Abstract

Bionic hands can replicate many movements of the human hand, but our ability to intuitively control these bionic hands is limited. Humans’ manual dexterity is partly due to control loops driven by sensory feedback. Here, we describe the integration of proximity and pressure sensors into a commercial prosthesis to enable autonomous grasping and show that continuously sharing control between the autonomous hand and the user improves dexterity and user experience. Artificial intelligence moved each finger to the point of contact while the user controlled the grasp with surface electromyography. A bioinspired dynamically weighted sum merged machine and user intent. Shared control resulted in greater grip security, greater grip precision, and less cognitive burden. Demonstrations include intact and amputee participants using the modified prosthesis to perform real-world tasks with different grip patterns. Thus, granting some autonomy to bionic hands presents a translatable and generalizable approach towards more dexterous and intuitive control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Commercially available bionic hands can now replicate many movements and grip patterns of our innate biological hands1,2,3. However, controlling a multiarticulate bionic hand is not an easy or intuitive task; individuals with hand amputation abandon these commercially available bionic hands at an alarming rate4,5, often citing poor control6,7 and cognitive burden8,9 as primary reasons.

Most commercial prostheses are controlled using pattern recognition or dual-site control that requires the user to select among predetermined grip patterns, often with a fixed force output. In contrast, our native hands are capable of seamlessly transitioning between numerous grip patterns and generating a wide range of forces uniquely tailored to individual objects. This dexterity is made possible by an intricate neural encoding of hand control in terms of joint position10,11,12. Ideally, prosthesis users could similarly control the individual position of each prosthetic digit to generate any arbitrary grasp and exert any desired force. However, simultaneous and proportional control of multiple degrees of freedom is difficult to achieve; as the number of degrees of freedom increases, errors compound, cognitive burden grows, and task performance decreases13,14.

How, then, does the brain fluidly control the human hand, which features over 20 biomechanical degrees of freedom15,16? One approach taken by the human nervous system is to simplify higher-level control by reducing the dimensionality of the movements on a task-by-task basis12,17,18,19. Another approach is to utilize cutaneous feedback to automate lower-level grasping capabilities like the slip-detection reflex20,21,22,23,24,25. These biological tactics rely on multimodal sensory feedback from the environment – visual and somatosensory.

To this end, one biomimetic approach to make bionic arms more dexterous and intuitive would be to leverage multimodal sensors to aid with some aspects of manual dexterity, thereby offloading some of the cognitive demand to the bionic arm itself. Indeed, researchers have used optical sensors to preposition robotic hands26,27,28,29, force sensors to guide force output30,31, and even acoustic sensors to detect and prevent slip31. These prior works demonstrate that even a single sensing modality can improve functional outcomes on specific tasks in controlled environments. However, among all of these works, there is a distinct lack of testing with users performing real-world tasks with physical prostheses. Additionally, the algorithms used to leverage multimodal sensor data to offload aspects of dexterity are often task-specific and unable to generalize to the diversity of objects and grasps seen in the real world.

One common approach is to develop a semi-autonomous prosthesis where control switches between the human user and an autonomous machine controller. For example, Zhuang et al. developed an autonomous machine controller that moved the individual fingers of a virtual prosthesis to maximize finger contact with virtual objects30. The human user controlled the prosthesis with surface electromyography (EMG) to initiate initial contact with the object, at which point the autonomous controller would take over and move the digits autonomously to create a multidigit grasp with a fixed force output. Although this approach was shown to improve grip stability and functional performance, it results in a single fixed force being applied to all objects, making it unlikely to generalize to broader activities of daily living. Indeed, Zhuang et al. noted this limitation and hypothesized that continuously sharing control between the human and machine, rather than toggling, would improve functionality and make the control more intuitive for the user30.

To this end, another common approach to share control between a human and a machine is to blend the human control and the machine control using a simple linear coefficient, β. Under this approach, the prosthesis position is determined by human control multiplied by β plus the machine control multiplied by (1-β). For example, Dantas et al. used this approach with a virtual prosthesis to demonstrate improved control on a virtual target touching task32. However, this approach requires the machine to be able to consistently provide a meaningful goal, not just under controlled conditions when triggered by the user. Indeed, Dantas et al. punted this issue by simply setting the machine goal equal to the location of the virtual target. It remains an open question as to how an autonomous machine could use real-world sensors to provide a meaningful control signal to users at all times across a range of tasks.

Here, we build on these past works by incorporating multimodal sensors, capable of detecting both proximity and pressure, into the fingertips of a commercial prosthetic hand for generalizable and translational use. We also establish a new autonomous closed-loop machine controller for the physical prosthesis to enhance grasping precision and stability. Importantly, to support generalizability, we introduce a novel shared control framework that continuously blends human and machine intent throughout the grasp, such that the human remains in control at all times while still receiving subtle assistance from the machine. In stark contrast to prior works, we show that this shared control framework allows the machine to assist the user with a variety of real-world tasks and grasps that demand unique positions and force contributions from each digit. Importantly, as a further demonstration of generalizability and translational potential, we demonstrate greater grip precision, improved grip security, and reduced cognitive burden through a series of experiments with multiple intact-limb participants and four transradial amputees using a physical prosthesis. These results serve as proof-of-concept that sharing control between the user and an autonomous machine can provide immediate functional benefits while decreasing the cognitive cost of using a prosthetic hand. As such, this work constitutes an important step towards more intuitive and dexterous control of multiarticulate bionic arms and has broad implications for prosthetic and robotic arms.

Results

Multi-modal finger-tip sensors allow for zero-force contact detection

Our innate biological fingertips are innervated by a dense network of sensory afferents that can detect even the gentlest interactions with our environment. Our sense of touch also enables instinctive motor actions that enhance our dexterity. However, given the delay associated with cutaneous reflexes24, our dexterity is not simply due to sensory feedback33. Indeed, our dexterity is also made possible in part due to internal models in the brain that simulate and anticipate hand-object interactions, and that update with experience over time34.

In contrast, most commercial prostheses are not sensorized and cannot provide the user with the feedback necessary for efficient motor planning and learning. To bridge this gap, we developed a multimodal sensor for bionic hands capable of “seeing” and “feeling” objects. We developed a printed circuit board (PCB) in the shape of a fingertip that contained an infrared proximity sensor (VCNL4010, Vishay Semiconductor) and a barometric pressure sensor (MS5637-02BA03, TE Connectivity) (Fig. 1A). We then encased the PCB in silicone in a form factor that mimicked the removable fingertips of a widely used commercial prosthesis (TASKA Hand, TASKA; Fig. 1B). The fingertips of the prosthesis were then replaced with our custom sensors to provide wireless proximity and pressure data from each digit in real-time (Fig. 1C).

A An infrared light sensor and a barometric pressure sensor were embedded into a PCB to measure object proximity and force, respectively. B The PCB was housed within a custom-molded fingertip. C The fingertip was then retrofitted into a commercial prosthetic hand. D The embedded sensors can detect intricate interactions with objects, such as a piece of cotton falling onto the hand. The proximity signal (red) rapidly increases as the cotton falls and approaches the hand. The proximity signal then remains high, indicating contact even though the cotton produces a near-zero force on the hand. As additional force is applied to the cotton, both the pressure signal (blue) and the proximity signal increase as the silicone fingertip deforms. Note that the proximity signal increases before the pressure sensors as increasing force is applied, and the pressure signal continues to increase once the proximity signal has saturated. Images and data updated and adapted from ref. 36.

