Abstract

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a key ocean-atmospheric mode that affects global weather and climate through atmospheric teleconnections. It remains unclear how robust and stable ENSO teleconnection patterns are under external perturbations. Here, we use observations to demonstrate that volcanic eruptions disrupt ENSO teleconnections with land surface air temperature in boreal summer across the globe. During eruption years, correlations are found to shift in 62.27% of regions where temperature is significantly connected to ENSO during non-eruption years. State-of-the-art Earth System Models fail to capture this disruptive effect, highlighting challenges in simulating the patterns of climate anomalies and extremes under external perturbations. The disruptive effect identified here raises questions about the stationarity assumption in ENSO reconstructions based upon temperature-sensitive proxy records. Our findings call for an improved characterization of regional climate impacts following volcanic eruptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), featuring sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies over the east-central tropical Pacific, is a leading ocean-atmospheric mode that affects worldwide weather and climate patterns1,2,3,4. The tropical Pacific oscillates between warm and cold phases, known as El Niño and La Niña, every 2–7 years5,6,7,8,9. ENSO imposes great impacts on global climate10,11,12, terrestrial ecosystems13, and human society14 through large-scale and far-reaching patterns known as atmospheric teleconnections6,8,15,16. Understanding the stationarity of ENSO teleconnection patterns is of enormous importance for weather forecast, climate prediction, and sustainable development under global warming.

ENSO variability originates from both internal and external forcings such as volcanic eruptions17,18. Empirical studies, mostly based on tree-ring reconstructions, suggest an El Niño-like response within 2 years following volcanic eruptions9,19, whereas some coral records from the core ENSO regions demonstrate no consistent response20. This conundrum also exists in the Earth System Model (ESM) simulations, which support an El Niño21,22, no clear signal23,24, and a La Niña25 state 1 year following volcanic eruptions. Recent studies further highlight the role of Pacific pre-conditions26,27 and the location, timing, and magnitude of volcanic eruptions27,28,29 in ENSO development. Such elusive associations between ENSO and volcanic eruptions illustrate the challenges in simulating climate anomalies and extremes under external perturbations caused by volcanic eruptions and solar geoengineering30. Thus, it is imperative to assess the fidelity of ENSO reconstructions and simulations in response to volcanic eruptions, so as to discern the nature of forced ENSO variability.

A crucial assumption in ENSO reconstruction is the stationary relationship between ENSO and proxy records, whereby the model calibrated during the instrumental period is valid over the past8,9,17. Nevertheless, volcanic eruptions inject a large amount of sulfate aerosols into the atmosphere, which influence the balance of incoming and outgoing radiation and disrupt large-scale atmospheric circulations31,32,33. The resulting climate anomalies are recorded by worldwide proxies, yet in teleconnection regions such climate effects may not be connected to ENSO states as assumed during non-eruption years20,34. Thus, volcanic eruptions likely impose a disruptive effect on global ENSO teleconnections9,20,34. ENSO reconstructions based upon paleoclimate proxies from teleconnection regions may be negated by the climate effects of volcanic eruptions, and do not reflect true ENSO states in the east-central tropical Pacific. In view of this, a critical evaluation of the ENSO teleconnections following volcanic eruptions is imperative to scrutinize our knowledge of ENSO and its global impacts under external perturbations.

The ENSO modulates global temperature variability and extremes through atmospheric teleconnections, particularly in boreal summer16,35,36,37,38,39. However, whether volcanic eruptions disrupt the ENSO-temperature teleconnections remains unclear. In this study, we investigate the impacts of volcanic eruptions on ENSO teleconnections with land surface air temperature (\({T}_{a}\)) using modern observations from 1901 to 2022 (Methods). The peak ENSO phase5,6,9, denoted by December-to-February (DJF) Niño 3.4, is employed to represent the ENSO variability. This index has been reconstructed in many previous studies to characterize ENSO response to volcanic eruptions8,9,17. We select 14 volcanic eruptions with volcanic explosivity index40,41 (VEI) of 5 or higher during the 1901–2022 period to identify the years impacted (Vol, n = 34) and not impacted (NVol, n = 88) by volcanic eruptions (“Methods”; Supplementary Table 1). ENSO teleconnections with \({T}_{a}\) are compared between the NVol and Vol years to demonstrate the disruptive effect of volcanic eruptions on atmospheric circulations. We further diagnose this disruptive effect in state-of-the-art ESMs participating in the sixth phase of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), and reconstruct DJF Niño 3.4 using the observed \({T}_{a}\) as predictors to measure uncertainties in previous reconstructions based upon temperature-sensitive proxies. The results will provide crucial constraints on ENSO reconstructions and hydroclimate simulations under natural and/or anthropogenic aerosol perturbations.

Results

Disrupted ENSO teleconnections with land summer temperature

We explore the ENSO teleconnections by calculating the correlation between DJF Niño 3.4 and global \({T}_{a}\) in boreal summer (June-August) following the peak ENSO phase. Given the time frame of volcanic eruptions on ENSO and its teleconnections9,32,42, all series are 15-year high-pass filtered with the removal of 1901–2022 mean (“Methods”; Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), unless otherwise noted. During 1901–2022, DJF Niño 3.4 shows a strong correlation (r = 0.62, p < 0.01) with global \({T}_{a}\) during the NVol years, demonstrating the crucial role of ENSO in modulating global temperature variability (Fig. 1a, b). This result is consistent with previous understanding that El Niño (La Niña) is linked to global-scale warming (cooling) in the next summer43. However, the correlation between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) drops to 0.07 during the Vol years (Fig. 1c). This decrease in correlation unlikely occur by chance because the correlation between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) during Vol years is lower than the 1% quantile of those resampled from NVol years (Fig. 1d). Together, these results suggest that the strong connection between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) that prevails during NVol years is disrupted during Vol years.

a Time series of inter-annual December-to-February (DJF) Niño 3.4 and global land surface air temperature (\({T}_{a}\)) anomalies in the boreal summer (June-August) following the peak ENSO phase. Bottom asterisks denote the start years of selected volcanic eruptions (\({{{\rm{VEI}}}}\ge 5\)), which identify the years impacted (Vol) and not impacted (NVol) by volcanic eruptions. The dots indicate Vol years. b, c Comparison between DJF Niño 3.4 and global \({T}_{a}\) anomalies during NVol (b) and Vol (c) years. The green dot in c highlights the El Niño phase and a global cooling following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. d Probability distribution of the correlations between DJF Niño 3.4 and global \({T}_{a}\) anomalies during NVol years using 1000 bootstrapping repeats with the same size as Vol years. Vertical red line denotes observed correlation (r = 0.07) during Vol years, and vertical blue lines mark the 1% and 5% quantiles of the resampled correlations during NVol years.

