Abstract

Sustainable crop production in a warming climate requires land management strategies that support plant-soil-microbe interactions to optimize nitrogen (N) availability. Here, we investigate the interacting effects of 10 years’ experimental warming and management (conservation vs. conventional agriculture) on wheat N acquisition using in situ 15N-labeling, root metabolomics and microbial metagenomics. We find that warming amplifies the positive effects on wheat nitrate uptake by 25% in conservation agriculture compared to conventional agriculture, while alleviating microbial competition for N. Additionally, warming increases soil gross N mineralization and nitrification rates by 191% and 159%, but decreases microbial immobilization by 24% in conservation agriculture. Concurrently, microbial genes for mineralization and nitrification are enriched, while those for N immobilization and nitrate reduction are reduced under conservation agriculture with warming. These shifts are driven by alterations in root primary and secondary metabolites, which reshape N-cycling microbial functional niches and optimize multiple microbial N processes beyond mere organic N mining. This reconfiguration increases carbon-nitrogen exchange efficiency, enabling wheat to outcompete soil microorganisms for N. Collectively, our findings suggest that conservation agriculture enhances plant N acquisition by strengthening plant-soil-microbe interactions under climate change, providing a sustainable strategy for future food security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global warming presents substantial challenges to sustainable agriculture1. Intensified agricultural systems increasingly rely on mineral nitrogen (N) fertilizers to support crop yields, which frequently leads to elevated N losses with poor economic and environmental consequences2,3,4. Sustainable field management strategies that foster adequate soil-based N supply through beneficial plant-soil-microbe interactions may reduce reliance on external N inputs, and hold great potential to support crop growth and resilience to environmental stressors, including climate warming5,6,7. Conservation agriculture covers 9–15% of global arable land8 and is promoted widely as a nature-based solution to maintain food production while promoting soil multifunctionality9,10,11. It supports crop yields by moderating soil temperature12, improving water13 and N use efficiency14,15, and increasing microbial abundance and diversity16. Under long-term experimental warming, conservation agriculture alters soil microbial community structures by increasing root biomass and rhizodeposition inputs to soil12. However, the interactive effects of long-term conservation agriculture and warming on plant-soil-microbe interactions and the consequences for crop nutrient acquisition at the field scale remain poorly understood due to the rarity of experimental systems.

Major uncertainty exists about the effects of climate warming on soil N cycling, N partitioning between plants and soil microorganisms, and the consequences for the productivity of cropping systems. Plant N acquisition is constrained by soil N availability, which is vulnerable to abiotic stress induced by environmental changes14,17. Rising temperatures could intensify competition for soil N between plants and microorganisms17,18,19, with microorganisms generally considered as more effective competitors20,21,22. However, plants can adapt their nutrient uptake mechanisms through integrated starvation or satiety responses to changes in soil nutrient concentrations23. Substantial researches have explored how non-crop plants modulate root metabolism to enhance beneficial interactions with microorganisms for nutrient acquisition, and most of these studies were conducted under axenic or monoxenic conditions in vitro21,24. Mutualistic ‘carbon-nitrogen exchange (C-N)’ relationships between plants and microorganisms can alleviate N competition under warming if root exudation increases the organic carbon supply to soil microorganisms, thereby stimulating microbial activity and accelerating organic N mineralization25,26,27. However, plant N demand under warming conditions is rarely synchronized with soil organic N mineralization because multiple microbial processes drive soil N availability28,29. Microorganisms involved in soil N transformation processes act both as sources (e.g., mineralization and nitrification) and sinks (e.g., immobilization and denitrification) of plant-available N, thereby forming the basis for cooperative or competitive interactions with plants30. Microbial processes affecting soil N availability may be modulated by warming-induced compositional changes in root exudates31,32. Agriculture management practices also strongly affect root exudate profiles and rhizosphere microbial communities33,34,35,36. For instance, tillage intensity can alter the release of organic acids and the abundance of plant growth-promoting microorganisms involved in N cycling33. Expanding our understanding of the interactive effects of warming and agricultural management on root metabolism and the microbial metabolic functions, including soil N transformation, is crucial for mitigating the impacts of climate change on N supply to crop plants.

Herein, we conduct a 15N labeling tracer experiment in situ, along with a 15N isotope dilution experiment, to investigate the interactive effects of agricultural management practices (conventional versus conservation agriculture) and warming (ambient versus elevated temperatures) on N partitioning and transformation within plant-soil-microbe systems, based on a 10-year field experiment (Fig. 1). Additionally, we collect in situ wheat root exudates and analyze their metabolic profiles via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). We assess the taxonomic composition and functional profiles of root-associated microbiota using 16S rRNA and ITS gene amplicon and metagenomic sequencing. We hypothesize that: (1) conservation agriculture amplifies the positive effects of warming on gross N mineralization and nitrification rates, thereby increasing wheat nitrate acquisition; and (2) warming-induced changes in root metabolism profiles (including composition and chemodiversity) affect microbial community composition and functions, accelerating N cycling in conservation agriculture. We find that conservation agriculture under long-term warming increases wheat nitrate uptake by stimulating soil N transformations, with gross mineralization enhanced by 191% and nitrification by 159%, while microbial immobilization decreases by 24%. These shifts are driven by alterations in root primary and secondary metabolites, which restructure microbial functional niches and optimize multiple N-cycling processes, thereby reinforcing the coupling between root metabolism and microbial functions. Together, this study provides field-based evidence that conservation agriculture enhances wheat N acquisition by mitigating plant-microbiome competition under climate warming. This promotes a more efficient C-N exchange, conferring a competitive advantage to wheat in conservation agriculture. Overall, our findings reveal the potential of conservation agriculture to improve crop nutrient acquisition and resilience by strengthening plant-soil-microbe interactions under climate warming.

a Overview of the field experiment with infrared heating systems and in situ 15N labeling plots. b Nitrogen partitioning between wheat plants and microbes using 15N labeling experiment. In situ 15NO3− and 15NH4+ labeling was conducted to quantify plant–microbe N competition. c Soil gross N transformation rates (mineralization and nitrification). The soil gross N transformation rates were determined using a 24-h 15N pool dilution approach. d Plant root exudation and rhizosphere microbiome. Root exudates were collected in situ using a soil-hydroponic-hybrid approach. Root exudates were collected over three consecutive 24-h periods, with syringes replenished with nutrient solution after each collection. The exudates were then filtered through a 0.22 μm Minisart syringe filter and stored at −20 °C. Rhizosphere soil was collected by hand shaking. Microbial community composition was characterized via 16S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS sequencing. Functional potential was assessed through shotgun metagenomic analysis. Some elements of this figure were created in BioRender. Cunkang, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/iyhzlv3.

Results

Conservation agriculture increased wheat nitrate uptake by accelerating soil internal N cycling processes under warming

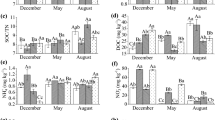

Using 15N-NO3− and 15N-NH4+ in situ labeling, we investigated how warming affected NO3− and NH4+ partitioning between wheat and rhizosphere microorganisms in conservation versus conventional agriculture (Fig. 1). Warming consistently increased NO3− uptake by both wheat and rhizosphere microbes regardless of agricultural management (p < 0.001; Fig. 2a, b), but the magnitude and direction of NO3− uptake were management-specific (Supplementary Table 1). Compared to ambient conditions, warming increased wheat NO3− uptake by 26% in conventional agriculture (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = 7.64, p < 0.001; Fig. 2a) and 40% in conservation agriculture (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = 9.46, p < 0.001; Fig. 2a). The effect size of warming on wheat NO3− uptake, as indicated by Cohen’s d, was 1.24 times greater in conservation agriculture than in conventional agriculture (Cohen’s d = 6.69, 95% CI 2.25–11.1 vs. d = 5.40, 95% CI 1.67–9.13; Supplementary Fig. 1a). In contrast, the effect size of warming on rhizosphere microbial NO3− uptake was 34% smaller in conservation agriculture compared to conventional agriculture (Cohen’s d = 2.83, 95% CI 0.39–5.28 vs. d = 4.28, 95% CI 1.14–7.42; Supplementary Fig. 1b). Warming decreased NH4+ uptake by both plants and microbes compared to ambient conditions (p < 0.01; Fig. 2d, e). Specifically, NH4+ uptake was 59% less for wheat (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = −4.43, p = 0.004, Fig. 2d) and 11% less for rhizosphere microbes (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = −4.01, p = 0.007, Fig. 2e) under warming in conservation agriculture than ambient conditions. In contrast, NH4+ uptake was 46% less for wheat (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = −5.34, p = 0.002, Fig. 2d) and 7% less for rhizosphere microbes (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = −6.05, p < 0.001, Fig. 2e) under warming in conventional agriculture than ambient conditions. Despite warming intensifying N competition between plants and microbes in both agricultural systems (indicated by the ratio of 15N uptake by microbes versus wheat), conservation agriculture mitigated the competition for NO3− by 4.4 times (Cohen’s d = 5.09, 95% CI 1.53–8.66 vs. d = 1.16, 95% CI −0.71–3.03; Supplementary Fig. 1c) and for NH4+ by 1.4 times (Cohen’s d = 4.27, 95% CI 1.14–7.41 vs. d = 3.10, 95% CI 0.53–5.67; Supplementary Fig. 1f) compared to conventional agriculture.

