Abstract

We present a potentially eco-friendly, cost-efficient strategy for synthesizing high-purity Li2S, a key precursor for sulfide-based solid electrolytes. While these electrolytes surpass conventional organic counterparts in both safety and performance, their widespread application is hindered by the high cost of Li2S. Here, a solvent-free metathesis route is developed, in which thiourea serves as an S2⁻ donor to sulfurize LiOH, enabling scalable Li2S production (∼100 g per batch) with significantly reduced projected costs. During the process, intermediates (H2NCN, H2O) are transformed into benign gases (CO2, NH3) that spontaneously leave the system, thereby driving Li2S formation without ΔGmix limitations. The as-synthesized Li2S is successfully applied to prepare sulfide-based solid electrolytes such as Li10GeP2S12 and argyrodite-Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5, achieving laboratory-scale (1 kg) production costs reduction of up to 27.5% and 92.9%, respectively. Furthermore, all-solid-state batteries employing Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 demonstrate electrochemical performance comparable to those fabricate with commercial Li2S. This scalable methodology thus may provide a proming pathway to bridge low-cost Li2S synthesis with the practical deployment of sulfide-based solid electrolytes, which may accelerate the commercialization of high-performance all-solid-state batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pursuit of next-generation electrochemical energy-storage systems centers on exploring efficient and scalable solid-state electrolytes (SSEs), which represent attractive replacements for traditional organic liquid electrolytes. The SSEs can not only avoid the safety and environmental issues caused by the effumability, easy leakage and combustibility of organic liquid electrolytes, but also be able to serve as functional separators with high ionic conductivity and robust mechanical integrity between the positive electrode and the negative electrode, promoting the energy density and security of the energy storage system. Among all the reported SSEs, sulfide-type compounds have gained widespread attention because the remarkable Li10GeP2S12 (LGPS) and argyrodite-type Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 (LPSC1.5) possess extremely high ionic conductivity, which is close to or even surpass that of commercial organic liquid electrolytes (10–2 S/cm) at room temperature1,2,3. In addition, sulfide electrolytes have the advantages of excellent mechanical deformability and interfacial compatibility, favoring compact contact with the interface of electrode materials4,5. Sulfide-based SSEs are indispensable for next-generation lithium-ion batteries due to their unparalleled combination of ultrahigh ionic conductivity, superior interfacial properties and mechanical flexibility, which are critical for achieving high-energy-density and safe all-solid-state batteries. Their unique ability to form intimate interfaces with electrode materials and their compatibility with high-voltage positive electrodes position them as one of the most promising options for realizing the full potential of all-solid-state batteries (ASSBs). Therefore, sulfide-type SEEs are preferable electrolyte materials for ASSBs. However, the high cost of Li2S raw material (732 USD/kg)6 severely hinders the practical application of sulfide SSEs for energy-storage devices.

In recent years, a growing number of research studies on the synthesis of Li2S materials have been widely investigated for the industrialization of sulfide SSEs7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. All the synthesis reactions (summarized in Supplementary Table 1) could be mainly separated into two categories, including redox reaction and metathesis reaction. In a solid-phase redox reaction, the Li2S can be obtained directly through the reaction between Li2SO4 and solid reductants (such as carbon, Mg, or Al) at high temperatures7,8,9,10. Nevertheless, excess reductants are needed for the total reduction of Li2SO4 to Li2S. Hence, the purity of the Li2S products is extremely low. Great efforts were made to promote the purity of Li2S products, such as using strong reductive-type organolithium salts to react with S powders or H2S gas in liquid-phase11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, or employing reductive H2 gas to react with Li2SO419. Although the raw materials of S or Li2SO4 powders are stable and inexpensive, the organolithium salts and H2 are costly and explosive, hence this strategy is incompetent for practical application24.

Recently, a new approach was proposed for making Li2S through liquid-phase metathesis reaction between LiY (Y = Cl–, Br–, I– or NO3–) and anhydrous Na2S in organic solvent20,21,22,23. The metathesis reaction, also known as the double replacement or double decomposition reaction, are commonly occurred in the liquid phase, which could be driven to completion by the formation of a gas or precipitate product25,26,27. Typically, LiCl and anhydrous Na2S are selected as raw materials for the synthesis of Li2S in the ethanol phase. This reversible reaction is thermodynamically spontaneous (\({\triangle G}_{r,m}^{\theta } < 0\)) with large equilibrium constants (K) due to the low solubility of the NaCl byproducts in the ethanol phase22. The generated NaCl precipitate can quickly separate from the reaction system and serve as the driving force to shift the chemical equilibrium to the right side, i.e., toward more Li2S products. The inexpensive raw materials and the convenient reaction conditions make this metathesis reaction potential for industrial production20,21,22. However, the chemical equilibrium toward the Li2S forming direction can not reach completion since the NaCl byproduct can not entirely precipitate (the solubility of NaCl in ethanol is 0.055 wt.%)28, resulting in the impurity of unreacted LiCl and dissolved NaCl. Adding excess reactant (LiCl or Na2S) favored further shifting of the chemical equilibrium toward the Li2S forming direction, decreasing the content of the NaCl impurity in the ethanol phase. However, the excess reactant (LiCl or Na2S) still affects the purity of Li2S products, which even converted to new impurities such as LiOCl or NaHS through oxidation or alcoholysis process20,22. Until now, no effective methods have been proposed to completely convert the reactants into Li2S product without impurity in the liquid-phase metathesis reaction.

According to Thermodynamics theory, the dissolved NaCl byproduct in the ethanol phase would be mixed with the unreacted LiCl and Na2S reactants, generating the Gibbs Free Energy of Mixing (ΔGmix). The ΔGmix would lead to a minimum in the Gibbs free energy before the reaction progress achieved 100%, which means the chemical reaction has reached equilibrium before the reactants are completely converted to products29,30. We believe this is the main reason why the reactants can not totally convert to Li2S product in the liquid-phase metathesis reaction. According to the Le Chatelier’s principle, the change in the products’ concentration directly affects the chemical equilibrium shift. Decreasing the concentration of the byproduct can shift the chemical equilibrium to the forward direction for the formation of more main-product31. During the metathesis reaction process, if the whole byproduct could be automatically separated from the reaction system, then no ΔGmix would be generated during the reaction, and the absence of the byproduct can impel the chemical equilibrium to thoroughly tend to the forward direction, leading to a complete conversion to the main-product32. Nevertheless, in a liquid-phase metathesis reaction system, most of the gaseous and precipitate byproducts can not be fully separated from the liquid phase due to their non-zero solubility in the liquid phase, resulting in the generation of ΔGmix. For the complete conversion of reactants to the Li2S main product, a solvent-free system with the production of gaseous byproducts is indispensable for the metathesis reaction since no mixing would occur between gas and solid33.

