Abstract

Unprotected β-fluoroamines are important motifs in synthetic chemistry, offering versatility for the development of β-fluorinated nitrogen-containing compounds. Existing methods to these motifs require tedious operations and suffer from low efficiencies, which has prevented their use in biologically active molecules, such as drug discovery and positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer development. Herein, an iron-catalyzed three-component aminofluorination of alkenes using a hydroxylamine reagent and Et3N · 3HF is reported, offering a direct entry to unprotected β-fluoroamines. Both aryl and unactivated alkenes are compatible, and the mild conditions along with a short reaction time enable its application in alkene aminoradiofluorination. The synthetic utility of this methodology is demonstrated by diverse follow-up derivatizations, efficient access to drug candidate LY503430, and the radiosynthesis of [18F]KP23, a cannabinoid subtype 2 (CB2) PET radioligand. Mechanistic investigations reveal a radical pathway involving ferryl amino and aziridinium intermediates, and highlight the dual roles of Et3N · 3HF as both fluorine source and reductive promotor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction of β-fluoroamine motifs has attracted significant attention from organic chemists over the past few decades due to their prevalence in biologically relevant molecules, such as MK-0731 as a kinesin spindle protein (KSP) inhibitor1, cytidine nucleoside PSI-6130 as an inhibitor of hepatitis C virus (HCV)2, KP23 as a cannabinoid subtype 2 (CB2) receptor ligand3, and other examples4,5,6. The incorporation of a fluorine atom into drug molecules is well known to modulate physicochemical properties, such as lipophilicity, permeability, pharmacokinetics, and metabolic stability, while also alter their structural conformation7,8,9,10,11. Moreover, the fluorine atom has been shown to attenuate the basicity of adjacent amine nitrogen atom to further improve the performance of pharmaceutical agents (Fig. 1a)12,13. Taking account of the versatility of aliphatic primary amines in downstream transformations to diverse secondary and tertiary amines/amides, as well as aza-heterocycles, the synthesis of unprotected β-fluoroamines is of particular interest to organic chemists14, but also proves to be challenging since the −NH2 products can strongly chelate metal catalysts and thus inhibit catalytic cycles15. Current synthetic methods for the synthesis of unprotected β-fluoroamines predominantly rely on sluggish nucleophilic ring-opening of aziridines16,17, reduction of α-cyano/amido or β-azido fluorides18,19,20,21, and deprotection of β-fluoro amines/amides22,23,24,25. However, these approaches require specially engineered precursors and suffer from low overall efficiencies.

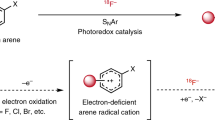

The intermolecular aminofluorination of alkenes offers a streamlined access to β-fluoroamines by simultaneously introducing N and F atoms across abundant feedstocks (Fig. 1b)26,27,28. Considerable progress with electronically deficient amino sources has been achieved by Stavber29, Liu30, Nevado31, Zhang32, Studer33, and among others34,35,36,37,38. These studies employed (in situ formed) electrophilic fluorinating reagents, while Pérez39 and P. Xu40 used nucleophilic fluorides, facilitating the synthesis of vicinal fluoroamides. A combination of electrophilic XtalFluor-E and Et3N·3HF was utilized by H. Xu41 to attenuate the concentration of fluoride ion, leading to the production of carbamate-protected β-fluoroamines. But the chemical reactivities of these reactions are significantly affected by the electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) attached to nitrogen atoms, which limits product diversity. Recently, Fu42 and Wang43 independently reported the alkene aminofluorination using electrophilic amination reagents as electron-rich amino sources to forge β-fluorinated tertiary alkylamines. Unfortunately, the one-step installation of a simple NH2 group along with a fluorine atom across olefins remains unknown, but is highly desirable due to the potential for diverse derivatizations to access various β-fluorinated nitrogen-containing compounds. Additionally, because of the harsh conditions or long reaction times required, the incorporation of the radionuclide 18F with a short half-life (t1/2 = 109.8 min) and limited availability of sources in alkene aminofluorination has not yet been achieved, significantly impeding the development of corresponding positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers that are applied for medical imaging44,45,46,47,48.

O-protected hydroxylamines have recently emerged as key precursors for NH2-involved alkene difunctionalization49, allowing the sequential introduction of various functionalities (O–, Cl–, N–, Ar–) to generate β-functionalized unprotected amines50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63. The major obstacle for incorporating a fluorine atom lies in the acidic media, which would likely promote the formation of highly electrophilic NH2 species to facilitate alkene addition, prevent undesired rearrangement of hydroxylamine reagents to more stable N-hydroxy amides64, and protonate the NH2 unit in the product to avoid undesired chelation of the metal catalyst15. However, acidic conditions can also diminish the nucleophilicity of solvated fluoride ions through hydrogen bonding65,66, and may induce competing side reactions, such as alkene protonation. Furthermore, to avoid the negative impact of a third nucleophile on aziridinium formation, one-pot/two-step procedures are often employed, as demonstrated by Lebœuf/Moran59,60 and Ellman61 in alkene aminoarylation and diamination, as well as Bower62 in aminative cyclization. The highly electronegative fluoride can coordinate with transition metal complex to induce catalyst deactivation, such as iron catalyst41, thus potentially interfering with direct radical amination processes. Considering these challenges along with its own peculiarities, the introduction of radionuclide 18F into such reactions poses even greater technical difficulties.

