Abstract

Hundreds of human kinases, including PINK1—a protein kinase associated with familial Parkinson’s disease—are regulated by Hsp90 and its cochaperones. While previous studies have elucidated the mechanism of kinase loading into the Hsp90 machinery, the subsequent regulation of kinases by Hsp90 and its cochaperones remains poorly understood. In this study, using complexes obtained through PINK1 pulldown, we determine the cryo-EM structures of the human Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex at 2.84 Å, Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 at approximately 6 Å, and Hsp90- PINK1 at 2.98 Å. These structures, along with the bound nucleotide in the Hsp90 dimers of the three complexes, provide insights into the Hsp90 chaperone machinery for kinases and elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing cytosolic PINK1 regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs), as molecular chaperones, play a vital role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by safeguarding protein stability1. Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a key member of this family, with over 10% of total human cellular proteins relying on Hsp90 for folding or activation2,3. These client proteins encompass a wide variety of functions, including kinases, nuclear hormone receptors, transcription factors, and others4,5,6. Notable Hsp90 clients include kinases such as BRAF, Cdk4, ErbB2/Her2, and PINK1, along with transcription factors like HSF1, p53, and OCT4, as well as nuclear hormone receptors like the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and estrogen receptor (ER)4,5,6. As a result, Hsp90 is implicated in numerous diseases, making it a critical target for therapeutic interventions in cancer7.

The chaperoning of client proteins by the Hsp90 machinery is a highly coordinated process, involving various cochaperones such as Cdc378, Hop9, Aha110, p2311, FKBP51, and FKBP5212. After recognition by cochaperones, unfolded or inactive clients are loaded into the Hsp90 homodimer to form a complex8,13,14,15. ATP-driven conformational changes in Hsp90, in concert with the regulatory actions of cochaperones, facilitate the maturation of clients, which are subsequently released from the Hsp90 machinery to exert functions in the cytoplasm10,11,16. Different cochaperones are engaged at distinct stages of the Hsp90 chaperone cycle, participating in the chaperoning of specific client proteins4,7. The complexity of this process — including Hsp90-cochaperone-client binding modes, cochaperone-client specificity, ATP binding and hydrolysis, Hsp90 conformational changes, client maturation, and the precise timing of these events — has made it challenging to fully define the Hsp90 chaperone cycle.

Recent structural studies of Hsp90 in complex with cochaperones and clients have greatly advanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the Hsp90 chaperone circle. These include Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk417, Hsp90-Cdc37-Raf118, Hsp90- Cdc37-PP519,20, Hsp90-Cdc37-GC-C21, Hsp90-Hsp70-Hop-GR22, Hsp90-p23-GR23, Hsp90-FKBP51-p2324, Hsp90-FKBP51/FKBP52-GR25, and others. These structures have provided valuable insights, particularly for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), where several states along the chaperone circle have been captured, including client loading (Hsp90-Hsp70-Hop-GR), client maturation (Hsp90-p23-GR), and client activation (Hsp90-FKBP51/FKBP52-GR)22,23,25. These states provide a nearly complete picture of the GR chaperone circle, likely shared by other steroid hormone receptors (SHRs). However, for kinases, despite the availability of several structural snapshots, only the Cdc37-mediated client loading state has been resolved, with other stages remaining elusive. In addition, it remains unclear whether cochaperone regulation of SHRs extends to kinases. For example, FKBP51 and FKBP52 are known to act as co-chaperones for various SHRs26, stabilizing the ligand-bound state independent of their peptidyl-Prolyl isomerase (PPIase) activity25. Yet, no interaction between FKBP51/FKBP52 and kinases has been reported, with the exception of a few cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs)27. Moreover, unlike the dispensable PPIase activity of FKBP52 in SHRs27 maturation, the PPIase activity of FKBP51 appears to play a critical role in regulating CDK428. Thus, capturing additional structural states beyond Cdc37-mediated client loading is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of how kinases are regulated by the Hsp90 machinery.

PINK1, a kinase closely associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD), is also a client of Hsp9029. Mutations in the PINK1 gene lead to early-onset autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease30. Human PINK1 (hPINK1) consists of 581 residues and includes four domains: an N-terminal mitochondrial-targeting region (1-110 a.a.) containing a mitochondrial-targeting sequence (MTS) and a transmembrane domain (TM), an N- terminal helix extension (NTE, 111-155 a.a.), a catalytic kinase domain (156-510 a.a.) with three insertions, and a C-terminal extension (CTE, 511–581 a.a.)31,32,33. PINK1’s well-established function in mitochondrial quality control involves its stabilization on the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) upon mitochondrial damage and loss of membrane potential34. There, PINK1 dimerizes, activates35,36,37,38, and phosphorylates ubiquitin, thereby activating the E3 ubiquitin ligase PARKIN and initiating mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria39,40,41. In contrast, under basal conditions, PINK1 is processed in the mitochondrial intermembrane space and matrix into a cleaved product (104-581 a.a.), which is exported to the cytosol for additional functions or degradation42,43,44,45,46. While the canonical role of full-length PINK1 on the MOM has been extensively studied, increasing evidence suggests that the cleaved PINK1 also acts as a multifunctional kinase in the cytosol29,42,47,48,49,50.

Given the strong association between PINK1 mutations and Parkinson’s disease, understanding the molecular mechanisms of PINK1 regulation is critical for both elucidating disease pathology and developing potential therapies. Activation mechanisms of PINK1 have been explored using insect variants such as Tribolium castaneum PINK1 (TcPINK1) and Pediculus humanus corporis PINK1 (PhPINK1)31,33,51, revealing that PINK1 is activated through transactivation between two PINK1 monomers in a homodimer. And intramolecular interaction between the NTE and CTE regions is necessary for the stabilization of human PINK1 at the TOM complex, followed by autophosphorylation at Ser228, which is crucial for activation51,52. While this transactivation mechanism explains how PINK1’s activation on the MOM, the regulation and activation of cytosolic PINK1 remains poorly understood.

Previous studies have demonstrated that cytosolic PINK1 is regulated by the Hsp90 chaperone machinery45,53. Inhibition of Hsp90 with specific inhibitors such as geldanamycin significantly reduces cytosolic PINK1 levels, highlighting a direct link between chaperone activity and PINK1 stability29,45.

In this work, we determined cryo-EM structures of the human Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex, Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex, and the Hsp90-PINK1 complex. These structures provide evidence that Hsp90 and Cdc37 recognize and bind to PINK1. Furthermore, this study identifies the interaction between Hsp90, FKBP51, and PINK1, revealing the regulatory role of Hsp90 and FKBP51 in modulating PINK1. These findings establish a crucial foundation for understanding the role of Hsp90 in kinase regulation and open different avenues for exploring Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis.

Results

Overexpression of cytosolic hPINK1 induces formation of multiple hPINK1 complexes

To investigate the regulatory mechanism of cytosolic PINK1, human PINK1(110-581 a.a.) with a C-terminal Flag tag was overexpressed in HEK293F cells and purified through Flag affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration. Mass spectrometry analysis of the resulting protein bands identified Hsp90, Cdc37, and FKBP51, along with the overexpressed PINK1, indicating that endogenous Hsp90 and its cochaperones Cdc37 and FKBP51 were pulled down by PINK1 (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b).

