Abstract

Achieving adequate enteral nutrition among mechanically ventilated patients is challenging, yet critical. We develop NutriSighT, a transformer model using learnable positional encodings to predict which patients would be underfed (receive less than 70% daily caloric requirements) between days 3-7 of mechanical ventilation and compared its performance against XGBoost. Using retrospective data from two ICU databases (3284 patients from AmsterdamUMCdb for development and 6456 from MIMIC-IV for external validation), we included adults mechanically ventilated for at least 72 h. NutriSighT achieved AUROC of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.81 – 0.82) and AUPRC of 0.70 (95% CI: 0.70 – 0.72) internally. External validation yielded AUROC of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.75 – 0.76) and an AUPRC of 0.70 (95% CI: 0.69 – 0.70). In comparison, XGBoost achieved AUROC of 0.58 (95% CI: 0.58 – 0.59) and AUPRC of 0.48 (95% CI: 0.46 – 0.50). This approach may help clinicians personalize nutritional therapy in critical care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optimal enteral nutrition (EN) is vital for critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation to meet their metabolic needs while mitigating complications1,2. Critical care guidelines recommend initiating early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients, but there is heterogeneity in the recommended caloric targets for the first week of intensive care unit (ICU) stay. For example, the European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) advocates for underfeeding, as defined by receipt of nutrition with less than 70% daily caloric requirements during the first week of ICU stay, but the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommends a broader caloric intake range of 12 to 25 kcal/kg, encompassing both underfeeding and adequate nutrition3,4. This variation reflects the dynamic nature of critical illness and the challenges in determining optimal nutrition within this highly heterogenous patient population5,6,7,8. Delivering adequate nutrition in this population is further complicated by challenges such as gastrointestinal dysfunction, hemodynamic instability, and frequent interruptions for procedures9,10,11.

The first week of critical illness is divided into two distinct phases: the early acute period and the late acute period1,12. The early acute period spans the 48 h of critical illness and is marked by hemodynamic instability and acute illness response. The late acute period, spanning days 3-7, is characterized by muscle wasting and evolving nutritional needs though the timing of this transition likely varies amongst patients. Common clinical practice is to start a form of restrictive dose EN, such as trophic dose feeding, during the first 48 h and progressively increase nutritional support during the late acute period to meet the evolving metabolic demands of critically ill patients.

However, these strategies are not personalized, and highly individualized nature of critical illness highlights a pressing need for tools that can dynamically identify patients likely to receive specific nutrition regimens. Tools like modified NUTRIC score are available to identify critically ill patients who may benefit from nutritional therapy, but do not identify patients at risk for underfeeding13. Addressing these challenges requires innovative methods integrating diverse clinical and temporal data to adapt nutritional interventions effectively. A critical first step in this direction is to be able to identify patients at risk of underfeeding during ICU stay. In practice, underfeeding may result from both clinical factors and logistical factors. While some patients may benefit from underfeeding strategies, others may be unintentionally underfed, potentially worsening their outcomes5,7,14,15,16. Without tools to identify which patients are at risk of underfeeding in real time, clinicians are limited in their ability to tailor interventions or conduct targeted research on personalized nutrition strategies.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) can address these challenges17,18. Transformer models, known for their ability to model sequential data are powerful tools for analyzing clinical time series data18,19. The incorporation of learnable positional encoding18,19, enhances the model’s ability to understand temporal relationships. Unlike fixed positional encodings, learnable encodings enable the model to optimally represent temporal dynamics and address complex clinical scenarios, such as predicting which patients are at risk of underfeeding18,19.

In this study, we developed and externally validated an interpretable, transformer model, NutriSighT, to dynamically identify critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation who are at risk of underfeeding during the late acute period of their critical illness. By focusing on this aspect, NutriSighT aims to address key gaps in nutritional management by offering actionable insights into patient-specific needs.

Results

Patient characteristics

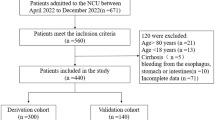

A total of 3284 patients from the AmsterdamUMCdb and 6456 patients from the MIMIC-IV databases met the inclusion/exclusion criteria7,16,17. As shown in Table 1, AmsterdamUMCdb cohort had a higher proportion of younger patients (11.15% vs 9.15% in 18–39 year; p < 0.001), males (64.58% vs 58.78%; p < 0.001) and a lower BMI (median 24.8 kg/m² vs 28.1 kg/m²; p < 0.001). Additional characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Enteral nutrition

Overall daily enteral nutrition support differed significantly between the AmsterdamUMCdb and MIMIC-IV cohorts. Patients in the AmsterdamUMCdb dataset received a median daily EN intake of 1440.0 mL (IQR: 1000.40–1723.80), compared to 756.48 mL (IQR: 228.72–1199.97) in MIMIC-IV (p < 0.001). This difference was also evident in the daily caloric intake derived from EN, which was notably higher in AmsterdamUMCdb (median: 1702.99 kcal, IQR: 1155.26–2039.66) relative to MIMIC-IV (median: 989.20 kcal, IQR: 291.74–1478.06; p < 0.001). When combining calories from EN and propofol, AmsterdamUMCdb patients still received more daily total calories, with a median of 1727.66 kcal (IQR: 1192.90–2059.41) compared to 1307.24 kcal (IQR: 705.00–1802.50) in MIMIC-IV (p < 0.001).

