Abstract

The cascade of bio-/chemo-catalysis with quantitative integration and optimal activity is vital for catalytic conversion, but highly challenging. Here, we innovate a co-immobilization strategy by mimicking cellular transmembrane transport using ionic covalent organic framework capsules (iCOFcap) to co-encapsulate multi-enzymes and chemocatalysts. Thanks to the swellable polyethylene glycol and the adjustable charge of iCOFcap shells, multi-enzymes can be adsorbed onto the iCOFcap shells and then transported stepwise into the inner cavity of iCOFcap by adjusting electrostatic interaction between the enzymes and iCOFcap. Thus, the iCOFcap enables both transmembrane transport multi-enzymes and one-pot pre-encapsulation of chemocatalysts to construct various cascade catalysts, enabling quantitative integration and nearly complete retention of enzyme activity. The formed heterogeneous cascade catalysts show excellent comprehensive performance for CO2 reduction with good reusability. Thus, this study presents a co-encapsulation strategy for bio-/chemo-catalysis, providing an energy-efficient alternative for biotechnological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green biomanufacturing with low energy consumption, high efficiency, and sustainability is a major transformation of manufacturing mode1. Enzymes, as the “core chip” of green biomanufacturing, are natural catalysts with good regio-, stereo-, and chemoselectivity, which offer great potential in various fields2,3. Actually, the practical biomanufacturing process usually involves several catalytic steps and may require the cascade of multiple biocatalysts (enzymes) and/or chemocatalysts4,5,6,7, e.g., the cascade of formate dehydrogenase (FDH) and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) to achieve CO2 reduction8, the cascade of palladium and human carbonic anhydrase II to produce chiral alcohols9. However, the stable synergy of multiple enzymes under industrial conditions is challenging, complicated, and inefficient. In addition, for chemo-/bio- hybrid catalysis, the cascade systems usually possess low catalytic efficiency due to the unmatchable catalytic conditions for fragile enzymes and robust chemocatalysts. Co-immobilization of these catalysts on solid supports can be considered a convenient and effective way to address these limitations. Currently, reported enzyme carriers (e.g., sol–gel matrices, inorganic materials, adsorbent resin, and organic nanoparticles) mostly exhibit amorphous or nonporous structures, which unavoidably face issues with the mass transfer efficiency and the range of catalytic substrates. Their immobilization strategies, such as adsorption10,11, covalent bonding12, and in situ13, still have some limitations14,15. For instance, it is challenging to co-immobilize bio- and chemo-catalysts in controllable and precise proportions and locations, and to cascade these catalysts with excellent mass transfer performance for increasing catalytic performance. Moreover, unfavorable conditions (e.g., reactive agents, organic solvents, and high temperatures) during the immobilization process often led to reduced enzymatic activity. Thus, the development of biomaufacturing is in dire need of immobilization technology for constructing cascade catalyst systems, especially for a cascade of bio- and chemo-catalysts.

In nature, cells can achieve collaboration of multi-step intracellular reactions16,17 by the transmembrane transport of biomacromolecules (e.g., lipids, proteins) by endocytosis. Inspired by nature, the cascade immobilization of biomacromolecules can be achieved by mimicking transmembrane transport. Currently, flexible organic polymers are commonly used to mimic a phospholipid bilayer to simulate transmembrane transport of cells to achieve targeted delivery systems of biomacromolecules, which are usually used in living organisms18. However, the use of the transmembrane transport strategy for building the cascade immobilization platform and catalysis in vitro has not yet been reported due to the limitation of carrier stability. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs), a class of crystalline porous polymers, have emerged as ideal candidates for cascade immobilization because of their distinct advantages19, such as good stability, well-defined structures, high surface areas, and facile functionality. However, COFs are challenging to mimic transmembrane transport to immobilize enzymes due to their pore size and structural rigidity limitations. To address these limitations, hybridizing COFs with swellable polymers can be a feasible approach. The biocompatible polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymer is widely used in diverse biomedical and biotechnological applications. PEG polymers exhibit swelling behavior in aqueous solutions, enabling them to imbibe biological fluids20,21, which have drawn considerable attention as carriers for transmembrane transport22. In previous reports23, our team pioneered a class of COFs, polymer-covalent-organic-frameworks (polyCOF), which uses linear PEGylate polymers as COF building blocks. PolyCOFs can combine the porosity, structural versatility, and chemical stability of COFs with PEG’s good mechanical properties and swelling behavior. Moreover, the presence of PEG polymers can promote the liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) to form stable droplets24,25, hence benefiting the formation of COF capsules. To promote the transmembrane transport of enzymes from the outer environment to the inner capsule, ionic COFs can be designed to adsorb enzymes by electrostatic interactions and transport enzymes by charge reversal via altering buffer pH.