Cryo-EM analysis revealed the presence of multiple hPINK1 complexes, including Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1, Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1, and Hsp90-PINK1 (Supplementary Figs. 1c, d, 2). These findings are in agreement with previous reports that cytosolic PINK1 is regulated by Hsp90 and its cochaperones45,53. The distinct complexes captured here represent different stages of PINK1 regulation by the Hsp90 machinery.

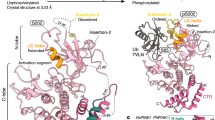

Structure of Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 reveals the mechanism of PINK1 loading

The structure of the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex was determined at an atomic resolution of 2.84 Å (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2a, b, e and Supplementary Table 1). The complex consists of a dimeric Hsp90 core, with the two protomers called Hsp90A and Hsp90B. A segment of PINK1 passes through the central lumen of the Hsp90 dimer, while Cdc37 wraps around the Hsp90B protomer. This arrangement adopts a closed conformation, similar to previously reported structures of Hsp90-Cdc37 complexes associated with CDK4, Raf1, Braf, and other client proteins18,20,54, representing a loading state of PINK1 regulated by the Hsp90 machinery.

a Composite cryo-EM map of the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex in front and back views. b Atomic model of the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex represented as a cartoon, with boxes corresponding to the details shown in panels (d–h). c Comparison of the PINK1 structure in the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex and the Pediculus humanus corporis PINK1 (PDB: 6EQI), with PhPINK1 colored in pink and PINK1 in the Hsp90- Cdc37-PINK1 complex colored in yellow. Ins3 and β5 of phPINK1 is colored in red. d Interface between the Hsp90 lumen and the PINK1 polypeptide, with Hsp90A and Hsp90B depicted by the density map and PINK1 shown using a transparent map alongside a cartoon and stick model. e Interface of the Hsp90 lumen and the PINK1 polypeptide, with Hsp90 lumen shown in surface representation colored by hydrophobicity, and five hydrophobic residues of PINK1 depicted in stick format. f Interface between Hsp90B and the PINK1 polypeptide and αD helix. g Detailed view of the interaction between the Cdc37 N-terminal domain and the Hsp90 dimer, with Hsp90 dimer shown in surface representation, and the coiled-coil domain of Cdc37 hidden for clarity. The phosphorylated S13 is labeled as pS13. h Details of the interface between the Cdc37 N-terminal hook loop and the PINK1 C-lobe. Hsp90A is colored cyan, Hsp90B marine, PINK1 yellow, and Cdc37 salmon. The CTE domain of PINK1 is highlighted in green.

A polypeptide segment of PINK1, spanning the Ins3 and β5 region of the N-lobe, extends into the lumen formed by the Hsp90 dimer (Fig. 1c, d). The binding of this polypeptide to the Hsp90 lumen is primarily mediated by hydrophobic interactions, notably between five consecutive hydrophobic residues (L314 to M318), with L316 and M318 inserting into hydrophobic cavities of Hsp90B (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition to these hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds contribute to the interaction between PINK1 and Hsp90. Specifically, residues L316, R319, N320, Y321 from the polypeptide loop, along with Q327 from the αD helix, form hydrogen bonds with Hsp90B residues Y528, Q531, K534, and Y604 (Fig. 1f). In contrast, only one hydrogen bond is observed between T313 in PINK1 and L619 in Hsp90A (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Similar polypeptide structures have been observed in other Hsp90-Cdc37-client complexes, such as Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk4 (PDB: 5FWK), Hsp90-Cdc37-Raf1 (PDB: 7Z38), and Hsp90-Cdc37-Braf (PDB: 7ZR0) (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d). Structural alignment of these polypeptides reveals similar hydrophobic characteristics, though no conserved sequence motifs are shared among Hsp90 clients2 (Supplementary Fig. 3e).

The interaction between the PINK1 polypeptide and Hsp90B is stronger than that with Hsp90A, suggesting asymmetric binding of PINK1 to the two Hsp90 protomers. Consequently, the conformation of the Hsp90B region interacting with PINK1 differs from that of the corresponding region in Hsp90A. Specifically, the amphipathic loop (L351-K358) in the lumen of Hsp90B undergoes a flip compared to its counterpart in Hsp90A (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In addition, the region spanning R620-K632 in Hsp90B shifts away to accommodate binding of PINK1 β7-β8, unlike its position in Hsp90A (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

The density of the PINK1 C-lobe is well-defined, although the activation loop (388- 430 a.a.) is not observed, indicating its flexibility. When compared to previously reported structures, the C-lobe of hPINK1 in the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex aligns closely with those of TcPINK1 and PhPINK1, suggesting that the PINK1 C-lobe structure is highly conserved across species (Supplementary Fig. 5). A notable conformational change is observed in PINK1 CTE, which includes αJ, αK, αL, and αM, where the αK helix is displaced due to occupation by Hsp90A (Supplementary Fig. 6). This suggests that the conformation of PINK1 CTE is flexible, rather than fixed. In contrast to the well-defined density of the PINK1 C-lobe, the N-lobe density is absent, similar to other Hsp90-Cdc37-kinase complexes17,18,19, implying that the N-lobe is either highly flexible or disordered. This is consistent with the role of Cdc37 in the early stages of the Hsp90 chaperone cycle, where it escorts and loads an unfolded kinase onto the Hsp90 dimer.

Unlike other kinases, PINK1 possesses an additional CTE domain following the C-lobe, which causes the C-lobe to adopt a tilted conformation compared to the kinase C-lobes in other Hsp90-Cdc37-kinase complexes (Supplementary Fig. 7a). In addition, two interactions between PINK1 and Hsp90 are identified: one is the hydrophobic interaction between P374 in PINK1 and W606 in Hsp90B, and the other one is cation–π interaction between K555 in PINK1 and W320 in Hsp90A (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c).

The configuration of Cdc37 within the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex closely resembles that of previously reported Hsp90-Cdc37-client complexes. The coiled-coil N-terminal domain (NTD) of Cdc37 is situated adjacent to the PINK1 C-lobe, while the Middle Domain (MD) packs against the opposing face of the Hsp90 dimer (Fig. 1b). The Cdc37 N-terminal α helix is inserted into the cleft between Hsp90A and Hsp90B, binding through a combination of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 8a). Specifically, Ser13 in Cdc37 is phosphorylated and forms electrostatic or hydrogen-bonding interactions with R32, H33, R36 in the NTD coiled-coil of Cdc37, and K414 in Hsp90B (Supplementary Fig. 8b). The residues L119-N130 form an extended β-strand that binds to the central β-sheet of Hsp90B’s MD via hydrogen bonds (Supplementary Fig. 8c). The density of the Cdc37 MD is less well-defined, indicating a high degree of flexibility or multiple conformational states.

