Abstract

The human immune system has evolved to interact with various commensal and pathogenic bacteria in intricate and nuanced ways. While the diversity of bacteria presents fundamental challenges in understanding immune-microbe interactions, it also offers ample opportunities for developing effective immunomodulatory therapies. Here we show microbial product cocktails as an alternative class of immunotherapy for cancer. Using freshly resected tumors from bladder cancer patients, an immuno-comparative analysis of recruitment and enhancement assay, and an artificial intelligence-guided optimization workflow, we establish a personalized platform for identifying potent microbial product cocktails that promote recruitment, infiltration, and activation of immune cells for cancer treatment. In an orthotopic mouse bladder cancer model, microbial product cocktails demonstrate immunoenhancement and improve survival rates compared with standard bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

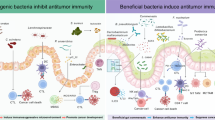

Bacteria interact with our body in complex and multifaceted ways. Advancements in high-throughput sequencing over the past two decades have begun to unveil the critical roles of microbes in human physiology. Commensal and pathogenic bacteria are associated with progression and treatment response of various cancers1. The success of fecal microbiota transplantation in improving immunotherapy response in melanoma patients has highlighted the therapeutic potential of modulating microbe-immune interactions2,3. Historically, microbes have been recognized as an effective antitumor strategy. In 1868 and 1882, Busch and Fehleisen demonstrated that bacterial infection, in particular Streptococcus pyogenes, induced tumor regression4,5. In 1891, Coley demonstrated heat-killed streptococcal organisms combined with heat-killed Serratia marcescens for the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas6. Notably, heat killed organisms were used to avoid the morbidity and mortality associated with live Streptococcus. The microbial products (known as Coley’s toxins) resulted in over 10-year disease-free survival in ~30% of patients despite controversies in toxin production and standardization7.

Despite the long-recognized antitumor activities of bacteria, intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) for high risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is currently the only established bacterial cancer immunotherapy. BCG is an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis that has been used as a vaccine for tuberculosis for over 100 years8. BCG is arguably one of the most successful cancer immunotherapies, reducing the risk of NMIBC recurrence to muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC)9. Following intravesical administration, BCG triggers an inflammatory reaction involving a humoral immune response (e.g., IL-2, IL-8, IL-18, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) and both innate and adaptive immunities (e.g., NK cells, CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, and granulocytes)10,11. An initial complete response to BCG occurs in 55–65% of patients with high-risk papillary tumors and 70–80% of patients with carcinoma in situ (CIS)12. However, BCG fails in about 40% of patients, and 20–27% discontinue due to serious adverse events or intolerance13,14. Patients who fail BCG therapy are at high risk for recurrence and progression to MIBC. Radical cystectomy and urinary diversion (e.g., ileal conduit or neobladder) are recommended for these patients. For BCG-unresponsive patients who decline or are poor cystectomy candidates, salvage intravesical chemotherapy (e.g., mitomycin, gemcitabine, sequential docetaxel-gemcitabine) may be offered and has a complete response rate of 8–25%15,16,17. Systemic immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) is also approved for patients with BCG-unresponsive CIS who declined cystectomy but only has a 20% response rate15. These poor treatment response rates underscore an urgent need for advanced approaches to the management of bladder cancer.

This study aims to develop a distinct class of immunotherapy based on microbial product cocktails (MPCs). The production of small molecules and metabolites by commensal and pathogenic bacteria can create local and systemic inflammatory responses18. Many microbial-associated molecular patterns, such as lipopolysaccharides, outer membrane protein, peptidoglycans, flagellin, microbial RNA, and CpG DNA, can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors and enhance immunogenicity19. Microbial products offer advantages compared to treatments based on live bacteria, such as fecal microbiota transplantation and vaccines. Firstly, they provide controllability, allowing precise management of dosage, duration, and the selection of microbes, including pathogenic bacteria. Secondly, their versatility allows the mixing and matching of different microbial products. This versatility is advantageous as microbial diversity is often associated with health benefits20. Synergistic combinations may also increase efficacy and reduce toxic side effects21. Lastly, microbial products enhance safety by eliminating the risks associated with unknown microbes and their potential for uncontrolled proliferation or mobility22.

The development of microbial immunotherapies encounters critical challenges due to tumor heterogeneity and the complex interactions between microbes, tumors, and the immune system. Despite the advancement of cancer immunotherapies, the response rate for solid cancers can be as low as 10–30% due to cancer heterogeneity and various resistance mechanisms23,24. Predicting which patients will respond favorably to treatment has been a challenging task. Additionally, selecting the proper microbial products is fundamentally difficult because of the delicate balance between immune activation and inhibition activities by microbes. While the large number of available bacteria can potentially be adopted for targeting a wide variety of immunomodulation applications, this abundance creates a combinatorially large search space for optimizing the composition and dosage of each microbial product25,26.

In this work, we establish a personalized platform for selecting effective MPCs for the immunotherapy of bladder cancer to harness the unexplored potential of microbial immunomodulation (Fig. 1A). This platform applies an immuno-comparative analysis of recruitment and enhancement (iCARE) assay based on patient-derived tumor organoids from the most common bladder cancer surgery called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). This multiplex microfluidic assay is designed to phenotypically capture the immunogenicity of tumor samples stimulated with microbial products in a competitive manner. The efficacy of microbial products is determined by measuring the chemotactic recruitment of immune cells into tumor organoids. To tackle the challenge of selecting potent MPCs from the large number of possible combinations22,23, we establish an AI-guided optimization workflow for selecting potent cocktails. This workflow leverages the data from the iCARE assay and a neural network model to guide the selection of promising MPC candidates. We demonstrate the iCARE assay’s capability to evaluate immunogenicity and select potent MPCs in self-assembled spheroids and freshly isolated tumor organoids. We further evaluate the efficacy of MPC immunotherapy in an established MB49 murine orthotopic bladder cancer model27,28. We show that MPC immunotherapy can outperform the standard BCG immunotherapy in median survival times and overall survival rates. Our results reveal MPCs as a promising immunotherapeutic strategy for cancer, potentially creating an alternative class of cancer immunotherapy.

A The iCARE assay uses patient-derived tumor organoids to screen AI-optimized MPCs, generated from commensal bacteria and pathogens, for immunoenhancement activities. Potent MPCs are selected for personalized cancer immunotherapy. B Isometric view of the multilayer device with a 16-well configuration, featuring a lower cancer cell chamber and an upper immune cell chamber separated by a collagen-coated porous membrane. C Cross-sectional view showing the chemotactic migration of immune cells through the membrane toward the tumor organoids in a comparative setup. 3D renderings illustrating various immune-tumor interactions: (D) recruited (d > 0), (E) in contact (d = 0), and (F) infiltrated (d < 0). Fluorescence images showing NK cell recruitment by: (G) spheroids self-assembled from the bladder cancer cell line UM-UC-1, (H) spheroids derived from stage T3b primary muscle invasive bladder cancer cells DT2153, and (I) patient-derived tumor organoids from T2 muscle invasive bladder cancer PPS10, with NK cells highlighted in green. Representative images from more than three independent biological replicates are shown. Scale bars, 50 μm for (D, G-I), and 10 μm for (E, F).

Results

Immuno-comparative analysis of recruitment and enhancement

We established a multiplex microfluidic assay, termed iCARE, to evaluate the immunogenicity of patient-derived tumor organoids and the immunoenhancing effects of MPCs. The primary endpoint of the assay is immune cell recruitment, which serves as the basis for selecting MPCs with strong immunoenhancement potential. The device consisted of a lower, multiwell chamber for tumor organoids or spheroids self-assembled by cancer cells, and an upper chamber for immune cells, separated by a collagen-coated porous membrane (Fig. 1B-C and Supplementary Fig. S1). In this assay, immune cells driven by chemokines secreted by cancer cells were recruited from the upper chamber to the lower chamber through chemotaxis. The scalable platform can be implemented in different formats. In a typical format in this study, the device consisted of a 16-well chamber with 6 independent repeats (Supplementary Fig. S1). The MPCs, which constitute conditioned media from probiotics, common pathogens, and uropathogenic bacteria, were applied in random positions within the repeats to avoid any bias due to position dependence. The potent MPCs were then retested in 4-well or other formats to confirm the efficacy. In addition to recruitment, the assay can also assess immune–tumor interactions, such as immune cell infiltration. We categorized immune cell infiltration within tumor organoids by 3D reconstruction of confocal images and assessed the spatial relationship (distance, d) between organoids and immune cells to classify them as recruited (d > 0), in contact/excluded (d = 0), or infiltrated (d < 0) (Fig. 1D-F). The assay was compatible with various tumor sample formats, including spheroids self-assembled from cancer cell lines, spheroids self-assembled from primary bladder cancer cells, and freshly isolated tumor organoids derived from TURBT samples (Fig. 1G-I).