As an initial test of the sensors, a cotton ball with essentially no weight was dropped onto the fingertip while recording the proximity and pressure readings (Fig. 1D). A sudden rise in the proximity sensor reading corresponded with the cotton falling onto the sensor, validating the ability to detect proximity. The steady-state elevated proximity signal validated the ability to also use proximity as a near-zero force contact signal. Being able to detect near-zero force contact is crucial if one wishes to emulate the precision and dexterity of the intact human hand, as our hand control is based heavily on feedback from highly tuned mechanoreceptors that encode subtle and fast deformations in the skin35. Finally, increasing proximity and pressure data when applying external force to the cotton ball validated the ability to detect external forces on the hand. Further testing demonstrated that the proximity sensor had a range of 0–1.5 cm, and the pressure sensor embedded in the silicon could measure up to 35 N (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, the use of pressure sensors embedded in silicone enable the sensors to detect forces applied in different directions, as opposed to load cells that only accurately measure force in specific directions36.

Machine control grasps objects with minimal force

With our native hands, we are exquisitely proficient at exerting just enough pressure on an object to grasp it37. In contrast, commercial prostheses tend to select among predetermined grasps and flex until reaching a preset position or motor current, regardless of the situation or object being grasped. To address this, we developed an autonomous grasping controller that automatically grasps objects with minimal force using the embedded proximity and pressure sensors as feedback (Fig. 2A). Once an object was detected as being in proximity to a finger, that digit moved toward the object until pressure was detected, at which point the digit would hold its position. To retain control over the bionic hand and ensure participants could still release objects, participants enabled and disabled the autonomous controller by contracting their extrinsic hand flexors or extensors, respectively.

A The machine control algorithm attempted to make contact with the object while minimizing the fingertip pressure. Participants engaged the machine controller by activating their flexors. If the proximity sensor detected an object, then the thumb would flex until contact was detected, at which point the thumb’s position was held constant. Participants could then release the object by activating their extensors. B Three intact-limb participants with no prior myoelectric control experience attempted to move a fragile object over a barrier using human control or machine control. Participants needed to minimize the force exerted on the object to avoid “breaking” it. C With machine control (dashed lines), participants were able to successfully grasp the object without breaking it. Once proximity was detected (red), the hand advanced toward the object to produce a minimal amount of pressure (blue). Participants struggled to grip the object gently when using human control (solid lines), which resulted in sudden contact with the object and an immediate increase in pressure. D Machine control resulted in significantly greater success on the fragile-object task (permutation test; p < 0.001). E The normalized pressure exerted on the thumb sensor was also significantly less for machine control (generalized linear model; p < 0.001). F Participants also reported significantly less subjective workload via the NASA TLX survey when using the machine control (permutation test; p < 0.001). G However, machine control resulted in significantly greater physical effort (generalized linear model; p < 0.001). Violin plots represent the distribution of the data; black bars indicate the median. Data from three intact-limb participants. Sample sizes are: 12 success rates per condition (4 repeated measures per participant); 118 pressure readings for machine control and 119 pressure readings for human control (aggregate of all attempts from all participants); 6 TLX scores (2 repeated measures per participant); and 118 sEMG MAV averages for machine control and 119 sEMG MAV averages for human control (aggregate of all attempts from all participants). ** denotes p < 0.01; *** denotes p < 0.001. All statistical tests are two-sided.

We evaluated the performance of this autonomous “machine” controller against a more traditional myoelectric “human” control strategy on a fragile-object transfer task38,39. This fragile-object task requires an individual to generate enough grip force to pick up and transfer the object, while also minimizing their grip force to avoid “breaking” the object (Fig. 2B). To ensure the human control was capable of producing the variable force necessary to complete the task, the comparative “human” control benchmark was a one degree-of-freedom (DOF), myoelectric proportional controller. To this end, a modified Kalman filter40 was used to regress the kinematic position of the thumb using surface electromyography (sEMG) measured at the forearm using a compression sleeve with embedded electrodes41.

Under machine control, the hand successfully detected the object and moved the fingers to the point of making contact and exerting measurable pressure before stopping (Fig. 2C). Relative to human control, machine control reduced the normalized pressure measured by the sensor embedded in the hand (53 ± 24% vs. 40 ± 13%; p < 0.001; generalized linear model; Fig. 2E), suggesting the machine exerted less force on the object. This is further supported by the fact that, with machine control, participants were more successful at transferring the fragile object over the barrier without breaking (23 ± 21% vs. 99 ± 3%; p < 0.001; permutation test; Fig. 2D).

We also surveyed the participants on the subjective workload required for machine and human control after the fragile-object transfer task using the NASA Task Load Index (TLX)42. As expected, participants reported less subjective workload with machine control (70.70 ± 20.93 vs. 21.15 ± 7.72; p < 0.01; permutation test; Fig. 2F).

Surprisingly, machine control resulted in a greater physical burden to the user, as indicated by greater mean absolute sEMG activation (0.34 ± 0.13 µV vs. 0.62 ± 0.18 µV; p < 0.001; generalized linear model; Fig. 2G). This is likely attributed to the binary sEMG threshold used to toggle the machine control on and off; consistently turning on and off the machine control with distinct muscle contractions during quick transfers requires more energy than proportional control, which uses small muscle activation to produce gentle forces.

From a practical perspective, this experiment demonstrates that multimodal sensors can be embedded into a commercial prosthesis to create a semi-autonomous prosthesis capable of automating dexterous tasks like fragile object manipulation. However, as noted in the introduction and in prior works30, simply toggling between human and machine control limits the user to a single fixed force output determined by the machine. Thus, although this is a compelling proof of concept that a machine can aid in a dexterous task, it is unlikely to generalize to real-world use, where different objects demand different forces. To this end, we next explored how control of a bionic hand could be continuously shared between the human and machine to enable more generalizable control and translatable control.

Control is shared between the user and the autonomous bionic hand

Although the autonomous machine control presented in the previous section outperformed human control, it prevented the user from intentionally modulating their grip force. Similarly, prior work using embedded sensors to minimize grip force provided only one set of target forces for applying pressure on grasped objects30. In contrast, our native hands produce different grip forces for different tasks: heavy and slippery objects are gripped with more force than are light, high-friction ones33. Thus, user-modulated forces are vital to make autonomous control applicable to a wide range of manual activities30.

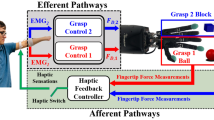

To this end, we developed a novel shared control framework that continuously merges human and machine intent. Our framework is inspired by the intact biological hand’s ability to seamlessly conform to an object, as opposed to prosthesis users who rely on their vision to properly grasp objects43. The shared control framework leverages a machine controller to conform each independent finger to make minimal-force contact with an object (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Video 1) while allowing the human user to modify the grasp about the point of contact by controlling the position of each digit decoded from surface EMG. By continuously sharing control, the human maintains the ability to regulate their grasp while offloading the conformation of the prosthetic hand around a given object to the machine. Importantly, the human user controls each independent digit simultaneously and proportionally, a task which would otherwise be error-prone and cognitively burdensome without machine assistance (Fig. 3A)40,44.