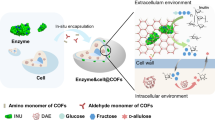

Herein, we introduce a PEG-driven LLPS synthesis approach to produce ionic COF capsules (iCOFcap) that can achieve co-immobilization of multi-enzymes by mimicking cell transmembrane transport (Fig. 1). Due to the swellable PEG in the COF capsules, iCOFcap can swell upon adsorbing a buffer solution, thereby promoting the loading of enzymes into the COF shells by adjusting the electrostatic interaction between the enzymes and ionic COFs. Then, enzymes can be transported into the inner COF capsule cavity by altering the buffer pH, thereby changing the charge of the COF capsule shells (Fig. 1a). To construct cascade biocatalysts, chemocatalysts (e.g., electron mediator (Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O) and cofactors (NAD+)) can be pre-encapsulated by the COF capsules via a one-pot method and then transport multiple enzymes (e.g., FDH and GDH) stepwise into the COF capsule. The formed iCOFcap biocatalysts offer a feasible route for efficient photo- and multi-enzyme catalysis of CO2 reduction (Fig. 1b). Therefore, this study innovates an enzyme immobilization strategy and provides a versatile platform for multi-enzyme immobilization.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of iCOFcap

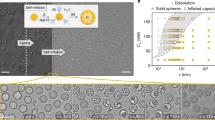

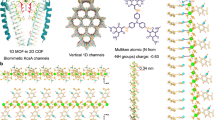

To demonstrate the proof of concept, we designed and prepared a class of cationic COF capsules, iCOFcap-1, via condensation polymerization of BMTH (2,5-bis(2-methoxyethoxy)terephthalohydrazide), HPTMB (2-(2,5-di(hydrazinecarbonyl)phenoxy)-N,N,N-trimethylethan-1-aminiumand), TB (1,3,5-triformylbenzene), and a PEGylated polymer additive, DTH-600 (Mw = ~17800 g/mol)23, in an emulsion formed by water and chloroform with scandium trifluoromethane sulfonate (Sc(OTf)3) as a catalyst (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figs. 1–3, and Supplementary Methods 1–4). The ratio of DTH-600:BMTH:HPTMB:TB was systematically studied (0:21:9:20; 1:20:9:20; 3:18:9:20; 5:16:9:20; 10:11:9:20) and profoundly impacted the reaction outcome (Supplementary Methods 5 and 6). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to characterize the morphology and particle size distribution of the iCOFcap-1 products. As shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5, adding the PEGylated DTH-600 afforded dispersed high-quality iCOFcap-1 with hollow spherical morphology and smooth shell surfaces. It was consistent with our previous work in which PEGylated polymer additives improved the mechanical strength, processability, and flexibility of COF membranes23. The structure of iCOFcap-1 was identified by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). Among the ratios studied, 0:21:9:20; 1:20:9:20; 3:18:9:20; 5:16:9:20; 10:11:9:20 matched the characteristic PXRD peaks of COF-4223,26 (2θ = 3.4°, 7.0°, and 26.9°, Fig. 2c). N2 sorption data of iCOFcap-1 (0:21:9:20; 1:20:9:20; 3:18:9:20; 5:16:9:20; 10:11:9:20) at 77 K revealed BET surface areas of 649 m2/g, 558 m2/g, 370 m2/g, 271 m2/g, and 41 m2/g, respectively (Fig. 2d). Pore size distribution, as calculated using the density functional theory (DFT) method, revealed intrinsic pores of 2.2 nm (COF-42), as well as a new pore of 1.2 nm, ascribed to the cross-linking effect of linear polymers (DTH-600) in iCOFcap-1 (Supplementary Fig. 6). It was found that PEGylated DTH-600 served as a droplet stabilizer and participated in the formation of iCOFcap-1. Fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR) showed the stretching modes at 2867 cm−1 in iCOFcap-1, which we attribute to PEGylated DTH-600 (Supplementary Fig. 7). FT-IR showed an increment of stretching modes at 1020 cm−1 in iCOFcap-1, attributed to HPTMB monomer (Fig. 2e). Increasing the amount of DTH-600 or HPTMB monomer decreased their crystallinity and surface area because these bulky monomers could block the COF pores (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 8). It should be noted that adding HPTMB could dramatically change the charge of the COF capsule. The zeta potentials of neutral COF capsules without HPTMB were negative in PB buffer solution (pH 7.4), while iCOFcap-1 was positively charged with the increase of positive monomer (Fig. 2f). Similarly, an anionic COF capsule, iCOFcap-2, was fabricated using SDHS (sodium 2-(2,5-di(hydrazinecarbonyl)phenoxy)ethane-1-sulfonate) instead of HPTMB (Fig. 2a). The iCOFcap-2 (0:21:9:20; 1:20:9:20; 3:18:9:20; 5:16:9:20; 10:11:9:20) was illustrated as detailed in SI, the morphology and particle size distribution being studied by SEM (Supplementary Fig. 9) and TEM (Supplementary Fig. 10), BET surface areas by N2 sorption (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12), crystallinity by PXRD (Supplementary Fig. 13). The zeta potential measurements revealed that iCOFcap-2 was negative due to the anionic SDHS monomer (Supplementary Fig. 14). Meanwhile, similar to iCOFcap-1, their porosity and crystallinity gradually decreased with the increase of SDHS monomer (Supplementary Fig. 15).