In contrast, MIMIC-IV patients received more daily propofol, reflected by both a higher volume (median 31.25 mL [IQR: 0.00–564.98] vs. 0.000 mL [IQR: 0.00–19.20]; p < 0.001) and more propofol-derived calories (34.38 kcal [IQR: 0.00–621.48] vs. 0.00 kcal [IQR: 0.00–21.12]; p < 0.001). The observed differences in enteral nutrition support and daily propofol usage between the AmsterdamUMCdb and MIMIC-IV cohorts likely reflect variations in sedation protocols and nutritional strategies between the European and United States healthcare systems.

The proportion of underfed patients decreased over the hospital course in both datasets (Table 2). On day 3, 40.8% of patients in AmsterdamUMCdb and 53.13% in MIMIC-IV were underfed. By day 7, these proportions declined to 25.39% and 35.33%, respectively.

NutriSighT performance

The overall modeling approach of NutriSighT is shown in Fig. 1. We evaluated NutriSighT’s performance across six days post-intubation (Table 3, Fig. 2). On the internal test set from AmsterdamUMCdb, the Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve (AUROC) started at 0.84 (95% CI: 0.83–0.84) on day 1 and was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.70–0.77) by day 6. External validation with the MIMIC-IV dataset revealed a similar trend, with an AUROC value of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.77–0.78) on day 1 and 0.70 (95% CI: 0.69–0.71) on day 6. The model demonstrated an overall AUROC of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.81–0.82) on the internal test set and 0.76 (95% CI: 0.75 − 0.76) on the external validation dataset, reflecting strong discriminatory performance. The Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.70–0.72) and 0.70 (95% CI: 0.69–0.70) for the internal test set and external validation datasets, respectively. Additionally, the Brier score on the external validation dataset was 0.21, indicating moderate accuracy in probability predictions.

Model comparison against XGBoost

To benchmark NutriSighT’s performance, we compared it to an XGBoost model trained using the same datasets, input structure, and evaluation metrics. As shown in Fig. 3, NutriSighT consistently outperformed XGBoost in both AUROC and AUPRC across all prediction days on both the internal test set (AmsterdamUMCdb) and external validation set (MIMIC-IV).

Performance of the NutriSighT (red) and baseline XGBoost (blue) models in predicting underfeeding over the first six days of mechanical ventilation. The top row shows performance on the internal test set, while the bottom row shows performance on the external validation set. Panels on the left display the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), and panels on the right display the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC). Solid lines represent the mean performance across all prediction tasks for a given day, and the corresponding shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals, calculated via bootstrapping.

On the internal test set, XGBoost achieved an AUROC of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.59–0.61) and an AUPRC of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.40–0.46) on day 1, and an AUROC of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.58–0.59) and an AUPRC of 0.35 (95% CI: 0.34–0.36) on day 6. On the external validation set, XGBoost achieved an AUROC of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.58–0.61) and an AUPRC of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.48–0.57) on day 1, and an AUROC of 0.56 (95% CI: 0.55 − 0.56) and an AUPRC of 0.39 (95% CI: 0.38–0.39) on day 6. The Brier score for the XGBoost model on the external validation dataset was 0.24. These results highlight the advantage of NutriSighT’s transformer-based architecture in modeling temporal dynamics and improving predictive performance for underfeeding in ICU patients.

To assess the calibration of the model’s predicted probabilities more thoroughly, we generated a calibration plot (Fig. 4), which compare the predicted probabilities with the observed outcomes across different probability bins. The X-axis represents the mean predicted probability of underfeeding, and the Y-axis shows the fraction of patients who were actually underfed within each probability bin. Figure 3 illustrates the calibration of the model on the external validation dataset. The plot shows that for probability bins below 0.5, the model’s predictions align closely with the observed outcomes, indicating good calibration in this range. However, for probability bins above 0.5, the model tends to overestimate the risk of underfeeding.

To determine optimal cutoff points for clinical decision-making, we further evaluated the model’s performance across various probability thresholds on the external validation data (Table 4). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated at thresholds ranging from 0.1 to 0.9. At a threshold of 0.5, the model achieved a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 61%, PPV of 58%, and NPV of 77%. As the threshold increased, sensitivity decreased while specificity increased, illustrating the trade-off between identifying true positives and minimizing false positives. For instance, at a threshold of 0.7, sensitivity decreased to 50%, but specificity increased to 83%, and PPV improved to 69%.

