Abstract

Electrofusion is a widely used technique for inducing membrane merging in biological systems, with applications ranging from hybrid lipid architectures to therapeutic delivery. However, the direct application of conventional electrofusion to advanced nanoscale drug carriers, such as cell membrane hybrid LNPs (cLNPs), faces challenges due to diminished dielectric response and uncontrolled particle dynamics. To address these limitations, we report a periodic asymmetric field (PAF) strategy that combines microfluidic flow with periodic electric fields to enhance nanoscale electrofusion. We systemically investigate the underlying mechanisms using computational fluid dynamics simulations, and subsequently fabricate and optimize a PAF-guided microfluidic electrofusion device (PAF-MED) for the controlled synthesis of cLNPs. These PAF-MED-synthesized cLNPs demonstrate improved fusion efficiency, augmented targeting capability, and superior therapeutic efficacy in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis murine models. This approach represents a unique advancement in the nanoscale manipulation of drug carriers towards better bio-functionality and reproducibility beyond conventional capability of electrofusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrofusion stands as a well-established and versatile technique for inducing membrane merging in biological systems through the application of controllable electric fields1,2. This approach offers distinctive advantages, including rapid fusion kinetics, minimal reliance on chemical agents, and the potential for controlled assembly of defined structures and compositions3,4. Consequently, electrofusion holds great promise for generating hybrid lipid architectures for diverse therapeutic and research applications, particularly where minimizing membrane protein denaturation and preserving the structural and functional integrity of essential membrane components are critical2,5,6. However, the direct application of conventional electrofusion methodologies to lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) encounters inherent limitations. The diminutive size of LNPs results in weak dielectric responses under electric fields, coupled with significant Brownian motion that impedes effective particle trapping and alignment2,7. Furthermore, the high electric field strengths typically required can induce irreversible membrane damage and lead to suboptimal fusion efficiency in these nanoscale lipid systems8,9,10,11.

To address the challenges associated with manipulating and fusing nanoscale entities like LNPs, asymmetric fields (AFs) emerge as a promising alternative strategy. Characterized by spatially nonuniform dynamic properties, AFs enable precise spatiotemporal manipulation of particle trajectories through tailored structural designs and controlled flow parameters12,13,14. This unique capability has led to applications across various disciplines, including triggering microscale chemical reactions15,16, facilitating the self-assembly of colloidal systems in soft matter physics17,18, and enabling nanoscale characterization through precise flow manipulation19,20. Within nanotechnology, the introduction of AFs has been leveraged to induce nonlinear responses and disrupt spatial symmetry in the forces acting on particles, significantly enhancing nanoparticle separation of biological macromolecules and bioparticles such as viruses, cells, and exosomes, demonstrating their efficacy in improving particle positioning and isolation efficiency14,19,21,22. Building upon this established ability to accurately modulate particle behavior and geometry10,12, we posit that asymmetric fields hold significant, yet largely unexplored, potential for achieving efficient and controlled nanoscale assembly of LNPs, offering a pathway to overcome the limitations of conventional electrofusion in this crucial domain.

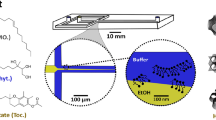

Here, we present the design and implementation of a periodic asymmetric field (PAF) that integrates a microfluidic flow field with a periodic electric field to control the motion of LNPs in well-controlled microfluidic channels, achieving enhanced nanoscale electrofusion (Fig. 1a). The cell membrane hybrid LNPs (cLNPs) were chosen as model nanoparticles given the enhanced biocompatibility and functional versatility for effective delivery and precise localization to lesions23,24,25. Using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, we established a multi-physics modeling scheme based on the electro-hydrodynamics (EHD) principles with a designed PAF to study how field parameters affect the dynamics of both cell membrane (CM) and LNPs (Fig. 1b)26. Based on modeling results, we further fabricated a PAF-guided microfluidic electrofusion device (PAF-MED), and systematically investigated the effects of various engineering parameters to enable controllable syntheses of cLNPs (Fig. 1c, d). In bleomycin (BLM)-induced pulmonary fibrosis (PF) murine models, cLNPs synthesized using the PAF-MED platform enabled highly efficient delivery of small interfering RNA (siRNA) to injured lung epithelial cells (LECs), resulting in a significant attenuation of fibrotic progress.

a Schematic of a nanoscale lipid system and electrofusion process in the periodic asymmetric fields consisting of a microfluidic flow field and a periodic electric field. b Schematic diagram of a multi-physics simulation model based on computational fluid dynamics. c Schematic of a periodic asymmetric fields inspired microfluidic electrofusion device (PAF-MED). The schematic in (a and c was created by the authors using Adobe Illustrator software (version 2023). d Representative cryo-TEM image of cell membrane hybrid lipid nanoparticles (cLNPs) synthesized with PAF-MED (scale bar, 100 nm). Representative data of three independent experiments are shown.

Results

Systematic Investigation of PAF Based on CFD Analysis

The PAF was generated by integrating periodic electric fields with laminar flow. These dual mechanisms coupled to form a spatiotemporally modulated hybrid field (Fig. 2a). Within geometrically confined microchannels, fluid shear generated viscous drag forces, while interdigitated electrode arrays established spatially non-uniform electric fields. The synergistic interaction of these forces further facilitated the CM-LNP collision and enabled controlled nanoscale electrofusion.

a Schematic of the cell membrane (CM) and lipid nanoparticle (LNP) electrofusion (CM-LNP) system in the periodic asymmetric fields using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis for evaluation of fusion efficiency. The schematic figure was created by the authors using Adobe Illustrator software (version 2023). b Fluorescence intensity of the CM-LNP system before (blue) and after (red) electrofusion, showing a signal increase at 520 nm and a signal decrease at 580 nm for the formation of cLNPs. (Units of intensity are arbitrary units) c Fusion efficiencies at different conditions: PAF group, flow-field-only group, electric-field-only group and blank control. (Red with electrical stimulation, blue without stimulation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Exact p-values < 0.00001 are presented in comparison order, 4 × 10−10, 1 × 10−8, 4 × 10−10). d A microfluidic numerical model integrating an interdigitated-electrode array for CFD analysis. e Particle trajectories of positive LNPs (+2000 e, 105 nm) in the PAF induced by the multi-physics model. f Particle distributions of different type particles: positive LNPs (red in the PAF, gray without electric field), neutral LNPs (blue), negative LNPs (yellow) and CMs (purple). The raw data were smoothed using the Adjacent-Averaging method over 5 points in Origin 2022. g Fitting of experimental data for fusion efficiency versus coupled concentration fluctuations intensity (Δcsyn*). (data are presented as mean values ± SD). h Fitting of Δc* with three dimensionless parameters: geometric confinement factor ξ1, electrode asymmetry parameter ξ2, electro-viscous force ratio ξ3 and initial particle concentration c0. i–l Fusion efficiency dependent on key variables correlated with three dimensionless parameters: height of channel h (i), asymmtry of electrodes l1-l2 (j), carrying charges q (modulated by the ratio of ionizable lipid, exact p-values < 0.00001 are presented in comparison order, 1 × 10−8, 2 × 10−9), (k) and initial concentration c0 for LNPs and CMs (l). LNPs were fabricated with the prescription of DOTAP:DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE:NBD-PE:Rho-PE at molar ratio of 40:40:9:9:1:1. NS, no significant difference, p > 0.05. (n = 5, biological independent replicates, exact p-values < 0.00001 are presented in comparison order, 1 × 10−8, 7 × 10−11). All data are presented as mean values ± SD. The P-value in the figure was calculated by an unpaired Student’s t test.

To quantitatively assess membrane fusion efficiency, we employed a Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) system using Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl phosphatidylethanolamine (Rho-PE, acceptor) and N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)-Phosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-PE, donor) as fluorescent labels of parent LNPs. (Fig. 2b, see “Methods” for details). A series of control experiments were conducted with standalone microfluidic and electrofusion groups to assess whether the enhancement originated from the coordinated effects of the PAF. Four experimental groups were defined: PAF group, flow-field-only group, electric-field-only group, and a blank control group (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S1). Fusion efficiency was quantified using FRET assays, which revealed a fusion efficiency of 82.86 ± 2.48% in the PAF group. This result represents a 6.8-fold and 2.2-fold increase compared to the flow-field-only group (12.14 ± 1.75%) and the electric-field-only group (38.09 ± 2.80%), respectively (p < 0.00001, n = 5). These data suggest that the observed enhancement in fusion efficiency is attributable to the synergistic effects of both the flow and electric fields, underscoring the critical role of the coordinated action between these two parameters in optimizing the fusion process.