A Proportional position control of multiple digits is difficult to achieve with surface EMG alone, as small changes in the digit’s position (dashed line) can cause rapid changes in the grip force (blue line). B The shared control algorithm continuously combines human (uh) and machine controllers (um) to compute the position (us) for each digit using a dynamically weighted sum. Neither controller is ever completely in control of the hand, as the controllers are continuously shared. Machine control was an MLP that estimated the distance to make contact with an object from proximity data. Human control was the movement about the contact point as decoded from surface EMG. Human control was modified by an exponential function to enhance precision about the contact point. C If no object is detected, the shared control output is based solely on the human control. The box and hashmarks show the range and precision of the human contribution (red) being remapped exponentially to enhance shared control precision. When an object is within proximity, the machine’s contribution (blue) moves the digit to make contact. The human contribution is then remapped to the remaining range of motion, enabling users to make fine adjustments to their grasp. D With shared control, the user extends their grasp as they reach towards the object (0 to 1 s). The machine then moves the digit to the object, and the user attempts to lift the object while making zero-force contact, but is unable (~1 to 2 s). The user then tightens the grasp around the object (~2 to 5 s). It is important to note that the shared control algorithm continuously blends the user’s intent with the autonomous hand, rather than in a sequential manner. E To validate the shared control algorithm, intact limb participants completed fragile-object transfer and holding tasks, and transradial amputee participants completed a fragile-object holding task. F All participants also completed a detection response task (DRT) alongside each primary task, which consisted of pressing a button in response to a randomly timed vibrotactile stimulus.

In contrast to prior works that toggle between human and machine control30, or use a fixed proportion of human and machine control32,45, our shared control framework uses a dynamically weighted sum of human and machine control that is dependent on the relative position of each digit (Fig. 3B). The control of the hand is shared continuously such that neither the machine nor human is entirely in control of the hand and the human’s control becomes more precise as the machine moves to contact smaller objects. For example, when an autonomous digit contacts a small object at 75% of its range of motion, the human’s intent is then remapped to the remaining 25% range of motion, thereby quadrupling the effective precision (Fig. 3C). Since we naturally exert only the minimum amount of force necessary to hold an object securely with our native hands33, we further amplified human precision by mapping human intent exponentially to the remaining kinematic range of motion (Supplementary Fig. 4). Such control is consistent with our endogenous recruitment of motor neurons46. This shared control framework was used for all the following experiments. No parameters were tuned per experiment or object; the same framework was explored across multiple grips and tasks to quantify generalizability and translatability.

To establish a machine controller that can autonomously conform the grasp to objects (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Video 1), we trained a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to estimate the kinematic distance to an object on a digit-by-digit basis using the embedded proximity and pressure sensors (Supplementary Fig. 4). The MLP predicted kinematic distance with high accuracy throughout the entire kinematic range of the sensors. The MLP predictions were then low-pass filtered and added to the current position of each digit to serve as the machine intent such that the machine goal corresponds to the position at which the fingertip would make contact with the observed object (Fig. 3B). Both the proximity sensors and the pressure sensors are used to detect when contact is made, at which point the machine goal is frozen until contact is broken.

Human intent was the output of a modified Kalman filter40 used to regress the kinematic position of each digit using surface EMG41. The Kalman filter has been used extensively to proportionally control prosthetic hands with multiple independent DOFs40,47, but control becomes jittery, error-prone, and cognitively burdensome when controlling multiple DOFs simultaneously14,44. The resultant shared control allows for quick and precise position control of each digit individually, such that the user can produce a wide range of forces on a given object (Fig. 3D). Allowing the user to control the position of the hand, in contrast to directly controlling force output, is consistent with the brain’s natural position-based encoding scheme for the hand48.

Shared control improves grip precision

As an initial validation of our shared controller, we had participants repeat the fragile-object transfer task described before (Supplementary Video 2). This time, however, we embedded a strain gauge into the “fragile” object49,50 to track the cumulative force exerted on the object by the hand (Fig. 4A). Measuring the grip force enabled us to analyze the range of grip forces under shared or human control, rather than just whether the participant exceeded a predetermined force. Grip force measurements from the “fragile” object were used solely for analysis purposes and were not used by the controller in any way. A diverse range of forces exerted on the object would imply the user can still modulate their grip force, and improved performance on the task would suggest the machine is still meaningfully contributing.

A Six intact-limb participants with no prior myoelectric control experience completed a fragile-object transfer task49,50. Using a prismatic precision pinch, the participants attempted to transfer an instrumented object over a barrier as many times as possible in two minutes without “breaking” the object by exceeding a force threshold. B Example data from the thumb as one participant completed the fragile-object task begins with the participant extending their fingers (dashed line) to wrap around the object (~0 to 0.5 s), and then flexing their fingers to grasp the object (~0.5 to 1 s). Once the object was within proximity of the fingers, the machine control (dotted line) provided a steady offset to the shared output (solid line) so the fingers maintained contact with the object (~1 s onward). Shared control smoothed the grip force (blue) as the fingers worked in parallel to transfer the object (~1.5 to 3 s). C Shared control resulted in significantly greater success (permutation test; p = 0.004). D Shared control also resulted in significantly lower peak forces (generalized linear model; p < 0.001). E We measured the average transfer rate of each trial for 12 measures per control strategy. F Cognitive load, as measured by a DRT, was not significantly different between human and machine control. G There were no significant differences in physical effort (i.e., muscle activation). Violin plots represent the distribution of the data; black bars indicate the median. Data from six intact-limb participants. Sample sizes are: 12 success rates per condition (2 repeated measures per participant); 222 peak forces for human control and 199 peak forces for shared control (aggregate of all attempts from all participants); 12 transfer rates per condition (2 repeated measures per participant); 398 DRT response times for human control and 460 DRT response times for shared control; 12 sEMG MAV averages per condition (2 repeated measures per participant). ** denotes p < 0.01; *** denotes p < 0.001. Numerical results are found in Supplementary Table 1. All statistical tests are two-sided.

As expected, forces recorded during the task showed participants were able to produce a wide range of grip forces under shared control (Fig. 4B). Participants approached the object while opening their hand, and then grasped around the object. Once the object was in proximity to the digits, the machine automatically adjusted its target position to the exact joint position necessary to make contact with the object. This stabilized the user’s grip around the object, effectively offloading the positioning of the digits to the machine and allowing the user to focus exclusively on the force they intended to produce. Indeed, we observed multiple events in which the user’s intent to minimize force on the object would have resulted in dropping or breaking the object, but the machine’s contribution to the shared control maintained a secure grip on the object (Fig. 4B). In comparison, user’s attempting the task with human control struggled to successfully transfer the object without breaking or dropping it as relatively small changes in the decoded position resulted in large changes in the grasp force (Supplementary Fig. 5A).

Relative to human control, shared control resulted in greater task performance, implying the machine contribution improved grip precision. As opposed to human control, shared control increased the participant’s success rate when transferring the fragile object without dropping it or exceeding the break threshold (59 ± 23% vs. 89 ± 10 %; p < 0.01; permutation test; Fig. 4C). Participants produced a similar variety of forces under shared control and human control (Fig. 4D), but they tended to use less force under shared control, in line with the task requirements (9.68 ± 4.95 N vs. 7.60 ± 3.53 N; p < 0.001; generalized linear model; Fig. 4D). Participants transferred the object at a similar rate under each control strategy (10.08 ± 2.87 transfers per min vs. 9.04 ± 2.92 transfers per min.; p = 0.07; permutation test; Fig. 4E).

Shared control improves grip security

When grasping an object, we instinctively maximize the contact area with the object while minimizing our grip force to ensure a stable and efficient grasp51. Importantly, our native hands regulate grip force on a digit-by-digit basis with millisecond precision52. In contrast, commercial prostheses typically move all digits in synchrony, following a predetermined trajectory to form a specific grasp. This ‘robotic’ motion results in an unequal distribution of pressure across the digits and an unstable grip.

