Abstract

Developing an energy-efficient process to convert chemically inert CO2 to methanol is of great significance in sustainable chemistry. Herein, we report an indirect pathway for methanol synthesis below 100 °C, utilizing CO2-derived dimethyl carbonate (DMC) as a bridging molecule. By engineering oxygen vacancies in In2O3, we construct a Lewis acidic combination of In5 sites and In4…In4 ּpairs that efficiently activate H2 and DMC, respectively. The spatial intimacy of In5 and In4…In4 enables efficient transfer of generated *H, achieving a methanol generation rate of 31.6 mmol ּgcat-1 h-1 with >99.99% selectivity at 100 °C. Integrating DMC synthesis from CO2 with subsequent hydrogenation in a single reactor via alternating feedstreams from CO2 to H2, the optimized In2O3 catalysts yield a methanol production rate of 5.2 mmol ּgcat-1 h-1 at 100 °C, outperforming the performance of previous catalysts through direct CO2 hydrogenation even at temperatures over 200 °C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methanol (CH3OH), a crucial industrial chemical and a promising energy carrier, has received significant attention in developing its synthetic methodologies in the aspect of both fundamental research perspectives and practical applications1,2,3,4. Given the pressing global climate challenges, the utilization of CO2 instead of the predominantly used CO for methanol synthesis is of utmost importance in achieving efficient carbon resource cycles5,6,7,8. According to Le Chatelier’s principle, the hydrogenation of CO2 to CH3OH, being an exothermic reaction accompanied with a reduction in the number of reaction molecules, is thermodynamically favored under conditions of high pressure and low temperature1,4,9,10,11. However, low reaction temperatures lead to an unsatisfactory reaction rate to activate thermodynamic stability and chemical inertness of CO23,12,13,14. Additionally, the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction becomes highly thermodynamic feasible under methanol synthesis conditions, leading to the hydrogen wastage and reduced CH3OH yield3,13,14,15,16,17. Therefore, developing an effective strategy to achieve low-temperature CH3OH synthesis from CO2 remains a highly appealing yet formidable challenge.

Recently, the indirect transformation of CO2 to CH3OH via carbonate derivatives as intermediates, which can be readily produced from CO2, has emerged, as illustrated in Fig. 1a18,19. Among various carbonate derivatives, dimethyl carbonate (DMC) has garnered particular attention due to several compelling reasons: (I) CH3OH as the sole product via DMC hydrogenation; (II) the notably lower bond energy of C–O in DMC (301.6 kJ mol−1) than that of C=O in CO2 (760.6 kJ mol−1, Fig. 1b); (III) the easy industrialization of DMC through the carbonylation of CH3OH with CO2 at the temperatures below 140 °C19,20. Homogeneous Ru-based catalysts have demonstrated their capability in DMC hydrogenation into CH3OH at 110 °C and 1 MPa H218, garnering considerable attention in the CH3OH synthesis through this indirect approach21,22,23,24. However, homogeneous catalysts face on significant challenges of separation and recyclability, particularly for noble metal-based complexes. To date, heterogeneous catalysts, commonly employed in large-scale chemical industries, have not been reported for DMC hydrogenation under analogous reaction conditions25,26,27. The development of highly efficient heterogeneous catalysts for achieving DMC hydrogenation under mild conditions is of utmost importance in providing an indirect and energy-efficient approach for CH3OH synthesis from CO2.

Herein, porous nanocubes of In2O3 (PC-In2O3) with meticulously engineered oxygen vacancy concentrations have demonstrated exceptional catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability for DMC hydrogenation to CH3OH under mild reaction conditions (≤100 °C, 2 MPa). An optimal concentration of oxygen vacancies on PC-In2O3 is critical for constructing a new Lewis acidic combination with the spatially intimate In5 sites and In4…In4 pairs (Fig. 1a). The Lewis acidic In5 sites, arising from the absence of one oxygen vacancy, facilitate H2 dissociation. Simultaneously, the formation of two adjacent In4…In4 pairs by removing two O atoms enable effective activation of DMC through simultaneous binding of two In4 sites with two O atoms in the C=O and C–O–C bonds of DMC. Due to their spatial intimacy, *H species generated at In5 directly hydrogenate the adsorbed DMC, achieving a CH3OH generate rate of 31.6 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 100 °C. Combining the exceptional catalytic performances of PC-In2O3 for both the CH3OH carbonylation to DMC and the hydrogenation of DMC, the catalysts delivered a CH3OH generation rate of 5.2 mmol gcat−1 h−1 via the indirect transformation pathway at 100 °C (Fig. 1a), outperforming state-of-the-art heterogeneous catalysts operating at >200 °C. This simple catalyst, which employs DMC hydrogenation as a bridge, highlights the potential for low-emission CH3OH synthesis from CO2 as raw materials for industrial applications.

Results

Theoretical analysis

Generally, the adsorption and activation of oxygen-containing molecules necessitate metal oxides with oxygen vacancy. However, metal oxides typically exhibit low capability for H2 dissociation. Recently, defective indium oxides (In2O3), characterized by abundant oxygen vacancy, have shown promise for hydrogenation of CO2 into CH3OH, despite the fact that a high temperature (>200 °C) is generally required to realize the simultaneous activation of H2 and CO228,29,30,31,32. This motivates us to explore the potential of In2O3 for the co-activation of DMC and H2 by regulating its oxygen vacancy levels, thereby enabling a low-temperature CH3OH synthesis through an indirect transformation route (Fig. 1a).