Thiourea ((NH2)2C = S) is an environmentally friendly, inexpensive and air-stable solid reagent34, capable of providing S2– ions via metathesis reactions. Moreover, the thermolysis of thiourea generates gaseous products35, which can be readily removed from the reaction system, simultaneous driving the chemical equilibrium of the metathesis reaction towards complete conversion. To achieve high-purity Li2S with low-cost on a large scale, we rationally designed a solvent-free metathesis route using thiourea as S2–-donors and LiOH as the lithium source. According to online thermogravimetry/differential thermal analysis coupled with fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (TG/DTA-FTIR), online thermogravimetry/differential thermal analysis coupled with mass spectrometry (TG/DTA-MS), and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, intermediate byproducts such as H2NCN and H2O were removed via hydrothermolysis, while only gaseous byproducts (CO2 and NH3) were generated during the metathesis reaction. The gaseous byproducts could be automatically separated from the Li2S main product without affecting the Gibbs free energy (ΔGmix ≈ 0), effectively shifting the chemical equilibrium fully towards reaction and enabling complete conversion to Li2S. This straightforward solvent-free metathesis reaction is practicable for the large-scale production of high-purity Li2S (up to ~100 g per batch) without requiring additional purification. Furthermore, conventional solid sulfide electrolytes, including Li10GeP2S12 (LGPS) and argyrodite Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 (LPSC1.5), were successfully synthesized on a large scale using the as-obtained Li2S as a precursor, reducing projected materials cost by up to 27.5% and 92.9%, respectively. Notably, all-solid-state batteries assembled with Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 derived from the synthezied Li2S exhibited electrochemical performance comparable to those prepared by commercialized Li2S. Overall, this solvent-free metathesis stratage thus potentially provides a green and scalable route for mass production of high-purity Li2S, which have the potential to substantially lowering the cost of sulfide-based solid electrolytes and facilitating the practical deployment of all-solid-state batteries.

Results

Reaction design and molecular interaction analysis

Thiourea ((NH2)2CS) was selected as solid S2– donors to sulfurize LiOH to form Li2S solid product with the emission of gaseous CO2 and NH3 byproducts. This designed solvent-free metathesis reaction could be described as Eq. (1):

In typical liquid-phase metathesis reaction20,21,22,23, the slightly dissolved NaCl byproduct would mix with the Li2S main-product in the solvent phase, resulting in the formation of ΔGmix. In contrast, no ΔGmix was generated in this solvent-free metathesis reaction since no mixing would occur between solid (Li2S main-product) and gas (CO2 & NH3 byproducts) (Fig. 1a)33. The ΔGmix would lead to a minimum in the Gibbs free energy before the reaction progress achieved 100% (ξ < 1), indicating that the chemical reaction has reached equilibrium before the reactants are completely converted to products. However, without ΔGmix, reactants would simply slide down the ∆G slope to products with the minimum at ξ = 1, leading to a complete conversion to the main-product (Fig. 1b)29,30.

a Comparison between liquid-phase metathesis and solvent-free metathesis reaction. b Impact of ΔGmix on reaction progress. c Electron density surface mapped with molecular electrostatic potential. d HOMO and LUMO of thiourea and LiOH moleculars. e ΔG of the metathesis reactions by DFT calculation. f Illustration of the solvent-free metathesis reaction.

To analyze and investigate the feasibility of the solvent-free metathesis reaction (Eq. (1)), Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) has been used for interpreting and predicting the sites of favorable interactions in these chemical reactions36,37,38. Fig. 1c exhibited the calculated MEP of the (NH2)2CS and LiOH molecules. The blue area (electron-poor) localized over the S site in (NH2)2CS was related to the nucleophilic region, which tended to interact with the red area (electron-rich) localized over the Li site (electrophilic region) in LiOH.

Besides, Frontier Molecular Orbital theory was employed to investigate the molecular reactivity by calculating the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of (NH2)2CS and LiOH moleculars39,40,41,42. The difference of energy between HOMO and LUMO is called as energy gap (Egap = ELUMO – EHOMO), which is an important parameter to evaluate the molecular chemical reactivity. Usually, a molecule with low Egap is generally associated with high chemical activity29. According to DFT calculation results (Fig. 1d), the Egap values of (NH2)2CS and LiOH were, respectively, as low as 0.38 eV and 0.24 eV, indicating the high chemical activity between the reaction of (NH2)2CS and LiOH moleculars.

Thermodynamic feasibility, reaction mechanism and product verification

Subsequently, the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of this designed metathesis reaction (Fig. 1e) was calculated through the DFT method. The ΔG was less than 0 (\({\triangle G}_{r,m}^{\theta } < 0\)) and continuously decreased with the increase of the reaction temperature, indicating the thermodynamical spontaneity of Eq. (1) over 500 °C. Meanwhile, the product of this metathesis reaction was investigated via the Raman test, and a Raman signal of Li2S (375 cm–1) can be observed above 400 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1), corresponding to the calculated result in Fig. 1e.

To investigate the chemical reaction mechanism of Eq. (1), reasonable chemical stages for this solvent-free metathesis reaction were calculated and proposed. Specifically, the Eq. (1) could be fundamentally divided into the following three stages (Fig. 1f):

a. The thiourea produced gaseous species of CS2, NH3 and H2NCN via thermolysis (Eq. (2)); b. The gaseous CS2 from Eq. (2) sulfurize LiOH through metathesis reaction, producing Li2S main-product with the emission of CO2 and H2O byproducts (Eq. (3)); c. The byproducts of H2NCN from Eq. (2) and H2O from Eq. (3) were depleted through hydrothermolysis reaction, producing gaseous byproducts of CO2 and NH3 (Eq. (4)).

To verify the chemical reaction mechanism of this solvent-free metathesis reaction, online coupled TG/DTA-FTIR were used to analyze the thermolysis products of thiourea in Eq. 2 (Fig. 2a). Three major gaseous species were generated during the metathesis reaction, including carbon disulfide (CS2) with absorption peaks at 1541 cm–1, cyanamide (H2NCN) with absorption peaks at 2266 cm–1 and ammonia (NH3) with absorption peaks at 966 cm–1 35, proving the reaction products in Eq. (2). Besides, the thermolysis products of thiourea were detected through the online coupled TG/DTA-MS test (Fig. 2b). Along with the increasing temperature, the characteristic fragments of gaseous species CS2 (m/z = 76), NH3 (m/z = 17) and H2NCN (m/z = 42) have been confirmed, corresponding to the results in Fig. 2a.

a Online coupled TG/DTA-FTIR spectra of the thermolysis of thiourea under an Ar atmosphere. b Online coupled TG/DTA-MS spectra of ion fragments of identified gases evolved from thiourea under an Ar atmosphere. c ΔG of the sulfurization reaction between CS2 and LiOH with CO2 as byproduct by DFT calculation. d ΔG of the sulfurization reaction between CS2 and LiOH, with Li2CO3 as a byproduct by DFT calculation. e XRD patterns of the products from the solvent-free metathesis reaction at different synthesis temperatures.