We therefore sought to next validate the grip security afforded by our shared controller on a holding task with a larger spherical object (Fig. 5A). With our native hands, we tend to grasp small rectangular fragile objects, like those used in our fragile-object transfer tasks, with a prismatic precision pinch, often involving only two digits (e.g., the thumb and index)53. In contrast, for large spherical objects, we typically employ a spherical power grasp involving all of the digits53. Thus, a holding task30 involving a large ball assesses performance on the opposite end of the grasping spectrum, and similar improvements in performance would support the potential of the shared controller to generalize across a variety of activities of daily living.

A Six intact-limb participants with no prior myoelectric control experience completed a holding task30. Participants attempted to pick up a spherical ball with a power circular grasp and hold it for two minutes without dropping it. Participants had independent control of the thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers. All other parameters were the same. B Example data from the thumb during the holding task with shared control. The participant began by extending their fingers (dashed line) to wrap around the object (~0.5 to 1 s), and then flexed their fingers to grasp the object (~1 to 1.75 s). Once the object was within the grasp, the machine control (dotted line) provided a steady offset to the shared output (solid line) so the fingers made contact with the object (~1.75 s onward). Shared control effectively maintained a stable grip even when the human contribution varied and decreased over time (~2.5 to 6 s). With shared control, participants dropped the ball significantly less (permutation test; p = 0.037; C) and were able to hold the ball continuously for significantly longer (permutation test; p = 0.039; D). Participants tended to have more fingers making contact with the object (E), although this effect was not statistically significant. Shared control resulted in significantly less cognitive burden (generalized linear model; p = 0.016; F). Participants tended to exert less physical effort when using shared control, although this effect was not statistically significant (G). Violin plots represent the distribution of the data; black bars indicate the median. Data from six intact-limb participants. Sample sizes are: 12 drop counts per condition (2 repeated measures per participant); 12 maximum hold times per condition (2 repeated measures per participant); 12 average number of finger measurements per condition (2 repeated measures per participant); 398 DRT response times for human control and 468 DRT response times for shared control; 12 sEMG MAV averages per condition (2 repeated measures per participant). * denotes p < 0.05. Numerical results are found in Supplementary Table 1. All statistical tests are two-sided.

To this end, intact-limb participants were provided with control of each digit individually and were tasked to pick up and hold a large ball for two minutes (Supplementary Video 3). With shared control, participants would approach the ball while opening their hand, and then grasp the ball. As the digits came into proximity to the ball, the machine automatically adjusted its target position and continued to make positional adjustments for each digit as the participant fatigued or adjusted their grip over time (Fig. 5B). Such adjustments are consistent with the biological corrections in grip force seen in all phases of lifting and grasping an object23. However, the same degree of control of the four independent digits was not observed with human control, as noise and cross-talk between sEMG channels make precise, stable control difficult (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Relative to human control, shared control resulted in greater grip security. When using shared control, participants were less likely to drop the ball (2.33 ± 3.50 drops vs. 0.25 ± 0.45 drops; p < 0.05; permutation test; Fig. 5C). and were able to hold the ball longer without dropping it (54.01 ± 46.02 s vs. 77.61 ± 45.47 s; p < 0.05; permutation test; Fig. 5D). Participants also tended to have more fingers making contact with the ball, although this was not statistically significant (2.40 ± 0.48 fingers vs. 2.73 ± 0.65 fingers; p = 0.28; permutation test; Fig. 5E).

Shared control reduces cognitive burden

Activities of daily living often involve dividing attention between multiple simultaneous subtasks; for example, holding a jar while twisting off its lid. As such, a top priority for prosthesis users is less attention-demanding control8. To this end, we had participants complete a secondary detection response task (DRT) while performing the fragile-object transfer task and the holding task. The DRT provides a simple yet sensitive measure of cognitive resource allocation based on response time to a stimulus54, and has also been used to assess the cognitive load of prostheses55.

For the holding task, shared control resulted in less cognitive demand than human control. Participants had significantly faster response times on the secondary DRT when using shared control (0.46 ± 0.26 s vs. 0.40 ± 0.26 s; p < 0.05; generalized linear model; Fig. 5F). While there are limited research studies using the DRT to quantify the cognitive burden of using a myoelectric hand56, research into the effects of cognitive load on driving indicates that a change of 50 ms in the response times corresponds to a noticeably more difficult task, as human response times to the tactile DRT generally range from approximately 300 ms to 1 s57,58,59. Without an additional task, the response time to the DRT was measured to be 250 ms (Supplementary Fig. 7). Given this, the measured decrease of 60 ms corresponds to a 29% decrease in cognitive burden with respect to the range of response times when using shared control, which is similar to the 30% decrease in cognitive load observed when switching from completing a task with a 1-DOF bionic hand to an intact hand (Supplementary Fig. 7). Shared control also resulted in less muscle activity, although this was not statistically significant (60.16 ± 29.57 µV vs. 46.96 ± 8.95 µV; p = 0.17; permutation test; Fig. 5G).

No significant differences were observed for cognitive or physical burden for the previously discussed fragile-object task (Fig. 4F and 4G; p > 0.05). This may be due to the time-based component of the task; transfers are performed so quickly that the user stays engaged throughout the entire task, making the contributions from the machine more subtle.

Shared control improves grip security and precision for upper limb amputee participants

Having validated the shared controller with intact-limb participants on two tasks involving different grips and forces, we next sought to validate the shared controller with upper-limb amputees. To reduce experimental time and document performance on yet another grip, we had four transradial amputees perform a fragile-object holding task, in which they picked up and held an instrumented fragile object49,60 using an intermediate tripod pinch53 for up to two minutes (Fig. 6A). The force regulation used in this task is akin to that used when holding a plastic cup of water without dropping or crushing it. The amputee participants also completed the secondary DRT during the fragile-object holding task to measure cognitive load.

A Four participants with transradial amputations completed a fragile-object holding task. Participants attempted to hold an instrumented object as securely as possible for two minutes without exceeding a grip force threshold. Participants used an intermediate tripod pinch to complete the task. B Example data from the thumb as one participant completed the fragile-object holding task. The participant began the task by flexing (dashed line) to grasp the object (~0 to 1 s). In this case, the participant exerted too much force (blue line), “breaking” the object (~1 to 2.5 s). In response to the auditory feedback, the participant substantially reduced their grip force, but, in combination with the machine controller, maintained contact (dotted line). The shared output was able to maintain enough force to avoid dropping the object (~2.5 to 3.5 s). With shared control, participants held the object for significantly longer (permutation test; p = 0.002; C while exerting significantly less force on the object (generalized linear model; p < 0.001; D). They also tended to drop the object less frequently, although this effect was not statistically significant (E). Additionally, shared control significantly reduced the cognitive burden of the participants, as indicated by faster response times on the secondary DRT (generalized linear model; p < 0.001; F). Shared control and human control required similar levels of physical effort (G). Violin plots represent the distribution of the data; black bars indicate the median. Data from four transradial amputee participants. N = 14 trials per condition (repeated measures per participant shown in Table 1); 14 maximum hold times per condition; 226 average forces for human control and 140 average forces for shared control; 270 DRT response times for human control and 313 DRT response times for shared control; 14 sEMG MAV averages per condition (repeated measures per participant shown in Table 1). ** denotes p < 0.01; *** denotes p < 0.001. Numerical results can be found in Supplementary Table 1. All statistical tests are two-sided.