Contribution of 15N-NO3− or 15N-NH4+ to total 15N recovery in wheat and microorganisms (a, b, d, e), ratios of 15N uptake by microorganisms to 15N uptake by wheat (c, f) and soil gross N mineralization rate, gross N nitrification rate, and gross N immobilization rates (g–i). Data are presented as with mean values ± s.e.m. (n = 4 independent soil samples per treatment). Statistical significance between treatments was determined using two-sided Student’s t tests. All reported p values result from two-sided statistical tests. Asterisks indicate significant differences (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0 .05). Micro/wheat recovery 15NO3−: ratio of 15NO3− recovery by microorganisms to that by wheat; Microb/wheat recovery 15NH4+: ratio of 15NH4+ recovery by microorganisms to that by wheat; GMR gross N mineralization rate, GNR gross N nitrification rate, GIR gross N immobilization rates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The 15N isotope dilution technique revealed differential responses of soil gross N transformation rates to warming between conservation and conventional management (Fig. 2g–i). Warming increased both soil gross N mineralization rates (GMR) (two-sided Student’s t test, conventional agriculture: t₆ = 12.5, p < 0.001; conservation agriculture: t₆ = 12.7, p < 0.001, Fig. 2g) and nitrification rates (GNR) (two-sided Student’s t test, conventional agriculture: t₆ = 5.56, p = 0.001; conservation agriculture: t₆ = 6.76, p < 0.001, Fig. 2h) in the wheat rhizosphere, regardless of agricultural management. Compared to conventional agriculture, conservation agriculture exhibited slightly stronger warming effects on GMR (Cohen’s d = 8.83, 95% CI 3.16–14.5 vs. d = 9.00, 95% CI 3.23–14.8; Supplementary Fig. 1g) and GNR (Cohen’s d = 3.93, 95% CI 0.97–6.89 vs. d = 4.78, 95% CI 1.38–8.18; Supplementary Fig. 1h). In addition, gross microbial N immobilization rates (GIR) in the wheat rhizosphere increased under warming in conventional agriculture (two-sided Student’s t test, t₆ = 8.19, p < 0.001, Fig. 2i), but decreased by 24% in conservation agriculture (Fig. 2i). These results suggested that conservation agriculture alleviated plant-microbe competition for N in the rhizosphere, facilitating wheat nitrate acquisition by promoting N production (mineralization and nitrification) while reducing microbial N immobilization.

Management-dependent responses of wheat rhizosphere microbiomes to warming

We determined the responses of rhizosphere microbial communities to warming using DNA sequencing (Figs. 1d and 3). Both bacterial and fungal community compositions were affected by warming, management practice, and their interactions (PERMANOVA, F = 2.11–22.5, p < 0.001; Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 2). Compared to conventional agriculture, the dissimilarity distances for bacterial community structure between ambient and warming conditions were larger in conservation agriculture (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, W = 1538, p = 0.004; Fig. 3a), whereas the fungal community exhibited the opposite pattern (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, W = 2828, p = 0.003; Supplementary Fig. 2a), suggesting that bacterial communities are more sensitive to warming in conventional agriculture.

a Bacterial community composition variation between warming and ambient in two management systems. Bacterial β-diversity was analyzed using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). The effect size of warming on the dissimilarity bacterial community composition was calculated based on the Bray–Curtis distance in two management systems (n = 6 independent soil samples per treatment). Dissimilarity distance indicates the differences in bacterial community structure between warming and ambient in two management systems. The box plots show the median (center line), the 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and the range of non-outlier values (whiskers). Each treatment contains 66 pairwise dissimilarity values calculated from 12 biological replicates. Statistical significance between treatments was determined using two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. b Taxonomic tree showing warming responses of dominant soil bacterial taxa in two management systems. Only ASVs with a significant response (padj < 0.05) to warming are included in the tree. ASVs respond to warming positively (red) and negatively (blue) in conventional and conservation agriculture. The outer colored branches represent the phylum of each ASV. The middle heatmap represents the relative abundance of each ASV. The inner colored pie represents the number of different ASVs, the red pie in the upper part indicates the number of enriched ASVs under warming, and the blue pie indicates the number of depleted ASVs under warming. c, d The random forest model detects bacterial taxa as biomarkers of warming. c The ten-fold cross-validation error rate was calculated to evaluate the performance of the random forest model in classifying rhizosphere bacterial communities under ambient and warmed conditions across both conventional and conservation agriculture systems. The lowest error was achieved using the top 8 most important bacterial families. d The top eight bacterial families contributing most to the classification accuracy are shown in descending order of importance (based on the mean decrease in accuracy). Bar colors represent the corresponding bacterial phyla. Conserv-Amb conservation agriculture without warming, Conserv-Warm conservation agriculture with warming, Conven-Amb conventional agriculture without warming, Conven-Warm conventional agriculture with warming. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Microbial amplicon sequence variant (ASV) enrichment analysis identified fewer significantly altered bacterial ASVs in conservation agriculture than in conventional agriculture, despite greater compositional shifts (Fig. 3b), which indicated that the dissimilarity index reflected greater compositional changes driven by shifts in the relative abundance of dominant taxa rather than changes in the total number of taxa (Fig. 3a, b). To identify key microbial taxa associated with warming, we performed ten-fold cross-validation analysis on the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal families (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 2c). The cross-validation error plateaued when the top eight bacterial families and twenty-one fungal families were included, suggesting these taxa best discriminated warming effects. Accordingly, we defined these groups as biomarker taxa. Among them, the most influential bacterial families were Nitrosomonadaceae, Entotheonellaceae, Pseudonocardiaceae, and Nitrospiraceae (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4a), with well-known roles in nitrification and other N cycling processes. The relative abundances of Nitrosomonadaceae, Entotheonellaceae, and Nitrospiraceae were enriched only in conservation agriculture with warming (two-sided Student’s t test: Nitrosomonadaceae, t₁₀ = 10.2, p < 0.001; Entotheonellaceae, t₁₀ = 6.04, p < 0.001; Nitrospiraceae, t₁₀ = 10.4, p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 4a), while that of Pseudonocardiaceae decreased in response to warming in conventional agriculture (two-sided Student’s t test, Pseudonocardiaceae, t₁₀ = −3.74, p = 0.004; Supplementary Fig. 4a). Among fungi, the most responsive families included Cystobasidiaceae, Filobasidiaceae and Diversisporaceae. Warming significantly increased their relative abundances exclusively under conservation agriculture (two-sided Student’s t test: Cystobasidiaceae, t₁₀ = 2.59, p = 0.027; Filobasidiaceae, t₁₀ = 2.80, p = 0.019; Diversisporaceae, t₁₀ = 3.52, p = 0.005; Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4b).