a Synthesis route of iCOFcap-1. b TEM images of iCOFcap-1 prepared with different monomer ratios (from left to right, DTH-600:DTH:HPTMB:TB = 0:21:9:20; 1:20:9:20; 3:18:9:20; 5:16:9:20; 10:11:9:20). Scale bar: 200 nm. Three times each experiment was repeated independently with similar results. Characterizations of iCOFcap-1 prepared with different monomer ratios: c PXRD patterns, d N2 sorption isotherms, e FT-IR spectra, and f zeta potentials. The error bar of the sample refers to the standard deviation of three groups prepared at different times (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Preparation and characterization of enzyme◎iCOFcap-1

Lipase (Aspergillus niger lipase) was selected as a model enzyme to study enzyme encapsulation ability by iCOFcap-1 (Lipase◎iCOFcap-1) using the stepwise transmembrane transport method. It has been reported that the materials formed by PEG could imbibe a large number of biological fluids by swelling experiments22. The swelling ratio of iCOFcap-1 is a critical parameter for the enzyme entrapment capability. The PEGylated DTH-n was varied (n = 400, 600, 800, representing the molecular weight of the PEG connector) and profoundly impacted the reaction outcome. Similar to DTH-600, The DTH-400 and DTH-800 monomers also formed iCOFcap-1 with good quality, verified by SEM (Supplementary Fig. 16), TEM (Supplementary Fig. 17), N2 sorption data (Supplementary Fig. 18), and PXRD patterns (Supplementary Fig. 19). The dynamic light scattering (DLS) results revealed that the swelling ratio of iCOFcap-1 (taking DTH-n:DTH:HPTMB:TB = 5:16:9:20 as a representative) could be adjusted from 22.5 ± 2.8% to 47.9 ± 4.1% when changing the length of PEG connector, i.e., changing DTH-400 to DTH-800 (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 20). Meanwhile, the loading amount of lipase increased from 420 ± 20 mg g−1 to 620 ± 30 mg g−1 when changing DTH-400 to DTH-800, where the proportion of fixed lipase and lipase in the solution was 38 ± 5 to 52 ± 4% and 62 ± 5 to 48 ± 4%, respectively. The afforded lipase◎iCOFcap-1 showed good activities compared to the free enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 21 and Supplementary Method 7). Moreover, we also found that increasing the cationic charge (i.e., amount of cationic HPTMB monomer) of iCOFcap-1 could increase the loading speed and number of enzymes (Fig. 3d). The iCOFcap-1 maintained good crystallinity after transporting lipase (Supplementary Fig. 22). The pore size distribution results revealed no significant changes in the pore size of iCOFcap-1 prepared using the stepwise method before and after enzyme immobilization. This observation indicates that the enzymes are encapsulated within the COF capsule cavity rather than within the pore channels (Supplementary Fig. 23). The consistency of this phenomenon was further confirmed through comparative studies using a one-pot enzyme immobilization approach, where similarly unaltered pore sizes were observed post-immobilization (Supplementary Fig. 24). Meanwhile, there was no significant enzyme leakage for lipase◎iCOFcap-1 in pH = 5.0/7.0 (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26 and Supplementary Method 8). Overall, iCOFcap-1 with DTH-600 possessed a better swelling ratio, enzyme activity, loading amount, and COF structure. Thus, we selected 5:16:9:20 (DTH-600:DTH:HPTMB:TB) to produce enzyme◎iCOFcap-1 for the following studies.