In this study, we primarily targeted the recruitment of NK cells (NK-92MI) due to their functions in recognizing tumor cells, serving as innate effectors, and modulating key players (e.g., T cells) of the adaptive immune system29,30. Importantly, NK cell infiltration is associated with improved survival of both NMIBC and MIBC31. NK cell activation has also been shown to be essential for effective BCG immunotherapy. The ability of the iCARE assay to evaluate the recruitment of NK cells was first validated using spheroids self-assembled from established bladder cancer cell lines. The assay captured the NK cell recruitment capability of the bladder cancer cells, correlating with cell type enrichment scores derived from RNA sequencing (Supplementary Fig. S2)32. The iCARE assay was also validated using the transwell assay, i.e., Boyden chamber, and an immune tug-of-war device (Supplementary Fig. S3). The assay successfully captured the reduced ability of UM-UC-1 FOXA1 knockout cells, which exhibited reduced production of cytokines (e.g., IL-8, CXCL15, CCL20, and CXCL1), in NK cell recruitment. These results support the iCARE assay’s ability to evaluate the immunogenicity of cancer cells.

AI-guided workflow for optimization of MPCs

We developed an AI-optimization workflow that integrates experimental characterization of immunomodulation using iCARE and a neural network regression model to select optimal combinations of microbial products and dosages, streamlining the identification of potent MPCs (Fig. 2A). The microbial products were produced by inoculating bacteria, including probiotics, common bacteria, and uropathogens, in cell culture media for 48 h and then filtering out the bacteria (Supplementary Fig. S4A-B). The conditioned media containing microbial products were tested individually and in combination as MPCs (with the same total volume) for their abilities to enhance NK cell recruitment against UM-UC-1 spheroids. Microbial products from B. longum, L. acidophilus, and S. saprophyticus showed immunoenhancement activities while products from P. aeruginosa and L. plantarum 15697 appeared to attenuate immune recruitment (Fig. 2B). Potent combinations like B. longum and E. coli were noted (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S4C), while some combinations also displayed antagonistic effects. Combinations of three microbial products, such as some involving B. longum, L. plantarum 15697, and L. acidophilus, showed strong effects (Supplementary Fig. S4D). Furthermore, adding microbial products to wells without cancer cells did not result in any immune cell recruitment, suggesting the involvement of cancer cells in the process.

A Workflow for AI-guided MPC optimization. B Heatmap illustrating NK cell (NK-92MI) recruitment by UM-UC-1 spheroids in response to individual microbial products. C Heatmap comparing NK cell recruitment with combinations of microbial products, illustrating interactions between microbial products. D Schematic of the neural network model used to predict immunorecruitment activities of MPCs, generated using NN-SVG (MIT License; associated publication licensed under CC BY 4.0). E Heatmap of the 60 highest output combinations, showcasing the most effective MPCs as predicted by the neural network model, and a heatmap of the 60 lowest output combinations, highlighting those MPCs with lesser effectiveness as predicted by the model. NK cell recruitment-enhancing capabilities of MPC1-12 on UM-UC-1 cells tested in (F) the 16-well microwell device and (G) the 4-well format for selected MPCs. NK cell recruitment-enhancing capabilities of MPC1-12 on primary patient cancer cells (H) DT2101, (I) DT2334, (J) DT2153, and (K) DT2196. These samples cover MIBC from stage T2 to stage T4. Data are presented as mean ± SE. P values were derived by the Welch T test, ns P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. n = 4, independent biological replicate experiments in (G) and n = 3, independent biological replicate experiments in all other experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A neural network model was developed to predict potent MPCs based on the experimental recruitment data (Fig. 2D). The input vector presented to the model represents the dosages of individual microbial products, while the output corresponds to the number of NK cells recruited, as measured by the in vitro assay. Rather than predicting the input-output relationship accurately, the machine learning model aimed to extrapolate potentially effective combinations that can be further tested experimentally. The dataset covering NK cell recruitment activities of individual microbial products and combinations of microbial products with iCARE was randomly divided into two distinct subsets for training and testing (Supplementary Fig. S4E-F). After training and testing, the trained model was employed to predict potent combinations expected to yield effective immune recruitment. The workflow evaluated 100,000 randomly generated MPCs within a discrete search space, exploring diverse combinations of microbial product composition and dosage. Two rounds of neural network modeling and selection were performed. Heatmaps highlight the top and bottom 60 combinations predicted by the model (Fig. 2E). In particular, B. longum appeared in most of the top MPCs and was prevalent with either the combination of S. saprophyticus and E. faecium or S. epidermidis and E. faecalis in the most effective combinations. In contrast, antagonistic cocktails predicted by the model predominantly included some combinations of L. plantarum 15697, L. plantarum 14917, L. acidophilus, and S. aureus.

Guided by the experimental data (Fig. 2B-C) and neural network predictions (Fig. 2E), we selected MPCs with varying representation (e.g., derived from individual microbes or combinations of multiple microbes) and microbial diversity. We first selected a list of individual microbial products (MPCs 1–5) and combinations (MPCs 6–12) for testing against UM-UC-1 spheroids (Fig. 2F-G and Table 1). Overall, there was an enhancement (4–15 folds) in immune recruitment efficiency for these MPCs compared to control. For instance, MPC5 (E. coli) and MPC8 (S. saprophyticus and E. faecium) exhibited noticeable enhancement effects for NK cell recruitment. MPCs were also tested against spheroids derived from patients with MIBC from stages T2-T4 (Fig. 2H-K). MPCs enhanced immune recruitment of NK cells for these samples generally. Similar to UM-UC-1, MPC5 and MPC8 displayed immunoenhancement activities. Of note, the most effective MPCs appeared to be sample specific. For instance, while MPC5 and MPC8 displayed enhancement in DT2196 (stage T4), the most potent MPC for NK cell recruitment was MPC4 (E. faecium alone). Further analysis revealed that MPCs enhanced not only the recruitment but also the infiltration of NK cells into the spheroids (Supplementary Fig. S5A-B). For instance, MPC5 and MPC8 resulted in NK cell recruitment, surface contact, and infiltration in both UM-UC-1 spheroids and stage T3b MIBC spheroids (DT2153). In contrast, some MPCs, such as MPC4, show only recruitment but not infiltration of NK cells in MIBC spheroids.

MPC immunoenhancement of patient-derived tumor organoids

After demonstrating the approach using spheroids self-assembled from cell lines and primary cancer cells, we evaluated the immunoenhancement capability of AI-optimized MPCs on freshly isolated tumor organoids using the iCARE assay (Fig. 3A-B). A protocol was established for generating tumor organoids from bladder cancer patients for personalized optimization of MPC immunotherapy (Supplementary Fig. S6). These samples include stage Ta, T1, and T2 tumors from patients without a prior history of bladder cancer, those with recurrent disease, as well as BCG-naïve and BCG-refractory tumors (Supplementary Table S1). Organoids were successfully generated from all 11 bladder cancer samples (PPS1-PPS11), including 10 TURBT samples and 1 smaller bladder biopsy sample, for evaluating their immunogenicity. While we were able to culture organoids and expand the cancer cells, our primary goal was to rapidly assess the immunogenicity of the sample and predict the treatment response. Therefore, we directly tested the immunogenicity of freshly isolated organoids in the iCARE assay without subculturing and storage of the samples.

