Abstract

Pd-based materials are among the best electrocatalysts with high CO2-to-formate selectivity at near-equilibrium potential. However, the efficiency of Pd is severely hindered by its deactivation at elevated overpotentials, resulting in limited formate production activity within a narrow potential window. Herein, by constructing a palladium/fullerene (PdC60) composite catalyst, we achieve improved activity towards formate production and enhanced resistance to deactivation at high overpotentials. As a result, the PdC60 composite achieves practically relevant current density of 250 mA cm−2 in 4 cm2 membrane electrode assembly reactor with a modest cell voltage of 1.71 V, along with the energy efficiency up to 72% towards formate, demonstrating its promise for future implementation. Mechanistically, we pinpoint the enhanced performance of PdC60 to the profound interfacial charge transfer from Pd to C60 substrate, which suppresses Pd-H phase transition and alleviates CO poisoning during catalysis. Overall, our discoveries shed light on the complex potential-dependent interplays between the phase evolution of Pd-based catalysts and CO2 electroreduction performance, highlighting its promise for energy-efficient CO2 conversion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (CO2R) coupled with renewable energies is recognized as a promising approach for producing important chemical feedstocks. Among different products, formate attracts significant attention due to its promising technological and economic prospects, including energy storage, green fuel production, and cost-effective synthesis of value-added chemicals1,2,3. With regard to catalyst candidates, Pd-based materials are known for achieving high formate selectivity and activity at near-equilibrium potential4,5. For instance, at a small cathodic potential of −0.1 V (all electrode potentials mentioned here are versus the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), unless otherwise defined), 3.7 nm Pd nanoparticles (NPs) exhibit high formate Faradaic efficiency (FE) up to 93% and partial current density (jFormate) of 4.5 mA cm−2 6. By contrast, the formate onset potentials (where jFormate reaches 0.1 mA cm−2) on Sn- and Bi-based electrocatalyst (common CO2R to formate catalysts), are as negative as −0.6 V with limited selectivity ~65%7, resulting in unsatisfactory energy efficiency8,9. Unfortunately, despite its advantages, both the high activity and selectivity of Pd-based catalysts are quickly compromised at elevated cathodic potentials due to catalyst deactivation10. Specifically, starting from a modest cathodic potential of ~ −0.3 V, the reaction selectivity shifts to H2 and CO formation with several times lower current densities11,12,13. Additionally, even with moderate cathodic potentials applied, the stability of state-of-the-art Pd catalysts in CO2R electrolysis is often limited to a few minutes14,15. Two major factors account for the deactivation. First, increasing cathodic potential drives the phase transition from α-PdHx (surface hydride, covalent Pd-H bond, x < 0.03) to β-PdHx (bulk hydride, metallic Pd-H bond, x > 0.6)16. This phase transition substantially reduces both selectivity and activity towards formate17. Second, the strong affinity of CO on the Pd surface renders the Pd active sites highly susceptible to poisoning by CO originated from CO2R and prone to catalyst deactivation13,18,19,20. Since these potential-dependent phase/performance evolutions undermine superior performance of Pd catalysts, the need of overcoming Pd deactivation during CO2R is required to enable selective and energy-efficient formate production technologies. Moreover, although the aforementioned Pd-H phase transition and CO poisoning are thought to be possible contributors to Pd deactivation during CO2R13,16,21, the specific interplay between these two factors remains elusive, stressing the need of further exploration to unlock the detailed potential-driven evolution process in Pd-based catalysts.

Previous studies suggested that Pd deactivation can be mitigated by stabilizing Pdδ+ state during CO2R22. Here, we leverage the unique properties of C60 (fullerene), a well-known electron acceptor with a stable anionic state (C60−), π-electron structure, and high electrical conductivity, to induce Pdδ+ via interfacial charge transfer23,24. By constructing a Pd/C60 heterointerface25,26, the pronounced interfacial charge transfer occurs, as confirmed by multiple characterizations. As a result, the PdC60 catalyst delivers substantially enhanced CO2-to-formate activity, selectivity, and stability over an extended potential window, outperforming pristine Pd catalysts. Specifically, nearly 100% formate selectivity is retained until −0.6 V at formate partial current density (jFormate) > 25 mA cm−2, along with appreciable stability, which is competitive with state-of-the-art Pd-based electrocatalysts5,6,15,27,28,29. Moreover, practically relevant current density of 250 mA cm−2 is reached in 4 cm2 membrane electrode assembly (MEA) reactor with a modest cell voltage of 1.71 V, resulting in the full-cell energy efficiency of over 72% towards formate production.

Importantly, the catalyst resistance to Pd-H phase transition and CO poisoning is strengthened on PdC60 catalyst, as revealed by detailed kinetic and mechanistic investigations. Consequently, PdC60 demonstrates high activity and selectivity for CO2R across an extended potential window. Notably, this extended potential window allows us to comprehensively uncover the potential-dependent Pd evolution during CO2R. Specifically, while increasing cathodic potential promotes both Pd hydride formation and surface CO formation, the Pd-H phase transition induces the switching of *CO adsorption configuration, exacerbating CO formation and leading to severe CO poisoning of Pd surfaces. Overall, our studies provide insights into the complex potential-dependent interplays between the phase transitions in Pd catalysts and their CO2 electroreduction performance, and demonstrate the feasibility of Pd-based catalyst for energy-efficient CO2 conversion at high current.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of PdC60 catalyst

The PdC60 model catalyst was prepared via a facile one-step deposition of Pd nanoparticles onto a crystallized C60 substrate prepared through liquid-liquid interface precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 1a)25,30,31. We first confirmed the formation of C60 crystals by transmission electron microscope (TEM), which revealed their ~500 nm size (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c) and high crystallinity validated by the fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern (Supplementary Fig. 1c inset). The obtained C60 crystal was subsequently used as the substrate for Pd deposition. The successful synthesis of the desired PdC60 composite was confirmed by transmission electron microscope (TEM). As shown in Fig. 1a, Pd nanoparticles with an average size of approximately 5 nm are evenly dispersed on the C60 substrate. Its lattice structure was further analyzed by the selected area diffraction (SAD) (Fig. 1a inset) and high-resolution TEM (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, the retention of C60 (111) plane in PdC60 composite (Fig. 1c) demonstrated the preserved crystallinity of C60 substrate after Pd deposition. Additionally, the uniform spatial distribution of Pd and C elements in the TEM-EDS mapping (Fig. 1d) further validates the formation of a desirable and intimate Pd/C60 interface.

a TEM image of PdC60 and SAD of the inset region. High-resolution TEM of b Pd particles and c C60 substrate in PdC60. d EDS mapping images of PdC60. e Pd 3d XPS and f estimated ratio of Pdδ+ species within PdC60, PdC and pristine PdNPs after CO2R, demonstrating the increased Pdδ+ ratio of PdC60. g In situ Pd K-edge XANES of PdC60 and standard reference samples (Pd foil, PdC, and PdO). h The rising edge of in situ Pd K-edge XANES of the selected region in (g), showing the presence of Pdδ+ under catalytic conditions. The in situ XANES experiment was conducted at 25 °C and with 1 M KOH as the electrolyte (pH = 14.05 ± 0.02). 100% iR compensation was applied for all cathodic potentials. Typical solution resistance for 1 M KOH was measured to be 2.1 Ω ± 0.3 Ω. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

To elucidate the structure-performance relationship, two reference catalysts were prepared: PdC (PdNPs dispersed on carbon black) and pristine PdNPs. The morphology, facets, particle size, and roughness factors of PdC60 and the benchmark catalysts were systematically assessed and compared using powder X-Ray Diffraction spectroscopy (PXRD), TEM, and electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) analysis, respectively. The results showed no significant differences across the different samples, excluding any major impact from the abovementioned parameters on the subsequent catalytic performance (Supplementary Fig. 2). Metal loadings were determined by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), showing Pd mass ratios of 44.0%, 46.5%, 99.9% for PdC60, PdC, and PdNPs, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). Meanwhile, the aforementioned structural properties remained stable after CO2R at different overpotentials, ruling out any major influence of surface morphology evolution on the observed catalytic performance (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). Additionally, ICP-OES analysis confirmed the absence of Pd2+ in electrolyte after CO2R, further confirming structural stability of all considered Pd-based catalysts (Supplementary Table 2).

Next, the potential interfacial charge transfer between Pd and C60 substrate was first probed by Pd 3d X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Across all samples, the spectra revealed predominant metallic Pd species (335.6/340.9 eV) accompanied by a minor fraction of Pdδ+ species (337.4/342.7 eV), as shown in Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 732,33,34. To quantify the extent of charge transfer, the ratio of Pdδ+ to all Pd species was estimated for the three samples. As expected, PdC60 exhibits a substantially higher Pdδ+ ratio of 0.18 compared to the control samples, indicating significant charge transfer at the Pd/C60 interface (Fig. 1f). Although prominent interfacial charge transfer was evidenced by Pd 3d XPS, the presence of Pdδ+ under catalytic conditions warrants further exploration. To monitor the valence state of Pd during CO2R, in situ X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) measurements at the Pd K-edge were performed in a flow cell (detailed in Supplementary Note 1). As shown in Fig. 1g, the in situ XANES results further confirmed the notable presence of Pdδ+ species in PdC60, as indicated by the energy of the rising edge (Fig. 1h), highlighting the prominent charge transfer at the Pd/C60 interface. A profound contrast was evidenced by XANES results of PdC, which exhibit metallic Pd state, as indicated by the rising edge position closely matching that of Pd foil (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of Pd K-edge results showed that the local structure of Pd particles on C60 resembles that of Pd foil with an identical R (Å) of Pd-Pd path, but a reduced coordination number (CN), revealing the smaller Pd particle size (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, in situ EXAFS shows that the average CN and R (Å) of Pd-Pd path were retained under the cathodic potential of CO2R, indicating the structural stability of the catalyst composite during catalysis (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 4).