The disruptive effect of volcanic eruptions on ENSO-temperature teleconnections is evident not only in the boreal summer but also during the March-September time window (Supplementary Fig. 3). To demonstrate the robustness of this disruptive effect, we select a subset of volcanic eruptions during the early and late halves of the 20th century, and find that they all display remarkable reduction in the correlations between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) in Vol years compared to NVol years (Supplementary Table 2). The disruption of ENSO teleconnections is also evident using alternative volcanic eruption datasets44,45,46, volcanic eruptions at different latitudes, the relative Niño 3.4 index47,48, and other methods for preserving inter-annual variability (Supplementary Figs. 4–8). Furthermore, DJF Niño 3.4 and the percentage of El Niño and La Niña are uniformly distributed between the NVol and Vol years, suggesting symmetrical impacts of El Niño and La Niña on extratropical climate (Supplementary Fig. 9). Relationship between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) also remains stable since 1901, which reduces the influence of changes in ENSO dynamics that shift its teleconnections (Supplementary Fig. 10). Together, these findings confirm that volcanic eruptions disrupt ENSO effects on global \({T}_{a}\).

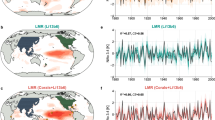

To demonstrate the spatial complexity of temperature responses, we calculate the gridded correlations between DJF Niño 3.4 and boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) during NVol and Vol years, respectively (Fig. 2; “Methods”). Correlation maps show that ENSO positively influences \({T}_{a}\) in most land areas during NVol years (Fig. 2a), consistent with previous understanding that El Niño (La Niña) is linked to global-scale warming (cooling) in the next summer43. However, under the influence of volcanic eruptions, these significant positive correlations are shifted to non-significant correlations (denoted as P_NS) in vast regions of Africa, Greenland, eastern North America, and some regions of Eurasia, Australia, and South America, which account for 27.40% of global land areas (Fig. 2b–d). Temperature in around 16.88% of global land areas display consistently positive response to ENSO (denoted as P_P), which are mainly located in tropical regions in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia, and northern South America (Fig. 2c, d). Summer temperature in central northern Eurasia, eastern North America, and the Mediterranean region exhibits negative correlations with ENSO during Vol years, highlighting the disrupted ENSO-temperature teleconnections in most mid- to high-latitude regions (Fig. 2b). Overall, 44.74% of global areas exhibit significant correlations (P_* and N_*) with ENSO during NVol years, and the correlations (P_NS, P_N, N_P, and N_NS) are found to shift in 27.86% of global areas. Thus, around 62.27% (27.86%/44.74%) of areas where summer \({T}_{a}\) is significantly connected to ENSO during NVol years have been disrupted by volcanic eruptions (Fig. 2d). We confirm the disruptive effect of volcanic eruptions by calculating the sensitivity of boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) to DJF Niño 3.4 index (Methods). Results show that the positive responses of \({T}_{a}\) to DJF Niño 3.4 have greatly lowered from NVol to Vol years (Supplementary Fig. 11). For the regions where \({T}_{a}\) shows significant positive correlations with DJF Niño 3.4 during NVol years, the sensitivity decreases from \(0.14\pm 0.06\) °C/°C (mean \(\pm\) standard deviation) to \(0.07\pm 0.12\) °C/°C (Supplementary Fig. 12). Thus, volcanic eruptions weaken or even reverse the boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) responses to ENSO in most mid- to high-latitudes, which contribute to their decoupling at the global scale.

Correlations between DJF Niño 3.4 and boreal summer land surface air temperature (\({T}_{a}\)) during the years not impacted (NVol; a) and impacted (Vol; b) by volcanic eruptions. Stippling denotes significance at the 0.05 level. Spatial pattern of the changed correlations (c) from NVol to Vol years and their areal percentage (d). Correlations from NVol to Vol years are separated by “_”, with “N”, “NS”, and “P” representing significant negative, non-significant, and significant positive correlations, respectively. The “P_NS”, for example, denotes a shift from a significant positive correlation during NVol years to a non-significant correlation during Vol years.

Volcanic eruptions influence atmospheric dynamics by exerting both radiative heating and cooling effects33,42,49. Zonally averaged geopotential height anomalies in the next summer are regressed onto DJF Niño 3.4 to show the shifts in atmospheric circulations following volcanic eruptions (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Fig. 13). During NVol years, ENSO regulates stratospheric and upper-tropospheric atmospheric circulations in most latitudes north of 40°S (Fig. 3a), consistent with its significant influence on boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) at a global scale (Fig. 2a). However, following volcanic eruptions, ENSO mostly influences tropical atmospheric circulations and exerts non-significant or even negative influence on mid- and high-latitude air pressures (Fig. 3b). These volcanic-induced changes in atmospheric circulations underpin the greatly reduced teleconnections between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) following volcanic eruptions (Fig. 2b, c). To reveal atmospheric circulations forced by volcanic eruptions, we composite geopotential height anomalies during NVol and Vol years (Fig. 3c, d; Supplementary Fig. 14). During Vol years, stratospherically loaded aerosols absorb upwelling infrared radiation33,42 and increase stratospheric geopotential heights at mid-latitudes of both hemispheres (Fig. 3d). The backscattering of solar radiation concurrently decreases tropical air temperature in troposphere33,50 (Supplementary Fig. 15), which likely contributes to negative tropospheric geopotential height anomalies at around 45°N and 25°S. Meanwhile, tropical cooling following volcanic eruptions has been linked to anomalies in North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)50 and Arctic Oscillation49, which also influence tropospheric atmospheric circulations51. Thus, volcanic eruptions disrupt stratospheric and tropospheric atmospheric circulations at mid-latitudes of both hemispheres, which suppress or even block ENSO teleconnections and contribute to its decoupling with global \({T}_{a}\) in boreal summer.

