Abstract

Spatiotemporal gating in signal transduction and corresponding activation or inhibition of a biochemical pathway is the hallmark of biological functionality. Herein, through both experimental and computational approaches, we developed a synthetic system to mimic one of the key biological signaling events - local inhibition and distal (long-range) activation (LIDA). The basis of our system lies in the differential diffusivity of – (i) injected dormant activator or pro-activator (Pro-A, urea, fast to diffuse due to non-binding with nanoparticle (NP) in gel matrix) that converts to activator (A, ammonium bicarbonate) via an enzyme (urease) embedded in the hydrogel) and (ii) inhibitor (IN, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), diffusion restricted due to interaction with NP). Here A and IN act as the activator and inhibitor of a base-catalyzed proton transfer reaction in the gel matrix, respectively. The indispensability of ProA to A conversion during diffusion for efficient time-regulated LIDA effect has also been demonstrated. The ability to input spatial gating of pH and reaction activation can potentially be extrapolated to develop neuromorphic self-assembled systems with distal programmability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Differential diffusivity of activators and inhibitors in a signaling system is one of the fundamental aspects for the spatiotemporal regulation of biological processes1,2,3. In 1952, Alan Turing described the importance of reaction-diffusion (RD) phenomenon for pattern formation in biology4. Since then, researchers have realized the importance of RD of biological signaling molecules in processes ranging from embryonic to organ development, NOTCH signaling pathway, localized neuronal response etc.5,6,7,8. In general, pattern formation in biological organisms has been elucidated through the Turing model, where at least two interacting and diffusing species are involved. Here, a short-range activator is autocatalytic along with a long-range inhibitor that suppresses the activation effect, resulting in limitless number of distribution patterns with two species2. In 1960s, Burnett proposed a long-range activator-cum-inhibitor model using Hydra as a model system for demonstrating its distinct head-foot end and regeneration of the head at a different location9. Subsequently in 1972, Gierer and Meinhardt categorically demonstrated different pattern polarity (along with site variability) using activator-inhibitor-based model from a source of different density, gradient and position. Here the inhibitor is faster diffusing species than the activator and initially activator and inhibitor are equally distributed10. To this end, in 1969, Wolpert proposed the seminal concept of the positional information of a cell in a morphogen gradient governs the fate of the embryonic cell during the developmental process (also known as the French flag problem)11,12. Recent reports suggest biological RD phenomenon involving short-range inhibitor and long-range activator in cases like - embryonic development for distinguishing germ layers, retrograde signaling in the nervous system, and organelles inside cells, etc.13,14,15.

Inspired by biological pattern formation, scientists are also inclined in developing reaction-diffusion based models and systems, due to their manifold applications in diverse areas, ranging from - understanding biological morphogenesis to disease spread and to the designing of dynamic and spatially resolved (bio)materials for cell growth or sensors16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Usually, a hydrogel matrix is used for achieving different patterns via the differential self-assembly ability or diffusion of different components26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Employing original and modified Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) reaction, researchers developed different kinds of Turing-like patterns in gel matrix, Liesegang pattern using nanoparticles, controlled one-dimensional gradient pattern of supramolecular assembly etc.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Additionally, diverse complex (bio)chemical reaction network-based RD systems were developed to mimic biological processes and to generate programmable or patterned soft matters and actuators39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. A recent report demonstrated an artificial developmental process by showing a French flag pattern-based colloidal aggregation to autonomously structure a soft material via DNA-based bistable reaction networks47.

In many cases, the addition of templating agent results in localized assembly by attracting a diffusive current of non-assembled molecules from surroundings48,49,50,51. This process eventually enhanced the formation of supramolecular assembly as well as associated properties like – signal generation and catalysis. In general, the desired assembly or associated enhancement in functionality resulting from RD processes takes place locally i.e. at the source point of chemical or energy input48,49,50. However, synthetic systems with short range inhibitor and long-range activator (where the desired functionality will be activated far from source input) are not reported so far to the best of our knowledge. Only in one instance, it has been shown that local addition of high concentration of catalytic inhibitor can enhance the activity at distant place after diffusion as the inhibitor acts as an activator at low concentration52. Although this is an elegant system, it is low in complexity and is based on only one diffusing species, whereas biological system specifically uses multiple reacting and diffusing species. It is worth mentioning that creating a synthetic RD system with local inhibition and distal activation (LIDA) will benefit the repertoire of synthetic systems that mimic natural spatiotemporal signaling pathways which possess precise temporal and positional information. Such a system might also have potential in the bottom-up development of complex chemical synthetic system with neuromorphic behavior. Therefore, the realization of complex chemical RD-based systems with spatiotemporally correlated output signals as a function of input information is one of the essential requirements for mimicking neuromorphic behavior in synthetic chemical systems53,54. This would be of importance to the development of complex pattern-based recognition systems, meta-gels, dynamic soft materials for diverse material and bioengineering applications55.

In this work, we develop a chemoenzymatic reaction-diffusion-based synthetic system to exhibit LIDA effect which is an important aspect of biological signal transmission. Using a combination of experimental and computational approaches, we demonstrate this LIDA effect in a hydrogel by injecting urea and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) at the center of the gel matrix. The experimental set up and detailed discussions has been given in Fig. 1 and in subsequent section. We show a base catalyzed reaction is activated by a combination of faster diffusion of urea and product of urease reaction at the distant zone from the injection center. Also, the reaction is locally suppressed by slow diffusion of ATP (due to binding with gold nanoparticles in the gel matrix). We experimentally demonstrated that reaction activation can be spatiotemporally gated by changing the amount of injected urea and ATP ratio. We also develop a computational model for the validation of the experimental results and a general platform (with varied enzymatic catalysis, reaction rates and diffusion parameters of the components) for future development of such systems.

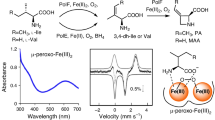

a Reaction scheme with involved species and b reaction-diffusion event after injection of ProA and IN at a point. Here, distant zone becomes basic in pH due to enzymatic conversion of ProA to A, resulting in activation of Kemp Elimination reaction (i.e., conversion of NBI (R) to CNP (P)). Due to the presence of acidic inhibitor in the nearby zone, the reaction is suppressed. Slower diffusion of IN in the gel is due to binding with nanoparticles embedded in gel. c Schematic of the reaction set up with components (urea as ProA and ATP as IN) and reaction schemes. At the empty circular zone (5 mm diameter) aqueous solution of (ATP + urea) or (ATP + NH4HCO3) were added and allowed to diffuse into the agarose gel matrix (0.75 wt%). Experiment with the addition of (ATP as IN + NH4HCO3 as A) has been done as control experiment, to check the direct effect of A + IN. Blue and red arrow indices faster and slower diffusion of urea and ATP through gel matrix, due to non-binding and binding of GNP, respectively. The gel is embedded with CTAB-capped GNP (0.2 nM), urease enzyme (15 nM) and NBI (0.5 mM).