We hypothesized that the enhancement in fusion efficiency could be attributed to the precise modulation of the trajectories of LNP and CM within the PAF. To systematically investigate this hypothesis, we employed a multi-physics CFD simulation framework grounded in the principles of electrohydrodynamics. The simulation incorporated an interdigitated electrode configuration, which generated an electric field aligned along the x-axis (Fig. 2d, see “Methods” and Supplementary Movies 1-2 for details). Simulation results revealed that charged particles displayed a distinct periodic spatial distribution along the x-direction, presenting a random distribution along the y-direction under PAF conditions. This was in stark contrast to the separation of particles observed under an orthogonal uniform alternating field, as shown in Fig. 2e and Supplementary Figs. S2, S3. These findings suggested that the unique and highly localized modulation of particle trajectories within the PAF fluctuates the concentration of LNP and CM, which may be instrumental in enhancing fusion efficiency.

To quantify the modulation effect of concentration fluctuations on particle fusion, we defined the normalized local concentration as \({c}^{*}=\frac{c}{{c}_{0}}\), where c is the instantaneous local concentration and c0 the initial concentration. Particle clusters with distinct physicochemical properties generated periodic c* oscillations in the hybrid field, with their amplitudes influencing by particle charge and size (Fig. 2f). The concentration fluctuation intensity was further defined as \(\Delta {c}^{*}={c}_{max }^{*}-{c}_{min }^{*}\) (c*max and c*min represent normalized concentration extremes within a cycle).

According to the kinetic derivation from basic collision theory, we employed a dimensionless product of concentration fluctuation intensities to represent the nonlinear coupling between LNP and CM, which contributed to synergistic amplification of the collision frequency (see Supplementary Note S1 for detailed derivations).

where ΔcLNP* and ΔcCM* correspond to the individual fluctuation intensities of LNP and CM systems.

Systematic parameter sweeps revealed an apparent positive correlation between \(\Delta {{c}_{{{{\rm{syn}}}}}}^{\ast }\) and the experimentally obtained fusion efficiency (R2 = 0.96, Fig. 2g). This correlation arose from the role of dynamic concentration gradients in modulating particle collision probabilities: an increase in Δc* directly enhanced local contact frequency between heterogeneous particles, thereby driving the following fusion process. Consequently, Δc* served as a reliable predictor of fusion efficiency, establishing a theoretical framework for subsequent system design and optimization in terms of maximizing the fusion efficiency of nanoparticles. Multiple parameters may influence the value of Δc*, including channel height (h), electric field asymmetry (the lengths of high-potential electrodes l1 and low-potential electrodes l2), and the intrinsic properties of particles (carrier charges q and radii r). Notably, simulation results indicated negligible correlation between initial concentration c0 and the Δc* (R2 < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. S4). The conductivity of the fluid also exerted negligible influence on particle distribution (Supplementary Fig. S5), but influenced the electrofusion process through regulation of lipid membrane electroporation efficiency, Joule heating effect, and membrane integrity1.

Guided by the Buckingham π theorem of dimensional analysis, three critical, dimensionless parameters were defined as geometric confinement factor \({\xi }_{1}=\frac{L}{h}\), electrode asymmetry parameter \({\xi }_{2}=\frac{{l}_{1}\,-\,{l}_{2}}{L}\), electro-viscous force ratio \({\xi }_{3}=\frac{{qU}}{\eta {vr}{l}_{0}}\), where l0 is the inter-electrode gap, L = 2l0 + l1 + l2 the interdigitated electrode period length, U the electrode potential difference, v the fluid velocity, and η the dynamic viscosity of the fluid.

Through physical simulations and multivariate regression analysis, we established the functional dependence of Δc* on these dimensionless parameters (see Supplementary Note S2 for detailed derivations). A semi-empirical equation (Eq. (2)) was then derived through nonlinear combinations of ξ1, ξ2, and ξ3, enabling multiscale prediction of Δc* across diverse PAF configurations.

CFD simulations was conducted for more than 40 combinations of the three dimensionless parameters (ξ1, ξ2, and ξ3), where each of the three parameters varied independently (Fig. 2h). The concentration fluctuation intensity Δc* agreed well with Eq. 2 for the parameters a = 0.01136 and b = 0.00923 with a R2 = 0.93.

Building on the simulation results, we further conducted experimental parametric studies on key variables correlated with three dimensionless parameters to assess their influence on fusion efficiency, as well as to validate the accuracy of the CFD simulation. The geometric confinement factor (\({\xi }_{1}=\frac{L}{h}\)) was inversely correlated with channel height, indicating that reducing the channel height can enhance fusion efficiency. Different channel heights (h = 50, 75, and 100 μm) indeed exhibited negative correlations with fusion efficiency (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. S6a), confirming the theoretical assumption that narrower channels may enhance chances of particle collision by strengthening hydrodynamic-electric field coupling (Supplementary Fig. S7).

The electrode asymmetry parameter (\({\xi }_{2}=\frac{{l}_{1}\,-\,{l}_{2}}{L}\)) indicated the electrode asymmetry was related to the length difference of l1 and l2 with fixed L. Different electrode arrays were fabricated to assess the effect of electrode symmetry on CM and LNP fusion (Supplementary Fig. S8). Fusion efficiency exhibited an inverted U-shaped trend as the electrode asymmetry parameter ξ2 increased (Fig. 2j and Supplementary Fig. S6b). Peak efficiency (91.76 ± 1.99%) occurred at the symmetric electrode configuration (l1:l2 = 1:1), implying that the symmetry of electrode arrays was critical for enhancing fusion efficiency. Symmetry breaking in the electrode configuration induced a transition from periodic electric field distributions to orthogonal uniform field patterns, consequently inhibited the oscillatory particle trajectories (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S9).

The electro-viscous force ratio (\({\xi }_{3}=\frac{{qU}}{\eta {vr}{l}_{0}}\)) demonstrated a strong positive correlation between the particle charge-to-radius ratio and fusion efficiency (R2 = 0.95, Supplementary Fig. S10). To further explore the influence of charge number (q) on fusion efficiency, we assessed the fusion between LNPs and various species with differing charge numbers. As charge number was directly correlated with the measured zeta potential27, positively or negatively charged LNPs containing 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) or Dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol (DOPG) at molar ratios of 10%, 30%, and 50% were employed (Supplementary Table S1). As the charge number increased, fusion efficiency escalated from 33.76 ± 1.18% to 91.41 ± 1.73% (Fig. 2k), aligning with the linear relation governed by the electro-viscous force ratio ξ₃.

Finally, to experimentally demonstrate the negligible impact of c0 on fusion efficiency revealed by the CFD simulation (Supplementary Fig. S4), we performed electrofusion of CMs and LNPs at different particle concentrations (c0 = 5, 1, 0.2 μmol·mL−1). Results showed that there was no statistical significance among all groups, matching with simulation results (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Fig. S6c). Collectively, the experimental data demonstrated good agreement with simulation-derived formulas based on the dimensionless parameters ξ₁, ξ₂, and ξ₃, validating the predictive capability and reliability of the theoretical framework within this multi-physics modeling scheme. These findings not only substantiate the utility of PAF for optimizing the fusion efficiency for the existing CM-LNPs system, but also suggest the potential to extend to the modulation and hybridization of a wide variety of other nanoscale lipid systems.

Design and Fabrication of PAF-MED

Based on the aforementioned numerical modeling results, we designed and fabricated a PAF-guided microfluidic electrofusion device (PAF-MED) for the high-throughput synthesis of cLNPs. The PAF-MED comprised four functional modules for LNP preparation and drug loading, backflow-prevention, LNP-CM mixing, and electrofusion section, respectively (Fig. 3a). Fabricated using soft lithography and UV lithography, the PAF-MED consisted of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold containing microfluidic structures, tightly bonded to a glass wafer equipped with electrofusion electrodes via plasma treatment (Supplementary Fig. S11). The microfluidic section of the PAF-MED can withstand a total flow rate of up to ~ 4 mL·min−1, matching the high-pressure requirements necessary for LNP synthesis.

a Schematic illustration of PAF-MED functionalization modules. The schematic figure was created by the authors using Adobe Illustrator software (version 2023). b Details of key structures in PAF-MED. SEM images of cross nozzle (b1), Tesla valve (b3) and straight channel (b5). Scale bar, 400 μm. Simulation of flow velocity distribution in cross nozzle (b2) and Tesla valve (b4). Height scan of the different microfluidics from film thickness measurement (b6). c photograph of Au electrodes and simulation of electric field distribution. Scale bar, 100 μm. d–f Heatmaps of cLNPs size (d, red), PDI (e, blue) with varying flow velocity ratios; Fusion efficiency (f, yellow) with varying pulse voltages and frequencies. g–i Fusion efficiency with different signal patterns (g), different feed ratio (h), different phosphate buffer saline (PBS) concentration (i). (g–i, n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD) j–k Sizes (measured by NTA, red) and PDIs (measured by DLS, blue), (j) and Zeta potential (k) of LNPs, CMs, mixture of LNPs and CMs and cLNPs by PAF-MED. Fusion efficiency was derived from FRET analysis (j–k, n = 3, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). LNPs were fabricated by prescription of DOTAP:DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE at molar ratio of 40:40:10:10. NS, no significant difference, p > 0.05. The P-value in the figure was calculated by an unpaired Student’s t-test.

