Abstract

Existing RNA language models (RLMs) largely overlook structural information in RNA sequences, leading to incomplete feature extraction and suboptimal performance on downstream tasks. In this study, we present ERNIE-RNA (Enhanced Representations with Base-Pairing Restriction for RNA Modeling), an RNA pre-trained language model based on a modified BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers). Notably, ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps exhibit superior ability to capture RNA structural features through zero-shot prediction, outperforming conventional methods like RNAfold and RNAstructure, suggesting that ERNIE-RNA naturally develops comprehensive representations of RNA architecture during pre-training. Moreover, after fine-tuning, ERNIE-RNA achieves state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance across various downstream tasks, including RNA structure and function predictions. In summary, ERNIE-RNA provides versatile features that can be effectively applied to a wide range of research tasks. Our findings highlight that integrating key knowledge-based priors into the BERT framework may enhance the performance of other language models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ribonucleic acids (RNAs) are versatile macromolecules that not only serve as carriers of genetic information, but also act as essential regulators and structural components influencing numerous biological processes1,2. RNA can be categorized into two main types: protein-coding RNA and non-coding RNA (ncRNA)3,4. Protein-coding RNA primarily refers to messenger RNA (mRNA)5, which mainly functions by encoding genetic information through codons. ncRNA does not encode proteins; instead, it regulates gene expression. ncRNA includes microRNA (miRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), among others. Short miRNAs govern the post-transcriptional gene regulation, while longer lncRNAs contribute to various cellular activities, from chromatin remodeling to epigenetic control.

RNA molecules exhibit a hierarchical organization where their primary sequences fold into specific structural conformations that ultimately determine their biological functions6,7. Understanding the structure of RNA is crucial for enhancing our overall knowledge of cellular biology and developing RNA-based therapeutics. Traditional experimental methods including nuclear magnetic resonance8, X-ray crystallography9, cryogenic electron microscopy10, and icSHAPE (in vivo RNA secondary structure profiles)11 have been developed to study the structure and function of RNA. However, these approaches are expensive and time-consuming, which has motivated the development of computational methods for RNA structure and function prediction. These computational approaches can be broadly categorized into three classes: thermodynamics-based12,13,14,15,16,17,18, alignment-based19,20, and deep learning-based21,22,23,24,25. Despite their promise, each computational approach faces distinct challenges. Thermodynamics-based methods are constrained by the accuracy of their underlying thermodynamic parameters. Alignment-based methods show limited effectiveness when handling RNA sequences that lack sufficient homologous sequences for multiple sequence alignment. While deep learning-based models have demonstrated improved prediction accuracy on various benchmark datasets, they often struggle with generalization, showing much lower performance when confronted with previously unseen RNA families.

The advancements in high-throughput sequencing technology26 have produced a wealth of unlabeled data, which contain rich information about RNA structures and functions. To leverage these vast datasets, many BERT-style27 RNA language models have emerged. Initial efforts focused on general-purpose RNA modeling: RNA-FM28, trained on 23 million unannotated RNA sequences, pioneered applications in both structural and functional predictions; UNI-RNA29 and RiNALMo30 further scaled up this approach to 400 M and 650 M parameters respectively, with RiNALMo trained on 36 M sequences showing notable generalization capability, and UNI-RNA utilizing an unprecedented 1 billion RNA sequences. Other general-purpose models explored different strategies: RNABERT31 incorporated Structure Alignment Learning during pre-training, while RNA-MSM32 leveraged evolutionary information through multiple sequence alignment. Meanwhile, RNAErnie33 enhanced performance through innovative motif-aware pretraining and type-guided fine-tuning strategies. Several mRNA-focused language models have also been developed with different specializations. UTR-LM34 was trained specifically on mRNA untranslated regions, while CaLM35 and CodonBERT36 were pre-trained on complementary DNA (cDNA) and mRNA coding sequences respectively, with applications in protein engineering and various coding sequence predictions. However, these specialized models, due to their narrow focus on specific mRNA regions or features, demonstrate limited capability in understanding the broader semantic patterns across diverse RNA types and functions.

Understanding RNA structure is pivotal for elucidating its functional roles, but existing pre-trained RNA language models fail to adequately incorporate structural information. The self-attention mechanism37 in transformer-based models offers a potential solution by assigning varying levels of importance to different parts of the input sequence, and attention maps can visually represent these importance weights, illustrating how the model attends to different sequence positions. While this attention mechanism has shown promise in capturing long-range dependencies in sequences, current general-purpose RNA language models like RNA-FM and UNI-RNA, which rely on standard attention mechanisms and are trained solely on one-dimensional sequences, struggle to effectively extract structural and functional features. This limitation is evidenced by their embeddings being inferior to simple one-hot encoding in certain tasks38. Although UTR-LM attempts to address this challenge by incorporating predicted secondary structures from RNAfold during pre-training, it faces significant drawbacks: compared to experimental data, the predicted structures often contain errors, and using specific structure prediction tools as prior knowledge limits the model’s generalization ability across diverse RNA families. These limitations suggest that BERT-based models, originally designed for text feature extraction, need a more principled approach to capture RNA structural features. Given that RNA structure and function are intrinsically linked through specific biological mechanisms, developing an innovative attention mechanism that can learn generalizable structural patterns directly from sequence data presents a promising direction for improving RNA language models.

Building upon the transformative potential of self-attention mechanisms, as exemplified by AlphaFold239 and Uni-Mol40 we posit that a similar paradigm shift can be achieved in RNA modeling. AlphaFold2 demonstrated the power of incorporating evolutionary and structural information to guide the iterative refinement of protein structures, while Uni-Mol leveraged atom-coordinate-based pair-wise interactions to enhance molecular representations. Drawing inspiration from these advancements, we hypothesized that integrating crucial RNA-specific structural information into the self-attention framework could facilitate the extraction of comprehensive and nuanced RNA features. The inherent base-pairing interactions that dictate RNA folding present a unique opportunity to inform the model with biologically relevant priors.

To this end, we introduce ERNIE-RNA (Enhanced Representations with Base-pairing Restriction for RNA Modeling), an innovative pre-trained RNA language model founded upon a modified BERT architecture. ERNIE-RNA distinguishes itself by incorporating a base-pairing-informed attention bias during the calculation of attention scores. This innovative approach augments the model’s capacity to characterize RNA structure and enables a more holistic extraction of RNA features. Notably, even in the absence of fine-tuning, ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps exhibit a noteworthy ability to discern RNA structural features in a zero-shot setting, attaining an F1-score of up to 0.55. Subsequent fine-tuning across a diverse array of downstream tasks pertaining to RNA structure and function further demonstrates ERNIE-RNA’s capabilities, achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance across most evaluated benchmarks. These results strongly suggest that ERNIE-RNA captures a comprehensive representation of RNA structural and functional information, thereby establishing its potential as a powerful tool for advancing RNA research.

Results

The architecture and pre-training of ERNIE-RNA

To address the limitations of traditional RNA language models, we developed ERNIE-RNA based on the BERT architecture. The model consists of 12 transformer blocks, each employing a multi-head attention mechanism with 12 parallel ‘attention heads’ that allow the model to jointly attend to information from different representational subspaces at different positions. Specifically, for each attention mechanism, the 768-dimensional token embedding is projected and split into 12 sub-vectors (64 dimensions each), one for each head. Each head then independently computes its own attention scores over the sequence. The outputs from all 12 heads are concatenated and passed through a final linear layer, enabling the model to capture a rich set of token-to-token relationships in parallel. Overall, this architecture results in a model with ~86 million parameters (Fig. 1a). While existing approaches like UTR-LM incorporate predicted RNA secondary structures from algorithms such as RNAfold during pre-training, we introduced an all-against-all attention bias mechanism that provides the model with comprehensive prior knowledge about potential base-pairing configurations. This innovative approach enables the model to learn RNA structural patterns through self-supervised learning rather than relying on potentially biased structural predictions. By avoiding the incorporation of imperfect structural annotations during pre-training, which could adversely affect model generalization, our method allows ERNIE-RNA to discover more flexible and generalizable structural representations directly from sequence data. In our implementation, we compute a pair-wise position matrix from one-dimensional RNA sequences to replace the bias term in the first transformer layer. From the second layer onward, the bias of each layer is determined by the attention map of its preceding layer. In the pair-wise matrix calculation, for any base pair (i,j) in a sequence of length L, we assign values based on canonical base-pairing rules: 2 for AU pairs, 3 for CG pairs, and a tunable hyperparameter α (initially, 0.8) for GU pairs, with diagonal elements set to 0.