To conclude, we successfully constructed a structurally stable PdC60 catalyst composite, with a uniform distribution of small PdNPs on well-maintained C60 crystal substrates. Importantly, the significant interfacial charge transfer within PdC60 catalyst was evidenced by XPS and in situ XANES, highlighting its potential for promoting CO2-to-formate reactivity.

Energy-efficient electrochemical CO2 reduction to formate on PdC60

We first evaluated the CO2R performance of PdC60 and the benchmark in a typical H-type cell. As depicted in Fig. 2a, nearly 100% selectivity towards formate was achieved on PdC60 catalysts across a wide potential window until −0.6 V, achieving an improved current density up to 25 mA cm−2. To benchmark its activity, we compared its performance with that of PdC, PdCNT (PdNPs dispersed on carbon nanotubes), and pristine PdNPs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 5, PdC60 exhibits enhanced jFormate across a wide cathodic potential window, outperforming the reference samples. PdC60 is also comparable to state-of-the-art Pd-based catalysts documented elsewhere under identical testing conditions (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 6)5,6,15,27,28,29,35, demonstrating the promising activity and selectivity for CO2-to-formate conversion over a broad cathodic potential region (up to −0.6 V). As mentioned before, the CO2R stability of conventional Pd-based catalysts is severely impeded by the inevitable deactivation at high overpotentials, leading to a rapid decline in both selectivity and current density14. Notably, PdC60 exhibits enhanced CO2R stability, evidenced by the continuous operation for 30 h at ~10 mA cm−2 with negligible loss in formate selectivity. In contrast, under the same applied cathodic potential, the current density of PdC dropped to below 1 mA cm−2 within 2 h, accompanied by a rapid increase in the rate of competing HER (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 7).

a FEs and current density of CO2R on PdC60 (1 mg cm−2) at various cathodic potentials in an H-type cell using CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 as the electrolyte (pH = 6.80 ± 0.05, CO2 flow rate = 20 sccm). The reaction was conducted at 25 °C. b jFormate of PdC60 and documented state-of-the-art catalysts on the function of cathodic potential in H-type cell. PdC60 demonstrates improved jFormate in an extended potential window. c Nyquist plots at −0.2 V in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 for PdC60, PdC and pristine PdNPs. d Fitted Rct and Rp by Z-view, indicating the facilitated reaction kinetics of PdC60. e CO2R performance of PdC60 (1 mg cm−2) assessed in 4 cm2 MEA reactor, with humified CO2 flowed through the cathode side (flow rate = 20 sccm) and 1 M KOH as the anolyte (pH = 14.05 ± 0.02, heated to 60 °C). f Full-cell energy efficiency of PdC60 and state-of-the-art electrocatalysts (Sn, Bi, and Pb-based) for CO2R to formate or formic acid. g Stability assessment of PdC60 and PdC (1 mg cm−2 for both) at 100 mA cm−2 in 4 cm2 MEA reactor, with humified CO2 flowed through the cathode side (flow rate = 20 sccm) and 1 M KOH as the anolyte (pH = 14.05 ± 0.02, heated to 60 °C). The error bars represent standard deviations from three independent measurements. Typical solution resistance for 0.1 M KHCO3 was measured to be 11.9 Ω ± 1.5 Ω. All potentials were corrected with 100% iR compensation, except for the cell voltage reported in the MEA measurement (e). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

To gain further insight into the reaction kinetics, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted under CO2R conditions (Fig. 2c). The EIS data fitting was based on the equivalent circuit in Fig. 2c inset. As shown in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 8, at a modest cathodic potential of −0.2 V, PdC60 exhibits a significantly reduced adsorption resistance (Rp, 17.9 Ω) compared to PdC and pristine PdNPs (39.5 and 37.5 Ω, respectively), indicating the accelerated CO2 adsorption on PdC6036,37. Additionally, the charge transfer resistance (Rct) on PdC60 is also noticeably decreased, suggesting facilitated desorption of the HCOO* intermediate38,39. These results collectively highlight the pivotal role of Pd/C60 interface in enhancing both activity and selectivity towards formate. To validate the critical role of the Pd/C60 interface in the enhanced CO2R performance, we prepared modified PdC60 catalyst samples (denoted as PdC60-1 and PdC60-2) with a reduced density of favorable Pd/C60 interfacial sites by accelerating Pd precipitations during synthesis. Additionally, we prepared a physical mixture of pristine PdNPs and C60 substrate as a control (PdC60-3). TEM images revealed uneven Pd dispersion in all three control samples (Supplementary Fig. 13). The ratios of Pdδ+ species in these control samples were estimated from the corresponding Pd 3d XPS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 14a). The results indicated significantly lower ratios of Pdδ+ species in these modified samples compared to PdC60, though still higher than those in PdC and PdNPs (Supplementary Fig. 14b). Then, the CO2R performances were measured and compared at −0.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 14c), demonstrating the inferior activity on modified samples compared to PdC60. A clear correlation between jFormate and Pdδ+ content across all samples was established (Supplementary Fig. 14d), providing strong evidence for the decisive role of the Pd/C60 interface in enhancing CO2-to-formate conversion.

Encouraged by the enhanced performance of PdC60 in the H-type cell, we then scaled up the CO2R in a gas diffusion layer (GDE)-based flow cell (Supplementary Fig. 15a) with 1 M KHCO3 as the electrolyte. PdC60 demonstrated a high current density of 100 mA cm−2 at −0.53 V with nearly 100% formate selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 15b and Supplementary Table 9) and showed appreciable stability (Supplementary Fig. 15c). In contrast, PdC reached only 5 mA cm−2 under identical conditions (Supplementary Fig. 15d, e). Under alkaline conditions (1 M KOH), PdC60 required only −0.24 V to reach 100 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 16a, b and Supplementary Table 10), corresponding to a high cathode energy efficiency (CEE) of 85%. Compared to state-of-the-art Sn- and Bi-based catalysts under similar conditions (Supplementary Fig. 16c and Supplementary Table 11)40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50, PdC60 operated at lower overpotentials, whereas these catalysts typically require −0.5 to −1.2 V to achieve comparable current densities, resulting in compromised energy efficiency29,51,52.

CO2R on PdC60 was further evaluated in a zero-gap membrane electrode assembly (MEA) reactor with electrode area of 4 cm2. The reaction was paired with oxygen evolution reaction (OER) as the anodic reaction, using NiFe-LDH as the anodic catalyst owing to its excellent alkaline OER activity (Supplementary Fig. 17)53,54,55,56. High formate selectivity (>95%) was confirmed by 1H NMR, based on quantitative analysis of the products collected from both the cathode and anode compartments, following documented protocols (Supplementary Fig. 18)40,57,58. Notably, a low cell voltage of 1.71 V was achieved at the current density of 250 mA cm−2 (Fig. 2e). The cell voltage distribution has been analyzed (Supplementary Note 2), suggesting an estimated overpotential of approximately −0.252 V for the cathodic CO2R. When benchmarking the performance against state-of-the-art CO2-to-formate electrocatalysts (Sn, Bi, and Pb-based) in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Table 1252,59,60,61,62,63 PdC60 exhibits a comparable full-cell energy efficiency (EE) up to 72%, underscoring its potential for applications. Moreover, PdC60 demonstrates enhanced CO2R stability in MEA, exhibiting stable operation for 8 h at 100 mA cm−2 with >90% selectivity and >80% full-cell energy efficiency towards formate (Fig. 2g).

In conclusion, PdC60 delivers enhanced CO2-to-formate activity and stability, enabled by the enhanced reaction kinetics at the Pd/C60 interface. Its improved performance in the MEA reactor further underscores its potential for energy-efficient CO2R implementations at industrially relevant current densities.

Suppressed deactivation during CO2R on PdC60 catalyst

Potential-driven catalyst deactivation remains a key challenge limiting the efficiency and durability of Pd-catalyzed CO2R. Therefore, elucidating the underlying deactivation mechanism is essential for advancing Pd-based catalysts and fully harnessing their high energy efficiency. To gain more mechanistic insights into this deactivation process, we first performed cathodic linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) for various catalyst candidates under identical CO2R conditions (Supplementary Fig. 19a). We tentatively divided the LSV curves into three regions based on the understanding from previous literature on Pd-based electrocatalysts6. Specifically, region Ⅰ corresponds to the CO2-to-formate kinetic region, exhibiting exponential growth in current density with increasing overpotential. In region Ⅱ, Pd deactivation occurs, as evidenced by a sharp decline in current density. Upon further cathodic polarization, region III emerges, where CO2R shifts toward CO production. By comparing the onset potentials for deactivation (defined by the beginning of region II, Supplementary Fig. 19b), it is evident that both PdC and pristine PdNPs exhibit a sharp current density drop at approximately −0.3 V. In contrast, PdC60 shows no obvious deactivation until −0.74 V, underscoring its significantly enhanced resistance to potential-driven deactivation.