A, B Schematic of the personalized workflow for bladder cancer management and the procedure for preparing patient-derived tumor organoids for the iCARE assay. Panel b was hand-drawn by the authors using Procreate and finalized in PowerPoint; all elements are original. C-M Evaluation of 11 clinical samples (PPS1-11) using the iCARE assay. NK cell recruitment was assessed in response to MPC1-12 for PPS1-6 and an extended panel of MPCs for PPS7-11. PPS4 and PPS9 are recurrent tumors; PPS4 had undergone prior BCG treatment. N Heatmap showing upregulated chemokines in PPS2 relative to PPS1 and PPS3. O Heatmap illustrating chemokine modulation by MPC12, MPC9, and MPC5, with expression levels normalized to the untreated control. Genes with expression levels near the detection limit were excluded from the analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SE. P values were derived by the Welch T test followed by Dunn’s test, ns P > 0.05; * P < 0.05. n = 3, independent biological replicate experiments for PPS1-6; n = 5, independent biological replicate experiments for PPS7-8; n = 4, independent biological replicate experiments for PPS9; and n = 6, independent biological replicate experiments for PPS10-11. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

PPS1–6 were tested against MPC1–12, which were generated during the first round of AI-guided MPC selection. A second round of neural network training was performed to refine our selection strategy by incorporating greater microbial diversity and representation. PPS7–11 were tested against MPCs selected from this second round, including combinations containing up to six microbial products (Fig. 3C–M and Table 1). For reference, MPC1, MPC3, MPC5, MPC8, and MPC9 were tested across all samples. Untreated controls typically exhibited limited NK cell recruitment capabilities and had the lowest number of recruited NK cells compared to organoids treated with MPCs. One notable exception was PPS2, an initially diagnosed case, which exhibited substantial NK recruitment capability. PPS2 also exhibited higher excitability with MPCs compared to PPS1 and PPS3. Additionally, PPS2 displayed strong infiltration of NK cells and a robust ability to recruit CD3+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. S5C-D). Overall, immunoenhancement over the untreated control was achieved with at least some MPCs for most organoid samples. Similar to self-assembled spheroids, the best MPCs for freshly isolated tumor organoids were sample-specific. As an example, MPC4 showed some activity for PPS1-3 but had negligible activity for PPS4-6.

Analysis of immune-tumor interactions for samples PPS7-11 using the refined panel of MPCs further revealed distinct recruitment behaviors (Supplementary Fig. S7). Several MPCs showed immunoenhancement in PPS7 and PPS11, with increased recruitment of NK cells to these organoids. Enhanced NK cell activity was observed, including surface contact with and infiltration into the organoids (Supplementary Fig. S7A,E). We also noted that some samples, such as PPS8 and PPS9, exhibited limited NK cell infiltration despite showing increased NK recruitment compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. S7B,C). In contrast, samples such as PPS2 and PPS10 responded positively to most MPCs, showing significant enhancement in both NK cell contact and infiltration (Supplementary Fig. S5C and S7D). Remarkably, the majority of NK cells infiltrated the organoids, instead of recruited or contacted (i.e., d > 0 or d = 0), in PPS2 and PPS10. In addition to NK cell, we have also demonstrated MPCs for enhancing the recruitment of autologous T cells and heterogenous immune cell population (Supplementary Fig. S8-S11).

Immunoanalysis of patient-dervied organoids

To evaluate the mechanism of MPC-mediated NK cell recruitment and to compare MPC responsiveness among PPS1, PPS2, and PPS3, we performed molecular analyses on these samples. RNA-seq analysis was conducted on the samples to evaluate the molecular subtype and immunogenicity of these tumor samples. Cell enrichment scores based on the transcriptional profiles indicated that PPS2 exhibited the highest level of NK cell-related gene signatures (Supplementary Fig. S12A)32. PPS2 also showed elevated expression of markers for some innate immune cells, such as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and macrophages, compared to PPS1 and PPS3. In addition, PPS2 exhibited higher levels of genes associated with basal cancer cells, including KRT5, KRT14, and TP63 (Supplementary Fig. S12B). The basal-squamous molecular subtype is associated with increased immune infiltration, including cytotoxic lymphocytes and NK cells33. Analyzing the transcriptional gene expression profiles also revealed that PPS2 had elevated expression levels of chemoattractants, such as IL-6, IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-18, IL-25 (IL-17E), CXCL9 (or MIG), and chemokine (C motif) ligand 1 (XCL1 or lymphotactin) (Supplementary Fig. S12C). These chemoattractant genes are associated with T cell and NK cell recruitment and activation34,35.

We further conducted a proteomic analysis of secreted molecules from the tumor sample. In agreement with RNA-seq data, PPS2 exhibited elevated levels of a similar set of chemoattractants (IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, IL-25, CXCL9, and XCL1) relative to PPS1 and PPS3 (Fig. 3N). We also treated the organoids with one or more MPCs, including MPC5, MPC9, and MPC12. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis reveals that the upregulation of immune-related signaling pathways and chemokine-chemokine receptor interactions by MPCs (Supplementary Fig. S13)36. In particular, the application of MPCs led to increased expression of chemoattractants (IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, IL-25, CXCL9, and XCL1) in organoids compared to the untreated control (Fig. 3O). Other cytokines upregulated by MPCs included well-established markers of inflammation and infection (e.g., TNF-α and IFN-γ), as well as monocyte chemotactic protein 3 (MCP-3), macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha (MIP-3a) and midkine34,35. These expressions correlated with the enhancement of immune cell recruitment observed in the iCARE assay. In contrast, MPCs did not exhibit a clear effect on expressions associated with immune checkpoint inhibition, apoptosis, and proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S14). These results suggest that the influence of MPCs may stem from the recruitment and activation of immune cells, facilitated by an increase in cytokines and chemokines.

Pre-clinical validation of the personalized MPC immunotherapy

We evaluated the efficacy of MPC immunotherapy using an orthotopic mouse bladder cancer model (Fig. 4A). In the MB49 murine model, the animals have a fully functional immune system, and this model has been applied for evaluating various immunotherapies27,28. The effectiveness of MPCs in enhancing the recruitment and infiltration of NK cells to MB49 cells was first assessed in iCARE to select potent MPCs (Supplementary Fig. S15A). Two rounds of iCARE assays with MB49 self-assembled spheroids were performed to different sets of AI-optimized MPCs (Supplementary Fig. S15B-C). MB49 spheroids exhibited enhanced recruitment with MPC5 and MPC8 similar to spheroids and patient-derived organoids. We also observed strong immunoenhancement effects by other MPCs, such as MPC12, MPC13, MPC15, and MPC17, compared to control. Confocal images supported that MPCs could enhance the interactions between MB49 spheroids and NK cells (Supplementary Fig. S15D-E and Supplementary Movies 1-2).

A Experimental workflow for selecting potent MPCs in the mouse bladder cancer model. B Experimental schematic: Mice were implanted with MB49 bladder tumors on day 0 and received low frequency intravesical MPC (MPC_LF) or DMEM control on days 2, 9, and 16, or MPC on days 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, and 17. On day 20, mice were euthanized, and tumor single cell suspensions were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. C Representative images of mouse bladders on day 20. D Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis of tumor and immune cell components in DMEM-treated control and MPC17-treated mouse bladders. E Histopathological images of H&E-stained mice bladder tumors comparing Control and MPC17 at 20X magnification. The infiltration score increases from 2.52 ± 0.98 to 3.13 ± 0.78 (p = 0.0498, Student’s T test). Scale bar, 50 μm. Representative images of n = 8 for DMEM, n = 10 for MPC17, mouse biological replicates. Comparison of MPC-treated versus DMEM-treated bladders for: F WBC (CD45+) percent of total live cells, G representative flow cytometry plots of the immune cell population, H T cell (CD45+CD3+) as a percentage of total live cells, I CD4+ T cell (CD45+CD3+CD4+) as a percentage of total live cells, J CD8+ T cell (CD45+CD3+CD8+) as a percentage of total live cells, K B cell (CD45+CD19+) percent of total live cells, L NK cell (CD45+NK1.1+) as a percentage of total live cells, and M dendritic cell (CD45+CD11c+) as a percentage of total live cells. Data represent mean ± SE. P values from flow analysis were derived by the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test, ns P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Mouse biological replicates were used, with n = 8 for DMEM, MPC8, and MPC14; n = 10 for MPC15 and MPC17, all mice from two batches combined (B-M). N Experimental schematic: Mice were implanted with MB49 bladder tumors on day 0 and received intravesical MPC_LF or DMEM control on days 2, 9, 16, 23, and 30, or MPC on days 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, and 29. Survival of mice treated with (O) intravesical MPC and (P) MPC_LF. Statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis with multiple comparisons test. ns P > 0.05; ∙ P < 0.1; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. Mice sample size: n = 15 for all survival studies, with the control group from the same experiment (N-P). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

After in vitro screening, the immunoenhancement effectiveness of selected MPCs was tested in vivo. A pilot study was conducted with 42 MB49 tumor-bearing mice to evaluate different MPCs and treatment frequencies. MB49 cells were implanted in C57BL/6 mice on day 0. Starting on day 2, MPCs or a DMEM control were administered intravesically into the mice’s bladders on a weekly or biweekly schedule (Fig. 4B). Tumor uptake was confirmed on day 7 (Supplementary Fig. S15F). On day 20, the tumor-bearing mice were euthanized, and the bladders were harvested for staining and evaluation by a certified pathologist. H&E staining and inflammation extent score revealed an increase in immune cells and immune infiltration in mice treated with MPCs compared to the control group (Supplementary Fig. S15G-H).