ERNIE-RNA incorporates RNA structural information into the self-attention mechanism. a In the pre-training stage, ERNIE-RNA, consisting of 12 transformer layers, was pre-trained with 20.4 million non-coding RNA sequences from RNAcentral via self-supervised learning. b In the fine-tuning stage, ERNIE-RNA provides attention maps and token embeddings that encode rich structural and semantic RNA features, achieving state-of-the-art performance on diverse downstream tasks spanning structure prediction and functional annotation.

We initially collected 34 million RNA sequences from the RNAcentral database. After filtering sequences longer than 1022 nucleotides, performing vocabulary refinement, and applying redundancy removal using CD-HIT-EST at a 100% similarity threshold, we retained 20.4 million sequences for pre-training. Analysis of this dataset revealed a substantial proportion of rRNA and tRNA sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1b). To systematically investigate the impact of data composition on model performance, we constructed several training datasets with different characteristics (Supplementary Table 1). These include: (1) a baseline dataset containing all sequences under 1022nt after initial filtering, (2) a dataset excluding rRNA and tRNA sequences to eliminate potential bias from these well-structured RNA families, (3) a balanced dataset retaining only 20% of rRNA and tRNA sequences to prevent their overrepresentation while maintaining diversity, and (4) a dataset excluding lncRNA sequences to evaluate the impact of these structurally flexible RNAs on model training. Additionally, we created subsets of varying sizes from the baseline dataset for scaling analysis (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2).

Our pre-training experiments yielded several crucial insights into the learning process (Supplementary Fig. 2). The model’s perplexity on the masked language modeling task exhibited consistent improvement with increasing training data size, specifically from 86 million tokens to 8 billion tokens. This trend, coupled with the zero-shot RNA secondary structure prediction results (discussed in the subsequent section), suggested that our chosen dataset size of 8 billion tokens provides a good balance between computational efficiency and model performance. Notably, the exclusion of rRNA/tRNA sequences or lncRNAs exerted minimal influence on model perplexity (Supplementary Table 3), signifying that ERNIE-RNA can effectively learn RNA sequence patterns irrespective of specific RNA family biases within the training data.

Through this comprehensive pre-training approach, ERNIE-RNA learned to encode both local and global RNA features in its attention maps (L×L×156) and token embeddings (12×768×L) (Fig. 1b). The model’s architecture and training strategy enable it to capture complex RNA characteristics without requiring explicit structural annotations during pre-training, making it broadly applicable across diverse RNA families and structural motifs.

ERNIE-RNA learns functional and structural information through pre-training

ERNIE-RNA employs multiple attention heads with an all-against-all pair-wise attention bias mechanism to simultaneously extract diverse information from input sequences. This architectural design provides prior knowledge about potential base-pairing configurations, which we hypothesized would guide the attention maps to better capture structural features.

To assess the model’s structural understanding capabilities, we conducted zero-shot RNA secondary structure prediction experiments using the bpRNA-1m benchmark dataset41. Without any fine-tuning, we directly interpreted ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps as base-pairing probability matrices for RNA secondary structure prediction. Surprisingly, we discovered that the introduction of our pair-wise attention bias enabled ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps to exhibit emergent capabilities in capturing RNA structural information without explicit structural supervision during pre-training (Fig. 2). Our evaluation reveals that the zero-shot performance of ERNIE-RNA, by directly interpreting its attention maps, is highly effective. As shown in Table 1, it achieves a median F1-score of 0.552 on the bpRNA-1m test set. This result not only surpasses traditional thermodynamic methods like RNAfold42 (F1-score 0.492) and RNAstructure43 (0.491), but also significantly outperforms other large language models such as RNAErnie (0.440) and RNA-BERT (0.365), even though these models were evaluated after fine-tuning on the same task32,33. Notably, we observed enhanced structural information capture in attention maps from deeper layers, suggesting the model’s architecture enables effective propagation and refinement of structural features through successive transformer layers.

Heatmap showing the binary F1-scores of attention maps from different layers and heads of the ERNIE-RNA-L12 model (86 M parameters, 12 attention heads, 12 transformer layers) on the bpRNA-1m test set without any fine-tuning. Higher F1-scores (darker colors) indicate better capture of RNA structural information, with the highest score of 0.55 observed in the later layers.

To investigate whether the presence of attention maps capturing RNA structural information is a coincidence, we conducted comprehensive analyses across multiple model initializations and architectures. We pre-trained four independent ERNIE-RNA models (25 million parameters each) with different random initializations. Zero-shot experiments consistently demonstrated activated attention heads capable of capturing RNA structural information, though the specific heads varied across models (Supplementary Fig. 3). This variability reflects the stochastic nature of neural network training, where different attention heads may specialize in capturing structural features in different model instances. In contrast, control experiments with a model lacking pair-wise position bias (Supplementary Fig. 4a) or using random parameters without pre-training (Supplementary Fig. 4b) showed no activated attention heads. Similarly, when testing RNA-FM under identical conditions, none of its attention maps demonstrated the capability to capture structural features (Supplementary Fig. 5), further confirming that the introduction of all-against-all pair-wise attention bias is crucial for enabling the emergence of structural feature extraction capabilities.

The model’s ability to capture complex structural motifs was further evaluated using RNA sequences containing pseudoknots44—non-canonical secondary structures characterized by base pairings between loop regions and external nucleotides. These structures are particularly challenging for traditional algorithms based on thermodynamics and dynamic programming, such as Mfold45, which often omit pseudoknot prediction due to computational complexity constraints46. Comparison of zero-shot prediction performance across different datasets (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 6) demonstrates that ERNIE-RNA achieves comparable or superior performance to traditional methods like RNAfold on the bpRNA-1m test set, and significantly outperforms RNA-FM on challenging structure prediction datasets such as RIVAS TestSetB47.

a Scatter plot comparing per-sample binary F1-scores between zero-shot ERNIE-RNA and RNAfold on the bpRNA-1m test set. Each point represents an individual RNA sequence, with points above the diagonal indicating superior performance by ERNIE-RNA. The results demonstrate that ERNIE-RNA achieves comparable or better performance than conventional methods without any fine-tuning. b Comparison of zero-shot prediction performance between ERNIE-RNA and RNA-FM on the RIVAS TestSetB dataset. c Visualization of ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps capturing pseudoknot structures in two representative RNA sequences. Colored boxes highlight the base-pairing interactions forming pseudoknot structures, with corresponding patterns visible in the attention maps below.

Building upon these structural insights, we further investigated ERNIE-RNA’s ability to distinguish different RNA families through learned representations. We conducted dimensionality reduction and clustering experiments using a diverse dataset of 244 RNA families from Rfam48. Through repeated sampling experiments across 10 rounds, each analyzing 10 randomly selected RNA categories (sequences shorter than 200 nucleotides), we compared the clustering performance of various feature representations. Both ERNIE-RNA’s CLS token embeddings and attention maps demonstrated superior clustering capability compared to RNA-FM embeddings, and one-hot encoding, as quantified by Fowlkes-Mallows and Rand indices (Fig. 4). This suggests that ERNIE-RNA learns meaningful representations that effectively capture RNA family-specific characteristics during pre-training.

t-SNE visualization comparing clustering results using different feature representations: one-hot encoding (top left), RNA-FM CLS token embeddings (top right), ERNIE-RNA CLS token embeddings (bottom left), and ERNIE-RNA attention maps (bottom right). Each color represents a distinct RNA family category. The Rand Index and Fowlkes-Mallows scores, displayed in the top-left corner of each panel, quantitatively measure the clustering quality.

