Abstract

Autologous CAR-T therapies targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) have demonstrated therapeutic clinical responses. Here, we present the characterization and interim Phase I data for P-BCMA-ALLO1, a TSCM-predominant allogeneic CAR-T therapy targeting BCMA in heavily pretreated relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Preclinical analyses reveal a strong correlation between CD8+ TSCM phenotype and in vivo potency in mouse xenograft models. In early clinical data (NCT04960579), among the 11 of 33 evaluable patients who received enhanced lymphodepletion, 82% (9/11) responded, with 63.6% (7/11) achieving very good partial response (VGPR) or better. All patients started therapy a median of 1 day after enrollment, with every patient receiving P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion, and resulting in a 100% intent-to-treat (ITT) rate with no use of bridging therapy. CRS was reported in 21.2% (7/33) across all cohorts, all grade ≤2. The median time to peak CAR-T cell expansion (Tmax) was 10 days post-infusion. Consistent with preclinical findings, CAR-T cell expansion is accompanied by differentiation from a predominantly TSCM phenotype to a TEM/TEFF phenotype, with trafficking and persistence observed in bone marrow. These data suggest that a TSCM cellular phenotype may offer significant advantages in efficacy, safety, and cellular persistence in the context of allogeneic CAR-T therapy. Clinical trial: NCT04960579

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapies have revolutionized the treatment of lymphoid and plasma cell malignancies, achieving deep and durable responses in patients who have progressed after multiple prior-line therapies. Currently, all commercially available CAR-T therapies are autologous, produced from each patient’s own T cells. Autologous CAR-T therapies targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) have demonstrated remarkable clinical responses1,2,3,4. However, access to these treatments remains challenging due to several factors, including: the process of apheresis, the individualized nature of manufacturing, where patient-specific health and logistics factors contribute to inconsistencies, the need for bridging therapy (BT) that may result in adverse events, and ultimately, higher costs. Autologous therapies are also associated with high toxicity rates, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS)1,2,3. Moreover, patient-derived T cells are often more differentiated, exhausted, senescent or dysfunctional, and have likely been exposed to multiple mutagenic chemotherapy agents5,6. In contrast, the use of healthy donor (HD)-derived allogeneic CAR-T cells could address these limitations by increasing access through the generation of multiple doses per manufacturing run, enhancing safety by eliminating the need for BT, and producing CAR-T cells from less differentiated starting T cells. However, potential HLA mismatches between allogeneic CAR-T cells and patients necessitate gene editing to prevent alloreactive responses, including host-versus-graft (HVG) and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and to promote CAR-T persistence. The optimal potency, lymphodepletion (LD) regimens, and safety profiles of allogeneic CAR-T therapies remain to be fully defined.

We have developed an allogeneic anti-BCMA CAR-T cell therapy, P-BCMA-ALLO1, which is currently undergoing Phase I evaluation in heavily pretreated RRMM patients who have progressed following proteasome inhibitors (PI)s, immunomodulatory drugs (IMiD)s, and CD38 monoclonal antibodies (NCT04960579). P-BCMA-ALLO1 is constructed with an anti-BCMA variable heavy chain (VH) CAR, a CD3ζ intracellular domain, and a 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain, integrated into the genome using a non-viral, hyperactive super piggyBac (sPB) transposase system. To mitigate alloreactivity, a dual guide RNA (gRNA)-targeted nuclease, Cas-CLOVER (CC), is used to target genes relevant in a mismatched settings7. Specifically, TRBC1 and TRBC2 are targeted to inactivate the T-cell receptor (TCR)-αβ, and B2M encoding β2-microglobulin (β2M) is targeted to prevent the formation of the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I). Genetically modified cells are positively selected during manufacturing, yielding a virtually pure CAR+ and TCR- T-cell product. This approach aims to produce safe and effective CAR-T cells from HDs, overcoming the manufacturing challenges of autologous CAR-T cells and enabling “off-the-shelf” availability for rapid patient dosing.

In this report, we characterized P-BCMA-ALLO1 proteomically, transcriptionally, and functionally, finding that a high percentage of CD8+ stem cell memory (TSCM) cells and memory-related functionalities (proliferation, persistence, polyfunctionality) correlate with antitumor activity in mouse xenograft models. The correlation between memory phenotype and progenitor attributes with CAR-T efficacy aligns with previous findings, which demonstrate that the frequencies of CD8+ T cells and memory CD8+ T cells expressing CD27, CCR7, and CD62L correlate with both in vivo preclinical tumor control and clinical response8,9,10,11. The advantage of the memory phenotype is further validated by interim results from the ongoing Phase I dose-escalation study, where multiple cell doses and LD strategies are being tested. As of the data cut-off October 23, 2023, clinical responses were observed in study arms where patients received enhanced LD chemotherapy (LD; ≥500 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (Cy) + 30 mg/m2 fludarabine (Flu), each administered for three days). Importantly, all patients received P-BCMA-ALLO1 a median of 7 days after enrollment, resulting in a 100% intent-to-treat (ITT) rate with no use of BT. In these arms, CAR-T cellular kinetics (CK) shows rapid expansion and differentiation from a TSCM-like phenotype pre-infusion to an effector (TEFF) phenotype. Additionally, no dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) or severe CRS was reported. These results suggest that P-BCMA-ALLO1 is a safe and potent therapy, exhibiting an optimal profile characterized by a strong memory phenotype and robust functionality.

Results

Generation of P-BCMA-ALLO1

P-BCMA-ALLO1 was generated using a previously described non-viral process (Fig. 1A)7. For nonclinical characterization, lots were produced using a small-scale research process over 14 days, while clinical lots were produced under GMP conditions. Gene editing was robust, with a high efficiency observed prior to purification of TCR- cells, resulting in less than 2% TCR+ cells post-purification across 27 preclinical lots (Fig. 1B); the majority of cells were TCR– (mean = 98.6%) and β2M- (mean = 72.1%). CAR+ cell selection using a single dose of methotrexate (MTX) was highly effective, as evidenced by an average of 88.3% CAR+ cells (Fig. 1C)7. In terms of manufacturing, P-BCMA-ALLO1 demonstrated an average expansion of 6.93X from their initial cell counts across 27 preclinical lots evaluated (Fig. 1D). Post-cryopreservation and subsequent thaw, cell viability remained high, with a mean of 86.5% (Fig. 1E).

A T cells isolated from HDs were edited using the piggyBac DNA Delivery System and the CC Gene Editing system in a one-step electroporation process. This approach facilitated the stable integration of the CAR into the genome, along with inactivation of TCRαβ and MHC-1. Post-editing, cells were selected, expanded, purified to remove TCR- cells, and cryopreserved for future clinical use. B FCM analysis of CAR-T cells at harvest indicates that the majority of P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells were β2M-TCR-, with further enrichment following TCR- purification. C All P-BCMA-ALLO1 products exhibited high percentages of CAR+, TCR-, and β2M- cells. D The average yield of selected CAR+ cells at harvest was 7.0 ± 4.1 times the initial T cell count. E P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells demonstrated high viability 24 h post-thaw (n = 27 for (C–E). P-BCMA-ALLO1 are significantly less alloreactive compared to donor-matched unedited CAR-T without CC editing (β2M+TCR+) by either (F) the percentage of proliferating CAR-T (CTV-) in co-culture with irradiated PBMC in a MLR assay (n = 3 donors) or (G) the percent killing of CAR-T cells (n = 3 donors/targets) by two lots of donor-specific alloreactive T cells (effectors) at different effector to target (E:T) ratios. Statistical analyses in (F) and (G) was conducted using two-tailed student’s t-test and two-tailed paired t-test, respectively. All error bars in this figure represent standard deviation. FACS contour plots are from a representative sample. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ****: p < 0.0001. Data shown are for research lots. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The mitigation of alloreactivity from P-BCMA-ALLO1 (GVH) following TCR knockout (KO) was assessed using a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay. Three different preclinical lots were co-cultured for seven days with six different donor-mismatched irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), alongside unedited donor-matched CAR-T cells without CC editing (β2M+TCR+). While the unedited CAR-T cells exhibited alloreactivity against donor-mismatched irradiated PBMC, the TCR- P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells showed minimal reactivity against the same cells (Fig. 1F). To assess the effect of β2M KO on T cell-mediated killing of P-BCMA-ALLO1 (HVG), P-BCMA-ALLO1 (β2M-TCR-) and unedited CAR-T cells (β2M+TCR+) were simultaneously generated from the same donors. At the same time, effector cells were cultured for 14 days with irradiated PBMCs from the same donors to enrich for alloreactivity. These effectors were then co-cultured for 48 h with either P-BCMA-ALLO1 or unedited CAR-T cells to evaluate killing. T cell killing was significantly reduced with P-BCMA-ALLO1 compared to unedited β2M+ CAR-T cells (Fig. 1G). These data demonstrate that KO of both β2M and TCR-αβ help to mitigate any potential alloreactive HVG or GVH response.