a Schematic illustrations and b SIM image and 3D view of iCOFcap-1before loading FITC-tagged lipase, after loading FITC-tagged lipase, transporting FITC-tagged lipase for 3 h, and transporting FITC-tagged lipase for 6 h (from left to right). Scale bar: 1 μm. c The swelling ratio of iCOFcap-1 with DTH-400/600/800. d The loading amount of lipase of iCOFcap-1 with different monomer ratios. e The enzyme permeability of iCOF film and COF film. The error bar of the sample refers to the standard deviation of three groups prepared at different times (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The behaviors of enzymes loading and transporting into the capsule cavity were investigated by super-resolution imaging system (SIM) analysis (Supplementary Method 9). Figure 3a, b showed that lipase was first adsorbed by the shell of iCOFcap-1, then gradually transported into the capsule cavity by altering buffer pH. The capsular COF materials align structurally and functionally with the transmembrane dynamics of lamellar membranes, enabling analogous transport mechanisms. The iCOFcap-1 achieved 670 mg g−1 protein loading, declining to 600 mg g−1 with transporting 3 h and 560 mg g−1 with transporting 6 h, with ~16% outer-layer proteins released externally and ~84% inner-layer transported inward (Supplementary Fig. 27a). Thus, the reduction in total loading capacity serves as an indicator to track the progress of translocation. The transport process reached 65% completion within 3 h and achieved near completion (>95%) by 6 h, as evidenced by the nearly undetectable protein levels in the external solution (Supplementary Fig. 27b and Supplementary Method 10). Meanwhile, the confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of the neutral COF capsule (5:25:0:20) without adding ionic monomers showed that lipase could be loaded into the COF capsule shell but could not be transported into the capsule cavity under the same treatments (Supplementary Fig. 28). This phenomenon could be ascribed to the lack of electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged lipase and neutral COF capsule (5:25:0:20). Thus, lipase was difficult to release into the neutral COF capsule. We further proved the conclusion using iCOF film (a uniform and thickened version of iCOFcap-1 capsule wall) prepared via an interfacial polymerization method using identical monomers as iCOFcap-1 (Supplementary Methods 11 and 12). As shown in Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figs. 29–32 and Supplementary Method 13, the CLSM measurement revealed that the enzyme permeability of iCOF film (DTH-600:DTH:HPTMB:TB = 5:16:9:20) was much higher than that of neutral COF film (DTH-600:DTH:HPTMB:TB = 5:25:0:20). Zeta potential can quantify the electrostatic interactions between enzymes and carriers, thus enabling the prediction of protein affinity to the different carriers. The zeta potentials illustrated that iCOFcap-1 was positive in PB buffer solution, lipase with a negative charge, and the surface zeta potentials of the capsule decreased to 3.64 ± 0.7 mV after loading lipase and then increased gradually to 10.53 ± 0.9 mV with transporting into the capsule cavity (Supplementary Fig. 33a). Thus, zeta potentials can be used as an indicator to judge whether the enzyme has been transported into iCOFcap-1. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 33b, the Zeta potential analysis confirmed that the enzyme exhibited a negative charge at a pH of 7.0. Meanwhile, the COF capsule surface maintained a positive zeta potential, which drove successful enzyme adsorption onto the COF shell. Upon pH adjustment to 5.0, the protein underwent charge reversal to positive and has the same charge as the iCOFcap-1, causing the enzyme to break away from the COF shell and release it into the COF cavity. The reason the enzyme can be released is possibly because it is an amphoteric electrolyte. Furthermore, transporting HRP by iCOFcap-2 was illustrated as detailed in SI (Supplementary Method 14 and 15), with the swelling ratio being studied by DLS (Supplementary Fig. 34a), crystallinity by PXRD (Supplementary Fig. 34b), and the transporting process by CLSM (Supplementary Fig. 35). Meanwhile, there was no significant enzyme leakage for HRP◎iCOFcap-2 in pH = 7.0/9.0 (Supplementary Figs. 36 and 37).

Cascade biocatalysis of the iCOFcap-1 bioreactor

Conversion of CO2 to formic acid was chosen as a representative reaction to evaluate the performance iCOFcap bioreactor (Fig. 4a). iCOFcap-1 was thereby used to construct a photoenzyme cascade reactor. To construct such a cascade biocatalyst, electron mediators (Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O) and NAD+) were first pre-encapsulated into the COFcap to generate RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 via a one-pot synthesis method. Then, FDH was transported into RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 using the stepwise transmembrane transport method (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Methods 16 and 17). To construct an optimal catalyst, the loading amount of Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O was first investigated. In a typical one-pot synthesis procedure, Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O was mixed with COF monomers (DTH-600, DTH, HPTMB, and TB) to form RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1 in one pot. Thereupon, RhCp*9.9% and NAD+ were co-immobilized into iCOFcap-1 to form RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 by a one-pot method. The XPS images supported the presence of NAD+ in RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (Fig. 4c). The PXRD measurement showed that RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1 maintained the crystalline structure of iCOFcap-1 (Supplementary Fig. 38). Meanwhile, the BET surface area of RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1 had no significant decrease compared with that of iCOFcap-1 (Supplementary Fig. 39). As shown in Fig. 4b, Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O had indeed been encapsulated in iCOFcap-1 by TEM images and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mappings. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can further probe the chemical composition of the photocatalysts (Supplementary Fig. 40). The existence of the Rh element in RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1 also indicated the successful incorporation of Rh into the capsule. A series of photocatalysis experiments was performed to optimize the visible-light-driven regeneration activity of NADH by the RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1. As shown in Fig. 4d, the wavelength-dependent evolution of NADH was also performed to gain the apparent quantum yield (AQY). The AQY of RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1 was higher than that of iCOFcap-1 under each wavelength, which was well-matched with the results of DRS. We adjusted the Cp*Rh(H2O) content from 2.2 to 11.2 wt% to investigate the influence of content on the photo-regeneration of NADH (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Methods 18 and 19). RhCp*9.9%◎iCOFcap-1 (the loading amount of Cp*Rh(H2O) was 9.9 wt%) was significantly effective for NADH photo regeneration, accumulating up to 78 ± 3% yield within 15 min, about 2.3 times higher than that of iCOFcap-1. Then, FDH was transported into RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 by the stepwise method. From the CLSM results (Supplementary Fig. 41), FITC-tagged FDH can be uniformly and firmly transported inside RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 using the stepwise method. For FDH, a load amount of 280 ± 10 mg g−1 afforded optimal activities of 93 ± 1% vs the respective free enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 42), where the proportion of fixed enzymes and enzymes in the solution was 70 ± 2% and 30 ± 2%, respectively. Before irradiation, the mixed system was placed in the dark for 1 h to ensure CO2 was fully dissolved in the system. After system optimization, FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 was able to generate 1.61 mmol h−1 gmaterial−1 formic acid from CO2 under visible light irradiation (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 43), almost 2 times higher than the iCOFcap-1 (one-pot integration of FDH, RhCp*and NAD+). Meanwhile, the product yield of FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 is significantly higher than that of corresponding free systems (Supplementary Fig. 44). FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 was ineffective in the absence of FDH or NAD+ (Supplementary Fig. 45). Due to the low NADH regeneration ability of iCOFcap-1, FDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 had a low yield rate of formic acid. Importantly, this heterogeneous catalyst could be easily reused and achieved a productivity of >84% after ten cycles (Supplementary Fig. 46).

