Abstract

Seawater evaporation-induced electricity generation (SEG) holds potential in alleviating global energy and freshwater demands. However, conventional SEGs suffer from non-selective ion transport in seawater, leading to severe Debye screening effect and low output current (<10 µA). To overcome this bottleneck, we develop an ion-engine hydrogel based solar-powered SEG (SSEG), achieving milliampere level peak current of 1.2 mA from seawater due to molecular-level ion control, surpassing previously reported SEGs by 1 to 2 orders of magnitude. Molecular dynamics simulations and Hittorf’s method confirm that the hydrogel dramatically enhances anion transference number (~0.83) while suppresses cation-induced Debye screening via chemical gating, which is attributed to synergistic effect of metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association. The integrated SSEG system operating outdoors can generate power up to 24 mW, sufficient to charge small electronics, while producing freshwater at a high-yield over 2.0 kg m-2 h-1. Additionally, the ion modulation mechanism boosts the regeneration potential of waste concentrated by-products in SSEG systems, enabling the recovery of up to 16.7 W m-2 of blue energy through reverse electrodialysis, improving sustainability and economic value. This work demonstrates an approach for developing off-grid integrated water-energy cogeneration systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transition of the global energy system towards low-carbon and renewable energy is highly imperative for sustainable future1,2. Nowadays, renewable energy accounts for approximately 30% of global electricity generation, and it must increase to 80% by 2050 to meet decarbonization goals3. The Earth’s hydrological cycle, absorbing 35% of incoming solar energy (~60 trillion kW annually), exceeds global human energy consumption by three orders of magnitude4. Hydrovoltaics, particularly power generation leveraging the electrokinetic effect at the liquid-solid interface during water evaporation and flow5,6, holds immense potential to accelerate renewable energy transition. However, most existing water evaporation-induced electricity generators7,8,9 rely on freshwater as energy carrier source, creating a trade-off between the freshwater consumption and electricity generation, thus limiting their scalability for applications.

The ocean, with an enormous area of 360 million square kilometers, serves as an essential energy reservoir for achieving carbon neutrality10,11,12. Seawater evaporation-induced electricity generation (SEG)13,14,15, an emerging water-energy coupling technology, has attracted considerable attention for its great potential to cogenerate green electricity and valuable freshwater. Recent efforts toward improvement of SEG performance have focused primarily on physical and structural modifications, such as optimizing solid-liquid interfacial interactions16,17, constructing micro/nanofluidic channels to promote ion movement18,19, and introducing asymmetric structures to create charge gradients20,21. The output voltage of SEG devices has increased from millivolt levels in individual units to several hundred volts in integrated systems. However, progress in output current remains significantly lagging, with most SEGs generating current below 10 μA, far below practical requirements. The limitation stems from co-directional migration of anions and cations (Na+, Cl−, K+, Mg2+, Br−, Ca2+, etc.) during seawater evaporation. As elucidated by the classic Gouy-Chapman-Stern model22,23, the non-selective ion transport forms a dense counterion cloud at the solid-liquid interface, causing severe Debye screening that neutralizes surface charges and suppresses streaming potential, posing a fundamental obstacle to advancement of SEG technology.

Addressing this obstacle demands a paradigm shift from passive structural optimization to active regulation of ion transport. For instance, ionic thermoelectric materials leverage thermal gradients (ΔT) via the Soret effect to drive specific ion diffusion24, while ion-selective membranes exploit concentration gradients (ΔC) to separate counterions25. Their efficacy is highly dependent on macroscopic gradients. Under near-isothermal evaporation conditions of SEG, both ΔT and ΔC are exceedingly weak, insufficient to overcome the strong electrostatic confinement within the Debye layer for effective ion separation. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation provides a powerful and sustainable driving force for SEG26,27, while concurrently offering the prospect of harvesting valuable freshwater and energy from its byproducts. However, effective strategies to decouple and control the water-ion interactions during interfacial evaporation are lacking, resulting in inefficient energy dissipation through non-selective charge neutralization. Consequently, constructing an integrated material system capable of actively orchestrating ion and water transport to achieve optimal energy conversion between power and water modules is highly desirable but extremely challenging.

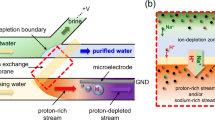

To overcome these challenges, this work introduces an innovative ion-engine hydrogel for solar-powered SEG (SSEG), capable of simultaneously harvesting streaming current, osmotic energy, and freshwater from seawater (Fig. 1A). The ion-engine hydrogel employs chemical gating, leveraging synergistic metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association to achieve precise molecular-level control over ion transport. During seawater evaporation, the selective gating facilitates an anion transference number (t_Cl− = 0.83) while effectively inhibiting cation-induced Debye screening (Fig. 1B). Consequently, the SSEG achieves a streaming current output of up to 1.2 mA under AM1.5 G illumination, exceeding previously reported devices by 1 to 2 orders of magnitude. Based on its multistage structure and ionic separation design, the SSEG system leverages the cation-rich residual seawater byproducts, coupling it with a Nafion-117 ion exchange membrane to generate clean osmotic energy output of up to 16.7 W m−2, further enhancing energy efficiency. Additionally, the SSEG can be flexibly assembled and integrated into systems to efficiently produce freshwater at a rate exceeding 2.0 kg m−2 h−1 while simultaneously powering electronic devices such as mobile phones and capacitors, demonstrating its significant potential for real-world applications and expanding the field of seawater-derived water-electricity cogeneration.

A Schematic of the hierarchically assembled SSEG device. The layered structure, from top to bottom, comprises a CNT layer (photothermal), a top electrode, a central ion-engine hydrogel, a bottom electrode, a foam separator, and a bottom ion-engine hydrogel layer that wicks seawater upward. B Diagram of the working mechanism of the SSEG. The positively charged ion-engine hydrogel functions as a chemical gate, facilitating anion diffusion while hindering cation migration during seawater evaporation process. This selective ion transport generates a streaming current via the electrokinetic effect. The rejected cations accumulate in the residual brine, which can be valorized to produce blue energy through reverse electrodialysis.