Warming effects on wheat root metabolite profiles were management-specific

To elucidate the mechanisms of agricultural management effects on the wheat rhizosphere microbial community and soil N transformation in response to warming, we collected wheat root exudates at the jointing stage following the method of Phillips et al.37 and analyzed using LC-MS. A total of 10,696 peaks were detected across all samples, resulting in the identification of 609 compounds (Supplementary Data 1). Principal coordinates analysis revealed distinct metabolite profiles among treatments (p < 0.001, Fig. 4a). The interaction between management × warming on root exudate profiles was significant (PERMANOVA, F = 17.0, p < 0.001; Fig. 4a), suggesting that warming effects were management-dependent. The root exudation rate increased only under warming in conservation agriculture (p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 5b). Warming reduced the chemodiversity of wheat root metabolites in conservation agriculture, while increasing it in conventional agriculture (p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 5c).

a Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the wheat root metabolites composition based on Bray–Curtis distances for all samples. The effects of management, warming, and their interactions on metabolism profile dissimilarity were tested using the Adonis function of PERMANOVA (n = 6 independent soil samples per treatment). b The effect size of warming on major categories of wheat root metabolites in two management systems. Estimated effect sizes are regression coefficients based on rescaled response attributes in the linear mixed-effects models (LMMs, two-sided test, n = 6 independent soil samples per treatment). Data are presented with mean values ± s.e.m. Asterisks indicate significant differences (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0 .05). The box plots show the median (center line), the 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and the range of non-outlier values (whiskers). c, d Responses of individual molecules of wheat root metabolites categories to warming in conventional agriculture and conservation agriculture. The inner circle denotes various classifications of metabolites. Scatter points in the outer circle represent the response of individual exudate molecules to warming, with red indicating significant changes (p < 0.05) and green denoting insignificance. Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided Student’s t tests with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons. The outermost heatmap shows the log-transformed relative abundances of wheat root exudate molecules under ambient and warmed conditions. Conserv-Amb conservation agriculture without warming, Conserv-Warm conservation agriculture with warming, Conven-Amb conventional agriculture without warming, Conven-Warm conventional agriculture with warming. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We classified 282 identified compounds into seven categories based on their chemical nature from 609 compounds: alcohols, amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty acyls, flavonoids, organic acids, phenols, and terpenes (Supplementary Data 1). Warming increased the abundance of carbohydrates, phenols, flavonoids, and terpenes, and reduced the abundance of alcohols, amino acids, and organic acids across both management practices (linear mixed-effects model, Fig. 4b; two-sided paired t-test, for detailed statistics, see Supplementary Table 3). However, the magnitude of warming effects varied among different metabolite categories across management systems. The negative effect size of warming on amino acids was 13.2% greater in conservation agriculture than in conventional agriculture (two-sided test; t10 = −2.12, p = 0.016, Fig. 4b). In contrast, the positive warming effect on carbohydrates was 1.5 times greater in conservation agriculture (two-sided test; t10 = 12.6, p < 0.001, Fig. 4b). Conversely, a stronger positive warming effect on secondary metabolites, including phenols, terpenes and flavonoids, was observed in conventional agriculture compared to conservation agriculture (linear mixed-effects model, Fig. 4b; two-sided paired t-test, for detailed statistics, see Supplementary Table 3). At the individual metabolite level, we observed strong, divergent responses to warming between conservation and conventional agriculture (Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Fig. 5d). To identify key metabolites contributing to these management-dependent responses, we performed Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) on the full set of identified metabolites. There were distinct clustering patterns for core metabolites, predominantly amino acids, organic acids, and carbohydrates, between conservation and conventional agriculture (Supplementary Fig. 5d).

Warming accelerated microbe-mediated nitrate production and decreased wheat rhizosphere’s nitrate consumption in conservation agriculture

We carried out shotgun metagenomic sequencing to determine microbial functional capacities and metabolic pathways in the wheat rhizosphere (Fig. 5). Enrichment analysis based on KEGG pathways revealed distinct functional profiles between warming and ambient conditions in both conservation and conventional agriculture (Fig. 5a). The Metabolism pathway was the dominant functional category under warming, while the Organismal Systems pathway was dominant under ambient conditions (Fig. 5a, b). The number of KEGG Orthologs (KOs) enriched in the Metabolism pathway was greater under warming in conservation agriculture compared to conventional agriculture (Supplementary Fig. 6). This pattern was particularly evident in N metabolism, where the relative abundance of N-related metabolic pathways increased under warming across both agricultural systems (Fig. 5a, b). Genes associated with N mineralization (GudB_rocG and ureC) and nitrification (amoA, amoB, amoC and HAO) exhibited increased relative abundances in the wheat rhizosphere under warming in conservation agriculture (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 7, for detailed statistics, see Supplementary Table 4). Conversely, the relative abundance of genes associated with NO3− consumption was reduced under warming in conservation agriculture (two-sided t-tests; Denitrification, t10 = −3.942, p = 0.002; N assimilation, t10 = −7.69, p < 0.001; ANRA, t10 = −3.91, p = 0.003; DNRA, t10 = −3.40, p = 0.007, Fig. 5c). Among them, the relative abundance of genes associated with assimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (ANRA) and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA), such as nasA, nasB, nirB, narH and nirB, decreased under warming in conservation agriculture (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 7, for detailed statistics, see Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, microbial genes associated with N assimilation, including gltB and CS_gltA, decreased only in conservation agriculture (p < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 7, for detailed statistics, see Supplementary Table 4). These findings suggest that warming increased the relative abundance of the microbial genes in the wheat rhizosphere associated with N production while reducing nitrate consumption in conservation agriculture, potentially accelerating soil internal N processes.

KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed metabolic pathways in warming (a) and ambient conditions (b). The differential metabolic functions were performed using the empirical Bayes techniques on level 3 of the KEGG metabolic pathway. c Effects of management and warming on the relative abundance of N cycling related genes. The abundance of each gene was normalized to transcript per million (TPM), based on the gene length and sequencing depth. Data are presented with mean values ± s.e.m. (n = 6 independent soil samples per treatment). Statistical significance between treatments was determined using two-sided Student’s t tests. The box plots show the median (center line), the 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and the range of non-outlier values (whiskers) (n = 6 independent soil samples per treatment). Significances are denoted by asterisks: ***p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. d Sankey diagram showing the difference in the contributions of microbial groups to N metabolic process under warming and agricultural managements. The three columns indicate, from left to right, the four treatments, the contribution of each taxonomic group to the metabolic function, and the contribution of the N cycle, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To provide further insights into the functional capacity of microbial communities in the wheat rhizosphere under warming and management, we assembled and binned 106 Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) with >50% completeness and <10% contamination (Supplementary Fig. 8a and Supplementary Data 2). Most of the genomes were classified within the phyla Actinobacteria, Thermoproteota, or Proteobacteria (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 8b). N assimilation and mineralization genes were predominantly encoded by MAGs from Actinobacteriota, Thermoproteota, and Proteobacteria, consistent with decreased relative abundance of Actinobacteriota and increased relative abundance of Proteobacteria under warming in conservation agriculture (Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, nitrification marker genes were found in Thermoproteota, Proteobacteria, Nitrospirota, Chloroflexota and Actinobacteriota phyla (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

To assess the contribution of different microbial taxa to metabolic pathways, we calculated community-level metabolic weight scores (MW-scores), where a higher MW score indicates a greater contribution of a specific pathway to the community-level metabolic profiles. Both ammonia oxidation and nitrate reduction pathways contributed significantly to the microbial community-level metabolic profiles (Supplementary Fig. 8b). The percentage contribution of microbial taxa showed that nitrification was predominantly driven by Thermoproteota, Desulfobacterota, Nitrospirota, and Actinobacteria (Fig. 5d). The higher percentage contributions of these taxa in conservation agriculture under warming might explain more rapid NO3− production in this system. These observations were consistent with our findings that conservation agriculture under warming increased the relative abundance of Nitrososphaeraceae and Nitrospirota (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, enhanced metabolic contributions from Proteobacteria to nitrate reduction were common in conventional agriculture under warming, corresponding to their greater NO3− consumption.