Herein, we report a one-step synthesis of unprotected β-fluoroamines from simple alkenes through a three-component aminofluorination using a hydroxylamine reagent and Et3N·3HF (Fig. 1c). Phthalocyanine-coordinated iron catalyst was employed to prevent the coordination of fluoride, thus avoiding catalyst deactivation. The use of Et3N·3HF is crucial, serving both as a nucleophilic fluorine source compatible with acidic media and as a reductant that facilitated the regeneration of active ferrous species from μ-oxo diiron(III) complex to accelerate the aminofluorination reaction. This acceleration can suppress competing side reactions and lead to a very short reaction time, which, when paired with mild and air-insensitive reaction conditions, ultimately enables alkene aminoradiofluorination under the action of [18F]TMAF·HFIP, Et2N·HCl, and Et3N. The great synthetic potential of this methodology is fully demonstrated by broad substrate scope accommodating both aryl and unactivated alkenes, excellent functional-group tolerance, as well as diverse synthesis of β-fluorinated nitrogen-containing compounds, including the efficient synthesis of an AMPA receptor positive allosteric modulator LY503430, and unique PET radiotracer [18F]KP23 that targets the cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptor.

Results

Screening of reaction conditions

Our optimization investigations were initiated by combining 4-vinylbiphenyl 1a with commercially available iron phthalocyanine (FePc; 0.1 equivalents) and hydroxylamine reagent AcONH3OTf (I; 2.5 equivalents) in acetonitrile at 40 °C under an argon atmosphere (Table 1). The choice of fluorine source played a pivotal role in the success of this reaction (entries 1–4). Substrate 1a remained inert in the presence of basic tetramethylammonium fluoride (TMAF), while H+-induced alkene decomposition and a small amount of aziridine were observed with either AgF or HF·Py, indicating a necessity of fast aminofluorination process. Delightedly, when Et3N·3HF was employed, the desired aminofluorination reaction to β-fluoroamine 2a occurred, albeit with a low yield of 23% (Note: although the unprotected β-fluoroamine product is stable and separable, to facilitate the purification of this polar compound, a simple subsequent Boc-protection was conducted). Replacement of FePc with other types of iron salts, such as Fe(OTf)2, FeSO4, and Fe(acac)2, resulted in complete suppression of the reaction probably due to fluoride-induced catalyst deactivation (entries 5–7)41. While external ligands have been shown to improve the catalytic activity of iron catalysts52, a combination of FeSO4 with 2,2′-bipyridine or 2,2′:6′,2”-terpyridine failed in this reaction (entries 8 and 9). Further screening of reaction solvents revealed that THF gave a very low yield of only 5%, while the use of highly polar and nonnucleophilic hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) completely disrupted the reaction (entries 10 and 11). In contrast, reactions conducted in DCM or CHCl3 provided significantly improved yields of 54% and 50%, respectively (entries 12 and 13). Optimizing the reaction temperature resulted in a modestly enhanced yield of 60% at 30 °C, and increasing the amount of Et3N·3HF from 4.0 to 8.0 equivalents showed minimal impact on the reaction outcome (entries 14–17). Subsequently, several bench-stable hydroxylamine reagents were screened (entry 18)67. The reactions with PivONH3OTf II68,69 and TsONH3OTf III70 yielded results comparable to that obtained with I, whereas only trace amounts of the desired product were observed with commodity chemical HONH3Cl IV71. Notably, the use of 4-NO2-BzONH3OTf V72 afforded 2a in 73% yield. The reaction could be conducted open to air with only a slight reduction in yield to 71%, demonstrating its operational simplicity (entry 19, adopted as the standard reaction conditions). Extending the reaction time to 3 h did not further improve the yield, and a control experiment excluding the iron atom proved ineffective (entries 20 and 21).

Substrate scope and derivatization

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we next investigated the substrate scope. As shown in Fig. 2, both styrene and its derivatives bearing either electronically neutral (–Me, –iPr, –tBu) or donating (–OMe, –OPh, –OBz) substituents were efficiently converted to products 2b–2j in good yields. It is worth noting that the reaction time for 2h was shortened to 15 min as prolonged stirring time led to gradual product decomposition, likely due to the instability of the electron-rich benzylic C–F bond under acidic conditions. Among substrates containing EWGs, F–, Cl–, Br–, and MeO2C–substituted styrenes produced 2k–2q in good to moderate yields, while only trace amounts of product 2r were detected with the strongly electron-deficient –CF3 group likely due to slow electrophilic addition. Moreover, both di- and sterically encumbered tri-substituted styrenes were well tolerated to furnish β-fluoroamines 2s–2w. This reaction showed an excellent functional group tolerance towards chlorine atoms, azido groups, esters, C–C triple/double bonds, and even unprotected hydroxyl groups (2x–2ac), providing valuable synthetic handles for further manipulations. The 1,1-disubstituted alkenes were also found to be suitable reaction partners, and the corresponding products 2ad–2af bearing tertiary carbon–fluorine stereocentres were obtained. Additionally, the aminofluorination reaction was extended to internal alkenes. In the case of cyclic internal alkene (2ag), an unusual cis-isomer dominated the product distribution (cis:trans = 7:1), while for acyclic internal alkene, a complete lack of stereoretention (2ah, a mixture containing two diastereomeric pairs in a ratio of 1:1) was observed. These results indicate a stepwise mechanism (for a detailed discussion, see Part 2 of Supplementary Information). Other arylalkenes, such as 2-vinylnaphthalene and 2-vinylbenzo[b]thiophene, were smoothly converted into the corresponding vicinal fluoroamines 2ai and 2aj. Importantly, this protocol was not limited to arylalkenes; unactivated alkenes were also successfully employed to deliver 2ak–2ao in moderate yields with partial recovery of the starting materials. However, the reaction of mono-substituted unactivated alkene, e.g., 1-octene, failed probably due to the slow addition of N-centered radical to olefin π system that led to the decomposition of highly active radical species, and about 80% alkene substrate was recovered. To showcase the synthetic potential of this methodology in late-stage functionalization of biologically relevant molecules, the alkenes derived from natural products and pharmaceuticals, including estradiol (2ap), lithocholic acid (2aq), oxaprozin (2ar), ibuprofen (2as), diacetone-D-galactose (2at), phenylalanine (2au), and vanillylacetone (2av) were subjected to the optimized reaction conditions. Notably, these reactions worked well without the need for pre-protection of polar –OH or –NH groups.