Relative to human control, shared control resulted in greater grip security and greater grip precision. Participants were able to hold the object without dropping or breaking it for a longer duration with shared control (7.81 ± 12.33 s vs. 51.56 ± 45.0 s; p < 0.01; permutation test; Fig. 6C). Participants were still able to produce a wide range of grip forces with shared control, but their average grip force was lower when using shared control (14.86 ± 4.54 N vs. 9.74 ± 4.27 N; p < 0.001; generalized linear model; Fig. 6D). The participants also dropped the object less with shared control, although this was not statistically significant (9.64 ± 6.46 drops vs. 4.64 ± 4.88 drops; p = 0.10; permutation test; Fig. 6E).

Shared control also reduced the cognitive burden of the amputee participants. Response times to the secondary DRT were significantly lower when using shared control (0.74 ± 0.41 s vs. 0.62 ± 0.38 s; p < 0.001; generalized linear model; Fig. 6F). This 120-ms change in their response times corresponds to a 24% decrease in cognitive burden by using shared control. To frame this change with respect to other real-world scenarios, a 120-ms improvement was also observed when drivers operated their car radio at a standstill versus operating their radio while driving61. A comparison between the intact-limb and amputee participant’s response times indicates that the amputee participants were slower to respond than the intact-limb participants (Supplementary Fig. 8), which could be attributed to the different task, or to their amputation or age. Consistent with the results from the intact-limb participants, we observed no difference in physical burden between the control strategies (49.89 ± 43.28 µV vs. 45.89 ± 39.0 µV; p = 0.54; permutation test; Fig. 6G).

Shared control generalizes to activities of daily living

An important concern with controlled laboratory experiments is whether the tasks used to assess the performance of the prosthesis are ecologically valid. For example, do improvements in manipulating fragile objects and holding oddly shaped objects translate to improved performance on activities of daily living (ADLs)? Inherent to that question is whether the shared controller can generalize to new and diverse conditions, as would be experienced with ADLs. We evaluated this by having the participants complete a variety of ADLs with shared control and human control (Supplementary Video 4). Improvements are difficult to quantify with ADLs, but the participants noted that shared control was particularly helpful for tasks involving precise hand positioning and force regulation. Three tasks stood out: bringing a disposable cup to their mouth, transferring an egg between two plates, and picking up a piece of paper (Fig. 7). Each of these tasks corresponded to one of the grasps used in the prior experiments. Drinking from the disposable cup used a power grasp (Fig. 5A), moving the egg used a tripod grasp (Fig. 6A), and moving the piece of paper was completed with a pinch grasp (Fig. 4A). One participant specifically noted that these tasks were incredibly difficult, if not impossible, with human control, but that shared control made the tasks reasonable. Indeed, with only human control, participants repeatedly broke/dropped the egg, crushed/dropped the cup, and crinkled/dropped the piece of paper; under shared control, they were able to consistently complete all the tasks (Supplementary Video 4).

Participants completed various ADLs with and without shared control. Shared control was particularly helpful for tasks that involved a precise grasp and grip force, including lifting a disposable cup to their mouth without crushing it using a power grasp (A), moving an egg without breaking it using a tripod grasp (B), and picking up a sheet of paper without crinkling it using a pinch grasp (C). One participant also attempted to drink out of a disposable cup six times with both control algorithms (D). Under shared control, the participant successfully lifted the cup to their mouth and set it back on a table four times, but was unable to do so a single time with human control alone. E No significant differences were observed in the time it took for the participant to make a grasp that they felt confident in and lift the cup up to their mouth.

Occupational therapists often rate amputee patients’ performance on activities of daily living using subjective graded scales. For example, the Activities Measure for Upper-Limb Amputees (AM-ULA) scores amputees on 5 categories: extent of completion, speed of completion, movement quality, skillfulness, and independence. Although the activities completed with AM-ULA are not well-suited for next-generation prostheses capable of a delicate touch39,62,63, the rate and speed of completion score criteria are quantitative and can easily be applied to other activities of daily living. To this end, we quantified the speed and success rate of one participant as they completed six trials of the drinking task with disposable cups, during which they attempted to pick up the cup from the table, bring it to their mouth and mime a sip, and then return it to the table. This real-world activity of daily living is considerably difficult. These common cups break with approximately 7 N; in contrast, the fragile holding task required the amputees to maintain forces below 15 N. Under human control, the participant crushed the cups in five out of the six trials and dropped it twice (Fig. 7D). However, with shared control, the participant successfully completed the task four out of the six times. No significant difference in the task speed was observed; the participant took 9.67 ± 3.27 s to make a grasp and lift the cup to their mouth with human control, and only 7.60 ± 2.59 s with shared control (p = 0.26; unpaired t-test; Fig. 7E).

Discussion

This work introduces a generalizable framework for enhancing the performance of bionic arm users through embedded multimodal sensors and autonomous control. We show generalizability through a variety of different grasps and tasks and facilitate translation through integration with a widely used commercial prosthesis and by validating the system with four amputees, a sizable cohort for the transradial population. Indeed, this work represents the first demonstration of shared control with multiple amputee participants using a physical prosthesis. Importantly, we show enhanced performance both in terms of physical and cognitive function; participants had better grip security, enhanced grip precision, and reduced cognitive burden with no increase in physical burden.

These results build on prior sensorized autonomous bionic arms by leveraging distributed multimodal sensors within a commercial prosthesis. In contrast to camera-based systems26,27,28,29, our distributed proximity sensors require substantially less power for operation and data analysis. Prostheses should ideally operate continuously for an entire day; greater power requirements led to larger, heavier batteries, and weight is a critical priority for prosthesis adoption8. Distributed proximity sensors also provide more robust operating conditions. With a single camera, users must take time to methodically approach objects to ensure the camera has a line of sight to determine the position of each digit29. In contrast, a distributed system provides several viewing angles and allows each digit to operate independently of the others.

In principle, the shared control algorithm presented here could operate with only a single modality that detects contact via fingertip pressure sensors already available in commercial hand prostheses1,64,65. However, in practice, the multimodal configuration provided more robust control, given that sensor data is often non-ideal in the real world. Using pressure sensors alone requires the machine control to operate entirely in a reactive manner. The pressure sensors would need to be sampled at a much faster rate than the actuation speed of the prosthesis to ensure the machine stops quickly enough to provide near-zero contact force. In practice, this was not feasible due to the users’ desire to operate the prosthesis quickly, the momentum of the prosthesis once in motion, the delays associated with power-efficient sensor readings, and wireless communication. In contrast, the feedforward nature of the infrared sensors allows for a more seamless blending of the human and machine intent. Additionally, the infrared sensors have the added benefit of initiating movement on their own to maximize the number of digits making contact with the object. Combined, the multimodal infrared and pressure sensors provide both a feedforward and a feedback approach to ensure robust operation. With this in mind, the fingertip sensor modules used in this work have been designed to be retrofitted onto different commercial prosthetic hands, providing a straightforward means to translate the shared control algorithm36.

Nevertheless, even the most advanced sensorized autonomous bionic arms are unlikely to capture a user’s intent perfectly. Prosthesis agency, the sense that you are the author of your actions, is an important factor for prosthesis design66,67. To this end, shared control has the potential to maintain a strong sense of agency while offloading some of the cognitive burden of grasping. Here, we introduce a new shared control framework that uses a dynamically weighted sum to allow simultaneous and independent contributions from the user and the autonomous bionic arm. This approach was inspired by biological grasping that maximizes contact area while limiting grasping forces68. This is a demarcation from prior works that toggle between human and machine control29,30, or use a fixed proportion of human and machine control32,45. Our decision to pursue dynamic weighting was guided by several failed attempts to leverage these past frameworks and past literature that suggested that continuously sharing control would improve performance30. Toggling between human and machine control requires the machine to be able to operate autonomously at a level greater than that of a user. Given the variety of objects grasped and forces exerted in daily activities, this framework fails when attempting to generalize across multiple tasks. Indeed, the most complete shared control work to date noted this critical problem30. The alternative, sharing some fixed proportion of control between the human and user, also failed to generalize well because it requires the machine to be consistently useful across a range of conditions. From our experience, fixed support from a machine designed to enhance grip security and grip precision (a challenge for modern prostheses) ultimately hindered performance on simple tasks (that would not otherwise be a challenge for modern prostheses). The dynamic framework introduced here allows for generalizable control by ensuring the user maintains agency over the bionic arm at all times.