Key structures within the microchannel and microelectrodes were characterized using scanning electronic microscopes, and simulations of flow fields with COMSOL are illustrated in Fig. 3b to show the functions of these structures (see “Methods” for details). The LNP synthesis and drug-loading processes involved an organic phase inlet and two aqueous phase inlets converging at a cross-shaped structure (Fig. 3b, b1). This design facilitated a dramatic increase in local shear flow rates between different flow phases (Fig. 3b, b2), generating the desired LNPs. To enhance mixing efficiency, Tesla valve structures were implemented that applied additional shear forces via vortices (Fig. 3b, b3, b4), further regulating the LNP size and polydispersity index (PDI). The electrofusion section comprises orthogonally coupled rectilinear microfluidic channels and a microelectrode array (MEA). Based on prior CFD simulations of channel geometry, we selected channel height of 50 μm (Fig. 3b, b5, b6). The MEA consisted of interdigitated electrodes with a 50-to-50 μm electrode-to-gap configuration (Fig. 3c). Electric field simulation revealed the field strength distribution generated by the MEA (see the “Methods” for details), which facilitated uniform and stable electrofusion of CMs and LNPs.

Having determined the optimized geometry of PAF-MED based on numerical modeling, we next optimized the synthesis conditions for cLNPs, including size, PDI, fusion efficiency, concentration of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer, cholesterol concentration and type of electrical signal. Fluid distribution experiments confirmed the efficacy of the cross-shaped nozzle and Tesla valve designs for flow rate regulation and fluid mixing (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Flow rate simulations and distribution experiments under varying conditions (Supplementary Figs. S12, 13) revealed that flow rate and distribution were primarily dependent on the flow rates and their ratios of the injected fluids. This dependency allowed for precise control over LNP size and PDI3,28. Through orthogonal experiments varying flow rates and ratios, heatmaps of cLNP particle size and PDI were generated (Fig. 3d, e). Results showed that as flow rates and ratios increased, shear flow velocity within the microchannel also increased, leading to a reduction in LNP particle size and PDI. The PAF-MED thus enabled precise control over LNP size and uniformity, producing highly uniform (PDI ~ 0.1) and small-sized (~100 nm) LNPs across various charges and formulations (Supplementary Fig. S14). To balance the durability of the MED and achieve appropriately sized LNPs, subsequent experiments were conducted with an aqueous phase flow rate of 700 μL·min−1 and an aqueous/organic phase flow rate ratio of 7.5 (highlighted in Fig. 3d, e).

As the effectiveness of electrofusion may depend on pulse voltage and frequency (pulse duration), a series of orthogonal experiments were conducted to evaluate these variables, generating a heatmap of fusion efficiency by FRET analysis (Fig. 3f). Electric field simulations (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S15) showed that at a pulse voltage of 5 V (maximum field strength of 1.73 kV·cm−1), the field strength was insufficient to induce electroporation of LNPs and CMs, resulting in low fusion efficiency6,7,29. Conversely, a pulse voltage of 25 V (maximum field strength of 3.34 kV·cm−1) caused irreversible damage to both LNPs and CMs, reducing fusion efficiency. Similarly, high frequencies (short pulse durations) provided inadequate electroporation time, while low frequencies (long pulse durations) created excessively large pores, causing irreversible membrane damage6,7,29. Optimization of pulse voltage and frequency identified the optimal electrofusion condition as a pulse frequency of 12.5 kHz and a pulse voltage of 10 V (highlighted in Fig. 3f). The results were further validated by confocal laser scanning microscopy observation and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Pearson’s R) analysis (Supplementary Fig. S16). Notably, the type of electrical signal also impacted the electrofusion process, with square wave pulses at a 50% duty ratio yielding the optimal effect (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. S17).

The feed ratio of CMs to LNPs and the cholesterol concentration were further optimized experimentally to enhance fusion efficiency. When the number ratio of the two precursors was set to 1:1, fusion efficiency exceeded 90%, a condition adopted for all subsequent cLNP synthesis (Supplementary Fig. S18). Increasing the cholesterol content within the formulation enhanced the rigidity of the LNPs, which, in turn, impaired the membrane fusion efficiency between CMs and LNPs. An optimal cholesterol content of 10% in the formulation was identified as the point at which CM-LNP fusion was maximized (Supplementary Fig. S19). In addition, fusion efficiency was found to increase with rising PBS concentration, peaking at 1 ×. However, at 2 × PBS concentration, fusion efficiency declined significantly due to LNP precipitation from the buffer solution (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. S20). Under these optimized synthesis conditions, the resulting cLNPs exhibited diameters of 135.1 ± 3.8 nm and a significant reduction in zeta potential, highlighting the effectiveness of the formulation conditions in modulating particle characteristics (Fig. 3j, k and Supplementary Figs. S21, S22).

Compatibility and characterization of cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED

We measured key parameters of synthesized cLNPs by PAF-MED, such as size, PDI, zeta potential, and fusion efficiency, to show the universal applicability of PAF-MED on a wide range of CM types including mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), erythrocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, epithelial (Tissue culture-1, TC-1), and tumor (Colorectal adenocarcinoma-2, Caco-2) cells (Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Fig. S23a). In particular, MSC membrane-based cLNPs (MSC-cLNPs) were shown to possess lesion-targeting capability that was inherited from their parental MSCs (e.g., specific targeting towards injured LECs30,31,32). Given these interesting properties, MSC-cLNPs were selected as a representative model for subsequent in vitro and in vivo demonstrations.

a–d Characterization of cLNPs synthesized from different cell membranes (mesenchymal stem cell, MSC, red; macrophage, deep blue; neutrophil, yellow; red blood cell, RBC, purple; epithelial, TC-1, green; tumor, Caco-2, light blue) and LNPs including sizes (a), PDIs (b), fusion efficiencies (c) and zeta potentials (d). (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). e, f Sizes measured by NTA (e) and PDIs measured by DLS (f) of MSC-cLNPs that prepared of anionic, uncharged or cationic charged phospholipid by PAF-MED (n = 3, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). g Cyro-TEM images of MSC-cLNPs that synthesized by PAF-MED. Scale bar, 100 nm. Representative data of three independent experiments are shown. h Fusion efficiency (detected by FRET assay) of MSC membrane and different charged LNPs (positive, neutral and negative) synthesized by PAF-MED. (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). i CD results of bare LNP and MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED, co-extrusion and sonication. j Relative intensity derived from dot blotting results of MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED, co-extrusion and sonication for cell membrane proteins including CD44, VLA-4, CD47 and CXCR4. (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD, a. u. stands for arbitary units). k Encapsulation efficiency of MSC-cLNPs on siRNA prepared by PAF-MED, co-extrusion and sonication (n = 5, biological independent replicates, exact p-values < 0.00001 are presented in comparison order, 4 × 10−15, 3 × 10−15). l Inhibition of Transforming growth factor β 1 (TGF-β1) expression in BLM injured LEC model after the treatment of TGF-β1-siRNA-loaded MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED, co-extrusion or sonication approaches (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). LNPs were fabricated by DOTAP (positive) or DOPG (negative), or DOPC (neutral):DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE at a molar ratio of 40:40:10:10. TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated LNPs were by D-Lin-MC3-DMA:DOTAP:DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE at molar ratio of 30:20:30:10:10. The P-value in the figure was calculated by an unpaired Student’s t test. One-way ANOVA was used for group comparisons.

Three types of phospholipids — positively charged (DOTAP), neutral (DOPC), and negatively charged (DOPG) — were used to prepare the MSC‑cLNPs, allowing the assessment of their compatibility across different lipid compositions. PAF-MED enabled precise control over the size distribution and PDI (Fig. 4e, f, Supplementary Figs. S23b and S24). Cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) imaging revealed that MSC-cLNPs synthesized using PAF-MED exhibited uniform morphology, good dispersion, and minimal size variation, with reduced incidence of aggregation or nested structural formation (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. S25). Moreover, the high fusion efficiency achieved by PAF‑MED was maintained across LNPs with different surface charge properties, as confirmed by FRET analysis, demonstrating the compatibility across different lipid compositions (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. S26). These findings were further corroborated by Nano flow cytometry (Nano FCM), a reliable tool for characterizing nanoscale vesicles33. The dual fluorescence positivity of MSC membranes and LNPs in MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED exceeded 90% regardless of the LNP’s charge properties (Supplementary Fig. S27), highlighting the robustness of the fusion process. These results were further validated by fluorescence signal colocalization and Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis (Supplementary Fig. S28), providing compelling evidence that hybrid fusion occurred in heterogeneous particles.