Wheat root metabolites affected rhizosphere microbial-mediated N cycling in conservation practice under warming

To investigate the effects of wheat root metabolism on the rhizosphere microbiome, we established a multi-omic framework to explore the potential plant-microbe interactions within each agricultural management system. Bipartite network analysis showed a 129% increase in positive connections between root metabolites and microbes in conservation agriculture compared to conventional agriculture (Fig. 6a, b), revealing increased plant-microbe interactions in response to warming. Further analysis of taxa-metabolites subnetworks showed bacteria exhibited stronger correlations with root metabolites than fungi, as bacterial connectivity was 143% higher than fungal connectivity in conventional agriculture and 96% higher than fungal connectivity in conservation agriculture. This finding is further supported by a metabolite-wide association analysis, revealing a stronger association between bacteria and core metabolites, particularly nitrifying bacteria (Spearman correlation; Supplementary Fig. 9). N cycling-related microbes, including Nitrosomonadaceae, Nitrospiraceae, and Pseudonocardiaceae, accounted for more than 56% of the connectivity with metabolites in conservation agriculture (Fig. 6c, e). Amino acids had a predominantly negative correlation with nitrifying bacteria (B6: Nitrosomonadaceae, B5: Nitrospiraceae), while organic acids and terpenes showed positive correlations with nitrifying bacteria but negative correlations with denitrifying bacteria (B3: Pseudonocardiaceae). In conventional agriculture, these bacteria exhibited markedly lower connectivity with root exudates, with only 23% of that observed in conservation agriculture (Fig. 6c, e). Fungal connectivity with root metabolites also increased in conservation agriculture. Symbiotic fungi such as Diversisporaceae and Filobasidiaceae (F8, F9) were more frequently linked to organic acids in conservation systems (Fig. 6f), whereas in conventional agriculture, connections were more common with saprotrophic families like Strophariaceae and Sporidiobolaceae (F2, F3; Fig. 6d). Consistent with the results of the microbial taxa-metabolite network, the connectivity of KEGG pathway KO-metabolite and N cycling gene-metabolite networks was also higher in conservation agriculture than in conventional agriculture, with an average increase of 52% and 55%, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 10–12).

a, b Bipartite networks visualizing the interactions between individual molecules of root metabolite and rhizosphere microorganisms (genus level) in each management system. The orange nodes represent bacterial genera, the green nodes represent fungal genera; and nodes of other colors depict different categories of root metabolites. The edges represent significant Spearman correlations (|ρ| > 0.6, p < 0.05, two-sided test). Subnetworks extracted from the main network illustrate the interactions between different categories of root metabolites and bacterial (c, e) and fungal (d, f) biomarker families. Each category of root metabolites is depicted with unique colors. The size of each node corresponds to the number of connections between each microorganism or root metabolite. The thickness of connecting edges between root metabolites and microorganisms indicates the number of observed connections, with thicker lines representing a higher number of significant connections. Red edges indicate predominantly positive correlations (where positive correlations account for over 50% of the total), while blue edges denote mainly negative correlations (where positive correlations account for less than 50% of the total). g, h Effects of root metabolism quantity and quality on N cycling related genes using Redundancy analysis (RDA) analysis. PCoA1 and PCoA2 represent root metabolism compositional changes; the Shannon index indicates root metabolism chemodiversity; specific root exudation rates (TOC, mg C g−1 root biomass h−1), and different categories of root exudates. **p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (two-sided, unrestricted permutation test, n = 999). i Contribution of root metabolism quantity and quality to six classes of N cycling genes in assimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (ANRA), dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA), denitrification, nitrification, N mineralization, and assimilation using Random Forest analysis. PCoA1 and PCoA2 represent root metabolism compositional changes; the Shannon index indicates root metabolism chemodiversity; specific root exudation rates (TOC, mg C g−1 root biomass h−1). Statistical significance of predictor importance was assessed using Random Forest with permutation tests (two-sided, 1000 permutations, ntree = 2000). Reported p values are exact values without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Yellow bars represent factors significant at p < 0.05, and the dark gray column indicates the factor that has no significant effect. ***p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Wheat root metabolism, including the metabolic composition, chemodiversity, and specific root exudation rate, explained 71% of the variation in the composition of N cycling genes (Fig. 6g, h). In the N cycling gene-metabolite networks, organic acids, amino acids, and terpenes collectively accounted for more than half of all root exudate connections, contributing 32%, 26%, and 12%, respectively, to the correlations with N cycling genes in conservation agriculture (Supplementary Fig. 12). Primary metabolites, such as carbohydrates, amino acids, and organic acids, had minimal influence on nitrate reduction processes (e.g., DNRA and denitrification; Fig. 6i), but were crucial for energy-extensive processes, such as nitrification, mineralization, and microbial N immobilization (Spearman correlation, r = 0.77–0.93, p < 0.05; Fig. 6i and Supplementary Fig. 13). In contrast, secondary metabolites such as terpenes and flavonoids were significantly associated with microbial N-cycling taxa and functional genes (Spearman correlation, r = 0.62–0.88, p < 0.05; Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 13). Random forest analysis identified terpenes as key predictor for most N processes except denitrification, while flavonoids were specifically predictive of gross mineralization and microbial N assimilation (Fig. 6i). Metabolic chemodiversity influenced DNRA processes, while changes in root exudate composition significantly impacted organic N mineralization and N immobilization (p < 0.05; Fig. 6i). Collectively, our multi-omics analyses revealed that compositional changes in wheat root exudates modulated rhizosphere microbial functional niches in conservation agriculture, resulting in the selective recruitment and activation of N-cycling-related microorganisms and metabolic functions, thereby enhancing N cycling efficiency.

Discussion

Understanding how plant-microbe interactions adapt to climate change is crucial for designing agricultural strategies that promote plant growth and resilience, supporting sustainable agriculture. Plant selection and agricultural practices jointly shape rhizosphere microbial communities33,36,38. But, we do not know how the interaction of agricultural management and climate warming will affect the plant-soil-microbe nexus and feedback to crop nutrient acquisition. Here, we provide empirical evidence that conservation agriculture alleviated N competition between wheat and rhizosphere microorganisms under warming conditions, favoring plant nitrate acquisition by optimizing soil internal N transformations through changes in the quality of wheat root metabolites, in contrast to conventional agriculture (Fig. 7). These findings suggest that long-term conservation agricultural management promotes functionally targeted modulation of crop rhizosphere microbiomes under warming, offering a pathway for more efficient nutrient management in cropping systems under climate change.

To evaluate partitioning and mutualistic interactions between wheat and soil microorganisms under warming, we investigated 15N redistribution between wheat and soil microorganisms and soil gross N transformation. The results show that conservation agriculture management alleviated N competition between wheat and soil microorganisms and favored plant nitrate acquisition by accelerating soil internal N transformations through changes in root metabolites quality compared to conventional agriculture under warming. The red arrow indicates increased microbial-mediated N processes following warming, and the blue arrow indicates reduced processes. The green and yellow lines represent N partitioning between plants and microorganisms and gross N transformation rates in conventional and conservation agriculture, respectively. GMR gross N mineralization rate, GNR gross N nitrification rate, GIR gross N immobilization rate. Some elements of this figure were created in BioRender. Cunkang, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/atwc0kv.

Nitrogen is a key limiting factor for crop productivity, and warming typically increases the N demand of both plants and microorganisms, thereby intensifying plant-microbe competition for N and reducing crop N use efficiency22,39. Compared to conventional agriculture, conservation agriculture mitigated the warming-induced intensification of plant-microbe N competition and facilitated wheat nitrate acquisition (Fig. 2). These findings are supported by our previous multi-year study at the same site, which showed that conservation agriculture under warming led to a 9.3% increase in wheat yield10, consistent with improved N acquisition observed in the present study. Since root biomass (d.w.) was similar across both agricultural systems under warming (Supplementary Fig. 5a), we attribute the differences in wheat N acquisition to microbial processes, rather than direct plant effects. Elevated gross N mineralization rates under warming were observed in both management systems (Fig. 2), as organic N mineralization is the primary source of mineral N for plant uptake25,40. In conservation agriculture, increased gross nitrification rates under warming were more pronounced, aligning with elevated wheat nitrate uptake and accounting for over 80% of total inorganic N uptake (Fig. 2). However, the uptake of NH4+ by wheat decreased (Fig. 2), suggesting that NH4+ was not directly absorbed by wheat but rather oxidized to nitrate by nitrifying microbes. Given that wheat preferentially utilizes NO₃⁻ over NH₄⁺ as a N source, this shift in soil N form may confer a physiological advantage for plant uptake41,42. Although high NH₄⁺ supply is known to induce toxicity symptoms by disrupting K⁺ uptake41, we did not observe visible stress indicators such as chlorosis or growth inhibition in wheat in the field. Thus, the increased NO₃⁻ acquisition under warming is more likely attributed to wheat’s intrinsic nitrate preference than to K⁺-mediated mitigation of NH₄⁺ toxicity. Supporting this interpretation, a previous 15N labeling experiment showed that N acquisition was enhanced in a nitrate-favoring crop (cucumber) when nitrification outpaced mineralization42. Overall, we observed that a faster gross nitrification rate in conservation agriculture under warming played a critical role in facilitating wheat nitrate uptake, emphasizing the importance of regulating N cycling processes to support crop nutrient uptake.