To verify the feasibility of Eq. 3, the DFT method was used to calculate the ΔG of this metathesis reaction (Fig. 2c). The ΔG was less than 0 (\({\triangle G}_{r,m}^{\theta } < 0\)) and continuously decreased with the increase of the reaction temperature, indicating the thermodynamical spontaneity of Eq. (3) over 500 °C. It should be noted that the gaseous byproduct of CO2 may affect the purity of the Li2S main-product since CO2 can react with LiOH raw materials (Eq. (5)), resulting in the formation of the Li2CO3 impurity.

Taking the Li2CO3 byproduct into consideration, the ΔG of the metathesis reaction in Fig. 2d was calculated through the DFT method. The ΔG was less than 0 when the reaction temperature was in the range of 500 to 725 °C, indicating the coexistence of Li2S and Li2CO3 impurity. Nevertheless, the ΔG was over 0 when the reaction temperature exceeded 725 °C, proving that this reaction was not thermodynamically spontaneous in this temperature region (Fig. 2d). This result could be attributed to the thermal decomposition behavior of Li2CO3 at T > 727 °C (Eq. (6))43.

Then, no Li2CO3 impurity existed in the final product since the Li2O could be sulfured into Li2S by CS2 (Eq. (7)).

Guided by the DFT calculating results above, the solvent-free metathesis reaction of Eq. 1 was conducted at 600 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C and 900 °C (denoted as HY-Li2S-600, HY-Li2S-700, HY-Li2S-800 and HY-Li2S-900. HY is the abbreviation of lithium hydroxide) and the corresponding XRD patterns were recorded in Fig. 2e for comparison. All the synthesized samples contained the characteristic peaks of the Li2S phase (PDF#23-0369), indicating the formation of the Li2S product during the calcination process above 600 °C. A secondary Li2CO3 phase (marked with red #) was detected in HY-Li2S-600 and HY-Li2S-700 samples, proving that the Li2CO3 byproduct formed in a relatively low-temperature range of 600–700 °C. As temperatures rise, the Li2CO3 phase disappeared due to the thermal decomposition of Li2CO3 at T > 727 °C (Eq. (6))43, which matched well with the DFT calculation result (Fig. 2d). The generated Li2O from Eq. (6) could be sulfurized to Li2S by CS2 via Eq. (7). Hence, no Li2CO3 impurity phase was observed in the XRD patterns of HY-Li2S-800 and HY-Li2S-900 samples (Fig. 2e).

In addition, we considered that the byproduct of H2NCN (Fig. 2a, b) from Eq. (2) may affect the purity of the Li2S main-product since the H2NCN could decompose into a solid carbon residual compound44. Nevertheless, no ion fragments of H2NCN products could be detected during the solvent-free metathesis reaction between thiourea and LiOH (Fig. 3a). We proposed a probable reaction of Eq. (4) that the H2O intermedia product from Eq. (3) could react with H2NCN byproduct via hydrothermolysis reaction. As shown in Fig. 3b, ion fragments of NH3 (m/z = 17) and CO2 (m/z = 44) products were observed above 300 °C during the reaction between H2NCN and H2O, confirming the feasibility of Eq. (4). Therefore, we speculated that no carbon residue would be generated in the Li2S main-product due to the elimination of H2NCN through the hydrothermolysis reaction with H2O intermedia product.

a Online coupled TG/DTA-MS spectra of ion fragments of identified gases evolved from the metathesis reaction between thiourea and LiOH under Ar atmosphere. b Online coupled TG/DTA-MS spectra of ion fragments of identified gases evolved from the metathesis reaction between H2NCN and H2O under Ar atmosphere. c Illustration of the solvent-free metathesis reaction using Li2CO3 instead of LiOH. d Rietveld refinement of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 sample. e The digital pictures of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 products. f The Ramanspectra of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 samples. g Polarization current-time curves of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 samples. h The detailed reaction process of the solvent-free metathesis reaction.

To further investigate the elimination mechanism of carbon residue in Li2S main-product, Li2CO3 was used as a raw material instead of LiOH for the synthesis of Li2S since no H2O intermediate product formed during this metathesis reaction (Fig. 3c), which could be employed as a comparison experiment (Eq. (8)):

The solvent-free metathesis reaction between Li2CO3 and thiourea was conducted at 600 °C, 700 °C and 800 °C (denoted as CA-Li2S-600, CA-Li2S-700 and CA-Li2S-800. CA is the abbreviation of lithium carbonate) and the corresponding XRD patterns were recorded in Supplementary Fig. 2. No Li2CO3 phase could be observed in CA-Li2S-800 sample and the refined XRD patterns of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 proved that both products were in a Li2S single phase form (Fig. 3d). Detailed Rietveld refinements data were listed in Supplementary Table 2 and the SEM images of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 were displayed in Supplementary Fig. 3. The appearance of HY-Li2S-800 product was pure gray, while some dark gray area could be observed in the appearance of CA-Li2S-800 (Fig. 3e). Besides, the HY-Li2S-800 presented greyish white while the CA-Li2S-800 showed light yellow when dissolved in absolute alcohol (Supplementary Fig. 4). Subsequently, Raman spectroscopy was used to test the carbon impurity in HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 samples. The Raman spectra of amorphous carbon possesses two peaks, the D-band peak around 1350 cm–1 and the G-band peak around 1580 cm–1 45,46. No peaks of D-band or G-band could be seen in HY-Li2S-800 sample, proving the absence of residual carbon in the Li2S main-product (Fig. 3f). In contrast, two obvious peaks of D-band (at 1350 cm–1) and G-band (at 1580 cm–1) appeared in CA-Li2S-800 sample (Fig. 3f), indicating the formation of residual carbon byproduct through the thermolysis of H2NCN (Fig. 3c). Meanwhile, potentiostatic polarization method was employed to verify the effect of residual carbon on the electronic conductivity of HY-Li2S-800 and CA-Li2S-800 products (Fig. 3g). Based on the steady-state current, the electronic conductivity of CA-Li2S-800 could be calculated as high as 1.17 × 10–6 S/cm due to the existence of residual carbon. In contrast, without the residual carbon, the electronic conductivity of HY-Li2S-800 was only 1.71 × 10–8 S/cm, which exhibited a two-order-of-magnitude decrease compared to CA-Li2S-800 products. Therefore, with the assistance of H2O intermedia product, the carbon impurity could be eliminated due to the depletion of H2NCN through Eq. (4), leading to the formation of high-purity Li2S main-product with only CO2 and NH3 gaseous byproducts. Based on the reaction mechanisms analyzed above, the detailed reaction process with the corresponding temperature range was illustrated in Fig. 3h.

