Abstract

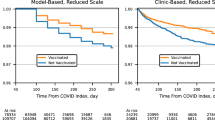

Longitudinal trajectories of Long COVID remain ill-defined, yet are critically needed to advance clinical trials, patient care, and public health initiatives for millions of individuals with this condition. Long COVID trajectories were determined prospectively among 3,659 participants (69% female; 99.6% Omicron era) in the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) Adult Cohort. Finite mixture modeling was used to identify distinct longitudinal profiles based on a Long COVID research index measured 3 to 15 months after infection. Eight longitudinal profiles were identified. Overall, 195 (5%) had persistently high Long COVID symptom burden, 443 (12%) had non-resolving, intermittently high symptom burden, and 526 (14%) did not meet criteria for Long COVID at 3 months but had increasing symptoms by 15 months, suggestive of distinct pathophysiologic features. At 3 months, 377 (10%) met the research index threshold for Long COVID. Of these, 175 (46%) had persistent Long COVID, 132 (35%) had moderate symptoms, and 70 (19%) appeared to recover. Identification of these Long COVID symptom trajectories is critically important for targeting enrollment for future studies of pathophysiologic mechanisms, preventive strategies, clinical trials and treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long COVID was recently defined by a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee as an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems1,2. This definition incorporates the possibilities of several distinct trajectories for Long COVID, yet these trajectories remain poorly defined. Millions of patients have experienced Long COVID, with a prevalence in adults estimated to be approximately 6% post-infection, with roughly a quarter of those with Long COVID experiencing significant activity limitations3,4. Patients experience Long COVID as a wide range of symptoms of variable severity with an unpredictable clinical course. In addition, healthcare providers face significant diagnostic challenges because many Long COVID symptoms are non-specific and can be present in uninfected persons or recovered SARS-CoV-2-infected patients without clear evidence of Long COVID. There is an urgent need to define the differing Long COVID trajectories to inform clinical trials and other investigations into the pathogenesis and treatment of persistent symptoms, as well as to determine the resources required for clinical and public health support of individuals with Long COVID and their providers.

To address this important global health priority, the National Institutes of Health established the Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) initiative (https://recovercovid.org/). The RECOVER Adult cohort includes a large subgroup of participants who were prospectively followed from the acute phase of their first SARS-CoV-2 infection, including participants who enrolled as uninfected and were infected during the study5. To provide a rigorous assessment of disease presence and capture the heterogeneity of Long COVID-associated symptoms, a quantitative research index for Long COVID was developed based on specific self-reported symptoms using standardized questionnaires developed with input from patient representatives6,7. Here, using this index, we report Long COVID trajectories among the RECOVER Adult participants observed since acute infection, and describe the notable features and prevalence of these trajectories.

Results

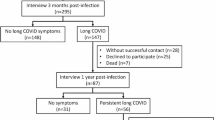

There were 4323 participants in RECOVER Adult who were followed prospectively from their first infection and were expected to have 15 months of follow-up data from that point. Enrollment dates ranged from October 29, 2021 to June 27, 2023 (Supplementary Table 1). The analysis cohort included 3659 participants (3280 acute, defined as those who enrolled within 30 days of their first SARS-CoV-2 infection, and 379 crossovers, defined as those who enrolled as uninfected and subsequently experienced their first SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 1), who met inclusion criteria. Participants were mostly female (69%), infected in the Omicron variant era (99.6%), and did not require hospitalization (98%) (Table 1). Of 3644 participants, 374 (10.3%) met symptom criteria for Long COVID (that is, had a Long COVID Research Index [LCRI] of at least 116) at 3 months and 324/2970 (10.9%) met criteria at 15 months after first SARS-CoV-2 infection, after excluding participants in the active phase of a reinfection or with a missing symptom survey at the corresponding visit (Fig. 2).