A set of selected MPCs, including MPC8, MPC14, MPC15, and MPC17, was chosen for further investigation based on in vitro screening and the pilot study (Supplementary Fig. S16A). Flow cytometry analysis of the tumor was performed to evaluate the influence of MPCs on the immunity quantitatively (Fig. 4C-D and Supplementary Table S2). The results revealed a significant increase in total lymphocytes (CD45+) in MPC-treated mice (Fig. 4F-G). The increase in immune cell infiltration was also confirmed by pathological analysis with H&E staining (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. S16B). Substantial differences were observed in T cells (CD45+CD3+), B cells (CD45+CD19+), NK cells (NK1.1+), and dendritic cells (CD45+CD11c+), with no notable difference in macrophages (CD11c+F4/80+) (Fig. 4H-M and Supplementary Fig. S16C-E). Notably, MPC-treated mice showed an increased proportion of CD4+ T cells (CD45+CD3+CD4+), while the proportion of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CD45+CD3+CD8+) did not have a significant difference (Fig. 4I-J). Among the MPCs, MPC8 and MPC14, both containing microbial products from S. saprophyticus and E. faecium, appeared to have a stronger effect on B cell and dendritic cell. MPC15 and MPC17, composed of a combination of B. longum, S. saprophyticus, E. faecium, and E. faecalis, strongly upregulated T cells and NK cells. We also noted a slight reduction of bladder weight on day 20 for MPC15 and MPC17 treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S16F). Analysis of the immune cell subpopulations confirmed these observations (Supplementary Fig. S17). These results supported the notion that MPCs can enhance the recruitment and infiltration of immune cells into the tumor microenvironment.

Impact of MPC immunotherapy on pre-clinical oncologic outcomes

A survival study was then conducted to evaluate the effect of MPCs on the orthotopic bladder cancer model. Treatment involved weekly intravesical administration of MPC_LF/DMEM or bi-weekly delivery of MPC for 30 days, and the survival of the mice was observed for up to 80 days (Fig. 4N). We observed an overall increase in survival with MPC treatment (Fig. 4O-P). The median survival time of control mice was 22 days, with most mice dying after 32 days, similar to other studies of MB49 implantation27,28. With MPCs, the median survival time increased significantly for all MPCs. MPC15 and MPC17 showed median survival times of 42 and 48 days, respectively, while the values for MPC8 and MPC14 were 30 and 35 days. MPCs also led to a 4–6 folds increase in the overall survival rate. At the conclusion of the 80-day observation period, 40% in the MPC17-treated and approximately 25% of the MPC8, MPC14, and MPC15 treated animals were alive compared to only 6% in the control mice. While both high and low frequencies of MPC administration resulted in substantial improvement in survival compared to control mice, treatment efficacy was higher with biweekly MPC administration. For instance, MPC17_LF with weekly injections resulted in a 30% survival rate, whereas MPC17 with bi-weekly injections achieved a 40% long-term survival rate. The medium survival time, however, was similar between weekly and bi-weekly injection. A pairwise log-rank test comparing the medium survival time of each treatment group to the control group revealed significant differences, underscoring the efficacy of MPC treatments compared to control (Supplementary Fig. S18). Furthermore, MPCs, such as MPC17, showed enhanced survival compared to MPC0 (i.e., microbial product derived from BCG) at the same frequency. These results support the notion that MPC immunotherapy can significantly increase survival in the orthotopic bladder cancer model.

Comparison of MPC with BCG immunotherapy

We investigated the efficacy of MPC immunotherapy in comparison with BCG, which is the current gold standard in the treatment of high-risk NMIBC8,9. Bladder tumors in mice treated with MPC were analyzed against those receiving BCG or PBS control. The mice underwent biweekly intravesical treatments with MPC17. On day 20, the bladders were harvested and weighed (Supplementary Fig. S19A). While bladder weight was slightly reduced in the MPC group, the reduction was not statistically significant. Flow cytometry revealed a significant increase in the total abundance of lymphocytes (CD45+) of the MPC group compared to control and BCG (Fig. 5A-B). MPC treatment resulted in a high abundance of T cells (CD45+CD3+) and NK cells (CD45+NK1.1+) and a relatively low abundance of B cells (CD45+CD19+) compared to BCG (Fig. 5C-E and Supplementary Fig. S19B-C). Among T cells, MPC17 enhanced both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets compared to BCG (Fig. 5F-G). On the other hand, no significant differences were detected between MPC17 and BCG in innate immune cell populations, including neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+), dendritic cells (CD45+CD11c+) and macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) (Fig. 5H-J,L and Supplementary Fig. S19D-F). A similar observation was made for the overall population of immune cells (Supplementary Fig. S20).

Comparison of MPC-treated versus BCG-treated bladders for: A CD45+ percent of total live cells, B representative flow cytometry plots of the immune cell (WBC, CD45+) population, C NK cell (CD45+NK1.1+) percent of total live cells, D B cell (CD45+CD19+) percent of total live cells, E T cell (CD45+CD3+) percent of total live cells, F CD4+ T cell (CD45+CD3+CD4+) percent of total live cells, G CD8+ T cell (CD45+CD3+CD8+) percent of total live cells, H Neutrophil (CD11b+ Ly6G+) percent of total live cells, I Dendritic cell (CD45+CD11c+) percent of total live cells, and J macrophage (CD11b+F4/80+) percent of total live cells. K Experimental schedule for mice with delayed treatment. Mice were inoculated with MB49 bladder tumors on day 0 and subsequently received three weekly intravesical treatments with MPC_LF, BCG, or PBS control, or six bi-weekly treatments with MPC starting on day 3. L UMAP of PBS-treated (Control), BCG, and MPC17-treated mice bladders for tumor cell and immune cell components. Data represent mean ± SE. P values from flow analysis were derived by the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test, ns P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Mouse biological replicates n = 6 for PBS, n = 9 for BCG, n = 10 for MPC17 (A-J, L). M Survival rates of mice treated intravesically with MPC and BCG with treatment on day 2 (see Fig. 4N). N Survival rates of mice treated with intravesical BCG or MPC with treatment on day 3 (see Fig. 5K). P values from the Kruskal-Wallis with multiple comparisons test. ns P > 0.05; ∙ P < 0.1; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. n = 15, mice replicates (K, M, N). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We directly compared MPC to BCG intravesical therapy (Fig. 5K). In the MB49 murine model BCG or MPC treatment was initiated 2 or 3 days after tumor cell implantation. Delaying treatment to day 3, rather than day 2, reduced therapeutic efficacy and has previously been used to mimic aspects of BCG non-responsiveness28. While this approach does not fully replicate clinical BCG failure, it captures certain features of reduced BCG responsiveness. For treatment on day 2, BCG showed a median survival time of approximately 20 days, which was similar to control (Fig. 5M). The median survival time of the biweekly MPC17 treatment was 32 days. MPCs also resulted in a two-fold improvement in the long-term survival rate, with 26.7% for the MPC17-treated group compared to 13.3% survival rate for BCG-treated group and 0% for the PBS control group. For treatment on day 3, BCG resulted in the same median survival time as the control and did not show statistical significance. In contrast, both MPC15 and MPC17 increased the survival of the mice significantly (Fig. 5N).

Intracellular staining of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and perforin (PRF) was performed to evaluate the activity of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 6A-D and Supplementary Fig. S21). BCG treatment increased the proportion of CD4+ T cells with upregulated IFN-γ and TNF-α, consistent with the role of IFN-γ signaling in BCG-induced tumor immunity27. In contrast, MPC17 treatment significantly increased the proportion of IFN-γ and TNF-α-expressing NK cells. Additionally, MPC17 enhanced IFN-γ and TNF-α mRNA expression in dissociated cancer cells, as measured by a nanobiosensor (Fig. 6E-G)37,38. Furthermore, perforin expression, a critical component of immune cytotoxicity, was assessed. While the overall proportion of perforin-expressing cells was similar across the control, BCG, and MPC17 groups, MPC17 significantly enhanced perforin expression levels in NK cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells, followed by BCG and the control group (Supplementary Fig. S22). Collectively, these data suggest that MPC immunotherapy enhanced immune activity and survival of mice compared to the gold standard BCG treatment, highlighting the potential of using MPCs for cancer treatment.

