Abstract

Electrochromic (EC) devices based on structurally designable and color-tunable EC molecules can dynamically regulate light-heat transmittance via the charge-transfer mechanism, yet face challenges of limited near-infrared (NIR) absorption, long-term instability, and restricted modulation modes. Here, we show that π-stacking of heteroaromatic tri-pyridine molecules with a 1,3,5-triazine core (H-TriPy) enhances molecular conjugation, significantly augments NIR absorption, and enables dual-band modulation with improved visual comfort. The three pyridine-based redox centers facilitate multi-step electron transfer, enabling multi-modal EC regulation, including bright, cool, and dark modes. Incorporation of a fluorinated ionic liquid into EC organogels inhibits irreversible π-stacking of high-concentration H-TriPy. Consequently, H-TriPy-based EC devices achieve neutral-colored states with near-zero transmittance as low as 3.7% in both visible and NIR ranges and maintain high switching stability of over 89.1% retention after 100,000 cycles. Furthermore, large-area EC devices exhibit uniform tinting and reliable stability, underscoring their potential for energy-efficient green buildings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Controllably regulating the flow of light and heat to achieve energy conservation and emission reduction is a vital strategy for combating global warming and achieving carbon neutrality1,2. In buildings, sunlight from visible to near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths passes through glass windows as primary light and heat sources3,4. To maintain indoor light and thermal comfort, lighting, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems are utilized with high energy consumption, contributing to nearly 20% of energy consumption in buildings5,6.

Electrochromic (EC) windows, pioneered by S. K. Deb’s foundational discoveries on the optical tunability of tungsten oxide and advanced through C. G. Granqvist’s architectural applications, have become a transformative technology for energy-efficient buildings7,8. By dynamically modulating solar radiation, EC windows can regulate both thermal regulation with visual comfort, and emerge as a powerful tool for decarbonization and human-centric building design9,10. For the widespread adoption of EC windows, three key requirements must be met: (1) Dual-band modulation across both visible and NIR range (i.e., solar range) is the basis for optimizing daylight quality, blocking NIR thermal radiation, and enhancing energy efficiency11,12. (2) Near-zero sunlight transmittance, representing the pinnacle of EC performance, minimizes indoor heat gain and significantly reduces energy consumption while ensuring visual comfort under intense light13. (3) Scalable production enables cost-efficient manufacturing and consistent high-quality output, all of which are critical for the commercial viability of EC windows14.

Organic EC materials offer highly tunable molecular and electronic structures, enabling facile synthesis, solution processability, and vivid coloration, thus expanding the control over redox behavior15,16,17. By adjusting molecular conjugation length and the electron donor-acceptor configuration, absorption peaks in the visible and NIR ranges can be selectively modulated18,19. Across them, small EC molecules, such as viologen20,21, triarylamine22,23, and metal-organic coordination compounds24,25, can be rationally designed to enhance light absorption. Additionally, these EC molecules are solution-processable for scalable all-in-one devices, thereby avoiding the complex and high-energy consumption fabrication processes of multilayered EC devices. For example, by altering the structure of these small EC molecules, their color can be adjusted to transition from the initial state to blue, green, or magenta26,27. Among various substituents, the butyl side chain offers an intermediate chain length that balances π-stacking flexibility with steric hindrance, effectively avoiding the excessive aggregation typically found in short alkyl chains (e.g., propyl) and the steric hindrance associated with long alkyl chains (e.g., heptyl)28,29.

Achieving a neutral-color state, considered the “holy grail” of EC technology, requires complementary absorption from multiple small EC molecules to cover the visible range30,31. Ionic liquids (IL), defined as liquid organic salts at room temperature, are ideal electrolytes for various electrochemical applications due to their high ionic conductivity, wide electrochemical window, low volatility, and excellent thermal and chemical stability32,33,34. Incorporating IL with EC molecules into organogels reduces driving potential and improves their kinetics, thereby mitigating organogels degradation and enhancing overall EC performance35,36,37. Despite these advancements, challenges remain: (1) Most EC molecules lack NIR absorption due to their limited conjugation, and fail to meet dual-band EC window requirements. (2) While neutral-colored states are achieved, attaining near-zero transmittance remains difficult due to the low concentration of EC materials in all-in-one electrolytes. Increasing their concentration often destabilizes EC devices due to irreversible stacking effects38,39. (3) EC molecules typically lack multiple redox centers and only allow one or two electron transfers, restricting the development of multi-modal EC modulation.

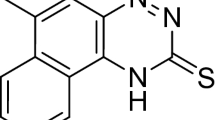

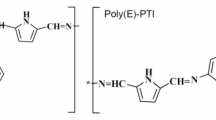

In this work, we demonstrate that a heteroaromatic tri-pyridine molecule (termed H-TriPy), featuring a triazine core and butyl side group, enhances molecular conjugation, leading to a redshifted absorption band (Fig. 1a). With the reduction at the electrode interface, heteroaromatic π-stacking engineered in H-TriPy highly augments the NIR absorption via a distinctive “pancake bond”, with a high optical contrast of 90.7% at 854 nm. (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, the three pyridine-based redox centers for multi-step electronic transfer enable three EC modes to address varying visual comfort needs for bright, cool, and dark. Furthermore, fluorinated ionic liquid (F-IL) is introduced to generate strong polar interactions of -F groups with H-TriPy in EC organogels, effectively dissociating the “pancake bond” of π-stacked H-TriPy at high concentrations. As a result, the H-TriPy-based EC devices achieve neutral-colored states with an average transmittance of below 1.6% across both visible and NIR ranges, and show high electrochemical stability (89.1% retention exceeding 100,000 cycles), which to the best of our knowledge represents the highest stability reported for small-molecule-based EC devices (i.e., all-in-one devices).

a Design principle of H-TriPy molecules for heteroaromatic π-stacking engineered for NIR absorption. b UV-Vis-NIR transmittance spectra of all-in-one EC devices based on typical butyl viologen (BV) (left) and H-TriPy (right) molecules under different modulation modes. Grey, blue, and red lines correspond to bright, cool, and dark states, while shaded grey, blue, and red areas denote the UV, visible, and NIR range of the solar irradiance spectra.