a The illustration of the synthesis of FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 and cascade catalysis route from CO2 to formic acid. b TEM image and EDS elemental mappings of RhCp*◎iCOFcap-1 indicating the C, N, and Rh elemental distributions. Scale bar: 100 nm. Three times each experiment was repeated independently with similar results. c High-resolution XPS of P 2p of NAD+◎iCOFcap-1. d The AQY as a function of the incident light wavelength in photocatalytic NADH regeneration and the related DRS. e Effects of RhCp* contents on the photo-regeneration yield of NADH in 15 min. f Visible-light-driven artificial photosynthesis of formic acid from CO2 catalyzed by FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (sample 1) and iCOFcap-1 with one-pot integration of FDH, RhCp*, and NAD+ (sample 2). The error bar of the sample refers to the standard deviation of three groups prepared at different times (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In practical applications, multiple enzymes are often required to cooperate with each other for advanced functions. However, it is difficult to quantify and regulate the rational proportion of multiple enzymes to boost catalytic performance using traditional enzyme immobilization strategies. Our strategy can achieve step-by-step enzyme transport to resolve limitations of quantification and regulation. To prove the concept of multi-enzyme cascade biocatalysis in COF capsules, FDH was first encapsulated in NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 capsule and then GDH (Fig. 5a). For FDH and GDH, load amounts were 280 mg g−1 and 200 mg g−1, respectively, which afforded optimal activities of 92% and 95% vs the respective free enzymes (Fig. 5c). By contrast, we also used the one-pot method to encapsulate FDH or GDH together into iCOFcap-1, and the loading amounts were 120 mg g−1 and 100 mg g−1, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 47–49 and Supplementary Methods 20–22). Obviously, the cascade catalysts fabricated by the transmembrane transport method showed much higher enzyme loading amount (>2.5 times or >2.0 times) and enzyme activity (>25% or >20%) compared with those using the one-pot encapsulating method. It should be noted that the one-pot method had some limitations, e.g., the COF crystallinity gradually decreased, and the morphology worsened with the increase of the enzyme amount, possibly due to the influence of the functional groups of enzymes (e.g., amino groups, carboxyl groups). To test for cascade reactions in iCOFcap-1, we encapsulated fluorescent-labeled FDH and GDH into iCOFcap-1. The CLSM images further verified the uniform dispersion of FDH and GDH in iCOFcap-1 capsules (Fig. 5b). The iCOFcap-1 retained good crystallinity after transporting FDH and GDH (Supplementary Fig. 50). The ratios of FDH:GDH in iCOFcap-1 were systematically studied (e.g., 1.0:0.5, 1.0:1.0, 1.0:2.0), revealing that FDH:GDH (1.0:1.0) showed the best performance (Fig. 5d). The product yield of FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 is significantly higher than that of corresponding free multi-enzyme systems (Supplementary Fig. 51). The product yield of FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 is significantly higher than that of FDH&NADH◎iCOFcap-1, which demonstrated the significance of the coenzyme regeneration system for continuous catalysis. (Supplementary Fig. 52). Meanwhile, the loading amount of FDH + GDH by stepwise co-immobilization was higher than that by simultaneous co-immobilization, and the product yield of FDH + GDH by stepwise co-immobilization was significantly higher than that by simultaneous co-immobilization (Supplementary Fig. 53). This heterogeneous catalyst had good reusability and achieved a good productivity of >80% after ten cycles (Supplementary Fig. 54 and Supplementary Method 23).

