Abstract

The increasing complexity of life science research requires laboratory tools that combine precision, automation, and accessibility. Conventional liquid handling and imaging systems are either separated or integrated at high cost, limiting their adoption in small-scale laboratories. Here we show that G-Bot, a compact five-axis platform, integrates automated liquid handling, live-cell imaging, and real-time data processing into a single system. G-Bot performs complex workflows, e.g., including cell seeding, drug dosing, media exchange, and long-term live-cell imaging, while maintaining stable culture conditions through integrated incubator and stage-top regulation modules. Its imaging capabilities span cells, organoids, and small organisms such as zebrafish larvae, providing high-content, physiologically relevant data. Unlike pipette-based systems, G-Bot employs a tubing-based dispensing mechanism for precise reagent delivery with minimal waste. By unifying liquid handling, imaging, and analysis, G-Bot streamlines laboratory-scale workflows, improves reproducibility, and bridges the gap between manual methods and costly industrial automation, offering broad utility in research and drug discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Manual micropipettes, with varying volumes and precision levels, are widely used in laboratory processes across fields such as chemistry, molecular biology, and biotechnology1,2. These micropipettes operate via a piston-driven air displacement mechanism, allowing for liquid transfers ranging from 0.1 µL to 1000 µL. While manual micropipettes offer precision for volumes above 1 µL, they exhibit higher error rates for smaller volumes due to factors such as user variability, temperature changes, and tip contamination3,4,5. These errors affect the reliability of experimental results and increase costs6. Additionally, repeated manual micropipetting exposes users to ergonomic risks, such as musculoskeletal disorders, and limits scalability due to lower throughput and the potential for cross-contamination7. To address these challenges, automated liquid handling (ALH) systems are increasingly employed to improve consistency and reduce contamination in cell culture and biological experiments8. Traditional systems that rely on automated pipette tip replacement offer improvements in throughput and accuracy but come with their own limitations, including high upfront costs, the need for continuous tip replacement, and reduced efficiency for high-volume tasks9. To mitigate these drawbacks, alternative liquid handling technologies, such as tubing-based systems, have emerged10,11,12. These systems offer continuous flow operations, reduce waste, and are better suited for large-volume applications. Syringe pumps, in particular, provide fine control over flow rates and are frequently used in automated systems for precise liquid handling13,14,15,16,17.

While automation has significantly improved liquid handling efficiency, the integration of imaging with liquid handling remains a challenge. In many life science applications, particularly in drug discovery and cell culture studies, the ability to monitor cell behavior and confluence in real-time is crucial. Emerging platforms like SM-Omics have demonstrated how spatial transcriptomics and multiplex protein detection can be combined with automated library preparation to address these challenges on a high-throughput scale18. In that sense, imaging technologies, when combined with liquid handling, could allow researchers to observe cellular responses immediately after seeding and drug exposure, capturing critical data that informs experimental decisions. Automated imaging can also enhance the accuracy of confluency or viability measurements and eliminate user variability19. Moreover, automated imaging may accelerate workflows by enabling high-throughput monitoring of multiple samples, reducing the time needed for manual microscopy and increasing data reliability20,21. Recent guidelines, such as those described in DNA Repair (2024), provide step-by-step frameworks for establishing entry-level automated imaging systems using platforms like Opentrons and high-content imaging, underscoring the growing accessibility of automation in small-scale labs22.

To address this need, several commercial platforms, including those from BioTek (Agilent) and Revvity (formerly PerkinElmer), offer integrated systems that combine liquid handling and high-content imaging within a single device. BioTek’s Cytation series, for example, supports simultaneous imaging and reagent dispensing through optional Dual Reagent Injector Modules, which allow the handling of two independent liquids. These injectors are primarily designed for rapid dispensing into individual wells with precise timing, suitable for applications like kinetic assays. To scale up throughput, BioTek also offers the BioSpa 8 Automated Incubator, which enables the automated transfer and handling of up to eight microplates between the incubator and other compatible instruments. However, each plate processed within this system remains limited to the same two-liquid configuration provided by the injector module. Revvity’s high-content imaging systems (e.g., Opera Phenix) similarly offer advanced optical capabilities and integration with automated liquid handlers, but these platforms typically require external robotic arms or scheduling software to manage plate transfer and liquid dispensing across multiple stations. As such, while these systems support high-throughput workflows, they often involve substantial infrastructure, cost, and complexity. While these approaches are effective for high-throughput screening across multiple microplates in pharmaceutical and biotech industries, they remain cost-prohibitive for many research laboratories and are optimized for large-scale automation rather than small-scale experimental workflows. In addition to commercial approaches, open-source initiatives such as the PHIL pipetting robot have aimed to provide basic automation at low cost (sub-600 USD) using 3D-printed components and Arduino control10. These low-cost modular platforms emphasize affordability and user-friendliness; however, they typically lack integrated imaging, environmental control, or the flexibility required for more complex experimental workflows.

In this work, we introduce G-Bot, a compact and integrated platform that performs both automated liquid handling and real-time imaging at a cost below 10,000 USD, substantially lower than commercial systems primarily designed for high-throughput industrial applications. G-Bot is therefore uniquely positioned to democratize access to laboratory automation, providing a budget-friendly solution for academic researchers and small-scale laboratory workflows without compromising functionality. G-Bot utilizes four linear axes and one rotational axis, enhanced by image processing and calculation algorithms. This integration allows operators to perform automated experiments with real-time imaging, significantly reducing experimental time. G-Bot integrates a fifth rotational axis, unlike commercial systems limited to x-y-z motion, enabling sample tilting for delicate liquid handling and uniform cell seeding. In addition to its liquid handling and imaging capabilities, G-Bot also features an integrated Incubator Module that maintains controlled environmental conditions, including temperature, humidity, and CO₂ levels, ensuring sample stability during liquid handling processes. Moreover, to support extended live-cell imaging experiments, G-Bot incorporates a Stage-Top Regulation Module, which provides localized CO₂ and temperature control directly at the imaging site, preserving optimal culture conditions without the need for external incubators. Together, these modules play a critical role in maintaining sample durability during long-term liquid handling workflows and real-time imaging applications.

Results

Overview of the technology

Figure 1A, B shows the schematic illustration and the photograph of G-Bot, which consists of six modules. The technology employs an Imaging Module that allows high-resolution and real-time live cell imaging for confluence monitoring. The Flow Module provides high-resolution dispensing and aspiration of diverse liquid volumes and enables continuous flow rate management. The Control Module enables precise motion on the containers along three axes. In addition to the regular three-dimensional motion, we incorporated a rotational axis that enables angular motion for delicate liquid handling procedures. A linear stage was also integrated, separating the operation of the Imaging and Control modules, allowing coordinated and sequential movements without interference. The system also incorporates an Incubator Module, ensuring that the cells and the associated solutions are maintained at suitable temperature, pH and humidity during liquid handling processes. The Stage-Top Regulation Module enables localized environmental control during imaging by providing CO₂ and temperature regulation directly at the sample stage, supporting long-term live-cell monitoring without sample disturbance. The Software Module enables the control of the hardware parameters from a single panel for image recording, liquid-flow automation and maintaining healthy cell proliferation, as well as facilitates image processing for high-content scientific images of biological samples and confluency calculation with the use of captured cell images. By utilizing a compact design with minimal equipment and accessories, G-Bot offers an accessible and cost-effective solution for automating sample preparation and analysis in small-scale laboratory settings, reducing the need for extensive human intervention and specialized technical expertise.

A Schematic illustration and (B) photograph of G-Bot, which integrates six functional modules within a compact benchtop design. Created with BioRender.com. The Imaging Module provides high-resolution, real-time live-cell imaging for monitoring confluence and viability. The Flow Module enables precise dispensing, aspiration, and continuous flow control of liquid volumes. The Control Module manages motion across three linear axes, while additional linear and angular axes support delicate liquid handling operations. The Incubator Module maintains appropriate temperature, pH, and humidity for cells and reagents during assays. The Stage-Top Regulation Module delivers localized CO₂ and temperature control at the sample stage for long-term live-cell imaging without disturbance. The Software Module coordinates hardware operation, liquid handling automation, and imaging, while also supporting real-time image processing and confluency calculations.