Memory phenotype correlates with antitumor efficacy in a xenograft tumor model

The efficacy of P-BCMA-ALLO1 research lots was assessed through functional and phenotypic assays including in vivo antitumor potency assessments, with correlative analyses to identify key determinants of efficacy. A total of 27 research lots were produced from 24 randomly selected HDs (Supp. Table 1). For two donors (#10 and #11), two lots were produced from the same leukaphereses but underwent separate productions, while for another donor (#6), two lots were produced from leukaphereses collected one year apart.

Flow cytometry (FCM) analysis was conducted to determine the memory phenotypic composition of P-BCMA-ALLO1, defined by the expression of CD95+ cells for CD45RA, CD45RO, CD62L, and CD27. The subsets included TSCM cells (CD45RA+CD45RO-CD62L+CD27+), central memory T (TCM) cells (CD45RA-CD45RO+CD62L+CD27+), effector memory T (TEM) cells (CD45RA-CD45RO+CD62L-CD27-), and TEFF (CD45RA+CD45RO-CD62L-CD27-). Analysis revealed that most P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots exhibited a predominantly undifferentiated early memory state, with high proportions of TSCM (mean = 36.0%) and TCM (mean = 54.8%), and lower proportions of TEM (mean = 6.8%) and TEFF (mean = 2.3%) (Fig. 2A), with the bulk of TSCM coming from CD8+ T cells (mean = 47.1%, Supp. Figure 2). Notably, the frequency of CD45RA+CD62L+ cells did not significantly differ between the raw starting material and P-BCMA-ALLO1 (Supp. Figure 3A), indicating the preservation of an undifferentiated phenotype.

A Across multiple P-BCMA-ALLO1 research use lots, a high percentage of TSCM and TCM was observed. B These lots were evaluated for in vivo efficacy with a 5 × 106 P-BCMA-ALLO1 dose (n = 6–8 mice per group) infused into a xenograft RPMI-8226 tumor model in NSG mice, (C) which differentiated lots based on their tumor control derived from the area under the curve of the growth curve (ineffective or <50% tumor control, blue; effective or ≥50% tumor control, red). D The heatmap of Spearman’s correlations between memory phenotype, and activation and exhaustion markers measured by flow cytometry against P-BCMA-ALLO1 in vivo efficacy (n = 25-27 lots). (E) Single cell RNA sequencing of a smaller subset (n = 18 lots) revealed 7 unique clusters in UMAP space. Spearman’s correlations between (F) the frequency of the different cluster phenotypes or (G) enrichment scores for key memory or effector genesets against tumor control. H The tumor growth curve and (I) memory phenotype of peripheral blood CAR-T in vivo of an effective P-BCMA-ALLO1 lot (24, n = 6 mice per group for (H),(I)). J The memory phenotype of P-BCMA-ALLO1 found in bone marrow after the end of in vivo studies (28-49 days post CAR-T infusion). K Tumor growth in vivo dosed with an effective P-BCMA-ALLO1 lot (4), which, after completely controlling tumor by day 28, was rechallenged for another 32 d (n = 6 mice per group). The statistical analyses in (D), (F), and (G) were conducted using a two-tailed student’s t-test. Statistical analysis performed in (H) and (K) used a one-way ANOVA at the particular time point with Tukey’s test for pairwise comparison. All error bars in this figure represent standard deviation. *: p < 0.05, ****: p ≤ 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To explore how this undifferentiated state was maintained through P-BCMA-ALLO1 production, starting T cells were sorted into their memory subsets (naïve T cells (TN) + TSCM, TCM, TEM, TEFF) before initiating the production process. Five days later, the TN + TSCM subset showed a significantly higher percentage of CAR+ cells compared to the other groups, along with a greater total number of CAR+ cells, although the increase in total CAR+ cells was not statistically significant (Supp. Fig. 3B–D). These data suggest that TN + TSCM cells are preferentially transposed by sPB during P-BCMA-ALLO1 production, leading to an enriched TSCM population.

The in vivo antitumor potency of the 27 research lots of P-BCMA-ALLO1 was assessed using a BCMA+ RPMI-8226 xenograft model (Fig. 2B) at a dose of 5 × 106 CAR-T cells per mouse, with tumor control measured up to day 42 post CAR-T cell infusion. Significant variability in tumor control was observed across lots from different donors, ranging from complete tumor eradication to no measurable efficacy (Fig. 2C). Notably, the lots produced from the same donor exhibited similar in vivo efficacies, suggesting that donor variability may be a key determinant of product efficacy. This model’s consistency allows for rigorous analysis of in vivo efficacy determinants among different lots.

Phenotyping of memory, activation, and exhaustion states by FCM revealed that the frequency of memory CD8+ P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells significantly correlated with in vivo tumor control. Specifically, higher percentages of TSCM and CD8+ TSCM correlated positively with tumor control (Fig. 2D). Additionally, the percentages of CD8+ cells expressing individual memory markers such as CD27, CD127, and CCR7 also correlated positively with tumor control (Fig. 2D). Conversely, the frequency of CD4+ T cells negatively correlated with tumor control, although the correlation was not significant for CD8+ T cells. Further analysis of starting T cell phenotypes showed that the frequency of memory CD4+ T cells (TN/SCM or CD4s expressing CD27, CD127, CCR7) negatively correlated with tumor control (Supp. Fig. 4). Tim-3 expression also negatively correlated with in vivo efficacy in P-BCMA-ALLO1 (Fig. 2D). These findings suggest that a high frequency of memory CD8+ T cells in P-BCMA-ALLO1 is characteristic of effective lots, consistent with previous reports correlating memory CD8+ CAR-T cells with clinical response8,9,10,11,12.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) was used to investigate the phenotypic heterogeneity of P-BCMA-ALLO1 at the transcriptional level. A subset of lots (n = 18) was analyzed, revealing seven distinct phenotypes in Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) space, with the most prevalent characterized by early memory CD8+ T cells expressing CCR7, SELL, and TCF7 (Fig. 2E). Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA)13 assessed differential gene expression between TSCM and TEFF cells, confirming that early memory CD8+ and CD4+ T cells exhibited a more TSCM-like phenotype, while effector memory T cells displayed characteristics typical of TEFF cells (Supp. Fig. 7). The frequency of early memory CD8+ T cells identified by scRNAseq showed a positive correlation with tumor control, albeit not statistically significantly (Fig. 2F). In contrast, actively proliferating T cells marked by MKI67 expression and regulatory T (TREG) cells characterized by FOXP3 expression exhibited a significant negative correlation with tumor control. Further analysis using ssGSEA to evaluate memory or effector gene expression patterns derived from relevant literature sources showed that the average memory score correlated positively with tumor control, while the average effector or exhaustion gene expression score showed a negative correlation, though not statistically significant (Fig. 2G)14,15,16,17,18. These findings, combined with our FCM phenotyping data, underscore the association between CD8+ memory phenotype and in vivo antitumor potency, while highlighting the negative impact of TREG and exhaustion phenotypes on efficacy.

Beyond the memory phenotype, we investigated whether effective P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots possessed functional advantages in vivo associated with memory cells, including persistence, proliferation, homeostatic turnover in the absence of antigen (Ag), and responsiveness to Ag rechallenge14. To demonstrate these functionalities within P-BCMA-ALLO1, two separate in vivo studies were conducted using lots from donors 4 and 24, both of which achieved complete tumor control. For donor 24, robust expansion of CAR-T cells in peripheral blood coincided with tumor control (Fig. 2H). Phenotypic analysis revealed differentiation of these cells from TSCM to TEM and TEFF during the course of tumor control (Fig. 2I). As the tumor was controlled, T cell numbers contracted, maintaining a composition that reverted to the pre-infusion frequency of TSCM (Fig. 2I), indicating the ability of these TSCM to persist. Across the donor dataset, P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells trafficked to the bone marrow (BM), where evaluable CAR-T cells predominantly exhibited a TEM phenotype (Fig. 2J). In donor 4, P-BCMA-ALLO1 also achieved complete tumor control by day 28. Subsequently, mice were rechallenged with another RPMI-8226 tumor on the opposite flank at day 28, with age-matched NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice and unchallenged survivors serving as controls (Fig. 2K). At 60 days post-initial CAR-T cell infusion, no tumor growth was observed in both rechallenged and unchallenged survivors, indicating that persistent CAR-T cells retained the ability to rapidly respond to rechallenge and prevent tumor growth (Fig. 2K).