Standard conditions: hydroxylamine reagent V (0.75 mmol) was added to a mixture of alkene 1 (0.30 mmol), FePc (0.03 mmol), and Et3N·3HF (1.2 mmol) in DCM (2.0 mL) at 30 °C, and the reaction was stirred open to air for 30 min. The drs were determined according to 1H NMR. a Yield of isolated product after Boc protection. bFor 15 min. cIn DCE at 80 °C. dYields of recovered alkenes given in the brackets.

The utility of this methodology for the assembly of valuable nitrogen-containing molecules is demonstrated in Fig. 3. The reaction of 2a with thiophosgene followed by H–Cl elimination furnished the β-fluorinated isothiocyanate 3. Secondary amines and amides 4–7 were synthesized via reductive alkylation, N–H insertion across an in situ formed benzyne intermediate, copper-catalyzed Ullman coupling, or dehydration condensation. Through nucleophilic substitution reactions of 2a, fluorinated tertiary amines and amides 8–10 were obtained. β-Fluoroamine 2a could also undergo Paal–Knorr reaction, four-component Debus–Radziszewski reaction, or Leuckart–Wallach/intramolecular condensation sequence to deliver various β-fluorinated aza-heterocycles, including pyrrole 11, imidazole 12, and lactam 13. Moreover, following the protection of the primary amine moiety as the corresponding amide, a subsequent Bischler–Napieralski cyclization produced dihydroisoquinoline 14, while an intramolecular C(sp2)–H amidation/defluorination sequence afforded indole 15 (Fig. 3a). By integrating the newly developed alkene aminofluorination with a condensation reaction with thiocarbimidazole 16, an efficient route to fluorothiourea compounds 17 and 18 with potent anti-HIV activity has been established. This streamlined approach significantly simplifies the previous four-step synthetic route (Fig. 3b)73.

The practicability of this reaction then enables a concise synthesis of LY503430 (Fig. 3c), a potential therapeutic agent for Parkinson’s disease74. The preparation of racemic LY503430 by Eli Lilly needs more than 8 steps75, while 14 steps are necessary for enantioselective synthesis76. Our approach commenced with commercially available 4′-acetyl-biphenyl−4-carboxylic acid. Amidification with methylamine followed by Wittig olefination afforded terminal alkene 20. The key alkene aminofluorination step furnished unprotected β-fluoroamine 21 in 68% yield. Final installation of a sulfonyl group onto the NH2 moiety yielded LY503430. This route features both step economy (4 steps) and high efficiency (30% overall yield), and no tedious protection/deprotection sequence is involved.

Mechanistic studies

To gain insight into the underlying reaction mechanism, a series of control experiments were undertaken. The addition of 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) completely suppressed the formation of β-fluoroamine 2a (Fig. 4a). A radical clock experiment using vinylcyclopropane 22 generated ring-opening product 23 in 65% yield (Fig. 4b). These results suggested an involvement of nitrogen-centered radicals. Competition reactions were performed by treating mixed alkenes (1:1) with 1.2 equivalents of hydroxylamine reagent V, and β-fluoroamines 2b and 2g dominated the reaction outcomes, respectively, indicating an electrophilic addition process strongly favoring electron-rich olefin moieties (Fig. 4c, more details in Supplementary Information). The addition of methanol led to both the aminofluorination (2a) and aminooxygenation (24) products, with the latter likely arising from the nucleophilic ring-opening of a putative aziridinium intermediate by methanol (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, the formation of aziridinium intermediate was directly confirmed by ESI-MS analysis after conducting the reaction for just 3 min (Fig. 4e). Additionally, the use of either E- or Z-β-methyl styrene 1ah consistently produced β-fluoroamine 2ah as a mixture containing two diastereomeric pairs in an approximately 1:1 ratio. The complete loss of stereoinformation is indicative of a stepwise mechanism involving a long-lived carbon-centered radical or carbocation intermediate (Fig. 4f)77. In addition to serving as a nucleophilic fluorine source, Et3N·3HF was found to play a special role (Fig. 4g). The addition of 2.0 equivalents of Et3N reinitiated the aminofluorination reaction with HF·Py, offering 2a in 25% yield; but further increasing the amount to 10 equivalents invalidated the reaction, likely due to a significant alteration in the acidity of reaction media. Moreover, after mixing Et3N·3HF with commercially available FePc for 30 min, Et2NH was detected by ESI-MS analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings indicated that Et3N·3HF might function as a reductant to accelerate the aminofluorination reaction.

To further elucidate the reaction mechanism, particularly the role of Et3N·3HF, density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been performed. The previously proposed facile oxidation of FePc to the μ-oxo diiron complex ((FePc)2O) in the presence of air is confirmed to be thermodynamically favorable (Fig. 5a)78. This oxidation process has also been supported by ESI-MS, which detects the (FePc)2O complex (see Supplementary Fig. 3). That means the commercially available FePc would be easily oxidized in part before manipulation. Additionally, the decomposition of (FePc)2O into PcFe–OH and PcFe–F species, mediated by HF (with Et3N·3HF simplified as Et3N·HF)79, is calculated to be exergonic (see Supplementary Fig. 5) and further validated by ESI-MS analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 4). However, these ferric iron species ((FePc)2O, PcFe–OH, and PcFe–F) are found to be inactive toward the hydroxylamine reagent V due to the high activation barriers (>35.0 kcal/mol) for N–O bond cleavage (Fig. 5b)80. In contrast, computational studies reveal that the ferrous FePc complex shows significantly higher reactivity, with a low activation barrier of 16.3 kcal/mol for hydroxylamine activation (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, it is proposed that Et3N acts as a reductant to convert these unreactive ferric iron species (PcFe–OH and PcFe–F) into the catalytically active ferrous in situ (Fig. 5c). Specifically, PcFe–F is reduced to FePc by abstracting α-hydrogen atom of Et3N, accompanied with the formation of HF and α-amino carbon-centered radical (INT1). Subsequent radical rebound with PcFe–OH affords hemiaminal INT2 and FePc81. Notably, alternative direct single-electron transfer from Et3N to either PcFe–F or PcFe–OH is calculated to be highly endothermic (see Supplementary Fig. 7). With the assistant of HF, INT2 readily decomposes to acetaldehyde and Et2NH, the latter of which has been detected by ESI-MS (see Fig. 4g). The overall process is both kinetically feasible (ΔG≠ = 26.4 kcal/mol) and thermodynamically favorable (ΔG = −40.3 kcal/mol). These results clearly demonstrate that Et3N·3HF can significantly facilitate the reductive regeneration of the active ferrous catalyst, thus effectively minimizing side reactions and accelerating the aminofluorination reaction.