Results and discussions

Designing of the experimental framework

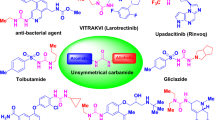

Our chemoenzymatic RD system is based on a catalytic hydrogel matrix with a reaction-diffusion system (Fig. 1). As mentioned in the preceding section, we aimed in activating a reaction spatially distant from the region of addition of inputs. We chose a base-catalyzed proton-transfer ring-opening reaction (also known as Kemp Elimination (KE) reaction) for this purpose56,57,58,59. The substrate for KE reaction 5-nitrobenzisoxazole (NBI, denoted as R in the manuscript) was evenly distributed in the agarose gel matrix. This R is converted to 2-cyanonitrophenol (CNP, denoted as P) in presence of a base and the reaction gets catalyzed by cationic gold nanoparticle (GNP)56,57. Therefore, the hydrogel was also embedded with GNP. Notably, in ultrapure water (with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm at 25 °C), GNP does not catalyze the conversion of R to P. An enzyme, urease (E), is also present in the gel matrix that does not react with R or GNP. E can convert a neutral molecule, urea (dormant activator or pro-activator, ProA) to a base, ammonium bicarbonate (activator, A). We named urea and ammonium bicarbonate as ProA and A, respectively as A can activate the conversion of R to P and A formed only after the enzymatic action over ProA37. As we aimed to develop a LIDA-based system, we chose an anionic molecule, ATP as inhibitor (IN) of the KE reaction. We locally injected a mixture of ProA (urea) and IN (ATP) to achieve our desired system with local or short-range inhibition and distal or long-range activation.

The reasons behind choosing ATP as IN and urea as ProA are following – (i) due to acidic nature of ATP, it is known to suppress KE reaction, and thereby, it acts as a very good inhibitor for this process. Secondly, for local inhibition, IN needs to be slow to diffuse. In our case, ATP is anionic and has a great ability to bind with cationic GNP (already embedded in gel matrix), therefore, due to binding, diffusion of IN will be restricted through the gel matrix. (ii) We chose urea as ProA. As it is neutral, it does not bind to GNP and diffuses faster than IN. Therefore, upon injecting a mixture of ProA and IN, enzymatic ProA to A conversion will take place even in a zone devoid of IN. Thus, in principle, R to P conversion will take place far away from the zone of injection of ProA and IN. However, there is always the question of whether adding A (instead of ProA) and IN would provide the same effect or not. To address this issue, we also performed control experiments both experimentally and theoretically to demonstrate that enzymatic conversion of ProA to A during diffusion is a pre-requisite for developing such a system in a well-defined manner.

For experimental verification of the above-mentioned hypothesis, we designed our system as shown in Figs. 1c and 2a. In a petri dish, agarose gel casting was performed by keeping the center with 5 mm diameter vacant. The height of the gel was 3 mm. In the vacant zone, a solution of ATP + urea or ATP + NH4HCO3 was added and allowed to diffuse through the gel matrix. The gel is also embedded with cationic CTAB-capped gold nanoparticles (GNP), urease (E) and NBI (R). We used 0.75 wt% agarose gel for all our experiments for the following reasons (Supplementary Fig. 1). We found at higher concentration of agarose gel (1 wt %) GNP gets aggregated which can decrease the NBI to CNP reaction rate and alter the diffusion behavior of ATP. The aggregation was checked by noting the ratio of absorbances A620/A520, where an increase in the ratio indicates more aggregated AuNPs60. Higher agarose concentrations create a gel with a smaller mesh size, which acts as a physical barrier to nanoparticle movement, resulting enhanced interparticle friction and clustering of nanoparticles61. In contrary, at lower agarose concentration (0.5 wt%), the time taken to complete gel formation (after dissolving agarose at 110 °C) was ~25–30 min, resulting in some background conversion of NBI to CNP, prior to the addition of any reagent at the center. Therefore, to balance both issues, we used 0.75 wt% agarose gel for our study, where GNP aggregation was negligible and gel formation was fast (~5 min). We would like to mention here that only after complete solid-like gel formation, the solution of ATP + urea or ATP + NH4HCO3 at the center was added. Additionally, while preparing gel, we did not use any salt solution, as salt like NaCl can result in GNP aggregation and inhibit the base-catalyzed NBI to CNP reaction (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Interplay of urea and ATP to govern final Product (P) formation kinetics within the chemoenzymatic reaction systems in water

Before proceeding to the experiment with gel matrix, we analyzed the system in aqueous solution (milli Q water). At first, we checked the binding of ATP and NH4HCO3 and non-binding of urea with cationic GNP surface via zeta potential measurement (Supplementary Fig. 3). Then we checked in the presence of urease, addition of urea indeed results in conversion of NBI to CNP and the time of reaction outcome depends on the amount of urea (Supplementary Fig. 4). In absence of urease, no reaction occurs, and reaction can get activated in presence of NH4HCO3 (Supplementary Fig. 5). It is worth mentioning that in our previous studies, we already demonstrated the catalytic ability of GNP for this KE reaction in urea-urease system33. We also showed that with increasing ATP content in the reaction system with urea-urease and NBI, the KE reaction rate can be significantly slowed down (Supplementary Fig. 4). For example, only 0.2 mM ATP can slow down the NBI to CNP conversion rate by 50% when 2 mM urea was used in presence of 15 nM urease. In a similar condition, upon checking the inhibitory effect of a simple salt NaCl, we found 10–15 mM NaCl is needed to decrease the production of CNP by 50% (Supplementary Fig. 2). In this case, weakly basic chloride ion can act as a competitor of basic HCO3- ion for binding with the cationic GNP surface to hinder the conversion of NBI to CNP. Using a pH probe, bromothymol blue (BTB), we established that with increasing ATP, the time required for acidic to basic transformation was increased, resulting in a delay of the base-catalyzed proton transfer reaction (Supplementary Fig. 6)56,62.

