Abstract

Modulation and amplification are two fundamental processes in optoelectronics. While discrete implementations have achieved widespread success, the challenge of monolithically integrating sufficient gain and electro-optic bandwidth remains a significant barrier, limiting optical systems’ miniaturization and scalability. We unify these two functions in the Er-doped thin-film lithium niobate (Er:TFLN) platform, achieving a record-high internal net gain of 38 dB in a 9.16-cm-long waveguide amplifier. Meanwhile, leveraging the host material’s strong Pockels effect, we realize ultra wide-range electro-optic modulation with a bandwidth of 53 GHz and operation up to 170 GHz, fabricated alongside waveguide amplifiers using a zero-change process. Additionally, we validate this functional fusion through two signal processing scenarios: self-amplified digital signal encoding and pre-amplified broadband radio frequency front-end receiving, demonstrating improved signal recovery quality compared to off-chip gain. The modulation-amplification integration holds broad potential for increasing system complexity and network depth in applications such as optical interconnections, Lidar, and microwave photonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photonic integrated circuits hold immense potential for advancing modern infrastructure, from telecommunications to high-performance computing1. The integration of multiple functions on a single chip enables far greater system complexity and density compared to conventional bulk optics, as demonstrated in parallel optical interconnections2,3,4,5,6, optical phased arrays7,8,9, and optical computing engines10,11,12. However, large-scale optical system integration has primarily focused on the high-volume deployment of passive devices (e.g. optical I/O8, filters12,13,14, and interferometers11), while incorporating only a limited number of lossy active electro-optic (EO) devices to preserve a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio. Additionally, these systems are typically configured in parallel to prevent loss-induced level-by-level degradation10. These constraints limit on-chip data throughput and challenge the realization of high-depth on-chip networks for powerful and versatile system operation.

To mitigate link loss and address the bandwidth demands of on-chip optical systems, the monolithic integration of two fundamental functions-high optical gain and high-speed modulation-is essential on a photonic chip. Generally, to maximize the performance of different functions, appropriate material systems are selected individually based on their inherent characteristics15. For instance, III-V semiconductor optical amplifiers (SOAs)16,17,18,19 or rare-earth-doped waveguides with various host materials20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 are used to generate optical gain, while materials with a strong Pockels effect28 or free-carrier dispersion29 are preferred for EO conversion. The combination of these two functions, however, continues to pose significant challenges in terms of both material properties and process complexity. Although Er-doped waveguide amplifiers with an internal net gain exceeding 30 dB, comparable to commercial standards, have been demonstrated on the SiN platform24 and Al2O3 platform26, the passive nature of these platforms impedes further monolithic manipulation of EO conversion. Combining amplification and modulation functions has been previously achieved on the III-V-silicon hybrid platform30, but additional fabrication processes, such as epitaxial regrowth, are required to integrate III-V functional layers with varying bandgaps, increasing both fabrication complexity and manufacturing difficulty. Furthermore, these systems still face challenges, including relatively high waveguide loss, inherent amplification noise, and signal distortion caused by nonlinear gain process in III-V material and nonlinear EO conversion in silicon-based systems17,18,19,31, which limits performance, especially in applications that demand high fidelity and low crosstalk.

In order to embed the amplification function into high-speed opto-electrical circuitry, Erbium-doped lithium niobate is a promising alternative. Compared to previous host materials (such as SiN, Al2O3) lacking fundamental properties and functions (such as Pockels effect for EO modulation or second-order optical nonlinearity), lithium niobate distinguishes itself through its diverse optical properties, including high refractive index contrast and pronounced EO effect32. Early explorations of combining optical gain and electro-optic effects in lithium niobate were reported in bulk platforms33. Recent breakthroughs in thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) technology further enables stronger optical confinement and higher EO bandwidth compared to its bulk counterpart33. First developed in 2021, the Erbium-doped lithium niobate (Er:TFLN) waveguide amplifier already shows its potential for small signal enhancement34,35. However, the internal net gain and saturated output optical power have not yet simultaneously reached the ideal performance level36,37,38. More importantly, the study of EO dynamics in Er:TFLN still remains elusive, despite its host material, TFLN having achieved significant success in both high-frequency functionality and system implementations28,39.

