Abstract

Rotors are common in nature — from rotating membrane-proteins to superfluid-vortices. Yet, little is known about the collective dynamics of heterogeneous populations of rotors. Here, we show experimentally, numerically, and analytically that at small but finite inertia, a mixed population of oppositely spinning rotors spontaneously self-assembles into active chains, which we term gyromers. The gyromers are formed and stabilized by fluid motion and steric interactions alone. A detailed analysis of pair interaction shows that rotors with the same spin repel and orbit each other while opposite rotors spin-pair and propagate together as bound dimers. Rotor dimers interact with individual rotors, each other, and the boundaries to form chains. A minimal model predicts the formation of gyromers in numerical simulations and their possible subsequent folding into secondary structures of lattices and rings. This inherently out-of-equilibrium polymerization process holds promise for engineering self-assembled metamaterials such as artificial macroscale proteins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Life is too complicated to be assembled manually1. From the nanoscopic starting point of the lipids that comprise the cell and the DNA molecules holding the blueprints of each organism’s design, to the final macroscale product of the organism itself, there are many length scales and billions of molecules participating2. Life is also inherently out of equilibrium and forms far more complex structures than the crystals expected for atomistic systems at low temperatures3. A prototypical example is proteins, which are self-assembled hierarchically on the molecular scale, first forming chains and then folding into secondary and tertiary structures that can function as intricate molecular machines4.

A growing body of research in recent years has been devoted to the study of self-assembly out-of-equilibrium. Yet, when the building blocks are isotropic, most of the resulting structures have been crystals5,6,7,8. Symmetry breaking is possible with an external field, such as electrostatic chains that align along field lines9,10, Janus particles with electrostatic imbalance11, active shakers12,13, magnetic dipoles14 or patchy colloids15.

Despite the fundamental role of fluid dynamics in biological systems, hydrodynamic interactions have received limited attention in the study of active self-assembly. Notably, hydrodynamic structure formation by rotating objects has been garnering increasing interest. For example, synthetic rotors driven by a magnetic field16,17,18,19,20 or light21, living rotating matter22,23, fluids or elastic materials with odd viscosity18,24,25,26, dry rotating matter27,28 or rolling particles,29,30. These systems are ubiquitous in nature, ranging from the geological immensity of hurricanes to the biological intricacies of rotating proteins within cellular membranes and extending even to the quantum realm31. Historically, the behavior of rotors has been examined under conditions of negligible viscosity, dating back to Helmholtz32,33,34. More recently, studies have addressed settings of negligible inertia35,36,37,38, notably in biological contexts like ATP synthase proteins39,40. However, the intermediate Reynolds number regime, where both viscous and inertial forces play significant roles, remains relatively uncharted20,41. Here, complexities arise due to the nonlinearity of the Navier–Stokes equations, leaving our understanding of this regime limited. Within this regime, research involving small spinning magnetic particles has demonstrated the formation of lattice structures16,42,43, highlighting the interesting dynamics that emerge in such systems.

Common to all the aforementioned instances is that the units creating the self-organization are driven in the same direction. A question arises: what unique properties will be observed in a mixture of binary rotors, where some spin clockwise while others counter-clockwise? At intermediate Reynolds, this is still unknown. Both in the limit of an ideal fluid with no viscosity and in the limit of purely viscous fluids, the equations of motion have time-reversal symmetry. Theoretical studies of binary rotors in these two limits have shown that the two populations separate and dense clusters of same-spin rotors are formed34,35. In fact, even completely dry opposite rotors separate27,44. The intermediate regime is qualitatively different from both limits since time reversal symmetry is no longer obeyed.

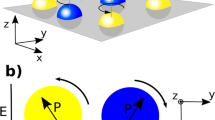

Here, we show that when inertia is small but not negligible, the resulting structures are very different — mixed-sign circular rotors self-assemble in a hierarchical manner, reminiscent of polymerization, but driven by fluid flow and steric interactions alone — first, rotors spinning clockwise and counter-clockwise attract, spin-pair and form bound dimers. Dimers then assemble into longer active chains. The chains, which we term gyromers (gyroscopic polymers), are stabilized by their activity (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Movie 1). To study the stability and origin of gyromer formation, we developed a test bed that enables controlling both the direction of rotation and the initial position of each individual rotor. Following Grzybowski, Stone, and Whitesides42, we analytically describe the velocity field of numerous spinning bodies within an intermediate Reynolds number regime, where viscosity remains the dominant force, and inertia is a perturbation. We conduct numerical simulations that qualitatively reproduce the experimental results. We determine that gyromer stability is decreased with increasing the variance in angular velocities of individual rotors.