Participants in the analysis cohort are followed from their 3 month visit after first SARS-CoV-2 infection into the following categories: Long COVID (meeting LCRI threshold of 11), LC Unspecified (not meeting LCRI threshold of 11), and active reinfection (symptom survey completed within 30 days of a reported on-study reinfection). Between 6 and 15 months, participants not meeting the LCRI threshold of 11 are stratified further into those who had LC at a prior visit included in the diagram (“Unspec-Prior LC”) and those who did not (“Unspec-No Prior LC”). Participants may also be categorized as “Missed”, meaning they do not have symptom survey data at that visit (but may have symptom survey data at later visits). LC Long COVID, LCRI Long COVID Research index, Unspec unspecified.

The proportion of participants missing symptom data at visit months 6–15 ranged between 8 and 16% for each visit (Supplementary Table 2). Over two-thirds (68%) of participants had data measured at all 5 visits, 18% had data at 4 visits, 9% had data at 3 visits, and 4% had data at only 2 visits. Missed visit rates were consistent across LCRI strata at the prior visit, except for those with the highest LCRI (20–30), who were more likely to miss the next visit.

Eight distinct profiles were identified (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). Profile A (n = 195, 5%) generally described participants who met the threshold for Long COVID across all visits (“persistent, high symptom burden”). This profile described almost all participants with a very high LCRI at 3 months. Profile B (n = 443, 12%) described participants whose LCRI fluctuated around 9, intermittently meeting the threshold for Long COVID (“intermittently high symptom burden”). Profile C (n = 379, 10%) described participants whose LCRI decreased over time (“improving, moderate symptom burden”). Profile D (n = 334, 9%) described participants whose LCRI was on average lower than profile C at 3 months and decreased, mostly to 0, by 6 months (“improving, low symptom burden”). Profile E (n = 309, 8%) described participants whose LCRI gradually increased over time (“worsening, moderate symptom burden”). Profile F (n = 217, 6%) described participants whose LCRI was very low between months 3 and 12 but increased at month 15, driven in part by an increase in the presence of post-exertional malaise (“delayed worsening symptom burden”). Profile G (n = 481, 13%) described participants who have generally low LCRI, with some intermittently higher between 3 and 15 months that usually did not reach the Long COVID threshold (“consistent, low symptom burden”). Finally, profile H (n = 1301, 36%) described participants who never met the threshold for Long COVID (“consistent, minimal to no symptom burden”).

Finite mixture models were used to identify distinct trajectories of the Long COVID Research Index between 3 and 15 months after the first SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median (solid black line) and individual trajectories (solid colored lines) are shown for the 8 longitudinal profiles (A–H) identified. The Long COVID Research Index threshold of 11 is provided (dashed line). The Long COVID symptom burden of the profiles are described as follows: A, persistent, high; B, intermittently high; C, improving, moderate; D, improving, low; E, worsening, moderate; F, delayed worsening; G, consistent, low; H, consistent, minimal to none.

Participants with persistent, high symptom burden (profile A) compared to participants with consistent, minimal to no symptom burden (profile H) were more often female (77 vs. 64%) and hospitalized during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (6 vs 1%; Table 2). Overall, 36% of participants reported on-study reinfections by 15 months, ranging from 31 to 40% by profile. The reinfection rates in the worsening profiles (E and F), 39 and 40%, were marginally higher than other profiles. The proportion of participants who met the Long COVID threshold at each visit in each profile is shown in Supplementary Table 4. The frequency of individual symptoms at 3 and 15 months, by profile, is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The distribution of longitudinal profiles is provided, stratified by acute versus crossover status (Supplementary Table 5) and by referral source (Supplementary Table 6).