Investigations of the Pd-H phase transition

To uncover the origin of the improved CO2R activity of PdC60, we turned our attention to the Pd-H phase transition, a critical cause of potential-driven Pd deactivation17. Due to the strong affinity between Pd and hydrogen64, α-PdH is expected to form readily under mild cathodic potentials, acting as the active phase for catalyzing CO2R to formate65,66,67. However, continued hydrogenation will drive the formation of β-PdH, resulting in CO2R deactivation and selectivity shift16,17,68,69. To track the Pd-H phase transition during CO2R, we performed in situ PXRD using a customized electrochemical cell (Supplementary Fig. 20)10,70. Formation of β-PdH is known to expand the Pd lattice, leading to a characteristic shift of PXRD peaks toward lower angles70,71. At open-circuit voltage, the PXRD patterns of PdC60 and PdC showed no deviation from as-prepared samples, with distinct Pd (111), (200), and (220) peaks (Supplementary Fig. 21). Upon applying cathodic potentials, the Pd (111) peak of PdC60 rapidly shifted from 40.1° to 39.1° at −0.6 V, indicating the transition to β-PdH (Fig. 3a). In contrast, a similar peak shift happened on PdC at a much smaller cathodic potential of −0.3 V (Fig. 3b), confirming its earlier phase transition. These observations support that the Pd/C60 interface stabilizes the active Pd-phase for CO2R, suppressing the transition to β-PdH and the following catalyst deactivation. Note that hydride formation in the Pd catalyst is reversed by increasing the potential back to the open-circuit condition (Supplementary Fig. 22)72. To reaffirm the critical role of the Pd-phase transition on CO2R, we plotted the XRD peak position of Pd (111) alongside the corresponding jFormate as the function of the cathodic potential applied for both PdC60 and PdC. A clear correlation is observed in Fig. 3c: the onset of Pd (111) peak shift coincides with a sharp drop in formate selectivity on both catalysts, confirming that the transition to β-PdH is a key factor driving CO2R deactivation. Compared to PdC with early phase transition at ~ −0.3 V, PdC60 presents favorable formate selectivity and suppressed phase transition until −0.6 V, highlighting its improved CO2R activity and compositional robustness. To further explore the intrinsic hydrogenation behavior of these Pd catalysts, we conducted hydrogen desorption/adsorption cyclic voltammograms (CVs). These experiments were conducted in Ar-saturated electrolyte to exclude any interference from CO2R and CO poisoning. As shown in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 23, hydrogen desorption and adsorption on PdC60 occur at significantly more cathodic potentials compared to PdC and pristine PdNPs under both neutral and alkaline conditions, indicating a markedly reduced tendency for Pd hydride formation on PdC6073,74,75,76.

In situ PXRD conducted in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 of a PdC60 and b PdC, and standard PXRD patterns of Pd and PdH. The rapid peak transition happens at ~ −0.6 V and −0.3 V, respectively. c Pd (111) peak position (black lines) of PdC60 and PdC, and the corresponding FEFormate (red lines) as the function of the cathodic potential. d H desorption CVs on PdC60, PdC and PdNPs in Ar-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 with the scan rate of 10 mV s−1. H desorption/adsorption on PdC60 occurs at less anodic potentials. The reactions were conducted at 25 °C. Typical solution resistance for 0.1 M KHCO3 was measured to be 11.9 Ω ± 1.5 Ω. 100% iR compensation was applied for all cathodic potentials. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Overall, these findings collectively demonstrate the unique capability of Pd/C60 interactions in suppressing Pd-H phase transition and deactivation during CO2R, which is essential for sustaining efficient and durable formate production. Moreover, the postponed phase transition on PdC60 extends the operational potential window for CO2-to-formate, enabling mechanistic investigations into Pd deactivation in the later discussion.

Investigations of the CO poisoning on Pd surface

Besides the Pd-H phase transition, CO poisoning is another major cause of Pd deactivation. Owing to the strong affinity of CO on Pd surfaces, the desorption of *CO intermediate is significantly hindered, resulting in active site blockage and catalyst poisoning19. Notably, the extent of CO poisoning is potential-dependent, as more cathodic potentials drive enhanced CO generation during CO2R and exacerbate surface poisoning14. To study this poisoning effect and to further delve into the improved performance of PdC60, we first carried out CO stripping measurements in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 (Supplementary Fig. 24), where anodic CVs were performed after potentiostatic CO2R electrolysis at various cathodic holding potentials (VHold). These CO stripping experiments on PdC60 revealed the characteristic potential-dependent CO poisoning behavior (Fig. 4a). At VHold of −0.4 V, negligible CO poisoning occurred, as evidenced by the absence of a discernible CO stripping peak. The onset of poisoning was observed at −0.6 V, where a new peak appeared at ~1.0 V, corresponding to CO stripping on α-PdH22,76. When VHold was further increased to −0.8 V, the CO stripping peak area increased significantly, indicating severe surface poisoning. Here, the distinct peak at approximately 0.8 V reflects CO stripping on β-PdH22,69,76,77,78. To validate the critical impact of CO poisoning on CO2R performance, we correlated the CO stripping peak area alongside the corresponding formate selectivity as a function of VHold (Fig. 4b). Specifically, we observed a sudden decrease in FEFormate from up to nearly 100% to below 60% from −0.6 V onward, where the drastic increase of the CO stripping peak appeared. The same detrimental effect of CO poisoning on Pd-catalyzed CO2R was also observed on PdC and PdNPs (Supplementary Fig. 25).

a Characteristic CO stripping CVs of PdC60 after 3 min of CO2R electrolysis at VHold of −0.4 V, −0.6 V and −0.8 V in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3, with the scan rate of 10 mV s−1. b The relationship between FEFormate and CO stripping peak areas at various VHold on PdC60. The abrupt decline in formate selectivity coincides with a pronounced surge in CO poisoning. c Normalized CO stripping peak area as a function of VHold across various catalysts. PdC60 exhibited a delayed onset of CO poisoning compared to PdC and PdNPs. In situ ATR-SEIRAS on d PdC60 and e PdC in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3. f Normalized *CO adsorption peak areas on PdC60 and PdC at varying cathodic potentials showing the postponed onset of *CO adsorption on PdC60. g Peak areas for CO on bridge and hollow sites (COB/H), CO on atop site (COA), and COB/H peak positions on PdC60 at varying cathodic potentials derived from (d). The region showing shifts in peak area and position is marked with a gray background. The reactions were conducted at 25 °C. Typical solution resistance for 0.1 M KHCO3 was measured to be 11.9 Ω ± 1.5 Ω. 100% iR compensation was applied for all cathodic potentials. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Building upon the above insights into the potential-dependent CO poisoning and its detrimental effect on CO2R, we systematically investigate how the CO poisoning evolves with the applied cathodic potential for CO2R across different catalysts, aiming to elucidate the origin of the improved CO2R performance of PdC60. When comparing results at VHold = −0.5 V, PdC60 exhibits a substantially smaller CO stripping peak area compared to the other two Pd catalysts, demonstrating its effective resistance towards CO poisoning (Supplementary Fig. 26a). Moreover, the CO stripping peak position of PdC60 was approximately 60 mV lower than those of PdC and PdNPs, indicating the weakened surface CO adsorption on the former (Supplementary Fig. 26b). When comparing the normalized peak area of CO stripping (defined as the ratio to the maximum COstrip peak area) across the wide range of VHold, PdC60 exhibited delayed CO poisoning, with negligible CO stripping peaks until −0.6 V. In contrast, profound CO poisoning occurred at much less cathodic potentials for PdC and pristine PdNPs (Fig. 4c). This further confirms the alleviated CO poisoning on Pd catalyst induced by abundant Pd/C60 interactions. Suppressed CO poisoning on PdC60 was similarly observed under alkaline conditions (1 M KOH), as evidenced by the pronounced CO poisoning occurring at more cathodic VHold on PdC60 compared to PdC and PdNPs (Supplementary Fig. 27).