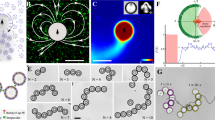

a A single rotor floating at the air-oil interface. b PIV analysis of the flow induced by a single rotor shows a tangential flow field. Zoom in shows velocity streamlines extracted from imageJ (top) and from PIVlab images (bottom). c Two same-sign rotors spiral out (orbit around each other and repel). Dots are tracked trajectories. Plus (minus) marks counter-clockwise (clockwise) rotation. d Two counter-rotors rotate counter-clockwise (cyan), and clockwise (pink). The rotors self-propel and attract. e–f Nine same-sign rotors starting from a centered random configuration form a hexagonal lattice. g, h Snapshots of seven rotors (four pluses and three minuses) starting from a centered random configuration, a single gyromer of all seven rotors is assembled. Once formed, the gyromer is stable and stays intact. Insets show intermediate times. The scale bar is 3 cm in all figures.

Results

Our rotors are brushless motors enclosed in 3D-printed cylindrical shells that allow them to float at the oil-air interface. A 3D-printed propeller is attached to the motor’s bottom pin so that the two parts counter-rotate (Fig. 1A). The rotation direction can be switched by reversing the battery wiring. Rotors spinning counter-clockwise (clockwise) are marked in cyan (pink). The resulting tangential flows were characterized using Particle Image Velocimetry (Fig. 1B). Full experimental details are provided in the Methods and Supplementary Information.

The bath is continuously monitored from above by a camera. When placed in the oil bath, the rotors spin at about 7 rpm (Ω ≈ 0.7 rad/s). We test two viscosities — high viscosity μ = 1 Pa⋅s, and low viscosity μ = 0.06 Pa⋅s. The Reynolds number, a measure of inertial forces compared to viscous ones, is \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=\rho \Omega {a}^{2}/\mu \approx 0.2\) for the high viscosity and \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\approx 3\) for the low viscosity. We find that, even though the Reynolds number is small, inertia is not negligible in both cases. In fact, it changes the behavior of the system qualitatively. Two rotors at zero Reynolds number maintain a fixed distance, they do not draw nearer nor drift apart35,39,40—same-sign rotors orbit around each other, and opposite-sign rotors propagate. When inertia is included (see also ref. 20, or activity, see ref. 37), it adds radial forces reminiscent of electrical charges—same sign rotors orbit and also repel, tracing a growing spiral (Fig. 1C); opposite sign rotors propagate and also attract (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Movie 2). The dynamics are predicted by the theoretical model described below.

At higher numbers of rotors, we first tested self-assembly of same signed rotors into lattices (Fig. 1E, F), reproducing the lattice formation first observed in ref. 16, though here no magnetic interactions are present. We then tested a mixed population of rotors. The particles self-assemble into active chains (gyromers). Gyromers are constantly assembled and disassembled due to interaction with other rotors or with the boundaries. We commonly see pair-switching or companion stealing. Even-numbered gyromers self-propel in a direction perpendicular to their axis with a speed that decreases with the number of monomers (an infinite gyromer will be stationary). Odd-numbered gyromers orbit around their center (see Fig. 1H), with an angular velocity that decreases as 1/N3, where N is the number of rotors in the gyromer, see analysis below. Small changes in the spin of the rotors cause deviations from this ideal behavior. Gyromers are stable until encountering other rotors or the boundaries. Odd-numbered gyromers are stable for a longer duration since they are less prone to interact with the boundaries. As demonstrated in Fig. 1, at a low concentration (7 rotors), all the rotors assemble into a single gyromer. Once formed, the gyromer remains stable for the lifetime of the rotors’ batteries (~2 h).

The boundary in our system has a critical role in facilitating the creation of self-assembled structures. Without it, assuming an infinite space, even-numbered gyromers propagate far away. Initially, we designed either a circular container or a flower-shaped boundary45, but rotors were hydrodynamically attracted to the boundary and tended to stay there46. To eliminate attraction, we designed a boundary of an inverse flower-like shape. This unique shape, designed by principles outlined in refs. 47,48, creates effective repulsion and brings rotors back into the pool.