a Thermodynamic data for the formation and decomposition of diiron complex. b Activation of hydroxylamine reagent by different iron species. c Free energy profile for the reduction of FeIII to FeII by Et3N. d Free energy profile for the iron-catalyzed aminofluorination of alkenes, including 3D structures for the key transition states. Energies and distances are presented in kcal/mol and angstroms (Å), respectively.

On the basis of our previous studies82, a plausible reaction pathway is proposed in Fig. 5d. After the activation of the hydroxylamine (TS3), the in situ formed iron-amido intermediate (INT3) first experiences an electronic reconfiguration to form a ferryl amino intermediate (INT4), which, though less stable, is more electrophilic and somewhat distinct from typical iron-nitrenoid species41,52,54,83,84,85,86. This ferryl species subsequently engages in a reaction with styrene via TS4 (ΔG≠ = 10.2 kcal/mol), where it receives an electron from the alkene and reduces itself to a ferric species. The resulting benzylic radical intermediate (INT5) then easily undergoes cyclization to form a stable aziridinium intermediate (INT6) with a calculated activation barrier of ΔG≠ = 14.1 kcal/mol. Nucleophilic addition of Et3N·3HF to INT6 via TS6 (ΔG≠ = 17.5 kcal/mol) finally affords aminofluorination product P. Notably, the anti-addition of Et3N·3HF for linear alkenes, while syn-addition for cyclic internal alkene (consistent with 2ag in Fig. 2) have been calculated to be favorable (see Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, these steps are downhill processes and kinetically feasible with activation barriers less than 17.5 kcal/mol.

Radiochemistry

Having successfully demonstrated the utility of the cold aminofluorination method, a modified synthetic protocol was developed for the direct aminoradiofluorination of alkenes to afford unprotected β-radiofluoroamines. Fluorine-18 is typically produced by bombarding 18O (oxygen-18) enriched water with protons in a cyclotron using the 18O(p,n)18F reaction, where the amount of 18F− generated from a cyclotron is in the sub-nanomole range. This makes 18F− the limiting reagent in radiochemical reactions87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94. Consequently, reagents containing multiple labile fluorine atoms, such as Et3N·3HF, should be avoided to prevent isotopic dilution. After screening alternate conditions using 4-vinylbiphenyl 1a as a model substrate (for a detailed discussion, see Supplementary Table 2), the combination of HFIP95,96,97 as a hydrogen bonding agent that mediates fluoride nucleophilicity and provides a source of labile protons, TMAF as the fluoride ion source, Et2NH·HCl as reaction additive, and Et3N as the reductant was found to be a suitable alternative to Et3N·3HF. Under the re-optimized cold reaction conditions, 1a was successfully converted to 2a and isolated as its Boc-protected derivative in 25% yield.

Manual radiochemical reaction optimization based on model substrate 1a was then carried out (Supplementary Table 3). Comparable radiochemical conversions (RCCs) were observed at 0.05 and 0.025 mmol reaction scales, with the latter scale preferable for routine radiotracer production on automated radiosynthesis platforms. The reaction with 1.0 equivalent of Et2NH·HCl resulted in a RCC of 10%. Reducing the loading to 0.5 or 0.25 equivalents improved the RCCs to 16% and 15%, respectively. Adjusting the reaction volume from 0.3 to 0.5 mL made little effect on the RCC, so 0.4 mL was chosen for its enhanced solubility compared to 0.3 mL at the 0.025 mmol scale. Under optimized conditions (0.025 mmol 1a, 0.1 equiv FePc, 2.5 equiv V, 0.25–0.5 equiv Et2NH·HCl, 0.2 equiv Et3N, 0.4 mL 8:1 DCM: HFIP with 3–10 mCi [18F]TMAF·HFIP), the desired β-radiofluoroamine [18F]2a was obtained with a RCC of 16%. Using this method, β-radiofluoroamine [18F]2a was synthesized and isolated using analytical HPLC with a decay-corrected radiochemical yield (RCY)98 of 2% and molar activity of 42.13 GBq/nmol.

A comparable substrate scope to the cold aminofluorination protocol was explored under the optimized radiofluorination conditions. For the purposes of evaluating substrate scope, crude reaction mixtures were analyzed and their relative RCCs are discussed. All the alkene substrates were successfully labeled with moderate RCCs ranging from 5 to 16%, including those adjacent to electronically deficient, neutral, or electron-rich aromatic ring systems with a diverse array of functional groups. Di- or tri-substituted arylalkenes, as well as fused aromatic ring systems, were also well-tolerated. Complex alkene substrates derived from natural products and pharmaceuticals, such as oxaprozin and ibuprofen were able to be labeled, showcasing the viability of this method for late-stage 18F-incorporation into drug molecules. As proof-of-concept for the (pre)clinical relevance of this method, the manual radiosynthesis of [18F]KP23 was achieved (Fig. 6). Previous attempts to prepare [18F]KP23 through nucleophilic substitution of its chloro-precursor with [18F]KF/K222/K2CO3 in DMF, DMSO, or CH3CN were unsuccessful99. This is attributed to the poor leaving group ability of the chloride in 25. Although attempts were made to prepare tosyl- and mesyl- derivatives, these intermediates did not afford the desired KP23 due to the spontaneous displacement of the superior leaving groups by nitrogen to afford an aziridinium ion pair. This ion pair then immediately collapses in the presence of chloride-ion to reform a stable chloride derivative. In contrast, the present protocol converted commercially available styrene (1b) to [18F]β-fluoroamine 2b and subsequently coupled it with acyl chloride (12) in a one-pot, two-step reaction without the need for intermediate purification of [18F]β-fluoroamine (2b), affording [18F]KP23 with a RCC of 11%. [18F]KP23 was purified through analytical HPLC with molar activity of 1.68 GBq/nmol.

