Abstract

A bioinspired self-cleaning strategy for solar cells has been proposed to enable the automatic removal of dust deposited on surfaces. However, the presence of oil-based sticky residues from volatile organic compounds poses a significant challenge for water-based cleaning methods. In this study, we introduce oil-repelling surfaces capable of self-cleaning in any orientation to address oily dust contamination. The proposed surface features a disconnected grid pattern with domed top surfaces and hyperbolic sidewalls. The hyperbolic sidewalls contribute to superomniphobicity, while the domed top surfaces minimize oil adhesion and enhance the efficiency of photovoltaic cells. Additionally, the disconnected grid structure enhances lateral liquid repellency, achieving higher contact angles compared to connected grid designs. When applied to thin-film crystalline silicon solar cells, the surface texture enhances photovoltaic efficiency through the light-scattering effect of the lens-shaped features. Furthermore, the proposed surface demonstrates mechanical stability under repeated bending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintaining a clean surface on solar cells is essential for sustaining high energy output and long-term operational efficiency. Scheduled weekly or monthly cleanings are inefficient due to the profit losses incurred between cleaning cycles1,2,3,4. To mitigate yield reductions caused by dirt accumulation, researchers have explored various cleaning methods, including water pump systems5, robotic or drone-based cleaning6, dry cleaning7, and passive cleaning8. However, these methods present significant drawbacks, including increased maintenance needs, energy consumption, risk of physical damage to solar cells, and high operational costs1,2,3,4. While bioinspired9 or other textured surfaces10,11,12,13,14,15 enable effective removal of particulate dust through water-based cleaning, they are ineffective in environments contaminated with oils and airborne volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as industrial zones and urban areas16,17. Such oily soiling originates from the condensation of VOCs and particulate matter onto cooler surfaces, forming hydrophobic and chemically bonded residues that resist water-based cleaning18,19,20,21. These residues further promote particle adhesion and localized heating, ultimately leading to long-term efficiency degradation22,23.

We hypothesized that oil-based cleaning could serve as a viable solution for oily contamination, analogous to the water-assisted self-cleaning seen on superhydrophobic surfaces. However, for practical use, such oil-based cleaning requires robust oil-repellent surfaces capable of enduring environmental and operational challenges. Although many textured surfaces have been proposed for super-amphiphobic surfaces24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 and have addressed durability in terms of thermodynamic (e.g., maintaining a stable Cassie state)34,35, mechanical36,37,38,39 (e.g., wear and abrasion resistance), and chemical39,40,41,42 (e.g., corrosion resistance) robustness, most surface designs fail to simultaneously meet all these requirements or to effectively remove oily contaminants43. In particular, conventional liquid-repellent architectures are vulnerable to lateral imbibition, in which liquid penetrates the surface texture and disrupts the Cassie state44. Furthermore, pillar-based architectures are highly defect-sensitive; a single damaged pillar can trigger a wetting transition that compromises the entire surface functionality45.

To address these challenges, we designed a springtail-inspired hexagonally arranged hyperbolic domed star grid (HDSG) that provides robust and multiaxial liquid repellency and enables oil-based self-cleaning. The grid array was optimized by disconnecting the grid and reorienting its vertices to improve lateral repellency. The design integrates four key features. First, the hyperbolic sidewalls formed by capillary wrapping create a robust oil-repellent surface, as the top and bottom sections are wider than the middle. This inversely tapered geometry enhances repellency even against low-surface-energy liquids by generating a Laplace pressure barrier46, while the broader base of HDSG improves resistance to shear stress. Second, the disconnected hexagonal grid enhances lateral repellency by preventing lateral imbibition, even in the presence of surface defects. This offers a significant advantage over conventional pillar or reentrant grid structures. Third, the domed top surface reduces the contact area, promoting efficient oil detachment and preventing the accumulation of oily residues that typically persist on flat or nano-rough surfaces. Additionally, when applied to solar cells, the domed structure enhances optical performance through a lensing effect and provides mechanical stability by serving as an encapsulating layer for thin crystalline silicon substrates. This integrated design ensures residue-free removal of oily contaminants through multiaxial repellency, while also reinforcing the optical and mechanical performance of photovoltaic modules.

Results

Design strategy of HDSG

Springtails breathe through their cuticle and must maintain gas exchange even in wet environments (Fig. 1a). Their skin features a liquid-repellent surface composed of hexagonally interconnected structures that trap air (Fig. 1b). Inspired by this biological architecture47, we slightly modified the geometry and designed a discontinuous star grid to enhance liquid repellency over connected structures by reducing the solid fraction (Fig. 1c; see also Figure S1 for contact angle comparisons across different grid designs), and introduced dome-shaped tops to minimize liquid contact area and improve photovoltaic performance via a lensing effect (Fig. 1d). To fabricate this structure, we first prepared a disconnected hexagonal grid of polyurethane acrylate (PUA) using sequential photolithography and soft lithography (Fig. 1e). The patterned grid was then gently brought into contact with a PUA liquid prepolymer film. Through capillary action, the liquid prepolymer climbed along the sidewalls and wrapped around them48,49,50. Subsequent UV exposure solidified the prepolymer, resulting in the formation of the hyperbolic star grid (HSG) structure, as shown in Fig. 1f (experimental details in Fig. S2 and previous study48). Subsequently, dome-shaped tops were formed by contacting PUA prepolymer droplets with the flat pillar tops via a direct transfer method51,52,53 (details in Fig. S3). The prepolymer droplet was then solidified via UV curing, producing the hyperbolic domed star grid (HDSG) structure (Fig. 1g). The final HDSG was replicated into PDMS with inverted HDSG features, and this PDMS mold serves as a reusable and facile template for replicating HDSG structures in a wide range of functional materials, such as perfluoropolyether (PFPE). The HDSG effectively repels even low-surface-tension liquids in both lateral and vertical directions (Fig. 1h). When a liquid spreads over the patterned surface, it is unable to penetrate into the structure due to the inversely tapered top geometry, forming a Laplace pressure barrier that inhibits liquid intrusion, which in turn helps maintain the Cassie state via trapped air (Fig. 1i, j).