Cdc37’s N-terminal residues (E18-R32), including a hook loop (E18-D24), interact with the PINK1 C-lobe in a manner similar to the interaction between PINK1’s N-lobe and C-lobe (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 9a), involving extensive hydrophobic contacts and hydrogen bonds. Notably, this interaction, particularly the steric clash caused by W31 of Cdc37, alters the conformation of PINK1’s DFG motif, which is critical for its catalytic activity. As a result, the DFG motif adopts a conformation distinct from that observed in folded PhPINK1 and TcPINK1 (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Structure of Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 reveals the involvement of FKBP51 in PINK1 folding

FKBP51 is a cochaperone for SHRs, known to function in the later stages of the Hsp90 chaperone cycle to antagonize their activation25,27. While FKBP51 is rarely implicated in kinase activation, it has been shown to interact with a few CDKs27. Surprisingly, endogenous FKBP51 was pulled down by PINK1-Flag, forming a tetrameric complex with Hsp90 and PINK1 (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that FKBP51 plays a role in the regulation of PINK1, and potentially other kinases.

The structure of the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex was resolved, with the Hsp90 dimer core determined at a resolution of approximately 5-6 Å. In contrast, the resolutions for FKBP51 and the PINK1 N-lobe are lower, around 8-10 Å, indicating less precise structural details for these regions (Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2d, g and Supplementary Table 1). The Hsp90 dimer adopts a closed conformation and serves as the scaffold for the complex. In this structure, the N-lobe of PINK1 is visible, and the PINK1 kinase adopts a conformation with its N- and C- lobes positioned on opposite sides of the Hsp90 dimer (Fig. 2b). The polypeptide connecting the N-lobe and C-lobe traverses the lumen of the Hsp90 dimer, adopting a conformation similar to that observed in the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex (Figs. 1d, 2c). The three domains of FKBP51 — FK1 (13-136 a.a.), FK2 (146-253 a.a.), and the C-terminal TRP domain (260-421 a.a.) — are all clearly discernable. The TRP domain binds to the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the Hsp90 dimer, the FK1 domain interacts with the N-lobe of PINK1, and the FK2 domain bridges the FK1 and TRP domains. Due to the limited resolution, our model does not provide sufficient detail to analyze specific amino acid interactions.

a Composite cryo-EM map of the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex in front and back view. b Atomic model of the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex in cartoon representation. c The interface of Hsp90 lumen and PINK1 polypeptide, with Hsp90 lumen shown in surface representation and PINK1 shown in stick. d The detail view of the TPR domain of FKBP51 interacts with Hsp90. e The interface of the FK1 domain of FKBP51 and the PINK1 N-lobe is represented in cartoon mode, superimposed with the electron density. Hsp90A, cyan; Hsp90B, marine; PINK1, yellow; Cdc37, salmon.

The incorporation of FKBP51 into the Hsp90-PINK1 chaperone machinery is similar to that observed in the Hsp90-FKBP51-GR complex (PDB: 8FFW), where the N-lobe of PINK1 occupies the same position as the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of GR (Supplementary Fig. 10a). In contrast to the Hsp90-FKBP51-P23 complex, which lacks a client protein, the FK1 domain of FKBP51 in the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex shifts outwards to accommodate the N-lobe of PINK1 (Supplementary Fig. 10b). In addition, the FK2 domain moves outwards, and the N-terminal part of the TRP domain tilts to facilitate the movement of FK1. These structural shifts suggest significant conformational changes in FKBP51 domains upon client protein binding. Similar to Hsp90-FKBP51-GR complex and Hsp90-FKBP51-P23, the H7 extension (H7e) located in the final helix of the TRP domain is twisted to accommodate the CTD groove of Hsp90 (Fig. 2d).

A notable feature of the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex, compared to the Hsp90- Cdc37-PINK1 complex, is the visualization of the PINK1 N-lobe, although it was in a low resolution at about 10 Å (Figs. 1a, b, 2a, b), which suggests a more stable conformation of the client kinase N-lobe compared to Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex. This stability is likely facilitated by FKBP51’s involvement in promoting PINK1 folding. The FK1 domain primarily exhibits peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPIase) activity, allowing it to facilitate the cis-trans isomerization of peptide bonds preceding proline residues in substrate proteins27, thereby ensuring proper protein folding and function55. The P-loop of FK1 domain is frequently involved in binding substrates during this enzymatic catalysis25 and in this model is located at the N-terminal binding site of PINK1 (Fig. 2e). Thus, the interaction between the FK1 domain of FKBP51 and the N-lobe of PINK1 likely promotes the proper folding of the PINK1 N-lobe via FKBP51’s PPIase activity, akin to the role of Hsp90-FKBP51 in stabilizing the Tau protein56.

Structure of Hsp90-PINK1 reveals a folded N-lobe of PINK1

A class of particles containing only Hsp90 and PINK1 was obtained through 2D and 3D classification during data processing. The map resolution was refined to 2.98 Å, revealing the binding of Hsp90 with the client protein PINK1 in the absence of cochaperones (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2c, f and Supplementary Table 1).

a Composite cryo-EM map of the Hsp90-PINK1 complex in front and back view. Hsp90A, cyan; Hsp90B, marine; PINK1, yellow. b Atomic model of the Hsp90-PINK1 complex in cartoon representation. c Overall comparison of Hsp90-PINK1 complex, Hsp90- Cdc37-PINK1 complex and Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex in front view and back view. For the Hsp90-PINK1 complex, Hsp90A is colored in cyan, Hsp90B is colored in marine, and PINK1 is colored in yellow. Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex is colored in orange, and Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex is colored in gray. d The structural comparison of PINK1 C-lobe. e The superimposed of PINK1 N-lobe and Cdc37 Middle Domain (Cdc37-MD).

The conformation of the core Hsp90 dimer in this complex is similar to that observed in the two tetrameric complexes described above (Fig. 3c). The core structure of the Hsp90 dimer remains consistent with that in more complex assemblies, underscoring its role as a stabilizing scaffold. The PINK1 C-lobe retains its structural conformation, as seen in the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 and Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complexes, with minimal changes (Fig. 3d). Notably, at the interface between Cdc37 hook loop and PINK1, the αE and αL helices, as well as β7 and β8 of PINK1, show little conformational shift in the presence or absence of Cdc37 (Supplementary Fig. 11a), indicating that Cdc37 binding to the PINK1 C-lobe does not significantly affect its structure stability. Therefore, the Cdc37 hook loop, which mimics the loop in the PINK1 N-lobe that interacts with the C-lobe, likely functions primarily to recognize and recruit the client kinase to the Hsp90 machinery, rather than stabilizing it within the complex. Meanwhile, a slight conformational change is observed in the β7-β8 loop of PINK1, causing a shift in the positions of residues from R620 to K632 in Hsp90B (Supplementary Fig. 11b).

The polypeptide segment of PINK1 interacting with the Hsp90 lumen adopts a similar conformation as seen in the other two complexes, displaying the same separated N-lobe and C-lobe arrangement (Supplementary Fig. 11c). The consistency of the PINK1 C-lobe and the polypeptide crossing the Hsp90 lumen across different Hsp90-PINK1 complexes suggests that the well-folded kinase C-lobe is not a target for modulation by the Hsp90 machinery. Moreover, the stable interaction between the polypeptide and the Hsp90 lumen is likely maintained throughout the chaperone circle until the release of the mature client, in contrast to the sliding of the polypeptide of GR in the Hsp90 lumen during GR activation25.