Scale-up feasibility, cost analysis and sustainability evaluation

To verify whether this solvent-free metathesis method was suitable for large-scale production of Li2S, the quantity of raw materials for manufacturing 100 g Li2S product in one batch (denoted as Li2S-Smeta) was increased. Here, Li2S-Smeta refers to bulk Li2S obtained from the scaled-up solvent-free metathesis reaction. Nearly 1 Kg Li2S product could be obtained in ten batches (Fig. 4a), and no secondary phase could be observed from the refined XRD patterns of the Li2S-Smeta sample, proving the formation of the pure phase Li2S (Fig. 4b). In addition, potentiostatic polarization method was employed to calculate the electronic conductivity of Li2S-Smeta products (Fig. 4c). Based on the steady-state current, the electronic conductivity of Li2S-Smeta product was 2.45 × 10–8 S/cm, closely matching the values of HY-Li2S-800 samples (Fig. 3g). The yield of the Li2S-Smeta products is approximately 95.4%. SEM imaging of the Li2S-Smeta products (Supplementary Fig. 5a) reveals numerous pores, which can be attributed to the formation of gaseous byproducts during the metathesis reaction. The average particle size (D50) of the Li2S-Smeta products is 1.2 μm, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5b. Based on ICP and high-frequency infrared carbon-sulfur analysis, the total impurity content in the Li2S-Smeta products is less than 0.2 wt.%. The constituent impurities and their respective concentrations are listed in Supplementary Table 3. All aforementioned results demonstrated the feasibility of this solvent-free metathesis reaction technique in large-scale.

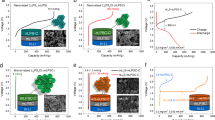

a Large-scale (100 g/batch) synthesis of 1 Kg high-purity Li2S-Smeta products. b Rietveld refinement of Li2S-Smeta sample. c Polarization current-time curves of Li2S-Smeta sample. d Radar plots comparing the properties among different Li2S synthesis methods. e Total costs of different Li2S synthesis methods. f Appearance of the LGPS-SmetaLi2S products. g XRD patterns of LGPS-SmetaLi2S and LGPS-Commercial products. h EIS spectra of LGPS-SmetaLi2S and LGPS-C Commerical samples. i Comparison of the materials cost between LGPS-CommLi2S and LGPS-SmetaLi2S. j Appearance of the LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S products. k XRD patterns of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-Commerical products. l EIS spectra of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-Commerical samples. m Comparison of the materials cost between LPSC1.5-CommLi2S and LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S.

A comparison of various properties among the current Li2S synthesis methods, including thermoreduction method8,9, liquid reduction method12, H2S sulfurating Li metal method18, H2 reduction method19 and liquid metathesis method22, were showed in Fig. 4d, and all the detailed properties was displayed in Supplementary Table 1. Besides, we have conducted a detailed total costs (including raw materials costs, synthesis condition costs and purification costs) comparison between this work and other highly promising Li2S synthesis methods (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Tables 5–11). Although the reaction between LiH and S can directly produce pure Li2S without an additional purification step, the high price of LiH raw material rendered this method unsuitable for the industrial-scale production of Li2S (Supplementary Table 5). The cost of LiOH and S are cheap, but the Li2S product requires N-propanol purification, resulting in huge purification costs (Supplementary Table 6). H2 can reduce Li2SO4 to pure Li2S, while the explosive nature of H2 can not be ignored. (Supplementary Table 7). Both thermal reduction method (Al/sucrose reduce Li2SO4) and liquid metathesis method (LiCl react with Na2S) utilize inexpensive raw materials and ethanol purification step, whereas ethanol can not be totally recycled for repeated use47,48, leading to an increase in purification costs (Supplementary Tables 8–10). In contrast, by utilizing economical LiOH and thiourea as raw materials, our solvent-free metathesis can produce pure Li2S products directly without purification step, achieving substantial total costs savings (Supplementary Table 11). In addition, considering the potential impact of CO2 on the greenhouse effect, a simple aluminum water tank was integrated at the reactor exhaust outlet. The exhausted CO2 was fixed by rapid reaction with NH3 byproducts in the aqueous phase and generated a non-toxic/non-volatile NH4HCO3 final product. Consequently, the actual CO2 emissions from this reaction exert a negligible impact on the greenhouse effect.

Application demonstration in sulfide-based solid electrolytes

To test whether the Li2S-Smeta products could be used for the large-scale production of sulfide-based SSEs, two types of classic sulfide-based electrolytes, LGPS and LPSC1.5, were manufactured on a large scale of 100 g in one batch by utilizing the Li2S-Smeta products as raw materials (denoted as LGPS-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S). By contrast, commercial Li2S was also used to manufacture LGPS and LPSC1.5 products under the same synthesis conditions (denoted as LGPS-CommLi2S and LPSC1.5-CommLi2S). The detailed preparation procedures were described in the Experimental Section.

To achieve LGPS products, the ball-milled 100 g yellow precursor powders (Supplementary Fig. 6) were pelletized and then sintered at 550 °C under vacuum conditions. 93.82 g LGPS products were attained for one batch with a high yield rate of 93.82% (Fig. 4f). The XRD patterns of the LGPS-SmetaLi2S and LGPS-CommLi2S products (Fig. 4g) matched well with the standard XRD profile of LGPS (PDF#970188886). The corresponding refined XRD patterns of LGPS-SmetaLi2S and LGPS-CommLi2S showed that the products were in LGPS single-phase form (Supplementary Fig. 7). The SEM image of LGPS-SmetaLi2S was displayed in Supplementary Fig. 8a, and the corresponding D50 value for LGPS-SmetaLi2S products were 0.76 μm (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

To compare the electrochemical performance of LGPS-SmetaLi2S to that of LGPS-CommLi2S products, an electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) test was conducted to measure their ionic conductivity at room temperature. The semi-circle of LGPS-SmetaLi2S in the Nyquist impedance plots at high frequencies was about 26.5 Ω, which was very close to 25.6 Ω of LGPS-CommLi2S in Fig. 4h. The calculated ionic conductivity was 4.8 mS/cm for LGPS-SmetaLi2S and 5.0 mS/cm for LGPS-CommLi2S samples, indicating that both products exhibited a high ionic conductivity at room temperature. Consequently, the performance of Li2S-Smeta products is relatively similar to that of commercial Li2S. Based on the current market price (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Table 12), the cost of LGPS-SmetaLi2S falls by 27.5% to that of LGPS-CommLi2S sample, indicating the practical value of the Li2S-Smeta product (Fig. 4i).