Among the 377 participants who met the Long COVID threshold at 3 months, there were 175 (46%) in the persistent high symptom burden group (profile A), 132 (35%) in the intermittently high symptom burden group (profile B), 66 (18%) in the improving, moderate symptom burden group (profile C), 4 (1%) in the improving, low symptom burden group (profile D), and 0 (0%) in the remaining groups. Individual trajectories are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The continually uninfected cohort included 1306 participants. Demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort are provided in Supplementary Table 7 with a summary of missing data in Supplementary Table 8. After multiple imputation, 3.1% met criteria for Long COVID at enrollment, 4.9% at 3 months, 4.9% at 6 months, 6.4% at 9 months, and 5.2% at 12 months. The most common profiles, in descending order, of the continually uninfected cohort were profile H (n = 632, 48%), G (n = 247, 20%), E (n = 105, 8%), C (n = 85, 7%), B (n = 72, 6%), F (n = 72, 6%), D (n = 65, 5%), and A (n = 18, 1%) (Supplementary Table 9).

Discussion

In this large, prospective, longitudinal analysis of participants enrolled in the RECOVER Adult cohort, we identified multiple post-infection trajectories capturing distinct patterns of symptom burden. We found 5% of infected participants persistently met the threshold for Long COVID for 15 months, and an additional 12% of participants had an intermittently high burden of Long COVID-related symptoms that did not improve over time. Among the 10% of participants who met research index criteria for Long COVID at 3 months, 46% were in the persistent Long COVID group, 35% continued to have intermittent Long COVID-related symptoms, and 19% were in the group that was improving over time. The latter group had an encouraging trajectory of improvement in symptom burden over 15 months, with the majority of the improvement occurring over the course of the first few months.

In contrast, we observed some participants (14%) whose LCRI increased over time (profiles E and F). There was a comparable proportion of reinfections in these individuals relative to other trajectory profiles, suggesting that this increase in their LCRI may not be explained by newly developed Long COVID after reinfection. Additional possibilities for this rise in LCRI include increasing clinical symptoms from a delayed pathophysiologic process8 or an intercurrent illness not related to Long COVID, though biological measures were not directly assessed in this study. When compared to a continually uninfected cohort, we observed a lower frequency of participants with symptom profiles A–D, which includes all profiles with persistent or improving symptoms, but a similar frequency of profile E (worsening, moderate), and so it is possible that profile E may ultimately be unrelated to Long COVID.

A notable design strength of the RECOVER study is the inclusion of frequent serial measurements over time since initial infection from a population-based cohort. This design allowed us to apply finite mixture models for longitudinal data, an unbiased approach to characterizing distinct longitudinal profiles with additional robustness properties against overfitting9. The observed eight longitudinal trajectories were heterogeneous across profiles, which is consistent with the reported clinical patient experience1. Of note, earlier studies found similarly high rates of persistence and low rates of complete recovery10,11,12. Very few studies of Long COVID have attempted to classify individuals into trajectory groups. A province-wide 18-month prospective study in Quebec found three main trajectories: a group with persistent poor quality of life; a group with average and stable quality of life scores, and a group with very high and stable quality of life scores13. A study in New York City prospectively followed for 2 years found five physical health trajectories and four mental health trajectories14.

Additional strengths of this study include its large size, representative population, the very detailed symptom questionnaire, a standardized and robust Long COVID index, and minimal loss to follow-up. There are also some limitations. The 10% prevalence of Long COVID in this study was lower than earlier eras with pre-Omicron variants and limited vaccination15. In addition, our findings may not reflect the trajectories of individuals with Long COVID who were infected in earlier eras and may not be fully representative of the general population. While community outreach efforts, which included television, radio, and social media advertisements, increased the diversity of the recruited cohort, it was not possible to quantify the number of individuals who were “approached” to enroll into RECOVER but declined, making it difficult to generalize our findings to all individuals with Long COVID or SARS-CoV-2 infection. There may have also been more granular, day-to-day changes in symptoms that were not captured by surveys that were administered only every 3 months. Moreover, our study was not designed to look at trajectories of individual symptoms as reported by others for up to 3 years of follow-up16. Although 86% of participants attended at least 4 of 5 visits, we did observe slightly higher loss to follow-up among participants with the highest LCRI, making it possible that we are under or overestimating recovery. It is possible that some participants experiencing more debilitating symptoms were less likely to complete subsequent symptom surveys due to exhaustion or fatigue, which has been observed in other studies related to chronic fatigue17. Finally, we did not have sufficient data after 15 months of follow-up to conduct robust analyses of the longer-term trajectory; this will be an important focus of future work. A larger sample size may have also revealed even subtler differences within the eight identified trajectories, resulting in a greater number of profiles.