Spatiotemporal evolution of the final product due to the RD process in the gel matrix

Now, for the gel experiment, we measured the formation of CNP at 8 different zones, each separated by 1 mm in a plate reader (please see experimental procedure in the methods section for details). First, we injected 40 μl volume of aqueous solution containing 50 mM urea and 5 mM ATP at the center and allowed it to diffuse through the hydrogel matrix (Figs. 1c and 2a). We then monitored the evolution of reaction product, P by following the absorbance at 380 nm wavelength over time at different points (Fig. 2b, c). Upon injecting 50 mM urea + 5 mM ATP at the center, we were pleased to observe that the formation of P did not happen near the injection center (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 7). Indeed, in this case, the maximum product was found 5 mm away from the center between 2 h to 5 h (Fig. 2e). For the initial 60 and 90 min data, we observed that the maximum product formation was taking place at zone 4 (4 mm away from center). Interestingly, while injecting 40 μl of 50 mM NH4HCO3 (product formed after urea-urease reaction) + 5 mM ATP at the center, the maximum reaction product formed in the very beginning at zone 3 (up to 60 min), and then the maximum product always formed at zone 2 (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 8). Although in this case, the reaction rate was very high and the amount of product was almost equally distributed from zone 1 to zone 5, 6 and 8, after 1, 2 and 4 h, respectively, suggesting the difference in concentration is negligible and the product mostly formed near the injection center. We also performed an additional experiment with lower urea (25 mM) but with similar ATP of 5 mM. In this case, we found the maximum product forming zone was further away by 1 mm up to 90 min in comparison to 50 mM urea + 5 mM ATP case (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 9). At both 1 and 1.5 h, the maximum product formation was found at zone 5 which was maintained up to 5 h. Again, at fixed ATP (2.5 mM), and decreasing urea from 25 to 10 mM, the maximum product formation zone moved further away at zone 5, compared to zone 4 after 3 h (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). These experiments clearly suggest the importance of injecting urea, instead of NH4HCO3 and enzymatic conversion of urea to NH4HCO3 during diffusion plays the key role in generating distant reaction product forming zone. Also decreasing the amount of urea injected at a fixed ATP concentration, resulted in the product formation zone moving further away from reaction center. However, at very low urea (10 mM), the amount of formed P was too low. We also performed control experiments without either urease or GNP or both in the gel matrix. In all these cases, the product formation was too low, indicating the requirement of both E and GNP for the reaction conversion (Supplementary Figs. 12–14). Next, we also checked the effect of addition of only urea in the system having GNP and urease in the gel matrix (Supplementary Fig. 15). Here also, the product formed maximally at zone 1 and diffused to other distant zones with time, showing the importance of ATP (IN) and conversion of urea (ProA) to basic ammonium ions (IN) during diffusion through gel matrix for LIDA-effect.

a Snapshot of the experimental petridish with dimension of the experimentally measured area (square with solid line) and hole with dashed square. b Schematic representation of the points taken to average out the value of each zone (shown by the red highlighted parts). c A snapshot of the experimental data inside plate reader to show the hole and other experimental zone. Measurements were taken in all directions. To avoid the error due to angular contribution, the average values of the four points (as shown in cross pattern in panel b) at the same distance were calculated and extrapolated to represent the entire circumference as circle (indicated by showing dotted circle to represent zone 1 (Z1), zone 4 (Z4) and zone 8 (Z8) in panel c). d Spatiotemporal pattern of product (CNP) formation when 40 µl of aqueous solution of 5 mM ATP and 50 mM urea (top panel) and 5 mM ATP + 50 mM NH4HCO3 (bottom panel) were injected at the central zone. The color map showed the CNP concentration at each zone. Herein, concentrations above 400 µM were shown as deep red and below 100 µM as deep blue. e The maximum product-forming zone away from the source at different time points was plotted for the injection of urea (25 mM) + ATP (5 mM), urea (50 mM) + ATP (5 mM), and NH4HCO3 (50 mM) + ATP (5 mM). The color of each symbol depicts the concentration range as shown in the color map (below 400 µM as deep blue and 500 µM as deep red). f Maximum product forming zone away from the source at different time points was plotted for injection of urea (25 mM) + ATP (2.5 mM) and urea (10 mM) + ATP (2.5 mM). The color of each symbol depicts the concentration range as shown in the color map. Data are presented as mean ± SD (where n = 8). Source data are provided as a source data file.

Spatiotemporal change in pH of the LIDA-based chemoenzymatic systems

The results discussed in the previous paragraph suggest that enzymatic conversion of ProA to A during diffusion is the essential factor for developing LIDA-based systems. Next, we were curious to find the reason behind this phenomenon. As KE is a base-catalyzed reaction, R to P conversion should occur at high pH. Therefore, we were interested to find out the spatiotemporal evolution of pH in the system after injection of 50 mM urea and 5 mM ATP. For this, bromothymol blue (BTB) dye was incorporated in the gel instead of NBI, along with GNP and E (Fig. 3a). At first, we calibrated the gel system at 620 nm wavelength with BTB dye using known pH value (Supplementary Fig. 16). It is worth mentioning that absorbance value at 620 nm increases with increasing pH. Interestingly, we find that the initial zones (up to 2 mm) near the injection center remain acidic (below pH 6) for about 60 min, whereas pH of zone 3 and 5, at 60 min were 7.2 and 8.1, respectively (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Figs. 17, 18). It clearly suggests that initially the pH remains low at the injection center but was higher at zone 4 and 5. Even after 180 min, we found pH of zone 1 was close to 7, whereas the value was 8 or higher for zone 4 onwards. As pH of the distant zone becomes higher quickly, the reaction starts at distal zones from the injection center (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 17). This also suggests that acidic ATP remains close to injection center, whereas urea moved faster and converted to basic NH4HCO3, even at distant zones to activate the KE reaction.

a Schematic of the reaction set up with components as described in Fig. 1c. In this case, pH probe Bromothymol blue (0.02 mM) was added in the gel instead of NBI. At the empty circular zone (5 mm diameter) aqueous solution of (ATP + urea) was added and allowed to diffuse to the agarose gel matrix (0.75 wt%). b A snapshot of petridish taken after 60 min, showing the initial zone is acidic (yellow color) and outer region is basic (blue color). c Spatiotemporal pattern of pH in the gel matrix with time when 40 µl of aqueous solution of 5 mM ATP and 50 mM urea was injected in the central zone. Blue indicates pH of 8 or higher and red indicates pH lower than 6. The pH of the whole gel before injection was around 5.6 as it was made with mQ water (which is slightly acidic due to dissolved CO2). d pH (blue points, left sided Y-axis) and product formation (orange points, right-sided Y-axis) with time at zone 1, zone 3 and zone 5. Data are presented as mean ± SD (where n = 8). Source data are provided as a source data file.

