dissolved extracellular enzymatic activity in the deep central Atlantic ocean. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 58, 287–302 (2010).

Lidbury, I. D. E. A. et al. A widely distributed phosphate-insensitive phosphatase presents a route for rapid organophosphorus remineralization in the biosphere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 119, (2022).

Balabanova, L. et al. LPS-Dephosphorylating Cobetia amphilecti Alkaline Phosphatase of PhoA Family Divergent from the Multiple Homologues of Cobetia spp. Microorganisms 12, 631 (2024).

Hou, L. et al. Microbial metabolism in laboratory reared marine snow as revealed by a multi-omics approach. Microbiome 2025 13:1 13, 1–18 (2025).

Thomson, B. et al. Resolving the paradox: Continuous cell-free alkaline phosphatase activity despite high phosphate concentrations. Mar. Chem. 214, 103671 (2019).

Baltar, F. Watch out for the ‘living dead’: Cell-free enzymes and their fate. Front Microbiol 8, 1–6 (2018).

Baltar, F., De Corte, D., Thomson, B. & Yokokawa, T. Teasing apart the different size pools of extracellular enzymatic activity in the ocean. Sci. Total Environ. 660, 690–696 (2019).

Rodriguez, F. et al. Crystal structure of the Bacillus subtilis phosphodiesterase PhoD reveals an iron and calcium-containing active site. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 30889–30899 (2014).

Lassila, J. K. & Herschlag, D. Promiscuous sulfatase activity and thio-effects in a phosphodiesterase of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Biochemistry 47, 12853–12859 (2008).

Moran, M. A. & Durham, B. P. Sulfur metabolites in the pelagic ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 665–678 (2019).

Kokoulin, M. S., Savicheva, Y. V., Filshtein, A. P., Romanenko, L. A. & Isaeva, M. P. Structure of a sulfated capsular polysaccharide from the marine bacterium cobetia marina KMM 1449 and a genomic insight into its biosynthesis. Mar. Drugs 23, 29 (2025).

Lidbury, I. D. E. A. et al. Comparative genomic, proteomic and exoproteomic analyses of three Pseudomonas strains reveals novel insights into the phosphorus scavenging capabilities of soil bacteria. Environ. Microbiol 18, 3535 (2016).

Arnosti, C. Microbial extracellular enzymes and the marine carbon cycle. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 401–425 (2011).

Makino, K. et al. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli. Activation of pstS transcription by PhoB protein in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 203, 85–95 (1988).

Gardner, S. G. & McCleary, W. R. Control of the phoBR Regulon in Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus 8, (2019).

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E. & Noble, W. S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res 43, W39–W49 (2015).

Grant, C. E., Bailey, T. L. & Noble, W. S. FIMO: Scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27, 1017–1018 (2011).

Baltar, F. et al. A ubiquitous gammaproteobacterial clade dominates expression of sulfur oxidation genes across the mesopelagic ocean. Nat. Microbiol 8, 1137–1148 (2023).

Richter, D. J. et al. EukProt: A database of genome-scale predicted proteins across the diversity of eukaryotes. Peer Commun. J 2, (2022).

Chaumeil, P. A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: A toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925–1927 (2020).

Aramaki, T. et al. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 36, 2251–2252 (2020).

Sunden, F. et al. Mechanistic and Evolutionary Insights from Comparative Enzymology of Phosphomonoesterases and Phosphodiesterases across the Alkaline Phosphatase Superfamily. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14273–14287 (2016).

Sunagawa, S. et al. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science (1979) 348, 1–10 (2015).

Edgar, R. C. Muscle5: High-accuracy alignment ensembles enable unbiased assessments of sequence homology and phylogeny. Nat Commun 13, (2022).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. Fasttree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Sunda, W. G., Price, N. M. & Morel, F. M. M. Trace Metal Ion Buffers and Their Use in Culture Studies. in Algal Culturing Techniques 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012088426-1/50005-6 (2005).

Baltar, F., Stuck, E., Morales, S. & Currie, K. Bacterioplankton carbon cycling along the Subtropical Frontal Zone off New Zealand. Prog. Oceanogr. 135, 168–175 (2015).

Bruland, K. W., Middag, R. & Lohan, M. C. Controls of trace metals in seawater. Treatise Geochem.: Second Ed. 8, 19–51 (2013).

Andersen, R. A., Berges, J. A., Harrison, P. J. & Watanabe, M. M. Recipes for Freshwater and Seawater Media. Algal Culturing Techniques 429–538 https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012088426-1/50027-5 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) projects OCEANIDES (P34304-B), ENIGMA (TAI534), EXEBIO (P35248), and OCEANBIOPLAST (P35619-B) granted to F.B. J.M.G. was supported by the project PID2023-146919NB-C22 (Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Spanish State Research Agency, doi: 10.13039/501100011033). We wish to thank Zihao Zhao for his valuable guidance and mentorship during the laboratory work and proteomic analyses. A special thanks to Ana Iriarte Díez for her invaluable linguistic assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.E.M.S. and F.B. conceived the study. D.E.M.S. and K.K. performed experiments. J.M.G. LC-MS analysis was performed by L.A.S. D.E.M.S., J.M.G., F.B. and K.K. analyzed the data. E.B., S.B., L.L. and X.D. contributed to the manuscript revision. W.M.P. aided with data interpretation. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saavedra, D.E.M., González, J.M., Klaushofer, K. et al. Multifunctionally diverse alkaline phosphatases of Alteromonas drive the phosphorus cycle in the ocean. Nat Commun 16, 9789 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64455-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64455-2