Standard radiofluorination reaction conditions involved the addition of [18F]TMAF·HFIP and Et3N (0.2 equiv.) in an 8:1 DCM: HFIP solution (0.4 mL) to a solid mixture containing alkene (0.025 mmol), hydroxylamine reagent V (2.5 equiv.), FePc (0.1 equiv.), and Et2NH·HCl (0.25–0.5 equiv.) at 30 °C. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min. Amine products were characterized and quantified as their Boc-protected derivatives by radio-TLC and/or analytic radio-HPLC. Radiochemical conversions (RCCs) determined for crude reaction mixtures are shown. A decay-corrected (d.c.) radiochemical yield (RCY) is provided for substrate [18F]2a.

Discussion

An iron-catalyzed three-component aminofluorination of alkenes with a hydroxylamine reagent and Et3N·3HF has been developed under mild reaction conditions, providing a straightforward access to unprotected β-fluoroamines from readily available feedstocks. This methodology shows a broad substrate scope, ease of operation in air, and excellent functional group tolerance, making it a practical protocol for late-stage functionalization of biologically relevant molecules. The versatility of the resulting primary amine moiety further enables the creation of structurally diverse vicinal fluorinated nitrogen-containing derivatives, including a step-economic and efficient synthesis of pharmaceutical LY503430. Detailed mechanistic investigations reveal a radical reaction pathway involving aziridinium intermediates, with Et3N·3HF functioning as both a suitable nucleophilic fluorine source and a reductant that regenerates active ferrous species from μ-oxo diiron(III) complex to significantly accelerate the aminofluorination reaction. Furthermore, the dual roles of Et3N·3HF can be substituted with a combination of [18F]TMAF·HFIP, Et2N·HCl, and Et3N, facilitating the adaptation of this methodology to radiochemistry for the direct aminoradiofluorination of a diverse range of alkene substrates. This radiochemical transformation has been employed in the radiosynthesis of fluorine-18 labeled KP23, a PET radioligand for the CB2 receptor for which no other successful synthesis had been reported. This aminofluorination approach is poised to serve as a robust framework for both drug development and advancement of PET imaging probe, offering significant potential for applications in the drug discovery and radiochemistry communities.

Methods

Standard reaction conditions

Hydroxylamine reagent 4-NO2-BzONH3OTf V (249 mg, 0.75 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) was added to a plastic centrifuge tube charged with alkene 1a (54.1 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), FePc (17.0 mg, 0.03 mmol, 0.1 equiv.), Et3N·3HF (196 μL, 1.2 mmol, 4.0 equiv.), and CH2Cl2 (2.0 mL). The mixture was stirred open to air at 30 °C (oil bath) for 30 min. Upon completion, the reaction was quenched with Et3N (0.5 mL) at 0 °C. Direct purification by flash column chromatography (DCM/MeOH = 20:1 as eluent) afforded β-fluoroamine 2a as a yellow oil (47.1 mg, 0.22 mmol, 73%).

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Cartesian coordinates of the calculated structures are available from the Supplementary Data 1. Any further relevant data are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Cox, C. D. et al. Kinesin spindle protein (KSP) inhibitors. 9. Discovery of (2S)-4-(2,5-difluorophenyl)-N-[(3R,4S)−3-fluoro-1-methylpiperidin-4-yl]−2-(hydroxymethyl)-N-methyl-2-phenyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrole-1-carboxamide (MK-0731) for the treatment of taxane-refractory cancer. J. Med. Chem. 51, 4239–4252 (2008).

Clark, J. L. et al. Design, synthesis and antiviral activity of 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine, a potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication. J. Med. Chem. 48, 5504–5508 (2005).

Turkman, N. et al. Fluorinated cannabinoid CB2 receptor ligands: synthesis and in vitro binding characteristics of 2-oxoquinoline derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19, 5698–5707 (2011).

Morwick, T. Pim kinase inhibitors: a survey of the patent literature. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 20, 193–212 (2010).

van Niel, M. B. et al. Fluorination of 3-(3-(piperidin-1-yl)propyl)indoles and 3-(3-(piperazin-1-yl)propyl)indoles gives selective human 5-HT1D receptor ligands with improved pharmacokinetic profiles. J. Med. Chem. 42, 2087–2104 (1999).

Asahina, Y., Takei, M., Kimura, T. & Fukuda, Y. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of novel pyrido[1,2,3-de][1,4]benzoxazine-6-carboxylic acid derivatives carrying the 3-cyclopropylaminomethyl-4-substituted-1-pyrrolidinyl group as a C-10 substituent. J. Med. Chem. 51, 3238–3249 (2008).

Müller, K., Faeh, C. & Diederich, F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886 (2007).

O’Hagan, D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. An introduction to the C−F bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 308–319 (2008).

Purser, S., Moore, P. R., Swallow, S. & Gouverneur, V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 320–330 (2008).

Hagmann, W. K. The many roles for fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 51, 4359–4369 (2008).

Liang, T., Neumann, C. N. & Ritter, T. Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8214–8264 (2013).

Morgenthaler, M. et al. Predicting and tuning physicochemical properties in lead optimization: amine basicities. ChemMedChem 2, 1100–1115 (2007).