One could imagine a few scenarios where the shared control framework proposed in this work might impede functionality; for example, when the machine control either lags or precedes the human’s intent. In theory, the machine controller could lag behind the human’s intent or fail to detect an object if the line of sight to all of the digits is limited. In this event, the user will have decreased precision until contact is made, at which point the machine’s goal will update, and the shared control scheme will operate as usual. In theory, it is also possible for the machine controller to precede the human’s intent. For this to happen, the user would have to reach for an object and surround the object with the prosthetic fingers, but not desire to grasp it. This scenario is uncommon and unusual in activities of daily living, where grasping and reaching are performed simultaneously69. Nevertheless, in this event, the machine would attempt to move the fingers closer to the object to make initial near-zero contact with the object. Then the user could still achieve their intent, but would have to exert more physical and cognitive effort. Given the rarity and minimal impact of the machine lagging or preceding the human’s intent, we believe the shared control framework presented here provides a generalizable approach towards offloading some of the cognitive burdens of dexterous control while maintaining user autonomy and robust performance when working with non-ideal sensor data in the real world. These examples provide a rough baseline for how the system might behave under relatively simple conditions. However, the impact of more complex sensorimotor tasks, like opening a bottle cap or tying shoelaces remains an important question worthy of future research.

We demonstrated that the shared control framework can generalize to a variety of objects and grip patterns common in activities of daily living. Indeed, the tasks performed mimicked standard clinical tasks to assess patient functionality. For example, the fragile-object transfer task is effectively a more difficult version of the box and blocks tasks, and the holding tasks with different-shaped objects are similar to portions of the Southhampton Hand Assessment Procedure70. However, this does not necessarily mean that shared control will generalize well to everyday real-world use. A long-term at-home clinical trial, along with modern clinical assessments, like the Activities Measure for Upper Limb Amputees (AMULA)71, is necessary to validate real-world generalizability and to demonstrate improvements in independence and quality of life. Such a study could also answer questions regarding the impact of shared control on prosthesis adoption and learnability.

Shared control resulted in immediate improvements in functional and cognitive performance in naïve users. An important question remains as to whether shared control can provide similar, or even greater, benefits to experienced users. As a simple first-order assessment of learning, we explored the change in performance for human control and shared control between the first and last experimental blocks of the fragile-object transfer task, holding task, and fragile-holding task (Supplementary Fig. 9). No learning took place under shared control; there were no significant differences for any of the tasks. Under human control, no learning took place for the holding task or fragile-holding task, but there was a significant improvement in success rate on the fragile object transfer task. Given the timeframe of the tasks performed herein, we suspect that the limited learning that did take place would mostly be attributed to task familiarization. Future work should explore long-term motor learning associated with shared control. Shared control could potentially improve motor learning, as decreased cognitive burden is associated with an increase in motor skill acquisition72,73. In contrast, the machine contribution could also act as an additional hidden variable within the user’s internal model that impedes learning74. Regardless of long-term outcomes, the short-term benefit of enhanced dexterity and reduced cognitive load could potentially improve prosthesis adoption during the critical golden window after amputation75.

Among the amputee patients, shared control provided similar benefits to those who used a myoelectric prosthesis and those who used a body-powered prosthesis. Future work should explore the impact of shared control among myoelectric and body-powered users with a greater number of patients. Shared control is most straightforwardly applicable to myoelectric users since shared control could be readily implemented into commercial multiarticulate bionic arms like the TASKA hand used in this study. However, the ability of shared control to reduce the cognitive load of controlling a multiarticulate bionic arm may also make myoelectric control more appealing to patients who would have otherwise opted for a body-powered prosthesis. Although there are many differences between body-powered and myoelectric prostheses (e.g., weight), body-powered prostheses are often considered to require less attention, and this is a major contributing factor in prosthesis selection76. Indeed, body-powered prostheses require less training time77 and provide residual sensory feedback that has been hypothesized to reduce cognitive and visual demand78. Given that shared control can reduce the cognitive demand of a myoelectric prosthesis, future work should explore the ability of shared control to reduce prosthesis abandonment among myoelectric users, as myoelectric prostheses have yet to improve prosthesis adoption over body-powered alternatives5.

Commercial myoelectric prostheses are usually controlled in an open loop with no explicit feedback. The few commercial prostheses with feedback typically use motor current to indirectly estimate and limit exerted force. However, there is a recognizable trend of more commercial bionic hands becoming more sensorized with multiple pressure sensors across the hand1,64,65. Embedded pressure sensors allow for faster reactions and gentler forces and maintain functionality during passive interactions in which the motors are not active. As sensor arrays become more common in commercial bionic hands, shared control work will become more relevant and impactful. Related work has shown that integrated force sensors can also close the loop by driving haptic feedback provided directly to a user39,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89. The present work complements these related works by demonstrating another value of integrating force sensors into prostheses.

Commercial myoelectric prostheses are also typically controlled using either pattern recognition90 or dual-site control91,92, both of which require the user to sequentially select among grip patterns with a fixed force output91. In contrast, here we demonstrate simultaneous and proportional control of each digit in real-time. By eliminating the need to sequentially switch between grip patterns, simultaneous and proportional control has been shown to improve performance relative to pattern recognition for a 3-DOF prosthesis93. Simultaneous and proportional control of more than 3 DOFs has been achieved previously using a modified Kalman filter40. Indeed, a modified Kalman filter has been used to control up to 10 DOFs94, deployed on computationally limited hardware95,96,97, and used to complete various activities of daily living39,40,98. Although promising, it is recognized that the performance and intuitiveness of simultaneous and proportional control algorithms decrease as the number of controllable DOFs increases, and this is also true for the modified Kalman filter95. In the present work, we demonstrate the ability of shared control to enable simultaneous and proportional control of a greater number of DOFs while decreasing the overall cognitive burden.

An important question remains as to whether the shared control framework employed herein can be readily extended to other, more traditional, control strategies like pattern recognition or dual-site control. Explicit validation is required, but in theory, both pattern recognition and dual-site control could benefit from the shared control framework outlined here. Parallel dual-site control of multiple DOFs93 is akin to the modified Kalman filter, and we would likely see similar improvements in grip security, grip precision, and cognitive load. In the case of pattern recognition, the shared control framework could increase grip security and/or precision by helping maintain digit contact and distributing forces more equally among the active DOFs, but would likely have minimal impact on cognitive load. Future shared control frameworks with pattern recognition in mind could leverage the embedded sensors to inform grip selections, which, if done well, could improve the speed and reduce the cognitive demand of coordinated multi-gesture tasks.