Numerical simulation of the LIDA-based model systems with different reaction and diffusion parameters

After establishing the system experimentally, we were interested to explore the spatiotemporal emergence of the reaction product at different diffusion parameters, activation and inhibition constant by developing a model system. This will be of importance for further understanding the present system and how to build similar LIDA-type synthetic system, with chemical components of different diffusivity and catalytic properties. This model simulates a two-dimensional reaction-diffusion system involving six chemical species undergoing transport and/or enzymatic reactions. The system is defined in polar coordinates \((r,\,\theta )\) over a circular domain, and it accounts for both radial and angular diffusion (Fig. 4). E and R are embedded in a circular reaction matrix. ProA and IN are injected at the center and allowed to diffuse and react. We also performed control experiments with only A instead of ProA to see the difference in spatiotemporal reaction pattern.

a Scheme of the reactions used for modeling. Here similar dimensions of two-dimensional circular disc (8 mm diameter) as used in experiment were chosen. b Spatiotemporal distribution of reaction product (P) at different kIN/kA and different diffusion coefficient ratios of ProA, IN and A when ProA (50 mM) and IN (5 mM) are injected at the center (left) and A (50 mM) and IN (5 mM) are injected at the center (right). The maximum product concentration (normalized) obtained in both ProA + IN and A + IN cases are given in Supplementary Table 1. Product distribution when kIN/kA = 103, and DProA:DIN:DA = 40: 1: 1, 40: 2: 2, 40: 5: 5 and 40: 8: 8 (where DProA = 4 × 10−10 m2/s) for c ProA + IN injection and d A + IN injection at the center at 150 min. Notably, product concentration in the case of A + IN injection is higher than ProA + IN injection. For (b–d), the concentration of product was normalized with respect to the maximum product concentration obtained for the case of kIN/kA = 103 and DProA:DIN:DA = 40:2:2 at 150 min.

The governing reaction-diffusion is described by partial differential equations (PDE) of the form:

Where \(i\) is the appropriate chemical species ProA, A, I or P. \({C}_{i}\) is the concentration of the chemical species \(i\). \({D}_{i}\) is the diffusion coefficient. \({R}_{i}(C)\) represents the reaction term. A constant concentration of enzyme (E) in the matrix is assumed.

The reaction terms for: ProA → A (Michaelis-Menten equation) and R → P conversions are given in Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively.

Where \({R}_{0}\) is the initial concentration of the reactant, NBI.

In Eq. (4), kA and kIN are rate constant of A-induced activation and IN-mediated inhibition (see supplementary information for detailed derivation of Eq. (4)). Central Finite Difference Approximations are used for spatial derivatives. Neumann boundary condition (no-flux) is imposed at the center and domain boundary. A circular disc of 8 mm diameter has been chosen to follow the reaction-diffusion phenomenon, and we followed the RD system until 150 min. At first, we checked the spatiotemporal emergence of the final product P in different ratio of kIN and kA (kIN / kA = 1, 103 and 106) while adding a mixture of 50 mM ProA and 5 mM IN at the center of the circular disc. Additionally, we checked 4 different diffusion ratio of ProA, A and IN (DProA: DIN: DA = 40: 1: 1; 40: 2: 2; 40: 5: 5 and 40: 8: 8) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 19–30). Here, we assumed DProA = 4 × 10−10 m2/s (considering diffusion co-efficient of urea) and kcat/KM = 3000 mM−1s−1 (kcat = 104 s−1, KM = 3.3 mM) for enzyme urease towards substrate urea63. For screening of the simulation parameters we assume both IN and A has similar diffusion co-efficient as both can bind with GNP. The diameter of GNP is around 25 nm; therefore, we assumed that bound IN and A would be of similar diffusion co-efficient with a much lower value than ProA. Additionally, we did not consider any diffusivity of P. Simultaneously, we checked the scenario when instead of ProA, we added 50 mM A (directly added without allowing it to form through enzymatic reaction) and 5 mM IN with similar kinetic and diffusion parameters (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 31–42). From the theoretical plot, we can observe a trade-off between diffusion ratio and kIN/kA. In general, for kIN/kA of 103 a clear LIDA effect was observed at all ratios of diffusion coefficients studied in this work. However, the amount of P steadily decreased with increasing diffusion of IN. After 150 min, the highest LIDA was observed in the case of kIN/kA of 106, with DProA: DIN: DA = 40: 2: 2, although the product amount was lower than the case when kIN/kA was 103. Similarly, the system will be effective for DProA: DIN: DA = 40: 5: 5 or 40: 8: 8 cases quite efficiently when kIN/kA equals 103, but not with kIN/kA of 106. In fact, we were pleased to observe while injecting only A = 50 mM and IN = 5 mM at the center, and DIN = DA (1:1), the product always formed close to the injection center and the amount of product was higher than the case when (ProA + IN) was injected (Fig. 4b–d, Supplementary Table 1).

After analyzing the above data, we fixed DProA: DIN: DA = 40: 2: 2 and kIN/kA to 103 to explore the spatiotemporal emergent behavior of P with different concentration ratios of ProA and IN injection at the center. This model output is comparable to our observed experimental result (Supplementary Figs. 43, 44). We fixed the amount of IN to 5 mM and decreased the amount of ProA to 25 and 10 mM. In this case we found that, with low ProA (10 mM), maximum P emerged at a distant zone (3 mm away from the center) beforehand (in terms of time) than in the other two cases (Supplementary Fig. 45). In a similar manner we fixed the amount of ProA to 50 mM and found that, with increasing IN, maximum P was formed at a distant zone at earlier time point compared to low IN (Supplementary Fig. 46). Lower ProA or higher IN results in enhanced inhibition, therefore, maximum product was found at more distant zone. However, with high IN or low ProA, the amount of product is low and in some cases, negligible. Both simulations are similar to our experimentally observed scenario described at Fig. 2f to a considerable extent. Again, while using only (A + IN) injection, the maximum product forming zone remains same irrespective of the concentration and no concentration effect over spatiotemporal variation was observed (Supplementary Fig. 47).