To gain mechanistic insights into surface CO adsorption and poisoning under electrocatalytic conditions, in situ ATR-SEIRAS measurements were conducted in a three-electrode H-cell setup. In general, *CO adsorbs on Pd predominantly at bridge sites \((\nu \left({{\rm{C}}}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\right) \sim 1850{{\rm{c}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}^{-1})\), atop sites (\(\nu \left({{\rm{C}}}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{{{\rm{A}}}}\right) \sim 2100{{\rm{c}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}^{-1}\)), and hollow sites (\(\nu \left({{\rm{C}}}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{{{\rm{H}}}}\right) \sim 1800{{\rm{c}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}^{-1}\))48,79,80,81. As shown in Fig. 4d, e, all three CO adsorption peaks emerge on PdC60 at more negative potentials compared to PdC. Consistent with the CO stripping results in Fig. 4c, this further confirms that CO poisoning is significantly alleviated on the PdC60 surface under identical catalytic conditions. This phenomenon is more evident when we plotted the normalized *CO peak area (defined as the ratio to the maximum *CO peak area) on the function of cathodic potential for both Pd catalysts. As shown in Fig. 4f, PdC exhibits a much earlier onset for CO poisoning at only −0.1 V, while obvious CO poisoning on PdC60 is not observed until a strongly reducing potential of −0.6 V. Additionally, compared with PdC, PdC60 exhibits a distinct blue-shift in vibrational frequencies of COB and COA (Supplementary Fig. 28), indicating a weakened *CO binding strength82,83. Overall, the collected information underscores the largely alleviated CO poisoning after the introduction of Pd/C60 interface, which in turn facilitates the robust formate production across extended potential window.

Notably, we observed a rapid shift from COH to COB on both PdC60 and PdC at the cathodic potentials of approximately −0.7 V and −0.4 V, respectively, accompanied by a surge in peak area and the emergence of a minor COA peak (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 29). Such a sudden change in *CO configuration likely reflects structural transformations of the adsorption substrate29,81. Given the potential dependence of *CO adsorption spectra, we infer that the observed behavior of peak transition is possibly associated with the Pd-H phase transition. This hypothesis motivates a deeper investigation into the interplay between CO poisoning and Pd-H phase transition during the potential-driven evolutions of Pd-catalyzed CO2R, which is elaborated in the following section.

Origin of the potential-driven phase/performance evolutions in Pd-catalyzed CO2R

To elucidate the interplay between CO poisoning and phase transition, we plotted Pd-Pd distance (estimated from in situ PXRD) together with CO poisoning-related data (estimated from both CO stripping CVs and in situ ATR-SEIRAS) as the function of applied cathodic potential (Fig. 5a, b). Notably, these results exhibit a strong correlation: both the Pd-H phase transition and the onset of CO poisoning occur within a similar potential range (~ −0.6 V for PdC60 and ~ −0.3 V for PdC), suggesting a close relationship between the two phenomena. Importantly, owing to the postponed Pd-H phase transition and alleviated CO poisoning on PdC60, a significantly broader potential window is accessible for us to investigate the critical potential-driven processes.

Potential-dependent Pd-Pd distance and CO poisoning (from both CVs and in situ ATR-SEIRAS) on a PdC60 and b PdC. c In situ ATR-SEIRAS of PdC60 during potentiostatic CO2R electrolysis at −1.1 V. d In situ ATR-SEIRAS of PdC60 during CO stripping CVs after electrolysis at −1.1 V. α and β represent CO stripping peaks on α-PdH and β-PdH, respectively. The reactions were conducted in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 and at 25 °C. e Illustration of the proposed potential-driven evolution process in Pd-catalyzed CO2R. Gray: Pd; Red: H; COH (blue): hollow site *CO adsorption on α-PdH; COB (red): bridge site *CO adsorption on β-PdH. Typical solution resistance for 0.1 M KHCO3 was measured to be 11.9 Ω ± 1.5 Ω. 100% iR compensation was applied for all cathodic potentials. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

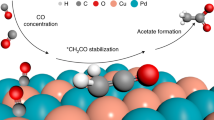

To gain deeper insights into the underlying mechanism, we monitored the real-time adsorption behavior of *CO species using in situ ATR-SEIRAS during the CO2R deactivation. As shown in Fig. 5c, during the rapid deactivation stage (around the 50th second, likely associated with the Pd-H phase transition), the adsorbed *CO species switch from COH to COB, accompanied by an abrupt intensity increase. This observation suggests that the Pd-H phase transition triggers a change in *CO adsorption configuration, which in turn aggravates CO poisoning. Complementarily, the in situ ATR-SEIRAS signals recorded during CO stripping provide further evidence corroborating this interplay (Fig. 5d). First, during the *CO desorption from β-PdH (indicated by the rise of CO stripping peak on β-PdH, ~0.8 V), the COB peak gradually diminishes, suggesting that COB is the primary surface *CO adsorption mode on β-PdH. Second, during the transition between *CO desorption on β-PdH and α-PdH (the potential region between two CO stripping peaks), a pronounced wavenumber shift of *CO species from COB to COH is accompanied by a significant decrease in peak intensity and the appearance of a minor COA peak. These changes indicate that the Pd-H phase transition alters the *CO adsorption configuration. Specifically, the increased hydrogen content in the Pd lattice weakens *CO binding strength, which facilitates the formation of CO but ultimately leads to severe catalyst deactivation during CO2R6.

Taken together, the interplay between Pd-H phase transition and CO poisoning can be summarized as follows: (1) increasing the cathodic potential promotes both by facilitating lattice H intercalation and CO formation. (2) During the Pd-H phase transition, the *CO adsorption mode shifts from COH to COB, along with exacerbated surface CO coverage and poisoning, resulting in CO2R deactivation. Based on these insights, we illustrate the detailed potential-driven phase/performance evolutions in Pd-catalyzed CO2R (Fig. 5e): Region Ⅰ: under mild cathodic potential, α-PdH forms rapidly, favoring the formate pathway while suppressing CO formation, achieving selective and active CO2-to-formate conversion; Region Ⅱ: upon Pd-H phase transition, β-PdH forms and facilitates CO formation, leading to severe CO poisoning and Pd deactivation; Region Ⅲ: although a partial recovery in current density is observed upon further cathodic polarization, the CO2R selectivity shifts away from formate to CO.

Computational exploration of the enhanced CO2R to formate on PdC60

The mechanistic insights into the Pd/C60 interfacial effects on the CO2R activity were further investigated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations and microkinetic analysis conducted using a catalyst model featuring Pd nanocrystallites (1.4 nm in size) supported on (011) surface of crystalline C60 (Fig. 6a). These Pd nanocrystallites exhibit a face-centered cubic crystal lattice, akin to the Pd clusters/particles observed in TEM images (Fig. 1a–d). Previous studies have shown that such nanocrystallites reliably represent the properties of experimentally prepared nanoclusters84,85. The first step in identifying a reliable model for Pd clusters on C60 for the reaction analysis involved screening thousands of tentative structures using a Modified Embedded-Atom Method (MEAM) interatomic potential. The eight PdC60 configurations with the lowest energies obtained during this screening within the 1.7 σ range (where σ is the fitting quality) were further relaxed through electronic structure calculations using the Vienna Ab-Initio Simulation Package (VASP). The same most stable interface structure identified based on the DFT and MEAMs energy values was used in further simulations of catalytic properties. Increasing the range from 1.7 σ to 2 σ will double the number of computationally expensive DFT calculations, but increase the confidence level only from 90% to 95%. (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 30 and Supplementary Note 3)86. Similar approach was employed in our previous studies of PtC60 catalysts for alkaline HER24. As shown in Fig. 6b, Bader analysis reveals that the electronic interactions between the Pd metal and C60 support lead to the transfer of 2.4 electrons from the Pd particle to the C60 plane, resulting in +0.14 average charge on the Pd atoms and the charge below −0.1 a.u. on C atoms at the PdC60 interface (Supplementary Note 3). Such charge transfer aligns well with the above experimental characterizations (Fig. 1e–h). Additionally, Pd clusters exhibit stronger interactions with C60 support compared to graphene (details in Ref. 87) manifested by the difference in the respective binding energies per Pd atom (−1.05 eV vs. −0.43 eV) and the number of transferred electrons (2.4 vs. 0.7).

a The calculated model of PdC60 catalyst with C atoms in the surface and subsurface fullerene molecules displayed in black and gray, respectively. Pd atoms on the edge are displayed in dark green, and Pd atoms on terraces in light green. b Electronic density difference due to the interactions between Pd and C60 displayed as an integrated 1D profile and as an isosurface plotted at 0.02 e Å−3, where the red regions indicate an excess of electrons, and the blue regions denote a deficit of electrons. The phase diagram for c PdC60, d PdC, and e unsupported PdNPs showcasing the stability of the various phases at different chemical potentials of surface H. f The reaction energy profile of the desired reaction pathway for CO2R to formate on α- and β-hydride phase of PdC60. The reaction energy profile of the desired reaction pathway for g CO2R to formate and h CO2R to CO on α-hydride phases of PdC60, PdC, and pristine PdNPs calculated at U = 0 V vs RHE and pH = 6.8. The rate-determining steps are labeled in each plot, with the values indicated in the respective colors for the different systems. i LSV of PdC60, PdC, and pristine PdNPs calculated from the microkinetic model for formate production. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Under cathodic potentials, Pd transforms into α- or β-phase of PdH whereby H-atoms cover the NP surface or diffuse into the Pd lattice (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32)16. When PdC60 is transformed into the α-PdH structure, the average Bader charge on surface Pd atoms changes to +0.18 a.u., altering the electronic structure and the reactivity of the catalyst. As shown in Fig. 6c–e, the transition from α-PdH to β-PdH in PdC60 occurs at a significantly more cathodic potential (~ −0.6 V) compared to PdC and pristine PdNPs (~ −0.4 V), as detailed in Supplementary Notes 3 and 5. This shift confirms that C60 substrate likely stabilizes the catalytically favorable α-PdH phase, thereby postponing the undesired transition to β-PdH.