ERNIE-RNA improves the performance of downstream tasks by fine-tuning on labeled data

The effectiveness of pre-trained RNA language models lies in their ability to extract comprehensive sequence features that can benefit various downstream tasks through fine-tuning. We evaluated ERNIE-RNA’s performance across a broad range of RNA-related tasks, spanning structural analysis, functional studies, and regulatory mechanisms. Despite having fewer parameters and being trained on a smaller dataset than current state-of-the-art models like UNI-RNA, ERNIE-RNA achieves superior or competitive performance in these applications, highlighting the effectiveness of our structure-enhanced pre-training strategy. Below, we present detailed evaluations of these tasks, comparing them against baseline methods and demonstrating ERNIE-RNA’s potential to address key challenges in computational RNA biology.

RNA secondary structure prediction

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of ERNIE-RNA’s secondary structure prediction capabilities. To establish a fair and rigorous comparison, we adopted a unified evaluation framework where all models were retrained from scratch on the specific training set of each benchmark. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, we extracted the token embeddings from all language models, except for the closed-source Uni-RNA, and fed them into an identical downstream prediction network. This standardized setup ensures that performance differences primarily reflect the quality of the representations learned by each LLM. In addition to its token embeddings, ERNIE-RNA offers two unique modes of prediction: a zero-shot capability derived directly from its pre-trained attention heads, and a fine-tuning mode using these structure-enhanced attention maps (ERNIE-RNA attn-map) as direct input to the downstream network. For baseline comparisons, traditional deep learning models like Ufold were also retrained solely on the respective benchmark’s training set, which eliminates potential biases from the mixed-source training data used in their original publications. Our evaluation spans a range of datasets (Supplementary Table 4), from standard benchmarks like bpRNA-1m41, ArchiveII49 and RIVAS47, to challenging cross-family generalization tests bpRNA-new21 and RNA3DB50, to thoroughly assess both performance and robustness.

a Schematic of the unified evaluation framework. For all language models, token embeddings are extracted and fed into a common downstream network for fine-tuning. ERNIE-RNA uniquely offers its attention maps as an alternative feature and allows for zero-shot prediction directly from its pre-trained heads. b–e Violin plots comparing the F1 score distributions of various models on four benchmark datasets with increasing generalization difficulty: b the standard bpRNA-1m TS0 testset (sample size n = 1305); c the RIVAS TestSetB (n = 430); d the bpRNA-new dataset (n = 5388); and e, the RNA3DB-2D testset (n = 158). The red dashed line represents the performance of the best-performing traditional dynamic programming (DP) method on that specific dataset for reference. Within each violin plot, the white center line of the inner box indicates the median, the box represents the interquartile range (IQR, 25th and 75th percentiles), and the whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR. The red star marker indicates the mean F1-score.

On the standard bpRNA-1m benchmark, ERNIE-RNA establishes its state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance. As detailed in Table 1 and Fig. 5b, the ERNIE-RNA attn-map model achieves the highest overall macro-average F1-score of 0.873. Importantly, for direct comparison with other LLMs, the ERNIE-RNA model using token embeddings also delivers an exceptional F1-score of 0.862. This result surpasses other prominent language models, including the 650M-parameter RiNALMo (0.850) and 400M-parameter UNI-RNA (0.821), as well as other classical dynamic programming (DP) methods like Eternafold (0.758) and non-LLM deep learning methods. This performance leadership is consistently maintained across other key benchmarks. On the ArchiveII dataset (Supplementary Table 6), ERNIE-RNA attn-map achieves an F1-score of 0.954, while its embedding-based counterpart (0.951) also significantly outperforms competitors like RiNALMo (0.892). Furthermore, on the challenging RIVAS TestSetB (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 7), ERNIE-RNA’s models again secure the top two positions with F1-scores of 0.721 (attn-map) and 0.706 (embedding), creating a substantial performance gap to the next-best LLM, RiNALMo (0.555). The consistent, per-sequence superiority of ERNIE-RNA’s representations is visually corroborated in the head-to-head scatter plots (Supplementary Fig. 7), where the majority of data points lie above the diagonal across all four datasets when comparing the ERNIE-RNA embedding model to RiNALMo.

To rigorously test the limits of generalization and directly address concerns about data leakage, we further evaluated all models on bpRNA-new and RNA3DB-2D dataset. These two datasets represent the most stringent test scenarios: bpRNA-new contains RNA families from a newer Rfam release completely absent from the training data, while our RNA3DB-2D dataset is meticulously constructed to ensure structural dissimilarity between training and test sets at the component level (see “Methods”). On bpRNA-new, a notable trend emerged: most deep learning models, both LLM-based and non-LLM, underperformed relative to traditional dynamic programming (DP) methods like Eternafold (F1-score 0.639), as shown in Fig. 5d and Table 2. However, when we evaluated ERNIE-RNA with its pre-trained parameters frozen (ERNIE-RNA attn-map frozen and ERNIE-RNA frozen), they surpassed the DP methods, achieving F1-scores of 0.646 and 0.634, respectively. This striking result suggests that ERNIE-RNA’s pre-training phase successfully imbues the model with robust, generalizable structural representations that transfer effectively to other families, even more so than aggressive fine-tuning.

On the even more challenging RNA3DB-2D dataset, which has a very small training set (N = 401), all deep learning methods fell short of the DP baselines (Fig. 5e and Table 2). Nevertheless, ERNIE-RNA frozen and ERNIE-RNA attn-map remained the top-performing deep learning approaches, maintaining a significant lead over all others. This resilience is further highlighted when comparing ERNIE-RNA directly with its strongest competitor, RiNALMo. While RiNALMo’s performance drops sharply on these generalization sets, ERNIE-RNA maintains a more stable and superior performance, as visually confirmed by the head-to-head scatter plots where most points lie above the diagonal (Fig. 6a, b). Finally, Fig. 6c provides qualitative examples of this advantage, showcasing ERNIE-RNA’s ability to accurately predict the complex structures of both a pemK RNA (Rfam RF02913) from the bpRNA-new dataset and a c-di-GMP-I riboswitch aptamer (Rfam RF01051, PDB 4YB1_R) from the RNA3DB-2D test set. For both of these unseen families, ERNIE-RNA attn-map and ERNIE-RNA attn-map frozen delivers near-perfect or highly accurate predictions, starkly contrasting with the significant errors produced by other language and traditional methods.

a Scatter plot comparing per-sample binary F1-scores between fine-tuned ERNIE-RNA and fine-tuned RiNALMo on the bpRNA-new testset. Each point represents an individual RNA sequence, with ERNIE-RNA F1-scores on the x axis and RiNALMo F1-scores on the y axis. b A similar comparison on the RNA3DB-2D testset. c Visualization of RNA secondary structure predictions for two representative Rfam sequences: a pemK RNA (RF02913, top) from bpRNA-new dataset and a c-di-GMP-I riboswitch aptamer (RF01051, PDB 4YB1_R, bottom) from RNA3DB-2D testset. Ground truth structures (leftmost) are compared with predictions from ERNIE-RNA attn-map, ERNIE-RNA attn-map frozen, mxfold2, RNAfold, RNA-FM and RiNALMo. Binary F1-scores below each structure quantify prediction accuracy.

To address the crucial question of model performance across different training data scales, we conducted systematic experiments using varying sizes of training data, from 1000 to 58,000 sequences (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 8). ERNIE-RNA attn-map demonstrates consistent performance advantages across all training set sizes, achieving a macro-average F1-score of 0.821 even with just 1000 training sequences, compared to RNA-FM’s 0.728. This robust performance at limited data scales, combined with continued improvements as training data increases, suggests that ERNIE-RNA’s structure-enhanced pre-training provides a strong foundation for RNA secondary structure prediction regardless of downstream training data availability.

These results collectively highlight the robustness, scalability, and efficiency of ERNIE-RNA for RNA secondary structure prediction, even with limited pre-trained data or a smaller model size compared to other methods. The consistent improvements across diverse datasets and evaluation metrics establish ERNIE-RNA as a powerful tool for downstream RNA analysis tasks.

RNA contact map prediction

RNA contact map prediction task refers to predicting the spatial distances between nucleotides within RNA molecules based on their one-dimensional sequence. An RNA contact map employs a two-dimensional matrix wherein each cell indicates whether the distance between nucleotides at corresponding positions in the RNA molecule’s three-dimensional structure is below a predefined threshold (typically 8 Å). Nucleotides falling within this threshold are in closer spatial proximity. We downloaded the benchmark datasets from RNAcontact51, which contains 301 sequences with more than 5 contacts, and divided the dataset into 221 training (TR221) and 80 testing (TS80) sets.