Results

Synthesis, electronic, and optical properties of H-TriPy

The heteroaromatic tri-pyridine molecule (H-TriPy), incorporating an optimally balanced butyl side chain to mitigate excessive π-stacking and steric hindrance, was synthesized via nucleophilic substitution and anion exchange (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). By introducing a triazine core and additional pyridine units, the H-TriPy molecule exhibits significant changes in its electronic and optical properties compared to conventional butyl viologen (BV), as revealed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations investigating the relationship between molecular structure and photophysical properties (Supplementary Fig. 3). According to the DFT results, H-TriPy exhibits a HOMO level of −14.84 eV and a LUMO level of −11.37 eV, which are lower than those of BV (−13.85 eV and −9.73 eV, respectively), indicating enhanced stability and greater resilience in oxidation and reduction processes. Furthermore, H-TriPy has a smaller bandgap of 3.47 eV compared to BV’s 4.12 eV, which improves its charge transport capabilities and enhances its efficiency in EC devices.

Regarding optical absorption, BV displays a maximum absorption peak at 254 nm with negligible absorption beyond 312 nm. In contrast, H-TriPy, owing to its 1,3,5-triazine core and additional pyridine units, extends π-conjugation, resulting in a pronounced redshift to 622 nm and a new maximum absorption at 318 nm. This structural modification enhances π-electron delocalization and reduces the energy barrier for π → π* transitions (Supplementary Fig. 4)40,41. In an all-in-one EC device, a high concentration of EC molecules significantly reduces the transmittance in the colored state, thereby achieving a near-zero transmittance. The anion of H-TriPy was selectively substituted, and its solubility with TFSI− anions in propylene carbonate (PC) reaches up to 200 mmol L−1, substantially exceeding that with Br− anions (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Redox behavior of H-TriPy-based EC organogels

Incorporating a 1,3,5-triazine core between pyridine units enables stable and reversible electron transfer by coupling two electroactive moieties and increasing redox centers, as each pyridine unit functions as an independent electron storage site. The all-in-one EC device was fabricated using EC organogels, composed of H-TriPy, ferrocene (Fc), F-IL, or 1-ethyl-3-octyl imidazolium bis(trifluoromethyl sulfonyl)imide (IL), and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), all dissolved in PC as the solvent (Supplementary Fig. 6). To understand the redox behavior of H-TriPy, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) were conducted, three reversible redox peaks were observed at −0.59 V/ − 0.86 V, −1.02 V/ − 1.318 V, and −1.59 V/ − 1.92 V, corresponding to single-electron reduction processes of H-TriPy3+/H-TriPy2+▪, H-TriPy2+▪/H-TriPy+▪▪, and H-TriPy+▪▪/H-TriPy0, respectively, demonstrate the multi-electron transfer properties of H-TriPy in the electrochemical process (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 7). Moreover, the redox processes of the H-TriPy were described in Eqs. 1–3.

a Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curve of the H-TriPy-based EC devices at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 (active area: 3.14 cm2). b UV-Vis-NIR transmittance spectra of H-TriPy-based EC devices under different voltages, measured with air as the baseline. Digital photographs were captured using regular and NIR cameras (700–1100 nm). Scale bars: 10 cm. c Time-dependent density-functional theory (TD-DFT) calculated absorption spectra of the non-stacked H-TriPy3+/H-TriPy3+ (grey line), π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ (blue line), and π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪ (red line). d Absorption spectra of H-TriPy-based EC devices under bright (grey line), cool (blue line), and dark modes (red line), measured with air as the baseline (active area: 3.14 cm2). e Calculated binding energy of the non-stacked H-TriPy3+/H-TriPy3+ (grey), π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ (blue), and π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪ (red). f Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) spectra of H-TriPy/NMP under bright (blue) and dark modes (red). The inset shows the corresponding 2D scattering patterns, with the upper image for bright mode and the lower image for dark mode.

Electrochromic performance of H-TriPy-based devices

To evaluate the EC behavior of the H-TriPy, UV-Vis-NIR transmittance spectra (380–2000 nm) of H-TriPy-based EC devices were measured under different voltages. With air as the calibration baseline, the EC device initially appears pale yellow due to the intrinsic coloration of H-TriPy and Fc, as confirmed by their CIE L*a*b* coordinates (Supplementary Fig. 8). At −0.8 V, the transmittance drops in the 800–1500 nm range, with transmittance differences (∆T) of 22.7%, 58.2%, and 55.4% at 642 nm, 854 nm, and 1012 nm, respectively, and an average transmittance of 18.1% across the 380–2000 nm range. This selective NIR modulation is attributed to the emergence of π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ formed upon the first reduction step, for thermal insulation while partially maintaining baseline illumination, reducing glare for visual comfort in spaces (Fig. 2b). When increased to −1.4 V, the EC device transitioned to a neutral-color, with ∆T of 60.5%, 66.2% and 63.3% at 642 nm, 854 nm, and 1012 nm, respectively, and an average transmittance of 1.6%, enabling deep shading for high-glare scenarios. The enhanced absorption across both visible and NIR ranges arises from forming more stable and strongly absorbing π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪. Beyond −1.4 V, further changes in the EC device were negligible, the maximum transmittance in the visible light region is only 3.7%, far lower than the reported literature (Supplementary Table 1). To eliminate the optical contributions from the background, a baseline was established using a device consisting of two ITO glasses sandwiching organogels without H-TriPy and Fc. The ΔT values at −0.8 V were 37.7%, 78.9%, and 79.3% at 642 nm, 854 nm, and 1012 nm, respectively. At −1.4 V, these values further increased to 74.4%, 89.7%, and 90.7%, with an average transmittance of 4.9% across the 380–2000 nm range, effectively minimizing indoor heat penetration and reducing energy consumption (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Increasing the concentration of H-TriPy in EC organogels can reduce the transmittance of EC devices in the colored state. However, excessively high concentrations compromise transparency in the initial state. To optimize optical contrast, the effect of different H-TriPy concentrations was evaluated at −1.4 V. Increasing the concentration gradually decreased visible light transmittance, but this effect plateaued beyond 50 mmol L−1 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Therefore, 50 mmol L−1 H-TriPy in EC organogels was chosen for subsequent experiments.