To further explore whether shifting P-BCMA-ALLO1 towards a TEFF phenotype would compromise its in vivo efficacy, we engineered a variant of P-BCMA-ALLO1 with a more differentiated phenotype (EffALLO) by introducing a CD28 switch receptor consisting of wild-type full-length CD28 fused with a C-terminal intracellular CD3ζ signaling domain, expected to enhance signaling and promote T cell differentiation during manufacturing (Supp. Fig. 8A). EffALLO exhibited increased CD28 levels and a more differentiated phenotype compared to donor-matched P-BCMA-ALLO1 produced in the same experiment (n = 3 donors, Supp. Fig. 8B–D). EffALLO showed heightened expression of effector markers, including increased production of interferon gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) upon stimulation, and elevated levels of the activation marker CD25, as well as exhaustion markers LAG-3 and Tim-3 (Supp. Fig. 8E, F), confirming its more effector-like phenotype. In vivo assessment using the RPMI-8226 model revealed that EffALLO displayed a significantly inferior tumor control and T-cell expansion (Supp. Fig. 8G–I). These findings indicate that deviating P-BCMA-ALLO1 from its memory phenotype compromises its antitumor properties. In summary, these results delineate the profile of effective P-BCMA-ALLO1, characterized by a memory phenotype conducive to proliferation, robust cytokine response upon Ag encounter, and long-term persistence.

Optimal P-BCMA-ALLO1 potency includes proliferative capacity, polyfunctionality, viability

To further elucidate the optimal potency profile of P-BCMA-ALLO1, we conducted a series of functional assessments focusing on key attributes such as proliferative capacity, polyfunctionality, and viability. Given the pivotal role of memory phenotype in P-BCMA-ALLO1 efficacy, we first evaluated their proliferative capacity using a serial restimulation assay. P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells were repeatedly stimulated every 5 days with irradiated K562 tumor cells engineered to express BCMA, continuing for multiple rounds until proliferation ceased (Fig. 3A). Remarkably, 23% (6/26) of P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots maintained their proliferative capacity through up to 16 rounds of rechallenge (80 days). By the third round of restimulation—typically the final round for most products—P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells exhibited a significant phenotypic shift from predominantly TSCM to TCM (Fig. 3B). The maximum fold expansion observed across all rounds of restimulation significantly correlated with the ability of P-BCMA-ALLO1 to control tumors in vivo (Fig. 3C). Next, we explored the functional heterogeneity and polyfunctionality of CD8+ P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells in response to K562-BCMA activation. Phenotypic clustering identified six distinct secretion profiles, with four driven by IFNγ and Granzyme B secretion (Fig. 3D, E). Notably, a subset of “super secreting” cells demonstrated high polyfunctionality, secreting significant levels of IFNγ and other cytokines, and their frequency within CD8+ cells correlated positively with in vivo tumor control (Fig. 3F). In contrast, populations secreting TNF and LTα did not show a correlation with tumor control. The polyfunctional strength index (PSI) further underscored this correlation, consistent with findings from clinical studies (Fig. 3G)19. P-BCMA-ALLO1 showed a different polyfunctional response to RPMI-8226 cells, in that PSI correlated negatively with tumor growth, although without statistical significance (Supp. Fig. 10A–C), and while IFNγ-secreting polyfunctional cells were detected, they separated into two distinct secretion profiles: one secreting GM-CSF and TNF which weakly correlated with tumor control (Supp. Fig. 10D); and the other secreting CCL3 which significantly negatively correlated with tumor control (Supp. Fig. 10E). The frequencies of these GM-CSF+TNF+ and CCL3+ super secretors are loosely correlated with memory and exhaustion marker expression in P-BCMA-ALLO1, respectively (Supp. Fig. 10F), suggesting that the type of cytotoxic response is critical to antitumor efficacy. Bridging these responses to two different tumor lines is the common presence of IFNγ and GM-CSF-secreting polyfunctional cells that correlate with memory phenotype in P-BCMA-ALLO1 and tumor control. Overall, these results emphasize the importance of proliferative capacity and polyfunctionality in the potency of P-BCMA-ALLO1, reinforcing the role of memory phenotype in effective antitumor responses.

A Serial restimulation of P-BCMA-ALLO1 with irradiated K562-BCMA cells distinguished lots based on their Ag-specific proliferative capacity. B After restimulation, P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells showed a more differentiated phenotype while predominantly retaining a TCM phenotype. C Maximum fold expansion from serial restimulation was significantly correlated with tumor control (n = 25 lots; ineffective or <50% tumor control [blue]; effective or ≥50% tumor control [red]). D, E Phenotypic analysis of single-cell cytokine secretion of CD8+ cells in P-BCMA-ALLO1 activated against K562-BCMA cells (E:T = 2) identified six distinct clusters with varied cytokine profiles among P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells (n = 21 lots). F The frequency of IFNγhi “super secretors” and (G) the PSI both positively correlated with tumor control. Statistical analysis performed in (C), (F), (G) used a two-sided t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Additional in vitro metrics, including viability and cytotoxicity, also correlated with in vivo tumor control (Supp. Fig. 11). Collectively, these findings characterize a potent profile for P-BCMA-ALLO1, marked by phenotypically and functionally early memory cells (TSCM/TCM) that can differentiate into mature cell types, persist in vivo, and exhibit extensive proliferative capacity, polyfunctionality, viability, and cytotoxicity.

Patient characteristics and study design for evaluating P-BCMA-ALLO1

Building on preclinical data that demonstrated a strong memory phenotype associated with CAR-T potency, we are currently investigating the clinical translatability of these findings through CK and other data from the ongoing Phase I clinical trial of P-BCMA-ALLO1 (NCT04960579). The primary objective of the trial is to assess the safety and determine the maximum tolerated dose of P-BCMA-ALLO1 using a dose-escalation approach. Secondary objectives include evaluating the anti-myeloma efficacy of P-BCMA-ALLO1 and examining the impact of cell dose and LD regimen on outcomes. Eligible patients are adults ( ≥ 18 years old), not pregnant, with RRMM as defined by the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG). Additional eligibility criteria include an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 0 or 1, prior treatment with a PI, IMiD, and anti-CD38 therapy. Importantly, prior exposure to BCMA-targeting therapies was allowed. As of the cutoff date of October 23, 2023, 34 participants were treated, with 33 evaluable for response assessment, each having a minimum follow-up of 4 weeks post P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion (Table 1). One participant was re-treated with P-BCMA-ALLO1. The median age of enrolled patients was 68 years (range 33–85), with 64% being female. The median time since diagnosis was 6.27 years (range 1.48–18.95 years), and 30% of patients exhibited high-risk cytogenetics. The median number of prior lines of therapy was 7 (range 2–17), with 39% having previously received prior BCMA CAR-T and/or anti-BCMA therapy.

The median time from enrollment to the start of LD was 1 day (range 0–10), and from enrollment to P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion was 7 days (range 5–15). Notably, none of the patients required BT, resulting in a 100% dosing rate for the ITT population.

In this study, 23 participants received a standard three-day LD regimen of 300 mg/m2/day Cy and 30 mg/m2/day Flu (Arm S), then administered varying dose levels of P-BCMA-ALLO1 (0.25 − 6 × 106 cells/kg) based on dose cohorts. This arm includes one patient who received a cohort 2 P-BCMA-ALLO1 dose (2 × 106 cells/kg). The patient was re-treated upon relapse with a second round of LD and a second P-BCMA-ALLO1 cohort 2 (2 × 106 cells/kg) cell dose. Another patient in Arm S received cyclic dosing where two P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells doses were administered following one round of LD. One Arm S participant was non-evaluable for response. Nine patients in Arm S received a target dose of 2 × 106 cells/kg (range 2.0 − 3.47 × 106 cells/kg). An additional eleven patients received an enhanced three-day LD regimen, with either 500 mg/m2/day (Arm A, n = 5) or 1,000 mg/m2/day (Arm B, n = 6) Cy alongside 30 mg/m2 Flu, followed by a target dose of 2 × 106 P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells/kg. In total, 20 participants (19 evaluable) were in dose cohort 2 that received a target dose of 2 × 106 cells/kg. All LD regimens were administered from day -5 to day -3 prior to a single intravenous P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion on day 0 (Fig. 4A).