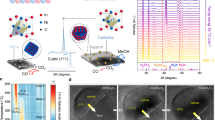

Initially, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to investigate the adsorption and activation of H2 and DMC on In2O3 surface. The most stable In2O3(111) crystal face was selected as the representative model28,33. The In2O3(111) crystal face features a distinct arrangement of four layers of oxygen atoms associated with one layer of In atoms (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similar to previous reports34,35,36, the lattice O atoms on the first layer are removed to construct an electronically neutral In2O3(111) surface. On the In2O3(111) surface, three typical Lewis acidic In sites are formed (Fig. 2a): (i) a six-coordinated In site (In6); (ii) a five-coordinated In site (In5, coordinated with two oxygen atoms at the second layer and three oxygen atoms at the third layer); and (iii) another five-coordinated In site (In4+1, coordinated with one oxygen atom at the second layer, three oxygen atoms at the third layer and one oxygen atom at the fourth layer). Based on charge distribution analysis, the differential charge density of In6, In5, In4+1 active sites are +1.60 |e|, +1.56 |e|, and +1.55 |e|, respectively (Fig. 2a).

a Optimized structure of In6, In5 and In4+1 on the In2O3(111) surface and optimized structure of In4…In4 the In2O3(111) surface with one oxygen vacancy. b Optimized H2 adsorption on In6, In5, In4+1 and In4…In4 of the In2O3(111) surface. c H2 dissociation on In5, In4+1 and In4…In4 of the In2O3(111) surface. d Optimized DMC adsorption on In6, In5, In4+1 and In4…In4 of the In2O3(111) surface. e Relative energy for DMC hydrogenation via the In5 site and In4…In4 pairs. Inset: Differential charge density for the DMC adsorbed on the In5 site and In4…In4 pairs.

By further removing one lattice oxygen atom (OI) at the second layer, another Lewis acidic In site (In4) is generated, where the In atom coordinates with one oxygen atom in the second layer, two in the third layer and one in the fourth layer (Fig. 2a). In this scenario, the differential charge density of In5 decreases to +1.54 |e|. While the two In4 sites exhibit charges of +1.32 |e| and +1.25 |e|, respectively. Thus, the introduction of oxygen vacancies enhances the Lewis acidity of coordinately unsaturated Inn+ sites. Notably, the induced In4 sites form Lewis acidic pairs of In4…In4 (Fig. 2a), a unique configuration potentially crucial for H2 or DMC adsorption and activation.

Starting with H2 adsorption (Supplementary Fig. 2), the In6 site displays weak adsorption with an adsorption energy of −0.086 eV (Fig. 2b). In contrast, the coordinately unsaturated In5 and In4+1 exhibit stronger H2 adsorption, with adsorption energies of −0.14 eV and −0.13 eV, respectively (Fig. 2b). Despite their comparable adsorption strengths, the energy barrier for H2 dissociation on In5 is significantly lower at 0.61 eV compared to that of 1.32 eV on In4+1 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3). Further increasing the oxygen vacancies to form In4…In4 weakens H2 adsorption (−0.086 eV, Fig. 2b) while increasing the dissociation barrier to 0.73 eV (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3). Both thermodynamic and kinetic analyses identify that In5 is the optimal site for H2 dissociation into *H species. The differential charge density of H2 on In5 reveals a transition state with uneven distribution, which ultimately reverts to a uniform distribution in the final state (Fig. 2c).

For DMC adsorption, In6 shows weak interaction (−0.42 eV) relative to oxygen-deficient surfaces (Fig. 2d). Comparable adsorption energies of −1.07 eV and −0.92 eV occur at In5 and In4+1, respectively (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4). Critically, introducing an additional oxygen vacancy strengthens DMC adsorption, as evidenced by the more negative adsorption energy (−1.24 eV) on In4…In4 (Fig. 2d), compared to In4…In4+1 (0.89 eV, Supplementary Fig. 4). This enhancement arises from the augmented Lewis acidity of In4…In4, driving greater charge transfer from DMC to In2O3 (Fig. 2e). In the optimized configuration, both O atoms of the C=O and C–O–CH3 bonds in DMC coordinate to nearby In4…In4, reducing the distance between the C–O–CH3 bond and the catalyst surface to 2.5 Å (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4). The synergistic interplay of enhanced electron transfer and proximity between DMC and the catalyst surface demonstrates the potential of In4…In4 via the tailorable structural defects for promoting DMC activation.

Subsequently, the energy profiles of reaction intermediates during the DMC-to-CH3OH hydrogenation were investigated on In4…In4 and In5 (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 5). For the rate-determining step (RDS) involving the transformation of methoxy-carbonyl (*MC) to *CO + *MeO, the energy requirement at In4…In4 is 1.40 eV, significantly lower than that of 4.01 eV on In5. This substantial difference underscores markedly enhanced reaction kinetics on In4…In4. Beyond the RDS, other intermediate transformations also exhibit consistently lower energy requirements on In4…In4 than on In5, demonstrating its superior thermodynamic favorability across the entire reaction pathway. Collectively, these findings establish the In4…In4 pair as the most promising active site for DMC adsorption/hydrogenation.

DFT calculations reveal that the combination of In5 and In4…In4 exhibits great potential for DMC hydrogenation under mild conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 3, (I) the In5 sites primarily dissociate H2 to generate *H; (II) DMC adsorbe and activate on In4…In4 via simultaneous interaction with its two O atoms in C=O and C–O–C bonds; (III) the spatial intimacy of In5 and In4…In4 allows direct transfer of generated *H to the activated DMC. Theoretically, high concentration of oxygen vacancies in In2O3 promotes the formation of In4…In4. However, moderate concentrations are essential for efficient H2 dissociation on In5. Thus, In2O3 with an optimized oxygen vacancy is expected to construct the spatially intimate Lewis acidic combination of In5 and In4…In4, facilitating low-temperature CH3OH synthesis from CO2 and H2 via the indirect pathway (Fig. 1a).