Modeling minimal inertia

A single rotor far from boundaries stays static. When placed in a bath with other rotors it is advected by the flow created by them. In this region of the Reynolds number, the flow is governed mainly by viscous forces, but not only. We account for inertia by expanding the Navier–Stokes equations to a first order for a small but finite Re. In this limit, the equations are linear, and we can write u = us + ui, where us is the part coming from the Stokes equations and ui is the inertial correction. The flow field of a single rotor in a viscous fluid is49

where Ω is the spin of the rotor, and Cs is a prefactor of O(1). Two identical, same-sign rotors in this viscous regime orbit around each other with an angular velocity, \(\dot{\theta }\), given by

while maintaining the initial distance between the rotors, r. When inertial effects are included, the second rotor adds a correction to the above flow, giving a lift force resembling the Magnus effect. Solving the Navier–Stokes equations under a small but finite Reynolds number for a spinning disk in the shear rate created by a second, faraway disk gives the leading order correction to a viscous flow, which is radial and has the scaling16,42,50 (Supplementary Discussion)

where Ci is a prefactor of O(1). Due to the linearity in this regime, the velocity of the jth particle, uj, is a superposition of the flow created by other particles. In complex notation zj = xj + iyj (where xj and yj donate the position of the jth rotor), and using Eqs. (1) and (3) we can compactly describe the dynamics of the rotors. Switching to dimensionless form by taking z → z/a, Ωi → Ωi/Ω0, where Ωi is the ith rotor’s own spin, Ω0 is the typical magnitude, and t → (CsΩ0/a3)t, we get

where β = CiΩ0/(aCs) ∝ ρΩ0a2/μ is proportional to the Reynolds number up to a multiplicative prefactor of O(1), and signifies the importance of inertial interactions compared to viscous ones.

Two key assumptions were made here: First, we assumed that the rotors act as rotating disks. The use of self-spinning brushless motors in an infinite fluid results in a torque dipole along the Z-axis, as illustrated in Fig. 1A. It is, therefore, not immediately apparent that the magnitude of the angular velocity of a pair of rotors should indeed scale as Eq. (2). However, the vicinity of the propeller to the bottom of the container dampens its decay46, as we have verified from PIV measurements (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, the dynamics are governed by the upper cylinder. Second, Eq. (3) is the far distance approximation of the flow, though in practice, often the rotors are not far. Certainly, this is not correct for nearest neighbors in a gyromer. To verify the validity of both assumptions when rotors are distant, we analyze the dynamics of two same-sign rotors.

Solving analytically Eq. (4) for two rotors gives

where we have chosen Ω1 = Ω and Ω2 = γΩ. Note that the dimensionless distance between rotors only depends on the inertial term since the distance stays constant when β = 0. The distance grows for same-sign rotors (γ > 0) and decreases for opposite-sign rotors (γ < 0). Conversely, the orbiting angular velocity over time only depends on the viscous term (it is independent of β), and is inversely proportional to the distance between the rotors to the 3rd power. We experimentally tested the dynamics of several two same-sign rotors with γ ≈ 1. Figure 2A shows the angular velocity of the pair with a power law of three for both the high viscosity bath, and the low viscosity bath in the inset, as predicted by Eq. (6). Figure 2B shows that the separation distance to the fourth power is linear with time, as predicted by Eq. (5). Equations (5) and (6) were used in order to extract the experimental value of β from the graphs presented in Fig. 2 (Supplementary Discussion). This resulted in β = 0.323 ± 0.057 for μ = 1 Pa⋅s, and β = 4.71 ± 0.42 for μ = 0.06 Pa⋅s.

Main plots (insets) are from the high (low) viscosity bath. a Orbit angular velocity as a function of distance for two same-sign rotors in a log-log plot. Overlay of five (two) experiments at different shades of gray. Solid red lines mark the analytical prediction of \(\dot{\theta }\propto 1/{r}^{3}\) (Eq. (6)). b Distance to the fourth power versus time for the same experiments of two same-sign rotors. The red solid lines are linear fits, verifying Eq. (5). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As we advance to study the interaction involving multiple rotors, we will compare our system to two well-known equilibrium systems. The first is charged particles, which also repel (same sign) or attract (opposite sign) and are prone to form ionic crystals51. The second system that bears a resemblance to ours is that of magnetic dipoles, which are known to form chains and rings52,53. For more than two rotors, solving Eq. (4) analytically becomes challenging. Instead, we will leverage the insights gained from the two-rotor scenario and introduce the four-rotor and six-rotor interaction experimentally, numerically and use linear stability analysis.