To underscore the importance of the α-PdH stabilization in enabling energy-efficient CO2-to-formate, we further compared the reaction energetics on α-PdH and β-PdH using PdC60 as a model system (Fig. 6f). The calculated reaction energy profiles reveal that the α-PdH phase stabilizes the *OCOH intermediate, with an energy barrier that is 0.27 eV lower than that on β-PdH. Consistent trends were observed for PdC and pristine PdNPs references (Supplementary Fig. 33). These differences indicate more favorable reaction energy profiles of CO2R on the α-PdH phase for formate production. Therefore, in combination with the potential-dependent phase transition discussed in Fig. 6c–e, PdC60 maintains a consistently lower energy barrier across a wider potential range (0 to −0.6 V), attributed to the stabilized α-PdH phase under cathodic potentials. In contrast, PdC and PdNPs undergo a sharp increase in reaction barriers upon the onset of β-PdH formation (beyond approximately −0.4 V). These results suggest that the postponed α-to-β hydride transition on PdC60 preserves the favorable α-PdH structure over a broader potential window, thereby ensuring higher activity and selectivity for CO2-to-formate conversion.

Further insights into the catalytic selectivity were gained by comparing the reaction energy profiles on the α-PdH phase across different catalysts. As shown in Fig. 6g, α-PdH phase of PdC60 exhibits a lower energy barrier (0.51 eV) for CO2-to-formate compared to those of PdC and PdNPs (0.55 eV), indicating improved intrinsic activity of PdC60 for formate production compared to other Pd catalysts. Moreover, the competing CO2-to-CO pathway is suppressed on α-PdH phase of PdC60, as evidenced by the higher energy barrier for CO formation (1.57 eV), relative to PdC (1.40 eV) and PdNPs (1.29 eV) (Fig. 6h). In addition, the undesired HER is also less favorable on PdC60, with a higher energy barrier compared to the other two catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 34). Similar differences were also observed on the β-PdH phases of the considered catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 35). These results confirm that introducing C60 substrate not only facilitates CO2-to-formate conversion but also inhibits undesired side reactions. Meanwhile, the solvation effects were considered via the implicit solvation model, using the VASPSOL module (Supplementary Fig. 36)88,89. The close agreement between the results calculated with and without the consideration of solvation effects validates the internal consistency of the computational protocol and its reliability for obtaining the discussed mechanistic insights.

Building on the above reaction energy profiles, we further evaluated the activity enhancement of PdC60 using a recently developed microkinetic model for CO2-to-formate on Pd (111) surface, utilizing the adjusted activation energies obtained from the literature (Supplementary Tables 13−15)69,90,91,92. This microkinetic model incorporates three competing pathways: the desired CO2-to-formate conversion and two side reactions, CO2-to-CO and HER. As a result of the distinct energy barriers discussed above, PdC60 exhibits approximately 10 times higher jFormate at −0.6 V compared to PdC and pristine PdNPs, as shown in Fig. 6i. The substantial enhancement underscores the critical role of Pd/C60 interactions in stabilizing α-PdH and promoting the selectivity towards formate.

In addition to the stabilized α-PdH and favorable reaction energetics, CO poisoning is significantly mitigated on PdC60, contributing to the enhanced CO2-to-formate activity. Specifically, CO binds the Pd sites in 3 distinct geometries: atop, bridge, and hollow sites, as previously described48,79,80,81. In line with the experiment, the PdC60 composite binds CO molecules by 0.19 and 0.45 eV weaker than PdC and PdNPs (Supplementary Fig. 37a) in the α-hydride phase, mitigating the surface CO poisoning under catalytic conditions. Moreover, the vibrational frequencies of CO at different sites on PdC60 with varying levels of H saturation are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 37b. The wavelengths of the vibrational normal modes corroborate the results presented in the experimental counterpart (Fig. 4d, e).

Overall, our model attributes the enhanced activity and selectivity of PdC60 for CO2-to-formate conversion to combined synergistic effects induced by nanoparticle-support interactions, including stabilization of more selective α-PdH phase, optimized intermediate adsorption, and effective suppression of CO poisoning. These structural and electronic modifications collectively benefit energy-efficient and highly selective formate production on PdC60.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate energy-efficient CO2-to-formate reaction on Pd-based catalyst through the rational engineering of a palladium/fullerene (Pd/C60) interface. The interfacial charge transfer effectively stabilizes Pdδ+ species, which suppresses potential-driven deactivation and enables both enhanced intrinsic activity and a broadened operational potential window for selective formate production. Specifically, practically relevant current density (i.e., 250 mA cm−2 over 4 cm2) was achieved at the small cell voltage of 1.71 V with full-cell EE up to 72%, indicating its promise for future applications. Moreover, benefiting from the extended potential window due to postponed Pd-H phase transition and alleviated CO poisoning on PdC60, we are able to shed light on the origin of the potential-driven phase/performance interplay for Pd-based catalyst during CO2R. Our collective evidence reveals that increasing cathodic potential aggravates both Pd-H phase transition and CO poisoning, where the former further exacerbates the latter and thereby compromises formate production. These findings provide critical mechanistic insights into the deactivation pathways of Pd-catalyzed CO2R and demonstrate an effective strategy to mitigate this deactivation, enabling energy-efficient CO2-to-formate conversion.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Sodium tetrachloropalladate (II) (Na2PdCl4, 98%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 99%), ethylene glycol (OHCH2CH2OH, 99%), nickel (II) diperchlorate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 99%), iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 98%), urea (CO(NH2)2, 98%), ammonium fluoride (NH4F, 98%) and Nafion™ 117 containing solution (~5% in a mixture of lower aliphatic alcohols and water) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Potassium hydroxide (KOH, 99.99%) and potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, 99.99%) were purchased from Macklin. Buckminsterfullerene (C60, 99%) powder was purchased from TanFeng. Int. Ketjen black and carbon paper with microporous layer (YLS30T) were purchased from Suzhou Sinero Technology Co., Ltd. All chemicals were used as received. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ.cm, Millipore) was used throughout the experiments.

Material characterizations

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) were taken by a JEOL JEM-2010F TEM. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted on Kratos Axis UltraDLD (Mono Al Kα, hν = 1486.71 eV). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8-Advance diffractometer, operating at 40 kV and 30 mA, with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was performed using ThermoFisher CCAPG200 DUO. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was performed at SPring-8 under transmission mode, and the data were processed by Athena. In situ powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were collected with a 9 kW Rigaku SmartLab machine equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). In situ ATR-SEIRAS was measured by Shimadzu IR Tracer-100 FTIR Spectrophotometer.

Catalysts synthesis

Synthesis of PdC60 catalyst

The C60 bulk crystal was first prepared based on the liquid-liquid interface-precipitation method. Typically, 20 mg C60 powder was dissolved in 2 mL toluene and ultrasonicated for 30 min. Next, 2 mL of ethanol was added slowly to the mixed solution to form the liquid-liquid interface, and then the solution was transferred to a refrigerator and kept at 5 °C for 24 h. Then, the sample was collected by centrifuge and dried at 80 °C overnight. Next, the PdC60 was prepared via a facile solution-phase method. 8 mg of C60 bulk crystal was added into 5 mL of ethanol and ultrasonicated for 30 min to get a brown suspension, which was mixed with 24 mL ethylene glycol. Subsequently, 23.6 mg Na2PdCl4 (0.08 mmol, dissolved in 400 μL ethylene glycol) was added into C60 suspension under vigorous stirring. Then, NaBH4 solution (304 mg, 8 mmol in 20 mL water) was pumped into the solution at a rate of 1 mL min−1 under the control of a peristaltic pump in ice bath and stirred for 8 h. The obtained powder samples were rinsed by ethanol 3 times, then collected by centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 4 min and dried at 80 °C overnight.

Synthesis of PdC, PdCNT, and pristine PdNPs catalysts

8 mg of ketjen black was added into 5 mL ethanol and ultrasonicated for 30 min to get a black suspension, which was mixed with 24 mL ethylene glycol. Subsequently, 23.6 mg Na2PdCl4 (0.08 mmol, dissolved in 400 μL ethylene glycol) was added into the ketjen black suspension under vigorous stirring. Then, NaBH4 solution (304 mg, 8 mmol in 20 mL water) was pumped into the solution at a rate of 1 mL min−1 under the control of a peristaltic pump in ice bath and stirred for 8 h. The obtained powder samples were rinsed by ethanol 3 times, then collected by centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 4 min and dried at 80 °C overnight. For PdCNT, the Ketjen black was replaced by carbon nanotubes, and for pristine PdNPs no substrate was added.

