Abstract

All-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations based on physics-based force fields serve as an essential complement to experiments for investigating protein structure, dynamics, and interactions. Despite significant advances in force field parameterization, achieving a consistent balance of molecular interactions that stabilize folded proteins while accurately capturing the conformational dynamics of intrinsically disordered polypeptides in solution remains challenging. In this work, we introduce two refined force fields which incorporate either a selective upscaling of protein-water interactions or targeted improvements to backbone torsional sampling: (i) amber ff03w-sc, and (ii) amber ff99SBws-STQ′. Extensive validation against small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy observables revealed that both force fields accurately reproduced the chain dimensions and secondary structure propensities of IDPs. Importantly, both force fields also maintained the stability of single-chain folded proteins and protein-protein complexes over microsecond-timescale simulations. Overall, our refinement strategies result in transferable force fields with improved accuracy for simulating diverse protein systems, ranging from folded domains to IDPs and protein-protein complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations based on physics-based energy functions referred to as “force fields” are now an invaluable and complementary tool to experiments in the investigation of protein structure, dynamics, and interactions associated with cellular processes1,2. With significant advances in simulation hardware and the widespread availability of conformational sampling algorithms, accessing functionally relevant biomolecular dynamics and interactions that occur on the multi-microsecond to sub-millisecond timescale are now routinely feasible3. Importantly, these advances have also enabled a rigorous evaluation of force field accuracy against experimental measurements with regard to their propensity to populate various secondary structure classes and the strength of non-bonded interactions between various chemical groups4.

After nearly two decades of force field parameterization against crystallography, spectroscopic, and ab initio calculations, modern force fields belonging to the four major families—AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, and GROMOS—succeeded in providing a reasonable description of the structure and dynamics of folded proteins but performed poorly for short peptide ensembles in solution5,6. At present, a major emphasis and goal of modern atomistic force field development is the parameterization of transferable models which can simultaneously describe the structural stability of folded domains while capturing the transient secondary structure and global chain dimensions of intrinsically disordered polypeptides7,8,9,10,11. A major step towards arriving at these goals involved the extensive comparison of simulation ensembles against nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy observables (chemical shifts and scalar couplings) for weakly structured peptides in solution, first carried out by Best and Hummer12. Based on these observations, global empirical corrections were applied to either ϕ or ψ backbone torsional potential for non-glycine/proline residues to adjust the helix-coil or PPII-β conformational equilibria, which led to amber ff99SB*/ff03*/ff99SBϕ13,14 and charmm22*/3615,16 force fields, which achieved an improved balance between the secondary structure classes and successfully folded both α-helical and β-sheet proteins. Notably, a similar strategy based on comparison with scalar couplings resulted in accurate sampling of side chain rotamers for isoleucine (I), leucine (L), aspartate (D), and asparagine (N) residues in ff99SB, giving rise to ff99SB*-ILDN 5,15.

Despite extensive reparameterization of backbone and side chain torsion parameters, the widespread use of primitive three-site water models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E) consistently led to weak temperature-dependent cooperativity for protein folding17, overly collapsed structural ensembles for IDPs6,18,19, and excessive protein–protein association across the major force field families20. To remedy issues arising from weak protein–water interactions, subsequent efforts involved pairing protein force fields with accurate four-site (rigid) water models21,22,23,24. The adoption of these improved water models was a key step toward rebalancing protein–water interactions and led to improved modeling of IDP ensembles. Among these efforts, the ff99SB*/ff03* force fields were combined with the TIP4P2005 water model, along with additional upscaling (10%) of protein–water interactions and a readjustment of the global correction for ψ backbone torsion angle applied to maintain the helix-coil equilibrium for model peptides25. These modifications resulted in the ff99SBws/ff03ws force fields, which showed considerable improvements in global and structural properties computed for disordered polypeptides (from smFRET and SAXS) and reduced excessive protein–protein association25,26,27. These efforts were soon followed by a reparameterization of charmm36 (charmm36m) to alleviate its tendency to form left-handed α-helices, including the adoption of a modified TIP3P water with additional LJ parameters on its hydrogen atoms to enhance protein–water interactions and improve the conformational description of IDPs28. Robustelli et al. paired ff99SB-ILDN with a modified TIP4P-D water model and a Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameter modification to increase the strength of backbone hydrogen bonding, resulting in ff99SB-disp, which exhibited state-of-the-performance for both folded proteins and IDP ensembles across a wide range of test systems chosen in the study29. Along similar lines, a version of ff99SB optimized to reproduce the residue-specific torsional angle distributions observed for the PDB coil library, RSFF230, yielded highly accurate thermodynamics of protein folding when coupled with TIP4P-D water (RSFF2+)31. Other popular variants of ff99SB, such as ff14SB/19SB32,33, also alleviate excessive protein–protein association and yield more accurate IDP conformational ensembles when paired with four-site water models such as TIP4P200534 and OPC35. As an alternative to the adoption of computationally expensive four-site water models, Yoo and Aksementiev performed a reparameterization of atom pair-specific LJ parameters in charmm/amber force fields against osmotic pressure data to mitigate the over-stabilization of salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions in TIP3P water 36,37,38.

Despite steady progress towards the development of “balanced” force fields over the last decade, numerous independent investigations reported discrepancies pertaining to certain IDP sequences, folded protein stability, and protein–protein association. For instance, ff03ws significantly overestimated (>16%) the chain dimensions of the RS peptide compared to experiment18. Further, replica-exchange simulations of WW domains indicated that ff03ws strongly destabilized the folded state37. Recent all-atom MD studies of Fused in Sarcoma (FUS), a multidomain RNA-binding protein (526 residues) with long disordered regions, also captured the structural instability of its folded RNA recognition motif (RRM) domain over the microsecond simulations with ff03ws39,40. Two independent studies that investigated the suitability of charmm36m, ff19SB-OPC, and ff99SB-disp revealed discrepancies pertaining to the solubility of Aβ16-22 peptides41 and ubiquitin self-association42, for all three force fields. These studies revealed that ff99SB-disp overestimates the strength of protein–water interactions, failing to predict β-aggregation for Aβ16-22 and weak dimerization (millimolar affinity) of ubiquitin. In contrast, charmm36m correctly predicted the aggregation behavior of Aβ16-22 wild type and two mutants, while ubiquitin self-association was found to be too strong. ff19SB-OPC exhibited intermediate behavior, giving rise to only a small population of β-aggregates for Aβ16-22 but successfully predicted weak dimerization of ubiquitin through the known interacting surfaces. To address issues related to weak protein–protein association for ff99SB-disp, Piana et al. recently proposed a reparameterization of both dihedral parameters and non-bonded interactions against osmotic pressure data43. While the reparametrized force field, referred to as DES-amber, increased the stability of protein complexes, the association free energies were still underestimated compared to experiment for some systems. Collectively, the above findings indicate that the optimal balance between protein–protein and protein-solvent interactions among modern classical force fields is yet to be fully realized.

In this work, we re-evaluate the accuracy and transferability of two Amber force fields, ff03ws and ff99SBws25, in describing the structural dynamics of both folded proteins and IDPs. We introduce two refined variants: ff03w-sc, which applies selective –water scaling to improve folded protein stability while maintaining accurate IDP ensembles, and ff99SBws-STQ′, which incorporates targeted torsional refinements of glutamine (Q) to correct overestimated helicity in polyglutamine tracts. Extensive validation against NMR and SAXS data shows that both force fields accurately reproduce IDP dimensions and secondary structure propensities, while also maintaining the stability of folded proteins and protein–protein complexes. Together, these refinements yield balanced, transferable force fields for simulating diverse protein systems.

Results

Stability of folded proteins

Recent efforts to develop “balanced” force fields—achieved by modifying protein–water van der Waals interactions or re-parameterizing water models to incorporate stronger dispersion forces—have significantly improved the prediction of global chain properties for many intrinsically disordered proteins, while maintaining essential local structural features9,23,25,26,29. However, these advancements come with a potential drawback: the strengthened protein–water interactions to better represent the IDP ensemble may inadvertently compromise the conformational stability of folded proteins23,25,29,44. To evaluate this potential issue with amber ff03ws and ff99SBws force fields, we investigated the stability of two model folded proteins: Ubiquitin (PDB ID: 1D3Z)45, a highly conserved and stable protein with well-characterized conformational dynamics across the picosecond-millisecond timescale46,47, and the Nle-double mutant of the Villin headpiece (HP35) (PDB ID: 2F4K)48, an ultrafast-folding protein48,49.