Results

Design of ion-engine hydrogels

The theoretical framework for streaming potentials (\({E}_{s}\)) and currents (\({I}_{s}\)) is described by the classical Helmholtz–Smoluchowski equation4:

where \({\varepsilon }_{r}\), \({\varepsilon }_{0}\), \(\Delta P\), \(\eta\), \({{{{\rm{k}}}}}_{b}\), \(Q\), \(\zeta\), and \({L}\) represent relative permittivity, vacuum permittivity, pressure difference, dynamic viscosity, electrical conductivity, volumetric flow rate, zeta potential, and channel length, respectively. As reported in previous studies5,28,29,30, electrokinetic phenomena, manifested as \({E}_{s}\) and \({I}_{s}\), are fundamentally governed by the material’s \(\zeta\), \(\Delta P\), and \(Q\). According to the electrokinetic effect31, the robust solid-liquid interactions at the charged interface facilitate charge separation, thereby accelerating the migration of target charges within the electric double layer. The high surface zeta potential diminishes the screening effect of counterions in the Stern layer, ultimately enhancing electrical output. To develop solar evaporators capable of efficiently harnessing the ionic potential energy inherent in seawater, the ion-engine hydrogel was synthesized from polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), copper(II) bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) (Cu(TFSI)2), and guanidinium chloride (GdmCl). The abundance of hydroxyl groups in PVA confers desirable characteristics such as hydrophilicity32, film-forming ability, and chemical stability, rendering it an ideal candidate for this application. Cu(TFSI)2 was selected as the ion source for binding to PVA due to its electrochemical stability and weak cation-anion coordination33, which promotes ion dissociation. The resulting hydrogels, denoted PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, exhibit strong coordination complexes formed between Cu2+ and the hydroxyl groups of PVA. This positively charged framework then attracts dissociated TFSI− anion to establish the electric double layer (EDL), while TFSI− acted as mobile counterions to diffuse within the EDL. However, the diffusion of the TFSI− is relatively slow due to their electrostatic interaction with the immobilized Cu2+ ions and steric hindrance. To address this limitation, the introduction of GdmCl into the system provides more dissociated anions34. The resulting hydrogel was named PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl. By introducing abundant ionic conjugation and ion-dipole interactions, this design is expected to significantly increase ionic conductivity and diffusion rates, ultimately leading to improved power generation performance.

To validate the design principle of PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using water as the solvent24,35. The interaction mechanisms were elucidated by analyzing the microstructure and diffusion dynamics of ions in both PVA/Cu(TFSI)2 (System I) and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl (System II). In System I, the dissociated Cu2+ ions coordinate with the hydroxyl (–OH) groups of PVA, forming a cation-centered Cu-OPVA structure (Fig. 2A), which effectively immobilizes the Cu2+ ions and hinders their migration. Upon the addition of GdmCl (System II), Gdm+ preferentially associates with TFSI−. This interaction releases TFSI− ions previously bound to Cu2+, resulting in a higher concentration of freely diffusing anions (TFSI− and Cl−) (Fig. 2B). Radial distribution function (RDF) and coordination number (CN) calculations reveal characteristic sharp peaks at 2.025 Å for Cu-OPVA and Cu-OTFSI (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that Cu2+ is simultaneously coordinated with PVA chains and TFSI− in the first coordination shell, with competition between –OH and TFSI−. The higher RDF amplitude for Cu-OTFSI compared to Cu-OPVA is attributed to the formation of Gdm+-TFSI− ion pairs. CN calculations indicate an average of 4.845 oxygen atoms surrounding each Cu2+ ion in PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, with 3.122 originating from TFSI− and 1.723 from PVA (Supplementary Table 1). Following the introduction of GdmCl (System II), the CN of Cu-OTFSI significantly decreased from 3.122 to 1.716, while the CN of Cu-OPVA remained largely unchanged, suggesting that GdmCl primarily influences the Cu2+-TFSI− interactions. Further analysis of RDF and CN of anions and cations reveals that the first peak of Gdm+-TFSI− appears at 2.425 Å (Supplementary Fig. 2), shorter than that of Cu2+-TFSI−. Furthermore, Gdm+-TFSI− exhibits a higher CN in System II, indicating a stronger electrostatic interaction between Gdm+ and TFSI−, which drives the observed structural changes.

A MD snapshots of PVA/Cu(TFSI)2 (System I). B MD snapshots of PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl (System Ⅱ). C RDFs and CNs of Cu2+-OPVA. D Binding energies of Cu2+-TFSI− and Gdm+-TFSI−, with an inset showing the corresponding structure and electrostatic potential distribution. E Diffusion coefficients calculated from MD simulations.

Ionic interactions dictate the alterations in solvent structure following metal coordination and ion-preferential association. Density functional theory calculations reveal binding energies of −3.86 eV and −6.37 eV for the Cu2+-TFSI− and Gdm+-TFSI− ion pairs, respectively (Fig. 2D). Electrostatic potential maps indicate a localized positive charge on the central atoms of both Cu2+-TFSI− and Gdm+-TFSI− ion pairs, resembling the structure observed in Cu-OPVA coordination (Supplementary Fig. 3). This tailored ionic configuration enhances the degrees of freedom for anions, effectively boosting their diffusion rates. To directly compare ionic transport characteristics, we calculated the self-diffusion coefficients (D) of ions in the two systems using the three-dimensional diffusion relationship derived from the mean-square displacement curves (Supplementary Fig. 4). Figure 2E presents the D values for Cu2+, TFSI−, and Cl−. Notably, in PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, the D value for TFSI− exceeds that of Cu2+. This disparity is further amplified in PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl, where the preferential association of Gdm+ with TFSI− liberates additional TFSI−, leading to an increase in its D value. Concurrently, this association results in a higher population of freely diffusing Cl− ions, significantly enhancing overall anionic conductivity. This differential ionic mobility between cations and anions in PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl imparts an “ion-engine” characteristic, enabling selective manipulation and utilization of cations and anions. To further validate the “ion-engine” strategy, we replaced the system with 3.5 wt% NaCl. The results reveal that the diffusion rate of Na+ is significantly restricted (Supplementary Fig. 5), while Cl− maintains the highest self-diffusion coefficient. Collectively, in our designed ion-engine hydrogels, the diffusion coefficients of anions are demonstrably higher than those of cations. This observation underscores the profound influence of solid-liquid interactions and ionic selectivity within the hydrogels, thereby enhancing the streaming potential and current generation in high-salinity solutions such as seawater.