Large field-of-view imaging with G-Bot

Figure 2A shows the optical setup of the Imaging Module integrated into the axes of the Control Module to bring a three-dimensional imaging ability (see Supplementary Fig. 1A in the Supplementary Information for the photograph of the Imaging Module). In the context of this article, we focused on monitoring cells seeded on 96-well microplates to highlight G-Bot’s large FOV imaging ability. In order to illuminate the samples, we employed a custom-made white LED array (light-emitting diode) containing 96 LEDs that are connected in parallel, aligning with each well in the microplate. The microplate is positioned on a custom-made microplate holder with a white acrylic base defining a finite distance between the light source and the sample, and aligning the microplate wells with the LED array to ensure uniform sample illumination (see Supplementary Fig. 1B in the Supplementary Information for the photograph of the LED array and the microplate holder). The light passing through the sample is collected by an infinity-corrected long-working-distance objective lens with 5× magnification and ~34 mm working distance (Mitutoyo America Corporation). This long working distance prevents the collision between the sample and the objective lens in the presence of an upright setup configuration. The rationale behind our preference for an upright methodology, as opposed to the inverted approach typically utilized in cell monitoring applications, stems from the presence of the rotational stage housing the microplate holder and the LED array, which blocks light collection from underneath the sample. The collected light was transmitted to a tube lens (Thorlabs Inc.), directing the beam to a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) camera (Thorlabs Inc.) with minimal divergence. Although the 96-LED configuration was used to demonstrate uniform illumination with a 96-well plate, G-Bot is not restricted to this specific format. The system has been successfully tested with various sample holders, including Petri dishes, 6-well plates, and glass slides. To ensure homogenous illumination across different sample types, a diffuser film was integrated into the LED array setup, as illustrated in Fig. 1A. This diffuser minimizes intensity variations and prevents shadowing effects, thereby providing consistent image quality across multiple experimental conditions.

A Schematic illustration of the optical setup of the Imaging Module. Photographs captured by the Imaging Module regarding (B) 48-hour-old WT (wild type) AB strain zebrafish larva, (C) rabbit rectal tissue, (D) MCF-7 breast cancer cells, and (E) L929 mouse fibroblast cells. F Schematic illustration of the Flow Module. G Percentage error in the resulting volumes dispensed by the Flow Module for different target volumes of DI water. Black, blue, red and yellow: 1, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.08 μL (n = 10 repetitions for each dosing volume). H Percentage error in the seeded Jurkat cells for different target cell densities. Black, blue, red, yellow and magenta: 10 K, 20 K, 30 K, 50 K and 100 K cells/mL (n = 5 repetitions for each cell density). The box plots indicate the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile); the center line represents the median; whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 × interquartile range; data points beyond this range are plotted individually as outliers; and squares indicate the mean values. Please note that the whiskers do not always represent the absolute minimum and maximum values when outliers are present. I Fluorescence images of MCF-7 cells remaining after the wash times of 1 and 5 for G-Bot and manual liquid handling using a pipette. In the figure, the top figures show the initial fluorescent intensities, and the bottom figures are the remaining fluorescence intensities after the PBS wash. J Remaining fluorescence intensities (FL), e.g., percentage of remaining over initial intensity, for G-Bot (blue) and manual liquid handling (red).

The Imaging Module has a 2.1 mm × 1.3 mm FOV (See Supplementary Fig. 1C in the Supplementary Information for the details of the system FOV). The resolution of the Imaging Module was determined with the use of a USAF 1951 test chart (Supplementary Fig. 2A)23,24,25, which yields a resolution of ~3.1 µm (see Supplementary Fig. 2B and the Supplementary Information for the resolution calculation). Utilizing this wide FOV and high-resolution imaging capability, the platform can image a wide range of biological samples from large organisms and tissues to single-cell precision. Examples include 48-hour-old wild-type (WT) AB strain zebrafish larva (Fig. 2B), rabbit rectal tissue (Fig. 2C), MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Fig. 2D), and L929 mouse fibroblast cells (Fig. 2E) (see “Methods” section for the culture protocols of MCF-7 and L929 cells, and zebrafish larva). This versatility in imaging, combined with G-Bot’s high-resolution and wide FOV capabilities, makes it a powerful tool for life science applications, enabling the detailed study of a wide range of biological specimens, from large tissues to individual cells, in both research and clinical settings.

Precision liquid handling with G-Bot

The Flow Module consists of two components, e.g., (i) a syringe pump integrated with a rotary valve, and

(ii) a tubing holder integrating this module into the Control Module. Figure 2F, Supplementary Fig. 3A in the Supplementary Information show the schematic illustration and the photographs for the constituting components of the Flow Module, respectively. For the solution transfer between all components, PTFE (PolyTetraFluoroEthylene or Teflon) tubing was employed due to its chemical resistance, ensuring high durability, low surface energy, minimizing the risk of contamination or clogging, and strong biocompatibility. The tubing has an internal diameter of 0.5 mm, i.e., it enables the handling of small sample volumes via facilitating liquid processing with reduced dead volume. The solutions are transferred to the microplate wells by connecting them to different ports of the rotary valve, located on top of the syringe pump, featuring nine ports. The first six ports are input ports connected to the solutions, one port is for the waste bottle, one port is the output port connected to the tubing holder, and the last one is connected to the syringe. The rotary valve (Advanced MicroFluidics) has no dead volume, which refers to the volume that is stuck in the system; in other words, the volume that is not cleanly swept and relies on diffusion to clear out. On the other hand, it has 2.8 μL carryover volume, which is the volume of liquid that could be mixed with the next liquid, while not stuck in the system, but could be swept with the next liquid passing. The total internal volume of the valve is 4.5 μL. These values are critical for reducing the risk of cross-contamination between different liquids or solutions. Considering the internal volume of the valve (4.5 μL) and the volume of the tubing ( ~ 120 μL), in order to ensure complete filling and removal of any residual air or previous liquids, the system dispenses slightly more liquid than the total dead volume, e.g., 126 μL, before starting liquid handling with the sample of interest. Particularly for this study, we used a syringe pump employing a replaceable glass syringe with a volume of 1000 μL. The syringe pump has a minimum and maximum flow rates of 10 μL/min and 30 mL/min, where the volume delivered in the function of the plunger is 42 nL for high resolution and 330 nL for standard resolution. This wide-range flow rate capability allows flexibility in liquid handling operations. We tested the accuracy of G-Bot’s pump by dispensing 80, 250, 500, and 1000 nL of DI-water under high resolution with 10 μL/min flow rate (Fig. 2G). We then measured the dispensed volumes using an electronic balance with 10 ng precision across 10 repetitions. The resulting volumes deviated from the target volumes by less than 5%, which is critical for applications requiring precise dosing of very low analyte volumes. To quantitatively assess the reproducibility of G-Bot’s liquid handling performance, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV), e.g., \({{{\rm{CV}}}}(\%)=({{{\rm{Standard\; Deviation}}}}/{{{\rm{Mean}}}})\times 100\). For all dispensed volumes tested in replicate trials, the CV remained below 5%, indicating excellent precision and minimal variability across repeated liquid handling tasks. The performance metric reinforces G-Bot’s suitability for sensitive experimental workflows that require consistent reagent delivery. This highly precise liquid handling capability enables accurate cell seeding. To demonstrate this capability, we seeded Jurkat cells, a suspension cell model, into microplate wells at densities ranging from 1 × 103 to 1 × 105 cells/mL in 100 µL cell medium (see “Methods” section for the culture protocol of Jurkat cell). An initial cell density of 5 × 105 cells/mL (determined by flow cytometry) was diluted at varying concentrations, following the G-Bot’s cell seeding methodology outlined in the Methods section. Figure 2H illustrates the discrepancies in the cell density measured by flow cytometry (Agilent NovoCyte) for each target concentration (n = 5 replications), showing variations below 5% across all concentrations. Here, the CV for cell seeding was consistently below 4%, demonstrating G-Bot’s ability to uniformly distribute cells across wells. This level of reproducibility is essential for downstream applications such as drug screening and viability assays, where uniform initial cell density directly affects assay outcomes. The synchronized operation of the syringe pump and the rotary valve was achieved by connecting their drivers to a single microcontroller that controls them through a serial communication protocol. Rotating between different ports to perform withdraw and infuse modalities enables continuous flow for the samples with volumes that are larger than the syringe volume (see Supplementary Fig. 3B, Supplementary Information for the withdraw and infuse functions). The Flow Module could perform high-precision liquid dispensing and aspiration that allows numerous operations, e.g., cell seeding, drug dosing, culture medium change, or fast liquid handling for microplate wells and overall system cleaning. Interchanging between high and low flow rates allows multistep protocols to be executed in optimal time, e.g., using low flow rates for cell seeding and high flow rates for medium dispensing or aspiration. For example, Supplementary Movie 1 shows the medium change operation, where the sequential steps of medium aspiration, PBS wash, and medium dispensing into the well are applied in order. G-Bot is also capable of self-cleaning, allowing all internal Flow Module components to be rinsed with a cleaning buffer, e.g., PBS. The waste generated during this process is subsequently dispensed into the PBS waste-bottle, ensuring efficient and hygienic operation.