Zonally averaged geopotential height anomalies in boreal summer regressed onto December-to-February (DJF) Niño 3.4 during the years not impacted (NVol; a) and impacted (Vol; b) by volcanic eruptions from the surface to 10-hPa level. Composite zonally averaged geopotential height anomalies in boreal summer during NVol (c) and Vol (d) years. Stippling denotes significance at the 0.05 level. Zonally average geopotential height anomalies are normalized at individual pressure levels in the unit of standard deviation.

Evaluation of CMIP6 models

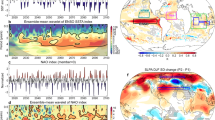

The observational evidence of disrupted ENSO teleconnections provides a crucial constraint on the climate impacts of volcanic eruptions in ESM simulations. We calculate the correlations between boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) and DJF Niño 3.4 in the historical (1901-2014) simulations of CMIP6 models (Fig. 4a). The Vol years are identified based on global mean stratospheric aerosol optical depth in historical forcing datasets52,53 (Methods). At the global scale, CMIP6 models present a large spread for the correlations between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) during NVol years, and fail to reproduce the greatly decreased correlation during Vol years. In mid- and high-latitudes, ESMs produce very similar ENSO teleconnection patterns between the NVol and Vol years (Fig. 4b, c), which contradicts the shifted correlations that are evident in observations (Fig. 2c). Specifically, ESM simulations underestimate the positive correlations in eastern United States and Greenland during NVol years, and do not reproduce the shift toward non-significant or negative correlations in Africa, central northern Eurasia, and eastern North America during Vol years. The aforementioned limitations suggest uncertainties in simulating hydroclimate response to ENSO and large volcanic eruptions22,54. Likewise, data assimilations that rely on large-scale climate simulations may underrepresent ENSO teleconnections and their shifts in response to volcanic eruptions. Furthermore, CMIP6 designs a set of experiments to assess hydroclimate changes after the implementation of radiation modification geoengineering projects30,55,56. Our results suggest that summer \({T}_{a}\) in mid- and high-latitude regions impacted by ENSO teleconnections may not be accurately simulated by current ESMs under designed aerosol forcings.

a Ensemble median correlations between December-to-February (DJF) Niño 3.4 and global land surface air temperature (\({T}_{a}\)) in boreal summer during the years not impacted (NVol) and impacted (Vol) by volcanic eruptions from observations, historical multi-model ensemble (MME) median simulations, and individual CMIP6 models. The Vol years are identified based on global mean stratospheric aerosol optical depth in both observations and historical simulations during 1901–2014. Error bars represent the standard deviations of bootstrap resamples in observations and multi-model ensemble simulations in CMIP6 experiments. Ensemble median correlations between DJF Niño 3.4 and boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) during NVol (b) and Vol (c) years in CMIP6 simulations. Stippling denotes regions where at least 23 out of 25 models (92%) show the same sign of correlations.

To diagnose the discrepancies with observations, we regress zonally averaged geopotential height anomalies onto DJF Niño 3.4 in historical simulations (Supplementary Fig. 16a, b). During NVol years, ESMs reproduce ENSO modulations on tropical atmospheric circulations but underestimate its significant teleconnections with mid- and high-latitude climate. Volcanic eruptions do not significantly change ENSO teleconnections with global atmospheric circulations in historical simulations, although responses in composite geopotential heights are captured by ESM simulations (Supplementary Fig. 16). Climate models also demonstrate large inconsistencies in water vapor content that affects meridional temperature gradient and North Atlantic jet50,57, suggestive of the uncertainties in simulating mid-latitude climate anomalies following volcanic eruptions33. Thus, present CMIP6 models have limited skills in simulating ENSO teleconnections with mid- and high-latitude climate during NVol years, and fail to capture the disruptive effects arising from volcanic forcings. This calls for improved understanding and characterization of ENSO and volcanic forcing as well as their interactions with large-scale climate anomalies in future ESMs.

Implications for ENSO reconstructions

The disruptive effect of volcanic eruptions undermines ENSO reconstructions based upon temperature-sensitive terrestrial proxies. During NVol years, a globally warm and dry condition is usually associated with El Niño12,43,58,59. This relationship is assumed in historical reconstructions due to the dominance of NVol years. However, our results indicate that volcanic eruptions disrupt this relationship, resulting in biases in ENSO reconstructions following large volcanic eruptions. Here we assess this influence by reconstructing DJF Niño 3.4 using boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) as predictors. Principal components regression model8,9, which is widely used in paleoclimatology, is employed to emulate previous ENSO reconstructions (Methods). The disruptive effect reduces the fidelity of ENSO reconstructions during the Vol years, despite consistently strong response to ENSO in tropical and southern hemispheric temperature (Fig. 5a). Additionally, we use a random forest model to account for the non-linearity between principal components, and achieve similar results (Supplementary Fig. 17). Therefore, previous ENSO reconstructions incorporating extratropical temperature-sensitive proxies as predictors probably suffer from this error during Vol years.

a Correlations between the observed and reconstructed December-to-February (DJF) Niño 3.4 using global, Northern Hemispheric (NH), Southern Hemispheric (SH), and tropical land surface air temperature (\({T}_{a}\)) in boreal summer as predictors during the years not impacted (NVol) and impacted (NVol) by volcanic eruptions. Asterisks denote the 0.05 significance level. Time series of DJF Niño 3.4 observations and reconstructions following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo (b), 1912 eruption of Novarupta (c), and 1902 eruption of Santa Maria (d). Vertical blue arrows denote years with marked difference between observations and reconstructions. Start dates of eruptions are shown on top left.

We further examine the changes in ENSO variability influenced by three largest (\({{{\rm{VEI}}}}\,=\,6\)) volcanic eruptions during our reconstruction period. Observed SSTs in ENSO region show a tendency toward positive anomalies in the eruption year of 1912 Novarupta and the first year following the 1991 Mount Pinatubo and 1902 Santa Maria eruptions (Fig. 5b–d). However, ENSO reconstructions based upon boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) manifest neutral or even cool responses, contradicting the observed El Niño-like conditions in these years. These results indicate that the dominant modes in land summer temperature cannot accurately reproduce ENSO variability following large volcanic eruptions. This inherent bias may have misled our understanding of the forced ENSO variability under large volcanic eruptions based upon remote temperature-sensitive proxy records. For the NVol years and Vol years with \({{{\rm{VEI}}}}=5\), tropical temperature captures well ENSO variability, suggesting the fidelity of ENSO reconstructions over these periods (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19).