We designed various models based on the ResNet downstream architecture, with different combinations of features, including one-hot, MSA (named Cov), RNA secondary structure predicted by PETfold20 (named SS), attention maps extracted from ERNIE-RNA and token embeddings extracted from ERNIE-RNA and RNA-FM. Notably, the ResNet using features from ERNIE-RNA achieved state-of-the-art performance. As shown in Supplementary Table 8, the model leveraging ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps as input surpassed all other methods, including the highly complex RNAcontact (100-model ensemble), achieving a Top-L/1 precision of 0.68. This represents a significant improvement over both traditional feature sets like Cov+SS (0.46) and one-hot encodings (0.33). Furthermore, when using standard token embeddings for a direct comparison with other LLMs, ERNIE-RNA (Top-L/1 precision of 0.47) also consistently outperformed all other language models, such as RNA-FM (0.42). These results, visualized in Fig. 7a, strongly indicate that the superior performance stems from the rich structural features effectively encoded by ERNIE-RNA’s pair-wise position bias during pre-training, making its representations exceptionally well-suited for 3D contact prediction.

a RNA contact maps of two randomly selected samples predicted by different methods. The first column shows true label. b Histogram depicting AUPRC distributions across 17 proteins compared to Seq baseline, denoted by the horizontal dashed line. ERNIE-RNA outperforms all other tested methods in most cases.

5’UTR sequence mean ribosomal loading (MRL) prediction

The 5’UTR (untranslated region) MRL prediction task refers to predicting the mean ribosomal loading onto the 5’UTR sequences, which is often used to evaluate the translation efficiency of corresponding RNA sequences. We downloaded the benchmark dataset from Optimus 5-prime52, which comprises 83,919 artificially synthesized random 5’UTRs and 7600 real human 5’UTRs along with corresponding MRL values.

We selected 7600 synthesized random 5’UTRs as the random test set with the remaining 76,319 synthesized random 5’UTR sequences as the training set. The 7600 human 5’UTRs was used as the human test set to assess the model’s ability to generalize beyond synthetic 5’UTR sequences. We found that the performance of all tested models was worse on the human test set than on the random test set. This may be due to distributional differences between the two datasets. As shown in Supplementary Table 9, ERNIE-RNA-conv achieved the best performance on the random test set (R2 = 0.92) and the human test set (R² = 0.86), outperforming all other tested RNA language models. Although ERNIE-RNA-mlp utilized only two simple MLP layers as its downstream architecture, fine-tuning performance is close to the SOTA (R2 = 0.91 on the random test set and R² = 0.84 on the human test set). Despite having the smallest model size and the least pre-training data, ERNIE-RNA demonstrated the best generalizability for 5’UTR sequences MRL prediction task among all tested language models.

RNA-protein binding prediction

RNA-protein binding is a common biological phenomenon within cells and plays a critical role in various cellular activities, including cell-signaling and translation. We conducted experiments using the benchmark dataset from PrismNet53, which included icSHAPE data. We divided the dataset into several sub-datasets according to different RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and cell environments. We finally chose 17 RBPs in the HeLa cell environment. We designed models using two downstream architectures: a simple MLP network was used for evaluating the CLS token from all language models, while the more complex PrismNet network was used for models with sequence-level features like one-hot encoding, icSHAPE data, or ERNIE-RNA’s full token embeddings.

As shown in Supplementary Table 10 and Fig. 7b, the model using icSHAPE and one-hot encoding features as input has a higher mean AUPRC than that only with one-hot encoding features, which may be due to the RNA secondary structure information provided by icSHAPE. Notably, the ERNIE-RNA (MLP), which only use CLS token embedding as input performed better than all previous methods and all other tested RNA language models, including RiNALMo and RNA-MSM. Furthermore, the model replacing icSHAPE with token embeddings extracted by ERNIE-RNA is the best among all tested models, suggesting that ERNIE-RNA can learn sufficient information about structures and functions from raw RNA sequences, benefiting the downstream functional prediction task.

ncRNA family classification

Accurate classification of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) into functional families is essential for understanding their diverse roles in gene regulation and cellular processes. This task presents significant computational challenges due to the high dimensionality of sequence space and the subtle differences between ncRNA families. Although traditional methods rely heavily on predicted secondary structures for classification, they are computationally intensive and may not fully capture the sequence-structure-function relationships. Following the established benchmark by Noviello et al.54, we formulated ncRNA family classification as a closed-set multi-class classification task, where sequences are assigned to one of 88 predefined Rfam families. This standard formulation enables direct comparison with previous state-of-the-art methods and focuses on evaluating the model’s ability to distinguish between known ncRNA families.

We tested the model’s robustness by introducing boundary noise - random nucleotides added to both ends of the sequences while maintaining the original nucleotide frequencies - ranging from 0% to 200% of sequence length. ERNIE-RNA achieved superior accuracies of 0.9844 and 0.9820 under 0% and 200% boundary noise conditions, respectively (Supplementary Table 11), outperforming previous methods while using significantly fewer parameters (86 M) than UNI-RNA (169 M). This consistent performance across varying noise levels demonstrates ERNIE-RNA’s robust feature extraction capabilities and suggests that its structure-enhanced representations provide a more efficient framework for ncRNA classification than previous approaches.

Multi-species splice site prediction

Accurate prediction of splice sites—the boundaries between exons and introns in pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA)—is essential for precise gene annotation and understanding gene expression regulation. This task is computationally challenging due to the short, highly conserved motifs defining splice sites and the presence of non-canonical splice sites that deviate from the GT-AG consensus sequence55. We evaluated ERNIE-RNA’s capability to predict splice sites using two distinct benchmark datasets: (1) A multi-species dataset from Spliceator56, comprising curated, confirmed splice sites from over 100 eukaryotic species, with four species (zebrafish, fruit fly, worm, and Arabidopsis) held out for testing; and (2) A dataset from the BEACON benchmark57 using the SpliceAI dataset55, containing ~15,000 splice sites from human pre-mRNAs.

On the multi-species dataset, ERNIE-RNA achieved F1-scores of 0.9612, 0.9180, 0.9203, and 0.9294 for zebrafish, fruit fly, worm, and Arabidopsis respectively (Supplementary Table 12). While UNI-RNA and SpliceBERT demonstrate slightly higher F1-scores (ranging from 0.9343 to 0.9635), ERNIE-RNA shows strong and consistent performance across all species, with a more parameter-efficient architecture (86 M parameters compared to UNI-RNA’s 169 M). These minor performance differences may be attributed to UNI-RNA’s incorporation of mRNA and pre-mRNA sequences in its pre-training data, which naturally contain rich information about splice sites.

On the SpliceAI dataset, ERNIE-RNA significantly outperformed existing methods with a top-K accuracy of 55.37%, compared to RNA-FM (34.84%), RNABERT (0.18%), and RNA-MSM (38.33%) (Supplementary Table 13). This substantial improvement demonstrates ERNIE-RNA’s superior capability in capturing complex splicing patterns from the primary sequence alone, which is particularly valuable for annotating splice sites in non-model organisms, where experimental validation data may be limited.

Alternative polyadenylation prediction

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) is a crucial post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism that generates mRNA isoforms with distinct 3’ untranslated regions (3’ UTRs), influencing gene expression and protein function. The process is controlled through a complex interplay between cis-regulatory elements - primarily polyadenylation signals (PAS) centered around the AATAAA hexamer motif - and trans-acting RNA-binding proteins that recognize these sequences58. We evaluated ERNIE-RNA’s performance on this task using the BEACON benchmark’s APA dataset derived from the APARENT study57,58 - a massively parallel reporter assay measuring isoform ratios from over 3 million unique UTR sequences constructed from 13 libraries, including both synthetic sequences with randomized regulatory regions and natural human PAS.

ERNIE-RNA achieved a significantly higher R² score (78.39%) compared to existing methods such as RNA-FM (70.32%), RNABERT (57.66%), and RNA-MSM (70.40%) on the BEACON benchmark (Supplementary Table 14). This improvement is particularly noteworthy given the established complexity of APA regulation, which is known to involve the coordinated action of core polyadenylation machinery components, including CPSF, CstF, and CFIm, along with numerous auxiliary factors that bind to upstream and downstream sequence elements58. This finding suggests that ERNIE-RNA is able to effectively model these complex interactions.