As sonication and co-extrusion are wildly employed in the literature to induce lipid membrane fusion, we also prepared MSC-cLNPs using these two conventional methods, following established protocols24,25,34,35,36 (see “Methods” for details). Given that preservation of CM proteins is critical for maintaining targeting capabilities37, we evaluated the secondary structure of membrane proteins in MSC-cLNPs fabricated via PAF-MED, sonication, and co-extrusion using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. At a constant protein concentration, disruption of protein structure would result in a decrease in CD absorption. CD analysis revealed that PAF-MED exerted the least impact on protein secondary structure among the three methods (Fig. 4i). In the CD spectra between 200–240 nm, all groups exhibited two negative peaks at 208 nm and 222 nm, indicative of abundant α-helical content38. The absolute ellipticity reflects the proportion of this secondary structure within the overall protein, with larger absolute values corresponding to higher α-helix content39. Notably, the PAF-MED group exhibited markedly higher absolute values in this region (Fig. 4i), indicating superior preservation of α-helical membrane protein structures. These α-helical domains are critical for activating and modulating conformational changes in key receptors such as chemokine receptors and integrins in the inflammatory tropism of MSC40,41,42. Hence, retaining a higher proportion of α-helical structure may facilitate more efficient targeting of MSC-cLNPs to inflammatory lesions. To further characterize membrane protein, we examined the orientation of four key targeting proteins—chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), integrin α4β1 (very late antigen-4, VLA-4), CD44 and CD47—previously identified as critical for lesion-specific targeting by MSC-derived cLNPs23,24,25,37. Dot blot assays confirmed that these proteins were predominantly oriented outward in the PAF-MED group, suggesting superior preservation of targeting functionality compared to sonication and co-extrusion (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. S29)43.

To evaluate drug loading and delivery capabilities, siRNA was used as a model nucleic acid therapeutic44,45. Gel electrophoresis showed that MSC-cLNPs prepared via PAF-MED efficiently condensed siRNA at weight ratios above 1:10 (Supplementary Fig. S30). Notably, the siRNA encapsulation efficiency in the PAF-MED group approached 100%, significantly outperforming mechanical methods (Fig. 4k).

Finally, a BLM-induced LEC injury model was used to assess intracellular delivery and therapeutic efficacy. MSC-cLNPs fabricated via PAF-MED demonstrated enhanced cellular uptake in injured LECs (Supplementary Fig. S31) and achieved the most pronounced downregulation of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), indicating superior therapeutic potential through attenuation of fibrosis-related signaling (Fig. 4l).

In vivo targeting and PF intervention

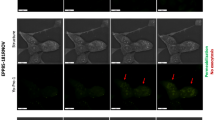

We next investigated the in vivo targeting toward injured LECs and the siRNA delivery efficiency of MSC-cLNPs prepared using PAF-MED, sonication, and co-extrusion methods in a murine PF model via inhalation (Fig. 5a). Intratracheal instillation of BLM challenge was used to induce the PF model. In vivo fluorescence observations showed that the MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED exhibited higher fluorescence intensity and more sustained signal retention in lung tissue, whereas those from the conventional, mechanical-based methods diminished within 8 hours (Fig. 5b). The inhalation delivery effectively restricted the biodistribution of cLNPs in the lungs, with minimal distribution to extrapulmonary organs (Fig. S32). Fluoresces analyses of lung sections demonstrated that MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED possessed a higher affinity with LECs (Fig. 5c). Quantitative examination of fluorescent signals demonstrated significant differences among the three groups after 24 hours (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5d).

a Schematic of inhalable delivery and lung epithelial cells (LECs) targeting of TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs to the PF model mice. The schematic figure was created in BioRender with proof permission. b Fluorescence signal of DiD-labeled MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods in lungs of PF mice at 4, 8, 12 and 24 h after inhalation. The MSC-cLNPs was labeled by DiD at 40 μM·kg−1. The inhalation was operated at 24 h after BLM challenging. c LECs staining (green, labeled by FITC-E-cad) and MSC-cLNPs (red, labeled by DiD) prepared by different methods in lungs 24 h post-inhalation delivery. The white arrow indicated the co-localization of LECs and cLNPs around the bronchus. Scale bar, 200 μm. d Quantified analysis of fluorescence signals of MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods in lungs of PF mice at 4, 8, 12 and 24 h after inhalation (n = 3, biological independent replicates). e Treatment regime and group assignment of PF mice. TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods were inhaled delivery into PF mice on day 1 and 7 post PF induction (n = 6, biological independent replicates). f TGF-β1 expression in lungs of PF model mice and received treatments by TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods at 21-day post-modeling (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD, exact p-values < 0.00001 are presented in comparison order, 3 × 10−7). g Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) expression in lungs of PF model mice and received treatments by TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods at 21-day post-modeling (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD, exact p-values < 0.00001 are presented in comparison order, 7 × 10−6, 3 × 10−6). h Hydroxyproline (HYP) expression in lungs of PF model mice and received treatments by TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods at 21-day post-modeling (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). i Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson staining of lungs of PF model mice and received treatments by TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods at 21-day post-modeling. j Quantified analysis of fibrotic ration in lungs of PF model mice and received treatments by TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated cLNPs from different methods (n = 5, biological independent replicates, data are presented as mean values ± SD). TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated LNPs were prepared by D-Lin-MC3-DMA:DOTAP:DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE at a molar ratio of 30:20:30:10:10. The P-value in the figure was calculated by an unpaired Student’s t test.

TGF-β1 was selected as the therapeutic target due to its well-established role in the onset and progression of PF46,47. Accordingly, TGF-β1-siRNA was encapsulated within MSC-cLNPs and administered via inhalation to the lungs on day 1, 4, and 7 following initial BLM challenge (Fig. 5e). All mice were sacrificed on day 21, and lung samples were collected to evaluate the therapeutic outcomes. TGF-β1 expression levels in lung tissues were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), revealing that the PAF-MED group exhibited the most effective downregulation of TGF-β1 among all treatment groups (Fig. 5f). During the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibroblast activation triggered by TGF-β1, elevated expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) may lead to extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and fibrotic tissue remodeling, eventually resulting in respiratory failure48. The PAF-MED group showed the most effective reduction in MMP9 expression (Fig. 5g). In addition, TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED demonstrated a significant reduction in hydroxyproline expression within the lungs (Fig. 5h), a collagen-specific amino acid serving as a reliable indicator of collagen content in tissues49.

Finally, to evaluate the physiological structure of the lung tissue, histopathological analysis via hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining was performed. H&E staining revealed that the treatment using TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED mitigated the severity of BLM-induced fibrosis, preserving lung epithelial structures compared to co-extrusion, sonication, and control groups (Fig. 5i). Masson’s trichrome staining, a primary method for observing collagen composition in tissues, revealed a substantial reduction in collagen deposition and parenchymal disruption after the inhalation of TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs (Fig. 5i)50. Quantitative analysis of fibrotic regions in the lungs demonstrated that the PAF-MED group exhibited a greater reduction in fibrosis compared to MSC-cLNPs prepared using conventional, mechanical-based methods (Fig. 5h). Furthermore, pathological examination of major organs in PF mice after inhalation showed relatively good biocompatibility of MSC-cLNPs (Supplementary Fig. S33).