Characterization and catalytic performance of In2O3

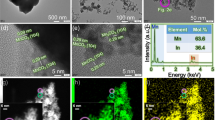

Porous nanocubes of In2O3 (PC-In2O3) were synthesized through a two-step process. Initially, the In(OH)3 precursors were prepared via hydrothermal approach at 100 °C, as verified by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Supplementary Fig. 6). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images revealed the typical nanocubic morphology for as-synthesized In(OH)3, with an average size of 29.5 ± 8.6 nm (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). The measured lattice parameter of 0.284 nm corresponded to the (220) crystal face of In(OH)3 (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). Subsequently, the In(OH)3 precursors were calcined under air at 250 °C to obtain PC-In2O3. XRD patterns confirmed the successful phase transformation from In(OH)3 to In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 6)37,38. Dark-field TEM images revealed that PC-In2O3 maintained its nanocubic morphology while exhibiting a porous structure (Fig. 4a). High-resolution TEM image revealed a lattice fringe spacing of 0.30 nm, indicating the dominant exposure of In2O3(222) crystal face (Fig. 4b).

a Dark-field TEM and b HR-TEM images of PC-In2O3. c XPS In 3d profiles of the PC-In2O3 and spent PC-In2O3 catalysts. d CH3OH generation rates of PC-In2O3 for the DMC hydrogenation. e Cyclability of PC-In2O3 for the DMC hydrogenation. Reaction conditions: catalysts (20 mg), DMC (5 mL), 1 h, 100 °C, and 2 MPa H2.

The surface properties of PC-In2O3 were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). Conventional In2O3 nanoparticles (NP-In2O3, Supplementary Fig. 8) were synthesized as a reference via thermal decomposition of In(NO3)3. Notably, the binding energy of In 3d spectra for PC-In2O3 was lower than that for NP-In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 9a), consistent with a reduced indium valence state. This observation was further substantiated by EPR spectroscopy, where PC-In2O3 displayed a significantly stronger signal at g = 2.003 compared to NP-In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 9b), providing unambiguous evidence of the enriched oxygen vacancies in PC-In2O339. Thus, PC-In2O3, characterized with dominant (222) facet exposure and abundant oxygen vacancies, satisfies the surface features predicted by DFT simulations for efficient DMC hydrogenation.

Then, the DMC hydrogenation was evaluated under 2.0 MPa H2 at 100 °C, with commercial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 as the benchmark. The PC-In2O3 catalysts achieved a CH3OH generation rate of 31.6 mmol gcat−1 h−1, significantly outperforming both Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 (4.7 mmol gcat−1 h−1) and NP-In2O3 (2.3 mmol gcat−1 h−1, Fig. 4d). Even after surface area-normalized comparison (PC-In2O3: 56.1 m2 g−1, NP-In2O3: 3.8 m2 g−1, Supplementary Fig. 10a), 20 mg of PC-In2O3 still delivered a significantly higher CH3OH generation rate (0.63 mmol h−1) than 295 mg of NP-In2O3 (0.41 mmol h−1) with equivalent surface area (Supplementary Fig. 10b). This quantitative comparison conclusively demonstrates the superior intrinsic catalytic activity of PC-In2O3. Both gas chromatography and 1H-NMR analysis of liquid products indicated exclusive production of CH3OH (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Although trace CO and CO2 were detected in the gas phase products (Supplementary Fig. 11b), PC-In2O3 still exhibited >99.99% CH3OH selectivity, exceeding that of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 (99.7%) and NP-In2O3 (99.6%, Fig. 4d).

Subsequently, the catalytic stability of PC-In2O3 was evaluated by centrifugal separation and reuse over multiple cycles without additional treatments. Both the CH3OH generation rate and selectivity remained nearly constant for at least 6 cycles (Fig. 4e). TEM image of the spent PC-In2O3 catalysts confirmed the preservation of morphology (Supplementary Fig. 12a). XPS analysis further showed that the In 3 d (Fig. 4c) and O 1s (Supplementary Fig. 12b) spectra remained unchanged between pristine and spent PC-In2O3, indicating preserved surface chemical states throughout the catalytic reaction. Therefore, the PC-In2O3 catalysts demonstrated exceptional activity, selectivity, and stability for DMC hydrogenation at <100 °C.

Identifying the critical function of oxygen vacancy

Initial DFT calculations revealed that oxygen vacancies enable the formation of In5 and In4…In4 on the In2O3 surface, facilitating H2 and DMC adsorption/activation, respectively. Quantitative EPR combined with XPS In 3d spectra confirmed significantly higher oxygen vacancy concentration in PC-In2O3 than NP-In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 9), correlating with enhanced catalytic efficiency. To isolate the roles of oxygen vacancy while minimizing morphological influences, we synthesized a series of structurally controlled catalysts.

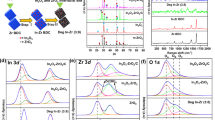

Porous In2O3 nanocubes with tunable oxygen vacancy concentrations were synthesized by calcining In(OH)3 precursors in air at various temperatures. Thermal treatment at 350 °C to 450 °C progressively reduced the concentration of oxygen vacancy, yielding PC-In2O3-350 and PC-In2O3-450, respectively. XRD (Supplementary Fig. 13) and HAADF-STEM (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15) confirmed identical In2O3 phase and similar morphology across all catalysts37,38. XPS analysis showed a systematic shift of the In 3d peaks to higher binding energies with increased calcination temperature (Fig. 5a), indicating a progressively elevated In oxidation states. EPR spectra confirmed a systematic decrease in the integrated intensity of the oxygen vacancy signals at g = 2.003 (Fig. 5b)39,40,41,42, establishing an oxygen vacancy concentration order: PC-In2O3 > PC-In2O3-350 > PC-In2O3-450. Crucially, XPS O 1s spectra revealed negligible change in surface -OH fractions and slight increase in lattice oxygen fractions (Supplementary Fig. 16), demonstrating that calcination primarily modulated oxygen vacancies and In oxidation state while leaving surface -OH stable. This well-defined material series provided an ideal platform to isolate oxygen vacancy effects of In2O3 on DMC hydrogenation.

a XPS analysis of In 3d peaks and b EPR spectra of PC-In2O3, PC-In2O3-350 and PC-In2O3-450. c The correlation of CH3OH generation rates and Ea values with the normalized area of EPR for DMC hydrogenation. DRIFTS spectra of d pyridine and e DMC adsorption at room temperature. f In situ DRIFTS spectra for H2 and D2 dissociation on the surface of PC-In2O3 and PC-In2O3-450 at 150 °C. g The influence of pyridine concentrations on the catalytic performance of PC-In2O3 for DMC hydrogenation. h Scheme of spatially intimate Lewis acidic combination of In5 and In4…In4. i H2/D2 isotope effects of PC-In2O3 in DMC hydrogenation. Reaction conditions: catalysts (20 mg), DMC (5 mL), 1 h, 100 °C, and 2 MPa H2/D2.