Four independent simulations (2.5 μs each) performed using ff03ws revealed significant instability for both proteins. For Ubiquitin, the most populated state deviated by approximately 0.4 nm in backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) from the X-ray crystal structure (excluding the flexible C-terminal tail, residues 71–76), with local unfolding of the α-helix observed in one replica as indicated by per-residue root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1A) and visualized over the trajectory movie (Supplementary Movie 1). Similarly, simulations of Villin HP35 exhibited pronounced structural deviations from the native state with unfolding events observed after 1 µs (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. 1B, Supplementary Movie 1). In contrast, the ff99SBws force field effectively maintained the structural integrity of both Ubiquitin and Villin HP35 over the simulation timescale (Figs. 1C, D and S1). For Ubiquitin, RMSD and RMSF values remained consistently low (<0.2 nm) across all four independent simulations (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 1A, Supplementary Movie 2). Villin HP35 exhibited slightly larger structural fluctuations, with minor conformational rearrangements in the C-terminus (residues 30-35); however, the overall RMSD and RMSF remained predominantly below 0.2 nm (Figs. 1D and S1B, Supplementary Movie 2). This comparative analysis reveals that the ff99SBws force field effectively maintains native conformational states of both Ubiquitin and Villin HP35, whereas ff03ws exhibits notable destabilization with significant conformational rearrangements, indicating its potential limitations for microsecond-timescale MD simulations of folded proteins.

Analysis of backbone RMSD for Ubiquitin and Villin headpiece (HP35) simulated with the Amber ff03ws (A, B) and ff99SBws (C, D) across four independent simulations. The red dashed line indicates an RMSD of 0.2 nm, serving as the upper reference limit for conformational stability. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Modifications to the protein–water scaling scheme in Amber ff03ws

In folded proteins, structural stability is maintained through a combination of hydrogen bonding involving primarily the polypeptide backbone, and hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions mediated by side chain atoms. To investigate the relative contributions of the backbone and side chains to Ubiquitin’s stability, we initially tested two modified variants of the ff03ws force field. These variants selectively scaled protein–water LJ interactions by 10% (as described by Best et al.25) for either backbone heavy atoms (backbone scaling) or side chain atoms (side-chain scaling, excluding glycine). Similar to the original ff03ws, backbone scaling resulted in increased structural deviations (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 2C, Supplementary Movie 3), indicating a decrease in conformational stability. In contrast, side-chain scaling significantly improved the overall structural integrity of the simulation ensemble with respect to the initial structure, with RMSD fluctuations between 0.2 and 0.5 nm (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Movie 3), and RMSF values remained largely below 0.2 nm except for the disordered C-terminal region.

A Time-dependent backbone RMSD of ubiquitin using three test scaling schemes derived from ff03ws: backbone scaling, side chain scaling for all non-glycine residues, and the final ff03w-sc scheme with side chain scaling for uncharged residues only. B Violin plots showing the distribution of backbone RMSD values for six folded proteins—Ubiquitin (Ubq), HEWL, BPTI, GB3, Villin HP35, and GTT variant of WW domain—simulated using ff03w-sc and ff99SBws. Each distribution combines framewise RMSD values from n = 4 independent simulations per system; the inner box marks the median and interquartile range (IQR). C Box plots of the fraction of native contacts retained over the course of simulations, calculated using the method of Best et al.57. Each box spans the IQR (25th–75th percentile), the center line indicates the median, and whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR; minima and maxima within this range are shown, and outliers were omitted. Each system includes n = 4 independent simulations. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Charged residues are crucial for the regulation of protein stability, as they can engage in electrostatic interactions with both solvent and other residues through intra-protein salt bridges50. We therefore strategically excluded all charged residues (Lys, Arg, Asp, and Glu) from our side-chain scaling approach for several reasons. First, the parent ff03 already demonstrates robust performance in modeling salt-bridge interactions, with equilibrium association constants in good agreement with experiment, irrespective of the water model51. Second, the ff03w force field, derived from ff03* paired with the optimized TIP4P/2005 water model, yields charged side-chain hydration free energies that closely approximate experimental measurements52. Third, within our side-chain scaling framework, charged residues—which comprise approximately 30% of ubiquitin—exhibited notable deviations in solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) relative to the experimental structure (Supplementary Fig. 2). Excluding charged residues from the side-chain scaling scheme led to substantially enhanced ubiquitin stability, characterized by RMSD values consistently below 0.2 nm and reduced the solvent accessibility of charged residues (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 2C, D, Supplementary Movie 3). These improvements indicate a more stable folded conformation. This final variant, which selectively scales only uncharged side chains, is referred to as ff03w-sc and results in substantially enhanced stability for Ubiquitin.

To assess the robustness of this modified force field, we applied it to the folded state of Villin HP35, which had previously unfolded in simulations using the original ff03ws. With ff03w-sc, Villin HP35 exhibited substantially reduced structural fluctuations, with backbone RMSD and RMSF values consistently remaining below 0.2 nm (Supplementary Fig. 3A, Supplementary Movie 4), indicating improved structural stability. We further tested ff03w-sc on four additional folded proteins—GB3 (PDB ID: 1P7E)53, BPTI (PDB ID: 5PTI)54, HEWL (PDB ID: 6LYZ)55, and GTT variant of the WW domain (PDB ID: 2F21, a small β-sheet)56 —known to be destabilized by ff03ws29. While the backbone RMSD distributions for these proteins were relatively broad, they remained centered around 0.2–0.3 nm (Fig. 2B), suggesting a moderate degree of flexibility with higher RMSF values primarily localized to loop regions (Supplementary Fig. 3B–F). Overall, the proteins retained native-like conformations throughout the μs-long simulations.

To provide a more rigorous assessment of structural stability, we analyzed the fraction of native inter-residue contacts, following the approach by Best et al.57, for all six proteins using both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws. As shown in Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 4, both force fields maintained high native contact fractions (>90%) across all systems. Interestingly, simulations using the ff99SBws force field consistently exhibited not only lower RMSD values (<0.2 nm) but also higher median fractions of native contacts with tighter distributions (Fig. 2B, C), indicating greater stability and closer adherence to native structures. Notably, ff99SBws also employs a 10% increase in protein–water interaction strength for all protein atoms, similar to the approach used in the original ff03ws25. Secondary structure analysis further confirmed that both α-helical and β-sheet content remained stable with minimal temporal variation throughout the simulations for all proteins (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). These findings demonstrate that ff03w-sc substantially improves protein structural integrity over microsecond timescales compared to the original ff03ws, while ff99SBws shows more robust performance in maintaining folded protein stability across a diverse set of test systems.

To further assess force field performance on folded proteins, we investigated their ability to capture backbone dynamics on the ps-ns timescale by calculating the amide order parameters (S²) for ubiquitin and compared them to the NMR-derived values (Supplementary Fig. 7). While the refined ff03w-sc force field successfully stabilized the overall structure of ubiquitin, it exhibited the known tendency of ff03-based force fields to overestimate backbone flexibility, particularly in loop regions where simulated S² values were consistently lower than experimental measurements (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Similar challenges have also been observed for polarizable models, where explicit inclusion of electronic polarization improves local electrostatics but does not necessarily enhance the accuracy of flexible loop dynamics, underscoring the importance of balancing bonded and non-bonded interactions58. In contrast, ff99SB-based force fields demonstrated better performance, yielding S² order parameters in excellent agreement with NMR across the entire protein and indicating more accurate descriptions of both rigid and flexible regions (Supplementary Fig. 7B). These results highlight the differential performance of the two force field families in capturing local backbone dynamics.