Discussion

Our findings established PAFs as versatile platforms for manipulating nanoparticle trajectories via rational coupling of electric and flow fields. Whereas conventional uniform AFs predominantly enabled nanoparticle separation, we demonstrated that PAF can enhance mixing of heterogeneous particles and achieve efficient nanoscale electrofusion. Compared to conditions without external forces, PAF transformed the stochastic fusion process into directional hybridization, enabling precise control over particle interactions and substantially accelerating the hybridization kinetics51. Multi-physics CFD simulation scheme revealed that optimized PAF imposed periodic dynamic oscillations on LNP trajectories, inducing spatially periodic concentration gradients. The periodic particle distributions originated from oscillatory velocity modulation within the PAF microchannel. This oscillatory velocity modulation functioned like a nanoscopic integrator to amplify local LNP densities, thereby promoting the effective collisions among different types of particles. This trajectory-selective AF modulation offered a designed strategy to precisely modulate the motion of nanoscale lipid systems for enhancing electrofusion. With the design of the PAF configuration, we achieved programmable control over nanoparticle interactions, enabling electrofusion efficiencies exceeding conventional approaches such as sonication and co-extrusion. In addition, building on the PAF simulation framework in this study, tracking the electrofusion process at the single-particle level will provide detailed insights into nanoscale electrofusion dynamics, using advanced techniques such as super-resolution microscopy52, confocal spectroscopy53, and single-molecule electrical devices54. Such microscopic insights will enhance our understanding of the electrofusion mechanism of lipid nanostructures, providing a foundation for the engineering of the PAF electrofusion platform. Collectively, our work provided theoretical and experimental frameworks for enhancing electrofusion between LNPs and CMs driving by PAFs, with implications on applying to diverse nanoscale lipid systems.

Using these strategies, we synthesized PAF-guided, MSC membrane-based cLNPs via a customized microfluidic electrofusion device (MSC-cLNPs), which demonstrated superior targeting capabilities toward injured cells, efficient siRNA delivery, and enhanced therapeutic efficacy compared to conventional counterparts. The enhanced therapeutic performance of MSC-cLNPs prepared by PAF-MED stemmed from their ability to minimize membrane protein degradation and reduce the extracellular misorientation of targeting proteins, key limitations in traditional synthesis methods. The therapeutic efficacy of TGF-β1-siRNA encapsulated MSC-cLNPs was validated in vitro, where they efficiently bound to injured LECs and achieved TGF-β1 silencing, as well as in vivo in PF murine models, confirmed through histopathological and collagen analyses. These findings establish PAF-guided electrofusion as a significant advancement in the synthesis of advanced nanomedicines, with broader implications for cell-derived vesicle engineering, where maintaining surface biomarker fidelity was critical for regulating biological function.

Methods

Multiphysics modeling and computationalanalysis of PAF system

The coupled flow-electric field simulations were implemented through a multi-physics coupling framework in COMSOL Multiphysics® (version 6.1). The laminar flow interface within the Microfluidics Module was employed to solve the low-Reynolds-number flow field, while the electrostatics interface from the AC/DC Module was utilized to compute the electric field distribution, thereby establishing the fundamental physical fields. Particle dynamics were modeled using the Fluid Flow Particle Tracing interface, with synchronized coupling of dielectrophoretic force (\({F}_{{DEP}}=2\pi {r}^{3}{\varepsilon }_{m}{{\mathrm{Re}}}[{f}_{{CM}}]\nabla {\left|E\right|}^{2}\)), hydrodynamic drag force (\({F}_{{{{\rm{Drag}}}}}=6\pi \mu r\left({u}_{f}-{u}_{p}\right)\)), and Coulomb force (\({F}_{{{{\rm{Coulomb}}}}}={qE}\)) into the particle motion equations. The simulation configured uniform particle release at the inlet boundary (release frequency: 3.33 × 104 s⁻¹), no-slip boundary conditions at channel walls, and three-level mesh refinement to ensure grid independence (deviation < 1% for velocity and electric potential), with calculations finalized using the MUMPS solver at a relative tolerance of 0.001.

For post-processing, particle trajectories were analyzed by exporting the x-axis positional coordinates. Frequency distribution histograms were constructed in OriginPro 2022 using a fixed bin width of 12.5 μm to standardize particle counting. Concentration fluctuation characteristics were extracted via nonlinear least-squares fitting, employing the SineSqr model (\(y={y}_{0}+A{\sin }^{2}\left(\pi \frac{x-{xc}}{w}\right)\)) to quantify the amplitude A (corresponding to the Δc* parameter).

Fabrication of PAF-MED

The glass slides were cleaned by sonication in acetone, ethanol and deionized (DI) water. AZ-5214E photo resist (Merck, Germany) was spin coated over the slides, which were then baked at 110 °C for 3 min. After ultraviolet (UV) lithography, the slides were developed to form the electrode pattern. Thermal vapor deposition was used to deposit a thin bilayer film of Cr (5 nm)/Au (80 nm). After evaporation, the photoresist was lifted off in acetone to obtain the electrode arrays. The slides with electrode arrays were then cleaned with acetone and sealed in a clean container for later use.

The silicon wafer was cleaned by sonication in acetone, ethanol and DI water. SU-8 2050 (Microchem, USA) was then spin-coated over the silicon wafer at 1500 rpm for 30 s, and thermally cured successively at 65 °C for 10 min, and 95 °C for 30 min. After UV lithography, the silicon wafer after photolithography was transferred onto a hot plate at 65 °C for 10 min, and 95 °C for 30 min successively. After development for 15 min, the wafer was rinsed with isopropanol and DI water, and blown dry. After hardbake at 180 °C and natural cooling, the SU-8 molds were obtained. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) precursor (SYLGARD™ 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit, Dow, USA) with a 10:1 ratio was poured onto the SU-8 molds. After debubbling in a vacuum oven, the precursor with SU-8 molds was cured for 40 min at 100 °C. The PDMS membranes with microchannels were then released after sonication in ethanol.

After sonicated in ethanol and dried with air gun, PDMS membranes and electrode slides were then treated with oxygen plasma for 30 s at 100 W. The PDMS membrane was then aligned and bonded with the electrode substrate. The devices were then baked at 90 °C for 120 min and cool down over night for irreversible bonding.

Characterizations of PAF-MED

Optical micrographs of the MED were captured using an optical microscope (MJ31, MShot, China). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging was performed on a Regulus 1800, Hitachi, Japan.

Surface topography measurements of PAF-MED

The surface topography of microfluidic channels and electrodes was characterized using a Bruker DektakXT Stylus Profilometer. A 2-μm stylus tip and a scanning length of 10 mm were set after auto calibration. Measurement ranges were set to 6.5 μm for MEAs and 650 μm for microchannels, respectively, with a stylus force of 1 mg and a sampling frequency of 1 mm/100 s. Triplicate measurements were performed for each structural feature to ensure reproducibility.

Simulation of fluid Velocity Distribution and Electrical Field Distribution

The maximum fluid speed within the micro-tube was less than 0.5 m·s−1. The Reynolds number (Re) for this system can be calculated using the general formula:

where \(\rho\) is the dynamic density of liquid, u is the average velocity of fluid, L is characteristic length, and \(\mu\) is viscosity of fluid. Given that the cross-section of the micro-tube was rectangular, the characteristic length was determined by:

where a is the width of the pipe cross-section and b is the height of the pipe cross-section. Using these relationships, the maximum Reynolds number was calculated to be less than 2000, indicating that the fluid flow is laminar. Consequently, the Navier-Stokes equations can be applied to describe the flow:

where P represents the fluid pressure.

The signal source applied to the electrodes operated at a maximum frequency of 25 kHz. This frequency was sufficiently low, ensuring that the wavelength of the corresponding electromagnetic wave was much larger than the distance between the electrode gaps. As a result, a quasi-static electrical analysis was appropriate, governed by:

where V is the electrical potential, and σ is the electrical conductivity of liquid.

All 3D models and simulations were performed using COMSOL Multiphysics® (version 6.1). The physical model integrates two key modules: the Laminar Flow interface and the Electric Currents interface. The Laminar Flow interface was utilized to simulate parameters such as velocity, pressure, and the Reynolds number, providing insights into the flow state within the micro-tube. The Electric Currents module was employed to simulate the electric field, potential voltage, current density, and power distribution.

A “Tetrahedral Mesh” technique was used for meshing the 3D models, which involves subdividing the objects into tetrahedral elements within the three-dimensional space. This type of meshing provides a robust framework for detailed analysis of both fluid dynamics and electrical properties in the microfluidic system.

Materials

NaCl, NaHCO3, KCl, Na2HPO3, MgCl2, HEPES and EDTA (AR, Aladdin, China). RPMI 1640 medium (Gbico, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Premium Plus, Gbico, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). BLM (Orileaf, China). DiO, DiD (Beyotime, China). DOTAP, DOPE, DOPC, DSPE, Lin-MC3-DMA and Cholesterol (Sinopeg, China). NBD-PE and Rho-PE (Merk, Germany).

Cell culture

TC-1 cells (CAT. BFN60805941), mouse LEC line, were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI 1640) medium with 10% FBS and passed every two days. For BLM induced injured TC-1 cells, BLM (20 μg·mL−1) was added into the culture medium of logarithmic growth period TC-1 cells to obtain injured LCEs cell models. TC-1 cells were generated of primary lung epithelial cells from C57BL/6 mice, serving as a stable murine pulmonary epithelial model for in vitro studies.