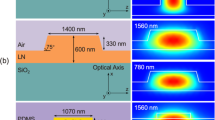

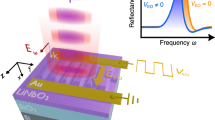

In this work, we unify the ultra-high optical gain and sufficient electro-optical modulation capability on an Er:TFLN platform for the first time (Fig. 1). By employing a multimode waveguide design, the fabrication-induced background loss is reduced to 0.4 dB/cm. Leveraging the low background loss and optimized doping density, we achieve a significant improvement of the internal net gain as high as 38 dB in a compact 9.16-cm-long amplifier. The proposed amplifier also presents an on-chip saturated output power of over 14 dBm and a low noise figure of 4.7 dB. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest internal net gain reported for integrated amplifiers, with critical parameters matching the performance of commercial erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs). Meanwhile, we integrate a high-speed electro-optic modulator with the Er-doped amplifier for the first time, using a zero-change process that preserves the waveguide amplifier fabrication, achieving efficient electro-optical dynamics with a bandwidth of 53 GHz while maintaining high optical gain. Moreover, by using this monolithically integrated modulation-amplification function, both on-chip digital and analog signal processing are performed losslessly. The self-amplified Er:TFLN modulator performs a 50 Gbps signal transmission and a pre-amplified chip-based radio frequency (RF) front-end receives a frequency-chirped signal from 8 to 12 GHz. With the on-chip amplification scheme, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) degradation of the recovered signal is mitigated, resulting in an improvement compared to using an EDFA. Through modulation-amplification integration, our work unlocks promising prospects for integrated photonics, with the potential to enable more advanced functional modules, such as tunable and mode-locked lasers, while also facilitating deeper on-chip photonic networks due to enhanced signal integrity.

Results

Multifunctional co-design and basic performance

To unify optical amplification and electro-optical modulation, a carefully designed structure is developed to achieve a balanced performance for both functionalities in Er:TFLN. For optical amplification, the underlying process involves light-matter interactions, namely the stimulated absorption of pump light and the stimulated emission for signal light in Er3+ ions40. The Er3+ ion is doped during the crystal growing process (See Supplementary Note 2). The doping concentration is set to 0.5 mol %. Figure 2a depicts the photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of the Er:TFLN, exhibiting amplified photon emission via stimulated emission from Er3+ ions across 1520 to 1570 nm and a notable peak emerges around 1531.7 nm, with two minor peaks observed at 1543 nm and 1550 nm. The photoluminescence lifetime is measured to be 5.8 ms (See Supplementary Note 5), which indicates an ideal doping condition, comparable to the typical value in the commercial EDFA (@ 10 ms41).

a Photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of the Er:TFLN waveguide amplifier; b Measured total loss of amplifiers of different lengths under an input signal power of 30 μW; c Simulated optical and electrical loss with different oxide layer thicknesses; d Simulated VπL with different oxide layer thicknesses and electrode gaps; e Spectrum when a sine wave signal with an amplitude of 3.5 V is applied to the modulator.

For efficient amplifiers in the integrated Er:TFLN platform, the background loss, especially the scattering loss, emerges as the primary limiting factor compared with their fiber-based competitor. Integrated waveguides typically exhibit orders of magnitude higher propagation loss compared with fibers, leading to higher loss of pump light and decreased net gain of signal light. To suppress the scattering loss, we implement a 3-μm width × 600-nm height multimode waveguide to decrease the interaction between the optical field and the etched sidewalls. Meanwhile, the multimode waveguides with larger mode area could provide higher gain and saturation power42. Another loss factor is from the bending region, limiting the minimum bending radius and the compactness. Different from the ridge waveguide in previous work, with relatively large bending radii of about several hundreds of μm to ensure pure single mode propagation over long delay lines35,37, the optical amplifier is formed by strip waveguide with a fully-etching process, as shown in Fig. 1b. The strip waveguide supports a tighter light confinement for small bend radius and small waveguide gaps for compact structures. Figure 1c shows a bend region of a square spiral. The gap between adjacent waveguide is set to 7 μm with negligible coupling. The minimal bend radius is set to 170 μm. The adiabatic bend design is adopted here43 for quasi-single-mode transmission with compact size. For more details about amplifiers design, see Supplementary Note 1. Figure 2b shows the measured loss of amplifiers with different lengths with the off-chip input signal power of 30 μW. The background loss coefficient is estimated as 0.4 dB/cm by linearly fitting the total losses of different waveguide lengths at 1600 nm, where the absorption of Er3+ ions is ignorable (See Supplementary Note 3). The coupling loss is estimated as the average of intercepts at different wavelengths, which is ~6.7 dB/facet.

Based on the developed amplifier, the electro-optical modulation functionality is integrated using a traveling wave electrode patterned on a 900-nm-thick gold (Au) layer. Instead of the conventional design with the electrode coplanar to the waveguide, we position the electrode above the the waveguide by depositing a oxide layer, as shown in Fig. 1d. This design reduces optical propagation losses by minimizing the interaction between the light field and the electrode44. Simultaneously, microwave losses are reduced by distancing the microwave field from the Silicon substrate with high index. Figure 2c illustrates the relationship between the simulated optical and microwave propagation losses as a function of the thickness of the oxide layer between the electrode and the waveguide. It shows that as the thickness of the oxide layer between the substrate and the electrode is ⩾1 μm, both optical loss and microwave loss are maintained at low levels. Figure 2d presents the simulated VπL of single-drive modulation under different oxide layer thicknesses and electrode gaps45. As the electrode spacing increases, the interaction between the applied electrical field and the optical field decreases. To ensure low levels of optical and microwave losses while achieving high modulation efficiency, the electrode gap and oxide layer thickness are set to 3.5 μm and 1 μm, respectively. Figure 1e shows a photo of a phase modulator with 8-mm-long electrode. The carrier-to-first sideband (FSB) intensity equalization technique31 is used to determine the half-wave voltage. As depicted in Fig. 2e, when the peak-to-peak voltage Vm of the applied radio frequency field reaches 8 V, the modulated spectrum exhibits equal intensities between the carrier and the first sidebands. The modulation efficiency can be then estimated as LVm/0.457, yielding 3.1 V ⋅ cm for push pull modulation (See Supplementary Note 9).