A Treatment timeline for the Phase I trial of P-BCMA-ALLO1 (NCT04960579), including LD administered from days -5 to -3 prior to P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion on day 0. B ORR by treatment arm. C CK for Arms S, A, and B at the 2 × 106 cells/kg target dose, with Cmax typically achieved between days 7 and 14. D Median Cmax, Tmax, and AUC, highlighting a significant increase in Cmax and AUC in Arm B compared to S (n = 5-8 per treatment arm). E CAR-T cell phenotype tracking from peripheral blood over time, showing differentiation from a largely undifferentiated TSCM phenotype to more TEFF cells, aligned with CAR-T cell expansion. F Analysis of CAR-T cells in the BM, showing a significant proportion differentiating into TEFF cells. All error bars in (D) indicate range. Statistical analysis in (B) used Fisher’s exact test, and (D) employed Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s test for pairwise comparison. *: p ≤ 0.05, **: p ≤ 0.01. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

At the data cutoff, 4 lots of P-BCMA-ALLO1 were used to dose patients, all with high average frequencies of CAR+ cells (98.8%), high frequencies of KOs of CD3 (97.9%) and β2M (70.4%) (Supp. Table 3). On average, the majority of these cells were of a TSCM phenotype (42.0% of CD4, 67.9% of CD8) or a TCM phenotype (43.9% of CD4, 31.2% of CD8). These four lots were used to dose multiple patients each in this trial. Clinical lot #4 is derived from the same healthy donor as Donor 12 in preclinical lots (Supp. Table 1).

Preliminary safety evaluation of P-BCMA-ALLO1

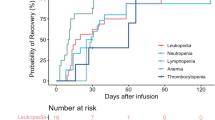

P-BCMA-ALLO1 target doses were escalated to Cohort 3 in Arm S without any dose-limiting toxicities (DLT) observed (Table 2). No GvHD was reported at any target dose level. No events of CRS grade > 2 were observed (n, (%): grade 1-2 CRS in Arm S: n = 3 (14); A: n = 1 (20); B: n = 3 (50)). The median time to CRS onset was 8 days (range 4–16). Two patients experienced Immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), both grade 2 or lower - one in Arm S and the other in B. Consistent with other CAR-T studies in MM, cytopenias were the most commonly observed toxicities1,2,3,4.

Efficacy and cellular kinetics of P-BCMA-ALLO1

In this preliminary analysis, antitumor activity was evaluated in 19 participants from Cohort 2 (2 × 106 cells/kg) across Arms S (n = 8), A (n = 5), and B (n = 6). The overall response rates were notably higher in Arms A and B, which received enhanced LD chemotherapy, compared to Arm S. Specifically, response rates were 0% in Arm S, 80% in Arm A (40% very good partial response [VGPR]; 40% partial response [PR]), and 83.3% in Arm B (33% stringent complete response [sCR]; 50% VGPR) (Fig. 4B). Importantly, responses were observed in two patients (2/11) who had previously undergone autologous BCMA CAR-T treatment (idecabtagene vicleucel and P-BCMA-101), both achieving VGPR.

CK of P-BCMA-ALLO1 from cells collected at successive follow-ups were analyzed quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for the CAR transgene and reported as copies per μg DNA and is independent of the actual dose administered. The peak expansion of P-BCMA-ALLO1, indicated by the maximum concentration of CAR-T cells (Cmax), was significantly higher in Arm B compared to S (Fig. 4C). The median time to reach Cmax (Tmax) was consistent between treatment arms, ranging from 10 to 12 days post-infusion. Furthermore, the area under the curve (AUC) of the P-BCMA-ALLO1 expansion curve, reflecting overall growth CK, was significantly higher in B patients compared to those in Arm S (Fig. 4D).

Given that the pre-infusion product of P-BCMA-ALLO1 is enriched with a high frequency of TSCM, and considering the established correlation between memory phenotype and clinical response8,9,10,11, we tracked the memory phenotype and differentiation at follow-up intervals through FCM. In one patient from Arm B who achieved VGPR, analysis of the P-BCMA-ALLO1 phenotype in the peripheral blood over multiple follow-ups showed that from day 10 to three weeks post-infusion, P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells, particularly the CD8+ population, differentiated from a TSCM-like phenotype pre-infusion to include more TEFF cells to control the tumor. By week 4, the percentage of TSCM cells partially recovered, indicating both persistence and homeostatic turnover characteristic of memory T cells (Fig. 4E). This persistence aligns with preclinical data demonstrating the homeostatic turnover of TSCM in P-BCMA-ALLO1 after complete tumor control (Fig. 2H, I). In another patient in Arm B who achieved sCR, BM aspirate (BMA) analysis at week 6 revealed that CAR-T cells persisted in the marrow compartment, coinciding with sCR at the time of marrow biopsy on day 42. Similar to observations in peripheral blood, the CAR-T cells in the BM differentiated into a large population of CD8+ TEFF at the expense of TSCM/TCM (Fig. 4F). These data suggest that the progenitor phenotype of P-BCMA-ALLO1 enables rapid expansion and differentiation into TEFF, while maintaining a population of stem-like cells that could contribute to long-term therapeutic efficacy.

Discussion

In this report, we introduce P-BCMA-ALLO1, an allogeneic CAR-T therapy for RRMM, and describe its optimal potency profile, characterized by a robust memory phenotype and polyfunctionality. Preliminary interim Phase I clinical data demonstrate strong anti-myeloma activity, trafficking to BM, and a favorable safety profile with enhanced LD. These properties align with nonclinical observations, particularly the high proportion of TSCM in P-BCMA-ALLO1, particularly in CD8+ T cells. The objective response rate (ORR) was ≥80% in patients receiving enhanced LD (A/B), likely driven by greater T cell expansion compared to those receiving standard LD (S). Clinically, P-BCMA-ALLO1 showed expansion from a predominantly ( > 90%) TSCM + TCM phenotype to a more TEFF phenotype, coinciding with clinical responses and demonstrating both proliferative capacity and multipotency. These findings are consistent with other studies where autologous CAR-T cells containing higher frequencies of TSCM + TCM differentiated into TEM + TEFF to effectively target tumors12. Supporting the CK data, preclinical studies revealed a significant correlation between the frequency of memory cells in P-BCMA-ALLO1, particularly CD8+ TSCM, and robust antitumor efficacy in vivo (Fig. 2). This suggests that TSCM-predominant CAR-T cells may enhance clinical potency, a correlation supported by other reports linking pre-infusion memory phenotype with clinical response in CAR-T therapy8,9,10,11. Conversely, the expression of T cell exhaustion markers like Tim-3 was negatively correlated with tumor control, consistent with previous findings20,21. Moreover, P-BCMA-ALLO1 persistence in the BM after tumor clearance, as observed in this study, mirrors preclinical observations and underscores the potential for stemness to translate into long-term therapeutic efficacy in a challenging alloreactive environment. This persistence of allogeneic TSCM in BM aligns with longstanding observations in transplant medicine22.

We further developed a functional profile for effective P-BCMA-ALLO1, emphasizing its proliferative capacity, viability, and cytotoxicity. The cytotoxicity and polyfunctionality of P-BCMA-ALLO1 are driven by the secretion of effector cytokines such as IFNγ and Granzyme B upon encountering the BCMA Ag. While not directly addressed in this study, these cytokines were also associated with Cmax in autologous CAR-T cells manufactured using the same sPB system (manuscripts in preparation). The importance of CAR-T cell polyfunctionality has been demonstrated in various studies, including those involving responders to axicabtagene ciloleucel19.

Interestingly, while a correlation was observed between pre-infusion TSCM levels in the CAR-T cell lot and in vivo antitumor potency, we did not find a significant correlation between the phenotype of the starting cell material prior to gene editing and antitumor control, despite maintaining the percentage of TN + TSCM (CD45RA+CD62L+) cells throughout manufacturing by the preferential transposition of those early cells by sPB and their subsequent expansion during manufacturing (Supp. Figure 3). This suggests that while selecting HDs with less differentiated T cells might be advantageous, the potency of P-BCMA-ALLO1 may also be influenced by the manufacturing process, including factors such as the gene delivery vector, gene editing method, timing, and media composition, or other HD characteristics. Notably, P-BCMA-ALLO1 is manufactured without any TSCM enrichment or cytokine supplementation, unlike some autologous CAR-T cells with less differentiated memory profiles, yet it still demonstrates functionality and effectiveness in vivo23,24.