Animals

C57BL/6 mice and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from the Animal Center, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Male C57BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks were used for the in vivo experiment. All mice were kept in an SPF environment. All animals in the experiment were raised in Zhejiang University and proved by ZJU-Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Review Committee with the animal ethics code (ZJU20240703).

The housing of 57BL/6 mice is conducted within a stringent barrier facility of ZJU-laboratory center, a critical prerequisite for ensuring the integrity and reproducibility of biomedical research. This controlled environment is designed to permanently exclude adventitious pathogens. All incoming air is HEPA-filtered, and the facility is maintained under positive pressure with strict regulation of temperature (20–26 °C) and humidity (40–70%). All materials, including feed, bedding, and cages, are introduced into the barrier via a double-door autoclave or pass-through dunk tanks after rigorous sterilization. Access is permitted only to authorized personnel following a mandatory shower and change into sterilized protective apparel. Within the facility, animals are typically housed in Individually Ventilated Cages (IVCs), which provide an additional level of containment to prevent cross-contamination. Comprehensive biosecurity protocols, including the use of sentinel animals for regular health monitoring, are rigorously enforced to verify the ongoing SPF status of the colony. This integrated system of physical barriers, standardized environmental conditions, and meticulous operational procedures collectively safeguards the health and genetic stability of the animals.

Ethics

Every experiment involving animals, human participants, or clinical samples have been carried out following a protocol approved by an ethical commission.

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) culture

Bone marrow MSCs were harvested from the femurs and tibias of euthanized SD rats (aged 4 weeks) according to the reported methods[23]. Briefly, both ends of the femurs and tibias were excised after isolation, and the marrow was flushed out using complete culture medium consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The flushed cell suspension was centrifuged at 400 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in fresh complete medium. The isolated MSCs were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and passed every two days.

Red blood cell (RBC) isolation

C57BL/6 mice (aged 8 weeks) were obtained from the Animal Center, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Orbital blood was collected from the mice and transferred into a 50 mL centrifuge tube containing 10 mL of whole blood. The blood was diluted with 10 mL of PBS and gently mixed. Two 15 mL centrifuge tubes were prepared, each containing 5 mL of Ficoll solution. The diluted blood was carefully layered on top of the Ficoll in each tube and centrifuged at 450 × g for 20 min. RBCs were collected from the bottom layer.

Macrophage isolation

C57BL/6 mice (aged 8 weeks) were euthanized. The tibia and femur of the mouse were isolated and removed under sterile conditions. Cut both ends of the tibia and femur, and then use a 1 mL syringe to draw complete culture medium. Wash the bone marrow cells from one end of the bone into a 50 mL sterile centrifuge tube. Repeat twice until the bones turn white. Add 5 times the volume of red blood cell lysis solution to the 50 mL centrifuge tube, pipe repeatedly with a Pasteur pipette, and let stand for 15 min. After standing, centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 min and discard the supernatant. Add an appropriate amount of RPMI 1640 medium to resuspend the cells, and then filter the cells through a 200-mesh filter. Centrifuge at 300 g for 10 min, discard the supernatant, and repeat twice. Following the RBC lysis step, cells were resuspended in 1640 cell culture medium and filtered through a 200-mesh filter. The cells were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant discarded. This step was repeated twice. The cells were resuspended in 1640 complete medium supplemented with 10 ng·mL−1 M-CSF (PeproTech, Cat. 315-02-50) and cultured for one week to induce differentiation into macrophages.

Neutrophil isolation

C57BL/6 mice (aged 8 weeks) were euthanized and processed as described for macrophage isolation. The bone marrow cell suspension was passed through a 200-mesh cell strainer and transferred to a 15 mL centrifuge tube. The suspension was centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in RBC lysis solution. After a 1–2 min incubation, the cells were centrifuged again at 400 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Neutrophils were isolated using discontinuous density gradient centrifugation with Percoll. The cell suspension was layered over Percoll gradients (78%, 65%, and 55%) and centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 min at 25 °C. The neutrophil layer was aspirated, washed with cold PBS, and centrifuged at 400 × g for 3 min at 4 °C to remove excess Percoll. Neutrophils were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium.

Cell membrane isolation and preparation

Purified MSCs, RBCs, macrophages, and neutrophils were subjected to freeze-thaw cycles (three times between − 80 °C and 37 °C) and homogenized on ice using a handheld Dounce homogenizer (20 passes) to remove nuclei and other organelles. Cell membranes were resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 75 mM NaCl, 6 mM NaHCO3, 1.5 mM KCl, 0.17 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors. The suspension was centrifuged at 3200 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 211,000 × g for 30 min to collect cell membranes, which were resuspended and stored in distilled water at 4 °C.

For the DiO staining of the cell membrane, the concentration of purified cells was adjusted to 1 × 106·mL−1. The DiO dye was added into the solution at concentration of 0.05 μmol·mL−1 and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The DiO-labeled cells were collected by centrifugation at 1200 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. And the DiO-labeled cell membranes were obtained just as mentioned above.

Preparation of MSC-cLNPs by Co-extrusion and Sonication Methods

The protein content of the obtained cell membranes was quantified using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Cat. P0010). To prepare the lipid component, DOTAP (or DOPG, or DOPC):DSPC:CHOE:DOPE (molar ratio 40:40:10:10, total concentration of 1 μmol·mL−1) were dissolved in ethanol, followed by spin-drying the ethanol under negative pressure at 35 °C and 120 rpm to form a thin film. This thin film was then hydrated with PBS buffer containing the cell membrane suspension. The purified MSC membrane suspension was sonicated in a capped glass vial for 2 min (2 s on and 3 s off as a cycle) using a probe sonicator at a power of 60 W. The ratio of lipid formulation mass to total MSC membrane protein mass was adjusted to 1:0.5 according to previous literature33.

Co-extrusion method

An LNP emulsion was first prepared using a rotary evaporation apparatus. The cell membrane suspension was then added to the LNP emulsion, and the mixture was placed into a handheld extruder (Avanti Mini, Avanti, Germany). The LNP-MSC membrane mixture was co-extruded through polycarbonate film with apertures of 0.2 μm for 20 cycles. The resulting product was collected and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 4 °C and 150,000 g for 3 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate, which contained the MSC-cLNPs, was collected.

Sonication method

An LNP emulsion was prepared using a rotary evaporation apparatus, similar to the co-extrusion method. The cell membrane suspension was added to the LNP emulsion, and the mixture was placed into an ultrasonic disruptor (SCIENTZ-IID, SCIENTZ, China) under an ice bath. Fusion of the MSC membrane and LNPs was achieved through ultrasonic cavitation using a probe sonicator (60 W) for 3 min (2 s on and 3 s off as a cycle) and operated twice. The mixture was then subjected to ultracentrifugation at 4 °C and 150,000 × g for 3 h. The supernatant was removed, and the resulting precipitate, containing the MSC-cLNPs, was collected.

For other cell membranes, hybrid LNPs preparation, replacing the MSC membranes with cell membranes including macrophages, red blood cells, neutrophils, TC-1, and Caco-2, is sufficient.

Preparation of MSC-cLNPs by PAF-MED

To prepare the MSC-cLNPs, DOTAP (or DOPG, or DOPC):DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE (molar ratio 40:40:10:10, total concentration of 1 μmol·mL−1) were dissolved in 4 mL of ethanol. The lipid formulation ethanol solution, sodium citrate buffer solution, and cell membrane-sodium phosphate buffer solution were then transferred to a micro-injection pump. Using injection tubing, the phospholipid ethanol solution was introduced into port 2 of the first microfluidic channel (Fig. 2a). The nucleic acid-sodium citrate buffer solution was simultaneously introduced into the first channel through ports 1 and 3, while the cell membrane-sodium phosphate buffer solution was introduced into port 4 of the second channel.

The flow rate of the nucleic acid-sodium citrate aqueous solution was adjusted to 700 μL·min−1. The flow rate ratio of the nucleic acid-sodium citrate aqueous solution (aqueous phase) to the lipid formulation ethanol solution (organic phase) was set to 7.5:1 (93.33 μL·min−1). Concurrently, the flow rate of the 0.5 mg·mL−1 (total cell membrane protein concentration measured by BCA kit) MSC membrane sodium phosphate solution was adjusted to 46.67 μL·min−1 for each group. A pulse wave was selected, and the AC voltage was set to 10 V with a frequency of 12.5 kHz.

The resulting solution containing MSC-cLNPs was collected at outlet 5. The organic solvent was then removed using a vacuum drying chamber. The resulting product was collected and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 4 °C and 150,000 × g for 3 h.