The color state of the EC device was characterized using the CIE 1976 L*a*b* color space. The values changed from [81.9, −1.9, 36.8] at 0 V (pale-yellow), to [67.4, 2.6, 54.0] at −0.8 V (orange-yellow), and ultimately to [1.28, −0.02, 2.2] at −1.4 V (neutral-color). This continuous change in color coordinates enables adaptive visual comfort under varying ambient light conditions. The significant L* reduction provides high optical contrast for glare suppression, while the near-zero a* and b* values reflect the neutralization of chromaticity (Supplementary Fig. 11). Meanwhile, the chroma (C*), a crucial parameter for color assessment within the CIE L*a*b* color space, was calculated using Equation S1. The C* value of the colored EC device was determined to be 2.2, further confirming its neutral-color state in the visible light range.

The high diffusion coefficient of the EC molecules and the ionic conductivity of the EC organogels ensure efficient ion migration, which is crucial for the switching speed of the EC device. The electrochemical kinetics of H-TriPy-based EC devices were analyzed using Equation S2, confirming that the redox process is diffusion-controlled (Supplementary Fig. 12). The diffusion coefficient of H-TriPy was calculated as 9.56 × 10−9 cm2 s−1, enabling fast ion migration and efficient switching. The high ionic conductivity of EC organogels further accelerates ion diffusion, ensuring rapid response. The ionic conductivities of H-TriPy organogels at different temperatures (−20 to 80 °C), calculated using Equation S3 as 0.23, 0.92, 1.63, 2.35, 3.10, and 3.49 mS cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 13). This broad temperature tolerance demonstrates the EC device’s adaptability to diverse environments. The switching speed and coloration efficiency (CE) of EC devices were also investigated (Supplementary Fig. 14). The EC devices demonstrated rapid coloration and bleaching times of 8.0 and 7.0 s, respectively, reaching 90% transmittance change at an 854 nm wavelength. The CE, which quantifies the change in optical density (ΔOD) per unit charge density during the coloration process, was determined to be 108 cm2 C−1 based on Equation S4.

The mechanism of NIR absorption enhancement in H-TriPy

As a redox-active EC molecule, H-TriPy possesses a heteroaromatic structure that promotes molecular planarity and facilitates π-electron delocalization, favoring π-stacking and enhancing NIR absorption42,43,44. To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the broadened NIR absorption of H-TriPy, DFT calculations were performed to investigate its light absorption characteristics during redox reactions (Supplementary Fig. 15), with the corresponding Cartesian coordinates provided (Supplementary Data 1). As shown in Fig. 2c, non-stacked H-TriPy3+/H-TriPy3+ exhibits a distinct absorption peak in the ultraviolet region, while no absorption peaks are observed in the visible and NIR ranges. In contrast, when H-TriPy3+ gains electrons, π-stacked H-TriPy dimers by “pancake bond”, such as H-TriPy2+▪ or H-TriPy+▪▪ are formed. Among these, π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ shows a weak absorption peak in the visible region along with a prominent absorption peak in the NIR region, whereas π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪ exhibits significant absorption peaks in both the visible and NIR ranges, which is consistent with the UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra of the H-TriPy-based EC device (Fig. 2d). Visible absorption typically arises from π-π* transitions of monomers, while NIR absorption is attributed to low-energy HOMO–LUMO transitions of π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ and H-TriPy+▪▪enabled by strong intermolecular orbital interactions (Supplementary Fig. 16)45,46,47,48,49.

The binding energy among non-stacked H-TriPy3+/H-TriPy3+, π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪, and π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪ was investigated using DFT calculations. As shown in Fig. 2e, the interaction between non-stacked H-TriPy3+/H-TriPy3+ is repulsive with a binding energy of +5.81 kcal mol−1, indicating that this molecular system remains stable in the absence of electron transfer. In contrast, π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ and H-TriPy+▪▪ exhibit strong attractive interactions due to the formation of a “pancake bond”, with binding energies of −11.60 and −34.12 kcal mol−1, respectively, resulting in the formation of stable π-stacked H-TriPy dimers. Further analysis reveals that the binding energy of π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪ is higher than that of π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪, suggesting that π-stacked H-TriPy2+▪ in the dark mode forms stronger bonds, making its reversible dissociation more difficult (Supplementary Table 2).