Feature importance

The mean absolute SHAP values (Fig. 5a) highlight serum sodium as the most influential feature across all predictions, followed by diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and pH. Other high-ranking features include propofol dose, temperature, WBC count, RBC count, and INR, indicating that the model relies heavily on sedative use, physiological and laboratory markers. Demographic variables like age, height and weight also contribute meaningfully to the model’s predictions. The patient-level SHAP heatmap (Fig. 5b) illustrates how feature contributions change across outcome Days 3 to 7 for an individual patient.

a The mean absolute SHAP value plot. b Patient-level SHAP heatmap showing how feature contributions to underfeeding predictions evolve across outcome Days 3–7. Each column reflects predictions made up to that day, highlighting dynamic, feature-specific shifts over time. For this patient, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), serum sodium, and height were consistently influential, with lower sodium and DBP levels associated with underfeeding predictions. International Normalized Ratio (INR) showed dynamic importance, contributing more strongly to predictions for Days 3–5 but less so for Days 6–7, suggesting diminishing relevance over time. A similar temporal shift is seen with lorazepam, which gained importance over time, with its absence corresponding to isocaloric nutrition predictions, consistent with the clinical expectation that less sedated patients are typically less ill and more likely to receive adequate feeding. BMI Body Mass Index, SpO2 Peripheral Oxygen Saturation, PaO2/FiO2 Ratio of Partial Pressure to fractional inspired oxygen, MCHC Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration, MCV Mean Corpuscular Volume, RBC Red Blood Cell, RDW Red Cell Distribution Width, WBC White Blood Cell, INR International Normalized Ratio, PTT Partial Thromboplastin Time, ALT Alanine Aminotransferase Activity, ALP Alkaline Phosphatase, AST Aspartate Aminotransferase, CK (CPK) Creatine Kinase Activity, CK-MB Creatine Kinase-MB Activity, LD (LDH) Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity, BP Blood Pressure, Na Sodium, DBP-I Invasive Diastolic Blood Pressure, HR Heart Rate, K Potassium, BIL-I Indirect Bilirubin, SBP-NI Non-Invasive Systolic Blood Pressure, MBP-I Invasive Mean Blood Pressure, NEE Norepinephrine Equivalent Doses, SBP-I Invasive Systolic Blood Pressure.

The temporal SHAP summary (Supplementary Fig. 2) reveals how feature importances evolve across prediction days. Serum sodium, DBP, MCV, and pH consistently rank as the most important contributors across the prediction days, indicating their stable and strong influence on model forecasts. In contrast, the P/F ratio gains prominence in later predictions, with lower values corresponding with higher risk of underfeeding, consistent with the clinical pattern that more severely ill patients are often underfed. Similarly, chloride and lactate also have dynamically evolving feature importances, gaining greater prominence in the predictions made later in the ICU course, with lower values linked to a lower predicted risk of underfeeding.

Discussion

We have developed and externally validated NutriSighT, an interpretable AI model using a novel transformer architecture to identify critically ill patients at risk of underfeeding in the late acute phase of their illness. The model was trained on AmsterdamUMCdb, a European dataset, and validated on MIMIC-IV, a US dataset, demonstrating its ability to generalize across diverse patient populations19,20,21,22. NutriSighT exhibited strong discriminatory performance, with robust AUROC scores across both internal and external datasets, indicating its ability to differentiate between patients at higher and lower risk accurately. Additionally, NutriSighT consistently outperformed XGBoost across both internal and external validation sets demonstrating superior performance in capturing temporal dependencies and adapting to the dynamic nature of ICU patient data. Calibration analysis revealed good alignment between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes.

The time-series nature of the data makes transformer architecture well-suited for capturing temporal dependencies and complex patterns18. This approach is ideal for predicting dynamic outcomes, such as underfeeding in critically ill patients. By modeling these temporal dynamics, NutriSighT can deliver timely and accurate predictions that adapt to changes in patient status. NutriSighT generates predictions every 4 h, providing clinicians with actionable time windows to adjust treatment plans as necessary. The model exhibited strong discriminative ability, as demonstrated by its AUC values, and its AUPRC and calibration further support its potential for clinical integration. These features enable NutriSighT to reliably identify patients at risk for underfeeding and guide timely interventions.

SHAP-based analysis revealed that core physiological and laboratory features such as serum sodium, diastolic blood pressure, MCV, and pH consistently contributed to underfeeding predictions. While these features remained influential throughout the ICU stay, others like the P/F ratio, chloride, and lactate gained importance in later predictions, reflecting the model’s dynamic adjustment to evolving clinical conditions. This individualized interpretability underscores NutriSighT’s ability to integrate both stable and time-sensitive information. It is important to note, however, that while SHAP values provide patient- and time-specific insights, they do not imply statistical associations23,24.