Synthesis of PdC60 with modified interface

The synthesis for PdC60−1 and PdC60-2 followed the general synthetic procedure for PdC60, with modifications to accelerate the Pd precipitation. For PdC60-1, a concentrated NaBH4 solution (304 mg, 8 mmol in 2 mL water) was introduced into the Na2PdCl4 solution at a rate of 1 mL min−1. For PdC60-2, the synthesis was conducted at room temperature (25 °C) instead of an ice bath. PdC60-3 was prepared by physically mixing pristine PdNPs with C60 at a mass ratio of 1:1.

Synthesis of NiFe-LDH

The nickel-iron layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanosheet arrays in situ growing on nickel foam were synthesized through a facile one-pot solvothermal method. Typically, 0.2 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.3 mmol Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 15 mmol urea and 8 mmol NH4F were dissolved in 50 mL water and stirred to form a clear solution. Nickel foam (4 × 2 cm) was carefully cleaned with 3 M HCl solution in an ultrasound bath for 30 min to remove the surface NiO layer, and then water and EtOH were used for 30 min to ensure the surface of Ni foam was cleaned. Both the Ni foam and the solution were transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. The pretreated Ni foam was vertically immersed in the solution. The in situ growth was carried out in an oven for 6 h at 120 °C. Subsequently, the obtained NiFe-LDH was rinsed with water and EtOH and dried at 80 °C overnight.

Electrochemical measurements

Bio-Logic VMP3 multichannel potentiostat was used for controlling electrochemical measurements. Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference electrode. It was calibrated using a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) in H2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte (pH = 0), with Pt wire and graphite rod as working electrode and counter electrode, respectively. The solution resistance (Rs) in both H-cell and flow cell was evaluated using potentiostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (PEIS) with a frequency scan range from 1 MHz to 10 Hz. The resulting data was analyzed by EC-Lab software. All the recorded potentials were converted to RHE scale with 100% iR compensation based on:

The gas products were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC, Shimadzu 2014). Liquid products were analyzed by 1H NMR spectrum (Bruker, 400 MHz). Faradaic efficiency (FE) for each product was calculated based on:

where n is the electron transfer number of a specific product, F is the Faraday constant (96485 C mol−1), I is the total current, and t is reaction time.

Different electrolytes were employed in this study. For the H-cell test, 0.1 M KHCO3 and 1 M KHCO3 were used. For the flow-cell test, 1 M KHCO3 and 1 M KOH were used. For the MEA test, 1 M KOH was used. Fresh electrolytes were prepared and stored in a sealed polypropylene bottle for same-day use in experiments, by dissolving the appropriate amounts of KHCO3 and KOH in 1 L of ultrapure water. The pH of the solutions was measured using a Mettler-Toledo S400 benchtop pH meter, with the pH values of 0.1 M KHCO3 (CO2 saturated), 1 M KHCO3 (CO2 saturated), and 1 M KOH being 6.80 ± 0.05, 8.36 ± 0.04, and 14.05 ± 0.02, respectively.

CO2R measurements in H-cell

1 mg samples (PdC60, PdC, PdCNT or pristine PdNPs) were dispersed in the mixed solution containing 300 μL water, 200 μL ethanol, and 4 μL 5 wt% Nafion. The ink was sonicated for 30 min and drop casted on carbon paper (1 × 1.5 cm, Fuel Cell Gas Diffusion Layer YLS30T) to reach the loading of 1 mg cm−2. The reaction was conducted in H-cell with a catalyst area of 1 cm2. The prepared carbon paper was used as the working electrode, while Ag/AgCl electrode and Pt foil were used as the reference electrode and counter electrode, respectively. Anion exchange membrane (Selemion AMN/N type 1, AGG Inc.) was applied to separate two compartments. CO2 reduction was conducted under ambient pressure and at room temperature (25 °C). During CO2 reduction, CO2 was purged continuously at a rate of 20 sccm (controlled by mass flow controller) to saturate the catholyte and anolyte (0.1 M KHCO3 for both). During the stability assessment, concentrated electrolyte (1 M KHCO3) was applied for both cathode and anode.

CO2R measurements in flow cell

1 mg samples (PdC60 or PdC) were dispersed in the mixed solution containing 200 μL of ethanol and 4 μL of 5 wt% Nafion. The ink was sonicated for 30 min and drop casted on carbon paper (1.2 × 1.2 cm, Fuel Cell Gas Diffusion Layer YLS30T) to reach the loading of 1 mg cm−2. The reaction was conducted in a flow cell designed by our team with a catalyst area of 1 cm2. The prepared carbon paper was used as the working electrode, while Ag/AgCl electrode and Pt foil were used as the reference electrode and counter electrode, respectively. Anion exchange membrane (Selemion AMN/N type 1, AGG Inc.) was applied to separate two compartments. Bio-Logic VMP3 multichannel potentiostat was used for controlling electrochemical measurements. CO2 reduction was conducted under ambient pressure and at room temperature (25 °C). During CO2 reduction, CO2 was flowed continuously through the gas chamber at a rate of 20 sccm (controlled by mass flow controller). The catholyte (1 M KHCO3 or 1 M KOH) and anolyte (1 M KHCO3 or 1 M KOH) flowed at a rate of 10 mL min−1 under the control of a peristaltic pump. Cathode energy efficiency (CEE) was calculated based on:

where \(E_{Formate}\) is −0.02 V vs. RHE for CO2R to formate93.

CO2R measurements in membrane electrode assembly (MEA) reactor

4 mg PdC60 sample was dispersed in the mixed solution containing 800 μL of ethanol and 16 μL of 5 wt% Nafion. The ink was sonicated for 30 min and drop casted on carbon paper (2 × 2 cm, Fuel Cell Gas Diffusion Layer YLS30T) to reach the loading of 1 mg cm−2. The measurements were performed using a commercial MEA electrolyzer (Suzhou Sinero Technology CO., LTD, 2 × 2 cm reaction area). The prepared carbon paper and NiFe layered double hydroxide (NiFe-LDH) was used as the working electrode and counter electrode, respectively. Sustainion Alkaline Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) X37-50 grade T (3 × 3 cm, thickness 50 μm) was applied to separate two compartments. Bio-Logic VMP3 multichannel potentiostat was used for controlling electrochemical measurements. CO2 reduction was conducted under ambient pressure. During CO2 reduction, humified CO2 was flowed continuously through the cathode side at a rate of 20 sccm (controlled by mass flow controller). A 1 M KOH solution, heated to 60 °C, was continuously flowed as the anolyte at 2 mL min−1 using a peristaltic pump. The anolyte was not circulated to prevent formate accumulation and potential anodic oxidation. The produced formate was collected from both the cathode and anode compartments and quantified by 1H NMR. On the cathode side, formate was carried by water vapor in the humidified CO2 stream and collected by purging the outlet gas through 5 mL of ultrapure water, which was subsequently analyzed by 1H NMR. The majority of the produced formate diffuses through the anion exchange membrane and was quantified directly from the anolyte using 1H NMR.

Full-cell energy efficiency (EE) was calculated based on:

where \(E_{Formate}\) is −0.02 V vs. RHE for CO2R to formate at pH = 14.

Water splitting test in membrane electrode assembly (MEA) reactor

For water splitting performance tests, Pt/C and NiFe-LDH serve as cathode and anode, respectively. A 1 M KOH solution, heated to 60 °C, was continuously flowed as the anolyte at 2 mL min−1 using a peristaltic pump. LSV polarization curves were recorded over a potential range of 0.5–2 V (vs. counter electrode) at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1.

Electrochemical surface area measurement

The ECSA test was performed in a standard three-electrode H-cell system with catalyst-loaded carbon paper as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, and platinum foil as the counter electrode. CV tests at different scan rates (20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160 mV s−1) were carried in Ar-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3.

In situ XAFS

In situ XAFS was performed at BL01B1 beamline of Super Photon Ring-8 GeV (Spring-8) in the fluorescence mode. A customized flow cell with alkaline (1 M KOH) electrolyte for CO2R was used. A Kapton tape was used to seal the gas chamber at the cathode side to allow the penetration of X-ray and fluorescence signals. Pd K-edge XAFS spectra were measured with electron energy of 2.4 GeV. XANES and EXAFS spectra were analyzed by using Athena and Artemis, included in the Demeter package. The standard reference material of Pd foil was measured in parallel. The energy was calibrated with Pd foil for Pd K-edge. Electrochemical tests were conducted with a Bio-Logic SP-300 potentiostat. Pd K-edge XANES and EXAFS spectra were collected. All characterizations were conducted at room temperature (25 °C) and ambient pressure.

In situ PXRD

In situ PXRD patterns were collected with a 9 kW Rigaku SmartLab machine equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The scanning speed and step size were set to be 10° min−1 and 0.02° per step, respectively. In situ experiment was carried in a homemade cell with a three-electrode system composed of the catalyst-loaded working electrode, a platinum wire as the counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode. CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 was used as the electrolyte. During the experiment, each cathodic potential was maintained for 10 min, with the collecting of PXRD patterns started at 5 min. All characterizations were conducted at room temperature (25 °C) and ambient pressure.

