Abstract

Hydrogen and carbon concentrations in the Earth’s core are yet known. Here we determined their metal/silicate partition coefficients (D) simultaneously under typical conditions of core formation and found that DH and DC diminish in the presence of carbon and hydrogen, respectively, because of strong interactions between hydrogen and carbon in liquid metal, being markedly different from those separately examined in earlier experiments. With these partitioning data, we investigated the core and bulk Earth abundances of hydrogen and carbon based on core formation scenarios that are compatible with the bulk silicate Earth composition and the mass fraction and density of the core. The modelling results indicate that the Earth building blocks do not match enstatite chondrites in water abundance but require contributions by carbonaceous chondrites. The multi-stage core formation models combined with an Earth accretion scenario accounting for isotopic composition show 0.18–0.49 wt% H and 0.19–1.37 wt% C in the core, leading to 0.53–1.40 wt% H2O (present as H in the core) and 0.07–0.44 wt% C in the bulk Earth. Our modelling also demonstrates that up to 53% and 72% of Earth’s water (hydrogen) and carbon, respectively, could have been derived from non-carbonaceous chondritic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen and carbon are important volatile elements on our planet, and their sources1,2 and the timing3 of the delivery to the growing Earth are of great interest. Since both hydrogen4 and carbon5,6 are known to be strongly siderophile (iron-loving) under high pressure and temperature (P-T), the core is likely to be their largest reservoir. Indeed, the Earth’s outer core exhibits a large density deficit with respect to pure iron7, indicating the presence of substantial amounts of light impurity elements, but the core concentration of each light element has been controversial8. In addition to their bulk silicate Earth (BSE) abundances9,10, understanding the hydrogen and carbon inventories of the core is essential to estimate their bulk Earth contents, which may suggest their origins.

The hydrogen and carbon contents in the core can be constrained by a combination of their metal/silicate partition coefficients under high P-T conditions of core formation and their BSE abundances, including the ocean water. The metal-silicate partitioning of hydrogen has been examined by experiments4 to 60 GPa and 4560 K as well as by theoretical calculations11,12. The partitioning of carbon has been extensively studied below 25 GPa in large-volume presses13,14,15,16,17 and to 71 GPa in pressure and 5200 K in temperature by laser-heated diamond-anvil cell (DAC) techniques5,6. However, these two earlier DAC works reported apparently inconsistent results, although experiments were conducted at similar P-T conditions.

Here, we examined the metal-silicate partitioning of hydrogen and carbon simultaneously in a DAC based on a combination of synchrotron X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements at high pressure and the textural and compositional analyses on recovered samples by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and field-emission-type electron probe microanalyzer (FE-EPMA). With these partitioning data, we modelled the Earth’s accretion and core formation processes that account for the BSE composition and the mass and density deficit of the core, which give core concentrations of hydrogen and carbon and accordingly their bulk Earth abundances. These results suggest that the core is a predominant reservoir for both hydrogen and carbon on Earth. We also found that non-carbonaceous chondritic materials could be an important source of the Earth’s water and carbon.

Results

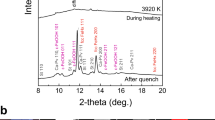

Ten separate melting experiments were performed at 33–56 GPa and 3630–4760 K, corresponding to typical conditions of Earth’s core formation18,19,20 under both hydrous and anhydrous conditions (Table 1). After melting at high pressures, all samples were recovered from a DAC and examined for melting texture and chemical composition on their cross sections at the centre of a heated area (Fig. 1). Quenched liquid metal was found at the central portion, being surrounded by silicate melt. The davemaoite (CaSiO3-perovskite) and SiO2 layers were present outside of the silicate melt pool, which is consistent with the XRD observations during melting (Fig. 2). The further outside, colder region was under subsolidus temperatures.

a Combined X-ray maps of Si (white), Ca (blue), and Fe (red), showing quenched liquid metal, silicate melt, CaSiO3 davemaoite (Dvm,) and the SiO2 phase. b Back-scattered electron (BSE) image. The SCAPS images of secondary ions intensity ratios of H/Si and C/Si. The H and C contents in silicate melt were determined from the regions of interest (ROIs, enclosed by black lines in (c, d)) in an area free from the lens-flare effects of the secondary ion optics (see Supplementary Fig. 16 and “Methods”) and metal blobs (see the BSE image in (b)). A quenched metal portion in (c) and (d) is from the X-ray map in (a). Note that a, c/d, and b are slightly different cross sections because of sputtering by the SIMS ion beam and repolishing with a focused ion beam in between. Scale bar, 10 µm.

They were collected before (a), during (b) and after heating (c) to 3940 K at 42 GPa in run #1. During heating, XRD peaks were observed only from Dvm and CaCl2-type SiO2 (Ct), which were present outside of a silicate melt pool (see Fig. 1a), indicating the melting of both metal and silicate. After quenching temperature, the peaks from fcc FeHx, ɛ-FeOOH, and (FeHx)7C3 appeared. The amount of hydrogen in liquid metal was estimated from the phase proportion and hydrogen concentrations in these quench crystals. See text for details.

Partitioning of hydrogen

The metal/silicate partition coefficients of hydrogen, \({D}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}/{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}\) were obtained as:

where \({x^{\prime} }_{{{{\rm{H}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\) and \({x}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{0.5}}^{{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}\) represent the molar fractions of hydrogen in metal and silicate, respectively (see Eq. 10 for \({x^{\prime} }_{i}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\) in “Methods”). The \({D}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}}\) values obtained in this study in the presence of carbon ranged from 0.7 to 26.1 (Table 1), notably lower than the \({D}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}/{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}\) = 22–46 measured in a carbon-poor system by previous DAC experiments4.