Gillis, E. P., Eastman, K. J., Hill, M. D., Donnelly, D. J. & Meanwell, N. A. Applications of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 58, 8315–8359 (2015).

Legnani, L., Bhawal, B. N. & Morandi, B. Recent developments in the direct synthesis of unprotected primary amines. Synthesis 49, 776–789 (2017).

Hartwig, J. F. Organotransition metal chemistry: From bonding to Catalysis (University Science Books, 2010).

Wade, T. N. Preparation of fluoro amines by the reaction of aziridines with hydrogen fluoride in pyridine solution. J. Org. Chem. 45, 5328–5333 (1980).

Alvernhe, G. M., Ennakoua, C. M., Lacombe, S. M. & Laurent, A. J. Ring opening of aziridines by different fluorinating reagents: three synthetic routes to α,β-fluoro amines with different stereochemical pathways. J. Org. Chem. 46, 4938–4948 (1981).

Papanastassiou, Z. B. & Bruni, R. J. Potential carcinolytic agents. II. Fluoroethylamines by reduction of fluoroacetamides with diborane. J. Org. Chem. 29, 2870–2872 (1964).

LeTourneau, M. E. & McCarthy, J. R. A novel synthesis of α-fluoroacetonitriles. Application to a convenient preparation of 2-fluoro-2-phenethylamines. Tetrahedron Lett. 25, 5227–5230 (1984).

Hamman, S. & Beguin, C. G. Selective reduction of β-fluoroazides to β-fluoroamines. J. Fluor. Chem. 37, 191–196 (1987).

Xue, F. et al. Potent and selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitors with improved cellular permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 554–557 (2010).

Schulte, M. L. & Lindsley, C. W. Highly diastereoselective and general synthesis of primary β-fluoroamines. Org. Lett. 13, 5684–5687 (2011).

Davies, S. G., Fletcher, A. M., Frost, A. B., Roberts, P. M. & Thomson, J. E. Asymmetric synthesis of substituted anti-β-fluorophenylalanines. Org. Lett. 17, 2254–2257 (2015).

Pupo, G. et al. Hydrogen bonding phase-transfer catalysis with potassium fluoride: enantioselective synthesis of β-fluoroamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2878–2883 (2019).

Xi, Y., Wang, C., Zhang, Q., Qu, J. & Chen, Y. Palladium-catalyzed regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective 1,2-arylfluorination of internal enamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2699–2703 (2021).

Chen, P. & Liu, G. Advancements in aminofluorination of alkenes and alkynes: convenient access to β-fluoroamines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 4295–4309 (2015).

Kong, W., Merino, E. & Nevado, C. Divergent reaction mechanisms in the aminofluorination of alkenes. Chimia 68, 430–435 (2014).

Serguchev, Y. A., Ponomarenko, M. V. & Ignat’ev, N. V. Aza-fluorocyclization of nitrogen-containing unsaturated compounds. J. Fluor. Chem. 185, 1–16 (2016).

Stavber, S., Pecan, T. S., Papež, M. & Zupan, M. Ritter-type fluorofunctionalisation as a new, effective method for conversion of alkenes to vicinal fluoroamides. Chem. Commun. 19, 2247–2248 (1996).

Qiu, S., Xu, T., Zhou, J., Guo, Y. & Liu, G. Palladium-catalyzed intermolecular aminofluorination of styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2856–2857 (2010).

Kong, W., Feige, P., Haro, T. & Nevado, C. Regio- and enantioselective aminofluorination of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2469–2473 (2013).

Zhang, H., Song, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J. & Zhang, Q. Regioselective radical aminofluorination of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 11079–11083 (2014).

Jiang, H. & Studer, A. Amidyl radicals by oxidation of α-amido-oxy acids: transition-metal-free amidofluorination of unactivated alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10707–10711 (2018).

Mennie, K. M., Banik, S. M., Reichert, E. C. & Jacobsen, E. N. Catalytic diastereo- and enantioselective fluoroamination of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4797–4802 (2018).

Wang, C., Tu, Y., Ma, D. & Bolm, C. Photocatalytic fluoro sulfoximidations of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14134–14137 (2020).

Guo, P. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed divergent aminofluorination and diamination of styrenes with N-fluorosulfonamides. Org. Lett. 23, 4067–4071 (2021).

Schäfer, M., Stünkel, T., Daniliuc, C. G. & Gilmour, R. Regio- and enantioselective intermolecular aminofluorination of alkenes via iodine(I)/iodine(III) catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205508 (2022).

Ito, Y., Adachi, A., Aikawa, K., Nozaki, K. & Okazoe, T. N-Fluorobenzenesulfonimide (NFSI) analogs with deprotectable substituents: synthesis of β-fluoroamines via catalytic aminofluorination of styrenes. Chem. Commun. 59, 9195–9198 (2023).

Saavedra-Olavarría, J., Arteaga, G. C., López, J. J. & Pérez, E. G. Copper-catalyzed intermolecular and regioselective aminofluorination of styrenes: facile access to β-fluoro-N-protected phenethylamines. Chem. Commun. 51, 3379–3382 (2015).

Mo, J.-N., Yu, W.-L., Chen, J.-Q., Hu, X.-Q. & Xu, P.-F. Regiospecific three-component aminofluorination of olefins via photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 20, 4471–4474 (2018).

Lu, D.-F., Zhu, C.-L., Sears, J. D. & Xu, H. Iron(II)-catalyzed intermolecular aminofluorination of unfunctionalized olefins using fluoride ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11360–11367 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Three-component aminofluorination of alkenes with electronically rich amino sources. Chem 8, 1147–1163 (2022).

Feng, G., Ku, C. K., Zhao, J. & Wang, Q. Copper-catalyzed three-component aminofluorination of alkenes and 1,3-dienes: direct entry to diverse β-fluoroalkylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 20463–20471 (2022).

Phelps, M. E. Positron emission tomography provides molecular imaging of biological processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9226–9233 (2000).