Four rotors

Two rotors of opposite sign attract and propagate in space. In fact, in our experiments, spin pairing is very common. Once the rotors make contact, they advance in space as a bound dimer. To study the interaction between four rotors, we initilized two rotor-dimers such that they advance toward each other, as shown in Fig. 3A. The two pairs collide in a formation resembling an ionic crystal of plus and minus charges (Fig. 3B). However, unlike static ionic crystals, in our experiments, these lattice formations are never stable and quickly break into two new pairs of rotor-dimers (Fig. 3C). This effect is purely due to the dynamic nature of the interactions. Unlike static lattices, the forces governing the system include not only attraction and repulsion between particles but also angular forces that break the symmetry causing the crystal to disperse. The pairs reorient due to interaction with each other or with the walls (Fig. 3E) until reforming into a 4-rotor gyromer (Fig. 3F). Once formed, the gyromer is stable for a long time (~half an hour, Supplementary Movie 3). Simulations of rotors were performed by propagating Eq. (4) using either a 5th or a 2nd order Runge-Kutta scheme in Python (Supplementary Discussion). The simulations reproduce the experimental results taking β to be either 0.8 (Fig. 3J, L) or 80 (Fig. 3K). The arrows overlaying Fig. 3K are the analytical solution for the velocities initially and at steady-state. Notice how the viscous forces drive the outer and inner pairs apart, but the inertial forces have a stabilizing downward component.

a Initial position of two dimers advancing towards each other. b The four rotors collide and form a structure similar to an ionic lattice. c The lattice is unstable and immediately breaks into two new pairs of dimers, advancing in ninety degrees compared to the initial pairs. d The two dimers advance in space until reaching the boundary. e The dimers turn due to the shape of the boundary and advance towards each other. f The dimers meet each other in a way that enables the formation of a 4-gyromer (tetramer) which self-propels in space. g Ring initial formation. The inset shows a static magnetic ring. h The ring breaks into three dimers that propagate forward (i) until they reach the boundary (later forming longer gyromers). j Simulation of two dimers colliding and switching pairs with β = 0.8. k Simulation of a 4-gyromer advancing through space (β = 80). Arrows are analytic solutions of the velocity field initially and at steady-state. Blue arrows indicate the viscous part, and yellow the inertial part. l Simulations of an initial ring structure of six rotors with β = 0.8 break into three dimers as in the experiment. The scale bar is 4 cm in all figures.

Ring formation

Rotor-dimers are a common and relatively stable feature of our system. We therefore wanted to compare it to another system that forms chains — magnetic dipoles. To that end, we examined an initial ring formation, as depicted in Fig. 3G–I. The ring quickly disperses into smaller “building blocks" of rotor-dimers. Subsequently, these dimers attract and eventually create larger gyromers. This behavior is starkly different from static magnetic dipolar systems, where ring formations remain stable (as seen in the inset of Fig. 3G). At the lower viscosity, we observe that rings still disperse but are stable for longer durations.

The self assembly of multiple rotors

Up to this point, we have discussed simple and engineered cases of rotors. We now seek to discover general and statistical properties of gyromer formation, starting from random initial conditions. First, we find that the angular velocity of gyromers in the high viscosity bath scales as 1/N3, where N is the number of rotors in the gyromer as seen in Fig. 4A. In this regime, gyromers are straight, and inertial interactions maintain the structural integrity of the chain without contributing to its angular velocity (similar to the two-rotor case, see Eqs. (5) and (6)). The angular velocity is thus governed by the viscous interactions, and so \(\dot{\theta } \sim 1/{r}^{3}\). Let us consider the angular velocity of the rotor next to the center (all rotors have the same angular velocity, so we can choose the rotor that is most convenient). In a long gyromer, velocities of its left and right nearest neighbors cancel exactly, and so do next-nearest, etc. (see gray ellipse in cartoon inset in Fig. 4A), and all that is left are the two most distant rotors, at a distance L ~ N/2. Of these two, the closer one is more dominant, determining the direction and magnitude of rotation, giving \(\dot{\theta }\propto 1/{N}^{3}\).