The present study was intended to describe the natural history of Long COVID. The variability across individual-level trajectories will enable future studies to evaluate risk factors and biomarkers from biological samples that could predict future outcomes and explain differences in time to recovery, and identify potential therapeutic targets. Time-varying exposures can also be incorporated into future analyses, providing additional clues to potentially tractable factors impacting the trajectory over time. These findings will also provide vital information for well-designed interventional clinical trials and for clinicians and public health agencies in support of Long COVID patients.

In summary, we found that among individuals with a known history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, 5% had a profile characterized by a persistently high Long COVID-related symptom burden and an additional 12% had an intermittently high burden of symptoms that did not improve over time. Among the 10% of participants who developed Long COVID based on the research index threshold at 3 months after their first infection, the majority had persistent or intermittent symptoms, while 19% showed improvement over the subsequent year. These subgroups will be critically important to target enrollment for future studies of pathophysiologic mechanisms, preventive strategies, and treatments.

Methods

Study cohort

RECOVER Adult is an ongoing, prospective observational cohort study of adults in the US, with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection, who were enrolled at 83 sites (hospitals, health centers, community organizations) located in 33 states plus Washington, DC and Puerto Rico5. Study participant selection included population-based, volunteer, and convenience sampling. Participants complete symptom surveys every 3 months. All participants provided written informed consent at enrollment. The NYU Langone Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study, which served as a single IRB for almost all sites, while some sites required approval by the local IRB (Supplementary Table 10).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To facilitate longitudinal analysis from the time of first SARS-CoV-2 infection (“index date”), RECOVER Adult acute and crossover participants were included. Symptom surveys were completed at visits 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months after the index date. Only participants expected to have a 15-month visit by the end of the study period (September 6, 2024) were included. Participants without 3-month symptom survey data and participants with no symptom survey data between 6 and 15 months were excluded.

A comparator cohort was constructed with participants that remained continually uninfected (i.e., no reported history of infection at enrollment through the 12-month visit after enrollment). This mirrors the 12 months that elapsed during follow-up for the infected cohort, beginning at 3 months and ending at 15 months. We excluded uninfected participants who did not complete any symptom surveys between their scheduled 3- and 12-month visits.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the 2024 LCRI, a weighted sum based on the presence or absence of 11 symptoms that include severity measures at the time of the symptom survey6. LCRI (range 0–30; higher scores indicate greater symptom burden) was calculated at every study visit. Participants with a LCRI ≥ 11 (i.e., highly symptomatic) were classified as having Long COVID.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized, including the amount of missing data, using descriptive statistics. An alluvial (Sankey) diagram was generated to visualize Long COVID status over time across study visits. This was further stratified by prior state (Long COVID at some prior visit, not meeting the Long COVID threshold previously). Other strata at each time point included those with active reinfections (survey completed within 30 days of reinfection) and those who missed the symptom survey at that time point. The proportions of participants attending their next scheduled visit by LCRI (0, 1–10, 11–19, 20–30) were reported.