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy were conducted to investigate the dispersion of H-TriPy in solvents under both bright and dark conditions. As shown in Fig. 2f, the dark mode sample exhibits a more pronounced rise in the low-q region than the bright mode sample, indicating enhanced molecular aggregation after π-stacked H-TriPy dimer formation. Furthermore, FTIR spectroscopy revealed that the aromatic C = C stretching vibration mode at 1614 cm−1 is significantly intensified in the colored state relative to the bleached state, confirming that π-π stacking interactions between H-TriPy radicals are reinforced following the redox reaction, thereby supporting the formation of radical aggregates (Supplementary Fig. 17)50.

Long-term stability and scalability of H-TriPy-based EC devices

Achieving long-term stability is crucial for the commercial viability of EC windows, which are designed to operate reliably for 20–30 years, equivalent to approximately 100,000 cycles51. In cool and dark modes, H-TriPy undergoes π-stacking, forming stable free radicals that dimerize via a distinctive “pancake bond”, characterized by the overlap of delocalized π-electron systems52,53. While this bond broadens the absorption spectrum, it also hinders the regeneration of the colorless trivalent H-TriPy state, leading to incomplete bleaching and poor long-term cycling stability in EC devices (Fig. 3a)54,55. Additionally, at higher concentrations, π-stacked H-TriPy dimers are more prone to sustaining free radical states, further exacerbating the unstable issue of EC devices. To improve the long-term cycling stability of EC devices, a dynamic π-stacking strategy was developed using an F-IL to dissociate the “pancake bond” and inhibit π-stacked H-TriPy aggregation on the electrode surface (Fig. 3b). Specifically, the high electronegativity and bulky side chains of F-IL generate electrostatic interactions with π-stacked H-TriPy dimers and impose steric hindrance, thereby weakening π-π interactions, accelerating the dissociation of colored dimers during the bleaching process (Supplementary Fig. 18)27,56. This findings is confirmed by bleaching speed tests, in which the F-IL/H-TriPy bleaches approximately 2.1 times faster than the IL/H-TriPy, thus indicating that F-IL more effectively accelerates the dissociation of π-stacked H-TriPy dimers. (Supplementary Fig. 19).

a, b Cycling stability mechanism of H-TriPy-based EC devices with IL or F-IL. Blue and grey spheres represent H-TriPy, pink pentagons with grey chains represent IL, pink pentagons with red chains represent F-IL, blue ovals represent Fc, and grey lines represent PMMA. c Long-term cyclic test of H-TriPy-based EC devices with IL (blue) or F-IL (red) at a fixed switching voltage (−1.4/0 V, 15/20 s), measured with air as the baseline (active area: 3.14 cm2). d CV curves of the F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC devices obtained before (blue) and after cycling (red) with an active area of 3.14 cm2. e The binding energy of the π-stacked H-TriPy+▪▪ (blue) and F-IL/H-TriPy+▪▪ (red). f Long-term cyclic test for the F-IL/H-TriPy-based large-area (25 cm × 40 cm) EC devices at a fixed switching voltage (−1.4/0 V, 70/410 s), measured with air as the baseline. g Transmittance spectra of F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC devices post-aging tests conducted under ambient conditions for 180 d and at 60 °C for 60 d, respectively, measured with air as the baseline (active area: 3.14 cm2).

The impact of the dynamic π-stacking strategy was rigorously evaluated through time-transmittance tests, conducted at a fixed time interval (15/20 s) and switching voltage (−1.4/0 V), with 854 nm selected as the monitoring wavelength due to its sensitivity to the characteristic NIR absorption of π-stacked H-TriPy dimers. The results showed that F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC devices maintained an initial ∆T of 93.8% and 89.1% after 30,000 and 100,000 cycles, respectively (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 20). In contrast, IL/H-TriPy-based EC devices exhibited a significant decline, retaining only 39.3% of their ∆T after 30,000 cycles. The enhanced stability suggests that F-IL enables electrostatic interactions with H-TriPy, promoting reversible π-stacked H-TriPy dimers dissociation and thereby conferring a significant advantage in the long-term stability of all-in-one EC devices (Supplementary Table 3). Further stability evaluations were conducted via CV and chronoamperometry (CA) measurements before and after long-term cycling. The IL/H-TriPy-based EC device shows a decline in CV curve area and peak currents, reducing discoloration due to excessive H-TriPy accumulation at the electrode. In contrast, the F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC device maintains stable CV curves and prominent redox peaks, effectively preventing permanent coloration (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 21). Additionally, the transmittance spectra and CA curves for the F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC device remain stable after cycling (Supplementary Fig. 22).

The interactions between π-stacked H-TriPy dimers and H-TriPy radicals/F-IL were systematically investigated using DFT. Notably, the binding effect of π-stacked H-TriPy dimers was stronger than that observed in the presence of F-IL, attributed to the larger interaction area provided by the cross-arranged dimer configuration (Fig. 3e). This result demonstrates that F-IL effectively promotes the dissociation of π-stacked H-TriPy dimers in EC devices, consistent with the stability experimental results57.

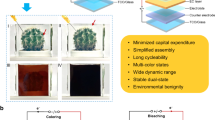

Scalability is critical for advancing EC windows from laboratory research to industrial applications, with long-term cyclic stability and switching speed as key performance indicators. Here, the switching speed, uniformity, and long-term cycling stability of large-area (25 cm × 40 cm) EC windows were further evaluated (Supplementary Movie 1). EC windows’ coloration and bleaching times were 28.5 and 222.5 s, respectively, achieving 90% transmittance change at 854 nm wavelength (Supplementary Fig. 23). The transmission spectra at distinct measurement points from the center to the edge exhibited nearly identical profiles, confirming the excellent optical uniformity of the EC window. The long-term cycling stability was evaluated by monitoring transmittance changes at 854 nm during fixed time intervals (70/410 s) and switching voltage (−1.4/0 V). As shown in Fig. 3f, after 4000 cycles, the EC window retained 91.4% of its initial ∆T. In addition, transmittance spectra of the EC window recorded before and after cycling revealed that the retention of ∆T at 642 nm and 1012 nm reached 93.1% and 94.7%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 24). These results demonstrate that the device maintains excellent optical stability while expanding its size, providing solid technical support for its commercial application.