A surprising finding of this study was the correlation between the frequency of CD4+ T cells, particularly memory CD4+ T cells, in both the P-BCMA-ALLO1 product and the starting T cells, and tumor growth (Fig. 2D). Literature reports on the influence of the CD4+/CD8+ ratio are mixed, with some studies showing that responders to tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel, anti-CD19) with sustained remission exhibit a high percentage of cytotoxic CD4+ T cells25, while others show no significant difference in the CD4+/CD8+ ratio between responders and non-responders26. While a preference for CD8+ T cells is shown, other factors, including the limitations of the NSG model and the potential desensitization to CD4+ cytokine support due to the absence of exogenous cytokines in manufacturing, may also contribute. The role of the CD4+/CD8+ ratio to P-BCMA-ALLO1 efficacy remains an important area for future investigation.

The safety profile of P-BCMA-ALLO1 suggests that a high percentage of TSCM in the product may contribute to the low incidence of CRS and other CAR-T therapy-related toxicities. No DLTs were reported, and there were few incidences of CRS and neurotoxicity (all grade ≤2), presenting a better safety profile than other BCMA-targeting CAR-T therapies and T cell engagers1,2,4,27. The observed toxicity profile is similar to, or better than, that of autologous anti-BCMA CAR-T cells non-virally manufactured with sPB (P-BCMA-101; 28% in all patients, all grade ≤2)28 The median time to CRS onset was 8 days post-infusion, which was comparably later than other BCMA-targeting CAR-T therapies1,2. It is possible that both the timing and lower severity of CRS are linked to the CK of TSCM expansion and differentiation. Additionally, the low percentage of TNF+/LTα+ secreting cells in P-BCMA-ALLO1, whose frequency did not correlate with antitumor potency, might also contribute to the reduced incidence of CRS29. The favorable safety profile has allowed for outpatient dosing in the clinical protocol.

Allogeneic therapies like P-BCMA-ALLO1 are designed to treat multiple patients from a single HD-derived lot, expanding access to CAR-T therapy while avoiding the challenges inherent to autologous CAR-T cell production. By knocking out both TCR-αβ and β2M in P-BCMA-ALLO1, the alloreactivity by and against P-BCMA-ALLO1 was significantly reduced, thereby mitigating these major risks of allogeneic therapy. The clinical benefits of P-BCMA-ALLO1 as an allogeneic CAR-T therapy became clear, as no BT was required prior to P-BCMA-ALLO1 treatment, resulting in 100% of the ITT patient population receiving cells as of the cutoff date of October 23, 2023. The median time from enrollment to the start of LD and P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion being 1 and 7 days, respectively. Alongside its favorable safety profile, the rapid treatment process highlights how P-BCMA-ALLO1 can overcome barriers to CAR-T therapy access. The “off-the-shelf” nature of P-BCMA-ALLO1 eliminates the complexities of supply chains and shipping associated with geographically distant apheresis and manufacturing sites, which limit access to autologous CAR-T therapy to select locations. In contrast, P-BCMA-ALLO1 can be ordered like any other “off-the-shelf” drug for immediate dosing.

So far, responses to treatment and T cell expansion have only been observed in cohorts receiving enhanced LD (A/B), suggesting that P-BCMA-ALLO1 requires more intensive conditioning for optimal expansion and efficacy. This observation aligns with previous clinical reports that patients receiving Cy/Flu had higher ORR compared to patients receiving Cy alone30. We hypothesize that the need for enhanced LD is related to natural killer (NK) cell depletion, although the exact immune composition in patients post-conditioning remains unclear. To mitigate potential NK-mediated cytotoxicity targeting MHC-I deficient CAR-T cells, we knock out β2M in P-BCMA-ALLO1 but do not sort for β2M- cells as we do with TCR, leaving a mixed population. Other approaches in allogeneic cell therapies include using anti-CD52 antibodies for additional lymphodepletion4,31,32. Further clinical development and analysis are needed to better understand the role of LD in P-BCMA-ALLO1 efficacy.

Several limitations exist in the preclinical work in this study. While the in vivo tumor model using NSG mice provides a controlled and consistent means of assessing CAR-T efficacy, it lacks a dynamic immune system with critical cell-cell interactions and cytokine support, as well as a challenging environment with alloreactive pressure. Although P-BCMA-ALLO1 demonstrated a lack of GvHD response in vitro, and no such responses were observed in the clinical trial, further studies are needed to understand the role of residual TCRαβ+ and β2M+ cells in P-BCMA-ALLO1 efficacy in more complex models. Additionally, P-BCMA-ALLO1 is generated using non-viral gene editing, which likely plays a significant role in maintaining its memory phenotype compared to traditional lentiviral approaches. Therefore, while our data are consistent with reports using lentiviral vectors, comparability with other CAR-T therapies must consider the method of gene editing and manufacturing process.

Overall, we demonstrate that P-BCMA-ALLO1 has a favorable safety profile and antitumor activity, with an optimal potency profile characterized by a strong memory phenotype, significant proliferative capacity, polyfunctionality, cytotoxicity, and high viability post-thaw. The high TSCM component of P-BCMA-ALLO1 functions as a prodrug, conferring multipotency to rapid expansion and control the tumor, as evidenced by our preliminary clinical data. Further analysis of P-BCMA-ALLO1 at later follow-ups and in additional patients may provide deeper insights into the persistence and maintenance of its memory phenotype and functionality.

Methods

Preclinical P-BCMA-ALLO1 production

P-BCMA-ALLO1 was produced for preclinical research as previously described7. Fresh leukopaks from HDs were sourced from various providers (HemaCare, Northridge, CA; Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA; Access Biologicals, Vista, CA; Oklahoma Blood Institute, Oklahoma City, OK; StemExpress, San Diego, CA; AllCells, Alameda, CA; see Supp. Table 1). Leukopak collection is compliant with all US requirements, specifically 21 CFR Part 1271 and the FDA guidance for industry, “Eligibility Determination for Donors of Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products (HCT/Ps)” (August 2007). Informed consent is obtained to ensure the donor comprehends and willingly agrees to the donation and the de-identified collection, use, and sharing of their health information as detailed in the consent document. This process mandates full disclosure of all potential risks and benefits, including any clinical, commercial, or research applications of the donated materials. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated via immunomagnetic positive selection using the CliniMACS Prodigy system (Miltenyi Biotec). The enriched T cells were thawed and allowed to recover overnight at 37 °C in T cell expansion medium. For each electroporation (EP) reaction, mRNAs encoding sPB (10 μg/2.5 x 107 cells), CC (20 μg/2.5 x 107 cells), a booster molecule (10 μg/2.5 x 107 cells), and synthetic chemically modified gRNA targeting the TRBC1, TRBC2, and B2M genes (4 μg/2.5 x 107 cells), along with a DNA PB transposon plasmid encoding a human variable heavy chain-based BCMA CAR, an inducible caspase-9 (iCasp9) safety switch (dimerizable with rimiducid [AP1903]), and a dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) mutein selection cassette, were preloaded into a Nucleocuvette (4 μg/2.5 x 107 cells, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). All plasmids and products thereof were generated and cloned at Poseida Therapeutics. T cells were then EP’d using the 4D-Nucleofector system (Lonza). Post-EP, cells from multiple reactions were pooled and cultured overnight in supplemented medium within a G-Rex culture vessel (Wilson Wolf, St Paul, MN). The following day, cells were activated and selected via the addition of MTX to deplete CAR-negative cells. The culture was maintained with regular fresh medium replenishment throughout the process. At harvest, the cell product underwent immunomagnetic depletion of residual TCR+ CAR-T cells to yield P-BCMA-ALLO1. Mock controls were prepared by EP’ing cells without nucleic acids. Following harvest, T cells were assayed by flow cytometry to measure KO efficiency, and phenotyped for markers of memory, activation, trafficking, and exhaustion. Viability was assessed using both the Luna cell counter (Logos Biosystems, Annandale, VA) and the NC-200 cell counter (Chemometec, San Diego, CA). Final P-BCMA-ALLO1 products were then cryopreserved.

Flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

FCM analysis was employed to analyze the memory phenotype of cells, characterized by positive CD95 expression in conjunction with markers CD45RA, CD45RO, CD62L, and CD27. Specifically, the subsets identified included: TSCM cells (CD45RA+CD45RO-CD62L+CD27+), TCM (CD45RA-CD45RO+CD62L+CD27+), TEM (CD45RA-CD45RO+CD62L-CD27-), and TEFF (CD45RA+CD45RO-CD62L-CD27-). For preclinical analyses, unedited T cells were rested for 48 h at 37 °C, while CAR-T cells were rested for 24 h at 37 °C in growth media (RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS]). Live cells were stained using a viability dye (Live/Dead Aqua; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Subsequently, live cells were stained with fluorescently conjugated antibodies (Biolegend, San Diego, CA; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ; Thermo Fisher) at various dilutions according to manufacturer’s recommendations in FACS buffer (phosphate buffered saline [PBS] with 2% FBS). Following a 30 min incubation, fluorescence was measured using either a Fortessa or Celesta cytometer (BD). Data were analyzed using FlowJo (BD). For CAR staining, cells were first incubated with biotinylated soluble BCMA protein in FACS buffer, followed by staining with fluorescently tagged streptavidin alongside other fluorescent antibodies. For FACS sorting, cells were sorted using a MA900 Cell Sorter (Sony Biotechnology, San Jose, CA) into RPMI-1640 media containing 10% FBS, kept at 4 °C for subsequent use.