Existing ENSO reconstructions include many temperature-sensitive proxy records in mid- and high-latitudes as candidate predictors, such as tree rings, ice cores, and lake sediments9,17,60,61,62. The inclusion of these proxy records is likely to improve the reconstruction performance during the calibration period. However, our assessment based upon observed temperature indicates that such an approach may introduce errors in ENSO reconstructions following large volcanic eruptions. This bias is not significant during the calibration period as tropical proxy records are ample to reproduce the indigenous ENSO variability during the 20th century. However, the bias may become increasingly pronounced back in time owing to the shrinking ratio of tropical to extratropical proxy records. To avoid this disruptive effect, paleoclimate proxies in regions showing stationary teleconnections as revealed in our study should be prioritized in future ENSO reconstructions.

Discussion

Our study presents observational evidence for the disruptive effect of volcanic eruptions on ENSO teleconnection patterns. The close connection between ENSO and boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) is disrupted within 1–3 years following large volcanic eruptions. Instead, climate impacts of sulfate aerosols likely shift ENSO teleconnections and modulate hydroclimate variations in mid- and high-latitude regions. We diagnose the historical simulations of CMIP6 models and find that they fail to capture this disruptive effect, raising questions regarding their hydroclimate simulations following volcanic eruptions. This disruptive effect also raises concerns at ENSO reconstructions based upon extratropical temperature-sensitive proxies and questions our understanding of ENSO and its response to external perturbations. Validating the stationarity of teleconnection patterns is essential for future reconstructions of ENSO and other large-scale climate modes. Given that external perturbations can affect ENSO and its global teleconnections, additional efforts should be made to fully identify their spatial complexity, dynamical mechanisms, and interactions with other large-scale climate modes.

The disruptive effect of volcanic eruptions on ENSO teleconnections may be attributed to two possible mechanisms: one suggests that the radiative forcing of volcanic aerosols directly modulate tropospheric and lower stratospheric temperature and disrupts atmospheric circulations42,49,63; the other highlights the impacts of volcanic eruptions on oceanic variability in either ENSO region9,18 or other ocean basins23, which further changes atmospheric circulations in mid- and high-latitude regions9,39,64. In the atmosphere, the disruption of ENSO teleconnections may be partly associated with volcanic-induced anomalies in NAO. Previous studies have documented positive NAO phases following large volcanic eruptions, which contribute to Eurasian and North Africa temperature changes that do not stem from ENSO teleconnections65,66. The ENSO teleconnections also influence NAO development in the Atlantic Ocean through stratospheric pathways67,68, and the ENSO-NAO relationship is nonstationary and dependent on the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation69. These complex relationships may be further shifted by volcanic eruptions and initial conditions of ENSO and NAO27,65,70,71. Regardless, the geopotential height composites during Vol years suggest synchronous changes in eastern Pacific and northern Atlantic Oceans (Supplementary Fig. 14). Thus, volcanic eruptions may influence NAO development, which causes climate anomalies in northern mid- to high-latitudes that are decoupled from ENSO teleconnections.

To evaluate the role of oceanic variability in regulating atmospheric circulations, we examine the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) simulations72 in CMIP6 archive that prescribe observed SSTs. In contrast to historical simulations with coupled ocean-atmosphere models, AMIP simulations successfully reproduce the decreased correlations in Vol years compared to NVol years (Supplementary Fig. 20). These results indicate the critical role of oceanic variability in modulating ENSO teleconnections, and underscore the limited representation of oceanic responses to volcanic forcing in current ESMs. Due to the large amount of ocean heat uptake73 and ocean-atmosphere interactions74, oceanic processes may be coupled with atmospheric circulations to disrupt ENSO teleconnections following volcanic eruptions. Thus, future studies may distinguish the relative contribution of direct radiative forcing and changed oceanic variability for individual eruption events to reveal the dynamical mechanisms of volcanic climate effects.

Several non-dynamical factors may lead to uncertainties in our results, including the inconsistency of methods used for reconstructing gridded climate datasets and the sampling of volcanic eruptions. During the early 20th century, climate datasets are interpolated from observations obtained from decreased number of weather stations, which may influence our interpretation of the strength and spatial extent of ENSO teleconnections, despite that we used multiple climate datasets to demonstrate the robustness of our results (Supplementary Figs. 21–25). Additionally, volcanic eruptions selected in this study vary in their latitudes. Our results in Supplementary Fig. 6 show tropical eruptions are mostly followed by negative global \({T}_{a}\) anomalies, which may be attributed to the tropical cooling caused by the backscattering of shortwave radiation21,50. Tropical eruptions also induce positive NAO phases that modulate mid- to high-latitude temperature, which is decoupled from the ENSO anomalies caused by volcanic eruptions65,70. The southern extratropical eruptions are mostly followed by negative Niño 3.4 anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 6). The La Niña-like conditions are consistent with the analyses of ENSO reconstructions over the past millennium28. The varying latitudes of volcanic eruptions may lead to differential outcomes in terms of radiative forcing27,75,76 and ENSO development27,28, which change the magnitude and duration of disrupted ENSO teleconnections. Future studies are suggested to investigate the latitudes of volcanic eruptions and initial conditions of climate states in simulations and millennial reconstructions to fully reveal the underlying mechanisms.

Under anthropogenic warming, both climate observations and model simulations indicate inevitable changes in ENSO amplitude, frequency, and the location of largest SST anomalies7,77. In our work, we analyzed the influence of ENSO dynamics on its teleconnections by regressing global \({T}_{a}\) onto Niño 3.4 in 31-year moving windows. Although the results demonstrate high stability in ENSO teleconnections during the observational period (Supplementary Fig. 10), our analysis based upon Niño 3.4 index alone may be incomprehensive in light of the variations in ENSO types and strength78,79,80, particularly when changes in ENSO dynamics are coincident with volcanic eruptions. Extending analyses to more eruptions in a longer period will consolidate our conclusions and pinpoint dynamical processes that are critical for the disrupted ENSO teleconnections.