The Southampton Hand was one of the first prostheses to utilize integrated sensors to regulate grip force99. The Southampton Hand was controlled by the user toggling a “touch” mode in which the hand would move towards an object and stop upon force feedback. The user would then regain control to trigger a subsequent increase or decrease in grip force as needed. In contrast, the present work leverages proximity sensors to optimize grip configuration and force prior to making contact and blends human and machine intent for precise position control rather than toggling between the human and machine for iterative refinement. During experiments with the Southampton Hand, researchers observed that participants had to dedicate less attention to using the Southampton Hand compared to a conventional myoelectric hand100. Since then, other research has detected a decrease in cognitive load when using shared control via the NASA TLX survey28. The present work also builds on these past works by quantifying a reduction in cognitive load through a nonsubjective metric, the detection-response task. Notably, the detection response task used in the present work provides an objective measure of cognitive load, establishing a benchmark for the intuitiveness of prosthetic control strategies. More intuitive control may ultimately increase prosthesis usage, given that poor and unintuitive control are primary reasons for abandonment6.

Methods

Human testing

Nine intact-limb participants (22.3 ± 2.40 years old; 44% female) and four participants with transradial amputations (45.75 ± 14.36 years old; 100% male) were recruited for this study. The intact limb participants were 89% right-hand dominant, and the amputee participants were 100% right-hand dominant before amputation. Table 1 contains further details about the amputee participant population. None of the intact limb participants had any prior experience controlling myoelectric devices. Informed consent, experiment protocols, and patient image collection were carried out in accordance with the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB 00098851), the Department of the Navy Human Research Protection Program, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Signal acquisition

Surface electromyography (sEMG) was collected from the participants using 32 sEMG electrodes. sEMG was sampled at 1 kHz and filtered using the Summit Neural Interface Processor (Ripple Neuro Med LLC). sEMG signals were band-pass filtered with a lower cutoff frequency of 15 Hz (sixth-order high-pass Butterworth filter) and an upper cutoff frequency of 375 Hz (second-order low-pass Butterworth filter). Notch filters were applied at 60, 120, and 180 Hz. Differential sEMG signals were calculated for all possible pairs of channels, resulting in 496 differential pair recordings40. The mean absolute value (MAV) was then calculated for the 32 single-ended and 496 differential recordings at 30 Hz using an overlapping 300-ms window40. sEMG was measured using a 32-channel, dry electrode compression sleeve for intact-limb participants41 and from 32 adhesive electrodes (Nissha Medical Technologies) placed in a grid pattern on the residual forearm for amputee participants. The embedded fingertip sensors were sampled at 30 Hz and passed through a median filter with a time window of 3 samples.

Sensorized fingertips

The sensorized fingertips (Point Designs, Broomfield, CO, USA) contained a barometric pressure sensor (MS5637-02BA03, TE Connectivity) and a proximity sensor (VCNL4010, Vishay Semiconductor)36. The proximity sensors operate by emitting a specific wavelength of infrared light and measuring the intensity of any reflections. The sensors are mounted in a plastic housing and embedded in silicone. The proximity sensor is capable of detecting surfaces up to 1.5 cm away. The pressure sensor embedded in the silicone is capable of reliably detecting forces less than 1 N and up to 30 N (Supplementary Fig. 1). Each of the fingertip sensors communicates with a central microcontroller (ESP32, Espressif, Shanghai, China) mounted on the back of the prosthetic hand. The housing of the fingertip sensors was designed in multiple form factors to fit different commercial bionic hands, but only the TASKA form factor was used in this work.

Bionic hand interface

For intact-limb participants, the sensorized bionic hand was mounted to a bypass socket that was worn on the left arm101. For amputee participants, the sensorized bionic hand was mounted to an adaptable 3D-printed functional test socket102. After applying the sEMG electrodes, the residual limb was wrapped using a self-adherent wrap to apply compression and manage cables. The adaptable socket was then placed over the wrapped electrodes and secured by wrapping an elastic bandage around the socket to provide compression and around the bicep of the upper arm to prevent slipping. All participants used a left-handed TASKA hand (TASKA, Christchurch, New Zealand).

Initial fragile transfer task with autonomous machine control

To assess how incorporating information from the sensorized fingertips might affect bionic arm control, three intact limb participants completed a fragile-object transfer task with a mechanical fragile object103 (Fig. 2B). The fragile-object transfer test is a derivative of the widely used box and blocks test of hand dexterity104 in which the participants must limit the grip force applied to the block. The fragile-object test provides additional information beyond the box and blocks test and has been used extensively to validate the fine dexterity of prostheses39,105,106. The transfer task involved picking up a single fragile object and translating it over a barrier without exceeding a predetermined grip force. Once the object was broken, dropped, or successfully transferred, or if the trial timed out, then the trial was ended, and the object was reset. Participants had up to 45 seconds to complete the trial with a verbal warning when 15 seconds remained. The barrier was 62.5 mm tall.

The mechanical fragile object consisted of a steel plate, a steel lever, a magnet that held the steel lever in place, and a weight. When grasped above the holding force of the magnet, the fragile object would “break,” and the lever would emit a clicking sound. The break force could be adjusted by sliding the magnet along the lever. The object weighed 496 g.

Each of the three intact-limb participants completed the fragile object transfer task using a prismatic precision pinch grasp with human control and with autonomous machine control. Autonomous machine control was engaged when the participant flexed and disengaged when the participant extended their hand. When autonomous machine control was engaged, the fingers would close when a surface was detected by the proximity sensors and stop when contact was detected via the pressure sensors (Fig. 2A). A proximity measurement of 30 indicated that an object was detected, and a pressure measurement of 30 indicated that contact had been made.

The experiment consisted of the participants completing two blocks of the fragile object transfer task with each control scheme, for a total of four blocks, in a pseudo-randomized counterbalanced format. Each block consisted of 10 trials. After the second block of each control scheme, participants completed the NASA TLX survey. Each participant completed the experiment twice, once with a break force of 19 N and another with 17 N (Supplementary Fig. 2). Data from the two experiments were aggregated. The pressure readings from the fingertips from each trial and the success rate from each block were recorded as measures of grip precision. Due to the unitless nature of the pressure sensors, pressure measurements were normalized by the maximum recorded value for each participant. The sEMG MAV was recorded and averaged across channels and each trial as a measure of physical exertion, and the NASA TLX served as a measure of perceived workload.

Shared control algorithm

Machine control

The machine control algorithm predicts the kinematic position of each digit in real time using proximity and pressure values from a sensorized prosthetic hand. A left-handed TASKA hand was retrofitted with fingers containing pressure and infrared proximity sensors (Point Designs LLC, Lafayette, CO, USA) (Fig. 1A)26,107. A multilayer perceptron (MLP) was designed with a single hidden layer to predict object distance from the proximity and pressure sensors107. Training data for the MLP was collected by oscillating each digit towards and away from 3D-printed objects. The ground-truth distance from the object for the training data was computed by measuring the kinematic position of the finger upon initial contact with the object (i.e., when pressure was first recorded) and then retroactively using the difference between that kinematic contact position and the current position to determine the current distance to the object

The machine's position goal was the predicted kinematic position of each digit that would result in contact with the object, computed as the sum of the current position of the digit and the predicted distance to the object. A first-order lowpass filter with a cutoff frequency of 90 Hz was used to smooth the resulting predicted kinematic position for the machine goal, \({u}_{m}\) (Fig. 1B). The digits would only move to \({u}_{m}\) if the proximity sensors exceeded three times the standard deviation of their noise. A proximity measurement of 30 indicated that an object was detected. This threshold was implemented to prevent the machine control from responding to random noise. Once contact was detected, the machine predictions were frozen until the grasp was released to prevent undesired jitter. Contact was defined as the pressure measurement exceeding 30 or the proximity measurement exceeding 1000 (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B). By developing the machine controller around achieving contact, rather than modulating force, there is no dependence upon the range of the proximity or pressure sensor beyond the detection of contact. The respective thresholds were set such that the fingers would touch a given object but not exert a measurable force on it. \({u}_{m}\) was limited to a range of −1 to +1, where −1 represents maximum digit extension, and +1 represents maximum digit flexion.