Despite the critical role of enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients, optimizing feeding strategies remains a challenge17. Prior studies have yielded inconsistent results on the impact of different feeding strategies in these patients, highlighting the complexity of optimizing nutritional interventions. For example, an observational study of over 2700 mechanically ventilated patients in 167 ICUs where most patients were underfed, found that an increase of 1000 kcal/day was associated with lower 60-day mortality and increased number of ventilator free days5. Lower mortality8,14,15 and shorter duration of mechanical ventilation6 with isocaloric nutrition has also been shown in other studies. Conversely, other studies have found either no differences in ventilator-free days, mortality, or infectious complications between the two nutritional strategies16, or found longer time to readiness for ICU discharge among patients receiving isocaloric nutrition7. These conflicting results likely reflect the heterogeneity of critically ill patients, highlighting the challenges of applying a one-size-fits-all approach to nutrition.

These discrepancies underscore the need for personalized nutrition approaches, particularly in the late acute phase of critical illness, when patient conditions and metabolic needs evolve rapidly. NutriSighT addresses this need by dynamically identifying patients who are likely to be underfed in the late acute phase. By providing a precise identification of these patients, NutriSighT can guide more personalized interventions and enrich clinical trials that explore the efficacy of tailored nutritional regimens. Furthermore, NutriSighT lays the groundwork for further research into barriers to implementation and strategies to personalize nutrition in this vulnerable patient population.

It is important to acknowledge that feeding decisions are influenced not only by patient physiology but also by clinician judgment, which may incorporate local protocols alongside many of the same parameters used by NutriSighT. Clinicians in the ICU are often required to make rapid decisions based on vast and fragmented streams of information25. In this context, NutriSighT can serve as a valuable decision-support tool by providing systematic and timely identification of patients at risk of underfeeding. The fact that the model draws on features already used in clinical reasoning, enhances transparency and fosters clinician trust.

NutriSighT is designed to be a real-time risk prediction tool that can continuously evaluate patients and predict the likelihood of underfeeding during their ICU stay. It can, thus, flag patients at risk for underfeeding well in advance, providing clinicians an actionable window to evaluate the reasons for underfeeding and adjust feeding strategies as necessary. For example, early in the ICU course, if a patient is identified to be at risk for underfeeding on day 3 but not after that, the clinician may decide to continue the current management plan. However, if a patient is identified to be at risk for persistent underfeeding, the clinician may consider changing the enteral nutrition formulation or switching to parenteral nutrition.

This study has some limitations. First, as a retrospective analysis, it is subject to inherent biases, including selection bias and potential confounding factors, which may affect the interpretation of results and limit real-world applicability. Additionally, training and validation of NutriSighT on Western ICU databases (AmsterdamUMCdb and MIMIC-IV) could further limit generalizability to settings with different clinical practices or resource constraints. Although NutriSighT demonstrated strong generalizability across both internal and external validation datasets, local retraining or fine-tuning may be required to accommodate differences in patient populations, nutritional protocols, and ICU workflows, particularly in low-resource or geographically diverse settings. Prospective multicenter validation is therefore essential to assess effectiveness in real-time clinical settings. Successful real-world deployment will also require seamless integration into electronic health record systems, with careful attention to embedding the model within existing clinical workflows in a manner that promotes clinician acceptance and minimizes alert fatigue. Similar implementation challenges have been addressed in prior deployments of clinical decision support tools, providing valuable insights for the integration of NutriSighT into routine care26,27. However, it showed good generalizability as supported by its strong performance across both internal and external validation datasets. Notably, the Brier score on the external validation set was 0.21 suggesting that its predicted likelihoods are reasonably well-calibrated to the actual outcomes. Second, like many studies in this field, caloric requirements are estimated using guideline recommendations rather than indirect calorimetry, as latter were unavailable. While this could introduce inaccuracies, it reflects real-world clinical practice where indirect calorimetry is rarely used, thereby enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Future prospective studies incorporating direct calorimetry data may provide deeper insights and further validate the model’s utility. Third, although this study focuses on dynamically identifying patients likely to be underfed, addressing the broader spectrum of nutritional risk including underfeeding, overfeeding, or interruptions in feeding requires further exploration. We also used a guideline-based threshold to define underfeeding, which, while consistent with current practice, does not account for individualized energy needs. Future studies are needed to develop patient-specific targets that better reflect the diverse metabolic demands of critically ill patients. This work represents an important step forward by paving the way for more nuanced approaches to personalized nutritional strategies in critically ill patients. Additionally, our focus in this study was specifically on identifying patients at risk of underfeeding as defined by receipt of inadequate nutrition during days 3–7 of mechanical ventilation. However, this represents only one aspect of nutritional management in critically ill patients, and future studies should explore the role of AI to optimize the balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in their nutritional support. Finally, the observed decline in model performance from day 1 to day 6 may be partly due to the decreasing sample size, as fewer patients remain on mechanical ventilation over time. In addition, evolving patient metabolic demands, changes in clinical trajectory, shifts in feature importance, and the expanding context window length could influence the model’s predictive accuracy at later time points. With a smaller number of patients later in the ventilation period, the model has fewer data points to make predictions, which can lead to a slight decrease in performance. Despite this, the model still demonstrates strong performance overall, highlighting its ability to identify at-risk patients early and throughout the ventilation period. Future work should investigate adaptive learning or data augmentation techniques to mitigate performance decline and enhance stability.