Chain dimensions of IDPs

To evaluate the suitability of the force fields in simulating IDPs, we determined the temperature-dependent radius of gyration (Rg) for a 34-residue fragment of Cold-shock protein (CspM34) using parallel tempering in a well-tempered ensemble (PT-WTE) to enhance conformational sampling59,60. Fig. 3A presents the Rg of CspM34 as a function of temperature for ff03w-sc and ff99SBws, compared to two reference force fields, ff03w and ff03ws. The experimental Rg estimate for CspM34 at 300 K, derived from FRET measurements using a Gaussian chain model61,62, is approximately 1.6 nm. Across the temperature range, ff03ws consistently maintained extended conformations, yielding an Rg value of 1.65 ± 0.01 nm at 300 K, which is marginally closer to the experimental measurement (~1.6 nm) than the other force fields. In contrast, ff03w produced more compact structures, with an Rg of 1.35 ± 0.1 nm at 300 K and decreasing further at elevated temperatures. Both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws yielded intermediate chain dimensions, with Rg values of 1.52 ± 0.01 nm and 1.53 ± 0.01 nm at 300 K, respectively.

A Radius of gyration of CspM34 as a function of temperature. Results are shown for ff03ws, ff03w-sc, ff99SBws, and ff03w, respectively. Yellow plus signs indicate values estimated from FRET measurements62. The experimental value at 300 K is indicated by the red dashed line. B–D SAXS profiles of Histatin5, RS Peptide, and S(129–146) peptide. The experimental data (gray), taken from Saga et al.63 for Histatin5, Rauscher et al.18 for RS peptide, and Koren et al.64 for S(129–146), are overlaid with the simulated scattering profiles. The structure inset displays the conformational ensembles. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

We further investigated the influence of side-chain scaling on the conformational dimensions of CspM34. Variants using 10% increase in side-chain scaling, both with and without charged residues, produced comparable Rg values (1.51 ± 0.01 nm and 1.52 ± 0.01 nm at 300 K, respectively), although excluding charged residues led to slightly more collapsed conformations at higher temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 7A). These results suggest that the side-chain scaling of uncharged residues does not substantially alter the chain dimensions of CspM34. We note that 10% increase in protein side chain–water interactions used in ff03w-sc represents a near-optimal balance between maintaining folded protein structural stability and preventing over-collapse of disordered proteins. To further illustrate this trade-off, we also tested a stronger 15% scaling factor. While this higher affinity can yield more realistic chain dimensions for some disordered proteins, it also leads to the destabilization of folded proteins (Supplementary Fig. 8A–C). Therefore, although 10% scaling may not always yield the closest agreement with experimental data for every individual system, it provides reliable transferability across diverse protein systems. Based on this analysis, we adopted 10% scaling as the final choice for ff03w-sc throughout this study. Notably, this optimal scaling is specific to the base force field, as applying the same 10% side-chain adjustment to ff99SBws resulted in overly collapsed conformations of CspM34 (Supplementary Fig. 8D).

To further assess the accuracy of CspM34 ensembles generated by ff03w-sc and ff99SBws, we compared their SAXS profiles to experimental data. As an initial validation system, we selected Histatin5, a 25-residue peptide enriched in hydrophilic amino acids (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), which are known to promote conformational disorder compared to hydrophobic residues that are typically found in stable protein cores. Using PT-WTE simulations, we computed the SAXS profiles from the 302 K replica. Figure 3B illustrates the comparison between experimental and simulated SAXS scattering curves for Histatin5. Both force fields demonstrated excellent agreement with experimental data, within error margins. Notably, the Rg values derived from the experimental SAXS profile63 (13.9 ± 0.1 Å) closely matched the predictions from both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws ensembles (13.8 Å).

Further validation was performed using the RS peptide and the fragment S(129–146) of the NFLt sequence (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Previous studies reported that ff03ws overestimated the Rg of RS peptide by ~16%18. In contrast, ff03w-sc produced SAXS profiles in excellent agreement with experimental measurements (Fig. 3C), yielding a theoretical Rg value of 12.7 ± 0.1 Å compared to the experimental value of 12.6 ± 0.1 Å. For the S(129–146) fragment64, which features alternating charged blocks that potentially facilitate salt-bridge interactions, the ff99SBws ensemble predicted a SAXS profile that aligned well with experimental data (Fig. 3D). The predicted Rg value of 12.8 ± 0.1 Å agrees closely with the experimental measurement of 12.9 ± 0.1 Å. Although ff99SB-based force fields were previously reported to overestimate salt-bridge strength51, this effect appears negligible for the S(129–146) fragment. Its moderate net negative charge (−4) and the alternating pattern of acidic (E/D) and basic (K) blocks likely promote transient rather than persistent salt bridges, while the fragment’s inherent conformational flexibility potentially further prevents their over-stabilization.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws achieve robust agreement with experimental Rg values and SAXS profiles, thereby establishing their reliability in modeling the chain dimensions of small IDPs.

α-helix formation in Ace-(AAQAA)3-NH2

While accurately sampling chain dimensions in disordered peptides is crucial, it is equally important to ensure that modifications to protein–water interactions do not compromise the stability of folded motifs, such as α-helices, which may be transiently populated in unfolded states and IDPs such as the TDP-43 low-complexity domain65. To assess this balance, we investigated a 15-residue helix-forming peptide—Ace-(AAQAA)3-NH2, which exhibits approximately 30% helix content at 300 K and has a well-characterized temperature-dependent helix propensity from previous NMR studies and has become an established reference system for force field validation66. Fig. 4 illustrates the temperature-dependent helix propensity computed using ff03ws, ff03w-sc, and ff99SBws force fields. ff03w-sc, incorporating scaled side chain–water interactions, demonstrated enhanced helix stability compared to ff03ws and accurately reproduced a residual helix fraction closely aligned with NMR data at 300 K. In contrast, ff99SBws consistently overestimated the α-helical content across the temperature range and predicted elevated helicity for most residues (Fig. 4, inset). The results highlight the significant improvement achieved by ff03w-sc in stabilizing α-helix formation of the (AAQAA)3 peptide, while highlighting the need for further refinements to ff99SBws in order to accurately model the residual helicity in disordered states.

Helix fraction of (AAQAA)3 as a function of temperature simulated in ff03ws, ff03w-sc, and ff99SBws, respectively. Experimental data (Exp.) were calculated from the carbonyl chemical shifts reported by Shalongo and Stellwagen66. The inset shows the residual helix fraction at 300 K. Mean helix fractions and associated standard errors were estimated by block averaging over five equal-length blocks of the trajectory. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Refinement of glutamine backbone torsion parameters in ff99SBws-STQ

Recognizing the limitations of existing force fields in accurately capturing amino acid-specific conformational preferences across diverse sequence contexts, we previously introduced targeted corrections to ff99SBws, which lowered the backbone torsion potential parameter (kψ) for serine (S), threonine (T), and glutamine (Q) from 2.0 kJ/mol to 1.0 kJ/mol, thereby decreasing the bias toward helical structures67. This refined force field—ff99SBws-STQ, substantially improved the prediction of residue-level α-helical populations in all-atom simulations of low-complexity domain (LCD) fragments derived from TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), FUS, and the C-terminal heptad repeat domain of RNA Polymerase II (RNA Pol II)67. However, simulations of the N-terminal fragment of Httex1, comprising N17 (17 amino acids), Q16 (polyglutamine), and a minimal stretch of five prolines (P5), revealed persistent discrepancies with regard to residue-level helicity in the polyQ region: ff99SBws exhibited substantial overestimation, while ff99SBws-STQ showed significant underestimation (Fig. 5A). To address this issue, we revisited the torsion correction for glutamine and tested intermediate kψ values (between 1.0 and 2.0 kJ/mol). We found that kψ = 1.50 kJ/mol effectively corrected the bias, accurately reproducing experimental helicity in the polyQ region, with a root mean square error (RMSE) of 5.1% between simulated and experimental helix fractions (Supplementary Table 3). The revised force field, designated ff99SBws-STQ′, not only resolved the helicity discrepancies in the polyQ region but also reproduced the experimental helix fraction of the (AAQAA)3 peptide across a wide temperature range, showing excellent agreement with NMR measurements at 300 K (Fig. 5B).