Cell populations expressing functional intracellular cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, and perforin (PRF) are reported as the percentage of A myeloid cells (CD45⁺CD11b⁺), B NK cells (CD45⁺NK1.1⁺), C CD4⁺ T cells (CD45⁺CD3⁺CD4⁺), and D CD8⁺ T cells (CD45⁺CD3⁺CD8⁺). Error bars represent the mean ± SE. P values were derived using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. CI 95%. ns P > 0.05; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. Mouse biological replicates n = 6 for PBS, n = 9 for BCG, and n = 10 for MPC17 (A-D). E Schematic of the GNR-LNA biosensor for single cell gene expression analysis. F Relative expression levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α. G Representative confocal images of IFN-γ and TNF-α expression. Scale bar, 10 μm. P values were derived using either one-sided Welch T test or Kruskal-Wallis Test. Outliers ( > 1.5×IQR) excluded for statistics. ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Statistics were calculated with mouse biological replicates n = 5 for Control, BCG, and MPC17 (E-G). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the potential of MPC immunotherapy as a therapeutic option for bladder cancer. We show that MPCs effectively enhance immune recruitment and infiltration in bladder cancer cell lines, primary cancer cells derived from MIBC patients (stage T2 to T4), and freshly isolated tumor organoids from bladder cancer stages Ta, T1, T2, and T3. Increased immune recruitment, driven by at least some MPCs, was observed in most samples, including those with low immunogenicity and recurrent tumors previously treated with resection and BCG. In the orthotopic bladder cancer model, both the median survival time and overall survival rate were significantly improved by MPCs compared to BCG. Since TURBT is used for both diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer, generating freshly isolated patient-derived organoids from TURBT samples could complement clinical pathology by predicting treatment responsiveness and guiding therapeutic options. Given the high rate of BCG failure, the ongoing BCG supply shortage, and the lack of effective alternatives for bladder cancer patients, our platform may offer a personalized strategy for the management of bladder cancer.

The MPC platform offers several advantages compared to other immune modulation techniques. First, MPCs eliminate the uncertainty associated with the proliferation and mobility of live bacteria22. Second, the broad selection of microbes, including pathogenic strains, presents relatively unexplored opportunities for modulating immune activity. As shown in our data, MPC5, derived from a clinical isolate of uropathogenic E. coli, demonstrates a strong immunoenhancing effect on its own. Third, many MPCs exhibited stronger immunoenhancement compared to individual microbial products. The ability to mix and match microbial products allows for the creation of potent MPCs tailored to specific samples, as the most effective MPCs tend to be sample-specific. The iCARE assay has demonstrated a strong ability to predict the immunoenhancement effect of MPCs, as shown in the MB49 model. A similar trend in the efficacy of MPC8, MPC14, MPC15, and MPC17 for immune cell recruitment (NK cells and total white blood cells) was observed both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 7A-B). In particular, MPC14, MPC15, and MPC17 showed stronger effects compared to MPC8 and the control. Remarkably, this trend in immune recruitment also correlated with the median survival time in mice (Fig. 7C), supporting the use of the iCARE assay and MPCs in personalized immunotherapy.

A In vitro NK cell recruitment strongly correlates with in vivo tumor-infiltrating NK cell levels (r = 0.93, P = 0.024). B A positive correlation is also observed between in vitro NK cell recruitment and the infiltration of total white blood cells (WBC) in tumors (r = 0.83, P = 0.0839). C In vitro NK cell recruitment correlates with median survival in MB49 tumor-bearing mice, with a strong trend observed under low-frequency MPC dosing (r = 0.85, P = 0.068) and a moderate trend under high-frequency dosing (r = 0.55, P = 0.34). These findings support the predictive value of the NK recruitment assay for in vivo immune activation and therapeutic outcomes. Correlation analysis was performed using independent biological samples, n = 5. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

While the precise mechanism of MPC immunotherapy remains unclear, our data suggest the MPCs enhance immune recruitment by upregulating chemokine expression. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses indicate that MPCs can activate cancer cells and stimulate the release of chemokines that recruit immune cells. Specifically, MPCs increased the secretion of IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, all of which are crucial for BCG responsiveness10,11. For instance, our data suggest IL-8 is contributing to the recruitment of NK cells in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S23). Flow cytometry and nanobiosensor data further support the activation of immune cells. Importantly, MPCs displayed strong recruitment activity for NK cells, as well as T cells, which are also critical for the success of BCG immunotherapy10,11. CD4-dependent tumor-specific immunity, in particular, has been shown to mediate anti-tumor cytotoxicity in bladder cancer27,39. Despite some similarities, our data suggest that MPCs function through mechanisms distinct from those of BCG. Specifically, MPC17 and BCG promoted the recruitment and activation of different immune cell populations. In survival analysis, BCG demonstrated limited effectiveness, with its survival curve largely overlapping that of the control group and showing similar median survival times. In contrast, treatment with MPCs resulted in significantly longer median survival. Overall, the mechanisms by which non-specific microbial products trigger the adaptive T cell response and how this immunity improves survival remain unclear. These questions, tied to the intricate and nuanced interactions between the immune system, microbes, and tumors, persist despite microbial-based cancer treatments having been reported for over a century4,5,6, and the routine use of BCG for decades10,11. Future mechanistic investigation will be required to elucidate the mechanisms of MPC immunotherapy.

To fully realize the clinical potential of MPC-based cancer treatment, future efforts should focus on optimizing key aspects of the MPC protocol, including dosage, administration frequency, and production reproducibility. In this study, potent MPCs were selected from a prescreened library to minimize time, cost, and workflow complexity, which are important considerations for clinical translation. Alternatively, the AI-guided optimization workflow, in combination with the iCARE assay, offers a means to tailor MPCs to individual patients. This personalized approach may be particularly valuable for treating advanced-stage tumors that are resistant to standard therapies. Furthermore, MPCs were selected based on their ability to recruit NK cells (NK-92MI). Expanding the selection criteria to include other innate immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, could further enhance the immunostimulatory capacity of MPCs. Additionally, the optimized MPCs were initially chosen based on responses observed in the UM-UC-1 cell line. While most clinical samples showed increased NK cell recruitment, a subset demonstrated limited responses. It remains uncertain whether such recruitment is sufficient to trigger a robust therapeutic immune response. To address this limitation, future studies should incorporate patient-derived samples representing the major molecular subtypes of bladder cancer, along with autologous immune cells, to enhance clinical relevance and precision. Broader exploration of microbial products may improve the efficacy and applicability of MPCs, and further studies are warranted to identify the active immunostimulatory components within MPC formulations (Supplementary Fig. S24). Additionally, combining MPC immunotherapy with other modalities, such as immune checkpoint blockade, may synergistically improve treatment outcomes. Notably, higher-frequency MPC administration appeared to yield improved survival, even though weekly dosing already extended median survival. This observation may reflect factors such as low microbial product retention, insufficient colonization and proliferation, or weaker immunological interactions compared to live bacterial therapies. Further investigation is needed to optimize dosage, frequency, and delivery strategies to fully maximize the therapeutic benefits of MPC immunotherapy.

In summary, this study demonstrates that MPCs can enhance immune recruitment, infiltration, and activation, laying the groundwork for an alternative class of immunotherapies. MPCs hold promise as complementary agents to existing treatments and may contribute to the development of personalized, immune-based strategies for cancer care. Further research is warranted to fully evaluate their therapeutic potential and elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action.

Methods

Device design and fabrication

The multiplex microfluidic device for the iCARE assay was designed with an upper chamber for immune cells and a lower compartment for tumor organoids, separated by an ECM-coated membrane. Device geometries were created using CAD software and fabricated on 2 mm thick acrylic boards via CO2 laser machining. The lower chamber included configurations of 144, 64, 16, or 4 wells, each 0.085 inches in diameter and spaced 0.04 inches apart, suitable for imaging with a 10X objective on a confocal microscope. Following fabrication, the wells were sterilized and plasma-treated. The upper chamber of the multi-well configuration incorporated a 0.6 ×0.6-inch well fitted with a 5 μm pore-sized polycarbonate membrane (Sterlitech).