The CH3OH generation rates decreased near-linearly with declining normalized EPR signal intensity (Fig. 5c), highlighting the critical dependence of DMC hydrogenation on oxygen vacancy concentration. To kinetically probe intrinsic activity, activation energy (Ea) was determined via Arrhenius analysis (Supplementary Fig. 17). Consistent with observed activity trends, PC-In2O3 exhibited the lowest Ea (26.8 kJ mol−1), conclusively confirming its highest intrinsic activity (Fig. 5c). Given identical crystal phase and similar morphologies, the observed Ea differences demonstrate that the intrinsic activity is directly governed by oxygen vacancy concentration (Fig. 5c).

Meanwhile, XPS analysis of O 1s spectra confirmed the present of surface hydroxyl (-OH) groups on these In2O3 catalysts, with a coverage of ~30% (Supplementary Fig. 16)43,44,45. This observation was further supported by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) of PC-In2O3, which showed characteristic peaks at 3650 cm−1 and 3235 cm−1, consistent with the vibrational modes of surface -OH group (Supplementary Fig. 18). Notably, the surface -OH groups remained stable at temperatures below 450 °C, as evidenced by the barely changed -OH fractions in PC-In2O3 and PC-In2O3-450. DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 19) reveal minimal impact of -OH moiety on DMC adsorption when it is bond to subsurface oxygen atom adjacent to the In4…In4 site, or when surface -OH coverage is below 25%. Significant weakening of DMC adsorption occurs only at much higher -OH coverages (>33.3%), which exceed the coverage (~30%) experimentally observed on PC-In2O3. Although high-temperature N2 treatment reduced surface -OH groups of PC-In2O3 from 32.4% to 27.8%, this reduction slightly enhanced the hydrogenation activity (Supplementary Fig. 20). These results indicate that surface -OH groups maintain stable coverage under reaction conditions and exert negligible influence on the process. Instead, the concentration of oxygen vacancies is the decisive factor governing the intrinsic activity of In2O3 for DMC hydrogenation.

Evidence of the presence of In4…In4 sites

To characterize the distinct Inn+ sites derived from varying oxygen vacancy concentrations on the In2O3 surface, DRIFTS tests were performed using pyridine as a probe molecule. Characteristic peaks corresponding to ring-breathing vibrations of H-bonded pyridine and pyridine coordinated to Lewis acidic In sites were observed at ~1438 cm−1 and ~1447 cm−1, respectively (Fig. 5d)46. Comparing the bands of PC- In2O3, PC-In2O3-350, and PC-In2O3-450, a noticeable red-shift occurred in the bands associated with pyridine coordinated to Inn+ sites as oxygen vacancy concentration increased, while peaks for H-bonded pyridine remained largely unchanged. DFT calculations revealed that the In4 sites formed at higher oxygen vacancy levels exhibit enhanced Lewis acidity, resulting in stronger adsorption of pyridine compared to the In5 sites. This red-shift directly reflects the augmented pyridine adsorption on PC-In2O3, thereby corroborating the increase in In4 sites linked to a higher concentration of oxygen vacancies.

DFT calculations also demonstrated that a sufficient density of oxygen vacancies on the In2O3 surface facilitates the formation of In4…In4, enabling a unique adsorption configuration of DMC through bonding with two O atoms of the C=O and C–O–C bonds. DRIFTS spectra were then employed to investigate DMC adsorption on In2O3. Characteristic peaks corresponding to the O–C–O stretching vibration at ~1279 cm−1 and 1310 cm−1 were observed on all In2O3 catalysts (Fig. 5e)20,47. Critically, the concurrent bonding of DMC with two O atoms on the In4…In4 pairs of PC-In2O3 resulted in a distinct peak at 1220 cm−1, assigned to the unbonded C–O stretching vibration. The significantly lower wavenumber of this peak signified stronger adsorption of DMC on In4…In4 pairs compared to the isolated Inn+ sites. Conversely, this specific peak was barely detectable for PC-In2O3-450, indicating a scarcity of In4…In4 due to its lower oxygen vacancy concentration. Thus, DRIFTS spectra provide direct experimental evidence to support the presence of In4…In4 for DMC activation, consistent with the DFT calculations.

Subsequently, in situ DRIFTS experiments were further conducted to elucidate the coexistence of In5 and In4…In4. Specifically, PC-In2O3 was firstly pretreated with H2 at 150 °C for 10 min, followed by exposure to D2. The rapid appearance of surface -OH groups (3250 cm−1) indicated the occurrence of H2 dissociation, generating *H species stabilized by O atoms (Fig. 5f). Upon switching from H2 to D2, the characteristic peaks of -OD groups gradually emerged (2410 cm−1, Fig. 5f). As revealed by DFT calculations (Fig. 2c), due to the weaker interaction between *H species and O atom adjacent to In5, the D/H exchange process on the In5 region is significantly faster than that on In4…In4. The gradual increase of -OD peaks and incomplete disappearance of -OH peaks revealed the presence of both In5 sites and In4…In4 pairs in PC-In2O3. In contrast, for PC-In2O3-450 with a reduced concentration of oxygen vacancies, the decreased number of In5 led to a weaker H/D exchange process. Consequently, the characteristic peaks of -OD groups exhibited a slight increase during D2 flow under the same treatment process (2418 cm−1, Fig. 5f).