Methods

Climate data

Monthly global land surface air temperature (\({T}_{a}\)) data during the 1901-2022 period are collected from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) gridded Time Series 4.07 (ref. 81), Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) Surface Temperature Analysis (refs. 82,83), and Berkeley Earth Surface Temperatures (BEST; ref. 84) datasets. All \({T}_{a}\) datasets are resampled to a 0.5-degree resolution using a bilinear algorithm, and Antarctica is excluded from our analysis due to data scarcity. Global SST data are collected from the Hadley Centre Global Sea Ice and SST (HadISST, ref. 85), Centennial in situ Observation-Based Estimates (COBE, refs. 86,87) SST, and NOAA extended reconstruction SSTs version 5 (ERSSTv5, ref. 88) datasets. To ensure the robustness of our findings, the ensemble means of these \({T}_{a}\) and SST datasets are used in the study. Each individual dataset is also examined, which provides nearly identical results (Supplementary Figs. 21–25). To diagnose atmospheric circulation anomalies after volcanic eruptions, global geopotential height data during 1948–2022 are collected from the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis 1 project89.

We calculate Niño 3.4 index as averaged SST anomalies over the 5°S-5°N and 170-120°W region. The El Niño (La Niña) events are identified when DJF Niño 3.4 is greater (less) than 0.5 standard deviation after high-pass filters21. To account for tropical cooling arising from volcanic eruptions, we calculate the relative Niño 3.4 index as the difference between original Niño 3.4 and the tropical (20°S-20°N) mean SST anomalies, with its variance adjusted to the same as original Niño 3.4 (refs. 47,48). As shown, the original and relative Niño 3.4 indices are highly consistent and provide very similar results regarding the disruption of ENSO teleconnections during Vol years (Supplementary Fig. 7).

High-pass filter

To highlight ENSO-induced variability and meanwhile account for the time frame of volcanic eruptions on ENSO and its teleconnections9,32,34,42, we apply a 15-year Butterworth high-pass filter to global \({T}_{a}\) as well as DJF Niño 3.4 series. Here, we conduct an experiment to show the influence of high-pass filters at different frequencies on temperature variations. We assume a global warming trend with a slope of 0.1\(^\circ {{{\rm{C}}}}\) per decade, multidecadal oceanic oscillations with periods of 25 and 40 years, ENSO variability with 5-year and 11-year periods, and 3-year volcanic-induced climate effects (Supplementary Fig. 1). The multidecadal oscillation components represent the influences of large-scale oceanic oscillations such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, which commonly have periods ranging from 20 to 80 years as shown in paleo-reconstructions90,91. The ENSO mainly consists of interannual (2–7 years) and decadal (8–13 years) variabilities that are evident in millennial reconstructions9. The sum of these individual components is interpretated as the pseudo-observations and subject to Butterworth high-pass filters at 5, 9, 15, 31, and 51 years. The results show that the 15-year Butterworth high-pass filter best preserves the ENSO variability and volcanic climate effects (Supplementary Fig. 2), and is thus applied in this study. By contrast, the 5- and 9-year high-pass filters underestimate the magnitude of ENSO variability, whereas 31- and 51-year high-pass filters do not fully remove the multidecadal oscillations. Despite the distortions, the disruption of ENSO teleconnections remains evident using Butterworth high-pass filters at 9 and 31 years and a cubic smoothing spline (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Volcanic data and years impacted by volcanic eruptions

Timing and magnitude of volcanic eruptions are collected from the Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution40 (Supplementary Table 1). We select 14 volcanic eruptions with VEI41 of 5 or higher during the 1901–2022 period. The period from 1901 to 2022 is distinguished into the years when ENSO teleconnections are impacted (Vol) and not impacted (NVol) by volcanic eruptions. If an eruption starts from January to August, ENSO teleconnections with boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) in the current and following two years are assumed to be affected and are identified as Vol years. If an eruption starts after August, \({T}_{a}\) in the boreal summer of current year is not impacted by this volcanic eruption, and the following 3 years are identified as Vol years. All remaining years are identified as NVol years. The number of NVol and Vol years are 88 and 34 during the 1901-2022 period, respectively.

Other selection criteria of Vol years are applied to show the robustness of our conclusions. A sensitivity test of selecting tropical eruptions with VEI \(\ge\) 4 shows decreased correlations in Vol years compared to NVol years (Supplementary Table 2). We examine Vol years as 2 and 4 years following volcanic eruptions and find similar decreases in the ENSO-temperature correlations from NVol to Vol years (Supplementary Table 2). A reconstruction of stratospheric aerosol optical depth (SAOD44) from ice core measurements is used to identify Vol years as those with global mean SAOD larger than 0.01. A total of 20 Vol years is identified from SAOD, and the results validate the decoupling between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) after eruptions (Supplementary Fig. 4). We also select volcanic eruptions with volcanic stratospheric sulfur injections (VSSI) greater than 0.92 Tg S from an ice-core reconstruction45 and satellite observations46. The results similarly support the disruption of ENSO teleconnections (Supplementary Fig. 5). Despite these rigorous validations, the small size of volcanic eruptions calls for caution in strict statistical interpretation of these correlation results, and future investigations may devise new metrics to fully evaluate the impacts of volcanic eruptions on ENSO teleconnections.

Correlation analysis and sensitivity test

The relationship between global \({T}_{a}\) and DJF Niño 3.4 is evaluated from the Pearson correlation coefficients during NVol and Vol years. We calculate the p value in correlation analysis using Student’s t-distribution. In addition, bootstrap analysis is applied to quantify the uncertainties in correlations during NVol years (Fig. 1d). We resample the observations during NVol years with the size of 34, which is the same number as Vol years. The correlation coefficient from this resample is viewed as one realization. This process is repeated 1000 times, generating 1000 correlation coefficients for the NVol years. The observed correlation between ENSO and global \({T}_{a}\) during Vol years is lower than the 1% quantile of the correlations resampled from NVol years, indicating the disruption of ENSO teleconnections does not occur by chance.