a SEM image of a springtail insect. b Magnified SEM view of the springtail’s cuticle. c Optical microscopy image of the fabricated hyperbolic domed star grid (HDSG). d Cross-sectional SEM image of a single HDSG pillar. e–g Fabrication process of the HDSG: e Initial star grid (SG) microstructures with straight sidewalls. f Transformation into a hyperbolic star grid (HSG) with hyperbolic sidewalls via capillary wrapping. g Final dome-shaped geometry of the HDSG achieved through direct transfer. h–j Schematic representations of HDSG functionality: h Multiaxial liquid repellency. i Superomniphobicity via air entrapment. j Lateral repellency that prevents liquid penetration.

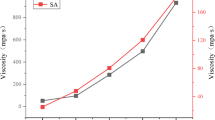

Optimization of HSG design for superomniphobicity

Beyond the well-established requirement that the equilibrium contact angle must exceed the taper angle of the structure to achieve stable liquid repellency33, it is also critical to ensure the thermodynamic stability of the Cassie state and mechanical robustness of the surface43. Optimization of the hyperbolic star grid (HSG) structure is essential to simultaneously achieve these properties. The initial disconnected star grid (SG) design and its key geometrical parameters—length (L0), width (W0), and gap (G0)—are illustrated in Fig. 2a. Design optimization was guided by contact angle measurements (Table S1). A pillar height (H) of 50 μm was selected as optimal: while increasing the height improves the thermodynamic stability of the Cassie state, it compromises mechanical robustness against shear stress. The solid fraction of the HSG is tuned by adjusting the spin-coating thickness (T) of the liquid prepolymer (Fig. 2b). As T increases, more polymer wraps along the sidewalls via capillary action, narrowing the gap (G) and increasing the solid fraction (Fig. 2c, d). When T exceeds 40.6 μm, the top sections of the HSG pillars begin to merge, forming connected pillars that result in a rapid increase in the solid fraction. Further increases in T continue to raise both the solid fraction and the width of the connected pillars (Ws), as shown in Fig. 2e. According to the Cassie–Baxter model, a higher solid fraction reduces the apparent contact angle43, which aligns with our experimental observations (Fig. 2f). The maximum contact angle was recorded at T = 8.8 μm, beyond which increased pillar merging and solid fraction led to a marked decrease in repellency.

a Definition of initial geometric parameters of SGs: length (L0), width (W0), and gap (G0). b Initial spin-coating thickness (T). c Schematic of SG-to-HSG transformation via capillary rise of liquid prepolymer. d Structural evolution with increasing T: from the non-hyperbolic SG (top left) to fully connected pillars (bottom right). e Influence of T on gap (G) and width of connected pillars (Ws). f Variation of contact angle as a function of T. Error bars in (e) and (f) represent mean ± s.d. obtained from multiple measurements (n > 15).

Multiaxial repellency and self-cleaning of sticky dust on HSGs

To further evaluate the multiaxial repellency of the HSG structure, we assessed both static contact behavior and lateral liquid spreading. Droplets of water (top left), olive oil (top right), and hexadecane (bottom) were gently deposited onto the HSG surface (Fig. 3a), all maintaining the Cassie state and exhibiting superomniphobic behavior. For lateral repellency, an olive oil droplet was placed on the surface, followed by the addition of more oil from the side. The initial droplet resisted lateral intrusion, indicating strong resistance to spreading across the surface (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Movie 1). This lateral repellency is attributed to the Laplace pressure generated at the narrow gaps between opposing triangular tips, which acts as an energy barrier to liquid propagation (Fig. 3d).

a Sessile drop images of water (top left), olive oil (top right), and hexadecane (bottom) on the HSG surface, demonstrating superomniphobic behavior. b Optical images of UV-active olive oil droplets on the top and side surfaces of the HSG, illustrating multiaxial repellency. c Stills from a movie (Movie S1) showing the lateral spreading test with olive oil. d Schematic illustration of lateral repellency mechanism based on Laplace pressure at triangular tip gaps. e Immersion test in olive oil showing stable air entrapment within HSG cavities. Localized defects (yellow) do not trigger global wetting. f Cleaning with water: Contaminants remain on the surface after rinsing. g Cleaning with oil: The same surface is restored by oil-based cleaning, with contaminants removed.

To further assess the resistance of the structure to catastrophic wetting, we fully immersed the sample in olive oil dispensed at a controlled rate (2 mL/min) (Fig. 3e). The dotted white area in Fig. 3e indicates successful air retention within the surface cavities. Notably, even in the presence of localized defects (yellow-marked region), oil intrusion remained confined and did not propagate further across the surface. This defect-tolerant behavior is likely due to the resulting local pressure gradient, which stabilizes the Cassie state and prevents wetting failure. We then demonstrated the self-cleaning capability of the HSG pattern by evaluating the removal of sticky dust. To mimic oily particulate contamination, oil mist and charcoal dust were sequentially deposited onto the surface (Fig. S4). The contaminants primarily accumulated on the top surface without entering the cavities. A water droplet (Fig. 3f) and olive oil (Fig. 3g) were applied while the sample was tilted at 20°. Olive oil effectively removed the adhered dust, whereas water was repelled and failed to capture the contaminants (Supplementary Movie 2). When glycerol was applied, sticky dust was effectively removed compared to water, owing to the higher viscosity of glycerol despite its polar nature. In contrast, ethyl acetate, a volatile solvent with low surface tension, spread over the surface of the sample and failed to remove the dust. Using oil cleaning efficiency as a reference (100%), the cleaning efficiencies of water, glycerol, and ethyl acetate were measured as 14.7%, 62.7%, and 26.8%, respectively (Fig. S5 and Supplementary Eq. 1). To elucidate the failure of cleaning with ethyl acetate, we measured the contact angles of the liquids on a flat PFPE surface. The contact angles of water, glycerol, and olive oil were 94°, 92°, and 76°, respectively (Fig. S6a), whereas ethyl acetate exhibited an almost complete wetting state (θ ≈ 0°). For superomniphobicity, the contact angle on a flat surface (θ) must exceed the taper angle (α) of the inverted tapered structures, which in this work is ~20° (Fig. S6b). Thus, the spreading behavior of ethyl acetate is consistent with this criterion and explains the limitation of superomniphobicity of inverted tapered structures. This result underscores the limitation of water-based cleaning in the presence of hydrophobic or oily residues, thereby motivating the need for oil-assisted strategies under such soiling conditions.