In addition, LPSC1.5 was also manufactured in one batch of 100 g synthesis. The ball-milled 100 g yellow precursor powders (Supplementary Fig. 9) were pelletized and heated at 500 °C under vacuum. 94.63 g LPSC1.5 products could be obtained for one batch with a high yield rate of 94.63% (Fig. 4j). The XRD patterns of the LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-CommLi2S products (Fig. 4k) were in accordance with the standard characteristic peaks of argyrodite-Li7PS6 (PDF#970418490). The corresponding refined XRD patterns of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-CommLi2S showed that the products were phase pure (Supplementary Fig. 10). The SEM image of LPSC1.5-CommLi2S is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11a, and the corresponding D50 value for LPSC1.5-CommLi2S products was 0.54 μm (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Furthermore, the EIS method also tested the electrochemical performance of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-CommLi2S products. The semi-circle of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S at high frequencies was about 30.7 Ω, comparable to that (about 31.5 Ω) of LPSC1.5-CommLi2S product (Fig. 4l). The calculated ionic conductivity was 4.1 mS/cm for LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and 4.0 mS/cm for LPSC1.5-CommLi2S samples, which was acceptable for a typical Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 electrolyte3. Based on the current market price (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Table 13), a huge decline (92.9%) could be seen when compare the cost of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S than that of LPSC1.5-CommLi2S sample (Fig. 4m). Therefore, the properties of Li2S-SmetaLi2S products are eligible for scaleable manufacture of sulfide solid electrolyte in low-cost.

To verify that the Li2S synthesized by the metathesis method proposed in this study can be used as a primary raw material for the synthesis of sulfide-based solid electrolytes, we have assembled all-solid-state batteries using the LPSC1.5 (LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S) synthesized in this study as an example of a solid electrolyte and compared the performance of the ASSB assembled with the commercial Li2S-synthesized LPSC1.5 (LPSC1.5-CommLi2S). The lab-scale ASSB was constructed using LiCoO2@LiNbO3 (LCO@LNO) and Li-In as positive electrode and negative electrode, respectively (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b shows a physical, electronic photograph of an assembled Li-In|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB that can normally light up three LED light bulbs at ambient temperature, indicating that LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S is a pure lithium ionic conductor material having negligible electronic conductivity. As a comparison, LPSC1.5-CommLi2S was also employed as an electrolyte for Li-In|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB assembling. Both ASSBs displayed a dQ/dV reduction peak around 3.3 V, indicating the Li+ intercalation/deintercalation from the host lattices of the positive electrode. In addition, no dQ/dV reduction peak could be observed below 3.3 V, suggesting the excellent compatibility and stability of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S electrolyte in this voltage region (Fig. 5c)49. The Li-In|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB delivered a discharge capacity of 100.14 mAh/g, 75.08 mAh/g and 36.75 mAh/g at 0.05 C, 0.1 C and 0.2 C (Fig. 5d), which was comparable to that of the Li-In|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB (Fig. 5e, 100. 48 mAh/g, 74.8 mAh/g and 35.11 mAh/g at 0.05 C, 0.1 C and 0.2 C). When the current density backed to 0.05 C, both of the two ASSBs’ discharge capacity could maintain about 90% of the initial capacity, and no significant property divergence was observed in rate capability (Fig. 5f).

a Illustration of the (Li-In or Si)|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB. b A digital picture of Li-In|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB that works at ambient temperature to make the LED bead light up. c The dQ/dV curves of Li-In|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO and Li-In|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB. d Charge–discharge curves of Li-In|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB at 0.05 C (6.85 mA g–1, 0.049 mA cm–2), 0.1 C (13.7 mA g–1, 0.098 mA cm–2) and 0.2 C (27.4 mA g–1, 0.195 mA cm–2) under 25 °C with a. e Charge–discharge curves of Li-In|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB at 0.05 C (6.85 mA g–1, 0.049 mA cm–2), 0.1 C (13.7 mA g–1, 0.098 mA cm–2) and 0.2 C (27.4 mA g–1, 0.195 mA cm–2) under 25 °C. f Rate capability of Li-In|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO and Li-In|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB. g The second charge–discharge curves of Si|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO and Si|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB at 0.1 C (420 mA g–1, 11.24 mA cm–2) under 25 °C. h Cycling stability of Si|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO and Si|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB. The active material loadings were 7.13 mg/cm2 for LCO and 26.8 mg/cm2 for Si.

To test the electrochemical performance of LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S and LPSC1.5-CommLi2S electrolyte in practical battery systems, the Li-In negative electrode was displaced by commercial Si for the assembling of ASSBs (denoted as Si|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO and Si|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO). As illustrated in Fig. 5g, the second charge/discharge curves of both ASSBs overlap substantially, confirming minimal performance divergence. Besides, Si|LPSC1.5-SmetaLi2S | LCO@LNO offered a discharge capacity of 104 mAh/g at the first cycle, and 68.5% (71.2 mAh/g) was retained after the fiftieth cycle at 0.05 C (6.85 mA/g, 0.049 mA/cm2). Similarly, Si|LPSC1.5-CommLi2S | LCO@LNO ASSB could retain 69.7% (72.4 mAh/g) of its initial discharge capacity (103.8 mAh/g) after 50 cycles (Fig. 5h). There is no particularly noticeable electrochemical performance difference between the two ASSBs based on the same battery assembly conditions, providing preliminary evidence that the Li2S products synthesized by the method proposed in this study have a utility comparable to that of commercial lithium sulfide but with a higher single-batch yield, and demonstrating the possible commercial potential for the large scale and inexpensive synthesis of sulfide-based solid electrolytes.

Discussion

A solvent-free metathesis strategy, guided by DFT calculations, was developed for the acalable synthesis of high-purity Li2S at low cost. The reaction produces only CO2 and NH3 as gaseous byproducts, which could be efficiently and automatically separated from the Li2S product without affecting the chemical equilibrium (ΔGmix ≈ 0), thereby driving complete conversion to Li2S without additional purification steps. This approach enables the production of substantial quantities of Li2S per batch (approaching 100 g), rendering it highly suitable for cost-effective, industrial-scale manufacturing. The synthesized Li2S serves as a direct precursor for conventional sulfide-based solid electrolytes, including Li10GeP2S12 and Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5, reducing the projected material costs for these sulfide-based solid electrolytes by up to 27.5% and 92.9%, respectively. Notably, all-solid-state batteries assembled with Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 derived from this Li2S exhibit electrochemical performance comparable to those counterparts using commercial Li2S. Overall, this environmentally benign, scalable metathesis approach may not only substantially lowers the cost of producing sulfide-based solid electrolytes but also facilitates the practical deployment of all-solid-state batteries, offering a promising pathway toward sustainable energy storage technologies.