Gridded correlation analysis is conducted to show the spatial pattern of changed correlations from NVol and Vol years. The gridded correlations between ENSO and boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) are calculated for NVol and Vol years, respectively, and are classified into three categories, including significant positive (P), non-significant (NS), and significant negative (N) correlations. The shifted correlations from NVol to Vol years are separated by “_”, resulting in a total of 9 types (see legend in Fig. 2c). For example, the “P_NS” indicates a shift from a significant positive correlation during NVol years to a non-significant correlation during Vol years. Regions where temperature is connected to ENSO are represented by significant correlations during NVol years (P_P, P_NS, P_N, N_P, N_NS, and N_N), accounting for 44.74% of global areas. Regions where temperature is disrupted by volcanic eruptions are represented by changed correlations (P_NS, P_N, N_P, and N_NS), accounting for 27.86% of global areas. Thus, around 62.27% (27.86%/44.74%) of areas where temperature is significantly connected to ENSO during NVol years is disrupted by volcanic eruptions. We also adjust the degree of freedom during Vol years to the same as NVol years (DF = 86) during the significance test and achieve similar results (Supplementary Fig. 26).

To measure the sensitivity of boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) to ENSO, we establish a linear regression model between DJF Niño 3.4 and boreal summer \({T}_{a}\). The regression coefficient is used as the sensitivity of boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) to ENSO, which measures the change in boreal summer \({T}_{a}\) when DJF Niño 3.4 increases by one degree Celsius92 (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12).

CMIP6 simulations

Apart from the observations, we evaluate the historical simulations of the sixth phase of CMIP672. A total of 25 models with all forcings are collected (Supplementary Table 3). We adopt one ensemble member for each model and select their overlapping period with observations (1901–2014). Niño 3.4 is calculated as mean surface temperature anomaly over the 5S-5N and 170–120 W region. Other procedures, including high-pass filter and definition of ENSO phases, are the same as for observations. The CMIP6 experiments incorporate the volcanic forcings by prescribing the stratospheric aerosols72. Thus, we use global mean SAOD to identify Vol years in historical simulations. The SAOD is calculated from the CMIP6 stratospheric aerosol forcing reconstruction52,53. We compare the SAOD in CMIP6 experiments with that from ice cores, and find they are highly consistent after adjusting for background sulfur injection (Supplementary Fig. 27). The Vol years in historical simulations are identified using the criterion of SAOD > 0.01. To consider tropical cooling following volcanic eruptions, relative Niño 3.4 is examined and produces similar results (Supplementary Fig. 28). The AMIP simulations during 1979–2014 are also analyzed to explore the reasons for model errors (Supplementary Fig. 20). Unlike historical simulations with coupled ocean-atmosphere models, the AMIP simulations prescribe observed SSTs. Thus, a comparison of AMIP with historical simulations help evaluate the role of oceanic variability in influencing ENSO teleconnections72.

ENSO reconstruction

We reconstruct DJF Niño 3.4 using observed \({T}_{a}\) in the boreal summer as predictors to emulate previous reconstructions8,9. Global, Northern Hemispheric (NH), Southern Hemispheric (SH), and tropical \({T}_{a}\) are selected as predictors to explore the sensitivity to proxy locations. The principal components of \({T}_{a}\) are extracted by empirical orthogonal function analysis. Five principal components showing the highest correlations with ENSO, in either current or preceding years, are selected as predictors. A linear regression models is established between DJF Niño 3.4 and principal components. To avoid the overfitting and reflect reconstruction skills, we apply a moving-block 13-fold cross-validation, in which the 1901–2022 period is split into 13 folds. The first fold is withheld for validation, and a linear regression model that is calibrated over the remaining 12 folds is used for reconstruction. This process is repeated for all 13 folds, resulting in a reconstruction during the 1901–2022 period. The performance is evaluated during NVol and Vol years, respectively. To validate our conclusions and consider the non-linearity, we establish a random forest model93 and achieve similar results (Supplementary Fig. 17). Relative Niño 3.4 is also reconstructed from \({T}_{a}\), which produces highly identical results (Supplementary Fig. 29).

Data availability

Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series 4.07 is collected at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/cru_ts_4.07. Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature Analysis dataset is collected at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp. The Berkeley Earth Surface Temperatures dataset is collected at https://berkeleyearth.org/data. The Hadley Centre Global Sea Ice and SST dataset is collected at https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst. The Centennial in situ Observation-Based Estimates SST dataset is collected at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cobe2.html. The NOAA extended reconstruction SSTs version 5 dataset is collected at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html. The NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis 1 product is collected at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis.html. Volcanic eruption events are collected from the Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution at https://volcano.si.edu. The CMIP6 simulation data are collected at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6, and aerosols forcing datasets are collected at ftp://iacftp.ethz.ch/pub_read/luo/CMIP6_SAD_radForcing_v4.0.0_1850-2018. Source data are available at https://github.com/XuZhang-XZ/Volcanic-eruptions-disrupt-ENSO-teleconnections-with-land-summer-temperature.

Code availability

Code to generate all figures are available at https://github.com/XuZhang-XZ/Volcanic-eruptions-disrupt-ENSO-teleconnections-with-land-summer-temperature.

References

Cai, W. et al. Climate impacts of the El Niño–southern oscillation on South America. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 215–231 (2020).

Vashisht, A., Zaitchik, B. & Gnanadesikan, A. ENSO teleconnection to eastern African summer rainfall in global climate models: Role of the tropical easterly jet. J. Clim. 34, 293–312 (2021).

Phillips, T., Nerem, R. S., Fox-Kemper, B., Famiglietti, J. S. & Rajagopalan, B. The influence of ENSO on global terrestrial water storage using GRACE. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L16705 (2012).

Wen, N., Liu, Z. & Li, L. Direct ENSO impact on East Asian summer precipitation in the developing summer. Clim. Dyn. 52, 6799–6815 (2018).

Timmermann, A. et al. El Niño–southern oscillation complexity. Nature 559, 535–545 (2018).

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an integrating concept in Earth science. Science 314, 1740–1745 (2006).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Wilson, R. et al. Reconstructing ENSO: the influence of method, proxy data, climate forcing and teleconnections. J. Quat. Sci. 25, 62–78 (2010).

Li, J. et al. El Niño modulations over the past seven centuries. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 822–826 (2013).

Cook, E. R. et al. Asian monsoon failure and megadrought during the last millennium. Science 328, 486–489 (2010).

Li, J., Xie, S.-P. & Cook, E. R. El Niño phases embedded in Asian and North American drought reconstructions. Quat. Sci. Rev. 85, 20–34 (2014).

Li, X., Hu, Z.-Z., Ding, R. & Liu, Y. Which ENSO index best represents its global influences?. Clim. Dyn. 61, 4899–4913 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Dannenberg, M. P., Hwang, T. & Song, C. El Niño-Southern Oscillation-induced variability of terrestrial gross primary production during the satellite era. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 124, 2419–2431 (2019).