At this point, we asked ourselves, in the development of LIDA type system, what is the benefit of including ProA to A conversion and higher diffusion co-efficient of ProA compared to IN? In fact, one might think that this system could be developed using a faster diffusing A and slower diffusing IN. We tested this by simulating the A + IN system, assuming DA to be greater than DIN. The model simulated conditions when DIN:DA = 1:40, 2:40, 5:40 and 8:40 at kIN/kA = 1, 103 and 106, with the amount of A and IN being 50 mM and 5 mM respectively (fixed DA = 4 × 10−10 m2/s) (Supplementary Figs. 48–59). The resulting plot of P concentration over time shows that P formation was concentrated in the central zone, near the injection point at all diffusion coefficient ratios at kIN/kA = 1. At kIN/kA = 103, maximum concentration of P was found at zone 3 at all ratios of DIN:DA. P formation in the case of kIN/kA = 106 was maximum at distal zones (zone 5, 6), although the maximum concentration of P was lowest here, out of the three kIN/kA cases tested (Supplementary Fig. 60). With faster diffusion of IN, the zone where maximum P is observed moves further away from the site of injection. And higher kIN/kA value shows stronger inhibition in the central zones. Although LIDA can be observed in this case, the addition of ProA to A reaction gives greater spatiotemporal control over the system, even after considering ProA converted A has similar diffusivity to IN. To prove this, we compared these results with the earlier case of ProA + IN at various ratios of diffusion coefficients and kIN/kA (Supplementary Fig. 61). While the concentration of P is lower in the case of ProA + IN, the zone of maximum P formation is consistently farther away than the case with A + IN at least by 1 mm in each case. This is applicable at all ratios of diffusion coefficients and kIN/kA. We also compared P output pattern for two different situations, DProA: DIN: DA = 40:2:5 and 40:2:20 with DIN: DA = 2:5 and 2:20 cases (Supplementary Fig. 62). Here we found that addition of ProA results shifting of maximum P formation zone by 1–2 mm distance compared to A + IN case with different spatiotemporal manner. Overall, the results show the LIDA effect is even more effective while using ProA and its conversion to A during diffusion, even when A has higher diffusivity than IN.

One other advantage of having ProA is that temporal control can be achieved by modifying the reaction parameters of ProA to A. We simulated cases where we modified the kcat/kM ratio to increase or decrease by 10- and 100-fold (at a range of five orders of magnitudes from 30 to 300000 mM−1s−1) (Supplementary Figs. 63–68). The point of time when the desired concentration of P is observed in the system is tracked. The results show that temporal control of this RD system can be achieved by modifying reaction kinetics of ProA to A reaction. This temporal control would not be possible in a simple system with only two diffusing species as shown in A + IN case and therefore, validating the necessity of reaction-diffusion for more distinct LIDA with manifold spatiotemporal diversity.

Numerical simulation considering pH sensitivity of urease reactivity

So far, we have not considered the pH sensitivity of urease reactivity. Urease activity followed a bell-shaped curve where at pH 7 enzyme showed its highest activity. In our experiment, we found that the initial zones remain acidic due to presence of ATP, whereas outer zone has higher pH (data demonstrated in Fig. 3). Indeed, upon measuring ammonia production rate during urease-urea reaction, we also found that with increasing ATP concentration urease reactivity decreased (Supplementary Table S3). Here pH of the system is also decreasing with increasing ATP.

For modeling pH-dependent urease activity, a Gaussian curve centered at pH 7 (enzyme’s optimal pH) was used as previously shown by Straube et al.64. The experimentally measured pH values at each of the 8 zones over time are associated with the equivalent radial zones of the model at the specified time points (Supplementary Table 3). Zone 0, representing the central cavity is assigned a pH value of 3.7 to represent its acidic nature due to presence of 5 mM ATP. For each zone, the pH data is interpolated over the experimental time range using the ‘interp1d’ function of Python, so that the local pH can be looked up at any simulation moment for each radial position.

The pH in each zone determines the enzyme activity factor (activity_factor variable in code ProA+I – with pH dependence.py), a scalar between 0 and 1. This value then multiplies the catalytic reaction term (reaction_AB variable in the code) in the model equations, thus controlling how efficiently the substrate is converted into the product based on the local pH. Therefore, this model accurately captures the spatial and temporal progression of the reaction system, considering the effect of pH on urease activity. In this case we also considered diffusion of P which is similar to IN and A (DProA: DIN: DA: DP = 40: 2: 2: 2). The simulation result is given in Supplementary Fig. 69. In this case also a clear LIDA effect was observed for ProA + IN case compared to A + IN injected scenario with a factor of 1–2 mm.

In summary, firstly, we experimentally demonstrated a complex chemoenzymatic system to gain control over catalysis at a spatially distant zone in a time-dependent manner. This reaction-diffusion system primarily relied on supramolecular interaction-based diffusion control and both enzymatic and nanoparticle surface-mediated catalysis. This demonstration will be important in the future development of chemical systems that aim to regulate the onset of chemical reactions both spatially and temporally65,66,67,68,69,70. Notably, our approach is entirely different for modulating chemical reactions at the far-off site from the injection point. We also designed a theoretical model to rationalize the experimental facts. We further analyzed the benefits of injecting (dormant activator + inhibitor) together rather than (activator + inhibitor) both in terms of gaining efficient spatial gating of the reaction activation zone from the injection center and temporal control via tuning the enzymatic rate of conversion of activator from dormant activator during diffusion. Overall, pH enhancement and corresponding reaction activation region in the gel matrix can be spatiotemporally gated by the enzymatic conversion rate of ProA to A and initial source concentration of ProA and IN. We believe both experimental and theoretical data presented in this manuscript will be important for the advancement of synthetic reaction-diffusion systems to achieve spatiotemporally diverse chemical signaling pathways via modulating chemical inputs, their interaction parameters and directions of reaction propagation ability with surrounding environmental precursors (for example in presence of ions)71,72,73. One can also envision the utility of this approach from the triggering of spatially distant self-assembly and positional information based chemical events akin to artificial developmental program for the construction of more complex chemical neural networks47,74.

Methods

Materials

All commercially available reagents were procured and used without any further purification. Ascorbic acid, Bromothymol Blue, Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide, Sodium Borohydride, Urea, and Urease (UR) were purchased from Sisco Research Laboratory (SRL), India. Adenosine Triphosphate Disodium Salt, Gold (III) Chloride (HAuCl4.3H2O), 1,2-Benzisoxazole, and Sephadex G-25 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Agarose powder was purchased from Himedia.

Synthesis and enzyme activity protocols

For performing the Kemp Elimination reaction, the substrate 5-nitrobenzisoxazole (NBI) was synthesized by nitration of 1,2-benzisoxazole and its product 2-cyano-4-nitrophenol (CNP) was synthesized by base hydrolysis of NBI by following the previously reported procedure as discussed below58,75.

NBI synthesis: 0.4 g of 1,2-Benzisoxazole was dissolved in 5 ml concentrated H2SO4 at room temperature. After slowly adding 0.5 ml of a mixture of conc. HNO3 (0.5 ml) and conc. H2SO4 (0.2 ml) to the above solution, it was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The mixture was then slowly poured into a 20 ml ice-water mixture, followed by stirring for 10 min. The white precipitate obtained was filtered, washed with cold ethanol and the solvent was dried under a high vacuum. The product was recrystallized in absolute ethanol and a white, crystalline solid was obtained. Yield: 80%.