For other cell membranes, hybrid LNPs preparation, replacing the MSC membranes with cell membranes including macrophages, red blood cells, neutrophils, TC-1, and Caco-2, is sufficient.

Characterization of MSC-cLNPs

The average particle size, zeta potential, and PDI of MSC-cLNPs were analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS, Mastersizer 2000, Malvern, UK) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA, Nanosight NS500, Malvern, UK) measurements. The morphological characteristics of MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods were measured by projective electron microscopy (Talos F200C 200 kv, and G2 Spirite 120 kv, FEI Technai, USA). CD (J-1500-150ST, JASCO, Japan) was utilized for cell membrane protein structure detection.

Preparation of different charged MSC-cLNPs

DOTAP (or DOPG, or DOPC):DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE (molar ratio 40:40:10:10, total concentration of 1 μmol·mL−1) were weighed and dissolved separately in 2 mL of ethanol. The cLNPs were then prepared using the different methods, including the PAF-MED, co-extrusion, and sonication, following the respective protocols for each method.

Preparation of DiD-labeled MSC-cLNPs

For the co-extrusion and sonication methods, the 1,1’-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-Tetramethylindodicarbocyanine, 4-Chlorobenzenesulfonate Salt (DiD) dye was solved in lipid formulation ethanol solution. Then, the thin film dispersion method was adopted for DiD dye loading. 0.05 μmol·mL−1 of DiD dye was loaded by 1 μM·mL−1 of lipid formulation ethanol solution, and the thin film was prepared by rotary evaporating the solvent at 35 °C, 120 rpm. The suspension containing cell membranes was added and hydrated, and adjust the ratio of lipid formulation mass to cell membrane protein mass to 1:0.5. The mixture was operated by co-extrusion and sonication as mentioned above to obtain MSC-cLNPs.

For PAF-MED preparation, DiD dye was solved in the lipid formulation ethanol solution at 0.05 μmol·mL−1. Then, the DiD-labeled MSC-cLNPs were prepared by PAF-MED as mentioned above.

FRET Detection

The DOPE-conjugated FRET probes, NBD-PE and Rho-PE, were formulated into the LNPs. After mixing DOTAP (or DOPG, or DOPC):DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE:NBD-PE:Rho-PE (molar ratio 40:40:9:9:1:1, total concentration of 1 μM·mL−1) in ethanol, the LNPs were prepared by MED without CM inlet. The MSC-cLNPs were prepared as LNPs by PAF-MED with CMs inlet as previously described. Fluorescence measurements (F) were conducted on a microplate reader at Ex/Em = 465/520 nm using SpectraMax ID3, Molecular Devices, USA. Only bare LNPs in PBS were set as negative control (Fmin). Lipids containing probes incubated with Triton X-100 solutions (2 wt.%) were set as a positive control (Fmax). The lipid fusion (%) was calculated as (F − Fmin)/(Fmax − Fmin) × 100%.

Dot blotting

Dot blotting was performed to verify the orientation of cell membranes on the cLNPs. The number of cLNPs was quantified using NTA, and cLNPs were loaded onto a nitrocellulose (NC) membrane at a total number of 2 × 105. cLNPs prepared by different methods were blotted onto the NC membrane and then air-dried to ensure complete adsorption and immobilization of proteins onto the membrane.

After air-drying, the membrane was blocked using a 5% skim milk solution in 0.05% PBST. For primary antibody binding, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies targeting extracellular CD44 (Boster, Cat. A00052, China), VLA-4 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. 34971T, USA), CD47 (Boster, Cat. A00360-1, China), and CXCR4 (Boster, Cat. PA1237, China) at a dilution ratio of 1:1000. Following primary antibody incubation, the membranes were exposed to horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H + L), Elabscience, Cat. E-AB-1003, at a dilution ratio of 1:5000). Chemiluminescence detection was then conducted to identify the binding of extracellular CD44, VLA-4, CD47, and CXCR4.

siRNA Encapsulation

To prepare the lipid formulation ethanol solution, D-Lin-MC3-DMA:DOTAP:DSPC:cholesterol:DOPE (molar ratio 30:20:30:10:10, total concentration of 1 μmol·mL−1) were dissolved in 2 mL of ethanol. TGF-β1-siRNA (5’-3’ GAACCAAGGAGACGGAAUATT, 3’-5’ UAUUCCGUCUCCUUGGUUCTT, Genepharma, China) was dissolved in a sodium citrate buffer solution at a concentration of 0.233 μmol·mL−1.

For the co-extrusion and sonication methods, 1 mL of the lipid formulation ethanol solution was spin-dried under negative pressure at 35 °C and 120 rpm to form a thin film. The film was then hydrated with the siRNA sodium citrate solution at a weight ratio of 1:10 (siRNA/cLNPs) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The suspension containing cell membranes was added, adjusting the ratio of phospholipid mass to cell membrane protein mass to 1:0.5. The resulting mixture was processed using the co-extrusion and sonication methods, as described in Preparation of MSC-cLNPs by Co-extrusion and Sonication Methods, to obtain siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs.

For the PAF-MED preparation, the lipid formulation ethanol solution was injected through inlet #2, while the siRNA sodium citrate solution was injected through inlets #1 and #3. The weight ratio of siRNA to cLNPs was maintained at 1:10. The flow rate of the nucleic acid-sodium citrate aqueous solution was set to 700 μL·min−1 for each condition. The flow rate ratio of the nucleic acid-sodium citrate aqueous solution (aqueous phase) to the phospholipid-ethanol solution (organic phase) was adjusted to 7.5:1 as 93.33 μL·min−1. Simultaneously, the flow rate of the 0.5 mg·mL−1 MSC membrane sodium phosphate solution was adjusted to be 46.67 μL·min−1 for each group. A pulse wave was applied with an alternating current voltage of 10 V at a frequency of 12.5 kHz. The solution containing MSC-cLNPs was collected at outlet 5, and the organic solvent was subsequently removed using a vacuum.

Encapsulation efficiency determination

The encapsulation efficiency was determined using the Quant-iTTM RiboGreen® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, siRNA-loaded cLNPs were prepared and nebulized according to the established method. A 3 μL aliquot of the cLNP solution was mixed with 117 μL of either 1 × Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer or 2% Triton X-100 and vortexed for 2 min. Free siRNA standards were prepared at a series of concentrations. NP samples and siRNA standards were then incubated with an equal volume of RiboGreen reagent, diluted 1:200, for 5 min. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader set at excitation/emission wavelengths of 480/520 nm (Tecan, Switzerland). The encapsulation efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

Encapsulation Efficiency (%) = (Total siRNA−Free siRNA)/ Total siRNA × 100%

In vitro LECs uptake

TC-1 cells were seeded into 6‑well plates (Corning, USA) at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight in a cell culture incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ to allow for attachment. To simulate an injured LECs model, TC-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were treated with BLM (20 μg·mL−1) for 24 h to induce cellular injury. MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods were labeled with DiD dye. The DiD labeled MSC-cLNPs (with DiD dose of 0.01 μmol·mL−1) were then incubated with both healthy and BLM-injured mouse LECs (TC-1) for 6 h. After incubation, the fluorescence intensity of DiD within the TC-1 cells was measured using flow cytometry to assess cellular uptake.

In vitro silencing efficiency of TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs

The TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated MSC-cLNPs prepared by different methods were sterilized using 0.22 μm sterile filter membranes. TC-1 cells were seeded into 6‑well plates (Corning, USA) at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight in a cell culture incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ to allow for attachment. To simulate an injured LECs model, TC-1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were treated with BLM (20 μg·mL−1) for 24 h to induce cellular injury. To assess their therapeutic effect, BLM-injured TC-1 cells were first replaced with a serum-free culture medium. The sterilized TGF-β1-siRNA-encapsulated cLNPs (with TGF-β1-siRNA dosage of 0.01 μmol·mL−1) were then added to the cell culture. After incubating at 37 °C for 6 h, the medium was discarded and replaced with a complete culture medium, followed by an additional 24 h incubation.

Subsequently, the cells were lysed on ice using RIPA lysis buffer and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected for analysis. The TGF-β1 content in the supernatant was quantified using an ELISA kit (Mouse TGF-β1 ELISA Kit, EK0515, Boster, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay was used to evaluate the efficiency of TGF-β1 knockdown by the different MSC-cLNP formulations.

BLM induced PF modeling

The mice PF model was prepared by the classical way of BLM challenge. In short, C57BL/6 male mice, aged 8 weeks, were intratracheally instilled with BLM (0.8 mg·kg−1) to induce PF modeling.