For clinical samples, cells were thawed and washed with Pharmingen Stain Buffer (BD) before staining. CAR-T cells were identified using fluorescently labeled BCMA protein (Acro Biosystems, Newark, DE) and defined as live CD45+CD2+CD3-BCMA+ single cells. Replicates were acquired separately, and their data were concatenated for analysis. A biological positive control (transposed CAR-T cells), a biological negative control (HD PBMC), and a BCMA fluorescence minus one (FMO) control were included in all clinical sample experiments.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay

The potential of P-BCMA-ALLO1 to attack healthy T cells (GVH) was evaluated using MLR assays. P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells, along with donor-matched TCR+ controls as responders, were co-cultured with HLA-mismatched irrPBMCs from six different HDs (IQ Biosciences, Alameda, CA), which acted as stimulators. The irrPBMCs were labeled with CFDA-SE (Vybrant; Thermo Fisher), while P-BCMA-ALLO1 and TCR+ unedited CAR-T cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (CTV; Thermo Fisher). The responder cells were then co-cultured with the stimulators for 7 days (n = 4 per group) at a stimulator-to-responder ratio of 1:2. As controls, CAR-T groups were cultured alone to establish baseline proliferation levels, or in the presence of cytokines interleukin (IL)-2 (100 ng/mL), IL-7 (25 ng/mL), and IL-15 (25 ng/mL) to confirm their ability to proliferate (n = 2 per control group). On day 7, the MLR co-cultures were harvested and analyzed by FCM. We quantified the percentage of CTV- cells based on unstimulated controls, thus representing cells that undergo any level of proliferation in response to stimulation.

T cell killing assay

To assess whether P-BCMA-ALLO1 is susceptible to attack by healthy T cells (HVG), P-BCMA-ALLO1 and donor-matched TCR+ and β2M+ controls were generated as previously described (n = 3 donors). Simultaneously, irradiated PBMCs from the same donors were used to enrich alloreactive effector T cells from two separate HLA-mismatched donors. These effectors were co-cultured with irradiated PBMCs at a 1:1 ratio for 7 days, then co-cultured again with fresh irradiated PBMCs for another 7 days with IL-7 (25 ng/mL), and IL-15 (50 ng/mL), with media change as necessary. On day 14 of both CAR-T manufacturing and effector culture, P-BCMA-ALLO1 or unedited CAR-T were labeled with CTV and cultured with effectors at E:T ratios of 5:1 and 10:1 for 48 h. Counting beads (CountBright, Thermo Fisher) were added for absolute cell counts. T cell killing was then measured as the reduction of CTV+ CAR-T in co-culture relative to CAR-T in culture alone.

In vivo studies

All in vivo experiments were conducted at LabCorp following the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol #MI05 with euthanasia criteria for tumor burdens > 2000 mm3, which was never exceeded. Immunocompromised NSG mice were used for all studies. Six- to seven-week-old female NSG mice were subcutaneously implanted with 107 RPMI-8226 tumor cells into their flank. On day 6, mice with detectable tumors (75–125 mm3, n = 4–6 per group) were randomized into treatment groups. The following day, mice were infused with 5 × 106 P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells. Negative control groups received PBS injections. Tumor size was measured 2–3 times weekly for up to 7 weeks post-infusion. Blood samples were collected weekly and shipped on ice for FCM staining. Tumor control was quantified as the difference in the tumor growth AUC between the negative control and experimental groups, normalized to the negative control, and expressed as a percentage reduction in tumor growth. At the study endpoint or when tumors reached the endpoint size, whole blood, spleens, and BM were collected from each mouse and shipped on ice for FCM staining. Mice were euthanized by overexposure to CO2 followed by bilateral thoracotomy to confirm death.

To evaluate CAR-T cell response to tumor rechallenge, surviving mice from the initial challenge with RPMI-8226 (all with no detectable tumors) were rechallenged 4 weeks post-infusion with 107 RPMI-8226 tumor cells subcutaneously on the opposite flank. Age-matched naive NSG females served as controls, with one group receiving the same P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion and another group left unchallenged, continuing to measure the original tumor size. Tumor measurements were taken 2–3 times weekly.

Correlative analysis

Correlative analyses were performed using the rcorr function from the Hmisc package in R33. Spearman’s correlation coefficients (ρ) were calculated for all analyses, with statistical significance set at a p-value < 0.05 using a two-sided t-distribution.

Serial restimulation

The proliferative capacity of P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells was assessed through multiple rounds of CAR-mediated restimulation. Thawed P-BCMA-ALLO1 products were immediately co-cultured with irradiated K562-BCMA at a 2:1 E:T ratio in a 24-well plate containing growth media. Control cells consisted of P-BCMA-ALLO1 cultured without target cells. After 5 days of incubation at 37 °C, the cells were counted, phenotyped, and then restimulated in a new plate with fresh irradiated K562-BCMA cells. This restimulation cycle was repeated until the cells no longer exhibited expansion based on cell counts after another round of stimulation. The final number of stimulations and the maximum total fold expansion over all rounds of stimulations were recorded.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

In vitro cytotoxicity was evaluated using luciferase-expressing K562-BCMA target cells. Thawed P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots were co-cultured with K562-BCMA cells at various E:T ratios in phenol-free growth media. For unstimulated controls, K562 cells lacking BCMA expression were used. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a using a Synergy luminescent reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT). The percentage of killing was calculated as the reduction in luminescence relative to tumor-only controls.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was performed used to quantify cytokine production, specifically IFNγ, using a commercial kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Thawed P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots were co-cultured with K562-BCMA cells at various E:T ratios in growth media, with K562-only cultures serving as controls. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, supernatants were collected and stored at –80 °C. Upon thawing, supernatants were diluted 1:100, and cytokine levels were measured. Final concentrations of IFNγ were reported in pg/ml after comparison with a standard curve.

Single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq)

To assess the phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of P-BCMA-ALLO1, scRNAseq was performed. The procedures for cell collection, library preparation, sequencing, and read alignment were conducted by 3D Genomics (Carlsbad, CA) and Medgenome (Foster City, CA). Thawed P-BCMA-ALLO1 products were sorted for live cells using propidium iodide and collected into FACS buffer. Cells were loaded into gel bead-in-emulsions (GEM, Chromium, 10X Genomics). Following cell lysis and RNA reverse transcription, GEMs were broken, and barcoded complementary DNA (cDNA) was recovered. Libraries were generated using Illumina technology and quality-controlled with a Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent Technologies). The libraries were diluted to 4 nM, pooled, and sequenced on a NovaSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA; Supp. Table 2). Reads were aligned to the human reference transcriptome using CellRanger (10X Genomics, Pleasanton, CA), generating a matrix of cell-specific barcodes and gene expression counts.

Downstream analysis of scRNAseq data was conducted using the Seurat package in R34. Genes detected in fewer than three cells per sample were removed from analysis. Cells were filtered based on the following criteria: less than 8% mitochondrial genes, between 1000 and 60,000 total counts, and between 1000 and 8000 detected genes to exclude low-quality cells and doublets. Normalization was performed with the SCTransform function, regressing out variability associated with (1) mitochondrial counts35, (2) TRBC1, TRBC2, and B2M counts (targets of CC editing), and (3) sex-related genes XIST and RPS4Y1 to account for sex-based variability. The datasets were integrated based on 3,000 commonly variable genes36. Principal component analysis (PCA) and UMAP were conducted using 40 principal components. Unsupervised clustering analysis with a resolution of 0.1 generated clusters, which were identified through manual review of differentially expressed genes using Seurat. Additionally, ssGSEA13 was performed on log-normalized RNA counts using the GSVA package in R37. Gene sets included those from the literature14,15,16,17,18 and differentially expressed genes between TSCM and TEFF identified from bulk RNA sequencing on cells isolated from HDs, with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and a log2 fold change > 1.