The metal-silicate partitioning of hydrogen can be expressed as a chemical reaction:

The exchange coefficient KD for this reaction is parameterized as functions of P and T with regression constants a, b, c and d:

in which \({x^{\prime} }_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\) is the molar fraction of carbon in liquid metal (Eq. 10), and \(d\cdot {\log }_{10}\left(1-{x^{\prime} }_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\right)\) approximates a non-ideal interaction between H and C5,21. Following previous studies4,22, oxygen fugacity fO2 relative to the iron-wüstite (IW) buffer is approximated as \(\Delta {{{\rm{IW}}}}\approx 2{\log }_{10}\left({x}_{{{{\rm{FeO}}}}}^{{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}/{x^{\prime} }_{{{{\rm{Fe}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\right)\), which was obtained from the EPMA analyses. Fitting Eq. 3 to the present and earlier data4 yields a = 2.31(20), b = −1542(500), c = −38.9(78) and d = 6.69(30). Fig. 3a shows the negative pressure and positive temperature dependence of KD for the partitioning of hydrogen after correcting for the effect of carbon, consistent with the results of Tagawa et al4. We note that carbon in liquid metal strongly reduces \({D}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}/{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}\) (Fig. 3b). All of the experimental data obtained in this study and Tagawa et al4. are well reproduced by Eq. 3 (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

a Pressure and temperature dependence of the exchange coefficient KD for metal-silicate partitioning of hydrogen after correcting for the effect of carbon (Eq. 3). Blue (3000 K), purple (3500 K), orange (4000 K), and yellow lines (5000 K) show isotherms. b Reduction in metal/silicate partition coefficient D of hydrogen (molar basis) as a function of carbon concentration in liquid metal. Circles, this study; triangles, Tagawa et al4. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Partitioning of carbon

Similarly, the metal/silicate partition coefficients for carbon \({D}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}/{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}\) were also calculated as:

The DC ranged from 14 to 369 in the hydrogen (water)-free system and from 27 to 132 in the hydrogen (water)-bearing system (Table 1). We fitted the following equation to the present results combined with earlier DAC data5,6 and low P-T data obtained for silicate melts with the ratio of nonbridging oxygens to tetrahedrally coordinated cations (nbo/t) less than 10 from multi-anvil and piston-cylinder experiments13,14,15,17 that were performed in carbon-undersaturated systems:

in which ΔIW represents oxygen fugacity relative to the iron-wüstite buffer. The fitting provides a = 1.51(30), b = −0.68(15), c = −0.33(7), and d = 1.76(77), showing the strong negative effects of oxygen fugacity, nbo/t, and hydrogen concentration in liquid metal on DC (see Fig. 4a–c, respectively). Note that metal compositions were calculated as \({x^{\prime} }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\) also for the previous experimental data.

Partition coefficient D of carbon (molar basis) as a function of ΔIW (a) and nbo/t (b) obtained in hydrogen-free experiments and of hydrogen concentration in metal (c). See Eq. 5. Colour indicates temperature. Circles, this study; squares, Blanchard et al6. (closed) and Fischer et al5. (open); triangles, Fichtner et al17. (normal) and Dasgupta et al13. (inverted); crosses, Kuwahara et al14,15. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Considering the effects of oxygen fugacity and nbo/t, all of these earlier experimental data are well reproduced by Eq. 5 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The P and T dependence of DC is not explicit in Eq. 5 unlike previous DAC studies5,6 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The low P-T data used together with the high P-T DAC data are key to clarifying such P and T effects; in contrast to earlier DAC studies5,6, we did not employ data obtained in a graphite capsule, which causes carbon saturation in silicate melts, since saturation changes the partitioning behaviours14,15. Li et al.16 also did not find the P and T effects on DC when ΔIW < −1.5. In addition, it has been reported14,16 that the solubilities of carbon in metallic liquid and silicate melt do not depend on pressure. Since the chemical potential of C in a carbon-saturated phase is identical to that in graphite/diamond, it suggests that the pressure dependence of chemical potentials of C is similar among these molten phases and graphite/diamond, and therefore the molar volumes of C in metallic liquid and silicate melt are close to each other, supporting the small pressure dependence of DC (i.e., small volume change in the reaction).

Discussion

Single-stage core formation model

The single-stage core formation model is conceptually simple, assuming that the entire core and mantle reached chemical equilibrium under a certain P, T, and fO2 condition. Such a condition has been estimated, based on the metal-silicate partitioning of moderately siderophile elements, to be 40 GPa and 3750 K (ref. 18), 50 GPa and 3500 K (ref. 19), or 54 GPa and 3350 K (ref. 20) (Supplementary Table 1), and ΔIW = −2.3. The BSE water abundance may be 710 ppm23, including 1.6 × 1024 g water in the crust, ocean, and atmosphere24, while the higher BSE water contents of 1760 ppm and 1070 ppm H2O have also been proposed25,26. On the other hand, the carbon abundance in the BSE may be 120 ppm27, 140 ppm23 or ~160 ppm (or ~220 ppm)28.

Based on the 710 ppm H2O (ref. 23) and 120 ppm C (ref. 27) in the BSE, we can calculate core concentrations of hydrogen and carbon by using DH and DC at the conditions of core-mantle chemical equilibrium (core formation). Following the single-stage core formation model proposed by Wade and Wood18, Eqs. 3 and 5 showed 0.68 wt% H and 0.75 wt% C in the core with DH = 92 and DC = 67 (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 1), in which we employed nbo/t = 2.75 that is for a pyrolitic mantle composition29, fixed the S content to be 2 wt% in the core from cosmochemical and geochemical constraints27 and calculated the core abundances of Si and O using their metal-silicate partitioning data18. Also, similar calculations based on other core formation model19, including the metal/silicate partition coefficients of Si and O, found 0.45 wt% H and 1.15 wt% C in the core (DH = 56 and DC = 96) (Supplementary Table 1). The Fischer et al.'s20 model provides 0.35 wt% H and 1.29 wt% C with DH = 44 and DC = 107.

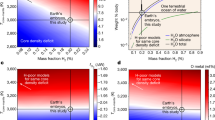

Hydrogen (water) and carbon concentrations in the core (a) and the bulk Earth (b) considering the P-T conditions of core metal segregation at 40 GPa and 3750 K18, 50 GPa and 3500 K19, and 54 GPa and 3350 K20. Black circles, calculated using DH and DC simultaneously determined in this study; diamonds, DH from Tagawa et al.4 and DC from Blanchard et al.6; squares, DH from Tagawa et al.4 and DC from Fischer et al.5 Red and blue regions in b indicate H2O and C concentrations in non-carbonaceous and carbonaceous chondrites, respectively. See Supplementary Table 8 for the H2O and C contents in each type of chondrite.