The durability of the EC windows under harsh environmental conditions and aging was further investigated to evaluate their reliability. As shown in Fig. 3g, the EC device retained 95.7% of its initial ∆T after 180 days of natural aging, demonstrating the remarkable chemical stability of the EC organogels. To evaluate cycling stability under thermal conditions, the F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC devices were continuously switched 1000 cycles at 60 °C, maintained 87.8%, 92.2%, and 92.6% of their optical modulation at 642, 854, and 1012 nm, respectively, indicating robust switching performance under thermal conditions (Supplementary Fig. 25). Separately, to assess long-term thermal storage stability, the EC devices stored statically at 60 °C preserved 92.7% of their ∆T after 60 d. Furthermore, F-IL/H-TriPy-based EC devices maintain operation under cold conditions, attributed to the high ionic conductivity of the EC organogels at low temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 26). These results confirm the robust aging resistance and wide-range functionality of the EC devices, highlighting their strong commercial viability across diverse environmental conditions.

Thermal modulation of H-TriPy-based EC windows

All-in-one EC devices, distinguished by their simple structure and scalable fabrication process, enable the fabrication of large-area EC windows. With increasing applied voltage, EC windows (40 cm × 60 cm) transition sequentially from the bright mode to the cool mode and finally to the dark mode, effectively blocking both visible and NIR light, thereby improving energy efficiency (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 27). Furthermore, the solar irradiance, derived from the transmittance spectra and presented in Fig. 4b, demonstrates substantial optical modulation across the entire visible and NIR range.

a Schematic illustrations (top) of the large-area (40 × 60 cm) EC window under bright, cool, and dark modes showing visible (blue arrows) and NIR (red arrows) light regulation, and corresponding digital photographs (bottom) captured with an NIR camera (700–1100 nm). Scale bar: 30 cm. b Solar irradiance spectra converted from the measured transmittance spectra of the EC devices. c Real-time thermal photographs of the EC window during xenon lamp illumination under bright (top), cool (middle), and dark (bottom) modes. Scale bar: 5 cm. d Indoor temperature variations in a home-made cabin model exposed to xenon lamp illumination under bright (red), cool (blue), and dark (grey) modes. e Simulated energy consumption of a full-scale building model in various cities, including Honolulu, Cairo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Melbourne, Barcelona, Singapore, and Phoenix using Low-e glass (blue) and EC window (red). f Simulated quarterly energy consumption in Shanghai using Low-e glass (blue) and EC window (red).

The thermal and optical modulation capabilities of the EC windows were assessed using a custom-built setup, which comprised a black rubber plate (5 cm × 5 cm × 1 cm) as the blackbody absorber, a xenon lamp as the light source, and an infrared (IR) camera for real-time temperature monitoring (Supplementary Fig. 28). After 80 s of illumination, the backside blackbody temperature of the EC windows in the cool and dark modes decreased significantly to 35.3 °C and 27.6 °C, respectively, compared to over 50.4 °C in the bright mode (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, temperature data from a home-made cabin model were also collected, where a xenon lamp provided 1-sun illumination to simulate sunlight, while a chamber measuring 40 cm (length) × 30 cm (width) × 25 cm (height) served as the test environment. An EC device was integrated as the chamber window, and the indoor temperature was monitored using a thermocouple, while the external temperature was maintained at approximately 20 °C (Supplementary Fig. 29). After 25 min of continuous irradiation, the indoor temperature increased by 11.7 °C, 6.7 °C, and 3.1 °C under the bright, cool, and dark modes, respectively, demonstrating the EC window’s capability for effective thermal and optical modulation. (Fig. 4d).

To further assess the energy-saving potential, a building energy simulation was conducted using EnergyPlus software. A full-scale building model was developed to represent a typical 12-story office building with floor dimensions of 73 m (length) × 49 m (width) × 4 m (height) and a total window glass area of 4636 m2 (Supplementary Fig. 30 and Table 4). The EC window operates based on temperature-triggered control: at glass temperatures above 30 °C, −0.8 V is applied to activate the cool mode, while exceeding 40 °C triggers the dark mode at −1.4 V, adjusting transmittance and thermal conductivity accordingly.

As shown in Fig. 4e, the energy-saving performance of the EC window, consisting of a composite film between two glass layers, was compared with that of low-emissivity (low-e) glass across eight representative cities worldwide (Supplementary Fig. 31). The results show that EC windows consistently achieved higher annual energy savings than low-e glass in all analyzed cities, with an average saving of 45.7 MJ m−2. In Shanghai, energy consumption decreased in all four quarters, with the highest savings of 11.5 MJ m−2 observed in the third quarter (Fig. 4f). The H-TriPy-based EC window exhibits superior light and thermal modulation capabilities, effectively regulating temperature and enhancing energy efficiency. This makes it a promising candidate for energy-efficient buildings, contributing to decarbonization and environmental sustainability.