Methods

Materials synthesis

Synthesis of Li2S

Li2S was synthesized via a solvent-free metathesis reaction between thiourea and LiOH (Eq. (1)), denoted as HY-Li2S, with the suffix numbers (600, 700, 800, 900) representing sintering temperatures in °C. Thiourea decomposes above 200 °C to release CS2, while the reaction of CS2 with LiOH to form Li2S occurs above 400 °C. To compensate CS2 loss in the 200 °C–400 °C window, excess thiourea was added. Typically, 2 mmol LiOH and 1.2 mmol thioureawere mixed in a 45 mL ZrO2 jar with ZrO2 balls, ball-milling at 400 rpm for 8 h, pelletized at 100 MPa, and sintered in a tubular furnace for 8 h under folowing N2 (99.999%,1 SCCM) with a heating rate of 2 °C/min. Zeolite molecular sieves were placed at both ends of the tube to maintain a dry atmosphere. HY-Li2S-600 was obtained at 600 °C, while HY-Li2S-700, HY-Li2S-800, and HY-Li2S-900 were prepared analogously at 700, 800, and 900 °C, respectively. Li2S synthesized via metathesis between thiourea and Li2CO3 (Eq. (8)) is denoted as CA-Li2S, with the suffix numbers (600, 700, 800) representing sintering temperatures. The synthesis procedure was identical to that of HY-Li2S, except that 1 mmol Li2CO3 and 1.2 mmol thiourea were used as precursors. CA-Li2S-600, CA-Li2S-700, and CA-Li2S-800 were obtained at 600, 700, and 800 °C, respectively. Li2S-Smeta refers to bulk Li2S obtained from the scaled-up metathesis reaction. For large-scale production, typically, Li2S-Smeta was prepared using 104.3 g LiOH and 198.5 g thiourea under the same ball-milling and sintering conditions as HY-Li2S, except that a 1 L ZrO2 jar and larger quantities of milling media were employed. The products were sintered at 800 °C for 8 h, and the exhaust gas was passed through a Ca(OH)2 solution to capture byproducts. Thiourea, LiOH, P2S5, and Li2CO3 (all 99.9 wt.% purity) were obtained from Energy Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Ca(OH)2 (90 wt.% purity) was obtained from Energy Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China and used to prepare the aqueous solution.

Synthesis of classical sulfide solid electrolytes

LGPS and LPSC1.5 were synthesized using either Li2S-Smeta or commercial Li2S as the lithium sulfide source, denoted as LGPS-SmetaLi2S/LGPS-CommLi2S and LPSC1.5-SmetaLi₂S/LPSC1.5-CommLi2S, respectively. Stoichiometric amounts of the corresponding precursors were ball-milled at 400 rpm for 8 h in a 1 L ZrO2 jar, pelletized at 100 MPa and sealed in evacuated tubes (2 × 10−3 Pa). LGPS samples were sintered at 550 °C for 8 h, while LPSC1.5 samples were sintered at 500 °C for 12 h, both with a heating rate of 2 °C/min. LiCl, P2S5 and commercial Li2S (all 99.9 wt.% purity) were obtained from Energy Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

Electrochemical measurements

AC impedance measurements were conducted to determine ionic conductivities of 10 mm diameter SE pellets prepared at 303 MPa in polyaryletherketone molds. A symmetric cell configuration (SS | SE | SS) was employed at 25 °C using a Bio-Logic VSP-300 electrochemical workstation. Impedance spectra were recorded with 15 mV perturbation over 1 Hz-7 MHz frequency range, with each sample measured 2–3 times for consistency. The ionic conductivity was determined from the ohmic resistance at the high-frequency intercept of the semicircle in the EIS spectra. Due to the idealized nature of the spectra and the small resistance (~30 Ω), this method provides an accurate estimation, consistent with equivalent-circuit fitting. The electrical conductivity was investigated by the Hebb-Wagner polarization method50.

Electrodes and cell assembly

All-solid-state batteries were assembled using the synthesized Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 (LPSCl1.5) in an Ar-filled glovebox (O2, H2O < 0.1 ppm). Approximately 100 mg of LPSCl1.5 powder was cold-pressed into 10 mm diameter pellets at 227 MPa. Large particles were removed from the powder using a 10 μm mesh sieve prior to pellet formation. The Li–In alloy negative electrode was prepared in situ by sequentially stacking indium and lithium foils (0.1 mm thick, 5 mm diameter, 99.9 wt.%, MTI Corporation, Shenzhen, China) onto the electrolyte pellet and cold-pressing at 250 MPa for 1 min. The positive electrode comprised either LiNbO3-coated LiCoO2 (LCO@LNO, 1 C = 137 mAh g−1) or Si (1 C = 4200 mAh g−1, D50 = 600 nm), each mixed with LPSCl1.5 at a weight ratio of 7:3. The LCO@LNO and Si powders (99.9 wt.% purity, MTI Corporation, Hefei, China) were used as received. Cathode composites were pressed onto Al mesh (0.055 mm thick, 10 mm diameter, pore size 0.4 × 1.5 mm) and Al foil current collectors (0.1115 mm thick, 10 mm diameter). The positive electrode contained 5.6 mg of LCO active material (loading: 7.13 mg cm−2), while the negative electrode contained 21 mg of Si active material (loading: 26.8 mg cm−2), resulting in an N/P ratio of 115.0 for the Si-based cell. The battery assembly method was akin to those documented in previous reports51. During full cell assembly, the electrode–electrolyte stack was cold-pressed at 200 MPa to ensure intimate contact, and this pressure was maintained throughout electrochemical testing. Charge–discharge measurements were performed using a LANHE CT2001A system (Wuhan LAND Electronics Co., Wuhan, China) at 0.05 C (6.85 mA g−1, 0.049 mA cm−2), 0.1 C (13.7 mA g−1, 0.098 mA cm−2), and 0.2 C (27.4 mA g−1, 0.195 mA cm−2) for LCO@LNO-based cells and at 0.1 C (420 mA g−1, 11.24 mA cm−2) for Si-based cells. Li–In half-cells were cycled between 1.9–3.6 V (vs. LiIn/Li+), while Si-based cells were cycled between 2.4–4.0 V. All electrochemical measurements were conducted at 25 ± 0.5 °C in a temperature-controlled chamber under static air. Multiple independent cells were tested, and the data presented represent typical trends.