As observed in the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex, the N-lobe of PINK1 is also visible in the Hsp90-PINK1 complex (Figs. 2a, b, 3a, b). The approximately 3 Å local resolution of the PINK1 N-lobe (Supplementary Fig. 2c) indicates that this domain is well-folded, rather than unfolded or disordered. Superimposition of the Hsp90-PINK1 complex, Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex, and Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex shows that the location and orientation of the PINK1 N-lobe are identical in the Hsp90-PINK1 and Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complexes, with the N-lobe overlapping well with the Cdc37 middle domain (MD) (Fig. 3d, e). This suggests a potential conflict between the positions of the Cdc37 MD and the PINK1 N-lobe. Consequently, the folding of the PINK1 N-lobe could only occur after the release or displacement of Cdc37.

ADP binds to the Hsp90 dimers in all PINK1-bound complexes

In the Hsp90 chaperone cycle, the binding of ATP to the N-terminal domain (NTD) of Hsp90 is believed to stabilize its closed dimeric state throughout the process. ATP hydrolysis leads to a transient ADP-bound compact state, which then relaxes to an open state upon the release of ADP4,17,57,58. Supporting this hypothesis, all Hsp90- cochaperone-client structures reported thus far contain ATP or ADP-molybdate (ATP mimics) in each of the Hsp90 dimers. However, these structures were obtained through in vitro reconstitution, with molybdate used to stabilize the complexes. It remains unclear whether the ATP/ADP-molybdate-bound states represent the endogenous state of the Hsp90 machinery. To address this, we analyzed the nucleotide binding in all three Hsp90 complexes derived from PINK1 pulldown with endogenous proteins.

Unexpectedly, in all three complexes — Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1, Hsp90-FKBP51- PINK1, and Hsp90-PINK1 — each of the Hsp90 protomers binds an intrinsic ADP molecule at its NTD (Fig. 4), rather than ATP or ADP-molybdate (ATP mimics) as seen in previously reported Hsp90-cochaperone-client structures. The density for ADP in these complexes is unambiguously discernable and does not show any density for the γ-phosphate of ATP (Fig. 4a–c), resembling the ADP density observed in the mitochondrial Hsp90 homolog, TRAP1 (PDB: 5TVX) (Fig. 4d). In contrast, other Hsp90 complexes, such as Hsp90-Cdc37-CDK454 (PDB: 5FWK) and Hsp90-FKBP51- GR25 (PDB: 8FFW), clearly display the density for the γ-phosphate of ATP or molybdate, similar to the density of unhydrolyzed ATP in TRAP1 (PDB: 5TVU) (Fig. 4e–g)59. Furthermore, two conserved residues critical for ATP hydrolysis, E47 and R400 (E42 and R392 in another Hsp90 homolog and E130 and R417 in TRAP1), form hydrogen bonds with ATP. However, these hydrogen bonds are disrupted when ATP is hydrolyzed to ADP, as seen by the disconnected density between the nucleotides and the conserved arginine residues in the PINK1-bound Hsp90 dimers and ADP-bound TRAP1 (Fig. 4a–d). The presence of ADP in the nucleotide-binding pocket of Hsp90 in all PINK1-bound Hsp90 complexes suggests that ADP, rather than ATP, stabilizes the closed state of Hsp90 in endogenous conditions. In addition, ATP hydrolysis likely occurs at an early stage of the Hsp90 chaperone cycle — at least prior to the formation of the stable client-loading complex (Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1) — but not immediately before client release.

a The density map of ADP and the conserved residues that are crucial for nucleotide binding in the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex (colored in green). b The density map of ADP and the surrounding conserved residues in the Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex (colored in brown). c The density map of ADP and the surrounding conserved residues in the Hsp90 -PINK1 complex (colored in dark brown). d The density map of ADP and the surrounding conserved residues observed in the mitochondrial Hsp90 homolog, TRAP1 (PDB: 5TVX) (colored in pink). e The density map of ATP and the surrounding conserved residues observed in the mitochondrial Hsp90 homolog, TRAP1 (PDB: 5TVU) (colored in light green). f The density map of ATP and the surrounding conserved residues observed in the Hsp90-FKBP51-GR (PDB: 8FFW) (colored in cyan blue). g The density map of ATP and the surrounding conserved residues observed in the Hsp90-Cdc37-CDK4 complex (PDB: 5FWK) (colored in blue). The nucleotides in the above structures are colored in purple red. The black dash lines represent hydrogen bonds.

These findings align with kinetic analyses of Hsp90 ATPase activity, which indicate that the rate-limiting step of ATP hydrolysis is the conformational change upon ATP binding, rather than ATP hydrolysis itself60,61. ATP binding triggers a complex set of conformational changes in the Hsp90 dimer, including closure of the N-terminal lid of each protomer, which traps the bound ATP and enables N-terminal dimerization, an N- terminal β-strand exchange between the two protomers, association of the Middle Domain (MD) and NTD of each protomer, and release of the catalytic loop containing R400 from the MD58. Following these transitions, the Hsp90 protomers are primed for the catalytically active state, where R400 interacts with the trapped ATP molecules62. These conformational transitions, induced by ATP binding, are orders of magnitude slower than the ATP hydrolysis61. Therefore, in the stable Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex, where these transitions have been completed and R400 is accessible, ATP readily hydrolyzes into ADP rather than resisting hydrolysis.

Furthermore, ADP binds to Hsp90 through multiple hydrogen bonds, stabilizing the nucleotide-binding pocket (Supplementary Fig. 12a), and lacks the driving force required to trigger an open-state transition. The interactions between ADP and Hsp90 are highly conserved when compared to the closed ADP-bound TRAP1 structure (PDB: 5TVX) (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Notably, the residues involved in this interaction within Hsp90 are also conserved across different species (Supplementary Fig. 12b), suggesting that the mechanism of ATP hydrolysis and stabilization of the closed state by ADP is widely conserved.

Regulation of PINK1 by Hsp90 machinery occurs after the cleavage of its N-terminus

It is unclear whether the regulation of cytosolic PINK1 by the Hsp90 machinery occurs prior to PINK1 translocation to the mitochondria or after its N-terminus is cleaved and released into the cytoplasm. To address this, we expressed full-length PINK1 using the same method as for the truncated PINK1 (110-581 a.a.). During the purification process, we homogenized the cells and then subjected them to centrifugation to separate the mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions. Each fraction was purified separately, using Flag affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography.

The yield of purified cytoplasmic PINK1 was significantly higher than that of the mitochondrial fraction. Both SDS-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography profiles of the cytoplasmic sample closely resembled those of truncated PINK1 (110-581 a.a.), suggesting that the expressed full-length PINK1 undergoes cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). In addition, Hsp90, Cdc37, and FKBP51 were co-purified with PINK1 (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). To confirm the length of the purified PINK1, we performed Western blotting using a PINK1-specific antibody. The results showed that the majority of cytoplasmic PINK1 matched the size of the truncated PINK1, whereas the samples purified from mitochondria include both full-length and truncated forms (Supplementary Fig. 13c). These results suggest that the formation of complexes between PINK1 and the Hsp90 machinery occurs primarily after the N-terminal cleavage and subsequent release of PINK1 into the cytosol. The presence of truncated PINK1 in the mitochondrial fraction may result from residual cytoplasmic contamination during mitochondrial isolation or from newly cleaved PINK1 not yet fully released. Therefore, the co-purified Hsp90 and its co-chaperones are likely associated with the cleaved PINK1. Importantly, the majority of purified PINK1 was cytoplasmic, supporting the conclusion that it is the cleaved PINK1 that is regulated by the Hsp90 machinery.