High-gain optical amplification

Benefiting from the low background loss coefficient, the designed amplifier features an impressive amplification performance. In experiment, a continuous-wave laser at 1531.7 nm is used as the signal light to access the gain factor. To maximize the amplifying performance, the bidirectional pumping scheme24 is adopted here, with the experimental setup depicted in Fig. 3a. A pump laser at 1480 nm is employed, which is equally split and injected into the waveguide amplifier from both facets. To accurately extract the gain performance, the powers of output and input signal are directly measured and compared in the spectra recorded by an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA), where the pump power interference can be eliminated due to the inherent wavelength selectivity of the OSA. The internal net gain is thereby obtained from the fiber-to-fiber power difference, meanwhile considering the coupling loss and the insertion loss from the fiber-based measurement link (e.g., the wavelength division multiplexer).

a Left panel, experimental setup. WDM wavelength division multiplexer, PC Polarization controller, Att. Attenuator, OSA Optical spectrometer analyzer, PM power meter. Right panel, optical image of an Er:TFLN chip under optical pumping of 115 mW, butt-coupled with fibers. The green light emission results from the second-order cooperative upconversion process upon intense optical pumping. b Optical spectra of output signals from the pumped amplifier, when the off-chip input signal power is −39.6 dBm. c Measured internal net gain (blue dots) at 1531.7 nm with different pump power upon 1480 nm pumping; d Measured internal net gain with different wavelength (fit by cubic spline interpolation). e Optical spectra of the input signal and the amplified signal under a high off-chip input signal power of −1 dBm.

To evaluate the amplification, the internal net gain with the varying pump power under a small input signal (off-chip −39.6 dBm) is measured, as shown in Fig. 3b. The gain factor increases much slower with the pump power, as the pump power >80 mW compared with that in the low pump power region (0~20 mW). Significantly, the highest on-chip net gain under 115 mW off-chip pump power is around 38 dB at 1531.7 nm (with the consideration of 2.9 dB fiber link loss and 6.7 dB/facet coupling loss, as shown in Fig. 3b) in the 9.16 cm waveguide amplifier, corresponding to an average gain of 4.1 dB/cm. The gain spectrum is depicted in Fig. 3d by estimating gain factors at different signal wavelengths. For most of the band from 1530 nm to 1565 nm, the gain factor is above 20 dB. The achieved gain factor not only rivals that of commercial EDFAs but also represents the highest internal net gain reported to date for waveguide-based amplifiers (See Supplementary Note 8). Higher pump power of larger than 115 mW could further increase the gain before saturation, while the measurement of such performance is presently affected by the parasitic lasing24, resulting from the internal reflection between the chip facets (See Supplementary Note 7).

The saturation output power is another essential property for practical systems-level deployments, representing the maximum output capacity of the amplifier. For the waveguide amplifier, the gain factor should decrease as the increasing input signal power due to the gain saturation, under a fixed pump power. The on-chip saturation output power of the waveguide amplifier is defined as the on-chip signal power at which the internal net gain is equal to zero. Figure 3e illustrates the off-chip amplified signal on the OSA with a peak power of 5.9 dBm, as the off-chip input signal power is −1.0 dBm, where an ultra-high signal enhancement of 69.6 dB is evidenced. Considering the coupling loss and the off-chip link loss, the internal net gain is still over 23 dB. This result implies that the on-chip saturation output power greatly exceeds 14 dBm. Figure 3e is also utilized for extracting the noise figure, an essential factor for assessing signal-noise ratio degradation, based on the optical source subtraction method (See Methods)41. The noise figure is measured to be 4.7 dB, closed to that of a commercial EDFA.