Single-cell barcode chip (SCBC) analysis

SCBC technology was utilized to profile cytokine secretion at the single-cell level and assess polyfunctionality of CD8+ P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells19. P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells were thawed and stimulated with K562-BCMAs expressing GFP at a 2:1 E:T ratio for 24 h in growth media. As a negative control, CD8+ T cells were rested for 24 h without stimulation. After stimulation, CD8+ T cells were isolated by negatively sorting out GFP+ tumor cells and CD4+ T cells. These cells were then stained and loaded onto an SCBC chip (one chip per P-BCMA-ALLO1 lot) for imaging and measurement of cytokine secretion (Human Adaptive Immune Panel, Isospark, Isoplexis, Supp. Table 4). Polyfunctional cells, defined as those secreting more than one cytokine, were identified. The PSI of each sample was calculated as the percentage of polyfunctional cells multiplied by the sum of mean fluorescence intensities of each cytokine19. Cytokine profiles from each chip were visualized using UMAP and analyzed with unsupervised clustering using Phenograph (k = 500 neighbors). Clusters were manually identified to classify cells based on similar phenotypes.

Clinical study design and patients

P-BCMA-ALLO1 is currently under investigation in an ongoing Phase I, single-arm, open-label trial (NCT04960579) conducted at 14 sites across the United States. The primary objective is to assess the safety and determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of P-BCMA-ALLO1, with the DLT evaluated in patients with RRMM who have measurable disease and have previously received a PI, ImiD, and anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody therapy. This non-planned post-hoc analysis includes data from 34 participants enrolled in the study by Oct 23, 2023, who received P-BCMA-ALLO1 and had a minimum follow-up period of 4 weeks. The study includes 33 evaluable participants who had a minimum follow-up of 4 weeks post-infusion to be evaluable for response, and of that, one patient who was re-treated with P-BCMA-ALLO1. Efficacy analysis focused patients treated at a target dose level of 2 × 106 cells/kg, comprising 19 response-evaluable patients. Of the 51 patients screened, 39 were enrolled, and 38 underwent LD followed by P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion. Four patients with follow-up of ≤4 weeks were excluded from this analysis. Enrollment was open to patients with prior BCMA-directed therapies, including BCMA CAR-T cell therapy.

Eligible participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study enrolled males and females aged 18 years and older, diagnosed with active MM according to IMWG criteria. Participants were required to have an ECOG PS of 0 or 1 and measurable MM defined by at least one of the following: serum M-protein levels ≥ 1.0 g/dL, urine M-protein levels ≥ 200 mg/24 h, abnormal serum free light chain (FLC) ratio with involved FLC level ≥ 10 mg/dL, or BM plasma cells comprising > 30% of total marrow cells. Patients must have had relapse or refractory disease after at least three prior lines of therapy, including a PI, an ImiD, and anti-CD38 therapy, or be refractory to all three classes of agents after at least two prior lines of therapy, with disease progression within 60 days of their last treatment. Birth control was mandatory from screening throughout the first year post-administration of P-BCMA-ALLO1. Females of childbearing potential were required to have negative serum and urine pregnancy tests at screening and within three days prior to initiating LD therapy. Participants needed to be at least 90 days post-autologous stem cell transplant, if applicable, and demonstrate adequate organ function based on specific criteria: renal (serum creatinine levels ≤ 1.5 mg/dL and clearance ≥ 30 mL/min), hematologic (absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1000/μL, platelet count ≥ 50,000/μL, and hemoglobin levels ≥ 8 g/dL), hepatic (aspartate aminotransferase over serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase ≤ 3X the upper limit of normal and total bilirubin ≤ 2.0 mg/dL), and cardiac (left ventricular ejection fraction ≥ 45%). Participants must also have recovered from toxicities related to prior therapies, except peripheral neuropathy ≤ Grade 2 as per NCI CTCAE v5.0 criteria or to their baseline. The LD regimens evaluated included: Arm S – Cy: 300 mg/m2, Flu: 30 mg/m2; Arm A – Cy: 500 mg/m2, Flu: 30 mg/m2; Arm B – Cy: 1,000 mg/m2, Flu: 30 mg/m2. For each LD regimen, Cy and Flu were administered IV daily for 3 consecutive days (from days -5 to -3), followed by a single infusion of P-BCMA-ALLO1 on day 0.

Clinical study oversight

This study was sponsored by Poseida Therapeutics and conducted in collaboration with academic investigators, adhering to the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation, and the trial received approval from independent institutional review boards (IRB) at each participating site, including the University of California, San Diego; University of Maryland; Karmanos Cancer Institute; University of Kansas Medical Center; University of California, San Francisco; Vanderbilt University; University of Oklahoma; Houston Methodist; Advocate Health Care; SCRI San Antonio; SCRI St. David’s; University of Iowa; University of Cincinnati; and Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. The study did not utilize a data safety monitoring board. All authors attest to the accuracy of the data and adherence to the study protocol.

Clinical endpoints

The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate the safety and tolerability of P-BCMA-ALLO1, with a focus on DLTs. AEs and SAEs were recorded from screening through the month 36 study visit, disease progression, or participant withdrawal, whichever occurred first. AEs were graded according to the NCI CTCAE v5.0, while AEs related to CRS and ICANS were assessed using ASTCT consensus grading38. Investigators determined the causal relationship between the AE and P-BCMA-ALLO1 or LD therapy based on clinical judgment. Key secondary objectives included assessing the anti-myeloma effect P-BCMA-ALLO1 based on cell dose and study arm, as well as evaluating the impact of different LD regimens. ORR was assessed according to the IMWG Uniform Response Criteria39,40,41 and included sCR, CR, VGPR, and PR for both confirmed and unconfirmed responses. Additionally, select patients underwent MRD testing using next-generation sequencing (clonoSeq, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA) with a sensitivity threshold of 10-4.

Cellular kinetics in clinical study

Peripheral expansion of P-BCMA-ALLO1 cells from isolated PBMCs was quantified using a qPCR assay to determine transposon copies per μg DNA. Whole blood was collected into CPT tubes at clinical sites, and PBMCs were isolated and cryopreserved following standard operating procedures. Genomic DNA was extracted from PBMCs using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and transgene copies were assessed with a transgene-specific primer/probe set (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). qPCR was performed using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) in duplex reactions, with human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) as the internal reference target (TaqMan Copy Number Reference Assay, Thermo Fisher). Transgene copies were normalized to the input DNA quantity measured by Qubit (Thermo Fisher). The assay’s quantitative range for transgene detection was from 50 to 2 × 106 copies per reaction, with a lower limit of detection (LLOD) of 10 copies per reaction (100 copies per µg of genomic DNA). Biological positive controls (CAR-T cells), biological negative control (non-transposed cells), and non-template controls were included within all experiments. Each reaction was performed in triplicate on an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher). CK were evaluated over time and reported as Cmax, Tmax and AUCD1-Wk3.

Quantification and statistical analysis of preclinical data

Data points and error bars represent mean and standard deviation unless otherwise specified. Sample sizes are detailed in figure legends or text for each experiment. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05, with specific statistical tests described in figure legends, text, or method descriptions.

Clinical statistical analysis

This report includes data from an unplanned post-hoc analysis involving 34 participants. This cohort comprises one patient enrolled in cyclic administration (dose Cohort 2), one patient re-treated at dose Cohort 2, and one non-evaluable patient with ≤4 weeks follow-up. The interim safety analysis included all 34 patients who received P-BCMA-ALLO1 infusion (including re-treated patients) and had a minimum of 4 weeks of follow-up. The efficacy analysis focused on 19 response-evaluable patients treated at the target dose level of 2 × 106 cells/kg. Patient demographics included all individuals from the safety cohort, with the re-treated patient counted only once (n = 33). ITT analysis was based on enrollment.

Descriptive statistics are reported as medians with minimum and maximum values for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Investigator-assessed responses, including both confirmed and unconfirmed responses, were reported as ORRs and analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. CK were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad, Boston, MA), JMP Clinical 8.0 and JMP Pro 17.0 (SAS), or R with the ggplot2 package for data visualization42. All clinical data presented are based on a data cutoff of October 23, 2023.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The clinical trial is ongoing. Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient level clinical data through a data request platform. At the time of writing this request platform is Vivli (https://vivli.org/ourmember/roche/). For up-to-date details on Roche’s Global Policy on the sharing of clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: (https://go.roche.com/data_sharing). Anonymized records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche cannot, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient re-identification. Preclinical datasets presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon request. Raw sequencing data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, GSE280754: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE280754). All other data are available in the article and its Supplementary files or from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Berdeja, J. G. et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 398, 314–324 (2021).

Munshi, N. C. et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med 384, 705–716 (2021).

San-Miguel, J. et al. Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med 389, 335–347 (2023).