Mechanical durability was verified through standardized abrasion testing36. Even after 200 abrasion cycles, the HSG retained its superomniphobicity and resisted shear damage (Fig. S7), comparable to previous surfaces that required more complex re-entrant designs54. In addition, a droplet impact test simulating rain confirmed the structure’s robustness against repeated impacts (see Fig. S8). These results demonstrate that the HSG structure addresses a critical limitation of conventional superhydrophobic surfaces by enabling effective removal of oil-bound particulates. This is achieved through the combination of multiaxial repellency and mechanical robustness, supporting oil-compatible self-cleaning under realistic environmental conditions.

Removal of oil residue on HDSG surfaces

Even minimal amounts of oil residue pose a significant challenge for liquid-repellent surfaces due to the low volatility and strong adhesion of oils55. To overcome this, the HDSG design incorporates dome-shaped tops that promote complete droplet detachment and minimize residual contamination. Figure 4a, b compare the detachment behavior of oil droplets on flat HSG and dome-shaped HDSG surfaces. In this study, olive oil was selected as a low-cost, readily available oil with intermediate surface tension (~32 mN/m), serving as a practical representative for real-world contamination scenarios. In both cases, a transient capillary bridge forms during droplet removal, with the base angle governed by the receding contact angle (θr). However, the elevated detachment point on the HDSG dome leads to a thicker neck in the bridge52,56, facilitating cleaner separation without bridge breakup and thereby reducing residual oil. To validate this mechanism, we conducted both microscopic observations of oil/pillar interactions and macroscopic cleaning tests using UV-active tracers. Figure 4c, d show the oil detachment behavior at the single-pillar level. In the flat HSG structure, breakup of the capillary bridge leaves visible residue after oil removal (Fig. 4c), whereas the dome-shaped HDSG pillar enables complete detachment without residue (Fig. 4d). Macroscopic self-cleaning performance was assessed by applying olive oil containing UV-active particles onto the surfaces, followed by wiping with tissue. As shown in Fig. 4e, f, oil residue remained on the HSG surface, whereas the HDSG surface remained clean (see also Supplementary Movies 3 and 4). These findings demonstrate that the dome-shaped geometry of the HDSG not only improves droplet detachment but also enables practical and residue-free removal of sticky contaminants using common, low-cost cleaning agents. Importantly, eliminating oil residue is essential not only for visual cleanliness but also for sustaining the performance of functional surfaces such as photovoltaics. Prior studies have shown that oil- and VOC-based contaminants can block light transmission, induce localized shading, and accelerate particle accumulation, all of which reduce solar efficiency18. Therefore, the oil-repellent and residue-free characteristics of the HDSG surface provide a distinct advantage in real-world environmental conditions.

Schematic illustration of oil detachment behavior: a Oil residue remains on the flat HSG due to liquid bridge breakup; b Complete removal occurs on the HDSG due to the dome-induced clean detachment. High-speed imaging of single-pillar interactions with oil droplets: c On the HSG, oil residue remains after droplet retraction; d On the HDSG, the dome shape is preserved and no residue is observed. Macroscopic cleaning test using UV-active olive oil: e Residue remains on the HSG surface after wiping, visible under UV light; f No fluorescent residue is observed on the HDSG after cleaning.

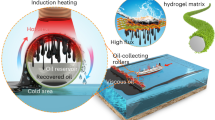

HDSG coating on thin crystalline silicon solar cells

To evaluate the functional impact of our surface design, we applied HSG and HDSG coatings to thin crystalline silicon (c-Si) solar cells (Fig. 5a, b). Reference planar cells without optical enhancement exhibited an efficiency of 16.2% (short-circuit current density (Jsc) = 36.1 mA/cm², open-circuit voltage (Voc) = 582.0 mV, fill factor (FF) = 77.1%), limited by reflection and insufficient light trapping (Figs. 5c, S9, S10 and previous studies57,58). The HSG-coated cells showed improved light absorption and reached an efficiency of 16.7%, with short- and long-wavelength gains confirmed by external quantum efficiency (EQE) and absorption spectra (Fig. S11, S12). These improvements stem from refractive index matching at the air/silicon nitride (SiNx) interface and enhanced scattering from the 3D structure (Fig. S13, S14). However, light reflection from the flat top surfaces reduced EQE in the mid-wavelength range (550–900 nm). In contrast, the dome-shaped HDSG structures resembling microlens arrays redirected incident light inward and downward59,60, reducing surface reflection and increasing the optical path length within the active layer (Fig. 5d). As a result, HDSG-coated cells achieved a higher efficiency of 17.4% (Voc = 585.5 mV, Jsc = 38.3 mA/cm², FF = 77.6%), with the best-performing device reaching 18.1%. We further verified the long-term applicability of the HDSG design through mechanical, chemical, and environmental stability tests. The coating remained intact after tape-peeling (ASTM D3359) and cyclic bending (1000 cycles at r = 1.5 cm), with no visible cracks or delamination. Liquid repellency was preserved after acid/base immersion, salt spray, and 30 days of outdoor exposure, during which photovoltaic parameters (Voc, Jsc, FF, and efficiency) showed minimal variation (Fig. S15).