Kovats, R. S., Bouma, M. J., Hajat, S., Worrall, E. & Haines, A. El Niño and health. Lancet 362, 1481–1489 (2003).

Yeh, S. W. et al. ENSO atmospheric teleconnections and their response to greenhouse gas forcing. Rev. Geophys. 56, 185–206 (2018).

Taschetto, A. S. et al. in El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate (eds Michael J. M., Agus S., & Wenju C.) 309–335 (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

Zhu, F. et al. A re-appraisal of the ENSO response to volcanism with paleoclimate data assimilation. Nat. Commun. 13, 747 (2022).

Pausata, F. S. R., Zhao, Y., Zanchettin, D., Caballero, R. & Battisti, D. S. Revisiting the mechanisms of ENSO response to tropical volcanic eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102183 (2023).

Brad Adams, J., Mann, M. E. & Ammann, C. M. Proxy evidence for an El Niño-like response to volcanic forcing. Nature 426, 274–278 (2003).

Dee Sylvia, G. et al. No consistent ENSO response to volcanic forcing over the last millennium. Science 367, 1477–1481 (2020).

Khodri, M. et al. Tropical explosive volcanic eruptions can trigger El Niño by cooling tropical Africa. Nat. Commun. 8, 778 (2017).

Stevenson, S., Otto-Bliesner, B., Fasullo, J. & Brady, E. “El Niño Like” hydroclimate responses to last millennium volcanic eruptions. J. Clim. 29, 2907–2921 (2016).

Ding, Y. et al. Ocean response to volcanic eruptions in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 5622–5637 (2014).

Zanchettin, D. et al. Effects of forcing differences and initial conditions on inter-model agreement in the VolMIP volc-pinatubo-full experiment. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 2265–2292 (2022).

McGregor, S. & Timmermann, A. The effect of explosive tropical volcanism on ENSO. J. Clim. 24, 2178–2191 (2011).

Predybaylo, E., Stenchikov, G., Wittenberg, A. T. & Osipov, S. El Niño/Southern Oscillation response to low-latitude volcanic eruptions depends on ocean pre-conditions and eruption timing. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 12 (2020).

Pausata, F. S. R., Zanchettin, D., Karamperidou, C., Caballero, R. & Battisti David, S. ITCZ shift and extratropical teleconnections drive ENSO response to volcanic eruptions. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz5006 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. Divergent El Niño responses to volcanic eruptions at different latitudes over the past millennium. Clim. Dyn. 50, 3799–3812 (2018).

Liu, F. et al. Relative roles of land and ocean cooling in triggering an El Niño following tropical volcanic eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100609 (2022).

Robock, A., Marquardt, A., Kravitz, B. & Stenchikov, G. Benefits, risks, and costs of stratospheric geoengineering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2009).

PAGES2k, C. Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era. Nat. Geosci. 12, 643–649 (2019).

Sigl, M. et al. Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523, 543–549 (2015).

Paik, S. et al. Impact of volcanic eruptions on extratropical atmospheric circulations: review, revisit and future directions. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 063003 (2023).

Meyer, A., Folini, D., Lohmann, U. & Peter, T. Tropical temperature and precipitation responses to large volcanic eruptions: observations and AMIP5 simulations. J. Clim. 29, 1325–1338 (2016).

Almazroui, M., Rashid, I. U., Saeed, S. & Islam, M. N. ENSO influence on summer temperature over Arabian Peninsula: role of mid-latitude circulation. Clim. Dyn. 53, 5047–5062 (2019).

Sun, C., Li, J. & Ding, R. Strengthening relationship between ENSO and western Russian summer surface temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 843–851 (2016).

Jong, B.-T., Ting, M., Seager, R. & Anderson, W. B. ENSO teleconnections and impacts on US summertime temperature during a multiyear La Niña life cycle. J. Clim. 33, 6009–6024 (2020).

Wu, R. et al. Changes in the relationship between Northeast China summer temperature and ENSO. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, D21107 (2010).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Indo-western Pacific Ocean capacitor and coherent climate anomalies in post-ENSO summer: a review. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 33, 411–432 (2016).

Global Volcanism Program, Volcanoes of the World (V5.2.4). https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW5-2024.5.2 (2024).

Newhall, C. G. & Self, S. The volcanic explosivity index (VEI) an estimate of explosive magnitude for historical volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 87, 1231–1238 (1982).

McCormick, M. P., Thomason, L. W. & Trepte, C. R. Atmospheric effects of the Mt Pinatubo eruption. Nature 373, 399–404 (1995).

Esper, J., Torbenson, M. & Buntgen, U. 2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years. Nature 631, 94–97 (2024).

Crowley, T. J. & Unterman, M. B. Technical details concerning development of a 1200 yr proxy index for global volcanism. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 5, 187–197 (2013).

Gao, C., Robock, A. & Ammann, C. Volcanic forcing of climate over the past 1500 years: An improved ice core-based index for climate models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D23111 (2008).

Carn, S. Multi-Satellite Volcanic Sulfur Dioxide L4 Long-Term Global Database V4. https://doi.org/10.5067/MEASURES/SO2/DATA405 (2025).

Van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Defining El Niño indices in a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 044003 (2021).

L’Heureux, M. L. et al. A relative sea surface temperature index for classifying ENSO events in a changing climate. J. Clim. 37, 1197–1211 (2024).

Stenchikov, G. et al. Arctic Oscillation response to the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption: effects of volcanic aerosols and ozone depletion. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 107, 4803 (2002).

Smith, D. et al. Mitigation needed to avoid unprecedented multi-decadal North Atlantic Oscillation magnitude. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 403–410 (2025).

Ogi, M., Tachibana, Y. & Yamazaki, K. Impact of the wintertime North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) on the summertime atmospheric circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1704 (2003).

Thomason, L. W. et al. A global space-based stratospheric aerosol climatology: 1979–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 469–492 (2018).

Luo, B. Stratospheric aerosol data for use in CMIP6 models. ftp://iacftp.ethz.ch/pub_read/luo/CMIP6_SAD_radForcing_v4.0.0_1850-2018 (2020).

Zanchettin, D. et al. The Model Intercomparison Project on the climatic response to Volcanic forcing (VolMIP): experimental design and forcing input data for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2701–2719 (2016).