Mailankody, S. et al. Allogeneic BCMA-targeting CAR T cells in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: phase 1 UNIVERSAL trial interim results. Nat. Med 29, 422–429 (2023).

Bailur, J. K. et al. Early alterations in stem-like/resident T cells, innate and myeloid cells in the bone marrow in preneoplastic gammopathy. JCI Insight 5, e127807(2019).

Zelle-Rieser, C. et al. T cells in multiple myeloma display features of exhaustion and senescence at the tumor site. J. Hematol. Oncol. 9, 116 (2016).

Madison, B. B. et al. Cas-CLOVER is a novel high-fidelity nuclease for safe and robust generation of T(SCM)-enriched allogeneic CAR-T cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 29, 979–995 (2022).

Fraietta, J. A. et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemi. Nat. Med 24, 563–571 (2018).

Deng, Q. et al. Characteristics of anti-CD19 CAR T cell infusion products associated with efficacy and toxicity in patients with large B cell lymphomas. Nat. Med 26, 1878–1887 (2020).

Locke, F. L. et al. Impact of tumor microenvironment on efficacy of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy or chemotherapy and transplant in large B cell lymphoma. Nat. Med 30, 507–518 (2024).

Filosto, S. et al. Product Attributes of CAR T-cell Therapy Differentially Associate with Efficacy and Toxicity in Second-line Large B-cell Lymphoma (ZUMA-7). Blood Cancer Discov. 5, 21–33 (2024).

Biasco, L. et al. Clonal expansion of T memory stem cells determines early anti-leukemic responses and long-term CAR T cell persistence in patients. Nat. Cancer 2, 629–642 (2021).

Barbie, D. A. et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature 462, 108–112 (2009).

Kaech, S. M. & Cui, W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 749–761 (2012).

Wherry, E. J. et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 27, 670–684 (2007).

Quigley, M. et al. Transcriptional analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells shows that PD-1 inhibits T cell function by upregulating BATF. Nat. Med 16, 1147–1151 (2010).

Luckey, C. J. et al. Memory T and memory B cells share a transcriptional program of self-renewal with long-term hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3304–3309 (2006).

Gattinoni, L. et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat. Med 17, 1290–1297 (2011).

Rossi, J. et al. Preinfusion polyfunctional anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells are associated with clinical outcomes in NHL. Blood 132, 804–814 (2018).

Lamure, S., et al. Clinical and product features associated with outcome of DLBCL patients to CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy. Cancers (Basel) 13, 4279 (2021).

Finney, O. C. et al. CD19 CAR T cell product and disease attributes predict leukemia remission durability. J. Clin. Invest 129, 2123–2132 (2019).

Roberto, A. et al. Role of naive-derived T memory stem cells in T-cell reconstitution following allogeneic transplantation. Blood 125, 2855–2864 (2015).

Battram, A. M. et al. IL-15 Enhances the Persistence and Function of BCMA-Targeting CAR-T Cells Compared to IL-2 or IL-15/IL-7 by Limiting CAR-T Cell Dysfunction and Differentiation. Cancers (Basel) 13(2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 123, 3750–3759 (2014).

Melenhorst, J. J. et al. Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4(+) CAR T cells. Nature 602, 503–509 (2022).

Bai, Z. et al. Single-cell antigen-specific landscape of CAR T infusion product identifies determinants of CD19-positive relapse in patients with ALL. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj2820 (2022).

Moreau, P. et al. Teclistamab in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med 387, 495–505 (2022).

Costello, C. et al. Clinical Trials of BCMA-Targeted CAR-T Cells Utilizing a Novel Non-Viral Transposon System. Blood 138, 3858–3858 (2021).

Morris, E. C., Neelapu, S. S., Giavridis, T. & Sadelain, M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 85–96 (2022).

Turtle, C. J. et al. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 355ra116 (2016).

Metelo, A. M. et al. Allogeneic Anti-BCMA CAR T Cells Are Superior to Multiple Myeloma-derived CAR T Cells in Preclinical Studies and May Be Combined with Gamma Secretase Inhibitors. Cancer Res Commun. 2, 158–171 (2022).

Sommer, C. et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Allogeneic CAR T Cells Targeting BCMA for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Mol. Ther. 27, 1126–1138 (2019).

Harrell, F. E. Jr. Hmisc. Harrell Miscellaneous

Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495–502 (2015).

Hafemeister, C. & Satija, R. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome Biol. 20, 296 (2019).

Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 177, 1888–1902 e1821 (2019).

Hanzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinforma. 14, 7 (2013).

Lee, D. W. et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 25, 625–638 (2019).

Cavo, M. et al. Role of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a consensus statement by the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 18, e206–e217 (2017).

Rajkumar, S. V. Multiple myeloma: 2011 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 86, 57–65 (2011).

Kumar, S. K. et al. Natural history of relapsed myeloma, refractory to immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors: a multicenter IMWG study. Leukemia 31, 2443–2448 (2017).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. in Use R! (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016).

D’Agostino, M. et al. Second revision of the international staging system (R2-ISS) for overall survival in multiple myeloma: a european myeloma network (EMN) report within the HARMONY project. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3406–3418 (2022).

Palumbo, A. et al. Revised international staging system for multiple myeloma: a report from international myeloma working group. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 2863–2869 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by Poseida Therapeutics, Inc. We extend our gratitude to Luca Gattinoni, Leibniz Institute for Immunotherapy, for valuable discussions, manuscript review, and feedback. We also thank Leslie Weiss, Yening Tan, Yan Zhang, Elvira Argus, Yingying Zhao, Christine Domingo, Jessica Sparks and Nathan Kosick of Poseida Therapeutics for their contributions to data generation, as well as Nathaniel Tran, Ozzy Lagunas, Connor Reed, and Zachary Stephens of Poseida Therapeutics for their support in experiments during manuscript revision. Special thanks to: MedGenome for their assistance with bulk and single cell RNA sequencing; WuXi Biologics for producing some of the preclinical P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots. We are also grateful to Cody Fine and Mitra Banihassan (University of California San Diego, UCSD) for their help with sorting for experiments in manuscript revision. Their work was made possible by the UCSD Stem Cell Program and a CIRM Major Facilities grant (FA1-00607) to the Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine. We also acknowledge the participation and contributions of all patients, their families, caregivers, and the staff involved in the clinical trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J.S. was instrumental in developing the concept and platform for allogeneic CAR-T therapy as described in this study. H.T., S.A.C., J.C., and D.J.S. conceived of and designed the program for HD and product characterization. H.T. and S.A.C. designed experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data. H.T., S.A.C., M.R., K.S.M., B.S.C., A.B., M.J.C., A.L., and J.K. conducted experiments including plasmid design and generation, optimization of the P-BCMA-ALLO1 production process, production of preclinical P-BCMA-ALLO1 lots, and in vitro and in vivo characterization. H.T., K.S.M., B.S.C., and A.B. performed bioinformatics and statistical analysis for the preclinical data. J.D.E., K.M., and R.B. oversaw the clinical trial and collected data on patient demographics, treatments, adverse events, and outcomes. B.D., L.S., A.Ki., C.L.C., M.H.K., and A.R. contributed to the clinical trial at their respective sites. S.H., A.Kr., B.S., and C.E.M. conducted experiments on clinical samples, including CAR detection and T cell phenotyping. J.M. and H.N. performed statistical analysis on interim clinical trial results. H.T., S.A.C., R.B., J.C., D.J.S. prepared the manuscript with significant contributions from K.S.M., B.S.C., A.B., S.H., J.E. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided feedback.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.T., S.A.C., M.R., K.S.M., B.S.C., A.B., K.M., J.D.E., J.M., S.H., A.Kr., B.S., M.J.C., A.L., J.K., H.N., C.E.M., R.B., J.C., and D.J.S. were employees of Poseida Therapeutics during their contribution to this study. B.D. has received research funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Angiocrine Bioscience, Pfizer, Poseida Therapeutics, MEI Pharma, Orca Bio, Wugen, AlloVir, Adicet Bio, Bristol Myers-Squibb (BMS), Molecular Templates, Atara Biotherapeutics, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and has consulted for MJH Life Sciences, Arivan Research, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, ADC Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Caribou Biosciences, Roche, and Autolous Therapeutics. C.L.C. has received research funding from BMS, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and has consulted for BMS, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Kite Pharma. L.S. holds advisory board roles with Novartis, Johnson and Johnson, and BMS. A.R. has received research support from Novartis, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. M.H.K. and A.Ki. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Cirino Botta who co-reviewed with Anna Maria Corsale; Lydia Lee and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article