a Angular velocity magnitude of gyromers as a function of 1/N3, where N is the number of monomers in the gyromer. Error bar is the standard deviation across the run. b Average chain length (in units of rotor diameter), after reaching steady-state, as a function of the total number of rotors in the bath. At low viscosity (β = 5, blue squares), and for lower concentrations of the high viscosity (β = 0.3, circles), a linear trend is shown. At higher concentrations for β = 0.3, the average decreases considerably. Red triangles are engineered initial conditions, starting from a line; circles and squares indicate random initial conditions. Two typical snapshots from experiments are shown. Red dotted lines link values obtained for random I.C. with those of line I.C. c Phase-space of formations from simulations showing a disordered state in the viscous limit (cyan), lattices at higher area fractions and inertial forces (blue), and gyromers in the intermediate regime (red) and at low and intermediate area fractions for high β. Experimental values are plotted as `x’s on top (in red since they are all gyromers). The background color is according to the average gyration length of the formations in simulations divided by the total number of rotors, N, in each formation. For gyromers, Rg ∝ N (red), whereas for lattices we expect \({R}_{g}\propto \sqrt{N}\), and indeed get lower values (blue). Snapshots from simulations are on the right, showing the different phases. d Snapshots from experiments starting from random initial conditions with 11 and 20 rotors in the high viscosity (β = 0.3). Highlighted are the formed gyromers (the scale bars are 4 cm). Middle panels are snapshots from experiments in the low viscosity (β = 5). e Simulations with inertial to viscous ratio comparable to the experimental ones (β = 0.8 or β = 2) show gyromer formations highlighted in colors for β = 0.8, and branched and curved gyromers are observed at β = 2. f, g Analytic streamlines around a gyromer of six rotors, showing flow lines along which a positive rotor would be advected. Two values of β are shown, 100 and 0.8. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Second, with increasing concentration, more monomers are available, enabling longer chains to form more rapidly—but also to dissociate more quickly (Supplementary Movie 4). It is, therefore, unclear a priori what concentrations will produce longer gyromers. We conducted experiments with increasing numbers of rotors, and analyzed gyromer lengths in each frame. We observe that, after reaching steady state, in the high-viscosity regime (β = 0.3), the average gyromer length first increases, see Fig. 4B. At low concentrations, for odd numbers of rotors, a steady state is reached with a single gyromer; for even numbers, the gyromer breaks when reaching the boundary. At higher concentrations, the system enters a dynamic steady state where gyromers continuously collide and reassemble, but the average gyromer length is constant N ~ 2. In contrast, at lower viscosity (β = 5), a single long gyromer tends to form even at higher concentrations (see snapshots in Fig. 4D), although the resulting structure is notably less straight. In this regime, where inertial interactions are stronger, we observe the emergence of new structures—both in simulations and in experiments—that are absent in the high-viscosity case. These include branched polymers and intermediate ring-like formations, Supplementary Movie 5. The size of the gyromers in this regime can be characterized by their radius of gyration, analogous to molecular polymers, defined as \({R}_{g}=\sqrt{\sum {\vert {{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}-{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}\vert }^{2}/N}\,/a\), where rcm denotes the center of mass.

Comparing experimental results to simulations at different concentrations shows similarities and differences (Supplementary Movies 6, 7). Using inertial values in the range (β ∈ [0.8, 1]), we start to observe gyromers in simulation, though they are less stable and more quickly dissociate into dimers and trimers. There can be several reasons for deviations from the simplified model — (a) at short distances, our theoretical model is no longer expected to hold. Indeed, experimentally, we observe deviations even for a pair of opposite rotors as they approach distances of ≈ 3a from one center to another (Supplementary Fig. 9). (b) Since the Reynolds number is not negligible, there may be deviations from simple pair interactions such that superposition does not strictly apply. (c) The three-dimensional nature of the flow at close proximity may play a role. (d) Other interactions, though weaker, come into play, such as attraction due to capillary forces (Supplementary Fig. 8). In the future, full, 3D simulations of the flow around adjacent rotors may assist in better understanding the stability of gyromers.

Figure 4C shows a phase-space of the formed structures in the simulations. A phase’s type is determined by the most prevalent structure (Supplementary Discussion). At small β ~ 0.1 the Stokes regime dominates and gyromers do not form at all tested area fractions [ϕ ∈ (0.02, 0.2)]. At slightly higher values, β ~ 0.3, we start to observe dimers as the most stable configuration. Going to β ~ 1, we observe gyromers up to ϕ = 20%. At higher values of β ~ 10 − 30, and for low and intermediate concentrations, there are mixed states of gyromers, lattices, and occasional rings. The steady state configurations are sensitive to initial conditions and to the total number of rotors. At β = 100, up to ϕ = 15% there is a re-entrant to a stable gyromer phase. In these high values of inertial interactions, dipolar-like interactions dominate, and gyromers are more stable to perturbations. At higher concentrations, stable structures are predominantly lattices. Experimental values are plotted on the phase-space as ‘x’s, where a broader stability regime for the gyromers can be observed.

Snapshots from the experiments for the two viscosities (β = 0.3, and β = 5) are presented in Fig. 4D. Comparable snapshots from simulations are presented below in Fig. 4E. For the higher viscosity bath, we present the dimensionless radius of gyration Rg (more on Rg in the Supplementary Discussion). In Fig. 4F, G, we show that the theoretical flow lines for β ~ 100 resemble magnetic interactions, and for β ~ 0.8, flow lines resemble a torque dipole but with a component that breaks left-right and top-bottom symmetry.