In vivo distribution of MSC-cLNPs

48 h post-BLM challenge, inhalable administration was performed via nebulization using a small animal handheld nebulizer (Yuyan Instruments Co.Ltd, China). Each mouse inhaled 50 μL of the nebulized solution (with DiD dose of 40 μM·kg−1). At 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post-administration, major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were harvested, and their fluorescence contents were observed and semi-quantitatively analyzed.

In vivo immunofluorescence staining of MSC-cLNPs

To detect the LECs targeting ability of MSC-cLNPs in vivo, frozen slices of lungs from PF mice were used for immunofluorescence staining. E-cad antibody (Proteintech, 20874-1-AP, China) was diluted at 1:1000. The second antibody was FITC- labeled fluorescent secondary antibody. The nuclei were stained with DAPI and diluted at 1:1000. After staining, utilizing confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM-800, Carzeiss, Germany) for observation.

In vivo TGF-β1-siRNA delivery and PF intervention

On days 1, 4, and 7 post the BLM challenge, TGF-β1-siRNA-loaded MSC-cLNPs (with TGF-β1-siRNA dosage of 0.5 mg·kg−1) prepared by various methods were administered via handheld nebulization. On day 21 post-BLM challenge, all the mice were scarified and major organs, including heart, lung, liver, spleen and kidneys were separated.

Evaluation of TGF-β1 level and MMP-9 expression content in lungs

The separated lung tissue was weighed, and an appropriate amount of PBS buffer was added at a ratio of 1:0.5 (lung tissue to PBS buffer). The tissue was then homogenized using a tissue grinder (JXFSTPR, Jingxin, China). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for further analysis.

The concentrations of TGF-β1 and MMP9 in the supernatant were quantified using specific ELISA kits: Mouse TGF-β1 ELISA Kit (EK0515, Boster, China) and Mouse MMP9 ELISA Kit (EK0466, Boster, China), following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Evaluation of hydroxyproline content in lungs

The hydroxyproline content in mouse lung tissues was quantified using an alkaline hydrolysis kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, lung tissue samples (30 to 100 mg) were precisely weighed and hydrolyzed in an alkaline solution at 100 °C for 20 min. The hydrolysate was then adjusted to a pH range of 6.0 to 6.8, treated with activated charcoal, and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was incubated with detection reagents at 60 °C for 15 min. Hydroxyproline content was determined by measuring the absorbance at 550 nm using SpectraMax ID3, Molecular Devices, USA.

H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining

After mice were sacrificed, tibia and femur were taken for decalcification treatment, followed by tissue sections and H&E staining. The detailed operation is carried out by Wuhan PINUOFEI Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Sections were photographed using an inverted microscope. The calculations of fibrotic ratios according to Masson’s trichrome staining were performed by using ImageJ (ij152).

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted using Origin software (version 2019b and 2022) and are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance of P-values was calculated via an unpaired Student’s t test and listed in the figures. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to systematically evaluate intergroup differences across multiple experimental conditions, establishing statistically significant between-group variations at P = 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data underpinning the conclusions of this study are provided within the manuscript, the supplementary materials, and the associated source data. Any additional requests for information can be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the corresponding authors. All additional data not contained within the aforementioned manuscript, supplementary materials, and associated source data has been archived in the permanent repository Figshare, and can be accessed via the direct link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29433020. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Choi, S. E., Khoo, H. & Hur, S. C. Recent advances in microscale eectroporation. Chem. Rev. 122, 11247–11286 (2022).

Skelley, A. M., Kirak, O., Suh, H., Jaenisch, R. & Voldman, J. Microfluidic control of cell pairing and fusion. Nat. Methods 6, 147–152 (2009).

Geboers, B. et al. High-voltage electrical pulses in oncology: irreversible electroporation, electrochemotherapy, gene electrotransfer, electrofusion, and electroimmunotherapy. Radiology 295, 254–272 (2020).

Kandušer, M. & Ušaj, M. Cell electrofusion: past and future perspectives for antibody production and cancer cell vaccines. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 11, 1885–1898 (2014).

Danilushkina, A. A., Emene, C. C., Barlev, N. A. & Gomzikova, M. O. Strategies for engineering of extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 13247 (2023).

Ke, Q. et al. Electrofusion by a bipolar pulsed electric field: Increased cell fusion efficiency for monoclonal antibody production. Bioelectrochemistry 127, 171–179 (2019).

Rols, M.-P. & Teissié, J. Electropermeabilization of mammalian cells to macromolecules: control by pulse duration. Biophys. J. 75, 1415–1423 (1998).

Duckert, B., Lambrechts, D., Braeken, D., Lagae, L. & Fauvart, M. Optimizing mRNA transfection on a high-definition electroporation microelectrode array results in 98% efficiency and multiplexed gene delivery. Biosens. Bioelectron. 241, 115634 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Irreversible electroporation reverses resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 10, 899 (2019).

Banerjee, T. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of membrane surface charge regulates cell polarity and migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 24, 1499–1515 (2022).

Cheng, C. et al. Gremlin1 is a therapeutically targetable FGFR1 ligand that regulates lineage plasticity and castration resistance in prostate cancer. Nat. Cancer 3, 565–580 (2022).

Uspal, W. E., Burak Eral, H. & Doyle, P. S. Engineering particle trajectories in microfluidic flows using particle shape. Nat. Commun. 4, 2666 (2013).

Yang, H., Xu, Y. & Knowles, T. Droplet dynamics in asymmetric microfluidic junctions. Eur. J. Mech. - B/Fluids 102, 118–134 (2023).

Sanchez-Cachero, A. et al. Electrical asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation: Fundamentals, evolution, applications, and prospects. J. Chromatogr. A 1739, 465522 (2025).

Kochetkov, K. A., Bystrova, N. A., Pavlov, P. A., Oshchepkov, M. S. & Oshchepkov, A. S. Microfluidic asymmetrical synthesis and chiral analysis. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 115, 62–91 (2022).

Xie, F. et al. Asymmetric local electric field induced by dual heteroatoms on copper boosts efficient CO(2) reduction over ultrawide potential window. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202407661 (2024).

Ma, F., Wang, S., Wu, D. T. & Wu, N. Electric-field–induced assembly and propulsion of chiral colloidal clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6307–6312 (2015).

Yang, D. et al. An asymmetric AC electric field of triboelectric nanogenerator for efficient water/oil emulsion separation. Nano Energy 90, 106641 (2021).

Zhang, H. & Lyden, D. Asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation technology for exomere and small extracellular vesicle separation and characterization. Nat. Protoc. 14, 1027–1053 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Multiomics analysis of naturally efficacious lipid nanoparticle coronas reveals high-density lipoprotein is necessary for their function. Nat. Commun. 14, 4007 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Exosome detection via the ultrafast-isolation system: EXODUS. Nat. Methods 18, 212–218 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Tumour extracellular vesicles and particles induce liver metabolic dysfunction. Nature 618, 374–382 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Engineering stem cell derived biomimetic vesicles for versatility and effective targeted delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202006169 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. Hybrid stem cell-derived bioresponsive vesicles for effective inflamed blood-brain barrier targeting delivery. Nano Today 49, 101800 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell membrane-coated vesicles for bone marrow-targeted leukaemia drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 15, 5689 (2024).

Iranshahi, K., Defraeye, T., Rossi, R. M. & Müller, U. C. Electrohydrodynamics and its applications: Recent advances and future perspectives. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 232, 125895 (2024).

Chibowski, E. & Szcześ, A. Zeta potential and surface charge of DPPC and DOPC liposomes in the presence of PLC enzyme. Adsorption 22, 755–765 (2016).

Maeki, M., Uno, S., Niwa, A., Okada, Y. & Tokeshi, M. Microfluidic technologies and devices for lipid nanoparticle-based RNA delivery. J. Contr. Release 344, 80–96 (2022).

Kou, J., Shen, J., Wang, Z. & Yu, W. Advances in hybridoma preparation using electrofusion technology. Biotechnol. J. 18, e2200428 (2023).

Su, Y. et al. High Targeting Specificity toward Pulmonary Inflammation Using Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Hybrid Nanovehicle for an Efficient Inflammation Intervention. Adv. Health. Mater. 12, e2300376 (2023).

Huang, T. et al. Efficient intervention for pulmonary fibrosis via mitochondrial transfer promoted by mitochondrial biogenesis. Nat. Commun. 14, 5781 (2023).

Huang, T. et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles augment the intercellular mitochondrial transfer-mediated therapy. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj0534 (2021).

Groß, R. et al. Phosphatidylserine-exposing extracellular vesicles in body fluids are an innate defence against apoptotic mimicry viral pathogens. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 905–921 (2024).

Ho, N. T. et al. Membrane fusion and drug delivery with carbon nanotube porins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016974118 (2021).