These results suggest that the core is a primary reservoir for both hydrogen and carbon; >98% and >97% of their bulk Earth budgets may be present in the core, respectively. We also note that when we employ the separately-determined DH (ref. 4) and DC values5,6 without considering the strong interaction between hydrogen and carbon, the C content in the core is calculated to be much higher6 or lower5 than described above, while H concentration is similar (Fig. 5a). Such core abundances indicate 1.10–2.08 wt% H2O and 0.26–0.44 wt% C in the bulk Earth (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table 1), which corresponds to Earth’s building blocks if we do not consider volatile loss during accretion.

Homogeneous accretion & multi-stage core formation model

The multi-stage core formation models may be more realistic scenarios in which the core grows stepwise during the Earth accretion3. Here we employ all of the nine multi-stage core formation models reported by Tagawa et al.4, where the Earth grows by 1000 steps upon accretion of impactors that are identical in size and composition. These models explain ~700 ppm H2O in the BSE, including the ocean water and the mantle FeO, NiO and CoO contents based on their metal/silicate partition coefficients3,19,20,30, as well as the Earth’s core mass fraction. In this study, we additionally examine the distributions of carbon with the newly determined DH and DC that consider the effect of their strong interactions (Eqs. 3 and 5).

We explored impactor H2O and C concentrations, which lead to the amounts of residual water and carbon in silicate being both within the range of existing estimates of the present-day BSE concentrations of 710–1760 ppm H2O (refs. 23,24,25,26) and 120–220 ppm C (refs. 23,27,28) at the end of accretion. The total difference in mantle concentrations of FeO, NiO and CoO (ref. 31) and core mass fraction between the modelling results and the target values is defined as:

We suppose that a model explains the core size and the BSE composition reasonably well when σ < 10. Each model (S1–S3, F1–F3 and R1–R3 models)4 gives the specific P-T evolution of metal-silicate chemical equilibrium, impactor size (=the Earth size divided by N × 1000), impactor bulk (silicate + core) composition (Supplementary Table 2) and exchange coefficients for Ni, Co, O and Si. Here we fixed ΦFe (metallic Fe/total Fe) = 0.987 and ΦSi (metallic Si/total Si) = 0.034, unlike Tagawa et al4.’s simulations, by considering the core-mantle partitioning of O and Si in an enstatite-chondrite-like impactor32 at 1 bar and 2023 K (ref. 29) using their partition coefficients30.

We searched for the sets of Pfinal (the pressure of core metal segregation at the final step of accretion) and impactor water and carbon concentrations, which minimize the σ value (Eq. 6) while satisfying the residual 710–1760 ppm H2O and 120–220 ppm C in the BSE. For each of the nine models, we found a σ minimum with specific Pfinal (Supplementary Fig. 3). With such Pfinal values, the present homogeneous multi-stage core formation models show that accreting identical impactors with 0.2–2.4 wt% H2O and 0.2–1.0 wt% C accounts for the BSE composition (FeO, NiO, CoO, H2O and C contents) and the Earth’s core size (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 4); typical examples of their evolutions during accretion are given in Supplementary Fig. 5. However, the total amount of light impurity elements in the core at the end of the Earth accretion (the calculated core concentrations of H, C, Si and O + assumed 2 wt% S, see Supplementary Fig. 5) are more than required to explain the present-day outer core density deficit33 (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 4) even when the temperature at the inner core boundary (ICB) is relatively low (TICB = 4800 K) and the core liquid is saturated with Si + O under corresponding 3500 K at the core-mantle boundary34 (note that low TICB and the SiO2 crystallization from the liquid core leave relatively large room for hydrogen and carbon). It is therefore unlikely from the present modelling that the Earth’s building blocks included water and carbon from the beginning of accretion.

The delivery of water and carbon to the Earth is considered from the beginning (a) and only after 50% accretion (b). The coloured region in the left panels indicates H2O and C concentrations in impactors, explaining the BSE abundances of 710–1760 ppm H2O and 120–220 ppm C in addition to the core mass fraction and the mantle FeO, Ni and Co contents (colour indicates the deviation from target values). Those in the central panels show the corresponding H and C contents in the core, which are compared with H and C concentrations required to explain the outer core density deficit when TICB = 5400 K (green curve) and 4800 K (right blue curve) (see text). The H2O and C abundances in impactors (=Earth building blocks) are compared to those in non-carbonaceous (red region) and carbonaceous chondrites (blue region) in the right panels.

Next, we examined alternative scenarios in which water and carbon were delivered in a late stage of the Earth's accretion. Such a late delivery of volatiles has been considered for sulphur in a previous multi-stage core formation model35,36,37. In the case of their delivery after 50% accretion (Supplementary Figs. 6–8), the calculated total amount of the core light elements (0.1–0.6 wt% H, 0.1–1.5 wt% C, Si and O contents and assumed S abundance) explains the present-day core density deficit when TICB is between 5400 K and 4800 K, taking the Si + O saturation and resulting SiO2 crystallization upon core cooling into account34 (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 7). These models require >1 wt% H2O and <1 wt% C in the impactors during the latter half of the accretion in most models. Their typical evolutions are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 8 for the S1 model showing relatively small σ values when the volatile-rich latter half impactors include 2.0 wt% H2O and 0.4 wt% C (leading to 1.0 wt% H2O and 0.2 wt% C in the bulk Earth) (Supplementary Table 3). This specific scenario finds 0.35 wt% H and 0.62 wt% C in the core, indicating that >95% of the bulk Earth budgets of both hydrogen and carbon may be present in the core.