We have experimentally tested many initial configurations—random, ring, lattice, line—and all resulted in gyromer formation (see Fig. 5A). Once formed, isolated gyromers were stable. In Fig. 5B, we show the stability of a 7-gyromer by plotting the maximal formation as a function of time in both the high viscosity bath (β = 0.3), the low viscosity bath (β = 5), and in simulations (with β = 10). The dynamics are more rapid in the low viscosity bath and in the simulation. In all cases, once the gyromer forms, it stays stable. A key ingredient to the stability of the gyromers is the spin of individual rotors. Gyromers are stable for up to a couple of hours when no free monomers are present. A question arises: what makes the gyromer break after such a long time of stability? (Supplementary Movie 8). From the analysis of the rotor’s spin, it can be seen that there are always deviations in frequencies of up to 10% (see Fig. 5C). In fact, in simulations, we see that adding noise to the spins increases gyromer stability (Supplementary Fig. 7). However, once the difference is greater than around 20%, gyromers dissociate. In experiments, this happens when one of the batteries starts to fail. A typical instance of gyromer breakage is shown in Fig. 5C along with the failure of one of the rotors, marked in green.

a All tested initial conditions resulted in the formation of a gyromer. b The number of rotors in the longest gyromer, lmax, divided by the total number of rotors, N, as a function of time normalized by average spin. Results are presented for N = 7, with additional results for a 5-gyromer (β = 0.3) and a 14-gyromer (β = 5). c The moment of breakage of a 9-gyromer. The gyromer broke into a dimer and a 7-gyromer. Analysis of the spin of the rotors shows that when the spin is decreased by more than twenty percent, the gyromer starts to disintegrate. Snapshots at three points in time are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In this work, we have revealed the novel dynamic self-assembly of mixed-sign rotors, demonstrating that due to the combination of viscous and inertial forces, oppositely spinning elements attract and propagate to form active structures termed gyromers. Unlike homogeneous rotor systems that lead to the formation of hexagonal lattices, our mixed-sign rotors orchestrate themselves into linear assemblies driven purely by hydrodynamic and steric interactions. When two counter-rotors form a dimer, this dimer acts as a dipole moment. Since the interactions are dipolar, just like in magnets, the formed structures also resemble magnetic formations such as chaining53. However, our system is active, and has in addition to the radial, dipolar-like, interactions, also tangential interactions, which change the nature of the resulting dynamical states. That is, unlike magnetic particles, after gyromers are formed, they are not static. In the high viscosity bath, we observe strictly straight, linear chains; in the lower viscosity bath, gyromers can be branched, and are more curved and fluctuating. Simulations indicate that when increasing inertial forces further, gyromers fold into tertiary structures of square lattices and rings, which remain stable. At the microscale, inertia becomes negligible, but similar radial interactions may arise from viscoelastic forces. In such cases, however, additional effects, such as memory, may play a role.

These findings not only enhance our understanding of active matter systems but also lay a foundational step towards engineering advanced materials and devices harnessing the self-organizing principles observed in natural and synthetic active systems, presenting opportunities for future explorations of the complex interplays of force, motion, and structure.

Methods

Experimental setup

Each rotor consists of a brushless motor (80 rpm) powered by a LIR2477 battery and enclosed in a 3D-printed cylindrical shell (radius a = 1.8 cm and height 7.5 cm). The shell design was created in “Tinkercad" with a circular profile and a square base compatible with the motor attachment. The model was printed using a 3D printer (Bumba lab-1-Carbon). A stand to securely hold the battery in place was printed separately. The printed models can be seen in Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Information. Thin 3D-printed belts were added to reduce friction between rotors and with the bounding walls. A 3D-printed propeller attached to the bottom pin of the motor ensured counter-rotation of the rotor and propeller, and both were immersed in oil to ensure similar resistance. All rotors were carefully balanced with Plasticine to prevent precession. The experiments were performed in a cylindrical silicone-oil bath (diameter 60 cm, height 9.5 cm, density ρ = 103 kg/m3) of two viscosities: μ = 1 Pa⋅s and μ = 0.06 Pa⋅s. Each rotor was marked with a green off-centered dot in order to track its spin. The experiment was continuously monitored from above using a Sony camera (α7s_3, lens FE 4/24-105 G-OSS), capturing snapshots at one-second intervals. Rotors trajectories and spins were extracted in Python with OpenCV. Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) of the flow field was performed using Thorlabs-HNL050L laser and PIVlab software