H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) measurements were further conducted to directly assess H2 dissociation of In2O3. The PC-In2O3 catalysts exhibited a prominent H2 consumption peak at 165 °C, which was notably lower than the peak (193 °C) observed for PC-In2O3-350 (Supplementary Fig. 21). Conversely, the PC-In2O3-450 catalysts showed the weak H2 consumption peak, indicating weak H2 adsorption on the nearly ideal In2O3 surface. The capacity of H2 activation on In2O3 was also analyzed using an electrochemical method through comparing their H2 oxidation potentials48,49,50, revealing a consistent trend of PC-In2O3 > PC-In2O3-350 > PC-In2O3-450 (Supplementary Fig. 22).

The preceding analysis conclusively demonstrates that PC-In2O3, characterized by abundant oxygen vacancies, generate In5 and In4…In4 that efficiently adsorb and activate H2 and DMC, respectively. These structural features ultimately result in the highest intrinsic activity of PC-In2O3 for DMC hydrogenation. To further explore the roles of oxygen vacancy, the DMC hydrogenation was conducted under identical reaction conditions in the presence of pyridine as a shielding molecule51,52. As expected, the CH3OH generation rates reduced consistently from 31.6 mmol gcat−1 h−1 to 18.8 mmol gcat−1 h−1 and then to 10.3 mmol gcat−1 h−1 with increasing concentrations of pyridine (Fig. 5g). Hence, these pyridine capture experiments unequivocally demonstrate that the oxygen vacancy of In2O3 plays a direct and crucial role in the hydrogenation of DMC.

Meanwhile, it is crucial to recognize that elevated oxygen vacancy concentrations do not universally enhance the catalytic activity of In2O3. DFT calculations revealed that the In5 sites exhibit a higher capacity for H2 dissociation compared to In4…In4 was constructed in In2O3 with a higher level of oxygen vacancy. Moreover, under conditions of sufficient H2 supply, the H2 dissociation on PC-In2O3 was not the rate-determining step for DMC hydrogenation, as verified by the controlled H2 pressure experiments (Supplementary Fig. 23). To investigate the influences of increased oxygen vacancies in In2O3, the PC-In2O3-H2 catalysts were prepared by annealing PC-In2O3 at 350 °C for 2 h under 10% H2/Ar to introduce more oxygen vacancies (Supplementary Fig. 24a). H2-TPR analysis of PC-In2O3-H2 revealed a H2 consumption peak at 260 °C, indicating a lower capacity for H2 dissociation compared to PC-In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 24b). This could be attributed to the decreased number of In5 sites in PC-In2O3-H2 for H2 activation. Consequently, the CH3OH generation rate of PC-In2O3-H2 significantly decreased to 11.3 mmol gcat−1 h−1 compared to that of PC-In2O3 (31.6 mmol gcat−1 h−1, Supplementary Fig. 24c), suggesting that excessive oxygen vacancies in In2O3 may compromise its catalytic activity for DMC hydrogenation.

The spatial intimacy of In5 sites and In4…In4 pairs

The spatial proximity of In5 and In4…In4 facilitates direct utilization of *H generated on In5 for DMC hydrogenation (Fig. 5h). Then, the H2/D2 isotope effects were examined to investigate the H2 dissociation. For PC-In2O3, DMC hydrogenation exhibited a slight decrease by a factor of 1.05, attributable to the zero-point energy difference between isotopic isomers (Fig. 5i). The minimal isotope effect unambiguously confirmed strong capacity of PC-In2O3 for H2 dissociation under operation conditions. Furthermore, the absence of a discernible isotope effect indicated that the DMC hydrogenation on PC-In2O3 did not involve a hydrogen spillover associated with the O–H cleavage on metal oxides53,54, highlighting the spatial intimacy of In5 sites and In4…In4 pairs that guarantee the direct hydrogenation of DMC.

The hydrogenation of DMC on In2O3 was further probed via in situ DRIFTS. Progressive emergence of characteristic peaks at 1294.5 cm−1, 1460.3 cm−1, and 1767.6 cm−1 (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 25), corresponding to monomethyl carbonate, indicated the DMC adsorption on various In2O3 surfaces at 100 °C. Notably, PC-In2O3 with the moderate concentration of oxygen vacancy exhibited the fastest formation rate of these feature peaks, suggesting the rapid enrichment of DMC molecules on its surface compared to PC-In2O3-450 (lower level of oxygen vacancy) and PC-In2O3-H2 (higher level of oxygen vacancy). After achieving the saturated DMC adsorption, Ar flow was introduced at 100 °C for 10 min to remove the physisorbed molecules (Supplementary Fig. 26), followed by H2 exposure under identical conditions. In situ DRIFTS profiles revealed progressive attenuation of DMC characteristic peaks, providing the direct spectroscopic evidence for DMC hydrogenation at 100 °C (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 27). Notably, the characteristic peaks disappeared significantly faster on PC-In2O3 than on PC-In2O3-450 and PC-In2O3-H2. These results thus confirmed the exceptional capacity of PC-In2O3 for the DMC hydrogenation, arising from the spatial intimacy of In5 and In4…In4 that enables simultaneous enhancement of H2 and DMC adsorption/activation.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of PC-In2O3, PC-In2O3-450, and PC-In2O3-H2 under a flow of a DMC and b then H2. Note: The catalysts were pretreated under a flow of Ar at 100 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, a flow of Ar was passed through a DMC solution at room temperature and introduced into the in situ cell. DRIFTS signals were recorded at intervals of 30 s (a). Subsequently, the gas flow was switched to pure Ar to eliminate the physically adsorbed DMC until the spectra stabilized. Finally, a flow of 50 vol.% H2/Ar gas was introduced and maintained for another 30 min to collect the DRIFTS signal every 30 s (b).