For organoid culture based on established protocols, 3 μL of 8 mg/mL growth factor-reduced Matrigel into the lower chamber wells and allowing it to solidify for 15 min before cell seeding40. Consistent spheroid size and number per well were ensured by seeding a fixed number of cancer cells (3,500 cells per well) in Matrigel, followed by overnight incubation for uniform spheroid formation. Microscopic assessments were conducted prior to each assay to verify spheroid consistency. Cancer cells were stained with CellTracker Deep Red (Invitrogen), suspended in 7 μL of serum-free medium, and seeded uniformly on top of the solidified Matrigel. After an overnight incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2, microbial products were loaded into the device wells. Type I bovine collagen solution (PureCol) diluted to 2.5 mg/mL in culture media, and pH adjusted to 7 with 0.1 M NaOH was then added to the upper chamber of the device and placed in a humidified cell incubator for 1 hour to solidify. Then, 7 μL of microbial products or DMEM was administered to the cancer cells in the lower chamber. CellTracker Green (Invitrogen)-labeled NK cells (105 cells) were suspended in 100 μL of serum-free media and seeded onto the collagen gel surface. The device assembly was completed using biocompatible double-sided tape and application of pressure, followed by a 24-hour incubation period. Imaging was conducted using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope equipped with an incubation chamber set at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere. Image reconstruction was performed, and the number of migrated NK cells, labeled with fluorescence, were quantified utilizing ImageJ (Fiji) and Imaris (Bitplane Inc., version 9.8). NK cell recruitment was quantified by counting fluorescently labeled NK cells that migrated into the lower chamber of the iCARE device and accumulated around the tumor spheroids.

Cell culture and reagents

Bladder cancer cell lines UM-UC-1, RT4, and 5637 from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human bladder cancer cells (stage T2, lot numbers: DT02101 and DT02334; stage T3b, lot number: DT02153; stage T4, lot number: DT02296) purchased from BioIVT (Westbury, NY) were cultured in DMEM (Fisher Scientific, NH) supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Upon reaching approximately 70% confluence, cells were washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and detached using trypsin-EDTA solution. Trypsinization was quenched with complete culture media. Cells were then seeded at a 1:3 or 1:4 dilution into fresh T-75 flasks for subculturing. Cell counts and viability were checked using a hemocytometer. NK-92MI cells, acquired from ATCC, were maintained in Alpha Minimum Essential Medium with 0.2 mM inositol, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.02 mM folic acid, 12.5% horse serum, and 12.5% FBS. CD3+ T cells, acquired from Astarte Biologics, were cultured in RPMI supplemented with IL-2. All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and maintained at a concentration of 2-3×105 viable cells/mL.

Bacteria culture

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (EC137) and Staphylococcus aureus (SA), isolated from patients with urinary tract infections, were cultured in Mueller Hinton broth (M-H Broth) at 37 °C in an orbital shaker. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA, ATCC 10145) from ATCC was also cultured in M-H Broth. Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP, ATCC 13883) was cultured in Luria Broth (LB). Enterococcus faecium (Efm, ATCC 35667) and Enterococcus faecalis (Efs, ATCC 49532) were cultured in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI). Staphylococcus epidermidis (SE, ATCC 12228) and Staphylococcus saprophyticus (SS), isolated from a urinary tract infection patient, were cultured in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB). Probiotic strains Lactobacillus plantarum 15697 (Lpa, ATCC NCIMB 8826), Lactobacillus plantarum 14917 (LPb, ATCC 14917), and Bifidobacterium longum (BL, ATCC 15697) as well as Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA, ATCC 4356), kindly provided by Prof. Darrell Cockburn at the Pennsylvania State University, were maintained in MRS (de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe) medium under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. Bacterial growth was monitored using optical density (OD) measurements at a wavelength of 600 nm. All strains were incubated overnight at 37 °C and allowed to grow until reaching mid-log phase, with OD values of 0.2-0.4 for pathogens and 0.6-0.8 for probiotics at 600 nm (Nanodrop 2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Microbial product preparation

Microbial products were generated from probiotics, ATCC strains, and uropathogenic bacteria. Bacteria were individually cultured to the mid-log phase, and cell pellets were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 1000 × g, followed by one wash with 1X PBS. A total of 108 cells/mL were resuspended in serum-free DMEM tissue culture media. The bacterial suspension was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was discarded, and microbial products were collected by passing the conditioned media through a 0.22 µm Nylon syringe filter (Fisher Scientific). Frozen aliquots of microbial products were stored at −80 °C and used within one month. Microbial products were mixed to the desired composition immediately before use.

Mouse cell culture

The luciferase-expressing mouse bladder cancer cell line MB49, maintained under G418 selection, was a gift from Prof. Michael S. Glickman from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. MB49 cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 800 μg/mL G418 (Sigma) to maintain luciferase expression. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. All cell lines were routinely tested and confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma using the IMPACT II PCR Profile (IDEXX BioAnalytics).

MB49 orthotopic implantation

C57BL/6 mice (stock #000664) were procured from The Jackson Laboratory and housed in the PSU Research Animal Resource Center under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were conducted with the approval of PSU’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under Protocol 202202340, in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Female mice (6–8 weeks old, The Jackson Laboratory) were anesthetized using an isoflurane chamber. A catheter, constructed by affixing PE10 tubing to a 30 G needle with 1 mm exposed, was inserted into the bladder via the urethra. Through this catheter, 100 μL of poly-l-lysine (Sigma) was administered, followed by capping with an injection plug (Terumo). The mice remained anesthetized for 30 min. After this period, the catheter was removed and reinserted following bladder evacuation. Approximately 100 μL of an MB49 cell suspension (500,000 cells/mL in RPMI, ~50,000 cells per mouse) was then injected, and the catheter was recapped for an additional hour under anesthesia. After catheter removal, the mice were allowed to recover.

One week after MB49 implantation, the mice received injections of D-luciferin potassium salt (GoldBio) and were imaged using an IVIS Spectrum in vivo imaging system to confirm tumor cell uptake. The mice were monitored daily for signs of distress, including dull fur, apathy, or visible tumor growth, and were euthanized if their symptoms indicated significant distress.

Survival analysis

Mice were monitored daily for health status and survival. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated, with the study endpoint defined as either the maximum observation period or when humane endpoints were met. Humane endpoints were applied throughout, including >20% loss of initial body weight, severe lethargy, impaired mobility, lack of grooming, labored breathing, or inability to access food or water. Mice meeting these criteria were humanely euthanized, and the date of euthanasia was recorded for survival analysis.

BCG culture and BCG microbial product

The Pasteur strain of BCG (ATCC, ATCC 35734) was cultivated at 37 °C in Middlebrook 7H9 medium, supplemented with 10% albumin/dextrose/saline and 0.05% Tween 80. To create standardized stocks for infection, BCG was cultured to mid-log phase (OD600 0.4–0.6), washed twice in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80, and resuspended in PBS with 25% glycerol. These stock suspensions were stored at −80 °C. To determine the final bacterial titer, a sample was thawed, serially diluted, and plated on 7H10 agar. The bacterial titer was calculated by counting colonies after 2 weeks of incubation. The BCG microbial product (MPC0) was prepared and stored using the same protocol as other microbial products.

Intravesical MPCs and BCG treatment

Thawed stocks of microbial products were mixed in specified ratios to form MPCs. Frozen BCG stocks, prepared as previously described, were thawed and resuspended in PBS to a final concentration of 3 × 107 CFU/mL. Serum-free DMEM was used as the control. For intravesical administration, anesthetized mice in an isoflurane chamber received a catheter inserted through the urethra into the bladder, followed by the injection of 100 μL of either MPC, BCG (∼3 × 106 CFU per mouse), or DMEM. The catheter was then secured with an injection plug (Terumo), and the mice were kept under anesthesia for 2 h. After treatment, the catheters were removed, and the mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia.

Preparation of bladder single cell suspensions

Tumor-bearing mice were euthanized, and the bladders were harvested, kept in ice-cold RPMI, and immediately transferred to the lab. The bladders were minced and incubated in a solution containing 1 mg/mL collagenase type I (Invitrogen) and 2 KU/mL DNase I, type IV (Sigma) in serum-free RPMI at 37 °C for 1 hour on an orbital shaker. The resulting suspensions were passed through a 70-μm filter (Invitrogen), and red blood cells were lysed using RBC Lysis Buffer (Invitrogen).