As shown in Fig. 2F, Supplementary Fig. 3A in the Supplementary Information, the tubing holder consists of two main components, where the tubing is securely fastened using a luer fitting that integrates these components into an acrylic part mounted on the lead screw nut of the linear stage in the Control Module. The upper component is made of clear resin, allowing the tubing passing through it to be visible, which ensures detection of liquid leakage in the system. The lower part, manufactured using rigid resin, due to its enhanced mechanical properties, ensuring stable positioning of the output tubing. Additionally, the long tube section of the lower part surrounding the tubing ensures the tubing's stability during liquid flow.

Flow module enables precise liquid handling for delicate samples

Precise liquid handling is crucial in life science applications as it ensures accurate experimental conditions, which are essential for reproducibility and reliability of the results. Gentle handling minimizes cell damage and loss, which is critical when working with delicate biological samples such as primary cells, tissues, patient samples or fragile biomolecules. It also prevents cross-contamination and maintains sample integrity, which is vital for downstream applications like diagnostics, drug development, and biological research. In this section, we conducted an experiment to compare the precision of G-Bot with manual liquid handling using micropipetting. Initially, we seeded adherent MCF-7 cells in a CO2 incubator for 10 min, allowing them to weakly adhere to the surface with many cells remaining in suspension. Next, G-Bot performed microplate well washing with PBS for the numbers 1 to 5, specifically aspirating and dispensing the medium. At the same time, we repeated the same process manually using micropipettes. By tagging the cells with Hoechst 33342 stains (see “Methods” section for live cell staining protocol), we compared the number of remaining cells after each wash by monitoring the change in the total fluorescence intensity. Here, while we acknowledge that aspirating freshly seeded adherent cells is not a routine practice in typical workflows, we deliberately selected this sensitive model system to demonstrate G-Bot’s gentle handling capability under challenging conditions that emphasize the importance of mechanical precision and sample preservation. Figure 2I shows the fluorescence images of the cells (top) before and after (bottom) the wash times of 1 and 5 for G-Bot and manual micropipetting. Figure 2J shows the remaining fluorescence intensity (the percentage ratio between the initial fluorescence intensity and the fluorescence intensity after the wash) for G-Bot (blue bars) and manual liquid handling (red bars) under different numbers of washes. For all number of washes, the number of remaining cells is higher for G-Bot, demonstrating that G-Bot’s liquid handling significantly reduced cell loss compared to manual pipetting, highlighting its superior precision and efficiency.

Five-axis control for high precision liquid handling and imaging with G-Bot

The five-axis Control Module is composed of three main components, e.g., (i) a three-axis CNC (Computer Numerical Control, Stepcraft GmbH & Co.) that allows motion along x, y and z directions, (ii) a linear stage (fourth axis) that is integrated to the CNC to control the position of the tubing holder, and (iii) a rotation stage (fifth axis) controlling the position of the microplate holder to realize safe liquid handling in the microplate wells. Figure 3A, Supplementary Fig. 4A in the Supplementary Information show the schematic illustration and the photograph of the Control Module, respectively. The Imaging Module is mounted on the three-axis CNC, and the tubing holder of the Flow Module is integrated into the linear stage, which enables imaging and liquid handling sequentially at any position on the microplate. The linear motion of the CNC and the linear stage, as well as the angular motion of the rotation stage, are controlled by a computer through a control unit. Position control of the axes is ensured by generating geometric codes (G-code) on the processor that are transferred to the control unit. The linear stage is designed to prevent the tubing holder from colliding with the microplate during cell monitoring with the Imaging Module. As depicted in Fig. 3B-left, during the operation of the Flow Module, the liner stage moves the tubing holder toward the microplate, while the objective lens on the CNC axis remains at a certain distance from it. When the Imaging Module is activated (Fig. 3B-right), the optical setup is lowered towards the microplate via the CNC axis, and the linear stage raises the tubing holder. Supplementary Fig. 4B in the Supplementary Information shows the photographs of these two scenarios. For the fifth axis, the LED array and the microplate are mounted on the rotation stage via the microplate holder. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 3C, the axis of the rotation stage is tilted by 10 degrees to facilitate liquid dispensing or aspiration from the wall of the microplate well (see Supplementary Fig. 4C in the Supplementary Information for the photograph of the tilted rotation stage). This strategy prevents the delicate samples from being damaged during the liquid handling process. In the rotation stage, a six-axis gyroscope is utilized to ensure precise positioning and velocity estimation through the processing of incoming data by a Kalman filter26. The gyroscope compensates for calibration and position loss that may occur due to an emergency stop or any malfunction. In cases of user intervention, it ensures system calibration to correct any resulting deviations. Upon system startup, the gyroscope provides position data to the interface, and the motor moves to the home position, which ensures that the microplate remains level. Furthermore, the CNC system in G-Bot is designed for high-precision operations and incorporates an automatic and integrated calibration process. Each time an application is launched, the system automatically initiates the calibration procedure, ensuring that all components are synchronized and properly aligned. This automated calibration enhances operational accuracy and repeatability, eliminating the need for manual adjustments while maintaining consistent performance across experimental workflows (see Methods section for the details of the system calibration).

Schematic illustrations of (A) the Control Module, (B) the synchronized operation principle of the Imaging and Flow modules with the use of the CNC axis and the linear stage, and (C) tilting a microplate via the rotation stage during the dispensing or aspiration process with the Flow Module. D Schematic illustration of the precision test, where the Control Module moves the Imaging Module over a 20 cm travel distance, where a micrometric ruler was used to determine the variation between each motion cycle. The figure also shows the image of the ruler captured with the Imaging Module. E Variations across the XY-plane between each travel for the motions along the x-axis (black squares) and the y-axis (red squares) for n = 23 repetitions. F Image of MCF-7 cells under the cell medium and after the aspiration of the medium. G Fluorescence intensity (FL) vs. DAPI concentration, where the inset shows the exponential model (red curve) fitted to the mean fluorescence intensity data (black squares) for n = 12 replicates. H Fluorescence intensity after different numbers of PBS washes by dipping the tubing tip (Gray: FL after dipping, White: FL measured for PBS) for n = 12 replicates. In the figures, the bars represent the mean value of the experimental data, and the error bars are twice the standard deviation. I Schematic illustration showing how the rotation stage enables gentle sample shaking to improve cell distribution. Microscope images of the seeded MCF-7 cells on a 6-well microplate at t = 1 h and t = 48 h with the shaking mode (J) ON and (K) OFF.