Broadband electro-optic conversion

With the designed modulation region on the high-gain optical amplifier, we present, to the best of our knowledge, the first demonstration of broadband modulation characteristics on Er:TFLN through pump on/off experiments to validate high-fidelity signal integrity. Figure 4a shows a photo of an intensity modulator based on the Mach–Zehnder interferometer with the electrode length of 8 mm. The signal light is injected from the left side, while the pump light is injected from both sides, as done during the gain characterization process. The RF field is applied on the electrodes from the same side as the signal (See Supplementary Note 11). As the signal light passes through the modulation region, it is modulated and amplified simultaneously. Figure 4c displays the measured EO responses with and without the pump light, where the 3-dB bandwidth is measured as 53 GHz (with pump). Notably, the amplification provides a 6 dB enhancement of the modulated signal without degrading the modulation process. To further prove the unity of amplification and modulation, a digital signal transmission experiment is performed using a high-speed on-off keying (OOK) signal of 50 Gbps applied to the signal light. Figure 4d, e show the detected signal with and without the pump light. With amplification, the higher EO response results in a clearer eye diagram due to partial loss compensation of the measurement link, improving subsequent digital signal extraction and processing.

a False-color picture of a intensity modulator on Er:TFLN. b False-color picture of a phase modulator on Er:TFLN. c Electro-optic response of a intensity modulator with and without pump light. d, e Eye diagrams with and without pump light. OOK, on-off keying. f Modulation performance setup of phase modulator. g–j Spectrum of sideband modulation with pump light and without pump light via off-chip measurement. fmod, modulation frequency.

The above EO response enhancement is limited by the device length of 8 mm. To boost the enhancement with the high-gain amplifier, an amplifier of a 6-cm-long spiral is added after the modulation region, as depicted in Fig. 4b. Two electrodes are positioned on both sides of the straight waveguide to form a phase modulator. Unlike the intensity modulator, it is difficult to directly measure the EO response profile for a phase modulator. Instead, the optical spectra with and without the pump light are given in Fig. 4g–j, as the applied RF signal tuned from 20 GHz to 170 GHz. With the extended optical amplifier, the optical signal enhancement is ~30 dB. As the modulation frequency increases, the power difference between the modulated sideband and the optical carrier decreases from −20 dB to −38 dB due to the reduced EO response at high frequencies. Detailed EO response measurements of the phase modulator from 10 GHz to 170 GHz are provided in Supplementary Note 11.

Analog radio frequency (RF) receiving with pre-amplification

To verify the capability of Er:TFLN in real-world applications, the developed chip with both amplification and modulation is used for analog RF receiving system. The schematic is shown in Fig. 5a and detailed experimental setups are given in Supplementary Note 12. A frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW), chirped between 8 GHz and 12 GHz at a repetition rate of 800 kHz, is applied to the phase modulator, acting as an RF signal to be received. The FMCW signal is loaded on the optical carrier and amplified through the developed modulator and amplifier. After the Er:TFLN chip, a band pass filter (BPF) is employed to suppress the lower sideband, converting the phase-modulated signal to an intensity-modulated signal. The filtered optical signal is detected by a photodetector, converting it back into an RF signal. The detected RF signal is recorded in the frequency domain (depicted in Fig. 5b–d) with an electric signal analyzer and in the time domain with an oscilloscope. Using the short-time Fourier transform, the spectra are recorded, revealing the instantaneous frequency chirping over time, as shown in Fig. 5e–g.

a Setup of a frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW) signal modulation and amplification chirped between 8 GHz and 12 GHz at a repetition rate of 800 kHz. BPF, band pass filter. b–g The received microwave signal and time-frequency spectra of the beatnote between the carrier and the sideband when the signal light is b, e at 1600 nm without pump light, c, f at 1550 nm with pump light and d, g at 1550 nm by using a TFLN-based modulator and an EDFA.

When the input signal light is at 1600 nm without the pump light, the on-chip loss decreases the optical power to −15.0 dBm, resulting in a detected SNR of less than 9 dB, as depicted in Fig. 5b. The low SNR prevents the extraction of the instantaneous frequency. With the pump light, the output signal at 1550 nm is boosted to −4.2 dBm, resulting in a SNR of 30 dB. A clear FMCW signal can be recovered, as shown in Fig. 5f. For comparison, an undoped TFLN phase modulator is adopted to receive the same RF signal and then amplified by a commercial EDFA. The RF power, input optical power and amplified power level are set the same as the previous setup. The recovered RF signal in this configuration shows an SNR of 22 dB. Interestingly, the proposed approach can recover the signal with an increase in SNR than utilizing conventional fiber optics. This can be attributed to the position of the amplifier in the system, besides the difference in insertion loss. When using the on-chip amplifier with the pump light, the signal is modulated and amplified simultaneously, allowing the signal to maintain a high power level with low amplifier noise. In contrast, the EDFA amplification occurs after significant insertion loss from the undoped TFLN chip, which degrades the modulated signal and makes it drown into background noise. Although the EDFA can boost the weakened optical signal, the low input power results in a higher level of amplified spontaneous emission noise.

Discussion

In summary, we unified high optical amplification and large bandwidth modulation into a single, compact platform. Using a tailored multimode waveguide structure, we achieved a maximum internal net gain of 38 dB at 1531.7 nm in a 9.16-cm-long Er:TFLN waveguide amplifier with over 14 dBm saturation power and a noise figure of 4.7 dB. The proposed amplifier exhibits the highest internal net gain among all waveguide amplifer and is comparable to the commercialized EDFA (see Supplementary note 8). The high-gain characteristic can be integrated with electro-optic dynamics up to 170 GHz with minimal changes to the fabrication process. Both analog and digital signals have been modulated with self-amplification on chip, demonstrating the large bandwidth and low-loss EO conversion. Compared with other approaches, the proposed Er:TFLN platform holds sufficient internal net gain while providing ultra-wide electro-optic dynamics, all within a compact size and with fabrication simplicity, which paves the way for future advanced integrated photonic systems.