In conclusion, we developed NutriSighT, an interpretable transformer model designed to identify mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients likely to only be underfed. NutriSighT has the potential to facilitate timely nutritional interventions in critically ill patients. Future studies should focus on integrating this model into trial designs to identify high-risk patients and optimize their nutritional strategies.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai under protocol number STUDY-20-00338. All research was performed in accordance with all relevant ethical regulations. Informed consent was waived by IRB because the study used de-identified, publicly available data from the MIMIC and AmsterdamUMCdb database.

Data sources

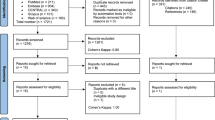

In this retrospective study we utilized data from two independent ICU datasets- the Amsterdam University Medical Centers Database (AmsterdamUMCdb) and the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV v2.2) (Fig. 1).

AmsterdamUMCdb is a highly granular ICU dataset from the European Union, containing deidentified electronic health records of ICU patients from the Amsterdam University Medical Centers in the Netherlands20. It includes admission data spanning 2003 to 2016 and encompasses approximately 1 billion data points including demographics, vital signs, laboratory tests and medications from over 20,000 ICU admissions. In contrast, MIMIC-IV is a United States based, single-center, de-identified database comprising electronic health records data from over 70,000 ICU admissions at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, with ICU admission data ranging from 2008 to 201921,22.

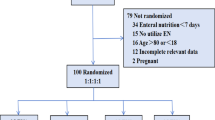

Study population

We included patients 18 years or older who were mechanically ventilated in the ICU for at least 72 h. Patients receiving total parenteral nutrition or peripheral parenteral nutrition during the ventilation event were excluded. We also excluded patients with missing height or weight data, or ambiguous data regarding tube feeds that did not allow us to calculate the amount of tube feeds administered (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Outcomes

The main aim of this study was to identify patients likely to be underfed on a given day between days 3-7 of mechanical ventilation among ICU patients. Predictions were censored to the day prior if a patient was extubated, died, or transferred out of the ICU.

Consistent with the recommendations of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) guidelines11, we estimated caloric requirements using weight-based equations adjusted according to the patient’s Body Mass Index (BMI) as below:

-

For patients with BMI < 30 kg/m²: 25 kcal per kilogram of actual body weight per day.

-

For patients with 30 ≤ BMI ≤ 50 kg/m²: 11 kcal per kilogram of actual body weight per day.

-

For patients with BMI > 50 kg/m²: 22 kcal per kilogram of adjusted body weight per day.

-

For BMI > 50 kg/m², adjusted body weight (kilogram) was calculated as28,29:

-

Females: 45.36 + 2.27 × (Height (cm) − 152.4)

-

Males: 48.08 + 2.72 × (Height (cm) − 152.4)

Underfeeding was defined as receipt of less than 70% of the calculated caloric requirements on a given day17,30, with caloric intake determined by a combination of enteral nutrition and propofol.

Feature extraction

We extracted a comprehensive set of features from the AmsterdamUMCdb and MIMIC-IV databases to capture the clinical characteristics of ICU patients. The features were chosen based on clinical relevance and routine availability in ICU workflows to support real-world applicability of the model26. The data was collected starting from the time of ICU admission or the time of intubation, if the latter occurred after ICU admission. It continued for up to 7 days after the start of mechanical ventilation, with earlier censoring in the case of extubation, death, or transfer out of the ICU. The features included demographics, vital signs, laboratory results, medications administered, enteral nutrition, fluid intake, and fluid output. Demographics included age, sex, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI). Vital signs included heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, mean arterial pressure, respiratory rate, and temperature. Laboratory results included oxygen saturation and PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, pH, base excess, lactate, sodium, potassium, chloride, anion gap, hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, red blood cell count, white blood cell count, platelet count, red cell distribution width, international normalized ratio, partial thromboplastin time, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, indirect bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, amylase, creatine kinase, CK-MB, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. We also included data regarding medications administered, such as vasopressors (in norepinephrine equivalent doses), sedatives and analgesics (lorazepam, morphine, propofol), and prokinetics (erythromycin and metoclopramide)31. We further extracted the amount of enteral nutrition administered and calories delivered by enteral nutrition and propofol.

Data pre-processing

To capture the temporal changes during each patient’s ICU stay, we structured the data into 4-hour time intervals, starting from the time of ICU admission or the time of intubation, if the latter was after ICU admission and ending at the earlier of extubation or 7 days after intubation. Clinical variables were summed or averaged within each time interval as appropriate. We excluded features with more than 40% missingness to ensure data quality and reliability, following standard practices in data analysis32. Outliers were identified and excluded based on clinical expertise, removing data points that were physiologically implausible or indicative of measurement errors.