We tested the accuracy of G-Bot’s positioning by shifting the Imaging Module over a total distance of 20 cm as schematically illustrated in Fig. 3D. To do this, we used a micrometric ruler and centered a black spot as a reference. Images of the ruler were taken as the module moved 10 cm forward and backward. The 70 µm black spot (Fig. 3D) was tracked, while at each return, a picture was captured to calculate the variation after each motion cycle. Figure 3E shows the variations in the XY-plane for motions along the x-axis (black squares) and the y-axis (red squares). After 23 repetitions, the maximum positioning error was found to be less than 5 µm. This precise positioning capability ensures minimal distortion in imaging and enhances the accuracy of liquid handling. For example, Supplementary Movie 2 demonstrates how the Control Module allows the Flow Module to precisely dispense cell media into the wells of a 96-well microplate, creating a microarray that displays the letters, e.g., IBG, by selectively filling the designated wells. This precise capability also enables the imaging module to capture sample images from the desired wells on a 96-well microplate, as demonstrated in Supplementary Movie 3.

The synchronized operation of the Imaging and Flow modules also enhances the resolution capacity of the platform. As shown in Fig. 3F-left, the image of cells taken under the cell medium appears blurred. This blurriness, observed when imaging adherent cells despite the medium’s minimal thickness, is primarily due to the refractive index mismatch between the medium and the microplate well. This mismatch causes inconsistent light refraction, resulting in image distortion. By aspirating the medium before imaging the samples, these refractive index mismatches are eliminated, along with any scattering issues and additional optical path length. This process results in clear and focused images, as highlighted in Fig. 3F-right.

Contamination-free liquid handling through tubing tip washing

As our liquid handling methodology involves using tubing, we implemented a cleaning procedure to eliminate contamination from the tubing interacting with the samples in the microplate wells. This procedure ensures the removal of any residues from the tip of the tubing. To demonstrate our contamination-free liquid handling methodology, we deliberately contaminated the tubing tip with a high concentration of DAPI stain and then cleaned it by dipping the tubing multiple times in the PBS wash-bottle (volume of 15 mL). Figure 3G shows the fluorescence intensity for different concentrations of DAPI stain diluted in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich®), ranging from 0.1 to 10 µM, along with the one measured for PBS with a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Figure 3G-inset shows the mean intensity values of 12 replicates, where we fitted an exponential model to the experimental data, e.g., \({{{\rm{FL}}}}=-0.64+1.1{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{\frac{\left[{{{\rm{DAPI}}}}\right]-0.87}{4}}\), where FL is the fluorescence intensity (a.u.) and [DAPI] is the dye concentration in µM. Figure 3H shows the fluorescence intensity after rinsing the tubing tip by dipping it into the PBS wash-bottle (12 replicates) for different numbers of washes. Here, the tubing tip was initially dipped into a microplate well containing 100 µL of 100 µM DAPI solution, and then dipped into the PBS wash-bottle for the number of washes, e.g., 0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, and 10. After the washing step, the tubing was dipped into 100 µL PBS in a microplate well for fluorescence measurement. For example, wash number 0 indicates the tubing contaminated with DAPI that is directly dipped into PBS for fluorescence measurement. Using the exponential fit, we determined that the tubing tip was initially contaminated with ~350 nM of DAPI stain, which decreased to ~67 nM and ~25 nM after the first and second dippings, respectively. The third dipping fully cleansed the tubing tip, e.g., the fluorescence intensity (gray bars) converged to the value determined for PBS (white bar). Supplementary Movie 4 shows the final step of the system cleaning process. In this movie, PBS has already been aspirated from the components of the Flow Module that were used in the conducted protocol. PBS is then dispensed into the PBS waste-bottle (50 mL), and the tubing tip is dipped into the PBS wash-bottle for the final cleaning.

G-Bot facilitates uniform cell seeding and growth via rotational shaking

The rotation stage of G-Bot enables a shaking mode (Supplementary Movie 5) that significantly improves cell seeding uniformity, which is critical for achieving reproducible and physiologically relevant cell culture conditions. To demonstrate this capability, MCF-7 cells were seeded at an initial density of 30 × 10³ cells/mL (2 mL total volume) in a 6-well microplate and monitored over a 48-h period. As shown in Fig. 3I, activation of the shaking mode during the early stages of incubation resulted in a homogenous distribution of cells across the well, promoting uniform attachment and growth. In contrast, when shaking was omitted, cells exhibited pronounced clustering and uneven spatial distribution immediately after seeding. Microscope images in Fig. 3J, K show the spatial distribution and morphological changes of cells over a 48-h period under shaking and non-shaking conditions after seeding. The initial heterogeneity may lead to several detrimental effects on cell viability and morphology. In densely populated regions, excessive cell–cell contact can induce contact inhibition and promote cellular stress responses27. Meanwhile, sparsely populated zones may experience reduced paracrine and juxtacrine signaling, impairing intercellular communication and coordinated behavior28. Within aggregated clusters, nutrient and oxygen limitations may create local hypoxia and nutrient depletion, while the accumulation of waste products can further exacerbate cytotoxic stress29. Collectively, these previously reported mechanisms could underlie the reduced viability, cell death, and poor morphological integrity observed in our experiments after 48 h (Fig. 3J, K). By maintaining a gentle, continuous oscillatory motion, G-Bot’s shaking mode effectively prevents early aggregation, ensures even distribution of cells, and supports stable microenvironments across the culture well. This functionality is particularly advantageous for applications requiring uniform cell seeding, consistent cellular morphology, and high reproducibility, such as drug testing, proliferation assays, and long-term live-cell imaging experiments.

Precision environmental control with G-Bot

Figure 4A, Supplementary Fig. 5A in the Supplementary Information provide the schematic illustration and the photograph of the Incubator Module, respectively. The module is equipped with two positive temperature coefficient (PTC) heaters to maintain the internal temperature. To ensure uniform air distribution, a fan is incorporated. A pan filled with distilled water is used for evaporation over time due to the internal heat, which increases the humidity inside the incubator. CO2 gas is employed for pH control of the cell medium. The gas is released from a dual-regulated gas tank, and a solenoid valve maintains controlled gas flow. Temperature, humidity and CO2 parameters are continuously monitored by the temperature-humidity and CO2 sensors, and maintained by a microcontroller with a feedback mechanism, striving to uphold these parameters at the desired values. The microcontroller, sensor drivers and a power source regulating the feed potential for the electronic parts are located in an electronics box (Supplementary Fig. 5B in the Supplementary Information). Additionally, the incubator parameters are displayed on an LCD (liquid-crystal display) screen located in the casing. In order to maintain the temperature at 37 °C and the CO2 at 50,000 ppm (0.5%), we implemented a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller that can be described as in Eq. (1)

where \({{{{\rm{K}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) is the proportional gain coefficient, \({{{{\rm{K}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) is the integral gain coefficient, and \({{{{\rm{K}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) is the derivative gain coefficient revealing the controller output \({{{\rm{u}}}}\left({{{\rm{t}}}}\right)\) for the system error \({{{\rm{e}}}}\left({{{\rm{t}}}}\right)\)30. Figure 4B shows the flowchart of the PID controller algorithm. The proportional term generates an output value directly proportional to the current error. The integral term is influenced by both the magnitude and the duration of the error, playing a crucial role in ensuring long-term accuracy. The derivative term, calculated based on the error’s rate of change, predicts future error by considering the current rate of change. Together, these terms control the system’s response, facilitating error correction and stabilization (see Supplementary Information, Supplementary Fig. 5C for the details of the PID controller methodology).

A Schematic illustration of the Incubator module (LCD: liquid-crystal display, PTC: positive temperature coefficient). B Flowchart of the PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controller algorithm. C Temperature, (D) CO2, and (E) humidity levels were maintained within the incubator casing, monitored over a five-hour duration. Figure insets show the zoomed data, where the temperature, CO2 and humidity values are displayed for the time windows highlighted with the black dashed boxes. F Schematic illustration of the Stage-Top Regulation Module. G Temperature (T, orange) and CO2 (green) levels were maintained within the stage-top cover over a six-hour duration.