Discussion

Hsp90 binds to approximately 60% of the human kinome to promote their folding and stabilization3. After client kinases, in their unfolded state, are recognized by Cdc37 and loaded into the Hsp90 dimer, they undergo a maturation process with the help of cochaperones until they are fully folded and subsequently released. While many structures of the loading state, consisting of Hsp90, Cdc37, and the client kinases, have been resolved17,18,19, little is known about the maturation process. In this study, using Hsp90-cochaperone complexes pulled down with hPINK1, we reveal two states — Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 and Hsp90-PINK1 (Figs. 2, 3) — in addition to the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 loading state (Fig. 1) within the Hsp90-kinase chaperone machinery.

In all three complexes, the PINK1 N-lobe and C-lobe are separated by the Hsp90 dimer, with the stretched polypeptide corresponding to the Ins3 and β5 regions lying in the lumen formed by the Hsp90 dimer. While the C-lobe and polypeptide show structural and positional consistency across the three complexes, the N-lobe undergoes folding from a disordered loading state in Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 to a folded mature state in Hsp90-PINK1. The Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 complex likely represents a premature state where FKBP51 aids in the folding of the PINK1 N-lobe. The role of FKBP51 in the late-stage folding of PINK1 aligns with its function in the Hsp90-GR chaperone cycle, where FKBP51 helps advance GR maturation25.

An important aspect of the Hsp90 chaperone circle is the binding and hydrolysis of ATP, as the closure and opening of the Hsp90 homodimer are believed to be driven by ATP binding and hydrolysis, respectively4,57,58. However, in this study, we reveal that ADP, the hydrolysis product of ATP, binds in all Hsp90 complexes (Fig. 4). These robust data, derived from endogenous samples, suggest that, rather than opening the Hsp90 homodimer, the ATP hydrolysis leads to a stably closed state. Interestingly, ADP-bound states have been reported for HtpG (E.coli Hsp90), displaying a tetrameric parallel-like conformation by crystallography57, and in a compact conformation by CryoEM and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)63,64. The compact conformation is also observed for yeast and human Hsp90 in the presence of ADP after cross-linking64. Similarly, the endoplasmic reticulum Hsp90, GRP94, also binds ADP in a compact conformation65. Thus, the ADP-bound Hsp90 exhibits a range of conformations, including the parallel-like conformation observed in HtpG, the compact conformation seen in GRP94, the closed conformation found in TRAP1 and the structure in this paper (Supplementary Fig. 14). It remains uncertain whether these structures depict a sequence of conformational changes following ATP hydrolysis or if they are specific to certain species.

Recent studies have reported that, in damaged mitochondria, a super-complex forms comprising full-length PINK1, the TOM complex, and VDAC66. Structural analyses explicitly demonstrate how PINK1 stacks on the mitochondrial surface and interacts with the TOM complex and VDAC. Therefore, it is clear that full-length PINK1 is recognized and interacts with the TOM complex and VDAC on the mitochondria.

Although a high-resolution structure of PINK1 within this complex has been resolved, the authors note that this reconstruction was derived from approximately one-third of all particles. In about two-thirds of the particles, the N-lobe of PINK1’s kinase domain appears disordered66. This observation leads to the hypothesis that, in healthy mitochondria, full-length PINK1 interacts with the TOM complex and VDAC, with its N-terminus passing through Tom40 and being cleaved by PARL and MPP. During this process, most of the kinase N-lobe of PINK1 remains disordered. Upon release into the cytosol, Cdc37 can recognize this disordered PINK1 and facilitate its interaction with Hsp90.

Combining the many structures revealed in this work with previous studies of the Hsp90 chaperone circle17,67,68,69, we propose a model illustrating the chaperone cycle for PINK1 regulation (Fig. 5). In healthy mitochondria, PINK1 does not accumulate on the mitochondrial surface; instead, when PINK1 is recognized and bound by TOM-VDAC complex, its N-terminus is transported into MTS via Tom40, and cleaved by PARL and MPP. The cleaved PINK1 is then released into the cytosol. Most of the PINK1 have a disordered N-lobe, which is recognized and bound by Cdc37 in the cytosol. The PINK1-Cdc37 complex is then loaded onto the open state of the Hsp90 dimer. ATP binding to Hsp90 induces a conformational change in the Hsp90 NTD, promoting the transition of the Hsp90 dimer from the open state to a closed state. ATP is then hydrolyzed to ADP, resulting in the formation of a stable Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 loading complex (Fig. 1a, b). After PINK1 is loaded, Cdc37 dissociates, and FKBP51 enters the chaperone cycle, forming the Hsp90-FKBP51- PINK1 pre-mature complex (Fig. 2a, b), where FKBP51 binds to the N-lobe of PINK1 to promote its folding. Once folding is completed, FKBP51 dissociates from the complex, leaving the Hsp90-PINK1 maturation complex (Fig. 3a, b). Finally, upon release of ADP, the Hsp90 dimer opens, and folded PINK1 is released into the cytoplasm. The released PINK1 retains functional potential and can be activated in the presence of ATP, Mg2+, and ubiquitin (Supplementary Fig. 15). This model provides insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying PINK1 regulation by Hsp90 and its cochaperones and offers a structural framework for understanding the regulation of other kinases by Hsp90, as they share conserved structures consisting of the N-lobe and C-lobe, and the Cdc37 cochaperone.

In its unfolded state, PINK1 is recognized and bound by Cdc37. The PINK1-Cdc37 complex is subsequently loaded onto the Hsp90 dimer in its open conformation. ATP binding to the N-terminal domains (NTDs) of the Hsp90 dimer induces conformational changes, resulting in the formation of a closed Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 complex and hydrolysis of the ATP molecules. Once PINK1 is fully loaded, Cdc37 dissociates, and FKBP51 enters the chaperone cycle. FKBP51 binds to the N-lobe of PINK1, promoting its proper folding. Upon completion of folding, FKBP51 dissociates from the complex, leaving the Hsp90- PINK1 maturation complex. Finally, upon release of ADP, the Hsp90 dimer opens, and the fully folded PINK1 is released into the cytoplasm. Cdc37 is shown in salmon, Hsp90 in cyan and blue, PINK1 in pink, and FKBP51 in blue-green.