a Schematic illustration of the HSG/HDSG film fabrication process on thin crystalline silicon (c-Si) solar cells. b 3D schematic cross-section of the final device structure, illustrating the layered configuration of the thin c-Si solar cell and HSG/HDSG coatings. c Current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics of solar cells with and without microstructured films. Inset: photographs of the fabricated devices. d External quantum efficiency (EQE) spectra of the same devices, showing spectral enhancements. Inset: schematic illustrating the microlens effect of HDSG domes that redirect light into the absorber layer. e Photographs of the flexible thin c-Si solar cell with HDSG films, showing bending radius of 1.5 cm. f Normalized photovoltaic parameters (Voc, Jsc, FF, and efficiency) as a function of bending cycles, confirming mechanical durability. g Optical images comparing self-cleaning ability. After contamination and rinsing, the HDSG-coated cell shows effective contaminant removal, while the flat reference remains fouled. h Relative Jsc/Jsc₀ before and after contamination, and after repeated rinsing, demonstrating superior self-cleaning performance of the HDSG-coated device. All scale bars in this figure represent 1.5 cm.

In addition to improved performance, thin c-Si solar cells with HDSG films exhibit remarkable mechanical resilience under repeated bending, a critical factor for thin-film solar cells operating in diverse environments. We conducted a bending test (Fig. 5e), repeatedly bending the cells to a 1.5 cm radius at 300 mm/min for 1000 cycles, measuring normalized photovoltaic parameters (Voc, Jsc, FF, and efficiency). The corresponding bending cycle values, shown in Fig. 5f, indicate that all parameters remained stable throughout the bending process, with minimal degradation. The HDSG films maintained strong adhesion to the c-Si substrate, owing to the inherent flexibility of the thin c-Si, the elasticity of the HDSG films, and robust interfacial adhesion.

To evaluate the contamination resistance of the HDSG coating under practical conditions, we compared its self-cleaning performance against a planar PTFE-coated cell. Both samples were deliberately contaminated and cleaned using oil. As shown in Fig. 5g, 5h, the HDSG surface enabled near-complete recovery of Jsc after repeated cleaning cycles, whereas the PTFE-coated sample showed only partial recovery (see also Fig. S16 for LED brightness restoration via HDSG self-cleaning). Additionally, we performed droplet tests using oil mixed with charcoal on both a flat PFPE surface and an HDSG surface. As shown in the Supplementary Movie 5 and Fig. S17a, the sticky oil–dust mixture spread and remained adhered on the solar cell surface coated with flat PFPE. In contrast, when applied to the HDSG surface (Supplementary Movie 6 and Fig. S17b), the droplet readily detached and rolled off, demonstrating the effective self-cleaning capability of the structured surface.

It is important to benchmark the performance of our HDSG structures against other reported superomniphobic systems. We compared six key aspects: oil repellency, mechanical robustness, chemical stability, lateral liquid repellency, ease of fabrication, and the improvement of solar cell efficiency (Fig. S18). Doubly re-entrant structures exhibit excellent liquid repellency; however, their fabrication requires complex microfabrication processes, which limits scalability28,29. Coating-based methods are facile to apply30,31, but they often compromise optical transparency and rarely demonstrate lateral repellency. Porous membrane approaches have also been proposed, but their chemical stability is restricted by the use of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based materials32. In the present work, although the liquid repellency of HDSG is somewhat lower than that of doubly re-entrant structures, direct replication onto solar cells provides strong practical advantages for daily use. Collectively, our results demonstrate that the HDSG architecture not only improves photovoltaic efficiency through enhanced light management but also ensures long-term durability and self-cleaning functionality, underscoring its practical potential for real-world solar energy applications.

Discussion

The HDSG structure was developed by reinterpreting the interconnected cuticle geometry of springtail insects into a discontinuous architecture with a reduced solid fraction. This design achieves enhanced liquid repellency, with contact angles exceeding 150°, even for low-surface-tension oils such as olive oil and hexadecane. In addition to vertical repellency, the narrow gaps between discontinuous tips generate Laplace pressure barriers that block lateral liquid intrusion, enabling multiaxial oil repellency and defect-tolerant wetting resistance, where localized wetting remains confined without spreading. The base of each pillar is reinforced via capillary-wrapped sidewalls, enhancing mechanical robustness compared to conventional pillars. Mechanical (abrasion, tape-peeling, bending), chemical (acid/base, salt spray), and environmental (outdoor exposure) stability tests confirmed that the HDSG structure maintains its performance under realistic conditions.

Furthermore, the dome-shaped tops of the HDSG pillars serve two critical functions: (1) they enable clean detachment of oil capillary bridges without leaving residue, allowing for oil-based removal of contaminants that are difficult to clean with conventional water-based methods, and (2) they function as microlenses, enhancing light trapping and thereby improving photovoltaic performance. When integrated with thin crystalline silicon (c-Si) solar cells, HDSG films significantly improve optical performance by enhancing light scattering and refractive index matching. As a result, EQE increases across the spectral range, with Jsc gains of up to 2.2 mA/cm² and efficiencies reaching 18.1%. While the oil-assisted cleaning strategy is not a universal replacement for water-based methods, it offers a viable alternative in environments where hydrophobic contaminants dominate and water-based cleaning proves insufficient, such as industrial settings, VOC-rich areas, or regions with minimal rainfall and strong hydrophobic dust adhesion. These findings demonstrate that the HDSG structure not only improves photovoltaic performance through optical enhancement and contaminant removal but also ensures long-term durability and environmental resilience, offering a practical and scalable solution for advanced solar energy systems operating under challenging real-world conditions.