The algorithm continuously collects temperature data from the temperature sensor, utilizing this information as an input for the PID controller. Employing pulse-width modulation (PWM) signals, the PID controller adjusts the voltage level of the PTC heaters to sustain the predefined temperature set point. Figure 4C shows a five-hour-long measurement demonstrating that temperature is maintained at 37 °C with a variation of only 0.3 °C. For the regulation of the CO2 concentration, the CO2 sensor consistently measures the concentration value, feeding it into the PID algorithm. Both temperature and CO₂ levels were sampled at 4 Hz. Control over the concentration is achieved by manipulating the solenoid valve connected to the CO2 tank, adjusting the opening and closing based on the measured concentration. The algorithm utilizes a set of conditional statements with varying delay settings for different concentration ranges, ensuring precise concentration control by regulating the solenoid valve’s opening and closing. The PID controller calculates the duration for which the solenoid valve should remain open to minimize the disparity between the desired and the current concentration values. As long as the solenoid valve is open, 100% CO2 is introduced from the CO2 tank, and the valve closes when the concentration reaches 50,000 ppm. Figure 4D shows that the CO2 concentration could be maintained at 5% with a 0.2% variation. For humidity control, we follow a passive method as in the commercial CO2 incubators, e.g., humidity is based on evaporation over time, where the temperature-humidity sensor is employed only for monitoring the humidity level. Figure 4E shows that humidity is maintained at 93.6% with a 0.8% variation, demonstrating that the precise control over temperature ensures stability in humidity.

Here, G-Bot’s ability to supply high-quality cell media and other culture or drug solutions is essential during the workflows of a large number of samples, where each sample undergoes multiple rounds of liquid handling for tasks such as cell seeding, drug dosing or media replacement. Since the process can be time-consuming, especially with multiple wells and repeated liquid handling for each, maintaining the stability of temperature, pH, and humidity within the solutions ensures the viability and health of the cell cultures throughout the procedure. This continuous provision of optimal conditions supports consistent cellular proliferation and prevents fluctuations that could compromise experimental accuracy or sample integrity, particularly in long-term experiments.

Localized environmental regulation for imaging stability

To complement G-Bot’s main Incubator Module, which regulates global environmental conditions during extended liquid handling operations, we developed an additional Stage-Top Regulation Module designed to maintain localized environmental control directly at the imaging site. Figure 4F, Supplementary Fig. 6A in the Supplementary Information shows the schematic illustration and the photograph of the module, respectively. This module ensures stable temperature and CO₂ levels specifically during long-term live-cell imaging, where uninterrupted physiological conditions are crucial for preserving cell viability and behavior under observation. Stage-Top Regulation Module consists of a compact external control box equipped with a panel heater, a valve, CO₂ and temperature/humidity sensors, and two fans (See Supplementary Fig. 6B for the photograph of these components). Regulated air is continuously delivered to the imaging region via a hose, forming a closed loop with the microplate sealed by a transparent stage-top cover. This localized system enables rapid adjustment of environmental conditions while minimizing physical disturbances to the sample. To optimize system responsiveness and stability, a similar PID control algorithm as used in the main Incubator Module was implemented to regulate both CO₂ concentration and temperature within the Stage-Top Regulation Module. The microcontroller, the driver for the CO2 sensor, two relays and two power sources that regulate the feed potential for the electronic parts are located in an electronics box (Supplementary Fig. 6C in the Supplementary Information). To assess the precision of the system, we conducted a five-hour stability test. Figure 4G presents the environmental data recorded during the experiment, demonstrating that the module maintained the temperature at 37 °C with a variation of only ±0.5 °C (orange curve) and CO₂ concentration at 5% with a fluctuation of ±0.1% (green curve), validating its reliability for extended imaging applications. By enabling real-time live-cell imaging directly under culture conditions, this localized regulation system provides significant advantages for long-term experiments involving proliferation analysis, drug response tracking, and dynamic morphological assessments. The Stage-Top Regulation Module allows G-Bot to deliver uninterrupted imaging sequences without removing the sample from the incubated environment, supporting higher data fidelity in biological research workflows.

G-Bot assesses cell confluency

The Software Module is comprised of two components: (i) image processing algorithms and (ii) a Graphical User Interface (GUI). In this section, we introduced the first algorithm of this module, which is the confluency analysis algorithm. Standardizing cell culture processes by tracking cell confluency is essential for biological research as well as the development and production of cell therapies, which require accurate and reproducible measurements. Confluency, which appears as a cobblestone-like pattern under phase-contrast microscopy, refers to the percentage of the surface area of a cell culture vessel covered by adherent cells31. This parameter is vital for ensuring the continuity of viable cell cultures32. Monitoring confluency is also essential for evaluating the antitumor effects of drugs, making confluency assessment critical for efficient, consistent, and early detection of issues in cell cultures33. Our confluency analysis algorithm evaluates the cell coverage area for the images captured with the Imaging Module (Box 1). Figure 5A shows the flow of the algorithm that starts with a Gaussian filter to reduce noise, enhancing the robustness of subsequent variance and entropy calculations. (i) Variance filtering identifies significant intensity changes, e.g., cell edges, by calculating local variance. The gradient of the variance image is computed to further emphasize edges, followed by double-thresholding to create a binary mask distinguishing cells from the background. (ii) Entropy filtering measures image texture complexity, creating another binary mask through double thresholding. (iii) These masks are combined using a logical OR operation, ensuring all identified regions are included in the final mask. (iv) The combined mask undergoes morphological erosion to remove small noise and refine cell boundaries, followed by area thresholding to eliminate small regions unlikely to be cells. Confluency is then calculated by determining the proportion of the image covered by cells, counting the pixels identified as cells, and dividing by the total pixel count. Finally, the binary mask is overlaid on the original image to visually represent detected cell regions (highlighted in green). Figure 5B shows different confluency levels calculated by our confluency analysis algorithm.

A The flow of the confluency algorithm. In the figure, areas covered with cells are highlighted in green. B Calculated confluency values for different MCF-7 samples. C Focus stacking for 3D cell models of Huh-7 cells, with the extended depth of field exhibiting all 3D cell models along the same plane. n = 319 images were used to scan a depth of 1 mm, as shown in the schematic illustration. Created with BioRender.com. Zoom image shows the photograph of a single 3D cell model. The image stitching algorithm enables large FOV images developed for relatively large specimens, e.g., (D) fallopian tube tissue (n = 23 images, Image FOV = 4.4 mm × 3.3 mm) and (E) mouse embryo (n = 294 images, Image FOV = 16.6 mm × 11.08 mm). F Image of a WT AB zebrafish larva, where 32 images were used for stacking in two different frames, scanning a 1 mm height (a total of 64 images). These two frames were then stitched together to capture the whole specimen with an extended depth of field over a large field-of-view.

G-Bot creates images with extended depth of field

Focus stacking modality was integrated to overcome the limitation of shallow depth of field in microscopy, especially for optically thick biological samples such as organoids or zebrafish larvae34. This technique allows for the creation of a single image with an extended depth of field by combining multiple images taken at different focal planes (Box 2). The Laplacian filter is applied to each image to detect edges, crucial for focus stacking, as with the highest regions contrast indicating areas in focus35. This filter highlights these regions by calculating the second derivative of image intensity. The absolute values of the Laplacian responses across all images for each pixel position are compared, with the highest response indicating the most focused image at that pixel. This process is repeated for all pixels in the image stack to create a final composite image with maximum focus throughout. In this section, we demonstrated the focus stacking capability of G-Bot using the three-dimensional (3D) model of Huh-7 cells (see Methods section for the 3D cell culture protocol). 3D cell models are crucial for testing materials and drugs, as well as for examining cell biology and specific cell mechanisms36. While two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures are popular, they do not mimic the natural cell environment as they lack cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions. A more accurate in vitro model is the 3D culture, e.g., many cell lines have the ability to self-assemble, forming spheroids, which is one method of 3D culturing. Various systems, such as hanging drops, scaffolds, and hydrogels, are used for culturing cells in spheroids. These 3D cultures have applications in drug and nanoparticle testing and disease modeling. Figure 5C shows the stacked images of the 3D model created with 319 images, scanning 1 mm depth of 5-day-old spheroid formations suspended in a 1 mm thick Matrigel. The image, where all spheroid formations are monitored in a single frame, demonstrates G-Bot’s enhanced imaging capability.