a The illustration of the synthesis of FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 and cascade biocatalysis of CO2 to formic acid. b The CLSM images of FDH&GDH◎iCOFcap-1. Scale bar: 1 μm. c The loading amount and relative activity of FDH◎iCOFcap-1 (stepwise), FDH◎iCOFcap-1 (one-pot), GDH◎iCOFcap-1 (stepwise), GDH◎iCOFcap-1 (one-pot). d The yield rate of HCOOH catalyzed by FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 with different ratios of FDH:GDH. The error bar of the sample refers to the standard deviation of three groups prepared at different times (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A key feature of this co-immobilization strategy is that it can combine the one-pot pre-encapsulation method with stepwise transmembrane transport method to immobilize multiple enzymes and chemocatalysts into one capsule, especially for the systems in which different catalyst moieties have different optimal immobilization conditions (e.g., chemocatalyst’s best condition is in organic solvents and can be pre-encapsulated by the one-pot method, while enzyme’s best condition is in buffer solution and can be immobilized via the stepwise transmembrane transport method). In a word, the integration of the one-pot pre-encapsulation method and stepwise transmembrane transport method can help enzymes and chemocatalysts maintain their optimal activity. To demonstrate the effect of immobilization methods on catalysis efficiency, we synthesized FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 by different formulations. Formulation 1: Co-encapsulated FDH and NAD+ by the one-pot method and GDH by the stepwise method. Formulation 2: Co-encapsulated GDH and NAD+ by the one-pot method and FDH by the stepwise method. Formulation 3: Co-encapsulated FDH, GDH, and NAD+ by the one-pot method. Formulation 4: encapsulated NAD+ by the one-pot method and GDH and FDH by the stepwise method (Fig. 6a). As shown in Fig. 6b, the performance of FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (Formulation 4) surpassed all other formulations. Notably, the comprehensive performance of FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 and FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (HCOOH yield: 2.05 and 1.61 mmol h−1 gmaterial−1, cycle time: 100 and 100 h, relative yield: 84% and 80%, respectively) surpassed all reported heterogeneous platforms with photoenzyme or multi-enzyme cascade systems (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table 1).

a The illustration of the synthesis of Formulation 1, Formulation 2, Formulation 3, and Formulation 4. b The yield rate of HCOOH catalyzed by Formulation 1, Formulation 2, Formulation 3, and Formulation 4. c The comprehensive performance of this work compared with reported heterogeneous platforms with photoenzyme cascade or multi-enzyme cascade. The error bar of the sample refers to the standard deviation of three groups prepared at different times (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In summary, we innovate a multi-enzyme and chemocatalyst co-immobilization strategy by mimicking the cell transmembrane transport using ionic COF capsules (iCOFcap). A series of iCOFcap could be fabricated using PEGylated linear polymers and positive/negative monomers as structural building blocks promoted by the PEG-driven LLPS effect. The iCOFcap can efficiently load enzymes by swelling and then transport them into the capsule cavity by charge reversal. This stepwise enzyme-transporting process was visualized in situ by SIM analysis. A systematic investigation revealed that the capacity and rate of enzyme transport could be adjusted by altering the content of PEGylated polymer or ionic monomers. Notably, due to the mild operation conditions, enzymes could achieve nearly complete retention of enzyme activity. Meanwhile, multiple enzymes can be transported into iCOFcap-1 with controllable proportions. Combining this stepwise transmembrane transport method with the one-pot pre-encapsulation method could afford various types of cascade catalysts of multiple enzymes and chemocatalysts with different formulations. For instance, the iCOFcap can co-immobilize Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O and NAD+ via the one-pot method and then transport FDH into the capsule cavity to build a photoenzymatic system for CO2 reduction. Being heterogeneous catalysts, FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 was able to generate 1.61 mmol h−1 g material−1 formic acid from CO2 under visible light irradiation and had facile recycling and recovery, and productivity of >84% after ten cycles. Overall, our multi-enzyme and photoenzymatic cascade catalytic system showed good comprehensive performance for CO2 conversion, superior to all reported heterogeneous catalysts using the same enzymes. This study innovates an immobilization strategy and provides an energy-efficient alternative for biotechnology applications.

Methods

Synthesis of iCOFcap-1/2 with different ratios of monomer

The DTH-400/600/800:BMTH:HPTMB/SDHS (0:21:9; 1:20:9; 3:18:9; 5:16:9; 10:11:9, 0.03 mmol) and water/chloroform mixture (V/V = 1.0/7.5 mL/mL) were added into a 50 mL bottle and stirred at >600 rpm for 10 min. Then, TB (3.3 mg, 0.02 mmol) was ultrasonically dissolved in 1.0 mL chloroform and 2.0 mL acetonitrile. The TB solution and Sc(OTf)3 aqueous solution (70 μL, 1.0 g/mL) were added to the DTH-400/600/800:BMTH:HPTMB/SDHS mixture by drops and stirred at room temperature for 50 min. At the end of the reaction, the product was collected by centrifugation at 6000×g for 10 min, washed three times with methanol, and the faint yellow solid was obtained by filtration.