Flow cytometry

Cell suspensions were analyzed using a flow cytometer (Cytek Aurora), and data analysis was performed with Kaluza and FlowJo software (Tree Star). MB49 bladder tumors grow diffusely across the entire bladder epithelium, making it challenging to distinguish between healthy and tumor tissues. Bladder weights alone are not reliable indicators of tumor size. Therefore, our analysis also includes the percentages of live cells in each bladder sample, as well as their proportions within the total CD45⁺ cell population. Cells were initially stained with antibodies against extracellular antigens, followed by fixation and permeabilization using the Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and subsequently stained for intracellular antigens. Details of the antibodies used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Human patient sample collection and preparation

Tumor tissues were obtained from patients undergoing TURBT at the Palo Alto VA hospital, with approval by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (protocol #55427) and patient consent. After collection, the samples were immediately placed on ice in DMEM supplemented with 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 100 μg/mL Primocin (InvivoGen). The samples were then transported to the laboratory via overnight shipment. The tissues were washed in organoid culture media containing hepatocyte media with 10 ng/mL EGF, 5% CS-FBS, 10 μM Y-27632 (STEMCELL Technologies), 1X GlutaMAX (Gibco), and 100 μg/mL Primocin. The tissues were minced with #10 blades and incubated in 10 mL of a 1:10 dilution of collagenase/hyaluronidase solution (STEMCELL Technologies) at 37 °C for 50 min, with tissue monitored every 20 min under a light microscope. The dissociated tissues were centrifuged at 350 × g for 5 min, resuspended in PBS, and centrifuged again. They were then resuspended in 5 mL of TrypLE Express and incubated at room temperature for 3 min, followed by the addition of 10 mL modified Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 5% CS-FBS, 10 μM Y-27632, and 100 μg/mL Primocin. After centrifugation at 350 × g for 5 min, the tissues were resuspended in 10 mL HBSS supplemented with 5% CS-FBS, 10 μM Y-27632, and 100 μg/mL Primocin. The tissues were passed through 40 μm and 100 μm strainers and used directly in the assay. Cell clusters between 40 μm and 100 μm were resuspended in 60% Matrigel (Corning) in organoid culture media and plated as a 250 μL drop in the center of a pre-coated 6-well plate with 60% Matrigel. After a 30-minute incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO₂ to solidify the drop, 1.5 mL of organoid culture media was added on top, with the medium changed every 3–4 days. For long-term storage, cells and organoids were frozen in a medium containing 90% CS-FBS and 10% DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Chemokine secretion profile

Antibody-based Human Chemokine Proteomic Array kit (R&D systems) was used to test the expression of chemokines in bladder cancer samples following the manufacturer’s protocol. The supernatants of bladder cancer cells were collected from the 72 h culture at 104 cells/mL in 8 mg/mL growth factor-reduced Matrigel (Corning) coated 96-well plate. The chemiluminescent analysis was performed using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System, and the semi-quantitative results were processed using the open-source software ImageJ (NIH).

Cytokine expression profiles were analyzed using the Human Cytokine Array Q1200 (RayBiotech), capable of quantitatively detecting 1200 biomarkers. A total of 10 samples, including unstimulated (PPS1-3) and MPC-stimulated PPS1-3 supernatants, were collected after 72 h of incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and assayed following the manufacturer’s protocol. Data analysis, including normalization and statistical testing, was performed using the RayBiotech software, with significant cytokine modulations identified by paired t-tests (p < 0.05).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Microbial product samples were thawed on ice and 50 µL of each sample were transferred to a new processing tube, to which was added 200 µL of LC-MS grade 80% methanol, 20% water with 1 µM chlorpropamide. The tubes were then briefly vortexed and incubated on ice for 20 min. Once the incubation was finished, samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 18,213 rcf at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and dried under nitrogen gas in a 35 °C heat block. After drying, the samples were reconstituted in 100 µL of LC-MS grade 3% methanol, 97% water with 1 µM chlorpropamide. Samples were briefly vortexed, sonicated for 5 min, and then transferred to 2 mL autosampler vials with inserts for subsequent analysis. A processing blank was prepared simultaneously, and a pooled QC was generated. Samples were separated using a Thermo Vanquish Horizon liquid chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a Waters (Milford, MA, USA) BEH C18 (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) column maintained at 55 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% aqueous formic acid (A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (B). The initial solvent conditions were 10% B, held at 10% for 2 min then increased to 40% B at 12 min, 100% B at 15 min, and held at 100% B until 21 min before returning to the initial conditions at 22 min and re-equilibrated until 30 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. The eluate was delivered into a Thermo Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer using heated electrospray ionization. The capillary voltage was set at 2500 V in negative ion mode and 3500 V in positive ion mode. The mass spectrometer collected full scan data at a resolution of 120,000 from 100 to 1000 mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) followed by ddMS2 scans at a resolution of 15,000 using normalized collision energies of 15, 30, and 45%. The sheath gas was set to 40, aux gas was set to 6, and the sweep gas was set to 0. The ion transfer tube temperature was set to 325 °C and the vaporizer temperature was set to 350 °C. Raw LC-MS data files were processed and annotated using MSDial version 4.9.221218.

RNA sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed on cells dissociated from PPS1-3. The RNA samples were sequenced using the DNBSEQ platform (DNBSEQ Technology). Quality control was conducted using SOAPnuke software (BGI), which filtered out raw data containing adapter sequences or low-quality reads. High-quality reads were aligned to the human genome reference (hg38) using STAR. The resulting alignment files were used for downstream gene expression analysis. Gene read counts were calculated with featureCounts in Galaxy, and these counts served as input for Limma-Voom, which was used to identify significantly differentially expressed genes across the human samples. Sequencing data for bladder cancer cell lines UM-UC-1, 5637, and RT4 were obtained from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia.

Deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq profiles

xCell was used to estimate the presence of different immune cells in the sample and to calculate a cell type enrichment score32. The bladder cancer cell line RNA-seq data and the human patient bladder tumor sample RNA-seq data were analyzed separately. A heatmap was created using R. Immune scores were median-centered before creating the heatmaps. Hierarchical clustering was based on Pearson correlation.

GNR-LNA probe design and preparation

To detect IFN-γ, TNF-α, and perforin mRNA expression at the single cell level within the sample, gold nanorod-lock nucleic acid (GNR-LNA) biosensors were designed37,38. Probes (Integrated DNA Technologies) at a concentration of 15 nM were diluted in 1X Tris-EDTA buffer and incubated with MUTAB-coated GNRs (Nanopartz) measuring 10 nm in diameter and 20 nm in length at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, cells were subjected to an overnight incubation with the GNR-LNA probe complex to allow sufficient time for cellular uptake. Probe designs are detailed in Supplementary Table S3.

Statistics and reproducibility

Comparative analysis of the mean values across various treatment groups was conducted using ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. Survival time comparisons among groups were performed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. No formal sample size calculation was performed; sample sizes were determined by the availability of patient-derived tumor specimens and guided by prior studies. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.4.3. In the graphical representations, non-significant differences are marked as ns (p > 0.05), while significance levels are denoted by • (p < 0.1), * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), and **** (p < 0.0001) respectively.

Artificial neural network model

The feedforward artificial neural network model consists of a single hidden layer with 12 nodes, separated by a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function and a dropout layer with a dropout rate of 0.5 to prevent overfitting (Supplementary Software 1). The neural network model input vector (X) represents the composition and dosage of each microbial product within tested MPC combinations. Specifically, each of the 12 bacterial products corresponds to one input feature, defined by its normalized dosage (from 0 to 1) within the cocktail. The neural network model’s predicted output (Y) is the number of NK cells recruited, as quantified by the iCARE in vitro recruitment assay. The dataset included 416 experimental data points, capturing NK cell recruitment activity from single and multi-component microbial product combinations tested using the iCARE assay. The data were randomly divided into training (85%) and testing (15%) subsets for model development and validation. The dataset distribution was visualized to better understand its characteristics (Supplementary Fig. S4E). Two rounds of model training were conducted using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.25, beta values of (0.9, 0.98), and an epsilon of 1e-9 (Supplementary Fig. S4F). The first model was trained for 4000 epochs and achieved a mean squared error (MSE) of 136.72 on the test set. To reduce potential overfitting and improve generalization, the second model was trained for 600 epochs and achieved a lower test MSE of 55.1.