G-Bot allows large field-of-view images

Image stitching modality was integrated into the system software to combine multiple images into a single, larger, and higher-resolution image, providing a comprehensive view that enhances the details and coverage. The code is designed to stitch together multiple images to form a larger composite image of biological samples (Box 3). It begins by reading and converting two initial images to grayscale, detecting and extracting speeded-up robust features (SURF) from these grayscale images. Correspondences between feature points in the images are identified, and a projective transformation is estimated to align the second image with the first. This transformation is refined to ensure accurate alignment. The images are then transformed and blended into a composite image. This process is repeated for each subsequent image, where each new image is matched to the existing composite image, transformed, and blended to update the overall image.

To demonstrate G-Bot’s capability in creating a larger FOV for samples in life sciences, we scanned a human histopathology sample, e.g., fallopian tube tissue (Fig. 5D). By stitching 23 images, we captured a 4.4 mm × 3.3 mm biological object in a single frame with high resolution. Imaging with a large FOV is crucial for histopathology samples as it allows for the examination of larger tissue sections in one image, ensuring comprehensive analysis and accurate diagnosis37. This wide FOV helps pathologists observe the overall tissue architecture, identify abnormalities, and detect rare events that might be missed in smaller, fragmented images. For instance, Fig. 5E shows the scanned image of an entire mouse embryo with the dimensions of 16.6 mm × 11.08 mm, demonstrating G-Bot’s similar scanning capability with the commercial whole slide scanners. Here, it is important to note that the previously described diffuser setup plays a key role in minimizing intensity variations and ensuring a homogenous background, which is critical for achieving uniform illumination across a large FOV. This consistent illumination improves the clarity of both fine structural details and the overall morphology of the specimen, eliminating uneven lighting artifacts that could affect image quality. The frame rate of our camera is 41 frames per second (fps), and the speed of our CNC axes is 120 mm/sec. Here, we ensured accurate alignment in stitching by having neighboring images overlap by half. Images of frames were taken every 0.5 s. Considering the FOV of the camera, we chose an axis speed to move from one frame to the next in 0.5 s. Thus, capturing a total of 294 images, and image processing took ~5 min. This speed is highly efficient for scanning entire specimens, ensuring rapid and comprehensive imaging.

Integrated focus stacking and image stitching capabilities of G-Bot

G-Bot’s ability to perform both focus stacking and image stitching presents a significant advancement in imaging capabilities, especially for complex biological samples that require detailed visualization across multiple focal planes. Focus stacking allows G-Bot to overcome the inherent limitations of shallow depth of field in microscopy by capturing images at different focal depths and combining them to create a single image. The integration of image stitching allows G-Bot to expand its FOV, making it possible to image larger specimens without sacrificing resolution or detail. By stitching together multiple stacked frames, G-Bot can capture an entire specimen with an extended depth of field in a single image. This is particularly valuable in life science applications where both fine details and the overall context of a sample are critical for analysis. For example, Fig. 5F shows the image of a WT AB zebrafish larva, where 32 images were used for stacking in two different frames, scanning a 1 mm height (a total of 64 images). These two frames were then stitched together to capture the whole specimen with an extended depth of field. This combination of focus stacking and image stitching enhances the precision and detail of imaging, enabling operators to capture both large and intricate biological samples in their entirety. This capability is especially beneficial in applications where rapid, accurate imaging is essential for analyzing a wide range of specimens, from cells to tissues and larger organisms.

Graphical user interface (GUI) of G-Bot

System GUI was created using Microsoft Visual Studio and programmed in C# coding language to control the constituting modules of the system from a single software panel. The motion control of the CNC axes, the linear and rotation stages, is achieved via G-coding. Communication and data transfer between the processor and the control cards are facilitated with the UC100 library. On the other hand, the linear stage is controlled via an Arduino microcontroller. The syringe pump and the rotary valve are controlled through their manufacturer’s microcontroller, while the camera settings are accessed through the manufacturer’s DLL files. The Incubator and the Stage-Top Regulation modules are also controlled via additional Arduinos. The Control Module panel enables the manual control of the stages along x-, y- and z-directions. Users can manually bring all axes to the home position and monitor the current coordinate information from this module. The Flow Module panel allows manual control of the syringe pump and the rotary valve. In this panel, the operator can select the port to which the desired solution is connected from the valve selection and adjust the volume of the liquid to be processed from the positioning. The Imaging Module panel displays the real-time sample images. For liquid handling, the GUI allows the user to determine the experimental parameters that will be applied to the selected positions. Cell seeding, medium change, or well cleaning processes can be performed for the desired volumes or concentrations. Once receiving the user-given data, the processor transfers it to the Flow and Control modules using the serial communication protocol. For imaging, the Control Module locates the Imaging Module at the operator-selected positions. After the Imaging Module captures images, they are stored and processed with the algorithms built in the Software Module. GUI also presents the real-time parameters regarding the Incubator and the Stage-Top Regulation modules to the operator. Once the incubator parameters reach the desired levels, the Incubator and Stage-Top Regulation panels notify the user that the system is ready to start, ensuring experiments begin only under stable environmental conditions.

Figure 6A, B show two representative examples to highlight how the system GUI can be used to conduct operations based on the user-defined protocols, e.g., cell seeding and imaging at a single well on a 96-well microplate. For the cell seeding protocol, G-Bot first dispenses the media into the selected well. System cleaning is then performed to aspirate the media remaining in the tubing. Following this, cell seeding is carried out based on the user-given cell concentration. To ensure uniform distribution of the cells within the well, the rotation stage performs the shaking process five times. Finally, a second system cleaning is executed to remove any residues in the tubing. To capture cell images, the G-Bot positions itself on the desired well. If necessary, the user can also manually adjust the camera position. The captured images for the user-given camera settings are then automatically saved in the user-specified file. The panels of the system GUI are explained in detail in the Supplementary Information, and from Supplementary Figs. 7–19. Supplementary Movie 6 is a representative example showing how the system GUI is used to create a protocol for cell seeding.

A Example of a user-defined protocol for automated cell seeding in a single well of a 96-well microplate. The protocol involves sequential media dispensing, tubing cleaning, cell seeding at a user-defined concentration, rotation-based mixing for uniform distribution, and final cleaning to remove residues. B Example of an imaging protocol, where G-Bot positions at the desired well and captures images according to user-specified camera settings, with files saved automatically.

Automated dual-color staining with G-Bot

G-Bot can execute sophisticated sample preparation protocols essential for advanced life science applications. For particular applications, it has different sample holder designs spanning a large variety of container schemes, e.g., microplates, glass slides or Petri dishes (see Supplementary Fig. 20 for the photograph of different holder designs). G-Bot’s automation and precision allow for the handling of intricate procedures, ensuring reproducibility and high-quality results. In this section, as a representative example, we demonstrate how G-Bot handles dual-color staining of biological samples. As schematically highlighted in Fig. 7A, G-Bot can execute multiple steps for staining without disturbing the samples. G-Bot begins the protocol by cell seeding, and the cells are then incubated in a commercial CO2 incubator for 48 h. After cell adherence, G-Bot performs medium change, fixation, permeabilization, and staining with phalloidin and DAPI, where the microplate wells are rinsed with PBS between each step (see “Methods” section for medium change, cell seeding and staining, and zebrafish staining protocols). Figure 7A shows a single L929 cell with clearly visible F-actins (green phalloidin) and nuclei (blue DAPI). Figure 7B presents multiple fluorescence and confocal microscopy images demonstrating the staining capability of G-Bot. As shown in Fig. 7C, we also tested G-Bot on a zebrafish larva stained with DAPI (top) and phalloidin (bottom), which highlights the locations of cell nuclei and the actin cytoskeleton within the cells.