Critically, during H2 exposure, the broad -OH stretching vibrations (3200–3800 cm−1) remained remarkably stable across PC-In2O3, PC-In2O3-450, and PC-In2O3-H2 (Supplementary Fig. 27), indicating negligible depletion or structural transformation of surface -OH groups under reaction conditions. Collectively, these observations, including stable catalytic performance as evidenced from multiple catalytic cycling, unchanged post-reaction surface chemistry as revealed from XPS measurements, and the absence of dynamic -OH group formation as observed from in situ DRIFTS spectra, strongly indicate that the surface properties of PC-In2O3 remain structurally and chemically stable under reaction conditions.

CH3OH synthesis through indirect transformation process

To explore the feasibility of indirect CO2-to-CH3OH transformation, the conversion of CO2 and CH3OH into DMC (Step I) was conducted over PC-In2O3 under 1.0 MPa CO2. At 100 °C, PC-In2O3 exhibited a remarkable DMC generation rate of 8.1 mmol gcat−1 h−1. Subsequently, the reaction system was purged with H2 and maintained under 2.0 MPa for the DMC hydrogenation (Step II). In contrast to pure DMC, the DMC hydrogenation in CH3OH solution yielded a lower CH3OH generation rate of 14.3 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 100 °C. Through the proposed indirect transformation process involving CO2 and H2 with DMC as the bridge, PC-In2O3 achieved an overall CH3OH generation rate of 5.2 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 100 °C (Fig. 7a). Comparatively, when PC-In2O3 was used for the direct hydrogenation of CO2 under a gas pressure of 2 MPa, the CH3OH generation rate was merely 0.5 mmol gcat−1 h−1 (Fig. 7a). Significantly, the CH3OH generation rate over PC-In2O3 at 100 °C via the indirect transformation exceeds those reported for state-of-the-art catalysts even at >200 °C (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Table 2). This activity comparison confirms the advantages of the indirect route for CO2-to-CH3OH conversion.

a Comparison of the CH3OH generation rates of PC-In2O3 through the direct hydrogenation of CO2 and indirect transformation of CO2 with DMC as a bridge. Reaction conditions through direct hydrogenation of CO2: catalysts (20 mg), THF (5 mL), 1 h, 100 °C, and 2 MPa (25% CO2 + 75% H2). Reaction conditions through indirect transformation: catalysts (20 mg), CH3OH (5 mL), 100 °C, Step I: 1 MPa CO2 and 2 h; Step II: 2 MPa H2 and 0.5 h. b Comparison of the CH3OH generation rates of PC-In2O3 through the indirect transformation of CO2 and other state-of-the-art catalysts (see Supplementary Table S2 for more details).

Discussion

In summary, we have designed and constructed a Lewis acidic combination on the In2O3 surface by optimizing oxygen vacancy concentration, comprising spatially intimate Lewis acidic In5 sites and In4…In4 pairs. The In5 sites exhibit exceptional capability for H2 dissociation with a low energy barrier of 0.61 eV. Furthermore, the unique In4…In4 pairs efficiently adsorb and activate DMC through the simultaneous activation of the C=O and C–O–CH3 bonds. The spatial intimacy of In5 and In4…In4 enables the direct hydrogenation of DMC adsorbed on In4…In4 by the *H species generated on In5, yielding a high catalytic activity for DMC hydrogenation. Consequently, the PC-In2O3 catalysts delivered a CH3OH generation rate of 5.2 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 100 °C via the indirect transformation of CO2 with DMC as a bridge. The ultra-low reaction temperature required for the In2O3-catalyzed indirect CO2 transformation renders it as a promising candidate for industrial CH3OH production.

Method

DFT calculations

All periodic DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP.5.4.4)55,56,57. The exchange-correlation energy was calculated using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional. Valence electrons were described by the plane wave with an energy cutoff of 400 eV, which was selected based on the convergence test results (Supplementary Fig. 28a). Slab separation was provided normal to the surface with a 15 Å vacuum region, which is sufficient to minimize the effects of calculation results (Supplementary Fig. 28b, c)37,56,58,59. Brillouin-zone integrations were performed using a Γ-centered (2 × 2 × 1) k-point mesh.

The DFT-D3 scheme was used to compensate for the long-range van der Waals interactions. The thresholds for converging the electronic wavefunctions and atomic structures are 10−4 eV for the energy and 0.02 eV/Å for the maximal force, respectively. Adsorption energy (Eads) is defined as: Eads = Etotal−Eslab−Eadsorbate, where Etotal and Eslab are the total energies of a surface with adsorbates and a clean surface, respectively. Eadsorbate is the total energy of the free adsorbate.

Preparation of In2O3 catalysts

Typically, 19.2 g of NaOH and 1.203 g of In(NO3)3·5H2O were dissolved in 70 mL and 10 mL of H2O, respectively. Afterward, the In(NO3)3 solution was added to the NaOH solution under vigorous stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, the resulting mixture underwent a hydrothermal reaction at 100 °C for 12 h. After natural cooling, the solids were centrifuged and washed for three times with an alternation of H2O and ethanol. Finally, the solids were dried at 70 °C overnight to obtain the In(OH)3 precursors.

The PC-In2O3 catalysts were synthesized by annealing the In(OH)3 precursors at 250 °C for 2 h (heating rate of 5 °C min−1) under air conditions. The PC-In2O3-350 and PC-In2O3-450 catalysts were prepared using the same protocol but with annealing temperatures of 350 °C or 450 °C, respectively.

The PC-In2O3-H2 catalysts were obtained by annealing PC-In2O3 at 350 °C for 2 h (heating rate of 5 °C min−1) under 10% H2/Ar flow.