The increased rhizosphere gross mineralization and nitrification rates under conservation agriculture with warming were primarily associated with intensified root–microbe interactions, driven by increased rhizosphere carbon inputs (Figs. 4, 6 and Supplementary Fig. 5b). This also corresponded to the changes in microbial communities and functional potentials (Figs. 3 and 5). Conservation agriculture increased root exudation under warming conditions (Supplementary Fig. 5b), providing a continuous and labile carbon source that supports not only microbial growth but also the recruitment and activation of nitrifying taxa such as Nitrosomonadaceae and Nitrospiraceae (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2), which contributed to increased nitrification processes43,44. Concurrently, warming increased the abundance of microbial genes associated with N mineralization and nitrification, with more pronounced effects in conservation agriculture (p < 0.01, Fig. 5c). The relative abundance of symbiotic fungi (e.g., Diversisporaceae) also increased in conservation agriculture with warming (Supplementary Fig. 4b), potentially contributing to improved nutrient mobilization by enhancing phosphate solubilization and organic N turnover through symbiotic associations with roots22. These biological responses were particularly pronounced under conservation management, suggesting that microbial taxa and functions respond to warming in a management-dependent manner. Besides the observed intensified root–microbe interactions, the distinct warming effects on gross mineralization and nitrification between conventional and conservation agriculture can also be attributed to differences in the altered soil physicochemical environment. Conservation practices—such as residue retention and no-tillage—can alter the soil physicochemical environment by increasing soil organic carbon, enhancing water retention, and moderating temperature fluctuations10,11,12,13. Long-term monitoring at our site confirmed that soils in conservation agriculture remained wetter (17.1% vs. 15.9%) and had higher SOC levels under warming compared to conventional agriculture10,12. These shifts likely increased microbial activity, improved substrate availability, and stabilized redox conditions—factors that collectively promote N cycling17,25,26,27,30. Conversely, in conventional agriculture, reduced soil moisture under warming may exacerbate microbial water stress, thereby suppressing nitrifier activity and gene expression, and limiting microbial recruitment and functional responses30,45,46. This interpretation aligns with previous studies showing that moisture limitations can offset the positive effects of warming on net mineralization and nitrification17,26. Thus, the increased N transformation observed in conservation agriculture with warming is not solely the result of biological mechanisms such as microbial recruitment, but is also facilitated by long-term improvements in the soil physicochemical environment. Disentangling their relative contributions will require targeted experiments—such as greenhouse or microcosm studies—where plant inputs and soil variables can be independently manipulated. In addition to enhanced mineral N provision, conservation agriculture also modulated warming effects on microbial N consumption, providing wheat a competitive advantage for nitrate acquisition (Figs. 2 and 5). Warming increased microbial N immobilization in conventional agriculture (Fig. 2i), likely due to the stimulation of microbial population growth at higher temperatures27,40,47. Conversely, conservation agriculture decreased microbial N immobilization by 24% under warming (Fig. 2i), likely due to increased NH₄⁺ competition from nitrifiers. This interpretation is supported by our ¹⁵N labeling data, which show that microbial NH₄⁺ immobilization accounted for more than 70% of total N immobilization (Fig. 2). Since ammonium is generally the preferred substrate for microbial immobilization48, its preferential oxidized by nitrifiers under warming could suppress immobilization processes and increase nitrate availability for plants. Furthermore, organic matter inputs from crop residue retention and increased quantities of root exudates in conservation agriculture reduce microbial reliance on inorganic N immobilization for survival49,50. As wheat has a strong preference for nitrate, microbial nitrate-reduction processes, including denitrification, DNRA, and ANRA, emerge as key metabolic pathways in N competition51. Metagenomic analysis revealed that warming decreased the relative abundance of genes involved in DNRA (narH, nirB) and ANRA (nasA, nasB) under conservation agriculture (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 7). These results, taken together with increased nitrification, point to a coordinated microbial shift that favors rhizospheric nitrate accumulation, thereby facilitating wheat N acquisition under warming conditions. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, as metagenomic data reflect gene abundance rather than transcriptional activity, potentially overestimating microbial functional expression by including inactive or dormant taxa52. Future research incorporating metatranscriptomics is needed to validate these functional shifts at the biochemical level53. Additionally, the apparent optimization of microbial N cycling may involve trade-offs with other microbial functions that underpin long-term ecosystem resilience, such as carbon stabilization, pathogen suppression, or stress tolerance10,11,18. Although our results suggest that conservation agriculture increased N acquisition without compromising crop yield or microbial diversity10, the long-term consequences for ecosystem stability and multifunctionality remain uncertain.

Understanding the interactions between root metabolites and rhizosphere microbiome is crucial for elucidating belowground biochemical processes and plant nutrient acquisition54,55,56,57. This study presents multiple lines of evidence that management-induced changes in root exudate composition have cascading effects on rhizosphere microbial communities, metabolic functions, and soil N cycling processes (Supplementary Table 5). The responses of the wheat metabolite profile to warming were management-dependent (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5), and changes in root exudate composition prompted changes in microbial composition and functional profiles (Supplementary Tables 2 and 5), particularly in conservation agriculture (Fig. 6a–f and Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). This finding aligns with the developing understanding of the interactive effects of host plants and agricultural management in shaping rhizosphere microbial communities and functions33,36,58. The population of nitrifying bacteria (e.g., Nitrospiraceae and Nitrosomonadaceae) was larger in conservation agriculture under warming compared to conventional agriculture, and these bacteria exhibited the strongest interactions with root metabolites. In contrast, these bacteria showed weaker associations with root metabolism and their relative abundances remained unchanged under warming in conventional agriculture (Fig. 6a–e and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Since most N transformations are energy-intensive microbiological processes, increased root exudation under warming in conservation agriculture (Supplementary Fig. 5b) likely promoted microbial activity related to N cycling. KEGG pathway-enrichment analysis confirmed that warming enriched microbial energy and N metabolism pathways (Fig. 5a), which were closely associated with root exudate profiles in conservation agriculture (Supplementary Fig. 11b). This is consistent with the increased release of primary metabolites under warming, including carbohydrates, which are key carbon sources for microorganisms and have strong correlations with N cycling-related microbial taxa and genes (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 13)59. Although amino acids, another class of primary metabolites, can provide readily available C and N sources for microorganisms involved in nitrification and denitrification59, our findings revealed a negative correlation between amino acids and nitrifying bacteria in conservation agriculture, especially Nitrospira (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10) involved in complete ammonia oxidation60. This aligns with previous research reporting that amino acids released by plants inhibited nitrification genes (amoA) in rhizosphere soil61. Consequently, reduced amino acid (and, therefore, amino-N) release may represent a N preservation strategy under N-limited conditions, as observed in various crops including maize62, barley63, switchgrass64, Brassica napus65, and tea61. Therefore, we hypothesize that under conditions that intensify competition for N, plants can moderate amino acid release in rhizoexudates limit organic N loss via this pathway and foster niches favoring microbes beneficial for plant N acquisition. In addition to primary metabolites, secondary metabolites—including terpenoids and flavonoids—are increasingly recognized for their roles in shaping microbial community composition and function. Terpenoids can act as signaling molecules or antimicrobials66 and were strongly correlated with N cycling genes in our study (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). Flavonoids also showed relevant associations; prior research demonstrated that root-derived flavonoid enriched Oxalobacteraceae, thereby promoting plant N acquisition under N-deprived conditions56. Consistently, our data showed a positive association between flavonoids and genes involved in N mineralization (Fig. 6i and Supplementary Fig. 13). Unlike bacteria, which interact with a broad array of root metabolites due to their metabolic flexibility and saprotrophic capabilities, symbiotic fungi such as Diversisporaceae exhibited stronger associations specifically with organic acids (Fig. 6f). Organic acids not only provide carbon, but also act as carboxylate ligands that mobilize inorganic phosphate and serve as host-derived signals for mycorrhizal establishment59,67, explaining their dominance in the fungal subnetworks (Fig. 6f). Collectively, the combined effects of agricultural practices and climate warming on both primary and secondary root metabolites led to changes in the structure and functions of rhizosphere microbial communities, reshaping soil internal N transformations and thus facilitating the plants to outcompete soil microbes for N. This study was conducted at the jointing stage of winter wheat, a period of peak root activity and nutrient demand. While this timing captures maximal plant–microbe interactions, it limits insights into temporal dynamics across the growing season. Furthermore, although our findings are derived from a well-characterized wheat–maize rotation system in the North China Plain, they are geographically confined to calcareous silty loam soils under a temperate monsoonal climate. Given that root exudation patterns and microbial responses vary by crop species, growth stages, and environmental conditions, future research should explore whether the observed mechanisms hold across different crops, growth stages, and agroecosystems.