CNP synthesis: 3 ml of 2 M NaOH were added to a solution containing 0.1 g of 5-nitrobenzisoxazole in 2 ml ethanol and 1 ml water, and the mixture was left to stand for 10 min. Then in order to raise the mixture’s pH to 1, HCl was gradually added. Dichloromethane was used to extract the solution, and a vacuum was used to evaporate the solvent. A bright yellow solid was obtained by air-drying the product. Yield: 70%.

For calculating CNP concentration, in aqueous solution after UV-vis kinetics, molar extinction co-efficient value of 16,000 M−1cm−1 was considered57,58.

Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) were synthesized using the seed growth method as described in previously reported literature56. Briefly, 3.75 ml of 100 mM CTAB solution was mixed with 0.052 ml of 24 mM HAuCl4.4H2O to create a seed solution. This was followed by the addition of 1.2 ml of freshly made 25 mM ice-cold sodium borohydride solution, which produced a brown solution that showed the development of gold seeds. For the growth solution, 6.25 ml of 4.0 mM HAuCl4.4H2O solution was mixed with 10 ml of 100 mM CTAB solution. Next, 7.5 ml of 100 mM L-ascorbic acid was added, and the mixture was gently shaken until it became colorless. After adding 62.5 µl of seed solution to the growth solution and vigorously stirring for 20 s, the creation of gold nanoparticles is indicated by the appearance of red. Finally, the resulting solution was left alone for 24 h at room temperature. For further purification it was then passed through a Sephadex G-25 column, containing 0.5 g of Sephadex G-25 swelled in Milli-Q water.

Hydrodynamic diameters (Dh) and zeta potentials of the GNP were measured using Horiba Scientific NanoParticle Observer (SZ-100V2).

Urease activity was measured experimentally using the salicylate-hypochlorite method as discussed in earlier literature76. For the urea-urease (UU) reaction, 50 mM urea and 15 nM of urease were used. 20 µl of UU reaction solution at different time points (t = 0, 5, 10 and 15 min) was added to sodium salicylate, sodium hypochlorite and trisodium phosphate with the final concentration of 250 mM, 50 mM and 100 mM respectively in a sequential manner. The final volume of the solution was 500 µl. This solution was heated at 50 °C for 1 hour after which the spectrum was recorded. A calibration curve was made by plotting absorbance at 640 nm against concentration (50, 100, 250, 500, 750 and 1000 µM) of ammonium bicarbonate as standard. From this plot, the concentration of the ammonia product from UU reaction was determined. Please see Supplementary Table 3 for the data.

Theoretical simulation

The theoretical simulations were modeled using ‘solve_ivp’ function of SciPy library in Python. The detailed equations are given in the supplementary information. The Github link for codes used to perform the simulation has been mentioned in ‘code availability’ section.

For modeling pH-dependent urease activity, a Gaussian curve centered at pH 7 (enzyme’s optimal pH) was used as previously shown by Straube et al.64.

The preparation procedure of hydrogel matrix for reaction-diffusion study

22.5 mg agarose powder was dissolved in 3 ml of milliQ water by heating at 110 °C in a heating block. Then, the dissolved agarose gel was poured into a petri dish with a diameter of 35 mm by placing a cylindrical tube with a diameter of 5 mm at the center of the petri dish and was allowed to cool down at room temperature. This allowed the dissolved agarose powder to polymerize into a rigid yet porous hydrogel matrix. For preparing the GNP amalgamated agarose hydrogel, GNP was added to the dissolved agarose solution (by cooling it to around 55 °C) before pouring it into the petri dish. Hydrogels containing GNP + NBI, GNP + NBI + UR, GNP + BTB, GNP + BTB + UR, NBI + UR, and BTB + UR were synthesized following a similar procedure by keeping the final concentrations of GNP, NBI, UR, and BTB at 200 pM, 0.5 mM, 15 nM, and 30 µM, respectively.

Measurement of the spatiotemporal evolution of pH and KE reaction

To measure the Kemp elimination reaction and pH change in different zones in the hydrogel, the as-prepared hydrogel was placed inside a PolarStar Omega plate reader. Then, a 40 µl volume of ProA (urea), IN (ATP), or a mixture of IN + ProA (in different ratios), or a mixture of IN + A was added into the hole at the center of the agarose gel, and absorbance values at various zones of hydrogel were recorded at different interval of time. For the Kemp elimination reaction, absorbance values were recorded at 380 nm wavelength, whereas for pH change, absorbance values were recorded at 620 nm with matrix scanning (well scanning) mode, keeping the scan matrix dimension 23 × 23, scan width 23 mm. Then, for convenience, four points from each zone (highlighted with red color in Fig. 2b) were taken as the average value for the respective zone. All the experiments were performed twice, and the average value of 2 measurements for each zone was plotted in circular form as shown in Fig. 2a of the main manuscript. Here, each zone is separated by 1 mm, and the outermost 1 mm was excluded to avoid the boundary effect. All the experimental data are averages of 3 experiments. The absorbance value coming from only gel without CNP was subtracted in each case. For converting absorbance to CNP concentration, a calibration plot with known CNP-containing agarose gel (embedded with GNP and urease) was conducted (Supplementary Fig. 70). For pH determination, the calibration curve given at Supplementary Fig. 16 was used. Two independent experiments were performed in each case. Therefore, 8 datapoints were used to calculate the average KE product formation or pH value.

For theoretical data, the concentration of product was normalized with respect to the maximum product concentration obtained for the case of kIN/kA = 103 and DProA:DIN:DA = 40:2:2 at 150 min in the entire manuscript including supplementary information (Fig. 4c).

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main article and in the supplementary information. The data is available from the corresponding author on request. Source data is provided with the manuscript. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The Python code used in this manuscript have been deposited in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/niranjani04/A-Chemoenzymatic-Reaction-Diffusion-System-with-Local-Inhibition-and-Distal-Activation77.

References

Müller, P. et al. Differential diffusivity of Nodal and Lefty underlies a reaction-diffusion patterning system. Science 336, 721–724 (2012).

Kondo, S. & Miura, T. Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. Science 329, 1616–1620 (2010).

Kholodenko, B. N. Cell-signaling dynamics in time and space. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 165–176 (2006).

Turing, A. M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 237, 37–72 (1952).

Green, J. B. A. & Sharpe, J. Positional information and reaction-diffusion: two big ideas in developmental biology combine. Development 142, 1203–1211 (2015).