Consistent with standard methods for handling missing data in these datasets, we used forward fill imputation for all features (except for medications administered, fluid intake, and enteral nutrition which were treated as zero when missing) and applied k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) imputation (k = 5) to fill in any remaining missing values33,34,35.

As AmsterdamUMCdb provides age, height, and weight in pre-defined subgroups (Table 1), we applied a similar approach in MIMIC-IV and encoded them using one-hot encoding to transform them into a binary format suitable for the model. Continuous variables were standardized using z-score normalization to ensure that all features contributed equally to the model training and to facilitate the convergence of the optimization algorithm. This step transformed the variables to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, reducing the risk of features with larger numerical ranges dominating the learning process.

Model development

At the core of NutriSighT’s functionality is its capability of making predictions at every 4-hour interval. At each timestep, the model updates its assessment based on the most recent patient data and predicts the feeding status separately for Days 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. These predictions are censored up to the day before the earliest occurrence of extubation, death, or discharge from the ICU, ensuring that the predictions remain relevant to the patient’s current clinical trajectory.

The model input comprises sequential data structured into 4-hour intervals, spanning up to seven days of mechanical ventilation. Each input sequence has a shape 36 ×62 (the number of 4-hour time bins over 6 prediction days by the number of clinical features). Traditional transformer models use fixed sinusoidal positional encodings to incorporate the order of input sequences18. However, we implemented a learnable positional encoder, which allows the model to learn optimal positional representations during training36. This approach adds trainable positional embeddings to the input sequences, enabling the model to better capture temporal dynamics and improve performance on sequential tasks.

NutriSighT is comprised of four stacked Transformer Encoder Blocks, each featuring multi-head self-attention mechanisms with four heads and a head size of 512. This architecture handles sequential data by capturing long-range dependencies through self-attention, enhancing the model’s ability to discern complex temporal patterns inherent in clinical data18,19. Following the self-attention layers, dropout layer normalization are applied. Following the transformer encoder layers, the model integrates a series of Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) Layers with 312, 64, and 48 units, respectively. Each dense layer is accompanied by dropout (35%) and L2 regularization (10-5). The final output layer employs a sigmoid activation function, generating probabilistic predictions for each outcome day.

These strategies were employed to prevent overfitting and optimize convergence, ensuring that NutriSighT effectively generalizes to unseen data. The combination of transformer architecture, learnable positional encodings, and robust regularization techniques enables NutriSighT to deliver accurate and timely predictions, thereby facilitating personalized nutritional interventions in the ICU setting.

Rolling prediction framework

The prediction schedule followed a dynamic, rolling approach as below (Fig. 6):

-

Days 1 and 2: Predicted feeding status for each day from Day 3 to Day 7, with prediction updated every 4 h.

-

Day 3: Predicted for each day from Day 4 to Day 7, updated every 4 h.

-

Day 4: Predicted for each day from Day 5 to Day 7, updated every 4 h.

-

Day 5: Predicted for Days 6 and 7, updated every 4 h.

-

Day 6: Predicted for Day 7, updated every 4 h.

This approach ensured continuous updates, allowing clinicians to adapt nutritional strategies proactively. By predicting multiple days ahead at each timestep, the model supports better planning and timely interventions.

Training and validation

We split the AmsterdamUMCdb dataset into a training set (80%), an internal validation set (10%), and an internal test set (10%). The internal validation set was used during training to prevent overfitting and tune hyperparameters. To address class imbalance, we employed class weighting, a technique that adjusts the contribution of each class to the loss function during training37. Specifically, we calculated class weights inversely proportional to the frequency of positive and negative outcomes, assigning higher weights to the minority class and lower weights to the majority class. By modifying the loss function in this way, the model was encouraged to pay greater attention to underrepresented outcomes. This approach reduced the risk of the model disproportionately favoring the majority class and thus helped the model learn patterns associated with both outcomes more effectively.

We trained the model using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 5×10⁻⁶ and applied early stopping and learning rate reduction callbacks to prevent overfitting and optimize training time. To ensure that the performance was clinically meaningful, we evaluated the model on the internal test set and external validation set using metrics sensitive to class imbalance, such as precision and recall. These metrics reflect the model’s ability to not only classify patients accurately but also to reliably identify those at highest risk, thereby enhancing the real-world utility of our predictive framework.

Comparison against XGBoost

To benchmark NutriSighT’s performance, we developed an XGBoost model using the same datasets and evaluation framework. We trained one XGBoost model per timestep, using cumulative data from all prior timesteps. This ensured both models operated on equivalent input information at each timestep, preserving temporal consistency. XGBoost was trained using the same datasets as NutriSighT, with the AmsterdamUMCdb used for training and as an internal test cohort, and MIMIC-IV as the external validation dataset.