Our findings have important implications for fine-tuning strategies to sustain the production of globally important staple crops in the face of climate change by improving N use efficiency. While substantial research has explored how non-crop plants modulate root metabolism to enhance beneficial interactions with microorganisms for nutrient acquisition, most of these studies were conducted under axenic or monoxenic conditions in vitro24. We highlight three major outputs of our study: Firstly, our study suggests that conservation agriculture represents a robust management strategy for selecting soil microorganisms that meet crop N demands, particularly under warming scenarios where N competition between plants and microbes is intensified. By moderating plant-microbe interactions and optimizing soil internal N cycling, conservation agriculture improves crop N use efficiency and reduces reliance on synthetic N fertilizers, thereby minimizing N losses to the environment through leaching and greenhouse gas emissions68,69,70. However, the ecological consequences of such enhanced N availability require further consideration. While increased NO₃⁻ accumulation benefits plant uptake, it may also elevate the risk of N losses via leaching or N₂O emissions—particularly when there is poor synchrony between plant N demand and microbial N turnover. These potential trade-offs highlight the need to balance N use efficiency with environmental sustainability in management strategies. Secondly, our findings emphasize the importance of root metabolites as a key mediator in the plant-soil-microbe nexus, suggesting that optimizing root exudate production could offer promising opportunities for breeding crop varieties that select for beneficial microbes71. Thirdly, our research provides a comprehensive validation of the plant-soil-microbe continuum, encompassing crop root metabolism, rhizosphere microbial communities, microbial functionality, ecological processes, crop nutrient uptake, and management within in situ field experiments. While previous studies have primarily focused on the effects of agricultural practices on the rhizosphere microbiome, functional outcomes and biochemical processes within these systems are often only inferred retrospectively. Our study, therefore, provides actionable insights that can guide the development of nature-based solutions for building resilient and sustainable agricultural systems in the face of climate challenges. However, translating these ecological insights into practice will require socioeconomic evaluations—such as cost–benefit analyses—to ensure that conservation agriculture is not only environmentally beneficial but also economically viable, especially in resource-limited regions.

In summary, our study elucidated the plant-soil-microbe interactions underlying wheat nitrate acquisition under warming conditions and demonstrated the potential for positive management through conservation agriculture. Changes in root exudate quality in conservation agriculture reshaped microbial functional niches in the wheat rhizosphere, accelerating soil N internal cycling by amplifying the positive effects of warming on gross N mineralization and nitrification rates, while simultaneously reducing microbial N immobilization and nitrate reduction. It mitigated warming-intensified competition for N between wheat and soil microorganisms, facilitating plant N acquisition in conservation agriculture with warming. Our findings provide a comprehensive understanding of how host plants regulate rhizosphere microbial communities and metabolic functions by altering root exudate metabolite profiles, and how these processes are shaped by agricultural management practices. This knowledge could serve as the foundation for developing nature-based solutions to ensure sustainable agriculture in the face of climate warming. Ultimately, our research suggests that manipulating plant-soil-microbe interactions through conservation agricultural management holds great potential for crop production capable of withstanding the challenges posed by climate change.

Methods

Experimental site and design

A long-term field experiment was established in 2010 at the Yucheng Comprehensive Experiment Station (36°51′N, 116°34′E), operated by the Chinese Academy of Science (Fig. 1a). The site employs a double-cropped winter-wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)–summer-maize (Zea mays L.) rotation. Winter wheat is typically sown in early October and harvested in early June, followed by summer maize, which is planted in June and harvested in late September. The experimental design consisted of four treatments arranged in a randomized complete block design, with four replicates per treatment: conservation agriculture (no tillage and crop residues retained) with and without warming (Conserv-Amb, Conserv-Warm) and conventional agriculture (regular tillage and crop residues removed) with and without warming (Conven-Amb, Conven-Warm). Experimental warming was applied continuously via MSR-2420 infrared heaters (Kalglo Electronics, Bethlehem, PA) suspended approximately 3 m above the ground to achieve a surface soil warming of 2 °C, in line with projections for northern China under IPCC climate scenarios72. Control plots had identical “dummy” heaters to simulate shading and wind-flow effects. Plots are separated by 5 m, and the plots are separated by at least 10 meters, so as to avoid the infrared radiator from heating the control plots. Soil surface temperature was monitored at 5 cm depth using PT100 thermocouples, confirming a consistent temperature elevation of +2 ± 0.2 °C in warmed plots. Detailed site characteristics and heater calibration procedures are given in ref. 73. The region has a temperate semi-arid climate, characterized by an annual mean temperature of 13.1 °C, and an annual mean precipitation of 561 mm. The soil at the site is classified as a Calcaric Fluvisol according to the FAO-UNESCO system, with a silt loam texture consisting of 12% sand, 66% silt, 22% clay, and a mean pH of 7.1.

In situ 15N labeling experiment

To investigate N partitioning between wheat plants and soil microorganisms for NO3− and NH4+, three 10 × 20 cm subplots were established randomly within each plot to represent the three 15N labeling treatments: 15NO3− (as NH415NO3, 98.2 atom% 15N), 15NH4+ (as 15NH4NO3, 98.4 atom% 15N) and the control without 15N (as ultrapure water). Each subplot was further divided into eight 5 × 5 cm quadrats. At the center of each quadrat, 3 mL of the ¹⁵N tracer solution was injected into the soil at a depth of 7 cm to ensure uniform distribution (Fig. 1a, b). This application rate corresponded to 15 μg 15N per gram of dry weight (d.w.) of soil. Labeling was conducted in situ during the wheat jointing stage (Feekes GS6; Zadoks GS31), which coincides with vigorous vegetative growth, peak N demand, and maximum root–microbe interactions74. All in situ measurements in this study—including N uptake, soil N transformation rates, rhizosphere microbial profiling, and root metabolite exudation—were conducted at this stage to ensure comparability and capture the most active phase of nutrient and microbial dynamics. To avoid diffusion of the 15N-labeled solution, each subplot was isolated by steel plates inserted up to a depth of 15 cm because most roots were concentrated at this depth73. Wheat biomass (root and shoot) and rhizosphere soils were sampled destructively within 3 h following injection of the 15N-labeled solution, which is the period of most rapid mineral N uptake75. First, all wheat shoots in each plot were clipped at the soil surface. Intact soil cores containing roots in each subplot were then collected to a depth of 15 cm. Visible roots were carefully separated from the soil core, immediately submerged in a 0.5 mM HCl solution for 30 min, and then washed with deionized water to remove 15N and inorganic carbon from the root surface. The soil samples were immediately transported to the laboratory and sieved through a 2 mm mesh to determine the microbial N acquisition.