Methods

Materials

The materials used in the fabrication of the structures and solar cells include PUA 301, a UV-curable prepolymer sourced from Material Chemicals Network (MCNet) Co., Ltd., and the fluoropolymer (perfluoro polyether (PFPE), MD700) obtained from JUNSUNG Polymer Co. Silicon wafers were acquired from iCell Co., Ltd. PDMS prepolymer, along with its corresponding curing agent, were purchased from Dow Corning. For the repellency tests, pure water and olive oil were sourced from SAMCHUN Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., and hexadecane was obtained from Reagent Plus (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC). In this study, UV-active pyrene particles (fluorescent UV-active particles) were used, sourced from Shanghai Alladin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd., and dissolved in olive oil at a concentration of 0.25% for residue testing. The olive oil served as a carrier medium to suspend the pyrene particles, ensuring uniform distribution for the testing. The materials used for solar cell fabrication include n-type Si wafers ( < 100 > , 1-10 Ω•cm), sourced from KRT Lab. The photoresist (DPR-i1549) for lithography patterning was purchased from Dongjin, while hexamethyldisilazane for surface treatment during the lithography process was obtained from Duksan. The developer (tetramethylammonium hydroxide, TMAH) used in the lithography development was sourced from Merck. Spin-on dopants (boron, phosphorus) were acquired from Filmtronics for the doping process, and the Al metal source for electrode deposition was obtained from KRT Lab.

Fabrication of SG array using PUA

Patterned silicon masters were fabricated through an initial photolithography step, followed by a dry etching process. The resulting silicon master featured star-shaped arrays with varying lengths, widths, and gaps, as detailed in Table S1, with dimensions falling within the following ranges: Length: 30 µm, Width: 5–10 µm, and Gap size: 40–80 µm. These arrays spanned an area of 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm. A PDMS prepolymer mixture (with a 10:1 weight ratio of prepolymer to curing agent) was poured onto the patterned silicon master and thermally cured at 60 °C for 4 h. Upon curing, the PDMS mold was carefully peeled off, leaving behind a replica of the star-shaped arrays. Figure S2a illustrates the fabrication of the PUA star grid structures. UV-curable PUA prepolymer was poured into the PDMS mold and covered with a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film, which served as the substrate. The sample was then exposed to UV light (450 mJ) for several seconds to initiate crosslinking. After UV exposure, the PET film was detached, leaving the PUA star grid structure bonded to the PET film due to the weak adhesion between the PDMS mold and the solidified PUA.

Replica molding of SG

We conducted a replica molding technique to create an SG. PUA 301 was cast onto a negative mold with the desired grid pattern. The mold was sealed with a PET film, which served as the substrate for the sample. The PUA was then UV-crosslinked for 1 min and 45 s. Following this, the PET film was peeled off the mold, and additional UV-curing was performed for 2 h.

Formation of hyperbolic star grids (HSGs)

To transform a star grid (SG) structure into a hyperbolic shape (HSG), a layer of PUA was spin-coated onto a silicon wafer. After upside-down SG patterns on the thin layer, we applied pressure (over 1 N) for 10 s. Capillary forces, arising from the grid structure, pull the PUA up the walls, counteracting gravitational and adhesive forces (Fig. S2b). The corners of the structure experience higher capillary pressure, causing more PUA to be drawn into these areas than the center, which induces a hyperbolic shape in sidewalls. Using this principle, we successfully transformed the grid structures used for reference measurements as well as the final semi-grid structure (see Fig. S1) into hyperbolic patterns. The hyperbolic structure was then UV-cured, ensuring complete polymerization after an additional 2 h of UV exposure. By varying the thickness of the wafer coating, we were able to modify the shape of the structure, achieving pillar and grid-like formations (see Fig. 2d).

Preparation of a PDMS replica mold for HSG

The double replication process for fabricating the PFPE HSG began by creating a PDMS mold from the original PUA-based hyperbolic structure. A PDMS prepolymer mixture with a lower modulus (20:1 weight ratio of prepolymer to curing agent) was poured onto the PUA-based pattern and cured at 60 °C for 4 h. After curing, the PDMS mold was carefully separated from the PUA pattern with hyperbolic sidewalls.

Double replica molding for obtaining PFPE patterns

For the final step, PFPE was selected as the material for the HSG due to its advantageous properties of low surface tension. The PDMS replica mold was used to cast PFPE, which was cured under UV light using PET film as the substrate. This process resulted in the formation of a PFPE-based HSG.

Fabrication of HDSG

To realize a dome-like structure (HDSG) for the star grids with hyperbolic sidewalls (HSG), a direct transfer method was employed. The HSG PFPE sample was gently pressed ( ~ 0.5 N) onto a glass coated with PUA 301. During the removal process, some of the PUA adhered to the flat surface of the PFPE sample, creating a dome-shaped feature (see Fig. 1i and j). The sample was then UV-cured for 2 h to fully polymerize the PUA and form the final HDSG structure. The entire process is outlined in Fig. S3. The substrate, on which the polymer for the direct transfer method is spin-coated, as well as the polymer itself, can be varied to manipulate the curvature. Subsequently, the double replica molding method was employed again to create a PDMS mold for the HDSG samples. PFPE was poured into the PDMS mold and cured under UV light to form the final HDSG. This film was then applied to a flexible thin c-Si solar cell.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained using an EM-30 SEM (COXEM, Republic of Korea) with an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. Contact angle measurements were performed with the SEO Phoenix MT (M.A.T.) Contact Angle Analyzer (Surface Science Instruments, USA). A Fusion Cure 360 UV curing and patterning device (MINUTA Tech, Republic of Korea) was used for UV curing of photocurable materials.