Rudin, M. & Weissleder, R. Molecular imaging in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2, 123–131 (2003).

Willmann, J. K., van Bruggen, N., Dinkelborg, L. M. & Gambhir, S. S. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 591–607 (2008).

Ametamey, S. M., Honer, M. & Schubiger, P. A. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem. Rev. 108, 1501–1516 (2008).

James, M. L. & Gambhir, S. S. A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol. Rev. 92, 897–965 (2012).

Gasser, V. C. M., Makai, S. & Morandi, B. The advent of electrophilic hydroxylamine-derived reagents for the direct preparation of unprotected amines. Chem. Commun. 58, 9991–10003 (2022).

Minisci, F. & Galli, R. New types of amination of olefinic, acetylenic and aromatic compounds by hydroxylamine-o-sulfonic acid and hydroxylamines/metal salts redox systems. Tetrahedron Lett. 6, 1679–1684 (1965).

Jat, J. L. et al. Direct stereospecific synthesis of unprotected N-H and N-Me aziridines from olefins. Science 343, 61–65 (2014).

Legnani, L. & Morandi, B. Direct catalytic synthesis of unprotected 2-amino-1-phenylethanols from alkenes by using iron(II) phthalocyanine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2248–2251 (2016).

Legnani, L., Prina-Cerai, G., Delcaillau, T., Willems, S. & Morandi, B. Efficient access to unprotected primary amines by iron-catalyzed aminochlorination of alkenes. Science 362, 434–439 (2018).

Cho, I. et al. Enantioselective aminohydroxylation of styrenyl olefins catalyzed by an engineered hemoprotein. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 3138–3142 (2019).

Makai, S., Falk, E. & Morandi, B. Direct synthesis of unprotected 2 azidoamines from alkenes via an iron-catalyzed difunctionalization reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21548–21555 (2020).

Yu, D., Shing, K.-P., Liu, Y., Liu, H. & Che, C.-M. Ruthenium porphyrin catalysed intermolecular amino-oxyarylation of alkenes to give primary amines via a ruthenium nitrido intermediate. Chem. Commun. 56, 137–140 (2020).

Chatterjee, S. et al. A combined spectroscopic and computational study on the mechanism of iron-catalyzed aminofunctionalization of olefins using hydroxylamine derived N-O reagent as the “amino” source and “oxidant”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2637–2656 (2022).

Gao, S. et al. Enzymatic nitrogen incorporation using hydroxylamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20196–20201 (2023).

Pozhydaiev, V., Vayer, M., Fave, C., Moran, J. & Leboeuf, D. Synthesis of unprotected β-arylethylamines by iron(II)-catalyzed 1,2-aminoarylation of alkenes in hexafluoroisopropanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215257 (2023).

Pozhydaiev, V., Paparesta, A., Moran, J. & Leboeuf, D. Iron(II)-catalyzed 1,2-diamination of styrenes installing a terminal NH2 group alongside unprotected amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202411992 (2024).

Chu, D. & Ellman, J. A. Stereospecific synthesis of unprotected, α,β-disubstituted tryptamines and phenethylamines from 1,2-disubstituted alkenes via a one-pot reaction sequence. Org. Lett. 25, 3654–3658 (2023).

Smith, M. J. S., Tu, W., Robertson, C. M. & Bower, J. F. Stereospecific aminative cyclizations triggered by intermolecular aza-Prilezhaev alkene aziridination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312797 (2023).

Tu, W., Farndon, J. J., Robertson, C. M. & Bower, J. F. An aza-Prilezhaev-based method for inversion of regioselectivity in stereospecific alkene 1,2-aminohydroxylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409836 (2024).

Zinner, D. G. Über o-acylierte hydroximsäure-ester und ihre Spaltung zu unsubstituierten o-acylhydroxylaminen. X. Mitteilung über hydroxylamin-derivate. Arch. Pharm. 293, 657–661 (1960).

Lee, J.-W. et al. Hydrogen-bond promoted nucleophilic fluorination: concept, mechanism and applications in positron emission tomography. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 4638–4650 (2016).

Liang, S., Hammond, G. B. & Xu, B. Hydrogen bonding: regulator for nucleophilic fluorination. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 17850–17861 (2017).

Sabir, S., Kumar, G. & Jat, J. L. O-Substituted hydroxyl amine reagents: an overview of recent synthetic advances. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 3314–3327 (2018).

Guimond, N., Gorelsky, S. I. & Fagnou, K. Rhodium(III)-catalyzed heterocycle synthesis using an internal oxidant: improved reactivity and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6449–6457 (2011).

Makai, S., Falk, E. & Morandi, B. Preparation of O-pivaloyl hydroxylamine triflic acid. Org. Synth. 97, 207–216 (2020).

Carpino, L. A. O-acylhydroxylamines. II. O-mesitylenesulfonyl-, O-p-toluenesulfonyl- and O-mesitoylhydroxylamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 82, 3133–3135 (1960).

See, Y. Y. & Sanford, M. S. C−H amination of arenes with hydroxylamine. Org. Lett. 22, 2931–2934 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Fe-catalyzed amination of (hetero)arenes with a redox-active aminating reagent under mild conditions. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 563–567 (2017).

Venkatachalam, T. K., Sudbeck, E. A., Mao, C. & Uckun, F. M. Piperidinylethyl, phenoxyethyl and fluoroethyl bromopyridyl thiourea compounds with potent anti-HIV activity. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 11, 329–336 (2000).

Murray, T. K. et al. LY503430, a novel α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor potentiator with functional, neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects in rodent models of parkinson’s disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306, 752–762 (2003).

Magnus, N. A. et al. Diastereomeric salt resolution based synthesis of LY503430, an AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid). potentiator. Org. Process Res. Dev. 9, 621–628 (2005).