Model performance was assessed using AUROC and AUPRC, identical to NutriSighT, enabling a direct comparison with NutrSighT. By maintaining these consistent training and evaluation procedures, we aimed to ensure that the comparison between NutriSighT and XGBoost was meaningful.

Statistical analysis

We assessed model performance using several statistical metrics to evaluate its predictive accuracy and generalizability. The Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve (AUROC) was used to evaluate the model’s ability to discriminate between patients who would and would not be underfed. The Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) was calculated to assess the trade-off between precision and recall.

To assess feature importance and provide insight into the decision-making process of NutriSighT, we employed SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values23,24. SHAP offers a model-agnostic framework that attributes the contribution of each input feature to a specific model output. We provide 3 specific SHAP visualizations: 1) Mean absolute SHAP values that summarize global feature importance across all patients and all predictions, 2) Temporal SHAP summary that shows how contributions of the top 20 features evolve across prediction days during the ICU stay, 3) Patient-level SHAP heatmaps that illustrate day-by-day changes in the top 10 contributing features for a representative patient.

To evaluate the calibration of the model’s predicted probabilities, we computed the Brier score and generated calibration plots, which visually assess how closely predicted probabilities align with actual outcomes across probability bins. Comparative statistical analyses were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. The trained model was externally validated on the MIMIC-IV dataset to assess its generalizability across different patient populations and clinical settings. This external validation ensured that the model’s performance is robust and applicable to diverse ICU environments.

Software

We performed all analyses in Python 3.10 using: pandas 2.2.2, numpy 1.26.4, TensorFlow 2.17.1, scikit-learn 1.6.0, XGBoost 1.7.4, matplotlib 3.8.0, seaborn 0.13.2, and SHAP.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available resources. The Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database (version 2.2) is available on the PhysioNet repository at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/. Access to this dataset requires user registration and completion of a recognized human subjects research training course. The Amsterdam University Medical Centers Database (AmsterdamUMCdb) is available to researchers upon request at https://amsterdammedicaldatascience.nl/, by registering at the Amsterdam Medical Data Science portal, completing required data protection training, agreeing to the data use agreement, and submitting a brief research proposal that explains the intended analyses. Access may be granted to qualified researchers (academic, clinical, or non-profit) for ethically approved projects. All data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are available in the article and in the Supplementary Information and from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used for the analysis in this study is available on GitHub at https://github.com/mjangda3/NutriSighT.

References

Singer, P. et al. Espen guideline on Clinical Nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 38, 48–79 (2019).

Weijs, P. J. et al. Optimal protein and energy nutrition decreases mortality in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 36, 60–68 (2011).

Singer, P. et al. Espen practical and partially revised guideline: Clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 42, 1671–1689 (2023).

Compher, C. et al. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 46, 12–41 (2022).

Alberda, C. et al. The relationship between nutritional intake and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: Results of an international multicenter observational study. Intensive Care Med. 35, 1728–1737 (2009).

Lee, J., Kim, M., Choi, D., Kwon, J. & Park, Y. K. Isocaloric nutritional support reduces ventilator duration time in major trauma patients. Nutr. Diet. 80, 435–444 (2023).

Reignier, J. et al. Low versus standard calorie and protein feeding in ventilated adults with shock: A randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group trial (NUTRIREA-3). Lancet Respiratory Med. 11, 602–612 (2023).

Lv, C. et al. Association between caloric adequacy and short-term clinical outcomes in critically ill patients using a weight-based equation: Secondary analysis of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Front. Nutr. 9, 902986 (2022).

O’Leary-Kelley, C. M., Puntillo, K. A., Barr, J., Stotts, N. & Douglas, M. K. Nutritional adequacy in patients receiving mechanical ventilation who are fed enterally. Am. J. Crit. Care 14, 222–231 (2005).

Elke, G., Wang, M., Weiler, N., Day, A. G. & Heyland, D. K. Close to recommended caloric and protein intake by enteral nutrition is associated with better clinical outcome of critically ill septic patients: Secondary analysis of a large International Nutrition Database. Crit. Care 18, R29 (2014).

McClave, S. A. et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the adult critically ill patient. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 40, 159–211 (2016).

Ridley, E., Gantner, D. & Pellegrino, V. Nutrition therapy in critically ill patients- a review of current evidence for clinicians. Clin. Nutr. 34, 565–571 (2015).

Heyland, D. K., Dhaliwal, R., Jiang, X. & Day, A. G. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: The development and initial validation of A Novel Risk Assessment Tool. Crit. Care 15, R268 (2011).

Coruja, M. K., Antunes, L. da, Leotti, V. B. & Steemburgo, T. Nutrition adequacy in the late period of the acute phase is associated with a lower risk of 30-day mortality in critically ill patients: A prospective cohort study. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 39, 945–956 (2024).

Heyland, D. K., Cahill, N. & Day, A. G. Optimal amount of calories for critically ill patients: Depends on how you slice the cake!*. Crit. Care Med. 39, 2619–2626 (2011).