Fabrication of flexible thin c-Si solar cells

The fabrication process schematic is provided in Fig. S9. The fabrication procedure was adapted from our previous reports57,58 with some modifications. Czochralski (Cz)-grown n-type c-Si wafers (resistivity of 1–10 Ω•cm) with an initial thickness of 525 µm served as the starting material. These wafers were thinned to 65 µm using a 30 wt.% KOH etching solution at 85 °C. After etching, a piranha clean (H2SO4:H2O2 = 4:1) was performed at 80 °C for 10 min to remove residual potassium ions and organic residues. Emitter and back-surface-field (BSF) layers were formed using the spin-on-dopant (SOD) technique. Phosphorus-based SOD (P509, Filmtronics) was applied to a dummy Si wafer and baked at 200 °C for 20 min. Diffusion doping was conducted in a tube furnace under a mixed O2 and N2 atmosphere at 880 °C. After etching away the phosphorus silicate glass with a buffered oxide etchant, the emitter layer was formed using boron-based SOD (B155, Filmtronics). Surface passivation was achieved by depositing a 10-nm-thick Al2O3 layer via atomic layer deposition (ALD), followed by a 60-nm-thick SiNx layer on both the front and rear surfaces.

Device characterization

Device characterization employed a comprehensive suite of analytical techniques to assess both electrical and optical performance metrics. Solar cell efficiency measurements were conducted under standardized AM 1.5 G illumination using a Class AAA solar simulator (McScience K3100). Measurement accuracy was ensured through dual verification methods: primary calibration with a precision power meter and secondary validation against a Newport reference cell with NREL certification. Current-voltage characteristics were acquired at room temperature (25 °C) under ambient conditions, with voltage scans ranging from −1.0 V to 1.0 V applied at a controlled rate of 380 mV/s (dwell time of 0.5 s).

Spectral response characteristics were analyzed through external quantum efficiency measurements (McScience IPCE), using a custom-built system incorporating a xenon light source coupled with a monochromator. This setup enabled high-resolution spectral analysis across a broad wavelength range (400–1100 nm), providing detailed insights into the wavelength-dependent photon-to-electron conversion efficiency. Optical characterization was performed using a UV-visible-NIR spectrophotometer (UV-2600i, Shimadzu) equipped with a 60 mm diameter integrating sphere. This configuration allowed for simultaneous measurement of both specular and diffuse reflection components, providing comprehensive data on the light-matter interactions within the device structure. The spectrophotometric analysis covered the entire relevant spectral range for silicon photovoltaic devices, offering critical insights to validate our optical design principles and quantify light-trapping effectiveness.

Fabrication of flexible thin c-Si solar cells with HSG/HDSG films

To integrate HSG/HDSG films with flexible thin c-Si solar cells, we employed a conventional doping process used in commercial c-Si solar cell manufacturing. The design incorporated microscale grid-patterned electrodes on both the front and rear surfaces of the solar cells, enhancing bifacial light absorption and improving light management on both sides (see Fig. 5b). These grid patterns also facilitated efficient carrier collection while minimizing shading losses.

HSG/HDSG film formation

The HSG/HDSG films were directly formed on the solar cell surfaces. In contrast to the earlier characterization step, where structures were created on PET films, the HSG/HDSG films were applied directly onto the thin c-Si substrate. The process involved applying PFPE prepolymer to the cell surface using a PDMS mold with the desired pattern, followed by UV curing of the structure (see Fig. 5a).

Enhancement of rear surface reflection

To improve the reflective properties of the HSG/HDSG films on the rear surface of the solar cell, a 300-nm-thick silver (Ag) film was deposited using thermal evaporation at a tilted angle. This technique ensured a uniform coating of the Ag film onto the three-dimensional optical structures, thereby enhancing light management at the rear of the cell.

Integration of HSG/HDSG films within solar cell structure

A schematic of the thin c-Si solar cell with HSG/HDSG films is shown in Fig. 5b, illustrating the key components, including the HSG/HDSG films on both sides of the cell. This integrated design enhances both the optical and protective functionalities of the solar cell.

Stability Tests for HDSG Coating

Mechanical stability was evaluated through adhesion, bending, and abrasion tests. In the adhesion test (tape peeling, ASTM D3359 Method B), a cross-cut grid was made on the HDSG-coated surface using a sharp blade. Adhesive tape was applied, pressed, and removed (adhesion rating: 5B). In the cyclic bending test, HDSG-coated thin c-Si solar cells were subjected to 1000 bending cycles at a bending radius of 1.5 cm. In the abrasion test (sandpaper friction), samples were fixed on a 2 × 5 cm glass slide and abraded using a 50 g weight over 400-grit sandpaper for 250 reciprocating cycles. Structural assessment was performed using optical microscopy and oil droplet tests (Fig. S7). A droplet impact test was conducted to simulate rain exposure. Water droplets were repeatedly dropped onto the HDSG surface, which retained its structural integrity and liquid repellency throughout the test (Fig. S8).

Chemical stability was tested under acidic, basic, and saline conditions. Samples were immersed in hydrochloric acid (HCl, pH ~2) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, pH ~13) for 2 hours, and contact angle measurements were taken after each test (Fig. S15c, d). In the salt spray test, samples were immersed in 5 wt% NaCl solution for 2 hours, followed by contact angle measurement (Fig. S15e).

Environmental stability was evaluated through outdoor exposure and photovoltaic performance monitoring. Samples were exposed to natural outdoor conditions in Korea for 30 days during summer (average ~27 °C, ~68% RH), and the contact angle was measured afterward (Fig. S15f). HDSG-coated c-Si solar cells were also tested under the same conditions for photovoltaic performance, and Voc, Jsc, FF, and efficiency were measured using a calibrated solar simulator (Fig. S15b).

Data availability

All data needed to support the conclusions of this manuscript are included in the main text or supplementary information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sarver, T., Al-Qaraghuli, A. & Kazmerski, L. L. A comprehensive review of the impact of dust on the use of solar energy: History, investigations, results, literature, and mitigation approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 22, 698–733 (2013).

Deb, D. & Brahmbhatt, N. L. Review of yield increase of solar panels through soiling prevention, and a proposed water-free automated cleaning solution. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 3306–3313 (2018).