Numerical simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were written in Python using a fifth-order Runge-Kutta scheme (free-space) or a second-order scheme (periodic boundary conditions). We have tested values of the inertial-viscous ratio β ranging from 0.01 to 1000. Gaussian noise (typically 10%) was added in some runs. The timestep was dt = 10−5. Soft-core steric interactions between particles were included in the form of purely repulsive harmonic springs with strength ws = 5⋅104. Interactions vanish beyond rij > 2a, and for rij < 1.8a the radial hydrodynamic term was set to zero to avoid unphysical overlap. This stabilization allowed larger timesteps without changing the dynamics.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files and movies. Source data are provided with this paper. All further processed data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code used for the simulations is available on Code Ocean DOI 10.24433/CO.1616623.v1.

References

Schrodinger, E. What is Life? With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Alberts, B. et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell: Seventh International Student Edition with Registration Card (WW Norton & Company, 2022).

Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 8th ed. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2021).

Doi, M. & Edwards, S. F. The Theory of Polymer Dynamics, vol. 73 (Oxford University Press, 1988).

Theurkauff, I., Cottin-Bizonne, C., Palacci, J., Ybert, C. & Bocquet, L. Dynamic clustering in active colloidal suspensions with chemical signaling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 268303 (2012).

Palacci, J., Sacanna, S., Steinberg, A. P., Pine, D. J. & Chaikin, P. M. Living crystals of light-activated colloidal surfers. Science 339, 936 (2013).

Briand, G. & Dauchot, O. Crystallization of self-propelled hard discs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 098004 (2016).

Mognetti, B. M. et al. Living clusters and crystals from low-density suspensions of active colloids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 245702 (2013).

Jennings, B. & Stankiewicz, M. Electro-optic observations of electrodynamic band formation in colloidal suspensions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 427, 321 (1990).

Linear chains and chain-like fractals from electrostatic heteroaggregation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 260, 149 (2003).

Yan, J. et al. Reconfiguring active particles by electrostatic imbalance. Nat. Mater. 15, 1095 (2016).

Junot, G., De Corato, M. & Tierno, P. Large scale zigzag pattern emerging from circulating active shakers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 068301 (2023).

Shoham, Y. & Oppenheimer, N. Hamiltonian dynamics and structural states of two-dimensional active particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 178301 (2023).

Mendelev, V. S. & Ivanov, A. O. Ferrofluid aggregation in chains under the influence of a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. E 70, 051502 (2004).

McMullen, A., Muñoz Basagoiti, M., Zeravcic, Z. & Brujic, J. Self-assembly of emulsion droplets through programmable folding. Nature 610, 502 (2022).

Grzybowski, B. A., Stone, H. A. & Whitesides, G. M. Dynamic self-assembly of magnetized, millimetre-sized objects rotating at a liquid–air interface. Nature 405, 1033 (2000).

Yan, J., Bae, S. C. & Granick, S. Rotating crystals of magnetic janus colloids. Soft Matter 11, 147 (2015).

Soni, V. et al. The odd free surface flows of a colloidal chiral fluid. Nat. Phys. 15, 1188 (2019).

Massana-Cid, H., Levis, D., Hernández, R. J. H., Pagonabarraga, I. & Tierno, P. Arrested phase separation in chiral fluids of colloidal spinners. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, L042021 (2021).

Chen, P. et al. Self-propulsion, flocking and chiral active phases from particles spinning at intermediate reynolds numbers. Nat. Phys. 21, 146 (2025).

Modin, A., Ben Zion, M. Y. & Chaikin, P. M. Hydrodynamic spin-orbit coupling in asynchronous optically driven micro-rotors. Nat. Commun. 14, 4114 (2023).

Drescher, K. et al. Dancing volvox: hydrodynamic bound states of swimming algae. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 168101 (2009).

Tan, T. H. et al. Odd dynamics of living chiral crystals. Nature 607, 287 (2022).

Avron, J. Odd viscosity. J. Stat. Phys. 92, 543 (1998).

Banerjee, D., Souslov, A., Abanov, A. G. & Vitelli, V. Odd viscosity in chiral active fluids. Nat. Commun. 8, 1573 (2017).

Bililign, E. S. et al. Motile dislocations knead odd crystals into whorls. Nat. Phys. 18, 212 (2022).

Nguyen, N. H., Klotsa, D., Engel, M. & Glotzer, S. C. Emergent collective phenomena in a mixture of hard shapes through active rotation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 075701 (2014).

Nash, L. M. et al. Topological mechanics of gyroscopic metamaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 14495 (2015).