Rice, T. W. et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: The Eden Randomized Trial. JAMA: J. Am. Med. Assoc. 307, 795–803 (2012).

Shillan, D., Sterne, J. A., Champneys, A. & Gibbison, B. Use of machine learning to analyse routinely collected intensive care unit data: A systematic review. Crit. Care 23, 284 (2019).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

Xu, Y., Xu, S., Ramprassad, M., Tumanov, A. & Zhang, C. TransEHR: Self-Supervised Transformer for Clinical Time Series Data. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 225, 623–635 (2023).

Thoral, P. J. et al. Sharing ICU patient data responsibly under the Society of Critical Care Medicine/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Joint Data Science Collaboration: The Amsterdam University Medical Centers Database (amsterdamumcdb) example*. Crit. Care Med. 49, e563–e577 (2021).

Johnson, A. E. et al. Mimic-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10, 1 (2023).

Johnson, A. et al. MIMIC-IV. PhysioNet. https://doi.org/10.13026/6MM1-EK67 (2023).

Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning (Lulu com, 2020).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Neural Information Processing Systems 4768–4777 (2017).

Manor-Shulman, O., Beyene, J., Frndova, H. & Parshuram, C. S. Quantifying the volume of documented clinical information in critical illness. J. Crit. Care 23, 245–250 (2008).

Timsina, P. et al. Must-plus: A machine learning classifier that improves malnutrition screening in acute care facilities. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 40, 3–12 (2020).

Nevin, C. et al. Acceptance of acute kidney injury alert by providers in Cardiac Surgery Intensive Care Unit. Appl. Clin. Inform. 14, 119–127 (2022).

Pai, M. P. & Paloucek, F. P. The origin of the “ideal” body weight equations. Ann. Pharmacother. 34, 1066–1069 (2000).

Esteva, A. et al. A guide to deep learning in Healthcare. Nat. Med. 25, 24–29 (2019).

Wischmeyer, P. E. et al. Personalized nutrition therapy in critical care: 10 expert recommendations. Critical Care 27, 10.1186/s13054-023-04539-x (2023).

Goradia, S., Sardaneh, A. A., Narayan, S. W., Penm, J. & Patanwala, A. E. Vasopressor dose equivalence: A scoping review and suggested formula. J. Crit. Care 61, 233–240 (2021).

Takkavatakarn, K. et al. Machine learning derived serum creatinine trajectories in acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with sepsis. Crit. Care 28, 156 (2024).

Komorowski, M., Celi, L. A., Badawi, O., Gordon, A. C. & Faisal, A. A. The Artificial Intelligence Clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nat. Med. 24, 1716–1720 (2018).

Raghu, A., Komorowski, M., Celi, L. A., Szolovits, P. & Ghassemi, M. Continuous state-space models for optimal sepsis treatment: a deep reinforcement learning approach. Proc. 2nd Mach. Learn. Healthc. Conf. 68, 147–163 (2017).

Gupta, M. et al. An extensive data processing pipeline for MIMIC-IV. Proc. Mach. Learn Res 193, 311–325 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Behrt: Transformer for electronic health records. Sci. Rep. 10, 7155 (2020).

Haibo, H. & Garcia, E. A. Learning from imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 21, 1263–1284 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K08DK131286 awarded to Ankit Sakhuja. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.J., J.P., A.S. Funding acquisition: A.S. Methodology: M.J., A.S. Data curation: M.J., A.S. Data analysis: M.J., A.S. Interpretation of data and analysis: M.J., J.P., J.D., P.M., R.G., J.G., D.P., N.K., S.B., E.K., R.F., A.M., J.O., L.C., M.S.F., A.W.C., R.K.S., G.N.N., A.S. Drafting of manuscript: M.J., A.S. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M.J., J.P., J.D., P.M., R.G., J.G., D.P., N.K., S.B., E.K., R.F., A.M., J.O., L.C., M.S.F., A.W.C., R.K.S., G.N.N., A.S. Supervision: G.N.N., A.S. Final approval of the version to be published: M.J., J.P., A.V., J.G., P.M., J.D., R.G., D.P., N.K., S.B., E.K., R.F., A.M., J.O., L.C., M.S.F, A.W.C, R.K.S., G.N.N., and A.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: GNN is a founder of Renalytix, Pensieve, Verici and provides consultancy services to AstraZeneca, Reata, Renalytix, Siemens Healthineer and Variant Bio, serves a scientific advisory board member for Renalytix and Pensieve. He also has equity in Renalytix, Pensieve and Verici. LC is a consultant for Vifor Pharma INC and has received honorarium from Fresenius Medical Care. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Rodolfo Sardone, Jiajia Lin, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jangda, M., Patel, J., Vaid, A. et al. NutriSighT: Interpretable Transformer Model for Dynamic Prediction of Underfeeding Enteral Nutrition in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Nat Commun 16, 11189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66200-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66200-1