Structure and ion selection performance of ion-engine hydrogel

Figure 3A illustrates the synthesized PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel, where the photothermal evaporation interface was constructed by incorporating carbon nanotubes (CNTs) (see “Methods”). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images reveal a uniformly interconnected, porous structure for both the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel and CNT layer. This dense polymer network confers both high tensile strength and a low swelling ratio to the hydrogel, ensuring excellent mechanical stability during the water-electricity cogeneration process (Supplementary Fig. 6). Elemental mapping confirms the homogeneous distribution of the elements C, N, O, F, Cu, S, and Cl within the hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. 7). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to investigate the metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association effects. High-resolution O 1 s spectra shows a redshift in binding energy upon the incorporation of Cu2+ (Fig. 3B). This shift is attributed to the coordination interaction between the oxygen atoms in the hydroxyl groups of PVA and Cu2+, which reduces the electron cloud density around the oxygen atoms36. The introduction of GdmCl induces further redshift, as Gdm⁺ preferentially associates with TFSI−, thereby reducing the competition for coordination with Cu2+ from TFSI−. This observation is consistent with findings from fluorine nuclear magnetic resonance (19F-NMR) spectroscopy and high-resolution N 1 s spectra (Supplementary Fig. 8). 1H-NMR spectroscopy provides further evidence for the ion-preferential association between Gdm+ and TFSI−. A 0.083 ppm downfield shift of the signal corresponding to the -NH2 group of GdmCl, from 6.567 to 6.650 ppm (Fig. 3C), indicates a weakened hydrogen bonding interaction due to the preferential association of the –NH2 group with TFSI−. These findings are further substantiated by vibrational modes of specific chemical bonds observed in Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 9). Collectively, these results confirm that strong metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association are established within the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel. This synergistic effect not only ensures the operational stability of the ion-engine hydrogel but also effectively prevents ion loss during seawater evaporation.

A Photographs (left) and corresponding SEM images (right) of the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel and CNT layer, with scale bars of 5 cm and 5 μm, respectively. B High-resolution O 1 s spectra of Cu(TFSI)2, PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl, showing a redshift in binding energy upon the incorporation of Cu2+. C 1H-NMR spectra showing the chemical shift for Gdm+, with an inset showing the locally magnified spectrum. D Zeta potential of the PVA, PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels. E Nyquist diagram of the PVA, PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels, with an inset showing an enlarged view for PVA/Cu(TFSI)2, and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels. F Ionic electrical conductivity of PVA/x Cu(TFSI)2 (bottom) and PVA/60 wt% Cu(TFSI)2-y GdmCl (top) hydrogels. G Schematic diagram (top left), photograph (top right), evaporation flux and corresponding salinity changes (bottom) in the residual solution over time using an ion-engine hydrogel under 3.5 wt% NaCl and 1 kW m−2 solar illumination. H IC reveals changes in Na+ and Cl− concentrations in residual solution. I Transference numbers of Na+ and Cl− determined by Hittorf method in an H-type electrolytic cell, confirming the high anion selectivity of the ion-engine mechanism, with an inset showing the schematic of the Hittorf method test. All the error bar represents the standard deviation of three-time measurements.

The remarkable ion selectivity and modulation of the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel are attributed to the synergistic effect of metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association, as evidenced by the dramatic shift in the zeta potential of the PVA surface from a weakly negative value to a highly positive value of +41.6 mV (Fig. 3D). This pronounced positive zeta potential is crucial for facilitating anionic transport36,37, which is essential for efficient power generation. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis further reveals that the charge transfer resistance of PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl is only 92.6 Ω (Fig. 3E), a stark reduction compared to the much higher values observed for pristine PVA (2601.2 Ω) and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2 (148.9 Ω). This reduction underscores the enhanced ionic conductivity introduced by the synergistic metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential interactions within the hydrogel. To further investigate the ionic conductivity, we quantified the influence of varying Cu(TFSI)2 and GdmCl doping levels (Fig. 3F). For the binary system PVA/x Cu(TFSI)2, where “x” represents the weight ratio (WR) of Cu(TFSI)2 to PVA, a clear trend was observed: the ionic conductivity (σ1) escalated with increasing Cu(TFSI)2 content, rising from 0.096 mS cm−1 for PVA to 1.012 mS cm−1 for PVA/60 wt% Cu(TFSI)2. However, exceeding 60 wt% copper salt loading compromised the structural integrity and processability of the samples. Thus, PVA/60 wt% Cu(TFSI)2 was selected as the benchmark for further investigation. As for the ternary hydrogel, PVA/x Cu(TFSI)2-y GdmCl, where “y” denotes the WR of GdmCl to Cu(TFSI)2, we employed PVA/60 wt% Cu(TFSI)2 as the base material. Remarkably, the introduction of GdmCl dramatically enhanced ionic conductivity. When “y” was increased to 40 wt%, the ionic conductivity (σ2) reached an impressive value of 1.472 mS cm−1. A slight decrease in σ2 to 1.283 mS cm−1 was observed for PVA/60 wt% Cu(TFSI)2-60 wt% GdmCl, likely due to the disordered migration of Gdm⁺ at higher GdmCl loadings, which impedes anion diffusion.