Sato, M., Yasugi, T., Minami, Y., Miura, T. & Nagayama, M. Notch-mediated lateral inhibition regulates proneural wave propagation when combined with EGF-mediated reaction diffusion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E5153–E5162 (2016).

Sjöqvist, M. & Andersson, E. R. Do as I say, Not(ch) as I do: lateral control of cell fate. Dev. Biol. 447, 58–70 (2019).

Rusakov, D. A., Savtchenko, L. P., Zheng, K. & Henley, J. M. Shaping the synaptic signal: molecular mobility inside and outside the cleft. Trends Neurosci. 34, 359–369 (2011).

Burnett, A. L. A model of growth and cell differentiation in hydra. Am. Naturalist 100, 165–189 (1966).

Gierer, A. & Meinhardt, H. A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik 12, 30–39 (1972).

Wolpert, L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J. Theor. Biol. 25, 1–47 (1969).

Sharpe, J. Wolpert’s French Flag: what’s the problem?. Development 146, dev185967 (2019).

van Boxtel, A. L., Economou, A. D., Heliot, C. & Hill, C. S. Long-range signaling activation and local inhibition separate the mesoderm and endoderm lineages. Dev. Cell 44, 179–191.e5 (2018).

Kleine, T. & Leister, D. Retrograde signaling: organelles go networking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1313–1325 (2016).

Ibáñez, C. F. Message in a bottle: long-range retrograde signaling in the nervous system. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 519–528 (2007).

Soh, S., Byrska, M., Kandere-Grzybowska, K. & Grzybowski, B. A. Reaction-diffusion systems in intracellular molecular transport and control. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4170–4198 (2010).

Epstein, I. R. & Xu, B. Reaction-diffusion processes at the nano- and microscales. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 312–319 (2016).

Grzybowski, B. A., Bishop, K. J. M., Campbell, C. J., Fialkowski, M. & Smoukov, S. K. Micro- and nanotechnology via reaction-diffusion. Soft Matter 1, 114–128 (2005).

Vanag, V. K. & Epstein, I. R. Cross-diffusion and pattern formation in reaction-diffusion systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11, 897–912 (2009).

Mandal, N. S., Sen, A. & Astumian, R. D. Kinetic asymmetry versus dissipation in the evolution of chemical systems as exemplified by single enzyme chemotaxis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5730–5738 (2023).

Nakamoto, T. & Ishida, H. Chemical sensing in spatial/temporal domains. Chem. Rev. 108, 680–704 (2008).

Squires, T. M., Messinger, R. J. & Manalis, S. R. Making it stick: convection, reaction and diffusion in surface-based biosensors. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 417–426 (2008).

Andrade-Restrepo, M., Ciuperca, I. S., Lemarre, P., Pujo-Menjouet, L. & Tine, L. M. A reaction-diffusion model of spatial propagation of A β oligomers in early stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Math. Biol. 82, 39 (2021).

Eliaš, J. & Clairambault, J. Reaction-diffusion systems for spatio-temporal intracellular protein networks: a beginner’s guide with two examples. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 10, 12–22 (2014).

Mandal, N. S., Sen, A. & Astumian, R. D. A molecular origin of non-reciprocal interactions between interacting active catalysts. Chem 10, 1147–1159 (2024).

Mai, A. Q., Bánsági, T. Jr, Taylor, A. F. & Pojman, J. A. Sr Reaction-diffusion hydrogels from urease enzyme particles for patterned coatings. Commun. Chem. 4, 101 (2021).

Geher-Herczegh, T. et al. Delayed mechanical response to chemical kinetics in self-oscillating hydrogels driven by the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. Macromolecules 54, 6430–6439 (2021).

Abe, K., Kawamata, I., Nomura, S.-I. M. & Murata, S. Programmable reactions and diffusion using DNA for pattern formation in hydrogel medium. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 4, 639–643 (2019).

Inui, K. et al. The Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction in thermoresponsive core-shell hydrogel microspheres with a Tris(2,2’-bipyridyl)ruthenium catalyst in the core. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 3828–3835 (2020).

Campbell, C. J., Klajn, R., Fialkowski, M. & Grzybowski, B. A. One-step multilevel microfabrication by reaction-diffusion. Langmuir 21, 418–423 (2005).

Lagzi, I., Kowalczyk, B. & Grzybowski, B. A. Liesegang rings engineered from charged nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 58–60 (2010).

Nabika, H., Itatani, M. & Lagzi, I. Pattern formation in precipitation reactions: the Liesegang phenomenon. Langmuir 36, 481–497 (2020).

Lovrak, M. et al. Free-standing supramolecular hydrogel objects by reaction-diffusion. Nat. Commun. 8, 15317 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Dynamic growth of macroscopically structured supramolecular hydrogels through orchestrated reaction-diffusion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310162 (2023).

Schlichter, L., Piras, C. C. & Smith, D. K. Spatial and temporal diffusion-control of dynamic multi-domain self-assembled gels. Chem. Sci. 12, 4162–4172 (2021).

Ravarino, P., Panja, S. & Adams, D. J. Spatiotemporal control over base-catalyzed hydrogelation using a bilayer system. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 43, e2200606 (2022).

Mahato, R. R., Priyanka, Shandilya, E. & Maiti, S. Perpetuating enzymatically induced spatiotemporal pH and catalytic heterogeneity of a hydrogel by nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 13, 8557–8566 (2022).

Leathers, A. et al. Reaction-diffusion patterning of DNA-based artificial cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17468–17476 (2022).

Bai, S. et al. Transient and directional growth of supramolecular hydrogels through reaction-diffusion-mediated self-assembly for dynamic wet gluing. Chem. Eng. J. 475, 146125 (2023).

Paikar, A. et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of hydrogel actuators by autocatalytic reaction networks. Adv. Mater. 34, e2106816 (2022).

van Roekel, H. W. H. et al. Programmable chemical reaction networks: emulating regulatory functions in living cells using a bottom-up approach. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7465–7483 (2015).

Paikar, A. et al. Chemical waves in reaction-diffusion networks of small organic molecules. Chem. Sci. 16, 659–669 (2025).

Semenov, S. N., Markvoort, A. J., de Greef, T. F. A. & Huck, W. T. S. Threshold sensing through a synthetic enzymatic reaction-diffusion network. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 8066–8069 (2014).

Nguindjel, A.-D. C., de Visser, P. J., Winkens, M. & Korevaar, P. A. Spatial programming of self-organizing chemical systems using sustained physicochemical gradients from reaction, diffusion and hydrodynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 23980–24001 (2022).