Discussion

In summary, we demonstrate that a heteroaromatic tri-pyridine molecule with a 1,3,5-triazine core enhances molecular conjugation. Leveraging high-density π-stacking facilitated via a distinctive “pancake bond”, H-TriPy exhibits highly augmented NIR absorption, thereby overcoming the limitations of conventional EC molecules in NIR modulation. Moreover, the three pyridine-based redox centers contribute to diverse electronic structures, enabling distinct bright, cool, and dark EC states for adaptive visual comfort. Incorporating F-ILs into EC organogels effectively dissociates the “pancake bond”, suppressing the formation of H-TriPy dimers at high concentrations. This strategy significantly enhances EC device durability, achieving near-zero transmittance (as low as 3.7%) across visible and NIR regions (380–2000 nm) while maintaining over 89.1% performance retention beyond 100,000 cycles. Furthermore, large-area EC windows exhibit uniform coloration, demonstrating their scalability for practical applications. Simulations indicate that H-TriPy-based EC windows show higher efficiency than commercial low-e glass in energy efficiency, offering a promising avenue for energy-saving window designs that contribute to global carbon neutrality and sustainability.

Methods

Materials

All the starting materials were commercially available and used as received. 1-Ethylimidazole (98%), 1-bromooctane (99%), 1-bromobutane ( > 99%), and ferrocene (Fc, 99%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. 1,1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6-tridecafluoro-8-iodooctane ( ≥ 97%), 2,4,6-tri-4-pyridinyl-1,3,5-triazine ( ≥ 97%), 4, 4′-bipyridine ( ≥ 98%), N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, ≥99.5%), and lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonamide (LiTFSI, ≥99%) were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. 1, 2-Propanediol carbonate (PC, 99.7%) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co., Ltd. Ethyl ether (Et2O, ≥99.7%) and toluene ( ≥ 99.5%) were purchased from the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., ltd. ITO glass (approximately 10 Ω sq−1) was purchased from Zhuhai Kaivo Optoelectronic Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of 2,4,6-tri(pyridyl-4-butyl)-1,3,5-triazine bromide (H-TriPy[Br]) (1)

2,4,6-tri-4-pyridinyl-1,3,5-triazine (15.6 g, 50 mmol) and 1-bromobutane (30.8 g, 225 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (500 mL) and refluxed at 100 °C for 48 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, then filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was subsequently purified via recrystallization from an excess of Et2O and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 24 h, yielding a brownish powder. Yield: 29.8 g (83%).

Synthesis of 2,4,6-tri(pyridyl-4-butyl)-1,3,5-triazine bis(trifluoromethyl sulfonyl)imide (H-TriPy[TFSI]) (2)

Compound 1 (36.0 g, 50 mmol) was dissolved in deionized water (250 mL), followed by the dropwise addition of a solution containing an excess of LiTFSI (17.2 g, 60 mmol). The precipitate was washed thoroughly with deionized water five times, yielding a reddish-brown powder. Yield: 58.2 g (88%).

Synthesis of 1-ethyl-3-octyl imidazolium bromide (IL[Br]) and 1-ethyl-3-tridecafluorooctyl imidazolium iodine (F-IL[I]) (3, 4)

1-Ethylimidazole (4.8 g, 50 mmol) and the corresponding bromide (75 mmol) (IL[Br] for 1-bromooctane (14.5 g), F-IL[I] for 1,1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6-tridecafluoro-8-iodooctane (35.5 g)) were dissolved in toluene (500 mL) and refluxed at 70 °C for 24 h under N2 protection. After the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and washed multiple times with fresh toluene to collect the oily product. Subsequently, the product was purified by recrystallization from a large amount of Et2O and dried in a 60 °C vacuum oven for 24 h. Yield: 9.2 g (88%) for IL[Br]; 17.5 g (79%) for F-IL[I].

Synthesis of 1-ethyl-3-octyl imidazolium bis(trifluoromethyl sulfonyl)imide (IL[TFSI]) and 1-ethyl-3-tridecafluorooctyl imidazolium bis(trifluoromethyl sulfonyl)imide (F-IL[TFSI]) (5, 6)

Compound 3 (21.0 g, 100 mmol) or Compound 4 (44.4 g, 100 mmol) was dissolved in DI water (500 mL), followed by the dropwise addition of a solution containing an excess of LiTFSI (34.5 g, 120 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 12 h to ensure complete anion exchange. The resulting oily product was washed thoroughly with deionized water several times to yield the final product. Yield: 43.6 g (89%) for IL[TFSI]; 59.4 g (82%) for F-IL[TFSI].

Preparation of the H-TriPy-based EC organogels

To prepare the H-TriPy-based EC organogels, 50 mmol L−1 H-TriPy and 150 mmol L−1 Fc were added to a mixed solution of PMMA, IL or F-IL, and PC (with a mass ratio of 1:1:10). The mixture was stirred for 12 h and then heated at 70 °C for 2 h, allowed for complete dissolution and thorough mixing.

Fabrication of the H-TriPy-based EC devices

The H-TriPy-based EC organogels were fixed between two pieces of ITO glass with the thickness controlled to 0.2 mm using double-sided tape, and the edges were sealed with UV-curing adhesive. Unless otherwise specified, the effective area of the EC device was maintained at 3.14 cm2 by punching the double-sided tape with a circular mold (diameter=2.0 cm). The conductive copper foil was applied around the edges for large-area EC devices to ensure a uniform electric field, thus enhancing the EC performance and minimizing field irregularities.