Additionally, the performance could be promoted with further optimization. In terms of optical amplification, the achieved gain and output optical power of our work are limited by the parasitic laser. Introducing an anti-reflective coating scheme or utilizing angled edge coupler46 would help eliminate such parasitic lasing. Also, the unoptimized coupling loss can be reduced down to lower than 1 dB/facet by suspended waveguide47 or cladding waveguide48 design, thereby bringing another 10 dB for off-chip net gain. Further, designing waveguides with larger mode areas elevates the saturated optical power. This enhancement stems from reduced optical intensity density within the waveguide cross-section, which mitigates gain saturation by distributing power over a broader effective area42. To improve pump efficiency, sensitizers such as Yb3+ can be introduced to enhance the stimulated absorption of the pump light and the stimulated emission efficiency of the signal light37,49,50. In terms of gain bandwidth, ultra-wide-spectrum amplifiers spanning multiple bands can be achieved by doping multiple rare earth ions simultaneously such as Neodymium (Nd @ 910 nm and 1300 nm band), Thulium (Tm @ 2000 nm band51), and so on52. In the context of modulation, slow-wave electrodes offer a significant enhancement in modulation bandwidth by improving speed matching and minimizing microwave losses53. This enables higher data transmission rates and supports a broader range of modulation formats, further optimizing system performance. The current modulation efficiency is limited (See Supplementary Note 9), but it can be improved by shrinking the waveguide-to-electrode distance or using slow-light waveguide54, which can enhance the light-matter interaction by introducing a resonant structure, leading to higher modulation efficiency and more compact footprint.

Stepping forward, we believe a fully functional integrated photonic circuit could be achieved by heterogeneous integration with other functions such as photodetector55 and pump laser19. Nonetheless, the realizing of monolithic modulation-amplification itself opens novel opportunities for compactly developing complex integrated photonic devices including mode-locked laser56 and Q-switched laser57, which previously relied on the additional growth of different function layers or hybrid integration between gain and process chips. Moreover, when combined with other nonlinear and low-loss passive functions, the Er:TFLN platform can provide sufficient power relay and electro-optical operation to significantly expand its application fields, enabling more powerful frequency comb generation58 and parametric oscillaton59, meanwhile attaining larger-scale photonic network in optical processing39, and beam manipulation7.

Methods

Fabrication process

The Er:LN is formed with the erbium oxide doping during the growth of the LN crystal, ensuring uniform Er3+ ion distribution60. A 3-inch Er:LN wafer is exfoliated and transformed onto the silicon dioxide substrate, resulting in the Er:TFLN. Then, the wafer is patterned using electron beam lithography (EBL) and etched via inductively coupled plasma-reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE)61,62 or EBL. A SiO2 layer is deposited as protection. Without changing the aforementioned fabrication process, a 900-nm-thick Au layer is deposited on the SiO2 surface by electron beam evaporation (EBE). Finally, the electrodes are formed using the lift-off method.

Loss rate calculation

The loss rate is measured by the intercept method. Without the pump light, the optical powers are measured at two points: before the input of the waveguide amplifier and after the output. The difference between these two power measurements is referred to as the total loss(IL), which includes coupling loss (Lc), waveguide background loss (Lb), and waveguide absorption loss (La). The relation between the absorption loss and the length of the amplifier can be expressed as:

where λ is the wavelength of the signal light and α denotes the absorption loss rate which is the function of λ. Similarly, considering the scattering loss as the primary contribution to the Lb, the relation between Lb and l can be expressed as:

where s indicates the scattering loss rate. Thus, IL can be expressed as:

Photoluminescence spectrum measurement

The photoluminescence (PL) spectrum was acquired using a fluorescence spectrometer (MicroSpecIR) equipped with a long-pass optical filter (Thorlabs FELH1500; cut-on wavelength: 1500 nm). The sample was pumped by a 1480 nm laser source (PSU-III-LED1480). The added optical filter suppressed residual pump scattering at 1480 nm, ensuring signal fidelity below 1500 nm.

Internal net gain calculation

The internal net gain refers specifically to the on-chip optical power amplification within the Er:TFLN waveguide itself, calculated by accounting for all passive losses except input/output coupling. This value represents the pure amplification within the waveguide, excluding coupling losses and link loss. It is defined as:

where \({P}_{\!\!{\mbox{out}}\,}^{(off-chip)}\) is the optical power measured after the chip (e.g., −17.6 dBm at 1531.6 nm in Fig. 3b), \({P}_{\!\!{\mbox{in}}\,}^{(off-chip)}\) is the input power launched into the chip (e.g., −39.6 dBm in Fig. 3b), Lcoupling is the total input/output fiber-chip coupling loss with a value of 13.4 dB, Llink is the insertion loss of the fiber links and devices (mainly induced by the wavelength division multiplexers) amounting to 2.9 dB.