In situ ATR-SEIRAS

The working electrode was prepared on Au film that was pre-deposited onto a silicon ATR crystal via chemical deposition. 5 mg catalyst (PdC60 or PdC) was dispersed in 500 μL ethanol and 20 μL 5 wt% Nafion solution to form a homogeneous ink by sonicating. Then, the ink was dropped onto the Au film. The prepared working electrode was assembled into an H-cell. Ag/AgCl electrode and graphite rod served as reference and counter electrodes, respectively. Anion exchange membrane (Selemion AMN/N type 1, AGG Inc.) was applied to separate two compartments. 0.1 M KHCO3 was used as both catholyte and anolyte with continuous CO2 purging. The data was collected by Shimadzu IR Tracer-100 FTIR Spectrophotometer. Before data collection, the background was recorded at open-circuit potential. During the experiment, the cathodic potential changed from 0 V vs. RHE to −1.4 V vs. RHE and was maintained for 15 min at each cathodic potential. All data were presented in absorbance units. All characterizations were conducted at room temperature (25 °C) and ambient pressure.

Computational methods

The initial geometries of PdC60 models were relaxed using the Modified Embedded-Atom Method (MEAM) potential developed by Byeong-Joo Lee et al.94, which is implemented in the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) package95. The calculations were performed keeping the C60 fixed to maintain the lattice parameters and avoid distortion of the slab. The threshold parameters for geometry optimization in the LAMMPs calculation were \(1\times {10}^{-8}{{\rm{eV}}}\) for the energy and \(1\times {10}^{-8}{{\rm{eV}}}/{{\mathring{{\rm{A}}}}}\) for the forces. In turn, the most energetically stable structure of Pd NPs on graphene was obtained in the previous studies96. The VASP calculations, using PBE exchange-correlation functional, utilized solely the gamma point in the reciprocal space. Core and valence electron interactions were described using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method with a plane-wave basis set and a cut-off energy of 400 eV. Dispersion interactions were included using Grimme’s D3 method. The Methfessel-Paxton smearing approach with a smearing width of 0.1 eV was employed to set partial occupancies for each orbital. The convergence threshold for the SCF calculation is \(1\times {10}^{-5}{{\rm{eV}}}\) for the changes in the energy, while the geometric relaxations of all the atoms were terminated once the forces on all atoms were below \(2\times {10}^{-2}{{\rm{eV}}}/\mathring{\rm A}\). More information about the theoretical methods is available in Supplementary Notes 3 and 5.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jouny, M., Luc, W. & Jiao, F. General techno-economic analysis of CO2 electrolysis systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 2165–2177 (2018).

De Luna, P. et al. What would it take for renewably powered electrosynthesis to displace petrochemical processes?. Science 364, eaav3506 (2019).

Fan, L., Xia, C., Zhu, P., Lu, Y. & Wang, H. Electrochemical CO2 reduction to high-concentration pure formic acid solutions in an all-solid-state reactor. Nat. Commun. 11, 3633 (2020).

Lin, R. et al. PdAg bimetallic electrocatalyst for highly selective reduction of CO2 with low COOH* formation energy and facile CO desorption. Nano Res. 12, 2866–2871 (2019).

Jiang, B., Zhang, X. G., Jiang, K., Wu, D. Y. & Cai, W. B. Boosting formate production in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction over wide potential window on Pd surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2880–2889 (2018).

Gao, D. et al. Switchable CO2 electroreduction via engineering active phases of Pd nanoparticles. Nano Res. 10, 2181–2191 (2017).

Zhang, S., Kang, P. & Meyer, T. J. Nanostructured tin catalysts for selective electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1734–1737 (2014).

Han, N., Ding, P., He, L., Li, Y. & Li, Y. Promises of main group metal–based nanostructured materials for electrochemical CO2 reduction to formate. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1902338 (2019).

Kuang, Y. et al. High-concentration electrosynthesis of formic acid/formate from CO2: reactor and electrode design strategies. Energy Environ. Mater. 6, e12596 (2023).

Sheng, W. et al. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 to synthesis gas with controlled CO/H2ratios. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1180–1185 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Enhancing activity and reducing cost for electrochemical reduction of CO2 by supporting palladium on metal carbides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6271–6275 (2019).

He, Q. et al. Accelerating CO2 electroreduction to CO over Pd single-atom catalyst. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000407 (2020).

Min, X. & Kanan, M. W. Pd-catalyzed electrohydrogenation of carbon dioxide to formate: high mass activity at low overpotential and identification of the deactivation pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4701–4708 (2015).

Lee, C. W., Cho, N. H., Nam, K. T., Hwang, Y. J. & Min, B. K. Cyclic two-step electrolysis for stable electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to formate. Nat. Commun. 10, 3919 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Mesoporous PdAg nanospheres for stable electrochemical CO2 reduction to formate. Adv. Mater. 32, e2000992 (2020).

Blom, M. J. W., van Swaaij, W. P. M., Mul, G. & Kersten, S. R. A. Mechanism and micro kinetic model for electroreduction of CO2 on Pd/C: the role of different palladium hydride phases. ACS Catal. 11, 6883–6891 (2021).

Gao, D. et al. Pd-containing nanostructures for electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 8, 1510–1519 (2018).

Ye, C., Dattila, F., Chen, X., Lopez, N. & Koper, M. T. M. Influence of cations on HCOOH and CO formation during CO2 reduction on a Pd(ML)Pt(111) electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19601–19610 (2023).

Zhou, R. et al. Two-dimensional palladium-copper alloy nanodendrites for highly stable and selective electrochemical formate production. Nano Lett. 21, 4092–4098 (2021).

Song, I. et al. Ultrasmall Pd clusters in FER zeolite alleviate CO poisoning for effective low-temperature carbon monoxide oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27493–27499 (2023).

Tackett, B. M., Lee, J. H. & Chen, J. G. Electrochemical conversion of CO2 to syngas with palladium-based electrocatalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1535–1544 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Promote electroreduction of CO2 via catalyst valence state manipulation by surface-capping ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218040120 (2023).

Hou, L. et al. Synthesis of a monolayer fullerene network. Nature 606, 507–510 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Modulating the binding strength of multiple intermediates by few-layer fullerene network electron buffer for alkaline hydrogen evolution. Small 21, e2506131 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Diversity of platinum-sites at platinum/fullerene interface accelerates alkaline hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 1711 (2023).

Shrestha, R. G., Shrestha, L. K., Abe, M. & Ariga, K. Production of self-assembled fullerene (C60) nanocrystals at liquid-liquid interface. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 15, 2394–2399 (2015).

Zhou, F., Li, H., Fournier, M. & MacFarlane, D. R. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to formate at low overpotentials on electrodeposited Pd films: stabilized performance by suppression of CO formation. ChemSusChem 10, 1509–1516 (2017).

Rahaman, M., Dutta, A. & Broekmann, P. Size-dependent activity of palladium nanoparticles: efficient conversion of CO2 into formate at low overpotentials. ChemSusChem 10, 1733–1741 (2017).

Zhu, S. et al. Tuning structural and compositional effects in Pd–Au nanowires for highly selective and active CO2 electrochemical reduction reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802238 (2018).

Sathish, M. & Miyazawa, K. I. Selective precipitation of tubular-like short fullerene (C 60) whiskers at liquid–liquid interface. CrystEngComm 12, 4146–4151 (2010).

Miyazawa, K. et al. Structural characterization of C60 nanowhiskers formed by the liquid/liquid interfacial precipitation method. Surf. Interface Anal. 35, 117–120 (2003).

Shulga, Y., Lobach, A., Ivleva, I. N., Spektor, V. N. & Ovchinnikov, A. A. X-ray photoelectron spectra and magnetic susceptibility of palladium fulleride C60Pdn(n = 1-4.9). Dokl. Chem. 348, 162–164 (1996).

Xing, X.-L. et al. High performance Ag rich Pd-Ag bimetallic electrocatalyst for ethylene glycol oxidation in alkaline media. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, J3259–J3265 (2018).

Ganji, N., Karimi, B., Najafvand-Derikvandi, S. & Vali, H. Palladium supported on a novel ordered mesoporous polypyrrole/carbon nanocomposite as a powerful heterogeneous catalyst for the aerobic oxidation of alcohols to carboxylic acids and ketones on water. RSC Adv. 10, 13616–13631 (2020).

Kortlever, R., Peters, I., Koper, S. & Koper, M. T. M. Electrochemical CO2 reduction to formic acid at low overpotential and with high faradaic efficiency on carbon-supported bimetallic Pd–Pt nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 5, 3916–3923 (2015).

Klinkova, A. et al. Rational design of efficient palladium catalysts for electroreduction of carbon dioxide to formate. ACS Catal. 6, 8115–8120 (2016).

Han, N. et al. Ultrathin bismuth nanosheets from in situ topotactic transformation for selective electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to formate. Nat. Commun. 9, 1320 (2018).

Sui, P. F. et al. Carbon dioxide valorization via formate electrosynthesis in a wide potential window. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203794 (2022).

Lin, D. & Lasia, A. Electrochemical impedance study of the kinetics of hydrogen evolution at a rough palladium electrode in acidic solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 785, 190–195 (2017).

Li, L. et al. Stable, active CO2 reduction to formate via redox-modulated stabilization of active sites. Nat. Commun. 12, 5223 (2021).