Bricard, A., Caussin, J.-B., Desreumaux, N., Dauchot, O. & Bartolo, D. Emergence of macroscopic directed motion in populations of motile colloids. Nature 503, 95 (2013).

Driscoll, M. et al. Unstable fronts and motile structures formed by microrollers. Nat. Phys. 13, 375 (2017).

Stockdale, O. R. et al. Universal dynamics in the expansion of vortex clusters in a dissipative two-dimensional superfluid. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033138 (2020).

Helmholtz, H. V. On integrals of the hydrodynamical equations, which express vortex-motion. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 33, 485 (1867).

Thomson, W. On vortex motion. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 25, 217 (1868).

Onsager, L. Statistical hydrodynamics. Il Nuovo Cim. 6, 279 (1949).

Yeo, K., Lushi, E. & Vlahovska, P. M. Collective dynamics in a binary mixture of hydrodynamically coupled microrotors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 188301 (2015).

Lushi, E. & Vlahovska, P. M. Periodic and chaotic orbits of plane-confined micro-rotors in creeping flows. J. Nonlinear Sci. 25, 1111 (2015).

Fily, Y., Baskaran, A. & Marchetti, M. C. Cooperative self-propulsion of active and passive rotors. Soft Matter 8, 3002 (2012).

Aubret, A., Youssef, M., Sacanna, S. & Palacci, J. Targeted assembly and synchronization of self-spinning microgears. Nat. Phys. 14, 1114 (2018).

Lenz, P., Joanny, J.-F., Jülicher, F. & Prost, J. Membranes with rotating motors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 108104 (2003).

Oppenheimer, N., Stein, D. B. & Shelley, M. J. Rotating membrane inclusions crystallize through hydrodynamic and steric interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 148101 (2019).

Shen, Z. & Lintuvuori, J. S. Collective flows drive cavitation in spinner monolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 188202 (2023).

Grzybowski, B. A., Jiang, X., Stone, H. A. & Whitesides, G. M. Dynamic, self-assembled aggregates of magnetized, millimeter-sized objects rotating at the liquid-air interface: macroscopic, two-dimensional classical artificial atoms and molecules. Phys. Rev. E 64, 011603 (2001).

Goto, Y. & Tanaka, H. Purely hydrodynamic ordering of rotating disks at a finite reynolds number. Nat. Commun. 6, 5994 (2015).

Scholz, C., Engel, M. & Pöschel, T. Rotating robots move collectively and self-organize. Nat. Commun. 9, 931 (2018).

Deseigne, J., Dauchot, O. & Chate, H. Collective motion of vibrated polar disks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 098001 (2010).

Blake, J. & Chwang, A. Fundamental singularities of viscous flow: part i: the image systems in the vicinity of a stationary no-slip boundary. J. Eng. Math. 8, 23 (1974).

Arbel, E. et al. A mechanical route for cooperative transport in autonomous robotic swarms. Nat. Commun. 16, 7519 (2025).

Casiulis, M. et al. A geometric condition for robot-swarm cohesion and cluster–flock transition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 122, e2502211122 (2025).

Kim, S. & Karrila, S.J. Microhydrodynamics: Principles and Selected Applications (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2013).

Schonberg, J. A. & Hinch, E. Inertial migration of a sphere in poiseuille flow. J. Fluid Mech. 203, 517 (1989).

Atkins, P. W., De Paula, J. & Keeler, J. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Jackson, J. D. Classical Electrodynamics (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

Skjeltorp, A. T. One-and two-dimensional crystallization of magnetic holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 51, 2306 (1983).

Acknowledgements

We thank Matan Yah Ben Zion and Yoav Lahini for their helpful suggestions and discussions. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 1752/20). This research was also supported by an NSF-BSF grant No. 2023624.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.O. initiated and supervised the project. A.C. designed and built the first rotors and performed the proof-of-concept experiments. M.G., J.K., and N.I. carried out the subsequent experiments that form the core of this manuscript. M.G. developed the code for experimental analysis. M.G., J.K., and Y.L. analyzed the data. Y.L. and N.O. developed the simulation code. M.G. and N.O. worked on the two-rotor theory. N.O., and M.G. wrote the manuscript with the help of J.K. and Y.L. All authors discussed the results and provided feedback on the manuscript. A.C., J.K., and Y.L. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Antoine Aubret, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gelvan, M., Chirko, A., Kirpitch, J. et al. Hydrodynamic spin-pairing and active polymerization of oppositely spinning rotors. Nat Commun 16, 10368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65322-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65322-w