Heterogeneous accretion & multi-stage core formation model

It is highly likely that the Earth was formed from a variety of different types of chondritic materials. Indeed, isotopic compositions, in particular Mo (ref. 38), Ru (ref. 39) and Zr isotopes40, suggest that the Earth’s building blocks are close to enstatite (E)-chondrite-type materials but involve some carbonaceous chondrites (CCs) that are classified into CI, CM, CR, CO and CV (Supplementary Table 8). The recent isotopic mixing model by Dauphas et al. 41 proposed accretion scenarios to account for the Earth’s isotopic composition, showing the proportions and delivery timing of E-, CI-, and minor amounts of ordinary (O) chondrites (H, L, and LL) and other carbonaceous (CO + CV) chondrites. Their 4-stage model argued that water- and carbon-rich CC-type materials accreted to our planet mainly in the last 25% accretion, broadly consistent with our modelling described above. Here, the Dauphas et al.'s41 4-stage accretion scenario was combined with our multi-stage core formation model (model S14 in the previous section) such that the model is constrained not only by the BSE elemental composition and the core mass and density deficit but also by the isotopic composition. Furthermore, we also examined the effects of impactor size that changes the efficiency of chemical equilibrium between impactor metal and proto-Earth silicate4,42 (by varying the number of steps for Earth accretion, N × 1000), differentiation of impactors before accreting to the Earth (by including volatile-free impactors with a frequency of 1-1/n) and volatile loss on Earth.

Considering the wide ranges of 1) the reported H2O and C contents in E- and CI-chondrite-type materials2,43,44,45,46,47 (Fig. 7d, e, Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Fig. 9), 2) N = 1–10 (Supplementary Fig. 10) and 3) n = 1–8 (Supplementary Fig. 11) along with 4) none or 25% carbon loss throughout the Earth accretion (water/hydrogen loss may have been minor)48,49, we looked for the sets of these parameters that find σ < 10 through the search for Pfinal and 710–1760 ppm H2O and 120–220 ppm C in the BSE. Consequently, these modellings show 0.18–0.49 wt% H and 0.19–1.37 wt% C in the core (Fig. 7a). Such core concentrations give 0.53–1.40 wt% H2O (present as H in the core) and 0.07–0.44 wt% C in the bulk Earth (Fig. 7d). We note that these ranges of the core and bulk Earth H (H2O) and C contents are similar to those obtained by the homogeneous accretion & multi-stage core formation modelling shown above that is based on the model S1 same as here and considers the delivery of water and carbon only after 50% accretion (Fig. 6b). In addition, in almost all cases, the parameter sets that satisfy the BSE composition and the Earth’s core size (σ < 10) provide the total amount of the core light elements accounting for the core density deficit with TICB = 4800–5400 K.

Water and carbon are delivered according to the 4-stage accretion scenario by Dauphas et al.41 that explains Earth’s isotopic composition. a–c Modelling results on core H and C concentrations (circles, n = 1; squares, 1 < n < 2; triangles, 2 < n < 3). Colours indicate difference from target values (σ) (a) and the fraction of NC-type materials as sources for Earth’s water (b) and carbon (c). d, e The bulk Earth H2O (present as H in the core) and C abundances compared to those in each type of chondrite (Supplementary Table 8), including the Ryugu71 and Bennu72 samples. The dependence on n is indicated by colour. Closed and open symbols consider none and 25% loss of carbon during Earth accretion, respectively. Diamonds and squares show the variations in H2O and C concentrations in E-/CI-type materials (varied in each model) and other types (fixed), respectively, employed in our modelling, while the reported ranges of the H2O and C contents for NC and CC materials are indicated by boxes with broken and dotted lines, respectively.

The 0.19–1.37 wt% C in the core obtained in these simulations is higher than the core C concentrations of ~0.1–0.2 wt% reported by Blanchard et al.6 and Fischer et al.5, in which the effect of hydrogen on DC was not taken into account. It is because the C abundance in the core is almost independent of the DC in the Blanchard et al.'s6 model although they used a higher DC. The DC utilized in the modelling by Fischer et al.5 is the extrapolated one and lower than that applied in this study. Note that the present parameterization of DC is consistent with the experimental data by Fischer et al.5 but employs more data including those by Blanchard et al.6 and this study. In addition, some recent simulations48,49 included atmosphere as an additional reservoir, which is important in particular for C, but it reduces the calculated core H and C contents only by less than ~5% in the present modelling (Supplementary Fig. 12) since impactor metal reaches chemical equilibrium with a limited portion of an existing magma ocean42. Indeed, the Earth accretion and concurrent core formation must have been complicated processes, for which too few constraints are available so far. The present modelling of core composition employed the BSE isotopic composition and the core density deficit as additional constraints, neither of which has been used in earlier simulations. It is noted, however, that the possible ranges of the core H and C abundances demonstrated in this study are still dependent on model assumptions such as the limited efficiency4 of chemical equilibrium between impactor metal and proto-Earth silicate. This assumes that upon each impact, the timescale of the metal migration to the core is shorter than that of the compositional homogenization of the entire magma ocean42.

Origins of Earth’s water and carbon

All of these modellings show that the bulk Earth H2O (incorporated as H in the core) abundance is higher than that of E-chondrites—in other words, E-chondrites alone cannot be the source of Earth’s water (Figs. 5b, 6b and 7d). Furthermore, the heterogeneous multi-stage core formation models show that 1 to 53% of Earth’s water may have derived from the non-carbonaceous (NC)-type materials (E- + O-chondrites) and the rest was from the CC-type ones that constitute 7% of the total Earth building blocks41 (Fig. 7b). Also, 2 to 72% of the Earth’s carbon could have originated from the NC-type materials with/without taking 25% loss during accretion into account48,49 (Fig. 7c), strongly depending on carbon concentration in E-chondrites. We also note that 3–10% and 3–24% of the BSE H2O and C budgets, respectively, were derived by the late veneer, the additional 0.5% accretion after the core formation41. It suggests that the majority of Earth’s hydrogen and carbon were involved in metal-silicate partitioning, which causes isotopic fractionation, leaving their isotopic ratios in the BSE different from those of the bulk Earth and Earth building blocks.