This superior performance suggests that ERNIE-RNA effectively models the multiple sequence determinants governing PAS selection, from the core hexamer to the extended regulatory context. The model maintains robust prediction accuracy, even on challenging held-out test sets containing diverse UTR contexts, demonstrating its ability to generalize beyond its training scenarios. This capability has important implications for understanding post-transcriptional gene regulation mechanisms and, potentially, for engineering synthetic 3’ UTRs with desired polyadenylation patterns for therapeutic applications.

Discussions

To effectively utilize the vast amount of unlabeled RNA sequences and extract RNA features with more comprehensive semantic information, we trained an RNA language model, named ERNIE-RNA, using 20.4 million non-coding RNAs from RNAcentral. Our results demonstrate that ERNIE-RNA’s attention maps inherently capture RNA structural features through pre-training alone. Upon fine-tuning, ERNIE-RNA achieves SOTA performance in downstream tasks like RNA secondary structure, RNA contact map, UTR-MRL and RNA-protein binding prediction.

While ERNIE-RNA has demonstrated promising results, several limitations and future directions warrant consideration. First, the current model has a sequence length constraint of 1024 nucleotides, which may limit its applicability to longer RNA molecules, such as certain lncRNAs. Second, our pre-training solely focused on ncRNA sequences, potentially limiting the model’s downstream applications compared to methods like UTR-LM34 and CaLM35 that specifically incorporate mRNA and UTR sequences in their training data. Third, while our pair-wise attention bias mechanism enables emergent structural feature extraction capabilities, the mathematical principles underlying this emergent phenomenon lack thorough theoretical understanding and require further investigation.

Looking ahead, several promising directions could further enhance ERNIE-RNA’s capabilities. First, exploring larger-scale pre-training with more diverse RNA sequences, particularly mRNA and UTR data, may unlock additional emergent abilities. Second, incorporating multi-modal data, such as experimental structure probing data or evolutionary information, could provide complementary signals for more accurate predictions. Third, adapting ERNIE-RNA for RNA therapeutic applications represents a valuable future direction. Given its strong performance in capturing RNA structural and functional features, ERNIE-RNA could potentially accelerate the development of RNA therapeutics through applications such as mRNA vaccine sequence optimization, RNA-based drug design, and RNA-small molecule interaction prediction.

In summary, our results show that ERNIE-RNA offers informative features for RNA modeling and may contribute to future investigations of RNA biology. The success of our structure-enhanced attention mechanism also suggests that incorporating domain-specific prior knowledge into language model architectures may be a broadly applicable strategy for improving biological sequence analysis. This approach could potentially benefit pre-trained language models for other biomolecules, such as proteins, DNA, and complex molecular assemblies.

Methods

Training dataset

We collected a dataset of 34 million raw non-coding RNA (ncRNA) sequences from RNAcentral database (release 21), which is the largest dataset of ncRNA to date. We substituted T with U within the sequences and used 11 different symbols, namely ‘N,’ ‘Y,’ ‘R,’ ‘S,’ ‘K,’ ‘W,’ ‘M,’ ‘D,’ ‘H,’ ‘V,’ and ‘B,’ to represent distinct degenerate bases, as illustrated in Supplementary Table 15. After refining the vocabulary, CD-HIT-EST59 was used to remove redundant sequences above 100% similarity, resulting in 25 million non-redundant sequences. We further filtered out sequences longer than 1024 and obtained a large-scale pre-training dataset consisting of 20.4 million ncRNA sequences ultimately. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the length distribution and type distribution of this dataset.

Model architecture

In this work, we introduced a RNA pre-trained language model, named ERNIE-RNA, which enhances structural information based on the modified BERT architecture. ERNIE-RNA consists of 12 transformer blocks and each block contains 12 attention heads. Every token in the sequence is mapped to a 768-dimensional vector, resulting in 86 million parameters. Specifically, we used the one-dimensional RNA sequence to compute a pair-wise position matrix to replace the bias of the first layer in the ERNIE-RNA. From the second layer onward, the bias of each layer is determined by the attention map of the previous layer. This integration introduces RNA structural information into the attention map calculation at each layer, allowing for the extraction of more comprehensive semantic features. The improved self-attention formula is as follows:

For a RNA sequence with length L, ERNIE-RNA takes raw sequential tokens as input, resulting in an L × 768 × 12 embedding matrix and an L × L × 156 attention maps, where 156 equals 12 × 13, 12 represents the num of attention heads and 13 represents the num of transformer blocks plus 1 (manually calculated pair-wise position matrix).

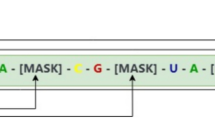

Training details

For pre-training, we followed a self-supervised training manner in RNA-FM. Around 15% of nucleotide tokens are randomly replaced with a special token. (If the i-th token is chosen, we replace the i-th token with (1) the [MASK] token 80% of the time (2) a random token 10% of the time (3) the unchanged i-th token 10% of the time). We train ERNIE-RNA with masked language modeling (MLM), which predict the masked token with cross-entropy loss.

We use fairseq60 to train ERNIE-RNA for about 20 days on 24 32G-V100. During the pre-training process, we adopted the following hyperparameter configuration: the base learning rate was set to 0.0001, the warmup step was set to 20000 steps, and the weight-decay was set to 0.01. In order to speed up the training of the network while reducing the memory usage, we constrain the maximum length of the input sequence to 1024.

Downstream dataset

RNA secondary structure dataset

bpRNA-1m:

This dataset, introduced by Danaee et al., is a large-scale collection of RNA secondary structures. We used three versions of this dataset: bpRNA-1m (all): Contains 102,318 single-molecule RNA secondary structures annotated using bpRNA; bpRNA-1m (90): A deduplicated version of bpRNA-1m (all) with sequences filtered at 90% similarity, yielding a cleaner dataset with 28,370 training sequences; bpRNA-1m (80): The standard benchmark dataset for secondary structure prediction, filtered at 80% similarity, with 10,814 training sequences (TR0), 1300 validation sequences (VL0), and 1305 testing sequences (TS0). This is the version used for our primary secondary structure prediction experiments, and our data splitting ensures consistency with previous work (Ufold, RNA-FM) to allow fair comparison. Unlike UNI-RNA, which used both RNAstralign and TR0 for training, we only used TR0 to train ERNIE-RNA and tested it on TS0.

ArchiveII:

This dataset, originally curated by Sloma and Mathews (2016), is a comprehensive benchmark containing 2975 RNA sequences with known secondary structures across 10 diverse RNA families. The sequence lengths range from 28 to 2968 nucleotides. We used ArchiveII to evaluate the performance of models on a dataset with diverse RNA families, including those not seen during training. It is complementary to the RNAStrAlign dataset.

bpRNA-new:

To further assess cross-family generalization, we utilized the bpRNA-new dataset. This test set, derived from Rfam 14.2, comprises 5,401 sequences from RNA families that are entirely different from those in the bpRNA-1m benchmark. For this evaluation, models were trained on the bpRNA-1m (80) training set and tested on bpRNA-new, providing a direct measure of their ability to generalize to unseen RNA families.

RNA3DB-2D dataset: To provide rigorous evaluation of generalization and to explicitly address concerns about data leakage from structural homology, we constructed a new benchmark dataset based on the RNA3DB (v. 2024-12-04) release. The core advantage of RNA3DB is its methodology for creating structurally-dissimilar dataset splits. It first groups all RNA chains into “Components” based on structural homology, ensuring that different RNA family (Components) are structurally non-redundant. These Components are then assigned to train, validation, or test sets, which fundamentally prevents structural information from leaking between the splits. We have made our entire data processing pipeline, which transforms the 3D structures from RNA3DB into 2D secondary structure data in BPSEQ format, publicly available for full reproducibility (see our repository at https://github.com/ZYZhang17/RNA3DB-2D-Structures).