PINK1 mutations represent the second most common cause of autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease, which is characterized by progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) of the midbrain70,71. While the role of the mitochondria-localized PINK1 is well-studied, emerging evidence supports the role of cytosolic PINK1 in neuron protection and differentiation47,49,72,73. Thus, insights into the molecular regulation of cytosolic PINK1 by the Hsp90 chaperone machinery provide different directions for understanding PD pathogenicity. Indeed, some PD mutations of PINK1, such as G309D and T313M, may cause disease by disrupting the interaction with Hsp90 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Furthermore, attempts to assess binding between endogenous PINK1 and Hsp90 using PINK1 KO HeLa cells did not yield evidence of an endogenous PINK1–Hsp90 complex under standard growth conditions. Considering PINK1’s function, we propose that the regulation of cytosolic PINK1 by the Hsp90 machinery may occur specifically in certain cell types, such as neuronal cells, or under specific physiological conditions. This warrants further in-depth investigation. Further study of the association between PINK1 regulation by the Hsp90 machinery and PD pathogenesis could make the specific interactions between PINK1 and Hsp90-cochaperones a promising target for PD treatment.

Methods

Cell culture

The human PINK1 (110 a.a. − 581 a.a.) was synthesized by General Biol Co., Ltd, using a 3 × Flag CMV vector that incorporates a 3 × Flag tag at the C-terminus. Human 293 F cells (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat#11625019.) were cultured in SMM 293-TII medium (Sino Biological) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, utilizing a ZCZY-CS8 shaker from Shanghai Zhichu Instrument Co., Ltd. Plasmid transfection was initiated when the cell density reached 2 × 106 cells/ml. Following a 48-hour incubation period, cells were collected and washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), composed of 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.4 mM KH2PO4, adjusted to pH 7.2. The resulting cell pellets were subsequently flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C.

Mitochondria removal

The cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A, which contained 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.4), 200 mM sorbitol, 70 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2 mg/ml BSA, and 0.5 mM PMSF, and incubated for one hour. The resulting suspension was then subjected to homogenization using a Sigma homogenizer while maintaining the mixture on ice. After homogenization, the mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min to remove mitochondria and all other cell debris. The supernatant containing the cytoplasmic fraction was retained for subsequent purification steps.

PINK1 complex purification

The supernatant was combined with Sigma Flag beads and incubated for one hour at 4 °C. The beads were subsequently loaded into the gravity column for protein washing and elution. The washing buffer was composed of 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 10% glycerol (v/v). After washing 20 column volumes of washing buffer, the PINK1 complex was eluted from the beads using the washing buffer supplemented with Flag peptide synthesized from GenScript. For further purification, the complex underwent gel filtration using a Superose 6 Increase 3.2/300 GL column from GE Healthcare. The resulting fractions were collected for SDS-PAGE analysis and preparation of cryo-samples.

Plasmid construction

The plasmid for PINK1 (110-581 a.a.) and PINK1-FL were constructed to the 3 × Flag PCMV vector. Plasmid were conducted by the PerfectStart Green PCR SuperMix (Trans). And the primer sequences were as follows:

PINK1 (110-581 a.a.)-F: ACCAAGCTTATGCTCATCGAGGAAAAACAG

PINK1 (110-581 a.a.)-R: CACCGTCATGGTCTTTGTAGTCCAGGGCTGCC

PINK1-FL-3×Flag-F: GAATTAACCAAGCTTATGGCGGTGCGACAGGCG

PINK1-FL-3×Flag-R: CACCGTCATGGTCTTTGTAGTCCAGGGCTGCC

PINK1-full-length purification

We expressed full-length PINK1 by HEK293F cells in the same method as the truncated PINK1. The full-length PINK1 plasmid was constructed using a CMV vector that incorporates a 3 × Flag tag at the C-terminus (PINK1-FL) and was transfected into 293F cells. Following transfection 48 h, cells were harvested, resuspended in an osmotic swelling buffer, and homogenized. The homogenate was then subjected to centrifugation to separate the mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions. For the cytoplasmic proteins, purification was performed using Flag affinity chromatography, followed by size exclusion chromatography with a Superdex 200 Increase 3.2/300 GL column (Cytiva). The mitochondrial fraction was solubilized in a buffer containing 1% digitonin (DDM) for 1 h, then centrifuged to remove insoluble debris. The solubilized mitochondrial proteins were subsequently purified using Flag affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography with a Superdex 200 Increase 3.2/300 GL column. During the purification process, the buffer was maintained with 0.1% DDM.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection

For the cryo-EM sample, 4 μl protein was applied to the grid (R 1.2/1.3 Au, 300 mesh, Quantifoil). The bolted time was 4 s by FEI Mark IV Vitrobot and then plunged to liquid ethane. The dataset of PINK1-3×Flag was collected using a Titan Krios (Titan 3) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), operating at 300 kV with a Gatan K3 Summit direct electron detector and GIF Quantum imaging energy filter. The dataset of PINK1-3 × Flag was collected at a nominal magnification of × 81,000, with a pixel size of 0.8697 Å/pixel and defocus values ranging from − 1.5 μm to − 1.9 μm. The total dose rate on the detector was approximately 50 electrons/Å2, with a total exposure time of 2.13 s. Each micrograph stack contains 32 frames, and each micrograph was corrected for sub-region motion correction and dose weighted using UCSF MotionCor274.

Single particle image processing

11,500 micrographs were collected for the dataset of PINK1-3×Flag. cryoSPARC75 was used for Patch CTF first. After particle picking by blob picker, 9,615,299 particles were obtained and were extracted with bin4. 2D classification was performed, and all good classes were selected for ab-initio reconstruction. Two good classes were selected after ab-initio reconstruction. The best class with 70.5% was redone for ab-initio reconstruction. Three good classes with 57.2%, 26.2% and 11.53% were extracted with bin2. Refinement was performed for each class. 2D classification was done to each class again. All good classes were selected and extracted with bin1. Refinement was performed with C1 symmetry.

The resolution of Hsp90-PINK1 is 2.98 Å. The resolution of Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 is 4.43 Å. A mask was created for the region of FKBP51. Particle subtraction was performed for this region, and done refinement. The resolution of FKBP51 from Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK is 4.72 Å. The resolution of Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 is 2.84 Å. A mask was created for Cdc37 and redone refinement. The resolution of Cdc37 from Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 is 2.66 Å. All structures above are based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) 0.143 criteria.

Model building and refinement

The initial model of human Hsp90α, Cdc37, FKBP51 and PINK1 were downloaded from the AlphaFold database. To build the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1, Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 and Hsp90-PINK1 structures, the unrefined Hsp90, Cdc37, FKBP51 and PINK1 models were first docked into the Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1, Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 and Hsp90-PINK1 density maps using UCSF Chimera76 fit-in-map function. Additional adjustments to the backbone and side chains for the models were performed manually in COOT77, residue by residue. An ADP density was identified in each of the Hsp90 dimer. The Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1, Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 and Hsp90-PINK1 structures were subjected to real space refinement in PHENIX78. The geometries of final models were validated with a comprehensive model validation section in PHENIX, and detailed information was listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Kinase activation assay

Kinase activity was assessed using the Kinase-Lumi™ Max Luminescent Kinase Assay Kit (Beyotime, S0158S). Purified protein was used at 1 mg/mL, and ubiquitin at 0.5 mg/mL. Final concentrations of ATP and MgCl₂ in the assay were 0.1 mM and 0.2 mM, respectively. Reaction mixtures (10 μL total volume) were prepared as follows:

Group 1: 0.1 mM ATP, 0.2 mM MgCl₂, buffer to volume.