Methods

High-pressure melting experiments

Laser-heated DAC techniques were used to generate high P-T conditions (Table 1). We prepared five different glasses for silicate starting materials, which have mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) compositions with various amounts of H2O; 1.0 wt% (w01), 0.15 wt% (w02), 0.6 wt% (w03), and none (n01 and n02) (Supplementary Table 4). A thin foil (~7 µm thick) of iron containing 4.0 wt% carbon, same as that employed previously50, was sandwiched between layers of silicate glass. They were loaded into a 120 µm hole at the centre of a pre-indented rhenium gasket. Diamond anvils with a flat 300 µm culet were used. After loading, for experiments with anhydrous glass starting materials, we put the DAC into a vacuum oven at 400 K for >12 hours to remove moisture on the sample and subsequently compressed the sample in an argon atmosphere to avoid water adsorption. Under high pressure of interest, the sample was heated from both sides with a couple of 100 W single-mode Yb fibre lasers at BL10XU, SPring-8 synchrotron radiation source, with in-situ XRD measurements51. XRD patterns were collected before/during/after heating using a monochromatic X-ray beam with an energy of ~30 keV that was focused to a 6 µm area (full width of half maximum) on the sample position. Melting of a sample was confirmed by the disappearance of XRD peaks except weak ones that derived from silicate liquidus phases outside of a silicate melt pool (Fig. 2). Heating duration ranged from 4 to 60 seconds, which is long enough for each element to diffuse in liquid metal52 and silicate melt53. Indeed, both metal and silicate were found to be homogeneous in composition in this study, except for heterogeneous distributions of small metallic blobs in the silicate melt pool (Fig. 1b). It has been demonstrated by earlier experiments using a multi-anvil press that molten metal and silicate melt reached chemical equilibrium in such a heating time scale54. Considering the much smaller sample size and higher temperatures in the present DAC study than in the multi-anvil experiments, the time necessary for chemical equilibration should be shorter. Temperature was measured by a spectro-radiometric method51. Pressure was measured based on the Raman shift of a diamond anvil at 300 K after heating55 and corrected for thermal pressure contributions that have been estimated to be +2.5 GPa per 1000 K (refs. 4,56). The errors in pressure and temperature may be ±10% and ±5%, respectively57.

XRD and EPMA analyses of liquid metal

The hydrogen contents in liquid iron were estimated from XRD data collected at high pressures and 300 K, since the iron sample loses hydrogen when it transforms into the body-centred cubic structure4,58. The XRD patterns showed the appearance of face-centred-cubic (fcc) FeHx and hydrogen-bearing (FeHx)7C3 [or (FeHx)3C] formed from liquid metal upon quenching temperature (Fig. 2c). Their lattice volumes were larger than those of pure fcc Fe and Fe7C3 (or Fe3C) at equivalent pressure and 300 K, respectively59,60,61, which is attributed to the incorporation of hydrogen into their interstitial sites. Following Tagawa et al4., the hydrogen content x was calculated as:

where VFeHx, V(FeHx)7C3 and V(FeHx)3C represent the observed lattice volume per Fe atom of each phase, and VFe, VFe7C3 and VFe3C are from their equations of state59,60,61. ΔVH represents the volume increase per hydrogen atom. We employed ΔVH_Fe previously reported for fcc Fe62. ΔVH_Fe7C3 was determined by first-principles calculations in this study (see below for the first-principles calculations section, Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 13). Since hydrogen favours different interstitial sites depending on hydrogen concentration, we calculated x in (FeHx)7C3 based on three different ΔVH_Fe7C3 applicable to each hydrogen concentration range, x < 0.14, 0.14< x < 0.29 and 0.29 < x < 0.57 (Supplementary Table 6). We also found that ΔVH is similar between Fe and Fe7C3, in particular x = 0.22 and 0.45 observed in (FeHx)3C at 45–47 GPa and 300 K (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 13), and therefore used ΔVH_Fe7C3 to calculate x in (FeHx)3C. In all runs, fcc FeHx, ɛ-FeOOH and (FeHx)7C3 [or (FeHx)3C] were found in XRD patterns collected from temperature-quenched liquid. Their hydrogen concentrations x were estimated to be 0.03–1.76, 0.21–0.30, and 0.22–0.45, respectively (Supplementary Table 6). We then calculated the total hydrogen concentration in liquid to be 0.33 to 0.98 wt% (Supplementary Table 7) based on the proportions of these crystals in quenched liquid, which were obtained by mass balance calculations using the FE-EPMA analyses (see below), considering the presence of silicon in the iron site. The incorporation of silicon into Fe increases its unit-cell volume to a minor extent63. While 0.16–6.47 wt% Si may be present in these iron and iron carbides in the present experiments (Supplementary Table 7), the estimate of the hydrogen content x is reduced by 0.02 at 50 GPa even when 5.9 wt% Si is included63.

The carbon contents in quenched metal liquids were obtained based on the electron microprobe analyses on the cross sections of recovered samples. After recovering samples at ambient conditions, sample cross sections at the centre of a laser-heated spot were prepared parallel to the compression/laser-heating axis with a focused ion beam (FIB, Versa 3DTM, FEI). Textural and chemical characterizations were made with an FE-type scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Gold coating was made. We found 3.04–9.51 wt% C in quenched liquid metal along with other major elements with an FE-EPMA (JXA-8530F, JEOL) (Supplementary Table 7). At least five different points were measured for each phase. We employed an acceleration voltage of 12 kV, beam current of 15 nA, and LIF (Fe), TAP (Al, Na), TAPH (Mg), LDE1 (O), LDE2H (C), and PETJ (K, Ca, Si, Ti) as analyzing crystals. The calibration curve for C was obtained with Fe3C, Fe-0.84 wt% C (JSS066-6, the Japan Iron and Steel Federation), and a rhenium gasket (assumed to be free of carbon) (Supplementary Fig. 14). Fe, Al2O3, MgO, Si, SiO2, TiO2, CaSiO3, KTiOPO4, and NaAlSi3O8 were used as standards for other elements. The X-ray counting time for peak/background was 20/10 seconds. The ZAF correction was applied. The major element compositions of silicate melt and the silicate starting materials were also obtained with an FE-EPMA (Supplementary Table 4).