Amplification measurement

In experiment of internal net gain and saturation output power test, a continuous-wave laser (EXFO T100S-HP) at 1531.7 nm is used as the signal light to access the gain factor. To maximize the amplifying performance, we use the bidirectional pumping scheme. A 1480 pump laser (PSU-III-LED1480) is equally split and injected into the waveguide amplifier from both facets. Meanwhile, the polarization and the power of the signal light is controlled through a polarization controller (Thorlabs FPC560) and an optical attenuator (Thorlabs V1550A). To accurately extract the gain performance, the powers of output and input signal are directly measured and compared in the spectra recorded by OSA (YOKOGAWA AQ6370C), where the pump power interference can be eliminated due to the inherent wavelength selectivity of the optical spectrum analyzer.

Noise figure extraction

The noise figure is measured by optical source subtraction method41, which can remove the source spontaneous emission (SSE) noise from the total noise emitted by the erbium amplifier. An optical spectrum analyzer is employed to capture the spectra of both the input signal light and the amplified signal light. The optical gain G at the optical frequency v, the noise power of the input light (PSSE), and the output power (Pout) within an optical bandwidth (B0) are determined from the obtained optical spectra. The noise figure follows the expression:

To avoid overestimating the noise figure, the OSA resolution bandwidth is set to the finest value of 0.02 nm. Because the OSA sensitivity limits the noise power extraction under low signal powers, the noise property is characterized under a high-power input signal as a representative example. From the power difference at the signal wavelength (Fig. 3e), an off-chip optical net gain is calculated as 6.9 dB. The noise powers, recorded as Pout = −53.5 dBm and PSSE = −80.1 dBm within the resolution bandwidth of the OSA, are determined from the noise floors measured at wavelengths 0.3 nm distant from the signal peak. Substituting the measured results into the Eq. (5) yields a noise figure of 4.7 dB.

Modulation measurement

For the bandwidth test, a vector network analyzer (Keysight PNA-X Network Analyzer N5247B) with its plug-in 67-GHz lightwave component analyzer (Keysight LCA Optical Receiver N4372E) is used to measure the EO S21 transmission. In the data transmission experiments, the high-speed OOK signal with a standard pseudo-random binary sequence (PRBS) pattern is generated by a bit pattern generator (SHF 12104A). The signals are amplified by a commercial driver (SHF S807C) which Vpp=2 V and then injected into the modulator, working under the push-pull configuration. At the receiving end, a 50 GHz photodiode (PD, Coherent HPDV2120R) is used to receive the optical signal. Digitized data are collected using an 80-GSa/s real-time oscilloscope with an analogue bandwidth of 62 GHz (Keysight DSA-X 96204Q). More details about the experimental setup are given in Supplementary Note 10.

For the amplification experiment with broadband modulation, the RF generator (Keysight N5222B+N5292A) loads signals ranging from 10 GHz to 110 GHz onto the modulator and the modulated spectra are recorded with a OSA (YOKOGAWA AQ6370C). For higher frequency signals (110–170 GHz), a frequency multiplier (SGFE06) is used to up-convert the signal frequency generated by KEYSIGHT E8257D before it is applied to the modulator (See Supplementary Note 11).

For the signal modulation and amplification test, the Arbitrary Waveform Generator (AWG, Micram Instruments 10002) generates a 200 mV chirped signal ranging from 8 GHz to 12 GHz. The EDFA (AEDFA-PA-35-B-FA) is used to compare with the developed EDWA. (See Supplementary Note 12).

Data availability

The data that supports the plots within this paper and other fndings of this study are available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16642642). All other data used in this study are available from thecorresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Shekhar, S. et al. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 751 (2024).

Pfeifle, J. et al. Coherent terabit communications with microresonator kerr frequency combs. Nat. Photonics 8, 375–380 (2014).

Lundberg, L. et al. Phase-coherent lightwave communications with frequency combs. Nat. Commun. 11, 201 (2020).

Jørgensen, A. et al. Petabit-per-second data transmission using a chip-scale microcomb ring resonator source. Nat. Photonics 16, 798–802 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. High-coherence parallelization in integrated photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 7892 (2024).

Shu, H. et al. Microcomb-driven silicon photonic systems. Nature 605, 457–463 (2022).

Yue, G. & Li, Y. Integrated lithium niobate optical phased array for two-dimensional beam steering. Opt. Lett. 48, 3633–3636 (2023).

Sun, J., Timurdogan, E., Yaacobi, A., Hosseini, E. S. & Watts, M. R. Large-scale nanophotonic phased array. Nature 493, 195–199 (2013).