A Residual helix fraction of H16, simulated with three amber ff99SBws-based force fields: ff99SBws, ff99SBws-STQ, and ff99SBws-STQ′ (kψ (Q) = 1.5 kJ/mol). NMR-derived results are taken from Urbanek et al.114,115. B Residual helix fraction of (AAQAA)3 as a function of temperature simulated with ff99SBws and ff99SBws-STQ′. The inset shows the temperature-dependent helix fraction. Mean helix fractions and associated standard errors were estimated by block averaging over five equal-length blocks of the trajectory. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

To further establish the reliability of ff99SBws-STQ′, we performed a comprehensive set of validation simulations on a diverse set of both folded and disordered proteins. First, we assessed its ability to maintain the stability of folded states using the same set of six well-characterized proteins tested for ff03w-sc and ff99SBws in this study (Fig. 2B, C). These simulations yielded stable structural ensembles with RMSD values typically below 0.2 nm and a high preservation of native inter-residue contacts (>90%), comparable to those obtained with ff99SBws (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B). We then benchmarked ff99SBws-STQ′ against experimental SAXS data for the three disordered sequences: Histatin5, RS peptide, and the S(129–146) fragment. The simulated SAXS profiles closely matched experimental scattering curves (Supplementary Fig. 9C–E), with predicted Rg values in excellent agreement with experimental measurements (Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, we evaluated 3JHN-HA scalar couplings for the RS peptide using multiple Karplus parameter sets (original Karplus68, Vogeli et al.69, DFT170, DFT270, and Larson et al.71; Supplementary Fig. 9F, Supplementary Table 5). ff99SBws-STQ′ shows the closest overall agreement with experimental values, with most residues falling within experimental uncertainty (especially with DFT1/DFT2), whereas ff99SBws slightly underestimates couplings for some central serine residues. In contrast, ff03w-sc systematically underestimates couplings across most sequence positions, consistent with prior observations for ff03-based models18. Together with global-dimension benchmarks, these results demonstrate that ff99SBws-STQ′ accurately captures global dimensions across tested systems and improves local backbone sampling for the RS peptide. However, a broader assessment of local structure across additional sequences remains an important direction for future work.

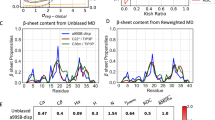

Secondary structure predictions for IDPs

To assess the applicability of ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ for capturing transient α-helix formation in IDPs, we examined prion-like LCDs, including FUS0−43, FUS120−163, TDP-43310−350, and RNA Pol II1927−197072,73,74. We strategically selected 44-residue fragments of these proteins to optimize computational efficiency while maintaining biologically relevant regions for which detailed NMR chemical shifts and secondary structure data are readily available, allowing direct validation of our simulation results. For these fragments, we employed PT-WTE simulations to ensure converged sampling of their equilibrium properties, as demonstrated by our convergence analysis (see “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 10). All subsequent analyses were performed using the replica at 302 K. Cα and Cβ chemical shifts were predicted using SPARTA+ for all IDP ensembles, and their conformational preferences were quantitatively assessed through secondary chemical shift difference (ΔδCα−ΔδCβ), a metric that discriminates between helical (positive values) and β-sheet (negative values) regions by comparing the observed chemical shifts against random coil reference values. Figure 6A shows that both force fields successfully captured the experimentally observed helix propensity within the core helix-forming region (residues 321–330) in TDP-43310–350, while deviations are present in other regions of the sequence. Both force fields predicted the correct helical propensities across the chosen LCD fragments, with the exception of the N-terminal region (residue 6–13) in FUS0–43, which was overly helical (Fig. 6), a discrepancy also reported for other force fields67. The RMSE values of simulated chemical shifts (ΔδCα−ΔδCβ) relative to experimental values for both force fields were consistently below 1 ppm (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 11), which is within the prediction error of SPARTA+75, implying the reasonable accuracy of both force fields in modeling IDP structural ensembles.

A, B Secondary chemical shift deviations (ΔCδα−ΔδCβ) for TDP-43310–350 and FUS0−43 as a function of residue index, respectively. Mean values and error bars for secondary chemical shift deviations were estimated by block averaging over five equal-length blocks. C, D Residual helix fraction of TDP-43310–350 and FUS0–43, respectively. Mean helix fractions and associated standard errors were estimated by block averaging over five equal-length blocks of the trajectory. Error bars for NMR-derived δ2D population per residue are 0.1 (10%). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

In addition, we calculated secondary structure propensities from the simulation trajectories based on the DSSP algorithm76 for each frame and averaged the helical assignments per residue over time. These propensities were compared to those predicted from experimental NMR chemical shifts using the δ2d web server77, which converts chemical shifts into residue-level secondary structure populations (Fig. 6C, D). For TDP-43, both force fields showed excellent correlation with experimental observations, accurately capturing partial helicity in the alanine-rich segment. In contrast, FUS0–43 simulations revealed distinct behaviors: ff03w-sc exhibited elevated helical populations (~40%) in the N-terminal region (residue 6–13), while ff99SBws-STQ′ simulations predicted more transient helical conformations (<15%), closely aligning with NMR observations (Fig. 5C, D, and Supplementary Fig. 12). Analysis of additional polar-rich LCDs, including FUS120–163 and RNA Pol II1927–1970, demonstrated that both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ predicted low helical populations (<20%), consistent with experimental measurements (Supplementary Fig. 11). For reference, a comparative analysis between ff99SBws-STQ′ and ff99SB-disp (Supplementary Fig. 13) revealed that ff99SB-disp overestimated the helicity in the polyQ tract of Httex1 (residue 28–32) and the N-terminal region of FUS0–43 (residue 6–16), while underestimating helix propensity in the helix-forming region of TDP-43310–350 (residue 321–330).

To further evaluate the force fields for systematic, residue-specific biases, we analyzed the chemical shift deviations averaged by amino acid type across all four low-complexity fragments (Supplementary Fig. 14). This analysis shows that for most residue types, both force fields yield average deviations close to zero, indicating good overall accuracy. However, some differences emerge for polar residues. The ff03w-sc force field shows notable positive deviations for serine and threonine (similar to ff03ws67), suggesting a persistent bias toward helical conformations for these residue types. These deviations are substantially reduced in the ff99SBws-STQ′ force field, which demonstrates the success of its targeted torsional refinements for serine, threonine, and glutamine and highlights its improved accuracy for modeling polar-rich disordered sequences.

Ala5 3J couplings

To evaluate the accuracy of backbone torsional sampling for the refined force fields, we performed 1-μs MD simulations of the alanine pentapeptide (Ala5) and computed scalar (3J) couplings from the simulation trajectories based on the Karplus equation with different parameter sets (Table 1). The predicted values compared to the experiment were estimated using the total χ² metric (excluding 3JCC), following the procedure described by Best et al.25. A χ² value of 1.0 indicates that prediction errors match the magnitude of experimental uncertainties (σi).

Similar to ff03ws25, ff03w-sc consistently yielded χ² values below 1.0 (ranging from 0.48 to 0.80) across all tested Karplus parameter sets. These favorable χ² results (see “Methods”) suggest that side-chain-specific scaling implemented in ff03w-sc does not adversely affect backbone dihedral angle sampling, at least in small peptides. In contrast, ff99SBws-STQ′ showed slightly elevated χ² values (ranging from 1.47 to 2.09) for most Karplus parameter sets except for DFT1 (χ² = 0.99), indicating a modest overestimation of scalar couplings compared to experimental data. Collectively, these Ala5 simulations provide additional quantitative assessment for both force fields. Despite their differing refinement strategies, both force fields exhibit reasonable agreement with experimental scalar coupling data, thereby supporting their ability to achieve a reliable sampling of the conformational landscape for small peptides.

Folding mini proteins

To benchmark the transferability of the refined force fields, we evaluated their ability to reproduce the folding thermodynamics of two well-studied mini-proteins: (i) Trp-cage, a 20-residue protein containing α-helical and 310-helical elements, and (ii) chignolin, a 10-residue β-hairpin. PT-WTE folding simulations (see “Methods”) were performed across a wide temperature range using both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ (Supplementary Movies 5 and 6). The fraction of folded structures was calculated using a distance RMSD (dRMS) threshold of 0.2 nm from the experimental structure, as defined previously25.

As shown in Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 15, ff03w-sc captures the qualitative cooperative melting behavior for both mini-proteins, consistent with previous observations reported for ff03ws25, while quantitative deviations from experiment are evident across the range. In contrast, ff99SBws-STQ′ significantly underestimates the folded populations of both systems, particularly near physiological temperatures, indicating destabilization of native conformations. These results reveal that while ff99SBws-STQ′ offers improved sampling of disordered peptide ensembles, ff03w-sc maintains better thermodynamic stability for small, folded proteins. This comparison highlights the complementary strengths and inherent trade-offs of the two force fields, emphasizing the importance of selecting an appropriate force field based on the system’s structural properties.