Group 2: 0.1 mM ATP, 0.2 mM MgCl₂, 1 μL ubiquitin, buffer to volume.

Group 3: 0.1 mM ATP, 0.2 mM MgCl₂, 6 μL purified protein, buffer to volume.

Group 4: 0.1 mM ATP, 0.2 mM MgCl₂, 6 μL purified protein, 1 μL ubiquitin, buffer to volume.

Reactions were incubated at 22 °C for 10 min, followed by the addition of 10 μL luciferase reagent and a further 10 min incubation at 22 °C. Residual ATP was quantified using a microplate reader (PerkinElmer EnSpire). Each experiment was performed in three independent biological replicates, with each replicate assayed in triplicate. Data were analyzed and plotted using Prism 10. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed paired t-test; results are presented as mean ± SD, with **p < 0.005 (n = 3 independent kinase activity experiments).

Western blotting

Samples in SDS sample buffer were separated by SDS–PAGE (GenScript) and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h, then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in TBS-T. The primary antibody used was anti-PINK1 (Cell Signaling Technology, #6946), diluted 1:1000. Membranes were washed three times with TBS-T, incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, A0545, diluted 1:5000) for 1 h, and washed again three times with TBS-T. Protein signals were visualized using ECL substrate (Thermo Scientific, #34075) and detected with a ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and EM density maps of Hsp90-Cdc37-PINK1 (PDB: 9KQN, EMD-62508, EMD-63402, EMD-63504), Hsp90-FKBP51-PINK1 (PDB: 9KOX, EMD-62482, EMD-64388), Hsp90-PINK1 (PDB: 9KMR, EMD-62442) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/). Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Hartl, F. U., Bracher, A. & Hayer-Hartl, M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332 (2011).

Taipale, M., Jarosz, D. F. & Lindquist, S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 515–528 (2010).

Taipale, M. et al. Quantitative analysis of HSP90-client interactions reveals principles of substrate recognition. Cell 150, 987–1001 (2012).

Schopf, F. H., Biebl, M. M. & Buchner, J. The HSP90 chaperone machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 345–360 (2017).

Xu, W. et al. Sensitivity of mature Erbb2 to geldanamycin is conferred by its kinase domain and is mediated by the chaperone protein Hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3702–3708 (2001).

Echeverria, P. et al. Molecular chaperones, essential partners of steroid hormone receptors for activity and mobility. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1803, 461–469 (2010).

Hoter, A., El-Sabban, M. E. & Naim, H. Y. The HSP90 family: structure, regulation, function, and implications in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19092560 (2018).

Picard, M. M.aD. Cdc37 goes beyond Hsp90 and kinase. Cell Stress Chaperones 08, 114–119 (2003).

Chen, S. & Smith, D. F. Hop as an adaptor in the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and hsp90 chaperone machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 35194–35200 (1998).

Lang, B. J. et al. The functions and regulation of heat shock proteins; key orchestrators of proteostasis and the heat shock response. Arch. Toxicol. 95, 1943–1970 (2021).

Felts, S. J. & Toft, D. O. p23, a simple protein with complex activities. Cell Stress Chaperones 8, 108–113 (2003).

Davies, T. H., Ning, Y.-M. & Sánchez, E. R. A new first step in activation of steroid receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4597–4600 (2002).

Pearl, L. H. & Prodromou, C. Structure and mechanism of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machinery. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 271–294 (2006).

Mark Roe, S. et al. The mechanism of Hsp90 regulation by the protein kinase-specific cochaperone p50(cdc37). Cell 116, 87–98 (2004).

Hunter, T. & Poon, R. Y. Cdc37: a protein kinase chaperone?. Trends Cell Biol. 7, 157–161 (1997).

Richter, K. & Buchner, J. Hsp90: chaperoning signal transduction. J. Cell Physiol. 188, 281–290 (2001).

Verba, K. limentA. et al. Atomic structure of Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk4 reveals that Hsp90 traps and stabilizes an unfolded kinase. SCIENCE 352, 1542–1547 (2016).

Garcja-Alonso, S. et al. Structure of the RAF1-HSP90-CDC37 complex reveals the basis of RAF1 regulation. Mol. Cell 82, 3438–3452 (2022).

Oberoi, J. et al. HSP90-CDC37-PP5 forms a structural platform for kinase dephosphorylation. Nat. Commun. 13, 7343 (2022).

Jaime-Garza, M. et al. Hsp90 provides a platform for kinase dephosphorylation by PP5. Nat. Commun. 14, 2197 (2023).

Caveney, N. A., Tsutsumi, N. & Garcia, K. C. Structural insight into guanylyl cyclase receptor hijacking of the kinase–Hsp90 regulatory mechanism. ELife 12, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.86784 (2023).

Wang, R. Y.-R. et al. Structure of Hsp90–Hsp70–Hop–GR reveals the Hsp90 client-loading mechanism. Nature 601, 460–464 (2021).

Noddings, C. M., Wang, R. Y.-R., Johnson, J. L. & Agard, D. A. Structure of Hsp90–p23–GR reveals the Hsp90 client-remodelling mechanism. Nature 601, 465–469 (2021).

Lee, K. et al. The structure of an Hsp90-immunophilin complex reveals cochaperone recognition of the client maturation state. Mol. Cell 81, 3496–3508.e3495 (2021).

Noddings, C. M., Johnson, J. L. & Agard, D. A. Cryo-EM reveals how Hsp90 and FKBP immunophilins co-regulate the glucocorticoid receptor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 1867–1877 (2023).

Baischew, A., Engel, S., Geiger, T. M., Taubert, M. C. & Hausch, F. Structural and biochemical insights into FKBP51 as a Hsp90 co-chaperone. J. Cell Biochem. 125, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.30384 (2023).

Hähle, A., Merz, S., Meyners, C. & Hausch, F. The many faces of FKBP51. Biomolecules 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9010035 (2019).

Ruiz-Estevez, M. et al. Promotion of myoblast differentiation by Fkbp5 via Cdk4 isomerization. Cell Rep. 25, 2537–2551 (2018).

Weihofen, A., Ostaszewski, B., Minami, Y. & Selkoe, D. J. Pink1 Parkinson mutations, the Cdc37/Hsp90 chaperones and Parkin all influence the maturation or subcellular distribution of Pink1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 602–616 (2008).

Valente, E. M. et al. PINK1 mutations are associated with sporadic early-onset parkinsonism. Ann. Neurol. 56, 336–341 (2004).

Woodroof, H. I. et al. Discovery of catalytically active orthologues of the Parkinson's disease kinase PINK1: analysis of substrate specificity and impact of mutations. Open Biol. 1, 110012 (2011).

Schubert, A. F. et al. Structure of PINK1 in complex with its substrate ubiquitin. Nature 552, 51–56 (2017).

Gan, Z. Y. et al. Activation mechanism of PINK1. Nature 602, 328–335 (2021).