Duthion, B., Pardo, D. G. & Cossy, J. Enantioselective synthesis of β-fluoroamines from β-amino alcohols: application to the synthesis of LY503430. Org. Lett. 12, 4620–4623 (2010).

Maestre, L., Sameera, W. M. C., Díaz-Requejo, M. M., Maseras, F. & Pérez, P. J. A general mechanism for the copper- and silver-catalyzed olefin aziridination reactions: concomitant involvement of the singlet and triplet pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1338–1348 (2013).

Sorokin, A. B. Phthalocyanine metal complexes in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 113, 8152–8191 (2013).

Sorlin, A. M. et al. The role of trichloroacetimidate to enable iridium-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective allylic fluorination: a combined experimental and computational study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14843–14852 (2019).

Ma, X. et al. Iron phthalocyanine-catalyzed radical phosphinoylazidation of alkenes: a facile synthesis of β-azido-phosphine oxide with a fast azido transfer step. Chin. J. Catal. 42, 1634–1640 (2021).

Nehru, K., Seo, M. S., Kim, J. & Nam, W. Oxidative N-dealkylation reactions by oxoiron(IV) complexes of nonheme and heme ligands. Inorg. Chem. 46, 293–298 (2007).

Zhou, Y. et al. Mechanism and reaction channels of iron-catalyzed primary amination of alkenes by hydroxylamine reagents. ACS Catal. 13, 1863–1874 (2023).

Suarez, A. I. O., Lyaskovskyy, V., Reek, J. N. H., van der Vlugt, I. J. I. & de Bruin, B. Complexes with nitrogen-centered radical ligands: classification, spectroscopic features, reactivity, and catalytic applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12510–12529 (2013).

Hennessy, E. T. & Betley, T. A. Complex N-heterocycle synthesis via iron-catalyzed direct C-H bond amination. Science 340, 591–595 (2013).

Lu, D.-F., Zhu, C.-L., Jia, Z.-X. & Xu, H. Iron(II)-catalyzed intermolecular amino-oxygenation of olefins through the N–O bond cleavage of functionalized hydroxylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13186–13189 (2014).

Ye, C.-X., Dansby, D. R., Chen, S. & Meggers, E. Expedited synthesis of α-amino acids by single-step enantioselective α-amination of carboxylic acids. Nat. Synth. 2, 645–652 (2023).

Miller, P. W., Long, N. J., Vilar, R. & Gee, A. D. Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N radiolabels for positron emission tomography. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 8998–9033 (2008).

Brooks, A. F., Topczewski, J. J., Ichiishi, N., Sanford, M. S. & Scott, P. J. H. Late-stage [18F]fluorination: new solutions to old problems. Chem. Sci. 5, 4545–4553 (2014).

Preshlock, S., Tredwell, M. & Gouverneur, V. 18F-labeling of arenes and heteroarenes for applications in positron emission tomography. Chem. Rev. 116, 719–766 (2016).

Deng, X. et al. Chemistry for positron emission tomography: recent advances in 11C-, 18F-, 13N-, and 15O-labeling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2580–2605 (2019).

Chen, W. et al. Direct arene C-H fluorination with 18F- via organic photoredox catalysis. Science 364, 1170–1174 (2019).

Halder, R. & Ritter, T. 18F-fluorination: challenge and opportunity for organic chemists. J. Org. Chem. 86, 13873–13884 (2021).

Leibler, I. N.-M., Gandhi, S. S., Tekle-Smith, M. A. & Doyle, A. G. Strategies for nucleophilic C(sp3)−(radio)fluorination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9928–9950 (2023).

Lin, D., Lechermann, L. M., Huestis, M. P., Marik, J. & Sap, J. B. I. Light-driven radiochemistry with fluorine-18, carbon-11 and zirconium-89. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317136 (2024).

Han, J. et al. (Radio)fluoro-iodination of alkenes enabled by a hydrogen bonding donor solvent. Org. Lett. 26, 3435–3440 (2024).

Zeng, X., Li, J., Ng, C. K., Hammond, G. B. & Xu, B. (Radio)fluoroclick reaction enabled by a hydrogen-bonding cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2924–2928 (2018).

Ortalli, S., Ford, J., Trabanco, A. A., Tredwell, M. & Gouverneur, V. Photoredox nucleophilic (radio)fluorination of alkoxyamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11599–11604 (2024).

Herth, M. M. et al. On the consensus nomenclature rules for radiopharmaceutical chemistry–reconsideration of radiochemical conversion. Nucl. Med. Biol. 93, 19–21 (2021).

Mu, L. et al. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of a 2-oxoquinoline carboxylic acid derivative for PET imaging the cannabinoid type 2 receptor. Pharmaceuticals 7, 339–352 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22371036, J.F.; 21971034, J.F.; 22573090, G.C.; 22422110, G.C.; 22401041, Y.L.), Jilin Province Scientific and Technological Development Program (20230508107RC, J.F.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (RCYX20200714114736199, G.C.), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2019A1515011865, G.C.), Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2025-06928 and DGECR-2025-00486, C.Z.; NSERC PDF-568046-2022, M.R.B.), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR507113, C.Z.) for financial support. N.V. thanks the Azrieli Foundation, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Ontario Research Fund and the Canada Research Chairs Program for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and J.F. designed and performed the experiments. X.Z., Z.W. and D.L. assisted in completing the experiments. Y.Z. and G.-J.C. performed the density functional theory calculations and wrote the sections for the manuscript. J.N. performed the ESI-MS experiments to capture the intermediates. M.R.B., H.L., O.Z.E., N.V. and C.Z. designed and carried out all radiochemical experiments and wrote the radiochemical sections of the manuscript. Q.Z., C.Z. and J.F. directed the project and wrote the manuscript. All the authors were involved in the interpretation of the results presented in the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhou, Y., Bortolus, M.R. et al. Iron-catalyzed three-component amino(radio)fluorination of alkenes to unprotected β-(radio)fluoroamines. Nat Commun 16, 10917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65880-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65880-z