Farrokhi Derakhshandeh, J. et al. A comprehensive review of automatic cleaning systems of solar panels. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101518 (2021).

Sayyah, A., Horenstein, M. N. & Mazumder, M. K. Energy yield loss caused by dust deposition on photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy 107, 576–604 (2014).

Abdolzadeh, M. & Ameri, M. Improving the effectiveness of a photovoltaic water pumping system by spraying water over the front of photovoltaic cells. Renew. Energy 34, 91–96 (2009).

Ghodki, M. K. An infrared based dust mitigation system operated by the robotic arm for performance improvement of the solar panel. Sol. Energy 244, 343–361 (2022).

Aly, S. P., Gandhidasan, P., Barth, N. & Ahzi, S. Novel dry cleaning machine for photovoltaic and solar panels. In 2015 3rd International Renewable and Sustainable Energy Conference (IRSEC), 1–6 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/IRSEC.2015.7455112.

Law, A. M., Jones, L. O. & Walls, J. M. The performance and durability of Anti-reflection coatings for solar module cover glass – a review. Sol. Energy 261, 85–95 (2023).

Nishimoto, S. & Bhushan, B. Bioinspired self-cleaning surfaces with superhydrophobicity, superoleophobicity, and superhydrophilicity. RSC Adv. 3, 671–690 (2013).

Nomeir, B., Lakhouil, S., Boukheir, S., Ali, M. A. & Naamane, S. Recent advances in polymer-based superhydrophobic coatings: preparation, properties, and applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 22, 33–89 (2025).

Nomeir, B. et al. Synthesis of a novel high-performance siloxene based 2D material for durable and transparent superhydrophobic coatings with self-cleaning and anti-icing properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 64, 6460–6474 (2025).

Nomeir, B., Lakhouil, S., Boukheir, S., Ali, M. A. & Naamane, S. Hyper-durable, superhydrophobic/superoleophilic fabrics based on biopolymers and organic and inorganic resins for self-cleaning and efficient water/oil separation applications. N. J. Chem. 48, 11757–11766 (2024).

Nomeir, B., Lakhouil, S., Naamane, S., Ali, M. A. & Boukheir, S. Durable, transparent and superhydrophobic coating with temperature-controlled dual-scale roughness by self-assembled raspberry nanoparticles. Heliyon 10, e34983 (2024).

Nomeir, B., Lakhouil, S., Boukheir, S., Ali, M. A. & Naamane, S. Durable and transparent superhydrophobic coating with temperature-controlled multi-scale roughness for self-cleaning and anti-icing applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 189, 108338 (2024).

Nomeir, B., Lakhouil, S., Boukheir, S., Ali, M. A. & Naamane, S. Recent progress on transparent and self-cleaning surfaces by superhydrophobic coatings deposition to optimize the cleaning process of solar panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 257, 112347 (2023).

Rajabi, H., Hadi Mosleh, M., Mandal, P., Lea-Langton, A. & Sedighi, M. Emissions of volatile organic compounds from crude oil processing – Global emission inventory and environmental release. Sci. Total Environ. 727, 138654 (2020).

Waqar, A., Othman, I., Skrzypkowski, K. & Ghumman, A. S. M. Evaluation of success of superhydrophobic coatings in the oil and gas construction industry using structural equation modeling. Coatings 13, 526 (2023).

Wang, X. & Shen, J. A review of contamination-resistant antireflective sol–gel coatings. J. Sol. Gel Sci. Technol. 61, 206–212 (2012).

Urrejola, E. et al. Effect of soiling and sunlight exposure on the performance ratio of photovoltaic technologies in Santiago, Chile. Energy Convers. Manag. 114, 338–347 (2016).

IEA PVPS Task 13. Soiling Losses – Impact on the Performance of Photovoltaic Power Plants. IEA PVPS Report T13-21:2022 (2022). https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IEA-PVPS-T13-21-2022-REPORT-Soiling-Losses-PV-Plants.pdf.

Ferrari, M. & Cirisano, F. Wetting Properties of Simulated and Commercial Contaminants on High Transmittance Superhydrophobic Coating. Nanomaterials 13, 2541 (2023).

Dorobantu, L., Popescu, M. O., Popescu, C. & Craciunescu, A. The effect of surface impurities on photovoltaic panels. REPQJ 9, 13–15 (2011).

Zhang, J., Zhang, L. & Gong, X. Large-scale spraying fabrication of robust fluorine-free superhydrophobic coatings based on dual-sized silica particles for effective antipollution and strong buoyancy. Langmuir 37, 6042–6051 (2021).

Lee, H. et al. Function transformation of polymeric films through morphing of surface shapes. Chem. Eng. J. 434, 134665 (2022).

Lv, C. et al. Advanced micro-textural engineering for the fabrication of high-performance superomniphobic surfaces. Chem. Eng. J. 505, 159306 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. Superomniphobic surfaces for easy-removals of environmental-related liquids after icing and melting. Nano Res 16, 3267–3277 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. One-step fabrication of flexible bioinspired superomniphobic surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 39665–39672 (2022).

Liu, T. & Kim, C.-J. Turning a surface superrepellent even to completely wetting liquids. Science 346, 1096–1100 (2014).

Das, R., Ahmad, Z., Nauruzbayeva, J. & Mishra, H. Biomimetic coating-free superomniphobicity. Sci. Rep. 10, 7934 (2020).

Wang, W., Vahabi, H., Movafaghi, S. & Kota, A. K. Superomniphobic surfaces with improved mechanical durability: synergy of hierarchical texture and mechanical interlocking. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6, 1900538 (2019).

Wang, Y. & Bhushan, B. Wear-resistant and antismudge superoleophobic coating on polyethylene terephthalate substrate using SiO2 nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 743–755 (2015).

Zhu, P., Kong, T., Tang, X. & Wang, L. Well-defined porous membranes for robust omniphobic surfaces via microfluidic emulsion templating. Nat. Commun. 8, 15823 (2017).