Synthesis of lipase◎iCOFcap-1

The freeze-dried iCOFcap-1 (5 mg) was added to the lipase solution (6.0 mg/mL, PB buffer, 50 mM, pH = 7.0) for 6 h. And then, iCOFcap-1 loading lipase was added into PB buffer (50 mM, pH = 5.0) for 6 h. The product was collected by centrifugation at 6000×g for 10 min, washed three times with DI water, and freeze-dried to isolate the solid. After the encapsulation and washing process, the supernatant of each operation was collected, and the concentration of protein was quantified by following the standard protocol of the Bradford assay, before which the calibration curve of lipase was fitted. The loading efficiency (LE %) and the loading capacity (LC, g·g−1) were calculated as follows:

Synthesis of RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1

The DTH-600:BMTH:HPTMB (5:16:9, 0.03 mmol), Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O (9.9 mg), NAD+ (5.0 mg) and water/chloroform mixture (V/V = 1.0/7.5 mL/mL) were added into a 50 mL bottle and stirred at >600 rpm for 10 min. Then, TB (3.3 mg, 0.02 mmol) was ultrasonically dissolved in 1.0 mL chloroform and 2.0 mL acetonitrile. The TB solution and Sc(OTf)3 aqueous solution (70 μL, 1.0 g/mL) were added to the mixture by drops and stirred at room temperature for 50 min. At the end of the reaction, the solid was precipitated with 15 mL of methanol, and the faint yellow solid was obtained by filtration.

Synthesis of FDH&RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1

The freeze-dried RhCp*&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (5 mg) was added to 2.0 mL FDH solution (1.0 mg/mL, PB buffer, 50 mM, pH = 7.0) for 3 h. And then, iCOFcap-1 loading FDH was added into 2.0 mL PB buffer (50 mM, pH = 5.0) for 6 h. The product was collected by centrifugation at 6000×g for 10 min, washed three times with DI water, and freeze-dried to isolate the solid. The supernatants were detected at different time points using the Bradford method and quantified by the standard curve of BSA.

Synthesis of FDH&GDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1

The freeze-dried NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (5 mg) was added to the FDH solution (1.0 mg/mL, PB buffer, 50 mM, pH = 7.0) for 3 h. And then, iCOFcap-1 loading FDH was added into the PB buffer (50 mM, pH = 5.0) for 6 h. The product was collected by centrifugation at 6000×g for 10 min, washed three times with DI water, and freeze-dried to isolate the solid. The supernatants were detected at different time points using the Bradford method and quantified by the standard curve of BSA.

The freeze-dried FDH&NAD+◎iCOFcap-1 (5 mg) was added to the GDH solution (1.0 mg/mL, PB buffer, 50 mM, pH = 7.0) for 3 h. And then, iCOFcap-1 loading GDH was added into the PB buffer (50 mM, pH = 5.0) for 6 h. The product was collected by centrifugation at 6000×g for 10 min, washed three times with DI water, and freeze-dried to isolate the solid. The supernatants were detected at different time points with the Bradford method and quantified by the standard curve of BSA.

Photobiocatalytic conversion of CO2 into formic acid

Photobiocatalytic conversion of CO2 was conducted under 1 atm CO2 and 30 °C in a quartz reactor under visible light. The light could pass through the quartz window and reach the reaction solution. The reaction solution contains 5 mg integrated photocatalysts (containing NAD+ (1.0 mg), RhCp* (0.5 mg), and FDH (1.4 mg)), 5 wt% TEOA in 50 mL PB buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0) using a solar simulator (300 W Xe lamp, PLS-SXE300) outputting stable solar flux at 1.0 kW/m2 (1 sun). The supernatants were detected at different time points by ion chromatography (ThermoFisher, ICS-1100).

Conversion of CO2 into formic acid by a multi-enzyme cascade

Multi-enzyme catalyzing conversion of CO2 was conducted under 1 atm CO2 and 30 °C in a quartz reactor. The reaction solution contains 5 mg integrated catalysts, 5 wt% TEOA in 50 mL PB buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0). The supernatants were detected at different time points by ion chromatography (ThermoFisher, ICS-1100).

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessments. All experiments were performed at least three times with similar results.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials, and from corresponding author upon request. The corresponding authors will reply to the data requests within 4 weeks. Source data are provided with this paper in the Source Data file.

References

Ye, J.-W. et al. Synthetic biology of extremophiles: a new wave of biomanufacturing. Trends Biotechnol. 41, 342–357 (2023).