Liu, Y. & Hu, H. Silicon optical phased array with a 180-degree field of view for 2D optical beam steering. Optica 9, 903–907 (2022).

Xu, Z. et al. Large-scale photonic chiplet Taichi empowers 160-TOPS/W artificial general intelligence. Science 384, 202–209 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 11, 441–446 (2017).

Bai, B. et al. Microcomb-based integrated photonic processing unit. Nat. Commun. 14, 66 (2023).

Zhang, W. & Yao, J. Photonic integrated field-programmable disk array signal processor. Nat. Commun. 11, 406 (2020).

Gao, W. et al. Broadband 32×32 strictly-nonblocking optical switch on a multi-layer Si3N4-on-SOI platform. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2300275 (2023).

Bogdanov, S., Shalaginov, M., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Material platforms for integrated quantum photonics. Optical Mater. Express 7, 111–132 (2016).

Van Gasse, K., Wang, R. & Roelkens, G. 27 dB gain III-V-on-silicon semiconductor optical amplifier with >17 dBm output power. Opt. Express 27, 293–302 (2019).

Davenport, M. L. et al. Heterogeneous silicon/III-V semiconductor optical amplifiers. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 22, 78–88 (2016).

Op de Beeck, C. et al. Heterogeneous III-V on silicon nitride amplifiers and lasers via microtransfer printing. Optica 7, 386–393 (2020).

Op de Beeck, C. et al. III/V-on-lithium niobate amplifiers and lasers. Optica 8, 1288–1289 (2021).

Della Valle, G. et al. Compact high gain erbium-ytterbium doped waveguide amplifier fabricated by Ag-Na ion exchange. Electron. Lett. 42, 1 (2006).

Mu, J., Dijkstra, M., Korterik, J., Offerhaus, H. & García-Blanco, S. M. High-gain waveguide amplifiers in Si3N4 technology via double-layer monolithic integration. Photonics Res. 8, 1634–1641 (2020).

Frankis, H. C. et al. Erbium-doped TeO2-coated Si3N4 waveguide amplifiers with 5 dB net gain. Photonics Res. 8, 127–134 (2020).

Vu, K. & Madden, S. Tellurium dioxide erbium doped planar rib waveguide amplifiers with net gain and 2.8 dB/cm internal gain. Opt. Express 18, 19192–19200 (2010).

Liu, Y. et al. A photonic integrated circuit-based erbium-doped amplifier. Science 376, 1309–1313 (2022).

Subramanian, A. Z., Murugan, G. S., Zervas, M. N. & Wilkinson, J. S. Spectroscopy, modeling, and performance of erbium-doped Ta2O5 waveguide amplifiers. J. Lightwave Technol. 30, 1455–1462 (2012).

Bonneville, D., Osornio-Martinez, C., Dijkstra, M. & García-Blanco, S. High on-chip gain spiral Al2O3:Er3+ waveguide amplifiers. Opt. Express 32, 15527–15536 (2024).

Cai, M. et al. Monolithic tunable dual-wavelength laser utilizing erbium-doped lithium niobate on an insulator. Opt. Lett. 49, 3018–3021 (2024).

Zhang, M., Wang, C., Kharel, P., Zhu, D. & Lončar, M. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators: when performance meets scalability. Optica 8, 652–667 (2021).

Nedeljkovic, M., Soref, R. & Mashanovich, G. Z. Free-carrier electrorefraction and electroabsorption modulation predictions for silicon over the 1-14 μm infrared wavelength range. IEEE Photonics J. 3, 1171–1180 (2011).

Hiraki, T. et al. Membrane InGaAsP Mach–Zehnder modulator integrated with optical amplifier on Si platform. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 3030–3036 (2020).

Shi, Y., Yan, L. & Willner, A. E. High-speed electrooptic modulator characterization using optical spectrum analysis. J. Lightwave Technol. 21, 2358 (2003).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101–104 (2018).

Suche, H., Hiller, D., Baumann, I. & Sohler, W. Integrated optical spectrum analyzer with internal gain. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 7, 505–507 (1995).

Xu, Q. et al. Er3+-doped lithium niobate thin film: a material platform for ultracompact, highly efficient active microphotonic devices. Adv. Photonics Res. 2, 2100081 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. On-chip integrated waveguide amplifiers on erbium-doped thin-film lithium niobate on insulator. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2100030 (2021).

Bao, R. et al. An erbium-doped waveguide amplifier on thin film lithium niobate with an output power exceeding 100 mW. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2400765 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Erbium-ytterbium codoped thin-film lithium niobate integrated waveguide amplifier with a 27 dB internal net gain. Opt. Lett. 48, 4344–4347 (2023).

Cai, M. et al. Erbium-doped lithium niobate waveguide amplifier with internal net gain exceeding 20 db. In CLEO: Science and Innovations, SW3O–3 (Optica Publishing Group, 2024).

Feng, H. et al. Integrated lithium niobate microwave photonic processing engine. Nature 627, 80–87 (2024).