Human control

The human position goal, \({u}_{h}\), was computed using a modified Kalman filter (MKF)40. The MKF was trained to correlate sEMG features measured from the forearm to kinematic positions. Training data was collected as the participants actively attempted to move their (intact or amputated) hand alongside preprogrammed movements of the prosthesis. Preprogrammed movements consisted of both flexion and extension for the thumb, index, middle, ring, and pinky fingers. Participants completed four trials of flexion and four trials of extension for each digit. The resultant MKF provided the user with proportional position control of all five digits on the TASKA hand. sEMG features used for estimating motor intent consisted of the 300-ms smoothed mean absolute value (MAV) of 528 sEMG channels (32 single-ended channels and 496 calculated differential pairs) calculated at 30 Hz. To reduce computation complexity, the 528 sEMG features were down-selected to 48 sEMG features via Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization45,108. The human position goal, \({u}_{h}\), was limited to a range of −1 to +1, where −1 represents maximum digit extension, and +1 represents maximum digit flexion. A nonlinear, latching filter was applied to the human position goal to limit jitter and smooth the human intent for the ADL assessment44.

Shared control

We aimed to develop a shared-control algorithm that continuously blends human and machine control. Unlike prior work, where control of the hand was toggled between human and machine control26,29, the shared-control law is fixed32, or the grip force is limited30, the shared-control algorithm we present in this paper uses machine control to modify human control dynamically while still allowing the human to modify the grip force107. The motivation for this design stems from the idea that the machine controller should continuously assist the human operator with the grasp, but never be in complete control of the hand.

The shared control framework was designed such that the machine control would conform each digit to the surface of a detected object. If no object was detected, then the user had full control of the hand, enabling them to flex the fingers towards an object if the sensors failed to detect the surface. Once the machine controller detected the object, it would move the fingers to make contact with the surface and hold its position. The user could then flex and extend the grasp about the point of contact to make a tighter or more relaxed grasp. The mathematical implementation of this design is explained below.

Control of each DOF was shared between the human position goal, \({u}_{h}\), and the machine position goal, \({u}_{m}\). The shared goal, \({u}_{s}\), was computed as the following:

This effectively attenuates the human’s control of the hand in proportion to the machine’s control output. The human control signal is also modified by a normalized exponential to give the user greater precision during small movements in exchange for less precision during large movements. The exponential attenuation was implemented to assist the user in making finer motions and to limit the user from over-flexing. The damping parameter α was set to α = 3 for intact limb participants, such that a human position goal of 0.5 would be remapped to approximately 0.2. Preliminary data indicated that a more aggressive scaling could further improve control, so for amputee participants, α was set to α = 4, remapping a human position goal of 0.5 to approximately 0.1 (Supplementary Fig. 4C). The scaling factor was increased to α = 7 for the ADL testing.

Because shared control is only useful for grasping, a kinematic threshold was used to disable the shared-control algorithm during extension26. For example, if the MKF predicted that the human was attempting to extend to a position greater than 75% of the extension range, shared control was disabled to allow fluid hand opening. To return to the shared-control state, the user had to flex 1% of the flexion range. The 1% threshold was chosen so that shared control would be effectively re-enabled as soon as the user stopped opening the hand. This aided the participant in releasing the object without altering the evaluation of the shared controller’s performance during grasping and gave the user the ability to extend DOFs if \({u}_{m}=1\).

Cognitive and physical burden

To determine the cognitive burden associated with each control strategy, we measured cognitive load with a secondary tactile detection-response task (DRT) that the participant simultaneously completed while using the prosthesis55,109,110. The DRT requires the participant to push a button with their intact or contralateral hand in response to a small vibrating motor on their collarbone. The bilateral amputee had the button secured to their hip and pressed it using their residual limb. Both the response rate (i.e., how often they respond to the vibratory stimuli) and response time (i.e., how long it takes to press the button after the vibratory stimulus) are used as direct measures of cognitive load. In accordance with ISO 17488:2016, vibrations were applied according to a Gaussian probability distribution function with a mean of three seconds and a variance of two seconds. The response rate to the DRT has been correlated with increased cognitive load and task difficulty57,58,59. In a separate experiment, the baseline response times to the tactile DRT without an additional task were measured to be approximately 250 ms (Supplementary Fig. 3). In driving tasks, average response times vary with task difficulty, ranging from baseline to approximately 800 ms, where a ceiling effect is observed57.

We also analyzed the shared control’s effect on the physical burden of using the bionic hand. The mean absolute value of the sEMG magnitude was used to measure the user’s physical effort (muscle activity). This measure included all 32 electrodes on the user’s forearm or residual limb.

Fragile transfer task with shared control

Six intact-limb participants completed a fragile-object transfer task with the Electronic Grip Gauge (EGG)60. The EGG consists of a weighted 3D-printed block containing a load cell and accelerometer to measure grip force and lift force, respectively. Similar to the mechanical fragile object, the EGG would emit a sound when the grip force exceeded a threshold. As opposed to the pass-fail nature of the mechanical fragile object used to evaluate the autonomous controller, the EGG provides time series data, allowing for a deeper analysis of how different control schemes might affect grip force, such as analyzing the average or peak grip forces.

During the fragile-object task, participants used a prismatic precision pinch grasp to pick and transfer the object over a barrier as many times as possible in 120 seconds without dropping or “breaking” the object by exceeding a grip force of 17 N. Data collected from the experiment involving the autonomous controller (Supplementary Fig. 2) indicated that the break force should be set to 17 N rather than 19 N to make the task more difficult. Participants also completed the detection response task (DRT) as a secondary task during the experiment56,59,110. In order to properly measure cognitive load, the DRT and fragile-object transfer task needed to be run continuously rather than on a per-trial basis59. Each participant completed two trials of the fragile object transfer task using human control and two trials using shared control in a pseudo-randomized counterbalanced format. Participants were given up to 1 minute to practice before each experimental block. The number of times the participants broke or dropped the EGG from each trial, the number of successful transfers from each trial, and the grip force during each grasp attempt were recorded as measurements of motor precision. The DRT response time was recorded as a metric of cognitive burden, and the average sEMG activation during the trial was recorded as a metric of physical burden.

Holding task

To assess the shared controller’s ability to assist with gross, prolonged movements, six intact-limb participants completed a holding task in which they were instructed to use the prosthesis to pick up a 3D-printed sphere and hold it for two minutes without dropping it. Participants controlled four independent DOFs for this task: the thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers. The pinky finger was not sensorized and was linked to the control of the ring finger. The participants were instructed to pick the object up using a power circular grasp as quickly as possible and to pick it back up as quickly as possible if, at any point, they dropped it. Each participant completed two 120-second trials of the holding task using human control and two 120-second trials of shared control in a pseudo-randomized counter-balanced format to prevent order effects such as fatigue or learning. Participants were given up to 1 minute to practice before each experimental block. Participants also completed the DRT as a secondary task during the experiment. The number of times the object was dropped, and the average number of fingers used when grasping (determined by non-zero pressure sensor data), were recorded as measures of grip security. Contacting an object with more digits results in a more secure grasp30. The response times to the DRT were recorded as a measure of cognitive burden, and the average sEMG activation during the trial was recorded as a metric of physical burden.

Fragile holding task