SIMS measurements of silicate melt

We determined the hydrogen (water) and carbon contents in quenched silicate melts with SIMS equipped with a two-dimensional ion detector, stacked CMOS-type active pixel sensor (SCAPS) at the Hokkaido University4,64,65,66,67 (Fig. 1c, d). This system provides quantitative maps of secondary ions emitted from the sample surface because the CMOS sensor exhibits a good linear relationship between an output voltage and the number of secondary ions66. Therefore, the abundance of each element from the intensity map can be quantified. The sample cross sections were coated with a ~70 nm thick Au layer by plasma sputtering to compensate for electrostatic charging on the sample surface. We used the Cs+ primary beam rastered across a 100 μm × 100 μm region on the sample. In order to prevent the effect of electrical charging, analyses were performed while applying electrons with an electron gun. A contrast aperture was set to be 100 μm in diameter, the exit slit was opened fully for 1H- and 750 μm for others. Pressure during measurement was 2 × 10-7 Pa. The SCAPS images of 1H-, 12C-, and 28Si- secondary ions were collected. Accumulation time was 150, 100, and 10 seconds in each image, respectively. We employed five silicate glasses with known H2O and C concentrations as standards (0.0 to 1.8 wt%, 0.0 to 389 ppm, respectively)68 and prepared an additional silicate glass standard that contains 1.3 wt% C to fully cover the range of C concentration in silicate melt in the present experiments. Based on these standard glass analyses, we converted intensity ratios, 1H-/28Si- and 12C-/28Si- into mass ratios. The intensity ratios from the secondary ion images are linearly correlated with the mass ratios of H/Si or C/Si of these standards (correlation coefficient R2 = 0.997 and 1.000, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15). Water (hydrogen) or carbon concentration in silicate melt was then obtained by multiplying the H/Si or C/Si ratio by the Si content acquired by FE-EPMA. While the silicate melt in run #1 included H2O much more than 1.8 wt% in the standard glass, each parameter in Eq. 3 for DH does not change beyond uncertainty when excluding the data from run #1.

Hydrogen distributions were homogeneous in quenched silicate melt (Supplementary Fig. 16), suggesting that hydrogen did not migrate from liquid metal to surrounding silicate upon quenching temperature. The 12C- intensities from metal were higher by more than two orders of magnitude than those from silicate melt (Supplementary Fig. 16). The high C intensity from the metal leaked into the surrounding silicate melt due to the lens-flare or aberration effect. Therefore, the regions of interest (ROIs) in the silicate melts, from which we obtained their hydrogen and carbon abundances, were chosen from an area free from such flare effect from the metal based on the 2D map and line profile of the log10(C) values (Supplementary Fig. 16). In addition, we avoided an area where small metallic blobs are present in the silicate melt. As shown in a back-scattered electron image (Fig. 1b), the outer part of a silicate melt layer is free from the metallic blobs. Following the arguments made in the earlier experiments on metal-silicate partitioning of carbon by Blanchard et al.6, we interpret that such blobs are not quench products but were present during melting. Indeed, the back-scattered electron image given in Fig. 1b does not show the Fe depletion in areas next to the blobs, which supports that they were not formed from silicate melt upon quenching. The SIMS analyses demonstrate that the amounts of H2O widely ranged from 0.11 to 10.78 wt% in silicate melts (Supplementary Table 4). Their carbon contents were found to be 0.02–0.60 wt% and 0.008–0.44 wt% when using hydrous and anhydrous silicate starting materials, respectively.

Activities of elements in (H, C)-rich metal and oxygen fugacity

Liquid metals found in this study included carbon (and hydrogen in experiments using H2O-bearing starting materials). The presence of hydrogen and carbon decreases the molar fraction of iron in metal (\({x}_{{{{\rm{Fe}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\)), which apparently increases the oxygen fugacity relative to iron-wüstite (IW) buffer, \(\Delta {{{\rm{IW}}}} \sim 2\,{\log }_{10}\left({x}_{{{{\rm{FeO}}}}}^{{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}/{x}_{{{{\rm{Fe}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}\right)\) and changes the exchange coefficient \({K}_{{{{\rm{D}}}}}^{{{{\rm{O}}}}}={x}_{{{{\rm{Fe}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}{x}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{{{{\rm{metal}}}}}/{x}_{{{{\rm{FeO}}}}}^{{{{\rm{silicate}}}}}\) for the reaction FeOsilicate = Femetal + Ometal. According to Tagawa et al.4, the \({K}_{{{{\rm{D}}}}}^{{{{\rm{O}}}}}\) values calculated without considering the presence of hydrogen and carbon are consistent with those obtained in the (H, C)-free system. It suggests that both hydrogen and carbon do not have colligative properties in iron solvent since small H and C atoms are incorporated into liquid Fe interstitially. Therefore, the activity of element i in metal is approximated as;

We obtained the mol-based D values from earlier experimental data with the same procedure.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations based on density functional theory were performed using the Quantum Espresso (QE) codes69. Generalized-gradient approximation70 was adopted, along with projector-augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials available on the QE website (energy cutoff of 90 Ry). In our calculations, Fe7C3 (20-atom cells, P63mc symmetry) with various site occupations of H were considered, including Wyckoff positions 2a, 2b, 6c, and 12 d. All considered structures are fully optimized (4×4×6 k-point mesh), and the results are fitted to the 3rd-order Birch–Murnaghan equation of state (Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Fig. 13). For all considered structures, the ferromagnetic (FM) state is more favourable than the nonmagnetic (NM) state. As the H concentration increases, the favourable site occupations are 2a, 2a + 2b, and 2a + 6c for Fe7C3H, Fe7C3H2, and Fe7C3H4, respectively.

Data availability

The data to reproduce this paper is provided through https://zenodo.org/records/17357322. Any other original data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The codes to reproduce this paper are available at Code Ocean (https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.5580780.v1).

References

Alexander, C. M. O. et al. The provenances of asteroids, and their contributions to the volatile inventories of the terrestrial planets. Science 337, 721–723 (2012).

Piani, L. et al. Earth’s water may have been inherited from material similar to enstatite chondrite meteorites. Science 369, 1110–1113 (2020).

Rubie, D. C. et al. Accretion and differentiation of the terrestrial planets with implications for the compositions of early-formed Solar System bodies and accretion of water. Icarus 248, 89–108 (2015).