Furthermore, the high-performance of SSEG system relies on the synergistic interplay of several complex factors, including photothermal conversion, water transport, vapor generation, and resistance to salt crystallization. The photothermal effect in the SSEG device is attributed to the localized π-bonds of the CNT layer, which exhibit a high light absorption rate of over 96% across a broad wavelength range of 300–2500 nm (Supplementary Fig. 10). Meanwhile, the hierarchical architecture of the SSEG reduces heat conduction to bulk water, enhancing photothermal conversion and thermal utilization efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 11). The PVA-based hydrogel matrix, rich in hydrophilic hydroxyl (–OH) groups, facilitates rapid seawater transport to the evaporative interface (Supplementary Fig. 12). It also reduces the vaporization enthalpy of water molecules from 2240 J g−1 to 1485 J g−1 via the “intermediate water” effect (Supplementary Fig. 13), significantly boosting the evaporation rate. Consequently, under AM1.5 G illumination, the SSEG achieves a remarkable evaporation rate of 2.64 kg m−2 h−1 from simulated seawater (3.5 wt% NaCl solution), corresponding to a high energy efficiency of 91.6% (Supplementary Note 1).

As evaporation proceeds, the salt concentration in residual solution increases rapidly (Fig. 3G). Ion chromatography (IC) reveals that the Na⁺ concentration in the residual solution significantly increases from 10.2 g L−1 to 17.6 g L−1 after 4 h of evaporation (Fig. 3H), whereas the Cl- concentration increases relatively modestly. This disparity highlights the anion-selective nature of the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel. We further validated the selectivity based on Hittorf’s method through constant-current electrolysis (0.2 mA, 4 h) in an H-type electrolytic cell (Supplementary Fig. 14), using the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel as the separator (Supplementary Note 2). The calculated transmembrane ion transference numbers (t) are t_Na+ ≈ 0.17 and t_Cl− ≈ 0.83 (Fig. 3I), signifying that Cl− transport accounts for 83% of the ionic current, while Na+ is restricted to just 17%. Collectively, these findings substantiate the “ion-engine” mechanism of the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel, which effectively regulates the complex ionic environment in seawater and disrupts the cation-induced Debye screening effect, thereby ensuring efficient electricity generation. Furthermore, this ion regulation imparts exceptional resistance to salt crystallization by selectively impeding the influx of Na+. Remarkably, no salt crystal deposition was observed on the surface of the SSEG even after 100 h of continuous operation, while the E. R. remained consistently stable at ≈ 2.6 kg m−2 h−1 (Supplementary Fig. 15). Elemental mapping reveals a higher distribution density of Cl− and a lower concentration of Na+ within the hydrogel, further demonstrating the hydrogel’s “ion-engine” characteristics.

Electrical generation performance of SSEG

The SSEG device features an integrated design, where the top electrode is sandwiched between the photothermal layer and the upper ion-engine hydrogel, while the bottom electrode is positioned at the hydrogel-foam interface (Supplementary Fig. 16). The selected polyethylene terephthalate/CNT electrode exhibits excellent adhesion (4B rating, ASTM D3359) and superior corrosion resistance (Supplementary Fig. 17), ensuring robust stability during the prolonged seawater evaporation process. The electrical output performance was characterized using current-voltage (I-V) measurements (Fig. 4A). Under AM1.5 G illumination in 3.5 wt% NaCl, the I-V curve of the SSEG device (effective cross-sectional area of 4 cm2) exhibited quasi-linear behavior, yielding an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 0.68 V and a short-circuit current (Jsc) of 1.2 mA, corresponding to a remarkable current density of 3.0 A m−2. The maximum output power was determined based on the largest rectangular area on the I-V curve (shaded area in Fig. 4A), that is, when external resistance equals internal resistance. Maximum output power was determined to be 204 μW, a value confirmed by load-matching tests (Supplementary Fig. 18). As shown in Fig. 4B, Voc and Jsc of the SSEG were continuously monitored under AM1.5 G illumination over 24 h. Voc remained highly stable throughout the test, whereas Jsc dropped slightly over time after an initial stable output, attributed to the excessive accumulation of anions. Moreover, the SSEG demonstrates long-term operational stability under photothermal conditions and in seawater. A one-month durability test (30 cycles, 10 h/cycle, 1 sun) showed a stable output voltage (≈ 0.68 V) and evaporation rate (≈ 2.6 kg m−2 h−1, Supplementary Fig. 19). The internal impedance of the SSEG remained stable with less than 5% variation, demonstrating reliability of the entire system (Supplementary Fig. 20). FTIR spectroscopy confirmed that the key Cu-OPVA coordination and ion-preferential association structures within the hydrogel remained intact post-operation (Supplementary Fig. 21), further indicating the exceptional durability of the SSEG.

A Current-voltage curve of a single SSEG under AM1.5G illumination, with an inset showing the device schematic. The shaded area represents theoretical power output. B Voc and Jsc output from the SSEG over 24 h in artificial seawater under AM1.5G illumination. C Comparison of power generation performance using different hydrogel compositions. D Comparison of power output between the SSEG with a hierarchical structure and unlayered devices, with an inset showing the corresponding schematic diagram. E Evaporation rates, power output, Voc, Jsc, and osmotic energy (power density) of the SSEG compared to those of averages reported for existing water-energy cogeneration devices14,15,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. F Power generation performance of the SSEG under different solar illumination intensities. G Power generation performance of the SSEG in different liquids. H CV curves at scan rates of 10–100 mV s−1. I Schematic depiction of the working mechanism of the SSEG. J Numerical simulation of the Na+ and Cl− ion concentration distribution in the SSEG. All error bar represents the standard deviation of three-time measurements.