Characterization

The 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were acquired using an NMR spectrometer (Avance III HD 600 MHz, Bruker, Germany). Optical properties were assessed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (U-T6PC, Yi Pu, China), a UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (UH5700, Hitachi, Japan), and a fiber-optic UV-Vis spectrometer (PG2000-Pro-Ex, Ideaoptics, China). Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements were performed on a SAXS system (SAXSess mc2, Anton Paar, Austria). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained in transmission mode using a spectrometer (Nicolet 8700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory, covering the range of 400–4000 cm−1. A xenon lamp (300 W, Perfectlight, China) with AM1.5 filters was used as the light source. Indoor temperature regulation in the cabin model was measured using a thermocouple thermometer (TA612C, TASI, China). The CIE L*a*b* color coordinates were obtained using a spectrophotometer (CS-820N, CHN Spec, China). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), cyclic voltammetry (CV), and chronoamperometry (CA) were conducted using an electrochemical workstation (VSP-300, Biologic SAS, France). Long-term cyclic tests of the EC devices were performed using a cycle tester (KV-EC-7500, Kaivo, China). Thermal photographs of EC devices were acquired using an infrared camera (A300-Series, FLIR, USA) with a 25 μm infrared lens (T197145, FLIR, USA).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper, and Cartesian coordinates for both the input and optimized geometries used in DFT calculations are included in the Supplementary Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235–239 (2015).

Peng, Y. et al. Nanoporous polyethylene microfibres for large-scale radiative cooling fabric. Nat. Sustain. 1, 105–112 (2018).

Zhao, L., Lee, X., Smith, R. B. & Oleson, K. Strong contributions of local background climate to urban heat islands. Nature 511, 216–219 (2014).

Khandelwal, H., Schenning, A. P. H. J. & Debije, M. G. Infrared regulating smart window based on organic materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1602209 (2017).

Tang, K. et al. Temperature-adaptive radiative coating for all-season household thermal regulation. Science 374, 1504–1509 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Scalable thermochromic smart windows with passive radiative cooling regulation. Science 374, 1501–1504 (2021).

Deb, S. K. A novel electrophotographic system. Appl. Opt. 8, 192 (1969).

Azens, A. & Granqvist, C. Electrochromic smart windows: energy efficiency and device aspects. J. Solid State Electrochem. 7, 64–68 (2003).

Yu, F. et al. Electrochromic two-dimensional covalent organic framework with a reversible dark-to-transparent switch. Nat. Commun. 11, 5534 (2020).

Sheng, S.-Z. et al. Nanowire-based smart windows combining electro- and thermochromics for dynamic regulation of solar radiation. Nat. Commun. 14, 3231 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Flexible and high-performance electrochromic devices enabled by self-assembled 2D TiO2/MXene heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 12, 1587 (2021).

Llordés, A. et al. Linear topology in amorphous metal oxide electrochromic networks obtained via low-temperature solution processing. Nat. Mater. 15, 1267–1273 (2016).

Jia, Z. et al. Electrochromic windows with fast response and wide dynamic range for visible-light modulation without traditional electrodes. Nat. Commun. 15, 6110 (2024).

Shao, Z. et al. Tri-band electrochromic smart window for energy savings in buildings. Nat. Sustain. 7, 796–803 (2024).

Beaujuge, P. M., Ellinger, S. & Reynolds, J. R. The donor–acceptor approach allows a black-to-transmissive switching polymeric electrochrome. Nat. Mater. 7, 795–799 (2008).

Ke, Z. et al. Highly conductive and solution-processable n-doped transparent organic conductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3706–3715 (2023).

Bai, Z. et al. Divalent viologen cation-based ionogels facilitate reversible intercalation of anions in PProDOT-Me2 for flexible electrochromic displays. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312587 (2024).

Christiansen, D. T., Tomlinson, A. L. & Reynolds, J. R. New design paradigm for color control in anodically coloring electrochromic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3859–3862 (2019).

Chen, D. et al. High-performance black copolymers enabling full spectrum control in electrochromic devices. Nat. Commun. 15, 8457 (2024).

Ling, H., Wu, J., Su, F., Tian, Y. & Liu, Y. J. Automatic light-adjusting electrochromic device powered by perovskite solar cell. Nat. Commun. 12, 1010 (2021).

Deng, B. et al. An ultrafast, energy-efficient electrochromic and thermochromic device for smart windows. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302685 (2023).

Kortz, C., Hein, A., Ciobanu, M., Walder, L. & Oesterschulze, E. Complementary hybrid electrodes for high contrast electrochromic devices with fast response. Nat. Commun. 10, 4874 (2019).

Zhuang, Y. et al. Soluble triarylamine functionalized symmetric viologen for all-solid-state electrochromic supercapacitors. Sci. China Chem. 63, 1632–1644 (2020).

Laschuk, N. O., Ebralidze, I. I. & Zenkina, O. V. Polypyridine-based architectures for smart electrochromic and energy storage materials. Can. J. Chem. 101, 400–417 (2023).

Laschuk, N. O., Ebralidze, I. I., Easton, E. B. & Zenkina, O. V. Post-synthetic color tuning of the ultra-effective and highly stable surface-confined electrochromic monolayer: Shades of green for camouflage materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 39573–39583 (2021).

Kim, J. & Myoung, J. Flexible and transparent electrochromic displays with simultaneously implementable subpixelated ion gel-based viologens by multiple patterning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1808911 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Synergistic interaction of dual-polymer networks containing viologens-anchored poly(ionic liquid)s enabling long-life and large-area electrochromic organogels. Small 19, 2301742 (2023).

Striepe, L. & Baumgartner, T. Viologens and their application as functional materials. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 16924–16940 (2017).

Ghosh, S., Li, X., Stepanenko, V. & Würthner, F. Control of H- and J-type π stacking by peripheral alkyl chains and self-sorting phenomena in perylene bisimide homo- and heteroaggregates. Chem. Eur. J. 14, 11343–11357 (2008).

Yu, X. et al. Colorless-to-black electrochromism from binary electrochromes toward multifunctional displays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 39505–39514 (2020).