Tagawa, S. et al. Experimental evidence for hydrogen incorporation into Earth’s core. Nat. Commun. 12, 2588 (2021).

Fischer, R. A., Cottrell, E., Hauri, E., Lee, K. K. M. & Le Voyer, M. The carbon content of Earth and its core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8743–8749 (2020).

Blanchard, I. et al. The metal–silicate partitioning of carbon during Earth’s accretion and its distribution in the early solar system. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 580, 117374 (2022).

Kuwayama, Y. et al. Equation of state of liquid iron under extreme conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 165701 (2020).

Hirose, K., Wood, B. & Vočadlo, L. Light elements in the Earth’s core. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 645–658 (2021).

Marty, B. The origins and concentrations of water, carbon, nitrogen and noble gases on Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 313-314, 56–66 (2012).

Hirschmann, M. M. Constraints on the early delivery and fractionation of Earth’s major volatiles from C/H, C/N, and C/S ratios. Am. Miner. 101, 540–553 (2016).

Li, Y., Vočadlo, L., Sun, T. & Brodholt, J. P. The Earth’s core as a reservoir of water. Nat. Geosci. 13, 453–458 (2020).

Yuan, L. & Steinle-Neumann, G. Strong sequestration of hydrogen into the Earth’s core during planetary differentiation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088303 (2020).

Dasgupta, R., Chi, H., Shimizu, N., Buono, A. S. & Walker, D. Carbon solution and partitioning between metallic and silicate melts in a shallow magma ocean: implications for the origin and distribution of terrestrial carbon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 102, 191–212 (2013).

Kuwahara, H., Itoh, S., Suzumura, A., Nakada, R. & Irifune, T. Nearly carbon-saturated magma oceans in planetary embryos during core formation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092389 (2021).

Kuwahara, H., Itoh, S., Nakada, R. & Irifune, T. The effects of carbon concentration and silicate composition on the metal-silicate partitioning of carbon in a shallow magma ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9422–9429 (2019).

Li, Y., Dasgupta, R., Tsuno, K., Monteleone, B. & Shimizu, N. Carbon and sulfur budget of the silicate Earth explained by accretion of differentiated planetary embryos. Nat. Geosci. 9, 781–785 (2016).

Fichtner, C. E., Schmidt, M. W., Liebske, C., Bouvier, A.-S. & Baumgartner, L. P. Carbon partitioning between metal and silicate melts during Earth accretion. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 554, 116659 (2021).

Wade, J. & Wood, B. J. Core formation and the oxidation state of the Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 236, 78–95 (2005).

Siebert, J., Badro, J., Antonangeli, D. & Ryerson, F. J. Metal–silicate partitioning of Ni and Co in a deep magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 321, 189–197 (2012).

Fischer, R. A. et al. High pressure metal–silicate partitioning of Ni, Co, V, Cr, Si, and O. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 167, 177–194 (2015).

Ma, Z. Thermodynamic description for concentrated metallic solutions using interaction parameters. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 32, 87–103 (2001).

Siebert, J., Corgne, A. & Ryerson, F. J. Systematics of metal–silicate partitioning for many siderophile elements applied to Earth’s core formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 75, 1451–1489 (2011).

Hirschmann, M. M. Comparative deep Earth volatile cycles: the case for C recycling from exosphere/mantle fractionation of major (H2O, C, N) volatiles and from H2O/Ce, CO2/Ba, and CO2/Nb exosphere ratios. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 502, 262–273 (2018).

Lécuyer, C., Gillet, P. & Robert, F. The hydrogen isotope composition of seawater and the global water cycle. Chem. Geol. 145, 249–261 (1998).

Peslier, A. H., Schönbächler, M., Busemann, H. & Karato, S.-I. Water in the Earth’s interior: distribution and origin. Space Sci. Rev. 212, 1–68 (2017).

Palme, H. & O’Neill, H. S. C. Cosmochemical estimates of mantle composition. In Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn, Vol. 3 (eds. Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 1–39 (Elsevier, 2014).

McDonough, W. F. Compositional model for the Earth’s core. In Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn, Vol. 3 (eds. Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 559–577 (Elsevier, 2014).

Marty, B. et al. An evaluation of the C/N ratio of the mantle from natural CO2-rich gas analysis: geochemical and cosmochemical implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 551, 116574 (2020).

Takahashi, E. Melting of a dry peridotite KLB-1 up to 14 GPa: implications on the origin of peridotitic upper mantle. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 9367–9382 (1986).

Siebert, J., Badro, J., Antonangeli, D. & Ryerson, F. J. Terrestrial accretion under oxidizing conditions. Science 339, 1194–1197 (2013).

Wang, H. S., Lineweaver, C. H. & Ireland, T. R. The elemental abundances (with uncertainties) of the most Earth-like planet. Icarus 299, 460–474 (2018).

Javoy, M. et al. The chemical composition of the Earth: enstatite chondrite models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 293, 259–268 (2010).

Umemoto, K. & Hirose, K. Chemical compositions of the outer core examined by first principles calculations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 531, 116009 (2020).

Hirose, K. et al. Crystallization of silicon dioxide and compositional evolution of the Earth’s core. Nature 543, 99–102 (2017).

Suer, T.-A., Siebert, J., Remusat, L., Menguy, N. & Fiquet, G. A sulfur-poor terrestrial core inferred from metal–silicate partitioning experiments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 469, 84–97 (2017).

Hirschmann, M. M., Bergin, E. A., Blake, G. A., Ciesla, F. J. & Li, J. Early volatile depletion on planetesimals inferred from C–S systematics of iron meteorite parent bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2026779118 (2021).

Newcombe, M. E. et al. Degassing of early-formed planetesimals restricted water delivery to Earth. Nature 615, 854–857 (2023).

Budde, G., Burkhardt, C. & Kleine, T. Molybdenum isotopic evidence for the late accretion of outer Solar System material to Earth. Nat. Astron. 3, 736–741 (2019).

Fischer-Gödde, M. et al. Ruthenium isotope vestige of Earth’s pre-late-veneer mantle preserved in Archaean rocks. Nature 579, 240–244 (2020).

Burkhardt, C. et al. Terrestrial planet formation from lost inner Solar System material. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj7601 (2021).

Dauphas, N., Hopp, T. & Nesvorný, D. Bayesian inference on the isotopic building blocks of Mars and Earth. Icarus 408, 115805 (2024).

Deguen, R., Olson, P. & Cardin, P. Experiments on turbulent metal–silicate mixing in a magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 310, 303–313 (2011).

Lodders, K. Relative atomic solar system abundances, mass fractions, and atomic masses of the elements and their isotopes, composition of the solar photosphere, and compositions of the major chondritic meteorite groups. Space Sci. Rev. 217, 44 (2021).

Wasson, J. T. & Kallemeyn, G. W. Compositions of chondrites. Philos. T. R. Soc. A 325, 535–544 (1988).

Moore, C. B. & Lewis, C. F. The distribution of total carbon content in enstatite chondrites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1, 376–378 (1966).

Alexander, C. M. O. Quantitative models for the elemental and isotopic fractionations in the chondrites: the non-carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 254, 246–276 (2019).

Alexander, C. M. O. Quantitative models for the elemental and isotopic fractionations in chondrites: the carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 254, 277–309 (2019).

Sakuraba, H., Kurokawa, H., Genda, H. & Ohta, K. Numerous chondritic impactors and oxidized magma ocean set Earth’s volatile depletion. Sci. Rep. 11, 20894 (2021).

Gu, J. T. et al. Composition of Earth’s initial atmosphere and fate of accreted volatiles set by core formation and magma ocean redox evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 629, 118618 (2024).

Mashino, I., Miozzi, F., Hirose, K., Morard, G. & Sinmyo, R. Melting experiments on the Fe–C binary system up to 255 GPa: constraints on the carbon content in the Earth’s core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 515, 135–144 (2019).

Hirao, N. et al. New developments in high-pressure X-ray diffraction beamline for diamond anvil cell at SPring-8. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 5, 018403 (2020).

Helffrich, G. Outer core compositional layering and constraints on core liquid transport properties. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 391, 256–262 (2014).

de Koker, N. P., Stixrude, L. & Karki, B. B. Thermodynamics, structure, dynamics, and freezing of Mg2SiO4 liquid at high pressure. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 72, 1427–1441 (2008).

Thibault, Y. & Walter, M. J. The influence of pressure and temperature on the metal-silicate partition coefficients of nickel and cobalt in a model C1 chondrite and implications for metal segregation in a deep magma ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 59, 991–1002 (1995).

Akahama, Y. & Kawamura, H. High-pressure Raman spectroscopy of diamond anvils to 250 GPa: method for pressure determination in the multimegabar pressure range. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 3748–3751 (2004).

Andrault, D. et al. Solidus and liquidus profiles of chondritic mantle: implication for melting of the Earth across its history. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 304, 251–259 (2011).

Mori, Y. et al. Melting experiments on Fe–Fe3S system to 254 GPa. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 464, 135–141 (2017).

Fukai, Y. & Suzuki, T. Iron-water reaction under high pressure and its implication in the evolution of the Earth. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 9222–9230 (1986).

Dorogokupets, P. I., Dymshits, A. M., Litasov, K. D. & Sokolova, T. S. Thermodynamics and equations of state of iron to 350 GPa and 6000. K. Sci. Rep. 7, 41863 (2017).

Nakajima, Y. et al. Thermoelastic property and high-pressure stability of Fe7C3: implication for iron-carbide in the Earth’s core. Am. Mineral. 96, 1158–1165 (2011).

McGuire, C. et al. P-V-T measurements of Fe3C to 117 GPa and 2100 K: implications for stability of Fe3C phase at core conditions. Am. Mineral. 106, 1349–1359 (2021).

Tagawa, S., Gomi, H., Hirose, K. & Ohishi, Y. High-temperature equation of state of FeH: implications for hydrogen in Earth’s inner core. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096260 (2022).

Fischer, R. A. et al. Equations of state in the Fe-FeSi system at high pressures and temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 2810–2827 (2014).

Tsutsumi, Y. et al. Retention of water in subducted slabs under core–mantle boundary conditions. Nat. Geosci. 17, 697–704 (2024).

Yurimoto, H., Nagashima, K. & Kunihiro, T. High precision isotope micro-imaging of materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 203–204, 793–797 (2003).

Sakamoto, N. et al. Remnants of the early solar system water enriched in heavy oxygen isotopes. Science 317, 231–233 (2007).

Greenwood, J. P. et al. Hydrogen isotope ratios in lunar rocks indicate delivery of cometary water to the Moon. Nat. Geosci. 4, 79–82 (2011).

Shimizu, K. et al. H2O, CO2, F, S, Cl, and P2O5 analyses of silicate glasses using SIMS: report of volatile standard glasses. Geochem. J. 51, 299–313 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396 (1997).

Yokoyama, T. et al. Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850 (2023).

Lauretta, D. et al. Asteroid (101955) Bennu in the laboratory: properties of the sample collected by OSIRIS-REx. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 59, 2453–2486 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge K. Yonemitsu for assisting with EPMA analyses. We thank S. Kawaguchi and H. Kadobayashi for their help in experiments at BL10XU, SPring-8 (proposal no. 2021B0181). We also thank S. Tagawa for his advice on melting experiments. This work was supported by the JSPS Kakenhi 21H04968 to K.H., 23KJ0479 to Y.T. and 21H04985 to H.Y. and by the “Imaging Platform” programme by MEXT. H.H. acknowledges support from the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under Grants No. NSTC 113-2116-M-008-010 and 114-2116-M-008-014-MY2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. and K.H. designed and led the project. This study is based on DAC experiments by Y.T. and S.Y., SIMS analyses by N.S., H.Y. and Y.T., first-principles calculations by H.H. and computational modelling by Y.T., S.M. and S.Y. Y.T. and K.H. wrote the manuscript, and all authors commented on it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsutsumi, Y., Sakamoto, N., Hirose, K. et al. Origin of Earth’s hydrogen and carbon constrained by their core-mantle partitioning and bulk Earth abundance. Nat Commun 16, 10038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65729-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65729-5