Intasian, P. et al. Enzymes, in vivo biocatalysis, and metabolic engineering for enabling a circular economy and sustainability. Chem. Rev. 121, 10367–10451 (2021).

Sheldon, R. A. & Woodley, J. M. Role of biocatalysis in sustainable chemistry. Chem. Rev. 118, 801–838 (2018).

Wu, S., Snajdrova, R., Moore, J. C., Baldenius, K. & Bornscheuer, U. T. Biocatalysis: enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 88–119 (2021).

Cai, X., Huang, Y. & Zhu, C. Immobilized multi-enzyme/nanozyme biomimetic cascade catalysis for biosensing applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 14, e2401834 (2024).

Wei, Y. et al. Boosting the photocatalytic performances of covalent organic frameworks enabled by spatial modulation of plasmonic nanocrystals. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 272, 119035 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Thylakoid membrane-inspired capsules with fortified cofactor shuttling for enzyme-photocoupled catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4168–4177 (2022).

Zhu, D. et al. Ordered coimmobilization of a multienzyme cascade system with a metal organic framework in a membrane: reduction of CO2 to methanol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 33581–33588 (2019).

Li, Z., Wan, Z., Wang, W., Chen, L. & Ji, P. Chemoenzymatic sequential catalysis with carbonic anhydrase for the synthesis of chiral alcohols from alkanes, alkenes, and alkynes. ACS Catal. 14, 8786–8793 (2024).

Sun, Q. et al. Pore environment control and enhanced performance of enzymes infiltrated in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 984–992 (2018).

Jin, C. et al. Enzyme immobilization in porphyrinic covalent organic frameworks for photoenzymatic asymmetric catalysis. ACS Catal. 12, 8259–8268 (2022).

Xing, C. et al. Enhancing enzyme activity by the modulation of covalent interactions in the confined channels of covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201378 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Green and scalable fabrication of high-performance biocatalysts using covalent organic frameworks as enzyme carriers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208744 (2022).

Hudson, S., Cooney, J. & Magner, E. Proteins in mesoporous silicates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 8582–8594 (2008).

Fried, D. I., Brieler, F. J. & Fröba, M. Designing inorganic porous materials for enzyme adsorption and applications in biocatalysis. ChemCatChem 5, 862–884 (2013).

Garrett, W. S. From cell biology to the microbiome: an intentional infinite loop. J. Cell Biol. 210, 7–8 (2015).

Liu, J., Guo, Z. & Liang, K. Biocatalytic metal-organic framework-based artificial cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1905321 (2019).

Lentini, R. et al. Integrating artificial with natural cells to translate chemical messages that direct E. coli behaviour. Nat. Commun. 5, 4012 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. PVP-assisted in situ immobilizing lipase on covalent organic framework for enhanced catalytic activity and stability in bioconversions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 283, 137856 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and A dendritic molecular binder. Nature 463, 339–343 (2010).

Dadsetan, M. et al. A stimuli-responsive hydrogel for doxorubicin delivery. Biomaterials 31, 8051–8062 (2010).

Qian, Y.-C., Chen, P.-C., Zhu, X.-Y. & Huang, X.-J. Click synthesis of ionic strength-responsive polyphosphazene hydrogel for reversible binding of enzymes. RSC Adv. 5, 44031–44040 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. PolyCOFs: a new class of freestanding responsive covalent organic framework membranes with high mechanical performance. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1352–1359 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Deformable and robust core–shell protein microcapsules templated by liquid–liquid phase-separated microdroplets. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2101071 (2021).

Zhu, Q. et al. COFcap2, a recyclable tandem catalysis reactor for nitrogen fixation and conversion to chiral amines. Nat. Commun. 16, 992 (2025).

Uribe-Romo, F. J., Doonan, C. J., Furukawa, H., Oisaki, K. & Yaghi, O. M. Crystalline covalent organic frameworks with hydrazone linkages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11478–11481 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0907300 to Y.C., Z.Z., and Q.Z.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC210210 to Y.C., Y.Z., and J.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22371136), and the Haihe Laboratory of Synthetic Biology (22HHSWSS00008 to H.H., Z.W., and Q.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. and Z.Z. initiated the project. Q.Z. developed the photoenzyme/multi-enzyme catalysis system and performed most of the experiments. Q.Z. and Y.Z. assisted in synthetic experiments. J.Y., J.L., H.H., Z.W., and Q.S. performed the TEM, HRTEM, and Confocal Characterization. Q.Z. wrote the original draft, with input from all authors. Z.Z., Y.C., and Q.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mingming Zheng, Guosheng Chen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Zheng, Y., Yu, J. et al. Biomimetic transmembrane transport of multi-enzymes to fabricate heterogeneous bioreactors with photoenzymatic reduction of CO2. Nat Commun 16, 11254 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66111-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66111-1