A Schematic illustration of the dual-color staining protocol executed by G-bot. The confocal microscopy image of a single L929 cell clearly shows the nucleus and F-actin formation via DAPI (blue) and phalloidin (green) stains, respectively. B Similar staining procedure conducted by G-bot yields highly clear fluorescence and confocal microscopy images of MCF-7 cells. C Fluorescence microscopy images of a dual-stained wild-type AB zebrafish larva, showing (top) DAPI marking cell nuclei and (bottom) phalloidin highlighting muscle fibers. The image was determined by image stacking using 50 frames along 415 µm. D Schematic illustration of the working principle of PTX (paclitaxel). Created with BioRender.com. E Confluency images of MCF-7 cells captured by G-Bot, demonstrating the antitumor effect of PTX (100 nM) on the cell morphology and density compared to the control group. F MTT viability (gray bar: 24 h, red bar: 48 h, and blue bar: 72 h) and confluency analyses (peach bar: relative change between 48 h and 24 h) demonstrating the increase in cell death with PTX concentration compared to the control group over different treatment durations. In the figure, bars represent the mean of n = 3 repetitions, and the error bars are twice the standard deviation. G Schematic illustration of droplet formation via G-Bot. Created with BioRender.com. H Optical microscopy image of a near-perfect circular droplet formed by G-Bot using 0.2 µL dosing volume. I Variation in the diameter of the droplets for different dosing volumes (n = 10 repetitions for each volume). The box plots indicate the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile); the center line represents the median; whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 × interquartile range; data points beyond this range are plotted individually as outliers; and squares indicate the mean values. Please note that the whiskers do not always represent the absolute minimum and maximum values when outliers are present. The graph also shows the mean standard deviation calculated for each dosing volume. J Microarray formation exhibiting the letters, e.g., IBG, created by G-Bot on a Petri dish.

Precision drug dosing with G-Bot

Precise drug dosing is crucial in life science applications to elucidate cellular pathways and understand disease mechanisms. Accurate and reproducible drug delivery is essential for obtaining reliable experimental data, and G-Bot’s precision in liquid handling could play a vital role in achieving these goals. In this section, we leveraged G-Bot’s precision liquid handling to administer wide drug concentration ranges using paclitaxel (PTX). PTX is a chemotherapeutic agent used to treat various cancers, including breast, ovarian, and lung cancers38. PTX works by binding to microtubules in cells, preventing their disassembly and thus halting cell division as schematically illustrated in Fig. 7D. The high-precision liquid handling capability of G-bot allows us to prepare a wide range of PTX concentrations, 0.1–500 nM (see Methods section for drug preparation). Untreated MCF-7 cells cultured under identical conditions (without PTX exposure) served as the control group for all experiments. For the MTT assay, these controls were normalized to 100% viability at each time point (24, 48, and 72 h). Figure 7E shows the confluency images captured by G-Bot demonstrating the effect of PTX (100 nM) on MCF-7 cells, with a notable increase in cell death compared to the control group. To evaluate the effect of PTX, we performed an MTT assay (see “Methods” section for MTT assay preparation) for different treatment durations, e.g., 24, 48 and 72 h. Figure 4F-left shows the viability results from the MTT assay (gray: 24 h, red: 48 h, and blue: 72 h), where controls were normalized to 100%, and the readings from treated cells were expressed as % of viability. Importantly, G-Bot’s integrated confluency analysis provides an additional layer of validation, allowing real-time tracking of cell growth and morphological changes. Figure 7F-right (peach bars) shows the change in confluency (e.g., confluency at 48 h relative to 24 h), which correlates well with the MTT viability measurements. Our result demonstrates the antitumor effect of PTX, which increases with concentration and treatment duration. Here, G-Bot’s precision drug-dosing capability allows the preparation of treatment groups that could yield a distinguishable viability profile even at very low drug concentrations.

G-Bot allows automated precision droplet generation

Possessing advanced fluid management and motion control capabilities, G-Bot can allow highly precise and consistent droplet formation. Precise control over droplet formation has significant implications for a variety of applications in life sciences. For example, such consistent droplet formation is crucial for high-throughput screening assays, where uniform sample preparation is essential for accurate and reproducible results39. Additionally, the ability to generate droplets with controlled volumes and shapes is valuable in tissue engineering, where precise cell seeding and material deposition are required for the creation of complex biological structures40. Furthermore, this technique could be employed in drug delivery research, where micro-droplets could serve as vehicles for encapsulating and delivering precise doses of therapeutic agents41. The ability to consistently produce droplets with minimal error makes G-Bot an excellent tool for applications that demand high precision and reliability, e.g., preparation of microarrays42, study of cell signaling pathways43, and development of lab-on-a-chip devices44. As shown in the diagram (Fig. 7G), the process begins by positioning the dispensing tubing directly above the target area, where the liquid is carefully ejected to form droplets. The result is a near-perfect circularity as shown in the optical microscopy image (Fig. 7H). G-Bot could form a series of droplets that exhibit uniformity in both shape and size, with a consistent diameter of the droplets. The size of each droplet is controlled by adjusting the volume of the dispensed liquid, which is managed with high precision through the synchronization of the G-Bot’s Control and Flow modules. Figure 7I shows the diameter of the droplets for different dosing volumes, e.g., in the range between 0.2 µL and 0.35 µL, yielding droplet diameters in the range of ~0.8 mm to ~1.3 mm (n = 10 replicates). Here, the mean standard deviation for each dosing volume was found to be below 7%. Using G-Bot, we demonstrated the capability to create precise microarrays, as shown in the image where droplets are dispensed to form the letters, e.g., IBG. This highlights G-Bot’s ability to accurately dispense liquid droplets in a predefined pattern, showcasing its potential for high-precision microarray formation (Fig. 7J).

Long-term real-time imaging with stage-top regulation module

G-Bot enables real-time imaging through the integration of the Stage-Top Regulation Module, allowing live-cell imaging to be performed directly under cell culture conditions. However, as stated earlier, aspiration is necessary to enhance imaging contrast, while this procedure risks disturbing the cells and affecting their proliferation and morphology for long-term studies. In order to perform imaging under culture media while preserving healthy cell growth, we developed a simple yet effective solution, a contrast-enhancing grid slab, which is a printed black-and-white grid paper placed underneath the sample before cell seeding (See Supplementary Fig. 21 in Supplementary Information for the photograph of the grid slab). Figure 8A illustrates the working principle of this contrast-enhancing setup. The black grids enhance the visibility of transparent cells by highlighting their edges and features. By creating areas of varying light intensity, where light either passes through or is blocked by the grid, we improved the detection of otherwise transparent regions. This technique works similarly to phase contrast or differential interference contrast microscopy, enhancing contrast and making transparent samples more distinguishable from the background45. This grid creates sufficient background contrast for brightfield imaging without interfering with cell viability. Once positioned, the grid remains fixed throughout the experiment, eliminating the need for aspiration and maintaining stable culture conditions. In addition to the physical contrast provided by the grid slab, we also employed a custom image preprocessing pipeline to further enhance cell visibility and improve the accuracy of confluency analysis (see Supplementary Information for the details of the contrast-enhancing image preprocessing algorithm).