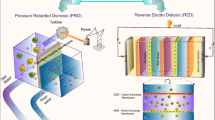

To elucidate the fundamental mechanisms underpinning this enhanced electrical output, we compared the performance of the SSEG with control devices based on PVA and PVA/Cu(TFSI)2 hydrogel. These control devices yielded markedly lower total power outputs of 0.12 and 75.4 μW, respectively (Fig. 4C). This compelling contrast strongly suggests that the synergistic effect between metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association within the SSEG is crucial for achieving the observed power output enhancement. Another key design feature of the SSEG is its hierarchical architecture, where the CNT layer is simply deposited on the surface of the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel (Fig. 4D). This structure decouples photothermal evaporation from streaming potential generation, thereby enhancing both ion selectivity and photothermal conversion efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 22). Comparative tests show the SSEG outperforms an unlayered device (where CNTs are evenly dispersed throughout the hydrogel), achieving a higher evaporation rate (2.64 vs. 2.42 kg m−2 h−1, Supplementary Fig. 23) and a fourfold higher total power output (204 vs. 50 μW). Concurrently with electricity generation, SSEG produces a cation-enriched concentrated brine. This byproduct was valorized by coupling it with a commercial Nafion-117 membrane to harness salinity gradient energy. Under the gradient between the brine and freshwater, this setup generated a Voc of approximately 164 mV and a Jsc of 12.8 μA. As external resistance varied, the current density gradually decreased, reaching a maximum osmotic power density of 16.7 W m−2 (Supplementary Fig. 24). A detailed energy balance analysis reveals that the SSEG system achieves a high total energy utilization efficiency of 93.3% under 1 sun illumination, combining a 91.6% solar-to-vapor efficiency with a 1.72% solar-to-electrical efficiency (Supplementary Note 3). This demonstrates the ability of the SSEG system to exploit the full potential of seawater by transforming a waste stream into a valuable resource.

To comprehensively evaluate and benchmark the electrical output performance of the SSEG, we compared its Voc, Jsc, and output power with those of recently reported hydrovoltaic systems (Supplementary Table 2). The theoretical maximum output power is defined as: \({P}_{\max }=\frac{{V}_{{oc}}*{J}_{{sc}}}{4}\). The Jsc and output power of the SSEG are 1 to 2 orders of magnitude higher than those reported in most hydrovoltaic devices. Furthermore, we compared its water-electricity cogeneration performance with those of state-of-the-art water-energy cogeneration devices (Supplementary Table 3). As shown in Fig. 4E, the SSEG achieves a Jsc of 1.2 mA, which is ≈11.4 times higher than the average of these recently reported devices (105.2 µA)14,15,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. The maximum power output (Pmax) of 204 µW is ≈14.9 times higher than the average (13.7 µW). The Voc and evaporation rate (E. R.) of the SSEG also exceeds the averages (0.52 V and 2.56 kg m−2 h−1). Moreover, the brine by-product, enriched with cations, can harvest significantly higher osmotic energy through reverse electrodialysis compared to traditional seawater/lake water systems, far exceeding the commercial standard for blue energy (5 W m−2). To sum up, the designed SSEG exhibits comprehensive advantages, demonstrating great potential in the field of water-electricity cogeneration.

The electrical output performance of the SSEG is intricately linked to water transport dynamics and solid-liquid interactions4,5, which are, in turn, influenced by factors such as solar irradiance, ionic concentration, and electrode configuration. The impact of solar illumination on the SSEG’s performance was investigated under intermittent illumination at 1 kW m−2 (Supplementary Fig. 25). Upon illumination, the Voc of SSEG rose to 0.68 V, subsequently decreasing to 0.33 V when the light was turned off. This observation is supported by the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski theory, which posits that accelerated liquid diffusion enhances ion diffusion and gradient distribution, thereby improving device performance. As anticipated, the SSEG’s power generation increases with rising solar flux. Specifically, the E. R. of the SSEG exhibits a linear increase as the solar intensity escalates from 0 to 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 W m−2 (Supplementary Fig. 26). However, at 2000 W m−2, an anomalous decrease in the electrical output of the SSEG is observed (Fig. 4F). This reduction is attributed to the excessively rapid loss of water from the hydrogel’s surface, which disrupts the internal ion gradient, thereby diminishing the efficacy of the electrokinetic mechanism. The impact of ionic concentration on the SSEG was evaluated using various aqueous solutions: deionized water, lake water, artificial seawater, and a 10 wt% NaCl solution. The Jsc exhibited two distinct trends. Initially, it increased from 1.05 A m−2 mA in deionized water to 1.05 A m−2 in lake water and 3.0 A m−2 in artificial seawater (Fig. 4G). This enhancement is attributed to the interaction of abundant anions in seawater within the hydrogel, generating a higher streaming potential and concentrated Coulombic field, as predicted by Debye–Hückel theory. However, with a further increase in salt concentration to 10 wt% NaCl, the EDL is compressed, resulting in a reduction of the Debye length. Consequently, a more tightly bound anionic layer is adsorbed onto the charged surface, which is less susceptible to shearing during flow, thereby diminishing the charge separation efficiency and reducing the electrical output.

To evaluate the potential influence of Faradaic current effects at the electrode-electrolyte interface on SSEG’s electrical output, we investigated the redox reactions in SSEG device configuration using cyclic voltammetry (CV). As shown in Fig. 4H, the quasi-rectangular CV curves observed at scan rates from 10 to 100 mV s−1 indicate that the charge storage process is predominantly governed by ion transport within the EDL, with minimal contribution from Faradaic reactions. Given that high flux evaporation is crucial for enhancing the streaming potential, we optimized the electrode design. A hollow-structured electrode was found to represent an optimal trade-off between efficient evaporation and charge collection (Supplementary Fig. 27). Furthermore, we investigated the impact of hydrogel thickness on SSEG’s electrical performance. The results revealed a positive correlation between Voc and increasing thickness, while Jsc exhibited a corresponding negative trend (Supplementary Fig. 28). This phenomenon is likely attributable to an increase in the device’s internal resistance with increasing hydrogel thickness.