Chang, S., Xuan, Y., Duan, J. & Zhang, K. High-performance electroreduction CO2 to formate at Bi/Nafion interface. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 306, 121135 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Industrial-current-density CO2-to-formate conversion with low overpotentials enabled by disorder-engineered metal sites. Nano Res. 15, 6999–7007 (2022).

Zou, J., Lee, C.-Y. & Wallace, G. G. A non-noble metal catalyst-based electrolyzer for efficient CO2-to-formate conversion. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 16394–16402 (2021).

He, S. et al. The p-orbital delocalization of main-group metals to boost CO2 electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16114–16119 (2018).

Gong, Q. et al. Structural defects on converted bismuth oxide nanotubes enable highly active electrocatalysis of carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 10, 2807 (2019).

Zheng, X. et al. Sulfur-modulated tin sites enable highly selective electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formate. Joule 1, 794–805 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Surface-oxygen-rich Bi@C nanoparticles for high-efficiency electroreduction of CO2 to formate. Nano Lett. 22, 9107–9114 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Unraveling the interfacial effect of PdBi bimetallic catalysts on promoting CO2 electroreduction to formate. Nano Res. 16, 10822–10831 (2023).

Cao, C. et al. Metal–organic layers leading to atomically thin bismuthene for efficient carbon dioxide electroreduction to liquid fuel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15014–15020 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Bi-based metal-organic framework derived leafy bismuth nanosheets for carbon dioxide electroreduction. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001709 (2020).

Liang, C. et al. High efficiency electrochemical reduction of CO2 beyond the two-electron transfer pathway on grain boundary rich ultra-small SnO2 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 10313–10319 (2018).

Ren, B. et al. Nano-crumples induced Sn-Bi bimetallic interface pattern with moderate electron bank for highly efficient CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2486 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Pinpointing the axial ligand effect on platinum single-atom-catalyst towards efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 6875 (2022).

Koshikawa, H. et al. Single nanometer-sized NiFe-layered double hydroxides as anode catalyst in anion exchange membrane water electrolysis cell with energy conversion efficiency of 74.7% at 1.0 A cm–2. ACS Catal. 10, 1886–1893 (2020).

Jeon, S. S. et al. Design principles of NiFe-layered double hydroxide anode catalysts for anion exchange membrane water electrolyzers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 37179–37186 (2021).

Ha, J. S. et al. Solar-powered AEM electrolyzer via PGM-free (oxy) hydroxide anode with solar to hydrogen conversion efficiency of 12.44%. Adv. Sci. 11, 2401782 (2024).

Overa, S. et al. Enhancing acetate selectivity by coupling anodic oxidation to carbon monoxide electroreduction. Nat. Catal. 5, 738–745 (2022).

Xu, Q. et al. Electrolyte effects in membrane-electrode-assembly CO electrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202501505 (2025).

Xia, C. et al. Continuous production of pure liquid fuel solutions via electrocatalytic CO2 reduction using solid-electrolyte devices. Nat. Energy 4, 776–785 (2019).

Yang, H., Kaczur, J. J., Sajjad, S. D. & Masel, R. I. Performance and long-term stability of CO2 conversion to formic acid using a three-compartment electrolyzer design. J. CO2 Util. 42, 101349 (2020).

Yu, X. et al. Coverage enhancement accelerates acidic CO2 electrolysis at ampere-level current with high energy and carbon efficiencies. Nat. Commun. 15, 1711 (2024).

Zheng, T. et al. Copper-catalysed exclusive CO2 to pure formic acid conversion via single-atom alloying. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1386–1393 (2021).

Fang, W. et al. Durable CO2 conversion in the proton-exchange membrane system. Nature 626, 86–91 (2024).

Jewell, L. L. & Davis, B. H. Review of absorption and adsorption in the hydrogen–palladium system. Appl. Catal. A General 310, 1–15 (2006).

Millet, P. Thermodynamic paths in the two-phases domain of the PdH system and a method for kinetic analysis. Electrochem. Commun. 7, 40–44 (2005).

Viola, A., Maillard, F. & Tsirlina, G. Voltammetric quantification of H: Pd ratio complicated by α↔ β phase transition in PdHx: electrodes with low Pd loadings. Electrochim. Acta 485, 144085 (2024).

Yang, T.-H., Pyun, S.-I. & Yoon, Y.-G. Hydrogen transport through Pd electrode: current transient analysis. Electrochim. Acta 42, 1701–1708 (1997).

Guo, S. et al. Robust palladium hydride catalyst for electrocatalytic formate formation with high CO tolerance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 316, 121659 (2022).

Abdellah, A. M. et al. Impact of palladium/palladium hydride conversion on electrochemical CO2 reduction via in-situ transmission electron microscopy and diffraction. Nat. Commun. 15, 938 (2024).

Niu, Y. et al. Visualizing Formation of Intermetallic PdZn in a Palladium/Zinc Oxide Catalyst: Interfacial Fertilization by PdHx. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 4232–4237 (2019).

Benck, J. D., Jackson, A., Young, D., Rettenwander, D. & Chiang, Y.-M. Producing high concentrations of hydrogen in palladium via electrochemical insertion from aqueous and solid electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 31, 4234–4245 (2019).

Makmeesub, N. et al. Reversible hydrogenation–dehydrogenation of acetylpyridine-Pd-MIL-101(Cr) for chemical hydrogen storage. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 17671–17679 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Synthesis of bimetallic Pt-Pd core-shell nanocrystals and their high electrocatalytic activity modulated by Pd shell thickness. Nanoscale 4, 845–851 (2012).

Iqbal, M. et al. Tethering mesoporous Pd nanoparticles to reduced graphene oxide sheets forms highly efficient electrooxidation catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 21249–21256 (2017).

Al Abass, N. A., Denuault, G. & Pletcher, D. The unexpected activity of Pd nanoparticles prepared using a non-ionic surfactant template. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 4892–4899 (2014).

Guo, R.-H. & Hu, C.-C. The relationships among hydrogen adsorption, CO stripping, and selectivity of CO2 reduction on Pd nanoparticles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 054507 (2021).

Chen, X., Granda-Marulanda, L. P., McCrum, I. T. & Koper, M. T. M. How palladium inhibits CO poisoning during electrocatalytic formic acid oxidation and carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 13, 38 (2022).

Guo, R.-H., Liu, C.-F., Wei, T.-C. & Hu, C.-C. Electrochemical behavior of CO2 reduction on palladium nanoparticles: dependence of adsorbed CO on electrode potential. Electrochem. Commun. 80, 24–28 (2017).

Wang, H., Zhou, Y.-W. & Cai, W.-B. Recent applications of in situ ATR-IR spectroscopy in interfacial electrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 1, 73–79 (2017).

Pei, G. X. et al. Performance of Cu-alloyed Pd single-atom catalyst for semihydrogenation of acetylene under simulated front-end conditions. ACS Catal. 7, 1491–1500 (2017).

Ladas, S., Poppa, H. & Boudart, M. The adsorption and catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide on evaporated palladium particles. Surf. Sci. 102, 151–171 (1981).

Fu, W. et al. Preserving molecular tuning for enhanced electrocatalytic CO2-to-ethanol conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407992 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Cu/LaF3 interfaces boost electrocatalytic CO-to-acetate conversion. ACS Catal. 14, 8366–8375 (2024).

Suchorski, Y. et al. The role of metal/oxide interfaces for long-range metal particle activation during CO oxidation. Nat. Mater. 17, 519–522 (2018).

Lykhach, Y. et al. Counting electrons on supported nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 15, 284–288 (2016).

Shiekh, B. A. Hierarchy of commonly used DFT methods for predicting the thermochemistry of Rh-mediated chemical transformations. ACS Omega 4, 15435–15443 (2019).

Franz, D. et al. Hydrogen solubility and atomic structure of graphene supported Pd nanoclusters. ACS Nano 15, 15771–15780 (2021).

Mathew, K., Kolluru, V. S. C., Mula, S., Steinmann, S. N. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit self-consistent electrolyte model in plane-wave density-functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 234101 (2019).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Filot, I. A., Van Santen, R. A. & Hensen, E. J. The optimally performing Fischer–Tropsch catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 12746–12750 (2014).

Kowalec, I. Surfaces of Pd-Based Alloys as Catalysts for CO2 Activation and Hydrogenation to Methanol Cardiff University (2023).

Chen, J., Hu, L. & Tang, T. Ab initio microkinetic modelings of molecular reactions on Pd (100), Pd (110), and Pd (111) surfaces: a CO2/CO reduction case study. J. Phys. Chem. C 126, 7468–7481 (2022).

Kuhl, K. P., Cave, E. R., Abram, D. N. & Jaramillo, T. F. New insights into the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on metallic copper surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7050–7059 (2012).

Jeong, G.-U. & Lee, B.-J. Interatomic potentials for Pt-C and Pd-C systems and a study of structure-adsorption relationship in large Pt/graphene system. Comput. Mater. Sci. 185, 109946 (2020).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Lee, K. et al. Engineering nanoscale H supply chain to accelerate methanol synthesis on ZnZrOx. Nat. Commun. 14, 819 (2023).

Acknowledgements