Physical characterization

SEM: SEM images were obtained on a JEOL JSM-6390 microscope (Japan).

XRD: Phase identification of the synthesized materials was performed using X-ray diffraction with CuKα1 radiation on a Bruker D6 Phaser system (Germany). To prevent moisture exposure, samples were handled in an inert atmosphere and protected with polyimide film (Meixin Co., Dongguan, China) during analysis. Diffraction patterns were recorded from 10° to 70° in 2θ with 0.01° increments. Powder diffraction data were analyzed through Rietveld refinement using the GSAS software package. Crystal structures visualization was accomplished with VESTA and 3ds Max programs.

TG/DTA-FTIR: Thermal decomposition behavior was investigated using simultaneous TG/DTA-FTIR analysis with a Netzsch STA449F3 thermal analyzer (Germany) coupled to a Nicolet IS20 FTIR spectrometer (USA). Sample masses of 4 ± 0.02 mg were loaded in Al2O3 crucibles and subjected to controlled heating (50–800 °C, 10 °C/min) under flowing argon (50 mL/min). The transfer line was maintained at 255 °C to prevent condensation of evolved gases. FTIR detection covered 400-4000 cm−1 with 8 cm−1 resolution.

TG/DTA-MS Analysis: Evolved gas analysis was performed using combined TG/DTA-MS instrumentation comprising a Netzsch STA449F3 analyzer (Germany) interfaced with a QMS 403 Aeolos mass spectrometer (Germany). Samples (4 ± 0.02 mg) in Al2O3 crucibles underwent thermal treatment from 50-800 °C at 10 °C/min under argon flow (50 mL/min). The heated capillary connection (265 °C) prevented vapor condensation during transfer. Mass spectrometric detection employed MID mode monitoring m/z ratios of 17, 18, 42, 44 and 76 for key fragment identification. Argon purging (1 h) preceded measurements to establish inert conditions.

ICP testing: The elemental composition of the Li2S-Smeta sample was conducted by using ICP-OES measurements (Agilent 5110, America). The Pump Rate was 60 r/min; Plasma gas was 12.0 L/min; Nebulizer Flow was 0.70 L/min, Auxiliary Gas was 1.0 L/min, RF Power was 1250 W.

High-frequency infrared carbon–sulfur analyzer testing: The carbon content of the Li2S-Smeta sample was conducted by using High-frequency infrared carbon–sulfur analyzer (HCS-140, China). The Oxygen flow rate was 1.5 L/min, Purge time was 20 S, Integration Delay was 10 S, O2 Supply Pressure was 0.25 MPa.

Raman spectra characterization: Raman spectroscopy was conducted using a Horiba LabRAM single-stage system (Japan) equipped with a Symphony CCD detector (Jobin Yvon, France) featuring 2048 horizontal pixels. An Ar+ laser (514 nm) was employed at power levels below 0.1 mW to prevent sample damage, providing 3.0 cm−1 spectral resolution. Measurements were obtained from ~1 μm2 focal areas on the sample surface.

First-principle calculation: The density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)52. Exchange-correlation effects were treated with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional under generalized gradient approximation (GGA)53, employing projectoraugmented-wave pseudopotential (PAW)54 with a 500 eV plane-wave cut-off for basis set expansion. Brillouin zone sampling utilized a Γ-centered 5 × 5 × 5 Monkhorst-Pack mesh, while structural optimization continued until convergence criteria of 1 × 10−5 eV (energy) and 0.03 eV/Å (forces) were satisfied. Van der Waals interactions were incorporated through DFT-D dispersion corrections55. Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) was evaluated using the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model as follows:

Here, ΔE represents the reaction energy difference between adsorbed reactants and products, ΔS denotes entropy contributions, and ΔZPE accounts for zero-point energy correction to the Gibbs free energy.

Data availability

Source Data file and DFT calculations data have been deposited in Figshare under accession code DOI link https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29519825.

References

Chen, Y. et al. Recent progress in all-solid-state lithium batteries: the emerging strategies for advanced electrolytes and their interfaces. Energy Storage Mater. 31, 401–433 (2020).

Kamaya, N. et al. A lithium superionic conductor. Nat. Mater. 10, 682–686 (2011).

Adeli, P. et al. Boosting solid-state diffusivity and conductivity in lithium superionic argyrodites by halide substitution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8681–8686 (2019).

Li, F. et al. Electrolyte and interface engineering for solid-state sodium batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 65, 103181 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chlorine-Rich Na6−xPS5−xCl1+x: a promising sodium solid electrolyte for all-solid-state sodium batteries. Materials 17, 1980 (2024).

Kwak, H. et al. Emerging halide superionic conductors for all-solid-state batteries: design, synthesis, and practical applications. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1776–1805 (2022).

Tu, F. et al. Low-cost and scalable synthesis of high-purity Li2S for sulfide solid electrolyte. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 15365–15371 (2022).

Zhang, X., Yang, H., Sun, Y. & Yang, Y. Lithium sulfide: magnesothermal synthesis and battery applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 41003–41012 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. “One Stone Two Birds” strategy of synthesizing the battery material lithium sulfide: aluminothermal reduction of lithium sulfate. Inorg. Chem. 62, 5576–5585 (2023).

Wei, Y. et al. Low-cost preparation and purification of Li2S for sulfide solid electrolytes. J. Energy Storage 103, 114180 (2024).

Lin, Z., Liu, Z., Dudney, N. J. & Liang, C. Lithium superionic sulfide cathode for all-solid lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Nano 7, 2829–2833 (2013).

El-Shinawi, H., Cussen, E. J. & Corr, S. A. A facile synthetic approach to nanostructured Li2S cathodes for rechargeable solid-state Li–S batteries. Nanoscale 11, 19297–19300 (2019).

Li, X. et al. A mechanochemical synthesis of submicron-sized Li2S and a mesoporous Li2S/C hybrid for high-performance lithium/sulfur battery cathodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 6471–6482 (2017).

S.Yang, et al. Synthesis of deliquescent lithium sulfide in air. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 40633–40647 (2023).

Meng, X., Comstock, D. J., Fister, T. T. & Elam, J. W. Vapor-phase atomic-controllable growth of amorphous Li2S for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. ACS Nano 8, 10963–10972 (2014).

Li, X., Wolden, C. A., Ban, C. & Yang, Y. Facile synthesis of lithium sulfide nanocrystals for use in advanced rechargeable batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 28444–28451 (2015).