The designed PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogel possesses excellent electrochemical properties and ion modulation capabilities, which facilitate the establishment of a bulk streaming potential within SSEG. The synergistic metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association effects accelerate anion diffusion rates and enhance ionic conductivity. During the phase transition from seawater to water vapor, a substantial accumulation of dissociated anions (e.g., Cl−, TFSI−, OH−) occurs at the top of the SSEG, resulting in a significant potential difference and a strong Coulombic field (Fig. 4I). Consistent with streaming potential theory, the top electrode of the SSEG acts as the negative pole, while the bottom electrode serves as the positive pole. Reversing the connection to a multimeter invert the signal polarity while maintaining the same absolute voltage (Supplementary Fig. 29), further corroborating the proposed working mechanism. Concurrently, cations, including Na+, are effectively confined within the residual seawater, representing a potential source of harvestable blue energy. Numerical simulations employing Nernst–Planck and Butler–Volmer equations validate the ion diffusion and potential difference within the SSEG. The resulting concentration profiles of Na+ and Cl− inside the electrolyte (Fig. 4J) are significantly different. Specifically, Cl− ions predominantly accumulate at the top electrode, while Na+ ions are confined near the bottom electrode, which is fully consistent with our proposed SSEG mechanism.

The application potential of SSEG for water-electricity cogeneration

To realize large-scale, high-performance water-electricity cogeneration platforms, we interconnected multiple SSEG devices in series and parallel configurations to meet practical demands. An integrated system was constructed to validate the feasibility of outdoor freshwater and electricity cogeneration from seawater (Supplementary Fig. 30). This platform, comprising 120 SSEG units fabricated using a “forest-like” assembly process (Fig. 5A), integrates four key modules: photothermal seawater evaporation, water vapor condensation and collection, evaporation-induced electricity generation, and osmotic energy harvesting. Simple series and parallel connections enable linearly scalable voltage and current outputs. As illustrated in Fig. 5B, 120 SSEG units connected in series or parallel readily generate a Voc of 75.8 V or a Jsc of 102.4 mA under sufficient outdoor sunlight (average Copt > 800 W m−2). For practical applications, a power supply system composed of 8 × 15 series-parallel connected SSEG units yields a peak electrical output of 5.12 V and 16.8 mA (Supplementary Fig. 31), capable of charging a 5 V/1 F commercial supercapacitor in only 400 s (Fig. 5C), demonstrating the ability to directly power electronics without a battery. Moreover, the water vapor from the integrated system condenses on the surface of a transparent acrylic plate via natural convection heat transfer and is collected as droplets flowing down an inclined surface (Fig. 5D), achieving a maximum freshwater production rate of approximately 2.0 L m−2 h−1. Analysis of the collected freshwater reveals near-complete removal (approaching 100%) for major salt ions such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, meeting global drinking water safety standards.

A Photograph with a scale bar of 10 cm and schematic illustration of the SSEG array. B Output voltage and current characteristics of the SSEG devices connected in various series (bottom) and parallel (top) configurations, with an inset showing the schematic of SSEG series-parallel structure. C Charging rate of a 1 F commercial capacitor using the SSEG array, with an inset photograph demonstrating the SSEG array’s capacity to power a mobile phone. D Optical photograph of SSEG system condensation process (top) and comparison of typical ionic concentrations in the initial seawater and the purified condensate collected after evaporation (bottom). E Schematic depicting the simulated all-weather solar illumination process on the SSEG system. F Stability assessment of four SSEG arrays (120 units total) during outdoor diurnal cycle, with a single seawater replenishment per cycle. G Voltage output and salinity of the residual concentrated seawater from a single cycle, with an inset photograph of a reverse electrodialysis device. All error bar represents the standard deviation of three-time measurements.

The evaporation and power generation performance of the integrated system was further evaluated under alternating light and dark conditions to simulate real-world, all-day scenarios (light incidence angle from 0° to 180°), as depicted in Fig. 5E. During the “daytime” period, as solar irradiance increased (Supplementary Fig. 32), the system’s evaporation rate rose from 0.32 kg m−2 h−1 (6:00 AM, Copt = 75 W m−2, 0°,) to a maximum of approximately 2.02 kg m−2 h−1 (12:00 PM, Copt = 896 W m−2, 90°). Subsequently, the decline in solar irradiance (12:00 PM to 6:00 PM, 90° to 180°) led to a gradual decrease in the evaporation rate to ~0.63 kg m−2 h−1. Consistent with the changes in evaporation rate, the Voc (ranging from 1.45 V to 5.32 V) and maximum power output (ranging from 5.3 mW to 24.0 mW) of the 8 × 15 series-parallel SSEG integrated system also varied accordingly (Fig. 5F). In stark contrast to the strong dependence of water evaporation-based electricity generation on daytime solar irradiance, the osmotic energy module can play a more significant role during the night. As light intensity gradually decreases from 90° to 180° (12:00 PM to 6:00 PM), the salinity of the seawater progressively increases, reaching a near-stable value during the nighttime (10:00 PM–6:00 AM). As shown in Fig. 5G, the corresponding salinity gradient energy exhibited a similar trend, with the measured Voc increasing from 132 mV (initial seawater, 6:00 AM) to 174 mV (12:00 PM), 244 mV (6:00 PM), and a peak of 263 mV (12:00 AM). This demonstrates an all-weather operational mechanism: leveraging solar-driven evaporation for simultaneous water and electricity production during the day and harnessing osmotic energy from the residual brine at night. This seamless integration effectively exploits the potential of seawater for water-electricity cogeneration. In contrast to complex conventional photovoltaic-driven reverse osmosis (PV + RO) systems discarding significant energy as waste heat and brine, the SSEG offers a fully integrated, passive solution. By simultaneously converting solar thermal energy to freshwater and chemical potential energy (in brine) to electricity, the single-unit device demonstrates a more holistic approach to resource utilization and ideal for off-grid water-energy cogeneration (Supplementary Note 4). Therefore, the SSEG-based integrated evaporative system simultaneously achieves freshwater production, evaporation-induced electricity generation, and salinity gradient power generation, offering a promising solution to the impending global water-energy crises.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed an ion-engine hydrogel for solar-driven integrated system, capable of simultaneously harvesting milliampere streaming current, osmotic energy, and freshwater from seawater. It is demonstrated that the ion-engine hydrogel works via chemical gating mechanism that leverages molecular-level synergy between metal-polymer coordination and ion-preferential association to precisely control and orchestrate ion transport. This design facilitates anion diffusion and effectively inhibits cation-induced Debye screening. Under AM1.5G illumination, the SSEG delivers a Voc of 0.68 V and a Jsc of 1.2 mA. Furthermore, the system ingeniously leverages the concentrated cations in the residual seawater to generate blue energy. This ion-engine mechanism selectively drives anions and cations for streaming potential generation and salinity gradient power generation, thereby maximizing the energy potential of seawater. Crucially, the SSEG demonstrates ease of integration and scalability, enabling effective water-energy cogeneration in outdoor environments. This work presents a promising solution to tackle future freshwater and energy challenges.