A Temperature-dependent folded fraction of Trp-cage and B chignolin, computed from replica-exchange simulations using ff03w-sc (blue squares) and ff99SBws-STQ′ (red circles). A structure is classified as folded if its distance RMSD (dRMS) from the experimental structure is less than 0.2 nm, as defined in a previous study25. Mean folded fractions and associated standard errors were estimated by block averaging over five equal-length blocks of the trajectory. The experimental melting curves (black lines) are included for comparison. Insets show the representative folded structures of Trp-cage (PDB ID: 1L2Y)116 and chignolin (PDB ID: 1UAO)117. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Protein–protein complexes

Modeling protein–protein interactions within molecular complexes remains a significant challenge for most current force fields, as the multifaceted balance of water-protein, intra-protein, and water-water interactions has been primarily optimized for isolated folded or disordered proteins. Previous simulations using state-of-the-art force fields (e.g., ff99SB-disp, charmm36m, and RSFF2+) have reported instability and dissociation of many protein complexes on microsecond timescales43. To evaluate the performance of our refined force fields, we assessed the ability of ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ to maintain stable protein–protein interfaces, focusing on four diverse complexes. Along with Barnase/Barstar (PDB ID: 1BRS)78 and SGPB/OMTKY3 (PDB ID: 3SGB)79—two systems previously identified as challenging for maintaining stability of protein–protein interactions43, we included two additional systems: CD2/CD58 (PDB ID: 1QA9)80—a β-sheet–mediated interface, and colE7/Im7 (PDB ID: 7CEI)81—a primarily α-helical complex. Each system was subjected to four independent 5-μs simulations per force field, starting from the experimentally determined structure (Supplementary Movies 7–10).

As shown in Fig. 8A, both force fields maintained the structural integrity of the complexes, with backbone RMSD values generally below 0.3 nm across all systems. ff99SBws-STQ′ consistently yielded higher populations of low-RMSD states, particularly for Barnase/Barstar and CD2/CD58, indicating enhanced structural stability. Time-evolution RMSDs of individual proteins within each complex followed similar trends (Fig. S16). To further evaluate interfacial stability, we analyzed two additional metrics: (i) the fraction of native contacts at the interface (Fig. 8B, Supplementary Fig. 17), and (ii) the interfacial surface area (Fig. 8C, Supplementary Fig. 18). Both force fields preserved high fractions of native interfacial contacts, with median stability values near 95% across the simulations. The interfacial surface areas remained tightly clustered around experimental reference values (red stars in Fig. 8C), with minimal deviations and no systematic drift over the simulation timescales.

Analyses of four protein complexes simulated using ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ’ force fields. The insets present the experimental structures of the complexes. A Distributions of the backbone RMSD of the full complexes. B Box plots showing the fraction of native contacts at the protein–protein interface from n = 4 independent simulations per system. Each box spans the interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentile), the center line indicates the median, and whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR; minima and maxima within this range are shown, and outliers were omitted. C Violin plots of interfacial surface area; each violin pools framewise values from n = 4 independent simulations per system. The inner box marks the median and interquartile range, and red stars indicate values from the experimental crystal structures. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Together, these results demonstrate that ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ successfully maintain stable protein–protein interfaces across diverse topologies. While ff99SBws-STQ′ showed slightly improved interfacial stability, both force fields exhibited robust performance in capturing the key features of protein complex stability over extended simulation times.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically re-evaluated two state-of-the-art amber force fields, ff03ws and ff99SBws, to address their limitations in stabilizing folded proteins and accurately modeling IDPs. By selectively scaling -water interactions, the modified ff03w-sc force field substantially improved the structural stability of folded proteins that were prone to destabilization with the original ff03ws. This improvement was consistently observed across a diverse set of six folded proteins, characterized by low backbone RMSD, high native contact retention, and preserved secondary structures. Notably, ff99SBws maintained native state stability without requiring additional rescaling.

We further revisited ff99SBws-STQ67, which incorporates residue-specific backbone torsional modifications to the ff99SBws base model, previously validated for accurate conformational sampling of LCD fragments. By fine-tuning the backbone torsional sampling for glutamine, the updated ff99SBws-STQ′ force field effectively mitigated the over-predicted helicity for the polyQ tract of Huntingtin Exon1, bringing simulated residual helicity in line with experimental data. This targeted approach demonstrates the value of optimizing force field parameters to resolve system-specific inaccuracies while maintaining overall transferability. Validation against experimental SAXS profiles for Histatin5, RS peptide, and the S(129–146) fragment, along with NMR-derived secondary structure for prion-like domains and scalar coupling analysis for RS peptide and Ala5, supports the robustness and transferability of the proposed force field refinements.

An additional critical test of the refined force fields involved evaluating their ability to maintain protein–protein complex stability, which has been recognized challenge for many existing models due to the delicate balance required between protein–water and protein–protein interactions. Using the Barnase/Barstar and SGPB/OMTKY3 complexes as model systems, we demonstrated that both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ reliably maintained the native stability of these complexes over microsecond simulations. To further validate these results across diverse interface types, we expanded the test set to include two additional complexes, CD2/CD58 and colE7/Im7, representing β-sheet and α-helical interfaces, respectively. In all four systems, both force fields preserved interfacial integrity, maintaining >95% of native contacts and interfacial surface areas in close agreement with experimental values. This robust performance stands in contrast with previous reports of instability and premature dissociation observed in similar complexes using other state-of-the-art force fields, such as ff99SB-disp and charmm36m43. The complementary performance of ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ in these systems underscores their ability to model complex intermolecular interaction networks beyond monomeric proteins. These findings substantially extend the applicability of the refined force fields to the investigation of biomolecular complexes, providing a reliable computational framework for studying protein–protein interfaces, molecular recognition mechanisms, and the hierarchical assembly of functional protein complexes.

A persistent challenge with ff03-based force fields is their tendency to overestimate backbone flexibility, particularly in disordered loop regions of Ubiquitin. While these force fields accurately reproduced the conformational rigidity of well-structured regions, such as α-helices and β-sheets (with S2 values > 0.8), significant deviations from experimental S2 values were observed in loop regions (Supplementary Fig. 7A). For example, simulations of Ubiquitin using ff03*/TIP3P maintained global structural stability, yet residues within loops, notably glycine residues (G47, G53) and charged residues (K48, R54, E64), exhibited greater flexibility relative to experimental S2 values (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Among ff03-based force fields paired with TIP4P/2005 water model, ff03w-sc achieved an improved balance between rigid and flexible regions but still showed discrepancies in the latter compared to experiment, highlighting the difficulty in accurately capturing flexible loop dynamics. The correction maps (CMAP)-optimized ff03CMAP and ff99SB nmr2 force fields employ residue-specific optimization of backbone dihedral potentials to address these imbalances, but they favor either folded or disordered systems depending on the water model (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P-Ew, TIP4P-D), rather than offering a unified solution82,83. In contrast, ff99SB-based force fields—such as ff99SBw, ff99SBws, and ff99SB-disp—consistently exhibited higher order parameters and aligned more closely with experimental data, particularly in loop regions (Supplementary Fig. 7B), reflecting their ability to capture backbone dynamics across both folded and disordered regions.

The refinements introduced in this study have addressed many challenges, including the over-predicted helicity in specific regions of LCDs. Both force fields demonstrate consistently small secondary chemical shift deviations Δ(ΔCα−ΔCβ) (<1 ppm) across many residue types (Supplementary Fig. 14), highlighting their improved accuracy. Notably, ff99SBws-STQ′ successfully reduced the helical bias in the polyQ tract of Huntingtin Exon1 that was observed in the parent force field—ff99SBws. However, some discrepancies remain, particularly for polar residues such as Ser and Thr in ff03w-sc, which exhibit significant deviations in secondary chemical shifts (Supplementary Fig. 14). While both ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′ effectively captured the secondary structure propensities for several polar-rich sequences (TDP-43, FUS, and RNA Pol II fragments), the helicity in the N-terminal region of FUS0–43 remained overestimated relative to experimental data. Additionally, the 3JHN–HA scalar couplings offer further insight into sequence-specific biases. For the RS peptide, ff03w-sc consistently underestimates the scalar couplings, a trend also observed in the original ff03w and ff03ws force fields. This underestimation may arise from backbone φ angle preferences that remain overly flexible or helical in polar-rich contexts. In contrast, ff03w-sc achieves good agreement with experiment for the short alanine-based peptide Ala5, with total χ² values consistently below 1.0 across multiple Karplus parameter sets. This suggests that ff03w-sc can reasonably capture φ angle distributions in small model systems, while its accuracy may degrade for more complex polar sequences. These observations indicate persistent sequence-specific biases, particularly in polar residue clustering and repetitive sequence motifs, highlighting the need for further parameterization and broader testing across diverse LCD and IDP sequences.