Zheng, L. et al. Catalytic transport of molecular cargo using diffusive binding along a polymer track. Nat. Chem. 11, 359–366 (2019).

Leira-Iglesias, J., Tassoni, A., Adachi, T., Stich, M. & Hermans, T. M. Oscillations, travelling fronts and patterns in a supramolecular system. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1021–1027 (2018).

Zadorin, A. et al. Synthesis and materialization of a reaction–diffusion French flag pattern. Nat. Chem. 9, 990–996 (2017).

Chen, R., Das, K., Cardona, M. A., Gabrielli, L. & Prins, L. J. Progressive local accumulation of self-assembled nanoreactors in a hydrogel matrix through repetitive injections of ATP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2010–2018 (2022).

Chen, R., Neri, S. & Prins, L. J. Enhanced catalytic activity under non-equilibrium conditions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 868–874 (2020).

Kar, H., Goldin, L., Frezzato, D. & Prins, L. J. Local self-assembly of dissipative structures sustained by substrate diffusion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202404583 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Spatiotemporal control over self-assembly of supramolecular hydrogels through reaction-diffusion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 664, 938–945 (2024).

Kar, H., Chen, R., Das, K. & Prins, L. J. Transient transition from stable to dissipative assemblies in response to the spatiotemporal availability of a chemical fuel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202414495 (2025).

Li, Q. & Calhoun, V. D. Reaction-diffusion model for brain spacetime dynamics. Biophys. Rep. 5, 100220 (2025).

Gentili, P. L., Zurlo, M. P. & Stano, P. Neuromorphic engineering in wetware: the state of the art and its perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 18, 1443121 (2024).

Dúzs, B. et al. Mechano-adaptive meta-gels through synergistic chemical and physical information-processing. Nat. Commun. 15, 8957 (2024).

Mahato, R. R., Shandilya, E., Dasgupta, B. & Maiti, S. Dictating catalytic preference and activity of a nanoparticle by modulating its multivalent engagement. ACS Catal. 11, 8504–8509 (2021).

Mahato, R. R., Juneja, S. & Maiti, S. Benchmarking cationic monolayer protected nanoparticles and micelles for phosphate-mediated and nucleotide-selective proton transfer catalysis. Chem. Asian J. 18, e202300657 (2023).

Rani, S. et al. Superior proton-transfer catalytic promiscuity of cytochrome c in self-organized media. ChemBiochem 22, 1285–1291 (2021).

Cullen, W., Misuraca, M. C., Hunter, C. A., Williams, N. H. & Ward, M. D. Highly efficient catalysis of the Kemp elimination in the cavity of a cubic coordination cage. Nat. Chem. 8, 231–236 (2016).

Shandilya, E. & Maiti, S. Self-regulatory micro- and macroscale patterning of ATP-mediated nanobioconjugate. ACS Nano 17, 5108–5120 (2023).

Keating, M., Chen, Y., Larmour, I. A., Faulds, K. & Graham, D. Growth and surface-enhanced Raman scattering of Ag nanoparticle assembly in agarose gel. Meas. Sci. Technol. 23, 084006 (2012).

Mukerjee, P. & Banerjee, K. A study of the surface pH of micelles using solubilized indicator dyes. J. Phys. Chem. 68, 3567–3574 (1964).

Mohajerani, F., Zhao, X., Somasundar, A., Velegol, D. & Sen, A. A theory of enzyme chemotaxis: from experiments to modeling. Biochemistry 57, 6256–6263 (2018).

Straube, A. V., Winkelmann, S. & Höfling, F. Accurate reduced models for the pH oscillations in the Urea–Urease reaction confined to giant lipid vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 2955–2967 (2023).

Aubert, S., Bezagu, M., Spivey, A. C. & Arseniyadis, S. Spatial and temporal control of chemical processes. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 706–722 (2019).

Yadav, R., Sivoria, N. & Maiti, S. Salt gradient-induced phoresis of vesicles and enhanced membrane fusion in a crowded milieu. J. Phys. Chem. B 128, 9573–9585 (2024).

Priyanka & Maiti, S. Probing phoretic transport of oxidative enzyme-bound Zn (II)-metallomicelle in adenosine triphosphate gradient via a spatially relocated biocatalytic zone. Langmuir 40, 18906–18916 (2024).

Priyanka, Shandilya, E., Brar, S. K., Mahato, R. R. & Maiti, S. Spatiotemporal dynamics of self-assembled structures in enzymatically induced agonistic and antagonistic conditions. Chem. Sci. 13, 274–282 (2022).

Deng, S. et al. Spatiotemporal control for integrated catalysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 3, 1–19 (2023).

Harrison, L. G. What is the status of reaction-diffusion theory thirty-four years after turing?. J. Theor. Biol. 125, 369–384 (1987).

Carstens, J. L. et al. Spatial multiplexing and omics. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 4, 1–19 (2024).

Shandilya, E., Rallabandi, B. & Maiti, S. In situ enzymatic control of colloidal phoresis and catalysis through hydrolysis of ATP. Nat. Commun. 15, 3603 (2024).

Juneja, S., Sivoria, N. & Maiti, S. Spatial shifting of biocondensate assembly zone in a microfluidic gradient of dissipative condition. ChemSystemsChem 7, e202400084 (2025).

Gentili, P. L. & Stano, P. Living cells and biological mechanisms as prototypes for developing chemical artificial intelligence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 720, 150060 (2024).

Shandilya, E. & Maiti, S. Interconnectivity between surface reactivity and self-assembly of kemp elimination catalyzing nanorods. Chem. -Eur. J. 27, 7831–7836 (2021).

Giner-Sanz, J. J. et al. Salicylate method for ammonia quantification in nitrogen electroreduction experiments: the correction of iron III interference. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 134519 (2020).

Adikessavane, N. & Maiti, S. A chemoenzymatic reaction-diffusion system with local inhibition and distal activation: computational model and simulation results (v.1.0.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17336949 (2025).

Acknowledgements

S.M. acknowledges financial support of ANRF (File No. CRG/2022/002345). N.K.E. acknowledges CSIR, India (09/0947(12588)/2021-EMR-I). R.R.M. acknowledges IISER Mohali for the doctoral research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.R.M. performed most of the experiments including synthesis. N.A. developed the theory. N.K.E. performed kinetic analysis and zeta potential measurement. S.M. designed and supervised the project, wrote the manuscript and all authors commented on it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahato, R.R., Adikessavane, N., Ettikkan, N.K. et al. A chemoenzymatic reaction-diffusion system with local inhibition and distal activation. Nat Commun 16, 9885 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65605-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65605-2