Methods

Preparation of materials

PVA (MW = 13,000–23,000) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Cu(TFSI)2 (98%), GdmCl (99%), and glutaraldehyde (25.0–28.0%) were obtained from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Hydrochloric acid and anhydrous ethanol were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Nafion-117 membrane was purchased from DuPont, USA. (Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/Poly(styrenesulfonate)) (PEDOT: PSS, 1.3–1.7% solid content) and conductive CNT ink was purchased from Alibaba (China). All reagents were used as received without further purification.

Fabrication of PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels

PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels were fabricated using a solution-casting and freeze-thaw method. Typically, an 8.5 wt% PVA solution was prepared by dissolving PVA powder in a 1 wt% HCl aqueous solution at 90 °C with continuous stirring until fully dissolved. Subsequently, desired amounts of Cu(TFSI)2 and GdmCl were sequentially added to the PVA solution and stirred until dissolved. Finally, a 1 wt% glutaraldehyde solution was introduced as a crosslinking agent. The resulting solution was cast into polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) molds. To induce physical-chemical crosslinking and create a porous structure, the molds were subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. Each cycle consisted of freezing at −20 °C for 4 h, followed by thawing at room temperature for 1 h. The hydrogel compositions were defined as follows: for binary hydrogels, denoted as PVA/x Cu(TFSI)2, “x” represents the weight percentage of Cu(TFSI)2 relative to the total weight of PVA and Cu(TFSI)2. For ternary hydrogels, designated as PVA/60 wt% Cu(TFSI)2-y GdmCl, “y” represents the weight ratio of GdmCl to the added Cu(TFSI)2.

Fabrication and assembly of SSEG devices

The SSEG devices were assembled in a layered architecture comprising the ion-engine hydrogel, a photothermal evaporation layer, and two electrodes. The assembly process was as follows: first, the PVA/Cu(TFSI)2-GdmCl hydrogels precursor solution was cast into custom-designed PTFE molds. The top electrode was then immediately placed on the surface of the precursor solution. Next, a portion of the same precursor solution was mixed with 0.5 wt% CNT powder (as the photothermal agent) to form a slurry, which was then cast as a 1 mm thick layer on top of the electrode. This created a hierarchical, pre-gelled assembly. Subsequently, the entire mold was subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles (freezing at −20 °C for 4 h, thawing at room temperature for 1 h per cycle) to simultaneously form the porous hydrogel and integrate all components. After demolding the integrated structure, the bottom electrode was attached to the bottom surface of the ion-engine hydrogel to complete the SSEG device. The electrodes were fabricated by uniformly brush-coating a conductive CNT ink (doped with 10 wt% PEDOT: PSS) onto perforated PET films for efficient interfacial charge transfer and collection. The SSEG’s fabrication process, based on a simple, one-pot synthesis and low-energy freeze-thaw crosslinking, is designed for scalability and is compatible with industrial roll-to-roll manufacturing, indicating a viable path to cost-effective production (see Supplementary Note 5 for a cost analysis).

Material characterizations

The morphology and elemental composition of the materials were analyzed using a SEM (Hitachi SU-8100). Zeta potential measurements were conducted using a NanoBrook Zeta PALS (Brookhaven Instruments). Spectral infrared emissivity was determined using a FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet iS50, Thermo Fisher). LF-NMR measurements were performed on a 22.4 MHz NMR analyzer (NMI20-Analyst). The solar absorptance of the samples was recorded using a UV–Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (Agilent Cary 5000). XPS data were acquired using an ESCALAB 250 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ion concentrations were measured using an IC (Thermo Fisher Aquion, Wanton 883).

Performance evaluation of the SSEG system

Photothermal evaporation experiments were conducted using a CEL-HXF300-T3 Xe lamp as a simulated solar source. Infrared thermal images were captured using an infrared camera (FOTRIC 320). Real-time mass changes of the solar-driven water evaporation generator (SSEG) during evaporation were monitored using a precision electronic balance (QUINTIX35-1CN). All electrical measurements were recorded in real-time using a RIGOL 3068 multimeter controlled by a LabView-based data acquisition system. CV measurements were performed using an electrochemical workstation (CHI760E, CH Instruments).

Computational details

Computational details of the theoretical simulations are given in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Note 6). The theoretical simulation configurations are provided in Source data file.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Rode, A. et al. Estimating a social cost of carbon for global energy consumption. Nature 598, 308–314 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Mitigation of China’s carbon neutrality to global warming. Nat. Commun. 13, 5315 (2022).

The International Vienna Energy and Climate Forum, About IVECF. Retrieved 2025, from https://www.ivecf.org/about/

Wang, X. et al. Hydrovoltaic technology: from mechanism to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 4902–4927 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Emerging hydrovoltaic technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1109–1119 (2018).

Fang, S., Li, J., Xu, Y., Shen, C. & Guo, W. Evaporating potential. Joule 6, 690–701 (2022).

Xue, G. et al. Water-evaporation-induced electricity with nanostructured carbon materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 317–321 (2017).

Deng, W. et al. Capillary front broadening for water-evaporation-induced electricity of one kilovolt. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 4442–4452 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Multistage coupling water-enabled electric generator with customizable energy output. Nat. Commun. 14, 5702 (2023).