Plazzotta, M., Séférian, R., Douville, H., Kravitz, B. & Tjiputra, J. Land Surface cooling induced by sulfate geoengineering constrained by major volcanic eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 5663–5671 (2018).

Kravitz, B. et al. The geoengineering model intercomparison project phase 6 (GeoMIP6): Simulation design and preliminary results. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 3379–3392 (2015).

Keeble, J. et al. Evaluating stratospheric ozone and water vapour changes in CMIP6 models from 1850 to 2100. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 5015–5061 (2021).

Hao, Z., Hao, F., Singh, V. P. & Zhang, X. Quantifying the relationship between compound dry and hot events and El Niño–southern Oscillation (ENSO) at the global scale. J. Hydrol. 567, 332–338 (2018).

Humphrey, V. et al. Sensitivity of atmospheric CO2 growth rate to observed changes in terrestrial water storage. Nature 560, 628–631 (2018).

Steiger, N. J., Smerdon, J. E., Cook, E. R. & Cook, B. I. A reconstruction of global hydroclimate and dynamical variables over the Common Era. Sci. Data 5, 180086 (2018).

Perkins, W. & Hakim, G. Coupled atmosphere–ocean reconstruction of the last millennium using online data assimilation. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA003959 (2021).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Zambri, B., LeGrande, A. N., Robock, A. & Slawinska, J. Northern Hemisphere winter warming and summer monsoon reduction after volcanic eruptions over the last millennium. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 7971–7989 (2017).

Gushchina, D., Kolennikova, M., Dewitte, B. & Yeh, S.-W. On the relationship between ENSO diversity and the ENSO atmospheric teleconnection to high-latitudes. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 1303–1325 (2022).

Dogar, M. M., Fujiwara, M., Zhao, M., Ohba, M. & Kosaka, Y. ENSO and NAO linkage to strong volcanism and associated post-volcanic high-latitude winter warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106114 (2024).

Dogar, M. M., Fujiwara, M., Ohba, M. & Almazroui, M. Investigating post-eruption amplified winter cooling in the Middle East and North Africa—unraveling ENSO and NAO dynamics. Environ. Res. Commun. 7, 045012 (2025).

Dogar, M. M. et al. A review of El Niño Southern Oscillation linkage to strong volcanic eruptions and post-volcanic winter warming. Earth Syst. Environ. 7, 15–42 (2023).

Ineson, S. & Scaife, A. The role of the stratosphere in the European climate response to El Niño. Nat. Geosci. 2, 32–36 (2009).

Zhang, W., Mei, X., Geng, X., Turner, A. G. & Jin, F.-F. A nonstationary ENSO–NAO relationship due to AMO modulation. J. Clim. 32, 33–43 (2019).

Zhu, X., Ji, Z., Liu, F., Dong, W. & Gao, C. Extreme Tibetan Plateau cooling caused by tropical volcanism. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 122 (2024).

Weierbach, H., LeGrande, A. N. & Tsigaridis, K. The impact of ENSO and NAO initial conditions and anomalies on the modeled response to Pinatubo-sized volcanic forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 15491–15505 (2023).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Huguenin, M. F., Holmes, R. M. & England, M. H. Drivers and distribution of global ocean heat uptake over the last half century. Nat. Commun. 13, 4921 (2022).

Peng, Q., Xie, S.-P., Wang, D., Zheng, X.-T. & Zhang, H. Coupled ocean-atmosphere dynamics of the 2017 extreme coastal El Niño. Nat. Commun. 10, 298 (2019).

Timmreck, C. et al. Linearity of the climate response to increasingly strong tropical volcanic eruptions in a large ensemble framework. J. Clim. 37, 2455–2470 (2024).

Pausata, F. S. R., Chafik, L., Caballero, R. & Battisti, D. S. Impacts of high-latitude volcanic eruptions on ENSO and AMOC. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13784 (2015).

Freund, M. B. et al. Higher frequency of Central Pacific El Niño events in recent decades relative to past centuries. Nat. Geosci. 12, 450–455 (2019).

Tang, S. et al. Recent changes in ENSO’s impacts on the summertime circumglobal teleconnection and mid-latitude extremes. Nat. Commun. 16, 646 (2025).

Liu, L. et al. Increasingly negative tropical water–interannual CO2 growth rate coupling. Nature 618, 755–760 (2023).

Hu, K., Huang, G., Huang, P., Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Intensification of El Niño-induced atmospheric anomalies under greenhouse warming. Nat. Geosci. 14, 377–382 (2021).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

Lenssen, N. et al. A NASA GISTEMPv4 observational uncertainty ensemble. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD040179 (2024).

GISTEMP, T. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP v4). https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp (2025).

Rohde, R. A. & Hausfather, Z. The Berkeley Earth land/ocean temperature record. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3469–3479 (2020).

Rayner, N. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

Hirahara, S., Ishii, M. & Fukuda, Y. Centennial-scale sea surface temperature analysis and its uncertainty. J. Clim. 27, 57–75 (2014).

Ishii, M., Shouji, A., Sugimoto, S. & Matsumoto, T. Objective analyses of sea-surface temperature and marine meteorological variables for the 20th century using ICOADS and the Kobe collection. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 865–879 (2005).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–472 (1996).

Gedalof, Z. E., Mantua, N. J. & Peterson, D. L. A multi-century perspective of variability in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation: new insights from tree rings and coral. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 57-1–57-4 (2002).

Kilbourne, K. H., Alexander, M. A. & Nye, J. A. A low latitude paleoclimate perspective on Atlantic multidecadal variability. J. Mar. Syst. 133, 4–13 (2014).

Zhou, S. et al. Soil moisture–atmosphere feedbacks mitigate declining water availability in drylands. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 38–44 (2021).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0605601 to J.L. and 2023YFF0804700 to F.S.), the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (17317722 to J.L.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52279024 and 52261145744 to Q.D.). We acknowledge the organizations that provide data used in our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. and J.L. conceived and designed the research. X.Z. performed the data analysis. X.Z. and J.L. wrote and revised the manuscript. S.P.X., F.L., F.S., C.G., H.Z., and Q.D. provided comments for the interpretation of results and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Li, J., Xie, SP. et al. Volcanic eruptions disrupt ENSO teleconnections with land summer temperature. Nat Commun 16, 9882 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64879-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64879-w