The model was designed with an input vector of size 12, where each element represents the dosage of a specific microbial product. Potent MPCs were selected within discrete search spaces. For example, input configurations were derived from experimental data containing single, dual, or triple microbial products. The values 1.0, 0.5, and 0.33 denote the relative proportions of microbial products in each MPC formulation: 1.0 represents a single microbial product; 0.5 indicates two microbial products combined equally; and 0.33 corresponds to three microbial products mixed in equal parts. However, these configurations reflect only a limited subset of possible combinations. To improve the model’s flexibility and predictive capacity, the search space was expanded to include dosage variations in 0.1 increments (e.g., 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, etc.) across a range from 0 to 1. In this setup, the discrete 0.1 increments define a broader search space that supports combinations of up to 10 microbial products. This approach enabled the exploration of a wider array of potential MPC formulations, increasing the likelihood of identifying the most effective combinations. The model’s output quantified the predicted effectiveness of each tested formulation, allowing for direct comparison.

MPC selection

MPCs were selected from a pool of 100,000 hypothetical combinations computationally evaluated by the neural network model. These effectiveness scores were ranked from highest to lowest to identify top-performing MPC combinations. However, model predictions were only used to guide selection rather than strictly dictate it. No fixed rule or formal algorithm governed selection. MPC selection was prioritized based on coverage (number of microbial products included) and diversity (representation of different microbes) to ensure broad exploration during experimental validation. For example, MPC1–MPC5 were microbial products derived from individual microbes (BL, LA, SS, EFm, and EC). MPC6–MPC10 and MPC12–MPC13 were two-microbe MPCs formed from combinations including BL, EC, LPa, LA, SS, EFm, EFs, and SE. MPC14–MPC21 were derived from combinations of three or more microbes from BL, SS, EFm, SE, and EFs, while the remaining MPCs (MPC11 and MPC22–MPC31) explored other microbial combinations.

Overall, most MPCs tested in this study were among the highest-ranked candidates from the machine learning models, our best options at the time (Supplementary Figs. S25-26). Some MPCs (e.g., MPC12) were hand-selected based on experimental observations and because their constituent strains are widely used probiotics. For PPS1–PPS6, we tested MPC1–MPC12. For PPS7–PPS11, we evaluated a larger set of top-ranked candidates from the second model; these were either within the model’s top 150 or closely related variants of high-ranking MPCs. Within the 16-well iCARE format, we consistently included MPC1, MPC3, MPC5, MPC8, MPC9, and MPC12 as internal references and used the remaining wells to explore additional top predictions.

Ehtics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with all relevant ethical regulations. Human tumor tissue studies were approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (protocol #55427). All animal experiments were approved by the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #202202340).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RNA sequencing data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject ID PRJNA1222391 and BioSample IDs SAMN46780379, SAMN46780380, and SAMN46780381. The raw proteomic data generated using the Proteome Profiling Array have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE298841. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used to produce the results are available in the Supplementary Software 1 file.

References

El Tekle, G. & Garrett, W. S. Bacteria in cancer initiation, promotion and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 23, 600–618 (2023).

Baruch, E. N. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 371, 602 (2021).

Davar, D. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 371, 595–602 (2021).

Busch, W. Aus der Sitzung der medicinischen Section vom 13 November 1867. Berl. Klin. Wochenschr. 5, 137 (1868).

Fehleisen, F. Ueber die Züchtung der Erysipelkokken auf künstlichem Nährboden und ihre Übertragbarkeit auf den Menschen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 8, 553–554 (1882).

Coley, W. B. Late results of the treatment of inoperable sarcoma by the mixed toxins of erysipelas and Bacillus prodigiosus. Am. J. Med Sci. 131, 375–430 (1906).

Oelschlaeger, T. A. Bacteria as tumor therapeutics? Bioengineered bugs 1, 146–147 (2010).

Lobo, N. et al. 100 years of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy: from cattle to COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Urol. 18, 611–622 (2021).

Redelman-Sidi, G., Glickman, M. S. & Bochner, B. H. The mechanism of action of BCG therapy for bladder cancer—a current perspective. Nat. Rev. Urol. 11, 153–162 (2014).

Pettenati, C. & Ingersoll, M. A. Mechanisms of BCG immunotherapy and its outlook for bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 15, 615–625 (2018).

Jiang, S. & Redelman-Sidi, G. BCG in Bladder Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133073 (2022).

Lamm, D. L. et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J. Urol. 163, 1124–1129 (2000).

Witjes, J. A. Management of BCG failures in superficial bladder cancer: a review. Eur. Urol. 49, 790–797 (2006).

Kamat, A. M. et al. BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: recommendations from the IBCG. Nat. Rev. Urol. 14, 244–255 (2017).

Packiam, V. T., Richards, J., Schmautz, M., Heidenreich, A. & Boorjian, S. A. The current landscape of salvage therapies for patients with bacillus Calmette-Guerin unresponsive nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Curr. Opin. Urol. 31, 178–187 (2021).

Lebacle, C., Loriot, Y. & Irani, J. BCG-unresponsive high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: what does the practicing urologist need to know? World J. Urol. 39, 4037–4046 (2021).

Tse, J., Singla, N., Ghandour, R., Lotan, Y. & Margulis, V. Current advances in BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs, 1-14 (2019).

Pan, H., Zheng, M., Ma, A., Liu, L. & Cai, L. Cell/Bacteria-Based Bioactive Materials for Cancer Immune Modulation and Precision Therapy. Adv. Mater. 33, e2100241 (2021).

Li, D. & Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 291 (2021).

Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 135 (2022).

Lehar, J. et al. Synergistic drug combinations tend to improve therapeutically relevant selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 659–666 (2009).

Gulati, A. S., Nicholson, M. R., Khoruts, A. & Kahn, S. A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Across the Lifespan: Balancing Efficacy, Safety, and Innovation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 118, 435–439 (2023).

Pilard, C. et al. Cancer immunotherapy: it’s time to better predict patients’ response. Br. J. Cancer 125, 927–938 (2021).

Chang, T. G. et al. LORIS robustly predicts patient outcomes with immune checkpoint blockade therapy using common clinical, pathologic and genomic features. Nat.Cancer https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-024-00772-7 (2024).

Wong, P. K. et al. Closed-loop control of cellular functions using combinatory drugs guided by a stochastic search algorithm. P Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 5105–5110 (2008).

Ho, D. Artificial intelligence in cancer therapy. Science 367, 982–983 (2020).

Antonelli, A. C., Binyamin, A., Hohl, T. M., Glickman, M. S. & Redelman-Sidi, G. Bacterial immunotherapy for cancer induces CD4-dependent tumor-specific immunity through tumor-intrinsic interferon-gamma signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 18627–18637 (2020).

Moreo, E. et al. Novel intravesical bacterial immunotherapy induces rejection of BCG-unresponsive established bladder tumors. J. Immunother.Cancer 10, https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-004325 (2022).

Pierce, S., Geanes, E. S. & Bradley, T. Targeting Natural Killer Cells for Improved Immunity and Control of the Adaptive Immune Response. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol 10, 231 (2020).

Malhotra, A. & Shanker, A. NK cells: immune cross-talk and therapeutic implications. Immunotherapy 3, 1143–1166 (2011).

Mukherjee, N. et al. Intratumoral CD56(bright) natural killer cells are associated with improved survival in bladder cancer. Oncotarget 9, 36492–36502 (2018).

Aran, D. Cell-Type Enrichment Analysis of Bulk Transcriptomes Using xCell. Methods Mol. Biol. 2120, 263–276 (2020).

Kamoun, A. et al. A Consensus Molecular Classification of Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 77, 420–433 (2020).

Dong, C. Cytokine Regulation and Function in T Cells. Annu Rev. Immunol. 39, 51–76 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Cytokines: From Clinical Significance to Quantification. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 8, e2004433 (2021).

Wu, T. Z. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation-Amsterdam 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 (2021).

Wang, S., Riahi, R., Li, N., Zhang, D. D. & Wong, P. K. Single Cell Nanobiosensors for Dynamic Gene Expression Profiling in Native Tissue Microenvironments. Adv. Mater. 27, 6034–6038 (2015).

Riahi, R. et al. Mapping photothermally induced gene expression in living cells and tissues by nanorod-locked nucleic acid complexes. ACS Nano 8, 3597–3605 (2014).

Oh, D. Y. et al. Intratumoral CD4(+) T Cells Mediate Anti-tumor Cytotoxicity in Human Bladder Cancer. Cell 181, 1612–1625 e1613 (2020).

Torab, P. et al. Three-Dimensional Microtumors for Probing Heterogeneity of Invasive Bladder Cancer. Anal. Chem. 92, 8768–8775 (2020).

Acknowledgements