Werber, J. R., Osuji, C. O. & Elimelech, M. Materials for next-generation desalination and water purification membranes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 18 (2016).

Zhang, R. et al. Antifouling membranes for sustainable water purification: strategies and mechanisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5888–5924 (2016).

Mao, Z. et al. Passive interfacial cooling-induced sustainable electricity–water cogeneration. Nat. Water 2, 93–100 (2024).

He, N. et al. Ion engines in hydrogels boosting hydrovoltaic electricity generation. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2494–2504 (2023).

Chen, Y., He, J., Ye, C. & Tang, S. Achieving ultrahigh voltage over 100 V and remarkable freshwater harvesting based on thermodiffusion enhanced hydrovoltaic generator. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400529 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Polyelectrolyte hydrogel-functionalized photothermal sponge enables simultaneously continuous solar desalination and electricity generation without salt accumulation. Adv. Mater. 36, 202401171 (2024).

Ren, Q. et al. Nanoporous hydrogels with tunable pore size for efficient hydrovoltaic electricity generation. Adv. Mater. 37, 2508391 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. Microbial biofilms for electricity generation from water evaporation and power to wearables. Nat. Commun. 13, 4369 (2022).

Ma, Q. et al. Rational design of MOF-based hybrid nanomaterials for directly harvesting electric energy from water evaporation. Adv. Mater. 32, 202003720 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Unipolar solution flow in calcium–organic frameworks for seawater-evaporation-induced electricity generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 1690–1700 (2024).

Kong, H. et al. Mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures for boosting electricity generation. ACS Nano 17, 18456–18469 (2023).

Liu, Z., Xie, J., Xu, J., Wang, Q. & Liu, G. Evaporating hydrovoltaics with asymmetric electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 477, 143742 (2024).

van der Heyden, F. H. J., Stein, D. & Dekker, C. Streaming currents in a single nanofluidic channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 116104 (2005).

Lu, S.-M. et al. Understanding the dynamic potential distribution at the electrode interface by stochastic collision electrochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12428–12432 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Exceptional n-type thermoelectric ionogels enabled by metal coordination and ion-selective association. Sci. Adv. 9, eadk2098 (2023).

Pan, W. X. et al. Scalable fabrication of ionic-conductive covalent organic framework fibers for capturing of sustainable osmotic energy. Adv. Mater. 36, 202401772 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. An integrated system with functions of solar desalination, power generation and crop irrigation. Nat. Water 1, 716–724 (2023).

Yang, B. et al. Flatband λ-Ti3O5 towards extraordinary solar steam generation. Nature 622, 499–506 (2023).

He, T. et al. Fully printed planar moisture-enabled electric generator arrays for scalable function integration. Joule 7, 935–951 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Transfer learning enhanced water-enabled electricity generation in highly oriented graphene oxide nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 13, 6819 (2022).

Li, X., Li, R., Li, S., Wang, Z. L. & Wei, D. Triboiontronics with temporal control of electrical double layer formation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6182 (2024).

Wang, C., Gao, Q. & Song, Y. Electrokinetic effect of a two-liquid interface within a slit microchannel. Langmuir 39, 17529–17537 (2023).

Kang, J. et al. Mucosa-inspired electro-responsive lubricating supramolecular-covalent hydrogel. Adv. Mater. 35, 202307705 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Reversible copper cathode for nonaqueous dua-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, 202212191 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Strong tough thermogalvanic hydrogel thermocell with extraordinarily high thermoelectric performance. Adv. Mater. 35, 202300696 (2023).

Zhang, Q.-K. et al. Homogeneous and mechanically stable solid–electrolyte interphase enabled by trioxane-modulated electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 725–735 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Spatially regulated water-heat transport by fluidic diode membrane for efficient solar-powered desalination and electricity generation. Nat. Commun. 16, 5050 (2025).

Hu, G. et al. All-in-one carbon foam evaporators for efficient co-generation of freshwater and electricity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2423781 (2025).

Ming, Z. et al. Photothermal-responsive aerogel-hydrogel binary system for efficient water purification and all-weather hydrovoltaic generation. Adv. Mater. 37, 2501809 (2025).

Long, J. et al. A high-efficiency system for long-term salinity-gradient energy harvesting and simultaneous solar steam generation. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2303476 (2025).

Sun, Z. et al. Achieving efficient power generation by designing bioinspired and multi-layered interfacial evaporator. Nat. Commun. 13, 5077 (2022).

Ge, C. et al. Fibrous solar evaporator with tunable water flow for efficient, self-operating, and sustainable hydroelectricity generation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2403608 (2024).

Kong, H. et al. Enhancing electricity generation from water evaporation through cellulose-based multiscale fibers network. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155872 (2024).

Wan, Y. et al. Bird’s nest-shaped Sb2WO6/D-Fru composite for multi-stage evaporator and tandem solar light-heat-electricity generators. Small 20, 2302943 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Bioinspired and 3D-printed solar evaporators for highly efficient freshwater-electricity co-generation. Mater. Horiz. 12, 5211–5224 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Achieving efficient multifunctional platform utilizing sugarcane for water-electricity cogeneration and dyes reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 505, 159258 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFB2502104, 2022YFA1602700, 2024YFF0506000), National Science Foundation of China (22375089, 22035005), the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangsu Provincial Department of Science and Technology of China (BE2022332), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX25_0267).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T. and L.Q. initiated and guided the research. Y.C. designed and performed the experiments. S.T. and Y.C. wrote and revised the manuscript. C.Y. conduct theoretical simulation. C.Y. and J.H. gave advice on experiments. Y.C. and C.Y. contributed equally to this work. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript. S.T. and L.Q. supervised the entire project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Cheng-Liang Liu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Ye, C., He, J. et al. Ion-engine hydrogel based solar desalination for water-electricity cogeneration with milliampere level current. Nat Commun 16, 10321 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65280-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65280-3