Brown, P. S. & Bhushan, B. Durable, Superoleophobic polymer–nanoparticle composite surfaces with re-entrant geometry via solvent-induced phase transformation. Sci. Rep. 6, 21048 (2016).

Scarratt, L. R. J., Steiner, U. & Neto, C. A review on the mechanical and thermodynamic robustness of superhydrophobic surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 246, 133–152 (2017).

Chen, X., Wen, G. & Guo, Z. What are the design principles, from the choice of lubricants and structures to the preparation method, for a stable slippery lubricant-infused porous surface?. Mater. Horiz. 7, 1697–1726 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Design of robust superhydrophobic surfaces. Nature 582, 55–59 (2020).

Milionis, A., Loth, E. & Bayer, I. S. Recent advances in the mechanical durability of superhydrophobic materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 229, 57–79 (2016).

Verho, T. et al. Mechanically durable superhydrophobic surfaces. Adv. Mater. 23, 673–678 (2011).

Zhang, D., Wu, G., Li, H., Cui, Y. & Zhang, Y. Superamphiphobic surfaces with robust self-cleaning, abrasion resistance and anti-corrosion. Chem. Eng. J. 406, 126753 (2021).

Li, D., Ma, L., Zhang, B. & Chen, S. Large-scale fabrication of a durable and self-healing super-hydrophobic coating with high thermal stability and long-term corrosion resistance. Nanoscale 13, 7810–7821 (2021).

Chen, F. et al. Table salt as a template to prepare reusable porous PVDF–MWCNT foam for separation of immiscible oils/organic solvents and corrosive aqueous solutions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1702926 (2017).

Peng, C., Chen, Z. & Tiwari, M. K. All-organic superhydrophobic coatings with mechanochemical robustness and liquid impalement resistance. Nat. Mater. 17, 355–360 (2018).

Chen, F. et al. Robust and durable liquid-repellent surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 8476–8583 (2022).

Arunachalam, S., Das, R., Nauruzbayeva, J., Domingues, E. M. & Mishra, H. Assessing omniphobicity by immersion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 534, 156–162 (2019).

Domingues, E. M., Arunachalam, S. & Mishra, H. Doubly reentrant cavities prevent catastrophic wetting transitions on intrinsically wetting surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 21532–21538 (2017).

Tuteja, A. et al. Designing superoleophobic surfaces. Science 318, 1618–1622 (2007).

Yun, G.-T. et al. Springtail-inspired superomniphobic surface with extreme pressure resistance. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat4978 (2018).

Kim, J. et al. Robust superomniphobic micro-hyperbola structures formed by capillary wrapping of a photocurable liquid around micropillars. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2010053 (2021).

Kim, J. et al. Enhancement of oil repellency on hyperbolic microarrays by compressive bending of elastomeric films. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 139270 (2023).

Koleczko, M. J. et al. Directional liquid mobility and interlocking of anisotropic micropillar structures modulated by multiple compressive bending. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 42, 2693–2700 (2025).

Kang, D. et al. Shape-controllable microlens arrays via direct transfer of photocurable polymer droplets. Adv. Mater. 24, 1709–1715 (2012).

Kim, J. H., Kim, J., Kim, S., Yoon, H. & Lee, W. B. Anisotropic wettability manipulation via capturing architected liquid bridge shapes. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 14630–14639 (2023).

Kim, J. H., Bae, J. G., Yoon, H. & Lee, W. B. Pattern formation in confined core-shell structures: stiffness, curvature, and hierarchical wrinkling. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2300942 (2024).

Vu, H. H., Nguyen, N.-T. & Kashaninejad, N. Re-entrant microstructures for robust liquid repellent surfaces. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2201836 (2023).

Huang, S., Li, J., Chen, L. & Tian, X. Suppressing the universal occurrence of microscopic liquid residues on super-liquid-repellent surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 3577–3585 (2021).

Zhang, X., Padgett, R. S. & Basaran, O. A. Nonlinear deformation and breakup of stretching liquid bridges. J. Fluid Mech. 329, 207–245 (1996).

Hwang, I., Um, H.-D., Kim, B.-S., Wober, M. & Seo, K. Flexible crystalline silicon radial junction photovoltaics with vertically aligned tapered microwires. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 641–647 (2018).

Choi, D. et al. Wafer-scale radial junction solar cells with 21.1% efficiency using c-Si microwires. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2208377 (2022).

Tang, Z., Tress, W. & Inganäs, O. Light trapping in thin film organic solar cells. Mater. Today 17, 389–396 (2014).

Davies, P. A. Light-trapping lenses for solar cells. Appl. Opt. 31, 6021–6026 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2021R1A6A1A03039981 [M.J.K., J(K).K., J(H).K., T.O., H.Y.] and RS-2024-00341884 [M.J.K., J(K).K., J(H).K., T.O., H.Y.]), and by the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2025-25418800 [H.-D.U., Y.A., S.H., G.K., H.C., J.H.K.]). Additional support was provided by the Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00401346 [H.-D.U., Y.A., S.H.]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.J.K., Y.A., J(K).K., H.-D.U, and H.Y. Supervision: H.-D.U., and H.Y. Funding acquisition: H.-D.U., and H.Y. Methodology: M.J.K., Y.A., J(K).K., J(H).K., S.P., T.O., S.H., G.K., H.C., and J.H.K. Investigation: M.J.K., Y.A., J(K).K., J(H).K., S.P., T.O., S.H., G.K., H.C., and J(H).K., Writing-review & editing: M.J.K., Y.A., J(K).K., J(H).K., K.S., H.-D.U., and H.Y.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koleczko, M.J., Ahn, Y., Kim, J. et al. Multiaxial oil-repellent surfaces for self-cleaning of sticky dust and enhanced photovoltaic efficiency. Nat Commun 16, 11242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66077-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66077-0