Choosing an appropriate force field for MD simulations requires careful consideration for specific systems, as no single force field is universally optimal. A preliminary literature review of studies involving similar systems is essential for identifying force fields with recognized strengths and weaknesses. For example, ff99SBws-STQ′ represents as a robust choice for simulating both folded proteins and IDPs due to its ability to appropriately model both structured and disordered regions. This force field demonstrates strong agreement with experimental observations of full-length multidomain proteins such as HP1α and TPD-4384,85,86,87, reliably reproduces the experimental ps-ns dynamics, as indicated by its accurate modeling of spin relaxation data (e.g., R1, R2, and hetNOE), thereby reflecting the disordered nature of the EWS LCD and its regional variations in relaxation behavior88. Although ff03ws tends to overestimate backbone flexibility in folded protein loops, it demonstrates strong agreement with R1, R2, and hetNOE data for disordered and partially disordered proteins, effectively modeling extended conformations and rotational dynamics under experimental ionic strengths89. For systems characterized by a high density of charged residues—such as DNA-binding proteins, their complexes, or highly charged IDPs—ff03w-sc offers advantages, as it effectively mitigates the over-stabilization of salt bridges, a common artifact observed in many force fields51. Furthermore, folding simulations of mini-proteins revealed that ff03w-sc yields higher folded populations and captures the qualitative melting transition for both Trp-cage and chignolin, despite quantitative deviations from experiment, while ff99SBws-STQ′ significantly underestimated folded fractions across temperature ranges, a behavior that was observed in other force fields, e.g., ff99SB-disp and charmm36m29. This suggests that accurately balancing local backbone propensities with global folding cooperativity remains a central challenge for developing widely applicable force fields.

In conclusion, this study advances the ongoing efforts to refine protein force fields, enhancing their utility in biomolecular simulations. The proposed force fields—ff03w-sc and ff99SBws-STQ′—achieve a balanced description of both folded and disordered ensembles and are well-suited for studying diverse systems, including folded proteins, disordered regions, and multiprotein complexes. These refinements help narrow the gap between theoretical predictions and experimental observations, enabling more predictive simulations of protein behavior. However, it is important to recognize that no single force field can perfectly capture the complexity of all protein systems—each model inevitably has distinct strengths and limitations depending on the specific structural and dynamic properties being investigated. Given this fundamental challenge, future work should focus on developing strategies to further refine these force fields to better balance local structural propensities with global folding cooperativity. Understanding the inherent trade-offs in force field design will be crucial for guiding these improvements and determining optimal applications for each model. Such efforts will pave the way for extending these improvements to larger, multidomain proteins and exploring their applicability under biologically relevant conditions, such as crowded intracellular environments and systems with post-translational modifications.

Methods

Simulations of folded proteins

All-atom MD simulations of Ubiquitin, GB3, BPTI, HEWL, Villin HP35 (with double nor-leucine substitutions at residues 24 and 29), protein complexes (Barnase/Barstar and SGPB/OMTKY3) were initiated in their folded states obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs: 1D3Z, 1P7E, 5PTI, 6LYZ, 2F4K, 1BRS, and 3SGB, respectively). Systems were prepared in Gromacs 2021.590 using truncated octahedron boxes with a length of 5.5 nm, except for HEWL and protein complexes, which required a larger box of 7.0 nm and 8.0 nm, respectively. After initial energy minimization in vacuum and solvation with TIP4P/2005 water22, Na+ and Cl− ions were added to achieve 150 mM salt concentration, using improved salt parameters from Lou and Roux91. Systems were equilibrated in a canonical ensemble (NVT) using a Nose-Hoover thermostat92 with a coupling constant of 1.0 ps at 300 K, followed by an isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) equilibration using a Berendsen barostat93 with an isotropic coupling constant of 5.0 ps at 1 bar. The Gromacs topologies and coordinates were then converted to Amber formats using ParmEd94, with hydrogen mass repartitioning95 to 1.5 amu to enable a 4 fs timestep. Subsequent simulations were carried out using the Amber22 MD simulation package. The initial minimization was performed using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms, with non-hydrogen atoms restrained by a 5 kcal/mol/Ų force constant. This was followed by two 5 ns NVT equilibration phases at 300 K: the first with reduced restraints (1 kcal/mol/Ų) and the second with all restraints removed. A subsequent 10 ns NPT equilibration employed a Monte Carlo barostat (with an isotropic coupling constant of 1.0 ps and a pressure of 1.0 bar) and Langevin dynamics for temperature regulation (with a friction coefficient of 1.0 ps−1). Bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm96. Short-range interactions were truncated at 0.9 nm, and long-range electrostatics were treated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method97,98. Finally, four independent NPT production replicas were conducted for each protein, using the same parameters as those used for equilibration.

Simulations of disordered proteins

Conformational sampling of disordered proteins was performed using PT-WTE59,60, a variant of temperature replica-exchange molecular dynamics (T-REMD)99. Simulations were conducted using Gromacs 2021.5 with the Plumed 2.8 plugin100,101. For each disordered protein sequence (Supplementary Table 1), an initial random coil conformation was generated and solvated in a truncated octahedron box containing 150 mM NaCl (using parameters from Lou and Roux) and counterions to neutralize the system. Fourteen temperature replicas, spanning 293–500 K, were employed. Long-range electrostatics were treated with the PME method with a 0.9 nm cutoff. To enhance computational efficiency, hydrogen mass repartitioning was employed, enabling a timestep of 5 fs. Bond constraints were applied using the LINCS algorithm102. Following temperature equilibration, production runs were conducted in the NVT ensemble with biasing potentials (bias factor = 48) deposited every 4 ps. These potentials enhanced fluctuations in the system’s potential energy, resulting in a well-tempered ensemble and improved conformational exchange between replicas. The initial Gaussian potential height and width were 1.5 and 195.0 kJ/mol, respectively, with exchange probabilities between adjacent replicas ranging from 30-45%. The residue helix fraction for Httex1-Q16 was taken from Mohanty et al.103, with an aggregate trajectory of ~45 μs.

Convergence of secondary structure propensities was assessed by analyzing the residual helicity at 302 K for each protein fragment. Consistent helix propensities were observed regardless of whether the entire trajectory, or trajectories excluding the initial 50 or 100 ns, were analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 11). Time-series plots of DSSP secondary structure assignments revealed transient structural behaviors, including periodic formation and melting of secondary structures throughout the trajectories (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 6). These dynamic transitions facilitated convergence in estimated secondary structure propensities, underscoring the robustness of the PT-WTE approach for modeling disordered proteins.

Trajectory analyses

Structural properties were analyzed using Gromacs tools to calculate backbone RMSD, RMSF, and radius of gyration (Rg). SAXS curves were generated using the CRYSOL104, and Rg values were determined from these curves using Guinier analysis in ATLAS Primus105. Chemical shift deviations were calculated using SPARTA+75 and compared to random coil reference values obtained from the Poulsen IDP server106. Secondary structure assignments from simulations were determined using gmx do_dssp107, which implements the DSSP algorithm76. The propensity for a given structure (e.g., helix fraction) for each residue was determined by averaging the per-frame secondary structure assignments over the entire trajectory. These propensities were then compared to experimental propensities derived from NMR secondary chemical shifts using δ2d software77. SASA were calculated using the gmx sasa utility, based on the algorithm of Eisenhaber et al.108. Backbone amide S² order parameters for ubiquitin were computed using the iRED method109,110 within the Python package pyDR111,112, with the trajectories divided into 1 µs blocks for analysis as recommended by Gu et al.110. Agreement between simulated and experimental observables was quantified by calculating the RMSE using ((xsim−xexp)²/N)½, where N is the number of residues sampled, and xsim and xexp represent the simulated and experimental values, respectively. The χ² metric used to quantify agreement between simulated and experimental 3J couplings for Ala5 was defined as described previously25:

where Jexpt,i and Jcalc,i are the experimental and computed scalar couplings, respectively, and σi is the estimated uncertainty associated with the predictions from the Karplus equation.