Catalytic hydrogenation of DMC

Typically, 5 mL of DMC and 20 mg of catalysts were mixed in a 55 mL autoclave equipped with a pressure detector. The autoclave was purged with H2 for three times, pressurized to 2 MPa with H2, and heated to 100 °C under stirring (400 rpm) for 1 h. After the reaction was completed, the gaseous products were collected in a 0.5 L sampling bag and analyzed using gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a flame ionization detector (FID). Liquid products were analyzed using GC with a FID.

Catalytic indirect transformation of CO2 to CH3OH

Typically, 5 mL of CH3OH and 20 mg of catalysts were mixed in a 55 mL autoclave equipped with a pressure detector, with 1 mmol of dioxane as an internal standard. The autoclave was purged with CO2 and then pressurized to 1.0 MPa of CO2. The reactor was heated to 100 °C under stirring (400 rpm) for 2 h. After reaction, the gas mixture was collected in a 0.5 L sampling bag and analyzed using GC equipped with TCD and FID. Liquid products were analyzed using GC with FID. Subsequently, the reaction system was purged with H2 and pressurized to 2.0 MPa for the DMC hydrogenation at 100 °C. After 0.5 h, the gaseous products were collected in a 0.5 L sampling bag and analyzed using GC with TCD and FID. Liquid products were analyzed by GC with FID.

Data availability

The Source data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source data file. Data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Navarro-Jaén, S. et al. Highlights and challenges in the selective reduction of carbon dioxide to methanol. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 546–579 (2021).

Jiang, X., Nie, X., Guo, X., Song, C. & Chen, J. G. Recent advances in carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol via heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 7984–8034 (2020).

Zhong, J. et al. State of the art and perspectives in heterogeneous catalysis of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1385–1413 (2020).

Kattel, S., Ramírez, P. J., Chen, J. G., Rodriguez, J. A. & Liu, P. Active sites for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on Cu/ZnO catalysts. Science 355, 1296–1299 (2017).

Gao, W. et al. Industrial carbon dioxide capture and utilization: state of the art and future challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 8584–8686 (2020).

Fu, D. & Davis, M. E. Carbon dioxide capture with zeotype materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 9340–9370 (2022).

Burkart, M. D., Hazari, N., Tway, C. L. & Zeitler, E. L. Opportunities and challenges for catalysis in carbon dioxide utilization. ACS Catal. 9, 7937–7956 (2019).

Nielsen, D. U., Hu, X.-M., Daasbjerg, K. & Skrydstrup, T. Chemically and electrochemically catalysed conversion of CO2 to CO with follow-up utilization to value-added chemicals. Nat. Catal. 1, 244–254 (2018).

Amann, P. et al. The state of zinc in methanol synthesis over a Zn/ZnO/Cu(211) model catalyst. Science 376, 603–608 (2022).

Graciani, J. et al. Highly active copper-ceria and copper-ceria-titania catalysts for methanol synthesis from CO2. Science 345, 546–550 (2014).

Behrens, M. et al. The active site of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 industrial catalysts. Science 336, 893–897 (2012).

Goeppert, A., Czaun, M., Jones, J.-P., Prakash, G. K. S. & Olah, G. A. Recycling of carbon dioxide to methanol and derived products—closing the loop. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7995–8048 (2014).

Wang, W., Wang, S., Ma, X. & Gong, J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3703–3727 (2011).

Hu, J. et al. Sulfur vacancy-rich MoS2 as a catalyst for the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Nat. Catal. 4, 242–250 (2021).

Kang, H. et al. Generation of oxide surface patches promoting H-spillover in Ru/(TiOx)MnO catalysts enables CO2 reduction to CO. Nat. Catal. 6, 1062–1072 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Platinum and frustrated Lewis pairs on ceria as dual-active sites for efficient reverse water-gas shift reaction at low temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305661 (2023).

Khoshooei, M. A. et al. An active, stable cubic molybdenum carbide catalyst for the high-temperature reverse water-gas shift reaction. Science 384, 540–546 (2024).

Balaraman, E., Gunanathan, C., Zhang, J., Shimon, L. J. & Milstein, D. Efficient hydrogenation of organic carbonates, carbamates and formates indicates alternative routes to methanol based on CO2 and CO. Nat. Chem. 3, 609–614 (2011).

Dixneuf, P. H. A bridge from CO2 to methanol. Nat. Chem. 3, 578–579 (2011).

Li, L. et al. Atom-economical synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from CO2: engineering reactive frustrated Lewis pairs on ceria with vacancy clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202214490 (2022).

Kumar, A., Janes, T., Espinosa-Jalapa, N. A. & Milstein, D. Manganese catalyzed hydrogenation of organic carbonates to methanol and alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12076–12080 (2018).

Kaithal, A., Holscher, M. & Leitner, W. Catalytic hydrogenation of cyclic carbonates using manganese complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13449–13453 (2018).

Du, X. L., Jiang, Z., Su, D. S. & Wang, J. Q. Research progress on the indirect hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol. ChemSusChem 9, 322–332 (2016).

Zubar, V. et al. Hydrogenation of CO2-derived carbonates and polycarbonates to methanol and diols by metal-ligand cooperative manganese catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13439–13443 (2018).

Tamura, M., Kitanaka, T., Nakagawa, Y. & Tomishige, K. Cu sub-nanoparticles on Cu/CeO2 as an effective catalyst for methanol synthesis from organic carbonate by hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 6, 376–380 (2016).

Lee, W. T., van Muyden, A. P., Bobbink, F. D., Huang, Z. & Dyson, P. J. Indirect CO2 methanation: Hydrogenolysis of cyclic carbonates catalyzed by Ru-modified zeolite produces methane and diols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 557–560 (2019).

Chen, X., Cui, Y., Wen, C., Wang, B. & Dai, W. L. Continuous synthesis of methanol: heterogeneous hydrogenation of ethylene carbonate over Cu/HMS catalysts in a fixed bed reactor system. Chem. Commun. 51, 13776–13778 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over In2O3-based catalysts: From mechanism to catalyst development. ACS Catal. 11, 1406–1423 (2021).