Briefly, the pipeline (Supplementary Fig. 9) begins by downloading all required RNA3DB mmCIF files from the PDB. Each file is then parsed using rnapolis-py to extract RNA chains and their secondary structures, followed by a critical sequence correction step. We apply a series of filters (e.g., based on sequence length and resolution) and select a single, high-quality representative chain for each structurally-dissimilar cluster defined by RNA3DB. These selected clusters are then partitioned into training, validation, and test sets using RNA3DB’s core splitting logic. Finally, the secondary structures of the selected chains are converted into BPSEQ and then a pickle format suitable for machine learning. This entire process yielded a final benchmark with 401 training, 127 validation, and 161 testing sequences, forming the basis of our most stringent generalization tests.

RIVAS dataset:

This dataset, introduced by Rivas et al., is specifically designed to assess cross-family generalization of RNA secondary structure prediction methods. It contains three subsets: TrainSetA (3166 sequences), TestSetA (697 sequences), and TestSetB (430 sequences). TestSetB is particularly challenging as it contains RNA families distinct from both training and validation sets. We used TestSetB to evaluate the model’s ability to generalize to previously unseen RNA families.

Following data acquisition from their original sources.all datasets underwent cross-validation against the standardized versions available in multimolecule (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12638419), a comprehensive library for molecular biology machine learning. Multimolecule provides curated biomolecular datasets and standardized data processing pipelines, enabling reproducible benchmarking across different studies. This validation step ensures data consistency and reliability while aligning with community standards for RNA structure prediction tasks.

RNA 3D closeness dataset

We utilized the benchmark datasets from RNAcontact51, which is available at (https://yanglab.qd.sdu.edu.cn/RNAcontact/benchmark/). The original 1786 sequences were downloaded from PDB and those lengths outside the range of 32 to 1000 were first excluded, leaving 511 sequences remained. CD-HIT-EST and BLASTclust61 were used to remove redundant sequences above 30% similarity, resulting in 336 non-redundant sequences. The distance between any two bases is defined as the minimum atom-pair distance. Bases’ distance within 8 Å were labeled positive contacts. Finally, sequences with <5 contacts were removed, leaving 301 sequences divided into 221 training (TR221) and 80 testing (TS80) sets. In order to select the model checkpoint more fairly, we further randomly divided TR221 into two parts according to the ratio of 8:2, recorded as TR168 and VL43.

RNA 5’UTR mean ribosome loading dataset

Our experiments relied on a benchmark dataset obtained from Optimus 5-prime, including 83,919 artificially synthesized random 5’UTRs with their corresponding mean ribosomal loading (MRL) values. These sequences ranged from 25 to 100 nucleotides in length. To ensure the accuracy of our model’s testing across various 5’UTR lengths, we meticulously selected the top 100 5’UTRs of each length, prioritizing those with the deepest sequencing and highest read counts to enhance confidence in sequencing outcomes. This yielded a total of 7600 sequences for the test set, while the remaining 76,319 sequences constituted the training set. Additionally, we enriched our analysis by incorporating an extra dataset comprising 7600 real human 5’UTRs with the similar length distribution.

RNA protein binding dataset

We conduct experiments on a benchmark dataset from PrismNet, which includes icSHAPE data. We divided them into several sub-datasets according to different corresponding RBPs and different cell environment. We finally chose 17 RBPs in HeLa cell environment as RNA-FM did to make a fair comparison. The number of RNA sequences of each RBP ranges from 1827 to 15002. We partitioned 20% of the data into a test set following an 8:2 ratio. Subsequently, the remaining 80% of the data was divided into a training set and a validation set at a ratio of 9:1. The length of all sequences from different RBPs is 101 nucleotides.

ncRNA family classification dataset

We utilized a comprehensive benchmark dataset curated by Noviello et al.54, derived from the Rfam database (version 14). This dataset encompasses a diverse collection of short ncRNA sequences (<200 nucleotides) distributed across 88 distinct families, providing a rigorous test set for assessing the model’s ability to discern subtle differences between ncRNA families. This dataset is specifically designed to evaluate the model’s robustness to noise in the input sequences, mimicking real-world scenarios where the precise boundaries of ncRNA transcripts may not be known. The dataset contains sequences with varying levels of boundary noise: including a “clean” dataset with 0% boundary noise and a “noisy” dataset with 200% boundary noise. The boundary noise was introduced by adding random nucleotides to both ends of each sequence while preserving the original nucleotide frequencies, simulating the uncertainty in transcript boundaries that can arise from experimental limitations or natural variations. For each noise level, the dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing sets.

Splice site prediction dataset

We utilized two established benchmark datasets: (1) the widely used multi-species dataset from Spliceator56, and (2) the human splice site dataset from the BEACON benchmark, derived from the SpliceAI study. The multi-species dataset comprises a curated collection of experimentally validated splice sites from over 100 eukaryotic species, providing a diverse and challenging test set for assessing cross-species generalizability. The BEACON SpliceAI dataset, on the other hand, focuses specifically on human splice sites and provides a large-scale, high-quality resource for evaluating model performance in a human-specific context. For both datasets, input sequences were prepared by extracting 400-nucleotide windows centered on the potential splice sites (200 nucleotides upstream and downstream). This window size was chosen to capture sufficient flanking sequence context while maintaining computational efficiency.

Alternative polyadenylation dataset

We employed a processed version of the APARENT dataset58, as described in the BEACON benchmark. The original APARENT dataset contains a diverse collection of polyA site sequences derived from massively parallel reporter assays, encompassing over 3 million unique sequences with corresponding isoform expression data58. For the BEACON benchmark, this dataset was further processed and formatted to provide a standardized resource for evaluating APA prediction models. The dataset provides a valuable resource for evaluating the model’s ability to capture the complex interplay of sequence features that govern polyA site selection.

Downstream tasks

RNA secondary structure prediction

We evaluated the performance of ERNIE-RNA and other baseline models on the RNA secondary structure prediction task using two distinct evaluation paradigms: zero-shot prediction and fine-tuning.

Zero-shot Prediction:

To assess the structural information learned implicitly during pre-training, we evaluated ERNIE-RNA in a zero-shot setting without any fine-tuning. In this approach, the attention maps from all 13 layers and 12 heads of the pre-trained ERNIE-RNA model were extracted for each input sequence. Each attention map was treated as a pairwise probability matrix representing potential base-pairing interactions. Due to the stochastic nature of pre-training, the specific layer and head that best capture structural information can vary. In our provided pre-trained model checkpoint, the 6th head of the final layer (Head 5 in Fig. 2) demonstrates optimal performance for zero-shot structure prediction, so we selected this specific head for zero-shot prediction tasks. The resulting probability matrix from this head was then converted into a final binary contact map using a post-processing algorithm adapted from E2Efold, which enforces structural constraints such as base-pairing rules.

Fine-tuning:

To evaluate the models’ ultimate performance, we fine-tuned them on the training set of each RNA secondary structure dataset. For a fair and direct comparison, all language models, including ERNIE-RNA, RiNALMo, RNA-FM, RNAErnie, RNA-MSM and RNA-BERT, were evaluated by feeding their token embeddings into a unified ResNet-based downstream network. In parallel, to leverage the unique, structure-aware features of our model, we also evaluated ERNIE-RNA by using its attention maps as direct 2D input to a lighter, custom CNN architecture (so called ERNIE-RNA attn-map and ERNIE-RNA attn-map frozen). For all evaluations, the parameters of the downstream networks were randomly initialized, while the upstream language models either had their pre-trained parameters updated during fine-tuning or kept frozen, depending on the specific experiment. Additionally, non-LLM baselines like Ufold were retrained from scratch on the same training sets to ensure a fair comparison.

In the fine-tuning stage, all models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 1. The learning rate was set to 1e-5 for fully fine-tuned models and 1e-4 for variants with a frozen backbone. We used a binary cross-entropy loss function with a positive weight of 300 to address the imbalance between paired and unpaired bases. An early stopping mechanism was employed, terminating the training if the F1-score on the validation set did not improve for 20 consecutive epochs. For the final RNA secondary structure prediction, the output matrices from all models were processed using the same E2Efold-style post-processing algorithm to generate the final contact maps.