The roots and shoots were oven-dried at 105 °C for 30 min and then at 80 °C for 48 h to determine d.w. plant biomass (g). The dried plant tissues were ground to a fine powder using a ball mill (MM200, Retsch, Germany) and weighed into tin capsules for the measurements of N content and 15N/14N ratios using isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS, MAT 253, Finnigan MAT, Germany). The 15N uptake by wheat was measured as atom percent (atom%) excess (APE) in dried plant tissues. The contribution of specific N forms (15NH4+, and 15NO3−) to wheat N uptake and 15N recovery was calculated according to ref. 76:

where APE (%) is the APE of the 15N in the wheat roots and shoots; At%labeled and

At%control are the atom% of 15N in the wheat in the 15N-labeled treatment and the unlabeled treatment (control), respectively; 15NUplant is the amount of 15N in the wheat tissues (μg) calculated as the sum of 15N in the root and shoots; Biomass (g) is the dry weight of the roots and shoots; N content (g N g−1) is the N concentration of wheat roots and shoots; APE% is the APE of the wheat roots and shoots; and Nplant contribution is wheat N uptake and Plantre is 15N recovery. Total N uptake was calculated as the sum of the uptake of NH4+ and NO3− (15NH4+Uplant and 15NO3− Uplant). The contributions of 15NH4+ or 15NO3− to plant N uptake (Nplant contribution) were calculated using the ratio of NO3− or NH4+ to total N uptake. Plant 15N recovery (Microbere) was determined using Eq. (5).

Microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) was measured using chloroform fumigation extraction according to ref. 77. In brief, fresh soils were fumigated with chloroform for 24 h and then immediately extracted with 0.05 mol L−1 K2SO4. An additional fresh soil sample of the same weight was not fumigated and immediately extracted with K2SO4 solution. The K2SO4 extracts with and without fumigation were immediately freeze-dried for analysis of N content and the 15N/14N ratios IRMS. The contribution of specific N forms (15NH4+ or 15NO3−) to microbial N uptake and 15N recovery was calculated according to ref. 76:

where 15NUmicrobe is the 15N uptake by microorganisms calculated as the difference in the mass of 15N in the MBN between fumigated and nonfumigated soil; APEF and APENF are the APE of total dissolved organic N (TDN) in fumigated soil and nonfumigated soil, respectively; MF (mg N) and MNF (mg N) are the total amount of TDN in fumigated soil and nonfumigated soil on a d.w. basis, respectively; 15NUmicrobe total is sum of the microbial uptake of NH4+ and NO3− (15NH4+Umicro and 15NO3− Umicro). The contributions of 15NH4+ or 15NO3− to microbial N uptake were calculated as the ratio of NO3− or NH4+ uptake to total N uptake. Microbial 15N recovery (Microbere) was determined using Eq. (9).

Competition between wheat and soil microorganisms for N uptake (Ncom) was calculated as the ratio of 15N recovery by microorganisms (Microbere) to that by wheat (Plantre):

Soil gross N transformation

Gross mineralization rates and gross nitrification rates were measured according to ref. 78. Soil sampling was conducted at the jointing stage of winter wheat (Feekes GS6, Zadoks GS31), coinciding with the in situ 15N labeling experiment. Rhizosphere soil samples were collected from the control subplots (without 15N), using the root-shaking technique before root exudates collection. The soil samples were divided into five portions (Fig. 1c); two portions were labeled using a (15NH4)2SO4 solution (5.20 atom%), and the other two portions were labeled using a K15NO3 solution (5.14 atom%), at a rate of 1.42 μmol N g−1 dry soil. Mineral N was extracted from half of the 15N-labeled soils after 0.5 h and the other half after 24 h using a 2 M KCl solution. NH4+ and NO3− concentrations and 15N contents (atom %) were measured using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL III Elemental Analyzer, Elementar) and an IRMS (MAT 253, Finnigan MAT, Germany), respectively. The remaining soil was stored in an −80 °C freezer for DNA extraction.

Gross N mineralization was calculated as:

where m is the mineralization rate (mg N kg−1 h−1); t is the incubation time; M0 is the initial N pool of NH4+ (mg N kg−1); M1 is the post-incubation N pool of NH4+ (mg N kg−1) at time t; AP0 is the initial atom% 15N of NH4+; and AP1 is the post-incubation atom% 15N of NH4+ at time t.

Gross nitrification was calculated as:

where n is the nitrification rate (mg N kg−1 h−1); t is the incubation time; N0 is the initial N pool of NO3− (mg N kg−1); N1 is the post-incubation N pool of NO3− (mg N kg−1) at time t; NP0 is the initial atom% 15N of NO3−; and NP1 is the post-incubation atom% 15N of NO3− at time t.

In situ collection of wheat root metabolites and analysis

Root metabolites were collected using a modified in situ static culture method according to ref. 37. In brief, six wheat plants with uniform growth were selected from each plot. Fine roots (<2 mm in diameter) were carefully excavated from the 0–15 cm soil layer. To ensure physiological vitality, only roots exhibiting a healthy white/yellow coloration and elastic texture were selected. After gently rinsing with sterile deionized water to remove adhering soil particles, roots were inserted into sterile 50-mL polypropylene syringes (Jiangsu Kangyou Medical Instruments Co., Ltd., China), either along their natural growth orientation or at a 45° angle. Syringes were preloaded with sterile glass wool and glass beads to simulate soil particle structure and maintain mechanical conditions. Critically, only the fine roots were enclosed within the syringes, while above-ground tissues (stems and leaves) remained fully exposed to ambient light and air, ensuring uninterrupted photosynthesis and respiration. To sustain root metabolism, syringes were supplied with a sterile, carbon-free nutrient solution (0.1 mM KH₂PO₄, 0.2 mM K₂SO₄, 0.2 mM MgSO₄, and 0.3 mM CaCl₂). Control syringes (without roots) were prepared identically to account for background compounds. Syringes were sealed to prevent contamination and wrapped with moist tissue and aluminum foil to maintain humidity (>90%), block light exposure, and minimize root-zone temperature fluctuations (Fig. 1d). Root exudates were collected every 24 h over three consecutive days. After each collection cycle, the nutrient solution was replenished, and root elasticity/integrity was monitored to confirm viability. Exudates were immediately filtered through 0.22-μm Minisart syringe filters (Sartorius, Germany) and stored at −20 °C. Six biological replicates per treatment were analyzed via ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC; 1290 Infinity LC, Agilent, USA) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (qTOF-MS; TripleTOF 6600, SCIEX, USA) at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Raw LC-MS data were pre-processed using Progenesis QI software (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA), and a three-dimensional data matrix was exported, containing sample information, metabolite identities, and ion intensity values. Internal standard peaks, known artifacts (e.g., noise, column bleed, and derivatization reagents), and redundant features were removed. Metabolite identification was carried out by matching mass spectra against multiple databases, including HMDB (https://www.hmdb.ca/), METLIN (https://metlin.scripps.edu/), and the in-house MJDB (Majorbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The data matrix was filtered to retain metabolic features detected in at least 80% of the samples in any treatment group. Ion intensities were normalized to the total ion current (sum normalization), and variables from quality control (QC) samples with a relative standard deviation (RSD) > 30% were excluded. All data were then log10-transformed to improve normality and reduce heteroscedasticity for further analyses.

DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

The DNA of rhizosphere soil was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil® Pro Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and microbial communities (bacterial and fungal) were amplified using a two-stage PCR protocol at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) (Fig. 1d). The 16S rRNA genes in extracted DNA were amplified and sequenced on the Illumina Nova6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) using 300 bp paired-end reads and the primers515F/907R, which target the V4-V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene. For fungal community composition, DNA was PCR-amplified to target the first nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region using the primers (ITS7F/ITS4R) and sequenced using 300 bp paired-end reads. The V4-V5 region of 16S rRNA and the ITS were amplified through primer pairs F515 (5’′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGC-3′) and R907 (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′), and ITS7F (5ʹ -GTGARTCATCGARTCTTTG-3ʹ) and ITS4R (5ʹ -TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3ʹ), respectively. The sequences were quality-filtered using USEARCH. In brief, sequences <50 bp and total expected errors >0.2 were removed. Chimeras were identified and removed. High-quality sequences were clustered into Amplicon Sequencing Variants (ASVs) using the UNOISE3 algorithm at a 97% identity threshold, and the most abundant sequence from each ASV was selected as a representative sequence. The taxonomic affiliation of the representative sequence was determined using the RDP classifier (version 16)79. In total, 24,579 and 21,550 reads were obtained for bacterial and fungal communities’ analysis, respectively.