Pinheiro Araújo, T. et al. Flame-made ternary Pd-In2O3-ZrO2 catalyst with enhanced oxygen vacancy generation for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nat. Commun. 13, 5610 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. Strong electronic oxide-support interaction over In2O3/ZrO2 for highly selective CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19523–19531 (2020).

Araujo, T. P. et al. Reaction-induced metal-metal oxide interactions in Pd-In2O3/ZrO2 catalysts drive selective and stable CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306563 (2023).

Ye, J., Liu, C., Mei, D. & Ge, Q. Active oxygen vacancy site for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation on In2O3(110): a DFT study. ACS Catal. 3, 1296–1306 (2013).

Cao, A., Wang, Z., Li, H. & Nørskov, J. K. Relations between surface oxygen vacancies and activity of methanol formation from CO2 hydrogenation over In2O3 surfaces. ACS Catal. 11, 1780–1786 (2021).

Posada-Borbon, A. & Gronbeck, H. Hydrogen adsorption on In2O3(111) and In2O3(110). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 16193–16202 (2020).

Cannizzaro, F., Hensen, E. J. M. & Filot, I. A. W. The promoting role of Ni on In2O3 for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. ACS Catal. 13, 1875–1892 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Understanding surface structures of In2O3 catalysts during CO2 hydrogenation reaction using time-resolved IR, XPS with in situ treatment, and DFT calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 631, 157534 (2023).

Dang, S. et al. Rationally designed indium oxide catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol with high activity and selectivity. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz2060 (2020).

Zachariasen, W. The crystal structure of the modification C of the sesquioxides of the rare earth metals, and of Indium and thallium. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 9, 310–316 (1927).

Cheng, Q. et al. Unraveling the influence of oxygen vacancy concentration on electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to formate over indium oxide catalysts. ACS Catal. 13, 4021–4029 (2023).

Lei, F. et al. Oxygen vacancies confined in ultrathin indium oxide porous sheets for promoted visible-light water splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6826–6829 (2014).

Wang, W. et al. Rational control of oxygen vacancy density in In2O3 to boost methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 14, 9887–9900 (2024).

Sun, Y., Ren, J. & Zhang, S. Breaking the H2 pressure dependence in hydrogenation through interfacial *H reservoirs on Cu–WO3 catalysts. ACS Catal. 15, 14331–14340 (2025).

Posada-Borbón, A., Bosio, N. & Grönbeck, H. On the signatures of oxygen vacancies in O1s core level shifts. Surf. Sci. 705, 121761 (2021).

Idriss, H. On the wrong assignment of the XPS O1s signal at 531–532 eV attributed to oxygen vacancies in photo- and electro-catalysts for water splitting and other materials applications. Surf. Sci. 712, 121894 (2021).

Frankcombe, T. J. & Liu, Y. Interpretation of oxygen 1s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of ZnO. Chem. Mater. 35, 5468–5474 (2023).

Zaki, M. I., Hasan, M. A., Al-Sagheer, F. A. & Pasupulety, L. In situ FTIR spectra of pyridine adsorbed on SiO2–Al2O3, TiO2, ZrO2 and CeO2: general considerations for the identification of acid sites on surfaces of finely divided metal oxides. Colloids Surf. 190, 261–274 (2001).

Hou, G. et al. Dimethyl carbonate synthesis from CO2 over CeO2 with electron-enriched lattice oxygen species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402053 (2024).

Dutta, A., Appel, A. M. & Shaw, W. J. Designing electrochemically reversible H2 oxidation and production catalysts. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 244–252 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. Additive-free, robust H2 production from H2O and DMF by dehydrogenation catalyzed by Cu/Cu2O formed in situ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8245–8249 (2017).

Zhang, C. et al. Mechanistic studies of water electrolysis and hydrogen electro-oxidation on high temperature ceria-based solid oxide electrochemical cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11572–11579 (2013).

Abdelgaid, M. & Mpourmpakis, G. Structure–activity relationships in Lewis acid–base heterogeneous catalysis. ACS Catal. 12, 4268–4289 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Solid frustrated-Lewis-pair catalysts constructed by regulations on surface defects of porous nanorods of CeO2. Nat. Commun. 8, 15266 (2017).

Liu, P. et al. Photochemical route forsynthesizing atomically dispersedpalladium catalysts. Science 352, 797–801 (2016).

Zhang, S., Xia, Z., Zou, Y., Zhang, M. & Qu, Y. Spatial intimacy of binary active-sites for selective sequential hydrogenation-condensation of nitriles into secondary imines. Nat. Commun. 12, 3382 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmiiller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 222–229 (1995).

Shen, C. et al. Highly active Ir/In2O3 catalysts for selective hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol: experimental and theoretical studies. ACS Catal. 11, 4036–4046 (2021).

Zhou, S., Wan, Q., Lin, S. & Guo, H. Acetylene hydrogenation catalyzed by bare and Ni doped CeO2(110): the role of frustrated Lewis pairs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 11295–11304 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515020092) and the key Projects of Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shannxi Province (2024JC-TBZC-16). Y.W. is supported by the Sponsored by Innovation Foundation for Doctor Dissertation of Northwestern Polytechnical University (24GH01020101, CX2024096). This work was also supported by the Joint Fund of Yulin University and the Dalian National Laboratory for Clean Energy(Grant YLU-DNL Fund 2025011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. and Y.Q. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. Y.W. performed most of the experiments. J.R. carried out the DFT calculations. Y.L. contributed to the DFT calculations. Q.G. supervised the experiments using in situ infrared spectroscopy. X.Z. prepared the graphical representations. W.G. contributed to the structural characterization. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Ren, J., Liu, Y. et al. Indirect methanol synthesis from CO2 through high-efficient dimethyl carbonate hydrogenation as a bridge below 100°C. Nat Commun 16, 10588 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65623-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65623-0