Three-dimensional structures and MD trajectories were visualized and animated using the VMD software 113.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw simulation trajectory data used to generate the source data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Initial and final protein structures used in the atomistic simulations, the refined force fields in GROMACS format with conversion scripts to AMBER, and input files for PT-WTE production simulations are available in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17314994). The following experimentally determined structures were used in this study: 1D3Z, 2F4K, 5PTI, 6LYZ, 2F21, 1L2Y, 1UAO, 1BRS, 3SGB, 1QA9, 1P7E, and 7CEI. The SAXS dataset for Histatin5 is available in SASBDB under accession: SASDHF8. Source data for all figures are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The scripts used to perform atomistic production simulations have been deposited in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17314994). All simulations and analyses were carried out using publicly available software packages, including AMBER, GROMACS, and MDAnalysis (https://www.mdanalysis.org/). Detailed analysis procedures and algorithms are described in the “Methods” section.

References

Huggins, D. J. et al. Biomolecular simulations: from dynamics and mechanisms to computational assays of biological activity. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 9, e1393 (2019).

Wereszczynski, J. & McCammon, J. A. Statistical mechanics and molecular dynamics in evaluating thermodynamic properties of biomolecular recognition. Q. Rev. Biophys. 45, 1–25 (2012).

Dror, R. O., Dirks, R. M., Grossman, J. P., Xu, H. & Shaw, D. E. Biomolecular simulation: a computational microscope for molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 429–452 (2012).

Bottaro, S. & Lindorff-Larsen, K. Biophysical experiments and biomolecular simulations: a perfect match? Science 361, 355–360 (2018).

Lindorff-Larsen, K. et al. Systematic validation of protein force fields against experimental data. PLoS ONE 7, e32131 (2012).

Henriques, J., Cragnell, C. & Skepö, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins: force field evaluation and comparison with experiment. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3420–3431 (2015).

Thomasen, F. E. & Lindorff-Larsen, K. Conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins and flexible multidomain proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 50, 541–554 (2022).

Kang, W., Jiang, F. & Wu, Y.-D. How to strike a conformational balance in protein force fields for molecular dynamics simulations? WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1578 (2022).

Huang, J. & MacKerell, A. D. Force field development and simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 48, 40–48 (2018).

Sawle, L., Huihui, J. & Ghosh, K. All-atom simulations reveal protein charge decoration in the folded and unfolded ensemble is key in thermophilic adaptation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 5065–5075 (2017).

Gaalswyk, K., Haider, A. & Ghosh, K. Critical assessment of self-consistency checks in the all-atom molecular dynamics simulation of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.2c01140 (2023).

Best, R. B., Buchete, N.-V. & Hummer, G. Are current molecular dynamics force fields too helical? Biophys. J. 95, L07–L09 (2008).

Best, R. B. & Hummer, G. Optimized molecular dynamics force fields applied to the helix−coil transition of polypeptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 9004–9015 (2009).

Nerenberg, P. S. & Head-Gordon, T. Optimizing protein−solvent force fields to reproduce intrinsic conformational preferences of model peptides. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 1220–1230 (2011).

Piana, S., Lindorff-Larsen, K. & Shaw, D. E. How robust are protein folding simulations with respect to force field parameterization? Biophys. J. 100, L47–L49 (2011).

Best, R. B. et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone ϕ, ψ and side-chain Χ1 and Χ2 dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3257–3273 (2012).

Best, R. B. & Mittal, J. Protein simulations with an optimized water model: cooperative helix formation and temperature-induced unfolded state collapse. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 14916–14923 (2010).

Rauscher, S. et al. Structural ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins depend strongly on force field: a comparison to experiment. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 5513–5524 (2015).

Mercadante, D. et al. Kirkwood–Buff approach rescues overcollapse of a disordered protein in canonical protein force fields. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 7975–7984 (2015).

Petrov, D. & Zagrovic, B. Are current atomistic force fields accurate enough to study proteins in crowded environments?. PLOS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003638 (2014).

Horn, H. W. et al. Development of an improved four-site water model for biomolecular simulations: TIP4P-Ew. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 9665–9678 (2004).

Abascal, J. L. F. & Vega, C. A general purpose model for the condensed phases of water: TIP4P/2005. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 234505 (2005).

Piana, S., Donchev, A. G., Robustelli, P. & Shaw, D. E. Water dispersion interactions strongly influence simulated structural properties of disordered protein states. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 5113–5123 (2015).

Izadi, S., Anandakrishnan, R. & Onufriev, A. V. Building water models: a different approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3863–3871 (2014).

Best, R. B., Zheng, W. & Mittal, J. Balanced protein–water interactions improve properties of disordered proteins and non-specific protein association. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 5113–5124 (2014).

Zerze, G. H., Zheng, W., Best, R. B. & Mittal, J. Evolution of all-atom protein force fields to improve local and global properties. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 2227–2234 (2019).

Dewing, S. M., Phan, T. M., Kraft, E. J., Mittal, J. & Showalter, S. A. Acetylation-dependent compaction of the histone H4 tail ensemble. J. Phys. Chem. B 128, 10636–10649 (2024).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 14, 71–73 (2017).

Robustelli, P., Piana, S. & Shaw, D. E. Developing a molecular dynamics force field for both folded and disordered protein states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E4758–E4766 (2018).

Zhou, C.-Y., Jiang, F. & Wu, Y.-D. Residue-specific force field based on protein coil library. RSFF2: modification of AMBER ff99SB. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 1035–1047 (2015).

Wu, H.-N., Jiang, F. & Wu, Y.-D. Significantly improved protein folding thermodynamics using a dispersion-corrected water model and a new residue-specific force field. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 3199–3205 (2017).

Maier, J. A. et al. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713 (2015).

Tian, C. et al. ff19SB: amino-acid-specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 528–552 (2020).

Andrews, B., Long, K. & Urbanc, B. Soluble state of villin headpiece protein as a tool in the assessment of MD force fields. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 6897–6911 (2021).

Shabane, P. S., Izadi, S. & Onufriev, A. V. General purpose water model can improve atomistic simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 2620–2634 (2019).

Yoo, J. & Aksimentiev, A. Improved parameterization of amine–carboxylate and amine–phosphate interactions for molecular dynamics simulations using the CHARMM and AMBER force fields. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 430–443 (2016).

Yoo, J. & Aksimentiev, A. Refined parameterization of nonbonded interactions improves conformational sampling and kinetics of protein folding simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 3812–3818 (2016).

Yoo, J. & Aksimentiev, A. New tricks for old dogs: improving the accuracy of biomolecular force fields by pair-specific corrections to non-bonded interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 8432–8449 (2018).

Sarthak, K., Winogradoff, D., Ge, Y., Myong, S. & Aksimentiev, A. Benchmarking molecular dynamics force fields for all-atom simulations of biological condensates. J. Chem. Theory Comput. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.3c00148 (2023).

Weng, S.-L., Mohanty, P. & Mittal, J. Elucidation of the molecular interaction network underlying full-length FUS conformational transitions and its phase separation using atomistic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 129, 8843–8857 (2025).

Samantray, S., Yin, F., Kav, B. & Strodel, B. Different force fields give rise to different amyloid aggregation pathways in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 6462–6475 (2020).

Abriata, L. A. & Dal Peraro, M. Assessment of transferable forcefields for protein simulations attests improved description of disordered states and secondary structure propensities, and hints at multi-protein systems as the next challenge for optimization. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 2626–2636 (2021).

Piana, S., Robustelli, P., Tan, D., Chen, S. & Shaw, D. E. Development of a force field for the simulation of single-chain proteins and protein–protein complexes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 2494–2507 (2020).

Nerenberg, P. S., Jo, B., So, C., Tripathy, A. & Head-Gordon, T. Optimizing solute–water van Der Waals interactions to reproduce solvation free energies. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 4524–4534 (2012).