Finite mixture models for longitudinal data using the expectation-maximization algorithm were used to identify distinct longitudinal profiles using the LCRI as a Poisson-distributed continuous outcome variable9. To account for missing LCRI due to missing symptom survey data, multiple imputation with random intercepts was used under the assumption that the data are missing at random, conditional on age, sex, race/ethnicity, referral type, hospitalization status at the time of 1st infection, vaccination status at 1st infection, and multiple social determinants of health and comorbidities18,19. Full details of the imputation and profiling approach are provided in the Supplementary Methods. The averaged Bayesian Information Criterion was used to identify the optimal number of profiles across the imputed datasets. A consensus-based approach was used to assign individuals to profiles while averaging over the profiling results from the imputed datasets20. Demographic and clinical characteristics, including the proportion reinfected by 15 months, were summarized by profile. In the subgroup analysis, the trajectories of participants with Long COVID at 3 months were characterized. The distribution of originally assigned profiles for these participants was reported, and individual trajectories were visualized. Finally, in the continually uninfected cohort, the proportion of participants with LCRI ≥ 11 at each visit was reported. Participants were assigned to the profiles they most closely resemble based on Euclidean distance, without repeating the group trajectory modeling analysis. Multiple imputation was used to address missing data in this cohort with the same covariates.

Analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.021. Additional information on specific R packages used can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RECOVER Adult Cohort Observational Study is in progress, and the datasets are updated dynamically. NHLBI has undertaken a significant effort to release harmonized data from all RECOVER observational cohort studies to the public via their BioData Catalyst platform (https://biodatacatalyst.nhlbi.nih.gov/recover). Data, including source data for all results, are available as of April 25, 2024 for researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved for a specified scientific purpose and after approval of a proposal and with a signed data access agreement.

Code availability

For reproducibility, our code is available on Git (https://github.com/mgb-recover-drc/recover-nbr-public/tree/main/adult/manuscripts/trajectories)22.

References

Ely, E. W., Brown, L. M. & Fineberg, H. V. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine Committee on Examining the Working Definition for Long Covid. Long Covid Defined. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1746–1753 (2024).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine. A Long COVID Definition: a Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences (The National Academies Press, 2024).

Ford, N. D. et al. Long COVID and significant activity limitation among adults, by age-United States, June 1–13, 2022, to June 7–19, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 72, 866–870 (2023).

Hastie, C. E. et al. True prevalence of long-COVID in a nationwide population cohort study. Nat. Commun. 14, 7892 (2023).

Horwitz, L. I. et al. Researching COVID to enhance recovery (RECOVER) adult study protocol: rationale, objectives, and design. PLoS ONE 18, e0286297 (2023).

Geng, L. N. et al. 2024 Update of the RECOVER-Adult Long COVID Research Index. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.24184 (2024).

Thaweethai, T. et al. Development of a definition of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA 329, 1934–1946 (2023).

Peluso, M. J. & Deeks, S. G. Mechanisms of long COVID and the path toward therapeutics. Cell 187, 5500–5529 (2024).

Grün, B. & Leisch, F. FlexMix version 2: finite mixtures with concomitant variables and varying and constant parameters. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–35 (2008).

Agergaard, J., Gunst, J. D., Schiottz-Christensen, B., Ostergaard, L. & Wejse, C. Long-term prognosis at 1.5 years after infection with wild-type strain of SARS-CoV-2 and alpha, delta, as well as Omicron variants. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 137, 126–133 (2023).

Huang, L. et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 863–876 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Two- and 3-year outcomes in convalescent individuals with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 96, e29566 (2024).

Tanguay, P. et al. Trajectories of health-related quality of life and their predictors in adult COVID-19 survivors: a longitudinal analysis of the Biobanque quebecoise de la COVID-19 (BQC-19). Qual. Life Res. 32, 2707–2717 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Examining the trajectory of health-related quality of life among coronavirus disease patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 39, 1820–1827 (2024).

Xie, Y., Choi, T. & Al-Aly, Z. Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the pre-delta, delta, and Omicron eras. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 515–525 (2024).

Cai, M., Xie, Y., Topol, E. J. & Al-Aly, Z. Three-year outcomes of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 30, 1564–1573 (2024).

van Amelsvoort, L. G., Beurskens, A. J., Kant, I. & Swaen, G. M. The effect of non-random loss to follow-up on group mean estimates in a longitudinal study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19, 15–23 (2004).

Grund, S., Lüdtke, O. & Robitzsch, A. Multiple imputation of missing data for multilevel models: simulations and recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 21, 111–149 (2018).