RNA 3D closeness prediction

The task of RNA 3D closeness prediction aims to identify nucleotide pairs that are spatially close (typically within an 8 Å distance) in the folded 3D structure. As this task can also be framed as a two-dimensional matrix prediction problem, we utilized the same downstream architectures and training methodologies described for the RNA secondary structure prediction task. All models, including the various ERNIE-RNA configurations and other LLMs, were trained and evaluated using the same features (token embeddings or attention maps) and training protocols.

Performance for this task was measured using the Long-Range Top-L precision metric. This metric specifically evaluates the accuracy of contacts between nucleotides that are separated by more than 24 residues in the primary sequence (|i-j | ≥24). Precision is calculated for the top L/10, L/5, L/2, and L/1 predicted long-range contacts, where L is the sequence length.

RNA 5’UTR mean ribosome loading prediction

Prior to model construction and training, we firstly standardized the Mean Ribosomal Loading (MRL) values to be predicted, which may improve the convergence and overall performance of the model during fine-tuning. Two distinct models were constructed: ERNIE-RNA-token-conv and ERNIE-RNA-token-mlp. The former used Token Embedding except for CLS and EOS tokens from ERNIE-RNA, and employed a convolutional residual neural network as its downstream architecture. Conversely, ERNIE-RNA-token-mlp utilized the CLS token embedding provided by ERNIE-RNA to mitigate the impact of sequences of varying lengths. It employed a simple two-layer fully connected network to further extract features. During the fine-tuning phase, we initialized the base learning rate to 1e-5 and employed the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function to iteratively update model parameters. The number of tolerable epochs was set to 10. Considering that the design of ERNIE-RNA-token-conv is related to the input length, and the longest sequence length in the training set is 100, we applied padding to standardize the sequence length across the entire dataset to 100 for model input.

For a comprehensive and fair comparison, we also evaluated several other prominent RNA language models, including RiNALMo, RNA-MSM, RNA-FM, RNAErnie, and RNA-BERT. These models were accessed via the multimolecule package (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12638419). To ensure a direct comparison of the models’ representation power, we used their token embeddings as input and coupled them with the exact same downstream network architecture, optimizer, and training hyperparameters as our ERNIE-RNA (conv) model. This standardized setup guarantees that any observed performance differences are attributable to the quality of the pre-trained embeddings themselves.

RNA protein binding prediction

We designed two models: ERNIE-RNA-PRSIMNET and ERNIE-RNA-MLP. ERNIE-RNA-PRSIMNET adopted the main architecture of PrismNet, but replaced the icSHAPE input with token embedding except for the CLS and EOS tokens from ERNIE-RNA. ERNIE-RNA-MLP took only the CLS token embedding provided by ERNIE-RNA as input and further extracted features through a straightforward two-layer fully connected network. During the fine-tuning phase, we initialized the base learning rate to 1e-5 and employed the cross-entropy loss function to update model parameters. Additionally, we set 10 as the maximum number of tolerable epochs. For comparison, other language models (RiNALMo, RNA-MSM, etc.) were evaluated using the same downstream architecture and training protocol as described above.

ncRNA family classification

The task follows the standard closed-set multi-class classification paradigm, where each input ncRNA sequence is mapped to one of the 88 predefined family labels. We employed a fine-tuning strategy, leveraging the pre-trained ERNIE-RNA model as a feature extractor and adding a classification head tailored for this task. The classification head consists of four ResNet layers, outputting a probability distribution over the 88 ncRNA families. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-4 and a batch size of 32. The cross-entropy loss function was used to measure the discrepancy between the predicted and true family labels. Model performance was evaluated using classification accuracy, providing a comprehensive measure of the model’s ability to correctly assign ncRNA sequences to their respective families. For comparison, other language models (RiNALMo, RNA-MSM, etc.) were evaluated using the same downstream architecture and training protocol as described above.

Splice site prediction

The task is to predict the location of splice sites (both donor and acceptor sites) within a given pre-mRNA sequence. We fine-tuned the ERNIE-RNA model using a binary cross-entropy loss function, optimizing the model’s parameters to accurately distinguish between true splice sites and non-splice sites. To ensure robust performance and avoid overfitting, we employed an early stopping strategy based on the model’s performance on a held-out validation set. Model-specific hyperparameters, including the learning rate and the number of training epochs, were optimized using a grid search approach on the validation set. Performance was evaluated using standard metrics for binary classification, including precision, recall, and F1-score. For comparison, other language models (RNA-FM, RNA-MSM, etc.) were evaluated using the same downstream architecture and training protocol as described above.

Alternative polyadenylation

The task is to predict the relative usage of proximal versus distal polyA sites, quantified as isoform percentages. We employed a mean squared error (MSE) loss function to measure the discrepancy between the predicted and experimentally determined isoform percentages. To ensure that the model could effectively learn the subtle sequence determinants of polyA site choice, we implemented a regression head on top of the pre-trained ERNIE-RNA backbone. The regression head consists of two layers of one-dimensional convolution and five layers of ResNet. After passing through the Sigmoid layer, a continuous value is output, representing the predicted percentage of homomorphism. We employed an early stopping strategy based on the model’s performance on a held-out validation set, terminating training when the validation loss ceased to improve. Additionally, we incorporated L2 regularization into the loss function to penalize large weights and encourage the model to learn a more parsimonious representation of the underlying sequence features.

Data availability

The processed RNAcentral datasets62 used for pretraining are available in the Figshare repository under the (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28034282.v1). The RNA3DB-2D dataset63 generated in this study has been deposited in the Figshare repository under the (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30144502.v1). All other datasets used in this study are publicly available from their original sources. Specifically, the bpRNA-1m41 (all, 90, 80) datasets are available at (https://bprna.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/download.php#bpRNA-1m) and (https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/3yj80cr6febz9a8xv8oio/bpRNA_dataset.zip) The bpRNA-new dataset21 used is available at (https://github.com/mxfold/mxfold2/releases/download/v0.1.1/bpRNAnew.tar.gz); The RNAstrAlign dataset is available at (https://github.com/mxfold/mxfold2/releases/download/v0.1.1/RNAStrAlign.tar.gz); The ArchiveII dataset is available at (https://github.com/mxfold/mxfold2/releases/download/v0.1.1/archiveII.tar.gz) The RIVAS dataset47 is available at (https://github.com/mxfold/mxfold2/releases/download/v0.1.1/Rivas.tar.gz); The RNA 3 d closenesss dataset51 is available at (https://yanglab.qd.sdu.edu.cn/RNAcontact/benchmark/); The Optimus 5-prime RNA 5’UTR mean ribosome loading dataset52 is available from GEO (GSE114002); The PrismNet dataset53 is available at (https://zhanglabnet.oss-cn-beijing.aliyuncs.com/prismnet/data/clip_data.tgz); The ncRNA classification dataset54 is available at (https://github.com/bioinformatics-sannio/ncrna-deep/tree/master/datasets); The Spliceator splice site prediction dataset56 is avaliable at (https://git.unistra.fr/nscalzitti/spliceator/-/tree/master/Data); The SpliceAI splice site prediction dataset55 and APARENT alternative polyadenylation dataset58 by BEACON57 are available at (https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1nBytCBey8CRYnAagwvwjDU1yFrYkBRo2). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The ERNIE-RNA scripts64 are available at (https://github.com/Bruce-ywj/ERNIE-RNA. The RNA3DB-2D data processing pipeline65 are available at https://github.com/ZYZhang17/RNA3DB-2D-Structures.

References

Caprara, M. G. & Nilsen, T. W. RNA: Versatility in form and function. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 831–833 (2000).

Sharp, P. A. The centrality of RNA. Cell 136, 577–580 (2009).

Fu, X.-D. Non-coding RNA: a new frontier in regulatory biology. Natl. Sci. Rev. 1, 190–204 (2014).

Mattick, J. S. & Makunin, I. V. Non-coding RNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, R17–R29 (2006).

Cobb, M. Who discovered messenger RNA?. Curr. Biol. 25, R526–R532 (2015).

Mortimer, S. A., Kidwell, M. A. & Doudna, J. A. Insights into RNA structure and function from genome-wide studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 469–479 (2014).

Ganser, L. R., Kelly, M. L., Herschlag, D. & Al-Hashimi, H. M. The roles of structural dynamics in the cellular functions of RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 474–489 (2019).