Bayne, A. N. & Trempe, J. F. Mechanisms of PINK1, ubiquitin and Parkin interactions in mitochondrial quality control and beyond. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 76, 4589–4611 (2019).

Narendra, D. P. et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000298 (2010).

Okatsu, K. et al. PINK1 autophosphorylation upon membrane potential dissipation is essential for Parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria. Nat. Commun. 3, 1016 (2012).

Okatsu, K. et al. A dimeric PINK1-containing complex on depolarized mitochondria stimulates Parkin recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36372–36384 (2013).

Kondapalli, C. et al. PINK1 is activated by mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization and stimulates Parkin E3 ligase activity by phosphorylating Serine 65. Open Biol. 2, 120080 (2012).

Koyano, F. et al. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature 510, 162–166 (2014).

Kane, L. A. et al. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Cell Biol. 205, 143–153 (2014).

Lazarou, M. et al. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature 524, 309–314 (2015).

Soman, S. K. & Dagda, R. K. Role of cleaved PINK1 in neuronal development, synaptogenesis, and plasticity: implications for Parkinson's disease. Front. Neurosci. 15, 769331 (2021).

Meissner, C., Lorenz, H., Weihofen, A., Selkoe, D. J. & Lemberg, M. K. The mitochondrial intramembrane protease PARL cleaves human Pink1 to regulate Pink1 trafficking. J. Neurochem. 117, 856–867 (2011).

Greene, A. W. et al. Mitochondrial processing peptidase regulates PINK1 processing, import and Parkin recruitment. EMBO Rep. 13, 378–385 (2012).

Lin, W. & Kang, U. J. Characterization of PINK1 processing, stability, and subcellular localization. J. Neurochem. 106, 464–474 (2008).

Yamano, K. & Youle, R. J. PINK1 is degraded through the N-end rule pathway. Autophagy 9, 1758–1769 (2014).

Emdadul Haque, M. et al. Cytoplasmic pink1 activity protects neurons from dopaminergic neurotoxin MPTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1716–1721 (2008).

Moriwaki, Y. et al. L347P PINK1 mutant that fails to bind to Hsp90/Cdc37 chaperones is rapidly degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner. Neurosci. Res. 61, 43–48 (2008).

Murata, H. et al. A new cytosolic pathway from a Parkinson disease-associated kinase, BRPK/PINK1: activation of AKT via mTORC2. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7182–7189 (2011).

Dagda, R. K. et al. Beyond the mitochondrion: cytosolic PINK1 remodels dendrites through protein kinase A. J. Neurochem. 128, 864–877 (2014).

Rasool, S. et al. Mechanism of PINK1 activation by autophosphorylation and insights into assembly on the TOM complex. Mol. Cell 82, 44–59 (2022).

Kakade, P. et al. Mapping of a N-terminal alpha-helix domain required for human PINK1 stabilization, Serine228 autophosphorylation and activation in cells. Open Biol. 12, 210264 (2022).

Lin, W. & Kang, U. J. Structural determinants of PINK1 topology and dual subcellular distribution. BMC Cell Biol. 11, 90 (2010).

Verba, K. A. et al. Atomic structure of Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk4 reveals that Hsp90 traps and stabilizes an unfolded kinase. Science 352, 1542–1547 (2016).

Riggs, D. L. et al. The Hsp90-binding peptidylprolyl isomerase FKBP52 potentiates glucocorticoid signaling in vivo. EMBO J. 22, 1158–1167 (2003).

Oroz, J. et al. Structure and pro-toxic mechanism of the human Hsp90/PPIase/Tau complex. Nat. Commun. 9, 4532 (2018).

Shiau, A. K., Harris, S. F., Southworth, D. R. & Agard, D. A. Structural Analysis of E. coli hsp90 reveals dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements. Cell 127, 329–340 (2006).

Prodromou, C. & Bjorklund, D. M. Advances towards understanding the mechanism of action of the Hsp90 complex. Biomolecules 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12050600 (2022).

Elnatan, D. et al. Symmetry broken and rebroken during the ATP hydrolysis cycle of the mitochondrial Hsp90 TRAP1. ELife 6, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25235 (2017).

Graf, C., Stankiewicz, M., Kramer, G. & Mayer, M. P. Spatially and kinetically resolved changes in the conformational dynamics of the Hsp90 chaperone machine. EMBO J. 28, 602–613 (2009).

Hessling, M., Richter, K. & Buchner, J. Dissection of the ATP-induced conformational cycle of the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 287–293 (2009).

Prodromou, C. The ‘active life’ of Hsp90 complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 614–623 (2012).

Krukenberg, K. A., Forster, F., Rice, L. M., Sali, A. & Agard, D. A. Multiple conformations of E. coli Hsp90 in solution: insights into the conformational dynamics of Hsp90. Structure 16, 755–765 (2008).

Southworth, D. R. & Agard, D. A. Species-dependent ensembles of conserved conformational states define the Hsp90 chaperone ATPase cycle. Mol. Cell 32, 631–640 (2008).

Dollins, D. E., Warren, J. J., Immormino, R. M. & Gewirth, D. T. Structures of GRP94- nucleotide complexes reveal mechanistic differences between the hsp90 chaperones. Mol. Cell 28, 41–56 (2007).

Callegari, S. et al. Structure of human PINK1 at a mitochondrial TOM-VDAC array. Science 388, 303–310 (2025).

Keramisanou, D., Vasantha Kumar, M. V., Boose, N., Abzalimov, R. R. & Gelis, I. Assembly mechanism of early Hsp90-Cdc37-kinase complexes. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm9294 (2022).

Prodromou, C. Mechanisms of Hsp90 regulation. Biochem. J. 473, 2439–2452 (2016).

Pearl, L. H. Review: The HSP90 molecular chaperone-an enigmatic ATPase. Biopolymers 105, 594–607 (2016).

Valente, E. M. et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 304, 1158–1160 (2004).

Ibanez, P. et al. Mutational analysis of the PINK1 gene in early-onset parkinsonism in Europe and North Africa. Brain 129, 686–694 (2006).

Dagda, R. K. et al. Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13843–13855 (2009).

Fedorowicz, M. A. et al. Cytosolic cleaved PINK1 represses Parkin translocation to mitochondria and mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 15, 86–93 (2014).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera-A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the staff at the Cryo-EM Center of Tsinghua University for their outstanding technical support, and to Prof. Chen Guo (Nankai University) for providing the original PINK1-full length plasmid. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92354303 to K.M., 92254306 to S.S., 32241030 to S.-F.S., and 91954112 and 31900501 to K.M.) and the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by Tianjin (TJSQNTJ-2020-19 to K.M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-F.S. and K.M. supervised the project. X.T. and J.S. designed the experiments. X.T., J.S., and Z.W. purified the proteins, prepared the cryo-EM samples. J.S., T.L., and H.X. collected the cryo-EM data. X.T. and K.M. built the atomic model. X.T., J.S., and S.S. analyzed the structure. X.T., J.S., and K.M. wrote the initial draft. S.S. and S.-F.S. edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, X., Su, J., Wang, Z. et al. Molecular mechanism of PINK1 regulation by the Hsp90 machinery. Nat Commun 16, 10801 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65859-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65859-w