Spratt, M. et al. Strategies for multiple imputation in longitudinal studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 478–487 (2010).

Basagana, X., Barrera-Gomez, J., Benet, M., Anto, J. M. & Garcia-Aymerich, J. A framework for multiple imputation in cluster analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 177, 718–725 (2013).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org (2024).

Shinnick, D. J. & Thaweethai, T. Long COVID trajectories in the prospectively followed RECOVER-Adult US cohort, mgb-recover-drc/recover-nbr-public: NBR v1.0.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17107785 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the national community engagement group, caregivers, community representatives, and the participants enrolled in the RECOVER Initiative. The members of the RECOVER-Adult Consortium are provided in a Supplementary File. This research was funded by grants OTA OT2HL161841, OT2HL161847, OT2HL156812, and OT2HL162087 from the NIH as part of RECOVER. Additional support for T.T., A.S.F., and B.D.L. was provided by grant R01 HL162373. Additional support for J.D.T. was provided by VA Merit Award I01RX003810.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Authorship was determined using ICMJE recommendations. T.T., S.E.D., J.N.M., D.J.S., L.H., A.S.F., and B.D.L. developed the study protocol and analysis plan. T.T., D.S., and A.S.F. accessed, verified, and analyzed the data. T.T., S.E.D., J.N.M., M.H., J.M.M., D.J.S., L.H., A.S.F., and B.D.L. interpreted the data and results. T.T., S.E.D., D.J.S., L.H., A.S.F., and B.D.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors (T.T., S.E.D., J.N.M., M.H., J.M.M., D.J.S., H.A., O.A., A.B., H.B., Y.C., M.M.C., N.B.E., V.F., P.G., J.D.G., N.M.H., J.E.H., J.R.H., V.J., S.E.J., J.D.K., S.W.K., C.K., J.A.K., R.L., E.B.L., M.E.M., G.A.M., T.D.M., J.M.M., I.O., M.J.O., C.C.P., T.F.P., M.J.P., R.R., Z.A.S., H.N.S., C.S., U.S., B.S.T., B.D.T., J.D.T., A.B.T., P.J.U., A.J.V., E.W., Z.W., J.W., L.M.Y., L.H., A.S.F., and B.D.L.) edited the manuscript. T.T. and A.S.F. had access to the data. All authors (T.T., S.E.D., J.N.M., M.H., J.M.M., D.J.S., H.A., O.A., A.B., H.B., Y.C., M.M.C., N.B.E., V.F., P.G., J.D.G., N.M.H., J.E.H., J.R.H., V.J., S.E.J., J.D.K., S.W.K., C.K., J.A.K., R.L., E.B.L., M.E.M., G.A.M., T.D.M., J.M.M., I.O., M.J.O., C.C.P., T.F.P., M.J.P., R.R., Z.A.S., H.N.S., C.S., U.S., B.S.T., B.D.T., J.D.T., A.B.T., P.J.U., A.J.V., E.W., Z.W., J.W., L.M.Y., L.H., A.S.F., and B.D.L.) accepted responsibility for submitting the article for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.D.G. reports grants from Gilead; and serving as a speaker, consultant or advisory board member for Gilead, Merck, and Ivivyd related to Long COVID, outside the submitted work. M.J.P. has received consulting fees related to Long COVID from Gilead Sciences, AstraZeneca, BioVie, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, and BioNTech, travel support from Invivyd, and research support from Aerium Therapeutics and Shionogi, outside the submitted work. J.W. has received funding from Regeneron for a study assessing the immune response to covid infection and vaccination among immunosuppressed patients and consulted and was an author on a meta-analysis of the impact of vaccination on the prevention of Long COVID for BioNTech. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lauren O’Mahoney and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thaweethai, T., Donohue, S.E., Martin, J.N. et al. Long COVID trajectories in the prospectively followed RECOVER-Adult US cohort. Nat Commun 16, 9557 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65239-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65239-4