Fürtig, B., Richter, C., Wöhnert, J. & Schwalbe, H. NMR spectroscopy of RNA. ChemBioChem 4, 936–962 (2003).

Cheong, H.-K., Hwang, E., Lee, C., Choi, B.-S. & Cheong, C. Rapid preparation of RNA samples for NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. Nucleic acids Res. 32, e84 (2004).

Fica, S. M. & Nagai, K. Cryo-electron microscopy snapshots of the spliceosome: structural insights into a dynamic ribonucleoprotein machine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 791–799 (2017).

Spitale, R. C. et al. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature 519, 486–490 (2015).

Lorenz, R. et al. ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 6, 1–14 (2011).

Mathews, D. H. & Turner, D. H. Prediction of RNA secondary structure by free energy minimization. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16, 270–278 (2006).

Reuter, J. S. & Mathews, D. H. RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 1–9 (2010).

Do, C. B., Woods, D. A. & Batzoglou, S. CONTRAfold: RNA secondary structure prediction without physics-based models. Bioinformatics 22, e90–e98 (2006).

Huang, L. et al. LinearFold: linear-time approximate RNA folding by 5’-to-3’dynamic programming and beam search. Bioinformatics 35, i295–i304 (2019).

Hafner, M. et al. CLIP and complementary methods. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 1–23 (2021).

Nostrand, E. L. V. et al. Robust transcriptome-wide discovery of RNA-binding protein binding sites with enhanced CLIP (eCLIP). Nat. Methods 13, 508–514 (2016).

Tan, Z., Fu, Y., Sharma, G. & Mathews, D. H. TurboFold II: RNA structural alignment and secondary structure prediction informed by multiple homologs. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 11570–11581 (2017).

Seemann, S. E., Gorodkin, J. & Backofen, R. Unifying evolutionary and thermodynamic information for RNA folding of multiple alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 6355–6362 (2008).

Singh, J., Hanson, J., Paliwal, K. & Zhou, Y. RNA secondary structure prediction using an ensemble of two-dimensional deep neural networks and transfer learning. Nat. Commun. 10, 5407 (2019).

Fu, L. et al. UFold: fast and accurate RNA secondary structure prediction with deep learning. Nucleic acids Res. 50, e14–e14 (2022).

Sato, K., Akiyama, M. & Sakakibara, Y. RNA secondary structure prediction using deep learning with thermodynamic integration. Nat. Commun. 12, 941 (2021).

Pan, X., Rijnbeek, P., Yan, J. & Shen, H.-B. Prediction of RNA-protein sequence and structure binding preferences using deep convolutional and recurrent neural networks. BMC Genom. 19, 1–11 (2018).

Pan, X. & Shen, H.-B. Predicting RNA–protein binding sites and motifs through combining local and global deep convolutional neural networks. Bioinformatics 34, 3427–3436 (2018).

Reuter, J. A., Spacek, D. V. & Snyder, M. P. High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol. cell 58, 586–597 (2015).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., Toutanova, K. & Computat, L. A. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. in 4171–4186 (Minneapolis, MN, 2019).

Chen, J. et al. Interpretable RNA foundation model from unannotated data for highly accurate RNA structure and function predictions. bioRxiv 2022.08. 06.503062 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. UNI-RNA: universal pre-trained models revolutionize RNA research. bioRxiv 2023.07. 11.548588 (2023).

Penić, R. J., Vlašić, T., Huber, R. G., Wan, Y. & Šikić, M. RiNALMo: general-purpose RNA language models can generalize well on structure prediction tasks. Nat. Commun. 16, 5671 (2025).

Akiyama, M. & Sakakibara, Y. Informative RNA base embedding for RNA structural alignment and clustering by deep representation learning. NAR genomics Bioinforma. 4, lqac012 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multiple sequence alignment-based RNA language model and its application to structural inference. Nucleic Acids Res 52, e3–e3 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Multi-purpose RNA language modelling with motif-aware pretraining and type-guided fine-tuning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 548–557 (2024).

Chu, Y. et al. A 5′ UTR language model for decoding untranslated regions of mRNA and function predictions. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 449–460 (2024).

Outeiral, C. & Deane, C. M. Codon language embeddings provide strong signals for use in protein engineering. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 170–179 (2024).

Li, S. et al. CodonBERT large language model for mRNA vaccines. Genome Res 34, 1027–1035 (2024).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017)

Zhang, Y. et al. Multiple sequence alignment-based RNA language model and its application to structural inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, e3–e3 (2024).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Zhou, G. et al. Uni-mol: A universal 3d molecular representation learning framework. (2023).

Danaee, P. et al. bpRNA: large-scale automated annotation and analysis of RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 5381–5394 (2018).

Lorenz, R. et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol.: AMB 6, 26 (2011).

Reuter, J. S. & Mathews, D. H. RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinform 11, 129 (2010).

Staple, D. W. & Butcher, S. E. Pseudoknots: RNA Structures with Diverse Functions. PLoS Biol. 3, e213 (2005).

Zuker, M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 3406–3415 (2003).

Cao, S. & Chen, S.-J. Predicting RNA pseudoknot folding thermodynamics. Nucleic Acids Res 34, 2634–2652 (2006).

Rivas, E., Lang, R. & Eddy, S. R. A range of complex probabilistic models for RNA secondary structure prediction that includes the nearest-neighbor model and more. RNA 18, 193–212 (2012).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D192–D200 (2020).

Sloma, M. F. & Mathews, D. H. Exact calculation of loop formation probability identifies folding motifs in RNA secondary structures. RNA 22, 1808–1818 (2016).

Szikszai, M. et al. RNA3DB: A structurally-dissimilar dataset split for training and benchmarking deep learning models for RNA structure prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 436, 168552 (2024).

Sun, S., Wang, W., Peng, Z. & Yang, J. RNA inter-nucleotide 3D closeness prediction by deep residual neural networks. Bioinformatics 37, 1093–1098 (2021).

Sample, P. J. et al. Human 5′ UTR design and variant effect prediction from a massively parallel translation assay. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 803–809 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. PrismNet: predicting protein–RNA interaction using in vivo RNA structural information. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, gkad353 (2023).

Noviello, T. M. R., Ceccarelli, F., Ceccarelli, M. & Cerulo, L. Deep learning predicts short non-coding RNA functions from only raw sequence data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008415 (2020).

Jaganathan, K. et al. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell 176, 535–548.e24 (2019).

Scalzitti, N. et al. Spliceator: multi-species splice site prediction using convolutional neural networks. BMC Bioinform 22, 561 (2021).

Ren, Y. et al. Beacon: Benchmark for comprehensive rna tasks and language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 92891–92921 (2024).

Bogard, N., Linder, J., Rosenberg, A. B. & Seelig, G. A deep neural network for predicting and engineering alternative polyadenylation. Cell 178, 91–106.e23 (2019).

Li, W. & Godzik, A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659 (2006).

Ott, M. et al. fairseq: A Fast, Extensible Toolkit for Sequence Modeling. In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT 2019: Demonstrations 48–53 (2019).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (1997).

Zhang, Z. pretrain datasets for ERNIE-RNA. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28034282.v1 (2024).

Zhang, Z. RNA3DB-2D dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30144502.v1 (2025).

Yin, W., Zhang, Z.& Zhang, S. ERNIE-RNA. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30171313.v2 (2025).

Zhang, Z. RNA3DB-2D-Structures. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30171316.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank members of Xie lab for helpful discussions. This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32341014 [Z.X.]), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFC2302401 [G.L.], 2019YFA0906103 [Z.X.]), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. Z230015 [Z.X.]), and Beijing National Research Center for Information Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X., W.Y. and Z.Z. conceived of the ideas implemented in this project. W.Y. and L.H. designed the ERNIE-RNA models. W.Y. carried out model pre-training. Z.Z., W.Y., S.Z., J.W., and R.Z. performed the downstream experiments. Z.Z., X.Z., T.Q. and L.H. analyzed the results, R.J., G.L. and J.W. assisted with analysis. Z.X. supervised the project. Z.X., Z.Z., W.Y. and L.H. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Z.X. and W.Y., as the inventors, have filed a patent application to the State Intellectual Property Office of China based on the presented work [202410262527.5]. Tsinghua University is the patent applicant. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Silvi Rouskin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions