Abstract

Prior and concurrent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection are among the most important susceptibility factors for nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in Asia. Here we model this process in zebrafish with a primary Mycobacterium marinum infection followed by a secondary M. abscessus infection. We demonstrate preferential growth of secondary M. abscessus infection inside primary M. marinum granulomas. Granuloma-resident secondary M. abscessus is protected from macrophage-mediated immune control and antibiotic therapy. We find other opportunistic pathogens Mycobacterium smegmatis, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Candida auris are also able to colonize and preferentially grow inside primary M. marinum granulomas. Rapid growth of M. abscessus is driven by feeding on caseum produced by the primary M. marinum ESX-1 virulence program in a nutritionally separate niche from M. marinum. In this work we show tuberculous granulomas may provide a long-lasting niche for the growth of the opportunistic pathogen M. abscessus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infections by Mycobacterium abscessus are an emerging global health problem, and the rising rates of infection by similar non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) threaten to undermine the progress made in tuberculosis (TB) control in many countries1. Post-TB lung disease is an important but understudied chronic respiratory disease that contributes to mortality and morbidity, including raising the risk of subsequent NTM and TB infections in successfully treated TB patients2,3. In countries with endemic TB, NTM-TB coinfection accounts for up to 10% of the NTM patient population (Shandong Province, China) and 3% of the TB patient population (Taiwan)4,5. This association contrasts with the known protective effect of homologous M. tuberculosis infection against M. tuberculosis superinfection and the heterologous protection conferred by the M. bovis BCG vaccine against subsequent mycobacterial infections6.

The granuloma is the histological hallmark of TB infection and serves as the primary immunological interface between pathogenic mycobacteria and the host immune system. These long-lasting structures persist despite immune and antibiotic containment of M. tuberculosis, with varying estimates of their role in maintaining a reservoir for subclinical TB. In the case of calcified granulomas, they can remain lifelong7,8. Evidence that granulomas can harbor superinfecting tuberculous mycobacteria spans both experimental and clinical datasets, including key milestone studies demonstrating homing of superinfecting M. marinum into zebrafish and frog granulomas, M. tuberculosis and M. bovis into granulomas in mice and humans, respectively, and a high rate of cutaneous granulomas containing multiple mycobacterial species9,10,11,12,13. Intriguingly, NTM have been detected in IS6110 positive TB granuloma biopsy tissues, demonstrating infiltration of NTM into M. tuberculosis granulomas14. However, the role of tuberculous granulomas in driving susceptibility to NTM infection has yet to be examined. We hypothesized organized caseated granulomas may act as a protective niche for superinfecting mycobacteria, shielding them from cross-protective immune control and providing a readily available source of nutrients for rapid NTM growth.

The zebrafish-M. marinum infection model recapitulates important aspects of human-M. tuberculosis granuloma biology including caseous necrosis and hypoxia15,16. Infection of adult zebrafish with low doses of M. marinum can be used as a model of subclinical TB with long lasting control of bacterial burden mediated by the adaptive immune system17. Infection of transparent zebrafish embryos with fluorescent M. marinum is an invaluable tool to study the dynamics of mycobacterial interactions with host cells in vivo including macrophages18, neutrophils19, and stromal cells such as the vasculature by live imaging16. Live imaging studies of zebrafish have provided important in vivo evidence of the role of the mycobacterial ESX-1 Type VII Secretion System in directing macrophage behavior to the benefit of the spread of infection from primary granulomas20. While natural infection of zebrafish with M. abscessus has not been reported, the closely related NTM species Mycobacterium chelonae is a common pathogen of zebrafish colonies and the zebrafish has been adapted to the study of NTM species such as M. abscessus21,22. Infection of zebrafish with M. abscessus has been used to decipher the role of protective and detrimental innate immune responses in zebrafish embryos23, to provide a model of persistent granulomatous infection in adult zebrafish24, and to study the role of M. abscessus virulence associated with the hyperinflammatory rough morphotype25.

Here, we demonstrate that colonization with the natural mycobacterial pathogen M. marinum increases the susceptibility of zebrafish to M. abscessus. This susceptibility can be directly attributed to macrophage-mediated, ESX1-dependent carriage of M. abscessus into pre-existing caseous granulomas, where it is shielded from containment by the host immune system. We find that M. abscessus adapts to growth in the necrotic granuloma, enabling occupancy of a distinct nutritional niche.

Results

Primary M. marinum infection facilitates susceptibility of adult zebrafish to secondary M. abscessus infection

Previous studies using the frog-M. marinum and macaque-M. tuberculosis models have demonstrated protection against homologous superinfection9,26,27. The adult zebrafish platform provides a unique intersection of tuberculous granuloma formation when challenged with M. marinum and an immunologically-intact granuloma-forming permissive host for M. abscessus15,24. We performed a sequential infection experiment in adult zebrafish to determine if primary M. marinum tuberculous infection promotes resistance or susceptibility to secondary M. abscessus infection at 2 weeks post primary infection. A high-dose secondary infection with of 106 CFU of M. abscessus caused unexpected mortality in animals with a primary M. marinum infection (Fig. 1A). Animals infected with a primary M. marinum infection and a lower-dose secondary infection with 5×105 CFU of M. abscessus exhibited a higher M. abscessus burden than naive animals (Fig. 1B).

A Survival curve of adult zebrafish infected with combinations of primary M. marinum (Mm) and secondary M. abscessus (Mabs) at 2 weeks post primary infection. Data is from a single experiment with 45 animals. Statistical analysis reported is a Log-rank test comparing the PBS/Mabs group with the Mm/Mabs group. B Quantification of secondary M. abscessus burden at 2 weeks post secondary infection in naive and primary M. marinum-infected adult zebrafish infected at 2 weeks post primary infection, n = 10 and 8 respectively, two-sided T test. C Quantification of secondary M. marinum engraftment at 2 weeks post secondary infection in naive and primary M. marinum-infected adult zebrafish infected at 2 weeks post primary infection. Data is pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis reported is a two-sided Fisher’s Exact Test. D Quantification of secondary M. marinum burden at 2 weeks post secondary infection in naive and primary M. marinum-infected adult zebrafish infected at 2 weeks post primary infection, n = 12 and 10 respectively, two-sided T test. E Representative image of multilobed granuloma in 2 week post secondary infection adult zebrafish infected with secondary M. abscessus at 2 weeks post primary M. marinum infection. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. Image is representative of granulomas from survey of three animals. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD.

Mammalian models of M. tuberculosis sequential infections have demonstrated significant protection from infection9,26,27,28. We performed similar homotypic experiments with sequential M. marinum infection with Wasabi and TdTomato fluorescently-labelled strains to determine if our M. abscessus phenotype was an artifact of an exhausted immune system at 2 weeks post primary infection. We found that primary M. marinum infection protected against a homotypic secondary M. marinum infection both by preventing the engraftment of a low-dose M. marinum infection (Fig. 1C) and reducing the recovered M. marinum burden from a higher dose infection (Fig. 1D).

Cryosectioning of sequentially infected fish was performed to determine the spatial localization of superinfecting M. abscessus relative to primary M. marinum granulomas. Consistent with the homologous superinfection literature9, M. marinum granulomas were found to be colonized by secondary M. abscessus (Fig. 1E).

Colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas accelerates the growth of superinfecting M. abscessus

While the adult zebrafish experimental system facilitates the study of classic hypoxic caseous necrotic granulomas16,29,30, it does not readily facilitate real-time imaging of host-microbe interactions, as can be achieved with zebrafish embryos. Furthermore, sequential intraperitoneal injections likely bath the primary granuloma in secondary M. abscessus facilitating ready uptake. For these reasons we switched to the use of the zebrafish embryo-M. marinum/M. abscessus infection system to study the mechanisms of primary M. marinum infection-mediated susceptibility to secondary M. abscessus infection. We established an experimental sequential infection system in zebrafish embryos by performing the primary injection into the neural tube at the previously characterized “trunk” injection site16, then performing secondary injection into the circulation at 3 days post primary infection (dppi) (Fig. 2A). Timelapse imaging revealed uptake of M. abscessus from the circulation into established M. marinum granulomas (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Movie 1).

A Schematic illustrating embryo superinfection experimental set up. Abbreviation: Days post secondary infection (dpsi). B Still images extracted 900 minutes apart from Supplementary Movie 1. Site of M. abscessus (purple) injection is into Tg(kdrl:egfp)-positive vasculature (green) below primary M. marinum granuloma (yellow). Scale bars indicate 100 μm. C Quantification of secondary M. abscessus burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum. Naive n = 32, primary M. marinum n = 40, two-sided T test. D Quantification of secondary M. abscessus burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum grouped by quartile of M. abscessus found within M. marinum granulomas. Q1 and Q4 n = 10, Q2 and Q3 n = 11, one-way ANOVA. E Correlation of the percentage of secondary M. abscessus found within M. marinum granulomas (Percentage colonization) with total body secondary M. abscessus burden (M. abscessus fluorescent pixel count) in 3 dpsi embryos, n = 42, R squared value calculated by linear regression. F Quantification of secondary M. abscessus burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum, M. abscessus was delivered by co-injection with clodronate microsomes. PBS n = 21, clodronate n = 25, one-way ANOVA. G Quantification of fold change in M. abscessus burden during treatment with 10 μM clarithromycin from 2 dpsi to 4 dpsi. Naive (DMSO) n = 14, Naive (Clarithromycin) n = 18, Primary M. marinum (DMSO) n = 21, Primary M. marinum (Clarithromycin) n = 19, one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD.

Consistent with our adult zebrafish data, fluorescent pixel count revealed an increased M. abscessus burden in embryos 3 days post secondary infection (dpsi), when sequentially infected at 3 dppi with M. marinum, compared to M. abscessus infection of naive embryos (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, analysis of M. abscessus burden in sequentially infected embryos grouped by quartile of colonization revealed a higher overall M. abscessus burden in embryos with a high rate of colonization (Fig. 2D). Correlation of colocalization percentage with total M. abscessus burden revealed a positive relationship (Fig. 2E). Together, these data suggested colonization of primary granulomas accelerated secondary M. abscessus growth.

To examine the contribution of prior M. marinum granuloma formation relative to M. marinum infection-mediated immune subversion, we compared M. abscessus growth following mono- and co-injection with M. marinum. Unlike our sequential injection infection data, co-injection of M. marinum did not affect the growth of M. abscessus in zebrafish embryos, demonstrating the importance of granuloma formation in driving susceptibility to sequential M. abscessus infection (Supplementary Fig.1A). Interestingly, we found a contrasting antagonistic effect of M. abscessus infection on M. marinum growth, suggesting non-specific immune activation by M. abscessus may control concurrent M. marinum infection (Supplementary Fig.1B).

To determine if immune pressure restricts M. abscessus growth, resulting in preferential growth within primary M. marinum granulomas, we co-injected clodronate with secondary M. abscessus to deplete macrophages in zebrafish embryos immune suppression to alleviate immune pressure. Total M. abscessus burden increased with clodronate co-injection, driven entirely by an increase in the extra-granuloma compartment. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that granulomas provide M. abscessus with a physical sanctuary from the host immune control (Fig. 2F).

Caseum increases mycobacterial antibiotic tolerance by excluding antibiotics and rewiring bacterial physiology31,32. Specifically, stationary phase M. abscessus in caseum is markedly more resistant to frontline antibiotics such as bedaquiline, clarithromycin, imipenem, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin compared to actively growing broth cultures32. Clarithromycin, an example of a current front line antibiotic, was effective at restraining the growth of M. abscessus in naive but not M. marinum infected zebrafish embryos when treatment as initiated after granuloma colonization (Fig. 2G and Supplementary Fig. 1C).

Opportunistic pathogens passively colonize primary M. marinum granulomas in zebrafish embryos

We examined the role of secondary mycobacterial infection in directing the colonization of primary granulomas by comparing the M. abscessus parental “low virulence” smooth colony morphotype to the more virulent rough colony morphotype used in our previous experiments. There was no difference in colonization by either colony morphotype compared to each other or relative to the lower rate of colonization seen in M. marinum superinfection in zebrafish embryos (Supplementary Fig.2A). Interestingly, the rate of granuloma colonization was similar between WT and ΔESX1 M. marinum secondary infections in zebrafish embryos, suggesting the differentiating factor between M. marinum and M. abscessus granuloma colonization potential is species- rather than virulence factor-specific. Furthermore, we did not observe a growth advantage for secondary M. marinum infection compared to infection into naive embryos (Fig. 3A).

A Quantification of secondary M. marinum burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum. Naive n = 15, Primary M. marinum n = 15, two-sided T test. B Quantification of secondary M. smegmatis burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum. Naive n = 28, Primary M. marinum n = 22, two-sided T test. C Quantification of secondary M. smegmatis burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum grouped by quartile of M. smegmatis found within M. marinum granulomas. Q1 and Q4 n = 16, Q2 and Q3 n = 17, one-way ANOVA. D Images extracted from Supplementary Movie 2 tracking ingress of PFA-fixed M. abscessus into a primary M. marinum granuloma from 260-376 minutes post tracking and residency of PFA-fixed M. abscessus inside granuloma. Arrows indicate location of PFA-fixed M. abscessus fluorescent signal of interest, scale bar represents 100 μm. E Quantification of secondary A. fumigatus burden in 3 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum. Naive n = 32, Primary M. marinum n = 9, two-sided T test. F Quantification of secondary C. auris burden in 2 dpsi embryos infected with primary M. marinum. Naive n = 35, Primary M. marinum n = 25, two-sided T test. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD.

We next performed super infection with fluorescent Mycobacterium smegmatis, typically considered avirulent. Similar to M. abscessus, superinfecting M. smegmatis had a significant growth advantage compared to infection into age-matched naive embryos (Fig. 3B), and total M. smegmatis burden was higher in the embryos in the highest quartile of granuloma colonization compared to the other three quartiles (Fig. 3C). In co-injection studies, we observed a similar lack of protective effect of M. marinum on M. smegmatis burden in the absence of pre-existing granulomas and an antagonistic effect of M. smegmatis on M. marinum burden (Supplementary Fig.1B and 2B).

We also injected embryos with paraformaldehyde-killed M. abscessus and observed trafficking to granulomas, suggesting the delivery of NTM to primary tuberculous granulomas is a passive feature of NTM species (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Movie 2).

This led us to test the bounds of the colonization phenotype by non-mycobacterial secondary infections. First, we used uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) as the secondary infection. This typically acute infection is capable of persisting in zebrafish embryos but we did not observe cross-genus interaction, consistent with data from a natural pathogen Salmonella experiment suggesting a different niche from NTMs9 (Supplementary Fig. 2C).

Next, as fungal infections are a common consequence of post-TB lung disease and opportunistic yeast have the ability to survive within macrophages33,34, we tested the ability of the common post-TB lung disease fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus to colonize granulomas. We observed A. fumigatus colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas and a growth advantage for A. fumigatus in animals with an existing M. marinum infection (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Fig. 2D).

We also examined the ability of the emerging pathogen Candida auris to colonize granulomas. We observed a similar pattern of C. auris colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas and C. auris growth advantage in animals with an existing M. marinum infection as the other opportunistic pathogens (Fig. 3F, Supplementary Fig. 2E).

Together, these data suggest that granuloma colonization depends on the ability of secondary infections to be recognized and engulfed by macrophages, survive intracellular killing mechanisms, but avoid overstimulating the macrophage to stop and form aggregates.

ESX-1 directed maturation of primary M. marinum granulomas permits growth of superinfecting M. abscessus

The reproduction of the caseating granulomas seen in TB is a key advantage of the zebrafish-M. marinum infection model, and granulomas formed following trunk injection of M. marinum into embryos undergo stereotypical progression from cellular to necrotic granuloma from 3-5 dppi15,16. Reducing the primary inoculum to approximately 100 CFU and comparing the start of secondary infection from 3 to 4 dppi revealed a granuloma maturation-dependent increase in primary granuloma colonization by superinfecting M. abscessus (Fig. 4A).

A Quantification of M. abscessus colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas at 3 dpsi when infected at 3 or 4 dppi, 3 dppi n = 50, 4 dppi n = 42, two-sided T test. B Representative images of M. abscessus colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas at 3 dpsi treated with isoniazid immediately after secondary infection. C Quantification of primary M. marinum burden in 3 dpsi animals infected with M. abscessus and treated with isoniazid immediately after secondary infection, Control n = 17, Isoniazid n = 24, two-sided T test. D Quantification of M. abscessus colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas at 3 dpsi treated with isoniazid immediately after infection, Control n = 17, Isoniazid n = 24, two-sided T test. E Quantification of animals with at least one M. abscessus colonization event of primary WT and ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas at 1 dpsi. Data is pooled from two independent experiments. WT n = 27 positive, 3 negative, ΔESX1 n = 24 positive, 13 negative, two-sided Fisher’s Exact Test. F Quantification of macrophage recruitment to WT vs ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas across 4-22 hpsi. WT n = 10, ΔESX1 n = 12, two-sided T test. G Quantification of M. abscessus colonization of primary WT and ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas at 3 dpsi. WT n = 17, ΔESX1 n = 22, two-sided T test. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD.

Conversely, arresting the maturation of primary granulomas with M. marinum-bacteriostatic isoniazid treatment immediately after the secondary infection reduced the rate of primary granuloma colonization by superinfecting M. abscessus in zebrafish embryos (Fig. 4B, C, D).

The ESX1 type VII secretion system is the most important pro-granulomatous virulence factor in M. marinum and M. tuberculosis responsible for directly subverting phagocyte function, and driving necrosis and the recruitment of permissive macrophages to feed the granuloma35. We found impaired colonization of primary ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas compared to primary WT M. marinum granulomas early in embryo infection even when similar burdens are reached with a higher initial inoculum (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, we observed similar rate of macrophage recruitment to 5 dppi primary ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas which contrasts to the reduced rate of macrophage recruitment early in ΔESX1 M. marinum infection compared to WT M. marinum infection20, following secondary M. abscessus infection suggesting reduced macrophage migration is not the only factor accounting for reduced colonization of primary ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas by secondary M. abscessus (Fig. 4F).

The small difference in initial colonization rate at 1 dpsi was compounded during later stages of M. abscessus superinfection with primary ΔESX1 M. marinum granulomas carrying only a very small minority of M. abscessus by 3 dpsi. This suggested roles for M. marinum ESX1 in creating primary granulomas that attract and then further support the growth of superinfecting M. abscessus (Fig. 4G).

We next investigated the mode of M. abscessus ingress into primary zebrafish embryo-M. marinum granulomas by live imaging. As our sequential infection system introduced M. abscessus into the circulation, we first tracked the vascular source of M. abscessus ingression into M. marinum granulomas in the Tg(kdrl:egfp)s843 line, where vascular endothelial cells are labelled by EGFP expression36. We observed extravasation of M. abscessus from blood vessels adjacent and distal to the granuloma followed by directional migration and ingress (Supplementary Movie 1). Ingress events originating from adjacent intersegmental and dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels were classed as local vasculature and all other vessels were classed as distal vasculature (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Quantification of 114 extravasation events leading to M. abscessus ingress in 11animals revealed a mix of 60 local and 54 distal extravasation events, demonstrating the possibility of both hematogenous spread and macrophage carriage.

We have previously used vascular normalization as a host-directed therapy to reduce the extravasation of neutrophils around M. marinum granulomas. Here, we hypothesized that preventing vascular pathology would reduce the extravasation of M. abscessus towards granulomas in our superinfection model37. We treated M. marinum-infected embryos with pazopanib, an FDA-approved VEGFR inhibitor with host-directed activity against M. marinum infection-induced vascular pathologies16, starting one day prior to secondary M. abscessus infection and continuing until 3 dpsi. Treatment with pazopanib reduced the rate of primary granuloma colonization by superinfecting M. abscessus when assayed 3 dpsi (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

Previous live imaging and histological studies have implicated ingress of infected macrophages as the primary mode of M. abscessus and M. marinum dissemination in zebrafish embryos. Our extravasation imaging demonstrated the direct migration of M. abscessus into granulomas, suggesting macrophage carriage. To confirm this hypothesis, we performed live imaging of granuloma ingress in the Tg(acod1:tdtomato)xt40 line, where macrophages are labelled with TdTomato (Supplementary Movie 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4), and carriage of M. abscessus by GFP positive and negative cells with similar DIC morphologies in the alternative TgBAC(mpeg1.1:egfp)vcc7 where a subset of macrophages are labelled with EGFP (Supplementary Movie 4)38,39. Quantification of 112 M. abscessus ingress events in 12 animals revealed 78 events of mpeg1.1:egfp positive macrophage carriage of M. abscessus.

Neutrophils are abundant immune cells that play a crucial role in controlling M. abscessus in zebrafish embryos23. To determine the potential contribution of neutrophil carriage, we performed live imaging of granuloma ingress in the Tg(lyzc:egfp)nz117 line, where neutrophils are labelled with EGFP40. As expected, we observed neutrophil recruitment to primary granulomas and interactions with M. abscessus. However, GFP-positive neutrophil carriage of M. abscessus was rare (Supplementary Movie 5). Quantification of 75 M. abscessus ingress events in 15 animals revealed only 6 events of neutrophil carriage of M. abscessus, demonstrating a low utilization of neutrophils for carriage of M. abscessus.

M. abscessus adaptation to primary granuloma residency

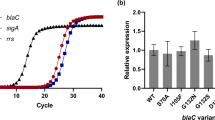

To understand how M. abscessus takes advantage of the necrotic granuloma niche we first examined the transcriptome of M. abscessus grown in complete 7H9 media with M. abscessus in the zebrafish embryo infection model (Supplementary Data 1). Analysis of a PCA plot found a close grouping of the in vitro samples, as expected from the tightly controlled nature of broth culture, and wider variation across the in vivo samples indicative of the heterogeneity of zebrafish infection models (Supplementary Fig. 5). Examination of known stress response and virulence gene families: Esx-3, mycobactins, oxidative stress and cell wall remodeling41,42,43,44, confirmed the zebrafish embryo infection model induces the expression of a virulence-associated M. abscessus gene program (Fig. 5A). Further comparison of the M. abscessus lipid metabolism gene expression program45, revealed an upregulation of lipid metabolism during adaptation to infection suggesting M. abscessus may utilize the lipid-rich caseum to fuel accelerated growth during superinfection (Fig. 5B).

A Heat map of M. abscessus stress gene expression derived from RNAseq of M. abscessus at 6 dpi in zebrafish embryos compared to baseline in vitro 7H9 broth cultured M. abscessus. Values are log2 fold change, all genes are differentially expressed between in vivo and in vitro groups (see Supplementary File 1). B Heat map of in vivo M. abscessus lipid metabolism gene expression compared to in vitro 7H9 broth cultured M. abscessus. Values are log2 fold change, all genes are differentially expressed between in vivo and in vitro groups (see Supplementary File 1). C Quantification of M. abscessus growth in 7H9 media supplemented with carbon sources. Single experiment with technical triplicates. D Quantification of M. abscessus and M. marinum growth in 7H9 media diluted to 10% with PBS and supplemented with in vitro caseum. M. marinum culture was performed for 4 days prior to Day 00 when M. abscessus is added to the co-culture conditions. Data is representative of three independent experiments. E Representative images of M. abscessus and M. marinum growth in 7H9 media diluted to 10% with PBS and supplemented with in vitro caseum. M. marinum culture was performed for 4 days prior to Day 00 when M. abscessus is added to the co-culture conditions. F Quantification of M. marinum growth in 163 individual embryos from 0 to 3 dpsi with M. abscessus. R squared value calculated by linear regression, slope equation Y = −0.07066*X + 32.79, P = 0.0481.

To test the hypothesis that M. abscessus could adapt to the caseum in the necrotic core as a nutrient source, we next switched to an in vitro system. We analyzed the growth of M. abscessus in diluted 7H9 media supplemented with OADC as a positive control, RAW 264.7 cell-derived in vitro caseum46, and the individual lipid substrates cholesterol and stearic acid. Growth curves demonstrated that M. abscessus is able to grow rapidly with a range of lipid substrates, specifically being able to utilize in vitro caseum as a substrate (Fig. 5C).

To model our in vivo sequential infections, we first cultured M. marinum in in vitro caseum, facilitating pre-conditioning of the caseum. After 4 days when M. marinum growth had plateaued, we introduced M. abscessus to the culture system. The addition of M. abscessus to the established M. marinum culture resulted in lower overall growth of M. abscessus compared to its monoculture in sterile caseum consistent with the depletion of some nutrients by M. marinum pre-conditioning (Fig. 5D). This growth defect was ameliorated when new caseum was added to the established M. marinum culture system, suggesting that the optimal M. abscessus growth conditions overlap with nutrients utilized by M. marinum (Fig. 5D). We observed similar stability of M. marinum CFU levels across all experiments, regardless of whether M. abscessus was added to the culture, suggesting a neutral effect of M. abscessus on established M. marinum in caseum. Imaging of the in vitro growth assay revealed physically distinct growth of M. abscessus around M. marinum (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Fig. 6).

To study this interaction in vivo, we analyzed the growth of M. marinum in individual embryos with and without sequential M. abscessus infection. Analysis of embryos infected with only M. marinum revealed a wide range (11-101x) of M. marinum growth across days 3-6 post primary infection, equivalent to 0-3 dpsi in the sequential infection experiment, and all sequential infection values fell within this range (Fig. 5F). Further analysis of M. marinum fold change from 0-3 dpsi infection demonstrated no correlation between M. marinum growth and the rate of M. abscessus colonization of primary M. marinum granulomas (Fig. 5F). Together, these data demonstrate that M. abscessus occupies a separate nutritional niche in necrotic granulomas that is not at the expense of M. marinum.

Discussion

In Singapore, a country that has effectively eliminated local transmission but retains the epidemiological “scar” of historically high prevalence of TB, M. abscessus is one of the most prevalent NTM infections, with prior TB being the most common predisposing factor47. Evidence from mammalian models suggests that increasing TB severity drives a shift from leukocyte-mediated heterologous protection against secondary mycobacterial infection afforded by a contained primary infection toward systemic reprogramming of hematopoiesis, leading to increased susceptibility to secondary mycobacterial infection following disseminated disease48. These observations suggest that compromised leukocyte immunity could drive increased NTM susceptibility in treated TB patients

Our data provide compelling evidence that granulomas formed during TB infection provide a niche for the growth of M. abscessus in otherwise immunologically intact resistant hosts. This finding has significant implications for explaining the increased risk of NTM infection in patients with prior or ongoing pulmonary TB. Post TB lung disease encompasses a wide range of histological lung remodeling, leading to a loss of respiratory function. The loss of lung respiratory function is hypothesized to impair the physical clearance of NTM and opportunistic fugnal pathogens following inoculation from environmental reservoirs3. Although our models are unable to replicate the physical clearance of inhaled opportunistic pathogens, they faithfully produce TB-like granulomas with caseous necrosis. We posit that unresolved TB granulomas should be considered a susceptibility factor for infection by opportunistic pathogens in TB patients.

A strength of our model is the production of caseous necrosis by M. marinum similar to human TB cavities and necrotic granulomas. Our findings thus highlight the ability of M. abscessus to adapt to and thrive in the relatively nutrient-restricted environment of necrotic granulomas. We have observed hypoxia in similar zebrafish-M. marinum granulomas in previous work using a combination of host hypoxia-induced gene expression, pimonidazole staining, and metronidazole16. M. abscessus grows well in vitro under hypoxic conditions for 5-10 days then loses viability unlike M. tuberculosis which continues to persist for longer periods of hypoxic stress49. A limitation of our model is that we are unable to track infection in embryos for these extended periods and are unable to determine the exact initiation of granuloma colonization in the adult zebrafish model to study the effect of long term granuloma hypoxia on M. abscessus superinfection outcome.

Another limitation of our models was the inability to clear M. marinum infection to model the clinical situation where microbiological cure of primary M. tuberculosis infection is achieved prior to M. abscessus infection. We were also unable to determine if M. abscessus is able to use primary M. tuberculosis granulomas as a “beachhead” to establish infection and then subsequently expand out into other areas. Further clinical research is required to determine the temporal relationship between prior TB diagnosis and susceptibility to M. abscessus infection.

We were also unable to determine if the primary M. marinum infection-induced resistance of M. abscessus to clarithromycin was a result of granulomatous residence/co-infection induced erm41 transcriptional upregulation or a physical effect of granuloma necrosis on the antibiotic. Of note, our RNAseq data found a non-significant down regulation of erm41 (mab_2297) transcription during M. abscessus monoinfection compared to broth culture.

The rapid growth of M. abscessus and M. marinum in co-culture experiments are most likely due to the relative growth rates of the organisms rather than a true virulence advantage. Dual-species granulomas are usually bounded by M. marinum or exhibit a mixed fluorescent signal, suggesting M. abscessus does not expand these histopathological structures in our assays. Furthermore, naive embryos were largely able to control M. abscessus when infected at 5 dpf but had early granuloma formation when infected with M. marinum, consistent with M. marinum having a much higher relative growth potential per unit of inoculum across zebrafish infection assays16,24. Further experiments in appropriate model systems will be required to determine the effect of primary tuberculous infection clearance from granulomas on the survival of super infecting NTM who can no longer “hide” behind ESX1 immune subversion driven by the primary species.

Our findings highlight the importance of efforts to find preventative and interventional treatments for TB pathologies, including granuloma resolution, as the risks of post-infection sequalae will persist long after TB transmission is eradicated. Many NTM cases are initially diagnosed as TB, resulting in empirical anti-TB therapy to which M. abscessus is insensitive. These cases can be variably defined as recent, prior, or concomitant TB with M. abscessus infection, depending on the level of specificity in the initial diagnosis. In cases where there is evidence of M. tuberculosis at the first diagnosis, our findings suggest that these patients may be at risk of severe M. abscessus infection phenotypes, such as fibrocavitary disease compared to the bronchial nodular form.

While there is mixed evidence from preclinical infection models for and against a protective effect of primary M. tuberculosis infection on reinfection, epidemiological evidence clearly demonstrates that prior M. tuberculosis or NTM infection is a risk factor for future tuberculous and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection50,51. While some of this risk can be attributed to patients remaining in physical environments with high mycobacterial exposure levels, countries such as Singapore, where TB transmission was effectively eliminated within a generation, manifest a long, lingering tail of post-TB susceptibility to NTM infection at a population level52.

The severity of primary infection in preclinical models appears to be the decisive factor for determining if primary mycobacterial infection is protective against future challenge. Naturally controlled murine and non-human primate M. tuberculosis infections clearly protect against sequential M. tuberculosis infection27,28. Poor initial control of infection by highly virulent strains, systemic administration of live M. tuberculosis53, or the converse clearing of infection26,27 can compromise immunological control of the second infection by a range of mechanisms from the hematopoietic stem cell through to the pulmonary microenvironment. This suggests a balance of ongoing inflammatory and antigenic stimulation is the primary driver of protective anti-mycobacterial immune responses. It will be important to adapt these models to investigate the relative contributions of hematopoietic reprogramming and pulmonary adaptive immunity to the restriction of NTM in models that recapitulate human-like granulomas.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate necrotic tuberculous granulomas provide a niche for the rapid growth of superinfecting NTM and opportunistic fungal pathogens. This may have clinical implications for TB patients living in areas with high exposure to environmental NTMs and fungi, and demonstrates the importance of limiting TB tissue damage to mitigate post-infection sequalae.

Methods

Zebrafish

Zebrafish experiments were carried out under the A*STAR IACUC approvals 211667 and 221694. Adults were housed under 14 hour light / 10 hour dark cycles in 28 °C recirculating systems. Embryos were produced by natural spawning and raised in E3 media supplemented with PTU at 28 °C.

Zebrafish strains used were WT AB strain, Tg(kdrl:egfp)36, Tg(acod1:tdtomato)xt40 39, TgBAC(mpeg1.1:egfp)vcc754, and Tg(lyzc:egfp)nz117 40.

Growth of microbes

M. abscessus strain CIP104536T rough (R) and smooth (S) variants, M. marinum M strain, and M. smegmatis mc2 155 were cultured in 7H9 or on 7H10 supplemented with OADC and hygromycin (300 μg/ml for M. abscessus, 50 μg/ml for M. marinum, and 100 μg/ml for M. smegmatis) to select for pTEC fluorescent protein plasmids (L. Ramakrishnan, plasmids are available through Addgene https://www.addgene.org/Lalita_Ramakrishnan/, pTEC27 tdTomato, pTEC15 Wasabi). C. auris expressing mCherry was prepared as previously described and is available upon request from EWLC55. A. fumigatus A1160 strain was grown on solid glucose minimal media and harvested from plates as previously described56. Uropathogenic E. coli was prepared as previously described57.

PFA killing of M. abscessus was carried out by resuspending a midlog culture of M. abscessus in 4% PFA in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Fixed bacteria were rinsed prior to injection. Validation of killing was performed by plating on 7H10 supplemented with OADC and incubation at 37 °C for 7 days.

Growth curves of M. abscessus and M. marinum were performed in 10% 7H9 media diluted with PBS at 30 °C in a static incubator. In vitro caseum was produced as previously described31. Diluted 7H9 was supplemented with final concentrations of 50% (v/v) caseum preparation, 250 μM cholesterol, and 250 μM stearic acid.

Adult zebrafish infections

Adult zebrafish were injected with approximately 100 CFU M. marinum or 5×105 to 106 CFU of M. abscessus as indicated. Secondary infection was carried out at 2 weeks post primary infection. Animals were housed under 14 hour light / 10 hour dark cycles in an isolated 28° C recirculating system and fed once daily with a nutritionally complete dry feed.

Bacterial enumeration by CFU recovery was performed by bead beating individual adult zebrafish in a Tomy Micro Smash MS-100 with MP Biomedical Lysing Matrix S 3.175 mm diameter stainless steel beads at 3500 RPM for two bursts of 1 minute at 4 degrees. Homogenate was plated on 7H10 agar supplemented with 100 μg/ml hygromycin B and 10 μg/ml amphotericin B for M. marinum or LB Agar supplemented with 300 μg/ml hygromycin B and 10 μg/ml amphotericin B for M. abscessus. Growth of M. marinum was carried out at 30 °C for 7 days and growth of M. abscessus was carried out at 37 °C for 5 days.

Histology was carried out using a Leica CM1520 to cut 10 μm thick cryosections of PFA-fixed adults and counterstaining with DAPI. Fluorescent images of preserved bacterial fluorescence were acquired using a Nikon Ni-E upright microscope.

Zebrafish embryo infections

Zebrafish embryos were infected by microinjection with approximately 200 CFU M. marinum, 1000 CFU ΔESX1 M. marinum or M. abscessus, or 50 CFU A. fumigatus or C. auris. Primary infection was performed by injection into the neural tube above the yolk sac extension at 2 dpf and secondary infection was performed by intravascular injection into the dorsal aorta or caudal vein at 5 dpf/3 dpi, unless otherwise described.

Clodronate microsomes were co-injected with secondary M. abscessus infection by intravascular injection into the dorsal aorta or caudal vein at 5 dpf/3 dpi.

Clarithromycin (10 μg/ml final concentration), isoniazid (50 μM final concentration), pazopanib (500 nM final concentration) were added directly to embryo media.

Microscopy of zebrafish embryos

All microscopy was carried out stereomicroscopy of immobilized zebrafish embryos. Static imaging was performed on a Nikon SMZ25 stereoscope or an inverted Nikon Eclipse Ti2. Time lapse imaging was performed on inverted Thermofisher EVOS7000 or Olympus IX-83 microscopes.

Image analysis was performed in ImageJ/FIJI with bacterial fluorescent pixel count (FPC) carried out as previously described58. Areas of overlap were determined by manually drawing the outline of M. marinum granulomas, these outlines were set as Regions of Interest in FIJI and used to measure the FPC of M. abscessus. The percentage of M. abscessus in granulomas was calculated by the formula (M. abscessus FPC overlap with M. marinum / total M. abscessus FPC) x 100.

To visualize A. fumigatus, we incubated infected embryos in 250 μg/ml final concentration calcofluor white for 5 minutes59. Embryos were then rinsed at least three times prior to imaging.

RNA sequencing of M. abscessus

Mycobacterial RNA was harvested from 3 mid-log 7H9 cultures and 3 pools of trizol-pre lysed 7 dpi M. abscessus-infected zebrafish embryos by bead beating in Lysis buffer and further processed according to manufactures protocol (MN-NucleoSpin RNA kit). Total RNA was processed by ribosomal RNA depletion/cDNA synthesis/adaptor ligation and subjected to 150 bp paired end sequencing on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 (NovogeneAIT Genomics Singapore). Data is deposited in NCBI as BioProject PRJNA1267787.

Raw reads (FASTQ files) were mapped to the M. abscessus reference genome (ASM6918v1, GenBank) using the STAR aligner (version 2.7.10b). The gene count matrix was generated using featureCounts of Rsubread package (version 2.8.2) in R (version 4.4.2), with genomic annotations obtained from the corresponding GTF file from GenBank. The gene counts were subsequently converted to log2RPKM values by edgeR package (version 4.4.2), and PCA analysis of log2PRKM values was then performed by FactoMineR package (version 2.11). Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 package (version 1.46.0) where the p-values attained by Wald test were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Genes with an adjusted p-value (FDR) of <0.05 and a log₂ fold change > 1.5 or < −1.5 were considered significantly differentially expressed. Volcano plot was generated by EnhancedVolcano package (version 1.24.0). A spreadsheet of results is available as Supplementary File 1. DEGs were manually annotated to stress response and lipid metabolism pathways for display. A spreadsheet of results is available as Supplementary File 1. DEGs were manually annotated to stress response and lipid metabolism pathways for display.

Statistics

All analyses of infection experiments were carried out on untransformed data with Graphpad Prism (version 10) using two-sided T-tests or Mann-Whitney tests for pairwise comparisons of parametric and nonparametric data or one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests for multiple comparisons. All data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments unless otherwise stated in the captions. Error bars on graphs represent standard deviation and central line is mean.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The RNAseq data generated in this study have been deposited in NCBI SRA as bioproject PRJNA1267787. SRA accession codes for individual samples are: SRR33696322, SRR33696321, SRR33696320, SRR33696319, SRR33696318, SRR33696317. The raw imaging datasets are in controlled access data storage at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, they can be retrieved upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Johansen, M. D., Herrmann, J. L. & Kremer, L. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria and the rise of Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 18, 392–407 (2020).

Fox, G. J. et al. Post-treatment Mortality Among Patients With Tuberculosis: A Prospective Cohort Study of 10 964 Patients in Vietnam. Clin. Infect. Dis. 68, 1359–1366 (2019).

Allwood, B. W. et al. Post-Tuberculosis Lung Disease: Clinical Review of an Under-Recognised Global Challenge. Respiration; Int. Rev. Thorac. Dis. 100, 751–763 (2021).

He, Y., Wang, J. L., Zhang, Y. A. & Wang, M. S. Prevalence of Culture-Confirmed Tuberculosis Among Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease. Infect. Drug Resist 15, 3097–3101 (2022).

Lin, C. K. et al. Incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease and coinfection with tuberculosis in a tuberculosis-endemic region: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Med. (Baltim.) 99, e23775 (2020).

Cadena, A. M. et al. Concurrent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis confers robust protection against secondary infection in macaques. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007305 (2018).

Silva Miranda, M., Breiman, A., Allain, S., Deknuydt, F. & Altare, F. The tuberculous granuloma: an unsuccessful host defence mechanism providing a safety shelter for the bacteria? Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 139127 (2012).

Behr, M. A., Edelstein, P. H. & Ramakrishnan, L. Is Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection life long? BMJ 367, l5770 (2019).

Cosma, C. L., Humbert, O. & Ramakrishnan, L. Superinfecting mycobacteria home to established tuberculous granulomas. Nat. Immunol. 5, 828–835 (2004).

Cosma, C. L., Humbert, O., Sherman, D. R. & Ramakrishnan, L. Trafficking of superinfecting Mycobacterium organisms into established granulomas occurs in mammals and is independent of the Erp and ESX-1 mycobacterial virulence loci. J. Infect. Dis. 198, 1851–1855 (2008).

Moreno-Molina, M. et al. Genomic analyses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from human lung resections reveal a high frequency of polyclonal infections. Nat. Commun. 12, 2716 (2021).

Lieberman, T. D. et al. Genomic diversity in autopsy samples reveals within-host dissemination of HIV-associated Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 22, 1470–1474 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Retrospective clinical and microbiologic analysis of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the microbiological diagnosis of cutaneous infectious granulomas. Ann. Clin. Microbiol Antimicrob. 23, 84 (2024).

Du, W. et al. Association of bacteriomes with drug susceptibility in lesions of pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Heliyon 10, e37583 (2024).

Swaim, L. E. et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection of adult zebrafish causes caseating granulomatous tuberculosis and is moderated by adaptive immunity. Infect. Immun. 74, 6108–6117 (2006).

Oehlers, S. H. et al. Interception of host angiogenic signalling limits mycobacterial growth. Nature 517, 612–615 (2015).

Parikka, M. et al. Mycobacterium marinum Causes a Latent Infection that Can Be Reactivated by Gamma Irradiation in Adult Zebrafish. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002944 (2012).

Davis, J. M. et al. Real-time visualization of mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity 17, 693–702 (2002).

Yang, C. T. et al. Neutrophils exert protection in the early tuberculous granuloma by oxidative killing of mycobacteria phagocytosed from infected macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 12, 301–312 (2012).

Davis, J. M. & Ramakrishnan, L. The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculous infection. Cell 136, 37–49 (2009).

Whipps, C. M. et al. Detection of autofluorescent Mycobacterium chelonae in living zebrafish. Zebrafish 11, 76–82 (2014).

Johansen, M. D., Spaink, H. P., Oehlers, S. H. & Kremer, L. Modeling nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in zebrafish. Trends Microbiol. 32, 663–677 (2024).

Bernut, A. et al. Mycobacterium abscessus-Induced Granuloma Formation Is Strictly Dependent on TNF Signaling and Neutrophil Trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005986 (2016).

Kam, J. et al. Rough and smooth variant Mycobacterium abscessus infections are differentially controlled by host immunity during chronic infection of adult zebrafish. Nat. Commun. 13, 952 (2022).

Bernut, A. et al. Mycobacterium abscessus cording prevents phagocytosis and promotes abscess formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E943–E952 (2014).

Ganchua, S. K. et al. Antibiotic treatment modestly reduces protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis reinfection in macaques. Infect Immun, e0053523, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00535-23 (2024).

Nemeth, J. et al. Contained Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection induces concomitant and heterologous protection. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008655 (2020).

Bromley, J. D. et al. CD4(+) T cells re-wire granuloma cellularity and regulatory networks to promote immunomodulation following Mtb reinfection. Immunity https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2024.08.002 (2024).

Cronan, M. R. et al. Macrophage Epithelial Reprogramming Underlies Mycobacterial Granuloma Formation and Promotes Infection. Immunity 45, 861–876 (2016).

Cronan, M. R. et al. A non-canonical type 2 immune response coordinates tuberculous granuloma formation and epithelialization. Cell 184, 1757–1774 e1714 (2021).

Sarathy, J. P. et al. A Novel Tool to Identify Bactericidal Compounds against Vulnerable Targets in Drug-Tolerant M. tuberculosis found in Caseum. mBio 14, e0059823 (2023).

Xie, M. et al. ADP-ribosylation-resistant rifabutin analogs show improved bactericidal activity against drug-tolerant M. abscessus in caseum surrogate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e0038123 (2023).

Tenor, J. L., Oehlers, S. H., Yang, J. L., Tobin, D. M. & Perfect, J. R. Live Imaging of Host-Parasite Interactions in a Zebrafish Infection Model Reveals Cryptococcal Determinants of Virulence and Central Nervous System Invasion. mBio 6 https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01425-15 (2015).

Madden, A. et al. A systematic review of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis among patients treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaf150 (2025).

Cosma, C. L., Klein, K., Kim, R., Beery, D. & Ramakrishnan, L. Mycobacterium marinum Erp is a virulence determinant required for cell wall integrity and intracellular survival. Infect. Immun. 74, 3125–3133 (2006).

Jin, S. W., Beis, D., Mitchell, T., Chen, J. N. & Stainier, D. Y. Cellular and molecular analyses of vascular tube and lumen formation in zebrafish. Development 132, 5199–5209 (2005).

Kam, J. Y. et al. Inhibition of infection-induced vascular permeability modulates host leukocyte recruitment to Mycobacterium marinum granulomas in zebrafish. Pathogens and disease 80 https://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftac009 (2022).

Sugimoto, K., Hui, S. P., Sheng, D. Z., Nakayama, M. & Kikuchi, K. Zebrafish FOXP3 is required for the maintenance of immune tolerance. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 73, 156–162 (2017).

Brewer, W. J. et al. Macrophage NFATC2 mediates angiogenic signaling during mycobacterial infection. Cell Rep. 41, 111817 (2022).

Hall, C., Flores, M. V., Storm, T., Crosier, K. & Crosier, P. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 42 (2007).

Foreman, M., Kolodkin-Gal, I. & Barkan, D. A Pivotal Role for Mycobactin/mbtE in Growth and Adaptation of Mycobacterium abscessus. Microbiol Spectr. 10, e0262322 (2022).

Mori, M. et al. Targeting Siderophore-Mediated Iron Uptake in M. abscessus: A New Strategy to Limit the Virulence of Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria. Pharmaceutics 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15020502 (2023).

Boeck, L. et al. Mycobacterium abscessus pathogenesis identified by phenogenomic analyses. Nat. Microbiol 7, 1431–1441 (2022).

Dubois, V. et al. Mycobacterium abscessus virulence traits unraveled by transcriptomic profiling in amoeba and macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1008069 (2019).

Crowe, A. M. et al. The unusual convergence of steroid catabolic pathways in Mycobacterium abscessus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207505119 (2022).

Sarathy, J. P. et al. An In Vitro Caseum Binding Assay that Predicts Drug Penetration in Tuberculosis Lesions. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/55559 (2017).

Lim, A. Y. H. et al. Profiling non-tuberculous mycobacteria in an Asian setting: characteristics and clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients in Singapore. BMC Pulm. Med. 18, 85 (2018).

Khan, N. et al. M. tuberculosis Reprograms Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Limit Myelopoiesis and Impair Trained Immunity. Cell 183, 752–770.e722 (2020).

Simcox, B. S., Tomlinson, B. R., Shaw, L. N. & Rohde, K. H. Mycobacterium abscessus DosRS two-component system controls a species-specific regulon required for adaptation to hypoxia. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1144210 (2023).

Shen, X. et al. Recurrent tuberculosis in an urban area in China: Relapse or exogenous reinfection? Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 103, 97–104 (2017).

Verver, S. et al. Rate of reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment is higher than rate of new tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171, 1430–1435 (2005).

Zhang, Z. X., Cherng, B. P. Z., Sng, L. H. & Tan, Y. E. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of non-tuberculous mycobacteria diseases in Singapore with a focus on pulmonary disease, 2012-2016. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 436 (2019).

Henao-Tamayo, M. et al. A mouse model of tuberculosis reinfection. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 92, 211–217 (2012).

Cultrone, D. et al. A zebrafish functional genomics model to investigate the role of human A20 variants in vivo. Sci. Rep. 10, 19085 (2020).

Gao, J. et al. LncRNA DINOR is a virulence factor and global regulator of stress responses in Candida auris. Nat. Microbiol 6, 842–851 (2021).

Knox, B. P. et al. Distinct innate immune phagocyte responses to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia and hyphae in zebrafish larvae. Eukaryot. Cell 13, 1266–1277 (2014).

Wright, K. et al. Mycobacterial infection-induced miR-206 inhibits protective neutrophil recruitment via the CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling axis. PLoS Pathog, (2021).

Matty, M. A., Oehlers, S. H. & Tobin, D. M. Live Imaging of Host-Pathogen Interactions in Zebrafish Larvae. Methods Mol. Biol. 1451, 207–223 (2016).

Liew, N. et al. Chytrid fungus infection in zebrafish demonstrates that the pathogen can parasitize non-amphibian vertebrate hosts. Nat. Commun. 8, 15048 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its individual research grant scheme (OFIRG22jul-0081) to S.H.O. A*STAR IMCB Aquarium Platform for expert zebrafish husbandry. Dr Eloise Ma and the A*STAR Microscopy Platform for microscopy assistance. Dr J Muse Davis for helpful discussion of live imaging techniques. Professors Lalita Ramakrishnan and Paul Edelstein for discussion of co-infection and sequential infections. Members of A*STAR ID Labs and the SG BUG community for discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DW performed most of the in vivo experiments and created the associated visualizations. MP performed the in vitro experiments and created the associated visualizations. YC analyzed the RNAseq dataset. PAL analyzed publicly available datasets setting the rationale for this study. EWLC prepared the fungi for in vivo experiments. YW and AS provided guidance and conceptual advice, and extensively edited the manuscript. SHO conceived the study, performed some of the in vivo experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wee, D., Pandey, M., Chen, Y. et al. Primary tuberculous mycobacterial granulomas provide a niche for superinfecting Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Commun 16, 10760 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65797-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65797-7