Zhao, Y., Smith, W. & Wolden, C. A. Scalable synthesis of Li2S nanocrystals for solid-state electrolyte applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 070520 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Yang, Y. & Wolden, C. A. Scalable synthesis of size-controlled Li2S nanocrystals for next-generation battery technologies. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2, 2246–2254 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. A green method of synthesizing battery-grade lithium sulfide: hydrogen reduction of lithium sulfate. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 2813–2824 (2024).

Smith, W. H., Vaselabadi, S. A. & Wolden, C. A. Synthesis of high-purity Li2S nanocrystals via metathesis for solid-state electrolyte applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 7652–7661 (2023).

Smith, W. H., Vaselabadi, S. A. & Wolden, C. A. Argyrodite superionic conductors fabricated from metathesis-derived Li2S. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 4029–4035 (2022).

Fang, L. et al. Green synthesis of the battery material lithium sulfide via metathetic reactions. Chem. Commun. 58, 5498–5501 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Green synthesis for battery materials: a case study of making lithium sulfide via metathetic precipitation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 1358–1366 (2023).

Sánchez, A. L., Fernández-Tarrazo, E. & Williams, F. A. The chemistry involved in the third explosion limit of H2–O2 mixtures. Combust. Flame 161, 111–117 (2014).

G, G. S. Solid-state double displacement reaction at room temperature. Resonance 23, 683-691 (2018).

Martin, R. B. Replace double replacement. J. Chem. Educ. 76, 133 (1999).

Wildman, E. A. et al. The double decomposition reaction. Proc. Ind. Acad. Sci. 41, 259–262 (1931).

Pinho, S. P. & Macedo, E. A. Solubility of NaCl, NaBr, and KCl in water, methanol, ethanol, and their mixed solvents. J. Chem. Eng. Data 50, 29–32 (2005).

Atkins, P. Physical Chemistry, 11th ed. Oxford; New York, (1994).

Schultz, M. J. Why equilibrium? Understanding entropy of mixing. J. Chem. Educ. 76, 1391 (1999).

Juan José, S.-P. & Juan, Q.-P. Thermodynamics and Le Chatelier’s principle. Rev. Mex. Fis. 41, 128–138 (1994).

Quílez, J. First-year university chemistry textbooks’ misrepresentation of gibbs energy. J. Chem. Educ. 89, 87–93 (2012).

Tomba, J. P. Understanding chemical equilibrium: the role of gas phases and mixing contributions in the minimum of free energy plots. J. Chem. Educ. 94, 327–334 (2017).

Yang, D., Chen, Y.-C. & Zhu, N.-Y. Sterically bulky thioureas as air- and moisture-stable ligands for pd-catalyzed Heck reactions of aryl halides. Org. Lett. 6, 1577–1580 (2004).

Madarász, J. & Pokol, G. Comparative evolved gas analyses on thermal degradation of thiourea by coupled TG-FTIR and TG/DTA-MS instruments. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 88, 329–336 (2007).

Suresh, C. H. & Anila, S. Molecular electrostatic potential topology analysis of noncovalent interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 1884–1895 (2023).

Nakhli, A. et al. Molecular insights through computational modeling of methylene blue adsorption onto low-cost adsorbents derived from natural materials: a multi-model approach. Comput. Chem. Eng. 140, 106965 (2020).

Janani, S., Rajagopal, H., Muthu, S., Aayisha, S. & Raja, M. Molecular structure, spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, NMR), HOMO-LUMO, chemical reactivity, AIM, ELF, LOL and Molecular docking studies on 1-Benzyl-4-(N-Boc-amino)piperidine. J. Mol. Struct. 1230, 129657 (2021).

Fukui, K., Yonezawa, T. & Shingu, H. A molecular orbital theory of reactivity in aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 20, 722–725 (1952).

Fukui, K. Role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. Science 218, 747–754 (1982).

Harada, S., Takenaka, H., Ito, T., Kanda, H. & Nemoto, T. Valence-isomer selective cycloaddition reaction of cycloheptatrienes-norcaradienes. Nat. Commun. 15, 2309 (2024).

Levandowski, B. J., Svatunek, D., Sohr, B., Mikula, H. & Houk, K. N. Secondary orbital interactions enhance the reactivity of alkynes in Diels–Alder cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2224–2227 (2019).

Shi, L. et al. Process of thermal decomposition of lithium carbonate. Mater. Process. Fundam. 7, 107–116 (2020).

Morita, K. et al. Thermal stability, morphology and electronic band gap of Zn(NCN). Solid State Sci. 23, 50–57 (2013).

Matthews, M. J., Pimenta, M. A., Dresselhaus, G., Dresselhaus, M. S. & Endo, M. Origin of dispersive effects of the raman d band in carbon materials. Phys. Rev. B 59, R6585–R6588 (1999).

Ferrari, A. C. & Robertson, J. Interpretation of raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 14095–14107 (2000).

Zhang, J. et al. In-situ vacuum distillation of ethanol helps to recycle cellulase and yeast during SSF of delignified corncob residues. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 11676–11685 (2017).

Lewandowicz, G., Białas, W., Marczewski, B. & Szymanowska, D. Application of membrane distillation for ethanol recovery during fuel ethanol production. J. Membr. Sci. 375, 212–219 (2011).

Peng, L. et al. Tuning solid interfaces via varying electrolyte distributions enables high-performance solid-state batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. 6, e12308 (2022).

Neudecker, B. J. & Weppner, W. Li9SiAlO8: a lithium ion electrolyte for voltages above 5.4 V. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 2198–2203 (1996).

Zhao, G. et al. Extending the frontiers of lithium-ion conducting oxides: development of multicomponent materials with γ-Li3PO4-type structures. Chem. Mater. 34, 3948–3959 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Provincial Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Hubei Province, China (2023AFA064), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22109049, 52573346), Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2025DJB063), the Key Project of Scientific Research Program of Hubei Provincial Department of Education, China (D20222901) and the Key Laboratory of Catalysis and Energy Materials Chemistry of Ministry of Education & Hubei Key Laboratory of Catalysis and Materials Science (202306). The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Ryoji Kanno and Prof. Kota Suzuki from the Institute of Science Tokyo for their invaluable guidance and critical feedback during manuscript preparation and revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. conceived the idea and supervised the project. Y.Z. and L.G. designed the experiments. Y.Z., L.G. and Ha.Z. performed the synthesis, characterization, related electrochemical tests, battery property tests and data analysis. Ho.Z. conducted the mechanistic studies and theoretical calculations. Y.Z., L.G. and G.Z. co-wrote and revised the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hirotada Gamo and Nataly Carolina Rosero-Navarro for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Gao, L., Zheng, H. et al. Advancing sulfide solid electrolytes via green Li2S synthesis. Nat Commun 16, 9981 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64924-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64924-8