A Schematic illustration of the grid slab system used to enhance contrast for transparent cells under culture media without disturbing the environment (LED: light-emitting diode). B Left: Schematic representation of the key phases of the mammalian cell cycle. Right: Monitoring MCF-7 cell proliferation over 24 h using Stage-Top Regulation Module. Representative images at t = 6 h, 11 h, and 21 h show a progressive increase in confluency from 45% to 70%. C Left: Schematic illustration of the three phases of adhesion: initial attachment, flattening, and spreading. Right: Visualization of MCF-7 cell adhesion and spreading dynamics immediately after seeding, e.g., representative images at t = 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h. D Left: Schematic illustration of cell detachment due to trypsinization. Right: Real-time monitoring of enzymatic detachment of MCF-7 cells after trypsinization. Images show the condition before trypsin treatment (t = 0) and after 7 min. of exposure, demonstrating significant cell detachment. E Left: Schematic representation of DMSO’s mechanism of action leading to oxidative stress and apoptosis. Right: Monitoring of DMSO-induced cytotoxicity. Representative brightfield images show MCF-7 cells before DMSO addition (t = 0) and after 30 min., highlighting cell morphological changes indicative of stress and early apoptosis. Quantitative confluency analysis shows a decrease from 54.5% to 45.5%. All schematics were created with BioRender.com.

Cell growth and proliferation involve several essential phases, including initial attachment, spreading, and entry into the cell cycle46,47. Figure 8B-left schematically illustrates the phases of the cell cycle. These processes depend on stable environmental conditions, e.g., consistent temperature, CO₂ levels, and nutrient availability, to ensure healthy and reproducible proliferation. To support these requirements, G-Bot is equipped with a Stage-Top Regulation Module that maintains optimal culture conditions during real-time imaging. To assess G-Bot’s capability for long-term live-cell imaging under culture conditions, we conducted a 24-h time-lapse experiment using MCF-7 cells. In this study, cells were seeded at a density of 1.3 × 10⁵ cells/mL in a 35 mm Petri dish and incubated under standard conditions for 24 h to ensure attachment and spreading prior to imaging. After this initial incubation period, the sample was transferred to the Stage-Top Regulation Module, and brightfield images were acquired every 20 min for the next 24 h without interrupting environmental conditions. Figure 8B-right displays representative snapshots from this time-lapse sequence at t = 6 h, t = 11 h, and t = 21 h, showing progressive confluency increase from 45% to 70%, consistent with healthy cell proliferation. These results demonstrate G-Bot’s ability to support long-term imaging while preserving optimal cell culture conditions. A fast-forward version of the full 24-h video is provided in the Supplementary Movie 7 further highlighting G-Bot’s effectiveness in capturing dynamic changes in cell morphology and growth.

G-Bot can also assess cell adhesion dynamics by enabling continuous imaging of the early stages of cell attachment, flattening, and spreading under standard culture conditions. Cell adhesion plays a fundamental role in enabling intercellular communication, tissue development, structural organization, and homeostasis48. As schematically shown in Fig. 8C-left, the cell adhesion process can be divided into three main phases. In Phase I, cells initially establish weak, non-specific interactions with the extracellular matrix surface. In Phase II, integrin-mediated adhesion strengthens, cytoskeletal rearrangement begins, and cells form focal adhesion complexes. In Phase III, cells extend lamellipodia and filopodia, e.g., actin-based protrusions, to flatten and firmly anchor themselves to the substrate, promoting stable adhesion49. To assess G-Bot’s capability to monitor early cell adhesion events in real time, MCF-7 cells were seeded at a density of 6.5 × 10⁴ cells/mL into a 35 mm petri dish and immediately monitored using G-Bot. Time-lapse imaging was performed at regular intervals without disturbing the culture conditions. Representative images at t = 1 h, t = 3 h, and t = 5 h are shown in Fig. 8C-right, highlighting the progressive stages of cell adhesion, e.g., initial attachment, cell flattening, and spreading over time. This experiment demonstrates G-Bot’s ability to capture dynamic cell behaviors during the critical early phases of adhesion under physiologically relevant conditions. Supplementary Movie 8 presents a fast-forward visualization of the 5-h attachment process.

Short-term functional assays under controlled incubation conditions

G-Bot also enables short-term live-cell experiments under incubation-maintained conditions, allowing researchers to monitor rapid biological processes in real-time without disturbing the cells’ physiological environment. Trypsin is a pancreatic serine protease that plays a pivotal role in cell biology applications50. It is widely used in cell culture for the enzymatic dissociation of adherent cells, a process commonly referred to as trypsinization. During this procedure, trypsin cleaves extracellular matrix components and disrupts cell–cell adhesion molecules such as integrins, cadherins, and fibronectin. This targeted proteolysis facilitates efficient detachment of cells from the culture surface and from each other (Fig. 8D-left). However, proper control of trypsin concentration and incubation time is essential to preserve cellular viability and maintain the integrity of functional surface proteins, particularly for downstream applications requiring intact receptor functionality. Here, we monitored the enzymatic detachment process of MCF-7 cells in real-time. Specifically, 1 mL of trypsin was added to a 35 mm Petri dish containing adherent MCF-7 cells, and brightfield imaging was performed continuously over a 7-minute period. Figure 8D-right presents representative images before and after the trypsin application, showing the progressive cell detachment and morphological changes. Prior to trypsinization, MCF-7 cells formed dense colonies firmly attached to the surface. Upon trypsin exposure, cells gradually lost adhesion, rounded up, and detached from the substrate. A fast-forward version of the full 7-minute time-lapse recording is provided in the Supplementary Movie 9, showcasing the dynamic response of the cells to trypsin treatment.

This short-term capability under incubation-maintained conditions also enables real-time monitoring of the immediate effects of treatments on cellular behavior. Regarding this, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an organosulfur compound widely used in biological research as a solvent and cryoprotectant due to its exceptional solubilizing properties51. However, DMSO’s impact on cellular physiology requires careful consideration, as concentrations above 0.5–1% can inhibit cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibitory effects are largely attributed to membrane disruption, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to increased reactive oxygen species production, cell cycle arrest at the G₁ phase, and ultimately apoptosis (Fig. 8E-left)52. To demonstrate G-Bot’s capability for monitoring short-term cytotoxic responses, we applied 5% DMSO to MCF-7 cells under incubation-maintained conditions and tracked cellular responses in real time. As shown in Fig. 8E-right, representative snapshots at t = 0 and t = 30 min reveal significant morphological changes, including cell shrinkage, consistent with early apoptotic events. Quantitative confluency analysis confirmed this observation, e.g., showing a decrease from 54.5% at t = 0 to 45.5% at t = 30 min. A fast-forward video of the 30-min observation is provided in the Supplementary Movie 10. This experiment highlights G-Bot’s ability to capture rapid cellular dynamics, providing valuable insights into drug-induced cytotoxicity under physiologically relevant conditions.

Discussion

The development and integration of G-Bot represent a significant advancement in ALH and imaging technology for life science applications. G-Bot addresses critical challenges in cell-based experiments, large FOV and real-time imaging, and automated data processing. The unique five-axis design, coupled with a syringe pump-based liquid handling system, provides a high level of control and accuracy, allowing for the consistent handling of liquid volumes as small as nanoliters. This precision is crucial in applications such as 3D cell cultures, where the uniformity of cell seeding and the reproducibility of results are essential. By offering real-time visualization of cell behavior and morphology, G-Bot allows for comprehensive monitoring of experimental conditions, including cell confluency, growth, and response to drug treatments. This integration of liquid handling and imaging on a single platform simplifies workflows, reduces human error, and accelerates experimental timelines.

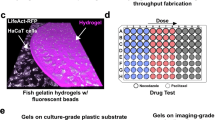

Another key feature of G-Bot is maintaining environmental parameters like temperature, humidity, and CO₂ levels. This ensures optimal conditions for long-term cell culture experiments, reducing variability and enhancing the reliability of experimental outcomes. In addition to the main Incubator Module that maintains global environmental stability during multi-step liquid handling, G-Bot incorporates a Stage-Top Regulation Module designed to maintain localized CO₂ and temperature control directly at the imaging site. This module preserves physiological conditions during extended live-cell imaging sessions, enabling real-time observation of cell proliferation, behavior, and drug response under uninterrupted culture conditions. By injecting regulated air through a sealed chamber around the imaging area, the system sustains optimal micro-environmental conditions without requiring sample transfer or external incubation setups.