Metagenomic sequencing and data analyses

Rhizosphere soil samples were subjected to metagenomic sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) platform at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Raw reads were processed for quality control using fastp (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp, version 0.20.0), which filtered out reads no more than 50 bp and those with an average quality score below 20. After the quality control process, we obtained 841 gigabases (Gb) of metagenomic clean reads, with average value of 17.5 Gb data per sample (range from 14.3 to 21.5 Gb). Metagenomic data were assembled using MEGAHIT80 (https://github.com/voutcn/megahit, version 1.1.2) with default k-mers. Contigs longer than 300 bp were retained for downstream analysis. Then, CD-HIT (v4.8.1) was used to cluster predicted open reading frames (ORFs) at both the individual sample and global levels with a 95% sequence identity threshold, generating a non-redundant gene catalog. The taxonomic and functional repertoires of the gene catalog were annotated using DIAMOND (v.0.9.22), based on BLASTP searches against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (e-value < 1e − 10, bitscore >60)81. Raw reads and normalized TPM (Transcripts Per kilobase Million) data were quantified after BLAST against the non-redundant gene catalog using Salmon (v1.6.0). Finally, Multiple sequence alignment of representative genes was performed using MUSCLE (v5.1), and phylogenetic trees were constructed using FastTree (v2.1.10).

For metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) binning, only contigs >1500 bp were used to meet the input requirements of binning tools. Binning was conducted using the metaWRAP pipeline (v1.3.2), which integrates MetaBAT2 (v2.12.1), MaxBin2 (v2.2.6), and CONCOCT (v1.0.0). Draft bins were refined using metaWRAP’s bin_refinement module with parameters -c 50 -x 10, retaining only medium- and high-quality MAGs (i.e., completeness ≥50% and contamination ≤10%). Taxonomic classification of MAGs was performed using the classify_wf module in GTDB-Tk against the GTDB reference database (Release 202). To assess the metabolic potential of the MAGs, the Prodigal module of METABOLIC v4.0 was applied to predict protein-coding open reading frames (ORFs) across all genomes. Hmmsearch program was then used to annotate proteins against HMM databases (KEGG KOfam, Pfam, TIGRfam, and custom HMMs), using the default settings within METABOLIC v4.082. To evaluate the functional capacity of the N metabolic pathways, metabolic weight scores (MW-scores) were calculated based on the metabolic profiling results and gene coverage from metagenomic read mapping. The percentage contribution of each microbial phylum to the MW-score of each metabolic pathway under the four treatments was determined. A higher percentage contribution indicated that the corresponding microbial groups more strongly represent the function, based on both gene presence and abundance.

Statistical analyses

Linear mixed-effects models were used to examine the effects of management, warming, and their interactions on wheat and microbial uptake and competition for NO3− and NH4+, rates of gross N mineralization, nitrification, immobilization, TOC of root exudates, root metabolism diversity, the relative abundance of bacteria, fungi, and functional genes. Statistical significance was based on Wald type II χ² tests and all estimated effect sizes (β) were calculated based on rescaled response variables. All analyses were performed in R v. 4.2.0 with the lme4 and car packages83. Cohen’s d was calculated to estimate multiple-treatment effect sizes on wheat and microbial uptake and competition for NO3− and NH4+, and gross N mineralization, nitrification, and immobilization rates, using value responses to warming in conservation and conventional agriculture by comparing them against ambient conditions. Positive d values indicated that the response variables in the treatment had a larger value than in the ambient condition, and vice versa. Effect sizes of warming were calculated with the effsize R v. 4.2.0 package.

Principal component analysis was used to assess changes in the root metabolite composition and soil microbial community. Nonparametric multivariate analysis of variance (ADONIS) was used to test for differences in root metabolite composition and soil microbial communities under different treatments. The dissimilarity of soil microbial communities under different treatments was determined by principal component analysis based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metrics. These analyses were performed in R v. 4.2.0 with the vegan package.

To acquire the best discriminative taxa for warming, the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal taxa at the phylum, class, order, family, genus, and ASV levels against warming were classified using the randomForest package of R v. 4.2.0. Cross-validation was performed using the rfcv() function to select appropriate features84. The varImpPlot function was used to visualize feature importance in the classification. The importance of features and the cross-validation curve were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R v. 4.2.0. The effects of warming on the ASV of bacteria and fungi were explored using the DESeq2 package. The ASVs were then phylogenetically assigned to the corresponding phylum in different management practices by FastTree2 v2.1.10.

The effects of warming on microbial functional genes were analyzed using the edger package. Subsequently, an enrichment ratio analysis was performed to identify broad functional categories with significant overrepresentation of ambient and warming-enriched KEGGs in conventional agriculture and conservation agriculture by ReporterScore package of R software (R 4.2.0). Hypergeometric tests were used to calculate the enrichment of functional pathways using the clusterProfiler package of R software (R 4.2.0).

The response ratio of N cycling-associated functional genes of microorganisms and root exudates between warming and ambient plots in conservation or conventional agriculture was calculated using the following equation:

where \({\bar{{{{\rm{X}}}}}}_{W}\) and \({\bar{{{{\rm{X}}}}}}_{A}\) were warming treatment and ambient treatment, respectively.

The differential metabolite analysis between ambient and warming plots was conducted using R with the DESeq2 packages for each agricultural system. Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) was applied to all identified metabolites. Core metabolites were identified based on a Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score of ≥1 and significant changes (p < 0.05) following warming. Metabolite source categorization and enrichment analysis were carried out using the MetOrigin database85. Functional assessments within Deep MetOrigin Analysis validated the actual associations between metabolites and microorganisms, facilitating Bio-Sandy network construction85. The influence of root metabolism profiles on N cycling gene composition was assessed using Redundancy Analysis (RDA) based on Bray–Curtis distances, calculated with the vegan package. A Random Forest analysis was conducted to identify statistically significant predictors of N metabolism-related genes using the rfPermute package. We compared the percentage increases in the mean squared error (i.e., %IncMSE) to evaluate the relative importance of different variables in predicting N cycling genes.

Interdomain ecological networks were constructed to explore interactions of microbes and metabolites, using the Inter-Domain Ecological Network Analysis Pipeline (IDENAP) (http://mem.rcees.ac.cn:8081)86. First, the genera of microbes and identified root metabolites were log-transformed, and interdomain pairwise correlation was calculated based on the SparCC method with default parameters. Genera appearing in more than half of the samples were retained for further analysis. Non-correlated associations in the matrix were filtered under the threshold value of 0.6 and significance of p < 0.05 for generating bipartite networks. Finally, networks were visualized in Cytoscape 3.8.0 and Gephi 0.10. The analysis of bipartite networks of functional genes and KEGG pathway KOs with root metabolites was the same as for the microbial taxa-metabolites network.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The DNA sequences of the 16S rRNA gene and ITS amplicons have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive under project accession numbers PRJNA1193328 and PRJNA1188655. Raw shotgun metagenomic sequences are available under project accession PRJNA1320799. For taxonomic classification, the SILVA database (release 138.1; https://www.arb-silva.de/) was used for bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences, and the UNITE database (version 9.0, released in 2023; https://unite.ut.ee/) was used for fungal ITS sequences. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

R scripts for statistical analyses are available on GitHub at https://github.com/H-CunKang/CA_Warming_N_acquisition. A permanent, citable version of the code has been archived on Zenodo with the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17103386.

References

Jägermeyr et al. Climate impacts on global agriculture emerge earlier in new generation of climate and crop models. Nat. Food 2, 873–885 (2021).

Liu, X. J. et al. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 494, 459–462 (2013).

Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 1259855 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Managing nitrogen for sustainable development. Nature 528, 51–59 (2015).

Batool, M. et al. Customized plant microbiome engineering for food security. Trends Plant Sci. 29, 482–494 (2024).

French, E. et al. Emerging strategies for precision microbiome management in diverse agroecosystems. Nat. Plants 7, 256–267 (2021).

Compant, S. et al. Harnessing the plant microbiome for sustainable crop production. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 23, 9–23 (2024).