Pande, G. K., Kim, D. Y., Sun, F., Pal, R. & Park, J. S. Photocurable allyl viologens exhibiting RGB-to-black electrochromic switching for versatile heat-shielding capability. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 263, 112579 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Tough and stretchable ionogels by in situ phase separation. Nat. Mater. 21, 359–365 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. A transparent, highly stretchable, solvent-resistant, recyclable multifunctional ionogel with underwater self-healing and adhesion for reliable strain sensors. Adv. Mater. 33, 2105306 (2021).

Sun, H. et al. A safe and non-flammable sodium metal battery based on an ionic liquid electrolyte. Nat. Commun. 10, 3302 (2019).

Tang, Q. et al. 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate-doped high ionic conductivity gel electrolytes with reduced anodic reaction potentials for electrochromic devices. Mater. Des. 118, 279–285 (2017).

Lu, W. et al. Use of ionic liquids for π-conjugated polymer electrochemical devices. Science 297, 983–987 (2002).

Wen, R.-T., Granqvist, C. G. & Niklasson, G. A. Eliminating degradation and uncovering ion-trapping dynamics in electrochromic WO3 thin films. Nat. Mater. 14, 996–1001 (2015).

Huang, Z.-J. et al. Electrochromic materials based on tetra-substituted viologen analogues with broad absorption and good cycling stability. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 223, 110968 (2021).

Wu, N., Ma, L., Zhao, S. & Xiao, D. Novel triazine-centered viologen analogues for dual-band electrochromic devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 195, 114–121 (2019).

Cojocariu, I. et al. Extended π-conjugation: a key to magnetic anisotropy preservation in highly reactive porphyrins. J. Mater. Chem. C. 11, 15521–15530 (2023).

Ren, H.-S., Li, Y.-K., Zhu, Q., Zhu, J. & Li, X.-Y. Spectral shifts of the n → π* and π → π* transitions of uracil based on a modified form of solvent reorganization energy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 13284 (2012).

Tang, G. et al. Propylene-bridged associative bis(bipyridinium) electrolytes for long-lifetime aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202501458 (2025).

Jacquot de Rouville, H.-P. et al. Viridium: a stable radical and its π-dimerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 1823–1830 (2025).

Groslambert, G. et al. π-Expansion as gateway to viologen-based pimers. Chem. Sci. 16, 9320–9325 (2025).

Small, D. et al. Intermolecular π-to-π bonding between stacked aromatic dyads. Experimental and theoretical binding energies and near-IR optical transitions for phenalenyl radical/radical versus radical/cation dimerizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13850–13858 (2004).

Lü, J.-M., Rosokha, S. V. & Kochi, J. K. Stable (long-bonded) dimers via the quantitative self-association of different cationic, anionic, and uncharged π-radicals: structures, energetics, and optical transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 12161–12171 (2003).

Juneau, A. & Frenette, M. Exploring curious covalent bonding: Raman identification and thermodynamics of perpendicular and parallel pancake bonding (pimers) of ethyl viologen radical cation dimers. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 10805–10812 (2021).

Cheng, C. et al. Influence of constitution and charge on radical pairing interactions in tris-radical tricationic complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8288–8300 (2016).

Otaegui, J. R. et al. Enhanced electrochromic smart windows based on supramolecular viologen tweezers. Chem. Mater. 37, 2220–2229 (2025).

Whiteoak, C. J., Salassa, G. & Kleij, A. W. Recent advances with π-conjugated salen systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 622–631 (2012).

Nagai, J., McMeeking, G. D. & Saitoh, Y. Durability of electrochromic glazing. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 56, 309–319 (1999).

Geraskina, M. R., Dutton, A. S., Juetten, M. J., Wood, S. A. & Winter, A. H. The viologen cation radical pimer: a case of dispersion-driven bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 9435–9439 (2017).

Nikumbe, D. Y. et al. Stability of monoradical cation dimer of viologen derivatives in aqueous redox flow battery. J. Appl. Electrochem. 54, 2165–2177 (2024).

Xiang, Z., Li, W., Wan, K., Fu, Z. & Liang, Z. Aggregation of electrochemically active conjugated organic molecules and its impact on aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214601 (2023).

Yu, H.-F., Li, C.-T. & Ho, K.-C. Stable viologen-based electrochromic devices: Control of Coulombic interaction using multi-functional polymeric ionic liquid membranes. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 250, 112072 (2023).

Lin, W.-Y., Silori, G. K., Yu, H.-F. & Ho, K.-C. Regulating ion dynamics through poly ionic liquid for high-performance alkyl viologen-based electrochromic devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 289, 113676 (2025).

Xiang, Z. et al. Manipulating aggregate electrochemistry for high-performance organic redox flow batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202416184 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52473168, K.R.L.; 52131303, H.Z.W.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2232025G-07, K.R.L.), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (23ZR1400400, C.Y.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L.W. conceived the idea and designed the methodology. X.L.W., B.W.B., Z.Y.B. and Q.C.F. conducted the investigation. C.Y.H., Q.H.Z., and Y.G.L. performed the formal analysis. X.L.W. carried out the data visualization. W.Z.J., K.R.L. and H.Z.W. supervised the project. X.L.W. wrote the original draft, while X.L.W., C.Y.H., Q.H.Z., Y.G.L., W.Z.J., K.R.L. and H.Z.W. contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Santra Dines, Aimee Tomlinson, and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Bao, B., Bai, Z. et al. Heteroaromatic π-stacking engineered near-infrared absorption for highly stable near-zero transmittance electrochromic window. Nat Commun 16, 9964 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64955-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64955-1