Cornilescu, G., Marquardt, J. L., Ottiger, M. & Bax, A. Validation of protein structure from anisotropic carbonyl chemical shifts in a dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 6836–6837 (1998).

Piana, S., Lindorff-Larsen, K. & Shaw, D. E. Atomic-level description of ubiquitin folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5915–5920 (2013).

Lindorff-Larsen, K., Maragakis, P., Piana, S. & Shaw, D. E. Picosecond to millisecond structural dynamics in human ubiquitin. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 8313–8320 (2016).

Kubelka, J., Chiu, T. K., Davies, D. R., Eaton, W. A. & Hofrichter, J. Sub-microsecond protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 359, 546–553 (2006).

Kubelka, J., Henry, E. R., Cellmer, T., Hofrichter, J. & Eaton, W. A. Chemical, physical, and theoretical kinetics of an ultrafast folding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18655–18662 (2008).

Zhou, H.-X. & Pang, X. Electrostatic interactions in protein structure, folding, binding, and condensation. Chem. Rev. 118, 1691–1741 (2018).

Debiec, K. T., Gronenborn, A. M. & Chong, L. T. Evaluating the strength of salt bridges: a comparison of current biomolecular force fields. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 6561–6569 (2014).

Zhang, H., Yin, C., Jiang, Y. & van der Spoel, D. Force field benchmark of amino acids: I. Hydration and diffusion in different water models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 1037–1052 (2018).

Ulmer, T. S., Ramirez, B. E., Delaglio, F. & Bax, A. Evaluation of backbone proton positions and dynamics in a small protein by liquid crystal NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 9179–9191 (2003).

Wlodawer, A., Walter, J., Huber, R. & Sjölin, L. Structure of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor: results of joint neutron and X-ray refinement of crystal form II. J. Mol. Biol. 180, 301–329 (1984).

Diamond, R. Real-space refinement of the structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 82, 371–391 (1974).

Jäger, M. et al. Structure–function–folding relationship in a WW domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10648–10653 (2006).

Best, R. B., Hummer, G. & Eaton, W. A. Native contacts determine protein folding mechanisms in atomistic simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17874–17879 (2013).

Prusty, S., Brüschweiler, R. & Cui, Q. Comparative analysis of polarizable and nonpolarizable CHARMM family force fields for proteins with flexible loops and high charge density. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 65, 8304–8321 (2025).

Bonomi, M. & Parrinello, M. Enhanced sampling in the well-tempered ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 190601 (2010).

Deighan, M., Bonomi, M. & Pfaendtner, J. Efficient simulation of explicitly solvated proteins in the well-tempered ensemble. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2189–2192 (2012).

Soranno, A. et al. Quantifying internal friction in unfolded and intrinsically disordered proteins with single-molecule spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17800–17806 (2012).

Wuttke, R. et al. Temperature-dependent solvation modulates the dimensions of disordered proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5213–5218 (2014).

Sagar, A., Jeffries, C. M., Petoukhov, M. V., Svergun, D. I. & Bernadó, P. Comment on the optimal parameters to derive intrinsically disordered protein conformational ensembles from small-angle X-ray scattering data using the ensemble optimization method. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 2014–2021 (2021).

Koren, G. et al. Intramolecular structural heterogeneity altered by long-range contacts in an intrinsically disordered protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220180120 (2023).

Mohanty, P. et al. A synergy between site-specific and transient interactions drives the phase separation of a disordered, low-complexity domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2305625120 (2023).

Shalongo, W., Dugad, L. & Stellwagen, E. Distribution of helicity within the model peptide acetyl(AAQAA)3amide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 8288–8293 (1994).

Tang, W. S., Fawzi, N. L. & Mittal, J. Refining all-atom protein force fields for polar-rich, prion-like, low-complexity intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 9505–9512 (2020).

Graf, J., Nguyen, P. H., Stock, G. & Schwalbe, H. Structure and dynamics of the homologous series of alanine peptides: a joint molecular dynamics/NMR study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1179–1189 (2007).

Vögeli, B., Ying, J., Grishaev, A. & Bax, A. Limits on variations in protein backbone dynamics from precise measurements of scalar couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9377–9385 (2007).

Case, D. A., Scheurer, C. & Brüschweiler, R. Static and dynamic effects on vicinal scalar J couplings in proteins and peptides: a MD/DFT analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 10390–10397 (2000).

Lindorff-Larsen, K., Best, R. B. & Vendruscolo, M. Interpreting dynamically-averaged scalar couplings in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 32, 273–280 (2005).

Conicella, A. E. et al. TDP-43 α-helical structure tunes liquid–liquid phase separation and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 5883–5894 (2020).

Monahan, Z. et al. Phosphorylation of the FUS low-complexity domain disrupts phase separation, aggregation, and toxicity. EMBO J. 36, 2951–2967 (2017).

Janke, A. M. et al. Lysines in the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain contribute to TAF15 fibril recruitment. Biochemistry 57, 2549–2563 (2018).

Shen, Y. & Bax, A. SPARTA+: a modest improvement in empirical NMR chemical shift prediction by means of an artificial neural network. J. Biomol. NMR 48, 13–22 (2010).

Kabsch, W. & Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 (1983).

Camilloni, C., De Simone, A., Vranken, W. F. & Vendruscolo, M. Determination of secondary structure populations in disordered states of proteins using nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. Biochemistry 51, 2224–2231 (2012).

Buckle, A. M., Schreiber, G. & Fersht, A. R. Protein-protein recognition: crystal structural analysis of a barnase-barstar Complex at 2.0-.ANG. resolution. Biochemistry 33, 8878–8889 (1994).

Read, R. J., Fujinaga, M., Sielecki, A. R. & James, M. N. G. Structure of the complex of Streptomyces Griseus protease B and the third domain of the Turkey ovomucoid inhibitor at 1.8-.ANG. resolution. Biochemistry 22, 4420–4433 (1983).

Wang, J. et al. Structure of a heterophilic adhesion complex between the human CD2 and CD58 (LFA-3) counterreceptors. Cell 97, 791–803 (1999).

Ko, T.-P., Liao, C.-C., Ku, W.-Y., Chak, K.-F. & Yuan, H. S. The crystal structure of the DNase domain of colicin E7 in complex with its inhibitor Im7 protein. Structure 7, 91–102 (1999).

Zhang, Y., Liu, H., Yang, S., Luo, R. & Chen, H.-F. Well-balanced force field ff03CMAP for folded and disordered proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 6769–6780 (2019).

Yu, L., Li, D.-W. & Brüschweiler, R. Balanced amino-acid-specific molecular dynamics force field for the realistic simulation of both folded and disordered proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 1311–1318 (2020).

Her, C. et al. Molecular interactions underlying the phase separation of HP1α: role of phosphorylation, ligand and nucleic acid binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 12702–12722 (2022).

Phan, T. M., Kim, Y. C., Debelouchina, G. T. & Mittal, J. Interplay between charge distribution and DNA in shaping HP1 paralog phase separation and localization. eLife 12, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.90820 (2023).

Mohanty, P., Rizuan, A., Kim, Y. C., Fawzi, N. L. & Mittal, J. A complex network of interdomain interactions underlies the conformational ensemble of monomeric TDP-43 and modulates its phase behavior. Protein Sci. 33, e4891 (2024).

Mohanty, P. et al. Principles governing the phase separation of multidomain proteins. Biochemistry 61, 2443–2455 (2022).

Johnson, C. N. et al. Insights into molecular diversity within the FUS/EWS/TAF15 protein family: unraveling phase separation of the N-terminal low-complexity domain from RNA-binding protein EWS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 8071–8085 (2024).

Virtanen, I. et al. Heterogeneous Dynamics in Partially Disordered Proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 21185–21196 (2020).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015).

Luo, Y. & Roux, B. Simulation of osmotic pressure in concentrated aqueous salt solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 183–189 (2010).

Evans, D. J. & Holian, B. L. The Nose–Hoover thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 4069–4074 (1985).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Shirts, M. R. et al. Lessons learned from comparing molecular dynamics engines on the SAMPL5 dataset. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 31, 147–161 (2017).

Hopkins, C. W., Le Grand, S., Walker, R. C. & Roitberg, A. E. Long-time-step molecular dynamics through hydrogen mass repartitioning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 1864–1874 (2015).