Zhou, P. et al. High-gain erbium silicate waveguide amplifier and a low-threshold, high-efficiency laser. Opt. Express 26, 16689–16707 (2018).

Taherunnisa, S. et al. Effect of up-conversion luminescence in Er3+ doped phosphate glasses for developing Erbium-doped fibre amplifiers (EDFA) and G-LED’s. Optical Mater. X 3, 100034 (2019).

Gaafar, M. A. et al. Femtosecond pulse amplification on a chip. Nat. Commun. 15, 8109 (2024).

Chen, T., Lee, H., Li, J. & Vahala, K. J. A general design algorithm for low optical loss adiabatic connections in waveguides. Opt. Express 20, 22819–22829 (2012).

Xu, M. et al. Dual-polarization thin-film lithium niobate in-phase quadrature modulators for terabit-per-second transmission. Optica 9, 61–62 (2022).

He, M. et al. High-performance hybrid silicon and lithium niobate Mach–Zehnder modulators for 100Gbit s−1 and beyond. Nat. Photonics 13, 359–364 (2019).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Hybrid-integration of SOA on silicon photonics platform based on flip-chip bonding. J. Lightwave Technol. 37, 307–313 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Ultra-broadband and low-loss edge coupler for highly efficient second harmonic generation in thin-film lithium niobate. Adv. Photonics Nexus 1, 016001–016001 (2022).

Hu, C. et al. High-efficient coupler for thin-film lithium niobate waveguide devices. Opt. Express 29, 5397–5406 (2021).

Bonneville, D. B., Frankis, H. C., Wang, R. & Bradley, J. D. Erbium-ytterbium co-doped aluminium oxide waveguide amplifiers fabricated by reactive co-sputtering and wet chemical etching. Opt. Express 28, 30130–30140 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Highly efficient on-chip erbium-ytterbium co-doped lithium niobate waveguide amplifiers. Photonics Res. 11, 1733–1737 (2023).

Singh, N. et al. Watt-class CMOS-compatible power amplifier. In European Quantum Electronics Conference, pd_1_6 (Optica Publishing Group, 2023).

Zhang, B., Chen, Y., Zhao, Z. & Wang, Y. Progress and applications of active optical fibers. Appl. Phys. 8, 256–268 (2018).

Ding, R. et al. High-speed silicon modulator with slow-wave electrodes and fully independent differential drive. J. Lightwave Technol. 32, 2240–2247 (2014).

Han, C. et al. Slow-light silicon modulator with 110-GHz bandwidth. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi5339 (2023).

Zhu, S. et al. Waveguide-integrated two-dimensional material photodetectors in thin-film lithium niobate. Adv. Photonics Res. 4, 2300045 (2023).

Guo, Q. et al. Ultrafast mode-locked laser in nanophotonic lithium niobate. Science 382, 708–713 (2023).

Singh, N. et al. Silicon photonics-based high-energy passively Q-switched laser. Nat. Photonics 18, 485–491 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Broadband electro-optic frequency comb generation in a lithium niobate microring resonator. Nature 568, 373–377 (2019).

Stokowski, H. S. et al. Integrated frequency-modulated optical parametric oscillator. Nature 627, 95–100 (2024).

Mattarelli, M. et al. Characterization of erbium doped lithium niobate crystals and waveguides. Optical Mater. 28, 1292–1295 (2006).

Jin, C. et al. Fabrication of lithium niobate metasurfaces via a combination of FIB and ICP-RIE. Chin. Opt. Lett. 20, 113602 (2022).

Chang, C.-M. et al. A parametric study of ICP-RIE etching on a lithium niobate substrate. In 10th IEEE International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems, 485–486 (IEEE, 2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (62235002, 62327811, 62322501, 12204021), China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (BX20240014) and High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University. The authors thank Zhangfeng Ge, Yan Zhou and Xing Liu in Peking University Yangtze Delta Institute of Optoelectronics for providing equipments and Zixuan Zhang in Peking University for device electron microscopy. The IOPTEE and Hchiptech nano-fabrication facility was used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea was conceived by Y.M.W., B.W. and B.S. The device simulation was established by Y.M.W. and Y.Z. The simulation model was established by B.W. and P.Z. The experimental setup was performed by Y.M.W. The loss measurement was performed by Y.W. with assistance by S.Y. The gain experiment was performed by Y.M.W., H.S. and B.S. with assistance by D.S., L.Y., Z.L. and Y.C.W. The modulation experiment was performed by Y.M.W., L.Y. and Y.Z. with assistance by L.X. and H.W. The results were analyzed by Y.W. with assistance by R.C., S.Y., Y.C.W., X.Z., Z.T. and W.L. All authors participated in writing the manuscript. The project was under the supervision of B.S, H.S. and X.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jonathan Bradley and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Shen, B., Wang, B. et al. Unifying optical gain and electro-optical dynamics in Er-doped thin-film lithium niobate platform. Nat Commun 16, 10462 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65460-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65460-1